TEN

Toward a Circumscribed, Neighborhood-Supportive Suite of Public Policies

Introduction: The Case for a Three-Pronged Neighborhood Intervention Strategy

The foregoing chapter suggests an unmistakable case of market failure. For a variety of reasons, changes in the flows of households and resources across space will produce socially inefficient outcomes. I have also suggested that these outcomes are inequitable; they likely produce the largest penalties for the most vulnerable households. There is thus a prima facie case on efficiency and equity grounds for some sort of collective intervention, whether it is to come from informal social processes, nonprofit community-based organizations, the governmental sector, or some combination of the above. If we do not like how the market is making neighborhoods that shape us in inefficient and inequitable ways—and indeed we should not —we must intervene to remake neighborhoods in the image of our better selves.1

Informal social processes might take the form of sanctions and rewards meted out by neighbors who try to enforce compliance with collective norms regarding civil behavior and building upkeep. Community-based organizations might politically organize, establish bonds of mutual solidarity, or foment a positive public image of the neighborhood.2 Governments might offer information, financial incentives, regulations, and investments of infrastructure and public services, and target them to neighborhoods at crucial threshold points. In concert, these actions can help alter the perceptions of key neighborhood investors and thus leverage their investments, provide compensatory resource flows, minimize destructive gaming behaviors, internalize externalities, and moderate expectations, thereby defusing self-fulfilling prophecies. Because governments typically represent the primary source of the revenues that will be required to fund adequately the policies that I advocate below, I will direct my recommendations toward them.

In this chapter I will propose a suite of policies in three neighborhood domains: physical quality, economic diversity, and racial diversity. Collectively they comprise what I call a “circumscribed, neighborhood-supportive” set of recommendations. The goals of these recommendations are threefold:

- 1. to improve conditions in low-quality residential environments while maintaining them in decent-quality ones,

- 2. to increase the economic and racial diversity in neighborhoods and local political jurisdictions across the metropolitan area, and

- 3. to reduce “forced” (involuntary) residential mobility associated with inefficient neighborhood race and class transitions.

Clearly, worthy goals do not justify all conceivable means of achieving them, so policy makers must carefully assess the equity and efficacy dimensions of particular programs being considered for enhancing neighborhood investment and population diversity. I would argue that programmatic means are most likely to be efficient and equitable if they employ voluntary, gradualist, option-enhancing strategies. I employ these criteria as filters for the particular policy reforms I advocate in the following sections. In particular, my recommendations emphasize voluntary3 but incentivized choices by households and property owners that ultimately will change neighborhoods in cities and suburbs gradually, so that all of them move toward the aforementioned goals. It took generations of market-driven, state-abetted forces of segregation and disinvestment to get where we are; it will undoubtedly take a while to get where we want to be, even with unstinting efforts.

Which Governments Should Undertake Neighborhood-Supportive Policies?

What, then, about the public sector delivery systems that should be energized for enhancing neighborhood investment and population diversity? Ideally, the answer would involve mutually supportive actions at the federal, state, and local levels.

At the federal level, a range of programs that would provide better income and housing support for low-income households and financial support for lower-income jurisdictions would be extremely helpful in achieving the aforementioned neighborhood-supportive goals. It is inconceivable that we could ever eliminate low-quality, undermaintained neighborhoods entirely without the federal government guaranteeing both (1) subsidized housing and/or adequate income supports as a right of all citizens, and (2) revenue sharing or community development block grants of such magnitude that they would effectively equalize fiscal capacity across local jurisdictions. The former federal guarantee would affect the rental stream that a property owner can expect, and without which they cannot supply decent middle-quality housing. Making decent, affordable housing a fully funded right in the United States would be tremendously pro-neighborhood, as it would eliminate the financial incentives for landlords to provide low-quality stock because there would be no demand for it.4 The same consequence would result from a generalized, guaranteed income-support program, such as a more robust earned income tax credit. The latter federal guarantee would affect nondwelling aspects of the residential environment related to the local jurisdiction’s ability to finance quality services, infrastructure, facilities, and agencies.5 Jointly, these two guarantees would eliminate the economic motivations to have a low-quality housing submarket, and permit those receiving person- or place-based housing subsidies to be far less concentrated geographically than they now are.

States also could undertake forms of people-based income and housing assistance and place-based financial assistance analogous to the ones I have just advocated for the federal government. Indeed, many states have their own programs for social welfare assistance, subsidized housing, and intergovernmental revenue sharing, though they vary greatly in their scope and efficacy. States could enable neighborhood-supportive policies even more directly, however, by mandating more regional, metropolitan-area-wide governance structures.6 Clearly, the most efficacious governance structure for intervening comprehensively and holistically in neighborhoods would be one that corresponds in scale to the metropolitan area over which the market-driven forces of neighborhood change reverberate across the housing submarket array. We have several examples of such “bigger box” governmental structures tackling key forces shaping the flows of financial and human resources across neighborhoods, such as metropolitan growth boundaries in Oregon; regional tax base sharing in the Minneapolis–St. Paul metropolitan area; unified school districts in Charlotte–Mecklenburg County, North Carolina; and inclusionary zoning in Montgomery County, Maryland.7

Despite the unambiguous advantages in having more neighborhood-supportive federal, state, and regional policies, I will not discuss them in more detail. Rather, my focus in this chapter will be on policies and programs that local governments can undertake, regardless of the degree to which they receive collaborative, financial, and programmatic supports from other levels of government, foundations, and community-based organizations. Certainly, local governments will be more successful when such support is stronger; indeed, at the end of this chapter I will suggest a great deal of circumspection about what local governments can accomplish if they are forced to go it alone. Nevertheless, even when such supports are massive, there are indispensable roles that local governments must play in delivering neighborhood-supportive policies. As I will amplify below, local governments are in the best position to operationalize the nuanced strategic targeting required for a successful neighborhood policy.

The Foundation of Neighborhood-Supportive Policy: Strategic Targeting

Strategic targeting provides a framework within which policy makers must devise and deliver effective programs comprising a neighborhood-supportive policy. Strategic targeting means that policymakers should develop initiatives holistically within the context of metropolitan housing submarket projections, and then direct them at particular neighborhoods with sufficient intensity that the behaviors of private market actors (especially households and residential property owners) will change substantially there. Formulating policies and programs holistically means both recognizing causal interrelationships among neighborhoods within and across jurisdictional boundaries, and trying to achieve the tripartite goals of neighborhood reinvestment, economic diversity, and racial diversity.

Operationalizing strategic targeting means making decisions in three realms: context, composition, and concentration.8 Context refers to the current and projected opportunities and constraints on the jurisdiction’s neighborhood trajectories that a metropolitan area’s housing market affords. Before one can logically decide how and where to intervene, one must be aware of the current and the projected future regional context, as well as local conditions. Long-run forecasts of metro-wide population, incomes, employment, and infrastructure investments must form the foundation strategic targeting. This is necessary to anticipate the forces that are likely to impinge most strongly on particular neighborhoods throughout the region, using the predictive logic of the metropolitan housing submarket model developed in chapters 3 and 4. The appropriate region-wide planning entity or council of governments typically would undertake this geographically disaggregated forecasting. Ideally, a strategic targeting plan would be collaboratively drawn up for the metropolitan region as a whole, and executed comprehensively at the regional level. Since these powerful, regional bodies are scarce in the United States, however, cities by default will often bear the responsibility for strategic targeting plans. Even when done in a decentralized fashion, these plans must be cognizant of region-wide forecasts and the behaviors of other jurisdictions. Only then will they know where to expect changes of what sort in their own constituent neighborhoods, and rationally target their scarce resources most efficaciously. Strategic targeting also depends on ongoing, up-to-date information about neighborhoods, to monitor and assess progress of past interventions and direct new ones. By implication, this means that cities must have access to a battery of virtually real-time neighborhood indicators.9

Composition means that the programmatic particulars of interventions contemplated for any neighborhood must be contingent on the current and projected future characteristics of that place and the particular goals appropriate for that place. Clearly, not all neighborhoods require intervention, and those that might do not all require the same sort of intervention. I amplify my point with the help of the typology of neighborhoods presented in table 10.1.

