3 Artefacts Relating to Specialist Activities

This chapter examines the objects connected with such specialist and diverse pursuits as owning and riding horses, weaponry and combat, and literacy. Some of these shed light on the status of at least some of the inhabitants, whilst others may offer an insight into the nature and role of the settlement.

The site has yielded not only the largest single assemblage of styli from any early medieval site in Britain, but also two inscribed objects, and a possible book cover mount. The significance of this evidence for literacy at the Flixborough site, and for the changing nature of the character and lifestyles within the settlement at different periods, is discussed at length in Volume 4, Ch. 9 (see particularly Loveluck, section 9.2), to which the reader is referred.

There is also a limited amount of evidence for both horse-riding and for owning weapons at the site, but, to put this into perspective, this constitutes just over 0.1% of all the recorded finds from the site.

Lastly, a small number of iron bells and bell clappers, which might be associated with liturgical use, are included in this chapter; however, it is equally possible that some of these may have been hung around the necks of animals.

***

3.1 Horse equipment

by Patrick Ottaway

It is very striking that items of both horse and riding equipment were very scarce at Flixborough, although one would not expect a large number of the latter in Middle Anglo-Saxon contexts as stirrups were probably not introduced to this country and spurs not re-introduced (after previously being used in Roman times) until the late 8th or early 9th century.

Bits (FIG. 3.1)

There are two links (nos 981 and 983; RF 701 – Phase 6iii and RF 13511 – unstratified) from the usual type of snaffle bit found in Anglo-Saxon contexts. However, the most interesting item of horse equipment is no. 982 (RF 1395; Phase 2i–4ii) which exists as an incomplete cheek piece ring with a short projection attached to a bar with domed terminals (FIG. 3.1). Wrapped around the projection and bar is an incomplete fitting with a pierced, oval terminal and the stubs of two curving arms. The function of this fitting is unclear, but it presumably connected the cheek-piece to part of the bridle. The whole object is tin-plated. Cheek-pieces with bars of various forms are known from the 7th century onwards, but there is no close parallel for the Flixborough example.

A bridle fitting, seven horseshoes and 30 horseshoe nails are likely to be of medieval or later date, and so are catalogued in Chapter 14, below; only two of the horseshoe nails (RFs 6540 and 8265, from Phase 6ii and 6iii contexts respectively) may be late Anglo-Saxon as the horseshoe was probably introduced in the late 10th century (Ottaway 1992, 707–9). The D-shaped heads of RFs 6540 and 8265 are those of the ‘fiddle key’ type of nail used at this time.

Catalogue

BITS (FIG. 3.1)

981 |

Snaffle link. L.92mm |

982 |

Incomplete ring cheek-piece with short projection to the centre of a bar with domed terminals. One terminal has five grooves radiating from the tip, and the other has four. Wrapped around the bar and projection is an incomplete fitting with a pierced oval terminal at one end, and the stubs of two curving arms. Plated (tin). Ring: D.50; bar: L.69mm (FIG. 3.1) |

Snaffle link. L.88mm |

3.2 Weapons and armour

by Patrick Ottaway

Seax (FIG. 3.1)

No. 984 (RF 942; unstratified) is a small seax which in its current incomplete state measures c.247mm in length, but originally was probably c.300mm. The blade has an ‘angle back’ (see below, p.203) and is pattern-welded.

Arrowheads (FIG. 3.1)

There are eight arrowheads (three unstratified). Two are socketed leaf-shaped blades (nos 991 and 993: RF 9860 – Phase 6iii–7, and RF 12546-unstratified) while no. 990 (RF 9441; unstratified) is a tanged leaf-shaped blade. Nos 986 and 988 (RFs 4095 and 8973; respectively from Phases 6iii and 4ii) are incomplete tanged blades. The form of the arrowhead in Early and Middle Anglo-Saxon England is not well understood as very few have been found, although socketed leaf-shaped blades have been recorded in early Anglo-Saxon contexts at West Stow (West 1985, 124, fig. 241, 3–4) and in a Middle Anglo-Saxon context at Hamwic (SOU169, 895 unpublished, excavated by Southampton City Council).1 Two tanged leaf-shaped blades were found in a grave at Morning Thorpe, Norfolk (Green et al. 1987, 129, fig. 404, D and G), and Hamwic also produced a tanged leaf-shaped blade (SOU169, 257). The tanged form appears to be by far the most common in the Late Anglo-Saxon / Anglo-Scandinavian period (Ottaway 1992, 710–11).

No. 989 (RF 8982; Phase 4ii) is a socketed blade with a rounded tip, on which the edges angle outwards slightly at the base (FIG. 3.1). It is similar in form to some Early Anglo-Saxon spearheads, notably Swanton’s Series H, and it is likely to be no later than the 7th century (Swanton 1973, 101–14).

Nos 985, 987, and 992 (RFs 1005, 5243 and 11929) are fragmentary blades.

Chain Mail

No. 994 (RF 13865; unstratified) is a small lump of rings, possibly a fragment of chain mail.

Notes for section 3.2

One could also cite the 6th-century arrowheads from the Chessel Down and Boscombe Down Anglo-Saxon cemeteries on the Isle of Wight (Arnold 1982, 66–7). |

Catalogue

SEAX (FIG. 3.1)

984 |

Blade end missing. Back runs straight from the shoulder before sloping down towards the tip at 13°. Cutting edge pitted, but roughly straight. The blade has a pattern-welded core. Tang tip missing. L.247mm (FIG. 3.1) |

ARROWHEADS (FIG. 3.1) |

|

985 |

End of blade. L. 42, W.19mm |

986 |

Tang and base of blade. L.38mm |

987 |

Incomplete blade. L.60, W.12mm |

988 |

Stub of tang and incomplete blade. L.64, W.17mm |

989 |

Incomplete socket, and a blade with edges which are angled outwards slightly at the base, and a rounded tip. L.62, W.21mm (FIG. 3.1) |

990 |

Incomplete tang and incomplete leaf-shaped blade. Random organic material present. L.55, W.15mm |

991 |

Socketed, leaf-shaped blade, tip missing. L.98, W.13mm (FIG 3.1.) |

992 |

Incomplete blade. Convex faces, pointed tip. L.58, W.18, T.9mm |

993 |

Socketed, leaf-shaped blade. L.87, W.13mm |

CHAIN MAIL? |

|

994 |

Small lump of rings. L.33mm |

3.3 Writing and literacy-related items

by Tim Pestell, Michelle P. Brown, Elisabeth Okasha and Nicola Rogers

The styli by Tim Pestell

Introduction

Flixborough is remarkable for having yielded 20, probably 22, styli. They bear witness to literate ability among this settlement’s occupants during certain periods, in contrast to their possession of textual material which may have been written elsewhere. The following discussion aims to outline the use of these writing implements, their significance when considering the site at Flixborough, and their implications for understanding Anglo-Saxon literacy.

The stylus, a pen-like writing implement, was used to scratch letterforms into wax-filled writing tablets, called pugillaria or tabellae. Their use in the Anglo-Saxon world was directly derived from Roman traditions where, for drafting short-term notation or the study and contemplation of text, they were ideal tools of literacy. Because wax tablets were most usually made from wood, very few have survived from the early medieval world. They include the unique six-tablet, waterlogged example made of yew, recovered from Springmount Bog, Co. Antrim, Ireland (Armstrong and Macalister 1920; Webster and Backhouse 1991, 80; cat. 64) and a whalebone example from Blythburgh, Suffolk (Waller 1901–3).

It is difficult to be sure of the form taken by these wax tablets in the Anglo-Saxon period. In the Roman world, for which far more evidence exists, they usually consisted of two or three tablets, recessed on one side only, forming a diptych or triptych. The tablets were bound together by leather thongs passing through holes bored in their long sides. This is the format of the Springmount Bog examples, except here six tablets were used, the four interior ones being recessed on both sides. Preservation of the wax infilling in this particular find has also allowed the survival of an incised text, written in an Insular minuscule script probably no later than AD 600 (J. Brown 1984, 312). On all but the first page a vertical line divides the text into two columns, a format used in many Roman wooden writing tablets (Bowman and Thomas 1983, 37–40) ), and while a number of Early Medieval manuscripts depict tabellae in use, these are frequently stylised illustrations. Usually they depict a single tablet or a diptych, but a curious exception is the bat-like tablet with a handle at the base, shown in the Registrum Gregorii (Trier, Stadtbibliothek, MS.171). Sadly beyond this, understanding the use of wax tablets in the Anglo-Saxon world is severely compromised by the lack of surviving examples and some visual depictions (M.P. Brown 1994, 1–15). Our evidence for the employment of literacy on sites is instead limited to those writing implements used to create text.

