Chapter 8

Biological Inheritance

Genes and fields

Living organisms inherit genes from their ancestors. According to the hypothesis of formative causation, they also inherit morphic fields. Heredity depends both on genes and on morphic resonance.

The conventional theory attempts to squeeze all the hereditary characteristics of organisms into their genes. Development is then understood as the expression of these genes through the synthesis of proteins and other molecules. The words hereditary and genetic are usually treated as synonyms, and inherited characteristics, such as the ability of an acorn to grow into an oak tree or of a wren to build a nest, are usually referred to as genetic, or as genetically programmed.

Certainly DNA is inherited genetically. Some DNA codes for the sequence of amino acids in proteins; some codes for RNA such as that found in ribosomes; and some is involved in the control of gene expression. However, in higher organisms only a small percentage of the DNA (in humans, about 1 per cent) seems to be involved in such coding and genetic control. The function, if any, of the vast majority is unknown, although some probably plays an important structural role in the chromosomes. Moreover, the total genetic inheritance seems to bear very little relationship to the complexity of the organism. One of the big surprises of the human genome project was that we have only about 20,000–25,000 genes, far few than the 100,000 expected. Sea urchins have more genes than we do, about 26,000, and many species of plants have more still – rice has about 38,000 and the cells of lilies contain about 30 times more DNA than human cells.1 Among amphibians, some species have 100 times more DNA than others.

There is also a poor correlation between the genetic differences between species and the form and behaviour of these species. Thus, for example, human beings and chimpanzees have genes that code for almost identical proteins: ‘The average human polypeptide is more than 99 per cent identical to its chimpanzee counterpart.’2 Direct comparisons of the DNA sequences believed to be of genetic significance show that the overall difference between the two species is only 1.1 per cent. Soon before the entire chimpanzee genome was published in 2005, Svante Paabo, the Director of the Chimpanzee Genome Project commented that, ‘We cannot see in this why we are so different from chimpanzees.’3 By contrast, comparisons of species that are very similar to each other, such as different kinds of fruit flies in the genus Drosophila, often reveal considerably greater genetic differences than those between humans and chimpanzees.4

From the point of view of the hypothesis of formative causation, DNA, or rather a small part of it, is responsible for coding for RNA and the sequences of amino acids in proteins, and these have an essential role in the functioning and development of the organism. But the forms of the cells, tissues, organs, and the organisms as a whole are shaped not by DNA but by morphic fields. The inherited behaviour of animals is likewise organized by morphic fields. Genetic changes can affect both form and behaviour, but these patterns of activity are inherited by morphic resonance.

Consider the analogy of a television set, tuned to a particular channel. The pictures on the screen arise in the TV studio and are transmitted through the electromagnetic field as vibrations of a particular frequency. To produce the pictures on the screen, the set must contain the right components wired in the right way, and also requires a supply of electrical energy. Changes in the components, such as a fault in a transistor, can alter or even abolish the pictures on the screen. But this does not prove that the pictures arise from the components or the interactions between them, nor that they are programmed within the set. Likewise, the fact that genetic mutations can affect the form and behaviour of organisms does not prove that form and behaviour are coded in genes or programmed genetically. The form and behaviour of organisms do not arise simply from mechanistic interactions within the organism, or even between the organism and its immediate environment; they depend on the fields to which the organism is tuned.

To pursue this analogy, developing organisms are tuned to similar past organisms, which act as morphic ‘transmitters.’ Their tuning depends on the presence of appropriate genes and proteins, and genetic inheritance helps to explain why they are tuned in to morphic fields of their own species: a frog’s egg tunes in to frog fields rather than newt or goldfish fields because it is already a frog cell containing frog genes and proteins.

Genetic mutations affect morphogenesis in two main ways. First, they can lead to distortions or alterations in a normal morphogenetic process, just as ‘mutant’ components in a TV set can lead to distortions or alterations in the form or colour of the pictures. Second, they can result in the suppression of entire morphogenetic processes or in their replacement by different ones. These are analogous to ‘mutations’ in the tuning circuit of the television: the original transmission is no longer picked up; either the screen goes blank, or the set picks up a different channel.

Mutations

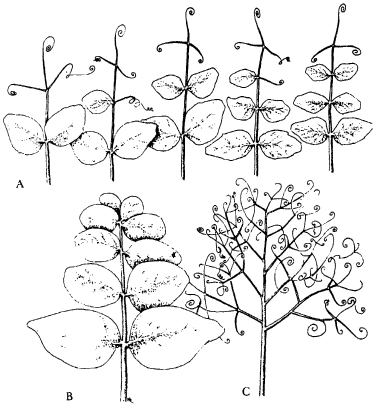

Many mutations affect normal processes of development, often in quite small ways, and normal pathways of morphogenesis are conventionally considered to be under the control of large numbers of ‘minor genes’ and ‘modifying genes.’ But in certain spectacular mutations entire structures are lost or are replaced by other structures. These are called homeotic mutants. In pea plants, for instance, the leaves normally have leaflets near the base and tendrils at the tips (Fig. 8.1). One mutation, in a single gene, results in the replacement of all the leaflets by tendrils; another, in a different gene, has the opposite effect: all the tendrils are replaced by leaflets. Somehow these genetic mutations affect the tuning of the primordia in the embryonic leaf so that they all develop under the influence of leaflet fields or tendril fields.5 A similar metaphor is already implicit in the conventional interpretation of such genes as ‘switching on’ or ‘switching off’ entire pathways of development.

Figure 8.1 A: Normal pea leaves, bearing both leaflets and tendrils. B: Leaf of a mutant pea in which only leaflets are formed. C: Leaf of a mutant pea in which only tendrils are formed.

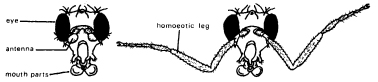

Many homeotic mutations have been identified in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster. For example, in antennapedia mutants, the antennae are replaced by legs (Fig. 8.2). These legs are of the type normally found in the second of the three pairs. Another mutation has the opposite effect: the second pair of legs is replaced by antennae.6 In bithorax mutants, the third thoracic segment, which normally bears halteres (small balancing organs), is partially or completely transformed into a duplicate of the second thoracic segment, which bears wings. The resulting flies have four wings instead of two (Fig. 5.6).

Figure 8.2 On the left, the head of a normal fruit-fly; on the right, the head of a mutant fly in which the antennae are transformed into legs as a result of a mutation within the antennapedia gene complex.

