4 Building Materials and Fittings

The structural and stratigraphic evidence for the various buildings excavated at Flixborough is considered in detail in Volume 1 (see Loveluck and Atkinson, Chs 3–7), whilst their plan forms, reconstructions, and analogies with buildings of similar date from other sites in Britain and N.W. Europe are considered in Volume 4 (see the essays by Loveluck and Darrah in Ch. 3 of that volume). This chapter examines the artefactual evidence for these various structures.

The excavations produced a wide range of structural ironwork and fittings: clench bolts, roves, staples, collars, hinges, hinge pivots, and a variety of carpentry nails, rivets, studs and tacks. Many of the timber buildings yielded fragments of fired clay and daub, which were used both as a walling component, and as a construction material for ovens and hearths. Lastly, a few of the buildings were glazed, and this chapter includes a study of the glass quarries and lead window cames.

***

4.1 Structural ironwork and fittings

by Patrick Ottaway, with contributions by Lisa M. Wastling, Glynis Edwards†, Jacqui Watson and Ian Panter

Iron nail typology

by Lisa M. Wastling

1463 iron nails were found, 644 of which were stratified, representing 44% of the total.

344 stratified nails were assigned to seven types (A–G), based on the form of the head. These are as shown in the table at the foot of the page and are illustrated in FIG. 4.1.

Of the 537 stratified nails, where the form of the shank could be ascertained, 94% bore shanks of square cross-section; the remaining 6% were rectangular in section.

Types A, E and F could be used on nails or studs, although no complete examples of type E were recovered. A stud is generally taken to be a nail with a short shank and a head larger than c.25mm in width.

The overwhelming majority of nails were of type A, bearing a flat head. Most were of a size likely to be used in carpentry. When used, the nail was possibly hammered into a bored hole, of narrower dimensions than the nail shank, in order to prevent the splitting of the wood, or lessen the force needed to penetrate dense timber.

FIG. 4.1. Iron nail types A–G. Scale 1:1.

Type A nails have been the most universally used hand-wrought nails from the Roman period onwards. The heads were possibly formed with the use of a nailing iron, such as the Roman examples illustrated by Mercer (1960, fig. 204), or using a punch or nail-heading hole on an anvil, which can be seen on one of the two examples of Anglo-Saxon anvils so far found in Britain, in the smith’s grave at Tattershall Thorpe, Lincolnshire (Hinton 2000, fig. 15, 4). Twenty nails have their shanks off-centre; these appear to be a small proportion where the hammering of the head has been slightly miss-aimed, though they still are functional enough to be used. It may be the case that some off-set heads were occasionally deliberate, for example those at Wharram Percy, where they are relatively common (Watt 2000, 141).

There appears to be no direct correlation between the size of the head and the length of nails up to 100mm in length. Some have been utilised as studs, with heads playing a large and possibly decorative role. Once the length of the nail is increased to 100mm and above, however, both the shank and head increase in dimension. The longest two nails of head form A (RFs 1269 and 5503) bear the largest heads and thickest shanks: these represent a group of heavy-duty nails, possibly with a specific function. The heads of these two types may not have originally been as flat, as they may have been distorted by the force of hammer blows required to drive in such large nails.

Type E bears a similar head form to Roman upholstery studs (cf. Manning 1985 fig. 32, 8). It appears possible that the six examples of this type may also have been used as such. The domed head would be more effective than a flat head at gripping the fabric or leather, and holding it in place, thus preventing wear around the nail shank. In addition, the domed head would have given a decorative appearance. These types of nails may also have been used during the manufacture of leather harness. This form of nail is still in use today as an upholstery nail, albeit of copper alloy. The earliest nail of this type was recovered from a Phase 2 floor (3336), within building 20.

Type G, of which a single example was found (RF 3499), was also possibly used for upholstery (ibid., 135).

Types B, C and D were probably used for carpentry, when the use of a nail with a protruding head would have been unsuitable or unsightly, such as in wooden floor surfaces and on fine carpentry. Their slender heads, or lack of a head, would have enabled them to be hammered completely into the wood. It seems likely that some of the headless nails at Coppergate, in York were deliberately fashioned so (Ottaway 1992, 611), though there is a possibility that the three from Flixborough may represent nails which are either unfinished, or which have subsequently lost their heads.

Nails, rivets, studs and tacks

by Patrick Ottaway

Included amongst the above examples are at least 46 items which merit specific description and catalogue entry.

Plated nails

There are 15 nails, or tacks, which are plated with non-ferrous metal. This served both to prevent corrosion and to act as decoration. Where analysed, the plating is tin-lead alloy. No. 1052 (RF 9858; Phase 6ii–7) stands out from the other nails in having a solid and pronounced dome-shaped head.

None of these plated nails needs be earlier than Phase 5a and most, if stratified, are from Phase 6. However the tin-plating of nails (and other iron objects) appears to have begun in the early 8th century, and as time went on the practice became more widespread. Forty-four plated nails were found in Anglo-Scandinavian contexts at 16–22 Copper-gate, York (Ottaway 1992, 611–13). In addition, tinned dome-headed nails have been found used for decoration in a number of surviving wooden objects in Scandinavia, including a sledge and chest from the Viking Age ship burial at Oseberg (Grieg 1928, figs 17, 34 and 134).

Split rivet

No. 1054 (RF 12566; unstratified) is a small split rivet, used for repairing a vessel. RF 8045 (Phase 6ii–iii) is a split rivet holding two fragments of plate together.

Studs

There is a very distinctive group of objects from Flixborough which may be described as studs, of which there are 29 examples (nine unstratified). They usually exist as a round or roughly rounded head which is slightly domed, and a short shank no more than 20mm long, often set slightly off the centre of the head. There are also, however, two objects classified under this heading (nos 1055 and 1066; RFs 352 and 8133 – respectively from topsoil and Phase 6ii–iii) which have sub-rectangular heads and lengths of 53mm and 50mm.

The stratified studs come largely from Phase 6 contexts. There are no obvious parallels for them from other Anglo-Saxon contexts and their function is uncertain, although they may have been used to attach coverings of leather or other materials to doors or items of furniture. They may also have been considered decorative.

Mount or stud

No. 1084 (RF 8962) is an unstratified tin-plated mount or small stud with a domed head in the form of a cross.

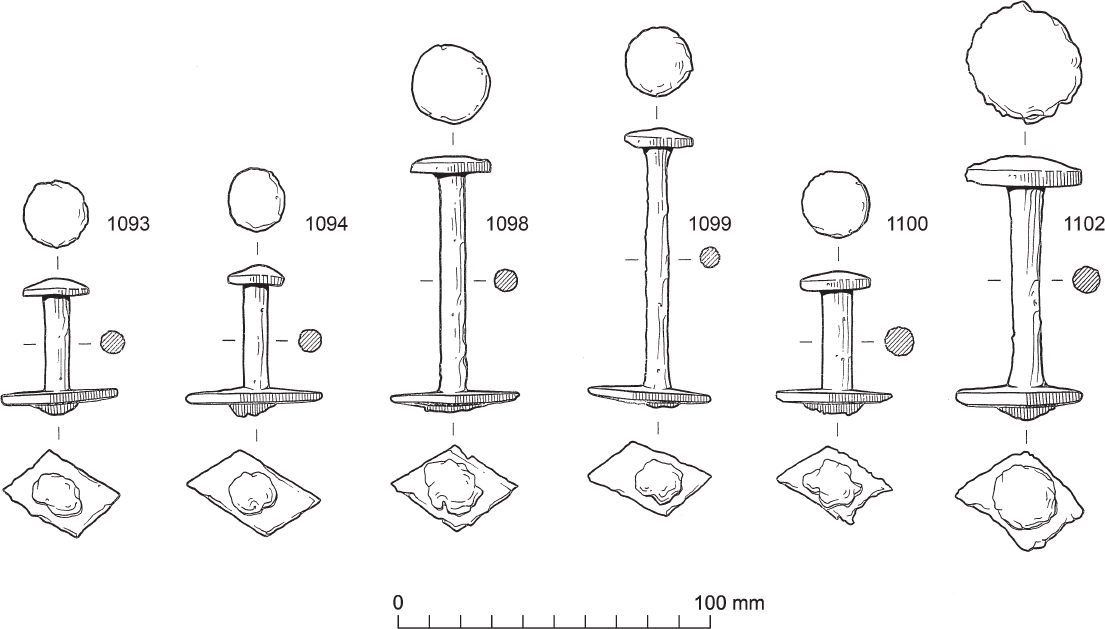

Clench bolts and roves (FIG. 4.2)

There are 27 clench bolts, or ‘clench nails’ (five unstratified), and 23 additional roves. A clench bolt was used for joining overlapping timbers, and consisted of a nail-like component which, once it had passed through the timbers to be joined, had a small pierced plate – the rove – set over its tip. The tip was then burred, or more usually hammered over (i.e. clenched) to hold the bolt in place. [For a description of the use of clench bolts, see Christensen 1982, 331.]

