2 Consumption of Luxuries: The Glass and Copper Alloy Vessels

A number of ostentatious items from the site suggest conspicuous consumption; most of these fall into the categories of fine tableware or display items, in a variety of materials. A range of fine glass vessels include examples of palm cups, a funnel-beaker, a possible claw beaker, and some globular beakers and bowls. The copper alloy vessels are fragmentary, but include part of a hanging bowl; more utilitarian forms include a cauldron, and some possible bowls and long-handled skillets; metal vessels, in general are likely to be under-represented in the archaeological record from the site, because of the practice of recycling worn or broken vessels. Lastly, a number of mounts from the site may have adorned leather belts or small boxes; one more elaborate mount, incorporating animal heads and interlace, may have been part of a leather bag or satchel.

***

2.1 Glass vessels

by Vera I. Evison

Apart from window glass, the total number of Anglo-Saxon glass fragments retrieved from the site is 73, of which 69 are from vessels, and four consist of a bead, a tessera and melted waste. The fragments are mostly small, with the maximum length ranging from 6mm to 50mm (cf. PL. 2.1). Indications of some original Anglo-Saxon forms may be deduced from rim and base fragments, and some from wall fragments with features, and there are also a number of featureless fragments which are in corresponding colours. Particularly distinctive are several wall fragments decorated with applied bicolour twisted trails or reticella.

None of the fragments appears to belong to the early Anglo-Saxon period, AD 400–700. A rim fragment, no. 880 (RF 2048; FIG. 2.1) deeply outfolded, however, continues the palm cup form current in the 7th century (Evison 2000a, fig. 3.9, fig. 4.2), but the vivid blue-green colour was not in use before the 8th century. The small fragment no. 886 (RF 10583) in the same colour could have belonged to the same rim.

The number of forms of drinking vessels in use in the period AD 700–900 is limited, the majority being unstable forms of the palm cup which developed into the funnel beaker, together with some globular beakers and bowls (Evison 2000a, fig. 4, III). As the funnel beaker forms emerged there were changes in the rim, which were sometimes folded inwards, or only slightly thickened and cupped.

Item no. 889 (RF 13505; FIG. 2.1), a light green-blue rim folded inwards with a tubular hollow, has a diameter of c.100mm and so falls in the funnel beaker series (Evison 2000a, 4.III, 3; cf. at Hamwic, Hunter and Heyworth 1998, fig. 5, 36/326). Fragment no. 884 (RF 5469), a light green-blue rim thickened by rolling inwards is also a funnel beaker. The curved base of a tall palm cup (Evison 2000a, fig. 4.III, 3) is represented by five joining fragments, the light green no. 890 (RF 5521; FIG. 2.1), and there is a second possible base fragment of this type, no. 891 (RF 6020), again light green (cf. Hamwic, Hunter and Heyworth 1998, fig. 11, 24.426).

Fragment no. 887 (RF 11018; FIG. 2.1) is a small part of a brown, infolded rim, heat-damaged, with horizontal white trails; and this contrasting colour decoration occurs mostly on globular beakers (Evison 2000a, fig. 4.III, 6). The rim no. 879 (RF 1281; FIG. 2.1) also infolded, is blue with horizontal yellow trails up to the edge of the rim. This unusual colour and pattern combination is to be seen on the ‘inkwell’ fragment from Hamwic (Hunter and Heyworth 1998, fig. 13, 24/510 and pl. 5). The simple rim no. 885 (RF 7247; FIG. 2.1), is light blue-green with yellow trails, has a diameter of approximately 80mm, and is probably from a globular beaker. Catalogue no. 888 (RF 11523; FIG. 2.1), light blue-green in colour, is misshapen and the form is not identifiable. Fragment no. 882 (RF 3543) is a rim to a conical form, possibly a funnel beaker (cf. Hunter and Heyworth 1998, fig. 8, 26/540; fig. 10, 36/333).

FIG. 2.1. Glass vessels. Scale 1:1.

Vessel fragment no. 883 (RF 5000; FIG. 2.1; PL. 2.2) is a very distinctive rim. A yellow trail was wound horizontally on a colourless wall right to the edge of the rim, after which the rim was deeply folded outwards, leaving a hollow with the trails remaining visible on the inside of the fold. The estimated diameter is 140mm, and the vessel is the type of bowl found in grave 6 at Valsgärde, Sweden (Evison 2000a, fig. 4.III, 1; pl. V, 1). Rim fragments of this type occur at a number of other sites on the Continent and in England (Evison 1988, 240–1; Evison 1991, 92, 67s; Evison 2000a, fig. 7). The lower part of this type of bowl is similar to the lower part of a contemporary globular beaker form, as both can be decorated with simple horizontal trails of a contrasting colour at the top (usually yellow, or less frequently white), and with reticella trails on the lower part of the vessel, usually in a vertical direction (Evison 2000a, fig. 4. III, 6; pl. V, c). Bowls of this type from Valsgärde and Birka, in Sweden, and Dorestad, in the Netherlands, have been illustrated (Baumgartner and Krueger 1988, 70–1, nos 12–14). Comparable wall fragments of similar bowls are noted amongst the reticella fragments below.

There are ten wall fragments in all which are decorated with reticella trails. Number 898 (RF 5874; FIG. 2.2) is colourless and the yellow twisted trails are placed close together horizontally and marvered, with one trail unmarvered in a near-vertical position. This must have belonged to the same type of bowl as the rim no. 883 (RF 5000; FIG. 2.1), and is possibly from the same vessel. The angle of the unmarvered trail suggests that the pattern on the lower part of the vessel was similar to that shown more clearly on the light green-blue fragments below – nos 896–7 and 901–2 (RFs 1991, 5348, 6895 and 7012).

Items nos 896–7 and 901–2 (RFs 1991, 5348, 6895 and 7012; FIG. 2.2; PL. 2.5) are all very light green-blue fragments which have a band of six closely placed horizontal reticella trails, placed in the same order of S- and Z twist, although there is only enough of no. 897 (RF 5348) to show the lowest two trails in the same order. The arrangement of yellow horizontal trails above this band appears on three of the fragments. On no. 897 (RF 5348) there are crossing unmarvered trails below, and such diagonal trails also appear on nos 896 and 901 (RFs 1991 and 6895). It is, therefore, possible that all belong to the same bowl (FIG. 2.4, for reconstruction), although the glass of no. 897 (RF 5348) is in better condition than the others. As noted above, the colourless vessel no. 898 (RF 5874) probably also had diagonal trails. The unmarvered trails on the lower part of such vessels are usually applied singly and in a vertical position, as on the Valsgärde 6 bowl. However, one other vessel with diagonal crossing trails occurs at Ipswich, St. Stephen’s Lane, in similar colouring, where a bowl base fragment in light green-blue glass (3104/185 Suffolk County Council) is decorated with yellow reticella trails crossing each other in an irregular pattern.

Fragment no. 895 (RF 1857; FIG. 2.2) is a distinctive dark green colour with a single, unmarvered yellow reticella trail, probably vertical. The yellow thread has spread sideways, giving a dotted effect, the result of an unmarvered yellow trail twisted on a dark ?green rod (cf. Evison 1988, 243, fig. 12,5).

Catalogue no. 900 (RF 6887; FIG. 2.2; PL. 2.5) is part of the kicked base of a globular beaker, light green-blue with red streaks. The unmarvered reticella trail is one of a number which would have radiated from the centre of the base to continue vertically up the vessel wall. This trail consists of a black rod with unmarvered yellow trail which spread sideways on application. Other red-streaked globular beakers and bowls with such trails have been found at Dorestad (Baumgartner and Krueger 1988, nos 12–16). Red streaking in glass occurred frequently in the Carolingian period (Evison 1990), but the colour combination of black and yellow reticella is unusual.

The reticella trail no. 894 (RF 634; FIG. 2.2) has a white thread, and is applied in the shape of a near right-angle on a light blue-green vessel. As the wall thickness of this fragment varies from 1.5 to 3mm, this is probably part of the base of a globular beaker at the point where a vertical trail taken down the wall was turned at an angle to continue upwards. Catalogue no. 899 (RF 6398; FIG. 2.2) is from a vessel of more distinctive colour, a light but vivid green-blue, and the unmarvered reticella trail consists of a yellow thread on the same colour. The yellow has spread sideways to a considerable extent. The very small fragment no. 903 (RF 11138; FIG. 2.2) also has unusual colouring, and it can be seen that on a probably colourless base, it is the end part of a yellow, unmarvered reticella trail, on a light blue translucent rod.

