Jack Benny’s most famous radio gag was first performed on March 28, 1948:

Jack is walking down a neighborhood street at night. We hear him softly humming and his shoes contentedly tapping down the sidewalk. (He’s carrying Ronald Colman’s Oscar statuette, which he has borrowed to take home to show to Rochester, but that’s another story. . . .)

Suddenly, a menacing male voice leaps out of the quiet, growling at Jack, “Hey buddy . . . this is a stick up! . . . Your money . . . or your life!”

Silence. All we hear is seconds of silence . . . and the nervous tittering of the studio audience. Silence, or “dead air” was a risky proposition in commercial network radio broadcasting. It may have given listeners the impression that someone was thinking, but it often left listeners falling into a void of ether nothingness and loosened the grip of the advertisers over their attention.

Breaking into the tense stillness, the robber repeats his demand, “Didn’t you hear me?! I said . . . Your money . . . or . . . your life!”

Again the silence, stretching, stretching, but this time accompanied by the growing laughter of the studio audience, chortling at the absurdity of Benny’s continuing delay, each second compounding the hilarious suspense. . . .

“I’m thinking it over!” Benny finally cries.

The studio audience exploded into roars of laughter, releasing a pent-up emotional response of relief and disbelief that swept across the auditorium. Their reaction was shared by millions of radio listeners in homes across the nation. Their beloved, fallible “Fall Guy” had faced a dire situation and responded in a hilarious, typically self-centered way. But this wasn’t simply a joke, and not quite a full comic routine; it was an exchange distilling an essential aspect of a continuing character, a moment that drew on more than fifteen years of writers’ and performer labor as well as fifteen years of audience familiarity with Jack’s infamously parsimonious character.

The “Your Money or Your Life” gag, so long in the making, was subsequently replayed by critics, fans and Benny himself for the rest of his radio and television career, and since then in every article discussing his lasting legacy in American entertainment. The genius of Jack Benny’s humor is that it rarely stemmed from jokes with standard set ups and punch lines. It stemmed from character, embedded in a narrative, in countless stories of a foolish man’s humiliation, enriched by the actors’ voices, tone, and timing, with radio comedy’s richness captivating the ears and imaginations of its listeners.

• • •

Radio was the most powerful and pervasive mass medium in United States from the late 1920s to the early 1950s, as its simple and inexpensive technological reach and its intense consolidation through commercial networks (NBC Red and Blue, CBS, Mutual) amplified the live messages of its most prominent speakers broadcast to an audience of unprecedented size. Thirty million or more Americans, gathered in small groups around receiving sets in their living rooms, stores, workplaces, and cars, simultaneously became a national audience. The charismatic political leaders, demagogues, crooners, and comics heard over the radio in this era had a tremendous impact on popular culture. Comedians were network radio’s most popular performers, and Jack Benny was the most successful of them all. His voice was as familiar to listeners as President Franklin Roosevelt’s. Jack Benny, in twenty-three years of weekly radio broadcasts, indelibly shaped American humor, and became one of the most influential entertainers of the twentieth century.

Born on Valentine’s Day, February 14, 1894, in Chicago, Benjamin Kubelsky was the eldest child of Eastern European Jewish immigrant Meyer Kubelsky and his wife Sara. Benny Kubelsky was raised in the gritty northern Illinois manufacturing town of Waukegan, where Meyer was a moderately successful saloon operator and then haberdasher. Benny and his younger sister Florence had comfortable childhoods, merging their small Jewish community with a diverse array of assimilated and ethnic cousins and schoolmates. He wanted to title his autobiography “I Always Had Shoes.”1 From an early age, his parents hoped he would become a renowned concert violinist; Benny Kubelsky was a reluctant student of either textbooks or rigorous music lessons, however, and by age sixteen he abandoned school and took a job playing fiddle in the pit orchestra of Waukegan’s Barrison Theater. Eventually he formed a duet with a local matronly pianist Cora Salisbury and started touring small-time Midwestern vaudeville, then partnered with young piano player Lyman Woods. World War I intervened, and Benny Kubelsky was drafted into the Navy. At the Great Lakes Training Center he took the comic stage role of a disorderly orderly in a camp production, and he found he enjoyed making people laugh. In the 1920s, he embarked on a vaudeville career, playing the violin much less and joking more often. Kubelsky encountered difficulty with his stage name, as his real name sounded too much like famous violinist Jan Kubelik. So he tried the moniker “Ben K. Benny,” but the more well-known violinist-comic-bandleader Ben Bernie objected. Thus Benny Kubelsky styled himself “Jack Benny.”2

As we will learn in subsequent chapters, Jack Benny became a moderately successful vaudeville solo comic performer in the 1920s, developing a style of breezy, informal, urban, but assimilated Anglo-type humor that drew from the suave “master of ceremonies” role model of star Frank Fay—but with self-deprecating tones that were all his own. In 1927 he married Sadye Marks, a twenty-one-year-old nonperformer he had met through the wife of a friend also playing the western vaudeville circuit. Soon Sadye was taking the occasional role of the flighty young flapper with whom Jack bantered in his stage routines. Benny appeared at the famed Palace Theater in New York, as the master of ceremonies in MGM’s first talkie film The Hollywood Revue of 1929, and on Broadway in the risqué show Earl Carroll’s Vanities. In the crunch of the Depression in 1932, with vaudeville and Broadway revues fading and film roles unsatisfactory, Jack Benny decided to try his hand at radio comedy.

