14 Prehistoric, Romano-British and High Medieval Remains

Chs 1–13 have examined the evidence for activity at this site between the 7th and the 11th centuries. This chapter examines the material evidence for all other activity at this multi-period site.

The earliest artefactual material comprises an assemblage of flints, ranging in date from the Mesolithic to the Early Bronze Age. Iron Age activity is attested by finds of hand-made pottery and sling-shots.

The earliest structural activity on the site is represented by some probable later Roman deposits and cut features (see Volume 1, Chs 3 and 4). Not only was a small amount of Roman material associated directly with these, but the excavations also yielded a substantial collection of Roman coins, pottery, ceramic building materials, a penannular brooch, a jet pin, and fragments of worked stone, in later contexts; there is also a fragment of tessera (see Ch. 2.1, p.108. no. 947). Whilst some of these finds from later contexts, along with unstratified material, may relate directly to the Roman occupation of this site, there is also material present which has clearly been brought onto the site from elsewhere – e.g. the possible fragment of a stone altar and the tessera, which have probably been introduced onto the site with building materials robbed from a nearby higher-status Roman site, such as could be found locally at Dragonby or Winteringham.

Medieval and later activity is represented by a small collection of pottery, coins, metalwork and a stone roofing tile.

***

14.1 Prehistoric remains

Small quantities of prehistoric worked flint were recovered from most of the areas examined, indicating some form of exploitation of this ridge at intervals between the Mesolithic and the Beaker period: though certainly noteworthy, the occurrence of Mesolithic material on this site is by no means unique for the area. Later evaluations in 1997 on an area to the north demonstrated that there had also been extensive Iron Age activity on the same ridge: this has helped to put some of the residual Iron Age material from the 1989–91 excavations into context. The residual Romano-British material recovered amongst the Anglo-Saxon settlement remains also seems to be largely derived from the near vicinity of the excavated site; whilst the 12th- to 14th/15th-century artefacts are likely to reflect peripheral activity at the western extremity of the settlement or settlement foci comprising North Conesby (Loveluck and Atkinson, Volume 1, Ch. 7; Loveluck, Volume 4, Ch. 2).

14.1.1 Prehistoric lithic material

by Peter Makey

Note: the term cortication is used throughout this report to identify the natural discoloration of a flint’s surface resultant from the internal re-formation of cortex on a struck surface. Care must be taken to avoid confusion with the term cortex, which is used for fully formed cortex (i.e. a flint nodule’s ‘skin’). Patination is taken to imply an often waxy discolouration of a flint caused by external resilification (cf. Shepherd 1971, 117). Areas where lithic remains were recovered are referred to by ‘site area’ (see Loveluck, Volume 1, Ch. 2, FIG. 2.3).

The excavation produced a total of 95 (567g) pieces of prehistoric struck flint. Despite the residual nature of the assemblage, only 23 pieces (24%) exhibit signs of breakage. Eight pieces of flint were originally allocated recorded finds (RF) numbers, but have been catalogued as natural and have been subsequently discarded.

A large proportion of the stratified material derives from the fills of post-holes.

The assemblage composition, character and phases of deposition are given in FIGS 14.1 to 14.4, hence they are not individually catalogued.

ASSEMBLAGE STATE AND DISTRIBUTION

A markedly high proportion (24%: 23 pieces) of the material is in a fresh state that does not appear consistent with its contextual residuality. Some of the freshest-looking material comes from unstratified contexts.

Forty percent of the material (38 pieces) exhibits traces of cortication to varying degrees. There is some disparity in the degree to which different typological forms have been corticated. This is most notable with regard to the blades and bladelets, of which respectively four (80%) and eight (80%) pieces exhibit this trait; compared with 14 (46.6%) of the flakes. The blades and bladelets are also the most corticated pieces in the assemblage; cortication tends to be extensive and light grey to white in colour. Only three of the scrapers (25%) exhibit this trait.

Major movement of archaeological deposits is reflected in the distribution and state of the lithic assemblage.

RAW MATERIAL, REDUCTION TECHNOLOGY AND SEQUENCE

Most of the struck pieces have been manufactured on flint that appears to have been derived from the local gravels or boulder clay. The flint is predominately light olive-grey to olive-grey in colour (Munsell 5Y 4/1–5Y 6/1) and, where present, the cortex is of a smooth brownish pebble variety. Two of the chunks (RFs 14361 and 14362) may have been obtained from local estuarine or beach sources. A single, yellowish-grey (Munsell 5Y 8/1) flake is the only piece that does not appear to have come from the above sources: this piece looks consistent with material found in small quantities in the lower chalk of the Yorkshire and Lincolnshire Wolds.

The majority of the struck pieces can be assumed to have been knapped via the application of hard hammer technique. A hard hammer-stone was recovered (RF 14279) from area E (no. 3290, below).

An unstratified discoidal core (RF 1954) from area T has re-flaked cortical facets.

More than 50% of the assemblage comes from tertiary stages of lithic reduction; flints from primary reduction stages are virtually absent. It is probable that initial lithic reduction was carried out at the site of raw material procurement.

TRAITS

Most of the retouched implements have been moderately to heavily used – particularly the scrapers; however, about one-sixth of the un-retouched pieces exhibit traces of edge attrition, consistent with utilisation. Two un-retouched flakes (RFs 3550, 14378) and a blade (RF 13344) have been utilised to such an extent that the use wear resembles intentional retouch.

FIG. 14.1. Composition of the combined excavated and unstratified flint assemblage.

Traces of burning are present on only nine (9.5%) of the pieces. The distribution of this trait is uneven, but it is notable that five of the burnt pieces are from site area E, although there was no correlation with specific feature types. The burnt material deposited in area E (the shallow valley leading into the centre of the excavated area) is consistent with material that has been in or near a fire.

The flints

CHUNKS

The non-bulbar component of the flint assemblage is proportionally high, being in the ratio of c.1: 7.6.

Three of the chunks have been rolled, and all are of olive-grey flint. Eight pieces (c.73%) retain cortex and represent secondary stages of lithic reduction.

FLAKES, SPALLS, BLADES AND BLADELETS

Although there are too few intact pieces in the assemblage for any useful statistical analysis to be conducted, some basic traits can be discerned. The breadth: length ratios of the debitage is summarised in FIG. 14.3. Only 20% of the flint flakes are broken. Forms vary, but most are squat and semi-regular with lengths predominately in the 9–23mm range, and breadths in the 10–26mm range. Striking platforms are predominately single-flaked and uncorticated. Over 58% (14) of the intact pieces are from tertiary stages of lithic reduction. There is no apparent size differentiation between corticated and uncorticated flakes. The assemblage contains only one piece (RF 13486) that has been classified as a spall (here defined as a flake of less than 10mm in length).

For recording purposes, the blades have been divided into blades and bladelets, following the criteria defined by Tixier (1974). Bladelets are here defined as blade-like pieces with a length of less than 50mm and a width of less than 12mm. The length should typically be more than twice that of the width.

Half of the bladelets are broken, yet breakage has occurred in only one (20%) of the blades. Crested forms predominate in both the blades and bladelets – 10 pieces being single-crested, and three being double-crested. Most specimens are fine, with almost parallel sides. Of the intact blades and bladelets, only one example retains any trace of cortex. There was a slightly higher incidence of bladelets being recovered from post-holes than from other contexts.

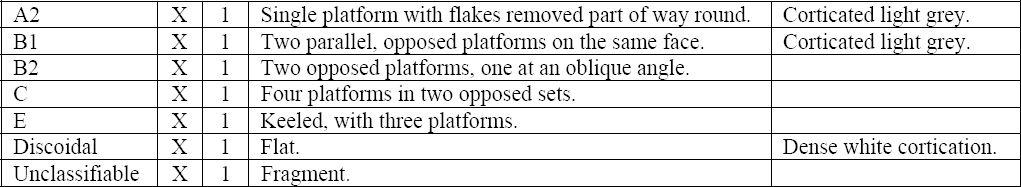

CORES AND CORE-REJUVENATION FLAKES (FIGS 14.2 TO 14.4)

The Hurst Fen (Suffolk) system (J. G. D. Clark et al. 1960) has been used to classify the cores. Seven cores are present in the assemblage: six are intact, the remaining fragment is unclassifiable. The pieces are in varying states of freshness, and despite the fact that three of the cores come from post-holes, there is no discernible spatial patterning to their distribution. Their incidence is given in FIGS 14.2 to 14.4, and the typological forms are set out below.

Dimensions vary, with maximum lengths between 26 and 39mm, and maximum breadths in the 21 to 33mm range. Weights range from 8 to 24g, with the mean average being 15g. All examples exhibit flake removals: these are typically small and squat, being in the 20 × 10mm range. The average number of removals is nine, with most cores appearing to have been worked to exhaustion. Two of the cores (class B1, RF 11665, and class A2, RF 14370) possess a very light degree of light grey cortex, and the unstratified discoidal core has a dense white cortication. The assemblage contains only one core-rejuvenation flake (RF 1636, context 1449): this is a burnt, chunky cortical removal that has been struck down the face of a core, and retains traces of five small flake removals.

UTILISED FLAKES AND BLADES

Two flakes (RFs 3550, 14378) and one blade (RF 13344) possess a higher than usual degree of edge attrition, that is consistent with the pieces having been used as knives.

