HOWARD W. BUFFETT

Large-scale, complex challenges facing society cannot be solved by organizations acting alone. When groups decide to work together, using the best process is critical.1 How organizations develop comprehensive partnership strategies is just as important as their willingness to engage in work with others.2 When companies in the private sector partner, collaborative arrangements are straightforward and use well-established legal structures and precedents. Companies may align their activities through acquisitions or mergers, joint ventures, product or service contracts, and so on.3 In most cases, private sector organizations collaborate to attain higher returns on equity by improving operating efficiency and reducing either short-term or long-term costs.4 Such improvements may be seen directly in ways that are reflected on the balance sheet, or indirectly through factors such as customer satisfaction and loyalty, strategic planning, or workforce retention.

When businesses partner or consolidate, they can draw from their comparative strengths. Partnering businesses are usually governed by similar laws, operate under similar principles, and focus on creating value for similar stakeholders—a parent company, private owners, or shareholders. Effective private sector partnerships align the objectives of top-level strategy and capital allocation with the operations of subsidiaries or business divisions, as well as with the interests of shareholders. But how does collaboration work when addressing more complex, societal challenges where the alignment of activities or the compatibility of private and public interests may be less straightforward?5

In the cases of Digital India and Apollo Telemedicine, the makeup and delivery of programs evolved and expanded over time. The government of India allocated capital through investment in training and infrastructure, and it established high-level goals for the country. Private sector partner Apollo Telemedicine focused on medical service delivery through a geographically diverse network of Common Service Centers (CSCs) funded by the government. The CSCs were staffed by local Village Level Entrepreneurs (VLEs) who shared in fees for services that were affordable for low-income residents in the community. Those residents—stakeholders in their government—received access to critical human services, including basic health care. This mutually collaborative partnering process, based on distributed operations, enabled the program to expand to more than 60,000 community-level CSCs fairly quickly, and eventually led to more than 160 new, major eUrban Primary Health Centers.6

This process for partnering describes the India case in general terms. However, the observations and lessons herein apply to cross-sector partnerships quite broadly, particularly when those partnerships include a diverse array of participants. Funders or investors in these partnerships provide financial capital, implementers or operators carry out partnership activities, and stakeholders or shareholders provide principled direction and guidance for the partnership and receive benefits from its outcomes.7

When organizations from the public, private, and philanthropic sectors decide to collaborate, not only will legal structures and operating principles differ but so, too, might each group’s end goals, interim objectives, or stakeholder interests.8 My grandfather observed yet another important differentiating factor. In a letter he wrote to Bill and Melinda Gates, he said that “success in philanthropy is measured differently from success in business or government.”9 This difference defines a key challenge in developing effective cross-sector partnerships: how you measure success is based on how you define it. Organizations from across sectors define success using different terminology, develop different planning procedures to work toward success, and deploy different methods for delivering organizational or operational strategies to achieve success.10

This chapter discusses how potential partners can overcome these differences, especially when considering the needs and interests of the public good. It begins by outlining a formal definition of what it means to enter a cross-sector partnership, and the key characteristics and advantages of doing so. Next it examines the primary function of a partnership, the three main partnering roles, and how a partnership can be modeled. Finally, it addresses the issue of comprehensive strategy development through two analogous tools: a theory of change process for planning at a program level and a value chain analysis for identifying gaps and weaknesses at a system level. Each of these aspects is an important early step toward building a partnership of diverse yet complementary organizations working in alignment.

DEFINING A CROSS-SECTOR PARTNERSHIP

In recent years, partnership has become an expansive term with a wide range of interpretations.11 In some cases the word carries legal implications, such as when each partner “contributes money, property, labor or skill, and expects to share in the profits and losses of [a] business.”12 An example of this is a joint venture.13 In other cases, groups may use the term more informally when they announce a political alliance, are awarded a services contract, or receive a grant. This lack of consistency and formality creates challenges at the very start of partnership development, particularly when two very different organizations try to collaborate—such as a global for-profit technology company and a local, community-based nonprofit human services provider.14 So what do we mean by a cross-sector partnership?