In this assemblage, therefore, there are fragments of at least seven different vessels decorated with reticella trails. The forms, colours and patterns are basically consistent, but variety is achieved through different combinations of vessel colours and trails.

The vivid green-blue fragments nos 892–3 (RFs 8717 and 8723; FIG. 2.2; PL. 2.4) are both from the same context and are remarkable as to colour and form. They are both a shallow dish shape with a slightly thickened rim, and there is a fine red streak inside the rim no 893 (RF 8717), and a wider one in the same position on no. 892 (RF 8723). The other side is decorated with thirteen turns of a white unmarvered trail containing a fine red thread. The spacing of these trails corresponds closely on both fragments, so that there is no doubt they were part of the same vessel. The diameter is approximately 100mm, appropriate to the foot of a vessel with the applied trails on top, and there is a broken edge in the centre where it was broken away from the body of the vessel.

The only vessel types with a foot known in the early Anglo-Saxon period were the rare, imported stemmed beaker and the more frequent claw beaker. On the latter form, the foot was usually formed in one piece with the paraison by folding, and its diameter was often too small to afford stability to the vessel. One unique claw beaker, however, has a separate applied foot, 100mm in diameter, but this is the beaker of the 5th century from Mucking, Essex, grave 843 (Evison 1982, fig. 9a, pl. IVa). Three other foot fragments survive from contexts in England dating from post-AD 700, but they were all formed by folding. One of the three, from Wicken Bonhunt, Essex, (473, Suffolk County Council) is the same vivid green-blue as the Flixborough pieces, but is undecorated (Evison 2000a, fig. 16a). Another, from Barking, Essex, is in thicker glass which is opaque, red marbled in colour (382, 1783, 1734; Evison 2000a, fig. 16b). The third, from Whithorn, Dumfries and Galloway, is in yellowish, nearly colourless glass with a pink tinge.

FIG. 2.2. Glass vessels. Scale 1:1. Fragments nos 892–3 and 897–8 are possibly all from the same bowl, and a reconstruction of this is offered in FIG. 2.4.

Except for the Whithorn example, these foot fragments are over 80mm in diameter, and each is an unusual and attractive colour. They must have been vessels of substantial size, but the shape of the body of three of them is not known. At Whithorn, other fragments in this rare colouring are part also of a rim and a body showing decoration by white trails, and a hollow-blown boss or claw (Campbell 1997, 304–5, fig. 10.7.20). The diameter of this folded foot is less than the examples from eastern England, at 60mm, and it is suggested in that publication that the fold may in this case have been limited to the edge only, and that the foot was attached separately to the vessel. However, there is no other example of a separate foot with folded edge, and it is likely that the foot was completely folded as part of the vessel paraison.

As the Whithorn fragments include a blown boss or claw, this suggests the form was that of a claw beaker, and the possibility exists that the other comparable bases might also have belonged to claw beakers. The folded form of the Barking and Wicken Bonhunt bases conforms to the normal claw beaker design, but the Flixborough foot breaks away from this tradition and its separate formation is similar to the foot of the early Mucking beaker, and follows the shape of metal chalices contemporary with parts of the Flixborough occupation sequence, e.g. the Trewhiddle chalice (Wilson and Blunt 1961, 81–2, pl. XXV) where the diameter of the foot is comparable. Glass chalices were well recorded throughout the 9th century, and other forms of glass fragment finds have been regarded as probable candidates for this function because of sumptuous appearance including gold decoration, once in cruciform motifs, but in this instance, in addition, the form of the vessel is close to that of the metal examples (Lundström 1971; Henderson and Holand 1992, fig. 6; Stjernqvist 1999, 84; Evison 2000a, 83-4).

The bicolour trails on the Flixborough beaker (nos 892–3; RFs 8717 and 8723; PL. 2.4), white with a red thread, achieve a polychrome effect like the reticella trails, but without twisting (Evison 1988, fig. 12, 1). The technique makes its earliest appearance on the bag beaker from Dry Drayton, Cambridgeshire (Evison 1983, colour photograph fig. 4c), where some of the ‘zigzag’ trails are yellow and light green-blue. It was first noted on claw beakers in Sweden (Arwidsson 1932, 252, pl. XII), which are closely connected with Anglo-Saxon products. Its use as a substitute for reticella threads is to be noted on one of a group of disc beads of Anglo-Saxon type (Evison 1988, 242, fig. 9; Guido 1999; Evison forthcoming). All are decorated with twisted threads except one from Boss Hall, Ipswich, grave 912, where the threads are white and light blue but untwisted. The use of a fine red thread in a longitudinal fashion is also to be seen on a variety of tall palm cup, decorated with self-colour trails containing a fine red thread (Evison 1988, 242–3; figs 11 and 12, 1).

The vivid green-blue is a colour that occurs only in-frequently; the six fragments at Flixborough are matched by only five at Ipswich. The same distinctive combination of colours as the Flixborough vessel may be seen at Barking where there is a vessel fragment in vivid green-blue decorated with red and white trails which, however, are single and combed in arcades (Evison 1991, 92, 67t). The technique of a trail of contrasting colour, white on light blue-green, applied on a vessel with vertical ribs, also appears at Barking (Evison 1991, no. 67o).

A very close parallel to the Flixborough base is to be seen in a vessel of unparalleled shape and of unknown origin (Stiff 2001). It is in vivid green-blue glass with vertical ribbing, decorated with white horizontal trails. There is also a marvered red trail on the rim, a very rare trait, although an unpublished example of a Valsgärde bowl type sherd with this detail from Dorestad has been quoted (Stiff 2001, 178, n. 3). The chemical analysis of the complete vessel allows it only to be attributed to an Islamic or European origin (Stiff 2001, 179). The shape of this vessel is not a known type in either context; however, the top part follows closely the profile of a globular beaker, if slightly wider in the diameter of the rim. In fact, a globular beaker could have been blown, and the base simply flattened by marvering, as the blower changed his mind about the shape.

Fragment no. 907 (RF 5504; FIG. 2.3) is part of a thin-walled vessel which appears to be black, and includes a neatly applied blob. The edge of the blob is smoothly curved and, although there is no sign of the pulling strain marks sometimes visible in the claws of claw beakers, it may have been slightly hollow. There are no other fragments of this colour on the site, so the shape of the complete vessel cannot be deduced, but the form of a claw beaker is a strong possibility.

Claw beakers were the only complicated shape of vessel known in the early Anglo-Saxon period, and they were produced in England in the 6th and 7th century, and possibly as early as the 5th century. Usually the applied blob was blown into a hollow shape while being drawn down into a tail, but a few were probably not blown at all as the shape was flat. A unique 5th-century example of this feature is the lost beaker from Eastry, Kent (Evison 1982, pl. VIIIa). The claws on beakers of the 6th and 7th centuries were mostly blown to a hollow, rounded shape, but from the end of the 7th century flat claws reappear, e.g. on tall beakers in Sweden (Evison 1982, fig. 5) and in England at Brandon, Suffolk (Evison 1991, 87, no. 66i) and Loveden Hill, Lincolnshire (Evison 1982, 51–52, fig 12g, pl. IVb). Claws in very dark colours, some of which are nearly black, are known from contexts dating between AD 700 and 900, e.g. a very dark green example from Brandon (Evison 1991, 88, 66s iii) and a dark olive green example from York Minster (Evison 1991, 146, fig. 108a ii). Continuance of the use of a flat claw into the vessel type of an even later period is known from a fragment of light-green globular form from a 9th- to 10th-century pit at Saint-Denis, Paris (Evison 1989, 140).

Amongst the body fragments with features, no. 910 (RF 11525; FIG. 2.3) is part of the incurved neck of a brown globular beaker ornamented with marvered yellow horizontal trails, some of which have decomposed, leaving hollow channels. This is similar to two small fragments found at Lurk Lane, Beverley, East Yorkshire, no. 1804 which is brown with marvered white trails, and no. 696 which has an empty channel once filled by a similar marvered trail (Henderson 1991, 126, nos 218 and 220, where the trails are described as ‘opaque red strips). The Flixborough fragment no. 910 (RF 11525) may be compared with the brown rim with white trails no. 887 (RF 11018; FIG. 2.1). It has been noted that the yellow colour might be altered to white by overheating (Mortimer below: section 2.2). Fragments of a brown globular beaker with yellow horizontal trails occurred at Brandon, Suffolk (nos 6212 and 6251) which has possible connections with a reticella-decorated vessel.