RETOUCHED IMPLEMENTS

The assemblage includes six pieces that possess miscellaneous retouch that cannot be classified. Five were manufactured on flakes, and one (RF 14377) on a chunk. Two of these implements (one flake, one chunk) were manufactured on thermal removals. One retouched flake (RF 3175) resembles the initial stages in the production of an arrowhead; it is likely that this piece represents an abortive attempt to produce a leaf-shaped arrowhead.

THE EDGE-RETOUCHED FLAKE

The sole edge-retouched flake (RF 5328) came from dump deposit 3891. This piece is a heavily damaged, plunging secondary flake, with a trimmed platform and an un-retouched convex distal end. It resembles a long end-scraper in form, although the retouch is on the right-hand margin. This retouch is crude, irregular and minimally invasive.

THE SERRATED-EDGED BLADE

A fragmentary, double-crested, serrated-edged blade (RF 4181) was recovered from the fill of a post-hole (context 4177). The distal end of the piece has been snapped after loss. The implement has received backing retouch on its right-hand side, and has been serrated on its left-hand margin. These serrations consist of 12 very fine teeth of 1mm depth and 1mm breadth, which are slightly abraded. It is probable that this implement has been heavily used.

MICROLITHS

The microliths comprise a scalene triangle (RF 1416) from a post-pad (context 1293) in Area E, and an edge-blunted point of rod form (RF 7215); the latter example came from the fill (context 7210) of a post-hole in area D. The scalene triangle has been manufactured in fine-grained light olive-brown (Munsell 5Y 5/6) till flint. The edge-blunted point was manufactured from fine-grained, olive-grey (Munsell 5Y 4/1) till flint. Neither of the pieces is corticated, and both are in a markedly fresh state. They are consistent with the microlithic assemblages of the later Mesolithic; regionally, many microlithic assemblages are known, of which Risby Warren is the most notable (Riley 1978).

Microliths similar to the Flixborough examples are also known from local assemblages dominated by nongeometric forms: for example, the site at Hall Hill, West Keal (May 1976, 35, fig. 18) contains comparable pieces, although the majority are non-geometric forms. Jeffery May (ibid.) has contrasted the Hall Hill material with the assemblage from Sheffield’s Hill, near Scunthorpe: on the basis of their smaller forms, he proposed a date around the 6th millennium bc for these local sites. Nationally, geometric assemblages tend to be of mid 7th millennium bc date (Jacobi 1976); hence, a mid 7th to 6th millennium bc date would appear to be probable for the Flixborough examples.

Backed-blades

THE ARROWHEAD

A single arrowhead is represented by a slender basal fragment of an unstratified, almost kite-shaped leaf type of Green’s (1980) size 3, form Cu (RF 50009). The piece has been manufactured on a fine-grained olive-grey till flint (Munsell 5Y 4/1); its breakage appears to be post-depositional. Regionally, this is a middle/early later Neolithic form, slightly larger examples of which occur with burials of the Duggleby phase (Green 1980, 85) c.2700–2150 bc (Manby 1988, 38). A leaf-shaped example of similar size, though slightly less pointed form, is known from the nearby Neolithic site of Normanby Park (Riley 1973, 59, fig. 24).

PIERCERS AND POINTS

There are two examples of points/piercers in the assemblage (RFs 6476 and 13545). One example (RF 13545) is formed by bi-lateral retouch of a broad spurred flake, and was found in the fill of a pit (context 12243) in site area F; the other example came from a layer in area B, and is a broken piece of sub-triangular form. This latter piece possesses a fine straight, bifacial scalar retouch along one of its lateral margins, and a right-angle formed by the conjunction of this and an area of straight transverse retouch. The opposed lateral margin has abrupt, slightly convergent, convex retouch; the convergence appears to be forming a point, but this has been snapped. This implement bears some similarity to a chisel arrowhead, but the striking edge would appear to be too blunted for such a use. The intact example (RF 13545) possesses heavy macroscopic traces of use, whereas the broken example possesses micro-wear. These are probably of later Neolithic or Early Bronze Age date – a period which is poorly represented in the published flint assemblages of North Lincolnshire.

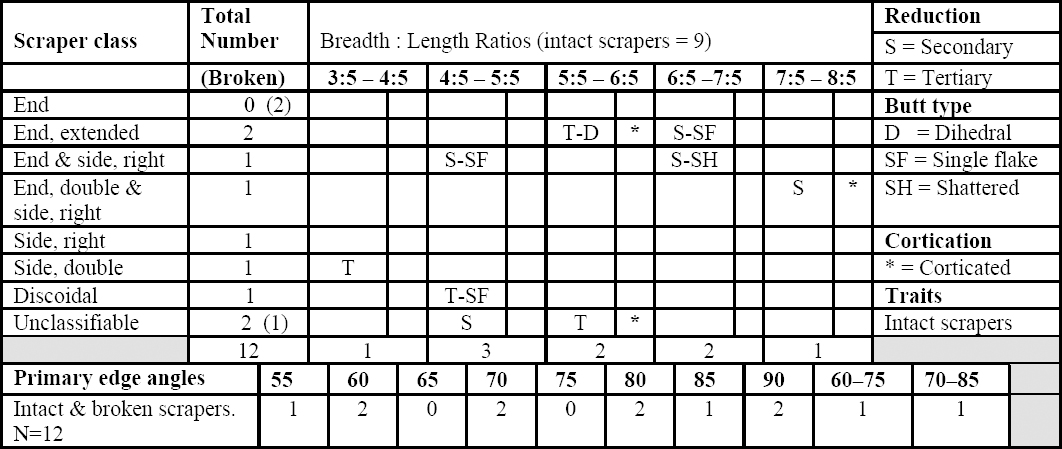

The scraper assemblage contains 12 examples of a variety of forms. Their morphological traits are summarised in FIG. 14.4, and their overall distributions in FIGS 14.2 and 14.3.

Most are small, with lengths ranging from 16 to 40mm, and with the average being 24–25mm. Breadths range from 16–36mm with no preferred breadth, although the median average is c.21mm. The preferred breadth : length ratio lies in the 4:5 to 6:5 range. Their thickness varies from 5 to 12mm. The only scraper showing traces of platform (butt) preparation (RF 4713, context 2722) is a lightly corticated extended end-scraper from area A/B. Primary flake edge angles vary, and all examples exhibit traces of utilisation.

Five of the 12 scrapers (c.42%) were found in post-holes. Four of these came from one post-hole (context 2127, RFs 14368, 14375, 14376) in area F: these comprised two unclassifiable forms (one of which was fragmentary), plus one lightly corticated example that had been retouched on both ends and its right-hand margins, and one that had been retouched along both lateral margins. A small extended endscraper (RF 7254) from a wall foundation (context 1731) in area B was of ‘button’ form, and of a type that is most frequently found in the region’s Beaker assemblages.

Some of the smaller scrapers are consistent with examples from Mesolithic and Beaker sites. Nationally, the relatively small dimensions of these scrapers compare favourably with Beaker-associated specimens from beneath round barrows at Chippenham, Cambridgeshire and Reffley Wood, King’s Lynn, Norfolk (Healy 1984, 10). Regionally, they are of notably smaller dimensions than the material from Normanby Park (Riley 1973), and compare favourably with possible Beaker examples from Risby Warren, Area 10 (Riley 1978, 10).

14.1.2 The hammer stone

by Lisa M. Wastling

A hammer stone was recovered from 10th-century dump 3730. This object appears to be the result of the ad hoc use of a burnt stone, possibly originally from the edge of a hearth.

Given the presence of the admittedly small but constant element of Romano-British and Iron Age material in the area of excavation, this is probably a residual find.

Two hammer stones were found in late Saxon and early Medieval deposits during the excavations at Cheddar (Rahtz, 1979, 236), though they too are potentially residual.

Catalogue

Lithological identification by Geoff Gaunt

3290 |

Hammer stone. |

FIG. 14.4. Scraper typological form.

by Peter Didsbury

A total of 10 sherds of prehistoric pottery, weighing 587 grams, was submitted for examination. All this material was apparently extracted from the context sequence at an early stage of the post-excavation process and bagged together as ‘Vessel 20’ (drawing no. 344), though it is now clear that an estimated three vessels are present. Much of the material is unmarked or marked ‘U/S’, and there is a high degree of discrepancy between the markings on sherds and those on the packaging. The individual vessels are described below.

Catalogue (none illustrated)

3291 |

Seven body and base sherds, weighing 499 grams, from a large jar with a basal diameter perhaps as large as c.200mm. Average wall thickness is c.15mm. The fabric is hard-fired and tempered with abundant fine sand, together with sparse larger rock fragments, typically angular light-coloured flint, up to 4mm in size. The core is very dark grey and the surfaces are reddish-brown, well-burnished on the exterior and wiped smooth on the interior. Multi-directional wipe marks and striae are visible on the interior, as is the occasional grass or straw impression. The vessel appears to have been hand-built, though a slow wheel may have been involved in its manufacture. Two sherds have encircling decoration formed by broad grooves separated by ridges or cordons. Neither sherd represents the full extent of the grooved zone(s). |

3292 |

Two body sherds, weighing 83 grams. These are body sherds similar in all respects to those described above, except insomuch as they have a very dark grey interior surface and variable dark grey, reddish-brown and buff exterior. |

– |

[Un-numbered in the catalogue sequence]:. One sherd, weighing 5 grams. This is a wall sherd from a hand-built vessel, 15mm thick. The fracture shows a fully reduced interior and a light red exterior, these zones being of approximately equal thickness. The fabric is fairly hard-fired, with sparse to moderate amounts of mixed and ill-sorted stone temper, generally angular and dark-coloured, and up to c. 4mm in size. A Later Bronze Age or earlier Iron Age date might be appropriate. |

Sherds have been allocated to contexts wherever possible above. It should be noted that this group of material also contained empty packaging marked with the number 11711.