Fundamentally, a cross-sector partnership is a collaborative working relationship between two or more entities, and in our examples these entities span two or more sectors.15 Our work and research is concerned with significant or complex challenges facing society, so many of the cross-sector partnerships described here are led by public or philanthropic organizations, or serve to benefit the public good. Our definition of a cross-sector partnership arises from the belief that many of society’s challenges cannot be addressed by any single sector or organization alone; coordinated action is required to achieve collective, positive social impact.16

Given this context, we define a cross-sector partnership as a voluntary collaboration between organizations from two or more sectors that leverage their respective teams and resources to achieve mutually agreed-upon and measurable goals.17 This definition is as much a mind-set as it is a process, and it requires further clarification.

■ By voluntary, we mean that partnering organizations enter the collaboration by choice (not as a result of punitive or compulsory action). Partners often begin with clear agreements that guide the development of their engagement. Some partners may prefer nonbinding documents, particularly in the early stages of cooperation.18 That said, most cross-sector collaborations are governed by a formal structure, such as a letter of intent (LOI). Others may use a memorandum of understanding (MOU) for general terms, or a memorandum of agreement (MOA) to spell out activities and resource sharing.19 Later, this chapter outlines seven partnership models that illustrate possible structures for collaborative engagements.

■ By collaboration, we mean the engagement goes beyond straightforward fee-for-service or product procurement between organizations.20 Unlike traditional contracting or PPPs, collaborative, cross-sector partnerships involve multiple types of partners in the design, planning, and progression of the overall effort.21 Partner roles and functions are well defined, as discussed in this chapter, and the partnership strategy is developed jointly across teams (using tools such as a theory of change and value-chain analysis outlined later).

■ By teams, we mean the collective knowledge and leadership experience of the people operating the organizations in the collaboration. Teams in a cross-sector partnership represent their organization’s distinct perspectives and resources. Furthermore, teams are responsible for advancing their organization’s objectives and maintaining progress while also accomplishing the partnership’s goals. Leaders across teams contribute critical skills-based capital (see chapter 6) that complements other resources invested toward shared outcomes.22

■ By resources, we mean a broad range of different types of assets or capital. This can include a coinvestment in a portfolio of blended financial capital (see chapter 10). Or, this can include access to physical assets, infrastructure, intellectual property, technology, or natural or environmental resources.23 Alternatively, coinvested resources may include important, yet intangible contributions that create intrinsic value for participants or that advance the partnership’s goals.

■ By mutually agreed-upon goals, we mean that partners and stakeholders work together to develop and prioritize specific objectives, milestones, and the long-term desired impact of the collaboration. Together, these groups determine individual and shared responsibilities within the overall scope of the partnership.24 They also codevelop time lines and priorities for resource allocation based on common terms and operating standards (see chapter 8).

■ By measurable, we mean that partners are able to discretely define success using clear and relevant metrics tied directly to their mutually agreed-upon goals. Specific objectives may vary significantly when organizations from different sectors are partnering. Therefore, the partnership will require a consistent, yet flexible methodology to outline and measure the performance of its collaborative programs.25 We recommend using a customizable approach that combines quantitative and qualitative measures into the analysis (such as the Impact Rate of Return methodology described in chapter 12).

The more a partnership meets or exceeds the various aspects of this definition, and the preconditions outlined throughout the book, the better positioned its participating organizations will be for success. Other definitions of similar types of partnerships vary,26 but they typically share overlapping terms or provisions.27 Terminology aside, engagements under the social value investing cross-sector partnership rubric exhibit a number of important characteristics:28

■ They are based on the convergence of interests between the partners that advance the objectives of each respective organization. These interests must be clear, fair, well thought out, and can be amended as needed;29

■ They share both risk and potential reward for all partners through the mutual investment of various types of resources. Thoroughly planning on, agreeing to, and coordinating shared investment throughout the collaboration helps reduce potential conflict between partners;30 and,

■ They rely on leveraging partner skills and assets, producing outcomes with higher measureable impact than could be achieved independently. This requires an up-front evaluation of each partner’s strengths and weaknesses, as well as key resource constraints.31

ADVANTAGES OF PARTNERING

We believe that partnerships following this definition and exhibiting these characteristics will enjoy distinct advantages.32 Such partnerships can produce significant collaborative value for all participants.33

1. These partnerships enable participating organizations to accomplish more than they could on their own.34

By combining efforts, partners can leverage their respective resources. From a financial perspective, this aspect of partnering appeals to organizations confronting budget deficits, government sequesters, or volatile market fluctuations. Partners also benefit by gaining access to others’ physical assets (such as meeting space), intellectual property, or the ability to share information widely across social groups. In the Digital India case, for example, the government had legal authority and national scope, private companies had technology and expertise, and community entrepreneurs provided local places of access for potential Aadhaar enrollees spread across the Indian subcontinent.

