The British species, part 1: Ensifera

Bush-crickets, crickets and their relatives

This large subdivision of the Orthoptera includes nine (or ten; see Gwynne, 2001 and Chapter 2) orthopteran families worldwide, of which only five are represented in the British fauna. These are: the Tettigoniidae (the bush-crickets or ‘katydids’); the Gryllidae (the true crickets); Mogoplistidae (scaly crickets); Gryllotalpidae (mole-crickets); and the Rhaphidophoridae (camel-crickets and cave weta).

The derivation of the word ‘Ensifera’ suggests a reference to the sword-shaped external ovipositor that is a characteristic feature of the families belonging to the suborder (although the true crickets have more needle-shaped ones!). Another characteristic feature is the long – often much longer than the body – pair of filamentous antennae possessed by both sexes. There are also internal structural differences and characteristics of DNA shared by all groups within the suborder that justify their treatment as a single ‘clade’ (i.e. as sharing a common ancestor). The two families Raphidophoridae and the Tettigoniidae are generally classified together in the super-family Tettigoniodea, while the Gryllidae, Mogoplistidae and Gryllotalpidae are included together in the Grylloidea.

FAMILY RHAPHIDOPHORIDAE: THE CAMEL CRICKETS

Members of this family have much in common with the Tettigoniidae (bush-crickets), having long, filamentous antennae, four-segmented tarsi and swordlike ovipositors. They also resemble most bush-cricket species in their mating behaviour. During copulation the male transfers to the female a gelatinous spermatophore. This mass (which varies in size between species) contains both a sperm sac (ampulla) and an attached mass of edible material (the spermatophylax), which the female consumes while the sperm are transferred to her spermatheca (see Chapter 6).

The Rhaphidophoridae differ from most of the bush-crickets in being entirely wingless, and lack the hearing organ on the fore tibia. However, they do have a structure on the fore tibiae, called the subgenual organ, that enables the insects to detect substrate vibration. The pronotum is smoothly rounded, and both antennae and the cerci are much longer than is usual among the Tettigoniidae. There may be ten or more nymphal instars. Only one species has been established in Britain, probably introduced along with plants imported from southern China, although other accidental introductions of related species are occasionally reported.

THE GREENHOUSE CAMEL-CRICKET

Diestrammena (formerly Tachycines) asynamorus (Adelung, 1902)

MEASUREMENTS: Male: 12–14 mm in length; female: 14–18 mm in length (excluding the ovipositor); ovipositor: 10–12 mm; antennae: 65–70 mm.

FIGS A–C. Male; male, dorsal view; female.

Description

The pronotum is smoothly rounded, and the convex outline of the back when viewed from the side may explain the vernacular name. The ground colour is pale brown, with darker mottling and banding, especially on the rear margins of the pronotum and abdominal segments. The legs are also pale with dark banding. There are no wings, and no hearing organs on the fore tibiae. The legs, antennae, abdominal cerci and palps are also very long in relation to the size of the body. The four segments of each tarsus are also elongated and there are sparsely distributed long bristles on the legs and cerci.

Similar species

There are no similar British species, although there are reports of occasional accidental introductions of related species such as Dolichopoda bormansi from Corsica (Evans & Edmondson, 2007).

Life cycle

In the artificially heated environments where this species breeds in Britain, the life cycle is continuous through the year. The eggs are approximately 2–5 mm in length by 1–1.2 mm, and are laid singly or in small batches of up to 8 in soil. The eggs hatch after 8 to 10 weeks, depending on temperature, and the resulting nymphs pass through 8 to 10 or more instars to reach adulthood. This takes 6 to 10 months. As breeding is not governed by seasons, and the rate of nymphal development varies considerably in the same population, adults and all nymphal stadia may be found together. Nymphs are whitish in colour immediately after moulting, but acquire the characteristic brown-blotched pattern in a day or so. The cast-off skin is rapidly eaten after each moult. The ovipositor appears as a very small projection at the third instar, and becomes longer at each successive stage (see Chapter 3, Fig 59 for images of key developmental stages).

Habitat

In Britain this species is confined to artificially heated environments, such as greenhouses, warehouses or even garages. However, most British records are from garden centres or glasshouses with exotic plants. The two recently reported populations were living in plant nurseries, under wooden staging or paving slabs close to hot-water pipes, as well as in storage cupboards. The mid-winter temperature in one case was between 13°C and 17°C (Panter, 2007; Sutton, 2007b; own observations). During daylight hours the insects tended to be found hidden away in groups in dark, moist and warm locations.

Behaviour

Camel-crickets are nocturnal, and hide in dark corners during the day. In the absence of stridulation and developed hearing organs, it seems likely that they communicate by vibrations of the substrate, but they also cluster together in dark and damp places during daylight hours, constantly touching one another with their exceptionally long antennae. Courtship and mating seem to occur mainly at night, and male and female adults have been observed with the male resting a fore leg on the pronotum of the female. Ragge (1965) describes the male as attempting to push his abdomen under the female from various angles until he is able to crawl backwards underneath her. Mating lasts for 2 to 4 minutes, and during it a spermatophore is placed at the base of the female’s ovipositor. The spermatophore is white and gelatinous, approximately 3–4 mm in diameter, and is rapidly eaten by the female. The palps are used during feeding and general ‘searching’ behaviour, as well as by females in selecting suitable ovipositing sites. The female draws her ovipositor under her body so that it points directly down to the soil, moves slightly forwards and presses the tip into the ground. When it is fully inserted into the soil, egg-laying is indicated by a pumping motion of the abdomen (T. Kettle, pers. comm.).

Both sexes have very powerful back legs and can jump long distances when disturbed. They are therefore very difficult to catch. They are reputed to feed on other insects, including insect pests. However, staff at one plant nursery reported their penchant for the flesh of dead rats, and in captivity they ate rabbit flesh. Close observation of captive crickets by several observers produced no examples of them taking live prey. They appear to be generalised scavengers, feeding on a variety of plant material such as lettuce (where they bite holes in the leaf lamina), groundsel, carrot, apple, nectarine, as well as dead woodlice, mealworms and rabbit flesh. One instance was noted of a female feeding from the carcase of another camel-cricket. However, it seems likely that the ‘victim’ was either dead or moribund prior to being eaten! Early instars feed on small plants, including soil algae. At all stages, if provided with a range of ‘options’ for cover during the day, they will tend to roost together, and opt for the dampest situation.

History

Greenhouse camel-crickets were probably introduced into heated greenhouses in Britain (and much of the rest of Europe) in the latter part of the 19th century. In England the species has been recorded from widely scattered locations in Somerset, Sussex, Kent, Surrey, Middlesex, Suffolk, Cambridgeshire, Leicestershire, Derbyshire, Cheshire and Lancashire. It has also been recorded from Glamorgan, Glasgow, Edinburgh, Ayr and Dumfries. There are Irish records from Dublin. Post-1960 records given by Marshall & Haes (1988) include: plant nurseries at Canterbury (1962–5) and near Woking (1970–3); in the garage of a private house near Fleetwood, Lancashire (1975); and Dublin zoological gardens (1975).

The two most recent reports appear to be from a garden centre at Clowne, Derbyshire, where it was recorded in 2006 (and had been present, according to staff, for at least 10 years), and from another at Leicester (where it had been present for at least 15 years). In the face of the impending closure of the Leicester site, rescue attempts were made in December 2006 and January 2007 by G. Panter, H. Ikin, M. Frankum and P. Sutton. Small numbers of the crickets were retained in the hope that the population could be kept going in captivity, but these attempts proved unsuccessful in the long term. However, the Derbyshire population was fully recognised and positively valued by the centre management. John Kramer and the author visited the site on 8 December 2009, only to find that it, too, was due to close down. With the help and support of staff we collected as many of the crickets as could be found (causing some amusement and curiosity from customers). In all, we collected some 15 insects, several of them in various juvenile stages. These were kept in two old aquaria, in which they reproduced continuously, allowing several independent ‘colonies’ to be established during 2010, including a sample taken by Bristol Zoo. At the time of writing, one sample has reached a range of instars including adults in the third generation from the original stock.

Status and conservation

Accidental introductions with exotic plants imported from the Far East resulted in the spread of the camel-cricket throughout much of Europe in the 19th century. According to the owners of the garden centre in Leicester, their crickets had come in from plant stock imported mainly from Belgium, Holland and Denmark.

It seems quite possible that other populations of this species still survive in heated glasshouses somewhere in Britain, and efforts should be made to locate any other remaining populations. Meanwhile, a case could be made for a captive breeding programme to be established, using specimens from the known surviving British population.

References: Marshall & Haes, 1988; Ragge, 1965; Panter, 2007; Sutton, 2007b, 2011.

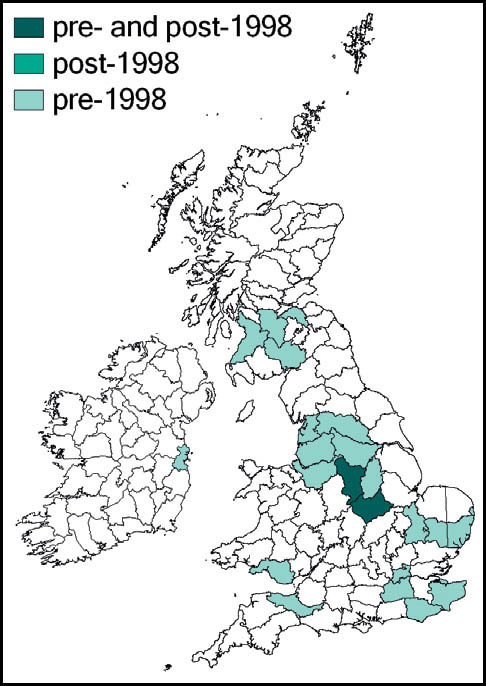

FAMILY TETTIGONIIDAE: THE BUSH-CRICKETS

Also known as ‘long-horned grasshoppers’ and, especially in North America and Australasia, as ‘katydids’, this family includes some of the most thoroughly studied of orthopteran groups. They number over 6,000 known species, and are distributed over the whole of the world, apart from Antarctica. The majority of species are nocturnal, and spend most of their time in vegetation. The females possess external sword-like ovipositors, which may be used for piercing plant tissue or, less commonly, for digging into soil. The antennae are long and filamentous and are used in an elaborate ‘fencing’ performance during courtship.

Along with crickets and grasshoppers, most species communicate by sound (see Chapters 2 and 5). In most species, males transfer an edible ‘nuptial gift’ to the female during mating, and this has provided researchers with a valuable way of exploring controversial issues in evolutionary theory, notably sexual selection and reproductive conflict between the sexes (see Chapters 4, 5 and 6).

The males sing by rubbing together their modified fore wings (or tegmina), as do the true crickets, but the bush-crickets are distinctive in scraping the left over the right tegmen. The songs of bush-crickets tend to be of a higher frequency than those of grasshoppers, close to, or above the limits of human hearing. The bush-crickets also have distinctive hearing organs, tuned to the frequencies of their songs, located on the basal area of the tibiae of their fore legs, and linked via an enlarged auditory vesicle to a spiracle on the thorax (see Chapter 2).

Many species in Britain have a life cycle lasting two or more years, with the first year (or more) spent in the egg stage. Most species pass through five or six nymphal instars, usually emerging as adults during mid to late summer. In winged species, the wing buds are inverted for the final two juvenile instars. In some species the wings are reduced, often, in males, consisting almost wholly of the stridulatory apparatus. Some species have both long-and short-winged forms.

Bush cricket (© Tim Bernhard)

THE OAK BUSH-CRICKET

Meconema thalassinum (De Geer, 1773)

MEASUREMENTS: Male: 12–17 mm in length; female: 11–17 mm in length.

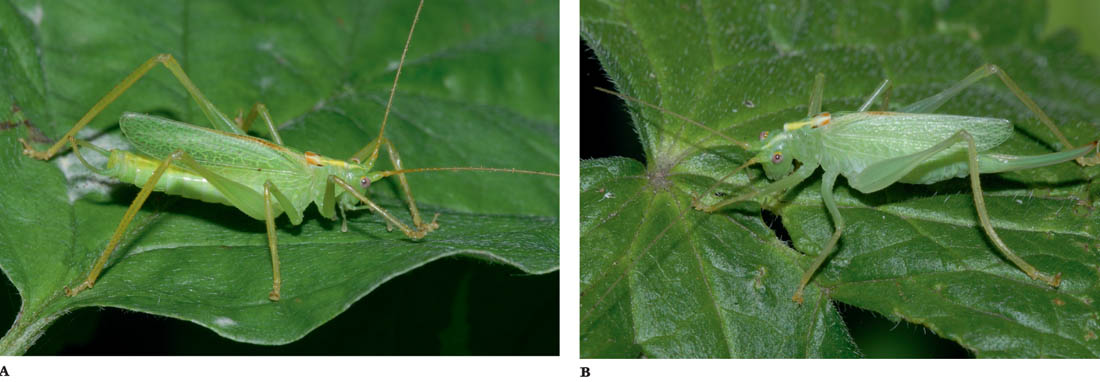

FIGS A–B. Male; female.

Description

The oak bush-cricket is pale green in colour and rather delicately built. Both sexes have an indistinct yellowish stripe along the middle of the dorsal surface of the abdomen that is continued onto the pronotum and head. However, on the dorsal surface of the pronotum it is flanked by two small black and two chestnut brown markings. The hind margins of the wings (i.e. the ‘ridge’ of the tent-like shape formed when the wings are folded) are often narrowly brownish, and the eyes are pale lilac. In mature specimens, the tibiae and tarsi are yellowish green. The adults are fully winged, the wings reaching back to approximately the tip of the abdomen. The wings of the male are not modified for stridulation. The male has a pair of long, curved cerci at the tip of his abdomen, and the female has a long, slightly up-curved ovipositor, which is green, usually shading to yellow and finally brown towards the tip (see the Key, Figs K3e and K5c).

Similar species

The great green bush-cricket (Tettigonia viridissima) is a much bigger and more sturdy insect, and is found in quite different habitats. The speckled bush-cricket (Leptophyes punctatissima) often occurs in the same haunts, but is a more compact insect, has only very tiny wing stubs, and, as the name suggests, is covered by minute black points. The southern oak bush-cricket (Thalassium meridionale) is a newcomer to Britain and a close relative of the oak bush-cricket. The two species look very similar, except that the southern oak has only very tiny wing stubs in the adult.

Life cycle

The eggs are laid from late summer to autumn, in crevices in the bark of trees, or under mosses or lichens. The eggs are buff-coloured, and approximately 3 mm by 1 mm in size. They may pass one or two winters in the egg stage, and hatch in late spring. The resulting nymphs pass through five nymphal instars to reach adulthood by late July or early August. The adults survive well into November in most years.

Habitat

They live among the foliage of trees – most commonly, as their vernacular name implies, in oak trees – but they can also be found in a wide range of other tree species as well as garden hedges and shrubs. There are even reports of their occurrence in reed beds (Haes, 1976). They are commonly found in urban and suburban parks and gardens.

FIG C. Characteristic ‘Hindu’ resting pose.