Jack Benny’s radio show, as it developed over the years on the air between 1932 and 1955, commercially sponsored most famously by Jell-O gelatin mix and Lucky Strike cigarettes, was a half-hour weekly comedy variety program that featured a group of quirky comic characters, led by Jack, who put on a radio program. Jack engaged in repartee around the microphones with the bandleader, singer, and announcer, and with chief-heckler/companion Mary Livingstone (Sadye Marks, who soon adopted this professional name as her own). The cast eventually coalesced around key regulars—announcer Don Wilson who joined in 1934, bandleader Phil Harris (1936), and singers Kenny Baker (1937) and Dennis Day (1939). When not fulfilling their purported duties, they joined Jack in studio adventures (enacting movie parodies and murder mysteries and kidding the sponsor’s product). Other times their adventures occurred at Benny’s house (staffed beginning in 1938 by Eddie Anderson portraying Rochester, Jack’s impertinent valet) or out on the streets of Hollywood. The show’s narrative world in the post–World War II years included additions such as infuriating department store floorwalker Mr. Nelson, hapless violin teacher Professor Le Blanc, long-suffering movie star neighbors Ronald and Benita Colman, the race track tout, Benny’s underground money vault, and Jack’s ancient, wheezing Maxwell jalopy.

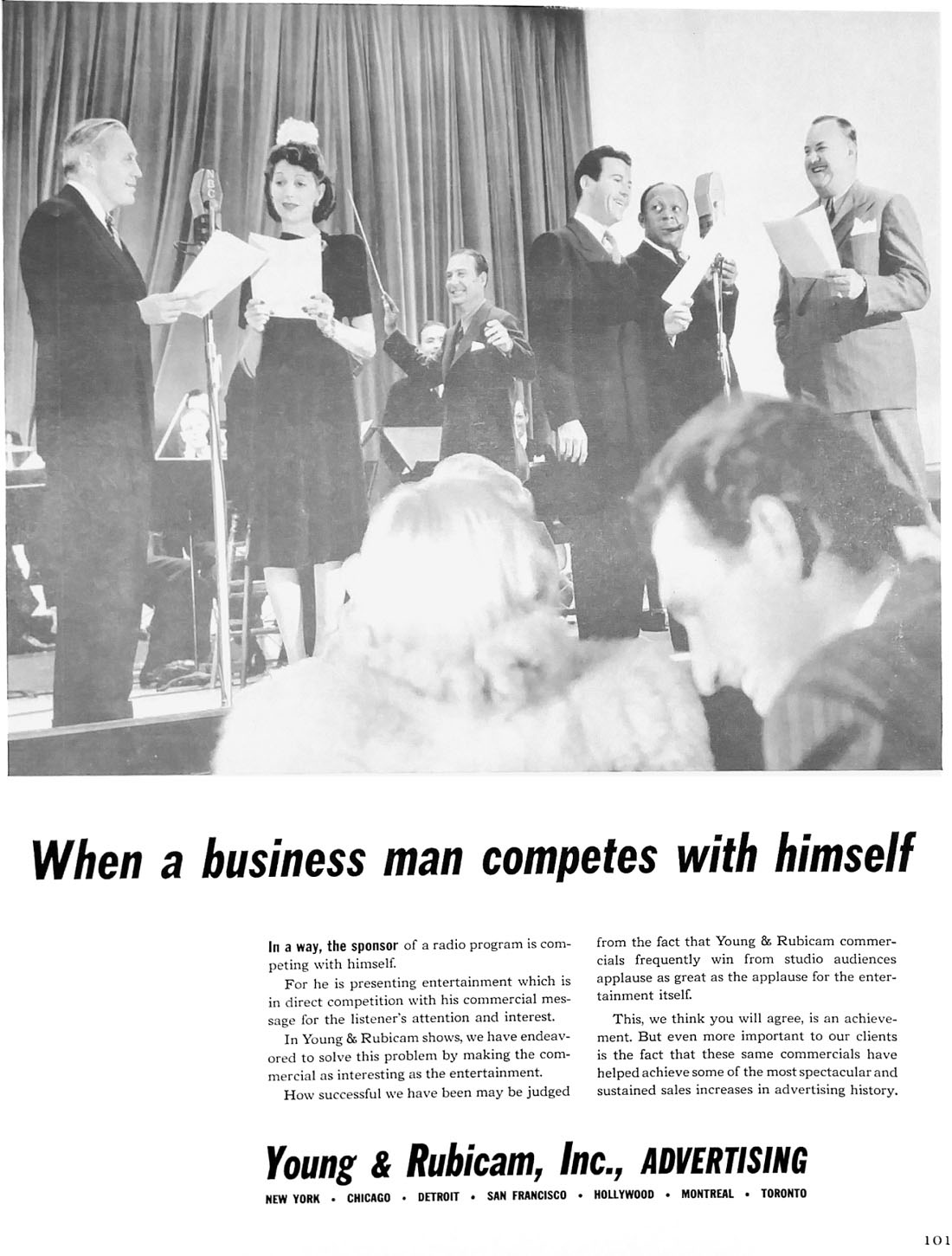

FIGURE 1. The ad agency for Jack Benny’s program during the Jell-O years, Young & Rubicam, touted to business leaders in ads like this the show’s outstanding ability to integrate commercials with comedy, winning both high ratings and increased product sales. Benny and cast members Mary Livingstone, Phil Harris, Dennis Day, Eddie Anderson, and Don Wilson are shown in mid-broadcast. Fortune, April 1939. Author’s collection.

