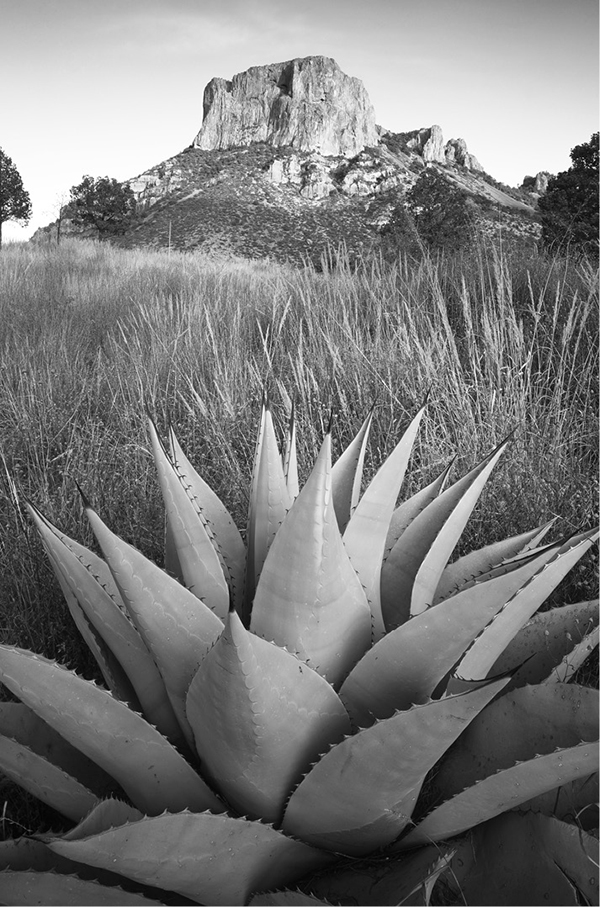

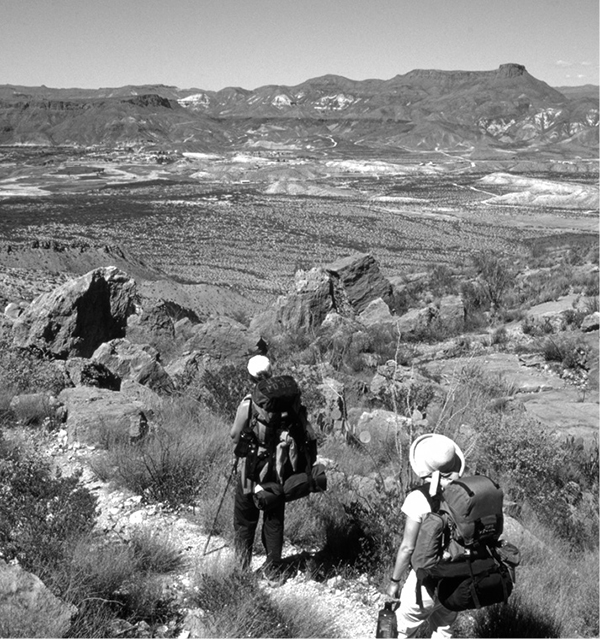

An agave grows below Casa Grande, one of the most notable peaks in the Chisos Mountains of Big Bend National Park.

Hiking in Texas, an Introduction

Texas forms an enormous bridge between east and west, from the Deep South on the Louisiana border to the Old West in El Paso. Follow I-10 for the 855 miles from El Paso to Orange and you pass from the arid mountains and basins of the Chihuahuan Desert to the lush, fetid bayous of the Big Thicket. The change from north to south is no less extreme. On a given winter day, residents of Brownsville may be sweating in the citrus groves of the Rio Grande Valley while Amarillo shivers under 2-foot drifts of snow.

People unfamiliar with the state often believe that Texas is little more than flat desert, grazed by underfed cows and dotted with oil wells. However, Texas’s tremendous size and wide elevation range create a surprising variety of climates, vegetation, and terrain. East Texas receives 50 or more inches of rain annually and is covered with a mosaic of lakes and rivers. Bald cypresses and water tupelos line the swampy bayous, while dense pine forests blanket the uplands. Spanish moss festoons the live oaks, while fragrant magnolia blossoms perfume the air.

A visit to West Texas will convince skeptics that Texas is far from flat. Texas may not have the high elevations common in the western states, but the highest point, Guadalupe Peak, still reaches a respectable 8,749 feet. Its steep slopes and sheer cliffs tower a vertical mile above the salt flats at its base. Numerous other mountain ranges pepper West Texas, with many peaks reaching 7,000 feet or more.

Live oaks and junipers cloak the rolling terrain of the Hill Country, in the center of the state. Crystal-clear streams tumble down canyons cut through the limestone plateau. Secret places lie hidden in the folds of the hills: the fiery red maples of the deep canyons of the Sabinal River, the labyrinthine Caverns of Sonora, the pink granite dome of Enchanted Rock.

The Panhandle also guards its secrets. The Canadian River breaks the endless flat plain into a series of slopes and gullies. The Prairie Dog Town Fork of the Red River cuts an 800-foot-deep gash known as Palo Duro Canyon. Gnarled junipers cling to the red-and-ocher slopes of the canyon. Hidden side canyons and eroded pinnacles belie the stark treeless plains above.

An agave grows below Casa Grande, one of the most notable peaks in the Chisos Mountains of Big Bend National Park.

Elevation, the presence of the Gulf of Mexico, and the sheer size of the state largely control climate in Texas. The Gulf provides a moisture source and moderating influence on the coastal areas of the state. Overall, Texas is a warm state because of its low latitude and generally low elevations. However, the Panhandle, because of its far northern reach, and the mountains of West Texas get at least a few short-lived snows every winter.