Behaviour

They are nocturnal, and during the day they rest on the underside of leaves, body pressed close to the leaf-lamina, and legs spread out in an angular pattern – rather resembling the image of a Hindu god. Even when present in gardens, they are extremely difficult to locate during daytime, but at night they are often attracted to light, and commonly enter houses, only to settle motionless on the ceiling.

When they are active, from dusk onwards, they walk about from leaf to leaf and onto the trunks or larger branches of trees. They can hop and also fly short distances. They feed mainly on small invertebrates, such as caterpillars and other larvae, aphids and even members of their own species. They will also consume some plant material but in captivity do not thrive on this alone.

There are some literature references to the males being able to produce a soft stridulation, but it seems that the main mode of communication is vibratory. The males issue a series of bursts of drumming on the substrate with one hind foot. This is Ragge’s description of the process:

Both pairs of wings are raised upwards until they are perpendicular to the body, and one of the hind feet is drummed on to the substrate (e.g. the surface of a leaf). The other hind leg is extended backwards to act as a support. The drumming is extremely rapid and is in very short bursts of less than a second. There are usually a number of these bursts, the first ones being of shorter duration than the remainder. The whole process lasts no more than a few seconds. During the drumming the abdomen also vibrates, but is held clear of the surface on which the insect is resting. (Ragge, 1965: 98)

Presumably females can detect the vibrations produced in this way and move towards the drumming male. During mating, the male encircles the female’s abdomen with his long, curved cerci.

Oak bush-crickets can be found by shining a torch beam on tree trunks in the evening, when females may be seen laying their eggs. Alternatively, sharply beating the lower branches of trees during the daytime with a stick while holding a specially designed beating tray (or an up-turned umbrella) beneath will usually dislodge them from their resting places. This technique is more successful for finding nymphs during June or early July. After high winds they can often be found on the ground under trees, and they can also often be found in spiders’ webs around outhouses and sheds. In gardens, if clippings from trees and shrubs are collected in garden bags, bush-crickets will find their way to the top within an hour or so and can be easily detected.

Enemies

It may be that they fall victim to nocturnal predators such as bats. In gardens, cats find and catch them, and they are frequently found in spiders’ webs. Smith (1972) gave an account of a pair of goldcrests bringing 31 oak bush-crickets to feed their young in just three hours of observation (Ragge, 1973).

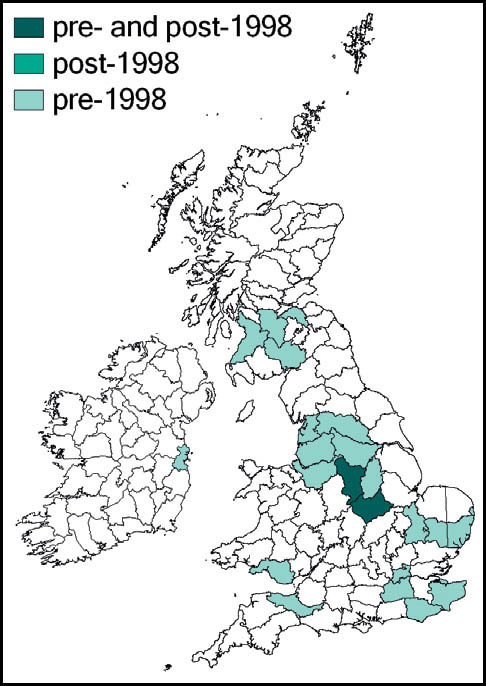

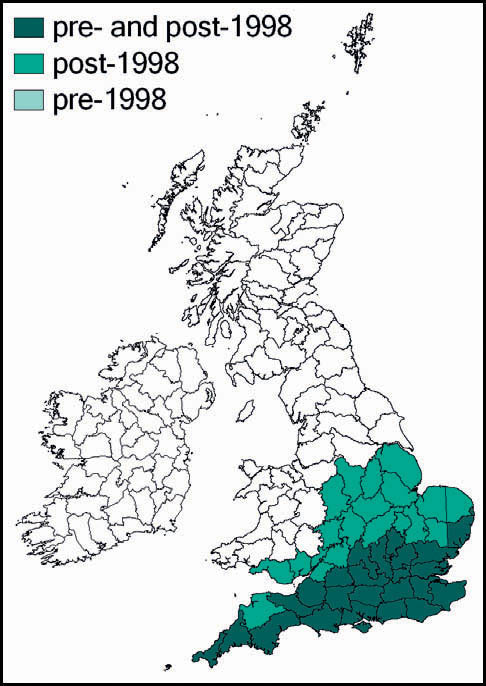

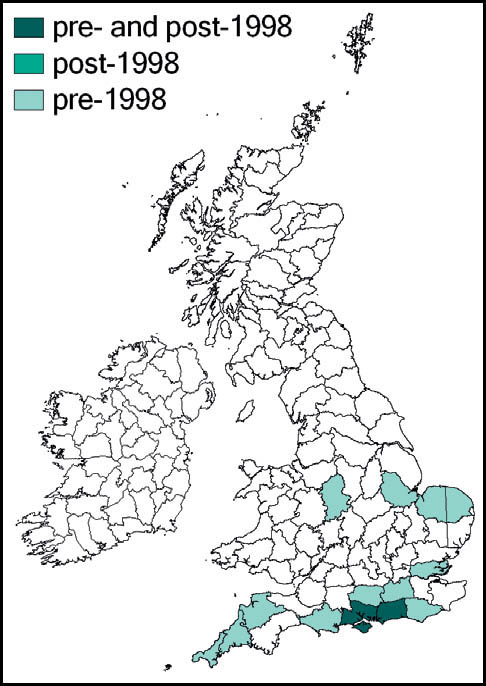

Distribution

The species is widespread throughout almost the whole of the European mainland. In Britain it is common and widespread in the southern and midland counties of England, becoming more localised further north, towards Yorkshire, Lancashire and Cumbria (Sutton, 2008a). It is widespread in Wales, and has a small number of known localities in Ireland.

Status and conservation

Although generally considered to be common and widespread, at least in the more southerly parts of Britain, some observers report that it has been less easy to find in recent years. It is difficult to see why this should be so, and it may simply represent a temporary cyclical contraction of the population.

References: Haes, 1976; Ragge, 1965, 1973; Smith, 1972; Sutton, 2008a.

THE SOUTHERN OAK BUSH-CRICKET

Meconema meridionale (Costa, 1860)

MEASUREMENTS: Male: 11–15 mm in length; female: 11–17 mm in length.

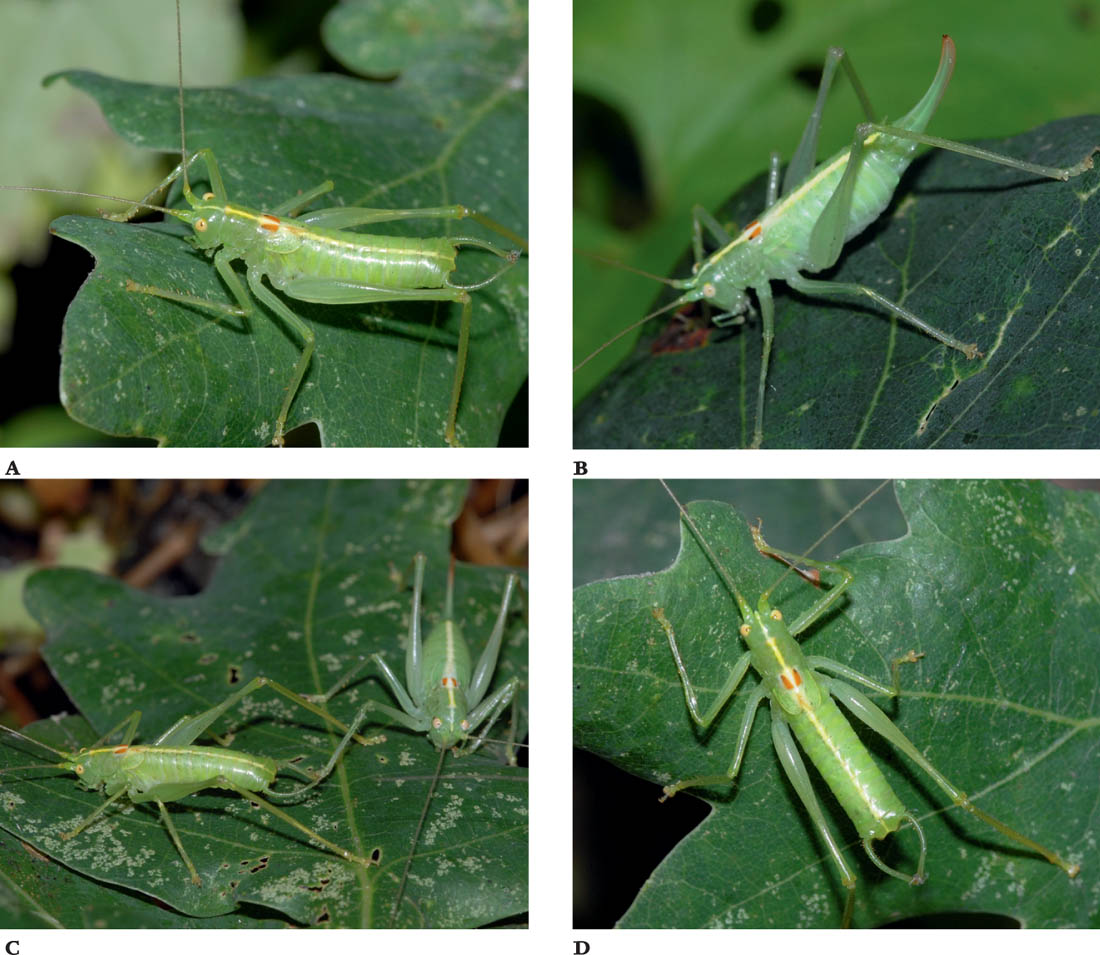

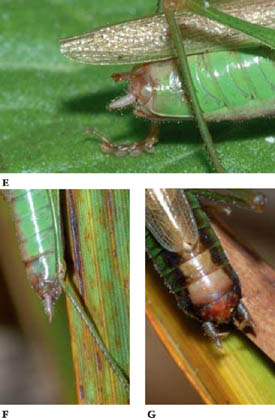

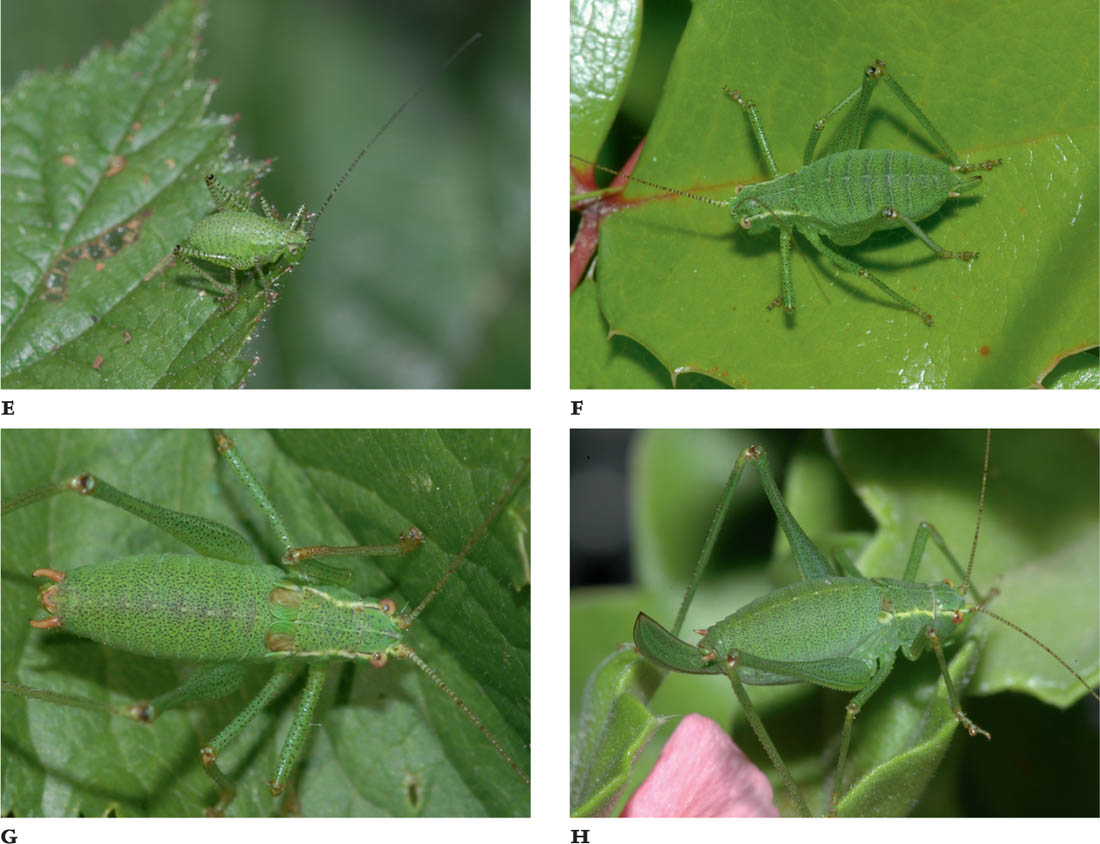

FIGS A–D. Male; female; male and female; male, dorsal view.

FIG E. Dorsal view, female.

Description

This species is very similar in appearance to the oak bush-cricket, but the most obvious difference is the lack of developed wings. In M. meridionale the wings are reduced to small stubs in both sexes. The body is mainly pale green, with a poorly defined yellowish stripe along the dorsal surface of the body. This is flanked by two wedge-shaped brown markings on the dorsal surface of the pronotum. In this species, where pairs of black spots are also present, they are merged into the brown markings at their anterior tips. The ovipositor is more distinctly up-curved towards the tip.

Similar species

The speckled bush-cricket (Leptophyes punctatissima) also has reduced wings and a pale green ground colour, but it is a more robust insect, and is covered with minute black points. The ovipositor of the female of the speckled bush-cricket is wider and more strongly up-curved.

The oak bush-cricket (M. thalassinum) is fully winged. There are other, minor differences: the eyes are usually cream to pinkish in M. meridionale, lilac in M. thalassinum, and the ovipositor is more sharply up-turned towards the tip in M. meridionale, regularly curved and slightly longer in M. thalassinum. Also, the patterns on the rear of the dorsal surface of the pronotum differ. In M. meridionale the paired black spots (where they are present) are fused with the brown wedges, but they are distinct in M. thalassinum. The shape of the tip of the male abdomen between the two cerci is also different in the two species, and the cerci of M. meridionale are slightly longer than those of M. thalassinum (see the Key, Figs K5c and e).

Life cycle

The adults are found from late July onwards and it is believed that the life cycle is closely similar to that of M. thalassinum. The eggs are laid in crevices in bark.

Habitat

The southern oak bush-cricket lives in oak trees as well as sycamore, elder, birch, maple, bay, and a range of garden shrubs.

Behaviour

During the day they are inactive and remain hidden among foliage. Although they cannot fly, they can jump well and can successfully avoid capture. Like the oak bush-cricket, they are nocturnal, and feed on small insects. In captivity they are cannibalistic, in particular taking advantage of nymphs when these are vulnerable after moulting. The males drum with one hind foot, although the pattern of taps (from 3 to 7 in succession (Hawkins, 2001)) is somewhat different from that of the oak bush-cricket. Hawkins describes the mating posture: with the male on his back, facing away from the female, but with his head raised to grip the ovipositor of the female with his mandibles. As in other bush-crickets, an edible spermatophore is transferred to the female during mating.