Anglo-Saxon styli

At present, some 105 styli are known to have been recovered from Anglo-Saxon sites, while there are uncertainties over a few other examples. For instance, three from Blythburgh in Suffolk no longer exist (Waller 1901–3), while one from Santon Downham, also in Suffolk, is of uncertain date and possibly Roman. All four are excluded from statistical calculations. Additional examples of styli from sub-Roman or ‘British’ sites, again not included within the statistics, have been found at Cadbury Congresbury, Somerset (Rahtz et al. 1992); Dinas Powys, Glamorgan (Alcock 1963) and at Carraig Aille, Lough Gur, Co. Limerick, Ireland (Ó Ríordáin 1949). After these exclusions, 38 sites have yielded styli for a corpus of 104 examples, to which may be added an unprovenanced example (now in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford). Of the 38 locations, only 13 have been documented as having had Anglo-Saxon monasteria at them, leaving twice as many places with no such evidence. The 25 undocumented sites include seven of the type which some archaeologists have termed ‘productive’, that is, locations from which especial quantities of coinage and prestige metalwork have been recovered, typically through metal-detector use (Ulmschneider and Pestell 2003, 2–4). Recently, Blair (2005, 209 fn.116) has contested this interpretation, arguing many of these ‘productive’ sites are what he describes as ‘crypto-minsters’. However, this is simply one interpretation of these sites’ function, and one in turn partly influenced by the presence of material like styli. More recent finds have continued to expand the number of sites with single, stray, styli from those figures Blair used (based on Pestell 1999), so that of the 38 sites now known, 18 now yield 21 styli or 20% of the total known.

Classifying and dating Anglo-Saxon styli

Anglo-Saxon styli have frequently been accorded a Middle Anglo-Saxon date range, often upon very little secure evidence. It is apparent from the survival of stylus-use into the post-Conquest period that these writing implements might be expected equally in later deposits, and that stylistic developments may be anticipated. Disappointingly, the examples from Flixborough do little to enhance our understanding of their use in the Later Anglo-Saxon period. Of the 22 styli recorded from Flixborough, seven (one-third) were not even stratified. Even with the two-thirds of the assemblage which can be accorded a context, the high degree of finds residuality within features (often dumps) makes it difficult to create an accurate chronological sequence for different classes of stylus and therefore to help establish a typology.

The classification system currently being developed (Pestell, in prep.) is based upon the shape of the eraser, as it is this element which principally defines the tool as a writing implement rather than any other object, most notably a dress pin. Styli have a wide variety of eraser shapes, but they may be broadly categorised into ten classes. The styli from Flixborough include examples from five of these, the majority of which are the most simple Class I and II types, with 14 and possibly 15 examples, that is, nearly two-thirds of the site total. Class I styli feature a plain, undecorated, eraser extending from the shaft in a gentle outward curve. The eraser may be divided from the shaft by a collar of decorative bands. Class II styli have similarly undecorated erasers, but with a definite straight-edged triangular shape. They are always divided from the shaft by a collar with two possible exceptions, the iron styli nos 1004 and 1016 (RFs 465 and 4316) from Flixborough. Naturally, the similarity in shape between the two classes can make precise definition difficult at times, especially for those styli made of iron and now corroded.

The remaining Flixborough styli include examples of Class IV, characterised by proportionately short D-shaped erasers; Class VI, defined by their decorative treatment (in most cases of an applied foil mount, although two examples from Whitby, and one from Pentney, Norfolk, have decorative treatment cast or applied directly to the eraser); and Class VII, distinguished by the curved axe-shaped erasers. This latter class is further subdivided into VIIa and b, the latter having not one but two outward flanges; Flixborough has yielded one example, of Class VIIa.

The Flixborough styli

Flixborough is important for the study of Anglo-Saxon styli for three principal reasons. First, it has yielded the largest single assemblage of these writing implements from any early medieval site in the British Isles. Second, the excellent stratification of the site raises the prospect of dating several examples accurately, allowing chronological distinctions in a future typology. Finally, many of the styli excavated were of iron, providing an important corrective to the predominant picture of these implements being of copper-alloy.

With some 105 extant Anglo-Saxon styli, the 22 recovered in the Flixborough excavations represent over a fifth of all examples. This is a remarkable assemblage and it should occasion no surprise that many of the styli find parallels with examples from a variety of other sites. Despite this, there is a striking homogeneity among the Flixborough examples. Two-thirds belong to the simple Classes I and II, but within this are themselves very simple. Several more decorative copper-alloy styli also shared certain characteristics, most importantly four having faceting of the lower shafts. This is a design element found on only 15 Anglo-Saxon styli, meaning the incidence of this embellishment is high when it is remembered that there are only seven non-ferrous styli from Flixborough.

Faceting is clearly an extra decorative element and is also employed on the upper shaft, immediately below the eraser, on two other styli – one each from Barking, Essex and Coddenham, Suffolk. That this extra decorative element appears to reflect a higher-status object is apparent not simply from the extra work involved in the manufacture, but also when considering other features of these styli. One, from Flixborough (no. 1006; RF 6143; PL. 3.2) is of solid silver, while two examples, again from Flixborough, are of Class VI, that is, where the eraser has been embellished with a foil mount. Similarly, the two facet-stemmed examples from Brandon are of Class VIIb, where the erasers are shaped in an elaborate flaring double axe-head design (Webster and Backhouse 1991, 86–7, cat. 66r-s). In these, especially Brandon SF 4993 (ibid., cat. 66r), the stylus has transcended a purely functional design. There may once have been more facet-stem styli, as only the evidence of the non-ferrous examples survives, but this design element occurs at only 11 of the 38 known stylus-producing sites. Of these, four are documented religious sites (Barking, Bradwell-on-Sea, Whitby and Whithorn), while the remainder have no such definite evidence. With the exception of Bradwell (Essex), South Walsham (Norfolk) and Norton Subcourse (Norfolk), all these sites have produced wealthy artefact assemblages, and elaborate styli might be anticipated. The high number of styli with faceting from Flixborough – and indeed two of the three found at Brandon – is of interest, and it will be instructive to see whether future finds with this element continue to enjoy other forms of elaboration too.

There are other individual elements within the Flixborough assemblage which share similarities: for instance, the point of silver stylus no. 1006 (RF 6143) is demarcated by two small grooves. This same detail, which would appear to have no practical function, reappears on two other Flixborough styli, nos 1011–12 (RFs 7518 and 11568), the elaborate Class VI examples. These three are not simply more ornate styli, but share a fundamentally similar formal composition. All three use a collar beneath the eraser, of two rings, a spherical bulging, two more rings and then a narrow baluster-shaped upper shaft. This is divided from the faceted lower shaft by a second collar; nos 1006 and 1011 (RFs 6143 and 7518) use a spherical bulge, no. 1012 (RF 11568) a wide scooped ring. The use of the ‘ringed point’ is not seen in any other Anglo-Saxon styli, with the possible exception of iron stylus SF 1430 from Barking Abbey, which is otherwise very different in overall composition. Again, therefore, there is an elaboration in detail associated with styli that are distinct from ‘run-of-the-mill’ examples, in a formula presumably employed by the same workshop, and possibly the same metalworker, supplying Flixborough.

One stylus is of interest when considering the assemblage as a whole. No. 1016 (RF 465) is unusual in having a hole piercing the lower end of the eraser. Many styli have close formal similarities with Middle Anglo-Saxon dress pins in the use of faceting, collars and shaft rings. Throughout, the defining characteristic of a stylus is the presence of a prominent eraser. The occurrence of a stylus with a hole in this eraser is, though, fundamentally similar to many styliform pins with pierced heads, often of a Middle Anglo-Saxon date. When, therefore, does a styliform pin become a stylus? It would be futile to attempt any rigid definition. Rather, the overall look of an object will essentially remain the key. In the case of Flixborough no. 1016 (RF 465), the definite Class II triangular shape of the head is most certainly eraser-like, suggesting a stylus. Only two other artefacts suggested as being styli have such a piercing, sf 2279 from Winchester, catalogued as a ‘possible stylus’ (Biddle and Brown 1990, 741), and the stylus from Norton Subcourse, Norfolk. If these are in fact pins, then what of the Flixborough find? It too may be a styliform pin, but it is equally possible that this is a stylus which has subsequently been modified by the drilling of a hole. This is almost certainly the case with the Norton Subcourse example, and in either case, a close relationship is suggested between pins of this period and styli. Not only might it be possible that styli were on occasion worn, constituting a powerful means of displaying one’s literate abilities to a wider audience, but on occasion pins too could have been pressed into service as styli.

Dating

The dating of styli continues to be problematic, with ‘Middle Anglo-Saxon’ attributions frequently being applied. The good stratification at Flixborough allows several plain examples to be given more accurate dates to complement their more decorative counterparts: for instance, iron stylus no. 996 (RF 10349) was incorporated into the surface of a Phase 3bv dump (6304) of the late 8th to early 9th century. Stratification similarly shows silver stylus no. 1006 (RF 6143; PL. 3.2) to have been manu-factured no later than the early to mid 9th century, as it was found within a Phase 4ii deposit of the middle decades of that century (dump 5503). It has already been mentioned that no. 1006 (RF 6143) has stylistic similarities with the copper alloy stylus no. 1011 (RF 7518), also found in a Phase 4ii dump – 3758; and stylus no. 1012 (RF 11568), incorporated into the surface of 3bv dump 6235, which like dump 6304 formed the activity surface of Period 4 within the excavated area (see Volume 1, Ch. 4). The incorporation of styli into the surface of deposits dating from the late 8th or early 9th century makes it possible that some were 8th-century products. The three examples nos 1006 and 10011–12 (RFs 6143, 7518 and 11568) have baluster-like upper shafts (PL. 3.2) not dissimilar to the architectural balusters found in excavations at Jarrow Abbey or in situ at St Peter’s church, Monkwearmouth (Webster and Backhouse 1991, 148–50, fig. 9 and cat. 109).