The state is noted for the diversity of its weather. No mountains block the flow of cold fronts from Canada in winter, so occasional northers interrupt the warm weather and bring surprising cold spells even in the southern part of the state. The northers sweep in suddenly, dropping temperatures 30 or 40 degrees overnight. Historical temperature extremes in Texas run an incredible range, from -23 degrees to 120 degrees Fahrenheit.

In spring, cold fronts collide with warm moist Gulf air and create tornadoes and severe thunderstorms. Fall can bring hurricanes to the coast. The September 1900 hurricane that hit Galveston claimed over 6,000 lives, making it the worst natural disaster in American history. Fortunately, Texas weather is rarely extreme enough to hinder outdoor activities. All the hikes in this guide can be done year-round, although some seasons will be more pleasant than others.

Except for West Texas, most of the state is fairly heavily populated and developed. Because of Texas’s status as an independent republic before it joined the United States, little land remains in public hands. Thus, the only area of the state with large areas of accessible wilderness lies in West Texas. Because of their large size, Big Bend and Guadalupe Mountains National Parks are the premier wild areas of the state open to the public. However, Texas has many state parks with beautiful scenery and hiking trails. Quite a few of this guidebook’s hikes are within the two national parks, but the majority are scattered across all parts of the state.

I’ve included popular hikes, such as the South Rim at Big Bend, but also many obscure hikes, such as Matagorda Island. All the hikes but one lie on public land, chiefly the state parks, national forests, and national parks. One hike crosses a Nature Conservancy preserve. The vast majority of trailheads are accessible by any type of vehicle; only a few require high clearance or four-wheel drive.

If you are a beginning hiker, don’t let the length of some of these hikes intimidate you and restrict you to only the short ones. Most of the long hikes are beautiful and rewarding, even if you only go 0.5 mile down the trail. Although the trails in this guide may keep you busy for years, many of the hike descriptions suggest additional nearby routes or extensions of the described hike. Don’t be afraid to try them. This book serves best as an introduction to many of the most beautiful backcountry areas of Texas.

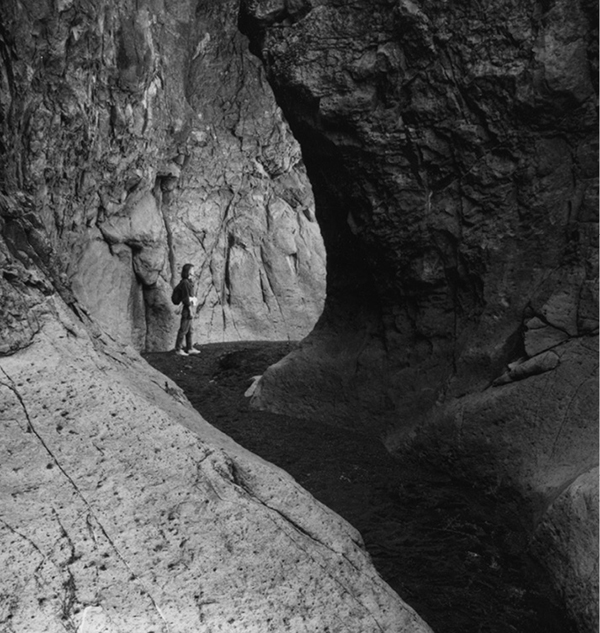

A closed canyon—rare in Texas—forms a narrow slot through the rock.

How to Use This Guide

Hiking Texas describes eighty-five hikes scattered widely across the state of Texas. The map at the start of this book indicates their locations. The map information was taken from U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) topo maps, national forest maps, state park maps, national park maps, and other land management maps.

In addition to a map showing the trail, each hike begins with a brief description of the hike and other information to help you select the right hike for your time and ability.

After reading the descriptions, pick the hike that appeals to you most. Go only as far as ability and desire allow. There’s no obligation to complete any hike. Remember, you are out hiking to enjoy yourself, not to prove anything.

Distance

The distance specified in each description is listed as a round-trip distance from the trailhead to the end of the route and back. As mentioned in the individual hike descriptions, some of the hikes work well with car shuttles. Setting up shuttles with two cars can halve the out-and-back mileage of some of the walks. Alternatively, someone can pick up your group at a set time at the end of the route. Another method involves splitting the group, dropping off the first half at one end, and parking the car and starting the other half from the other end of the hike. When the two groups meet in the middle, they exchange car keys, allowing the first group to later pick up the second. All hike mileages assume, however, that you are unable to arrange a shuttle.

Hike lengths have been estimated as closely as possible using topographic maps and government measurements. However, the different sources do not always agree, so the final figure is sometimes the author’s best estimate of the actual distance.

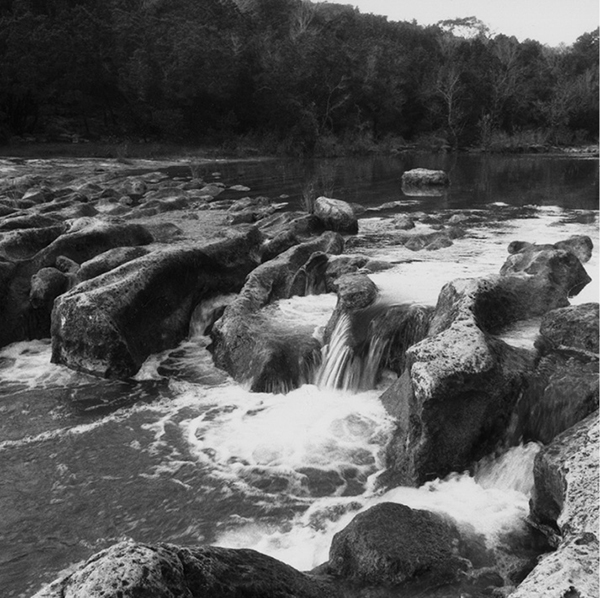

The rushing waters of Barton Creek sculpt a limestone ledge.

