PUTTING UP: CANNING, PICKLING, FERMENTING, & MORE

THE ONLY WAY PEOPLE COULD ESCAPE FROM A DAILY PREOCCUPATION WITH FEEDING THEMSELVES WAS BY ACQUIRING THE ABILITY TO PRESERVE FOOD FOR THE FUTURE.

As has been pointed out many times already, growing, scavenging, and securing food during the zombie apocalypse will be a monstrously hard task. And in a world without refrigeration, all survivors should have a few basic food preservation skills in their back pockets. If at any time during an uprising of reanimated corpses whose sole and unrelenting purpose is to eat your innards you find yourself with an abundance of fresh fruits and vegetables that are at risk of spoiling, you are a very lucky survivor indeed—and you need to be ready to take advantage.

Food preservation is about learning to make the most of surpluses in any and all forms, from the turnips growing on your rooftop farm to the abundance of wild berries you might stumble across in a forest. Outlined in this section are low-tech, apocalypse-friendly techniques for canning, pickling, fermenting, curing, and smoking (but you got that from the title, didn’t you?).

Canning

Canning as a method of food preservation dates back to Napoleon’s famous idea that “an army marches on its stomach.” In 1795 he put forth the challenge of finding a preservation technique that would prevent rations from spoiling out in the field and offered a 12,000-franc reward. Fifteen years later, French chef Nicolas Appert gave the world its first iteration of hot-water canning.

Hot-water canning, or just simply “canning,” is a generally safe and simple process, allowing you to preserve excess bounty from your Window Farming (page 148) or Rooftop Farming (page 153) efforts. The process involves putting the foods you want to preserve into sterilized and sealable containers, then immersing the vessels in a hot-water bath to seal and “process,” or heat sterilize, the contents for long-term storage.

While the mason jars used for canning have become ubiquitous in the pre-zpoc world and should be fairly easy to scavenge—used as everything from kitschy drinking glasses to candle holders—the self-sealing tops crucial to protecting your food from spoiling will probably not be as easily found. You might be able to scavenge some from a nearby store or even residential houses; however, I highly recommend stocking up ahead of time.

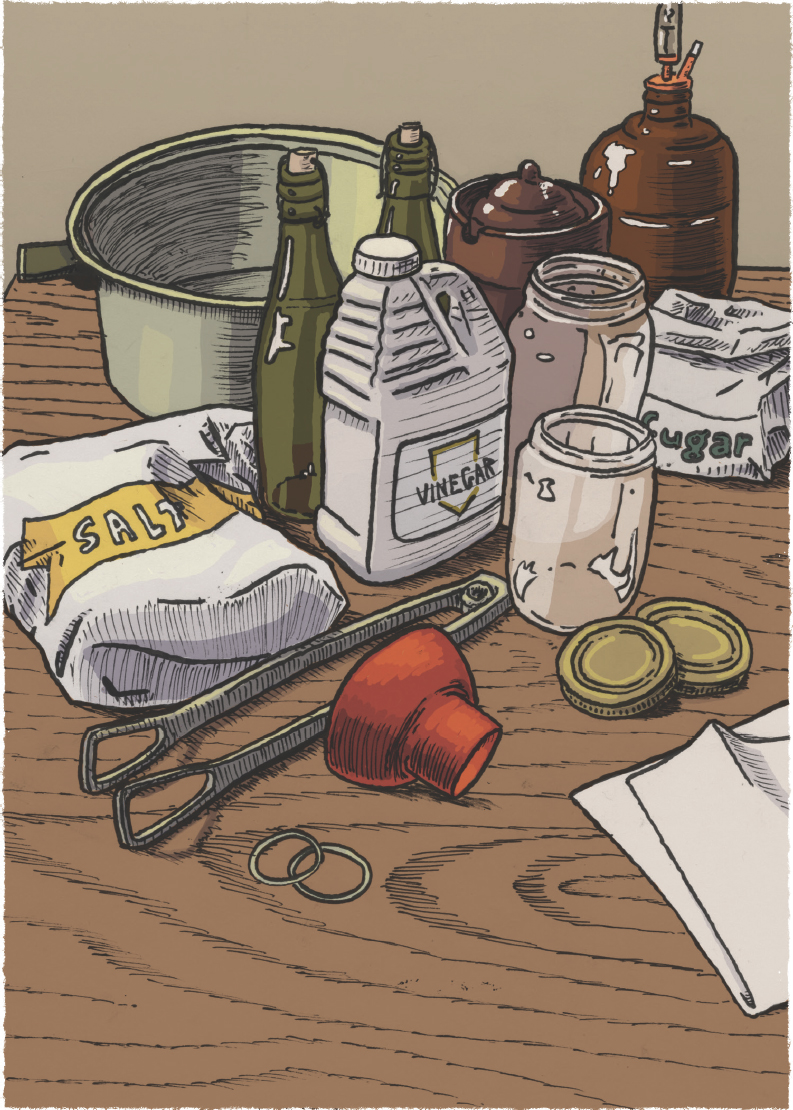

TOOLS

LARGE CANNING POT (AT LEAST 18-21 QUARTS)

Jars need to be fully immersed during processing, making a large pot essential for canning. You can also use this pot to sterilize your jars and tools before getting started.

GLASS MASON JARSD & SELF-SEALING LIDS

As long as they are the equivalent size, self-sealing metal lids and threaded metal screw tops should fit on any standard home-canning jar regardless of brand or manufacturer. If you are stocking up ahead of time, get a variety of lid sizes.

JAR LIFTER

Although tongs could be used instead, the specialized jar lifter’s clever design and rubberized grip are much safer for lifting hot cans out of the water.

WIDE-MOUTHED FUNNEL

While this tool isn’t an absolute necessity, it will make pouring liquid foods, like jams or sauces, into jars much cleaner and easier.

HOW TO CAN

Sterilize equipment by submerging in boiling water for 10 minutes: jars, metal screw tops, funnels, ladles, and any other utensils that will come into direct contact with the food you’re preserving. Bring the temperature of the water down to a gentle simmer and add the lids. Though the lids must be warmed before using, boiling them before processing the filled jars can damage the adhesive that creates an airtight seal. Instead, wash them with soap before adding to the pot if possible. Keep the pot and all contents warm over a low flame while you prepare the recipe.

Sterilize equipment by submerging in boiling water for 10 minutes: jars, metal screw tops, funnels, ladles, and any other utensils that will come into direct contact with the food you’re preserving. Bring the temperature of the water down to a gentle simmer and add the lids. Though the lids must be warmed before using, boiling them before processing the filled jars can damage the adhesive that creates an airtight seal. Instead, wash them with soap before adding to the pot if possible. Keep the pot and all contents warm over a low flame while you prepare the recipe.

When ready to use, remove the jars, lids, and screw tops from the simmering pot with tongs, draining and shaking off as much residual water as possible. Lay them out on a clean surface or towel. Fill the warm jars with your recipe, leaving the “headspace” (gap at the top) specified in the recipe. In the absence of a recipe, often it is ¼–½ inch of space. When you are pickling, make sure the food is completely covered by the pickling liquid. Give the contents a stir to release any lingering air bubbles. Wipe the rim of each jar with a clean cloth then, using tongs, put on the flat sealing lid and thread on the metal band.

When ready to use, remove the jars, lids, and screw tops from the simmering pot with tongs, draining and shaking off as much residual water as possible. Lay them out on a clean surface or towel. Fill the warm jars with your recipe, leaving the “headspace” (gap at the top) specified in the recipe. In the absence of a recipe, often it is ¼–½ inch of space. When you are pickling, make sure the food is completely covered by the pickling liquid. Give the contents a stir to release any lingering air bubbles. Wipe the rim of each jar with a clean cloth then, using tongs, put on the flat sealing lid and thread on the metal band.

Put your jars into the canning pot, making sure they are covered by at least an inch of water, and bring the water to a boil. Allow the jars to boil for the length of time specified in the canning recipe, typically 10–15 minutes, but don’t start counting time until the water comes to a rolling boil. Remove your pot from the heat and let sit for 5 minutes.

Put your jars into the canning pot, making sure they are covered by at least an inch of water, and bring the water to a boil. Allow the jars to boil for the length of time specified in the canning recipe, typically 10–15 minutes, but don’t start counting time until the water comes to a rolling boil. Remove your pot from the heat and let sit for 5 minutes.

Carefully remove jars from the pot and allow them to cool undisturbed on a rack or towel for 24 hours. You should start to hear the jars popping; the sound means a jar has been properly sealed. After 24 hours, check each jar by removing the metal screw top and inspecting the flat lid—it should be taut and adhere tightly to the jar.

Carefully remove jars from the pot and allow them to cool undisturbed on a rack or towel for 24 hours. You should start to hear the jars popping; the sound means a jar has been properly sealed. After 24 hours, check each jar by removing the metal screw top and inspecting the flat lid—it should be taut and adhere tightly to the jar.