2. These partnerships enable participating organizations to build on each other’s expertise.35

Organizations in a partnership benefit from the core competencies and unique capabilities of each other’s teams. This provides partners with access to leadership skills and knowledge they may not otherwise possess. Partners can build off each other’s experiences operating specific types of programs or delivering particular services, share past lessons learned, and avoid repeating the mistakes of others. In the case of Apollo Telemedicine, Apollo had medical staff with specialized expertise as well as technological experience operating the delivery platform. The government had administrative systems and staff in place who were well equipped to handle the partnership’s financial resources and to help operate the initiative’s local clinics and multiservices centers.

3. These partnerships enable organizations to draw from cooperative and coordinated activity.36

By bringing together new coalitions of public and private actors through an interactive process, partnerships can generate activities with a wider reach and larger scale than any single organization can alone. This especially matters when accomplishing the partnership’s goals depends on the cooperative action of multiple partners across wide geographic areas or between diverse communities. This was apparent in the success of both the Digital India and Apollo Telemedicine cases in which numerous decentralized teams carried out similar programs throughout the country.

4. These partnerships can drive improved performance for each organization.37

Partners must agree on specific and clear milestones. Coordinated activities should draw on the comparative strengths of each partner and focus on tracking and advancing progress. For example, aligning activities with external stakeholders who are more agile can improve the speed of accomplishing shared objectives, especially if partners work in harmony toward the same milestones. In other cases, some partners may be able to advance common goals because they are governed under less burdensome rules or regulations. In the case of Digital India, Prime Minister Modi established aggressive time lines and ambitious goals that the government would have been unable to meet on its own. He also used his “bully pulpit” to encourage all members of the partnership to work together, to make progress quickly, and to provide mutual accountability.

5. These partnerships benefit by including a broad range of diverse actors.38

Partnerships that prioritize diverse and inclusive participation in their program design and deployment are more likely to result in long-lasting outcomes. Collaborative planning creates opportunities for individuals, communities, and small- and medium-sized organizations to participate in larger-scale problem solving. Stakeholder inclusion opens access to critical domain specific information and important cultural nuances that otherwise may be inaccessible to other partners.

In both cases, Digital India and Apollo Telemedicine needed the participation of a wide variety of organizations and communities to succeed. The large, nationwide federal government and partners in the private sector provided highly sophisticated technology and administrative services but designed their programs to meet the needs of both big cities and rural villages across the country. The VLEs in the Apollo Telemedicine example acted as an important linkage between their communities and the CSCs, thereby providing local context for program outreach and delivery.

These features apply in many settings beyond the ones discussed in India, as you will see throughout the book. Cross-sector partnerships come in all shapes and sizes, but these five core advantages are seen across each of our examples.

THE PRIMARY FUNCTIONS OF A PARTNERSHIP

With common definitions established, and an outcome-oriented process in place for organizations to chart their intended goals, partners must identify the “bottom line” objectives driving their motivations for partnering. Three core functions serve as a baseline for establishing a common understanding of what organizations hope to achieve through the partnership process:39

Coordination of resources. Partnerships often form so organizations can combine or leverage resources. One organization may have a resource that another organization does not and cannot easily acquire, such as unrestricted funding, technology, expertise, or distribution networks. By coordinating efforts, partners draw on key sources of capital from each other and benefit from their comparative advantages as part of a coordinated partnership plan.40

Enhancement of visibility or reputation. Some organizations partner for the explicit purpose of raising their public profile or that of their cause. The actual partnership may focus on charity, education, or community development, for example, but a primary purpose relates to the visibility or perception of a brand, group, or specific social outcome.41

Shared policy goals. Organizations across sectors work toward specific policy objectives; this can mean more government funding, reduced reporting burdens, creation of behavioral incentives, elimination of taxes or penalties, and so on.42 Policy agendas are relevant to every organization, whether they act on them or not. Agendas may include maintaining a status quo, increasing a policy oversight or available funding, or decreasing a policy or program restriction.43

THE PRIMARY ROLES WITHIN A PARTNERSHIP

To carry out these functions, organizations within a partnership typically take on one of three roles. Funders are donors or investors who finance the activities of the partnership or the capital expenditures. Implementers or operators carry out or manage the activities and programs of the partnership. Stakeholders are those who receive a benefit from or who have a highly vested interest in the partnership’s outcomes. Stakeholder groups often include communities at a local scale where the partnership’s investment of resources is focused.