Strategic targeting requires that each neighborhood in the relevant geography for planning purposes be categorized in terms of a typology analogous to that in table 10.1, so that the broad contours of the treatment, if any, is specified unambiguously. The categories are intuitive:

- • abandoned, no investment cases: no intervention until potential for market revival, because no amount of public investment will jump-start market

- • neighborhoods of type C or D: no intervention required because market is producing desired investment levels and acceptable economic and racial diversity

- • neighborhoods of type A (an unusual type) and E that would typically be areas of concentrated poverty or occupied “slums”: interventions that should be aimed at stimulating private investment and deconcentrating low-income minority households

- • neighborhoods of type B (diverse areas of incipient physical decline and disinvestment, perhaps because of some previous downward income succession): interventions that should be aimed at stimulating private investment

- • neighborhoods of type F (homogeneous areas of incipient physical decline and disinvestment): interventions that should be aimed at stimulating private investment and increasing economic and/or racial diversity

- • neighborhoods of type G (gentrifying areas where wholesale displacement of previous lower-income residents are predicted): interventions that should be aimed at preserving economic and racial diversity

- • neighborhoods of type H (homogeneous areas of decent quality): interventions that should be aimed at increasing economic and/or racial diversity.

Concentration means that policymakers must apply the tangible public interventions (e.g., financial subsidies, infrastructure investments, community building) at a sufficient spatial density in the targeted area so that the private actors’ thresholds for undertaking positive actions vis-à-vis this neighborhood are surmounted. Evidence regarding public intervention thresholds for encouraging neighborhood population diversity is lacking, but the evidence for physical investment thresholds is compelling. Recall that I showed in chapter 6 that theory and evidence strongly support the existence of neighborhood investment thresholds. These must be exceeded before private property owners will spend their own funds improving their properties. Four studies of local government efforts to revitalize neighborhoods provide remarkably consistent evidence on what amount of public investment is needed to surmount these thresholds. Kenneth Bleakly and colleagues examined policies that spatially targeted Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) and other investments in thirty Neighborhood Strategy Areas in twenty cities during the period 1979 to 1981. They reported that substantial improvements in neighborhood physical conditions only occurred when there was a higher than average concentration of CDBG expenditures per block.10 Peter Tatian, John Accordino, and I investigated the impacts of Richmond’s Neighborhoods in Bloom initiative, which consistently targeted CDBG and Local Initiative Support Corporation funds during the 1999–2004 period. We also found that significant improvements in property values only occurred when the investments per block exceeded the sample mean amount.11 With colleagues Chris Walker, Chris Hayes, Patrick Boxall, and Jennifer Johnson, I measured the relationship between CDBG expenditures and subsequent changes in a variety of neighborhood indicators across seventeen cities during the 1990s. Once again, we found that such expenditures did not have a noticeable relationship with improved census tract trajectories unless they exceeded the sample mean expenditure.12 Finally, Jennifer Pooley analyzed the impact of Philadelphia’s allocation of CDBG funds during the 1990–2009 period and determined that these dollars resulted in significant property value improvements in census tracts only when targeted at greater than median amounts.13 When we adjust the particular investments analyzed in these four studies for the periods over which they were invested, their spatial scales, and subsequent inflation, consistent dollar thresholds emerge. The first two studies indicate that the public sector needs to invest (measured in 2017 dollars) at least roughly $54,000 annually for five years or $62,000 annually for three years in each target block. The last two studies indicate thresholds of $138,000 annually for ten years or $271,000 annually for five years in each target census tract (measured in 2017 dollars). These sums are not trivial; by implication, local jurisdictions need to focus their neighborhood investments spatially instead of falling prey to the temptation of “doing something for every neighborhood.”14

Strategic targeting tells neighborhood policy makers that they must carefully consider context, composition, and concentration. It does not ultimately specify, however, which types of neighborhoods displayed in table 10.1 policy makers should select as targets for intervention. The appropriate decision will depend on the particulars of metropolitan housing market forces, the competitive position of the particular jurisdiction’s neighborhoods and the resources at its disposal, and, of course, local political considerations. Fundamentally, the choice is whether a jurisdiction intervenes with its limited resources in the worst-off neighborhoods (types A and E), or in those showing early signs of incipient decline (types B and F).

To address this question is to engage in a long- standing controversy over the notion of triage. To extend the analogy from battlefield emergency medicine, where it was first coined, neighborhoods can be classified into three groups depending on the severity of their “injuries”: “fatally injured” (types A and E), “critically injured” (types B and F), and “mildly injured” (types C, D, G and H). The triage approach advocates for focusing attention solely on the second, “critically injured” group, which can be “saved” only if we intervene quickly and effectively. By contrast, triage argues that we should not intervene in the other groups because the first will expire regardless of whatever intervention we attempt, and the last will heal without intervention. The medical metaphor is not fully apt, of course, because sufficiently massive investments could bring even the most moribund neighborhood back to life. Nevertheless, the triage approach does point to a valid consideration about where investments of limited public resources can generate the most efficacious impacts.

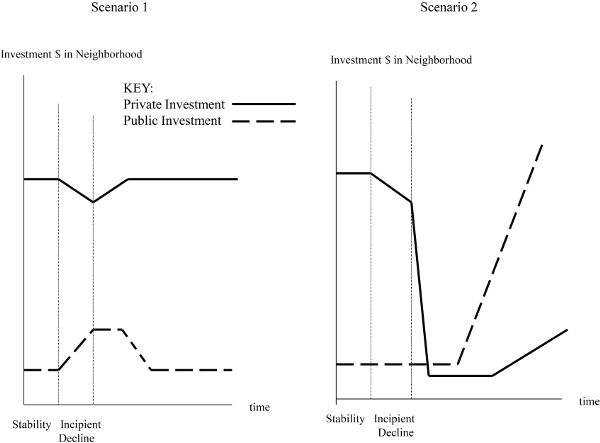

Figure 10.1 helps illustrate the point. It portrays flows of public and private investments into a hypothetical neighborhood over time. In the earliest period shown, the neighborhood is perfectly healthy (type D), with substantial flows of investment by private property owners for the upkeep of their residential and nonresidential buildings, and by the public sector in form of services, facilities, and infrastructure maintenance. At some point, however, some unspecified external force, reverberating through the metropolitan housing submarket array, reduces the competitive position of this neighborhood, such that the private sector begins to reduce its investments (type B neighborhood). If this incipient decline is not countered, private investment may eventually fall precipitously, as negative externalities and signaling behaviors associated with undermaintenance and downgrading of residential and nonresidential buildings generate self-reinforcing responses by nearby owners. This downward spiral of disinvestment eventually produces a neighborhood of type A, or an abandoned one, shown in scenario 2.