Replace the screw tops and store your jars in a cool, dark place, or consider building a Root Cellar (page 190). Most canned foods should last for at least a year.

Replace the screw tops and store your jars in a cool, dark place, or consider building a Root Cellar (page 190). Most canned foods should last for at least a year.

RECOMMENDED READING: For more on home canning and preserving, check out the lovely and thorough guide Saving the Season: A Cook’s Guide to Home Canning, Pickling, & Preserving by Kevin West.

WHAT (NOT) TO CAN

In order for foods to be stored long-term after canning, they must contain a certain level of acidity. Generally foods with a pH of 4.6 and higher do not contain enough acid for canning on their own; however, mixing with other higher acid foods or vinegar can make them safe for canning.

A few common foods that cannot be canned safely on their own:

Asparagus

Asparagus

Beans

Beans

Beets

Beets

Cabbage

Cabbage

Carrots

Carrots

Corn

Corn

Lima beans

Lima beans

Mushrooms

Mushrooms

Peas

Peas

Potatoes

Potatoes

Pumpkin

Pumpkin

Spinach

Spinach

Squash

Squash

Turnips

Turnips

Turning Fruit into Jam

Depending on the climate where you live or have fled to, you may have a variety of fresh fruits to choose from come growing season—and more of them than you can possibly eat before they go bad. Whether they’re grown in your Rooftop Farm (page 153), pilfered from a reanimated green-thumbed neighbor, or scavenged from a local fruit farm, any kind of fruit surplus can be easily remedied with a little jamming.

JAMMING BASICS

Jamming is a preservation technique dating back centuries that requires little in the way of additional ingredients: All you really need is sugar and the right combination of fruits. When heated, fruit becomes that thick spreadable stuff we all love via the transformational relationship between pectin, acid, and sugar.

PECTIN

Pectin is a naturally occurring water-soluble fiber that, working along with sugar and acid, is crucial in forming the molecular gel network needed to thicken jam to a “set” consistency. With enough time and heat, you could cook virtually any fruit down to a jammy consistency without added pectin; however, long cooking times lead to overprocessed flavors and textures, low yields, and a much less enjoyable jam. The presence of pectin speeds up and improves the setting process—the more pectin, the shorter the cooking time and firmer the set.

Commercially produced powdered pectin is often used for jamming; however, it is naturally found (in varying amounts) in all fruit and is at its highest concentration when fruit is slightly under-ripe. If you haven’t stockpiled any of the commercial stuff pre-zpoc, you can always harness the power of natural pectin by mixing high-pectin fruits like tart apple, currant, citrus rind, or cranberries in with low-pectin fruits like blueberry, strawberry, sweet cherry, and peaches. You can also extract the pectin from the skin and seeds of tart high-pectin apples by preparing a “tea” that is added to the fruit before cooking—see Pectin Tea (page 174) for more.

ACID

Acid is another key player in the gelling game, which neutralizes the charged and repellent pectin molecules so that they are able to bind together. As with pectin, acid is naturally present in fruits in varying quantities and at its most concentrated in slightly under-ripe fruits. There are commercially made and shelf-stable sources of acid that can be used in zpoc jamming. One of these is citric acid, but if you don’t have it on hand, you can mix high-acid fruits like citrus, grapes, and raspberries with low-acid fruits like sweet apples, peaches, and blueberries.

SUGAR

People often question the seemingly excessive use of sugar in jam making. Why add so much sugar to wonderfully ripe and flavorful fruit? Part of the reason is that slightly under-ripe fruits are ideal for jam making, given their higher pectin and acid content, so sugar does play a role in flavor. But perhaps more importantly, sugar completes the gelling puzzle. Sugar absorbs water molecules, effectively tying them up and forcing the pectin molecules together into the gel network needed for setting the jam.

Sugar also acts as a preservative that deters the growth of molds and other bacteria—the higher the sugar content, the longer your jam will keep. That said, in and of itself a high sugar content does not make jam safe for long-term storage. It also does not kill off botulism or other potential pathogens (that’s what hot-water processing is for!). A standard jamming rule of thumb is a 1:1 ratio of fruit to sugar. The most accurate way of achieving this is by using a scale and measuring by weight, but you can also use cup measures or any other vessel at your disposal.

COOKING JAM

It’s good practice to cook your jams in small batches of 6 cups of fruit or less—the larger the batch, the longer the cooking time you’ll need, and prolonged cooking actually breaks down the natural pectin while also killing the lovely fresh flavor of the fruit.

It is also good practice to slowly heat your fruit mixture, allowing the sugar to completely dissolve before bringing to a boil.

A hard boil for a minute or two is generally enough to achieve a proper gel. If you have a thermometer, a good rule of thumb is cooking to 8°F over the temperature at which water boils at your elevation (from sea level to 1,000 feet, for example, water boils at 220°F). A low-tech, zpoc-friendly method of checking the set is to simply take a small spoonful out of the pot and plop it onto a plate to let it cool (take the pot off the heat while you are doing this). After a minute or two, if it has cooled to a thick consistency, then you are done. If it is still too runny, bring the pot back to a boil and test again after another minute or two.

STORING JAM

Funnel your finished jams into glass home-canning jars, process in a hot-water bath, and off you go! See Canning (page 168) for instructions on canning and storing your jam long-term.

IN A STRAWBERRY JAM

Strawberries are one of the fruit crops best suited to a rooftop farm, as well as the berry you’re most likely to find kicking around in some poor undead’s yard. Strawberry jam—the king of fruit jams, perhaps—is also one of the most basic jam recipes, and the general methodology applies for most other fruit jams.

Remember to make your jams in small batches of 6 cups of fruit or less. If you have less fruit than the 6 cups called for here, just scale down the sugar accordingly, using a 1:1 ratio of fruit to sugar.

YIELDS:

About 8 x 8-oz. jars

REQUIRES:

Chef’s or survival knife and cutting board

2 large pots, one at least 18–21 qt. for processing the jam, one for cooking the jam in

1 pair of tongs

1 wide-mouthed funnel or ladle

1 potato masher, pestle, or other tools for mashing

8 x 8-oz. (or the equivalent in other sizes) glass canning jars with self-sealing lids and metal threaded screw tops

2 clean kitchen towels or other fabric

1 jar lifter, if available

Large spoon

HEAT SOURCE:

Direct, open flame or other Stovetop Hack (page 42)

TIME:

10 minutes prep

20 minutes cook time

INGREDIENTS:

6 c. strawberries, washed, hulled, and roughly chopped (about 8–10 c. whole strawberries)

⅔ c. pectin tea (see sidebar)

6 c. granulated sugar

6 tbsp. finely chopped tarragon or thyme (optional, if available)

METHOD:

Set up a cooking fire or other Stovetop Hack. Sterilize and prepare your jars, screw-top lids, and other tools for canning as per the instructions in Canning (page 168), leaving them at a gentle simmer in the pot until needed.

Set up a cooking fire or other Stovetop Hack. Sterilize and prepare your jars, screw-top lids, and other tools for canning as per the instructions in Canning (page 168), leaving them at a gentle simmer in the pot until needed.

Add the chopped berries and pectin tea to the cooking pot. Gently mash the strawberries with a fork to help stimulate the release of juice. Add the sugar, then gently bring to a boil over medium-high heat so that the sugar has a chance to completely dissolve before it comes to a rolling boil.

Add the chopped berries and pectin tea to the cooking pot. Gently mash the strawberries with a fork to help stimulate the release of juice. Add the sugar, then gently bring to a boil over medium-high heat so that the sugar has a chance to completely dissolve before it comes to a rolling boil.

Once the sugar is dissolved and the mixture is boiling, kick up the heat for a very rapid and hard boil. After a minute or two, if the mixture looks to be thickening, you can start testing its “gel” (see Turning Fruit into Jam, page 170, for more). When the jam is where you like it, remove from the heat and set aside for now.

Once the sugar is dissolved and the mixture is boiling, kick up the heat for a very rapid and hard boil. After a minute or two, if the mixture looks to be thickening, you can start testing its “gel” (see Turning Fruit into Jam, page 170, for more). When the jam is where you like it, remove from the heat and set aside for now.

Using tongs, remove the jars, screw tops, and lids from the hot water, shaking off as much water as possible, and laying upside-down to dry on a clean towel.

Using tongs, remove the jars, screw tops, and lids from the hot water, shaking off as much water as possible, and laying upside-down to dry on a clean towel.

Skim the excess foam from the top of the jam using a large spoon, then stir in the tarragon and let the pot sit to cool for about 5 minutes. Using a wide-mouthed funnel or ladle, fill each of the jars with jam, leaving about ¼-inch headspace at the top.