They can be found by beating lower branches of trees as described for the oak bush-cricket, by shining a torch beam onto tree trunks, and also by waiting for them to climb up to the surface of garden bags after pruning.

Enemies

Given the similarity between this and the oak bush-cricket it seems likely that they are vulnerable to the same predators.

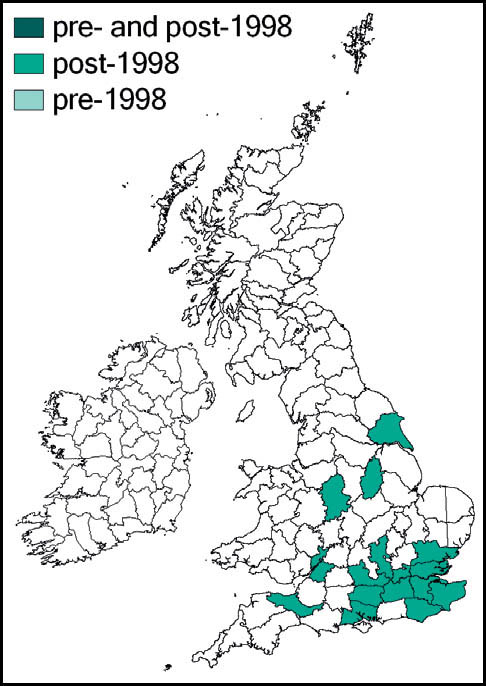

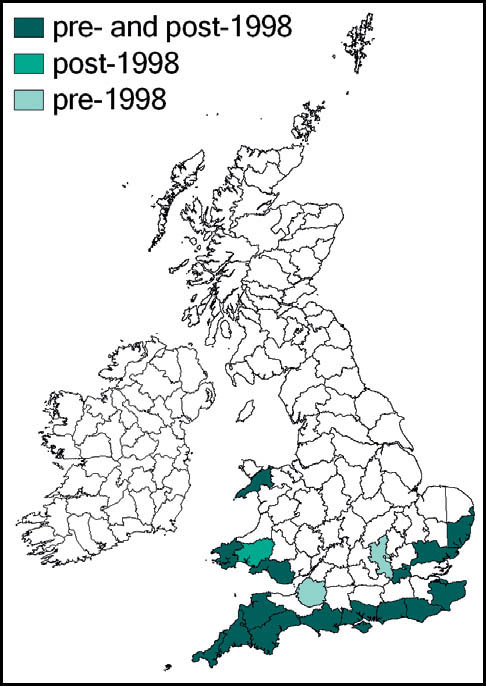

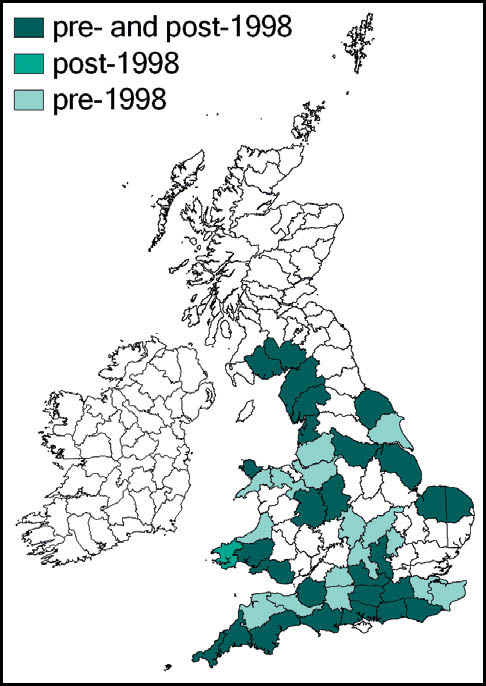

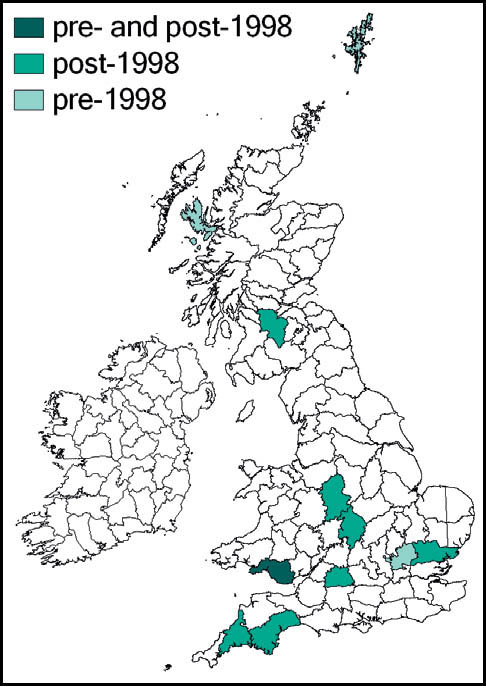

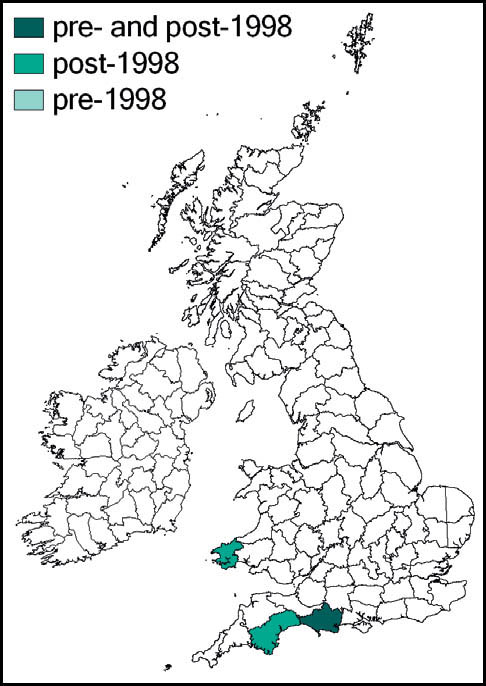

History

The species was first described from Italy, by Costa, in 1860. Prior to 1960 it was known also from eastern France and parts of Yugoslavia. Since 1960 its northward spread has been noted: from southern Germany and Austria and northern and eastern France to the Netherlands, Belgium and northern Germany in the 1990s. Between 1995 and 2001 it was recorded from more than 20 sites in Normandy. Its imminent arrival in Britain was predicted (e.g. Widgery, 2001a: 360) and the first British specimen was found by R. D. Hawkins by beating a birch tree growing in a garden near Thames Ditton railway station on 15 September 2001. Alerted by this discovery, D. Coleman found the insect at another Surrey site in the London suburbs, and this time it was confirmed that an established breeding colony was present. On 20 October 2001 yet another discovery of the species, this time in a garden in Maidenhead, Berkshire, was made (Hawkins, 2001). Retrospectively, the insect was identified as having been present in a London garden in 2001 (Sutton, 2004d).

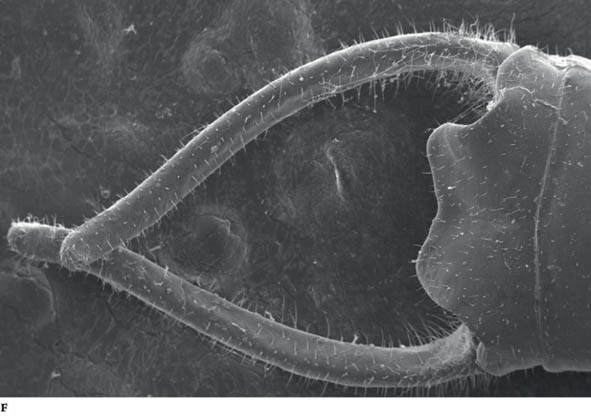

FIG F. Scanning electron microscope photo of male cerci, used to constrain the female during mating (see Chapter 6) (© K. Vahed).

Since 2001, the spread of reported British sightings has been remarkable:

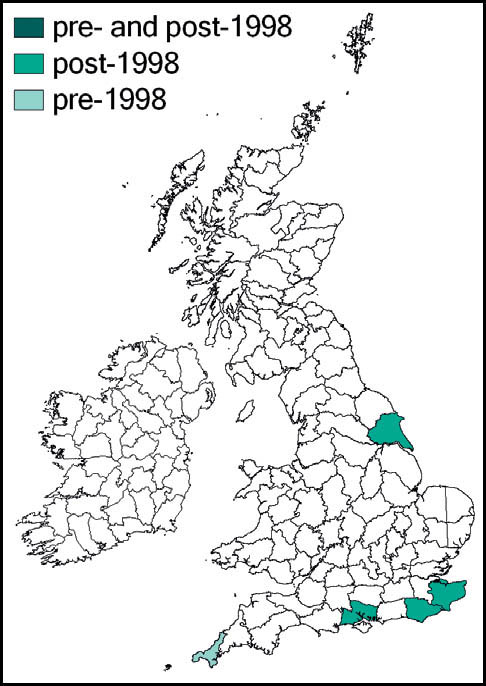

Distribution

The southern oak bush-cricket now appears to be an established breeding species at numerous localities in Greater London, Avon, Somerset, Berkshire, Buckinghamshire, Hampshire, Surrey, Sussex, Kent, and Essex, with outlying records from Nottinghamshire, Staffordshire and Yorkshire.

Status and conservation

It is generally accepted that this species was incidentally imported into Britain in horticultural produce, and may have established itself in several localities independently. However, the pattern of records suggests that it is also spreading out from its original introduction. As there appears to be no winged form, the general assumption is that its rapid spread is aided by its hitching lifts on motorised transport. Support for this is provided by an observation of an especially tenacious specimen that attached itself to a car and remained in place over a 150-mile drive (Edmondson, 2011). It seems likely that this species will continue to spread out from its strongholds in several southern and south-eastern counties of England.

References: Edmondson, 2011; Hawkins, 2001; Sutton, 2003a, 2004d, 2005b, 2006b, 2007a, 2007d, 2008a, 2008c, 2010a; Widgery 2001a.

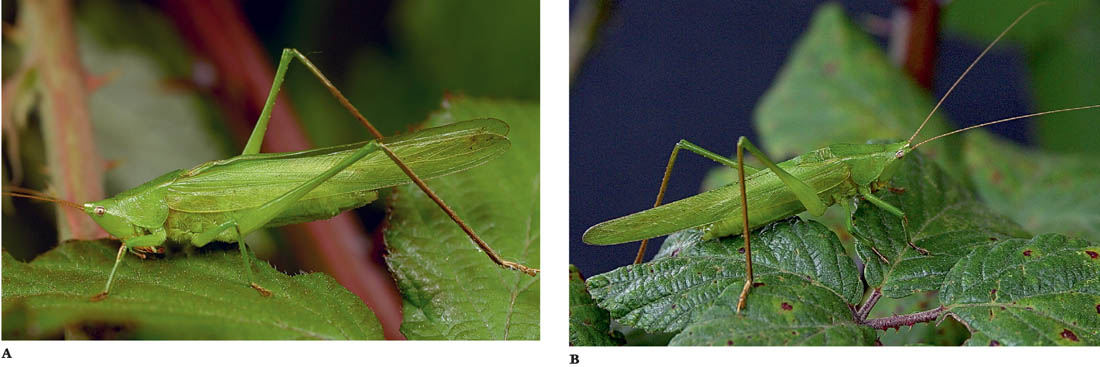

THE GREAT GREEN BUSH-CRICKET

Tettigonia viridissima (Linnaeus, 1758)

MEASUREMENTS: Male: 40–50 mm in length; female: 40–55 mm in length.

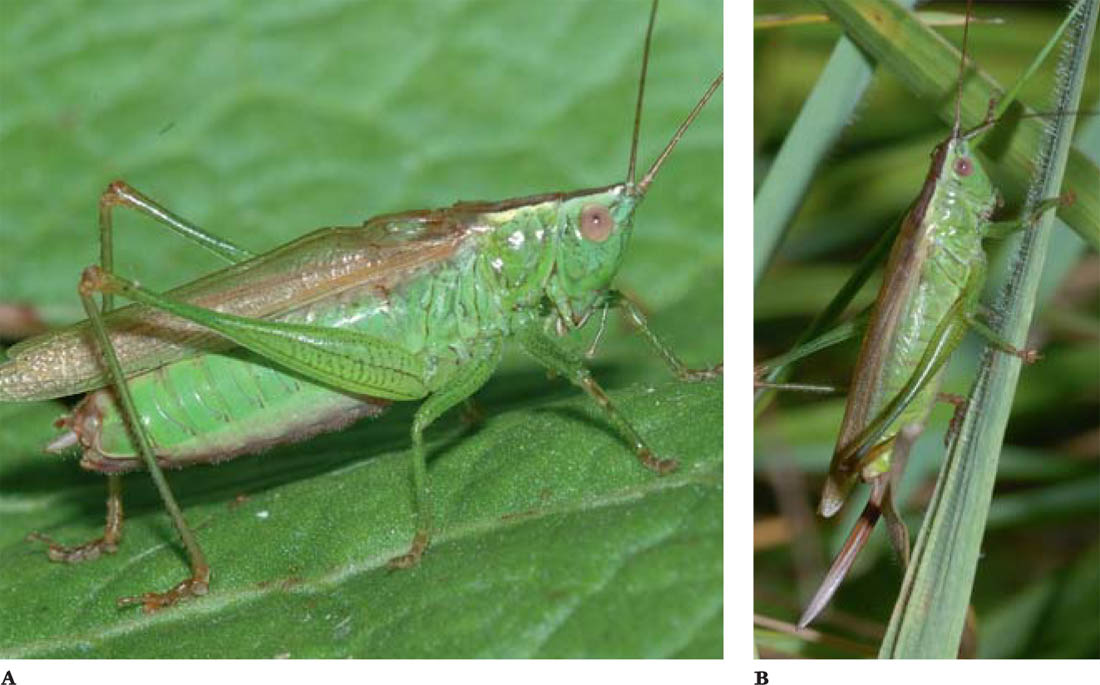

FIGS A–C. Male; female; male, dorsal view.

Description

This is the largest of the British Orthoptera, green in ground colour, and fully winged. The wings extend back well beyond the tip of the abdomen in males, and as far as, sometimes beyond, the tip of the long, straight ovipositor in the females. The male fore wings are modified for stridulation, with a ridged basal area on the left fore wing and a toothed ‘file’ on the underside. The right fore wing has a clear ‘mirror’ basally, that is covered by the left fore wing when the insect is at rest.

There is an ill-defined brownish dorsal stripe along the abdomen, and another along the leading edges of the fore wings, including the stridulatory area in the male. The yellow to brownish stripe is continued on the dorsal surface of the pronotum, and on the head often becomes lilac in colour. The eyes, too, are lilac. Most abdominal segments have a narrow yellow lateral ‘dash’ marking towards the ventral surface, just above the spiracle. Often the abdominal segments are indistinctly bordered laterally with brownish or purple tints. The legs frequently are flecked with tiny purple-black points.