Approximate Hiking Time

Everyone hikes at a different pace, and this varies considerably. In general, a hike is loosely classed as a day hike if most reasonably fit people can easily complete it in one day or less. Likewise, most reasonably fit people can easily do a two- or three-day hike in two or three days. Many hikes have attractions that make them worthy of longer, relaxed stays. A few of the day hikes, particularly in some of the National Park Service areas, must be done in a day because overnight camping is not allowed.

For any given hike, the approximate hike time is a subjective estimate because of different hiking styles and fitness levels. To come up with this information, I estimated that most people hike at 2 to 3 miles per hour. For longer hikes with more elevation changes, I estimated closer to 2 miles per hour. For short, flat hikes, 3 miles per hour is easily attained. I also tried to take into account other factors such as a rough trail or particularly big elevation changes. Carrying a backpack for overnight trips will add significantly to the time required.

Elevation

Elevation is generally the most important factor in determining a hike’s difficulty. The two numbers listed are the highest and lowest points reached on the hike. Often, but not always, the trailhead lies at the low point and the end lies at the highest point. With canyon hikes, the numbers are sometimes reversed. Many of the hikes in West Texas have a fairly steady climb going out and a fairly steady downhill coming back. Some of the hikes have several ups and downs on the way, requiring more elevation gain and effort than the high and low numbers indicate. The hikes along the coast and in South and East Texas generally have very minimal elevation changes.

Absolute elevation also affects difficulty. At high elevations, lower atmospheric pressure creates “thin air” that requires higher breathing rates and more effort to pull enough oxygen into the lungs. Since most of Texas lies at low elevations, hikers will encounter thin air on only a few of the hikes in this guide. The moderately high elevations encountered on hikes in the Chisos, Franklin, Davis, and particularly the Guadalupe Mountains will require only a little additional effort. Physically fit hikers coming from low elevation areas should acclimate easily within two or three days.

Difficulty

Assessing a hike’s difficulty also is very subjective. The elevation, elevation change, and length all play a role, as do trail condition, weather, and the hiker’s physical condition. However, even my subjective ratings will give some idea of difficulty. To me, elevation gain was the most significant variable in establishing levels of difficulty. Most of the hikes, except in West Texas, have only small elevation gains and are rated easy or moderate. The majority of the difficult hikes are located in West Texas. In general, if a hike gains less than 1,000 feet and is less than 8 miles round-trip, I usually rated it as easy. Within each category there are many degrees of difficulty, of course. Obviously a 2-mile hike gaining 200 feet is going to be much easier than an 8-mile hike gaining 900 feet. Moderate hikes usually gain somewhere between 1,000 and 2,000 feet and run longer than 8 miles. The strenuous hikes usually gain over 2,000 feet and are fairly long. Poor trails, excessive heat, high elevations with thin air, cross-country travel, and other factors may result in a more difficult designation than would otherwise seem to be the case from simply the elevation change and trail length. Carrying a heavy backpack can make even an “easy” day hike fairly strenuous.

Trail Surface

Most of the hikes in this guide have a single-track dirt surface in reasonable condition. Some are paved or follow boardwalks; a few follow roads. At least three are rough cross-country routes with no trail at all.

Best Season

The season specified for a hike is the optimum or ideal season. Since snow does not stay on the ground for extended periods in Texas, all the trails in this guide can be hiked any time of year. However, since the state is usually hot in summer, the other three seasons generally provide the best weather for hiking. To escape the heat in summer, go to the West Texas mountains or pick a hike with a good swimming hole. Spring is the rainy season in Central and East Texas but is still an excellent time to hike, with pleasant temperatures and fields of wildflowers. The rains fall in West Texas from July through September but are short-lived and bring cooler temperatures. A few snows fall every year in the mountains and the Panhandle, but they usually melt off within a day or two. Spring can be dry and windy in West Texas, making desert hikes unpleasant at times. Fall is probably the premier time for hiking anywhere in the state. Always check weather forecasts before starting your hike.

Water Availability

Sources of water are listed if they are known to usually be reliable. Any water obtained on a hike should be purified before use. Be sure to check at park or forest headquarters on the condition of water sources before depending on them. Droughts, livestock and wildlife use, and other factors can affect availability.

Land Status

This section lists the landowner, usually a government agency, that manages the land on which the hike lies.

Nearest Town

The closest town to the hike with at least a gas station and some basic supplies is listed here.

Fees and Permits

Permits are not usually required to hike in Texas parks and forests, although most have a small park entry fee. Several of the National Park Service areas and state parks allow only day use on certain trails. Generally all National Park Service areas and state parks require a permit for overnight trips. In most areas a fee is required for overnight camping.

Maples and madrone trees abound in Texas, these in Guadalupe Mountains National Park’s Dog Canyon, Hike 16.

Maps

The maps in this guide are as accurate and current as possible. When used in conjunction with the hike description and the additional maps listed for each hike, you should have little trouble following the route.

Generally, two types of maps are listed. Most of the state parks have excellent park and hiking maps available free at the entrance station or headquarters. The national forest maps usually show the trails but, because of their small scale, rarely give enough detail to be especially helpful. However, they are very useful for locating forest roads, trailheads, and campgrounds. They are generally more current than the USGS topographic maps and usually show the level of improvement of the forest roads.