The centerpiece of the comedy was vain, miserly “Fall Guy” Jack, whom his cast and his world constantly conspired to insult and frustrate. Jack Benny’s radio character suffered all the indignities of the powerless patriarch in modern society—fractious workplace family, battles with obnoxious sales clerks, guff from his butler, and the withering disrespect of his sponsor, every woman he met, and Hollywood society. As the years rolled by, Jack’s ever-more-absurd schemes to avoid spending money collapsed like his dignity, week after week, as his inflated ego was punctured by fate, abetted by his unruly radio cast.

Jack Benny was a comic genius, an absolute master of comic timing, an innovative creator, a dedicated craftsman, and a meticulous program producer. A canny entrepreneur, Benny became one of the pioneering “showrunner” producer/writer/performers in broadcasting history. His modern style of radio humor did much to spawn a wide variety of comedy formats and genres popular today. In vaudeville, he helped pioneer a kind of standup comedy that did not rely on props, costumes, gags, or circus-like physical slapstick. In radio, Benny and his writers pioneered the character-focused situation comedy, the genre that’s remained at the heart of television’s broadcast schedule. His informal monologues and easy repartee with comic assistant “stooges” were direct ancestors of the late night television talk show.

Benny skillfully leveraged vaudeville and broadcasting stardom across media forms into film and advertising prominence, and he innovated the “intermedia” integration of those rival industries into his radio show. He overcame difficult challenges thrown up by his sponsors to gain greater creative control of his program. His humorous commercials sardonically skewered American cultural foibles, slyly broke down listeners’ reluctance to purchase his sponsors’ products, and made his audiences actually enjoy listening to the advertising.

Benny and his writers utilized what radio historian Susan Douglas calls “linguistic slapstick,” incorporating layers of aural humor into the program to engage listeners’ imaginations.3 The Benny show created a narrative space of disordered gender roles, a world turned upside down where sharp-tongued women brashly wounded the inflated egos of middle-class men like Benny who were “unmanly,” cuckolded by their murderous wives in satirical sketches, disdained by Hollywood movie stars, and sneered at by supercilious department store clerks. Family audiences on Sunday evenings found that radio’s invisibility, the laughter shared with studio audiences, and the familiar characters of the sitcom format made even Benny’s most envelope-edge-pushing situations of gender blurring, racial integration, or racial stereotyping more acceptable fare when they might otherwise have been too controversial to depict visually. The socially conscious humor of Benny’s radio program intrinsically drew on what radio historian Michele Hilmes terms the “disruptions caused by a disembodied medium in an insistently embodied (raced, classed, gendered) world.”4

A caveat: Jack Benny, his writers, and the cast created their humor more than half a century ago, a time when cultural norms accepted vast amounts of racism, sexism, homophobia, and xenophobia. Benny’s radio humor was a product of its time and place and will be subject to critical examination throughout this study. But at the same time, Benny and his writers, despite all their failings and omissions, could also sometimes show a flexible acceptance of social and cultural difference, creating a space to disrupt these widely held attitudes toward race and gender, taking the side of the marginalized against traditional patriarchal culture.

Jack Benny guided his radio program through challenges and successes throughout the 1930s, through wartime malaise and postwar triumph of rejuvenated appeal. In this time he also appeared in a number of films and in 1940 was an unexpected box office star when teamed with his radio comic foil, Eddie Anderson. Benny also weathered the personal crisis of a widely publicized scandal over supposed jewelry smuggling that could have ended his career. During wartime, Benny embarked on summer adventures with USO tours to military camps near the front lines in Africa, Europe, and in the Pacific. But soon after revitalizing his radio show in 1946, television loomed on the horizon, and Benny struggled with sponsors, the limits of the new media, and exacting newspaper critics, in the process of adapting his aural humor to the visual, which he finally began in October 1950. Benny remained the top comedian in radio through 1955, by which time network audiences had completely dwindled. Well established in television by that point, Jack Benny continued his highly rated TV comedy show for a total of fifteen years, until it was cancelled in 1965. Benny spent his seventh decade busy with regular television specials, frequent performances in Las Vegas and Lake Tahoe, and with giving scores of charity symphony concerts to benefit musical organizations around the nation. Benny worked right up until his death from pancreatic cancer on December 25, 1974, and TV specials and newspaper headlines mourned the loss of a national treasure.