Similar species

This species is quite distinctive, but superficially resembles the oak bush-cricket. However, that species is much smaller and more delicately built, paler in colour, and unlikely to be found in the same habitat as the great green.

In the very few localities where the wartbiter (Decticus verrucivorus) still occurs, the great green bush-cricket may sometimes also be found. However, the wartbiter has a much more compact, ‘chunky’ appearance, shorter wings (relative to its body length), and a markedly angled pronotum (smoothly saddle-shaped in the great green bush-cricket).

The recently established sickle-bearing bush-cricket (Phaneroptera falcata) has, as its vernacular name implies, a very differently shaped ovipositor in the female. In general, this species has a more frail appearance, with relatively longer and more ‘spindly’ legs. It is also is covered in minute black spots.

Nymphs of the great green bush-cricket are also minutely covered in tiny purple-black spots and could be confused with nymphs or adults of the speckled bush-cricket (Leptophyes punctatissima), but the body shapes of the two species are quite different.

Life cycle

The eggs are laid in soil during the summer, and pass two or more winters before hatching in late April or May. The number of nymphal instars varies, with a range from six to nine recorded. The nymphs are bright green with an indistinct brownish dorsal stripe and are densely marked with tiny purple-black points, especially on the legs. In early stages the wing stubs appear as small lobes pointing down behind the rear edge of the pronotum. In the final two instars the wing-stubs are reversed, and slight indications of the future venation are perceptible. The ovipositor is visible in the final three or four instars of the female, increasing in length with each moult. The adults are usually present by mid-July (4 July in East Sussex in 2009 (Sutton, 2009) is exceptionally early) and can be heard until the end of October (see Chapter 3, Fig 53 for images of selected developmental stages).

Habitat

The characteristic habitat is rank grassland in the process of succession to scrub, with clumps of bramble, or low hawthorn bushes providing a favoured song perch for the males. Females, too, use the upper branches of bushes to bask on warm days. The insect may also be found on south-facing slopes of downland, in hedgerows, and in gardens. In coastal and estuarine sites it is often abundant among Phragmites reeds along ditches and dykes, and in neglected ‘foldings’ on the landward side of sea defences.

Behaviour

The great green bush-cricket is nocturnal, but the males often begin to sing from mid-afternoon onwards. The song is one of the loudest emitted by any British orthopteran, and can be heard at distances of several meters (Ragge, 1965, says 200 metres, but this is presumably for those with better hearing than mine!). The tone is slightly metallic and rasping, and is produced in continuous, prolonged bursts. While singing, the male appears to ‘pump’ his abdomen rhythmically – presumably to enhance respiration. Even when singing, the cryptic coloration of a male perched among vegetation makes it very difficult to locate. There is some competition between males for song perches, and where the population is dense one may nip an intruder with his mandibles. The latter will usually dive down into lower vegetation. The females are inactive during the day, spending much of their time basking on sunny days. They, too, are surprisingly difficult to find for such large insects. When approached, they tend to rely on their cryptic appearance for protection, and remain static. If disturbed in a more determined way, they tend, unlike most other bush-crickets, to climb upwards through the vegetation. Even then, their movements are slow and awkward. They can fly, but do so rather reluctantly, and usually only for short distances.

They are omnivorous, including in their diet both vegetation and invertebrates such as caterpillars, aphids, flies and other orthopterans – including members of their own species. The great French entomologist Henri Fabre (1823–1915) recorded the feeding and courtship activities of this species in the south of France. This is his vivid description of the predation of the great green bush-cricket on a cicada.

In the dense branches of the plane-trees, a sudden sound rings out like a cry of anguish, strident and short. It is the desperate wail of the Cicada, surprised in his quietude by the Green Grasshopper, that ardent nocturnal huntress, who springs upon him, grips him in the side, opens and ransacks his abdomen. An orgy of music followed by butchery. (Fabre, 1917: 276)

Fabre found that, in captivity, they would eat a range of vegetable matter, including fruit, insects such as cicadas, and other delicacies: ‘The Green Grasshopper resembles the English: she dotes on underdone rump steak seasoned with jam’ (Fabre, 1917: 289).

Fabre also described the courtship activity of specimens in captivity. Head-to-head they ‘fenced’ with their long antennae (as do most bush-cricket species), while the male gave brief stridulations occasionally. Fabre notes that the process seemed interminable, but when he looked the following morning, mating had clearly taken place and a ‘green bladder-like arrangement’ (the spermatophore) was hanging from the base of the female’s ovipositor. After a couple of hours she consumed this, bit by bit.

Vahed & Gilbert (1996) measured the spermatophore in this species as weighing more than 22 per cent of the body weight of the male.

Enemies

Ragge (1973) refers to reports of this species being attacked by yellow buntings and by a house sparrow.

Distribution

The great green bush-cricket is widely distributed in Europe, North Africa and temperate Asia. In Britain it has a mainly southerly distribution, south of a line from the south Wales coast to the Wash.

Status and conservation

This species is very localised and is vulnerable to ‘tidy minded’ management of grassland. Its requirement for late succession patches and fringes with tall grasses and scrub can be accommodated by rotational management with long cycles.

References: Fabre, 1917; Ragge, 1965, 1973; Sutton, 2009; Vahed & Gilbert, 1996.

THE LARGE CONEHEAD

Ruspolia nitidula (Scopoli, 1786)

MEASUREMENTS: Male: 25–37 mm in length; female: 25–45 mm in length; ovipositor: 17–26 mm in length (Harz, 1969).

FIGS A–B. Male; male, showing stridulatory apparatus (both photos © B. Thomas).

Description

The large conehead is bright green, with a pale whitish line across the tip of its sharply conical head, and running back through the eyes. There is a fine black line along each tibia. The wings are very long, usually reaching back beyond the tip of the very long, straight ovipositor in females, and giving the insect a slender appearance. Brown and reddish forms are reported from mainland Europe.

Similar species

The great green bush-cricket (T. viridissima) is comparable in size, but the head shape of the large conehead is distinctive. The great green bush-cricket also has relatively shorter wings, and a dark band along the dorsal surface.

The long-winged conehead (C. discolor) is much smaller, and, like the great green bush-cricket, it has dark brown coloration on the dorsal surface, especially on the head and pronotum.

The song is loud and distinctive, enabling discovery and identification of the first British arrivals.

Life cycle

In southern Europe it has an annual life cycle, over-wintering in the egg stage. There is so far no clear evidence of its breeding in Britain, but occasional sightings indicate that the adults emerge relatively late in the year, from August onwards.

Habitat

In southern Europe its habitat is given as moist meadows and waste ground, but also dry fields with long grass (Bellmann, 1985; Bellmann & Luquet, 2009).

Behaviour

The spermatophylax ‘nuptial gift’ to the female is extremely small in this species (approximately 0.3 per cent of the male weight), and females, which mate only once, delay consumption of the ampulla (Vahed & Gilbert, 1996; Gwynne, 2001; see also Chapter 6).

The male song is a prolonged, continuous buzz that can last for 10 minutes or more. In this respect the song resembles that of M. roeselii, but it is an almost pure tone of about 13 to 20 kHz (Hathway et al. report a somewhat higher lead frequency), and is delivered almost exclusively at night (Ragge & Reynolds, 1998).

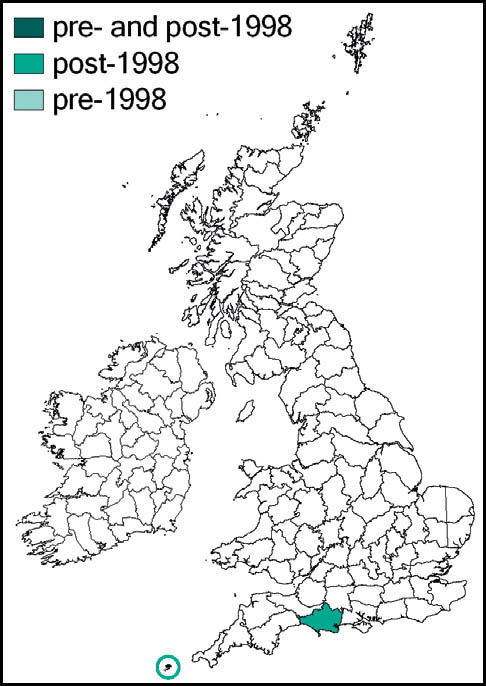

History

There are occasional reports of specimens incidentally imported in plant material (e.g. Nottingham and Northamptonshire, 2001 (Widgery, 2002)) but the first reports of the species arriving in the British Isles apparently unaided were from the Isles of Scilly in August and September 2003. Males were heard singing and subsequently captured and definitively identified on two islands: St Marys and St Agnes (Hathway et al., 2003; Sutton, 2003c).

A single male was located on Canford Cliffs, Poole, Dorset, in September 2005 and another at the same site in 2006 – suggesting the possibility of a breeding population (Sutton, 2006b).

Distribution

South and central Europe, Eastern Europe, North Africa and eastwards to Palaearctic Asia. It has been spreading northwards in mainland Europe in recent years, and was established in Normandy by 2002 (Sutton, 2003c).

Status and conservation

Given continued warming of the climate, it seems likely that this species will establish a breeding population in the British Isles (and it may have already done so).

References: Bellmann, 1985; Bellmann & Luquet, 2009; Evans & Edmundson, 2007; Gwynne, 2001; Hathway et al., 2003; Harz, 1969; Ragge & Reynolds, 1998; Vahed & Gilbert, 1996; Sutton, 2003c, 2006b; Widgery, 2002.

THE WARTBITER

Decticus verrucivorus (Linnaeus, 1758)

MEASUREMENTS: Male: 26–34 mm in length; female: 27–42 mm in length.

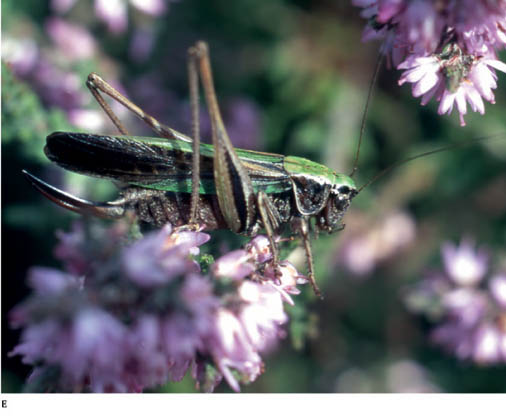

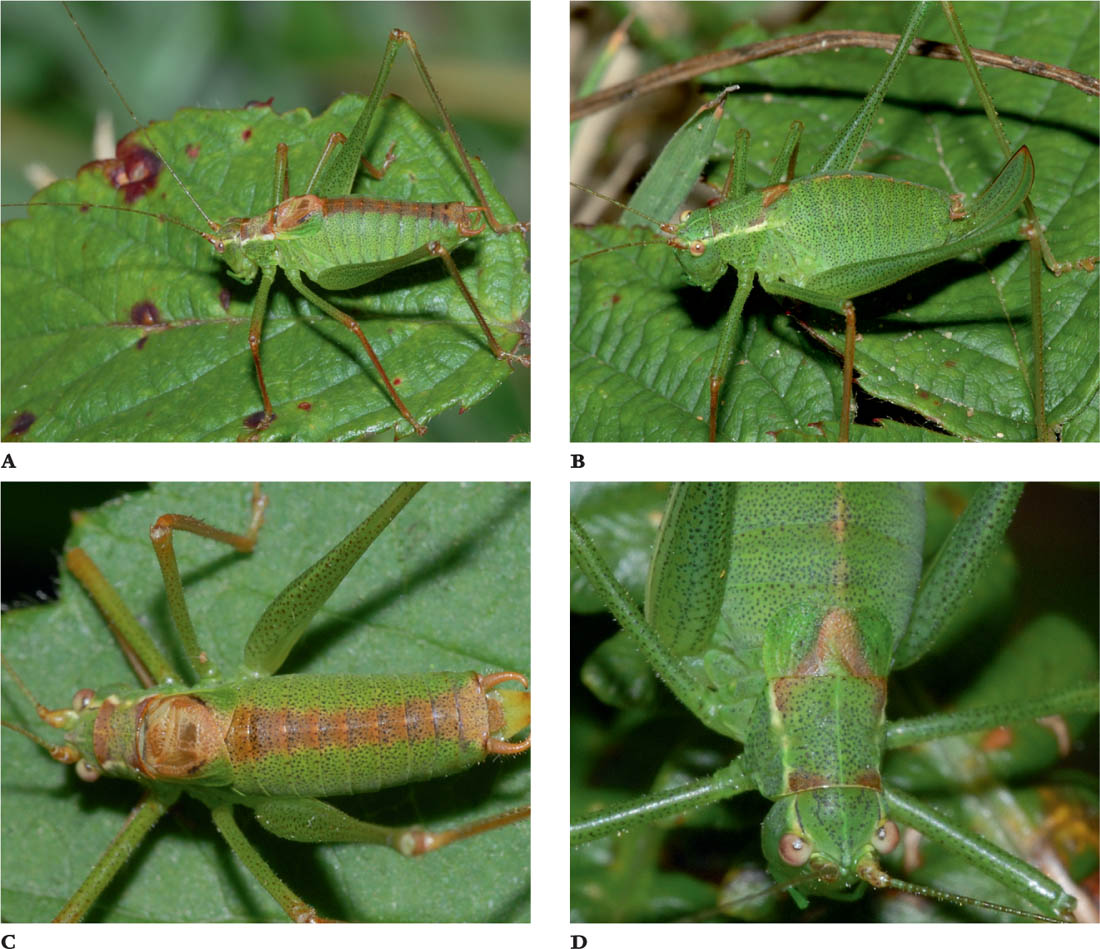

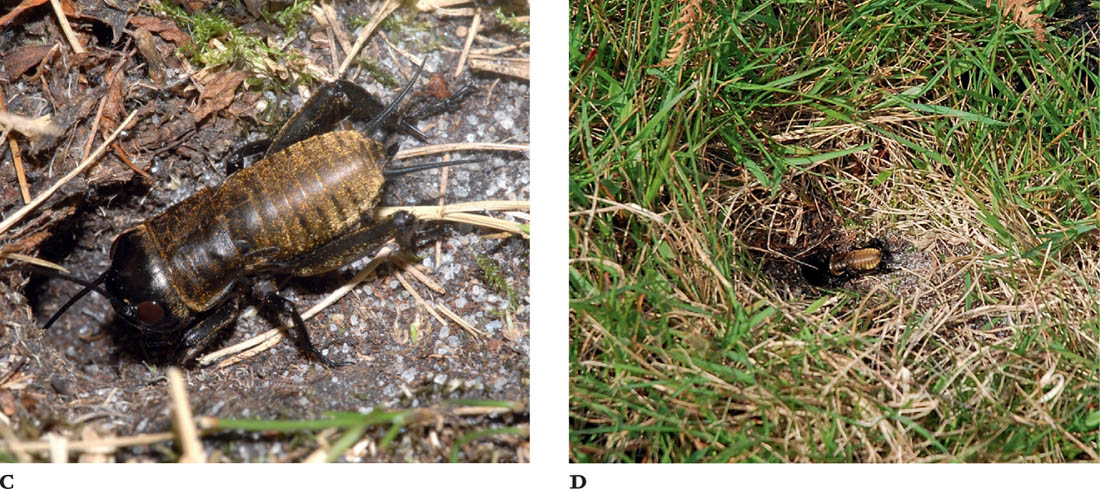

FIGS A–D. Male; plain green female; male, showing dorsal surfaces of pronotum and stridulatory apparatus; female, dorsal view.