Most of the National Park Service areas have maps or brochures showing the trails. Excellent Trail Illustrated maps are available for Big Bend and Guadalupe Mountains National Parks. USGS topographic quadrangles are generally the most detailed and accurate maps available of natural features. With some practice they allow you to visualize peaks, canyons, cliffs, rivers, roads, and many other features. With a little experience, a topographic map, and a compass, you should never become lost. All the USGS maps noted in this guide are 7.5-minute quads.

USGS quads are particularly useful for little-used trails and off-trail travel. Unfortunately, many of the quadrangles, particularly for less-populated parts of the state, are out of date and do not show many newer man-made features such as roads and trails. However, they are still useful for their topographic information. Many of the more developed hikes in this guide do not require a topo map. The park and forest maps that are usually available at park headquarters and at many outdoor shops in the larger cities will suffice on those trails. A GPS unit also helps on off-trail hikes.

USGS quads can usually be purchased at the same outdoor shops or ordered directly from USGS at http://store.usgs.gov. To order from USGS, know the state, the number desired of each map, the exact map name as listed in the hike heading, and the scale.

Trail Contacts

This listing provides the address and phone number of the land manager for the specific hiking trail. Usually it’s a state park, national park, national forest, wildlife refuge, or city park.

Finding the Trailhead

This section provides detailed directions to the trailhead. With a basic current state highway map, you can easily locate the starting point from the directions. In general, the nearest town is used as the starting point. Texas has two levels of state highways. The busier, more important roads are designated as Texas highways and use the abbreviation TX in this guide. The smaller, less busy tier of paved state highways is designated as the Farm-to-Market and Ranch-to-Market road system. In this guide I use the common abbreviations FM and RM for these roads.

Distances were measured using a car odometer. Realize that different cars will vary slightly in their measurements. Even the same car will read slightly differently driving uphill on a dirt road versus downhill on a dirt road. Be sure to keep an eye open for the specific signs, junctions, and landmarks mentioned in the directions, not just the mileages.

Most of this guide’s hikes have trailheads that can be reached by a sedan. A few, as noted, require a high-clearance vehicle. Except in wet or snowy weather, none usually require four-wheel drive. Rains or snows can temporarily make some roads impassable. Before venturing onto unimproved dirt roads, you should check with park or forest headquarters. On less-travelled back roads, particularly at Big Bend, you should carry basic emergency equipment such as a shovel, chains, water, a spare tire, a jack, blankets, and some extra food and clothing. Make sure that your vehicle is in good operating condition with a full tank of gas.

Theft and vandalism occasionally occur at trailheads. The local park rangers or sheriff can tell you of any recent problems. Try not to leave valuables in your car at all; if you must, lock them out of sight in the trunk. If I have enough room, I usually put everything in the trunk to give the car an overall empty appearance. In my many years of parking and hiking at remote trailheads, my vehicle has never been disturbed.

The Hike

All the hikes selected for this guide can be easily done by people in good physical condition. A few may require a little scrambling, but none require any rock climbing skills. A few of the hikes, as noted in their descriptions, travel across country or on very faint trails. You should have an experienced hiker, along with a compass and USGS quad and possibly a GPS unit, with your group before doing those hikes.

Trails are often marked with rock cairns or blazes. Most of the time the trails are obvious and easy to follow, but the marks help when the trails are little used and faint. Cairns are piles of rock built along the route. Tree blazes are I-shaped carvings on trees, usually at shoulder or head height. Don’t add your own blazes or cairns; it can confuse others traveling the route. Leave such markings to the official trail workers. Sometimes, especially in East Texas forests, small plastic or aluminum markers are nailed to trees to mark the route.

Possible backcountry campsites are often suggested in the descriptions. Many others are usually available. In the national forests, there are usually few restrictions in selecting a campsite, provided that it is well away from the trail or any water source. Most of the state and national parks require that certain backcountry campsites be used. The state parks charge a small fee; the national parks generally do not.

Miles and Directions

To help you stay on course, a detailed route finder sets forth mileages between significant landmarks along the trail.

Wilderness Ethics

A few simple rules and courtesies will help in both preserving the natural environment and allowing others to enjoy their outdoor experience. Every hiker has at least a slight impact on the land and other visitors. Your goal should be to minimize that impact. Some of the rules and suggestions may seem overly restrictive and confining, but with increasing use of shrinking wild areas, such rules have become more necessary. All can be followed with little inconvenience and will contribute to a better outdoor experience for you and others.

Camping

Camp at least 100 yards away from water sources. The vegetation at creeks, lakes, and springs is often the most fragile. Camping well away prevents trampling and destruction of plant life. Such destruction can lead to erosion and muddying of water sources. Additionally, camping 100 yards away from water sources limits runoff of wash water, food scraps, and human waste. An advantage to dry camps is that they are usually warmer and have fewer insects. Additionally, in desert areas a spring may be the only water source for miles. If you camp too close, you may keep wildlife from reaching the water they need to survive.

Pick a level site that won’t require modification to be usable. Don’t destroy vegetation in setting up camp. The ideal camp is probably on a bare forest floor carpeted with leaves or pine needles. Don’t trench around the tent site. Choose a site with good natural drainage. If possible pick a site that has already been used so that you won’t trample another. If you remove rocks, sticks, or other debris, replace them before you depart. You want to leave no trace of your visit.

Don’t pitch your tent right next to someone else’s camp. Remember, they are probably out in the woods to get away from people, too. Set up camp out of sight of trails and avoid creating excessive noise.