This is not meant to be a full biography of Jack Benny, but rather a multifaceted examination of his radio career, his greatest achievement. I use close analysis of the entertainment industry trade press, primary research sources, and original scripts and program broadcasts to explore the impacts of performer, media industry, texts, and audiences on each other, which created the cultural meaning of Benny’s radio program for midcentury America. It persists as classic comedy to entertain us today. I hope that this book encourages you to listen to the wealth of available Benny radio recordings. To that end, I have created a companion website (www.jackbennyradio.com) containing audio clips, original scripts, memorabilia, and further information on internet sources that explore Benny’s humor. Jack Benny’s radio comedy remains fresh today; its light-hearted, self-reflexive impertinence and sense of camaraderie invites us all to become part of Benny’s gang.

CONSTRUCTING COMEDY ON THE RADIO

As were Jack Benny’s earliest Canada Dry radio performances in May 1932, comedy over the airwaves could be produced as if it was just vaudeville with the lights turned off. Removing the physical comedy and visual cues to the audience, however, created major challenges for performers steeped in theatrical traditions, like Ed Wynn and Eddie Cantor, who had been dependent on creating reactions with their outlandish costumes and punching up their jokes with mugging and facial expressions, body movements, use of props, pratfalls, and other kinds of physical shtick.5

The radio comedian’s primary tool was his voice. “Rough or smooth, high or low, a good radio voice must have personality, with all the intangibles and seeming contradictions the word implies,” New York Times radio critic John Hutchens once commented. “At its best, it is really distinctive to the point where you would recognize it if you had not heard it for months or even years.”6 The comic’s voice needed to be clear and understandable as it passed through technologically limited microphones, out into the ether, and back in through tinny radio speakers, and to be heard over the static or reception difficulties in listeners’ living rooms.7 Franklin Roosevelt, like Jack Benny, had a radio kind of voice. Hutchens called FDR’s voice “warm and confidential, dignified but informal, unhurried; even though he reads his speeches, it seemed conversational, that he was talking to individuals.”8 Jack Benny’s Midwestern twang (which represented “honesty and common sense” to Hutchens) transferred well from vaudeville to the radio. He’d used relatively few visual cues on the stage, dressed in a tuxedo or modern suit, and moved smoothly and quietly, and his only props were a violin he rarely played and a cigar he rarely smoked.

Benny was widely acknowledged to have the best sense of comic timing in the radio industry, a concept he struggled to explain: “I talk very slowly and I talk like I am talking to you . . . I might hesitate . . . I might think. Everybody has a feeling . . . that I am addressing him or her individually.” His informal style often came across to the audience as if he was ad-libbing, when in fact, Benny and his cast were presenting scripted dialogue, carefully edited by Benny to have the best rhythm and flow.9

Benny and his first scriptwriter writer Harry Conn, like other early creators of radio humor, soon began moving from monologues to experimenting with the inventive possibilities listeners could bring to the production, and began to expand fictional spaces in which the show’s dialogue and sketches took place, helping their programs create what would become radio’s biggest asset as “theater of the mind.”10 Through vocal inflections, whispers, sobs, laughter, snideness, singing, or bellowing, talented radio actors could express a world of emotion, and could unleash the listener’s imagination. From the mid-1940s onward, Mel Blanc would voice scores of different human and animal characters on Benny’s program, even the sputtering engine of Benny’s decrepit Maxwell automobile.

With no visual cues to tell a crowded scene of actors apart, the number of people speaking in a radio sketch needed to be limited to no more than three or four speaking, and no two could sound too similar. In the early 1930s, Conn believed that ethnic American voices were inherently funny. Without the costumes to help create an immediately recognizable stereotype, Conn thought that ethnic comedians filling small roles on the Benny program should lay on the accents thickly. When Phil Harris joined the Benny program in fall 1936, his voice and Jack’s were said to sound too much alike, so Phil adopted a broad Southern accent for his on-air character. When Eddie Anderson joined the program the first time in 1937 in a role as a train porter, it was similarly because Benny and the writers sought an unusual voice.

New voices needed to be introduced by name, and names repeatedly mentioned to keep characters in the audience’s imagination. Benny’s radio show thus had a lot of identifying dialogue (“Say, Jack, I’m opening the door . . . What’s in your hand, Don? . . . Oh, here comes Mary”) that would have to be excised once the show moved to television. As Erik Barnouw discussed in his textbook on radio writing, when a person on the radio was not speaking for more than a few seconds, the audience would forget his or her presence. Barnouw complimented the Benny program for using Mary Livingstone’s voice to turn this liability into a humorous surprise, such as when Jack and another character would trade a long series of boastful comments, and then Mary would leap into the crescendo of the exchange with a sharp putdown.11

Radio writer Art Hanley’s guide to comedy writing for broadcasting instructed students to use dialogue to paint descriptive word pictures of settings and characters.12 “Keep all speeches short and to the point,” Hanley counseled, “Use action words, color words, natural words; mention specific places and tangibles such as the furniture in the room.13 The Benny program baldly violated some of Hanley’s cardinal rules, such as “Don’t write in bit parts of one or two lines for extra voices unless there’s very good reason. They tend to confuse the listener and complication the action.” Benny often spent up to $1,000 in salary just to have Frank Nelson suddenly pop into a scene to drive Jack crazy with a withering “Yeeeeeesssss?” Hanley, however, approved of another Benny program staple, the running gag, as a “short cut to effective comedy,” a bit repeated three or four times, “often enough to become familiar and excite humorous association and humorous anticipation at another hearing.”14