There are several kinds of bithorax mutations.7 These occur in nearby genes on the same chromosome, and their effects have been studied in great detail.8 Some of these genes have been isolated and cloned by the techniques of genetic engineering, and the sequences of bases in their DNA have been analysed.9 By means of sophisticated techniques involving antibodies stained with fluorescent dyes, the proteins that some of these genes code for have been localized in the early embryos; and it is now possible to see which of these proteins are produced in which segments, enabling the differing distribution of these proteins in normal flies and homeotic mutants to be compared.10 The products of homeotic genes clearly play an important role in determining which pathways of development the primordia in the embryonic segments will follow.

From the point of view of formative causation, the proteins coded for by these genes affect the tuning of the primordia, causing them to come under the influence of one field rather than another. Mutations in these genes alter the tuning of the primordia, just as ‘mutations’ of components in the tuning circuit of a television can result in changes of channel. Sometimes the alteration is not complete, and a germ structure may be finely balanced between entering into morphic resonance with alternative fields. Homeotic mutations often show variable penetrance, which is to say that not all the flies with the mutant genes have a mutant form; and they also show variable expressivity, which means that the mutant form may be expressed only partially: for example, antennapedia mutants sometimes have a normal antenna on one side of their head and a leg in place of an antenna on the other.

In the 1980s, a family of genes called homeobox genes was discovered in fruit flies. Homeobox genes have homeotic effects on the pattern in which different parts of the body develop. Mutations in these genes can lead to the growth of extra, non-functional body parts.11 At first sight, they appeared to provide the basis for a molecular explanation of morphogenesis: here were the key switches. At the molecular level, homeobox genes act as templates for proteins that ‘switch on’ cascades of other genes.

Research on other species soon revealed that these molecular control systems are very similar in widely different animals. Homeobox genes are almost identical in flies, reptiles, mice and humans. Although they play a role in the determination of the body plan, they cannot themselves explain the shape of the organisms. Since the genes are so similar in fruit flies and in us, they cannot explain the differences between flies and humans.

It was shocking to find that the diversity of body plans across many different animal groups was not reflected in diversity at the level of the genes. As two leading developmental molecular biologists commented, ‘Where we most expect to find variation, we find conservation, a lack of change.’12

This study of genes involved in the regulation of development is part of a growing field called evolutionary developmental biology, or evo-devo for short. Once again, research in molecular biology has shown that morphogenesis, the coming into being of specific forms, continues to elude a molecular explanation, but seems to depend on fields.

If homeotic mutations bring about their effects by altering the normal patterns of vibratory activity in morphogenetic germs, then other factors that alter these patterns could have similar effects. Again, think of the television analogy. A change in tuning from one channel to another can occur because of a mutation in the tuning circuit; but it can also happen in response to a stimulus from the environment, such as a mechanical jolt to the tuning knob. The causes of the change in tuning are different, but their effect is the same.

It has been known for many years that the normal development of organisms can be disturbed by exposing embryos to toxic chemicals, X rays, heat, and various non-specific stimuli. The interesting thing is that many of the abnormalities that result from such treatments fall into definite categories that are the same as abnormalities due to genetic mutations. The resulting organisms are called phenocopies. In the case of Drosophila, practically all forms of homeotic mutant can also appear in genetically normal flies as phenocopies.13 The mutant structures arise as a result of disturbances to the normal course of development, and these disturbances may be due either to genes or to influences from the environment; according to the hypothesis of formative causation they are a consequence of changes in the tuning of the germ structures within the embryo such that they become associated with different morphic fields – a leg field instead of an antenna field, for instance.

The difference between this hypothesis and the conventional genetic interpretation becomes clearer when we consider the inheritance of acquired characteristics.

The ‘Lamarckian’ inheritance of acquired characteristics

If plants of a particular species are grown under unusual conditions, for example at a high altitude, they generally develop unusually. The modified form they take up is an ‘acquired characteristic’ which has come about in response to the environment. Likewise, if rats learn a new trick, this is an acquired behavioural characteristic, as opposed to an inherited instinct.

Until the late nineteenth century, it was almost universally believed that acquired characteristics could be inherited.14 The zoologist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1744–1829) took this for granted, as did Charles Darwin.15 In this respect, Charles Darwin was a convinced Lamarckian. He believed that habits acquired by individual animals could be inherited, and played an important part in evolution: ‘We need not … doubt that under nature new races and new species would become adapted to widely different climates, by variation, aided by habit, and regulated by natural selection.’16 Darwin provided many examples of the inheritance of acquired characters in his book The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication, and also proposed a theory to explain it, the theory of ‘pangenesis’.

The idea of Lamarckian inheritance has the great advantage of making sense of many of the evolutionary adaptations of organisms. For example, camels, like many other animals, develop thick calluses on their skin as a result of abrasion. They possess such calluses on their knees just where the skin is subject to abrasion as they kneel down. Baby camels are born with thick pads on their knees at exactly the right places.

From a Lamarckian point of view, such calluses were acquired by ancestral camels as a result of their habit of kneeling, and then over many generations this acquired characteristic became increasingly hereditary, developing even in embryos before they have ever had a chance to kneel. This idea is straightforward enough, and has a strong ‘common sense’ appeal. However, it was denied dogmatically by neo-Darwinians, who, unlike Darwin, rejected the possibility of such inheritance. From a neo-Darwinian point of view, camels are born with pads on their knees not because their ancestors acquired them as a result of their habits, but because they arose as a result of chance genetic mutations that just happened to produce pads in the right places. The mutant genes ‘for’ knee pads were favoured by natural selection because they gave an advantage to camels born with pads on their knees.

I return to a discussion of the evolutionary significance of the inheritance of acquired characteristics in Chapter 16; I now consider the orthodox denial of this possibility and the light that is shed upon it by the hypothesis of formative causation and by the recent recognition of epigenetic inheritance.

The genetic theory of inheritance is rooted in the Weismannian assumption that the germ-plasm (genotype) determines the somatoplasm (phenotype), but not vice versa (see above). It therefore rules out from first principles the possibility that there can be an inheritance of acquired characteristics.

Precisely because such a fundamental theoretical principle is at stake, this subject has been the focus of some of the bitterest controversies in the history of biology. In the West, Lamarckian inheritance was treated as a heresy after the 1920s; but in the Soviet Union, from the 1930s to the 1960s the situation was the other way round. Under the leadership of Trofim Lysenko the inheritance of acquired characteristics became the orthodox doctrine; Mendelian geneticists were persecuted, and some were liquidated.17 This political polarization made an objective examination of the evidence almost impossible.

From a Weismannian perspective, the theoretical reasons for rejecting the inheritance of acquired characteristics were strengthened by the discoveries of molecular biology. It was practically impossible to conceive of a mechanism whereby a learned pattern of behaviour in a rat, say, could cause specific modifications to the genes within the germ cells, such that the rat’s progeny would be ‘programmed’ to learn the same behaviour more easily.