All the examples from Flixborough have shanks of rounded cross-section, and 22 of the bolts have diamond-shaped roves, while 20 of the additional roves are also diamond-shaped; the remaining roves, where the shape is determinable, are rectangular. The Flixborough bolts are for the most part substantial. Although no. 1106 (RF 12914; unstratified) is only 25mm long, the others are 42–87mm long, and seven are over 70mm. The shanks are up to 10mm thick.

It is hard to estimate the thickness of wood these bolts would have joined, because they could either have passed through the thickness of two pieces of wood, or, of only one, if the timbers were scarf-jointed. Nonetheless, the size of the Flixborough clench bolts suggests their use in either large timber objects, or clinker-built ships in which they would have joined the strakes and secured other elements. For comparative purposes, it may be noted that the clench bolts from the strakes of the Sutton Hoo ship measured c.54, 70 and 92mm (Evans and Bruce-Mitford 1975, 355–65, figs 277 and 279).

FIG. 4.2. Iron clench bolts. Scale 1:2.

While the most common context for the discovery of clench bolts in the Anglo-Saxon period is ships, they do occur on occupation sites, and another large group was found in Anglo-Scandinavian contexts at 16–22 Coppergate, York. It may be noted, however, that the pattern of dimensions was quite different from that at Flixborough. In the Coppergate group only three out of 55 examples were over 60mm in length, the majority measuring 27–45mm. Although these smaller bolts could have come from ships, they may have been more suited to service in doors, wagon bodies or even coffins – all uses which are attested in the 8th–10th centuries (Ottaway 1992, 617–18). Another difference between the clench bolts from York and those from Flixborough is that the York examples, like nails of the Anglo-Saxon period, usually had shanks of rectangular cross-section, while those from Flixborough all, as noted, have shanks of rounded cross-section. While the York clench bolts could have been hammered into wood, the Flixborough bolts being thicker and of rounded section were probably set in pre-drilled holes; the hole is likely to have had a either a slightly smaller or identical diameter as the bolt, as in the way that wooden pegs/dowels are used.

The only multiple instances of clench bolts within the same context are as follows:

Contexts 2488 (3 examples), 2562 (2) and 3107 (2). The low numbers of such incidences suggest that few overlapping sections of articulated timber, joined in this way, were discarded on the site.

Staples

Both clench bolts and staples are ubiquitous forms of fastening which can be found from the Romano-British period onwards, with no very obvious changes in form: on their own, they are undiagnostic, and this clearly causes a problem on a site like this which has not only a small but marked presence of Romano-British material surviving in what are clearly Anglo-Saxon contexts, but also a continuum into the post-Conquest medieval period.

There are c.225 staples which may be divided into four groups: rectangular, U-shaped, looped, and a fourth group the members of which are usually U-shaped, but are made from flat strips of iron which are relatively thin compared to the strips of rectangular cross-section used for the other groups.

There are c.75 rectangular staples, many of which are now incomplete. The arms taper to wedge-shaped tips, and in many cases they are bent outwards or inwards. Width varies from 19–56mm, and the length of the arms varies from 11–45mm.

There are 102 U-shaped staples. The arm tips are usually pointed, and in a few cases the wider faces of the arms are in the same plane as the staple itself, rather than at 90° to it as is normal. In some cases, the arm tips are bent outwards, and in rather fewer cases bent inwards. Width varies from 12–45mm, and length from 15–68mm, except for one staple (no. 1265; RF 9181, Phase 4ii) which is 106mm long. An unstratified staple (no. 1296; RF 13090) is plated. This is very unusual, and it presumably came from a chest or casket with other plated fittings.

There are 18 looped staples. These are staples with a loop at the head, and arms which then lie close together below it; in some cases the tips are turned outwards. Length varies from 33–66mm, and width 10–23mm.

The fourth group of staples, of which there are c.30, are those made from thin flat strips. In form they are typically U–shaped, with arms which are bent outwards at c.90°, and often looped over in an extravagant manner. The U-shaped part of the staple is usually small; maximum length is 50mm, but most measure c.15–30mm. Overall width is rarely more than c.40mm. Whereas staples in the previous groups would usually have been hammered into place, those in this group are insufficiently robust. They were presumably passed in a part-formed state through pre-drilled holes, before being given their final form.

The function of staples was varied, but principally it was to join pieces of wood together, or to hold fittings such as chains, hasps and handles in place. In view of the small size of most of the Flixborough staples, and the lack of large specimens comparable to those found in Roman and later Anglo-Saxon contexts, the second function is likely to have predominated at this site. This is to some extent confirmed by the survival of staples attached to other fittings, such as hasps nos 1718–20 (RFs 586, 733 and 1799), and stapled hasp no. 11 (FX 88, R16) from the burial chest (see Ottaway in Volume 1, Ch. 8.3, catalogue no. 11). While on the subject of staple function, it should finally be noted that two objects, closely resembling rectangular staples with inturned arms, and measuring 48 × 20mm, were found serving as belt clasps in an Anglo-Saxon burial at Yeavering, Northumberland (Hope-Taylor 1977, fig. 87.2).

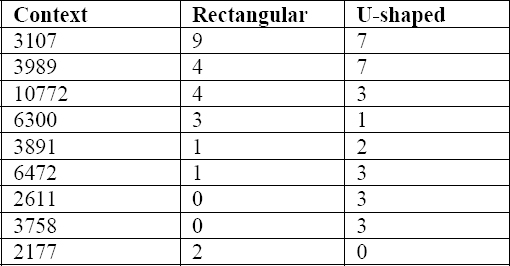

All the forms of staple described here are well-known in Anglo-Saxon contexts elsewhere, although the fourth is rare in those of the late Anglo-Saxon period. It may also be noted that when the staples from Flixborough are compared with those in the large assemblage from 16–22 Coppergate, York (Ottaway 1992, 619–23), there is a striking difference in the relative numbers of the rectangular and U-shaped forms, as can be seen in FIG. 4.3.

In addition, when rectangular and U-shaped staples are considered in terms of their size, it appears that while there is considerable variation in both groups, there are no examples at Flixborough of the large and robust rectangular staples found at York which have lengths of up to c.80mm.

FIG. 4.4. Incidence of multiple finds of staples in the same context.

There are some notable concentrations of staples recovered from the same contexts: as many of these are dump layers, or deposits in the ditch, these suggest that large pieces of structural woodwork (presumably from redundant or derelict buildings) were being discarded in these layers.

Collars

There are 10 small collars, objects which are similar to staples, but have overlapping arms; in two cases (nos 1361–2; RFs 5454 and 6607) – respectively from Phases 4ii and 6ii–iii – the arms ends are twisted around each other. No. 1364 (RF 6812) is pierced for attachment with a rivet. Collars were used in a similar way to small staples for holding fittings in place, although no. 1364 (RF 6812) may have served to grip the end of a wooden handle, such as might be found on an awl.

Hinges, hinge pivots etc.

This broad heading includes 58 examples of hinge straps, hinge pivots, U-eyed hinges and fittings; as many of these could also relate to domestic fittings, this whole category is discussed in Ch. 5, below.

Catalogue

Nails, studs and rivets

PLATED NAILS

Plating metal given if analysed.

1037 |

Plating is tin |

1038 |

Plating is tin-lead |

1039 |

Lead detected at top of shank |

1040 |

Head only. D.15mm Plating is tin-lead |

1041 |

Domed head. L.12mm |

1042 |

Domed head. Plating is tin. L.17mm |

1043 |

Shank largely missing. Head: D.16mm |

1044 |

Plating is tin-lead. |

1045 |

Head only. Plating is tin. D.33mm |

1046 |

Shank bent at 90° in centre. Plating is tin-lead. L.22mm |

1047 |

Plating is tin. |

1048 |

Plating is tin-lead. |

1049 |

Plating is tin-lead. |

1050 |

Plating is tin-lead. |

1051 |

Plating is tin-lead. |

1052 |

Domed head. Plating is tin. L.39mm |

1053 |

Plating is tin. |

SPLIT RIVET |

|

1054 |

Arms splayed in opposite directions. Head: D.16mm |

STUDS

Unless stated all these objects consist of a round or roughly round head which is slightly domed. A short shank projects or projected from the concave face.