FIGS E–F. Female with black markings; rare yellow and purple form (© P. Sutton).

Description

The wartbiter is a robust, ‘chunky’ insect. The adults are fully winged, but the wings barely reach back to the tip of the abdomen. The wings of the males are modified basally for stridulation. The head and pronotum have a smooth, shiny appearance. The pronotum is strongly angled at the sides, and has a fine median longitudinal ridge. The ovipositor is long, relatively narrow and slightly up-turned.

The typical form is bright green, often with variable amounts of dark brown to black blotching on the wings. There is also often a black mark on the rear margin of some of the abdominal segments. The eyes are very dark – contrasting with the green of the head. The base of the ovipositor in females is beige, shading to dark brown towards the tip. The stridulatory area of the left fore wing in the male is irregularly ridged and brown in colour in fully mature individuals. The cerci are yellowish, and have an inward-projecting tooth. The ventral surfaces of the hind femora are yellow, and the hind tibiae are pale lilac.

There are other colour forms, which are very rare in British populations: a grey form (f. bingleii – sometimes described as ‘brown’) was discovered in the main Sussex population in 1987, while a remarkable form with purple sides and yellowish wings also formerly occurred there. Neither has been seen since, although a partially purple form does occasionally occur (Cherrill & Brown, 1991a; Sutton & Browne, 1992; Sutton, 2009).

Similar species

It would be difficult to confuse this species with any other. Our only other species of similarly large size is the great green bush-cricket (T. viridissima), which does occur on some of the few remaining sites for the wartbiter. However, the great green bush-cricket is rather more slender in build, and has significantly longer wings relative to its body. Also the great green’s pronotum is smoothly rounded and saddle-shaped, contrasting with the strongly angled pronotum of the wartbiter.

The sickle-bearing bush-cricket (Phaneroptera falcata) is another large and fully-winged green bush-cricket. However, it is much more delicately built than the wartbiter, with long, spindly legs, and, in the female, a short, strongly curved ovipositor. So far, only one British locality is known for this species – one not shared with the wartbiter.

Life cycle

The greyish brown eggs are laid singly or in small batches in bare soil, or in short turf, to a depth of 0.5 to 2 cm from July onwards. They soon enter a resting stage, and remain in diapause until this is broken by cold winter weather. Embryonic development usually continues, with a further diapause which is broken by the onset of the next cold winter temperatures. The eggs thus usually hatch in the spring (early to mid-April) after their second winter. However, both in Britain and in mainland Europe this pattern is variable, and embryonic development can take up to seven years. There are seven nymphal instars. The rate of nymphal development is strongly dependent on sunny and warm weather, and the date at which development is completed varies from year to year. Usually adults appear from about the beginning of July and continue to emerge until the last week in July. However, adults have been recorded as early as mid-June, and in 1989 at the main Sussex locality, no nymphs were observed after 28 June. Development is slightly faster in males, which also have lower body weight. After the final moult both sexes increase in weight, especially females, which more than double their weight to an average of 2.1 grammes by late August. The weight gain in females is an indication of their fecundity, and as their weight increases with age, it is likely that they do not achieve their full reproductive potential if they encounter inclement weather in the latter part of their adult lives, or if poor weather in spring slows nymphal development. Depending on the weather in late summer and autumn, the adults can survive until mid-October.

Habitat

The wartbiter survives in a wide variety of habitat types further south in Europe, but in Britain it is at the northern edge of its range, and so has much more specialised requirements. The British populations are concentrated in a very small number of unimproved calcareous downland slopes, with one very precarious tiny population on grass/heather heathland. The downland population that has been most closely studied by A. Cherrill and colleagues has been shown to require a mosaic of dense tufts of tall grasses (Brachypodium pinnatum and Bromus erectus at the main study site) with areas of short turf and some bare ground. The short turf and bare ground are required for oviposition, and are also the habitat for early-instar nymphs. Sixth and seventh instar nymphs and adults are found more frequently associated with the tall grass tufts. In the few downland sites where they occur, population densities are greatest on south-facing slopes, compared with more easterly aspects where they also survive.

Their diet includes other invertebrates, and, not surprisingly, they are found in sites that are rich in other species of Orthoptera. On the south-facing slopes of their strongest British population they coexist with particularly large numbers of M. roeselii and C. discolor, along with T. viridissima, S. lineatus, C. parallelus, C. brunneus and O. viridulus.

In its heathland habitat the mosaic vegetation structure may be comparable to that on downland, with taller heathers interspersed with sedges and fine grasses.

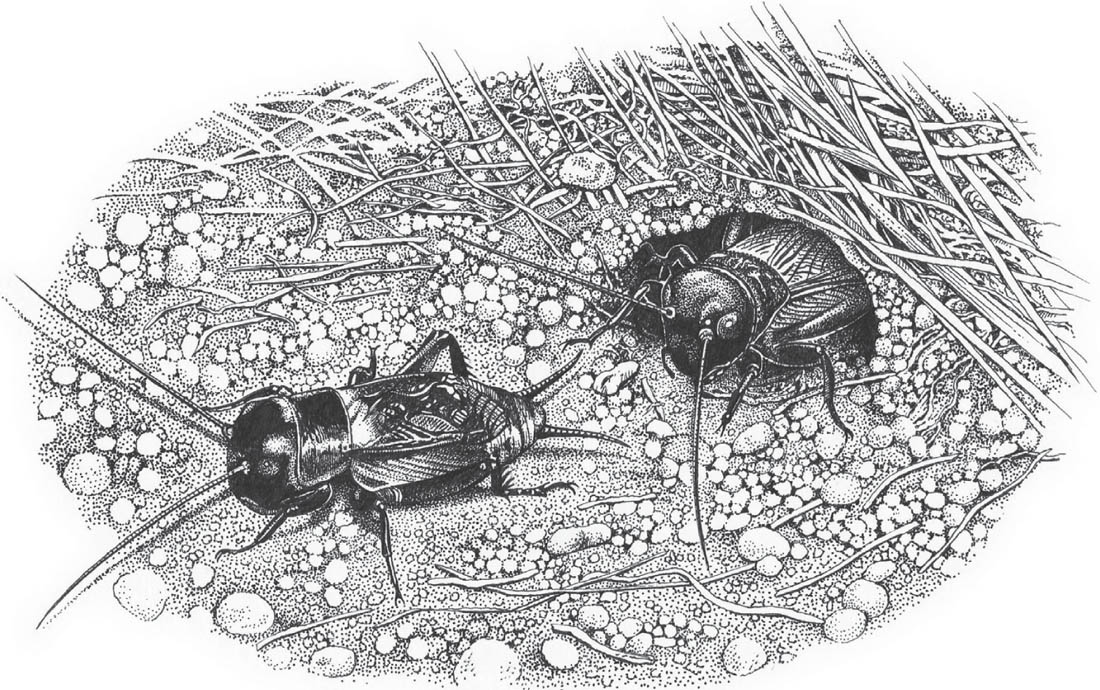

Behaviour

In captivity, females have been observed to lay their eggs in soil, some of them showing a preference for short turf over bare ground. During oviposition the female inserts her ovipositor vertically into the soil, apparently testing for suitability of the substrate. When a suitable site is found, she presses the ovipositor fully into the soil, and usually lays one egg quickly afterwards. Most frequently only one egg is laid in one session but sometimes a small batch is laid (up to 13 have been recorded). After the egg (or final egg in a batch) has been laid, the female raises and lowers her ovipositor to fill in the space above the eggs, and, after removing her ovipositor, scrapes the soil surface around the oviposition site, so concealing it. There is evidence that warmer sites are selected for oviposition.

The adults are bulky animals, apparently rather poor climbers, whose typical responses to disturbance are to remain still and rely on their excellent camouflage, or to jump out of the way – usually into deep grass tufts. When they do this they have the appearance of small, plump green frogs. They are omnivorous, feeding on both vegetation and other invertebrates, including beetles and grasshoppers (see DVD sequence).

The adults, while tending to favour the shelter of the dense grass tufts, will bask in sunshine on the warmer aspect of the tussocks. However, as the microclimate is cooler in the tufts than in the shorter turf, it seems likely that the association with this vegetation structure on the part of adults and late instars is related to avoidance of predation. The tufts are also used by the males as song perches. Unlike many other bush-crickets, they sing most in the early part of the day – from mid-morning to early afternoon, and only during warm weather. The song is usually delivered from a perch on a grass tussock, and takes the form of prolonged bursts of repeated high-pitched clicks. The rate of repetition increases to about 10 clicks per second within a minute or so of the start of the burst. The volume of the song is quite low, and for many observers a bat detector is needed to locate it at more than a few metres distance. Males are also reported to emit short isolated chirps.

FIG G. Head and pronotum of this female show signs of predator damage: possibly beak-markings of a bird.

Like most bush-crickets, the males produce a substantial spermatophore which includes a ‘nuptial gift’, the spermatophylax, which is bitten off and consumed by the female while sperm from the ampulla are transferred to her. In the wartbiter, literature sources give measurements of the mass of the spermatophore varying from approximately 6 per cent (Cherrill & Brown, 1990a) to 11 per cent of the body-weight of the male (Vahed & Gilbert, 1996).

Enemies

Cherrill & Brown (1992a) noted the presence at their study site of foraging foxes, badgers, kestrels, magpies, crows and starlings. The large size of the late instars and adults probably makes them an attractive food item for predators, and Cherrill (1997) found numbers of adults with severed legs, or hind femora, tibiae or ovipositors, and one female with a beak mark on her abdomen. Insects showing signs of past predator attacks were more common among adults and late instars.

However, mortality rates were shown to be much higher among the earlier nymphal instars, with population densities declining by 99.3 per cent from egg hatch to adult emergence, but remaining quite constant after that. Mortality arising from defective moulting between instars is known to be high, but various other causes including predation probably contributed to the high levels of pre-adult mortality (Cherrill & Brown, 1990a).

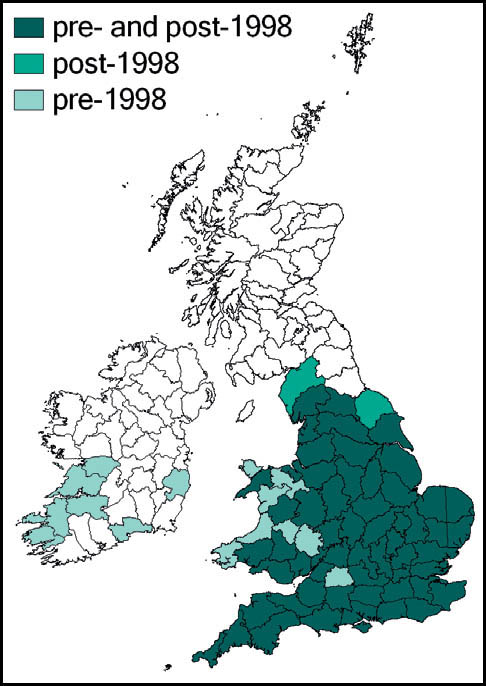

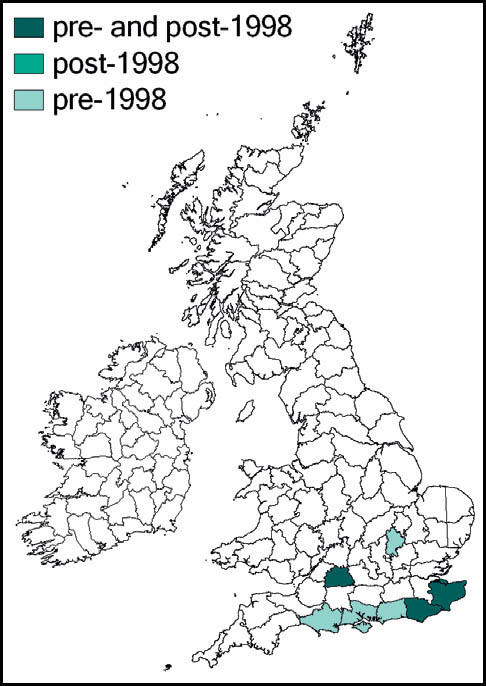

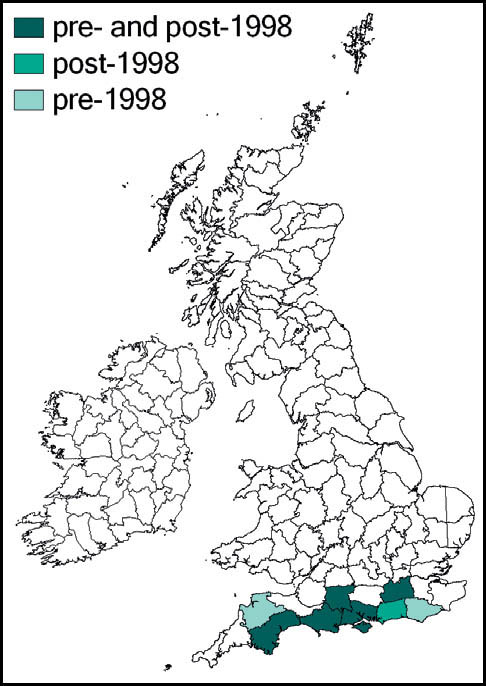

Distribution

The wartbiter is widely distributed in Europe and temperate Asia. As a species close to the northern edge of its range in Britain and northern Europe, it is especially vulnerable here to habitat change and inclement weather. There is evidence of decline in recent decades in the Netherlands, Belgium, Denmark and southern Sweden as well as in Britain.

In Britain it has always been a rare and highly localised species, confined to a few localities south of the Bristol Channel. These localites were in east Kent, Sussex, Hampshire (New Forest), the Isle of Wight, Dorset and Wiltshire. The majority of these populations have been lost as a result of urban development, agricultural change and changes in habitat management (in some cases enacted for conservation purposes!). Currently it is believed that the wartbiter is confined to no more than four of its original localities: two in east Sussex (including the largest, at Castle Hill National Nature Reserve), one on downland in Wiltshire, and the other a very small heathland population near Wareham. There is, however, at least one site, in Kent, where re-introduction of the species appears to have been successful.

Status and conservation

The wartbiter was scheduled in the Wildlife and Countryside Act, 1981, and included as ‘Vulnerable’ in the Nature Conservancy Council’s Red Data Books: 2. Insects (Shirt, 1987). It was the subject of a Nature Conservancy Council/English Nature Species Recovery programme from 1987, with substantial research conducted by Andrew Cherrill, Valerie Brown and colleagues (the main basis of the above account), together with captive breeding and attempts at reintroduction. The captive breeding programme proved very demanding for several reasons. The nymphs had to be reared in separate containers because of cannibalism, they suffered from protozoan and fungal infections, as well as a high frequency of failed moults, and they required high-quality food (Pearce-Kelly et al., 1998). The process was labour intensive, but produced enough late instars and adults for release into three sites, one of which, at least, still has a population of the species.