Nevertheless, in spite of Weismannian theories, there is a large body of evidence that indicates that acquired characteristics can be inherited. Some of these experimental results were dismissed as fraudulent, and this may well be the case with some of Lysenko’s data. There was also evidence of fraud in a famous Lamarckian experiment carried out by Paul Kammerer, a story well told by Arthur Koestler in The Case of the Midwife Toad. However, numerous other experiments carried out by dozens of biologists in the West before the 1930s18 and by many Soviet biologists in the Lysenko period19 provided evidence for an inheritance of acquired characters. These experimental findings are usually dismissed or simply ignored by geneticists and by neo-Darwinians. However, there is now good evidence that an inheritance of acquired characteristics does in fact take place.

Epigenetic inheritance

Around the turn of the millennium, the taboo against the inheritance of acquired characteristics began to lose its power with a growing recognition of a new form of inheritance, called epigenetic inheritance. The prefix ‘epi’ means ‘over and above’. Epigenetic inheritance does not involve changes in the genes themselves, but rather changes in gene expression. Characteristics acquired by parents can indeed be passed on to their offspring. For example, water fleas of the genus Daphnia develop large protective spines when predators are around; their offspring also have these spines, even when not exposed to predators.20

Several molecular mechanisms of epigenetic inheritance have been identified. Changes in the configuration of the chromatin – the DNA-protein complex that makes up the structure of chromosomes – can be passed on from cell to daughter cell. Some such changes can also be passed on through eggs and sperm, and thus become hereditary. Another kind of epigenetic change, sometimes called genomic imprinting, involves the methylation of DNA molecules. There is a heritable chemical change in the DNA itself, but the underlying genes remain the same.

Epigenetic inheritance also occurs in humans. Even the effects of famines and diseases can echo down the generations. The Human Epigenome Project was launched in 2003, and is helping to coordinate research in this rapidly growing field of enquiry.21

Morphic resonance provides another means by which the inheritance of acquired characteristics can occur. Its effects can be distinguished experimentally from other forms of epigenetic inheritance, as discussed below.

The inheritance of acquired characteristics in fruit flies

In the 1950s a fascinating series of experiments was carried out with fruit flies in Waddington’s laboratory at Edinburgh University. Developing flies were subjected to abnormal stimuli, and consequently some developed abnormally: they were phenocopies. In one experiment, young pupae, in which the larvae were metamorphosing into flies, were heated to 40°C for four hours. Some of the emerging flies had abnormal wings lacking cross-veins. In another experiment, eggs were exposed to fumes of ether for 25 minutes about three hours after they were laid. Some of the resulting flies were phenocopies of the bithorax type (Fig. 5.6). The abnormal flies were selected as parents of the next generation, and the eggs were again subjected to the abnormal stimulus, and so on. A higher and higher proportion of flies was abnormal in successive generations. After a number of generations, sometimes as few as eight, these flies gave rise to progeny that showed the abnormal character even in the absence of the abnormal stimulus.22 Matings between cross-veinless flies obtained in this way gave rise to strains that regularly produced cross-veinless flies when cultured at normal temperatures.23 Similarly, bithorax-type flies appeared generation after generation without the ether treatment.

Waddington called this phenomenon genetic assimilation, which he defined as a ‘process by which characters which were originally ‘acquired characters’, in the conventional sense, may become converted, by a process of selection acting for several or many generations on the population concerned, into ‘inherited characters’.24 He explained ‘genetic assimilation’ in terms of the selection of genes that gave the flies a capacity to respond to the environmental stress, which then went on producing the same abnormal pattern of development even in the absence of the stress. This seemed at first glance to provide a neo-Darwinian interpretation of the inheritance of acquired characters, and the concept of genetic assimilation is now used in conventional evolutionary theory to account for otherwise puzzling examples of apparent Lamarckian inheritance, such as the pads on camels’ knees.

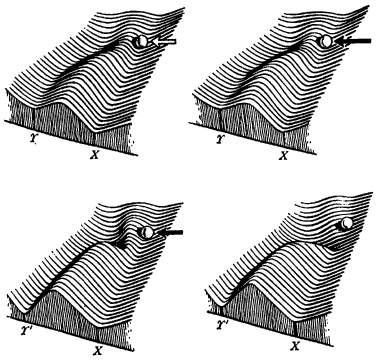

But genetic assimilation does not depend on genes alone. Waddington’s explanation of the continued appearance of abnormal flies in the ‘assimilated’ strains in the absence of the environmental stimulus involved his idea of canalized pathways of development, or chreodes (Fig. 8.3). He attributed to these an autonomy that remained unexplained: ‘Developmental processes have some structural stability, so that once you have got a developmental process going in a certain direction it tends to go on there independently of changes in the environment.’25

Figure 8.3 Waddington’s explanation of ‘genetic assimilation’ in terms of chreodes. The upper left drawing represents the original stock of fruit-flies; normal development follows the chreode leading to the normal adult form, X. A developmental modification, Y, for example the formation of four-winged flies, involves following a different chreode. The developing system can be forced to cross a threshold or col into the Y chreode by an environmental stress, represented by the white arrow (upper left). A genetic mutation can have a similar effect, represented by the black arrow (upper right). The two lower diagrams represent alternative models of genetic assimilation. In the one on the left, in Waddington’s words, ‘the threshold protecting the wild type is lowered to some extent, but there is an identifiable major gene which helps push the developing tissues into the Y path. On the right, the genotype as a whole causes the threshold to disappear and there is no identifiable “switch gene”. Note that in both the genetic assimilation diagrams there has been a “tuning” of the acquired character, i.e. the Y valley is deepened and its end-point shifted from Y to Y′.’ (From The Strategy of Genes by C. H. Waddington; George Allen and Unwin, Ltd., 1957. Reproduced by permission.)

This is just the kind of effect that would be expected on the basis of morphic resonance. The larger the number of abnormal flies that appeared in the population, the more would the abnormal chreodes be stabilized by morphic resonance and the greater would be the probability of the abnormal development. The interpretation does not deny the role of genetic selection in Waddington’s experiments, but it suggests that an increasing proportion of flies would show the abnormal character in successive generations even in the absence of selection of abnormal flies as the parents of the next generation.