Skim the excess foam from the top of the jam using a large spoon, then stir in the tarragon and let the pot sit to cool for about 5 minutes. Using a wide-mouthed funnel or ladle, fill each of the jars with jam, leaving about ¼-inch headspace at the top.

Using a clean towel, wipe off any jam that is gunking up the rims and outer edges where the lid and screw tops will be going. Using tongs, place a self-sealing lid on top of each jar, then twist on a screw top.

Using a clean towel, wipe off any jam that is gunking up the rims and outer edges where the lid and screw tops will be going. Using tongs, place a self-sealing lid on top of each jar, then twist on a screw top.

Add the jars back to the canning pot, then bring the water to a rapid boil and process for 10 minutes.

Add the jars back to the canning pot, then bring the water to a rapid boil and process for 10 minutes.

Carefully remove the jars from the pot using jar lifters or tongs. Lay the jars out on towels in a cool, dark place where they can rest for 24 hours without being moved or crowded together.

Carefully remove the jars from the pot using jar lifters or tongs. Lay the jars out on towels in a cool, dark place where they can rest for 24 hours without being moved or crowded together.

Test each jar by pressing down in the center of the lid, if it still pops/clicks up and down, the jar has not sealed properly. These are still safe to eat right away, but cannot be stored!

Test each jar by pressing down in the center of the lid, if it still pops/clicks up and down, the jar has not sealed properly. These are still safe to eat right away, but cannot be stored!

Fermenting

The Night of the Living Dead is to canning what White Zombie is to fermentation—long before the Romero ghoul, there was the voodoo zombi and long before canning there was fermentation. Fermentation is a mode of preservation that has been in use for millennia and was likely humanity’s very first method of putting up foods for delayed consumption.

So what is fermentation exactly? In the simplest of terms, fermentation is the transformation of food by microorganisms. By creating an environment that is favorable to specific beneficial bacteria—lactic acid bacteria (LAB)—we can harness the natural preservation power these little critters generate.

It likely seems very counterintuitive to preserve food with bacteria, but lactic acid bacteria is a special class. According to Sandor Ellix Katz, fermentation expert and author of The Art of Fermentation, the acidifying bacteria produces inhibitory substances, including hydrogen peroxide, bacteriocins, and other antibacterial compounds, that many of the bacteria we fear most when it comes to food-borne illness—like Salmonella, E. coli, Listeria, and Clostridium—cannot survive.

Not only is food preserved by lactic acid bacteria, but it is also pre-digested, making the nutrients in it more readily available and, in many cases, creating new nutrients. “Ferments with live lactic-acid producing bacteria are especially supportive of digestive health, immune function, and general well-being,” Sandor says.

More good news: most fermentation doesn’t involve an extensive body of knowledge or precisely controlled environments—it is an ancient ritual humans have been performing for a very long time and a nifty little preservation technique worth utilizing come the zombie apocalypse.

Here is an overview of the key components:

SUBSTRATE

In fermenting culture, “substrate” is the term used for the food being fermented— it is the medium that your microbial community is surviving on. Cabbage is the substrate in sauerkraut, grapes in wine, cucumbers in pickling, and apples in cider vinegar, for example.

STARTER

Some ferments require the intentional introduction of microbes to get them started. Starters, or cultures, are used in ferments like yogurt, kefir, cheese, bread, and kombucha. However, the ferments covered in the following pages—sauerkraut, pickles, and honey fruit mead—require no starter at all. They rely solely on the microorganisms naturally present in and on the food itself in a process called “wild fermentation.”

ENVIRONMENT

As mentioned, fermentation is the process of manipulating a food’s environment to encourage the growth of beneficial bacteria. Oxygen access, hydration, salinity, and temperature are all environmental variables we manipulate when fermenting, and as we change these variables, the microbial community in our ferment will change, evolve, and adapt in response. These changes in the microbial community are typically the result of a succession of dominant bacteria, each phase producing different visible and olfactory cues—fizzing and bubbling, for example, or yeasty, tangy, or vinegary aromas.

How you manipulate the environment will depend on what you want to ferment. Fermentation can involve submerging food in (an often salted) liquid to cultivate a community of anaerobic microorganisms, as is done with sauerkraut and pickles. Or it can mean exposing food to oxygen to cultivate a community of oxygen-dependent bacteria, as is done with vinegar. Generally speaking, the higher the temperature, the faster the fermentation process will progress. At low temperatures (50°F or lower), fermentation slows significantly, which can extend the edible lifespan of your ferments. Darkness is another important environmental variable, as natural light can be harmful to many microbes.

GEAR

You’ll need containers in which to ferment. Traditionally things like ceramic crocks, glass jars, and wooden barrels have been popular, and some of these, like glass jars, will be quite easy to scavenge. Be sure to try to secure a variety of shapes and sizes—narrow necks are great for the Honey & Blackberry Mead (page 195) because they minimize the surface area exposed to air, while wide-mouthed jars or crocks are needed for vinegars because you want to maximize the amount of oxygen exposure. You’ll also need weights to keep food within the containers submerged below the fermenting liquid and pieces of clean, breathable cloth to protect some ferments from insects and other debris while allowing the gases produced by the fermentation process to be safely expelled.

READINESS & SHELF LIFE

The “readiness” of many simple ferments, like the sauerkraut, mead, and pickles covered in the following pages, is a matter of personal taste. As microbial communities change and evolve, so too will your food. In the case of something like sauerkraut, some people enjoy their ferments fairly young, mild, and crunchy, while others prefer a longer ferment to develop deeper and more intense flavor or a different texture.

Because temperature is a major contributor to the speed at which your foods will ferment, storing your ferments in cool fridge-like temperatures can slow fermentation down to an almost imperceptible pace, thereby extending the life of your ferment almost indefinitely. In a world without refrigeration, however, can ferments go “bad” or wrong? The answer is yes; see Fermenting Vegetables (page 178) and Imbibing at the End of the World (page 192) for additional discussion and troubleshooting tips.

RECOMMENDED READING: Fermentation is a useful preservation technique for many foods not covered here: milk, grains, tubers, beans, seeds, and nuts to name but a few. However, when experimenting with more complicated fermentation processes, like beer making or curing meats, there is considerably more to know and consider. The Art of Fermentation by Sandor Ellix Katz is an excellent resource that no culinary-minded zpoc survivor should be without.

Fermenting Vegetables

All vegetables have the lactic acid bacteria (LAB) needed for fermentation naturally occurring in varying quantities on their surfaces, and so the process of fermenting vegetables, at its most basic, involves creating the right conditions for these beneficial bacteria to thrive, preserving and transforming the vegetable(s) in the process. Submerging the vegetable substrate(s) under liquid (either their own or in a prepared brine) creates the needed anaerobic environment where LAB dominate, crowding out mold and other unwanted oxygen-loving bacteria.

While the following pages offer basic direction and simple recipes, zpoc survivors will find themselves in much the same situation as our ancient fridge-less ancestors did: You will need to experiment to figure out what works best in your own microclimate and for your own specific food supply and resources.

Below is an overview of the process and troubleshooting tips for the new-to-fermenting zpoc survivor, featuring many nuggets of wisdom from Sandor Ellix Katz’s fermentation bible The Art of Fermentation.

WHAT TO FERMENT

All vegetables can be fermented, but not all vegetables ferment equally well. According to Sandor, members of the Brassica family, like broccoli, Brussels sprouts, cauliflower, kohlrabi, and of course cabbage, are great for fermentation. Root vegetables like carrot, beets, radish, and turnips also ferment well. Vegetables with high water content (like zucchini or other such squash) tend to become soft and mushy quickly, and while they can be fermented successfully, they are better done in small batches and eaten quickly.

FERMENTING WITH SALT

While salt is not an absolute requirement for fermentation of vegetables, it does provide beneficial lactic acid bacteria with a competitive advantage. It’s an important flavor enhancer, even when used in small quantities, and also helps preserve a more pleasing texture by protecting the pectin molecules that give vegetables their crunch. Salt also slows the fermentation process, prolonging the edible shelf life of your ferments. Since fermentation processes speed up with rising temperatures, salt can be a very useful tool when you are faced with warm temperatures that are beyond your control.

There are two methods in which salt is generally used for veggie ferments: dry-salting and brining. Dry-salting involves applying salt directly to the substrate, to help draw natural juices from a vegetable, in conjunction with thinly slicing or otherwise breaking down cell walls (see The Extraction Method below). Brining requires submerging the vegetables in a water/salt solution (see The Brining Method below).

If you do have access to salt, skip the common table (iodized) salt when possible, which can inhibit fermentation (see Not All Salts Created Equal, page 186). Instead, go for kosher or sea salts (see Making Your Own Sea Salt, page 325).