FIG. 2.3. Glass vessel fragments and bead. Scale 1:1.

Also decorated with yellow trails are no. 913 (RF 13104), light green-blue with one trail, and no. 915 (RF 14123; FIG. 2.3), which is dark olive green with parallel yellow trails. The latter has a diameter of c.60mm, and is probably from the neck of a globular beaker. A number of similarly coloured fragments at Barking belonged to a globular beaker which also had reticella trails on the lower part of the body (438/650 and nine other fragments). Two fragments have white trail decoration: no. 911 (RF 11526; FIG. 2.3), heat-damaged but probably originally light green, and no. 914 (RF 13934) a very light green-blue.

Amongst the monochrome fragments, there are two decorated with trails of the same colour as the vessel, nos 906 (RF 5463; FIG. 2.3) and 912 (RF 11923; FIG. 2.3), and two fragments are decorated with moulded vertical ribbing: nos 904 and 908 (RFs 2392 and 10172) – both decorative elements used on globular beakers. The piece no. 909 (RF 10173; FIG. 2.3) is a light green-blue vessel, and brown glass has been applied on the surface, apparently in a wide, straight band. In similar colouring is a brown rim from York, applied on a light green-blue vessel (Waterman 1959, 95–6, fig. 22, 35). The Flixborough application, however, appears to be purely for decoration on a vessel wall. Although applied colour is usually in the form of trails, patterns in wider areas like this do occur, e.g. in Birka, grave 557 (Arbman 1940, Taf. 192, 3; Arbman 1943, 179).

As well as the vessels, there are two other glass objects. The first, no. 947 (RF 14334; FIG. 2.3; PL. 2.5, this volume) is a streaky blue tessera. Tesserae have been found on sites of this period where they may have been used in glass-working, in the making of trails or beads, or to provide colour in batches of vessel glass. Some may have been salvaged from mosaics in abandoned Roman buildings, but it is probable that production continued into the 7th and 8th centuries in northern Italy at places such as Torcello, where they were found in connection with a glass workshop (Leciejewicz et al. 1977, 289).

Tesserae have been found in considerable numbers at Ribe, Denmark (Jensen 1991, 37), Paviken, Sweden (Lundström 1981, 17) and Paderborn, Germany (Gai 1999, 160–2). In England numbers are smaller and only one or two pieces have been found. Sites where they occur comprise Glastonbury (Evison 2000b, 197, no. 102d); Fishergate, York (Hunter and Jackson 1993, 1343); Lurk Lane, Beverley, East Yorkshire (Henderson 1991, 129 nos 292–3 and fig. 101); Whitby, North Yorkshire (Evison forthcoming, cat. nos 224–5), the Brough of Birsay, Orkneys, Scotland (Curle 1982, 46–7, no. 645) and Whithorn, where they are mostly attributed to the Roman period or the 12th–13th century (Hill 1997, 269 and 296). A single tessera at Flixborough is but slender evidence for glass-working, but there is a small amount of supporting evidence for such activity in the presence of melted glass droplets, nos 948-9 (RFs 1137 and 5626).1

The bead no. 946 (RF 3562; FIG. 2.3) is multi-coloured with a light and dark green reticella background and an elongated ring-and-dot motif on each side. It figures as type no. J001 in Callmer’s system (Callmer 1977, 90), who dated its occurrence from AD 790 to 845, and less frequently until AD 990 (Callmer 1977, J001, 4, pl. 20). These beads occur in Scandinavia, Europe and also in the Middle East, where they were probably produced (Callmer 1977, 99). Its occurrence in an earlier context at Flixborough was no doubt caused by disturbance (see Volume 1, Ch. 3, and FIG. 3.2).2

Overall, the glass fragments from Flixborough are in fairly good condition with some iridescence and little decomposition, except in the yellow trails. Out of the 65 Saxon vessel fragments of unaltered colour, 18 are light green-blue, the most common colour after AD 700, and there are another 18 fragments in various shades of green-blue, from very light to vivid. Light green and light blue-green are less common than in the era pre-AD 700. Amongst the colours that require added colourants is blue, which first appeared in the 7th century. Also new in the Mid Saxon period are other more definite and striking colours which require specific additions to the metal, for example, vivid blue-green and vivid green-blue, and there are also two fragments of blue-red. One sherd appears to be black, and some are colourless.

The earliest indication of a vessel with reticella decoration at Flixborough may be deduced from the folded rim (no. 883; RF 5000) of a bowl, which must have been decorated with reticella on its lower part. This came from the fill of post-hole 5002 from building 6; the two phases of this building were standing between the late 7th and mid 8th centuries (Periods 2 and 3a). The next reticella-decorated fragment came to rest in a refuse dump (5653) from Period 3, Phase 3biv, late during the 8th century. A further fragment (no. 898; RF 5874) in the same colours as piece no. 883 (RF 5000), possibly even from the same vessel, was finally incorporated into the huge dump 3758 from Period 4, Phase 4ii, dating from the mid 9th century. The remainder came from deposits from Period 5, Phase 5b and Period 6.

Reticella does not occur in pagan graves as vessel decoration, but it does figure on some beads and pendants which were made in England and date to the late 7th–early 8th centuries (Evison 1988, 240–4; Evison 2000a, 49, fig. 1b). On settlement sites the earliest dated occurrence of reticella on a vessel is about AD 700, and finds in contexts later than the late 8th or early 9th century were probably re-deposited, as may have been the case in dumps 3758 and 5503 from Period 4, Phase 4ii at Flixborough. The beaker base or foot fragments in vivid colours, nos 892–3 (RFs 8717 and 8723), were no doubt also an early product, although deposited in a post-hole fill of building 9 from Period 3, Phase 3bv. The bead no. 946 (RF 3562), which can be dated to c.790–990, however, was incorporated into an occupation deposit, possibly associated with building 18, from Period 1, Phase 1b, but may have been disturbed (see endnote 2).

Similar vessel glass to that found at Flixborough, including reticella fragments, has been found at many sites in England and on the Continent, from France to Scandinavia (Evison 2000a, Distribution Map fig. 7). The nearest find spots to Flixborough are Fishergate, York; Whitby and Beverley in Yorkshire; and Monkwearmouth and Jarrow in Durham. There is a certain amount of similarity in the glass from all these places, in form, decoration and particularly in colours, and their general homogeneity has also been established through analysis of their chemical constituents (Bimson and Freestone 2000, 133).

Some of this glass was probably imported from the Continent, but historical records show that requests were sent to France and Germany for glass blowers to come to England in the 7th and 8th centuries (Cramp 2000, 105). Movement of glass-blowing personnel is therefore more likely to have taken place than the transport of finished merchandise. Actual glass-blowing is evident from ovens discovered at Glastonbury in Somerset which were probably in use in the late 7th to early 8th century (Bayley 2000; Evison 2000b). There is no evidence in England for the manufacture of glass from raw materials, but furnaces for the preliminary preparation of glass in the form of ingots, slabs or broken up into chunks, were operating in the Middle East, and this material was shipped to western Europe for secondary working into the finished forms (Foy et al. 1999: Bimson and Freestone 2000, 133). Some visiting craftsmen no doubt accompanied these shipments and passed on their skills to the Anglo-Saxons, so that the finished blown vessels were produced in England.