Hanley taught writers that on radio, a joke’s punch line must be placed at the end of a line, for fear that studio audience laughter would muddle or “walk over” what home listeners were able to hear.15 Managing talk and silence, and leaving time for audience laughter were major tasks in writing the Benny radio program. The program was performed live in front of studio audiences usually numbering 300–400 people. Studio audience laughter was a kind of currency for network comedy programs. Benny’s writers and ad agency program producers “graded” the strength and duration produced by each laugh during each episode.16 Sponsors demanded to hear as many laughs as possible on their programs, and annual renewals hung in the balance.17 Benny’s writers had to properly estimate the timing of the “spread,” the space left between actors’ jokes for audience laughter, usually two or three seconds. Extraordinarily big jokes might produce audience laughter of 6, 8, or 12 seconds (several extraordinary Benny studio audience laughs have been clocked at over 20 seconds).18 With live radio shows scripted down to the last second, failing to account for audience laughter could run afoul of the all-important closing commercial or make a show run overlong (both verboten, back in the day); it sent Benny’s writers and ad agency producers with slashing blue pencils to remove jokes to have the show end up on time.

Most radio comedians did not labor alone to create their own scripts (Fred Allen being a famous exception). Jack Benny needed writers to craft the enormous amount of new material required for each week’s program, up to thirty-nine episodes per season. While Benny wasn’t a quick comic writer, he made tremendous contributions to the show as one of the keenest and most obsessive script editors in the business, as a 1945 magazine article noted:

There is one area in which Benny feels confident and secure. He knows better than any other man in the world what will be funny on the Jack Benny program. More exactly, he knows what will NOT be funny. “I can’t always tell when a line is good,” he says, “but brother, I can tell when it’s lousy.” By the slow and painful process of eliminating the lousy, Benny builds a good script. . . . Perfectionist Benny will work for half an hour over a single line, polishing it as lovingly as a poet would a couplet. He knows the speech rhythms of all his players and reshapes each line to fit these idiosyncrasies.19

Hanley cautioned the comedy writer of performers, “You supply the meat, he the dressing.” Writers’ material could only be as funny as the actors who performed their lines. A radio actor needed a spontaneous ability to “read around” the dialogue, giving a loose reading to the line to make it sound like idle patter. Hanley warned that a poor performer could “muff your lines, pace his reading badly, hog the spotlight when he doesn’t belong, throw in ad-libs that don’t fit, stop being funny and jump laughs” noting that it was imperative that actors have the patience to wait for the studio audience’s laugh, but then to be able to jump in quickly with topper gags.20

Radio comedians and their writers crafted “linguistic slapstick” to produce humor over the air that paralleled the raucous physical and visual shenanigans with which their film compatriots entertained movie audiences.21 The easiest and most direct way to play with language was with puns, simple wordplay drawing its humor from the incongruity of mixing up similar sounding words with different meanings. While humor theorists consider puns the lowest form of humor, the more unexpected or incongruous a pun was, while slyly making a new kind of sense out of nonsense, the more surprisingly humorous a pun could be. The “rule of threes” helped structure jokes and exchanges; the first two attempts to do something straightforwardly set up a pattern that the unusual occurrence the third time comically destroyed.22 Other humor tailor-made for radio was funny-sounding words.23 Humorists note that the sound of the letter K in all its permutations, and B, D, G, P, and T make words sound amusing, while others have suggested sprinkling specific, colorful words into jokes to make them punchier and more memorable.24

Benny and his writers were able to create seemingly endless streams of humor, not by reworking stock gags from joke books, but by creating characters with odd traits and quirky personalities who made their comedy by interacting with each other. The comic persona of “Jack,” honed over the first years of the show, was the tent pole of the show’s humor. A 1938 Scribner’s article claimed Jack was

a character aimed dead-center at the universal tendency to howl at the self-confident man who makes a fool of himself. Jack isn’t the wise guy who tells all the jokes on his show nor the brightie [sic] who has all the funny lines. He’s on the other end of the gun. He is the target of most of the jokes, most of the comic situations. You laugh at him, but you also sympathize with him because, almost inevitably, his best-laid plans blow up in his face. He’s the pleasant oaf, strutting down the street, superbly sure that he’s making a tremendous impression. When he steps on a banana peel, and lands on his backside, you guffaw at him, but you pity him a little, too.25

Humor theorists have found incongruity to be the basis of most comedy—audiences laugh at things that do not fit logical patterns, that are exaggerated, absurd, out of place, and which cross up our expectations. Henri Bergson found humor in the incongruity of people acting like machines, being too literal minded to bend with the flexibility life demands. Sigmund Freud found underlying subconscious desires about sex, death, and humiliation at work in jokes. Thomas Hobbes was especially interested in the laughter of the sudden superiority of a victor over a foe.26 Pomposity brought down to the common level through pratfalls or insults is always funny, as have been the endless battles between supposedly loving husbands and wives. Yet for all the incongruities, insults, and humiliations that the Jack Benny character faced, for him and his cast-mates to remain popular with audiences the comedy managed also to include sympathetic aspects for the characters to remain beloved by fans. Benny’s radio program ultimately balanced insults and sympathy, disdain for Jack and everyone’s feeling of superiority to him, with a lasting, familiar connection.