THE EXTRACTION METHOD

For Down & Out Sauerkraut (page 181) or anything you’d like to ferment in its own juices, beating up your vegetables is a good idea. Not only is it an excellent way to get out any pent-up frustration not completely expended by brain bashing, but it also helps release the vegetable’s natural juices for the fermentation process by breaking down cell walls. First, chop, dice, or shred the vegetables in question to expose more surface area. Then have at it—you can squeeze, pound, or otherwise bruise your veg. This can be done with any (clean) tool you like, but (clean) hands always work as well.

The aim is to extract enough liquid from the vegetables that, once put into the vessel, it covers them completely. Dry-salting your shredded vegetables will also help in extracting liquid. As a reference point, Sandor recommends 3 tablespoons of salt for every 5 pounds of vegetables, though this is entirely a matter of taste and can be increased or decreased as you please. If, after shredding, salting, and squeezing, your veggies aren’t yet fully submerged, weigh them down for a few hours, then try squeezing again. If after 24 hours you still can’t get enough liquid from them, you can cover them with a little clean water instead.

THE BRINING METHOD

Brining is a good method if you want to ferment vegetables in large chunks, as in Fermented Pickled Cucumbers (page 187). Here, instead of extracting natural juices to submerge the vegetable(s), you mix up a salt-water solution for submerging. The strength of the brine is up to you, but a good rule of thumb is to use a 5% brine—that is, a brine that is 5% salinity by weight (see sidebar on previous page for a quick reference guide).

When you taste a 5% brine, it may seem excessively salty. Using the same quantity in a dry-salt application would be entirely too salty for straight consumption, but because the salt in a brine pulls out liquid from the submerged vegetables via osmosis, increasing the total amount of liquid, the salt content is diluted.

Once you’ve consumed your ferment, the remaining brine can be used in any number of ways—as an all-purpose vinegar replacement in dressings, marinades, and more; as a starter culture for cheesemaking; or as a medium for soaking beans and grains.

ADDING FLAVOR

Don’t forget the flavor enhancers! Dip into the spice kit in your bug-out bag and get to experimenting. Dried oregano, red pepper flakes, juniper berries, caraway, dill, and celery seeds are all excellent spice options. So are black peppercorns, cumin seeds, coriander seed, fennel, mustard seed, whole clove, and allspice. In addition to adding flavor, spices can also act as mold inhibitors, slowing any growth that might occur on the ferment’s surface.

Some excellent fresh flavor enhancers include ginger, scallion, and hot peppers. Fresh herbs from your window or rooftop farm could also be used, though their flavors tend to dissipate more quickly than dried.

TIMING

Judging when your ferment is “ready” to eat is a matter of personal taste. After as little as 3 days, your vegetables will have noticeably changed, remaining crunchy but taking on a mild and distinctly fermented flavor. However, since fermentation will primarily function as a mode of preservation in a zpoc context, you will probably need your ferments to last far longer. If you have access to a Root Cellar (page 190), a cold basement during the winter, or even a hole underground (see Burying Your Bounty, page 172), moving your ferments to a cold fridge-like place (35°F–38°F) once you deem them to be delicious will keep them stable and edible for several months or longer.

TROUBLESHOOTING

Ferments are generally quite hardy, and there is little that can go so wrong with them that they become unfit to eat. Says Fred Breidt, a microbiologist for the US Department of Agriculture who specializes in fermentation, “Risky is not a word I would use to describe vegetable fermentation. It is one of the oldest and safest technologies we have.”

According to Sandor, however, if you have never fermented anything before, lots of things that happen naturally or are commonplace might seem to have ruined your ferment.

SURFACE FOAM & MOLD

Surface foam and mold are both natural parts of the fermenting process. They will not spoil your batch and can simply be skimmed off.

PINK FERMENTS

A pink-tint to your ferment indicates the growth of yeast, which typically thrives in ferments with high levels of salt (greater than 3% salinity). Your ferment is still completely safe to eat.

FOUL SMELLS

Fermentation smells, well, funky, by many people’s definition. This is totally normal! If you smell something truly revolting or putrid, it will usually be accompanied by serious and deeply penetrating surface growth. Depending on how deep the offending growth has penetrated, you may be able to remove the offending layer and save the batch—be sure to overcompensate by digging out a few additional inches when removing the offensive growth!

SLIMY FERMENTS

A thick, slimy, or gooey ferment usually indicates the abnormally quick growth of L. cucumeris and L. plantarum bacteria, which often happens in hot environments. It might just be a natural stage of your ferment’s evolution that will dissipate over time, but if your ferment remains slimy over days or weeks, scrap the batch and try again in cooler weather.

DOWN & OUT SAUERKRAUT

Let’s be real—if you have the ingredients, resources, and time to make sauerkraut, you’re really not all that down and out. I mean, yeah, there’s the whole zombie apocalypse collapse of society thing, but yay! You get to have sauerkraut!

Sauerkraut is definitely one of the simplest and easiest ferments, great for beginners (see Fermenting Vegetables, page 178). All it requires is some fresh cabbage, salt, and a little time for nature to do its thang.

The recipe here is a classic sauerkraut that can be adapted, switched up, and flavor bombed (think kimchi! See Variation: Killer Kimchi on page 182) as much or as little as you like or as resources dictate. While this recipe calls for specific measurements of seasoning (salt and cumin), it really is a very “to your own taste” kinda deal—so experiment and have fun.

YIELDS:

About 3 qt. of sauerkraut

REQUIRES:

Chef’s or survival knife and cutting board

3 x 1-qt. ceramic crocks or glass jars

1 large mixing bowl

1 small bowl

3 large pieces of clean breathable fabric

String or large elastic bands

TIME:

60 minutes prep

At least 3–5 days fermenting time

INGREDIENTS:

5 lb. cabbage

3 tbsp. salt (preferably Kosher)

3 tbsp. cumin seeds (if available)

METHOD:

Before beginning, wash your hands. Thoroughly wash the crock(s) or jar(s) and all tools you will be using. If you do not have soap, sterilize the vessel(s) and tools in boiling water for 10 minutes before beginning.

Before beginning, wash your hands. Thoroughly wash the crock(s) or jar(s) and all tools you will be using. If you do not have soap, sterilize the vessel(s) and tools in boiling water for 10 minutes before beginning.

Remove the outer leaves of the cabbage, quarter each head, and remove the core. Thinly slice the cabbage, dropping it into a large mixing bowl as you go. With each addition, give the cabbage a quick squeeze to start the release of its liquid.

Remove the outer leaves of the cabbage, quarter each head, and remove the core. Thinly slice the cabbage, dropping it into a large mixing bowl as you go. With each addition, give the cabbage a quick squeeze to start the release of its liquid.

When you have about ⅓ of your cabbage cut, sprinkle with 1 tablespoon of salt and cumin seeds, then continue squeezing and pressing the cabbage to release enough liquid to submerge that amount of cabbage. This will take several minutes of squeezing. Drain off the liquid into a small bowl. Repeat with the remaining cabbage.

When you have about ⅓ of your cabbage cut, sprinkle with 1 tablespoon of salt and cumin seeds, then continue squeezing and pressing the cabbage to release enough liquid to submerge that amount of cabbage. This will take several minutes of squeezing. Drain off the liquid into a small bowl. Repeat with the remaining cabbage.

In several small additions, pack the cabbage into the jars or crocks very tightly to eliminate air pockets, adding back liquid to cover between each addition—as you fill the jars you may run out of liquid, this is OK. Leave 1–2 inches of headspace in the container for the additional water content that will be released by the cabbage.

In several small additions, pack the cabbage into the jars or crocks very tightly to eliminate air pockets, adding back liquid to cover between each addition—as you fill the jars you may run out of liquid, this is OK. Leave 1–2 inches of headspace in the container for the additional water content that will be released by the cabbage.

Cover the jars/crocks with the breathable fabric and secure with string or an elastic band. If after about 24 hours there has not been enough liquid released to cover the cabbage entirely, top the jars off with a salted water solution (salt content up to you). Put a small plate, a water-filled plastic bag, or some other weight inside the jar or crock to weigh down your kraut and ensure it remains completely submerged.

Cover the jars/crocks with the breathable fabric and secure with string or an elastic band. If after about 24 hours there has not been enough liquid released to cover the cabbage entirely, top the jars off with a salted water solution (salt content up to you). Put a small plate, a water-filled plastic bag, or some other weight inside the jar or crock to weigh down your kraut and ensure it remains completely submerged.

Replace the breathable fabric and secure. Store your kraut in as cool and dark as a spot as possible. If using a clear glass vessel, cover it with dark fabric to keep light out.

Replace the breathable fabric and secure. Store your kraut in as cool and dark as a spot as possible. If using a clear glass vessel, cover it with dark fabric to keep light out.

Taste it after a few (3–5) days. Once the kraut tastes good to you, you can start eating it. The remaining kraut will be perfectly safe left covered and fully submerged in its original liquid-filled crock. If stored in a cool (lower than 50°F) place, the kraut should stay relatively crispy and edible for many months.