The three styli with foil appliqués provide more readily-datable stylistic elements. Two have interlace ribbon ornament, that on 1012 symmetrical, although of slightly crude form, and that on 1013 a fatter ribbon but better balanced overall. They take as parallels a similar foil-applied stylus from Whitby (Peers and Radford 1943, 64 fig. 15.7) which is of late seventh or eighth century date (Webster and Backhouse 1991, 142 no. 107c), and a recently-discovered stylus from Pentney, Norfolk, with an integrally-cast design on the eraser, again of eighth century date (Gurney 2006, 119 fig. 15d). The third Flixborough eraser with a foil appliqué is of more sophisticated design, portraying a stylised long-necked beast, entwined within an interlace ribbon of late eighth-century date. Taking its cue from contemporary Mercian metalwork, this is by far the most elaborate eraser in the Anglo-Saxon corpus and reflects the status of this particular piece. Together, these erasers emphasise an eighth-century date for those styli capable of stylistic analysis. By contrast, it will always be more difficult to suggest date ranges for the manufacture of the many plain iron styli from Flixborough.

As described at the outset, Anglo-Saxon styli are the direct heirs of a Roman tradition. Although the ‘classic’ Roman stylus is of a fundamentally different design from its typical Anglo-Saxon counterpart, both periods have produced examples with close similarities. Nowhere is this seen more clearly than in the case of iron styli which are frequently very simple, and in which corrosion can mask stylistic details. This is particularly true for Class I and II styli, where the form of the eraser is both simple and closely related; Roman styli very similar to Anglo-Saxon examples are illustrated in Manning 1976 (e.g. fig. 21, nos 102, 108 and 109). With residual Roman pottery and other material at Flixborough emerging from dump deposits in Phase 5b (late 9th to early 10th century), the possibility exists that some of the simple iron styli from the site are of Roman date. The frequent occurrence of styli, usually of iron, on Roman sites does nothing to mitigate against this possibility. However, the quantities of Roman material on this site are relatively small, and their significance in the excavation area lies chiefly in showing the deposition of reworked material, either derived from elsewhere on the site, or imported onto the site with building materials.

If the possibility of a Roman origin is at least remote, the potential for Later Anglo-Saxon styli at Flixborough is far stronger. Stylus use continued well into the 12th and 13th centuries, with erasers developing into T-shaped bars (see for instance Armstrong et al. 1991, 136–7). The difficulty is that the ornate, and therefore more immediately datable Middle Anglo-Saxon styli (typified by the Class VI erasers, such as Flixborough nos 10011–12: RFs 7518 and 11568) do not seem to appear later; certainly, there are no examples, to this author’s knowledge, employing later ornamental motifs. One explanation is that the elaboration, or perhaps even the excesses, of the Middle Anglo-Saxon period gave way to a fashion for increasingly functional, plain examples. Indeed, it may not be completely in-appropriate to point out that of those few styli stylistically datable to the 8th century (nos 1006, 10011–14; RF 3775 unstratified, and RFs 6143, 7518, 11568 and 12268), three were found in deposits dated to between the end of the 8th and mid 9th century, and one was unstratified. Only no. 1013 (RF 12268), the iron stylus with a silver foil mount (PL. 3.3), was found in a later deposit (12270 from Phase 5b, dating from the late 9th to early 10th century). This could suggest that the many other examples of simple and stylistically undatable design might have been manu-factured later, and not all need be residual elements in deposits from Periods 5 and 6.

Potentially, therefore, Flixborough provides evidence for stylus use in the Later Anglo-Saxon period. Notwithstanding the difficulties in using manuscript illustrations as evidence for contemporary material culture, as opposed to the simple copying of earlier exemplars (Carver 1986), styli with simple Class I and II erasers can be seen in late 10th- and early 11th-century manuscript illustrations, for instance in the Benedictional of St Æthelwold, c.970–80 (BM Add MS 49598 fol. 92v); and the early 11th-century Bury Gospels (BL Harley MS 76 fol. 8). If these do indeed depict contemporary objects, simplicity of design may have ensured longevity. Thus, some Flixborough styli of these classes, although in deposits including earlier, residual material, may be near-contemporary with the date of the context. This would make Flixborough one of the few sites with known Late Anglo-Saxon styli. Other instances of Late Anglo-Saxon deposits yielding styli include two, and a possible third, from York (Ottaway 1992, 606–7, nos 3010 and 3011; Tweddle 1986, 189 and 192, no. 1252); two from Winchester (Biddle and Brown 1990, 741, nos 2280 and 2281); and two probable examples from Canterbury (Radford 1940, 506–7, nos 1 and 2). The difficulties surrounding this question aptly sum up many of the problems with the Late Anglo-Saxon material at Flixborough, and the more general observation that this period seems to see a reduction in the conspicuous consumption of wealth expressed through decorated, non-ferrous metal objects (Loveluck 2001, 118–19).

In conclusion, the stratification at Flixborough, while excellent, has failed to provide a radical progression in the creation or refinement of a workable typology for Anglo-Saxon styli. If this difficulty is a source of disappointment, a more positive approach is possible through the observation that Flixborough has not simply the largest stylus assemblage yet recovered in the British Isles, but the largest number and proportion of iron styli within an assemblage.

Iron styli

It is clear that iron styli were once far more common. In part, the overall numbers and proportion have been made to appear smaller by the increase in stylus finds made through metal-detection; some 31 styli, or 29.5% of the known Anglo-Saxon total have been found in this way. A further six copper alloy styli have been discovered as stray finds (those from Blythburgh, Suffolk, now lost; those in the Ashmolean Museum and the Museum of London; and a stylus from Sudbourne, Suffolk). The absence of iron examples found by metal-detection is directly related to the practice of discriminating against this material during normal metal-detector use; the most obvious corollary is that all new examples have been of copper-alloy. This seriously distorts the quantity and proportion of these writing implements known in other materials. Examples of iron styli are known from eight sites other than Flixborough: Barking and Bradwell-on-Sea, Essex; Bury St Edmunds, Ipswich and West Stow, Suffolk; Sedgeford, Norfolk; Winchester and York. All are from excavations and hint at the likely frequency with which this material was once used for these implements. The total of 28 known iron styli represents 26.6% of the total corpus, but of these, 15 come from Flixborough (that is, 53.5% of all known iron styli or 14.3% of all Anglo-Saxon styli). The Flixborough assemblage, therefore, is of fundamental importance for our understanding of the use and manufacture of these implements of literacy.

Analysis of those styli recovered from excavated assemblages, 19 sites yielding 72 styli, shows a proportion of 1.39 to 1 of copper-alloy to iron styli. This is likely to be a far more reasonable ratio than suggested by the full corpus total, yet at Flixborough itself, there were over twice as many iron to copper-alloy examples (15 and 6 respectively). The use of far more ferrous than non-ferrous styli should not be surprising. Most immediately, iron was clearly favoured for these objects in the Roman period and in deriving from antique traditions, the same material might be anticipated for Anglo-Saxon examples. The overwhelming majority of Roman styli found in modern excavated assemblages appear to be of iron, although many examples in museum collections, typically from antiquarian investigations and stray finds are of bronze, apparently having received preferential recovery and retention (Manning 1976, 34). This is exactly the same bias towards copper-alloy that may well be the case for Anglo-Saxon examples. The general preference for iron styli in the early medieval period is also suggested in our few textual sources. In Prudentius’ Crowns of Martyrdom, IX, ‘The Passion of St Cassian of Forum Cornelli’, the martyr Cassian is described as having ‘a thousand wounds, all his parts torn’, a consequence of his pupils ‘stabbing and piercing his body with the little styles with which they used to run over their wax tablets’ (Thomson 1961 ii, 223). The material of these tools is twice mentioned, ‘others again launch at him the sharp iron pricks’ and ‘you yourself as our teacher gave us this iron’ (ibid., 225 and 227). An Anglo-Saxon example appears in Aldhelm’s riddles, written at the end of the 7th century. In describing writing tablets in riddle 32, he uses the phrase ‘An iron point / In artful windings cuts a fair design…’ (Pitman 1925, 19). It may be that the Flixborough assemblage represents a more accurate picture of stylus use than many other excavated sites.