Figure 10.1. A rationale for triage-based intervention: two scenarios of alternative public and private investments flows into a neighborhood

The triage position argues that it is a wiser use of public resources to intervene in type B neighborhoods as soon as incipient decline is visible. Policymakers would hope that only a relatively modest amount of new public investments here, applied over a relative short period, will be required to exceed owners’ reinvestment thresholds in this context and return the neighborhood to full health quickly, as shown in scenario 1. By contrast, a massive investment of public resources will be required to resuscitate the private market in a moribund neighborhood, as shown in scenario 2.

This core argument of the triage position is compelling. Why would policymakers not invest a modest amount in helping a neighborhood recover from a “minor illness,” instead of waiting until it requires more expensive critical care when it is near death? Nevertheless, on both efficiency and equity grounds one can make several convincing counterarguments. To do triage effectively, one needs a reliable early warning system of indicators that can identify when incipient neighborhood decline has begun and which ill neighborhoods are closest to the critical threshold of disinvestment. When a jurisdiction confronts neighborhoods that have become type A in the past, should they indeed keep a “benign neglect” stance indefinitely while awaiting external market forces to push the neighborhood into type C? Because those living in such type A neighborhoods are likely to be the jurisdiction’s most disadvantaged, some might argue on equity grounds that interventions designed to improve their quality of life might be justified. The opposite side of the same equity coin is the argument that public investments in type B neighborhoods will benefit primarily middle-class households and property owners, instead of the neediest citizens. Nevertheless, one can forward an equity-based rejoinder. Triage-based interventions are the most fiscally prudent way to preserve a jurisdiction’s local tax base, which provides the foundation for decent public services and facilities that redound to the benefit of all citizens, not the least of whom may be disadvantaged. Ultimately, the appropriateness of a triage approach will depend upon the particular housing market and the fiscal, social, and political circumstances facing the policymakers in question.

Regardless of the position one takes on the triage issue, it is imperative that policymakers and planners adopt strategic targeting as the guiding principle for developing neighborhood-supportive interventions. Local jurisdictions simply do not have sufficient resources at their command to effect all the neighborhood changes they might view as desirable. They thus must use their precious resources to leverage private resources aimed at the same goals. Accomplishing this effectively requires that they employ an evidence-based system for identifying (1) the current and future flows of private resource into all neighborhoods, (2) what particular programs will enhance these flows most powerfully in the areas chosen, and (3) how intensely these programs must be applied there to trigger the requisite supportive private responses.15

Encouraging Neighborhood Investments

There are three general programmatic strategies that the public sector could pursue for encouraging additional private investments in neighborhoods strategically targeted for intervention. The first improves in a variety of ways the physical, social, and psychological aspects of the residential context surrounding property owners, and thereby stimulates their dwelling reinvestment efforts. The second incentivizes reinvestment activities directly through both “sticks” (housing code enforcement) and “carrots” (grants or low-interest loans intended to defray costs of dwelling improvements). The third strategy augments neighborhood-wide upkeep levels indirectly, by increasing the number of dwellings that are owner-occupied. As I will demonstrate below, the latter two strategies hold more potential as potent, effective tools of neighborhood reinvestment policy.

Improving Neighborhood Context

A common program that local policy makers often employ as a stimulant for residential reinvestments by the private sector is that of refurbishing and improving public neighborhood infrastructure. This would include sewer, road, and sidewalk improvements; decorative light fixtures; streetscaping; and the like. There is no doubt that such public investments enhance the physical quality and property values of the targeted blocks. There is no evidence that they induce further private investment, however, unless they include a much more comprehensive set of subsidies and related area-based initiatives. My research in Minneapolis and Wooster demonstrated that improved physical conditions in the public sphere of the block face affected the housing upkeep behavior of homeowners only minimally.16 Furthermore, these improvements did significantly abet their optimism about the future quality of life in the neighborhood. Beyond the blocks where infrastructure investments were made, the consequences may prove deleterious, because homeowners on nontargeted blocks may perceive that the relative quality of their own areas has now fallen, and they are more likely to engage in free-rider gaming behavior. Therefore, the aggregate net result on private reinvestment may not even be positive.

Land-use zoning regulations are another potential policy option for influencing the neighborhood’s physical environment and thus stimulating private investment. The results from my aforementioned study, however, give no indication that areas currently with mixed land use have lower home upkeep levels than areas with homogeneous residential uses. Indeed, for certain homeowners the effect was just the opposite.17

As for altering the social-psychological milieu of the dwelling owner, the evidence from my work is more mixed. I found that manipulating homeowners’ expectations in a way that encourages optimism about the neighborhood as a place to live significantly enhances dwelling upkeep.18 Unfortunately, in lower-valued neighborhoods, if such optimism also carries over into property-value expectations, the beneficial upkeep results disappear. The prickly policy problem here is how to engender crowd-following behavior through optimistic qualitative neighborhood expectations without simultaneously engendering free-rider behavior due to optimistic property-value expectations. “Building neighborhood confidence” thus is a policy prescription rife with half-truth, and a prescription we have no proven policy instruments to fill successfully.19

Public efforts aimed at the maintenance and creation of neighborhood social cohesion also appear to be a double-edged policy sword. On the one hand, neighborhoods with strong solidarity sentiments and collective identification clearly produce far superior levels of homeowner upkeep activity, all else being equal. They improve efficiency by providing a social means for internalizing home upkeep externalities and simultaneously coordinating otherwise destructive strategic gaming behaviors by homeowners in the area. I found that owners in the most cohesive neighborhoods who identified most closely with their neighbors annually spent 28 to 45 percent more on home maintenance and improvements, and evinced a 66 percent lower likelihood of exterior home defects, compared to average homeowners in noncohesive neighborhoods.20 On the other hand, the dangers of intensified neighborhood parochialism that may attend enhanced cohesion may be nontrivial. Again, it is doubtful whether local planners and policy makers have mastered the manipulation of neighborhood social dynamics sufficiently to attain only benefits from a potential cohesion-building program. Nevertheless, the potential payoffs for stabilizing neighborhood investment levels appear so great as to warrant significant amounts of further study.

A final neighborhood context-alteration strategy is that of working with financial institutions (either as collaborators or as antagonists through Community Reinvestment Act or fair lending challenges) to ensure adequate home purchase and improvement loan flows into targeted neighborhoods. Though we surely can laud such actions, in themselves they are insufficient as cornerstones of neighborhood reinvestment policy. Coordinating lenders’ behaviors can profitably reduce their prisoner’s-dilemma situation and spur financial resource availability, but the ultimate impact on housing rehabilitation activity depends on the desire by property owners to take advantage of these resources.

Thus, it is apparent that the first overall neighborhood reinvestment strategy of altering the context surrounding individual property owners’ upkeep decisions has severe limitations. There is no evidence that changes in the physical infrastructure will induce them to undertake significantly more dwelling investments. Changes in the sociopsychological context have more potential for shaping homeowners’ upkeep behavior. Unfortunately, the programmatic means for influencing expectations and social cohesion in controlled, net-beneficial ways have yet to be developed. Moreover, the possibilities of major unintended consequences spawned by public policy blunders in this area are rife. Policies to augment home purchase and improvement loan flows may have positive effects, but have limited applicability for dealing with reinvestment psychology in more challenged neighborhoods.

Incentivizing Incumbent Upgrading

The second general policy approach of directly incentivizing current property owners’ reinvestment efforts in strategically targeted neighborhoods is far more effective and less fraught with unintended outcomes. A coordinated incentive policy should involve a package of both positive and negative incentives, delivered with contingencies related to owners’ abilities to pay and other quid pro quos to which they must agree as a condition for receiving subsidies.