Notes for section 2.1

In any consideration of the significance of the presence of a tessera on this site, it should be appreciated that there is a quantity of other Romano-British material present amongst the Saxon deposits; some of this may be residual from Romano-British occupation on this site, but other materials appear to have been brought onto the site from a nearby high status site (e.g. the ceramic building material and the altar fragment; see the discussion of the Romano-British material in Ch. 14, below). |

|

Dr Loveluck comments that the bead no. 946 (RF 3562) was incorporated into an occupation deposit, possibly associated with building 18, from Period 1, Phase 1b. This bead type was given a date range between AD 790 and 990 in Callmer’s typology of 1977. Given the possible spatial and stratigraphic associations of this deposit in Phase 1b (see FIG. 3.2, Volume 1, Ch. 3), two explanations for its occurrence present themselves. It has already been noted above that reticella-decorated beads did occur in graves of the pagan period in England, and it is possible that Callmer’s typology may require some modification. Alternatively, given the extent of the re-use of space on the general building plot where it was found (at least six, and probably seven buildings between Phases 1b and 5a), and the truncation and treading in of material, it is eminently possible that the bead was incorporated into the surface of deposit 3348, following successive building demolition. |

Catalogue

Vessel rims

879 |

Rim rolled inwards and cupped, misshapen. Six horizontal trails melted in up to the rim, few bubbles. |

880 |

Rim deeply outfolded with hollow at edge. |

881 |

Rim chip, bubbly. |

882 |

Smooth rim, straight, outsplayed, bubbly. |

883 |

Rim of bowl, deeply folded outwards with hollow, edge thickened, fine horizontal trails inside throughout. |

884 |

Rim thickened by rolling inwards and cupped, small bubbles. |

885 |

Slightly thickened, everted rim, six horizontal yellow trails and two more below. |

886 |

Thin wall with fragment of outfolded rim attached. |

887 |

Infolded rim, c. seven horizontal white trails, damaged by heat. |

888 |

Smoothed rim, misshapen and undulating with parallel elongated bubbles, streaky. |

889 |

Hollow infolded rim, small bubbles, glossy. |

Vessel bases |

|

890 |

Five joining base fragments and five chips. Base of a tall palm cup with double ring ‘punty’ mark, small bubbles. |

891 |

(?) Curved base of tall palm cup, much cracked. |

892 |

Fragment of a blown, applied foot, slightly thickened at edge, with one fine red streak or marvered trail inside rim. A white trail with slight red streak dropped on and turned downwards thirteen times. Many very small bubbles. |

893 |

A smaller fragment of the same foot with a wider red streak or trail on the inside near the edge. Eleven turns of the white trail with its terminal, the sequence of trails closely matching the spacing on no. 888, RF 8723. |

Reticella fragments |

|

894 |

Cylindrical, small bubbles. Marvered reticella trail, curved, S-twist, decomposed. |

895 |

Vertical unmarvered reticella trail, spreading to a dotted contour, S-twist. |

896 |

Globular, three horizontal trails at top, six parallel contiguous rows of half-marvered reticella and one diagonal unmarvered reticella trail below, the yellow trails decomposing. Trails in order S-Z-S-Z-Z-S twist. |

897 |

Globular, bubbly. Two horizontal marvered reticella. Below, two crossing unmarvered reticella (one ending at the top). All S-twist except the top marvered trail. |

898 |

Five decomposed horizontal reticella trails, marvered or half-marvered, four S-twist and the lowest, Z-twist, with one unmarvered trail nearly vertical S-twist. |

899 |

Globular. Vertical unmarvered reticella trail, S-twist, extending widely sideways. |

900 |

Base kick of a globular beaker or bowl. The end of one unmarvered black and yellow reticella trail is present, the yellow extending. S-twist. |

901 |

Four horizontal yellow trails at the top. Below, six half-marvered reticella trails (S-Z-S-Z-Z-S), one diagonal unmarvered S-twist trail. |

902 |

As no. 901, RF 6895 above, two horizontal yellow trails and six half-marvered reticella (S-Z-S-Z-Z-S). |

903 |

End of unmarvered reticella rod on thin wall. Yellow trails unmarvered on light blue translucent, S-twist. Colourless. Decoration: Yellow. L.6mm, c.0.5mm thick. (FIG. 2.2). |

Vessel body fragments with features |

|

904 |

Cylindrical, vertical ribbing, few bubbles. |

905 |

Slightly cylindrical, elongated bubbles. Faint vertical ribbing. Much cracked. |

906 |

Globular, tiny bubbles, three parallel self-trails. |

907 |

Thin-walled vessel with applied blob, ?slightly blown. Glossy, iridescent. |

908 |

Moulded rib, small bubbles. |

909 |

Vessel wall with applied brown band. |

910 |

Incurved ?neck of globular beaker. Four marvered yellow trails decomposing and leaving hollow channels, iridescent. |

911 |

Heat-damaged. Ten white horizontal trails. |

912 |

Globular, two self-colour horizontal parallel trails, unmarvered. Iridescent, few bubbles. |

913 |

One yellow trail, unmarvered. |

914 |

One unmarvered white trail. |

915 |

Incurved with five horizontal trails, neck of globular beaker. |

Vessel body fragments, featureless |

|

916 |

Bubbly fragment. |

917 |

Cylindrical, nearly opaque, bubbly. |

918 |

Globular, tiny bubbles. |

919 |

Slightly cylindrical. |

920 |

Globular, bubbles. |

921 |

Elongated bubbles. |

922 |

Globular, bubbles. |

923 |

Globular, bubbles (cf. no. 918, RF 2733 above). |

924 |

Cylindrical, small bubbles. |

925 |

Two fragments, tiny bubbles. |

926 |

As no. 925, RF 3287. |

927 |

Globular, streaky colouring. |

928 |

Globular, bubbles, glossy. |

929 |

Globular, bubbly. |

930 |

Globular, small bubbles. |

931 |

Colour: Light green. L.12mm, 1.5mm thick. |

932 |

Colour: Light green-blue. L.9.5mm, 0.5mm thick. |

933 |

Colour: blue. L.9.5mm, 1mm thick. |

934 |

Colour: Light green-blue. L.8mm, 0.5mm thick. |

935 |

Two fragments, globular, bubbly. |

936 |

Colour: Light green-blue. L.18mm, 2mm thick. |

937 |

Colour: Light green-blue. L.8mm, 1.5mm thick. |

938 |

Cylindrical, bubbles. |

939 |

Colour: Light green-blue. L.6mm, 0.5mm thick. |

940 |

Globular, streaky colouring, small bubbles. |

Globular, glossy, small bubbles. |

|

942 |

Cylindrical, few bubbles. |

943 |

Bubbles. |

944 |

Chip. |

945 |

Bubbles. |

FIG. 2.4. Reconstruction drawing of glass bowl. Scale 1:1.

Miscellaneous

946 |

Bead, cylinder, tapering at ends. Dark green and light green reticella background with a marvered, elongated ring-and-dot motif on each side in yellow, red and white, with blue centres. |

947 |

Tessera. |

948 |

Droplet. |

949 |

Melted blob. |

2.2 Analysis of chemical compositions of the glass

by Catherine Mortimer

Compositional analysis of the vessel and window glass from Flixborough enables wider comparison with material from other sites of the same period. Chemical data can also be used to investigate whether glass fragments with unusual appearances are potentially later than the main phases of occupation, and hence whether there was a degree of post-depositional disturbance of the relevant contexts.

Analytical details

Small samples (c.2mm in size) were taken from 16 vessel glass fragments and seven window glass fragments. The sampling strategy was designed to include at least one example of each colour of vessel glass, although some of the pieces of interest were too small or deemed too rare to attempt sampling. Three of the samples were from vessel fragments with applied opaque glass decoration which could also be analysed. Two samples were taken from vessels of non-Saxon types. Similarly, one sample was taken of each of the three colours of Saxon window glass which were present in the collection, together with four samples from colourless window fragments which were thought less likely to be Saxon, on typological grounds. Analysis was carried out using energy-dispersive X-ray analysis in a scanning electron microscope (FIG. 2.5).

Results: vessel glass

The majority of the glasses analysed are of the soda-lime-silica type which is typical for the Saxon period. The compositions are quite uniform, with the major and minor elements lying within small ranges, with few exceptions.