Taste it after a few (3–5) days. Once the kraut tastes good to you, you can start eating it. The remaining kraut will be perfectly safe left covered and fully submerged in its original liquid-filled crock. If stored in a cool (lower than 50°F) place, the kraut should stay relatively crispy and edible for many months.

Kimchi, the quintessential Korean condiment that can be eaten with almost anything, is a simple but extremely tasty sauerkraut variation perfect for those who like a spicy kick and have access to some specific Asian seasonings. The most traditional seasonings found in kimchi include powdered hot peppers (also known as Korean red pepper powder or kochukaru), garlic, onion and/or scallion, fish sauce, and ginger. The hot pepper powder is the backbone of flavor for this preparation and really has no substitute, but in the absence of fish sauce you could use the equivalent volume of a mild salt-and-water brine.

TO MAKE: Slice, rough chop, or julienne (your choice) 4 pounds of cabbage. Add to a large mixing bowl, salt heavily, then let sit for several hours, stirring occasionally. In the meantime, add about a gallon and a half (24 c.) of water to a large pot over medium-high heat. Add 2 tablespoons flour (traditionally rice flour though any glutinous flour would work) for every cup of water. Mix well and heat until the water and flour mixture begins to thicken. Remove from heat and set aside to cool to room temperature. In a small bowl, mash 1 cup powdered hot pepper, ½ cup minced garlic, ½ cup of onion/scallion, 2 tablespoons fresh ginger, and ½ cup of light-amber fish sauce into a thick paste. Add to the flour/water mixture and mix until combined. Rinse off the excess salt from the cabbage and transfer the cabbage to the vessel you will ferment in, then add ½ pound carrot and ½ pound radish, thinly slice or julienned. Cover with the liquid seasoning and stir to combine. Taste and adjust seasoning if needed. Follow the same process detailed in the sauerkraut recipe to weigh down and cover the kimchi. Ferment for at least a week before tasting.

Zpoc Pickling

When people think of pickled anything—cucumbers are the natural go-to, but also beets or green beans—they immediately think of brine, the salty, savory, and acidic liquid that many pickled foods are submerged in.

Brine is the cornerstone of pickling, but the process can be done through either fermentation or hot-water canning. Each method produces a vastly different result. The recipes that follow cover both methods—a traditional sour cucumber pickle using fermentation and a brined bean recipe using hot-water canning.

PICKLING THROUGH FERMENTATION

Pickling through fermentation follows the general principles outlined in Fermenting Vegetables (page 178) but utilizes a prepared brine (as opposed to juices naturally extracted from the veggies) and is a useful method when you want to ferment large pieces of (or whole) vegetables.

Cucumbers are a natural choice for pickling, and a pre-zpoc food I for one will sorely miss munching on while standing in front of the fridge in my jammies. But according to fermentation expert Sandor Ellix Katz, cukes aren’t the ideal candidate for fermented pickling. Don’t misread this: They are still totally worthy of fermenting! But because of their already-high water content, coupled with the (hot) seasons during which they grow, they tend to ferment rather quickly and become soft. You can combat this by adding grape, oak, cherry, or horseradish leaves to the ferment—anything that can give it a good shot of tannins.

Using the basic proportions of salt, water, and vinegar set out in the recipe for Fermented Pickled Cucumbers (page 187), you can ferment any number of vegetables—radishes, turnips, Brussels sprouts, cauliflower, carrots, onions, hot peppers, and eggplant, to name but a few. The addition of various spices can not only flavor your pickles, but also help further discourage unwanted bacteria; cinnamon, garlic, mustard seeds, and cloves have excellent antimicrobial properties.

PICKLING THROUGH CANNING

If you’re the carpe-diem type survivor, you may be too impatient to wait for fermented pickles, which can take anywhere from days to weeks. Canned pickles, however, rely on a punchier and stronger brine and can be ready in a matter of hours (especially when using soft and/or small veggies that will soak up the brine more quickly). Another added benefit to canned pickles? They last longer than their fermented cousins, especially in the absence of cool storage temperatures.

Because they don’t undergo the same pre-digestive process that fermented pickles do, canned pickles are crispier. You will find that some vegetables (like beets or the green beans in In a Dilly of a Pickled Beans, page 189) are better off blanched first, as they will remain too crunchy or tough to eat with a hot-water pickling. Unlike brines used for fermenting, brines for canned pickles should be nice and hot when added to the veggies to encourage good penetration.

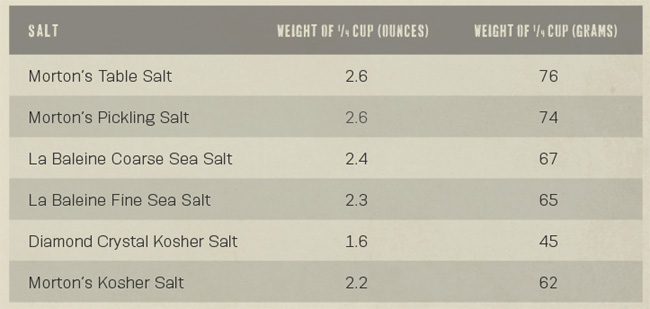

Not All Salts Created Equal

Along with other pre-zpoc relics like fire-arms, seeds, and Twinkies, salt is going to be one of those items you should grab whenever possible. But when you’re using it for more than sprinkling on your fries or seasoning your guacamole, the world of salt gets a lot more complicated. Here is an overview of the different types and uses of salt:

TABLE SALT

Table salt is a highly processed and refined form of sodium chloride containing added iodine and anticaking agents. While table salt is useful for general seasoning and often used for curing meats, it can impact the texture, flavor, and overall quality of canned foods. It can also inhibit fermentation.

USE FOR: General seasoning, curing

KOSHER SALT

Kosher salt is a coarser and (typically, though not always) additive-free form of sodium chloride. It has a much larger crystal size than table salt and derives its name from its use in removing surface blood from meats during the koshering process. Kosher salt can be used for most applications, though its coarseness should be considered when substituting in recipes calling for regular or finer salts (see Salt: Weight Matters on page 185).

USE FOR: General seasoning, curing, fermentation, canning

SEA SALT

Unlike table and kosher salts, which come from salt mines, sea salt is produced by the evaporation of seawater. Sea salt is also primarily composed of sodium chloride but may contain other minerals. The mineral makeup of sea salt varies with the locale from which it is produced, resulting in differing flavors and appearances. Sea salt is commercially produced in both fine and coarse grains.

USE FOR: General seasoning, curing, fermentation, canning

PICKLING SALT

Pickling salt is a very fine-grained form of sodium chloride. Like both kosher and sea salts, it contains no added iodine or anticaking agents. Because of its fine grain, it dissolves very quickly, making it ideal for pickling brines or any other solutions needing salt.

USE FOR: General seasoning, canning, fermentation

CURING, OR PINK, SALT

Curing salts are a very specialized product used in the preservation of meats. Sodium nitrite and (sometimes) nitrate are added to regular table salt to inhibit harmful bacteria like Clostridium botulinum, which causes botulism. They also help meat retain its red color through the curing process and enhance its meaty flavor. Because these salts are needed in very small quantities and can be lethal in large quantities, they are typically colored pink so as to distinguish them from table salt. Follow package directions carefully.

USE FOR: Dry-curing or brining only

FERMENTED PICKLED CUCUMBERS

If you never tried fermented cucumbers pre-zpoc, then you will be in for a treat. Unlike many canned pickles, fermented cucumbers tend to be a little more interesting in the flavor department—slightly acidic with a nice little sour kick and a texture not as crisp or crunchy as their canned cousins. Fermented cucumbers also rely far less on vinegar than do the canned variety.

When fermenting cukes, it is best to use extra-crunchy varieties specifically bred for the purpose—Kirby, Little Leaf, or Country Fair for example—because the high water content of most cucumbers causes them to become mushy over long periods of fermenting. However, the process can be done with any variety and the onset of mushiness delayed with a handful of tannin-rich grape, cherry, oak, or horseradish leaves.

YIELDS:

10 pickles

REQUIRES:

Chef’s or survival knife and cutting board

1 small pot

1 large (18–21 qt.) pot

1 pair of tongs

1 wide-mouthed funnel or ladle

2–3 × 1-pt. or 2 × 1-qt. glass canning jars or ceramic crock(s) (or the equivalent in other sizes)

2 or more swatches of clean breathable fabric String or large elastic bands

HEAT SOURCE:

Direct, open flame or other Stovetop Hack (page 42)

TIME:

30 minutes prep

At minimum, 3–5 days fermenting time

INGREDIENTS:

8 c. clean potable water

3.5 oz (100g) salt, preferably pickling or kosher, (see Not All Salts Created Equal, page 186)

¼ c. vinegar, preferably white

10 pickling cucumbers, such as Kirby, rinsed well

Fresh dill, if available, to taste

Fresh garlic, if available, to taste

1–2 fresh chili peppers, cut into rings

Peppercorns, if available, to taste

1 handful fresh grape, cherry, oak, and/or horseradish leaves, if available

METHOD:

Set up a cooking fire or other Stove-top Hack. You can sterilize the jars and equipment you will be using in boiling water if you’d like or feel it would be prudent (if, for example, you are working in a space that was highly trafficked by the undead), but if you have soap and hot water with which to wash them, that should be enough.