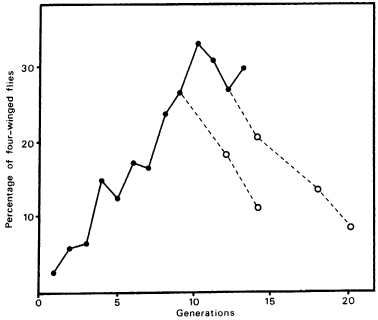

And this is what happens. Waddington’s experiments did not include a control line in which unselected flies were allowed to mate at random in each generation. Mae-wan Ho and her colleagues at the Open University in England repeated Waddington’s experiment in the 1980s, treating the eggs of successive generations with ether. But, unlike Waddington, they allowed all the flies to mate at random; they did not pick out the abnormal flies in each generation to serve as the parents of the next. In fact, in their experiments the abnormal flies were at a disadvantage in mating, and natural selection worked against them. Nevertheless, they found that the proportion of bithorax-type flies increased progressively from 2 per cent in the first generation to over 30 per cent in the tenth (Fig. 8.4).26 In other words, in each generation most of the parent flies were normal in appearance, and yet more and more abnormal flies were produced in successive generations.27

Figure 8.4 The effects of exposing successive generations of fruit-fly eggs to ether on the percentage of bithorax-type flies in the population. The dotted lines show what happened when the ether treatment was discontinued in a subpopulation of the flies; the percentage of abnormal flies declined in successive generations. (After Ho, et al., 1983)

Anticipating the objection that there must have been some subtle genetic selection going on in favour of abnormal development, Ho and her colleagues did a parallel experiment with an inbred strain of flies. There was very little genetic variability in this strain, hence little scope for selection. But here too the proportion of bithorax-type flies increased progressively.

When flies from these populations were returned to normal conditions, without ether treatment, they continued to give rise to a considerable proportion of abnormal progeny. This proportion gradually declined over several generations (Fig. 8.4).

Ether would not be expected to have any specific effects on the genes, and certainly not to cause specific mutations leading to the appearance of four-winged flies. Nor do the results obtained by Ho and her colleagues suggest that such genetic changes occurred. By crossing control flies with flies from ether-treated populations, they found that the marked tendency of ether-treated flies to give rise to abnormal progeny was inherited through the mothers, not the fathers. Waddington himself found a similar maternal effect in one of his experiments.28 They interpret this to mean that the ether treatment somehow changed the cytoplasm (the organized cell structures outside the nucleus) rather than the genes. Cytoplasm is inherited only from mothers, whereas genes are inherited from both parents. Somehow the ether-induced modifications of the cytoplasm persisted for several generations after ether treatment had ceased. Nothing of this kind would be expected on the basis of conventional genetic theory.

If the ether treatment in fact modified the cytoplasm in some way, then the developing flies would be specifically tuned to past flies with similarly modified cytoplasm, and this specificity would enhance morphic resonance from abnormal predecessors. As the experiment proceeded, there would be a cumulative influence from the increasing numbers of abnormal flies, increasing the probability of the pathway of development following the abnormal chreode (Fig. 8.3).

Neither Waddington nor Ho considered the possibility of epigenetic inheritance through modification of the DNA, because this phenomenon had not been discovered when they did their research. Perhaps epigenetic inheritance played a part in some of their experiments, but it leads to different predictions from morphic resonance.29

If the chreode leading to the four-winged form became more probable as the experiment proceeded, then we might expect that even normal flies of the same strain, whose parents had not been exposed to ether, would show an increasing tendency to produce four-winged progeny in response to ether treatment. This would not be expected on the basis of epigenetic inheritance. The data of Ho’s group suggested that this was indeed the case. After the experimental flies had been treated with ether for six generations, they examined the effect of the same treatment on control flies. In the first generation 10 per cent of the progeny were abnormal, and in the second generation 20 per cent.30 This compares with 2.5 and 6 per cent in the first and second generations of the experimental line (Fig. 8.4). Thus, after many of the flies had already responded to ether by developing abnormally, there was a much greater tendency for new batches of flies to do so. This is just what would be expected from the point of view of the hypothesis of formative causation.

In further experiments, it should be possible to confirm whether or not acquired characteristics have an increased probability of appearing in genetically similar organisms whose parents have not been exposed to this stimulus. The abnormal organisms should show an increased probability of appearing not only in the same laboratory, but in laboratories hundreds of miles away. This would provide a good way of testing the hypothesis of formative causation. If the development of abnormal organisms in one place caused a higher proportion of organisms to develop the same abnormality elsewhere in response to the same stimulus, this result would be inexplicable from the point of view of both genetics and epigenetics.

For decades, the debate about Lamarckian inheritance has centred not so much on empirical evidence for or against such inheritance as on the question of whether or not such inheritance is theoretically possible. According to the genetic theory of inheritance, it is impossible because the genes cannot be specifically modified as a result of characteristics that organisms acquire in response to their environment or through the development of new habits of behaviour. Lamarckians assumed that genetic modifications must take place, but were unable to suggest how. Epigenetic inheritance through modification of the DNA or chromatin provides a new way in which the inheritance of acquired characteristics can happen.

The hypothesis of formative causation provides another: acquired characteristics can be inherited by morphic resonance. This inheritance can take place without any transfer of genes at all. For example, as we have just seen, fruit flies may inherit a tendency to develop abnormally in response to ether from fruit flies of the same strain without inheriting any modified genes from them, and indeed without any physical contact.

Dominant and recessive morphic fields

We shall now consider the implications of the hypothesis of formative causation for the understanding of genetic dominance.

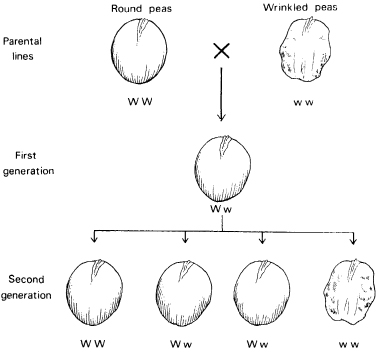

The great majority of mutations are recessive. That is to say, if a mutant organism is crossed with a normal one, the ‘wild type’, the progeny are normal. The normal type is dominant. Some of the second generation, produced by crossing the hybrids with each other, show the mutant character, but again the majority are normal.

The study of this kind of phenomenon by Mendel laid the foundation for the science of genetics. In one of his classic experiments, he crossed normal pea plants with a variety that produced wrinkled seeds. The first generation had normal seeds. In the second generation about three-quarters of the progeny had normal seeds and about a quarter wrinkled seeds. This is called Mendelian segregation and is explained in terms of Mendelian determinants, or genes (Fig. 8.5). The normal plants have two copies of the normal gene. The abnormal plants have two copies of a mutant form of the gene, resulting in wrinkled seeds. Each parent contributes one copy of each of its genes to the progeny. Consequently the hybrid peas have one normal-seed allele and one wrinkled-seed allele. Normal seeds are produced because the normal-seed gene is dominant and the wrinkled-seed gene is recessive. In the second generation, through the random combination of genes from the egg and pollen cells, on average one plant will have two round pea alleles, and one will have two wrinkled pea alleles, and two will have one copy of each allele. The latter will have round seeds, as of course will the plants with round pea alleles; thus there will be an approximate ratio of three normal-seeded plants to one wrinkled-seeded plant.