The primary positive incentives here consist of dwelling rehabilitation grants and/or low-interest (or forgivable) loans to incumbent property owners in the target neighborhoods.21 Garry Hesser and I conducted a benefit-cost analysis of the rehabilitation grant and low-interest or deferred-loan programs in Minneapolis.22 All else being equal, the homeowner’s receipt of a low-interest loan or grant for home rehabilitation was associated with significantly higher home upkeep expenditures: $35 per $100 in loans and $262 per $100 in grants received. There also was a modest indirect effect of such loan-grant policies on the neighbors of recipients. Homeowners who did not personally receive a subsidy, but who lived in areas where others did, had more optimism about the future quality of their neighborhoods. This, in turn, translated into a 4 percent larger upkeep expenditure stream from them, and a 13 percent lower incidence of exterior home defects manifested on their homes. Whether such increments to property upkeep prove to be “worth” (in a strict budgetary sense) the allocation of local public monies depends on the assumptions one makes about (1) how such housing upkeep increments and positive externalities ultimately become capitalized into the neighborhood’s property values, (2) the public sector’s discount rate, (3) the terms and conditions of the grants and loans, and (4) the jurisdiction’s property tax rate.

Hesser and I found that rehabilitation loans and especially grants had benefit-cost ratios in excess of one under wide ranges of plausible parameter assumptions, regardless of whether one took the viewpoint of a local public official or a geographically broader perspective. However, most loans repaid over terms exceeding about five years were unlikely to be net beneficial from a local public-sector budgetary standpoint. The relative superiority of grants to loans in terms of comparative budgetary benefit-cost ratios depends on the public discount rate (that is, the opportunity cost of funds), and the terms of the loan. Grants will generally be the preferable option (1) the longer the deferment of loan repayment, (2) the higher the discount rate, (3) the lower the loan’s interest rate, and (4) the lower the indirect leveraging and externality effects of the subsidies. Even assuming a high loan interest rate of 8 percent, a high discount rate of 9 percent, and generous indirect leveraging and externality effects, loans are superior to grants only if owners can repay within ten years. This, of course, may be financially impossible for many lower-income homeowners whom policy makers would wish to participate in such a program, unless policy makers structure the loan to be repayable only upon sale of the property. Thus, the efficiency of a housing rehabilitation subsidy program will be improved if subsidies are packaged in such a way that, whenever possible, recipients who can afford to do so are only allocated loans that have benefit-cost ratios superior to those of grants (that is, loans that carry a nontrivial interest rate and are repayable within five years). Policy makers then would reserve grants for recipients where affordability concerns suggest that only inefficient low-interest, long-repayment-schedule loans could be offered otherwise.

Of course, to secure maximum neighborhood-wide increases in private residential investments, the public sector may wish to compel participation, instead of relying solely on positive externalities and the endogenous contagion effects among property investors I have documented in prior chapters.23 One way to do so is through targeted housing code enforcement. Violators would have a defined period during which they would need to complete necessary repairs and improvements satisfactorily before fines would be exacted. Owners of properties with code violations could then voluntarily apply for the aforementioned need-based grants or loans, should they qualify.

Depending on the generosity of the subsidy proffered, the local public sector could reasonably extract a variety of potential concessions from the beneficiary property owners. For owner occupants of single-family dwellings, this could take the form of a minimum residency requirement post-subsidy or an agreement on sharing some amount of capital gain due to home appreciation between time of subsidy and sale. For absentee owners, the quid pro quo might consist of a period during which rents are frozen at original, presubsidy levels, or constrained to rise at a below-market rate of inflation.

In sum, directly influencing property owners’ reinvestment calculus through public incentives commends itself as an important tool of a neighborhood reinvestment strategy. If packaged correctly, a grant and loan program can generate increments of residential benefits far larger than budgetary costs. Because such benefits will largely if not completely manifest themselves as enhanced property values in the jurisdiction, it is conceivable that such a housing rehabilitation program could be self-funding in the long run. That is, even if local governments reassess only part of the property-value gains for tax purposes, their property tax revenues will likely increase enough to offset the original subsidy provided. When coupled with targeted code enforcement to ensure participation, and an appropriate menu of quid pro quos required of subsidy recipients, this strategy has much to recommend it.

Expanding Homeownership in Target Neighborhoods

The third broad category of neighborhood reinvestment policy options does not take as predetermined the number of homeowners in strategically targeted neighborhoods, as do the previous two categories. This third approach tries to produce a net increase in the number of homeowners (with a concomitant reduction in absentee owners) throughout the metropolitan housing market, especially among lower-income households and those living in targeted areas. Crucially, this policy does not aim to move existing homeowners from one neighborhood to a targeted one; rather, it is aimed at assisting those who might not otherwise be able to become homeowners, or at least not very quickly. This strategy offers promise primarily because owneroccupants generate several forms of positive neighborhood externalities. First, they maintain their dwellings at levels far superior to those evidenced by absentee owners, controlling for cross-tenure variations in occupant, dwelling, and neighborhood characteristics.24 Second, they augment social capital by participating more actively in local social organizations and civic groups.25 Third, they create superior environments for the development of healthy, higher-performing children, thus reducing the chances that youth incivilities, vandalism, and the like will afflict the neighborhood.26 Fourth, they arguably create greater collective efficacy that, in conjunction with the previous consequences, may produce a safer neighborhood.27

There are several proven ways in which policy can help modest-income households to overcome barriers to owning a home.28 It is likely, however, that these interventions would raise the overall homeownership rate in a jurisdiction, and not concentrate the new homeowners in the neighborhoods targeted for revitalization. What would be preferable is a program that ties the assistance for attaining homeownership to the targeted neighborhoods. At least two options suggest themselves. First, properties that have been foreclosed by the local taxing authority in the target neighborhoods could be selected for rehabilitation and resale at below-market rates to first-time, low-income households, perhaps in combination with requirements on the new buyer for a sweat equity component, pre- and postpurchase counseling and financial management, a minimum stay in the dwelling, and shared home appreciation capture. Second, spatially nonspecific homeownership assistance (such as down-payment grants, counseling, case management aimed at improving and stabilizing income, and credit repair) might be granted only on the condition that the new home purchased is in a designated target area.

Regardless of programmatic particulars, it is clear that if policy makers can expand and maintain more homeowners in target neighborhoods at moderate cost, the payoffs in the form of enhanced property upkeep, housing values, residential stability, and social cohesion will be dramatic. Bev Wilson and Shakil Bin Kashem found that if a census tract’s homeownership rate increased by ten percentage points, the value of homes there would appreciate by 1.6 percent more.29 Edward Coulson, Seok-Joon Hwang, and Susumu Imai estimated a marginal social benefit of about six thousand dollars for each dwelling that switched from absentee- to occupant-owned in neighborhoods having low homeownership rates initially.30

Toward a People-in-Place-Oriented Neighborhood Reinvestment Strategy

Recall the upshot of chapter 9 that motivated the foregoing policy discussion. Our market-dominated system for determining the flows of human and financial resources across neighborhoods has produced a systematic bias toward too little investment in housing. These inefficiencies arise primarily due to the presence of externalities of several sorts, strategic gaming, and self-fulfilling prophecies. I have argued here that policies that focus on improving the neighborhood physical environment or the resident’s expectations of it will likely not be as successful in spurring investments by property owners as those that focus on altering their financial incentives and the aggregate tenure characteristics of residents there. A strategy involving dwelling improvement requirements, coupled with subsidies if necessary, attacks a major source of inefficiently low reinvestment levels: strategic gaming among owners. A strategy that expands homeownership directly boosts incentives to invest, and establishes the prerequisite for abetted social identification and cohesion at the neighborhood level, which further intensifies reinvestment indirectly. In sum, I advocate a “people-in-place” reinvestment component of strategic targeting that focuses on the selected neighborhoods’ owners of residential property, both those who have owned for a considerable period and those who can attain stable homeownership through the policies applied.