1055 |

Sub-rectangular head. L.50, W.41mm |

1056 |

Head only. D.38mm |

1057 |

Head only. D.48mm |

1058 |

Shank off-centre. D.56mm |

1059 |

Oval head only. D.56mm |

1060 |

D.56, L.18mm |

1061 |

D. 44, L.12mm |

1062 |

Shank missing. D.43mm |

1063 |

|

1064 |

Head incomplete. D.51, L.10mm |

1065 |

Shank missing. D.42mm |

1066 |

Sub-rectangular head. L.53, W.50mm |

1067 |

D.40, L.11mm |

1068 |

D.43, L.12mm |

1069 |

D. 41, L.10mm |

1070 |

Head only. D.64mm |

1071 |

D.70, L.8mm |

1072 |

Shank off-centre. D.45, L.10mm |

1073 |

Flat oval head only. D.50mm |

1074 |

Head only. D.42mm |

1075 |

Incomplete. D.53mm |

1076 |

Head only. D.48mm |

1077 |

Damaged. Shank off-centre. D.37mm |

1078 |

Incomplete flat head, stub of shank. D.33mm |

1079 |

Shank off-centre. D.50, L.12mm |

1080 |

Damaged head only. D.48mm |

1081 |

Head only. D.32mm |

1082 |

Shank off-centre. D.40, L.12mm |

1083 |

Shank off-centre. D.44, L.12mm |

MOUNT OR STUD |

|

1084 |

Mount or small stud with domed head in form of a cross, shank largely missing. Plated (tin-lead). L.15, W.26m |

Clench bolts (FIG. 4.2)

All have rounded heads and shanks of rounded cross-section.

DIAMOND-SHAPED ROVES

1085 |

L.43mm |

1086 |

Rove incomplete. L.39mm |

1087 |

L.77mm |

1088 |

L.48mm |

1089. |

L.51mm |

1090 |

L.47mm |

1091 |

L.51mm |

1092 |

L.47mm |

1093 |

L.42mm (FIG. 4.2) |

1094 |

L.44mm (FIG. 4.2) |

1095 |

L.70mm |

1096 |

Incomplete rove and stub of shank. L.33mm |

1097 |

Rove has one rounded end. L.76mm |

1098 |

L.81mm (FIG. 4.2) |

1099 |

L.87mm (FIG. 4.2) |

1100 |

L.44mm (FIG. 4.2) |

1101 |

Rove and stub of shank only. L.37mm |

1102 |

L.81mm (FIG. 4.2) |

1103 |

Rove fragmentary, shank bent. L.42mm |

1104 |

Head missing, shank incomplete. L.53mm |

1105 |

Head missing, shank incomplete. L.62mm |

1106 |

L.25mm |

OTHER ROVE SHAPES |

|

1107 |

Roughly rectangular rove. L.73mm |

1108 |

Rounded rove. L.53mm |

1109 |

Square rove. Shank bent into C-shape. L.c.40mm |

FRAGMENTARY ROVE |

|

1110 |

L.29mm |

SHANK ONLY |

|

1111 |

L.50mm |

ROVES ONLY: DIAMOND-SHAPED |

|

1112 |

L.36mm |

1113 |

L.44mm |

Incomplete. L.28mm |

|

1115 |

L.35mm |

1116 |

Incomplete. L.32mm |

1117 |

L.55mm |

1118 |

Incomplete. L.40mm |

1119 |

L.32mm |

1120 |

Fragment |

1121 |

L.25mm |

1122 |

L.36mm |

1123 |

Fragment. |

1124 |

Fragment |

1125 |

Incomplete. L.35mm |

1126 |

Curved in cross-section. L.38mm |

1127 |

Incomplete. L.17mm |

1128 |

L.33mm |

1129 |

L.26mm |

1130 |

Incomplete. L.33mm |

1131 |

L.26mm |

ROVES ONLY: RECTANGULAR |

|

1132 |

L.25mm |

1133 |

L.16mm |

1134 |

L.25mm |

Staples |

|

L. = length of arms |

|

RECTANGULAR |

|

1135 |

Arms incomplete. L.10, W.39mm |

1136 |

One arm largely missing. L.20, W.27mm |

1137 |

One arm missing, surviving arm tip in-turned. L.19, W.36mm |

1138 |

L.22, W.43mm |

1139 |

Arm tips clenched. L.29, W.53mm |

1140 |

L.28, W.38mm. Wood traces on one arm, grain going across. Seems to be a ring-porous wood, but not enough to identify. |

1141 |

One arm missing, surviving arm tip in-turned. L.30, W.50mm |

1142 |

Surviving arm bent into U-shape. Probably random plant stems. L.18, W.40mm |

1143 |

Twisted, one arm missing. L.30, W.51mm |

1144 |

Fragment. |

1145 |

One arm tip out-turned. L.17, W.26mm |

1146 |

Bent out of shape. W.39mm |

1147 |

L.28, W.47mm |

1148 |

L.37, W.20mm |

1149 |

Incomplete. L.18, W.15mm |

1150 |

Arm tips clenched. L.28, W.49mm |

1151 |

Surviving arm tip in-turned. L.21, W.50mm |

1152 |

One arm missing. L.13, W.40mm |

1153 |

Arms tips in-turned. L.17, W.22mm |

1154 |

One arm missing. L.24, W.63mm |

1155 |

One arm missing, surviving arm tip in-turned. |

1156 |

One arm missing. L.45, W.26mm |

1157 |

Both arms incomplete. L.20, W.21mm |

1158 |

Arm tips in-turned. L.21, W.56mm |

1159 |

One arm missing, surviving arm tip in-turned. Slight trace of random organic material. L.27, W.32mm |

1160 |

One arm missing, other incomplete. Trace of wood on side but probably random as the grain orientation is unusual for this position on a staple. L.24, W.59mm |

1161 |

One arm missing, surviving arm tip in-turned. L.17, W.40mm |

1162 |

Both arms largely missing. Trace of organic? inside, but no identifiable features. L.10, W.35mm |

One arm bent inwards and incomplete. L.28, W.41mm |

|

1164 |

Incomplete. L.35, W.21mm |

1165 |

Incomplete. L.20, W.21mm |

1166 |

Incomplete. L.24, W.14mm |

1167 |

Bent out of shape, one arm missing. L.23, W.31mm |

1168 |

One arm missing. L.35, W.25mm |

1169 |

Both arms incomplete. L.14, W.37mm |

1170 |

One arm largely missing. L.27, W.22mm |

1171 |

One arm missing. L.20, W.41mm |

1172 |

One arm missing. L.17, W.22mm |

1173 |

Both arms incomplete. L.10, W.48mm |

1174 |

One arm incomplete. L.22, W.61mm |

1175 |

Incomplete. L.18, W.13mm |

1176 |

One arm missing, surviving arm tip in-turned. Possible organic material at one end, but no structure. L.23, W.26mm |

1177 |

One arm incomplete. L.19, W.31mm |

1178 |

Arms largely missing. W.36mm |

1179 |

One arm incomplete. L.16, W.34mm |

1180 |

Incomplete. Surviving arm tip in-turned. Possible wood traces, nothing visible now. L.27, W.26mm |

1181 |

Arm tips in-turned and clenched. Possible organic traces, probably random. L.19, W.27mm |

1182 |

One arm missing. L.20, W.26mm |

1183 |

Incomplete. L.19m |

1184 |

Incomplete. L.16mm |

1185 |

Arm tips in-turned. L.26, W.45mm |

1186 |

One arm incomplete, other in-turned. L.27, W.45mm |

1187 |

One arm incomplete, surviving arm tip out-turned. L.16, W.23mm |

1188 |

Arm tips in-turned. L.28, W.38mm |

1189 |

Arms incomplete. L.16, W.49mm |

1190 |

Incomplete. Surviving arm tip in-turned. L.18, W.24mm |

1191 |

Arms largely missing. L.14, W.26mm |

1192 |

L.13, W.46mm |

1193 |

One arm only. L.34mm |

1194 |

Arms largely missing. L.14, W.37mm |

1195 |

Arms missing. W.34mm |

1196 |

L.26, W.38mm |

1197 |

One arm missing. L.20, W.49mm |

1198 |

One arm largely missing. L.27, W.19mm |

1199 |

Arms incomplete. L.8, W.26mm |

1200 |

Arms bent. Charcoal. L.11, W.35mm |

1201 |

One arm missing. L.22, W.37mm |

1202 |

Both arm tips missing. Charcoal. L.28, W.30mm |

1203 |

One arm missing. L.33, W.15mm |

1204 |

One arm missing, surviving arm tip out-turned. L.14, W.30mm |

1205 |

One arm missing. Slight possible wood traces. L.35, W.19mm |

1206 |

L.9, W.32mm |

1207 |

One arm tip out-turned, other in-turned. L.28, W.28mm |

1208 |

Arm tips in-turned. L.27, W.50mm |

1209 |

One arm incomplete, other has tip missing. L.29, W.28mm |

U-shaped |

|

1210 |

Wood remains survive. Small trace of wood, but nothing definite. L.41, W.19mm |

1211 |

L.62, W.26mm |

1212 |

Both arms incomplete. L.25, W.18mm |

One arm tip in-turned, other missing. L.30, W.32mm |

|

1214 |

One arm tip in-turned, other out-turned. Possible organic material but no clear structure. L.25, W.20mm |