FIGURE 2. Jack Benny, and radio fan magazines, came to prominence together. He and his co-star Mary Livingstone (his chief heckler on radio and wife in real life) were frequently promoted in publications geared to the growing number of fans, who sought to learn about their personal lives as well—such as news about the Benny’s adopted daughter Joan. Radio Mirror, April 1935. Author’s collection.

Benny’s favorite comic writer, Stephen Leacock, a Canadian humorist and economics professor at McGill University,27 outlined a progression of humor that moved from the simple slapstick of children and delight in physical incongruities and play, to the word-play of puns, through jokes, parody, and satire, to what he considered the deeper level of humor, the development of comic characters. The highest form of humor, he thought, past puns and jokes and incongruity and vivid characters, “is the incongruity of life itself, the contrast between the fretting cares and the petty sorrows of the day and the long mystery of tomorrow. Here laughter and tears become one, and humor becomes the contemplation and interpretation of our life.”28 Benny’s comedy took this to heart, in the way that the sixteen-year development of Jack’s “schmo” character on radio could lead him to debate how to face a question like “Your money or your life?” Leacock, like Benny, found that, ultimately, humor is about life itself, “from the angers and troubles of childhood to the fates and follies of all mankind.”29

SOURCES

To begin my exploration of Jack Benny’s broadcasting comedy and career, I started with the radio programs. Benny performed 922 half-hour episodes live over the airwaves between 1932 and 1955. Absence of recordings and lack of access to them has always been the greatest challenge to American radio scholarship. Listeners interested in Jack Benny are fortunate, in that approximately 750 full or partial recordings of Benny’s programs exist. In the past, it was an onerous task to find, collect, or listen to those nearly 400 hours of shows, an endeavor that involved great expense or many years of trading tapes with other fans or searching for nostalgic broadcasts of “Old Time Radio” (OTR) programs. Today, digital recording technology and internet availability are revolutionizing public access to old broadcasts, and Benny’s radio programs can be inexpensively purchased on CDs and DVDs, and accessed freely through websites like www.archive.org and the International Jack Benny Fan Club, www.jackbenny.org, and can be listened to through a wide variety of electronic devices. With access to so many episodes, choosing only a few to study could not fully reveal the insights into character development and construction of humor of Benny’s show as it evolved over twenty-three years on the air, so I have listened to them all, repeatedly, over several years while on long cross-country car trips or daily commutes.

Original program scripts provide additional insight, and all of Benny’s scripts exist in university archives, although they are usually only “as broadcast” copies. Few preliminary drafts of Benny’s weekly radio script treatments survive for us to trace the writers’ and editors’ work as each episode was constructed. Some of Benny’s own working copies of his final scripts, however, reveal his editorial efforts, as they contain extratextual markings. Benny polished the dialogue and language of his lines up to the moment of broadcast, to perfect the timing, emphasis, and laugh-getting potential of each line.

Benny donated a nearly complete set of his radio program scripts to UCLA. This collection also includes scripts for the approximately 170 episodes (broadcast 1932–1936) for which there are no recordings. Reading these early scripts, unheard for over eighty years, unveiled the process of experimentation, trial, and error that Benny and scriptwriter Harry Conn used in constructing the comedic form of the program and developing the program’s characters. Other partial collections are housed at the American Heritage Center and the Library of Congress. Lucky Strike–era radio and TV scripts are available in digital form at www.tobaccodocuments.com.

Following Jack Benny’s career in the entertainment trade press enabled me to better understand Benny’s role as radio producer and intermedia performer who moved across the rival media forms of vaudeville, film, and broadcasting. The ability to search articles and reviews in digitized versions of Variety, Billboard, Sponsor, and other publications at www.mediahistoryproject.org shed light on the challenges and problems Benny faced throughout his show business career. Regrettably, Benny’s archives contain almost no correspondence with radio network executives, sponsors, or the advertising agency workers who actually co-produced Benny’s programs. The details of contract negotiations, fan mail, complaints from the public, negotiations with NBC and CBS’s Continuity Acceptance departments over script details, and the entries to the “Why I Can’t Stand Jack Benny” contest all are long gone. The NBC papers at the Wisconsin State Historical Society and Library of Congress contain some scattered but very intriguing examples from early in Benny’s radio career of how network executives developed program formats, were involved in hiring performers, and had to run interference between anxious, demanding, interfering sponsors and anxious, demanding, interfering talent.

Jack Benny and Mary Livingstone assembled an extensive series of personal scrapbooks and clippings files containing reviews and articles published in newspapers, magazines, and fan periodicals throughout their careers. Benny’s scrapbooks are housed at the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming. They offer fascinating insight into what material evidence Jack and Mary sought to preserve and remember about their careers, including both favorable and unfavorable theatrical notices and reviews. While Eddie Anderson did not leave archival materials behind, the African American press frequently discussed Anderson’s career and role as Rochester. Material culled from these historical newspapers greatly increased my understanding of the support and criticism he faced in both the black and white communities in the 1930s and 1940s.

