11 |

The Patient’s Mental Status and Higher Cerebral Functions |

As not only the disease interested the physician, but he was strongly moved to look into the character and qualities of the patient. … He deemed it essential, it would seem, to know the man, before attempting to do him good.

I. THE MENTAL STATUS EXAMINATION: A NONPROGRAMMED INTERLUDE

A. How to derive the mental status information

1. Most of the data for judging the patient’s (Pt’s) mental status emerge as a natural consequence of the questions posed during the standard medical history, which this text does not cover. Although you do the basic Neurologic Examination (NE) by a set routine, you should probe the Pt’s mental status unobtrusively and flexibly. If you blurt out questions obviously designed to test the mental status, such as, “Do you hear voices?” the Pt may respond with annoyance, sullen silence, or outright anger. Nevertheless, just such a question, introduced at the proper time, encourages the disclosure of distressing thoughts. The Pt then may describe the voice that repeats, “You have a duty to kill your family.” Because your personal characteristics and interview techniques condition what the Pt can and will disclose, you must remain flexible, empathetic, and nonjudgmental. This is the first point: the interview technique is everything.

2. By monitoring the Pt’s responses, you determine which questions to use and how far to pursue any particular line of inquiry. As long as the Pt talks productively, continue the line of inquiry. If the Pt changes the subject or becomes evasive, flustered, or silent, you have pressed too hard. The Pt is not ready to talk about that. Try another tack. A mentally ill Pt may permit a full NE but completely resist inquiries obviously designed to disclose thoughts. Patients will talk about whatever problems and anxieties occupy their thoughts, if they can tolerate the thought and its communication. This is the second point: Pts will disclose their mental state, particularly their worries and concerns, if you provide a free opportunity.

3. We have highlighted the two most important statements. With these in mind, you may find it useful to re-read Chapter 1, Section I E.

B. Categories of the mental status examination

1. The examiner (Ex) must know and explore each category of the mental status examination (Arciniegas and Beresford, 2001; Strub and Black, 2000). Learn Table 11-1.

TABLE 11-1 • Outline of Mental Status Examination

I. General behavior and appearance |

Is the patient normal, hyperactive, agitated, quiet, immobile? Is the patient neat or slovenly? Do the clothes match the patient’s age, peers, sex, and background? |

II. Stream of talk |

Does the patient converse normally? Is the speech rapid, incessant, under great pressure, or is it slow and lacking in spontaneity and prosody? Is the patient discursive, tangential, and unable to reach the conversational goal? |

III. Mood and affective responses |

Is the patient euphoric, agitated, giggling, silent, weeping, or angry? Is the mood appropriate? Is the patient emotionally labile? |

IV. Content of thought |

Does the patient have illusions, hallucinations or delusions, and misinterpretations? Does the patient suffer delusions of persecution and surveillance by malicious persons or forces? Is the patient preoccupied with bodily complaints, fears of cancer or heart disease, or other phobias? |

V. Intellectual capacity |

Is the patient bright, average, dull, or obviously demented or mentally retarded? |

VI. Sensorium |

|

2. Because much of the mental status examination belongs to the psychiatric history, this text focuses on the sensorium because:

a. Sensorial testing uses questions that require more or less objective answers for passing or failing, for example, either you know what day it is, or you do not know what day it is.

b. Sensorial deficits are sensitive to organic impairment of the brain.

C. The nature of the sensorium

I think; therefore I am.

The sensorium is that place where you are aware that you are aware.

1. We all intuitively recognize our awareness of ourselves and our environment. Without consciousness, no other categories of the sensorium are tenable or testable. But consciousness requires a content. At any moment we are conscious of objects, the state of our bladder, the time of day, our feelings, etc. We call our awareness the sensorium.