1215 |

One arm incomplete. L.40, W.29mm |

1216 |

One arm tip out-turned. L.35, W.24mm |

1217 |

Both arms incomplete. L.18, W.19mm |

1218 |

Both arms incomplete. L.26, W.18mm |

1219 |

One arm incomplete. L.33mm |

1220 |

One arm largely missing. L.43, W.21mm |

1221 |

Arm tips bent forwards. L.68, W.20mm |

1222 |

One arm missing. L.33mm |

1223 |

One arm incomplete. L.45, W.19mm |

1224 |

One arm out-turned and clenched. L.37, W.23mm |

1225 |

One arm missing. L.36, W.15mm |

1226 |

Fragment. |

1227 |

Arm tips bent forwards. L.40, W.18mm |

1228 |

Fragment. |

1229 |

One arm longer than other. L.39, W.24mm |

1230 |

One arm incomplete. Trace of wood with grain going across one arm, random. L.45, W.17mm |

1231 |

One arm tip out-turned. L.47, W.45mm |

1232 |

L.31, W.23mm |

1233 |

One arm incomplete. L.52, W.21mm |

1234 |

L.30, W.20mm |

1235 |

L.31, W.16mm |

1236 |

L.34, W.17mm |

1237 |

Arms do not taper, tips out-turned. L.33, W.20mm |

1238 |

One arm missing, surviving arm tip out-turned. Charcoal. L.35mm |

1239 |

Charcoal and random organic material. L.33, W.13mm |

1240 |

Arm tips out-turned. L.20, W.12mm |

1241 |

One arm missing. Charcoal. L.62mm |

1242 |

One arm largely missing. L.41, W.25mm |

1243 |

L.39, W.19mm |

1244 |

One arm missing. Trace of wood, but probably random. L.36, W.31mm |

1245 |

One arm missing, surviving arm out-turned and clenched. L.31mm |

1246 |

One arm missing. Organic traces, probably random. L.46, W.24mm |

1247 |

Arms do not taper, tips out-turned. Charcoal. L.37, W.21mm |

1248 |

One arm incomplete. L.49, W.18mm |

1249 |

One arm tip out-turned. L.24, W.21mm |

1250 |

L.30, W.25mm |

1251 |

One arm incomplete. L.26, W.18mm |

1252 |

Arms do not taper. L.45, W.21mm |

1253 |

One arm. L.24mm |

1254 |

One arm incomplete. L.15, W.12mm |

1255 |

L.18, W.14mm |

1256. |

One arm incomplete, other bent. Wood remains survive. Wood on both sides, grain across short width. Layer of wood on inside of the loop, but not enough to identify. L.36, W.22mm |

1257 |

Arm tips out-turned. L.20, W.21mm |

1258 |

L.32, W.14mm |

1259 |

Arms twisted. L.c.50, W.39mm |

1260 |

Arm tips in-turned. L.38, W.28mm |

1261 |

L.36, W.21mm |

1262 |

L.27, W.12mm |

One arm incomplete. L.22, W.15mm |

|

1264 |

One arm missing. L.54mm |

1265 |

One arm, tip out-turned. L.106, W.17mm |

1266 |

The arms’ wider faces are in the same plane as staple. L.27, W.22mm |

1267 |

Arms incomplete. L.31, W.30mm |

1268 |

Arms incomplete. L.22, W.22mm |

1269 |

L.22, W.14mm |

1270 |

One arm incomplete. L.55, W.40mm |

1271 |

Arm tips bent forwards. L.25, W.21mm |

1272 |

Arms incomplete. L.18, W.25mm |

1273 |

Possible wood traces, nothing visible now. L.45, W.20mm |

1274 |

L.27, W.22mm |

1275 |

One arm incomplete. Flecks of non-ferrous metal adhere. |

1276 |

One arm. L.37mm |

1277 |

Arms do not taper. L.30, W.22mm |

1278 |

Fragment. |

1279 |

One arm largely missing. Patch of lead adheres. L.35, W.18mm |

1280 |

One arm missing; surviving arm tip out-turned. L.50, W.20mm |

1281 |

One arm only, triangular cross-section at head. L.56mm |

1282 |

Arm tips bent forwards. L.23, W.17mm |

1283 |

Fragment. |

1284 |

L.65, W.23mm |

1285 |

Arms of unequal length. Random organic material and bone. L.67, W.25mm |

1286 |

One arm incomplete. L.46, W.18mm |

1287 |

One arm missing, surviving arm tip out-turned. L.16, W.15mm |

1288 |

One arm missing, surviving arm tip out-turned. Possible organic material on one end, but no clear structure. L.25, W.12mm |

1289 |

L.27, W.14mm |

1290 |

One arm incomplete. Possible organic traces, but no clear structure. L.34, W.22mm |

1291 |

L.26, W.15mm |

1292 |

One arm missing. L.39mm |

1293 |

Arms pinched together. L.36, W.15mm |

1294 |

One arm incomplete. L.18, W.13mm |

1295 |

One arm incomplete. L.26, W.15mm |

1296 |

Arm tips out-turned. Plated. L.35, W.15mm |

1297 |

The arms’ wider faces are in the same plane as the staple. L.49, W.25mm |

1298 |

Arm tips missing. L.61, W.35mm |

1299 |

Fragment. |

1300 |

One arm missing. L.32mm |

1301 |

L.40, W.19mm |

1302 |

Fragment. Wood survives, but not enough to comment on. |

1303 |

One arm incomplete. L.40, W.29mm |

1304 |

L.19, W.14mm |

1305 |

Arms incomplete; their wider faces are in the same plane as the staple. L.22, W.20mm |

1306 |

Slight wood traces, nothing visible now. L.27, W.16mm |

1307 |

Smooth area resembling leather. L.25, W.14mm |

1308 |

One arm. L.52mm |

1309 |

L.40, W.18mm |

1310 |

One arm missing. L.23mm |

1311 |

L.48, W.39mm |

1312 |

Random organic material. L.52, W.21mm |

1313 |

Possible wood traces, but no longer there. L.44, W.19mm |

1314 |

L.42, W.17mm |

1315 |

Slight organic traces, probably random. L.51, W.14mm |

1316 |

L.41, W.15mm |

1317 |

Arms largely missing. L.28, W.20mm |

1318 |

Arms largely missing. L.18, W.18mm |

1319 |

Arms largely missing. L.20, W.11mm |

1320 |

One arm missing. L.33, W.10mm |

1321 |

Arm tips out-turned. Charcoal and random fibrous organic material. L.36, W.14mm |

1322 |

Heavily encrusted, some random organic material. L.66, W.20mm |

1323 |

L.45, W.12mm |

1324 |

Trace of random organic material. L.44, W.19mm |

1325 |

L.44, W.21mm |

1326 |

L.53, W.23mm |

1327 |

One arm incomplete. Charcoal and bone. L.45, W.22mm |

1328 |

Arm ends missing. L.37, W.21mm |

1329 |

Arm tips out-turned. L.45, W.18mm |

U-shaped staples made from thin flat strips

Arm ends out-turned unless stated

1330 |

One arm incomplete, other has U-shaped end. L.23mm |

1331 |

Bent out of shape. L.44mm |

1332 |

One arm end looped, other U-shaped. L.20, W.34mm |

1333 |

Arms twisted. L.37, W.20mm |

1334 |

One arm missing, other has U-shaped end. L.20, W.15mm |

1335 |

One arm missing. L.25, W.20mm |

1336 |

Arms U-shaped. L.20, W.32mm |

1337 |

One arm incomplete, surviving arm has U-shape. Charcoal. L.24, W.31mm |

1338 |

Random organic material including a possible seed? L.19, W.12mm |

1339 |

One arm missing. L.27, W.19mm |

1340 |

Arms twisted. L.50, W.39mm |

1341 |

One arm incomplete. Light traces of fibrous organic material, random. |

1342 |

Arm ends U-shaped. Random fragments including plant stems. L.22, W.44mm |

1343 |

One arm ends in a loop. L.28, W.45mm |

1344 |

Charcoal. L.26, W.37mm |

1345 |

One arm missing. Wood traces, may be random, nothing visible now. L.18, W.18mm |

1346 |

One arm incomplete. Charcoal. L.19, W.12mm |

1347 |

L.23, W.14mm |

1348 |

One arm incomplete, other has U-shaped end. W.21mm |

1349 |

One arm has looped end. Random organic material. L.17, W.35mm |

1350 |

Arm tips bent up. L.25mm |

1351 |

One arm has U-shaped end. L.22, W.31mm |

1352 |

One arm bent into rough loop. Wood, but probably random. L.21, W.48mm |

1353 |

One arm missing. L.22, W.17mm |

1354 |

One arm missing. L.14mm |

1355 |

Arms have looped ends. Charcoal and random organic material. L.14, W.22mm |

1356 |

One arm is incomplete. Random organic material. L.32, W.32mm |

1357 |

One arm incomplete. Charcoal. L.18, W.15mm |

1358 |

One arm missing. Fragment of random organic material on outside of loop. L.32, W.19mm |

Arms have looped ends. L.16, W.28mm |

Collars

Collars resemble staples, but the arms overlap each other.