Encouraging Economically Diverse Neighborhoods

As table 10.1 emphasizes, policy makers may wish to intervene in neighborhoods receiving appropriate flows of investment but are inappropriately diverse in their populations. In the next two sections, I consider strategies for altering the economic and racial mix of neighborhoods.

Policies for altering the economic diversity of neighborhoods fundamentally depend on some sort of assisted housing, whether one attaches the assistance to a specific dwelling or to a lower-income tenant; I consider both below. To be “neighborhood-supportive,” public policymakers, developers, and operators of assisted housing (both site- and tenant-based) must pay close attention to (1) concentration, (2) development type and scale, (3) monitoring of tenants, (4) management of buildings, (5) collaboration with neighborhoods, and (6) public relations. Neighbors and the housing market clearly can distinguish between low concentrations of assisted households residing in small-scale buildings that reflect good design, maintenance, and management and those that are not. The former sort of “good” assisted housing can become cognitively invisible to neighbors as a potential concern contributing to neighborhood disinvestment and decline.31 Thus, I design my policy recommendations holistically to confound negative public stereotypes about deconcentrated assisted housing by striving for universally well conceived and well operated programs. Most recommendations will apply to federal policies and programs since, unlike in the case of financial investments in neighborhoods, they control how the vast majority of assisted housing plays out on the local level.

Overarching Reforms

Before considering reforms that should be made to particular federal assisted housing programs, there are five neighborhood-supportive yet not budget-busting reforms I would advocate that overarch all such programs.32

Regional assisted housing institution building. The federal government or state governments cannot fulfill most of the above criteria for a neighborhood-supportive housing policy; only a more local organization can accomplish these ends. Undoubtedly, some public housing authorities (PHAs) and local governments have proven that they have the requisite human, technological, and financial resources to oversee successful assisted housing programs; others clearly do not. Moreover, even competent organizations rarely have region-wide authority. How, then, can programmatic reforms be delivered in a consistently effective manner across each metropolitan area in the nation with the current institutional structure?

I believe that we need considerable experimentation to find the best method for enhancing institutional capacity to operate metro-wide, neighborhood-sensitive assisted housing programs. An innovative proposal forwarded by Bruce Katz and Margery Turner offers an illustration.33 They argue that the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) should allow interagency competition for administering a single, seamless public housing / Housing Choice Voucher (HCV) program spanning each metropolitan region. HUD could solicit bids from PHAs, state housing agencies, and other nonprofit organizations. This regional organization would also coordinate with the state authority administering the Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program. Whatever new organizational structures emerge, it is crucial that the various programmatic elements collaborate closely across the entire metropolitan area.34

Fair housing law revisions. New legislation should add source of income as a protective class in federal, state, and local fair housing law, similar to how the law treats such classes as race, color, religion, gender, and national origin. This hopefully would change the behavior of landlords who currently can slough off requests to lease by a voucher holder on the perfectly legal basis that “they do not wish to participate in a housing assistance program.” An undetermined number of landlords may now be using this excuse as camouflage for illegal discriminatory intent regarding a currently protected class of tenant. More landords likely decline to participate because of their aversion to the housing inspections associated with the voucher lease-up process, onerous bureaucratic procedures by the local housing authority, or negative reactions by their unsubsidized tenants. Of course, eliminating one vehicle for not renting to a voucher holder does not eliminate them all; so this policy reform, though likely helpful, will not in and of itself be sufficient to increase substantially the scale and geographic scope of dwellings to voucher holders.35 Other reforms, discussed below, will be required as complements.

Impaction standards. The aforementioned regional housing authority should promulgate regulations for both assisted households and developers that would limit the concentration and scale of assisted housing of various types in all types of neighborhoods.36 At minimum, these regulations should establish threshold concentrations of poverty and assisted housing past which further site- or tenant-based assistance would be ineligible; racial-ethnic contingencies could also be applied to encourage racial diversity. Many precedents for such restrictions on HCV usage have arisen in the context of settling PHA desegregation cases.37 Developers of scattered- site assisted housing similarly should be restricted in which neighborhoods they can develop units, and how many they can develop there within certain separations. There also are ample precedents for such supply-side impaction standards.38

Encourage the rehabilitation of structures as assisted housing. A key component of a neighborhood-supportive policy involves transforming a neighborhood eyesore into a well-maintained assisted housing site because it will provide substantial positive externalities and public relations gains.39 To the extent that is feasible, site-based assisted housing programs should attempt to acquire and rehabilitate vacant, poorly maintained properties. HUD might alter its expense reimbursement formulas for PHAs in ways that encourage development through rehabilitation rather than new construction. States might also alter scoring formulas for LIHTC applications to better incentivize rehabilitation. Tenant-based assisted housing programs could seek to recruit owners of deteriorated properties, especially in otherwise strong neighborhoods, and then offer financial incentives for the rehabilitation of said properties in exchange for long-term availability of units for HCV lease-up.

Diversity incentives built into AFFH. HUD’s 2016 Final Rule for Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing requires state and local governments receiving HUD funds to demonstrate how their housing and community development programs promote fair housing; but it lacks sufficient teeth to elicit major changes.40 These localities should be incentivized financially to move toward more economic and racial diversity in their constituent neighborhoods. I recommend “opportunity housing” bonuses for local governments, funneled through a formula-altered community development block grant program or some other vehicle. Homeowner constituent political support for such a policy could be encouraged through modified Internal Revenue Service rules, which could permit, for example, enhanced deductions of local property taxes and/or mortgage interest payments on residents’ federal taxes if their community met its “fair share” of assisted housing sites, or made progress toward neighborhood diversification.41

Reforms for Site-Based Assistance Programs

Repeal and replacement of the QCT bonus. Current federal regulations specify that developers of LIHTC projects located in “qualified census tracts” (QCTs) having poverty rates over 25 percent receive bonus credits. Although there is logic in the QTC provision because such areas are more difficult to develop, this provides a perverse incentive, explaining why most LIHTC units have been developed in places that reinforce concentrations of minority poverty.42 This bonus system should be reversed so that it incentivizes development in high-opportunity neighborhoods with little affordable housing, consistent with my suggested impaction standards.