The major colourants for the translucent glasses analysed are oxides of iron, manganese and copper. Iron and manganese are often present in ancient glasses, introduced in minor amounts with the glass-making ingredients. Depending on the oxidisation state, these two components combine to give a range of tints, from blue, through green, yellow, and pink to brown, and in strengths from very pale to very dark. Occasionally, the balance between iron and manganese oxides and the precise oxidisation state can cause a colourless glass. The first 10 of the vessel samples listed in FIG. 2.5 have colours which are most likely to be attributable to the presence of iron and manganese alone. In the case of the two bright blue-green fragments analysed (nos 928 and 938; RFs 3529 and 6196), the observed colour is due to the presence of nearly 2% copper oxide; and two paler blue-green fragments (nos 924–5; RFs 2757 and 3287) also have elevated copper levels. Catalogue no. 917 (RF 517) was noted to be opaque blue. Copper is below the detection limit (0.2% CuO) in this case, and other elements may have caused the colour. The blue colour may possibly be due to the iron oxide present being in the reduced form, but the colour resembles a classic cobalt blue. As cobalt is a very strong colourant, it may be present at levels below the detection limits of this analytical technique, but may still give the blue colour. This sample has high levels of antimony oxide which may have contributed to the opacity, in the form of antimony-rich crystals. In addition, small bubbles were clearly visible to the naked eye.

Occasionally, elevated lead contents are noticeable amongst the translucent glasses. This is possibly due to contamination during the melting, and it probably does not contribute much to the glasses’ colour or working properties at the low levels noted here (0.2–1.07% PbO). The highest lead level (in bright blue-green fragment no 925, RF 3287) coincides with elevated levels of copper and tin, suggesting that the copper may have been introduced in the form of a copper alloy, rather than pure copper.

Recent research suggests that the composition of early medieval vessel glass is remarkably homogeneous (Hunter and Heyworth 1998). So, for example, it is not surprising that the lightly-tinted vessel glasses from Flixborough show a very close similarity with those from Hamwic (op. cit., Table 12), for nearly all oxides and elements. The one exception is the phosphorous content, which at Flixborough is half the average amount at Hamwic. Analytical discrepancies seem unlikely to account completely for this difference. Instead, this seems to be a genuine feature, possibly relating to the use of cullet (seen archaeologically at Hamwic), the re-melting of which may have allowed the incorporation of fragments of wood ash which contain phosphorous.

Hunter and Heyworth’s research suggested that vessels from Hamwic may be distinguished from other sites on the basis of precise analyses of minor and trace elements, such as copper and nickel. Although SEM-EDX analysis has rather high detection levels for these elements – and nickel was not analysed in the current project – it is clear that none of the lightly-tinted Flixborough samples had elevated copper levels, as was noted amongst samples from London, Repton and Quentovic (op. cit. Table 13). The overall homogeneity of early medieval vessel glass probably represents a single source of glass, or of glass-making components, although it is impossible to say anything more about the source until more workshop evidence is available.

Fragment RF 3351 is unusual both in its appearance and its composition (see Ch. 14). The sample is dark green and has a form which is most likely not Saxon. The most obvious compositional features are the very high lime (25.35% CaO) and low soda and potash (1.1% Na2O and 1.23% K2O). These features make it very unlikely that this sample is Saxon. Instead, the high-lime and low-alkali composition can be compared with some from post-medieval glasses from London (e.g. Mortimer 1991, Table 5; Mortimer 1995), dating from the 17th and 18th centuries, although the lack of detectable phosphorous is unusual in this grouping. The fragment was recovered from an unassociated post-hole, floating in the site’s chronology between Periods 5 and 6, in site area A (Loveluck, Volume 1, Ch. 2, FIG. 2.3). This area was subject to considerable erosion and accumulation of material as the slope of the sand spur had deteriorated or been disturbed in quarrying. This probably accounts for the incorporation of a post-medieval glass fragment into the feature, from late in the Anglo-Saxon occupation sequence (Loveluck, Volume 1, Ch. 2, FIG. 2.2).

A pale green glass fragment, sample 716 (moulded latticework, see Ch. 14) is of an unknown form, if Saxon, on the basis of its typology; however, the composition is indistinguishable from those of the Saxon glasses found at the site, so there is no scientific reason to identify this piece as suspect. Very few medieval and later glasses have comparable compositions, but three 11th–16th century parallels are known from London and Beverley (Mortimer 1998b, sample 1190 from Swan Lane; Henderson 1991, samples 18 and 22). The fragment RF 716 came from the fill of a pit associated with structures 36 and 37, in area G of the site, the shallow valley between the two sand spurs. It was subsequently overlain by ‘dark soil’ refuse from Period 6, and although the area was disturbed by some ploughing and animal disturbance, which introduced a small number of medieval pottery sherds, there is currently no evidence to prove that the glass fragment was not deposited in the Anglo-Saxon period.

Opaque glass used in trails and reticella on vessels

Three vessel samples had opaque trails or reticella on them. Analysis showed that tin oxides and lead-tin oxides gave these glasses their opacity and colour. Opaque yellow glass is produced due to the presence of crystals of lead-tin oxide (PbSnO3) and opaque white glass by tin oxide (SnO2). However, the white trails on no. 887 (RF 11018) have a very high lead content (nearly 47% PbO), suggesting that the white colour in this case may be due to overheating a glass which was originally yellow; overheating causes the yellow colour of the lead-tin oxide to be lost irreversibly (Rooksby 1964, 21). Antimony was also detected in this sample, which may have contributed to the opacification. There is extremely close compositional similarity between the two examples of opaque yellow glass analysed (nos 897 and 902; RFs 5348 and 7012), hence they could have come from the same vessel.

The tin oxide contents seen in these two, opaque yellow glasses are typical for Saxon and medieval examples. However, a very wide range of lead oxide contents has been found in other opaque yellow glasses of the period. For example, the lead levels seen in opaque yellow glass used for some early Anglo-Saxon beads (e.g. Henderson 1991; Mortimer 1996; 1998a) and on some Viking pieces from Ribe (Henderson and Warren 1983) are closely comparable to those in the Flixborough examples, but two opaque yellow glasses used to decorate vessels from Hamwic (Henderson 1998) have much higher lead oxide contents (44.9 and 48.4%). This demonstrates that this type of glass did not require tight controls on composition.

The opaque white glass analysed from Hamwic has a relatively low lead content (9% PbO), which would have made it easier to achieve a good opaque white colour without risking developing too strong a yellow tint; a small amount of lead would have helped the initial solution of tin oxide dissolve into the glass. This makes it even more likely that the opaque white colouration of the Flixborough example was caused by overheating a yellow glass, rather than deliberate manufacture of a white glass. Amongst later opaque white glasses, lead and tin oxide contents are often nearly equal and often lower (e.g. in 16th-century Venetian glass: Mortimer 1993).

Results: window glass

The first three fragments listed (nos 1371 and 1373–4: RFs 10205, 5545 and 2684) are compositionally very similar to the Saxon vessel glass samples analysed above. The blue sample (no. 1371: RF 2684) is coloured by copper (and possibly by cobalt at levels below detection limits) and has significant amounts of antimony present, comparable to the situation in the opaque blue vessel glass sample no. 917; RF 517. Analysis shows that the compositions of the two colourless window glass fragments (nos 1382–3: RFs 11496 and 1128) are quite comparable to the Saxon glasses at the site, hence these pieces could well be Saxon, despite their unusual appearance. It is also possible that these pieces are Roman. The colourless appearance must be due to fine control of the furnace atmosphere, since the iron to manganese ratio is very similar to those in other more highly coloured pieces.

These five pieces and window glass fragments from several other early medieval sites show close similarities in composition. The samples from Monkwearmouth and Jarrow (Frost 1970) seem a particularly good match. These were analysed by electron probe micro-analysis, which should provide good analytical comparability. However, this apparent close match may be fortuitous, related to small sample numbers, and conceals significant colour-related differences, since individual samples of particular colours are not particularly similar. It is noticeable that other groups of window glass, from Hamwic, Winchester and Repton (Hunter and Heyworth 1998) are also broadly similar to the Flixborough glasses.