1360 |

Sub-rectangular. L.22, W.16mm |

1361 |

Sub-rectangular. Where ends meet, one twisted around the other. Piece of iron strip threaded through a single piece of wood from the tangential surface; the fitting does not appear to serve as a means of joining two pieces of wood together. Probably Pomoideae, a fruit-wood such as Malus sp. (apple), Pyrus sp. (pear), Crataegus sp. (hawthorn) – [SEM B797]. L.42, W.19mm |

1362 |

Sub-rectangular. Where ends meet, one twisted around the other. L.21, W.19mm |

1363 |

Oval. L.24, W.10mm |

1364 |

Crushed oval, pierced for attachment with nail in situ. L.41, W.21mm |

1365 |

Incomplete, circular. D.33, W.12mm |

1366 |

Incomplete, circular. D.49, W.23mm |

1367 |

Circular. L.19, W.16mm |

1368 |

Exists as a loop with overlapping ends, L.25, W.11mm |

1369 |

Incomplete, was oval. L.53mm |

1370 |

Incomplete circular. D.26, W.9mm |

4.2 Structural fired clay or daub

by Lisa M. Wastling

Introduction

The term daub is applied to clay with the addition of temper, smeared or daubed onto a rigid wooden framework to form structures such as walls, ovens and hearths. The framework usually consists of woven roundwood, termed wattles, with the horizontals referred to as rods, and the verticals, sails. During construction the rods are woven in between the sails. Daub is not normally preserved in the British climate, though when burning occurs, it can become fired to a high enough degree to ensure its survival. Burning may be the result of use (as in the case of ovens), part of the demolition process, or of accidental burning of structures. This form of preservation precludes the survival of the wood, except in rare cases when charcoal survives; however, the impressions of the wooden framework are often preserved well enough to be quantified.

Daub weighing 56kg was recovered from 379 contexts at Flixborough, with sample weights ranging from as small as 1 to 8626g.

In addition to the structural daub and hearth bases, some of the fired clay fragments have been identified as small pieces of unprepared or accidentally fired clay, and small fragments of fired clay objects, in the same fabric as the loom-weights (see Ch. 9).

As structural fired clay has commanded little attention in many site reports, and extant wattle panels have also rarely been recorded in detail, much of the comparanda in this report are of differing dates from the material at Flixborough. This is unfortunately a situation that can only be rectified with time, as little appears to have changed since Morgan’s paper of 1988 (op. cit.).

Fabrics

Eleven different fabric types were identified by eye and by the use of binocular microscope at ×20 magnification. The method used was based on that recommended for pottery fabric recording, outlined in Orton et al. (1993, 231–42).

The majority of fragments were assigned to fabrics A to I, fragments of clay objects were given the fabric code O, and small unidentifiable fragments the code U. Variations in hardness, texture and colour within a fabric can occur, and are due to the heat variations and the differing amounts of oxygen reaching different parts of the structures during the burning process, causing some pieces to be oxidised and others reduced. More detailed petrological examination of the fabric types may reveal that some of the lesser fabrics may be variants of the main types.

Fabric A |

|

Colour: |

2.5YR 6/8 to 7.5YR 7/4 |

Hardness: |

soft |

Feel: |

powdery |

Texture: |

fine |

Inclusions: |

abundant fine quartz sand, moderate fine mica, moderate fine sand, sparse organic grass/chaff, sparse ferrous inclusions 1mm in size. |

Usage: |

hearth daub |

Fabric B |

|

Colour: |

ranges from reddish-yellow, 5YR 7/6 through to yellowish-red, 5YR 6/6, 5YR 5/6 with occasional patches of red-brown 7.5 YR 6/2 and 7.5YR 5/2. This depends on the heat intensity and amount of oxygen reaching the fragments during burning. |

Hardness: |

hard |

Feel: |

slightly rough |

Texture: |

irregular fracture |

sparse to moderate stone inclusions 2-10mm in size (sandstone fragments and glacial erratic fragments), moderate voids, some due to organic material in the clay, others possibly due to the material being not so well worked, or not worked at all prior to use. |

|

Usage: |

hearth repair and accidentally fired unprepared clay |

Fabric C |

|

Colour: |

reddish-yellow 5YR 6/6 to brown 7.5YR 5/2. Occasionally has a reduced core or patches of mid to dark grey. |

Hardness: |

soft to hard |

Feel: |

rough to harsh |

Texture: |

irregular fracture |

Inclusions: |

abundant organic temper, with grass/chaff impressions and voids, moderate very fine sand, sparse mica. On inspection through the binocular microscope at ×20 magnification, the surfaces have a mottled appearance with small dark brown to black patches, possibly due to the addition of other organic material such as animal dung. Light in weight in relation to its mass. |

Usage: |

wall daub, oven structures. |

Fabric D |

|

Colour: |

pink 7.5YR 7/4 to very pale brown 10YR 7/3 to 10YR 8/2, occasionally reduced to grey 10YR 5/1. |

Hardness: |

soft |

Feel: |

smooth, powdery |

Texture: |

fine |

Inclusions: |

abundant fine sand, moderate voids due to organic grass/chaff temper, moderate mica, sparse stone inclusions e.g. Magnesian Limestone and occasional glacial erratic fragments 5–8mm in size. |

Usage: |

possibly used for walls and oven structures. |

Fabric E |

|

Colour: |

2.5YR 6/8 to 7.5YR 7/4 |

Hardness: |

hard |

Feel: |

slightly rough |

Inclusions: |

abundant fine quartz sand, abundant fine shell fragments or plate-like voids where leached out, moderate fine sand, sparse grass/chaff voids, sparse ferrous inclusions, 1mm in size. |

Usage: |

unknown |

Fabric F |

|

Colour: |

light yellowish-brown 10YR 6/4 to pale brown 10YR 63, with occasional patches reduced to light grey, |

Hardness: |

soft to hard |

Feel: |

smooth |

Texture: |

fine |

Inclusions: |

very abundant grass/chaff with well-preserved impressions, sparse small calcareous inclusions, slightly rounded, possibly chalk <0.5 to 2mm in size. |

Usage: |

possibly oven structures, macroscopically similar to kiln fabric. |

Fabric G |

|

Colour: |

red 2.5YR 5/6 to strong brown 7.5YR 5/8 (this is very ochre-like in colour) |

Hardness: |

hard |

Feel: |

powdery to smooth |

Texture: |

fine |

Inclusions: |

moderate very fine sand, sparse voids. As fabric A, the clay is well worked to remove inclusions. |

Usage: |

hearth daub |

Fabric H |

|

Colour: |

reddish-yellow 7.5YR 7/6 to light red 2.5YR 6/8 |

Hardness: |

soft to hard |

Feel: |

slightly rough |

Texture: |

irregular |

Inclusions: |

abundant fine voids and fine calcareous inclusions (chalk or fine limestone and occasional fossil shell 1–5mm), moderate grass/chaff voids, occasional fossil shell 1–5mm. |

Usage: |

curved surfaces, possibly oven daub. |

Fabric I |

|

Colour: |

brown 10YR 5/3 to 7.5YR 5/2 |

Hardness: |

very hard |

Feel: |

rough |

Texture: |

irregular |

Inclusions: |

abundant medium sand, moderate grass/chaff voids This fabric is dense in mass. |

Usage: |

structural – walls |

Fabric O

Virtually inclusion free, hard, very well-worked clay of the type used for objects such as loom-weights. See reports by Walton Rogers and Vince (Ch. 9, below).

Fabric U

Consists of tiny scrap fragments – too small to be classified.

The quantities of each fabric can be seen in FIG. 4.5, and percentages in FIG. 4.6. Just 10 contexts produced 57% of the total amount of structural fired clay. The majority of these were dumps (FIG. 4.7). The clay from one hearth in situ, (466) was collected in its entirety, producing the largest single sample by weight at 8626g. The lack of other hearth material is due largely to the excavation method, whereby hearth material was not collected from other in situ hearths, except occasionally in small amounts.

The wall daub

Fabrics C, D and H may have been used to construct both walls and oven superstructures, with some fragments bearing curved surfaces. Unfortunately, no upper oven structures were found in situ or collapsed over hearth or oven bases, with the exception of the medieval oven 1342, in Phase 7. Buildings may also have had rounded corners. The fragmentation of the material and its re-deposition in dumping phases makes more conclusive interpretation difficult. It must also be remembered that the surviving material must be a biased sample, simply due to the method of its preservation. The characteristics of this preserved building material should not be presumed to be representative of all structures.