Funders

Funders may be foundations (family, corporate, community, or operating foundations), governments (local, state, or national), bilateral organizations, multilateral organizations (such as the United Nations), corporations and other private sector actors (ranging from multinational companies and global financial institutions to venture capitalists and entrepreneurs), university endowments, pension funds, or sovereign wealth funds.44

In the Apollo partnership in India, the country’s government acted in the role of funder, and it facilitated program oversight, delivery, and some financing through its network of Common Service Centers. In this instance, the CSCs acted as a bridge between the funder and the implementation partner, which is common in larger or more complex cross-sector partnerships—particularly ones that span a broad geographic region.

Implementers

Implementers are typically contractors, nonprofit nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), academic institutions, external advisors or experts, faith-based organizations, or other private or government-funded aid agencies or collaborative initiatives designated with carrying out the activities identified in the partnership’s theory of change (outlined later in this chapter).45

With Digital India, the Apollo program and its hospital network acted as the primary implementation partner. However, the government’s CSCs acted as delivery mechanisms for the services being provided. Local VLEs helped operate the CSCs and acted as a bridge between the primary implementation partners and the communities where the CSCs were located.

Stakeholders

Finally, the stakeholders of a partnership may include locally engaged management, place-based experts, any number of community-based institutions, universities or schools, churches and other places of worship, neighborhood associations, or a community’s individuals. In some partnerships, stakeholders may be defined as taxpayers, voters, constituents, members of a neighborhood, or participants of a specific project or program related to the collaboration.46 In most cases, collaborative engagements derive from the active leadership or participation of stakeholders with a highly vested interest in the outcomes of the partnership.47

Stakeholders in the Apollo partnership were many. Not only did this include residents in all the communities where the CSCs were delivering new Apollo health services. This also included the VLEs, who were local area residents, and who received an equal cut of the program fees as Apollo. This benefited the local community in numerous ways—not least of which were improved health outcomes and cost savings from preventative care. It also supported the overall climate for small businesses in each area and boosted local wealth creation.

Oftentimes organizations overlap between these descriptions. For instance, an NGO may serve as an implementer in one partnership and a cofunder in another. Or an implementation partner, such as a VLE, may operate a community-based organization with local stakeholder interests. However, these generalizations hold true when groups are categorized based on the primary activities they undertake and their responsibilities relative to other participants in the partnership.

HOW PARTNERS STRUCTURE THEIR COLLABORATION

Organizations working together to form partnerships must structure activities in ways that coordinate their respective strengths and provide an environment for sustained, collective impact.48 Because the functions of a partnership may vary, and because there may be multiple partners across roles, structuring a collaboration can be incredibly complex. Funders, implementers, and stakeholders can model partnership engagements in diverse ways. The following set of examples, written by and adapted from findings and analysis of the 2009 Collaboration Prize, represent distinct models for how organizations can work together and advance their common goals.49

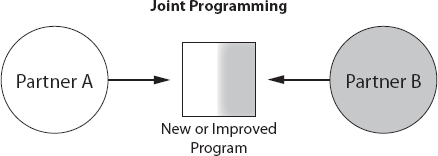

Joint Programming

Funders, implementers, or community-based organizations frequently partner to deliver new or improved programming, which may occur in one of two ways (figure 4.1).50 They may combine otherwise separate programs into one, especially if those programs have significant overlaps and would benefit from economies of scale. Groups forming a joint programming effort to eliminate duplicative activities or operating expenses will benefit from coordinated action toward a common goal. For example, a community food bank and a nearby health clinic might separately conduct nutrition-related programming—including conflicting or competing educational outreach. Although their core missions remain distinctly different, these groups could be more effective if this aspect of their programming were jointly developed and executed in concert.

Figure 4.1 Joint programming allows partners to benefit by reducing duplicated efforts or by leveraging complementary activities for new or expanded programs.

Alternatively, this model may be used when partners work together to form new programming based on their strengths rather than combine already existing programs. This was the case in the Apollo Telemedicine example when the CSCs partnered with the VLEs to deliver Apollo’s new health services.