14.1.4 The sling-shots

by Lisa M. Wastling

Four fired-clay sling-shots were found during the excavation. One is of ovoid form, two are sub-spherical and the fourth is incomplete (though probably also sub-spherical). All four have small chips missing from their surfaces; whether this is the result of utilisation, or post-depositional damage, is not apparent. The complete examples vary in weight between 45 and 61g, and appear more consistent in size than weight – an observation also made by Poole at Danebury (1984b, 398).

Fired clay sling-shots have been found on Iron Age and Romano-British settlements in the region. At Dragonby, extensive excavation produced 56 examples (Waddington and May 1996, 340), whilst single examples were found at Winterton and Old Winteringham (Stead 1976, 226–7). Three out of the four sling-shots at Flixborough are sub-spherical. Whilst Greep (1987) appears sceptical of this form, examples have also been found at Dragonby (Elsdon and Barford 1996, fig. 13.10), and a possible example during excavation at Brough-on-Humber (Wacher 1969, fig. 47). For the distribution of sling-shots in Britain, see Greep (1987), and Elsdon and Barford (1996).

Slingers were commonly used in warfare in the Iron Age and early Roman period, and are portrayed on Trajan’s Column in Rome (Greep 1987, 192). Caesar in his De Bello Gallico mentions that they were in use by his own forces, and that the Belgae used them to assault Bibracte in 57BC. According to Waddington and May (1996, 340), this is the only direct reference to sling-shot being used in Iron Age warfare.

Sling-shot of three different media have been found in Britain: stone, fired clay and lead. Greep (1987, 183) associated lead examples with military sites of the Roman period, whilst Waddington and May (1996, 340) noted that stone sling-shots appear to be more common on hillforts, and that fired-clay examples are associated with smaller or undefended settlements.

Eight stone sling-shots were recorded at Dragonby, in contrast to 56 clay shot (ibid., 340); whilst 11 fired-clay sling-shots were recovered from the hillfort at Danebury (Poole 1984, 398), compared with over 12,000 sling stones (L. Brown op. cit., 425).

At hillforts, stock-piling of suitable stones would have been necessary, in order to be prepared for attack, and it is these hoards of stones which have been recorded; whilst on small undefended settlements, stone shot would have been collected in lesser amounts, perhaps when needed. These occasional finds could be easily dismissed as a natural occurrence, and, therefore, are likely to be under-recorded; whereas fired-clay examples, easily recognisable as man-made artefacts, are likely to be retained.

The use of the sling-shot at Flixborough need not be associated with warfare. The sling was a useful hunting weapon, and was possibly used for both game and wildfowl. It is certainly easier, and involves less manpower to manufacture clay sling-shot for hunting, than arrowheads – a factor that may have been taken into account, given the likely rate of arrow loss and breakage.

Ryder (1983, 737) mentions the use of slings in shepherding, to deter predators and to turn straying sheep back to the flock: and indeed they were used in this capacity until comparatively recently. They are mentioned, at least in literary terms, in early 17th century Spain. In Don Quixote (de Cervantes 1604: 1950 edition, 138) the shepherds used them against Don Quixote as he attacked their flock, having mistaken it for an army:

… they unbuckled their slings and began to salute his ears with stones the size of their fists.

Three of the Flixborough sling-shots were found in dump deposits of Phases 5a, 5b and 6ii, and the fourth in an occupation deposit of Phase 5a – with deposition dates ranging from the mid-9th to 11th century. It is likely that these sling-shots originated from reworked Iron Age deposits.

The majority of residual Iron Age and Romano-British pottery was also recovered from dump deposits: Iron Age features are now known to have existed within close proximity to the area of excavation. These were sealed by a layer of windblown sand in the same manner as the Anglo-Saxon phases of the excavated site (see Volumes 1 and 4).

Although the sling-shots are most likely to be of Iron Age date, there is a small possibility that they may have been used during the Saxon phases of the site – though the author is unaware of any being found that can be securely dated to this period. The sling-shots recovered from a 10th- to 11th-century ditch fill at Cheddar were in an assemblage which also contained residual Roman material (Rahtz 1979, 72); whilst two examples from West Stow belong to the Iron Age phases of that excavation (West 1990, 60–1).

Catalogue and fabric description (FIG. 14.5)

All four sling-shots are of very similar fine fabric. The clay may have been worked specifically for the purpose of sling-shot manufacture, or may have been a by-product of pottery production. The differences in colour are due to their being open-fired on a bonfire, and receiving uneven heat. The method used for fabric description was based on that recommended for pottery fabric recording, outlined in Orton et al. (1993, 231–42).

Colour |

ranges from black, 2.5/N through to dark grey 10YR 4/1, with the occasional area of light yellowish-brown 10YR 6/4, or yellowish-brown 10YR 5/4 |

Hardness |

hard |

Feel |

smooth |

Texture |

fine to irregular |

Inclusions |

abundant fine quartz sand. (Sparse grass/chaff observed in the broken section of |

3293 |

Sling shot, ovoid. Complete. The surface is cracked, and a small area has a vesicular appearance due to heat. |

3294 |

Sling shot sub-spherical. Complete. |

3295 |

Sling shot. Incomplete. |

3296 |

Sling shot. Complete, oval in shape, almost egg-shaped. |

14.2 Romano-British remains

We have already seen that there is evidence for extensive Iron Age activity nearby along the Lincoln Edge and the windblown sand spurs, which have built up against it; however, rather more evidence of Romano-British date was found, including the first possible structural evidence for activity on and immediately adjacent to the excavated site.

The contexts from which Romano-British finds were recovered fall into two main categories. There are a small number of cut features and deposits from the site, which contained mainly 4th-century material (see Loveluck and Atkinson, Volume 1, Chs 3 and 4). This 4th-century material is residual in the earliest Anglo-Saxon occupation periods. From Period 3, and especially in Periods 4, 5 and 6 earlier Romano-British artefacts (dating from the 1st to 3rd centuries AD) were imported and discarded in refuse deposits in the excavated area, showing that in parts of the Anglo-Saxon settlement the inhabitants were disturbing earlier Romano-British remains (see Loveluck Volume 4, Ch. 3). The field to the east of the excavated area has also produced quantities of Romano-British finds which have been found in field-walking.

The presence of a reused fragment of a portable altar recovered from the excavated site, from a Phase 6iii deposit, suggests that at least some of this Romano-British material has been robbed from a reasonably high status site, such as a villa (e.g. Winteringham, or possibly Dragonby), in the area, and has been brought onto the site during the Anglo-Saxon period for reuse as building material. It is possible that the single tessera recovered from the site (cat. no. 947, this volume, Ch. 2.1, above) could also have been robbed from a nearby Roman mosaic, although it could equally be an import of the Mid to Late Anglo-Saxon period. It is also possible that other items of Romano-British date are present amongst finds from Saxon contexts (e.g. amongst the ironwork).

14.2.1 The Roman coins

by Bryan Sitch

Twenty-three Roman coins found at Flixborough were examined and identified. Three of the coins date from the late 1st century/early 2nd century, three from the 3rd century and the rest (17) from the 4th century AD. All but three coins were firmly identified. The earliest coins are of the later 1st or early 2nd century AD, a commemorative denarius for Faustina I, wife of Antoninus Pius (AD 138–61), which was found fused together with another denarius (unidentified because of concretion) and a denarius in the name of Julia Mamaea, mother of Severus Alexander (AD 222–35). Two later 3rd century coins demonstrate the deterioration in the silver content of the denarius in its subsequent incarnation as the double denarius or antoninianus. Both are issues of Tetricus I (AD 270–3), and the reverse legends COMES AVG and SPES AVG are common.

The bulk of the coins date from the 4th century AD. Starting with a reduced follis of Constantine I (as emperor) with the legend COMITIAVGGNN, there are common issues and contemporary copies of the House of Constantine such as URBS ROMA, GLORIA EXERCITUS, and CONSTANTINOPOLIS dating from the 330s and 340s AD, three fallen horseman copies of AD 354–64 (no. 3311, unusually has the Roman soldier standing on the left, not the right), a copy of an issue of Magnentius (AD 350–3), and common issues of the House of Valentinian, including GLORIA NOVI SAECVLI (Gratian), SECVRITAS REIPVBLICAE (Valens) and two GLORIA ROMANORVM issues of Valentinian of the 360s and 370s AD. The sequence comes to an end with a VICTORIA AVGGG issue of Arcadius of the period AD 388–402, one of the last issues to arrive in Roman Britain before the province was abandoned early in the 5th century AD. The dates given are the dates of minting, not the date of loss or deposition.

The Roman coins from Flixborough are similar to samples from other Romano-British sites. They comprise common issues and contemporary copies, with the exception of the two coins that were clearly part of a hoard. Otherwise the sample consists largely of coins that are for the most part of small module, low precious-metal content, very worn, and presumably were of low value, or contemporary copies. For the most part these must represent the coins that the owners could afford to lose, and it is likely that they entered the archaeological record as rubbish.