FIG. 4.5. Quantities of structural fired clay or daub present.

FIG. 4.6. Structural fired clay or daub. Fabric percentages by number of fragments present.

Fabric C was the most prevalent, with only small amounts of fabrics D, F, H and I being recovered.

Various different attributes were observed in the assemblage. The external/internal surfaces were smoothed to give a finished appearance to structures. Finger grooves were present on some fragments, and a single fingerprint impression was preserved on a fragment of fabric A from dark soil 6300. Tools of metal or wood appear to have been used, in some instances, resulting in finer striation.

Of the 571 external/internal fragments, 35% were white-washed. The un-white-washed fragments may either represent internal surfaces, or show that not all buildings were white-washed.

The largest group was of fabric C, recovered from dump 6465. Of this, 264 fragments bore external/internal surfaces, 118 of which were white-washed. Ten fragments had curved surfaces, 3 convex and 7 concave, representing either curved corners of a structure, oven fragments, or internal features.

Twelve fragments bore a fine skim of like clay on the surface, 1 to 3 mm thick, and without the addition of coarse temper. This may be a result of a later batch of clay smoothed over an earlier batch, an attempt to cover a rough or cracked patch, or a technique to render the external surfaces more resistant to bad weather and/or improve the appearance of the structures. Wall daub at the Neolithic site of the Galgenberg, on the slopes of the Isar Valley in Bavaria was rendered with a fine, inclusion-free layer of daub, on the external surfaces (Wastling 1989, 25; Ottaway 1999, 217–26), although this was thicker than that at Flixborough.

The addition of a fine surface covering of daub would have had a threefold effect on the structures covered – two functional, and one aesthetic. The two functional aspects are to protect the fabric of the building from rain, and to facilitate better white-washing – a less permeable surface needing less white-wash. The aesthetic aspect is that buildings treated in this way are likelier to appear clean, well-constructed and superior to buildings treated in a lesser fashion.

FIG. 4.7. Incidence of structural fired clay by type of context.

Thirteen fragments show evidence of the inside of structures being left rough and unfinished, with the clay being extruded between the wattles. The effect of gravity can be seen in these pieces, as the extruded clay has sagged downwards before drying, giving evidence of fragment orientation.

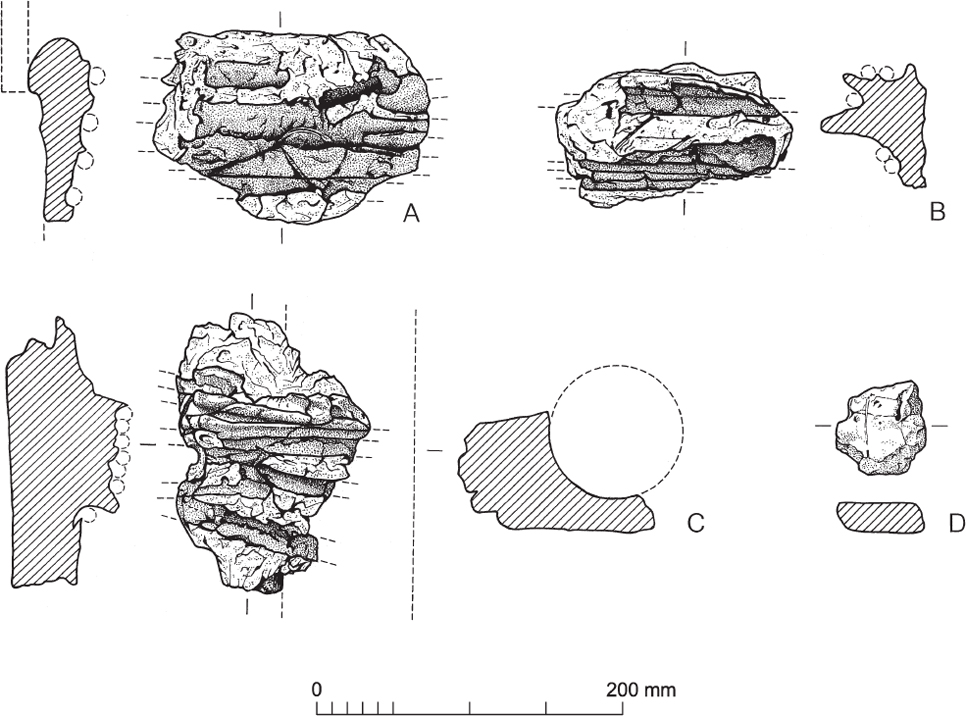

An upper wall fragment is represented in the daub from 12925, the demolition of building 13 (FIG. 4.8, fragment A). There is delineation between the smoothed and white-washed area and the top of the fragment, which is curved. Two deep finger impressions can be seen where the daub has been pushed up under the angle of the roof, and the surface becomes rougher towards the top. This fragment has a thin skim of like clay under the white-wash.

The depth of the daub at 24 to 45mm suggests that the wall thickness was narrow, with the wattle part of the wall having no load-bearing capacity. A longitudinal piece of cleft planking attached to the wall plate could have created the angle into which the daub appears to have been pushed. Daub not filling this angle completely would have created the curved top. The external white-washed surface of this fragment is well smoothed, and also appears to have been unaffected by inclement weather. Planking may have given additional protection to the junction between daub and roof, or, conversely, the fragment was part of an internal surface belonging to a building with a white-washed interior.

Impressions

Wattle diameters were measured on fragments with two or more impressions, where rod and sail could be differentiated. Templates with 5mm increments were used. In effect each template measures a range of diameters; for example the 10mm template group will include wattle impressions of 10 to 14mm diameters, and the 15mm template 15 to 19mm, and so on.

The diameters for rods ranged from <10 to 20mm, and sails measured 15 to 35mm (FIG. 4.9).

The degree of overlap between rod and sail diameters at Flixborough compares favourably with those of Iron Age date from feature P878 at Danebury (Poole 1984a, fig. 4.74), and with modern hurdles made as an experiment during the Somerset Levels project (Coles and Darrah 1977, 32–8). Wattle impressions of mid 7th to 8th century date from Victoria Street, Hereford (Shoesmith 1985, fiche M7.F5) varied from 10 to 30mm in diameter, though rod and sails were not differentiated.

FIG. 4.8. Wall daub fragments. Scale 1:4.

FIG. 4.9. The size range for wattle rods and sails.

In instances where the hurdles themselves have survived, measurements should be taken from each end of the sails (as the diameters taper towards the top) and a single sample from each rod across the width of the hurdle, or every two metres for continuous wattle (Morgan 1988, 79). Unfortunately, impressions from the Flixborough daub represent only small sections of wattle, the position of the diameter measurement on the stem length remaining unknown.

All the fragments used appear to have been complete stems, with no cleft wattles.

Usually sails have been used singly; however, three instances of wattles being woven around a double sail were recorded, and were all on daub of fabric C. One came from dump 6465, with sails measuring 30mm in diameter; a second impression had too little of the diameter to measure; a third came from the demolition layer of building 13, 12925, and measured 20mm and 30mm. As these examples are of comparable diameters to the single sails, they are likely to represent either repairs to panels, needed when sails were broken during construction, or stems bent back upon themselves – as postulated at Rowland’s track, Somerset (Coles and Orme 1977, 47).

A double rod was recorded on an unstratified fragment of fabric C from area C. As the diameter of each is less than 10mm, two may have been used together in this instance to avoid creating a weak spot in the panel (FIG. 4.8, fragment B).

Impressions other than those from wattles were visible on some fragments. Cleft timber impressions, possibly indicating planking, were noted on 21 fragments of fabrics C, D, E and I. Six were present on fabric C from dump 6465.

The largest impression represented is unfortunately preserved on unstratified daub of fabric C. It is an upright post of 85mm diameter, which would have lain flush with the external wall surface, if a cleft post, or would have protruded from the surface if complete. The impression of the wattle panel can be seen on the reverse of this piece (FIG. 4.8, fragment C).

Timber and underwood resources

If the daub-yielding structures, such as building 13, were fired deliberately for demolition, this precludes the reuse of structural timbers and would seem to indicate that the acquisition of timber was not problematical. The large upright posts, such as that which left its impression on the unstratified fragment of fabric C, were probably obtained from long-term coppice or standard timber trees left to grow in coppiced woodland. Standard trees would also have provided wood for cleft planking.

A prerequisite for the construction of wattle and post-built structures is the availability of a regular source of straight roundwood of suitable size and species. Coppiced woodland was probably the source of this material.