Diversification/preservation incentives for existing assisted private developments. Some privately owned assisted housing developments will have their affordability contracts expire in the future, whereupon owners may convert the units to market rate, especially in hot-market contexts. Instead of foregoing such opportunities to lock in affordability in revitalizing neighborhoods, we should provide incentives for continuing a share of these units as affordable, consistent with my suggested impaction standards.43

Preserving public housing in revitalizing neighborhoods.44 Sometimes public housing is strategically located in areas that are gentrifying, and maintaining them as good-quality housing in such area would help to lock in affordable options. The new Rental Assistance Demonstration offers more flexibility for PHAs to use HUD funds in combination with other programs to support the renovation and redevelopment of public housing.45 HUD should better target such initiatives toward preserving affordability in revitalizing neighborhoods.46

Reforms for Tenant-Based Assistance Programs

Adopt small area fair market rents (SAFMRs). The standard HCV program establishes a subsidy for each particular size of dwelling based on fair market rent (FMR), defined as the 40th percentile in the metropolitan-wide rent distribution for that dwelling size.47 This formulation creates a perverse incentive structure that reinforces concentrations of disadvantage. FMRs are often above the rents the market will bear for lower-quality dwellings in high-poverty neighborhoods; thus, landlords in those neighborhoods will be eager to recruit HCV holders actively. Analogously, HCV holders will find that they can reduce their contribution to rent if they settle on lower-quality dwellings in high-poverty neighborhoods renting for less than FMR. Just the opposite disincentives apply for landlords and HCV holders in opportunity neighborhoods. HUD should remove these perverse incentives by adopting a policy whereby FMRs are calculated for each zip code.48

Require premove and postmove mobility counseling. Low-income households have limited resources with which to undertake housing searches once local authorities issue them a voucher, and typically they and others in their networks have had little experience with and information about opportunity neighborhoods.49 Local voucher providers must provide to each HCV holder intensive, hands-on mobility counseling and relocation assistance in locating and inspecting apartments in opportunity neighborhoods. There also should be postmove follow-ups to provide counseling, information, and other assistance aimed at heading off HCV holders from becoming discouraged and wishing to move out.50

Provide ancillary family supports after the move. Counseling alone may be insufficient to yield residential stability and satisfaction by HCV holders residing in opportunity neighborhoods. HUD affiliates and other social welfare agencies should provide HCV holders with a wider set of supports—including, where appropriate, subsidized day care and a used automobile.

Reduce barriers to leasing. Administrators of HCV programs should enact several reforms that would help voucher holders lease dwellings in high-opportunity areas more quickly, with less frustration and fear of expiration of the lease-up window.51 Illustrations include (1) financial assistance for moving costs, furnishings, and apartment and utility security deposits; (2) recruiting and communication with landlords so that they will be more willing to welcome HCV applicants; and (3) extension of the lease-up period beyond the conventional sixty to ninety days.

Change diversification incentives in HUD regulations governing PHAs. The current regulatory structure through which HUD assesses and rewards the performance of each PHA, the Section Eight Management Assessment Program (SEMAP), does not reward placing HCV holders in opportunity neighborhoods or punish them if they place HCV holders in disadvantaged neighborhoods.52 Moreover, portability of vouchers across jurisdictions is implicitly discouraged. No extra financial assistance is provided to PHAs who receive incoming HCV holders from outside their jurisdictions, or to those PHAs where HCV holders originate, despite the additional administrative burdens.53 Revising these assessment policy and portability limitations would become less vital, of course, were my proposed strong impaction standards established as substitute criteria as part of SEMAP.

Do Low-Income Households Want to Move to More Economically Diverse Neighborhoods?

I have argued for reforming serious flaws in federal assisted housing policy because thus far it clearly has not accomplished much economic or racial desegregation or improved access of low-income (often minority) households to high-opportunity neighborhoods.54 At this point I must acknowledge a contrary perspective. Some have argued that the weak past performance of assisted-housing programs in deconcentrating poverty is not due to shortcomings in program design or administration, but rather because low-income households typically do not wish to leave their current neighborhoods, despite aggregate statistical indicators that may suggest that they are “disadvantaged” or even “dysfunctional” places.55 The residents’ purported reasons for wishing to stay include deep place attachments,56 strong kin and friend networks,57 preferences for race-class homophily,58 and ability to negotiate the microspaces within seemingly undesirable neighborhoods to obtain safety, comfort, community, and, ultimately a modicum of residential satisfaction.59

I do not doubt that some, perhaps even many, low-income residents of concentrated poverty neighborhoods evince many of the aforementioned attributes. To admit this does not, however, challenge the desirability and likely efficacy of reforms along the lines suggested above, for two reasons. First, according to the behavioral economics and psychology I reviewed in chapter 5, virtually everyone manifests a status quo bias: a tendency to overvalue present circumstances in comparison to alternatives.60 It typically takes substantial incentives, which are not present or are perverse in current assisted-housing programs, to induce a substantial change in place of residence. It is neither a matter of “preference” nor of “choice,” but rather of inertia. Second, residents’ preexisting preferences are not immutable, but instead are contingent on experience. Since so few low-income residents in high-poverty neighborhoods (or their parents) have ever experienced high-quality, safe neighborhoods with functional school systems,61 their expectations become leveled: they expect all prospective neighborhoods to suffer from the same maladies, so they perceive little prospective gain from moving. Recent evidence from the Baltimore Housing Mobility Program (BHMP), garnered by Stefanie DeLuca, Peter Rosenblatt, and colleagues, powerfully demonstrated this point.62 They found that poor black families’ exposure to economically and racially diverse neighborhoods with better safety and schools changed their preferences regarding future moves, because of the positive experiences their children had living in these places. This seminal research demonstrates how social structure, personal experience, and policy opportunities influence stated and revealed preferences.

Importantly, the BHMP involves many of the components I have advocated previously. Postmove counseling, especially regarding potential second moves, and information about school quality in better neighborhoods were crucial elements of success not present in previous demonstrations like Gautreaux or Moving to Opportunity, let alone the standard voucher program. Regional administration meant that tenants did not need to negotiate with PHAs to “port out” their vouchers for use in a suburban location. Landlord recruitment meant that tenants were rarely discouraged by prospective landlords turning them away.63 BHMP represents an invaluable prototype for key components of a reformed HCV program that would constitute the centerpiece of a neighborhood-supportive policy.

Encouraging Racially Diverse Neighborhoods

The final domain of a comprehensive neighborhood-supportive policy is a suite of programs for enhancing racial diversity. I advocate these programs because they represent gradualist, option-enhancing, voluntary (but incentive-driven) initiatives. Collectively, they aim at achieving a stable integrative process (SIP) in targeted neighborhoods.

Programs for Encouraging a Stable Integrative Process

SIP is a housing market dynamic in which dwelling seekers representing two or more races actively seek to occupy the same vacant dwellings in a substantial proportion of a jurisdiction’s neighborhoods over an extended period. The meaning of “substantial portion” depends on the particulars of the geographic context. Those metropolitan areas having relatively few minorities might expect that SIP would mean that a smaller fraction of their neighborhoods would exhibit active demands by two or more races. SIP is thus consistent with a variety of diversity racial occupancy outcomes across neighborhoods, and of intertemporal changes in these outcomes. “Integration” is thus a flexible, contingent construct from the perspective of SIP.64

It would be mistaken to view the goal of SIP in terms of precise percentages of various racial groups living in neighborhoods that constitute a static outcome called “integration.” All we can say definitively about the outcome of SIP is that it would tend over time to desegregate racially homogeneous areas and promote more racially diverse ones. Homogeneous neighborhoods could not remain so indefinitely, and diverse neighborhoods would tend to remain so, if a racially diverse set of households with comparable willingness and ability to compete for the dwelling greeted each vacancy.

Perhaps one can more clearly understand SIP by contrasting it with its opposite: a process in which only dwelling seekers of one race actively seek to occupy vacant dwellings in a particular neighborhood. Such a segregative process leads to one of two alternatives. If the race of the in-movers perpetually matches that of the out-movers, stable racial segregation will persist. If the race of the in-movers differs over an extended period from that of the out-movers, temporary racial integration results, followed inevitably by transition and resegregation. SIP seeks to avoid producing these two outcomes through its component programs, which are described next.