Affiliated Programming

Some organizations may be engaged in programming that is complementary but not as duplicative as the previous example.51 These groups may engage in a type of joint affiliated programming, working together to develop shared projects (figure 4.2). This can be effective when there is an existing overlap in programming or the delivery of goods or services or when there is a natural hand off between groups. For example, a community youth development nonprofit and a local government job placement agency may jointly develop programming for the same stakeholders at different stages in their life. Such a partnership may result in a conveyer belt approach, providing services for constituents as they age or progress through their education and training.

Figure 4.2 When partners engage in affiliated programming, they maintain independent operations but coordinate activities to better accomplish their missions.

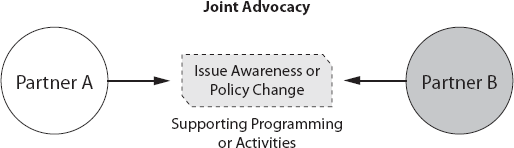

Joint Advocacy

Multiple organizations may choose to work together and form a partnership for joint issue advocacy (figure 4.3).52 This may be done when groups collaborate to raise awareness about a topic of shared importance, such as economic development in a low-income community. This type of collaboration may be a relatively short-term engagement when there is a need for concentrated visibility on a specific subject or impending policy change. For example, a hybrid-energy car manufacturer and an environmental nonprofit may work collaboratively to pass a ballot measure supporting tax incentives for purchasers of low-emission vehicles.

Figure 4.3 With a joint advocacy partnership, organizations work to elevate awareness of issues of shared interest, particularly as they relate to policy changes.

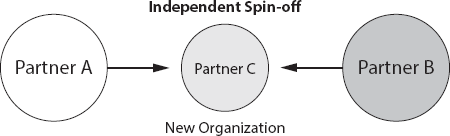

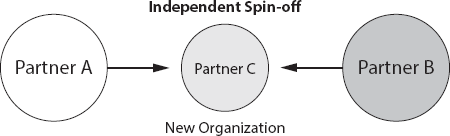

Independent Spin-Off

Another form of partnership is when organizations combine resources into an entirely new, independent entity (figure 4.4).53 This can happen when a joint programming office or a partnership for joint issue advocacy matures or grows significantly and would benefit from having its own streamlined operations. This is also true if the founding organizations cannot or do not want to take on additional activities internally, or if a joint program evolves outside of the scope of the founding organizations’ missions. For example, a foundation and a university might work jointly to raise awareness about the importance of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education. In this case, programming and mutually contributed staff time grow to a point where the program’s mission would benefit if it were an independently operated nonprofit organization.

Figure 4.4 Organizations may jointly form an independent entity when doing so enables them to support related or complementary activities while remaining focused on their core missions.

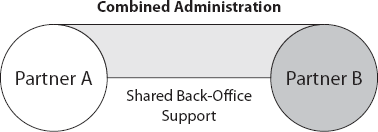

Combined Administration

With a combined administrative or back office partnership, two or more organizations identify overlapping resource needs or excess capacity (figure 4.5).54 This could include underutilized operations staff, excess office space, or access to prohibitively expensive technology or other infrastructure. These groups may come together to share resources without creating new programs or separate legal entities, and in doing so, they may benefit from reduced costs or overhead. For example, a university and a group of small companies may coinvest in advanced research and laboratory equipment to support similar research and development needs. Or two nonprofits may simply decide to share backend accounting and legal services that they cannot otherwise take full advantage of independently.

Figure 4.5 Even when partners do not create new or expanded programming, they may benefit operationally by combining or streamlining certain administrative or back office activities.

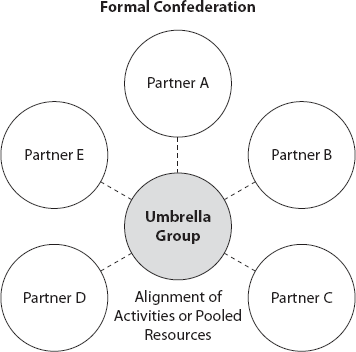

Formal Confederation

Through a formal confederation structure, a parent organization or umbrella entity provides services and support to a group of member partners (figure 4.6).55 Although structures vary widely, member groups may pay fees or otherwise finance the operations of the coordinating organization. In return, all members receive benefits, including leveraged resources and visibility. On a global scale, the United Nations functions as a form of confederation, providing diplomatic services (among other things) to its sovereign nation-states. Alternatively, a membership organization may bring together companies, nonprofits, and foundations all working in a similar field, such as health care, and provide services to enhance knowledge sharing, workforce development, and public policy.