If backcountry toilets are available, use them. Many state parks have composting or chemical toilets at backcountry campsites. If no toilets are available, dig a 6- to 8-inch-deep hole as far away from water, campsites, and trails as possible and completely bury human wastes. At that depth, waste material will quickly decompose. Carry out the toilet paper with you in plastic bags. If you catch and eat fish, bury the entrails. Don’t dispose of them in the water.

Hikers need to be sensitive to the fragile nature of the backcountry environment. Big Bend National Park.

Animals will dig up any garbage that you bury, so carry out all trash that hasn’t been burned completely. Food containers are much lighter once the contents have been consumed and are easy to carry. Improve the area for future visitors by taking out trash others have left behind.

Campfires leave permanent scars. If you must build one, do it on bare soil without a fire ring. Use only dead and fallen wood. Put your fire out thoroughly with water and never leave it unattended. Buried fires can sometimes escape from under the soil. Don’t start a fire on dry or windy days. The national forests often limit campfires during dry periods. Be sure to honor the restrictions.

Don’t build fires in areas, such as the desert, where wood is obviously scarce. For cooking purposes, backpacking stoves are much easier, quicker, and more efficient.

Carry an extra empty gallon jug or washbasin to use for washing yourself or kitchen utensils. Use the jug to carry water and wash well away from the water source to keep soap and other pollutants out of the water.

The Trail

Don’t shortcut switchbacks on the trail. Switchbacks were built to ease the grade on climbs and to limit erosion. Shortcutting, although it may be shorter, usually takes more effort and unquestionably causes erosion.

Always give horses and other pack animals the right-of-way. Stand well away from the trail and make no sudden movements or noises that could spook the animals.

If you smoke, stop in a safe spot and make sure that cigarettes and matches are dead out before proceeding. Take your butts with you, and don’t smoke in windy and dry conditions.

Motorized and mechanized vehicles, including mountain bikes, are prohibited from all wilderness and most national park trails. Other areas may also have restrictions. Some state parks have multiple-use trails for hikers, mountain bikers, and equestrians. Common sense and courtesy will prevent conflicts.

Don’t do anything to disturb the natural environment. Don’t cut live trees or plants. Resist the temptation to pick wildflowers. Don’t blaze trees, carve initials on rocks, build bridges, or add improvements to campsites. Don’t remove any Indian relics or other historic items. All such artifacts are protected by law on government lands.

It’s probably best to leave your pet at home, but if you take your dog, please be courteous. Dogs often annoy other hikers seeking a wilderness experience, so leash him if other hikers are around. Keep your dog away from water sources to avoid possible pollution, and prevent him from disturbing wildlife. Keep him quiet, especially at night.

National Parks

Rules in National Park Service areas are generally more restrictive than in other federal lands. Some park areas do not permit backcountry camping. Others require campsites to be located in specific areas. All require that overnight permits be obtained. Dogs are not allowed on trails, and no plants, rocks, or other items may be removed. Use of campfires is usually more restricted. Because of perennially dry conditions and lack of wood, Big Bend and Guadalupe Mountains National Parks prohibit the use of campfires altogether. Hunting is prohibited in parks, but fishing is usually permitted with appropriate state licenses.

Other restrictions may apply at certain areas. The local park headquarters and signs at trailheads can inform you of any requirements.

Safety

With common sense and good judgment, you should be able to avoid mishaps on your hikes. Don’t push yourself or your companions beyond physical ability. Be aware of changing weather. Know basic first-aid techniques.

The following section elaborates on some of the potential hazards you may encounter on your hikes. Don’t let the list scare you. I’ve been hiking for more than twenty years without any serious mishap. The few incidents that have occurred usually were due to carelessness on my part, such as carrying inadequate water, not using sunscreen, or pushing beyond my limits.

Weather

More problems and emergencies in the outdoors are probably related to weather than any other factor. Even in the hot desert areas, sudden late-summer thunderstorms can drench you and, at the least, make you uncomfortably cool. In the West Texas mountains temperatures can plummet in storms. When combined with wet clothes or lack of shelter, a life-threatening situation can develop.

It’s easy to prepare for most weather problems. Always take extra warm clothes, especially on extended hikes. Wool and some synthetics retain some insulating capability when wet; cotton is worthless. Rain gear is essential, especially on hikes in the mountains in late summer and Central and East Texas in spring. Carry a reliable tent on longer hikes. Hole up and wait for bad weather to pass, rather than attempting a long hike out. Most storms in West Texas, especially in summer, are of short duration. The farther east you move in the state, the more likely that storms will be longer and wetter.

All Texas state parks require that permits be obtained for overnight camping. Colorado Bend State Park.

Hypothermia develops when the body’s temperature falls. Texas is generally a warm state, but sudden weather changes, especially in winter and in the mountains, can make hypothermia a risk. If conditions turn wet and cold and a member of your party begins to slur speech, shivers constantly, or becomes clumsy, sleepy, or unreasonable, immediately get the hiker into shelter and out of wet clothes. Give the victim warm liquids to drink and get him or her into a sleeping bag with one or more persons. Skin-to-skin contact conducts body heat to the victim most effectively. This isn’t a time for modesty; you may save the victim’s life.

At the other extreme, heat also can cause problems, particularly in summer in most of the state. On hot weather hikes, carry and drink adequate water. For long hikes in hot weather, plan to carry at least a gallon of water per person per day. Even hikes in the Chisos or Guadalupe Mountains will usually be quite hot in May and June before the summer rains begin. If you do summer hikes, especially on unshaded desert trails in West Texas, try to get an early start to avoid the worst of the heat. Don’t push as hard, take frequent breaks, and carry lots of water.