The context of stylus use

As we have seen, Flixborough has yielded by far the largest single assemblage of styli from any early medieval site in the British Isles; the next largest collections are from Whitby, the old excavations of which yielded 12 examples (Peers and Radford 1943); Bawsey in Norfolk, where metal-detection has recovered seven; and Winchester, where six were recovered in the extensive urban excavations (Biddle and Brown 1990). Following received wisdom, this might lead to the proposition that the Flixborough styli demonstrate the clerical or perhaps monastic nature of the settlement. This explanation has often been applied uncritically, but the simple equation of these finds correlating with monasticism is no longer tenable. Instead, a far wider range of interpretations can be made.

First, the entire question of lay literacy has been more widely explored by scholars in recent years. It is now clear that literate abilities were far more widely available within secular society throughout Anglo-Saxon England, and similarly on the Continent (Kelly 1990; McKitterick 1989). Not only were the first Anglo-Saxons literate, bringing with them a runic alphabet, but text was also important enough to be employed on sceatta coinage from the mid to late 7th century (Rigold 1960 and 1977). Of course, we must certainly include the caveat that the term ‘literacy’ probably disguises a whole raft of abilities and levels at which the ability to write was practised, ranging from accomplished biblical exegeses in classical Latin, to a basic or even poor understanding of text. Regardless, the transmission of instructions, records or ideas by text was clearly not some form of Christian secret code, exclusive to the clergy. The presence of styli advances this knowledge of literacy further, since using temporary texts provides a bridge between simple or short transmissions of information, and more intense compositional work evidenced in manuscripts. It is this sense of ‘literacy’ with which we are most familiar in our own society.

What documentary references we do have show examples of secular literacy resting with figures in the upper echelons of society. As brief examples, Bede described two 7th-century kings, Sigeberht of East Anglia and Aldfrith of Northumbria, as doctissimus or ‘very learned’, while nobles are recorded as sending their sons to Bishop Wilfred to be educated, their sons choosing whether to become warriors or priests when they had grown up (Kelly 1990, 59–60). This same secular influence has been used to explain the preservation of Anglo-Saxon poetry such as Beowulf, Waldhere and The Finnsburgh Fragment, reflecting a warrior society (Wormald 1978).

Perhaps as important is the symbolic power of literacy, ‘a mentality through which power could be constructed and influence exerted’ (McKitterick 1989, 320). This is an aspect probably extending back to the writing of runic inscriptions, which have been seen as both cryptographic and a professional skill (Lerer 1991, 167). Still further back, the ability to read and write had an importance in the Roman world where the ‘correct’ understanding of grammar and literature had been essential as a social marker indicating membership of the ruling caste, rather than developing a simple literate ability (Heather 1994).

This social dimension provides a convenient point of departure for considering further the materials from which styli were manufactured. The presence of styli on very many Roman sites reflects not simply a widespread access to literacy, but the essentially functional view taken of writing implements. Most were made of iron, with little embellishment either with other metals (a few instances have decorative inlays of copper-alloy) or in shape. The presence of so many iron styli at Flixborough might similarly be taken to imply a more functional attitude to literacy relative to the use of copper-alloy examples: Little wonder that St Cassian’s pupils learned to write using iron styli. If the picture from the Flixborough assemblage is more representative of the wider situation prevailing in Anglo-Saxon England, it seems likely that these writing implements were also once more common.

A principally functional view of iron styli might also be understandable in the light of Flixborough’s non-ferrous examples. Of the seven copper-alloy and silver styli, most have elements which may be interpreted as more decorative, and therefore, deliberately erring away from the purely practical, into one in which literacy or the literate abilities of the stylus owner are promoted to a more symbolic or status-based level. This is seen nowhere more clearly than in the case of Flixborough’s silver stylus, no. 1006 (RF 6143). We have similarly seen the elaboration of two copper-alloy Flixborough examples with foil mounts (nos 1011–12; RFs 7518 and 11568); the use of decorative octagonal faceting to the bottom of four Flixborough stylus shafts; and the decorative Class VIIa axe-shaped eraser of no. 1014 (RF 3775). If these were our only examples of elaboration, we would be in a stronger position to declare a difference in use or ownership between iron and non-ferrous styli. Flixborough has, however, iron stylus no. 1013 (RF 12268) whose silver foil mount on the eraser fuses elements of the simple iron styli with the decoration of copper-alloy examples. It also suggests that others may once have had such mounts. This fusion suggests that we need to be wary of viewing all iron styli simply as workaday tools. The fact that an iron stylus with an interlace-decorated foil mount was also recovered from Barking Abbey (Webster and Backhouse 1991, 90, cat. 67k), and that the suggested iron stylus from Parliament Street, York, had a tinned finish reiterates this (sf 1252; Tweddle 1986, 192). Evidently, even with iron styli there was a diversity of elaboration and value attached to these tools.

Less clear is the way such differences were perceived among the Anglo-Saxons themselves. The sheer paucity of styli in Middle and Later Anglo-Saxon England, in comparison to the numbers of Roman examples, shows that overall they were neither common nor used by large numbers of people in society. Instead, they are largely restricted to sites of known ecclesiastical origin (as we might expect) or those with evidence for high-status activity. In either case, the context would allow for styli of high elaboration and expense, where statements of literate ability could be united with expensive tools that transcended practical needs.

These observations present an obvious dichotomy because most styli, and many from Flixborough in particular, are very plain, ordinary examples. Very different users and uses for them are likely. The most eye-catching, elaborate styli were shiny items that were meant to be seen. In an ecclesiastical context this may have meant their use with tabellae, forming diptychs, perhaps preserving the names of those for whom special commemorative prayers may have been due. Given the elaborate carving of diptychs or triptychs in the early medieval period, it would be easy to imagine the silver stylus from Flixborough forming a matching accoutrement to such a piece, positioned on an altar.

It is possible that styli had an additional literary association as pointers used in the reading of manuscript text. There is only limited evidence for such a suggestion, but it is interesting to note the presence of many manuscript glosses up to the 11th century being ‘personal ones made at the moment of reading and scratched unobtrusively with a stylus’ (Parkes 1997, 3). This suggests individuals having a stylus to hand when reading. The use of book pointers has been most extensively argued for in the interpretation of objects such as the Alfred and Minster Lovell jewels as æstels. There is an extensive literature on this thorny identification (Keynes and Lapidge 1983; Harbert 1974; Howlett 1975; Hinton 2008). While it takes little imagination to picture an ornate gilded stylus being used to help an ecclesiastic read in full view of others during a service, we may do well also to imagine the accoutrement of a self-indulgent secular aristocrat reading or in private devotion.

If we have a ready context for these elaborate objects at the upper end of the social scale, it should be unsurprising to see individuals at both intermediate and lower ends of the same spectrum perhaps using an iron stylus with elaboration, or a plain copper-alloy example, such as Flixborough examples nos 1008 and 1000 (RFs 12268 and 4762). Either may have been treasured personal possessions for those with less wealth, while plain iron examples could have been working items perhaps shared in an everyday working environment, yet still found within a restricted circle of users with literate abilities.

If the variety of materials employed in stylus manu-facture illustrates the wide uses and social resonance of these tools, it may be instructive to return briefly to examine what types of text were written on wax tablets. Only that from Springmount Bog has been found with a readable text, in this case of passages from Psalms 30–2 (Armstrong and Macalister 1920). This Irish example might suggest literacy as an ecclesiastical preserve. The Blythburgh tablet is of little help, for though it preserves letter-forms scratched through the wax into the tablet’s bone surface, they cannot be read. Intriguingly though, they show all the identifiable characters to be runic, but in Latin word-forms (Parsons 1994, 222). This is analogous to the observation of Thomas Bredehoft that at least two Latin inscriptions on Anglo-Saxon objects use fecið rather than fecit, implying knowledge of the writing of vernacular characters (Bredehoft 1996, 107).

If we look back to the Roman use of wax tablets, an interesting picture emerges. The term most frequently applied is pugillaria, usually used to refer to notebooks, derived from the word to mean small tablets easily held in the hand (Bowman and Thomas 1983, 43). Not only is this term’s use frequent in Roman sources, it is the same term Aldhelm used with which to title his riddle (Pitman 1925, 18–19). Their use in the Anglo-Saxon world has been interpreted consistently as that of short-term notation of text, perhaps in spiritual meditations of biblical passages, as potentially suggested by the Springmount Bog tablets. Yet for the Romans, the vast majority of writing tablets that have survived were used to record legal and monetary transactions (Bowman and Thomas 1983, 33; Tomlin 1996). As such, the recording of transactions might be said to have represented medium- to long-term preservation of text. The picture of a longer-term textual use, fundamentally secular and business-based in the Roman world, forces us to acknowledge the variety of Anglo-Saxon audiences who might potentially have owned and used wax-tablets. With this, we may return to the question of the ownership of styli and examine further the contexts for their use.

The most frequently cited application has been for learning to read and write, or for writing sections of text for private contemplative study. Both have been anticipated as showing an ecclesiastical element, either through use in a monastic school or for clerical devotion, but this need not be the case. The commitment of King Alfred to educating himself and the attempts by Charlemagne to learn to write, to the extent of keeping writing tablets under his pillow, caution us against this (Keynes and Lapidge 1983; Thorpe 1969). Instead, the basic raison d’être of the wax-filled tablet in the Roman world may have been equally applicable in that of the Anglo-Saxon, for the maintenance of records and administrative tasks. The fact that the majority of the Flixborough styli are not only plain, but of iron, does much to suggest that this functional task might have been the primary use of literacy within the settlement, and one which continued into the Late Anglo-Saxon period.