Adults of the British population are smaller than those from further south in Europe, and our populations are also much less dense. In Cherrill’s view (1993), the species is capable of high reproductive success in Britain only in years when weather conditions are particularly favourable. Even then, it is dependent on appropriate habitat management on its predominantly south-facing grassland sites. A complex sward structure, with tufts of coarse grasses interspersed on a fine scale with short turf and bare ground, appears to be an essential combination of requirements for wartbiters during their developmental stages, and for thermo-regulation, shelter from predators, song perches, oviposition, and mate location for the adults (see also Chapter 9).

References: Cherrill, 1993, 1997; Cherrill & Brown, 1990a, 1990b, 1991a, 1991b, 1992a, 1992b; Cherrill et al., 1991; Haes et al., 1990; Ingrisch, 1984a; Pearce-Kelly et al., 1998; Sutton, 2009; Sutton & Browne, 1992; Vahed & Gilbert, 1996.

THE DARK BUSH-CRICKET

Pholidoptera griseoaptera (De Geer, 1773)

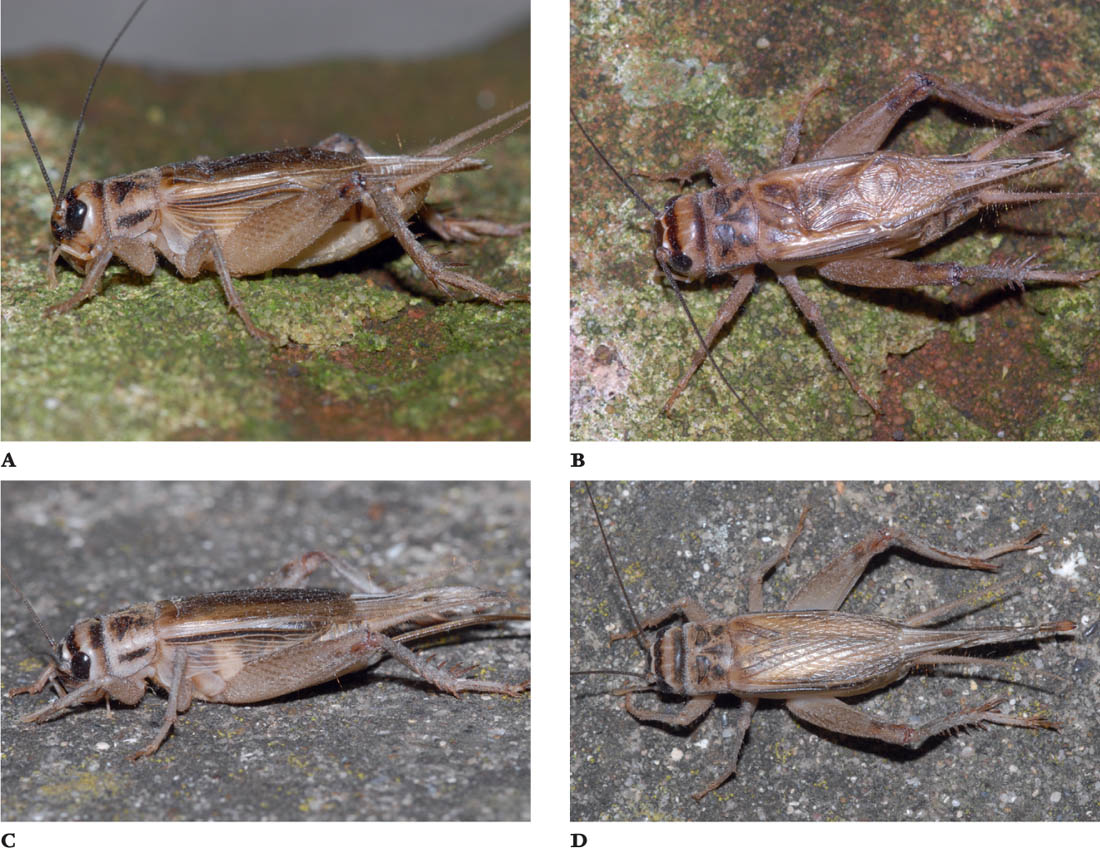

MEASUREMENTS: Male: 13–20 mm in length; female: 13–20 mm in length.

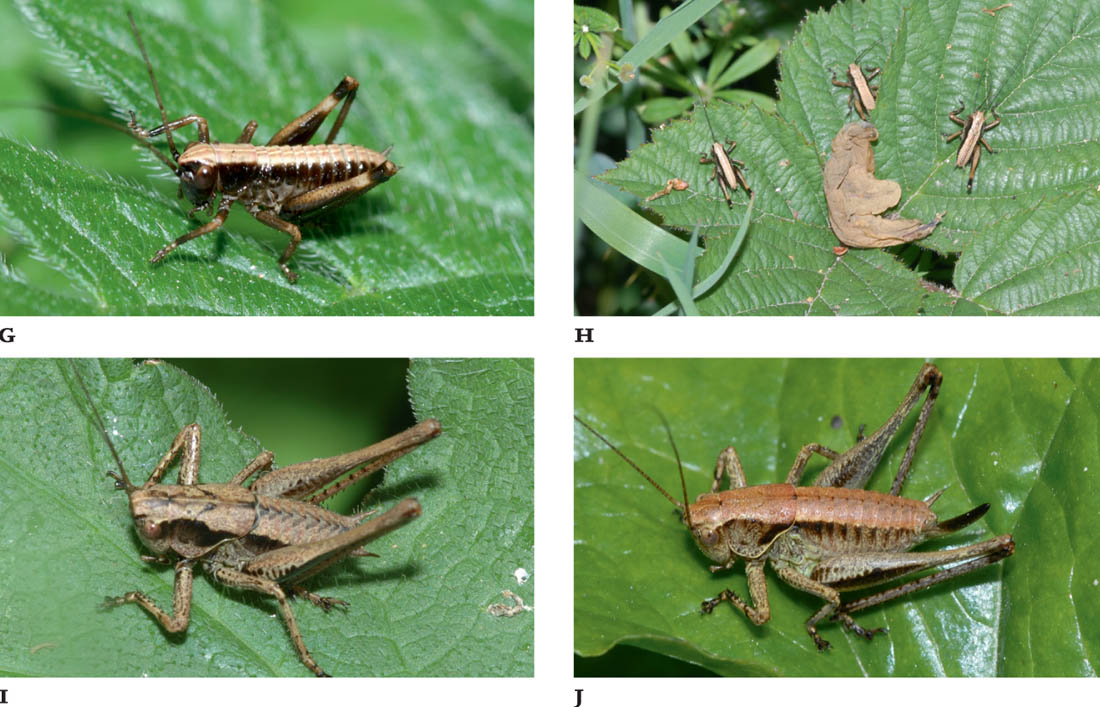

FIGS A–C. Male; female; male, dorsal view.

FIGS D–F. Grey form; chestnut form; underside.

Description

This species has a robust build. The dorsal surface of the pronotum is smoothly curved with a fine median longitudinal ridge that extends forwards on the head. The side flanges (‘paranota’) of the pronotum are continuous with the dorsal surface, but form a definite angle with it. The males have small inner projections near the base of their cerci. The ovipositor in the female is relatively long, broad, and up-curved. There are no hind wings, and the fore wings in the male are greatly reduced to function solely in stridulation. The wings in the female are even more vestigial, being reduced to tiny flaps just visible at the rear of the pronotum.

The ground colour varies from pale grey to grey-brown, with darker grey or brown fine flecks and indistinct markings. There are often darker patches of grey-black, especially on the sides of the pronotum and on the outer surface of the hind femora. One striking form has sandy or chestnut brown coloration on the dorsal surface of head, pronotum and abdomen, contrasting with the paler sides. The ovipositor is usually darker than the rest of the body, especially towards the tip. The underside of the abdomen is yellow to yellowish green.

Similar species

There are three other medium-sized bush-crickets that could be confused with P. griseoaptera.

Life cycle

The eggs are buff-coloured, 4 mm by 1 mm in size, and laid in crevices in bark or in rotting wood. They may hatch the following spring (in mid-to late April), but are more likely to over-winter twice, to give a two-year life cycle. There are six nymphal stages, with the tiny wing stubs of the males visible in the final two. The nymphs are more strikingly contrasting in their colour patterns than the adults. They are commonly pale brown with darker brown patterns and blotches, the latter frequently along the sides of abdomen and pronotum, and on the hind femora. They settle on exposed lower leaves of bramble and other shrubs on sunny days. The adults emerge from mid-July onwards, and survive later into the autumn and winter than most other species.

Habitat

Although sometimes found among tall grasses, they are rarely far from patches of low scrub, especially bramble clumps and rough hedgerows. They are apparently also found on exposed cliffs in the south-west (Marshall & Haes, 1988).

Behaviour

Like most other bush-crickets they are omnivorous and include other insects as well as small spiders in their diet. In captivity they will also consume earthworms (A. Kettle, pers. comm.).

They are mainly nocturnal, skulking among the branches of bramble scrub during the day. From mid-afternoon, especially late in the season, the females, especially, spend long periods basking in sun spots. They alternate their posture between exposing each side to the sun, with the hind leg facing the sun lowered to expose more of the abdomen, and exposing their dorsal surface to the sun, hind legs stretched out behind. Both sexes frequently run their antennae through their mouthparts, presumably to clean them, although it is also possible that this behaviour is linked to the ‘fencing’ with their antennae during courtship, and involves chemical communication. Active preening of the fore legs with the mouthparts is also frequent. In cloudy or even wet weather the males may begin singing quite early in the day. Usually, however, they are heard from mid-afternoon onwards, and continue through the night.

FIGS G–J. Early instar nymph; basking nymphs; late instar nymph, male; late instar nymph, female.

They are gregarious, and from mid-afternoon into the evening often gather in groups of a dozen or more within a square metre on lower leaves and branches of the bramble. The group may include four or more males, each chirping, with females gathering from inner branches of the scrub. Although the females approach singing males they do not, at this time, show any interest in mating. However, prolonged ‘fencing’ with their antennae is noticeable.

The ‘solo’ song of the male is a brief, high pitched chirp repeated at variable intervals of a few seconds. However, several males are often singing in close proximity to one another, and sometimes this results in a regular pattern of alternation between two adjacent males. When more than two males sing together, their chirps still are generally emitted separately to produce a non-synchronous ‘chorus’ (Jones, 1963, 1966). The males can also emit a more prolonged chirp lasting approximately a second. This is considered to signify an aggressive interaction between males, but it is also occasionally emitted by males on the approach of females. In general, males do not appear to interact aggressively with one another. However, experimental work does show that the onset, termination, and timing of chirps are all affected by the stridulation of other males (see Chapter 5).

Courtship involves prolonged ‘fencing’ with the antennae between a male and female pair at close proximity. Eventually the female mounts the male from the rear, actively palpating the dorsal segments of his abdomen, presumably imbibing a chemical secretion. The male raises his hind legs to allow the female to mount, but may still reject her at this stage by a powerful back-kick of the hind legs. Males who do this continue to chirp, indicating continuing readiness to mate (see DVD). This somewhat puzzling behaviour is explained by Gwynne (2001) in relation to the mormon cricket (Anabrus simplex) in terms of the ‘choosiness’ of the male in view of the cost to him involved in the ‘nuptial gift’. Apparently the males assess the weight of the females that mount them, accepting only the heaviest ones (presumably as these are most likely to lay more eggs). In the dark bush-cricket, the spermatophore weighs some 10.7 per cent of the male body weight (Vahed & Gilbert, 1996).

Enemies

They can be caught in the webs of larger spiders, most notably the wasp spider (Argiope bruennichi).

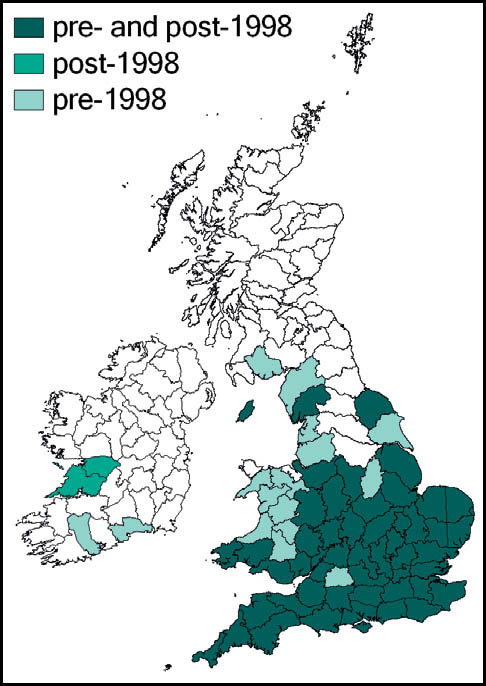

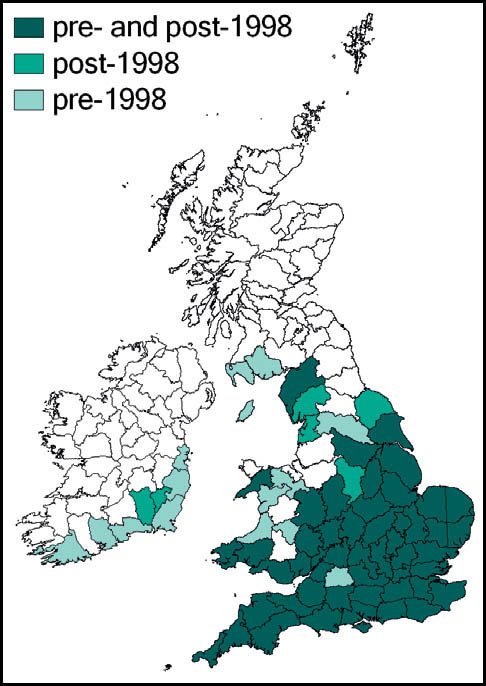

Distribution

The dark bush-cricket is widely distributed and generally common throughout most of Europe. In southern Britain it is perhaps our commonest bush-cricket, and has been recorded in almost every 10 km square south of a line from south-west Wales to the Wash. North of this, its known distribution is more scattered, but reaches as far north as north Yorkshire and south-west Scotland. It is also known from the south and west of Ireland.

Status and conservation

The dark bush-cricket remains common within its geographical range and thrives on small, neglected patches of habitat. Its only serious threat seems to be excessive tidy-mindedness that might disrupt that neglect.

References: Gwynne, 2001; Jones, 1963, 1966; Hartley, 1967; Vahed & Gilbert, 1996.