Figure 4.6 A formal confederation enables organizations to partner directly or indirectly through a parent or umbrella group that provides collective services or benefits to members.

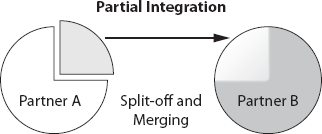

Partial Integration

Finally, two organizations may choose to partner through a partial integration, either at the organization or the program level (figure 4.7).56 In such a case, the majority of one group’s programs may be absorbed by the other partner in a way that leaves the brands of both groups intact but with a new partnership story. This can provide distinct strategic advantages to each organization while eliminating duplicity and competition. One organization may voluntarily spin out a specific program that is adopted or acquired by another organization. For example, imagine a small community-based organization that focuses mainly on preventing the spread of sexually transmitted diseases. One of the group’s benefactors wills them a home to be used as a halfway house. After a year of struggling to operate the house as a new program, the organization decides to partner with a larger nonprofit that already successfully operates multiple similar facilities. The first group officially transfers ownership of the house to the new partner but continues to provide their prevention services. This is the least typical example of the types of cross-sector partnerships discussed here, but it does take place.57

Figure 4.7 Through a partial integration, organizations partner by merging certain programs or activities while maintaining their separate brand identities and operational independence.

DEVELOPING A THEORY OF CHANGE

Once partners have established common definitions, goals, and functions, and an understanding of each other’s partnering rationale, the focus shifts to the partnership’s program strategy. This section will discuss two considerations for developing outcome-driven solutions across a set of diverse organizations working toward common goals.

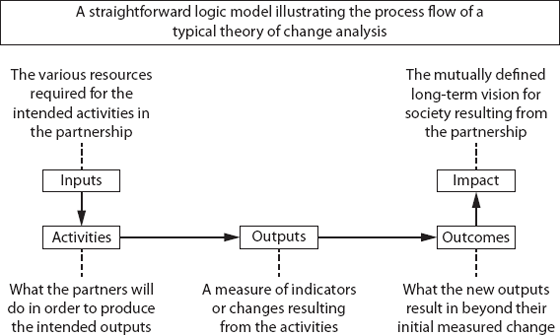

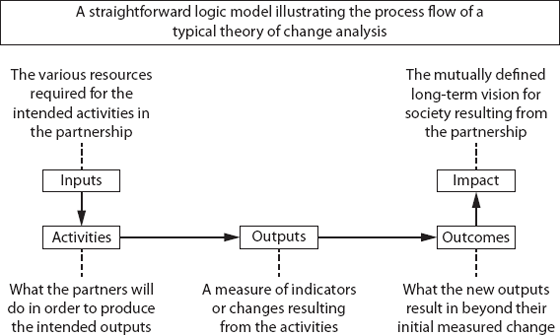

Through our work, we have observed a surprising number of organizations that fail to adequately (or collaboratively) define each aspect of a proposed partnership’s strategy or scope. Frequently used in the philanthropic or nonprofit community, a theory of change is a comprehensive outline and visual depiction of a desired set of outcomes.58 Although these frameworks can vary widely depending on complexity, preference, and need, the process for developing a collaborative theory of change should begin at the end: partners must define their common goals and intended long-term societal outcomes for the engagement.59

As a next step, partners then work backward to map out which intermediary steps stand between the present situation and their hoped-for outcomes, often accompanied by measurable outputs from a set of activities. These activities must be defined, along with appropriate indicators, and assigned ownership responsibilities. More thorough theories of change articulate prerequisites for success, organized thematically, such as the necessity for knowledge development, policy change, or infrastructure investments. Finally, partners should create a comprehensive list of the resources and inputs required for the activities and identify which of those resources are available and which are missing among the partners. Figure 4.8 illustrates the logic flow for a theory of change model. Although many organizations undergo a similar type of strategic planning for their individual missions, it is vital for multiorganizational partnerships to plan like this as well.60

Figure 4.8 A theory of change logic model provides partnering organizations with a planning process resulting in an overview and logic flow of inputs and activities required to reach a desired set of outcomes and impact.