Set up a cooking fire or other Stove-top Hack. You can sterilize the jars and equipment you will be using in boiling water if you’d like or feel it would be prudent (if, for example, you are working in a space that was highly trafficked by the undead), but if you have soap and hot water with which to wash them, that should be enough.

In a small pot, bring half the water and all of the salt to a boil. Remove from heat, then add the rest of the water and the vinegar. Set aside and allow the mixture—your brine—to cool to ambient temperature.

In a small pot, bring half the water and all of the salt to a boil. Remove from heat, then add the rest of the water and the vinegar. Set aside and allow the mixture—your brine—to cool to ambient temperature.

Using clean hands or tongs, pack the cucumbers, dill, garlic, chili peppers, peppercorns, and leaves into the jar(s).

Using clean hands or tongs, pack the cucumbers, dill, garlic, chili peppers, peppercorns, and leaves into the jar(s).

Cover the cucumbers in each of the jars with brine, making sure there is enough liquid to cover them completely while also leaving 1–2 inches of head-space. Put a small plate, a water-filled plastic bag, or some other weight inside the jar or crock to make sure everything stays completely submerged.

Cover the cucumbers in each of the jars with brine, making sure there is enough liquid to cover them completely while also leaving 1–2 inches of head-space. Put a small plate, a water-filled plastic bag, or some other weight inside the jar or crock to make sure everything stays completely submerged.

Cover each container with a swatch of breathable fabric, and secure with a rubber band or piece of string to keep out unwanted visitors.

Cover each container with a swatch of breathable fabric, and secure with a rubber band or piece of string to keep out unwanted visitors.

Store in a cool, dry place out of direct light. Check daily and change the covering if it becomes damp. Skim off any scum or mold that might develop on the surface, and top up the jars as needed with a solution of equal parts potable water and salt.

Store in a cool, dry place out of direct light. Check daily and change the covering if it becomes damp. Skim off any scum or mold that might develop on the surface, and top up the jars as needed with a solution of equal parts potable water and salt.

Test a pickle after about 10 days (or as soon as 3 days in hot weather). If they taste good to you, then they are ready to eat! Otherwise, continue fermentation until they are where you like them. They will not “spoil” per se, but they will eventually, after about 3 weeks or so, become noticeably soft—see Troubleshooting (page 180) for more information on evaluating your ferment. Store in cool (50°F or lower) temperatures to slow the fermentation and extend the shelf life.

Test a pickle after about 10 days (or as soon as 3 days in hot weather). If they taste good to you, then they are ready to eat! Otherwise, continue fermentation until they are where you like them. They will not “spoil” per se, but they will eventually, after about 3 weeks or so, become noticeably soft—see Troubleshooting (page 180) for more information on evaluating your ferment. Store in cool (50°F or lower) temperatures to slow the fermentation and extend the shelf life.

IN A DILLY OF A PICKLED BEANS

Take a classic treatment of cukes and apply it to green beans and what do you get? Dilly beans. OK, so I am not reinventing the wheel with this recipe—dilly beans are a classic home pickling favorite that make use of the more contemporary method of pickling whereby a high-acid vinegar and salt brine plus canning is used for long-term preservation (see Zpoc Pickling, page 184).

Storing vegetables long-term via canning proves to be better than fermenting for vegetables with a high water content like cucumbers and green beans, which otherwise tend to get mushy relatively quickly. But using canning to pickle vegetables requires a certain level of salinity and acidity, so if you are missing either salt or vinegar, you might be better off fermenting!

The basic brine in this recipe can be used on almost anything, from spruce tips in the spring, to nasturtium seeds (“poor man’s capers”) in the summer, to beets in the early fall, and can easily be adapted based on the vegetables and seasonings you have on hand.

YIELDS:

4 pt. of canned beans

REQUIRES:

Chef’s or survival knife and cutting board

1 large pot, 18–21 qt.

1 medium pot

4 × 1-pt. (or the equivalent in other sizes) glass canning jars with lids and metal threaded screw tops

1 pair of tongs or jar lifter

1 large mixing bowl

2 clean kitchen towels or other pieces of fabric

HEAT SOURCE:

Direct, open flame or other Stovetop Hack (page 42)

TIME:

30 minutes prep

1 week pickling time

INGREDIENTS:

2 lb. green beans, rinsed well and trimmed to fit jars with ¾″ headspace

3 c. potable water, plus more for blanching

3 c. vinegar, preferably white, though white wine vinegar or cider vinegar will also work

6 tbsp. sugar

¼ c. plus 1 tbsp. (90 g) pickling salt, or ½ c. kosher (see Not All Salts Created Equal, page 186)

8 lightly crushed fresh garlic cloves, divided

8 sprigs fresh dill, divided

2 tsp. black peppercorns, divided

4 tsp. red chili flakes, divided

METHOD:

Start a cooking fire or other Stovetop Hack. Add enough clean potable water to fill a large pot about

Start a cooking fire or other Stovetop Hack. Add enough clean potable water to fill a large pot about  of the way full, then set on high heat to boil. Once boiling, blanch the beans for about a minute. If you have access to cold water and/or clean ice, shock the beans in a large bowl to prevent further cooking and to preserve their color.

of the way full, then set on high heat to boil. Once boiling, blanch the beans for about a minute. If you have access to cold water and/or clean ice, shock the beans in a large bowl to prevent further cooking and to preserve their color.

Using the same large pot and water, sterilize and prepare the jars and other tools for canning as per the instructions in Canning (page 168).

Using the same large pot and water, sterilize and prepare the jars and other tools for canning as per the instructions in Canning (page 168).

In a medium pot, bring 3 cups water, vinegar, sugar, and salt to a boil, at which point the sugar and salt will have completely dissolved. Remove from heat and set aside to cool slightly.

In a medium pot, bring 3 cups water, vinegar, sugar, and salt to a boil, at which point the sugar and salt will have completely dissolved. Remove from heat and set aside to cool slightly.

Using tongs, remove the jars, lids, and screw tops from the hot water, shaking as much excess water off as possible, and lay upside-down to dry on a clean towel.

Using tongs, remove the jars, lids, and screw tops from the hot water, shaking as much excess water off as possible, and lay upside-down to dry on a clean towel.

With thoroughly washed hands or tongs, divide the garlic, dill, peppercorns, and chili flakes among the empty but still-warm jars. Next add the trimmed beans, making sure there is about ¾ inch of head-space at the top of each jar. Divide the brine among the jars, pouring over the beans to cover completely and leaving about ½ inch of headspace. Place a lid on top of each jar and twist on the screw tops.

With thoroughly washed hands or tongs, divide the garlic, dill, peppercorns, and chili flakes among the empty but still-warm jars. Next add the trimmed beans, making sure there is about ¾ inch of head-space at the top of each jar. Divide the brine among the jars, pouring over the beans to cover completely and leaving about ½ inch of headspace. Place a lid on top of each jar and twist on the screw tops.

Add the jars back to the large pot and bring to a rapid boil, processing the jars for 10 minutes once you reach the boil.

Add the jars back to the large pot and bring to a rapid boil, processing the jars for 10 minutes once you reach the boil.

Lay the hot jars out on towels in a cool, dark place where they can rest for 24 hours without being moved or crowded together. Test each jar by pressing down in the center of the lid; if it still pops/clicks up and down, the jar has not sealed properly. These jars are still safe to eat right away, but cannot be stored. Store sealed jars in a cool, dark location.

Lay the hot jars out on towels in a cool, dark place where they can rest for 24 hours without being moved or crowded together. Test each jar by pressing down in the center of the lid; if it still pops/clicks up and down, the jar has not sealed properly. These jars are still safe to eat right away, but cannot be stored. Store sealed jars in a cool, dark location.

Building a Root Cellar

Long before the advent of modern refrigeration there were simple root cellars—underground storage used to put up root crops, apples, cheese, and other hardy perishables for the winter, as well as for short-term storage of perishables like meat.

Any root cellar relies on three things for its food preservation abilities: low temperatures, ample ventilation, and high humidity. The best root cellar will be at least 10 feet deep, where the underground temperature remains a reasonably stable 55°F–60°F regardless of weather; cold temperatures also slow the release of ethylene gas and the growth of microorganisms, both of which cause fruits and vegetables to rot. Hardwood is the best material to use for walls, shelving, and doors, as it is not much affected by nor will it affect the temperature inside.