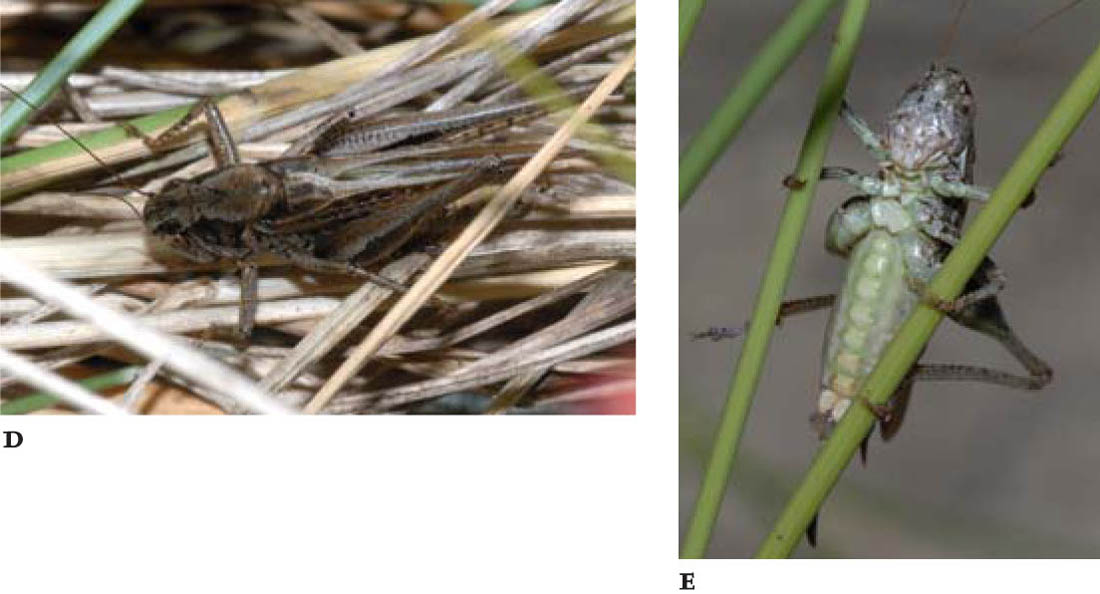

THE GREY BUSH-CRICKET

Platycleis albopunctata (Goeze, 1778)

MEASUREMENTS: Male: 20–25 mm in length; female: 20–28 mm in length.

FIGS A–C. Male; female; dorsal view, male.

Description

The grey bush-cricket is sturdily built and medium sized. It is fully winged, with the wings extending back to a few millimetres beyond the tip of the abdomen. In the males, the anterior part of the leading edge of each fore wing is modified for stridulation. The male cerci have inwardly directed spines about halfway along.

The ovipositor of the female is broad, up-turned and black in fully mature specimens. In both sexes there is a slight median ridge on the rear part of the dorsal surface of the pronotum, which divides, with the front end forming a ‘y’ shape. The adults vary from grey to light brown in ground colour, with fine blackish flecks that coalesce into patches in places, especially the sides of the pronotum (paranota). The paranota have pale borders, but these are obscured by darker flecks in adults. The outer surfaces of the hind femora frequently have a black ‘fish-bone’ marking. The underside is usually a very pale green or yellow. A form with green rather than grey or brown coloration of the pronotum is reported (e.g. Ragge, 1965), and the subspecies (jerseyana) that occurs in the Channel Islands often has more greenish coloration (Evans & Edmondson, 2007).

Similar species

There are three similar species.

In Britain the grey bush-cricket is mainly found in coastal sites, and not usually in association with any of the above (although occasionally with M. roeselii (B. Pinchen, pers. comm.). The song of the male is also distinctive.

Life cycle

The eggs are laid singly or in small batches by the female in sand or soil, or sometimes in plant stems or crevices. They hatch in April or May, and there are six nymphal instars. The nymphs are brown, or green with brown head and pronotum. They have pale cream-yellow borders to the paranota, and variable black markings. The up-turned wing stubs are noticeable in the final two nymphal instars. Adults emerge from early July onwards, but do not usually survive much beyond the end of September or early October.

Habitat

In mainland Europe the grey bush-cricket inhabits rough grassland, but in Britain it can be found in a variety of coastal habitats such as among marram grass (Ammophila arenaria) tussocks on sand dunes, on grassy fringes of coastal cliffs, on stabilised shingle and among low scrub. Patches of loose soil or sand, interspersed with dense, low vegetative cover exposed to the sun seem to be characteristic of all habitat types.

Behaviour

The adults are very secretive, and sensitive to disturbance (a colleague remarked they should be re-named ‘the shy bush-cricket’). They are active mainly in the warmer part of the day, and the patient observer can sometimes see them basking in sunny weather on taller vegetation, such as shrubby seablite (Suaeda vera) or sea purslane (Halimione portulacoides), and even on driftwood. Even here, however, they are never far from cover, and quickly descend into the depths of the vegetation if they detect the slightest movement. If alarmed when this is not a feasible option, they are effective in jumping and flying for the nearest cover. They are omnivorous, including other insects such as grasshopper nymphs in their diet, but, according to Ragge (1965), can be kept successfully in captivity on vegetable matter. In sand-dune habitats they feed on marram grass, often selecting desiccated stems. One was observed by the author lunging at a gatekeeper butterfly that settled some 5 cm away from it!

The males usually sing from cover and are very difficult to locate, even with the aid of a bat detector. The song consists of a brief chirp, repeated at a rate of 2 to 4 times per second, and continued in prolonged bursts lasting several minutes. The sound is rather quiet, and often obscured by the sound of the wind in its exposed habitat. However, when picked up with the aid of a bat detector it is quite distinctive. Males do not congregate, as males of the dark bush-cricket do, but ‘duets’ can often be heard when the song of one male interacts with that of another. However, in laboratory experiments such alternating duets have been shown to break down after some time, and the interaction may simply function to enable the males to space themselves out across the available habitat (Latimer, 1981a, 1981b). There is some evidence of at least temporary territoriality among the males, as there are brief skirmishes when they encounter one another (see DVD). The male delivers a spermatophore to the female on mating. This is given as approximately 5.5 per cent of the male’s body weight (Vahed & Gilbert, 1996).

FIGS D–E. Singing male with ‘mirror’ partly exposed; underside of female with remains of spermatophore visible.

The females are more frequently found than the males away from deep cover on patches of unvegetated soil or sand, presumably seeking oviposition sites.

Enemies

None is reported in the literature, but their habit of retreating into cover suggests adaptation to avoid diurnal visual predators – possibly birds (such as ringed plover, dunlin, turnstone or kestrel) or mammals.

Distribution

This species is widespread in southern, south-western and central Europe, as well as north Africa. In Britain it is at the northern edge of its range, and this may explain its rather specialised coastal and southerly distribution. Its distribution is almost continuous along the south coasts of England and Wales, and the southwest peninsula, with outliers further north along the east coast to Suffolk and, on the west, to north Wales. There is a small scattering of inland and more northerly reports. A site 14 km inland was reported from Ringwood, Hampshire (Widgery, 1998, 2001a) in the 1990s, but extension of an adjacent industrial estate may have been the cause of its subsequent demise (B. Pinchen, pers. corr.).

Status and conservation

The main threat to the grey bush-cricket is development for housing or tourism on its coastal habitats. On the east coast, in Essex and Suffolk, it is found in a small number of sand dune systems where it had been supposed extinct. Recent survey work suggests that it is currently increasing, and further colonisations along the east coast seem likely (Harvey et al., 2005; Gardiner et al., 2010). This might be aided by climate change, but coastal erosion might offset any such gains.

References: Evans & Edmondson, 2007; Harvey et al., 2005; Gardiner et al., 2010; Latimer, 1981a, 1981b; Ragge, 1965; Vahed & Gilbert, 1996; Widgery, 1998, 2001a.

ROESEI’S BUSH-CRICKET

Metrioptera roeselii (Hagenbach, 1822)

MEASUREMENTS: Male: 13–22 mm in length; female: 14–22 mm in length.

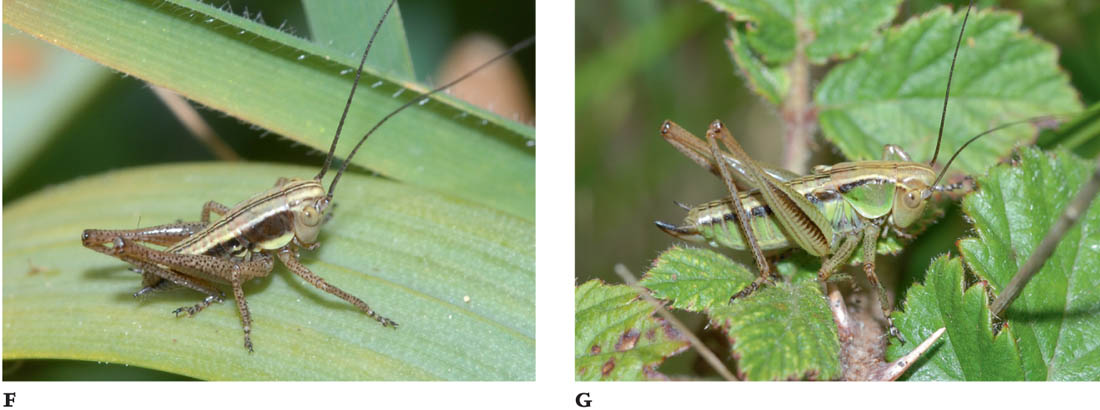

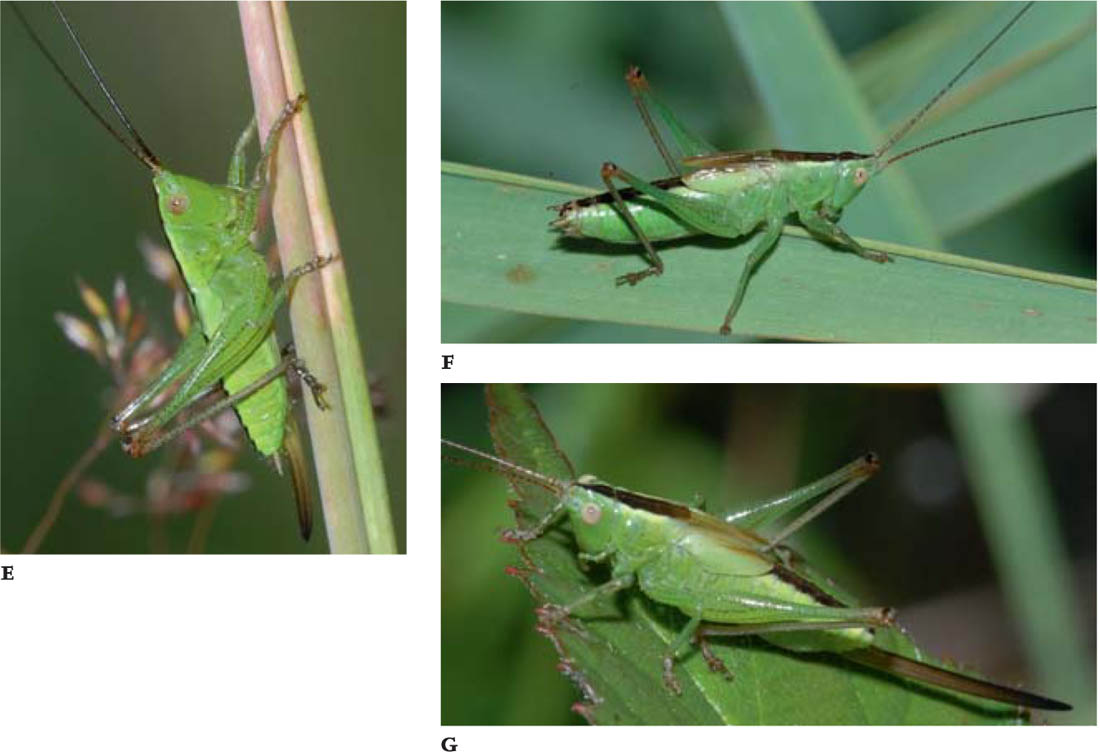

FIGS A–D. Male; female; green female; male, dorsal view.

FIG E. The macropterous f. diluta, male.

Description

Roesel’s bush-cricket is a medium-sized, sturdily built insect, in which the wings are typically only part-developed – reaching back over only the first five or six abdominal segments in the male, fewer in the female. The fore wing stubs of the male are partially modified for stridulation, and the long cerci have an inner projection halfway along. The ovipositor is broad and up-turned, brown shading to black-brown towards the tip. There is a continuous fine median ridge on the dorsal surface (discus) of the pronotum, usually continued forward as a yellowish line over the head.

A minority of individuals of both sexes in most populations are of the long-winged (macropterous) form (f. diluta). Although the wing tips in this form soon become tattered, it is usually possible to see that the wings are very long – sometimes extending beyond the tip of the abdomen by as much as one third to a half of the total wing length.

The ground colour is usually grey-brown with darker markings. There is often a fish-bone-shaped darker pattern on the outer surface of the rear femora, and the side flaps (paranota) of the pronotum are usually black, with a continuous cream-yellow border. The sides of the visible thoracic segments to the rear of the pronotum also have yellow patches. The underside of the abdomen is yellow.

A variable proportion of most populations have pale green sides and hind femora. In this form, the paranota are often greenish, with pale green borders.

Similar species

The pale yellowish (or greenish) borders to the paranota are distinctive. In the bog bush-cricket (M. brachyptera), the pale borders are limited to the rear edges only, and usually buff-cream in colour. The bog bush-cricket also lacks the yellow patches on the sides of the thoracic segments, and the ovipositor of the female bog bush-cricket is relatively longer, and less strongly up-curved.

For distinctions between Roesel’s and the dark and grey bush-crickets (P. griseoaptera and P. albopunctata), see the accounts of those species.

Life cycle

The female lays her eggs singly, in stems of coarse grasses or rushes. She bites a hole in the outer layers of the plant with her mandibles and raises her ovipositor under her abdomen to insert the tip into the cavity. The rest of the ovipositor is then pressed into the stem and she remains quiescent for some minutes while a single egg is placed in the plant tissue, parallel to the sides of the stem (see DVD). The egg is elongated, cylindrical and approximately 4 mm by 0.5 mm. Eggs laid early in the season may undergo sufficient embryonic development to hatch the following spring, while late-laid eggs pass two winters before hatching. The newly hatched nymphs appear in late May or early June, and pass through six nymphal instars before becoming adult from late June (Widgery, 2001b) or early July onwards. Adults and late instar nymphs can be found together through most of July. The adults persist until the end of September, and in declining numbers thereafter, until the end of October in most years.

FIGS F–G. Early instar nymph; and final instar green nymph, female.

The nymphs are usually pale brown, with a broad black band along each side of the abdomen, continued onto the paranota, with the pale border of the latter often more extensive than in the adults. A median black line runs along the whole dorsal surface of the insect, bordering the fine median ridge of the pronotum. The antennae are black. As in the adults, there is a form of the nymph with green sides, shading to brown dorsally. Up-turned wing stubs can be seen in the final two instars (see also Chapter 3, Fig 66).

Habitat

This is a species of open grassland with tall grasses. Although common on large expanses of grassland, such as south-facing downland and coastal grazing marshes, it is quite capable of surviving in small neglected field corners or roadside verges. It is common on sea walls and inner ‘foldings’, and is one of the few species to thrive in narrow conservation strips of coarse grasses at the edges of arable fields. However, it also occurs in overgrown and unmanaged sites, where there is succession to scrub, as well as along south-facing hedgerows, woodland edges and open woodland rides.

Behaviour

Roesel’s bush-cricket is a sun-loving species, the females, especially, spending much of their time basking. They are omnivorous but feed mainly on vegetable matter, particularly grasses.