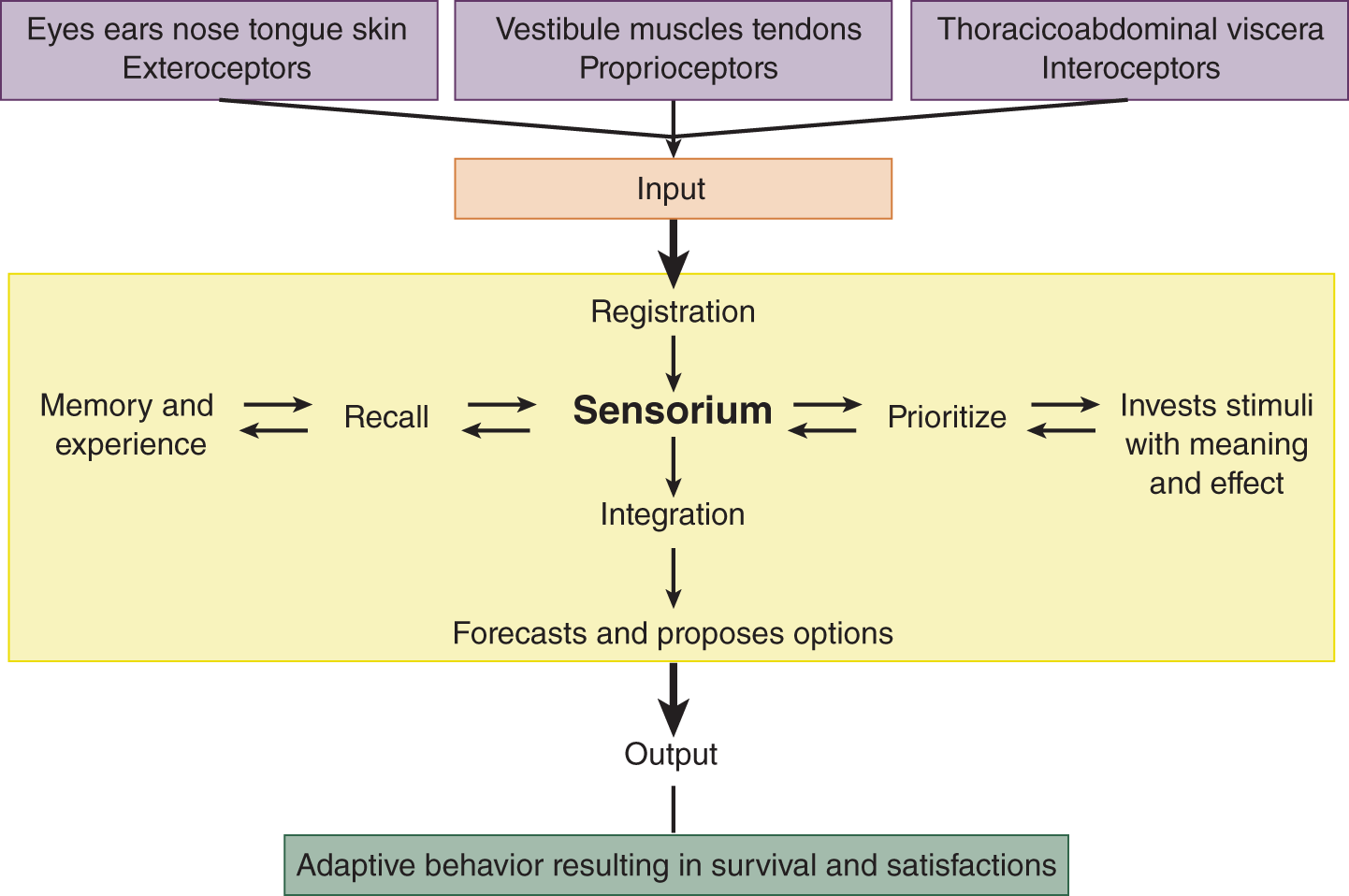

2. Functions of the sensorium:

a. Registers current internal and external contingencies.

b. Relates current internal and external stimuli to our memories and to our future hopes and desires.

c. Invests the streams of afferent stimuli with emotion, determines their significance, and assigns priority that results in neglect or attention.

d. Proposes various actions and their consequences.

e. Directs the motor system in the actual behaviors that achieve personal survival and satisfaction.

f. Allows us to experience life as a conscious process with a past, present, and future and to respond appropriately (Fig. 11-1).

FIGURE 11-1. Diagram of the sensorium as an input–output system.

3. Examples of sensorial responses to internal or external contingencies

a. Internal contingencies: Anxiety about academics: “Maybe I better study tonight.” Hunger: “Maybe I better eat something.”

b. External contingencies: Fire: “I better get away from here.” Meeting another person: “Mmmm, I would like to know that person better” or “Mmmm, I should avoid that person.”

c. The sensorium is ever vigilant and somewhat suspicious in order to avoid harm and gain advantage.

D. The sensorium commune: the common sense of all human kind

1. The ancients recognized that every person who is sound of mind has a sensorium commune, a sense in common of:

a. Who they are, their role, and station in life: parent, child, student.

b. Where they are: at home, school, hospital, the bathroom.

c. When it is: It is noon. It is today, a particular date. Yesterday has passed. Tomorrow will come. It is winter, not spring, summer, or fall.

d. What is happening: It is snowing. The house is on fire. A dog is barking.

e. How the wise and prudent person should behave: Thus, we have the common sense to come in out of the snow, to get out of a burning house, and to yell at the dog to stop yapping, because we all sense these circumstances as dangers or nuisances.

2. What is uncommon sense (unshared sense)?

a. The uncommon senses or perceptions that we do not share are our personal political, religious, and moral beliefs, for example, there is a God/there is no God.

b. Hence, we avoid specific questions about these topics and most of all avoid debating them in the medical setting because they generate argument, not medical data. Questions on such topics lack quantifiable, objective end points that test the organic condition of the brain, as do questions about the sensorium.