During the later 3rd and 4th centuries AD periodic coin reforms, suppression of the coinage of failed usurpers and the supply of high value coins that were inappropriate to the needs of the population in the province resulted in a rapid turnover of the coins in common currency and waves of copying (Boon 1974; Reece 1987, 20). The coins represented in the Flixborough sample are mostly from periods when coin losses were more frequent: radiates and radiate copies of the later 3rd century AD, Constantinian issues and contemporary copies of the 330s and 340s AD, fallen horseman copies of AD 354–64 and Valentinianic issues of AD 364–78. The Flixborough sample includes only two radiates – of Tetricus I of AD 270–3 – and the bulk of the coins are of the 4th century AD. Even the very worn examples of the later 1st/early 2nd century could have stayed in circulation into the 3rd century AD. The relative scarcity of coins prior to the 4th century, however, need not necessarily denote absence of occupation of the site at that time because of the small size of the sample, but the predominance of 4th-century coins may well be significant.

In order to demonstrate this point, the Flixborough coins were compared with samples of coins from other Romano-British sites in North Lincolnshire. The interpretation of Roman coinage from sites in Britain has a well-established methodology (Casey 1974; Reece 1987). Usually the results of the coin identifications are plotted on a graph, such as a coin histogram, or presented in a table. Accordingly the information from the Flixborough coins has been presented in tabular form (FIG. 14.6); the coin periods ranging from Claudius (AD 43–54) to Honorius and Arcadius (AD 388–402), following the coin periods developed by John Casey (1980). It must be stressed that the Flixborough sample is too small to carry out this exercise with anything like a claim to authority, but it does demonstrate in a limited way to what extent these coins follow the familiar pattern of coin losses from rural sites in Roman Britain. In order to show how Flixborough’s sample relates to the local pattern of coin loss, the Flixborough results were plotted against those from other Romano-British sites in North Lincolnshire, namely Old Winteringham I and II and Winterton (FIG. 14.7) using the coin lists prepared by Peter Curnow (Curnow 1976). The data were converted into coin losses per 1000 coins to enable comparison of small samples like Flixborough with larger samples such as Old Winteringham I and II using the formula:

Allowing for the fact that the presence of a single coin in a small sample can give very high readings per 1000 coins, this exercise enables a number of points to be made. Prior to AD 260 when there is a marked increase in coin losses on most of the sites, only one site – Old Winteringham I – has high readings in the early 1st century AD, reflecting the site’s strategic importance at a time when the Humber Estuary formed the northern frontier of the Roman Empire, and this was commented upon in the coin report (Curnow 1976). The other sites show an apparently random scatter of occasional coin losses during the two centuries between AD 43 and AD 260. In Period 18 (AD 260–73) Flixborough has the lowest readings of the four sites. Thereafter, Flixborough’s pattern of coin loss is similar to those of Old Winteringham I and Winterton, although clearly a larger sample would make the comparison more valid statistically. The comparison shows that Old Winteringham II coin losses were very low during the 4th century, but the other three sites including Flixborough share a common profile, which is characterised by peaks and troughs, reflecting the vicissitudes of the Roman currency and repeated attempts at reform. The periods of broad similarity of coin loss are highlighted to make this clearer.

From this we can deduce that Flixborough’s very small sample follows the local and national pattern of coin losses on Romano-British rural sites. Admittedly, later 3rd-century radiates were not as common as might have been expected, but coin losses were high in Periods 23 (AD 330–48), 24 (AD 348–64) and 25 (AD 364–78). This characteristic profile is very familiar nationally and can be demonstrated on numerous sites in the East Riding of Yorkshire to the north of the Humber (e.g. Sitch 1998). Such a pattern of coin loss must reflect occupation of the site during the later 4th century AD. Absence of coin losses in particular periods such as Periods 19 (AD 273–86) and 26 (AD 378–88) merely confirms that the factors affecting these sites were inherent to the Roman currency and not site-specific. The relative scarcity of late 3rd-century AD radiates, however, could suggest abandonment or perhaps different usage of the site, but we need to make allowance for the very small size of the Flixborough sample. A larger sample might well prove to be more typical of the general pattern for rural sites.

Catalogue of Roman coins

FIG. 14.6 Chronological profile of the Roman coins from Flixborough (coin periods from Casey 1974, 1980).

FIG. 14.7 Chronological profile of Roman coin losses from sites in North Lincolnshire (results presented as coin losses per 1000 coins).

14.2.2 The Romano-British pottery

by Peter Didsbury (with contributions by Brenda Dickinson, Kay Hartley, and Lisa M. Wastling)

Introduction and methodology

A total of 233 sherds of Romano-British pottery, weighing 3,342g and having an average sherd weight of 14.3g, was recovered during the excavations. Of this material, 10 sherds weighing 254g (c.5–10% of the total, according to the measure of quantification chosen) was unstratified. The material has a maximum possible date range from the late 1st century to the later 4th or early 5th century AD, and appears to be entirely residual within its contexts (see further below, Discussion).

In view of the absolute residuality of the material, the emphases in studying this assemblage were placed on:

1. |

Establishing the nature and date-range of the pottery, which presumably derives from settlement activity in the near vicinity. |

2. |

Examining the chronological/spatial distribution of the pottery. |

3. |

Examining the material for cross-contextual “joins”, in the interest of elucidating earth-movement across and into the site. |

The potential of the material for these purposes was particularly constrained by small size and lack of diagnostic sherds (there were, for example, only 20 rim sherds).

Material was quantified by number and weight of sherds, and a computerised data-base constructed, relating the incidence of Romano-British material to the main categories of stratigraphic and other site information (available for scrutiny in the site archive). In the database, fabrics are referred to by the same alpha-numeric codes employed for the present author’s report on the pottery from Glebe Farm, Barton-upon-Humber (Didsbury, unpublished). In the catalogue below, a simplified series of fabric codes is employed, as follows:

GW greyware

CC colour-coated ware

WW white ware

The remainder of this report consists of a discursive treatment of the main findings, followed by full catalogues of the samian and mortaria, with a selective catalogue of the coarsewares. Taphonomic and distributional aspects of the assemblage are touched upon only briefly below, but have been used to inform discussions elsewhere in Volumes 1 and 4.

Discussion

The earliest Roman wares recovered consist of Hadrianic or Antonine samian, and a greyware jar which, on typological grounds, could belong to the final quarter of the 1st century AD (catalogue no. 3345). The latest are lid-seated jars of the kind found in profusion at The Park, Lincoln, and conventionally held to have been in use in Lincolnshire from the mid 4th century AD to the close of the Roman period (Darling 1977). As at Lincoln, these jars appear in two broad fabric types, one employing coarse, non-soluble grits, while the other is calcareously tempered. Sherds in these two fabric groups, referred to below for convenience as Group X and Group Y sherds respectively, formed 54% of the total pottery by sherd number, and 45.2 % by sherd weight. It is probable that all the Group X sherds derive from a single vessel, the rim of which is represented in context 4849, a Phase 3b pit-fill; while Group Y sherds represent a minimum number of two vessels, with rim sherds occurring in a variety of contexts through to Phase 5 – the earliest being in context 4673, a Phase 2 soakaway fill. Body sherds of these very distinctive vessels are indisputably present as early as Phases 1a and 1b, where they occur, for example, in pit-fills 4410 (Group X), and 4792 and 4630 (Group Y). It may be noted that the calcareous temper of the Group Y sherds is uniformly leached out, in contrast to that of the Middle Saxon calcareously tempered sherds from the site.

Two ceramic vessels of uncertain function (FIG. 14.10)

by Lisa M. Wastling

Two enigmatic and distinctive ceramic vessels were retrieved during the excavation (FIG. 14.10). Both are dish-like in form and have been manufactured from modified larger vessels, post-firing. Some small areas of the original surfaces of the vessels are apparent, though most of the original exteriors have been ground away to obtain the desired form. The interiors of the pots have also been ground to obtain their new shape. Presumably they were made for a specific function, though that has not yet been ascertained.

FIG. 14.8. Incidence of Romano-British pottery by main site periods

The fabrics of both would not be out of place within the Romano-British greyware tradition (Didsbury pers. com). They may have been manufactured from the bases of pedestal jars. Their deposition suggests however, that residual Roman ceramics were utilised to make pots for use during the mid to late Saxon phases of the site. They were recovered from a phase 2 soakaway in Building 6 and one of the Phase 6ii dumps.

The form of these modified vessels is such that there appear to be neither mid to late Saxon nor Roman period ceramic parallels.

A number of different functions may be postulated, such as unguent pots, ink or paint pots, salt containers for table-use, water or food dishes for caged birds, small lamps or vessels employed in metal-working.

The lack of burning points against use as part of high temperature processes or lamps, unless the objects are unused. Both dishes do however display a white, calcareous deposit, which may point to their having contained water or urine-based contents. One (RF 4483, no. 3355) was recovered from a feature referred to as a soakaway, so the residue may conversely be due to depositional factors.

Identification may be further aided by lipid analysis and/or x-ray fluorescence (XRF), as this was not undertaken during the post-excavation programme. It may however be difficult to distinguish between residues from the initial and secondary use of these vessels.

Catalogue (see FIGS 14.9–14.10)

Context and recorded find data, together with illustration number, are bracketed at the end of each entry.

THE SAMIAN

(Identifications by Brenda Dickinson)

A small amount of samian was recovered, amounting to nine sherds, weighing 149g. The material derives from Periods 3, 5 and 6, principally from occupation deposits and dark soils. The earliest is Hadrianic or Antonine and from Central Gaul, while the latest is East Gaulish ware of the late 2nd or early 3rd century. There are no signs that any of this material has been collected for secondary use in the post-Roman period, and the intrinsic interest of the assemblage is restricted to a stamped sherd of Macconius ii (see below, no. 3323).