Finally, two colourless window glasses (nos 1385–6: RFs 3431 and 11567), thought to be post-medieval on the basis of typology, proved to be soda-lime-silica glasses, but with lime and soda values which are outside the range seen in the other Saxon glasses at the site. Their alumina (Al2O3), magnesia (MgO), potash (K2O), sulphur (S) and iron (Fe2O3) values are also outside the range seen in the Saxon glasses. Furthermore, no. 1385 (RF 3431) is the only glass analysed to have no detectable chlorine present. The high lime and low soda concentrations are similar to those found in a few medieval and post-medieval glasses, e.g. from London (Mortimer 1991, Table 2) and France (Foy 1985), but the iron, magnesium and potassium values are much lower than seen elsewhere. Fragment no. 1386 (RF 11567) was found in the fill of a post-hole (440) associated with structure 38, possibly a granary from Phases 5a to 5b. This structure was situated in site area G, on the edge of the shallow valley, which had been subject to some medieval to post-medieval ploughing. This had incorporated a small number of medieval pottery sherds into deposits in this area, although structure 38 was overlain by ‘dark soils’ from Period 6 of the Anglo-Saxon occupation sequence. It is possible that the glass is of post-medieval date, but the highly enigmatic nature of the fragment does not allow for any firm conclusion. Piece no. 1385 (RF 3431) was re-covered from an occupation spread (2610) dated to Period 5a, which was subsequently overlain by deposits from Periods 5b and 6. As with the vessel glass fragment RF 3351, from the same area of the site, the window glass fragment could have been incorporated into 2610 as a result of erosion of the spur slope (Loveluck, Volume 1, FIG. 2.2).

Conclusion

The glass from Flixborough conforms to the uniform composition of the early medieval period. This uniformity indicates similar sources of glass-making components or, more likely, of glass, for all areas of Saxon England.

Acknowledgements

Samples were mounted by Malcolm Ward, Ancient Monuments Laboratory, English Heritage. Electron microscopy and qualitative EDX analyses were carried out at the Ancient Monuments Laboratory, English Heritage. Quantitative EDX analysis was carried out by Karen Leslie, Dept of Scientific Research, British Museum (Project 7097). Ian Freestone, Dept of Scientific Research, British Museum, gave extremely helpful advice on various aspects of glass composition.

2.3 Copper-alloy vessels and container mounts

by Nicola Rogers, with a contribution by Susan M. Youngs

Vessels

Copper alloy vessel fragments

Only five probable vessel fragments were recovered, three of which came from stratified deposits (nos 950–52; RFs 2550, 3279, 12354); the others (nos 953–4; RFs 1010, 13789) were unstratified. Made of sheet, no. 950 (RF 3279) was found in Period 2 occupation levels; traces of sooting indicate possible use as a vessel such as a cauldron, possibly similar to that found at the Saxon cemetery at Watchfield, Oxon. (Scull 1992, 211, illus. 69, no. 83.133). Nos 951 and 953 (RFs 1010, 12354) are rim fragments, and no. 954 (RF 13789) a body fragment; no. 952 (RF 2550) has a perforation possibly the result of a repair. All are too small to enable identification of the original vessel from which they came, but apart from the cauldron, other possible forms include bowls and long-handled skillets; two skillets were found at Whitby (Peers and Radford 1943, 66, fig. 16). Some of the sheet fragments included as manufacturing debris (see Ch. 11, FIG. 11.5) may also have originated from vessels.

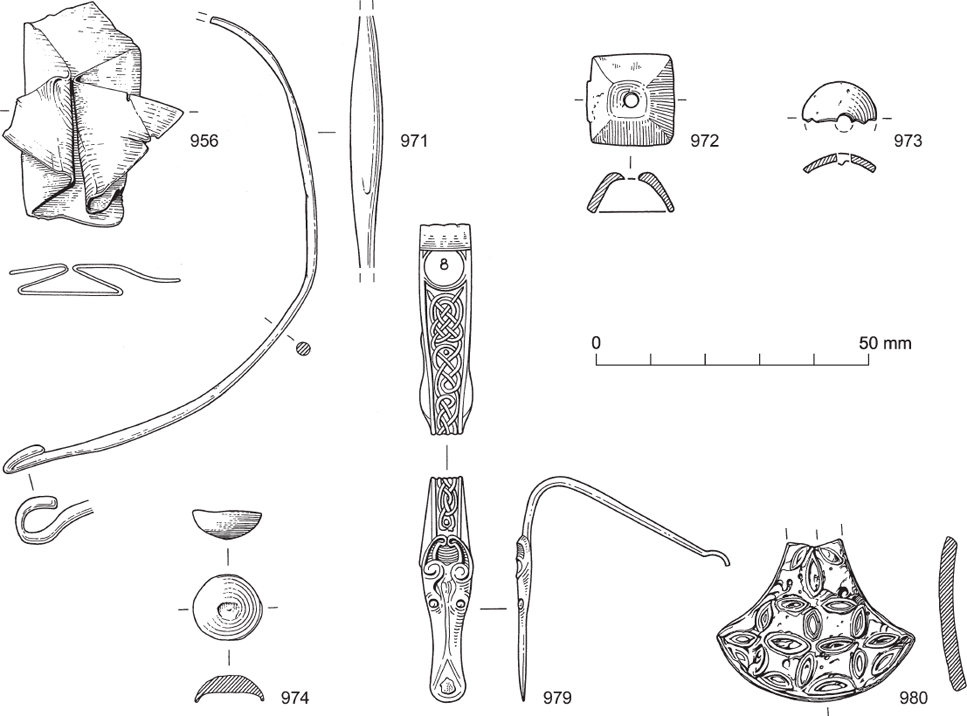

Patches (FIG. 2.6)

All the sheet metal patches found at the site were unstratified (nos 955–60; RFs 1001, 1019, 12355, 13001, 13288, 13453). Nos 955, 958 and 960 (RFs 1001, 13001, 13453) are sheet fragments retaining part of a patch, while no. 957 (RF 12355) is itself part of a patch. Apart from use on sheet vessels, non-ferrous metal patches are also known to have been used on vessels or containers of leather and wood (Scull 1992, 164, illus. 28, 83.21a–b; 213, illus. 70, 83.151).

Sheet rivets

These are used to attach patches such as those described above to metal vessels, and are simply formed from a piece of sheet with two arms and used in the same way as modern brass paper fasteners; these arms go through a hole in the vessel to be repaired and are then folded back onto the wall of the vessel keeping the patch in place. Seven rivets were found in stratified deposits (nos 961–7; RFs 3591, 7952, 2082, 7040, 8170, 6570, 4348), of which five (nos 963–7; RFs 2082, 7040, 8170, 6570, 4348) came from Period 5 or 6 levels. There are also three unstratified rivets (nos 968–70; RFs 11939, 12706, 12793).

FIG. 2.5. Table showing chemical components of Flixborough glasses (EDX analysis of Flixborough glasses, weight percent)

Accuracy and precision are believed better than ±2% relative for SiO2, ±3% relative for CaO, ±5% relative for Na2O, ± relative for components <3% and ±20% relative for components between 1 and 3%. The minimum detectable limit for P2O5 may be closer to 0.2% than the given 0.1%.

Vessel handle (FIG. 2.6)

An unstratified find, no. 971 (RF 10904; FIG. 2.6), is part of a drop handle with one surviving hooked end, and a flattened area in the handle’s centre; similar examples have been found at Hamwic (Hinton 1996, 50, fig. 20, no. 177/821), Brandon (no. 2012) and Sedgeford, Norfolk – the last example retaining a decoratively-shaped perforated plate on one hooked end for the attachment of handle to vessel, and found in a context which also contained a 9th century strap-end (R. Ludford, pers. comm.)

Container Mounts

Pyramidal mount (FIG. 2.6)

No. 972 (RF 1245; FIG. 2.6) is a squat truncated pyramid with a central rivet-hole; it has traces of gilding on one face. Although recovered from Phase 6iii dark soil, its shape bears resemblance to gold pyramidal mounts decorated with garnets, glass inlays and millefiori found at Sutton Hoo (Bruce-Mitford 1978, 300–2, fig. 227), and to copper alloy mounts found at the Saxon sites of Barham and Coddenham, Suffolk (West 1998, 7, fig. 5.48; 22, fig. 21.22–3), and an Anglo-Saxon cemetery at Tuddenham, Suffolk (Kennett 1977, 48, fig. 5, no. 25). Unlike the Flixborough mount, all the East Anglian mounts have pairs of slots on their bases, and the Sutton Hoo mounts were interpreted as embellishments to leather or textile tapes which tied the sword blade to the scabbard (Bruce-Mitford 1978, 581); this is clearly not a function of the Flixborough mount, but it may have been riveted onto a leather belt, and it is almost certain to be earlier in date than its context suggests.