Figure 8.5 A standard example of Mendelian inheritance in peas. The gene W is dominant and leads to the development of round seeds. An alternative form of this gene, w, is recessive and leads to the production of wrinkled seeds when the W gene is absent. Only one copy of the gene is present in the egg and pollen cells; hence half the egg and pollen cells of the first-generation hybrids carry the W gene and half the w gene, resulting in an approximate ratio of one WW plant to two Ww plants to one ww plant in the second generation. Since W is dominant, this means there are approximately three times as many plants with round seeds as with wrinkled seeds.

This is elementary genetics, and is well known to every student of the subject. But the very familiarity of these concepts conceals a deep problem. Why are normal wild-type genes almost always dominant? The problem becomes apparent when we consider it in an evolutionary context. New features of organisms arise by mutation. But the great majority of mutations are recessive. If these mutants are favoured by natural selection, the mutant type becomes more common, and eventually becomes predominant; what were originally mutants become the normal or wild type. As this happens, the genes that were originally recessive become dominant. So dominance cannot be an intrinsic property of genes, because dominance itself evolves.

The evolution of dominance is usually explained in terms of the natural selection of more dominant versions of the mutant genes, and also in terms of the selection of large numbers of minor genes that provide a ‘genetic background’ favouring the dominance of the favourable mutant. Here is a typical textbook account:

If certain phenotypic properties are favoured, then, clearly, the determinant or determinants conferring them will also be favoured. What is more, it will then be a further advantage if the elements in question find expression in all the individuals carrying them. In other words, dominance will be favoured from the point of view of adaptation. This means that certain alleles will be preferred to their less dominant isoalleles, and, other things being equal, it also means that background genotypes facilitating expression will be favoured over those which do not.31

This theory is speculative and untestable, because the ‘background genotype’ is too complex to be analysed genetically.

The hypothesis of formative causation provides an alternative explanation. The types most common in the past – the normal, wild types – stabilize the wild-type fields by morphic resonance. Mutant organisms, which are much rarer, are stabilized by much weaker fields simply because there have been so few of them. In hybrids, genes and proteins from both parental types are present, and the hybrids enter into morphic resonance with both the normal and the mutant types. The normal fields are stronger because far more past organisms contribute to them, and they consequently ‘swamp’ the mutant fields. A normal pattern of development will be far more probable: in other words it will be dominant. This is a dominance of fields, not a dominance of genes.

If a mutant type is favoured by natural selection, it becomes more and more common. Consequently, increasing numbers of organisms contribute by morphic resonance to the stabilization of these fields, and the mutant pattern of development becomes increasingly probable. From a genetic point of view, this increasing dominance of the mutant morphic fields would be interpreted as an increasing dominance of the mutant genes. Such changes in dominance as a result of morphic resonance from increasing numbers of mutant organisms could be investigated experimentally; some possible experimental designs are outlined in A New Science of Life.32

If two species are crossed, the hybrids will enter into morphic resonance with the fields of both. If both species are stabilized by morphic resonance from comparable numbers of past individuals, the fields will be of similar strength; neither will be dominant, and both will influence the developing hybrid to a similar extent. The hybrids will therefore exhibit features of both parental species, and be intermediate between them. This is generally the case: think, for example, of mules, hybrids between horses and donkeys.

The morphic fields of instinctive behaviour

According to the hypothesis of formative causation, not only is the form of organisms shaped by fields, but so is their behaviour. Behavioural fields, like morphogenetic fields, are organized in nested hierarchies. They co-ordinate the movements of animals through imposing rhythmic patterns of order on the probabilistic activities of the nervous system.33 Behavioural fields are of the same general nature as morphogenetic fields: they are another kind of morphic field and like morphogenetic fields are stabilized by morphic resonance.

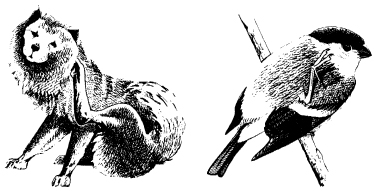

In all animals certain patterns of motor activity are innate: for example the way in which mammals and birds scratch themselves (Fig. 8.6). So are instincts. For instance, young spiders hatch from their eggs with an inborn capacity to spin webs characteristic of their species; they set to work and spin them even if they are raised in isolation and have never seen another spider or a web. But even when animals learn new patterns of activity, they do so within an inherited framework of potentialities, and there is no sharp dividing line between instincts and learned behaviour, which depends on inherited capacities. For example, human babies do not have an innate ability to speak particular languages; they have to learn. But the capacity to learn human language is inherited, and this capacity is absent from other species.

Figure 8.6 The scratching behaviour of a dog and a European bullfinch. The inborn habit of scratching with a hind limb crossed over a forelimb is common to most reptiles, birds, and mammals. (After Lorenz, ‘The Evolution of Behavior’, Scientific American, Dec. 1958)

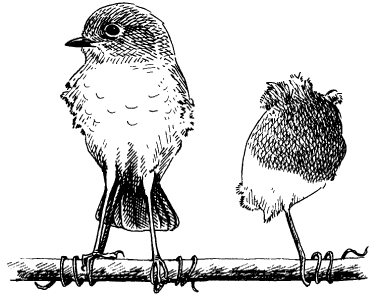

The study of instinctive behaviour by ethologists has led to three major conclusions, often referred to as the classic concepts of ethology. First, instincts are organized in a hierarchy of systems, which are superimposed upon one another. Each level is activated primarily by a system at the level above it. Second, the behaviour that occurs under the influence of the major instincts often consists of chains of more or less stereotyped patterns of behaviour called fixed action patterns. Third, each pattern of behaviour requires a specific stimulus in order to be activated. The stimulus, or releaser, may come from within the body, or from the environment, in which case it is called a sign stimulus. For example, during the breeding season, territory-holding male European robins threaten other males that come too close. The fixed action pattern of aggressive behaviour is released mainly by the sign stimulus of the red breast, as shown by some simple experiments. Males attack crude models of robins with red breasts, or even a mere bundle of red feathers, but respond much less to accurate models without red breasts (Fig. 8.7).34

Figure 8.7 Two models exposed to European robins during the breeding season. They attacked the tuft of red feathers on the right far more than a stuffed robin with a dull brown breast (left), showing that attacking behaviour is released mainly by the sign stimulus of the red breast. (After N. Tinbergen, The Study of Instinct, Oxford University Press, 1951)

These features of inherited behaviour fit very well with an interpretation in terms of hierarchically organized morphic fields. The fixed action patterns can be thought of as chreodes; sign stimuli, such as the red feathers attacked by robins, play the role of morphogenetic germs. They do so by setting up, through the senses, characteristic rhythmic patterns of activity within the nervous system, which enter into morphic resonance with particular behavioural fields – in the case of male robins responding to the sign stimulus of red feathers, the fields of attacking behaviour.