With heat exhaustion, the skin is still moist and sweaty but the victim may feel weak, dizzy, nauseated, or have muscle cramps. Find a cool shady place to rest and feed him plenty of liquids and a few crackers or other source of salt. After the victim feels better, keep him drinking plenty of liquids and limit physical activity. Hike out during a cooler time of day. The condition usually isn’t serious, but take the hiker to a doctor as soon as possible.

Heatstroke is less common, but this life-threatening condition can develop with prolonged exposure to very hot conditions. The body’s temperature regulation system stops functioning, resulting in a rapid rise in body temperature. The skin is hot, flushed, and bone dry. Confusion and unconsciousness can quickly follow.

Immediately get the victim into the coolest available place. Remove excess clothes and dampen skin and remaining clothes with water. Fan the victim for additional cooling. If a cool stream or pond is nearby, consider immersing the victim. You must get the body temperature down quickly. Seek medical help immediately.

Lightning poses another threat. When thunderstorms develop, seek lower ground. Stay off hilltops and away from lone trees, lakes, and open areas. Lightning makes exposed mountain peaks and ridges especially hazardous. Thunderstorms in the West Texas mountains most frequently develop during late-summer afternoons. Plan to start your hikes early to reach high peaks and ridges by lunchtime and head down promptly. The most severe storms usually strike Central and East Texas in spring. If you get caught in a lightning storm, seek shelter in a low-lying grove of small equal-size trees if possible. Put down your metal-framed packs, tripods, and metal tent poles, and move well away.

Heavy rains can also cause flooding. Stay out of narrow canyons boxed in by cliffs during heavy rains. Even though you may be in sunshine, watch the weather upstream from you. Camp well above and away from streams and rivers. No matter how tempting, never camp in that sandy site in the bottom of a dry desert wash. Storms upstream from you can send water sweeping down desert washes with unbelievable fury. In East Texas, broad low-lying floodplains flood regularly. Many of the Big Thicket trails are flooded at least once every spring.

A swamp in Davy Crockett National Forest’s Big Slough Wilderness, Hike 75.

Conditioning

Good physical condition will not only make your trip safer but also much more pleasant. Don’t push yourself too hard, especially at high altitudes. If you have been sedentary for a long time, consider getting a physical exam before hiking. Ease into hiking—start with the easy hikes and graduate to more difficult ones. Don’t push your party any harder or faster than the weakest member can handle comfortably. Know your limits. When you get tired, rest or turn back. Remember, you are out here to have fun.

Be mentally prepared. Read this guidebook and the specific hike description. Study maps and other books on the area. Every effort has been made to create a guidebook that is as accurate and current as possible, but a few errors may still creep in. Additionally, roads and trails change. Signs can disappear, springs can dry up, roads can wash out, and trails can be rerouted. Talk to park rangers about current road and trail conditions and water sources. Check the weather forecast. Determine the abilities and desires of your hiking companions before hitting the trail.

Altitude

Only a few mountain ranges in West Texas attain very high elevations. Since the highest peak reaches only 8,749 feet, most people will have few breathing problems on any of the hikes in Texas. At most, people coming from low elevations may have a little trouble in the higher reaches of the West Texas mountains. Until you acclimatize, you may experience a little shortness of breath and tire more easily. A very few hikers may develop headaches, nausea, fatigue, or other mild symptoms such as swelling of the face, hands, ankles, or other body areas at the highest altitudes. Mild symptoms shouldn’t change your plans. Rest for a day or two to acclimate. Retreating a thousand feet or so will often clear up any symptoms. Spending several days at moderate altitude before climbing high will often prevent problems.

Texas’s mountains are not high enough to cause the serious symptoms of altitude sickness, such as pulmonary edema (fluid collecting in the lungs) or cerebral edema (fluid accumulating in the brain), except in very rare cases. Should these symptoms develop, immediately get the victim to lower elevations and medical attention.

Companions

Pick your companions wisely. Consider their experience and physical and mental fitness. Try to form groups of relatively similar physical ability. Pick a leader, especially on long trips or with large groups. Ideally your group should include at least one experienced hiker.

Too large a group is unwieldy and diminishes the wilderness experience for yourself and others. An ideal size is probably four. In case of injury, one can stay with the victim while the other two hike out for help. No one is left alone. Leave your travel plans with friends so that they can send help if you do not return as planned. Allow plenty of time before help will be sent—hikes often run later than expected.

Never hike alone, especially cross-country or on little-traveled routes. That said, I must confess that I did most of the hikes in this guide alone. However, I religiously informed family or friends of my travel plans on a daily basis and did not deviate from them. Upon returning from a hike, I immediately called to let them know that I was back. Never forget to check in at the end of your hike. Nothing will aggravate rescuers more than to find that you were at the local watering hole relaxing with a beer while they were stumbling around in the rain and dark looking for you.

The only time that I did not worry about informing friends of my travel plans was when I did popular hikes on summer weekends. Plenty of other people were on the trail to offer aid if a mishap had occurred.

Water

Unfortunately, with the heavy use that many backcountry areas are receiving, all water sources may be contaminated and should be purified before use. Regardless of how clean and clear the source appears, always treat your water.

Boiling vigorously for ten minutes is a reliable method but slow and fuel consuming. Mechanical filtration units are available at most outdoors shops. Filters with a very small pore size strain out bacteria, viruses, cysts, and other microorganisms. Their ability to filter out the smallest organisms, such as viruses, varies from model to model.

For very contaminated water, filtration should probably be used in conjunction with chemical treatment. Chlorination is the method used by most municipal water systems, but the use of hyperiodide tablets is probably more controllable and reliable for backpackers. The tablets can be purchased at any outdoors store. Follow the directions carefully.