On sunny days the males sing in prolonged continuous bursts. Although the song is high-pitched, like that of most bush-crickets, it can be heard by most people as a distinctive ‘buzz’. In most extensive grassland habitats the males are evenly spaced out, and sing from perches. These are usually exposed to the sun, but not conspicuous as they are surrounded by rank vegetation. However, there is some competition between males for song perches. Where wind or rain has broken clusters of grass stems to form a rough ‘platform’, three or more males may compete to occupy the perch, often emitting short bursts of song as they move about, and briefly skirmishing on contact. Clusters of both males and females may sometimes be seen on leaves of low scrub such as oak saplings or bramble.

At close quarters, courting males approach females, ‘fencing’ with their antennae, and continuing to emit bursts of stridulation (see DVD).

Long-winged forms appear to behave in similar ways to the typical one, but they are noticeably less mobile among the long grasses. The stridulation of the male seems to be unaffected by wing length. However, the long-winged form, even where it is relatively common, soon declines as a proportion of the population. This may be simply because, as the dispersive form, they emigrate to colonise other suitable habitat. One remarkable description of this refers to many macropterous Roesel’s bush-crickets taking to the wing in one field, the flight characterised as ‘ponderous and straight, with no apparent means of steering to left or right – the legs protruding behind their bodies like twin tails’ (Smith, 2007).

FIGS H–I. Singing male with raised fore wings; and courtship. Note the open wings of the singing male.

Clearly the macropterous form of roeselii is not a skillful flier, and as well as its disadvantage of lower mobility in tall vegetation, is also rendered vulnerable to predation when on the wing. There is believed to be a trade-off between the dispersal ability of the long-winged form and its lower fecundity, compared with the more usual short-winged form (see Chapter 3).

Enemies

The simultaneous flight of numerous long-winged individuals described above was sufficient to attract the interest of avian predators – in the shape of two pairs of hobbys and another pair of kestrels. The kestrels, feeding lower down, could be seen plucking the crickets out of the air, partially dismembering them and swallowing the remainder. After feasting for about an hour, the raptors were joined by approximately sixty black-headed gulls and one common gull, which also could be seen catching flying bush-crickets.

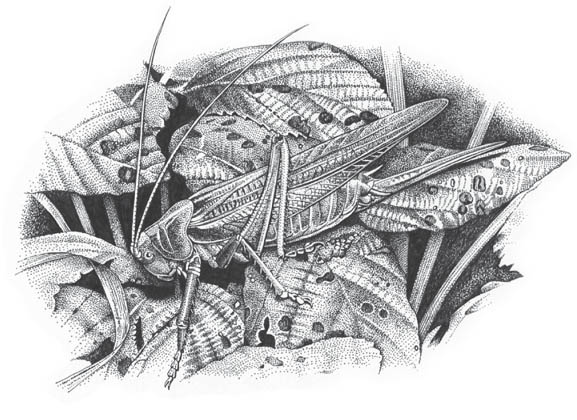

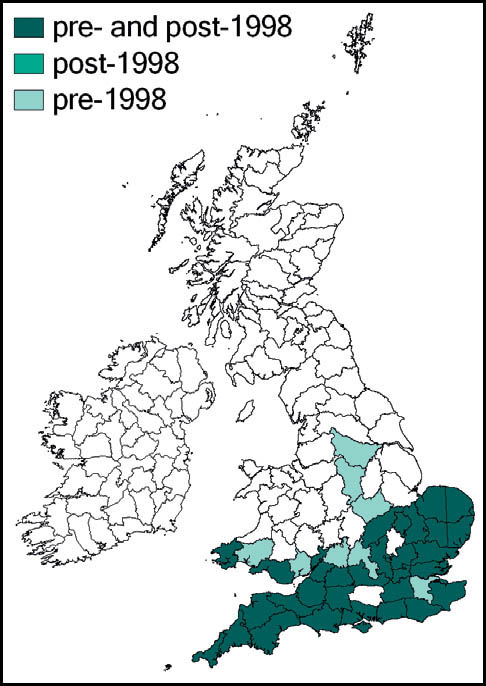

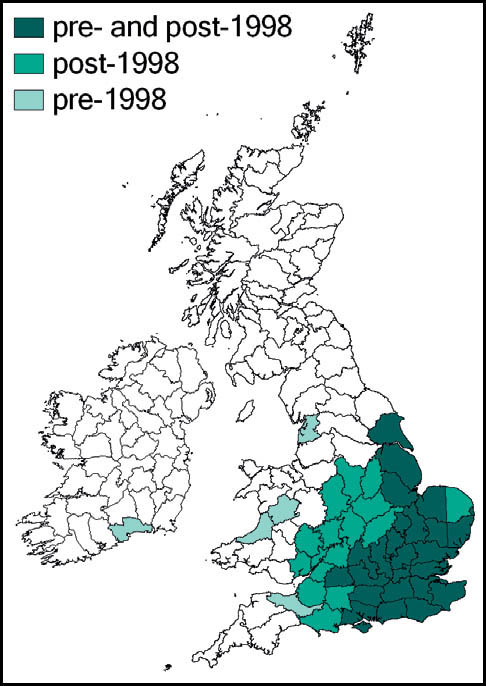

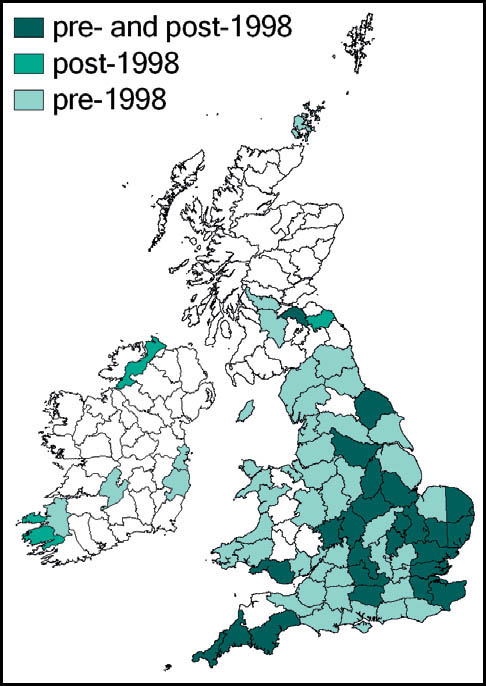

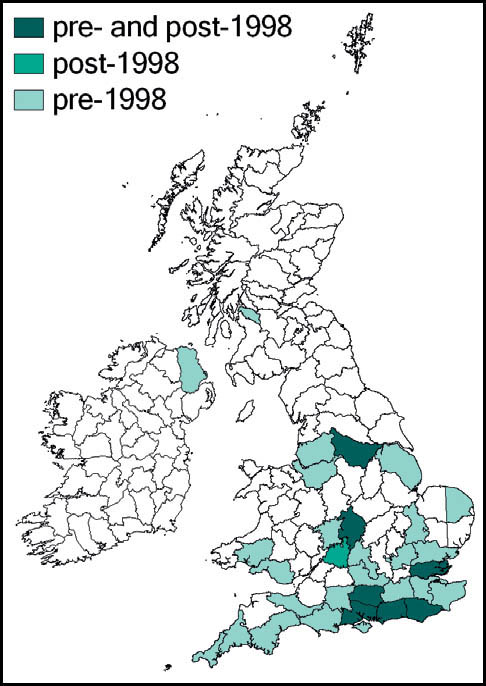

History

Stephens recorded it from Hampstead in 1835, but until the beginning of the 20th century it had been recorded only from east coastal areas from Kent northwards to the Humber estuary (Marshall, 1974). Burr (1936) considered it to be restricted to the east coast – from Herne Bay, Kent in the south to the Humber estuary in the north. He had records from Kent, Essex, Lincoln and Yorkshire, with a ‘doubtful suggestion’ from Cambridgeshire. Pickard (1954) adds Hampshire, Surrey, and coastal areas of Suffolk. According to Ragge (1965) its ‘liking for flat, estuarine localities’ limited it to the areas around the Solent, Thames and Humber, with other records from south Suffolk, Cambridgeshire and Surrey. The reports from Kent and Surrey included downland localities, indicating that earlier assumptions associating it solely with low-lying damp grassland were perhaps too restrictive. It was discovered in West Wales in 1970 (Ragge, 1973), and subsequently in south-east Ireland.

Marshall & Haes (1988) argue that the species is probably a late arrival in Britain from Dogger Land in the North Sea, before that area’s submergence, with the Thames estuary as the centre of its distribution in this country. They note its recent rapid range expansion, aided by the macropterous form – reported in exceptional numbers in London during the warm summers of 1983 and 1984. There is evidence that hot weather between April and July leads to accelerated nymphal development and earlier sightings of macropterous forms (Gardiner, 2009b; see also Chapter 2).

The expansion of range detected during the 1980s has continued apace. Widgery (2001b) reported many new records for 1998–2000 from Norfolk, Suffolk, Hampshire, Wiltshire (K. Rylands), Sussex (R. Becker) and Isle of Wight (B. Pinchen). In 2001 there were new reports from Hertfordshire, Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire, with evidence that at least some of these represented new colonisation. Subsequent new county records include:

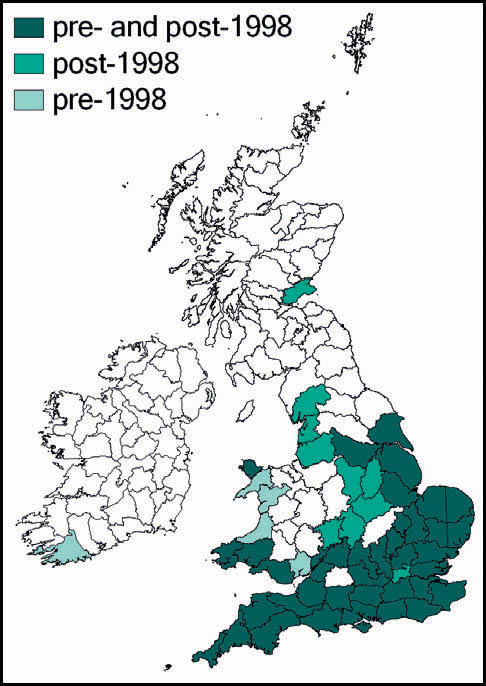

Distribution

This species is widespread in Europe, except for the south. In Britain and southern Scandinavia it is close to the northern limit of its range. However, it continues to extend its range in Britain from the south and eastern coastal areas and is now common and widespread to the south and east of a line from the Bristol Channel to the Wash, and a more scattered distribution west to north Somerset, and north to Lancashire and Yorkshire. It is present in a restricted area of west Wales, and also in the south of Ireland.

Status and conservation

It seems likely that the recent range extension of Roesel’s bush-cricket will be continued, and aided in the longer term by climate change. Its long-grass habitats are likely to be a persistent, if marginal, feature of the farmed landscape, as well as of neglected and relatively lightly managed land such as roadside verges, flood defences and railway embankments. Agricultural set-aside and subsequently grant-aided stewardship schemes have no doubt favoured its range extension, and continue to provide both breeding habitat and, probably, connectivity between subpopulations (Simmons & Thomas, 2004; Gardiner, 2009b).

References: Gardiner, 2009b; Marshall & Haes, 1988; Simmons & Thomas, 2004; Smith, 2007; Sutton, 2005b, 2007b, 2008a, 2010a; Widgery, 2001b.

THE BOG BUSH-CRICKET

Metrioptera brachyptera (Linnaeus, 1761)

MEASUREMENTS: Male: 11–18 mm in length; female: 13–21 mm in length.

FIGS A–D. Green male; green female; brown female; male, dorsal view.

FIG E. The rare macropterous form, f. marginata (© P. Sutton).

Description

This medium-sized bush-cricket is quite similar in appearance to its relative, Roesel’s bush-cricket. In the typical form the hind wings are almost absent, while the fore wings are reduced to short stubs, reaching back only as far as the third or fourth abdominal segment. In the male the fore wings (tegmina) are modified for stridulation. There is a fine median longitudinal ridge along the pronotum. The male cerci have a black inward-pointing spine about halfway along. The ovipositor ofthe female is relatively long, and gently up-curved.

There are two basic colour forms, both of which occur quite frequently in British populations. One form has a brown ground colour, with dark brown-black markings. These are generally very fine speckles as well as larger patches of blackish coloration on the sides of the head, pronotum and the abdominal segments. There is often a fine pale line through the black around the eye, leading back to the front edge of the pronotum, and there are usually black stripes along the sides of the hind femora. The ovipositor is blackish for most of its length, but paler towards the base. The underside of the abdomen, and, often, the ventral surface of the hind femora, are green.

The other colour form is similar, except that the dorsal surface of the head and pronotum, and both leading and hind edges of the tegmina, are bright green.

In all forms, the paranota (side flaps of the pronotum) have a pale buff or cream-coloured hind margin.

There is a rare macropterous form (f. marginata (Thunberg)) in which both pairs of wings are fully developed (Ragge, 1973).

Similar species

Roesel’s bush-cricket has the pale border to the paranota running round the lower and fore margins, but in the bog bush-cricket it is confined to the rear margin. The ovipositor of the bog bush-cricket is longer relative to its body and more gently up-curved than that of Roesel’s bush-cricket. The subgenital plate of the female is deeply notched in the latter species, but only very shallowly so in the female bog bush-cricket (see the Key, Figs K8a and b). These species do occur together, so it is important for recorders to have clear identifying characters.

FIG F. Final instar male nymph.

The dark bush-cricket is superficially very similar, especially to the brown form of the bog bush-cricket. However, the wings of the dark bush-cricket are much more drastically reduced than those of the bog bush-cricket – being virtually absent in females and reduced to the stridulatory apparatus in the males.

The grey bush-cricket is fully winged and so quite different in appearance to the typical form of the bog bush-cricket.

Life cycle

The eggs are probably laid in the stems of plants during the summer, and are thought to overwinter twice before hatching in May or early June. The resulting nymphs pass through six instars before completing their development during July or early August. The adults can be found through August and September, becoming more scarce through October, and sometimes surviving into November.

The up-turned wing stubs are just visible in the fifth instar nymphs, and more clearly so in the final instar. The nymphs are always brown in ground colour, and darker-brown to blackish on the paranota and sides of the abdomen. As in the adults, there is a pale rear border to the paranota.

Habitat

The bog bush-cricket, as its name implies, is an inhabitant of the wetter parts of heaths and moors, usually at low altitudes. It is associated in these habitats with tall, dense tufts of vegetation such as cross-leaved heath (Erica tetralix) and other heathers, bog myrtle (Myrica gale) and grasses such as purple moor-grass (Molinia caerulea). In the wet heaths of Dorset and the New Forest it is often found together with the large marsh grasshopper (Stethophyma grossum).

Behaviour

The adults feed on seed heads of heathers and grasses, and probably also on other invertebrates. They make good use of the shelter provided by the grass tufts and low shrubs they inhabit, the males usually singing from cover. When they bask on outer branches or leaves they are easily alarmed by a careless approach and disappear down into the depths of the vegetation. A patient (and often waterlogged!) wait will sometimes be rewarded by their reappearance, and the males do sometimes sing while moving around over more exposed patches of scrub (see DVD).

The males sing through the day, and will often sing in overcast conditions. Their song is a short chirp, repeated at a variable rate of 2 to 6 chirps per second. It is rather quiet, and for many people a bat detector is the best way of locating the males.

Distribution