3320 |

Body sherd. Central Gaulish. Hadrianic or Antonine. Context 1284, Phase 6iii (vessel 1284.2). |

3321 |

Body sherd. Bowl. Central Gaulish. Hadrianic or Antonine. |

3322 |

Body sherd. Central Gaulish. Hadrianic or Antonine. |

3323 |

Basal sherd. Form 31. East Gaulish. Fragmentary stamp of Macconius ii, die 1a. [MA\CCON]IVS FE. The “A” has no cross-bar, and the right-hand diagonal is formed of two parallel strokes. The die was used at Haute-Yutz on form 27, suggesting that this sherd is early to mid Antonine. The stamp shows background striations, indicating that the die was probably made from a re-used sherd. |

3324 |

Body sherd. Form 36? Central Gaulish. Mid to late Antonine. |

3325 |

Basal sherd. Mortarium, probably form 45. Central Gaulish, Lezoux. Very heavily worn inside, quite well worn under footring. c.AD 170–200. |

3326 |

Rim. Small form 37. East Gaulish, Rheinzabern. Ovolo with straight narrow core, double borders widely separated, and a tongue on the left swelling at the tip. Similar to Ricken and Fischer 1963, E.30. Late 2nd or early 3rd century. |

3327 |

Body. Form 79 or Ludowici Tg’. Central Gaulish. Mid to Late Antonine. |

3328 |

Flake. Central Gaulish. Hadrianic or Antonine. |

THE MORTARIUM

(Identification and catalogue entry by K. H. Hartley) A single mortarium sherd, weighing 34g, comes from context 4323, a Phase 3bi–4i dump.

3329 |

Vessel 8. Base sherd with an unusually well-formedfootring for a coarseware mortarium. Orange-brown fabric with white slip. Inclusions: frequent, random and ill-sorted quartz. Trituration grit: black iron slag. Mortaria in this fabric and with this type of trituration grit were made at potteries at Cantley, Catterick, Swanpool and probably elsewhere in the 3rd and 4th centuries. This is likely to be from Swanpool or Cantley. (FIG. 14.9) |

FIG. 14.9. Romano-British pottery. Scale 1:4

OTHER POTTERY

A selective catalogue of the coarsewares, comprising rims and other diagnostic sherds, is given below. Full details are contained in the site archive.

3330 |

Yellow-buff body sherd with self-slipped/polished exterior. Flagon? |

3331 |

GW. Flange fragment from straight-sided flanged bowl. |

3332 |

Vessel 5. GW. Jar with everted rim, rim diameter 140mm, and slight neck. 2nd or 3rd century? (FIG. 14.9) |

3333 |

GW. Small jar/beaker with everted rim, rim diameter 100–120mm. 2nd century? |

3334 |

GW. Red-brown surfaces and thick margins, grey core. Abundant unidentified stone temper and iron slag? in the 1–3mm range, extrusive through both surfaces. Hackly fracture. Thick-walled (12mm). Base of jar? |

3335 |

Vessel 4. GW. Jar. Cf. Coppack 1987, fig. 129.11, in a group from Goltho closing in the mid 2nd century; also Gillam 1957 type 138, 2nd to mid 3rd century. (FIG. 14.9) |

3336 |

CC. Worn beaker body sherd. Orange core, red interior, dark brown exterior. Probably Nene Valley. |

3337 |

GW. Light grey ware. Pedestal base with perimeter groove on the underside. Possibly from an Antonine or Severan carinated jar. |

3338 |

Vessel 6. Fabric RB2. Late redware. Fairly coarse, pinkish-buff fabric with polished red-brown surfaces. Straight-sided flanged bowl. Mid 3rd to 4th century. (FIG. 14.9) |

3339 |

Vessel 3. GW. Black surfaces, grey core, buff margins. Sandy fabric including greensand quartz, grog in the 2–4mm range, and voids of leached out calcareous temper. Jar/bowl with horizontally everted rim. Cf. Didsbury unpublished, no. 256, from Glebe Farm, Barton, probably 2nd century; Darling 1984, fig. 15, no. 66, from clearance levels beneath the Colonia rampart at Lincoln. There are two further examples of this rim form among the unstratified material (cat. no. 3349). (FIG. 14.9) |

3340 |

WW. Flagon? Fine, hard, white inclusion-free fabric with burnished cream exterior. Cf. cat. nos 3347 and 3348. |

CC. Red colour-coat, internally and externally, though worn on interior. White sandy fabric with occasional red inclusions and some voids. Footring base (c. 85mm diameter) of dish/bowl. Mid 3rd to 4th century. |

|

3342 |

CC. Worn beaker body sherd. Off-white core, yellow-buff interior, dark brown exterior. Not attributed to source. |

3343 |

WW? Two joining sherds of fine, pinkish-orange, flagon? fabric. |

3344 |

GW. Probably the “blue-burnished grey ware” of Dragonby, where it was common in the 2nd and early 3rd centuries. |

3345 |

Vessel 2. GW. Jar in hard, light grey ware. Typologically, with its globular body and short everted rim, it suggests a date in the late 1st or earlier 2nd century. Jars of similar shape, for which Swan suggests a date in the last third of the 1st century, were made with rusticated decoration at Dragonby Kiln 4 (May 1996, fig. 20.32, no. 1415; May, Gregory and Swan 1996, 574–82). (FIG. 14.9) |

3346 |

Vessel 7. CC. Sandy greyware-type fabric with crazed black exterior colour coat, and white over-slip en barbotine decoration of dots and curved lines. Jar. Probably Swanpool and 4th century. (FIG. 14.9) |

3347 |

WW. Flagon? Fine, hard, white inclusion-free fabric with burnished cream exterior. Possibly from a carinated shoulder? Cf. cat. nos 3340 and 3348. |

3348 |

WW. Flagon? Fine, hard, white inclusion-free fabric with burnished cream exterior. Cf. cat. nos. 3340 and 3347. |

3349 |

GW. Two rims as cat. no. 3339, one possibly from the same vessel. |

3350 |

GW. Off-white core with grey surfaces, a common fabric in the Humber Basin in the Antonine period. Out-turned rim from necked jar? Possibly cf. May 1996 fig. 20.16, no. 1082, from Dragonby, of later 2nd-century date. Unstratified. |

3351 |

Vessel 9. Fabric X. Quartz-tempered jar with single lid-seating. Later 4th century. (FIG. 14.9) |

3352 |

Vessel 10. Fabric Y. Vesicular jar with single lid-seating. |

3353 |

Vessel 11. Fabric Y. Vesicular jar with single lid-seating. |

FIG. 14.10. Two ceramic vessels of uncertain function. Scale 1:1.

Two ceramic vessels of uncertain function

(catalogue entries by Lisa M. Wastling)

3354 |

Miniature dish, with straight sides and narrow pointed rim. Ground or filed to form from the base of a vessel of Romano-British greyware fabric. Has a white deposit on the interior base and lower wall which reacts with dilute hydrochloric acid. (FIG. 14.10) |

3355 |

Miniature dish, with straight sides and rounded rim. Ground or filed to form from the base of a vessel of Romano-British greyware fabric. Has a cream coloured deposit on the exterior base and vessel wall which reacts with a dilute hydrochloric acid. (FIG. 14.10) |

14.2.3 The Romano-British ceramic building material

by Lisa M. Wastling

370 fragments of Roman ceramic building material weighing 39.905kg were recovered by excavation. This material was divided into two fabric groups: A and B.

Group A consisted of the tiles with fine homogeneous fabrics, and group B contained material of a much coarser fabric with the addition of grog, and sparse organic temper. Fabric B appeared to have been fired to a higher temperature than those of group A (some of which were powdery and easily abraded). Much of the material had, however, been affected by secondary burning.

The group B material is very consistent and appears to be of a single fabric; however, group A consists of more than one fine fabric type.

Due to the fragmentary nature of the material, 9% by weight was unidentifiable, though of the same fabrics as the identified material. That this amount represents 36% by number is indicative of the small fragment size. All further percentages in this report will therefore represent percentage by weight.

All of this material was recovered from contexts of Anglo-Saxon or later date.

Brick

The majority of identified fragments were of brick, representing 50% of the assemblage. These vary in thickness from 26 to 49mm. The majority were of fabric A, though 17 fragments were of fabric B. Eighteen fragments bore deep finger-scoring on the upper surface, possibly to act as keying for mortar. Eight were in the form of a cross or saltire, and possibly all were of saltire form – as in only one instance was the corner present to show that the cross was of this orientation. One example had a curved finger-mark.

A single brick was rain-pitted on the upper surface, indicating that prior to firing it had been laid out to dry in the open, or at the edge of an open-sided structure.

A single example of a possible voussoir brick was found, with a thickness over the length of the fragment varying from 25 to 31mm.

One brick fragment was identifiable by type: a bessalis in fabric B brick from context 956. This has a complete width measurement, of 198mm with a thickness of 43mm. The measurements of Roman brick manufactured in Britain are based on the Roman foot, consisting of 12 Roman inches and corresponding to 296mm. The bessalis was based on a measurement of eight inches, corresponding to 197mm; their main function was as pillars for hypocaust heating systems.