Cold or cloudy water requires more chemical use or longer treatment times. The cleaner your water is to begin with, the better. Get your water from springs or upstream from trails and camps if possible. For day hikes, it is usually easiest just to carry sufficient water for the day.

Stream Crossings

Crossing all but the smallest stream poses several hazards. Except in flood stage, few of the streams along the trails in this guide are big enough to present much risk of sweeping you away. However, do not underestimate the power of large bodies of moving water, such as the Rio Grande, Pedernales River, and Village Creek, or smaller streams in flood. Avoid crossing high-volume waterways when possible. If you must cross them, try to find rocks or logs to use, although they may be slippery. Or try to find a broad, slow-moving shallow stretch for your ford. Undo the waist strap on your backpack for quick removal if necessary, and use a stout walking stick for stability. Even use a rope if available.

Since the vast majority of the streams in this guide are too small to sweep you away, the biggest risk probably lies in jumping from rock to rock or crossing on logs to avoid wet feet. Rocks and logs are often unstable or slippery, making falls very possible. A heavy pack makes such crossings even more tricky. While such a fall might not be life threatening, a twisted ankle or broken leg would present serious problems. Use extra care and assist one another across streams.

The Rio Grande flows out of 1,500-foot-deep Santa Elena Canyon in Big Bend National Park.

Insects

Insects can make or break your trip in some areas at certain times of year. Late spring and summer are the most likely seasons for problems. Mosquitoes will hatch after heavy rains, even in desert regions, but in general mosquitoes and other insects become more of a problem the farther east you move across the state. A repellent containing a higher percentage of DEET will discourage mosquitoes and gnats from biting you.

To avoid large concentrations of mosquitoes, camp well away from streams, marshes, and other wet areas. Good mosquito netting on your tent will allow a pleasant night’s sleep. I have camped many times in West Texas in dry areas without a tent or netting with no problems at all. However, plan to use tents or netting almost year-round on the coastal islands and in southeastern Texas.

Ticks are common in Central and especially East Texas. They can carry serious diseases, such as Rocky Mountain spotted fever and Lyme disease, so be aware of them. Use insect repellent with a high percentage of DEET; wear clothing that fits snugly around the waist, ankles, and wrists; and check yourself and pets every night. If a tick attaches, remove it promptly. Use tweezers and avoid squeezing the tick as you pull it out. Do not leave the head embedded, and do not handle the tick. Apply antiseptic to the bite area and wash thoroughly. Ticks are probably most common in livestock areas. If you develop any signs of illness within two to three weeks of the bite, see a doctor.

Fire ants plague most of Central and East Texas year-round. Be sure to avoid their small, innocent-seeming mounds or you’ll discover the origin of their name.

One of the pleasures of hiking in West Texas is its paucity of nuisance insects.

Bears

Grizzlies have not roamed Texas for decades, so bear attacks are extremely unlikely. Except for a few lone black bears in the Guadalupe Mountains, bears had been virtually extinct in Texas since the 1930s. In the 1980s, however, a small number of black bears began to recolonize the Chisos Mountains at Big Bend. The bears migrated north from the Sierra del Carmen in Mexico, possibly because of a growing population there. The bears are scarce, so you are very unlikely to encounter one. If you do, consider yourself lucky. Very few Texans have ever seen a bear in the wild. Give any that you see a wide berth, especially those with cubs.

A few precautions will prevent any problems. In the Chisos Mountains—the most likely place to encounter a bear—store food and other smelly items, such as soap, toothpaste, and garbage, in the bear-proof boxes found at the primitive campsites. In other locations, put those items in a stuff sack and hang it from a tree well away from your tent. Hang it at least 10 feet above the ground and out from the trunk. Let the sack dangle a few feet below the limb to prevent access from above. Hanging your food will also discourage rodents and raccoons.

Leave your packs unzipped to prevent damage by a nosy animal. Never cook in your tent or keep food in your tent or sleeping bag. If a bear does take your food, don’t even think about trying to get it back.

The mountain lions in the Chisos Mountains have lost some of their fear of humans after years of no hunting, and there have been a tiny number of attacks over the years. On rare occasions hikers have encountered mountain lions on the trail. If you do see a lion, you are very fortunate. If they don’t immediately run away, stand your ground or retreat slowly. Don’t act like prey by running away or screaming. Check with park rangers for more advice on handling such an encounter.

Snakes

The vast majority of snakes you’ll come across on these trails (usually you will see none) are nonpoisonous. On rare occasions you may encounter a rattlesnake. Most are not aggressive and will not strike unless stepped on or otherwise provoked. In daytime or cold weather, they are usually holed up under rocks and in cracks. The most likely time to see them is on summer evenings in Central and West Texas. If you watch your step, don’t hike at night, and don’t put your hands or feet under rocks, ledges, and other places that you can’t see, you should never have a problem. Don’t hurt or kill any snakes that you find. Remember, they are important predators.

Texas also has water moccasins, copperheads, and coral snakes, particularly the farther east you move across the state. All will be seen only on rare occasions. Similar to rattlesnakes, they are not usually aggressive and will seek to avoid conflicts.

If bitten by a venomous snake, get medical help as soon as possible. Treatment methods are beyond the scope of this book. Fortunately, the majority of bites do not inject a significant amount of venom. For basic treatment, tie a shoelace or other cord around the affected extremity between the bite and the rest of the body. Tie it only tight enough to dent the skin; don’t cut off blood circulation. Apply ice if available. Get to a doctor as soon as possible. Do not use a snakebite kit without proper instruction and then only in case of extreme emergency.

Blacktail rattlesnake at Government Canyon State Natural Area.