Behavioural chreodes canalize behaviour towards particular end-points (often called consummatory acts), and like morphogenetic chreodes have an inherent capacity to adjust or regulate the process so that the end-point is achieved in spite of fluctuations and disturbances. Ethologists have in fact observed that many fixed action patterns show a ‘fixed’ component and an ‘orienting’ component that is relatively flexible. For example, a greylag goose will retrieve an egg that has rolled out of the nest by putting its beak in front of the egg and rolling it back towards the nest (Fig. 8.8). As the egg is being rolled, its wobbling movements are compensated by appropriate side-to-side movements of the bill.35 These compensatory movements occur in a flexible way, in response to the movements of the egg, within the framework of the fixed pattern of rolling; if the egg is suddenly removed they cease, but the movement of the bill towards the chest, once initiated, proceeds to completion.

Figure 8.8 A classic example of a fixed action pattern: a greylag goose rolling an egg back into its nest. The goose invariably attempts to roll the egg using its bill in this manner, rather than by using its foot or wing, or by using its bill in some other way. (After N. Tinbergen, The Study of Instinct, Oxford University Press, 1951)

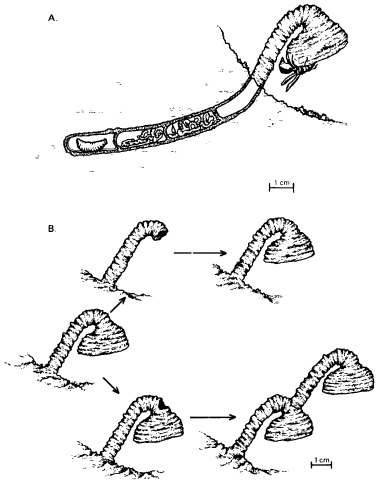

The similarities between behavioural and morphogenetic chreodes, with their inherent regulatory capacities, are shown most clearly in patterns of behaviour that involve the building of structures such as nests. For example, female mud wasps of a Paralastor species in Australia build and provision underground nests in an elaborate way. First they excavate a narrow hole about 3 inches long and 1⁄4 inch wide in a bank of hard, sandy soil. Then they line this with mud. The mud is made by the wasp from soil near the nest; she releases water from her crop onto the soil, which she then rolls into a ball with her mandibles, carries into the hole, and uses to line the walls. When the hole has been fully lined, the wasp begins to construct a large and elaborate funnel over the entrance, building it up from a series of mud pellets (Fig. 8.9A). The function of this funnel appears to be the exclusion of parasitic wasps, which cannot get a grip on the smooth inside of the funnel; they simply fall out when they try to enter.

Figure 8.9 A: The nest, stocked with food, of the wasp Paralastor. B: The repair of funnels by Paralastor wasps. Above, the construction of a new funnel after the old one has been removed by the experimenter. Below, the extra stem and funnel made by the wasp in response to a hole above the normal funnel. (After S. A. Barnett, Modern Ethology, Oxford University Press, 1981)

After the funnel is completed, the wasp lays an egg at the end of the nest hole, and begins provisioning the nest with caterpillars, which are sealed into cells, each about 3⁄4 inch long. The last cell, nearest the entrance, is often sealed off empty, possibly as a protection against parasites. The nest hole is then sealed with a plug of mud, and the wasp destroys the carefully constructed funnel, leaving nothing but a few scattered fragments lying on the ground.

This is a sequence of fixed action patterns, governed by behavioural chreodes. The end-point of each of these chreodes serves as the sign stimulus or germ structure for the next. As in morphogenesis, if the normal pathway of activity is disturbed, the same end-point can be reached by a different route.

The ways the wasps react to damage of the funnel while it is under construction illustrate these general principles. First, in experiments carried out in the wild, funnels that were almost complete were broken off while the wasps were away collecting mud. However much of the funnels was missing, the wasps recommenced construction and rebuilt them to their original form; the funnels were regenerated. If they were broken off again, they were again rebuilt. This process was repeated seven times with one particular wasp, which showed no signs of reduced vigour as it rebuilt its funnel again and again.36

Second, the experimenter stole almost completed funnels from some wasps and transplanted them to other nest holes where funnel construction was just beginning. When these wasps came back with pellets of mud and found the instant funnels, they examined them briefly inside and out, and then finished constructing them as if they were their own.

Third, the experimenter heaped sand around funnel stems while they were being constructed. The stems are normally about an inch long. If a nearly completed one was buried until only about 1⁄8 inch was showing, the wasp built it up until it was again about an inch above the ground.

Finally, various holes were made in the funnels at different stages of construction. If these were made at an early stage, or if they involved removal of material from the bells of the funnels, the damage was detected at once, and the damaged area was repaired with strips of mud until the funnel assumed its previous form.

The most interesting behaviour occurred in response to a type of damage that would probably never happen under natural conditions: a circular hole made in the neck of the funnel after the bell of the funnel had been built. The wasps on their return soon noticed these holes and examined them carefully from the inside and the outside, but they were unable to repair them from the inside because the surface was too slippery for them to get a grip. After some delay the wasps started adding mud to the outside of the hole. This is just the type of activity that occurs when they start constructing a funnel over the entrance hole of the nest. The holes in the neck of the funnel thus came to act as a sign stimulus for the entire process of funnel construction, and a complete new funnel was made (Fig. 8.9B).

Thus behavioural fields, like morphogenetic fields, have an inherent goal-directedness, and enable animals to reach their behavioural goals in spite of unexpected disturbances, just as developing embryos can regulate after damage and produce normal organisms, and just as plants and animals can regenerate lost structures.

The inheritance of behavioural fields

Hereditary behaviour, like hereditary form, is influenced by genes, but it is neither ‘genetic’ nor ‘genetically programmed.’ On the hypothesis of formative causation, its characteristic patterns are organized by morphic fields inherited by morphic resonance from past members of the same species.

Behavioural fields organize particular patterns of behaviour, such as fixed action patterns like the attacking behaviour of robins and the funnel-building activities of Paralastor wasps.

The expression of the behaviour organized by these fields can be influenced by mutations in many different genes, but the effects of the genes on the behaviour may be very indirect. Some result in abnormal sense organs, nervous systems, or musculatures, which can, of course, affect the ways in which an animal behaves. Other mutations affect behaviour by general effects on the vigour of animals.37 But such mutations do not in themselves determine the patterns of behaviour; they merely affect the ways in which these patterns can be expressed.