This proposition may be pursued further. It has already been pointed out that of those 38 sites with a provenance for Anglo-Saxon styli, only 13 have documentary references leading to the identification of the sites as ecclesiastical or ‘monastic’. This not only leaves the majority of stylus-producing find-spots with little or no evidence for being an ecclesiastical preserve, but it also includes a number of sites for which there is no evidence of a communal ecclesiastical component. Thus the finds from Crimplesham, Grimston, Sedgeford or Tibenham in Norfolk, or Otley and Santon Downham in Suffolk, suggest that styli were once in more widespread use in Anglo-Saxon society. It is surely no coincidence that this cluster of finds from East Anglia lies in the same region where liaison between metal-detectorists and archaeologists has been strong for many years. The distribution of styli in East Anglia may well be representative of the use and loss of these objects in other areas too. While these finds could be argued to show clergy patrolling the countryside, it might be questioned whether this was always on ecclesiastical business, or was rather ‘clerical’ work for secular masters – people who we increasingly realise had literate abilities, too.

Sedgeford in Norfolk is of more than passing interest. Two styli have now been recovered from excavations on the site, the same total as from the known and well-documented monastic settlements of Bradwell-on-Sea, Canterbury and Jarrow, and surpassing the single-stylus finds at a number of other documented ecclesiastical sites. Sedgeford has no evidence for any former monastic or ecclesiastical importance, although in the Late Anglo-Saxon period it possibly acted as a secular estate centre. It is this aspect which brings it into direct dialogue with a number of other high-status sites, most notably Flixborough, but also Brandon in Suffolk, and Bawsey and Wormegay in Norfolk (Pestell 2003, 133–7). It has most commonly been the literate nature of the occupants of these sites that has encouraged an ecclesiastical component to be advocated. Yet, if we take into account the radical differences in the likelihood of secular documents surviving from this period, which are minimal in contrast to some contents of monastic libraries, the presence of styli on these sites might as easily be seen as a standard element of royal, aristocratic or high-status settlement administration.

In following this line of discussion, there is a notion that styli do not appear in urban contexts or more precisely, at emporia or wic sites. There are, to my knowledge, no styli known from Hamwic for instance, despite extensive excavations there. What evidence, therefore, is there for secular use in the context of trading or commercial activity? We may respond in two parts. First, it is incorrect to assert that there are no styli from any urban centres. York, Winchester and Ipswich have all yielded examples, and those from Winchester and York have been excavated from a variety of contexts. For instance, five styli of more or less certain identification were found at Brook Street, Winchester, although their dates of use are not certain; they were deposited in 10th-, 11th-, and 12th- to 13th-century contexts (Biddle and Brown 1990, 741–2). Three, and possibly four, were recovered from Parliament Street, Coppergate and Clifford Street, York (Tweddle 1986, 192; Ottaway 1992, 606–7; Waterman 1959, 81–3). Only one Anglo-Saxon stylus from York comes from a certain religious site, namely the excavations beneath York Minster (I. H. Goodall 1995, 484–5).

Ipswich provides a more curious instance. Here, a stylus was discovered buried with an unsexable, adolescent individual in grave 4269, within a cemetery at the Buttermarket site. The body has been radiocarbon-dated to Cal AD 645–680 at 95% confidence (Scull forthcoming). The iron stylus was of plain Class I form, very similar to the Flixborough example no. 1003 (RF 11238). It was buried at the waist with traces of mineralised leather adhering, suggesting that it had been carried in a pouch hung from the belt. Since the cemetery appears to be that of a trading community, in which several individuals appear from their grave-goods to be continental, Ipswich may provide an instance of a book-keeper.

Perhaps more pressing is to question the likelihood of finding evidence of administrative records being made on sites with possible craft-working quarters, and with industry based on small, probably familial, workshop practices. Their current absence might once again suggest that it is the larger, higher-status sites such as Flixborough that might be expected to produce styli. Only the larger administrative centres with developed bureaucracies and centralised control might be considered likely to have the infrastructure, staff and basic need for such literate practices.

The foregoing discussion has attempted to provide a wider context for the presence and use of Anglo-Saxon styli. Above all, it has tried to show that despite the limited evidence for literacy in secular society (a phenomenon difficult to examine in our predominantly ecclesiastical sources), its extent and therefore the use of styli are likely to have been known by the aristocracy and others with specialist social roles. Stylus use has long been seen in simplistic terms, as a tool for ecclesiastics to write temporary texts. Instead, their use had deeper resonances and implications, perhaps the most important of which is that we can no longer afford to see them solely as ecclesiastical accoutrements. Undoubtedly, styli were tools that might be expected most often on religious sites, but this does not oblige us to interpret their presence in such a light, even in the numbers recovered from Flixborough. Indeed, we may do well to conclude, as did Lönnroth in his discussion of early Norse saga writing, that ‘it is perhaps not terribly important to know whether it was a monk or secular chieftain that held the pen … the important thing is …[the] close contact, perhaps sometimes a confrontation, but usually co-operation, between secular sponsors and clerical scribes’ (Lönnroth 1991, 10). This greyness may not seem terribly satisfactory to everyone, but it was only by co-operation with the secular elites, and their gaining of distinct advantages, that the pen was to become mightier than the sword.

Acknowledgements

For their help in my research into Anglo-Saxon styli, and for making examples available for me to examine, I am especially grateful to Leigh Allen, Steven Ashley, Paul Barford, Bob Carr, Helen Geake, Chris Loveluck, Andrew Rogerson, Mark Watson and Leslie Webster.

Catalogue

Introduction

The following is a basic cataloguing of the 22 definite and probable styli found in excavations at Flixborough, describing their various attributes, including material, dimensions and decoration. The styli are described according to the classification system being developed by the author (Pestell in prep.).

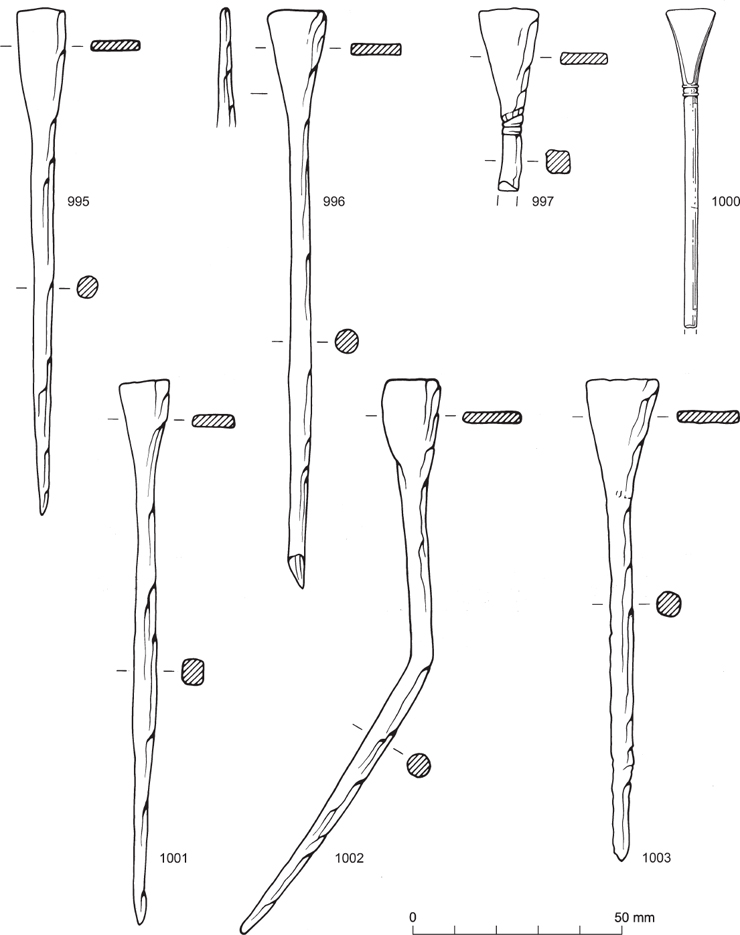

Class I Styli (FIG. 3.2)

IRON STYLUS – CLASS I

995 |

Class I stylus, corroded but retaining enough shape to show the eraser is long and relatively unpronounced, forming an oar-like shape. The corrosion makes measurement difficult, and so those taken are approximate. There appears to be no division between the eraser and shaft, and there is no indication of any decoration or mouldings on the shaft, suggesting a straightforward forged pin with the end flattened to form a larger area for the eraser. The shaft appears to be consistent in diameter for most of its length, before tapering off to form the point. |

IRON STYLUS – CLASS I |

|

996 |

A Class I stylus with a flat-ended eraser developing from the shaft simply by being flattened, rather than with a sudden curved ‘stop’ at the shaft end like on many other styli. Yet again, corrosion on the stem has caused blisters which mean that no decoration of moulded bands can be seen, and even the shaft diameter is difficult to measure accurately. The tip was broken off, making the original length impossible to determine, although the shaft does seem to show a slight taper. |