Enhanced fair housing enforcement. Policies to deter differential treatment discrimination by housing and mortgage market agents are required if minorities are to be free to exercise their neighborhood choices as their economic circumstances and preferences would dictate. This does not mean merely enhancing existing penalties for violators, increasing outreach to inform victims of their rights and means of redress, improving the speed of case adjudication, or expanding civil rights training of those involved in the various urban market contexts where discrimination occurs, although we can applaud all such efforts. Rather, enhancing deterrence requires an enforcement strategy based on vastly intensified matched-testing investigations conducted by civil rights agencies that create a viable obstacle to discrimination. The fundamental flaw in the federal Fair Housing Act of 1986 (strengthened in 1988) is that it relies on the victim to recognize and formally complain about suspected acts of discrimination.65 Due to the subtlety of discrimination as it is typically practiced today, such reliance is misplaced. As a result, there is little chance of violators fearing detection or litigation, and consequently there is minimal deterrence. Effective deterrence requires a substantial commitment of resources to empower private and governmental fair housing agencies to conduct ongoing enforcement testing programs, which employ pairs of matched investigators who pose as housing or mortgage seekers. These enforcement testing programs would not merely respond to complaints of alleged victims, but would provide an ongoing presence in areas rendered suspicious by other evidence or, resources permitting, in areas randomly located throughout the market.66 Only through such a comprehensive enforcement testing policy, backed up by legal suits exacting heavy penalties, can people prone to discriminate be deterred from using race to constrain the opportunities of others.67 Significant increases in funds and concomitant expansion in the geographic scope of enforcement testing will be required, however, if this strategy is to create a credible deterrent to differential treatment discrimination in housing and mortgage markets.

Affirmative marketing. Affirmative marketing is advertising that through content, medium, and distribution tries to increase the attractiveness of particular properties or neighborhoods in the perceptions of households who are members of racial groups that are currently underrepresented in the area being addressed. The key facet of affirmative marketing is that it explicitly directs its encouragement toward a particular group of households whose increased representation is vital for achieving SIP. Though superficially this might appear to be a version of “steering,” the US Supreme Court has upheld the selective provision of housing market information based on the race of the home seeker and the race of the neighborhood if the goal is affirmative marketing and desegregation.

Real estate counseling services. Local jurisdictions or nonprofit organizations could sponsor agencies designed to provide free information to prospective renters and homebuyers about communities in which their racial group is underrepresented. Counseling would include firsthand tours of targeted neighborhoods, preferably with the races of the client and counselor matched. The counselors in such agencies, who have themselves lived in diverse areas and whose children attend integrated schools, are key to making this programmatic component successful. While taking prospective in-movers to schools, shopping areas, recreation facilities, and other community amenities in targeted areas, there is considerable advantage in being able to invite a person of the same race to experience what you have.

Financial incentives. Policymakers should institute a variety of financial incentives to encourage households to move into neighborhoods where their actions would promote SIP there. In chapter 9 I demonstrated that more racially diverse neighborhoods would generate positive social externalities; incentivizing individual actions to move in pro-diversity ways offers a straightforward and voluntary means of achieving this. Several forms of such pro-SIP financial incentives have been used in the past. Many municipalities across the country have offered low-interest second mortgages (sometimes granting deferred payment until time of sale) to buyers of homes in neighborhoods where their racial group has been deemed underrepresented by local policymakers.68 During the 1980s the state of Ohio earmarked a pool of low-interest mortgage loans for exclusive use by first-time, low-income homebuyers of all races who agreed to purchase in neighborhoods designated by the state for pro-diversity purposes. Oak Park, Illinois, developed a repair grant program for landlords of rental buildings who were able to achieve SIP. Various levels of government could offer grants or tax credits aimed at defraying moving costs when households’ moves into neighborhoods increased the racial diversity there, based on the latest American Community Survey data.

Ancillary activities. Community activities related to neighborhoods’ and schools’ social capital, infrastructure, and quality ideally can reinforce the aforementioned pillars of a pro-diversity strategy.69 Community organizing should be encouraged, probably at the block or large-building level, so that interracial networks are built and nurtured. If possible, the public sector must maintain and enhance the quality of its infrastructure, to defuse stereotypes about how racial diversity leads to deterioration of the public realm. Public school administrators also should coordinate carefully with housing diversity administrators so that their actions are mutually reinforcing. School administrators might well adjust boundaries of catchment areas to avoid the creation of predominantly white and predominantly minority school buildings. Of course, the quality of public education must be a top priority.

What if People Prefer to Live in Racially Homogeneous Neighborhoods?

In the earlier discussion of policies encouraging economic diversity of neighborhoods, I acknowledged and then challenged a contrary position alleging that low-income households did not support such efforts. In the realm of racial diversity policies, there is an analogous critique: many households, especially disproportionate numbers of whites, prefer neighborhoods overwhelmingly comprised of residents of their own racial group.70 Because of these supposedly “natural,” immutable preferences, the argument goes, policies such as those I have advocated are neither appropriate nor efficacious. There is substantial support from public opinion polls and analyses of residential mobility patterns that indeed many households wish to self-segregate, as I documented in chapter 8. What is fallacious in this argument is that these preferences are somehow “natural” or unalterable. On the contrary, as the aforementioned work by Stefanie DeLuca and colleagues has shown definitively, social structure, personal experience, and policy opportunities influence stated and revealed preferences for neighborhood attributes.71

In the case of racial segregation, it is obvious that the legacy of generations of legal, and then illegal but still widespread, housing and mortgage market discrimination created a potent stereotype about what desegregation and racially diverse neighborhoods meant. Discriminatory barriers in white communities (restrictive covenants, exclusionary practices by agents and lenders, etc.) conspired to overcrowd minority households into the oldest, most decrepit parts of central cities, where unscrupulous landlords extracted excessive rent for badly undermaintained dwellings. Historically, the entrance of a few minority people into a formerly all-white neighborhood (often adjacent to the minority one) meant that lenders would start to redline the area, blockbusters would move in to scare away white homeowners, and real estate agents would start steering away prospective white in-movers while steering in prospective minority ones. Thus, neighborhoods rapidly tipped from homogeneous-white to homogeneous-minority status. Heightened social tensions, violence, disrupted social networks, and losses of whites’ home equity often accompanied this spasmodic tipping. Then the process of physical decay would progress in this newly annexed neighborhood of minority occupancy for all the aforementioned reasons, and the process would continue. Due to this discriminatory legacy, it is also predictable that many minority households would view white neighbors as being potentially hostile to their presence, and would thus express a “preference” for minority communities. With our racist history, it is no wonder that many households, whites and minorities alike, hold negative attitudes about what it means to live in racially diverse neighborhoods! Indeed, this legacy is the basis of the current power of racial composition as a signal for what the future of the neighborhood holds, as I explained in chapter 5.

Legacy need not be destiny. The way desegregation has transpired in the past is not a guide for how it must work in the future. We cannot stop the momentum of our discriminatory history and its associated stereotypes, however, merely by adopting a race-neutral policy stance and ceasing to discriminate. We must adopt pro-diversity policies to encourage a process of residential selection that confounds the conventional stereotypes and promotes neighborhoods that are racially diverse yet also stable, of high quality, and hospitable to all. The evidence is clear that if people can experience such environments, their attitudes about race and diversity change markedly.