This example also has an interesting mark on its upper surface. A linear object, such as a rod or roundwood stick of 17mm in width, with a probable circular cross-section and extending along the length of the tile, has fallen onto the tile to leave an impression; this had occurred when the tile was laid out to dry, pre-firing. The surface of this object had been covered with sand, which had remained on the surface of the tile after removal; when the object was retrieved, the individual must have leant on the tile, leaving a deep impression of the heel of their right hand in the corner of the tile.

Their left hand has also left the impression of the nails of the middle three fingers, as they have picked the object off the tile. This in turn implies that the tile was located in the middle of an area of tiles, which had to be leant over to retrieve the object. The dimensions of the impression appear slight, possibly suggesting an adult with slim hands, or a child.

Tegulae

Tegulae represented 31% of the material by weight. All were of fabric group A. The thickness of tegulae was measured only on fragments which had surviving evidence of flanges, and was taken as close to the centre of the tile as possible; thicknesses varied from 17 to 27mm. Eleven complete flange profiles were noted, all of which were different. None bore signatures or any evidence of stamps.

Five fragments bore an upper cutaway, and a single fragment from hearth 466 had a lower cutaway; this has a similar form to the type B cutaway at Castleford (Betts 1998, 227, fig. 97), though with a smaller chamfer at the base.

Two fragments had a vitrified glassy deposit the same as that on the hearth daub from context 466 (see Wastling, Ch. 4.2, above). One fragment was from hearth 466, and the other was from context 12218.

Imbrices

Imbrices represented just 3% of the material by weight. All were of fabric group A. The fragment size of this group was very small; they had possibly been broken into smaller fragments in order to be incorporated in hearths, which necessitated the use of flat material.

Flue tile

Flue tile represented 5% of the material by weight. The majority was of fabric group A, with just two fragments of fabric B. Fourteen of the 24 fragments have combed keying, using combs of 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8 teeth. Five tiles showed evidence of corner angles, indicating that they were of box or half-box form. Two had tapering circular vents – one on an uncombed surface, with a diameter of 15–25mm, and the other on a combed surface of 19–28mm diameter (from context 3349). This latter tile has primary sooting internally and rising up from the vent, indicating use within a building with a working hypocaust heating system, such as a bathhouse, or high-status building; the direction of the sooting also gives evidence of fragment orientation. Tapered circular vents were found on flue tiles from Binchester Roman fort, Co. Durham (Brodribb 1987, 76, fig. 33, f).

Possible louver fragments

Four fragments of tile with a curved and rounded surface were found. These appeared to have been fired to a lower temperature than the other material, appearing more like terracotta in texture. All were bright orange in colour. These fragments were perhaps part of a louver or chimney pot.

Roman ceramic building material was recovered from 169 contexts. All had either been reused from the 7th century onwards, or was residual. The material which was found in situ was used to make up hearth and oven bases, and 52% of the re-deposited brick and tile had either adhering hearth daub (daub fabric A), signs of burning, or both.

Eight fragments still bear evidence of primary mortar, and two fragments (a brick and a flue tile) have small amounts of white plaster adhering. The mortar is pinkish in colour, due to crushed tile inclusions.

The mean fragment size of the brick and tile assemblage is small at 108g. It is possible that tiles may have been reused several times, since the buildings of which they were originally a part had passed out of use, in addition to residual material being continually reworked.

Webster (1979, 287) states that the tile industry ceased to flourish in the late 4th century, after which most disused buildings were subjected to a process of tile recovery.

Mean fragment sizes between tile used for hearth construction (bearing hearth daub and/or burning) and the rest of the assemblage, differ by only 10g: this indicates that the material selected for hearth and oven floors does not differ greatly from other Roman ceramic building materials from the site. It may also indicate that the material used to construct hearths was not brought to the site specifically for that purpose, but was already a residual element on the site, and hence has the same assemblage make-up. If the brick and tile had been brought to the site, specifically to construct hearth and oven bases, then larger fragment sizes would have been expected from the hearth material, with residual material showing greater fragmentation: this was found not to be the case.

The origin of the ceramic building materials may have lain within the immediate locality of the site, as there are two distinct residual Roman elements in the pottery assemblage. One is of early date, consisting mainly of samian ware, and found in the later phases of the occupation sequence (Loveluck, Volume 4, Ch. 3), and the other of 4th-century material, in the earlier phases (see section 14.2.2, above).

14.2.4 A copper alloy penannular brooch

by Nicola Rogers

This copper alloy brooch (no. 3356; RF 14124), with coiled terminals and a long pin with a decorative collar, was unstratified. This form falls into Fowler’s (Fowler 1960) Class C, which has been refined by White into Classes Ca and Cb, differentiated by the hoop section (White 1988, 9); the circular section of no. 3356 (RF 14124) places it in White’s Ca class.

Penannular brooches have been recovered in the British Isles from Iron Age through to Anglo-Saxon contexts (White 1988, 6), and Class Ca forms are known from the early Roman period (ibid., 9). In his survey of Roman objects from Anglo-Saxon graves, White notes examples of both iron and of copper alloy recovered from many Saxon cemeteries, including Castle Bytham, Lincs. (ibid., 10, fig. 2, no. 6), and Holywell Row, Suffolk (ibid., 11, fig. 4, no. 3). Two Class Ca brooches were also found amongst material containing other Saxon brooches from South Ferriby, Lincs. (Sheppard 1907, 261, pl. XXVII, nos 3, 6). White notes that most Anglo-Saxon graves containing penannular brooches appear to date from the later 5th–mid 6th centuries, although a few also occur in 7th-century graves (White 1988, 23). He stresses that the problem of residuality makes it very difficult to determine whether a brooch is Roman and reused, or post-Roman in date (ibid., 23–4); whatever the date of manufacture of no. 3356 (RF 14124), it seems likely that its use at Flixborough, if used at the site at all, occurred in the earliest phases of Saxon occupation. The fact that the object is unstratified, however, suggests that it could represent a Roman find with no connection to later occupation on the site.

Catalogue (not illustrated)

3356 |

Copper alloy. Complete, Fowler’s Class C, bow of circular section, with coiled terminals; long pin of circular section with decorative collar. Bow diam. 23mm; bow section Diam. 1.7mm. Pin L. 38.3mm; section Diam. 1.6mm |

14.2.5 A Romano-British sculpted stone fragment

by Lisa M. Wastling

A fragment of worn and abraded sculpted stone (no. 3357; RF 14055) was retrieved from Period 6 dump 1283. The form of the decoration bears close affinities to the motifs used on Romano-British altars, tombstones and dedication stones, such as the crescent, lunula or pelta (Collingwood and Wright 1965, passim). A portable altar fragment recovered from the excavations at Dragonby bears some similarities to this piece (Wilson 1996, fig. 15.3).

This stone may have been plundered from a nearby Roman site for use as building material. The location of the Roman settlement at Dragonby is only some 2.5 miles (4km) from Flixborough. It has also been suggested that the stone lamps may have been made from re-used Roman building stone (see Gaunt, Ch. 5.9, above).

Catalogue (FIG. 14.11)

Lithological identification by Geoff Gaunt

3357 |

Sculptural fragment. |

FIG. 14.12. Stone pestle. Scale 1:2.

14.2.6 A stone pestle

by Lisa M. Wastling

A single example of a chalk pestle (no. 3358; RF 5342) was recovered from a Phase 6ii dump (3891). Chalk, being a soft stone, would probably have been suitable only for the grinding or pounding of material such as foodstuffs. The majority of pestles for use with relatively soft substances may have been of wood, such as those in more recent ethnographic contexts, in Africa and the West Indies for example. This would explain their lack of survival. No fragments of mortars were found during the excavations. There is the possibility that this object is residual, and relating to Romano-British or earlier activity. A sling-shot of probable Iron Age date was recovered from the same deposit (see above).

Catalogue (FIG. 14.12)

(Lithological identification by Geoff Gaunt)

3358 |

Pestle |

14.2.7 The jet pin

by Lisa M. Wastling

A jet pin (no. 3359), consisting of two adjoining shank fragments, was recovered from samples of two different contexts. These were the fill of post-hole 8733, which cuts path 8092 in Phase 5a, and an occupation deposit/yard 6464 in Phase 3bii. These two deposits, though in differing phases are laterally approximately five metres apart.

It is likely to be of 3rd century or later date, as the use of jet in the Roman period was uncommon before this time (Allason-Jones 1996, 8). The source of the material is likely to have been the area around Whitby, in North Yorkshire.

Catalogue (not illustrated)

3359 |

Pin. Incomplete section of hipped shank. In two fragments. |

14.3 High Medieval and later remains

There is clear structural evidence for a limited amount of peripheral settlement activity on this site during Period 7 (12th–14th centuries: see Loveluck and Atkinson, Volume 1, Ch. 7) and this may relate to a re-planning of the settlement in the Anglo-Norman period (Loveluck, Volume 4). In addition to finds contained in these stratified contexts, there is also a small amount of material deposited on the site throughout the medieval and post-medieval periods – presumably reflecting both agricultural uses of this hill-slope, and casual losses from visitors. This section of the report discusses all material which is clearly later than the Norman Conquest. In addition, material of uncertain date has been included here – although it is recognised that some of this may well be residual from earlier occupation.