Resources at the Margaret Herrick Library of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences gave me insights into how the light musical/variety films in which Benny appeared in the 1930s and 1940s proceeded through the Production Code’s vetting. Director Mark Sandrich’s scrapbooks invaluably documented the production and promotion of Benny’s three most radio-flavored films (and huge box office successes) at Paramount in the 1939–1941 period. Studio advertising press books for the films demonstrated how the studio bumbled its way through creating intermedia links to promote the films to the American public.

My project benefits from the work of many scholars writing about radio broadcasting history, comedy, celebrity studies, gender and racial identity, cultural history, and media industry studies, which I will address in the following chapters. I am grateful that several biographical accounts were published in the years after Benny’s death by his manager Irving Fein, scriptwriter Milt Josefsberg, and wife Mary Livingstone. In 1990 Joan Benny published a wonderful volume that combined her own memories with an autobiographical account written by her father in the 1960s.30 The full flowering of research into American radio history, examining entwined development of the industry, its creators, programs, technology, audiences, and cultural impact, began with the outstanding analysis of Michele Hilmes in Radio Voices (1997) and Susan Douglas in Listening In (1999). Both see Benny as a defining figure representing some of the highest achievements in the history of American commercial network radio. Their critical insights have set high standards for scholars to build on, as the fields of twentieth-century media industry studies and broadcasting history and sound studies have continued to expand.

THE CHAPTERS

The first half of this book takes a cultural history approach to the origination of Jack Benny’s radio comedy, examining how Jack Benny and his writers developed comic characters for himself, Mary Livingstone, and Rochester, and continuing, flexible narratives through a process of trial and error. The first chapter explores how Jack Benny adapted his vaudeville style of humor, as a self-deprecating, Midwestern-flavored “Broadway Romeo,” to radio, beginning in May 1932. Discovering that live weekly broadcasting was a ferocious devourer of new material, Benny hurriedly hired vaudeville gagster Harry Conn to write the program with him. Partners Benny and Conn began expanding the narrative possibilities of the radio format from monologues to dialogues, which pulled in the bandleader, announcer, and singer; they opened out the narrative world of the show by having speakers figuratively move away from the microphone to fictional adventures. Benny and Conn developed a program that was refreshingly self-referential, with the cast blending fiction and reality by performing as a group of workers putting on a radio show. They irreverently broke the fourth wall of theatrical performance, acknowledging their audiences and making fun of the advertisements and their roles on the program. Most significantly, in 1934 they reshaped Jack’s character to become an increasingly more fallible character, the “Fall Guy,” the butt of everyone’s jokes. Jack became egotistical and vain, penurious and mistake-prone. Constantly making social faux pas, he became more frequently criticized, humbled, and insulted by his cast of radio show employees. Tensions in Benny and Conn’s creative partnership over how they shared authorship boiled over in March 1936. Conn quit and struggled to find success, while Benny hired new writers who helped him take his show, now sponsored by Jell-O, to new heights of popularity.

The second chapter examines the strength of the “Unruly Woman” comic voice on the Benny program, in the character of Mary Livingstone (Benny’s off-stage wife Sadye Marks). Mary’s character exhibited an extraordinary level of independence and biting wit that made her the equal of strong-willed Hollywood film heroines. In her initial appearances on the radio program in 1932, Mary began as an addlepated girl, but her character soon combined the genial nonsense of a Gracie Allen with sharper, mocking tones. In satirical skits, Mary adopted an imitation of Mae West (which eventually morphed into a “tough girl” voice) to represent a confident sexuality. Using her distinctive laughter to leap into conversations and disrupt Jack’s egotistical pretensions, Mary became an impertinent, sharp-tongued companion and chief heckler who joined by the other brash waitresses and steamroller-driving mothers who emerged victorious in the show’s battle of the sexes.

Chapter Three explores how, over twenty-five years, Benny’s radio character played with the construction of gender identity, questioning rigid ideas about heterosexual masculinity that punctured the pretensions of patriarchal culture. Jack enacted a variety of masculinities from demanding boss, to the boisterous rivalry of the Benny Allen feud, to the unmanly character mocked for his vanity, his age, his toupees, his cheapness, and especially his lack of sexual prowess, to dead-fish-kissing asexuality, to queerness. Jack’s masculine Jewish identity was also expressed with subtlety. The ways in which critics interpreted Benny’s slippery character kept changing during the shifting cultural climates of the Depression, wartime, and postwar years, while Jack’s playful gender blurring remained much the same. Benny played the cross-dressing lead role in a 1941 film version of Charley’s Aunt, and critics found the source of its humor in the titillation of the sharp boundaries of male and female being crossed in slapstick manner. Benny incorporated skits about donning his Charley’s Aunt costume to dance with soldiers into his wartime-era radio programs, inviting laughter that mingled titillation with confusion. In the late 1940s Benny devised a skit with George Burns in which he impersonated Gracie Allen, with uncanny accuracy of dress and performance. When Benny showcased his Gracie routine in TV episodes in 1952 and 1954, loud critical reaction showed the power of visuality and growing tensions in American culture over appropriate gendered behavior and fear of alternative sexual expression.