IRON STYLUS – CLASS I |

|

997 |

This corroded iron stylus is of Class I form, although the eraser head is well pronounced. The corrosion means that details are difficult to pick out, but it would appear that the eraser was divided from the shaft by a collar of at least one band, approx. 2mm wide. The eraser end appears to have been flat, with a slight nick out of one end. The eraser seems to flatten down from the stem on only one side, but this is probably due to it being both corroded and slightly bent. |

IRON STYLUS – CLASS I |

|

998 |

A corroded iron stylus of Class I form. The exact dimensions are difficult to establish since the object is now bent, corroded, and has its tip broken off. The eraser flanges directly from the short thickness, and so its exact length is somewhat subjective. The eraser end is not quite straight, although it has possibly been slightly damaged through corrosion. The eraser is created by flattening from the shaft thickness, and tapers evenly on both sides. Although corroded, the stylus shape is quite well preserved and there is no evidence that the piece ever had collars or other decoration. The shaft appears to taper down very gradually to the now-missing point. The shaft is approx. 2.5mm in diameter where the tip is now broken off. This piece is very small and in many respects feels more like a pin, but its small size is not dissimilar to other styli, for instance examples from Otley, Suffolk (OTY 020) and Bawsey, Norfolk (Webster and Backhouse 1991, 231, no. 188c). |

IRON STYLUS – CLASS I |

|

999 |

This end fragment has an eraser directly expanded from the shaft, in the manner of Class I. The eraser is quite slender in relation to its length; this appearance is compounded, as its length cannot be measured easily due to the lack of any collar rings at the end of the shaft. The shaft is corroded, and so a detailed appreciation is difficult, although it would appear to flatten slightly near the eraser on one side. The proportions of the eraser make it similar to those of Class VIII which are more oar-shaped, but this is clearly of Class I. Although corroded, the object has been conserved and it shows no evidence of having once had rings or collars to the shaft end. The corrosion makes it difficult to see precisely, but the eraser head appears to be flat-ended. |

FIG. 3.2. Class I and Class I/II styli in iron and copper alloy. Scale 1:1.

COPP ER ALLOY STYLUS WITH GILDING – CLASS I |

|

1000 |

A small, delicate and simple stylus, Class I. The eraser progresses directly and quite smoothly from the thickness of the main shaft, which is of a consistent circular cross-section. The eraser is demarcated from the shaft by a small collar of three bands, the central one of 1mm width, flanked by two smaller bands c.0.5mm wide. These bands are barely wider than the main shaft. The eraser’s end is slightly rounded in section, and the end edge slightly bowed. |

Class I/II Styli (FIG. 3.2) |

|

IRON STYLUS – CLASS I/II |

|

1001 |

A borderline Class I/II stylus that sits best in Class I at present. There are heavy soil/corrosion deposits over the entire object, making it difficult to determine its character. |

IRON STYLUS – CLASS I/II |

|

1002 |

This stylus has a large amount of concretion and blistering, hindering examination. The eraser is of a good triangular form and borders Class I/II. The corrosion makes it impossible to see whether there is any decoration, and has left a thick shaft, tapering to the point, which still survives. If the corrosion has not exaggerated the object too severely, this would have been a sturdy stylus. |

IRON STYLUS – CLASS I/II |

|

1003 |

A borderline Class I/II stylus. Corrosion makes it difficult to determine where the end of the eraser lies. The shaft is similarly corroded, but it is clearly very thick in comparison to most other styli (cf. no. 1004: RF 4316). In tapering outwards from the shaft, the stylus is best classified as Class I, although the triangular shape is quite strong. So far as can be determined through the corrosion, there is no decoration in the form of moulded bands or collars. However, there is a slight thickening in the middle of the shaft. The eraser has a straight, flat edge which does not appear to chamfer in when seen side-on. The stylus point, if not broken off, is very blunt in comparison to other examples, but this impression may have been exacerbated by the corrosion. |

IRON STYLUS – CLASS II |

|

1004 |

This iron stylus is too heavily corroded for any worthwhile analysis, except to say that the eraser seems large and broad and tending towards Class II. The shaft has no visible traces of decoration, but it appears to be complete to the tip. The shaft is very thick and tapers towards the point. This thickness is no doubt influenced by the extent of the corrosion, although a stylus now in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, also has a very thick shaft (Hinton 1974, 8, no. 2 and pl. IV). |

COPP ER ALLOY STYLUS – CLASS II |

|

1005 |

An extremely simple Class II stylus with a plain straight-edged triangular eraser joined to the stem by the collar 2.25mm wide, consisting of three narrow 0.75mm bands, slightly uneven in their circumference. The shaft is completely plain with a slight broadening in thickness tapering away to a point. A slight scratching on one side of the eraser is shiny and suggests gilding, but this is probably just a scrape made during recovery or conservation. The eraser tapers with a slightly rounded section ending at the collar. |

SILVER STYLUS – CLASS II |

|

1006 |

This is a Class II stylus, but one which shares many characteristics with others from Flixborough. Its bold triangular eraser is typical of Class II. Its corners are slightly rounded off, and in side view the eraser tapers towards the edge, giving a sharper chisel-end finish. The eraser is divided from the shaft by a collar with a small spherical bulge 2.5mm wide, flanked on either side by two small bands, each one approx. 0.75mm wide. The shaft is divided into two zones by a second collar, again featuring a spherical bulge flanked on either side by a pair of bands. The bulge is approx. 2.5mm wide, the bands each approx. 0.5mm wide. |

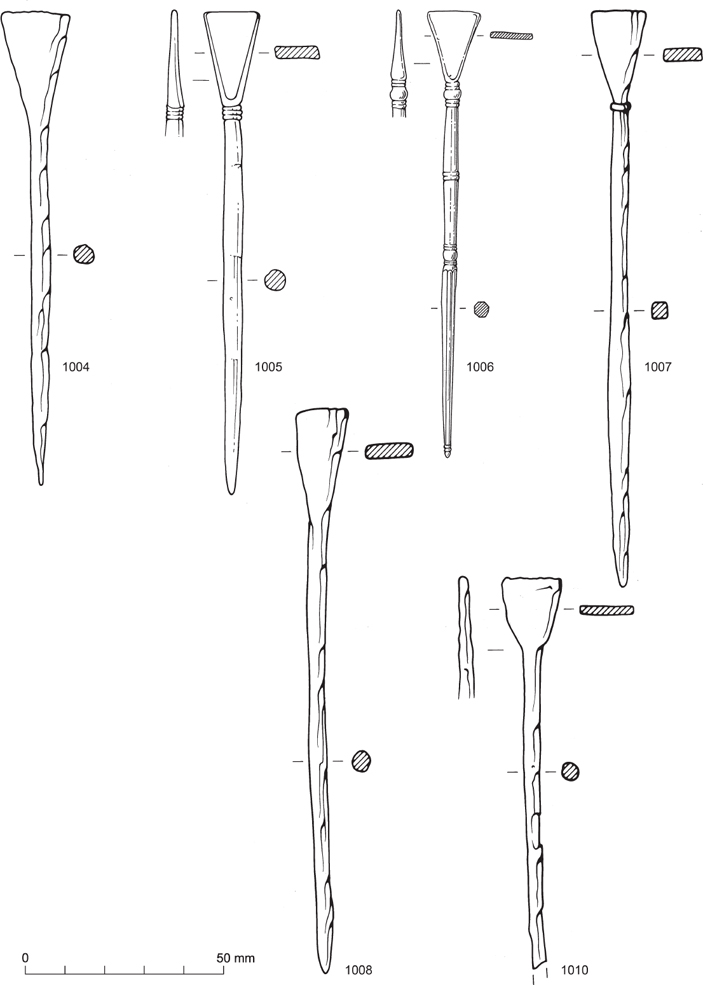

FIG. 3.3. Class II and Class IV styli in iron, copper alloy, and silver. Scale 1:1.