14.3.1 Medieval and later pottery

by Peter Didsbury

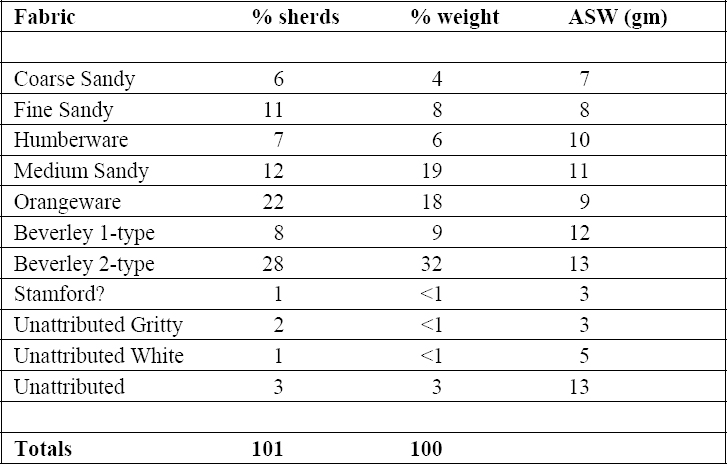

A total of 169 sherds of medieval and later pottery, weighing 1635 gm and having an average sherd weight (hereafter ASW) of 9.7 gm, was recovered from the excavations. Of this material, 43 sherds (25.4%) were unstratified. The total date-range was from the 12th to 20th centuries.

The medieval pottery amounted to 111 sherds, weighing 1245 gm. The overall ASW of this assemblage was 11.2gm, individual fabrics exhibiting values in the 3–15gm range (FIG. 14.13). The date-range was from the 12th to 14th, or possibly the 15th, century.

At the time the Flixborough medieval pottery was analysed, there was no established fabric type-series for North Lincolnshire, and a simple terminology, capable of being applied to assemblages of small, worn and redeposited material, was therefore adopted. This was largely based on the regional tempering traditions of the Humber Basin noted by Hayfield (1985), and by comparison with named fabrics known to have been used on both banks of the Humber in the medieval period. A detailed medieval fabric series for North Lincolnshire sites has since been constructed by Jane Young, Alan Vince and the present author, while working on the St Peter’s Church, Barton-upon-Humber project, but it has not been practicable to revise the Flixborough data to conform with this.

The following fabric types were recognised:

– |

Beverley 1- and 2-type ware (Watkins 1991; Didsbury and Watkins 1992): applied to material sharing the characteristics of 12th- to early 14th-century Beverley wares, but not necessarily products of that industry. |

– |

Coarse Sandy ware: regional tempering tradition. Some sherds may be the specific fabric of the same name common on sites in Hull and East Yorkshire in the 14th century (Watkins 1987). |

– |

Fine and Medium Sandy ware: regional tempering traditions. |

– |

Humberware: the dominant ware in the Humber Basin in the 14th and 15th centuries. |

– |

Orangeware: the regional tempering tradition which includes Beverley ware. |

– |

Stamford ware: as described in the literature (Kilmurry 1980). |

– |

Unattributed Gritty ware, Unattributed White ware: self-explanatory generic terms. |

The earliest material in the medieval assemblage is probably two sherds of splash-glazed Beverley 1-type, which should pre-date the mid 12th century. Splashed fragments may also be present among the Medium Sandy ware. Glazing on the rest of the Beverley 1 sherds, as with all the other fineware fabrics, is of the suspension type. Interestingly, almost the entire assemblage seems to consist of jug sherds, though the Gritty and White ware sherds are probably from coarseware vessels, and there is a pipkin rim fragment among the Beverley 2-type ware. It will be seen that Beverley 2-type and its Orangeware equivalents account for 50% of the entire medieval assemblage, strongly suggesting that the period when the greatest amount of medieval material entered the taphonomic record was the 13th and first half of the 14th century. There is a dearth of chronologically diagnostic material among the sand-tempered fabrics, but there is no reason to suppose that they are not broadly contemporary with the Orangewares. The small amount of Humberware may well have been contemporary with the latest Orangeware fabrics, rather than extending the sequence into the 15th century.

The great majority of the medieval material occurs in the dark soils and occupation deposits of Periods 6 and 7, though there is occasional intrusive material present as early as Phase 2–3a. These occurrences are discussed individually in the site narrative (Volume 1).

FIG. 14.13. Fabric profile of the medieval pottery assemblage.

As far as post-medieval and modern pottery is concerned, it is sufficient to note that 58 sherds were present, weighing 390 gm – the earliest is a sherd of 15th- or 16th-century Coal Measures fabric from dump 3275 (Phase 5a–6i) – and that the other fabrics are the common regionally and nationally available products of the period, viz. Blackware, Staffordshire Slipware, Glazed Red Earthenware, and Unglazed Red Earthenware (flowerpots etc.). Modern material includes Pearlware, Creamware, Porcelain, Industrial Whitewares and Brown Stonewares.

14.3.2 Medieval and later non-ferrous metal objects

by Nicola Rogers

Buckles

Two unstratified buckles (nos 3360–1; RFs 837 and 840) are of post-medieval forms.

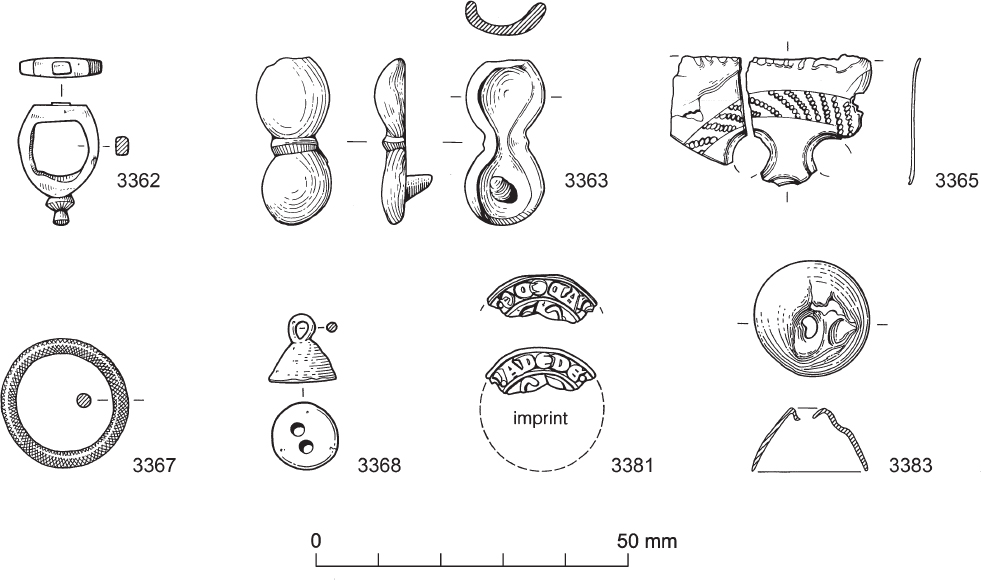

Pendant loop (FIG. 14.14)

Found unstratified, no. 3362 (RF 10950; FIG. 14.14) is a medieval pendant loop, which would have been attached to a belt via a bar mount, and possibly used to hang a purse or knife (Egan and Pritchard 1991, 219, fig. 138).

Triple-lobed mounts (FIG. 14.14)

Two unstratified mounts (nos 3363–4; RFs 11934, 13185) were both originally triple-lobed, with rivets for attachment. This form is medieval, with similar examples from York coming from early-mid 15th century or later deposits (Ottaway and Rogers 2002, 2905, e.g. nos 13369 and 14418, fig. 1479); another found in Norwich came from a 15th–17th century context (Margeson 1993, 40, no. 276).

Miscellaneous mount (FIG. 14.14)

The fragmentary no. 3365 (RF 12749; FIG. 14.14), possibly a box mount, is decorated with perforated stamped rings and rocked tracery; although rocked tracery ornament has been found on a few objects dating from the late 9th century (Rogers 1993a, 1350), it is much more commonly found on medieval objects. The multi-foil surround on no. 3366 (RF 50004) is also indicative of the medieval period, when petalled mounts were commonly used to decorate books and belts (Ottaway and Rogers 2002, 2906–7).

Annular brooch (FIG. 14.14; PL. 14.1)

A small unstratified brooch is made of gold. No. 3367 (RF 12237; FIG. 14.14; PL. 14.1) is formed from double-strand wire wound around a core which is also probably gold (see analyses). Although lacking a pin, the ring appears too small to be a finger-ring, and its closest parallel would appear to be another gold brooch, complete with pin, which was found in a mid–late 13th-century deposit at the Vicars’ Choral College at The Bedern, York (Ottaway and Rogers 2002, 2911, no. 14507, fig. 1486). Two similar brooches, one of silver, the other of copper alloy, have also been found in London in late 12th-century contexts (Egan and Pritchard 1991, 256, nos 1339–40).

FIG. 14.14. Medieval and later non-ferrous objects. Scale 1:1.

Buttons (FIG. 14.14)

Apart from one possibly medieval button (no. 3368; RF 12568; FIG. 14.14), all those recovered appear to be post-medieval or modern, and with one exception derive from topsoil or are unstratified; the exception is no. 3369 (RF 3824), which must have been intrusive in its Phase 6iii dark soil deposit.

No. 3368 (RF 12568; FIG. 14.14) is a composite button, made up of a flat upper face and plano-convex lower face with loop through – the two halves having been soldered together. This type of button has been recovered from a number of medieval sites across England; these sites include York, where they came from mid 13th–early 14th century deposits, at which time they may have had an ornamental rather than functional role (Ottaway and Rogers 2002, 2918–19, nos 14452–3, fig. 1491).

Lace tag

No. 3380 (RF 7) is a lace tag, decorated with cross-hatching and retaining traces of the leather lace inside. It was found in an unstratified context, but is likely to be medieval – perhaps 15th century or later; similar examples found in York have come from this period (Ottaway and Rogers 2002, 2920–21).