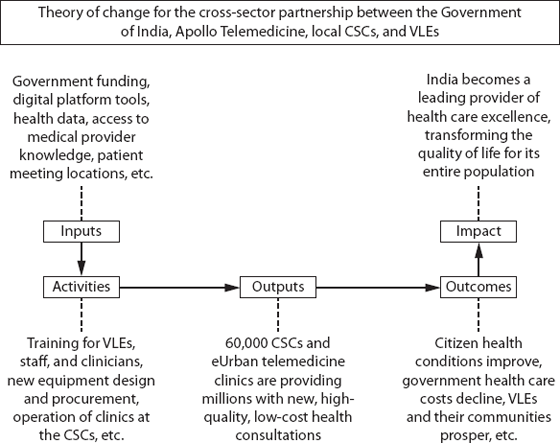

In the Apollo Telemedicine case, for example, the partners undertook a fairly comprehensive planning analysis. They recognized that the partnership would be both complex and expansive and would carry a relatively high risk of failure, especially given the extensively decentralized nature of the service delivery. Building on the previous model, figure 4.9 illustrates what a simple theory of change might include in the Apollo Telemedicine case study. In practice, the logic model used by partners in cases such as Digital India are far more multifaceted and in-depth and should include a detailed time line (likely in the form of a Gantt chart) linked to the various actions and stages in the theory of change.

Figure 4.9 This example logic model provides a simple illustration of various elements in a theory of change applicable to the Digital India partnership profiled in the chapter 3 case study.

Developing long-term, permanent solutions to complex challenges will not typically occur without a collaboratively developed and integrated approach that allows partners to test each other’s assumptions, thoughtfully plan activities, and establish pathways to success.61

COMPREHENSIVE PLANNING THROUGH VALUE CHAIN ANALYSIS

Completing a theory of change process alone is not enough to develop a comprehensive partnership strategy. As a program-focused model, it outlines resources for inputs and the various stages or steps needed to reach a given outcome. A similarly important process charts the overall system of organizations and, frequently, the flow of goods or services related to the inputs, activities, and outcomes outlined in the theory of change. This may include how various programs interact with one another, or dependencies between programs and services. It may require an understanding of different economic and contextually relevant variables in a particular place or geography and mapping of value chains related to the partnership’s goals.

Value chain analysis was originally developed as a tool for looking at an organization’s “strategically relevant activities” across supply chains and how that process ultimately brings value to customers.62 We broaden the value chain analysis to include wider systems in which societal challenges are being addressed or a public good is being supported through a partnership. This includes the various interactions and operational functions that go into a partnership’s development and the production and delivery of relevant products or services that support shared goals. Expanded definitions may include research and development, workforce training, competitive environment analysis, marketing and sales, and other industry or sector-relevant support over the long term.63

Many of our examples of partnerships deal with complex systems, and the pathway to system-level change may not be immediately “linear, predictable or controllable.”64 Comprehensive planning requires a thorough understanding of the context, interconnectedness, and dependencies between organizations relevant to the partnership’s goals and activities.65

Many complex challenges in global development are sustained by similar factors: immediate resource constraints, lack of appropriate regulations, rule of law considerations, or economic market failures. Organizations themselves may be resource-constrained, focusing on single or isolated portions of a given challenge or “intervention” taking place within the context of a larger system’s failure. This type of siloed approach is arguably a root cause of organizational failure or project dysfunction, and it exists across all sectors despite being a long-recognized problem.66

One major challenge is that few funders are excited about financing expensive and time-consuming up-front research. This can include field surveys to analyze existing activities, studies on economic and regulatory conditions, and reviews of academic literature. It also may mean conducting informed theories of change processes alongside other funders, local organizations, community members, and city or provincial governments.

This is even more challenging if past attempts at in-depth planning have failed. Partners may be reluctant to invest time and energy in this type of analysis if past work has gone unnoticed or unused. They may have produced reports that went nowhere—gathered dust on shelves, unread and unstudied. In rapidly changing environments (such as conflict zones or during immediate postdisaster recovery efforts), any kind of in-depth studies may be outdated before they are even completed.

Despite these challenges, concerted analysis must take place if a multiorganization effort, implemented over a long period of time, hopes to be successful. Many multiyear, complex initiatives require distinct research and planning phases, beginning with problem definitions and the identification of root causes.67 This kind of early analysis is even more important in underdeveloped geographic areas because a systems analysis may challenge partners’ assumptions and provide unexpected insights. Furthermore, a single break in a value chain can disrupt an entire collaboration’s efforts. Not addressing gaps identified in this analysis means that resources invested upstream or downstream of that disruption might fail to have a sustained impact.68