The two most likely species are hazel (Corylus avellana) and willow (Salix sp.), both of which respond well to coppicing. These species grow in different habitats. Hazel is usually associated with oak woodlands (Orme and Coles 1985, 9) and mixed woodlands of ash, maple and hazel (Rackham 1980, 203). Willow, which will tolerate flooding, usually grows in a wet environment (Orme and Coles 1985, 12); willow probably grew close to the site at the base of the Lincoln Edge in the lower Trent Valley. These trees are likely to have been managed, as are the pollarded willows of medieval and more recent date in Cambridgeshire today (Rackham 1986, 228–9).

Rackham (1994, 9) notes the quantities of woodland in upland Lincolnshire recorded by the Domesday Survey of 1086, with wood-pasture covering 1.6%, underwood 1.5%, and wood ‘pasturable in places’ 0.9%. Overall, Lincolnshire had 3% wood coverage in 1086, according to the Domesday survey (Rackham 1986, 78). Manley wapentake, which contains the excavation site, had 682 acres of underwood, plus underwood 2 leagues in length and 1 league in breadth, according to the Domesday survey. Of the two adjacent wapentakes, Corringham had 266 acres of underwood and underwood half a league in length and half a league in breadth, whereas Axholme had no underwood recorded (Foster and Longley 1924). The nearest recorded source of underwood to the site was Flixborough with 120 acres (ibid., 148).

Nottinghamshire had greater woodland coverage of 12% (Rackham 1986, 78), and the proximity of the River Trent to the settlement at Flixborough would have enabled these resources to have been utilised, in addition to those of the immediate hinterland of the site.

The reason why Lincolnshire had so little woodland recorded at this time is that much of the county had a wetland environment (see Volume 1, Ch. 1.2; and Volume 4, Chs 3 and 4). Other areas of wetlands, such as the Isle of Ely, Cambridgeshire and East Yorkshire also feature at the bottom of the table of woodland area by percentage as attested by the Domesday record (Rackham 1986, 78). Woods recorded in Domesday were those of use for tax collection, such as the demesne woodlands of manorial holdings (Munby 1991, 380); the managed trees of boundaries and watercourses, such as willow, are under-represented, and perhaps more underwood resources were to hand than is apparent in the Domesday accounts.

The maintenance of the wetland environment and prevention of woodland cover may have occurred in order to preserve a wetland economy. The flora is likely to have been dominated by grasses, some of which would have been valuable for thatch, others as grazing.

As managed woodland is a sustainable resource, it is likely that the source of the timber and roundwood was less than 20 miles from the site. Rackham (1980, 144) states a similar case for the medieval period, and it is not unreasonable to assume that the same distance would be logical for the 7th to 11th centuries.

The hearths

The main fabric used for hearths was A. This represented 45% of the total assemblage by number of fragments (FIG. 4.6). However, this distribution is skewed by the fact that the building 3 hearth (context 466) was collected in its entirety.

The fragments of this hearth have flat smooth surfaces and vary in thickness from 15 to 30mm (FIG. 4.8, fragment D). Many are tapered in section, and pieces with vitrified upper surfaces are deeper than unvitrified fragments, suggesting that the hearth was thicker in the centre where heat was most intense. Part of the surface was constructed of re-used Roman tile, some of which showed a vitrified glassy deposit on the upper surface. This was placed on the hearth whilst the clay was still wet, as there are narrow ridges of raised clay on some fragments between flat regular impressions of the tile. Some fragments of vitrified material have impressions underneath with right-angled corners, suggesting that they were laid on top of tiles. Possibly more than one layer of hearth material is represented.

This hearth appears to have been formed on a wooden framework: some of the vitrified pieces have possible wattle impressions, though too fragmentary to measure, and two have impressions of cleft wood, possibly part of a framework or timber base.

Saxon hearths from excavations at the Royal Opera House, London (Blackmore et al. 1998, 61) bear similarities of construction – some being timber-edged, and others incorporating Roman tile. The re-use of Roman tile in hearths is a common occurrence as also evidenced at sites such as Cowdery’s Down (Millett and James, 1983) and West Stow (West 1985, vol. 1, 18–22).

Hearth daub was found adhering to 38% of the Roman tile and brick at Flixborough (percentage by weight), though only in the cases of hearths 466 and 7152, and ovens 7288 and 8635, was the material in situ. These ovens and hearths date from the 9th to 10th centuries, though re-deposited tile with hearth daub occurs from Phase 2 onwards. The one hearth context where tile without adhering clay was collected was 1964 (see the Roman tile report, Ch. 14.2.3, below). The lack of tile from other hearths is more likely to reflect the excavation method and sampling strategy for most of the hearths, rather than any suggestion that the other in situ hearths contained no re-used tile.

4.3 Window glass and lead cames

by Rosemary Cramp

Window Glass (FIG. 4.10 and PLS 4.1–4.2)

The window glass from the excavations at Flixborough is durable, thin, and finely grozed, and one group (Group 1) closely conforms to the type found elsewhere on Anglo-Saxon sites in Northumbria and Mercia: at Beverley (Henderson 1991), Brixworth (Hunter 1977), Dacre (Newman in prep.), Escomb (Cramp 1971), Repton (Cramp in prep.), Wearmouth and Jarrow (Cramp 1970, 1975; 2006a and 2006b), Whitby (Evison 1991, 143–4), and Whithorn (Cramp 1997). Like the glass from these other sites, it is apparently made in the soda-lime-silicate tradition (see Mortimer, Ch. 2.2, above), and is cylinder-blown, as is evidenced by the flame-rounded edges in no. 1372 (RF 5567) and the elongated bubbles which are visible in several pieces (PLS 4.1–4.2; compare Harden 1961, and Henderson 1985). The bluish tinge of the colourless metal is also typical of the ecclesiastical sites already mentioned, as is the fact that on those sites which have produced only a few fragments, such as Escomb or Brixworth, the strongly coloured pieces are mid blue and brown/amber. None of the rarer colours, such as emerald, turquoise, red or red-streaked, is present in this sample. It should be noted, however, that finds in the past have come usually from documented sites, and this site, like Brandon in Suffolk (see Cramp forthcoming), cannot be identified in contemporary documentation, and so one cannot speculate about the likely sources of its glass. The ‘uncoloured’ fragments from Brandon (a site in which, like Flixborough, the excavated buildings are wooden) are in many cases different both in the base colour and in thickness (ibid.).

Group 2 from Flixborough is clear and colourless with dulled surfaces (PL. 4.2), and if it had not been found in stratified contexts, would have been assigned, on physical appearance alone, to a post-medieval period. The scientific analysis (see Ch. 2.2, above, and especially FIG. 2.5) has confirmed its difference from the rest of the glass, but also has demonstrated that it is not like medieval glass. As more analyses of chemical compositions are being undertaken, both in Britain and on the continent, changes in the compositions of glass in about the 9th century have been noted, and these Flixborough pieces may reflect the same trend (see Brill 1999 and 2006; Cramp 2000, 105–7).

Flixborough has produced neither complete quarries nor fragments which enable an interpretative reconstruction, and the shapes of the early lead cames do not indicate that the glass was cut into complex shapes (see below), as for example at Wearmouth-Jarrow, but this may not be a representative sample from the site.

Whether these fragments derive from the timber buildings in the excavated area or have been deposited as debris from buildings elsewhere is debatable, but since the discovery of a substantial amount of coloured and plain window glass from Whithorn – where there are only timber or half-timbered buildings – the use of window glass cannot be assumed to have been confined to mortared stone buildings (Cramp 1997, 329). All of the contemporary references to window-glass in Anglo-Saxon England are describing ecclesiastical buildings (Dodwell 1982, 63–4), but this may be because of the bias of the written evidence, and small quantities of window glass have been excavated at secular sites such as Southampton, Thetford or Old Windsor (Harden 1961, 53–4). Nevertheless, strongly coloured window glass has so far, in Anglo-Saxon England and elsewhere, been found only on ecclesiastical sites, or in relation to ecclesiastical buildings. It is possible, however, that the window glass at Flixborough (which first appeared either at the very end of Period 3 or more likely, as with the window lead, during Period 4, when it was most common), could have derived from a church elsewhere in what was primarily a secular site. Glazed windows, however, must always have been comparatively rare in the pre-Conquest period, and the discovery of the glass at Flixborough certainly indicates a site of some status.

Lead cames (FIG. 4.11)

Lead cames for windows are not as frequent an occurrence in pre-Conquest contexts as is window glass, and they have received comparatively little research attention. If Anglo-Saxon window glass can be dated only within brackets between the 7th and 9th centuries on the one hand, and between the 9th and the 11th centuries on the other, lead cames are even less susceptible to precise dating. This is probably because not enough comparative work between sites has been done, but also because – as in this collection – cames, like other lead artefacts are easily recycled, and lead was an expensive commodity. The recycling of lead is reflected on the site in the presence of numerous pieces of lead melt and also ingots (Wastling and Rogers, Ch. 11, below; Mortimer ADS research archive, analysis of lead melt).