IRON STYLUS – CLASS II |

|

1007 |

A Class II iron stylus, the eraser well-preserved with a straight-edged end, the flat lateral sides tapering slightly in a wedge shape in long section. The edges of the eraser taper from the shaft in a straight line. The eraser is divided off from the shaft by a single band, approx. 1mm thick. The shaft is of circular section. |

Class IV Styli (FIG. 3.3) |

|

IRON STYLUS – CLASS IV |

|

1008 |

A very heavily corroded stylus that makes any identification and comments difficult. The eraser seems to be slightly oar-shaped and therefore of Class IV form. The stylus is slightly bent, but retains a pointed end. There is no decoration visible due to the corrosion, which also means that the recorded shaft diameter thickness and shape (circular at present) may not be totally accurate. |

IRON STYLUS – CLASS IV |

|

1009 |

This stylus is similar to Class IV in having a more rounded taper from the end of the eraser. The eraser itself can be measured only approximately, as there is no collar dividing it from the shaft. The end of the eraser is bent through about 45° and its end is now broken - so it might have once been a bit longer. The eraser is formed from the shaft thickness, tapering gradually, to produce an eraser that, as it survives, is quite thick. The shaft is quite squared off, although both attributes might be affected by the corrosion. Adding a large fragment, which has flaked off, back onto the eraser thickens the whole piece up quite considerably. |

IRON STYLUS – CLASS IV |

|

1010 |

A Class IV stylus of iron with the tip missing. This eraser is one of the longest in this class, but its rounded edges are clear despite the corrosion. The eraser is of a broad, rounded form, directly joining the top of the shaft with no apparent trace of a collar/bands. The eraser thins down from the stem, evenly on both sides. There is a reasonable amount of corrosion on the shaft, making it difficult to tell whether any former decorative bands or mouldings were once present, but there seems to be a slight thickening of the shaft to the middle and tapering toward the broken end. The rounded shape of the stylus takes as its best parallels a stylus from Whitby (Peers and Radford 1943, fig. 15, no. 5) and a metal-detector find from Otley, Suffolk (OTY 020), in private possession. |

COPP ER ALLOY STYLUS WITH SILVER FOIL MOUNT – CLASS VI |

|

1011 |

This elaborate Class VI stylus is, in its composition, fundamentally identical to no. 1012 (RF 11568) below, in having an interlace eraser panel, and shaft divided into two zones by collars with a smaller pair of bands in the bulging upper zone of the shaft. |

COPP ER ALLOY STYLUS WITH FOIL MOUNT – CLASS VI |

|

1012 |

An elaborate stylus of Class VI. The eraser is divided from the shaft by a collar consisting of a spherical bulge 4mm wide, flanked on either side by two narrow bands each approx. 0.8mm wide. The shaft is divided into two zones by another collar. The first length, of round section, is baluster-shaped, bulging up to 4.5mm in diameter. At its widest point, two bands are formed by the use of three grooves. The collar that divides the shaft is comprised of a concave central band 4mm wide, flanked on either side by two bands each about 0.75mm wide. The second section of the stem tapers to a point after a brief bulging, immediately beneath the collar. This section of the shaft is octagonal. The last 3mm of the shaft is divided off, a 0.5mm band just 2mm from the point tip, the band and the last 2mm tip being of round section. |

IRON STYLUS WITH SILVER FOIL MOUNT – CLASS VI |

|

1013 |

A Class VI stylus. The eraser is distinguished by the addition of a silver foil repoussé mount in which, within a triangular border line, is an 8th-century interlace design. The end of the eraser is unclear, and probably extended slightly beyond the end of the foil mount. There is no trace of there having been a moulded collar of bands to separate the eraser from the shaft, and as preserved, the shaft itself has no evidence of any decorative bands along its length. The shaft is also of a more or less consistent thickness with only minimal thinning before its broken-off end. The eraser is flat-ended with one corner lost through corrosion. |

COPP ER ALLOY STYLUS (GILDED) – CLASS VI |

|

1014 |

A well-formed stylus of copper-alloy, Class VII. The bell-shaped eraser has flat sides tapering off to an end which is bow-shaped, and chisel-ended in section. The eraser is connected to the shaft by a collar featuring two narrower bands, each about 1mm in width, then a longer, bulging band 2mm wide, followed by a further two 1mm wide bands. The bands can be seen to be slightly uneven from the side. The shaft has a neat octagonal section for the 57.5mm of its upper zone, before a further collar of two 1mm bands, a bulging 2mm central band, and two more 1mm bands. The final part of the shaft bulges slightly, before tapering away to a point 43mm further on. Traces of gilding survive on the collar bands nearest the eraser, suggesting that either this end, or more probably the whole object, was once gilded. |

Other (FIG. 3.4) |

|

COPP ER ALLOY STYLUS – FRAGMENT |

|

1015 |

This is a short length of shaft ending in a point that has been classified as a stylus, although there is little morphologically to confirm this, and it is unclassifiable: it could equally be the end fragment of a pin. Severe corrosion lumps/products adhere. The main interest of this piece is that it does not appear to have been snapped or broken, but cut, an angled edge going through most of the thickness before stopping at a flat-cut edge. |

1016 |

An iron stylus classified as Class II on the basis of its straight-edged eraser. As usual, corrosion makes it impossible to see whether there were decorative elements such as rings or collars, although what remains makes this seem unlikely. A band of heavy encrustation along the shaft compounds the difficulty. Conservation has suggested that this particular find is plated, although it is not clear with what, and no XRF examination has been undertaken. The stylus is unusual in two principal respects. First, it is very short, especially in relation to the size of its eraser. This may be because it has been cut down slightly from an earlier, longer, length. At 94mm, with a clear pointed tip, it is the shortest of the complete Flixborough styli and shorter than the vast majority of other Anglo-Saxon styli. In length, only an example from Fen Ditton in Cambridgeshire is close in length, and this seems likely to have been cut down. The second unusual feature is the hole drilled through the eraser, considered in more detail in the preceding general discussion. |

FIG. 3.4. Class VI styli in copper alloy and iron with foil mounts, and Class VII styli in copper alloy, and a copper alloy stylus fragment. Scale 1:1.

A decorated silver plaque, possibly from a book cover

by Nicola Rogers

Made of debased silver with mercury gilding, no. 1017 (RF 6767) is a slightly convex chip-carved sub-square plaque, one corner of which has been broken away; a rivet-hole in each side indicates the means of attachment (FIG. 3.5; PL. 3.5). Deep chip-carved interlace enmeshes a bi-ped with a pricked ear and an extended wing and back leg; interlace also pours forth from its mouth. The border and the beast are decorated with punched dots. Two-legged beasts became common motifs of decorated metalwork and manuscripts in the second half of the 8th century (Tweddle 1992, 1156–7) ), as well as in other media such as embroidered textiles, e.g. the early 9th century Maaseik panels (traditionally said to be from a chasuble made by Saints Harlindis and Relindis, and subsequently moved to the parish church of Maaseik / Maeseyck in Belgium: Webster and Backhouse 1991, 184–5, no. 143), and sculpture: see the 9th century cross-shaft from Croft on Tees, North Yorkshire (Webster and Backhouse 1991, 153, no. 115). The punching on the body and the border, the pricked ear, the wing and the two legs of the beast on no. 1017 (RF 6767) are all closely paralleled on the Witham pins – particularly the middle pin – a set which dates to this period (Webster and Backhouse 1991, 227–8, no. 184). The horned creature may also be seen as somewhat similar to the horned beast on the Ormside bowl (Webster and Backhouse 1991, 173, no. 134). As with the contemporary no. 25 (RF 5467; see Ch. 1.1, above), this plaque represents a fine example of decorative metalwork of the second half of the 8th century.

Metal rectangular or square plaques are often interpreted as mounts from book covers – see for example the early 9th-century gold plaque depicting St. John the Evangelist from Brandon, Suffolk (Webster and Backhouse, 1991, 82, no. 66a), and no. 1017 (RF 6767) may have had a similar function, although it has no obvious iconography indicating use on a religious item.

Catalogue

1017 |

Plaque, sub-square, complete apart from one corner which has broken off; chip-carved interlace incorporating winged two-legged beast with ?horn, angular snout, one leg extending behind, short front leg appears clawed; body decorated with punched dots, as is the square border which has a single rivet-hole in the centre of each side. Mercury-gilt all over, some worn away on edges. L.25, W.23.4, Th.1.1. (FIG. 3.5; PL. 3.5) |

The inscribed objects

by Michelle P. Brown and Elisabeth Okasha

with catalogue entries by Nicola Rogers

Two objects inscribed with text in the Latin alphabet were found during the excavations at Flixborough. The first to be found was the finger-ring illustrated in FIG. 3.5 and PL. 3.6. It was found in November 1989 as an unstratified find in topsoil. The second was the lead plaque illustrated in FIG. 3.5 and PL. 3.7. It was found in refuse dump 1728, dating from Phase 5b, overlying the demolished building 29.

The Finger-ring (no. 1018; FIG. 3.5 and PL. 3.6)

The ring is made of debased silver and measures 20.6mm in diameter. It is composed of a flat strip of silver, 7mm in width, the overlapping ends being secured by two rivets; it has a lentoid or lozenge-shaped bezel. The outer face contains some mercury gilding, but this has worn off around the edges, presumably during use of the ring. The outer face contains a text of deeply-incised letters, 4–5mm in height, formed with a V-shaped tool. The background to the letters is decorated with small punched ovals. The text is set completely round the hoop, with the initial cross overlying the joint. This indicates that the text was incised after the hoop was riveted.

The text reads (see Note 1) ±ABCDEFGHIKL. The B and probably also the cross are upside-down, presumably in error. The letter-forms are half-uncial, a script which was in use in manuscripts throughout the Insular period. Similar letter-forms occur on a number of inscriptions dating from the 8th to the 9th century (Okasha 1968, 321–8, Table 1b; Okasha 1992, 47, no. 194 and 56–57, no. 208).