Domed mounts (FIG. 2.6)

Three plain domed mounts were recovered (nos 973–5; RFs 1348, 10585, 12802); no. 975 (RF 12802) was unstratified, while the other two mounts came from Phase 5b–6i (no. 974; RF 10585; FIG. 2.6) and Phase 6iii (no. 973; RF 1348; FIG. 2.6) deposits. This simple mount form is essentially undatable – they are known from the Roman period onwards, and would probably have been used on small boxes or on belts. No. 975 (RF 12802) would have been attached via solder, while no. 973 (RF 1348) has a rivet-hole; it is unclear how no. 974 (RF 10585) would have been affixed.

Miscellaneous mounts (FIG. 2.6; PL. 2.7)

Sub-trapezoidal with two iron rivets, no. 976 (RF 7360) is undecorated, as is the sub-circular disc (no. 977; RF 12803) which has solder on the underside. The incomplete (no. 978; RF 13550) is sub-oval, one end being broken across a rivet-hole, and with three other rivet-holes in the sides. All the mounts were unstratified.

No. 979 (RF 14087; FIG. 2.6; PL. 2.7) was unstratified. Made of copper alloy, it appears to be incomplete at the upper end which retains part of an integral loop; below this, there is a rivet-hole which appears originally to have been covered by a domed – perhaps decorative – rivet or stud head, as hinted at by the circular field around it. Here the object begins to taper and then takes on a bulbous form, at which point the body has been bent; it then broadens out again at the lower end. The object terminates in an animal-shaped head with a long snout with slightly concave edges with an irregular patch of silver inlay close to the tip. The snout has a rounded tip or mouth, and appears to be of plano-convex section; the eyes are of yellow glass and each has a spiral behind, with incurved ears with rounded tips. The upper part of the object has a tapering strip field, of apparently asymmetrical interlace incorporating differing closed circuit motifs at each end.

The use of animal heads as seen from above as motifs in metalwork became popular in the 9th century, when they are commonly found as terminals on strap-ends, although examples from the late 8th century are also known (Tweddle 1992, 1149–50, fig. 575b). Aside from strap-ends, these heads occur on 9th-century rim clamps attached as repairs to the late 8th-century Ormside bowl (Webster and Backhouse 1991, 173, no. 134), and on two mid-9th century objects from East Anglia – a seal-die from Eye, Suffolk, and a censer from North Elmham, Norfolk (ibid., 238–9, nos 205–6). An animal head with longish snout with concave sides also forms the terminal to the crest on the Anglian helmet found at Coppergate, and dated to the second half of the 8th century (Tweddle 1992, 975–80, 1148–56). The detail of the head and the interlace also indicate a probable late 8th-century date; the spirally-shaped ears, and the ribbing around and between them, and the glass eyes all echo the animal-headed terminals of the St. Ninian’s Isle scabbard chapes (Webster and Backhouse 1991, 223–4, no. 178), while the changing nature of the interlace, the open space around it and the pellets are characteristic of late 8th–early 9th century sculpture (R. Cramp, pers. comm.; Cramp 1978, 8). Wilson notes an 8th–9th century pair of gilt bronze tweezers decorated in a remarkably similar fashion to no. 979 (Wilson 1964, 161, no. 62, pl. XXVIII), with the broad rounded snout and curled ears on the animal-head terminal, with a strip field of interlace above.

The function of this object is uncertain; although in shape the object is reminiscent of helmet crests, such as that on the Coppergate helmet, or sword mounts, such as that on sword 1 from grave 7 at Valsgärde, Sweden (Bruce-Mitford 1978, fig. 216), in size, no. 979 (RF 14087) is much too small for such a role. The rivet seems to indicate use as a fitting of some kind, perhaps from a non rigid container such as a leather bag or satchel.

FIG. 2.6. Copper alloy vessel patch, drop handle, container mounts, and champlevé-enamelled hanging bowl mount. Scale 1:1.

An enamelled hanging bowl mount (no. 980, RF 5717; FIG. 2.6 and PL. 2.8) by Susan M. Youngs

This detached fragment is an almost complete copperalloy casting, 24 × 33.5mm, curving in two planes. The shortest edge at the apex is damaged, but part of the rim remains. The outer convex surface is recessed for enamel, leaving a pattern of open vesicas, or petals, in reserve. This is champlevé work, despite the cell shapes which give the impression of the separate walls of cloisonné enamel. Enamel remains in most of the setting, largely discoloured black but showing the original bright opaque red in places. The curvature, form, ornament and use of enamel confirm that this is a decorative appliqué mount originally made as part of a set of mounts for the body of a bronze hanging bowl.

These bowls were designed for suspension in a frame or tripod, and often have richly decorated mounts both for the suspension hooks and purely for decoration. They must always have been prestige items. Complete examples, with one Scottish exception, have been recovered in eastern and southern England amongst the furnishings of Anglo-Saxon burials of the later 6th and 7th centuries (see Brenan 1991 for a gazetteer, detailed description and analyses of context. The finds from Lincolnshire up to 1990 are published in Bruce-Mitford 1993, with further finds in Bruce-Mitford and Raven 2005). It is clear from the evidence of repairs and the techniques of manufacture, which often include the extensive use of enamel, that these vessels were exotic imports and prized items in the Anglo-Saxon culture, like the Coptic and Frankish bowls found in the same contexts. They were not originally made for Anglo-Saxon patrons, even though the ornament of the appliqués show increasing influence from the Germanic artistic repertoire. In the course of the 8th century hanging bowls were certainly made in the Anglo-Saxon idiom for local patrons, as the lost silver Witham bowl spectacularly demonstrated, and the recent hooked mount from Barningham in Suffolk confirms, but the Flixborough enamel is in an earlier tradition where enamel was used extensively (for the River Witham bowl, see Bruce-Mitford 1993, 26, pl. 9; Graham-Campbell 2004. For the Suffolk mount, see Martin et al. 1996, 457, fig. 99e).

The Flixborough find is of interest because it comes from a settlement and not a cemetery. A circular hook mount was excavated in the Anglo-Saxon village of Chalton in Hampshire, a number of related items were found at the monastic complex at Whitby, N. Yorkshire, and an assemblage similar in range to the Whitby Celtic pieces was recovered more recently by metal-detecting at a coastal site at Bawsey in North Norfolk (for the Chalton find see Addyman and Leigh 1973, 1–25 and pl. VI; also, Bruce-Mitford 1987, pl. 11e; Bruce-Mitford and Raven 2005, 131–2, 215–17, and 300–5). Lincolnshire is exceptionally rich in hanging bowls as grave furnishings, including one in the church of St Paul-in-the-Bail, Lincoln, and the apparent ease of access to bowls in this region has implications for the economic, political and social life of the area (Leahy 2007a, 84–5). Eighteen complete hanging bowls have been recovered from Lincolnshire, more than from any other comparable region of Anglo-Saxon Britain, a peculiarly rich inheritance (Bruce-Mitford 1993). It is also a rare find which helps to bridge the archaeological gap between the tranche of bowls preserved because of Anglo-Saxon mortuary practices in the late 6th and first half of the 7th centuries, and the Irish bowls similarly preserved in Scandinavian Viking-period burials of the 9th and 10th centuries.

The form and decoration are also of considerable interest. A bowl fitted with a suite of hook mounts and decorative plates lavishly enamelled and decorated to match this piece would have been a spectacular vessel. Appliqués of similar form were used in pairs on an elaborately mounted bowl from a burial at Lullingstone, Kent, as part of a complex and varied set of mounts. Panels of this shape are described as ‘axe-shaped’ and have been related to Anglo-Saxon horse-bit fittings of this shape, an association which appears obvious in the case of the Lullingstone bowl with its Germanic-style interlace, but given the use of the pelta or ‘mushroom-shape’ in earlier and contemporary non-Germanic metalwork, the form of the Flixborough find was not necessarily derived uniquely from a recently imported model but is in the native La Tène tradition, both proposed models being based on a pattern of arcs. The same ‘axe’ or fan-shape appears in miniature as an integral appendage to a circular bowl mount with spiral ornament found at Kemsing, Kent (Youngs 2001, fig. 7), a combination of shapes which is repeated on two 8th-century Irish studs (Youngs 2003, 160). The curved apex of the Flixborough mount was presumably set against an ornamental disc, either as one of a flanking pair as on the Lullingstone bowl, or suspended below it in the design of the Kemsing mount.