Studies on the inheritance of fixed action patterns have shown that there are indeed numerous genetic mutations that affect performance in various minor ways, but any given behavioural pattern still appears in a clearly recognizable form if it appears at all.38 In terms of the TV analogy, these mutant organisms are like faulty TV sets containing, ‘mutant’ components that bring about distortions in the sound or pictures. Nevertheless, in spite of these disturbances, the program remains clearly recognizable. The set remains tuned to the same channel.

In addition to the various mutations that affect the expression of a given behavioural field, we might expect to find other kinds of mutations, analogous to homeotic mutations of form (see above), in which entire fixed action patterns disappear or are replaced by others. In terms of the TV analogy, these mutations affect the tuning of the set in such a way that an entire channel is lost or another program is received instead. Such mutations do indeed exist. They affect the appearance or non-appearance of entire fixed action patterns, just as homeotic mutations affect entire organic structures.

One of the few examples studied in any detail concerns the nest-cleaning behaviour of honeybees in America in response to the American foulbrood disease, which kills larvae within the honeycomb. In one strain, called Brown, the worker bees uncap the cells in which larvae have died and remove the corpses from the comb. In another strain, van Scoy, they do nothing about the dead larvae. This leads to further infection. Colonies of the Brown strain are more resistant to foulbrood disease than van Scoy colonies as a consequence of their hygienic behaviour.

Crosses between queens from one strain and drones from the other gave rise to hybrid queens that built up hybrid colonies. These colonies turned out to be unhygienic, showing that the hygienic behaviour is recessive.39 From the point of view of formative causation, these fixed action patterns are not coded in the genes, but rather the genes somehow affect the tuning of the bees’ nervous systems such that morphic fields for these patterns of behaviour come into play or they do not. Rather than genes ‘for’ these patterns of behaviour, there are morphic fields for such patterns.

When two species are crossed, the instinctive behaviour of the hybrids often exhibits elements of the instincts of both parents. Sometimes the inherited patterns of behaviour conflict, as in crosses between two species of lovebird. Birds of one species make their nests from strips of leaves, which they tear off and carry to the nest in their bills. Birds of the other species carry strips of leaves to the nest tucked in among their feathers. Hybrids behave in a most confused manner, attempting to tuck in strips of leaves among their feathers, but so ineffectively that the strips drop out. They learn eventually that the only way they can carry them to the nest successfully is in their bills, but even then they still make attempts to tuck them in.40

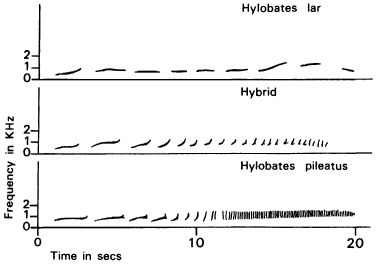

In many cases, the hybrid’s behaviour is intermediate between the parental patterns, as shown particularly clearly in calls and songs, which have the advantage that they can be recorded and represented quantitatively. For example, female gibbons make impressive sounds in the morning in the presence of their mates, known as great calls. Different species make different calls. In the jungles of central Thailand, two species live in the same area and occasionally interbreed. The females of both species make great calls of similar length (14 to 21 seconds) and within a similar range of pitch. But one species utters on average 8 notes per call, the other averages 73. Hybrids between the two species, both in the wild and in zoos, make calls that are intermediate41 (Fig. 8.10).

Figure 8.10 Sound spectrograms of the great calls of gibbons in the wild in Thailand. The calls of the hybrids are intermediate between those of the parent species. (After Brockelman and Schilling, 1984, copyright © Macmillan Magazines Ltd.)

The conventional theory and the hypothesis of formative causation interpret the known facts about the inheritance of behaviour differently; but the available facts do not enable us to decide which is the better interpretation. However, the two hypotheses lead to different predictions in cases in which animals acquire new patterns of behaviour. According to the conventional theory, such acquired abilities should have no hereditary effect on the offspring. By contrast, by morphic resonance there should be a tendency for the new pattern of behaviour to be learned more readily by other members of the breed, even in distant parts of the world. These predictions can be tested, and experiments are discussed towards the end of the following chapter.

Studies with identical twins

The relative importance of nature and nurture, or heredity and environment, is not only a scientific but also a political question. In fact politics has overshadowed science in this area since the middle of the nineteenth century. For example, in England, the liberal philosopher John Stuart Mill (1806–73) preached a gospel of social progress, whereby political and economic reforms can change human nature through changing the environment, ideas that had a strong influence on progressive political movements like socialism and communism.

On the other hand, Francis Galton, Charles Darwin’s cousin, made a strong scientific case for the predominance of heredity. In his book Hereditary Genius (1869), he argued that the prominence of Britain’s most distinguished families depended more on nature than on nurture, and came to a controversial conclusion:

[M]an’s natural abilities are derived by inheritance, under exactly the same limitations as are the form and physical features of the whole organic world. Consequently, as it is easy, notwithstanding those limitations, to obtain by careful selection a permanent breed of dogs or horses gifted with peculiar powers of running, or of doing anything else, so it would be quite practicable to produce a highly-gifted race of men by judicious marriages during several consecutive generations.

Galton realized that the question of nature and nurture could be studied with the help of identical twins, who had a similar heredity constitution, while non-identical twins were no more similar than ordinary brothers and sisters. He found remarkable similarities between identical twins in a wide range of characteristics including the onset of disease and even time of death,42 and his investigation of twins remains one of the classic studies in behavioural genetics.

Galton proposed that the state should regulate the fertility of the population in such a way as to favour the improvement of human nature through selective breeding, for which he coined the name eugenics. The eugenics movement had a large influence in the United States and reached its apogee in Nazi Germany. Not surprisingly, Nazi scientists were very interested in twins. The notorious Josef Mengele’s favourite project at the Auschwitz death camp was a study of identical twins, who were kept in special barracks and treated better than other prisoners. Mengele told his one of his colleagues: ‘It would be a sin, a crime … not to utilise the possibilities that Auschwitz had for twin research. There would never be another chance like it.’43

One consequence of Nazism was that eugenics in general and twin studies in particular were discredited for a generation. This left the field open for the environmental theories of the Behaviourists, who strongly believed in the possibilities of social engineering through the conditioning of children. The founder of behaviourism, John B. Watson, claimed: ‘Suppose we were to take individual twins into the laboratory and begin rigidly to condition them from birth to the twentieth year along utterly different lines. We might even condition one of the children to grow up without language. Those of us who have spent years in the conditioning of children and animals cannot help but realize that the two end products would be as different as day is from night.’44

After the second world war, the leading figure in research on identical twins was the British educational psychologist Sir Cyril Burt, who claimed to have studied 53 pairs who had been reared apart. Burt focused on the inheritance of intelligence, as measured by IQ tests, and claimed that genetics had a far stronger influence than the environment. Unfortunately for genetic determinists, Burt was later shown to have faked some of his data.45 But despite this setback, with the cracking of the genetic code and the growth of molecular biology in the 1960s, molecular genetics gained enormously in prestige and influence. With the rise of sociobiology in the 1970s and the popularisation of neo-Darwinian ideas by Richard Dawkins in his book The Selfish Gene (1974), genetic determinism gained a predominant cultural influence that was reinforced by new studies of twins.