Partial alphabets occur on other Anglo-Saxon inscribed objects. There is, for example, a small stone from Barton St. David, Somerset, containing the letters A to E (Okasha 1992, 41–2, no. 186) and a piece of leather from Dublin with the letters A to F followed by two illegible letters (Okasha 1992, 44–5, no. 190). These parallels suggest that the Flixborough ring was intended to contain a partial alphabet, and that we need not assume the loss of another ring containing the letters M to Z.

There are 17 other inscribed finger-rings dating from the Anglo-Saxon period (Okasha 1971; Okasha 1992, no. 204; and an example in private possession from Sleaford, Lincolnshire). They contain various different sorts of texts, but no other text on a finger-ring consists of any part of an alphabet. There are various possible reasons why a partial alphabet might be inscribed on a finger-ring. It could, for example, have been done to display knowledge on the part of the maker of the ring. It could also have been to raise the status of the ring, and hence of its owner, by association with literacy. Another possibility is that the ring served as a devotional mnemonic: abcedarial prayers in which supplications are arranged in alphabetic order marked by initials are found in some early 9th-century prayer-books, for example, London BL Royal MS 2.A.XX (Kuypers 1902, 200–25; M. P. Brown 1996)).

The finger-ring is dated to some time within the 8th and 9th centuries. Since it was an unstratified find, the ring lacks any precise archaeological context, but two other sorts of evidence confirm its dating. Firstly, the half-uncial script used is typical of this period. Secondly, of the 17 other Anglo-Saxon inscribed rings known, 10 are likely to date from the 9th century, or the 9th–10th centuries, while six cannot be more closely dated (Okasha 1971). The Flixborough ring is certainly to be dated to the 8th or 9th century, but there is insufficient evidence to date it more precisely within this period.

FIG. 3.5. A decorated silver plaque (possibly from a book cover), an inscribed silver finger-ring, and an inscribed lead plaque. Scale 1:1.

The lead plaque (no. 1019; FIG. 3.5 and PL. 3.7)

The plaque is made of sheet lead and measures 59mm in height, 117mm in length and 1mm in thickness. It contains twelve holes, presumably to attach it with nails to another, probably wooden, object. The nail holes vary between 1 and 3mm in diameter. Five of the holes are damaged in such a way as to suggest that the plate had been forcibly pulled off some other object. On the other hand, there is no sign of staining or corrosion around the holes, nor any sign of flattening of the lead around the back of the holes: both of these might have been expected had the plaque been actually nailed onto another object.

The face of the plaque contains four lines of text separated by four lightly incised horizontal ruling lines. The letters vary in height between 5 and 13mm, and generally do not touch the ruling lines. Many of the letters of the lowest line of text do, however, touch the ruling lines; moreover, these letters are small and seem to have been squashed in around the nail holes. All this suggests that the lowest line of text may have been incised after the rest, and that the plate may have originally been designed to contain only six names.

Beneath the existing text some traces of other marks are visible. When enhanced by xero-radiography these marks may be seen as letters, although they are not sufficiently legible to be read. It is possible that there was an underlying text which may have formed an initial stylus sketch for the existing inscription. It seems unlikely that the Flixborough text is a palimpsest, since it would be easier to melt down the lead, or use another piece of lead, and start afresh, rather than to re-inscribe over an existing text.

The text reads (see Note 1):

+ALDUINI:ALDHERI:

HAEODHAED:EODUINI:

EDELG/YD:EONBE/RECH[T]

EDELUI[I]N:

It consists of an initial cross, followed by seven Old English personal names: alduini, aldheri, haeodhaed, eoduini, edelgyd, eonberech[t] and edelui[i]n. The names alduini, aldheri, eoduini, and eonberech[t] are forms of the male names Ealdwine, Ealdhere, Eadwine and Eanbeorht respectively. The name edelgyd is a form of the female name Aeðelgyð. The name haeodhaed is probably a form of the male name Eadhaeð. The spelling aeod- for ead- is recorded; instances occur amongst the Old English names in Bede (Sweet 1885, 134–5, lines 40 and 72). An intrusive h is occasionally found before vowels (Sweet 1885, 139, lines 174–5). The name edelui[i]n may be a form of the male name Aeðelwine with the last two letters transposed in error. Alternatively, it could be a form of the female name Aeðelwyn, although the spelling of double i for y would be unusual.

The forms of the names can all be paralleled in the name forms of the Durham Liber Vitae and in the pre-Viking Northumbrian coinage (Sweet 1885; Smart 1987, 245–55). The spellings of the Flixborough names exhibit features associated with non-West-Saxon dialects of Old English. Examples include the monophthongs in ald- (two examples) and in -berech(t) (first e). Non-West-Saxon spellings might be expected if the composer of the text was from Flixborough or the surrounding area. The spelling of the names gives some linguistic dating evidence: the three instances of final -i for -e in the name-elements -wine and -here, and the intrusive second e in -berech(t), probably suggest a date before the end of the 9th century, although similar forms occur sporadically in the 10th-century Northumbrian glosses added by Aldred to the Lindisfarne Gospels and the Durham Ritual.

The script used is a hybrid (or high-grade) minuscule, a manuscript script using a mixture of uncial, half-uncial and minuscule forms. In the manuscript tradition, this script was enjoying increasing popularity as a formal alternative to half-uncials in southern England, during the late 8th and early 9th centuries. The closest manuscript parallels to the script are found in some Mercian charters of this date, for example, a charter issued by King Offa of Mercia in 793–6 (London BL Add. Ch.19790), and in the later manuscripts of the ‘Tiberius’ group, for example, the Royal prayer-book (London BL Royal MS 2.A.XX) and the Book of Nunnaminster (London BL Harley MS 2965; see also M. P. Brown 1996, 164–9). Close epigraphic parallels also occur on stones from Durham and from Yarm, North Yorkshire, both of which date from the 8th or 9th centuries (Okasha 1971, 65–6, no. 30; and 130, no.145). The evidence of the script and the language therefore suggest a date during the 8th or 9th centuries. There is, however, insufficient evidence to date the plaque more precisely within these centuries.

The forms of the ligatures and of the word-division symbols used in the Flixborough text can be paralleled in both manuscript and epigraphic texts. The word-division symbol used is a triple dot (a common Insular form of punctuation derived from the Irish system of distinctiones), which follows all the names except for the second and the fourth. The symbol following the second name, aldheri, consists of six dots, not three. This may have served to separate the first two names from the rest, perhaps to indicate that these people were of higher status than the others. There is no word-division symbol following the sixth name, eonberech(t). If, as suggested above, this name was originally intended to be the final one, this might explain the lack of symbol here; however, the seventh name, edelui(i)n, is also followed by a word-division symbol.

All the personal names in the text are recorded Old English names; many indeed are common names. None of the persons named can therefore be identified securely. The plaque was intended to be fastened to some other object, probably a wooden one. Since seven names are given, it seems unlikely that this object was a coffin (although the coffin of St. Cuthbert also contained relics of other subsequent saints, e.g. Oswald). The text could well have been commemorative, however, perhaps used to mark seven graves or to act as a sort of epigraphic Liber Vitae. Alternatively, it might have recorded relics or the remains of revered people such as the founders or worthies of a religious establishment.

Other than the Flixborough example, there is only one other inscribed plaque or plate from Anglo-Saxon England, discovered in six fragments at Kirkdale, North Yorkshire (Watts et al. 1997). There are twelve Anglo-Saxon lead crosses, most of them funerary crosses, including two from Lincolnshire (Okasha 2004).

Notes for section 3.3

1. |

The text is transliterated according to the following system: A = a legible letter A; A = a letter A, damaged but legible; [A] = a damaged letter where the restoration is fairly certain; A/B = a ligature of A and B; : = a word-division symbol. |

Catalogue entries by Nicola Rogers

(The following two entries are based on those prepared for Webster and Backhouse 1991 by Kevin Leahy. Dimensions are in mm. L. = length; W. = width; Th. = thickness; Diam. = diameter)

FINGER-RING

1018 |

Silver hoop formed from strip, ends overlapped and secured by two rivets whole mercury-gilded, gilding worn off on the edges. Decorated with incised letters of half-uncial form reading A–L (lacking J), letters deeply cut with V-shaped tool, small punched ovals scattered around and within inscription, upside down Latin cross separates beginning and end of inscription, and has been cut over the join. Diam. 20.6 Section W.7, Th.1.3. (FIG. 3.5 and PL. 3.6) |

LEAD PLAQUE |

|

1019 |

Sheet lead plaque bearing four lines of text which have been cut with a V-shaped chisel. Between the lines of text are four lightly incised horizontal lines used in setting out the letters. The individual words are separated by groups of triangular incisions. Underlying this is an earlier inscription. Around the edge of the plaque are 12 nail-holes ranging in size from 1mm to 3mm diameter. Five are damaged in a way which suggests that the plaque had been torn away from the surface – probably wooden – to which it was fixed. Distortion may have occurred during burial. |

3.4 Possible liturgical objects: Iron bells and bell clappers

by Patrick Ottaway

Bells