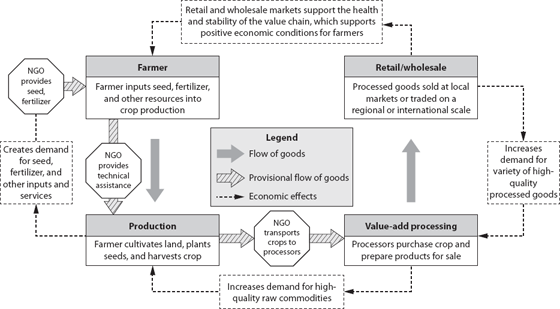

For example, consider a three-year rural development project in a poor country with an agrarian economy. The project hopes to improve smallholder farmer productivity, with an end goal of increasing a farmer’s crop output, thereby increasing income and improving the farmer’s livelihood.69 In this example, a donor aid program (run by an NGO) receives funding to provide new seeds and fertilizer to a group of fifty farmers and provides them with technical assistance and advice. In this example project, the farmers see a nearly instantaneous increase in yields, and the donor agency deploys vehicles and staff to help transport that season’s bumper crop to regional markets and food processors. The farmers produce more, sell more, make more money, and invest in their families’ livelihoods. For example, farmers may purchase livestock to produce additional products and diversify their revenue streams.

Figure 4.10 outlines a simple generic version of an agricultural-based value chain, including the example activities of the NGO donor aid program.

Figure 4.10 Value chain models can depict complex economic systems and dependent relationships between inputs, activities, and outputs. In this generic agricultural-based value chain example, temporary support from an NGO donor aid program illustrates the problematic nature of short-term solutions when long-term, system enabling investments are required.

Based on the goals of this isolated program, they will achieve success for the fifty farmers and their families. The implementer will likely write a report for its funder reflecting the program’s accomplishments and lessons learned, and they will consider their project complete. But some obvious questions arise:

■ What happens in the fourth year when the NGO program ends and new seeds and fertilizer stop coming?

■ Even if farmers have another plentiful crop, how will they transport it to market without the NGO vehicles or staff support?

■ What happens if the farmers do not produce enough extra crop to feed their livestock, or the livestock get sick?

■ What if a new monetization program starts nearby and destroys local sales prices for the farmers?

Questions such as these arose during partnership development for our Afghanistan case study later in the book. In chapter 7, you will see this type of value chain analysis in practice.

It is challenging to have a permanent and lasting effect when working in difficult operating environments. Furthermore, organizations working in isolation cannot face the challenges that require a systems scale solution, especially if there is not an entire economic support system in place to pick up when aid money runs out.70 Long-term solutions cannot fail to address market linkages, resource waste, labor shortages, contract enforcement, disaster mitigation, and a host of other potential roadblocks.

Planning with a comprehensive approach in mind may sound like common sense, and it is certainly nothing new, but many programs suffer without systems thinking or fail to address gaps in the value chain—especially when those gaps fall outside their core funding or programmatic areas.71 Hence, planning and analysis are important components in the social value investing approach.

OVERCOMING OBSTACLES

Engaging in effective partnership development is difficult work, and it presents numerous challenges.72 Leaders of some organizations simply do not understand the potential benefits to partnering or value what may come of the work. Some leaders or administrators may be indifferent. In many cases, an organization simply lacks the resources or human capacity required to meaningfully engage in partnership development. Or they may not have the mandate to do so from their funders or a parent organization. Some groups will have tried before and failed, and others lose interest when attempting new partnerships. Building out long-term, cross-sector collaborations is complex and time consuming. Ensuring that partners begin with a similar understanding of the intended objectives through a collaborative design process is an early prerequisite for success. Incentives and motivations for stakeholders within a partnership can be very different; aligning these is not easy and should be addressed as early as possible in the collaborative process.

Public, private, and philanthropic organizations working to develop a comprehensive partnership strategy must survey the complete value chain of a given industry or set of objectives in a given place and combine this analysis with appropriate logic models to cover critical enabling factors needed for sustained positive impact. Such planning allows partners to chart the interdependent web of organizations required to work together for an entire ecosystem of solutions to flourish.73

In the case study in chapter 3, we described collaborative efforts to modernize the way the government of India delivers social services to the poor. We described how a diverse set of partners, coordinating their efforts throughout the value chain of health care services, could unlock intrinsic value worth more than the sum of their individual and isolated activities. We believe these types of strategic, comprehensive partnerships can bring about new and important emergent processes that are critical for success—and for solving many of our world’s most persistent and pressing problems.