Chapters Four and Five discuss the career of Eddie Anderson, whose success was deeply entwined with and dependent on Benny’s. Anderson performed the role of Jack’s African American valet Rochester Van Jones on the radio program from 1938 to 1955 (and would continue on television). As the most frequently featured black actor in American radio, film, and TV, Anderson’s radio and film career (neglected by media historians) provides a notable case study of the struggles and achievements of an African American performer moving between media industries in the first half of the twentieth century. Rochester’s character was central to the construction of race on American radio. Made “safe” for white audiences to enjoy because of his servant role, Anderson as Rochester entered millions of homes every week. Although Rochester was an intelligent, sassy butler, Benny’s writers often saddled the character with racist stereotypes, enabling many radio reviewers to describe him as shiftless, superstitious, and content with low pay and a tyrannical boss. The radio show was obsessed with making references to his black skin, emphasizing his difference yet uniqueness.

Audiences in the black community struggled with Anderson’s identity as a famous radio celebrity, some delighted and proud to see an African American become so prominent in mainstream white network radio. Anderson’s 1940 surprise success in several movies co-starring with Benny brought even more renown. During the racial tensions of World War II, more African American critics began to speak out against the crushing limitations of servant roles on the expression of a more complex black culture. Eddie Anderson as Rochester found himself very much caught in the middle—between widespread success, then growing racist backlash from conservative whites on the one hand, and growing disdain from black liberal critics on the other. Debates in the African American press and film and radio trade journals chart Anderson’s story from the peak of his mainstream stardom in white culture early during World War II, to the resistance and criticism he and his character increasingly faced as wartime optimism and ideals of racial integration into popular film and society started drawing backlash from both white and black critics. From the mid-1940s into the 1950s, Rochester became Benny’s most constant companion. Increasingly, however, the tensions of the civil rights movement complicated Rochester’s position, as Anderson faced hostile responses not only from racist Southern whites for his “too-familiar” film roles but also increasing criticism from the black community.

The second half of the book analyzes the continuing development of Jack Benny’s radio show from the perspectives of media industry studies. Chapter Six examines Benny’s achievements as a canny creator of advertising messages and media producer. It explores his battles with sponsors over creative control of his program, and his famous integration of sponsors’ products into his comedy, from conservative Canada Dry in 1932, to Jell-O (too successful, forcing the sponsor to end it), to Lucky Strike in 1944 (the most hucksterish of all sponsors, feared in the advertising industry and loathed by cultural critics). Benny brilliantly sent up his sponsors’ products with ironically humorous commercials that turned the commodities into absurdities and soothed the incursions of consumer culture into listeners’ everyday lives.

Chapter Seven argues that Jack Benny was among the most innovative and successful intermedia performers in mid-twentieth-century American entertainment. He conquered not only radio but also film, advertising, and live performance, simultaneously. Despite Hollywood’s disdain for radio, and numerous barriers to collaboration and integration of separate media, Jack Benny (like Bing Crosby and Bob Hope) succeeded in the strategic intermedia incorporation of elements of radio, film, and sponsor’s products into his live broadcasting performances. Benny’s publicity helped make Los Angeles the capital of American radio production, and promoted Southern California as a tourist destination. His innovative incorporation of parodies of popular films helped domesticate the brittle glamour of Hollywood films and stars and entwine the two media in listeners’ minds. Several of Benny’s popular radio-themed Hollywood movies, produced from 1939 to 1942, pushed intermedia collaboration at the box office, but stirred up a hornet’s nest of criticism from appalled New York film critics, who complained (just as would TV critics a decade later) that radio’s focus on aural humor compromised the cinematic form.

Chapter Eight examines Benny’s wartime creative crisis and the role he played in radio broadcasting’s larger postwar aesthetic turmoil. Starting in 1945, a new generation of outspoken newspaper and magazine journalists including John Crosby, Jack Gould, and Gilbert Seldes and others began to blast critical commentary at the inadequacies of radio programming, laying much of the blame for radio’s stultifying sameness on the comedians—from the bland staleness of their formats to their overdependence on corrosive insult humor, to the conservative domination of sponsors over the weekly schedule. Their favorite target for scorn was Jack Benny, as the quintessential symbol of the American system of commercial broadcasting. The critics’ invective stung, but also spurred Benny and his writers to develop innovations in characters, situations, and themes, reclaiming the ratings leadership and earning acclaim of those who call the postwar years Benny’s “golden era” of radio humor, all of this occurring in the shadow of coming changes in broadcasting.

Chapter Nine analyzes how Benny struggled to meet the creative challenges that television brought to his career. While Milton Berle’s fame in the new medium skyrocketed in 1948–1949, Benny was initially quite reluctant to make the leap. TV critics’ insistence on a new visually oriented comedy confused and discomfited Benny, who hesitated to move his fantastical comedy elements such as the subterranean vault and wheezing Maxwell, which depended for their humor on the listener’s imagination, to the new medium. Through trial and error and in the face of criticism from TV reviewers, Benny eventually followed his own path of adaptation to television. He reduced some favorite radio routines but blended in aspects of his old vaudeville act, and especially found new ways to connect directly with television audiences, as he moved from occasional video appearances in 1950–1951 to a regular TV schedule and the eventual ending of his radio series in 1955. The book concludes by considering the legacy of aural humor and radio themes that remained interwoven into Benny’s television performances.