The Minnesota Twin Family Study, the largest twin project in the world, was established in 1989. The Minnesota team found that there were high correlations between identical twins separated at birth for a variety of personality characteristics, such as a sense of wellbeing, social dominance, alienation, aggression, achievement and IQ. Their IQ results were almost identical to those that Cyril Burt was accused of fabricating.46

The Minnesota studies also revealed some very surprising biographical similarities. For example, the ‘Jim’ twins (who had both been called James by their adoptive families), who were separated soon after birth, showed extraordinary similarities in their life histories. Both lived in the only house on the block, with a white bench around a back tree in the backyard; both were interested in stock car racing; both had elaborate workshops where they made miniature picnic tables or miniature rocking chairs.47 They also had parallel health histories including a lazy eye in the same eye; both experienced what they thought were heart attacks though no disease was diagnosed; and both had had vasectomies.48

Some pairs of twins also had similar fears and phobias. The Minnesota researchers concluded: ‘The diverse cultural agents of our society, in particular most parents, are less effective in imprinting their distinctive stamp on the children developing within their spheres of influence – or are less inclined to do so – than has been supposed.’49

There have been many studies of pairs of twins who were not separated at birth, comparing monozygotic with dizygotic twins. For example, in a study in Virginia with 1000 female twins, a wide range of behaviours like smoking, choice of careers or hobbies and menstrual symptoms were much more similar with identical than fraternal twins, again suggesting a strong influence of heredity.50

Through twin studies, behavioural geneticists made a strong case that much of our identity is genetically determined. This belief, combined with the high prestige of molecular biology, contributed to the launching of the human genome project and the biotechnology bubble that accompanied it.

Morphic resonance provides a new way of looking at the data from studies of identical twins, and could help to liberate this subject from the political controversies that have dogged it for so long.

Because they are genetically identical, monozygotic twins are much more similar to each other than any other pairs of humans. Hence morphic resonance between them will be exceptionally specific and stronger than that between any other pairs of humans. As a result, patterns of activity, beliefs, habits or health patterns in one are likely to influence the other. Hence many of the remarkable similarities between identical twins may depend on morphic resonance, rather than genes.

‘Missing heritability’ and the human genome project

One of the hopes that lay behind the human genome project was that individual genetic differences would predict personal predispositions to disease, and hence play a major role in individualized medicine. It has long been known that some hereditary diseases depend on simple genetic differences. For example cystic fibrosis results from mutated genes, and affects almost everyone who has these genes. But most common diseases are very different. Beginning soon after the turn of the millennium, large-scale studies, known as genome-wide association studies, searched for genes associated with a range of characteristics, including the predisposition to disease. The results were shockingly unexpected.

Take height for example. Studies in the twentieth century showed that the height of parents is closely related to the height of their children. Based on a comparison of parents and children, height is 80 to 90 per cent heritable, which is to say that 80 to 90 per cent of the variation of height in the population can be ascribed to heredity. Three independent groups of researchers scoured the genomes of tens of thousands of people for genetic differences associated with differences in height; more than 40 genetic variations showed up. But these genes turned out to have tiny effects. Altogether, they accounted for only about 5 per cent of the heritability of height, despite the fact that height is 80 to 90 per cent heritable. This is one of many examples of ‘missing heritability’.51

Another large-scale study identified 18 genes associated with adult-onset diabetes. But together they explain less than 5 per cent of the inherited liability to diabetes. Again, much of the heritability is missing.52

How can this ‘missing heritability’ be explained? Some researchers suggest that very large numbers of genes may be involved, each with very small effects. If so, the predictive value of the genome will always be very low. Others suggest that epigenetic inheritance may account for some of the differences. But there is a serious worry that something has gone wrong. Leonid Kiuglyac, an evolutionary biologist, commented in 2008, ‘You have this clear, tangible phenomenon in which children resemble their parents. Despite what students get told in elementary school science, we just don’t know how that works’.53 And in 2009, the geneticist Steve Jones observed: ‘Just a couple of years ago there was real optimism that a new era of understanding was around the corner, but it did not last long, for hubris has been replaced with concern … The evidence of genetic inheritance is clear but the genes themselves are just not there.’54

Once again, morphic resonance can help in understanding these otherwise puzzling facts. If much of inheritance depends on morphic resonance rather than on genes, the missing heritability is easy to understand. In fact the amount of missing heritability gives a rough measure of the contribution of morphic resonance.

Morphic resonance and heredity

In this chapter, we have seen how morphic resonance sheds new light on heredity, which depends both on genes and on morphic fields, inherited by morphic resonance. The form and behaviour of organisms are not coded or programmed in the genes any more than the shows picked up by a TV set are coded or programmed in its transistors or other components.

The orthodox genetic theory of inheritance projects the properties of morphic fields onto genes, and attempts to squeeze them into the molecules of DNA. Thus most biologists imagine that there are genes, rather than morphic fields, for particular structures, such as the legs of fruit flies, and for patterns of behaviour, such as the funnel-building activities of Paralastor wasps (Fig. 8.9). Genes, rather than morphic fields, are assumed to be dominant or recessive; and the evolution of dominance is believed to depend on ill-defined genetic changes, rather than on the cumulative building up of habits by morphic resonance from large numbers of similar organisms in the past.

The possibility of the inheritance of acquired characteristics used to be denied on theoretical grounds because it could be explained in terms of genes. But there is good evidence that this kind of inheritance occurs, and both epigenetic inheritance and morphic resonance may help to account for it.

Twin studies have given grossly exaggerated estimates of genetic inheritance, because many of the similarities between identical twins may depend on morphic resonance. And the high hopes that genomics would have great predictive power have been dashed by the discovery of missing heritability, again in accordance with the hypothesis of morphic resonance. But some scientists still put their faith in the predictive power of the genome, like Lewis Wolpert. He and I have a wager on this subject, as described in Chapter 5.

Without the concept of morphic resonance, the role of genes was inevitably overrated, and properties were projected onto them that go far beyond their known chemical roles. Likewise, in relation to learning and memory, to which I now turn, properties were projected onto nervous systems that go far beyond anything that they are actually known to do. Brains, like genes, have been systematically overrated.