Adequate ventilation is needed to preserve foods and to take advantage of lower aboveground temperatures during colder seasons. A simple two-pipe siphon system will aid in temperature control not only by drawing in heavier, colder air and allowing lighter, warmer air to escape, but also by moving the ethylene gas that causes spoilage out of the cellar.

To create a siphon, run two pipes from aboveground through the earth and into the cellar. One pipe should terminate high up in the chamber, about a foot from the ceiling, while the other should terminate about a foot from the floor. You should protect the open top of each pipe with a little screen and a slanted roof to keep out insects, animals, debris, and precipitation. If temperatures dip below freezing, you can close off one (or both) of the pipes to maintain above-freezing temperatures in the cellar.

Humidity is the final variable that needs to be monitored—fruits, veggies, and most cheeses are best stored in a high level of humidity, 85%–95%. If you can rustle one up, a hygrometer—which measures humidity—is a useful cellar addition. Earthen floors will aid in keeping moisture levels up, and by adding a good thick layer of gravel, you can increase humidity by soaking the floor as needed without creating a muddy mess. Canned goods can also be stored in the cellar, though the higher humidity needed for fresh foods can cause metal lids and screw tops to rust—this can be remedied by creating a two-chamber cellar or two completely separate cellars with one dedicated to canned goods.

ROOT CELLAR

RECOMMENDED READING: For more on building and storing foods in root cellars, check out Root Cellaring by Mike and Nancy Bubel.

Imbibing at the End of the World

While I would not recommend facing a full-on horde while under the influence of intoxicants (no besotted brain bashing, please!), I do wholeheartedly support the crafting of fine alcoholic beverages during an undead uprising. Granted, you won’t have much time or desire to get hammered during the initial stages of the outbreak. Once things have settled and you have found yourself in a relatively stable situation, though, all you need is access to some fruits and sugar or honey, and you can ferment some lovely alcoholic beverages. Because really, who wants to live in a undead world devoid of booze? Not. Me.

There are many different ways to go about making alcoholic beverages, and over the centuries we have boiled it down to a science. Home wine making and beer brewing is fairly commonplace pre-zpoc, a DIY market all unto itself replete with its own gadgetry and specialized equipment. But making palatable (and even downright tasty) alcoholic beverages can be incredibly easy. Meads, wines, and ciders can all be made with a few basic ingredients and a surprisingly simple method—so that even in the midst of humanity’s downfall, you can still kick back with a bevy at the end of a long day.

SIMPLE FERMENTED BEVERAGES

MEADS

The simplest of all alcoholic zpoc concoctions is a straight mead, made from water and raw honey. Why raw honey? Because it contains that key ingredient needed for fermenting sugars into alcohol: yeast. A 4:1 ratio of water to honey is a good rule of thumb.

Meads can be so much more than honey and water, however! Especially if you have access to fresh and beautifully ripe fruits from your rooftop farm or a reliable scavenging locale like a fruit farm or someone’s backyard cherry or apple tree. Fruits, especially those with edible skins, are also an excellent source of fermenting yeasts in the absence of raw honey. The amount of fruit you add is up to you and will probably depend on what you have on hand and can afford to use. Berries and other small fruits can be added to the mix whole; for larger fruits, rough chop them into smaller pieces first.

WINES

Not surprisingly, given the pre-zpoc prevalence of wine, grapes are one of those fruits perfect for fermenting. They contain an ideal balance of sugars, acids, and tannins to keep yeasts happy, and their skins are rich sources of yeast—so rich in fact that fermentation begins almost immediately after the grapes are crushed. So if you grow or stumble on grape vines during the zpoc, harvest the grapes when they are full and plump. Put whole bunches (stems and all) into the vessel you will use to ferment them and crush those suckers good. If you want a white wine, press the juice from the skins, stems, and pulp as soon as the mashed mixture begins to froth (usually a couple of hours or so) and let the juice ferment on its own. For red, let the whole mash ferment together longer—a few days—before pressing out the liquid to continue fermenting on its own.

CIDER & PERRY

Cider is fermented apple juice, while a perry is fermented pear juice. Both are delicious and fairly straightforward to make. Apple and pear trees are more likely finds than other fruits in a scavenging mission, and even if an apple or pear tree produces fruit that is too sour or mealy to eat, chances are it can still produce a decent beverage. The main challenge in making cider or perry is in pressing the juice out of the fruit. This is best done by finely chopping then mashing whole fruits, and then, as with grapes, pressing the juice out of them once the mash gets foamy. It will take a lot of fruit to get a little juice, so these kinds of ferments are really only viable when you have an abundance of apples or pears.

RECOMMENDED READING: Because beer making, or fermenting alcohol from the complex carbohydrates of cereal grains, is a much more involved practice than meads, wines, and ciders, it might be difficult to do in a zpoc setting, and I will not get into the nitty-gritty here. However, if you are interested in learning more, check out How to Brew: Everything You Need to Know to Brew Beer Right the First Time by John J. Palmer.

HOW TO MAKE SIMPLE MEADS

1. Mix all ingredients together in a wide - mouthed vessel, stirring frequently.

Once you add all mead ingredients to the fermenting vessel, stir contents vigorously until a nice thick layer of bubbles appears on top, then securely cover with a breathable cloth. Continue to stir your mixture several times daily, as aeration will continue to stimulate the yeast’s activity. The fermentation will typically happen in stages, especially if the sugar source contains both fructose and glucose, as honey does. The first phase of fermentation will sort of be like the initial stages of the zpoc. You will see a lot of action happening in the form of bubbling and brewing as the ravenous yeast devours the glucose. The feeding frenzy will start and peak quickly, over the span of several days.

2. Strain fruit and transfer to narrow-necked vessel then close off with air lock.

Follow your nose: Once the yeasty stage has passed and your brew smells sweet and pleasant, you can strain out the fruit. Don’t toss that fruit—you can eat it straight or cook/bake with it! Depending on the type of fruit, the optimal window for its removal can come and go in as little as a day, after which point the fruit will start to sour and negatively impact your brew, so close attention is needed through this first phase.

Once the fruit has been removed, you can drink the fruity, young, and lightly alcoholic “green” ferment if you’d like, or ferment it further to produce a higher alcohol content. If you want to continue the fermentation process, when you strain off the fruit, transfer the remaining liquid to a narrow-necked vessel. Something like a carboy or a bail-top bottle works well to minimize the surface area exposed to air, useful because the ferment now hosts air-loving bacteria that can turn it into vinegar if given a steady oxygen supply.

An air lock is also needed to allow the gas produced during fermentation out while preventing air from getting in to the vessel. You can easily air lock any vessel by placing a balloon or even a condom over the top. Alternatively, you can drill a hole into a cork and insert a line of plastic tubing through it; the end not in the vessel should rest in a jar or glass filled with water. Top up your vessel with a 4:1 mixture of water to sugar/honey to raise the liquid level to the bottle’s neck, again to minimize the amount of liquid exposed to air. This new liquid, and the aeration from the transfer, will also kick off another bout of bubbly fermentation.

3. Rack to remove lees and top off again if needed.

Once this second stage of bubbling has subsided completely (a few weeks to a couple of months), it is time to “rack” your bevy—that is, remove the spent yeast, known as the “lees,” that will have fallen to the bottom of the vessel. Pour off the ferment into a second vessel until you see the slightly thicker opaque lees just starting to emerge. The lees are totally consumable and vitamin rich; you can drink them, add them to soup or tea, or bake them into bread. Once they’re removed, transfer the bevy back to the vessel and either drink up or top it up again with a 4:1 ratio of water to sugar mixture and let it do its bubbly thang once more.

4. Once the second ferment has stopped, bottle then age.

When this active bout of fermentation is done (a few weeks to a few months), the fermentation should be complete—in ferment lingo, you will have fermented “to dryness,” which means all available sugars will have been converted to alcohol. You can drink up at this point, and if you have a large quantity, you can bottle the excess and store for further aging. Some ferments become much better with aging, so if your ferment tastes less than great at this point, try aging it! But be sure that the fermentation has stopped before bottling—active fermentation creates gas that in turn creates pressure. This pressure can cause dangerous explosions in airtight bottles. And you don’t want to be that guy/girl—the one who survived throngs of undead predators long enough to make their own mead, only to be killed by a stray bottle cap.

HONEY & BLACKBERRY MEAD

As covered in Imbibing at the End of the World (page 192), mead can be made with little more than water and raw honey. Fermentation expert and author of The Art of Fermentation Sandor Ellix Katz offers a 4:1 water to honey ratio as a flexible rule of thumb for straight honey meads. When using very sweet fruits, he suggests cutting this ratio down to 5:1 or even 6:1.