Medieval seal matrices (FIG. 14.14)

Both seal matrices recovered at Flixborough (nos 3381–2; RFs 11924 and 14245) were found in unstratified contexts. Only part of one edge of the discoidal no. 3381 (RF 11924; FIG. 14.14) survives; the lettering appears to be: ADEDE, but too little remains to enable identification of the full inscription. A fragment of a tail below suggests a beast – perhaps a lion – motif. Although the fragmentary nature of no. 3381 (RF 11924) makes a full identification impossible, it is possible to suggest a date of the 13th century for this seal, when this form was in use (Alexander and Binski 1987, 396).

No. 3382 (RF 14245) has a faceted stem of hexagonal section, the matrix being cut into the discoidal lower end; the upper terminal is pierced forming a looped handle, used for attachment to the person. The motif depicts a bird with a feather over it, and the legend appears untranslatable, although the letters appear to include: I C S R I C. It has been noted that a considerable proportion of seals, particularly from the cheaper end of the market, had legends which are garbled or unintelligible (Alexander and Binski 1987, 275, no. 196 vii), and no. 3382 (RF 14245) appears to fall into this category. Its form indicates a probable date of the late 13th–mid-15th century (Spencer 1984, 377).

Bell (FIG. 14.14)

No. 3383 (RF 103; FIG. 14.14) is a rumbler bell fragment recovered from topsoil, but which may be medieval. Medieval rumbler bells are made from two hemispheres of sheet metal, the edges folded over and sealing in an iron pea; possible uses include on harness, as jesses on hawks, collars on hounds, and as dress decoration (Biddle and Hinton 1990, 725–6). No. 3383 (RF 103) may date from the 13th–16th century, from which period similar bells are known (see for example Harvey 1975, 254–5, nos 1711, 1726; Biddle and Hinton 1990, 725–6; Ottaway and Rogers 2002, 2947).

Miscellaneous object

An unstratified copper alloy object (no. 3384; RF 97) appears to be a mount; quadrant-shaped at one end, with incised decoration, the rest of the object is stepped forward and appears to show a lion’s head at one side. The mount has two perforations and three rivets on the back. It has been mercury-gilded. Perhaps a bridle mount, no. 3384 (RF 97) is likely to be post-medieval in date.

Catalogue of non-ferrous objects (FIG. 14.14)

BUCKLES

3360 |

Copper alloy. Frame fragment, of trapezoidal section, one corner and parts of two sides survive with scalloped edge. There is a square projection at the corner, on each side of which there are oval facets on upper face with notched edges and inset leaf-shaped motifs. |

3361 |

Copper alloy. Shoe buckle, square, double-looped. |

PENDANT LOOP (FIG. 14.14)

3362 |

Copper alloy. D-shaped, with collared knop. |

TRIPLE-LOBED MOUNTS (FIG. 14.14)

3363 |

Copper alloy. Fragmentary, double-lobed, further lobe broken off, collar between lobes which are domed, one lobe with rivet shank. |

3364 |

Copper alloy. Fragmentary, other lobes broken off, domed, remains of shank underside. |

MISCELLANEOUS MOUNTS (FIG. 14.14)

3365 |

Fragments (2), adjoining, of sheet, irregularly shaped, two edges cut, others broken, torn rivet-hole at each end, decorated with perforated stamped rings and rocked tracery. |

3366 |

Of sheet, sub-circular, with central hollow dome, surrounded by punched multifoil. |

BROOCH (FIG. 14.14; PL. 14.1)

3367 |

Gold. Annular, made of multi-strand, single-twist wire; pin lost. |

BUTTONS (FIG. 14.14)

3368 |

Copper alloy. Composite, plano-convex with loop, flat face with two stamped dots. |

3369 |

Copper alloy. Circular, shallowly domed. |

3370 |

Copper alloy. Modern. |

3371 |

Copper alloy. Modern. |

3372 |

Copper alloy. Modern. |

3373 |

Copper alloy. Discoidal. |

3374 |

Copper alloy. Discoidal. |

3375 |

Copper alloy. Discoidal with loop. |

3376 |

Copper alloy. Discoidal with loop. |

3377 |

Copper alloy. Discoidal with loop. |

3378 |

Copper alloy. Discoidal. |

3379 |

Copper alloy. Discoidal, central slot, decoration. |

LACE TAG

3380 |

Copper alloy. With inward folding seam, decorated with cross-hatching containing dots in relief, contains traces of leather lace inside. |

SEAL MATRICES (FIG. 14.14)

3381 |

Copper alloy. Originally discoidal, only part of one edge survives, with legend ? ” ADEDE”, fragment of beast’s tail below. L.19.8 W.7.3. (FIG. 14.14) |

3382 |

Copper alloy. Faceted stem of hexagonal section, upper terminal pierced forming a looped handle; matrix cut into discoidal lower end, motif depicting a bird with a feather over it, legend includes letters: I C S R I C. |

BELL (FIG. 14.14)

3383 |

Copper alloy. Rumbler bell fragment, upper hemisphere with irregular hole for suspension loop now missing. |

MISCELLANEOUS OBJECT

3384 |

Copper alloy. Quadrant-shaped plate, with incised foliate decoration, centrally perforated with second perforation at one edge, three rivets on reverse with projecting and stepped forward plate with ?lion face at upper end, mercury-gilded. |

14.3.3 Medieval and later objects of iron

by Patrick Ottaway

Dress and personal items

BUCKLES

Buckle frame no, 3385 (RF 8286) is unusual in being pierced, presumably to hold the head of the tongue; it is unstratified and may be medieval or later. There is a single example of a rectangular buckle frame (no. 3386; RF 2750) which is plated and has a tubular runner on the side on which the tongue tip rested. This object is probably medieval. There is also a single example of a circular frame (no. 3387; RF 9010) to which some leather adheres; this is either a belt or shoe buckle.

Nos 3388–9 (RFs 9144 and 13335; both unstratified) are the rotating arms from buckles of medieval date.

BELT HASP (FIG. 14.15)

No. 3390 (RF 10990; FIG. 14.15) is a belt hasp, a buckle-like object used to join two straps, but without the tongue of a buckle. No. 3390 (RF 10990) consists of a D-shaped frame with an elongated plate looped over one side and riveted. The object is tin-plated. No belt hasps are known from Anglo-Saxon contexts, and the type is probably late 11th–12th century to judge by examples from Winchester (Hinton 1990d, fig. 143, 1350) and 16–22 Coppergate, York (Ottaway 2002, 2889–90 and 3063, cat. no. 12719, sf5228).

Horse equipment

BRIDLE FITTING

No. 3392 (RF 12431) is a tin-plated bridle fitting consisting of two components linked together. One exists as a triangular plate pierced at the head, which at the base develops into a round, domed terminal; from the flat side a rivet projects. The other component is an oval disc which has a small loop at the head by which it was linked to the first. The object is unstratified and probably medieval.

HORSESHOES AND HORSESHOE NAILS

There are seven horseshoes, all of which are unstratified. Nos 3394 and 3399 (RFs 8321 and 12951) have the wavy outer edge characteristic of the 11th–early 13th centuries, the remainder are probably late medieval. Thirty horseshoe nails of various forms were found, of which nine were stratified. RFs 6540 and 8265, from Period 6 and unstratified contexts respectively, may be Anglo-Saxon, as the horseshoe was probably introduced in the late 10th century (Ottaway 1992, 707–9). The D-shaped heads of RFs 6540 and 8265 are those of the ‘fiddle key’ type of nail used at this time. RFs 2398, 2403, 7940, 8936 and 8955 have or had D-shaped heads, but come from 9th-century and earlier contexts and are likely to be intrusive, as are RFs 1194 and 7305 from Period 6 contexts which have the late medieval form of head with short ‘wings’ at the base.

Locks and keys

SHACKLE (FIG. 14.15)

No. 3404 (RF 4086; FIG. 14.15) is the shackle of a padlock which was hinged at one end of the case, and at the other fitted into a slot before the bolt was inserted. This may be an intrusive medieval object, as no examples of padlocks with this feature are known from the Anglo-Saxon period.

TWIST KEY

No. 3405 (RF 12418) is a small key with a solid stem, which projects beyond a bit, existing as two short projections. It is unstratified, but probably medieval.

Structural ironwork and fittings

WALL HOOKS

23 wall hooks were found on the site; 12 of these are unstratified or from topsoil, and five others may be medieval. As the remaining six were from Anglo-Saxon contexts, the main discussion of these objects is in Chapter 5, above. Hooks of the principal form have a long history. which, as no. 3408 (RF 25; made of cast iron) clearly shows, continues into modern times;

SWIVEL HOOK

No. 3409 (RF 13152) is a small, plated swivel hook which is unstratified, but probably medieval. Whilst the form is known from Romano-British contexts (cf. Manning 1985), it is rarely found before the medieval period (cf. an example from an early 12th-century deposit at Goltho (I. H. Goodall 1987).

CARBINE HOOKS

Nos 3410–11 (RFs 8336 and 8588) are modern carbine hooks found unstratified.

WASHERS

There are four small washers (nos 3412–15; RFs 9187, 9697, 12943 and 13119) which are 27–44mm in diameter. Their function is unknown.

FIG. 14.15. Medieval iron belt hasp and lock shackle. Scale 1:2.

Cutlery

SCALE-TANG KNIVES