Equipment

The most important outdoor equipment is probably your footwear. Hiking boots should be sturdy and comfortable. Lightweight boots are probably adequate for all but rugged trails and routes and for carrying heavy packs. Proper clothing, plenty of food and water, and a pack are other necessities.

Other vital items for every trip include waterproof matches, rain gear or some sort of emergency shelter, a pocketknife, a signal mirror and whistle, a first-aid kit, a detailed map, and a compass. Many of the hikes in this guide are in areas with cell phone service, but don’t count on it.

In general, all your outdoor equipment should be as light and small as possible. Many excellent books and outdoor shops will help you select the proper boots, tents, sleeping bags, cooking utensils, and other equipment necessary for your hikes.

If You Get Lost

Careful use of the maps and hike descriptions in this guide should keep you from getting lost. However, if you should become lost or disoriented, stop immediately. Charging around blindly will only worsen the problem. Careful study of the map, your compass, and surrounding landmarks will often reorient you. If you can retrace your route, follow it until you are oriented again. Don’t proceed unless you are sure of your location.

If you are truly lost, rescuers should soon be looking for you if you left travel plans with friends or family. In an emergency, follow a drainage downstream. In most areas, it will eventually lead you to a trail, road, or town. Remember, however, that it also will probably take you farther away from rescuers. In a few of the largest wild areas, in particular the Guadalupe Mountains and Big Bend, following a drainage may take you deeper into the backcountry rather than leading you out.

Use of signals may help rescuers find you. A series of three flashes or noises is the universal distress signal. Use a whistle or signal mirror. Provided that it can be done safely, a small smoky fire may help rescuers find you.

Because of good trails and open country, people are unlikely to get lost on most of the hikes in this guide. Be careful, however, if you leave the trail in the dense woods and flat terrain of East Texas. It’s very easy to become disoriented. However, the wild areas of East Texas are generally quite small. Following a drainage will usually bring you to a road, residence, or town fairly quickly.

Hunting

Hunting is usually allowed in the national forests generally during the various seasons set up by state agencies. Fall in particular can bring out large numbers of deer hunters. The seasons vary from year to year and in different parts of the state. Check with local ranger stations before your hike to determine what, if any, hunting seasons might be in effect.

If you hike during a hunting season, inquire locally to find areas that are less popular with hunters, and be sure to wear bright-colored clothing. Most Texas state parks and National Park Service areas do not allow hunting.

Hiking with Children

Don’t be afraid to take your children with you the next time you take a hiking trip. Kids of almost any age will enjoy hiking if they aren’t pushed beyond their ability. Babies and small toddlers can be carried in specially designed backpacks. As children get older and too large to carry, plan easy hikes that fit within their physical limits. If children are pushed too hard, not only will they (and you) be miserable but they also may develop a long-term aversion to hiking and the outdoors.

Be sure to bring plenty of snacks for your children and take lots of rest breaks. Carry adequate clothing for any possible weather extreme. Children are much smaller than adults and will get chilled and possibly hypothermic much more quickly than adults if the weather suddenly turns wet or cold. Don’t forget to carry insect repellent, especially on hikes in the central and eastern parts of the state. You may be tough enough to handle a few mosquitoes or fire ants, but they will quickly make your kids miserable.

Most children are curious and will get excited when taken to a new place. However, in their excitement, they may run off in all directions. To avoid getting separated, be sure to watch your kids at all times. Young children, in particular, do not appreciate the dangers posed by cliffs, fast-flowing rivers, poison ivy, and other hazards.

Teach your children ahead of time what to do in case they do get separated from you. Instruct them to stay in one place until they are found. If they always carry a whistle, they may be able to lead you right to them. Also show them how to avoid snakes and identify poison ivy.

Plan shorter hikes than you would normally take without children. Pick hikes that have extras that will interest kids. Many of the hikes in this guide follow permanent streams. Water always seems to attract children; before you know it your kids will be wading, skipping rocks, or building dams. Sand dunes and caves will also appeal, but be sure to supervise closely.

The following hikes should entice children. A few may be difficult if hiked in their entirety, but most are easy and all are interesting even if only hiked a short distance.

You can’t lose taking children of any age to Monahans Sandhills (Hike 28). Of course you may spend the next two days getting the sand out of everything.

The rocks and boulders at Hueco Tanks (Hike 25) will entertain children for hours. Likewise, the granite domes of Enchanted Rock (Hike 33) will have great appeal. Watch carefully, though. There are very high cliffs at both parks, and the many boulders and crevices make it easy for kids to slip out of sight.

Both the short, easy Sundew Trail (Hike 83) and the longer Kirby Trail (Hike 84) in the Big Thicket are nature trails that will teach your children about the natural environment.

Some good hikes along streams include the Sawmill Trail in East Texas (Hike 79), Lost Maples in the Hill Country (Hike 38), and the Window (Hike 3) at Big Bend National Park. Remember, on the Window hike the trail is uphill all the way back to the trailhead. Make sure your kids are strong enough to hike back without becoming exhausted.

Smith Spring (Hike 20) is an easy hike to a shady oasis in the Guadalupe Mountains. The spring is very delicate, though, so you will need to keep children out of the water on this hike. Palmetto (Hike 51) is a very easy hike in Central Texas.

Hamilton Pool (Hike 44) is a sure winner. The high point of this easy Hill Country hike is the large, natural swimming hole partially roofed by a cave. Pedernales Falls (Hike 36) has a good wading and swimming area only a short distance into the hike. The beaches of Padre Island (Hike 55) and Matagorda Island (Hike 53) will be popular. Watch your children closely when they are in or near the water. Don’t let them dive in these natural swimming areas of uncertain depth.