While raw honey ups the active yeast content of your mead—the key ingredient for converting sugars into alcohol—any fruits with edible skins used in the initial ferment will provide yeast as well, meaning that, for fruit meads, you could use pasteurized honey, granulated sugar, or another sweetener instead. Commercially made dry-active yeast could even be sprinkled in to help things along in raw honey’s absence.

YIELDS:

About 1½ gal. of mead

REQUIRES:

Chef’s or survival knife and cutting board A large wide-mouthed glass or ceramic vessel, to hold 1½ gal. of liquid

1 large (or several smaller) carboy or bail-top to hold 1½ gal. of liquid

Large wooden spoon or other tool for stirring Balloon or other improvised air lock

TIME:

30 minutes prep

Approx. 1 week for initial ferment

Approx. 6 months for a strong mead

INGREDIENTS:

1½ gal. clean water

6 c. raw honey

8 c. blackberries, washed thoroughly

METHOD:

Add 1½ gallons of clean water to your fermenting vessel, allowing it to come to ambient temperature if needed. Add the honey and stir until it is completely dissolved (this may take a few minutes). Reverse the direction of your stirring every so often to aerate the water and honey.

Add 1½ gallons of clean water to your fermenting vessel, allowing it to come to ambient temperature if needed. Add the honey and stir until it is completely dissolved (this may take a few minutes). Reverse the direction of your stirring every so often to aerate the water and honey.

Add the berries to the honey/water mixture and give a good stir again.

Add the berries to the honey/water mixture and give a good stir again.

Weigh down the berries with a clean plate, a clean plastic bag filled with water, or some other weight, to ensure they are completely submerged.

Weigh down the berries with a clean plate, a clean plastic bag filled with water, or some other weight, to ensure they are completely submerged.

Cover the vessel with a breathable cloth and secure it from critters with a string. If your vessel is transparent, cover it with a dark fabric to keep out light.

Cover the vessel with a breathable cloth and secure it from critters with a string. If your vessel is transparent, cover it with a dark fabric to keep out light.

Stir the mixture several times daily. You will soon see active foaming and bubbling and detect a yeasty aroma—this is a good sign!

Stir the mixture several times daily. You will soon see active foaming and bubbling and detect a yeasty aroma—this is a good sign!

Once the initial foaming and bubbling has subsided and you detect a sweet, pleasant smell, strain off the fruit. You can eat it or incorporate it into baked goods.

Once the initial foaming and bubbling has subsided and you detect a sweet, pleasant smell, strain off the fruit. You can eat it or incorporate it into baked goods.

You can also drink your lightly alcoholic sweet “green” mead now. However, if you’d like to continue the fermentation process to yield a more alcoholic beverage, transfer the liquid to a narrow-necked vessel, like a carboy. If the liquid does not reach the bottom of the neck, top it off with some additional water/honey mixture. Air lock the vessel with a balloon, condom, or other improvised air-locking top.

You can also drink your lightly alcoholic sweet “green” mead now. However, if you’d like to continue the fermentation process to yield a more alcoholic beverage, transfer the liquid to a narrow-necked vessel, like a carboy. If the liquid does not reach the bottom of the neck, top it off with some additional water/honey mixture. Air lock the vessel with a balloon, condom, or other improvised air-locking top.

The aeration caused by transferring the ferment to a new vessel, plus any added liquid, will kick off another round of active fermentation. Once this second round subsides (6–8 weeks or so), siphon the liquid into another narrow-necked vessel, leaving behind the dead yeast that has settled at the bottom (the lees). Top up again if needed, and secure with an air lock. Once this last round of bubbly fermentation subsides, you can bottle the mead for aging in clean jars with screw tops or other well-fitted caps, or enjoy in its current state if you’d like.

The aeration caused by transferring the ferment to a new vessel, plus any added liquid, will kick off another round of active fermentation. Once this second round subsides (6–8 weeks or so), siphon the liquid into another narrow-necked vessel, leaving behind the dead yeast that has settled at the bottom (the lees). Top up again if needed, and secure with an air lock. Once this last round of bubbly fermentation subsides, you can bottle the mead for aging in clean jars with screw tops or other well-fitted caps, or enjoy in its current state if you’d like.

Drying, Smoking, Curing, & Brining

Catching wild animals, particularly for the uninitiated zpoc survivor, will not be easy. Even when you are able to hunt down some meat for supper, you will probably not have a surplus in need of preserving. Nonetheless, knowing how to put up meat and fish is a handy zpoc survival skill and might become quite useful as you become a more proficient hunter and head out Into the Wild (page 251).

The preservation of meat poses more of a challenge and carries more risk than that of fruits and vegetables, as meat and fish offer virtually no carbohydrates—a nutrient that in fruit and vegetable preservation allows the usual lactic acid bacteria and yeasts to flourish and out-compete potentially harmful pathogens.

Instead, meat preservation relies on creating conditions in which harmful bacteria like Salmonella, E. coli, Listeria, C. Botulinum, and other Clostridium are outcompeted or inhibited from growth in other ways. The low-tech methods at your disposal include drying, smoking, curing, and brining. These methods can also be used in concert—meat/fish can be dried without curing, cured then smoked and dried, or cured and smoked without completely drying—you get the picture.

DRYING

Drying meat deprives potentially harmful bacteria of the water they need to function. Since flesh does not dry instantly, there will always be some level of incidental unwanted microbial activity, but when drying is done right, this activity will actually enhance the flavor and texture of the meat with no ill effects to the eater. Natural drying using sun and wind is best done in sunny, windy, and cold climates or seasons—see Food Preservation in the Wild (page 280) for more.

SMOKING

Smoking is another way of drying meat, often used in warm and humid climates where meat would spoil before it had a chance to dry out on its own naturally. Smoking is also used heavily pre-zpoc as a means of flavoring meats (see A Post-Apocalyptic Smoker’s Wood Guide, page 201). When meat is smoked, “the sugars in cellulose . . . break apart into many of the same molecules found in caramel with sweet, fruity, flowery, bready aromas,” says food scientist and author Harold McGee. But little do most backyard barbecuers know that smoking has an added benefit: It imparts antimicrobial and antioxidant properties to the meat, too. Smoke also slows the oxidation of fat, which is what causes dried meats to become rancid (and is why fat should be trimmed off meats before drying out completely; see Food Preservation in the Wild, page 280, for more).

DRY - CURING, OR SALTING

Dry-curing is the direct and heavy application of salt to meat or fish for preservation. The salt draws out moisture through osmosis and deprives harmful bacteria of water, as well as inhibiting the growth of certain bacteria and enzymes. Curing can be done for a short period before the meat is cooked, like with bacon. Or salted meats can be hung and aged for longer periods and then consumed raw, like with prosciutto. Curing can also often involve the use of sugar and other seasonings to help flavor the meat. It is best done in cool and dry climates or seasons, or in a cool subterranean root cellar kept at less than 50°F (see Building a Root Cellar, page 190) with a humidity in the 60%–65% range. If you live in a particularly warm climate or it is the summer, dry-curing is not a good way to preserve meat—the warm temperatures will cause the meat to spoil before the salt has penetrated enough to protect it.

The term “curing” often implies the use of curing salts like pink salt (sodium nitrite and nitrate). These curing salts kill harmful bacteria and help the meat maintain its red color, along with creating a more “meaty” flavor. Curing salts may be hard to come by during the undead uprising, and aren’t generally required for curing whole pieces of meat because the meat below the surface will be untouched by bacteria anyway. It’s much more often used in ground meat products, like sausage, where bacteria that was on the surface of meat is ground and mixed into the whole batch. When stuffed into casings, sausage provides a great environment for bacteria to thrive in: dark, moist, and full of food.

Curing is a closely related cousin of “salting,” and in fact the terms are often used synonymously, though “salting” more typically implies drying in conjunction with a long salt cure, as with salt cod and prosciutto. When salt is used as the primary means of preservation for long periods, foods generally become extremely salty and are best used sparingly in soups, stews, and sauces for flavoring or else soaked to remove excess salt before consuming (as with Everything’s Going to Be Salt Cod Korokke, page 225).

A general rule of thumb for dry-curing is to use 6% salt by weight of meat, so for a 10-pound piece of meat you would use 0.6 pound (about 10 oz. or 272 g) of salt. Rub the salt (and any other seasoning or flavor enhancers you might be using) directly onto the meat and put it into a nonreactive pan or container. Cover it well to keep out bugs and store in a cool place (below 50°F). Drain and flip it every few days until 15% of its weight has been lost (about 2 days per pound). Once you’ve hit that 15% mark, rinse off the cure and cook before consuming. Or you can age the meat further by rinsing off the salt, covering it in lard, and hanging it in a cool place wrapped in breathable fabric like cheesecloth for about 6 months or until it’s lost  of its original weight. At this point the meat can be enjoyed like a prosciutto, uncooked and thinly sliced.

of its original weight. At this point the meat can be enjoyed like a prosciutto, uncooked and thinly sliced.