The relevant body of social psychological literature here relates to the notion of equal-status residential contact, which I introduced briefly in chapter 9. This long-standing tenet of intergroup relations is that racial prejudice can be reduced if particular sorts of interracial contacts can be promulgated. To have this impact, such contacts must be (1) sustained; (2) noncompetitive; (3) personal, informal, and one-to-one; (4) approved by the relevant public authorities; and (5) designed to confer equal status on both parties.72 Racially diverse neighborhoods produced by SIP fulfill all these conditions. Neighbors typically share common community concerns. They are most likely to develop interpersonal relationships because of sustained propinquity. Because public policy promoting SIP is not tantamount to mixing races of radically different socioeconomic class backgrounds, the interracial contact will be officially sanctioned and equal-status in nature. The empirical evidence has consistently shown that equal-status interracial contact causes a substantial reduction in whites’ prejudices, especially regarding their desire to have only other whites as neighbors.73

Is a Successful Racial Diversity Program Possible?

It is fair to ponder whether multifaceted SIP policy holds much promise for unraveling generations of racist public and private policy that has embedded segregation in our history.74 I believe that my proposal does hold promise of efficacy, and that the city of Shaker Heights, Ohio, offers an encouraging case study in this regard. Shaker Heights is an independent municipality of about thirty thousand residents abutting Cleveland on its southeastern side. It has considerable diversity in the types and cost of its housing stock, of which about a third is renter-occupied. In the late 1950s, its leaders realized that the rapid growth of the black population in Cleveland’s eastern core was generating the classic pattern of neighborhood racial tipping described above, and would soon threaten to continue the same in Shaker Heights, as it has in a few other eastern suburbs. In response, the city enacted a comprehensive strategy for achieving SIP that ultimately included all the components I have described.75 Fortunately, a wider alliance of eastern Cleveland suburbs joined in some of the Shaker Heights programs.

By multiple indicators, SIP has worked in Shaker Heights.76 According to the 1960 census, the city’s population was only about 1 percent black and 99 percent white. Racial diversity in several dimensions steadily grew over the next half century, until by 2014 its population was 55 percent white, 34 percent black, 7 percent Asian, and 3 percent Hispanic. I showed in a statistical analysis that Shaker Heights neighborhoods initially occupied exclusively by whites had much larger increases in black residents than would have been predicted on the basis of patterns evinced elsewhere across the encompassing county for a similar type of housing stock. Similarly, its neighborhoods already having substantial numbers of black residents at the beginning of the study period exhibited larger numbers of new white home seekers than would have predicted otherwise. In other words, SIP emerged both in erstwhile stably segregated white neighborhoods, and in racially mixed neighborhoods that normally would have been unstable and transitory.77 Shaker Heights has also exhibited a long-term pattern of home price appreciation that has been far superior to that of the surrounding county as a whole. Brian Cromwell evaluated the city’s pro-SIP loan program, and found that it produced a significant stabilizing effect on racial composition and home appreciation in neighborhoods that under normal circumstances might have tipped rapidly to predominantly black occupancy.78 Importantly, Cromwell interpreted his results as indicating that the Shaker Heights SIP financial incentive program confounded the conventional signaling effect of racial composition on white housing demanders’ expectations of the area’s future.

Synergisms among Neighborhood-Supportive Policies

Multiple synergisms and complementarities emerge when we consider holistically the menu of neighborhood-supportive policies I have advocated. Consider first the realm of increasing economic diversity. From the perspective of HCV holders, the constraint to limit their search in neighborhoods eligible under impaction standards will be offset by SAFMRs, enhanced mobility counseling, expanded search periods, affirmative landlord recruitment, and the addition of source of income as a fair-housing protected class. Residents in high-opportunity neighborhoods will be less likely to oppose (and fear the potential consequences of) assisted households as new neighbors if they know there are strictly enforced and consistently applied impaction standards across all neighborhoods of the region. Similarly, nonassisted residents in high-opportunity neighborhoods will be less likely to flee or avoid neighborhoods with assisted households if they know those circumstances are widely represented in virtually all neighborhoods. Landlords in high-opportunity neighborhoods will have fewer concerns about renting to HCV holders, since they will not only receive appropriate SAFMRs but will know that impaction standards will automatically restrict the number of such households they can have in their building.

Useful synergisms could also arise if communities creatively integrated their programs for improving the physical condition of target neighborhoods with those aiming to increase their diversity. For example, tax-foreclosed homes often become undermaintained and, in severe cases, abandoned. When such properties are located in otherwise decent-quality neighborhoods, policymakers can target them as vehicles for pro-diversification programs. For example, they can be acquired by local government or private nonprofit agencies to operate as scattered-site affordable rental housing, thus enhancing the area’s economic diversity. The Denver Housing Authority’s “dispersed housing” program successfully employed such a scheme, which has boosted property values near rehabilitated, formerly foreclosed properties.79 Concomitantly, policy makers could affirmatively market these properties as appropriate, to enhance the area’s racial diversity. Housing code enforcement, coupled with need-based financial assistance, could be concentrated on neighborhoods with increasing shares of minority in-movers produced by SIP policies. This intent of this enforcement would be to confound conventional wisdom about the relationship between neighborhood diversification and declining residential quality.

The Rationale for Circumspect Policy: Caveats, Constraints, and Potential Pitfalls

In the title of this chapter, I have used the adjective “circumspect” to describe my proposed neighborhood-supportive suite of policies. I did not choose this word without considerable intention, because wise policy making in this realm requires a keen appreciation of the limitations as well as the potentials for neighborhood interventions. There are at least seven reasons for circumspection.

Limited Efficacy of Governmental Interventions Compared to Driving Forces

My metropolitan housing submarket model makes it clear that the fundamental drivers of neighborhood change—which are primarily economic, demographic, and technological—are not within the control of local governments. Many drivers, such as change in communication, transportation, and energy technologies and most international economic forces, are largely beyond the control of a nation-state, let alone an individual state, regional planning organization, or municipality. At best, these lower levels of government can make only modest direct adjustments (via regulations or economic incentives) and indirect supplements (via their public service and tax packages) in how the market drives resource flow among the neighborhoods within their purview. These public interventions typically pale in power compared to the larger external forces impinging, and therefore are unlikely to change the overall course of all neighborhoods for which they may be stewards.

The case studies of Detroit and Los Angeles presented in chapter 4 illustrate my point. When a city loses most of its economic base and population declines dramatically, many of its neighborhoods will decay and many will become abandoned. The city and probably even the state governments would not be in a position to target sufficient resources to reverse such declines universally. Conversely, when an older city gets a new injection of its economic base and people clamor to move in, even modest-quality neighborhoods will witness upward succession and physical rehabilitation without the local government needing to do anything. In the face of these overwhelming large-scale external forces, government interventions have relatively limited efficacy. The implication is that policy makers should take care not to intervene in the face of overwhelmingly contrary market forces, and should keep their expectations for success modest.

Potential for Zero-Sum Policy Impact

Even if public interventions are sufficiently powerful to change the trajectory of a neighborhood in a desirable direction, another potential pitfall lurks. The augmented private resources (financial and household flows) invested in the target neighborhood may merely have been siphoned from other neighborhoods with which the target was competing, thus creating a zero-sum effect for the jurisdiction’s neighborhoods in aggregate.

Zero-sum policy outcomes are most likely when a program improves the absolute attractiveness of a target area enough to alter migration flows so that somewhat higher-income, better educated households move in. This in turn would change the aggregate household socioeconomic and tenure characteristics of the target area, and thus increase aggregate reinvestment behavior there. From the myopic view of the target neighborhood, this seems like an unvarnished success. However, is this ultimately sensible from the jurisdiction’s perspective? Certainly not if the net result is a mere reshuffling of residents across different neighborhoods within the same jurisdiction. In such a case, there is a zero-sum outcome: upward succession and improvements in dwelling upkeep in targeted areas is exactly offset by downward succession and declines in upkeep in nontargeted areas.