FIG. 4.10. Anglo-Saxon window glass fragments. Scale 1:1.

Although the setting of glass in leads had begun in the Roman period, and is attested on the continent in the Merovingian period (Lafond 1966, 21–3, 27–8); leading only seems to have been widely used in Europe after the end of the 8th century (Whitehouse 2001, 39). Lead settings for panes were, at the time they were introduced into Anglo-Saxon England, only one method of holding glass: wood, stone, and stucco were also used. I have suggested elsewhere that glass could have been held in thin wooden strips at Whithorn (Cramp 1997), and this collection from Flixborough is important because it could throw additional light on the problem of how leaded windows were set in timber buildings.

This particularly applies to the distinctive group with very wide grooves which are cut into short straight sections and pinched together at each end (FIG. 4.11). These pieces may be considered as objects of reuse, for example, cut from longer strips to serve as net sinkers, but there are similar pieces at Jarrow which occur in Middle Saxon contexts (Cramp 2000, 201, pl. 4; Cramp 2006c, fig. 26.6.18). The Flixborough pieces have a distinctive patina, a sandy encrustation, which may mean that they were cast in wooden moulds in sand; one piece no. 1391 (RF 4099; FIG. 4.11) retains the marks of the wooden casting moulds on its surface. These short pieces are fairly inflexible and have been shaped by filing when cold.

As well as the thick leading, there is also evidence in no. 1416 (RF 7380) of lead cut into narrow strips, which might, like some of the fragments from Wearmouth-Jarrow have been part of a pattern applied to the surface of the glass (Cramp 1970, 329; Cramp 2006c, fig. 26.6.17). Nevertheless, one has to assume that the grozed and very thin window glass from this site must have been set in finer and more flexible leading of H-shaped section as has been found elsewhere, although window lead is never found on early medieval sites in large quantities (Stiegemann and Wemhoff 1999, 163, 183–4, and ills 64, 92, 93, provide useful continental parallels, including a stone with grooves which has been identified as a casting block for cames).

FIG. 4.11. Anglo-Saxon lead window came fragments. Scale 1:1.

The lead cames and window glass make an appearance, not surprisingly, in the same period of the Flixborough site development, but this could indicate dismantling or replacement of windows at that time, and all but two glass fragments come from refuse deposits dating undoubtedly from the end of that period – the middle decades of the 9th century, when major demolition and levelling is suggested, in Phase 4ii (Loveluck and Atkinson, Volume 1, Ch. 5; Loveluck, Volume 4, Ch. 2). The three pieces of glass incorporated into the surface of the latest deposits of Period 3, are equally likely to date from the same demolition phase sometime in the mid 9th century, and the lead cames are also concentrated in deposits of Phase 4ii and later, as refuse was re-organised within the site (Loveluck, Volume 4, Ch. 2). The surviving fragments may though give a distorted picture as to the appearance of the windows, if the main portion of the leading has been recycled, but this is a problem which Flixborough shares with all other Anglo-Saxon sites.

Catalogue

Window glass (FIG. 4.10 and PLS 4.1–4.2)

(Maximum measurements are given for these irregular fragments)

ANGLO-SAXON (GROUP 1)

1371 |

Fragment, many small elongated and rounded bubbles, surface striated, one grozed and two broken edges. |

1372 |

Two joining fragments, very many elongated bubbles. One edge is thickened and may have been the end of a cylinder, but the piece is warped and the surface distorted by heat. |

1373 |

Fragment, many fine elongated bubbles, surface pitted, and dulled by re-heating. |

1374 |

Fragment with one grozed edge, many small rounded bubbles, both surfaces glossy, one side heat-cracked. |

1375 |

Fragment, many tiny rounded bubbles, both surfaces glossy. |

1376 |

Fragment, possibly of the corner of a quarry. One finely grozed edge and another partly grozed, both surfaces glossy. |

1377 |

Fragment with many fine elongated bubbles, possible grozing on one edge. |

1378 |

Tiny fragment, surface very abraded and stained. |

1379 |

Fragment, elongated bubbles, slightly curved with abraded and dulled surfaces. |

1380 |

Sliver, many tiny elongated bubbles, surfaces dulled. |

1381 |

Fragment, many tiny elongated bubbles, one edge grozed. |

1382 |

Fragment, two glossy surfaces, small rounded bubbles, heat-cracked. |

1383 |

Fragment, surface dulled and some discolouration. |

1384 |

Fragment, surface dulled and dirty, probably re-heated in a fire. |

ANGLO-SAXON (GROUP 2) |

|

1385 |

Fragment, one glossy and one matt face. |

1386 |

Fragment, both surfaces dulled, traces of fine grozing. |

1387 |

Fragment, surfaces dulled. |

Anglo-Saxon lead cames (FIG. 4.11) |

|

1388 |

Came, H-section, casting mark and pin mark. |

1389 |

Came, pinched to a tapering point at each end, file marks, one rounded and bevelled and one flat surface, pin mark in the centre. |

1390 |

Came, pinched to a point at each end, one rounded and bevelled and one flat surface, with wide deep grooving. |

1391 |

Came, pinched to a point at one end, cut at the other, one bevelled and one flat surface, one wide and one narrow groove/valley. Traces from the wood of the casting mould visible on the surface. |

1392 |

Came, pinched to a point at each end, one rounded and bevelled and one flat surface, wide grooving. |

1393 |

Came, triangular in section, pinched to a point at both ends, one broad shallow groove with central ridge, incision in upper surface. |

1394 |

Came, pinched to a point at both ends, one flat, one bevelled surface, one wide shallow groove, one narrow and deep. |

1395 |

Section of re-worked came, the groove is splayed and the two ends are blunted by the heating. |

1396 |

Distorted came, pointed at one end, cut at the other, domed top, one wide groove with casting line, one narrow groove, secondary cut. |

1397 |

Came, pinched to a point at each end, one end torn, one slightly bevelled, one flat surface, wide grooving. |

1398 |

Came, pinched to a point at both ends, bent and distorted in the middle. |

1399 |

Came, pinched to a point at each end, two bevelled surfaces, wide valley, pin mark. |

1400 |

Two cames, pinched to a point at both ends, two bevelled surfaces, wide shallow grooves. |

1401 |

Came, pinched to a point at both ends, bent and distorted. |

1402 |

Came, pinched to a point at both ends, filed to two bevelled surfaces. |

1403 |

Fragment, triangular in section, pinched at each end, possibly a re-melted or rejected came, shallow double groove on one surface and linear incision on the other. |

1404 |

Strip of lead with some evidence of working and possibly smelting. |

1405 |

Cut sliver probably from a came with part of a groove 4mm wide. |

1406 |

Partly melted lump, possibly once a came, pointed at one end and cut at the other, deep irregular groove. |

1407 |

Section of a came, cut at one end and pointed at the other, with one bevelled edge, one shallow wide groove, and one deeper narrower one. |

1408 |

Came, bent, and pointed at both ends, both grooves shallow and c.4mm wide. |

1409 |

Section of came, pinched together at both ends. |

1410. |

Distorted section of came, pointed at each end with wide grooves. |

1411 |

Fragment of came, pinched together at both ends and at the top, to form a triangular section, casting line in the open wide groove. |

1412 |

Section of came, twisted and tapering at both ends, possibly Anglo-Saxon. |

1413 |

Fragment, possibly of a came flattened for reuse, or discarded before completion. |

1414 |

Rod off-cut distorted by heat, possibly a form of came. |

1415 |

Featureless fragment of melted lead, possibly part of a came. |

1416 |

Fragment formed from very thin lead strips (0.05mm thick) soldered together on one edge, and open like a clip at the other. Function obscure. |

1417 |

Narrow off-cut. |

1418 |

Section of narrow came formed of thin lead sheets (0.05mm). |

1419 |

H-section came with a straight length joined to an angled T-fragment. In appearance it is very different from those cames retrieved from the Phase 4ii and 5a deposits. |

4.4 Other building materials

As will be apparent from the structural accounts presented in Volume 1 of this series (see Loveluck and Atkinson, Chs 3–7), a number of padstones were found associated with the excavated buildings. Lithological identifications of all of these, together with their description and dimensions are included in the research archive which can be accessed on the ADS website.

Similarly, a very limited amount of charred structural timber was recovered during the excavations. This was looked at during the assessment stage, but its fragmentary nature meant that no further analytical work would have been justified. Once again, details of this material can be found in the research archive on the ADS website.

Lastly, it should be emphasised that the soil conditions prevalent on this site have meant that any organic building materials which would have been in use would either be absent or drastically under-represented in the archaeological record: these would include all timber components (as used in walling, roofing, and the construction of doors, shutters, etc.), organic roof coverings (such as wooden shingles or thatch), woven hurdle or matting screens, etc., and any ropes used to hold roof coverings in place.