The decoration on the Flixborough find is distinctive (FIG. 2.6 and PL. 2.8) and falls within a strand of classicising ornament used by the smiths who decorated these bowls. While they are best known for the triskeles and peltas of the archaic Iron-Age tradition, rule-and-compass derived motifs are also present in the extensive medieval repertoire. The slightly uneven pattern seen here is derived from a basic design of intersecting arcs, a pattern which has a varied range of applications, with some, as here, emphasising the intersecting arcs which form lentoid or petal shapes, while others used inlaid dots to emphasise the spaces left between.

The switch from inlaid petal-shaped recesses to reserved lines against a solid enamel background as seen here, was probably made during the later 6th or first half of the 7th century. It can be seen used in similarly open arrangement on the tail of the Kemsing mount (Youngs 2001, fig. 7). It is also a feature of an elaborately ornamented enamelled basal mount from a hanging bowl found at Bekesbourne in Kent, where open petals were used in combination with other, innovative motifs including stylised birds’ heads (op. cit., fig. 8; Haseloff 1958, 209–46; Brenan 1991, 184–5). The centre is in the style of the Flixborough find, but on the latter this motif is used exclusively as a carpet. Norfolk has provided a large circular disc from Caister-on-Sea which is completely filled with a linked pattern of rather stiff open petals of the Flixborough kind, and a further variation is seen on a flat enamelled mount from Bawsey in the north-east of the county where the pattern was created from lozenge-shaped elements which interlock to cover the entire surface (Youngs 2001, fig. 9a, b, where the disc was incorrectly associated with Bawsey).

This Bawsey piece is not a cemetery find, but from an assemblage of largely Middle- and Late-Saxon material, and this raises questions about the presence of such a mount in the community at Flixborough. It could have reached this affluent settlement on a complete bowl for use on site either as a dining accessory, or as a lamp reflector in the church (two of the various uses proposed for these bowls in an Anglo-Saxon context). Material from the occupation of the site in the 7th century was recovered elsewhere. It could equally well have arrived later, or separately as a curio, or as spolia for re-use in some way, like the metal for Flixborough strap-end no. 66 (RF 552). All that can be said is that there is no piercing for re-use as jewellery, or for re-attachment, a feature of some detached bowl mounts.

The Flixborough hanging bowl mount (no. 980; RF 5717) came from a dump in which the pottery indicates deposition in the late 9th and early 10th century, but which included a number of residual finds of earlier material. The bowl mount is probably one of the earliest of the medieval items which include a Series G type 3a sceat of early 8th-century date. This phase of use of the site also saw the deposition of the late 8th- or early 9th-century inscribed lead plaque (no. 1019; Ch. 3). As to the original date of manufacture, the ornament and lavish use of red enamel suggest that this piece could have been made as late as 700, but not significantly later, but that it could have been up to 50 years earlier in the 7th century. The present state of our knowledge about the absolute chronology of the hanging bowls found in Britain is such that this is very much a provisional opinion. The anchor-point remains the three very different and technically complex bowls found in the mound 1 burial at Sutton Hoo, Suffolk, deposited in the 620s. What we do not know is how long the British tradition of enamelling in this style persisted up to and beyond 700, by which date the production of polychrome enamelling had also become well established in Ireland.

Catalogue

Vessels

VESSEL FRAGMENTS

950 |

(?) body fragment, irregularly shaped, with traces of sooting on one edge. L.48.9, W.20, Th.1 |

951 |

Rim fragment, distorted. L.41.4, W.30.5, Th.1.3 |

952 |

(?) body fragment, with perforation. L.13, W.8.7, Th.1.3 |

953 |

Rim fragment, irregularly shaped, lower edge broken and partially folded up. L.55.7, W.12.9, Th.1.3 |

954 |

Body fragment. L.65.1, W.27.2, Th.1.6 |

PATCHES (FIG. 2.6) |

|

955 |

(?) repaired patch, of sheet, one edge folded over and flattened, corner of other edge appears riveted down, secondary patch riveted on towards lower edge. L.40.6, W.28.4, Th.0.7 |

956 |

Fragment of sheet, sub-rectangular, long edges folded in and out. L.41.2, W.32.4, Th.4.8. (FIG. 2.6) |

957 |

Fragment of sheet, irregularly shaped, one edge bent over, another edge broken across perforation. L.29.2, W.26.8, Th.1.2 |

958 |

Attached to sheet fragment, also 7 other sheet fragments. L.25.7, W.24, Th.3.7 |

959 |

Fragments (2), adjoining, of folded sheet. L.41.4, W.27.3, Th.3.4 |

960. |

Fragment of sheet, irregularly shaped with three cut edges, fourth roughly broken, retains four sheet rivets, one rivet partially covered by additional sheet fragment. L.47, W.37.5, Th.0.7 |

FOLDED SHEET RIVETS |

|

961 |

Sub-rectangular. L.17, W.12.4, Th.1.6 |

962 |

Fragment, broken across a perforation. L.11.2, W.10.2, Th.1.8 |

963 |

Fragment. L.15.8, W.14.4, Th.3.6 |

964 |

Fragment. L.10.5, W.9.3, Th.2.3 |

965 |

Fragment. L.8, W.6.2, Th.0.9 |

966 |

Fragment. L.16.2, W.13.7, Th.2.8 |

967 |

Rivet in two fragments. L.20.9, W.13.7, Th.2.5 |

968 |

Rivet or patch. L.31.7, W.23.2, Th.3.9 |

969 |

Incomplete. L.24.7, W.18.3, Th.3.7 |

970 |

Fragment. L.12.6, W.11.4, Th.2.1 |

VESSEL HANDLE (FIG. 2.6) |

|

971 |

Fragment, one end broken away, of circular section with central flattened area with incised lines along edges, surviving end hooked up. L.115.9. Wire section diam. 2.2. Flat area W.4.9 Th.1.1. (FIG. 2.6) |

Mounts |

|

PYRAMIDAL MOUNT (FIG. 2.6) |

|

972 |

Truncated pyramid with central rivet-hole, hollow, slight lip on one edge, gilding on one face. L.16.7, W.15.9, Th.1, Height 5.5. (FIG. 2.6) |

DOMED MOUNTS (FIG. 2.6) |

|

973 |

Fragment, circular, domed with central rivet hole. Diam. 13.4 Th.1.1, Height 4.2. (FIG. 2.6) |

974 |

Circular, domed. Diam. 12.1 Th.0.9. (FIG. 2.6) |

975 |

Domed with traces of probable solder on inside. Diam. 12.9 Th.0.9, Height 5.1 |

MISCELLANEOUS MOUNTS |

|

976 |

Sub-trapezoidal, broader end convex, with two iron rivets. L.15.9 W.12.7 Th.1 |

977 |

Sub-circular disc of thin sheet, with probable solder on the underside. L.25.5 W.23 Th.0.7 |

978 |

Incomplete, sub-oval, one end broken across a rivet hole at one side, three further rivet holes in sides. L.28.2, W.15.4 Th.0.9 |

979 |

Fragmentary, broken off at one end across integral loop with rivet hole below; at this point, the object begins to taper and takes on bulbous form, broadening out again at lower end where object terminates in an animal-shaped head with a long snout with slightly concave edges and silver inlay close to the tip. The snout has a rounded tip or mouth, and appears to be of plano-convex section; each of the circular eyes which contain yellow glass, has a spiral behind, with incurved ears with rounded tips which are ribbed. The upper part of the object has a tapering strip field of apparently asymmetrical interlace incorporating differing closed circuit motifs at each end, and the whole object is bent just above the animal head. L.80 W.10 Th.2.8. (FIG. 2.6; PL. 2.7) |

980 |

Almost-complete copper alloy hanging bowl mount, curving in two planes while the shortest edge at the apex is damaged, but part of the rim remains. The outer convex surface is recessed for enamel, leaving a pattern of open vesicas, or petals, in reserve. This is champlevé work, despite the cell shapes which give the impression of the separate walls of cloisonné enamel. Enamel remains in most of the setting, largely discoloured black but showing the original bright opaque red in places. The curvature, form, ornament and use of enamel confirm that this is a decorative appliqué mount originally made as part of a set of mounts for the body of a bronze hanging bowl. [For the affinities of and parallels to this piece, see the discussion above in the main text, and Youngs 2001.] |