E. Testing for acute dysfunction of the sensorium after a concussion

1. Patient analysis: A blow to the head has rendered a 21-year-old athlete unconscious for 2 minutes. As the Ex reaches the player, who still lies on the playing field, consciousness appears to have returned. The Ex’s quick neurologic appraisal shows normal breathing, pupils, eye movements, and spontaneous movements of all extremities. These findings exclude a major catastrophe such as spinal cord transection or a large cerebral lesion. To quickly, but effectively, evaluate the athlete’s sensorium, the Ex asks a series of who, where, when, and what questions, posing them seriatim because of the urgent circumstances (Table 11-2).

TABLE 11-2 • Questions to Detect Acute Sensorial Dysfunction After a Head Injury

“Hello, what is your name?”(orientation to person) “Who am I?” (orientation to person and your role as a physician: an athlete should know the team physician) “What is the day and date?” “What is the time of day?” (orientation to time) “Where are we?” (orientation to place: practice field or stadium) “What has just happened to you?” or “What was the last play?” (current events and recent memory) “What team are you playing?” (current events and recent memory) “What is the score of the game?” (current events and recent memory) “Can you repeat the months of the year backward?”(comprehension and attention span) “Can you remember these three items?” Recite an item such as table, a color, and an address and ask the patient to repeat them after a few minutes. (recent memory) Ask about pain, blurred or double vision, tinnitus, dizziness, and numbness or tingling. (Checks current neurologic symptoms) Complete a Standard neurologic examination |

2. By correctly answering all questions, the athlete demonstrates the first four sensorial functions: consciousness; attention span; orientation for time, person, and place; and recent memory (Table 11-1).

3. Asking the Pt to learn three unrelated items, a color, an address, and an object, and then repeat them after 5 minutes adds another useful test, as does spelling the word world backward or reciting the months backward (McCrea et al, 1998).

4. The Ex then asks about neurologic symptoms such as blurred vision, double vision, numbness, and so forth and completes a Standard NE.

5. As an exercise, try to select from Table 11-2 the single most, symbolic, generic question that best tests the athlete’s sensorium if you were limited to one question.

a. We submit, “What is the score of the game?” as the best question, although you may feel differently.

b. Basically, the sensorial tests determine whether the person knows the score, or in street-talk expressing the same thing when meeting someone, we say, “Hey man, what’s coming down?” “What’s happening?” Asking “What’s the score?” subsumes all of these statements that invite newly met persons to display their sensorium.

6. Here is a marvelous, true anecdote of a mother who brought her 8-year-old child into the Emergency Room for examination after a hard fall on concrete had caused severe scalp bleeding:

a. When asked whether the fall had stunned the child. The mother said: “Oh no. I knew she wasn’t stunned ‘cause I asked her who was she and who was I and where was she and what had just happened to her, and she knew all that.”

b. The Ex said: “Those are certainly the right questions. Where did you learn that?” She said: “Why? anybody knows that.” In other words, she posed her perfectly scripted questions from an intuitive appreciation of “common sense” as a test of brain function, the matching of one brain’s perceptions against those of another’s.

F. Testing for chronic dysfunction of the sensorium in the brain-impaired or demented patient

The principle is the same as in acute concussion but the form of the questions differs. Avoid machine-gunning the Pt with a series of simplistic questions: “What is your name? Where are you? What is the day, date, and week? Do you hear voices? Who is the president? Can you remember an item, a color, and an address?” If you ask questions that crudely, the Pt, especially if somewhat demented or mentally ill, will quickly realize that you are probing their mental status. Often they will reply (not a little piqued): “What’s the matter, Doc; do you think I’m crazy?” The Ex ultimately must derive answers to the questions in Table 11-3, but derive them artfully in the natural course of the interview. The Pt should experience it all as an ordinary conversation, not as an inquisition.

TABLE 11-3 • Questions to Detect Chronic Sensorial Dysfunction in Dementia

Area of sensorium tested |

Questions |

Orientation to person, time, and place; recent and remote memory; consciousness of self and environment |

“What is your name?” “How old are you?” “When is your birthday?” “What is your address?” “What kind of work do you do?” “Do you have a spouse/children?” “What are their names/ages/occupations/addresses?” “Where are they now?” |

Orientation to time and recent memory |

“Do you happen to know the time of day?” “Have you had to wait long to see me?” “What is the day/date/month/year?” “What is the season/weather?” “What did you do yesterday?” |

Doctor/patient role: judgment and insight as to presence of illness or need for medical attention |

“What have you come to see me about?” or “Do you feel any need for medical help?” |

Judgment and planning |

“What are your plans for the future?” or “How long do you expect to be off work?” |

Recent memory, fund of information, and attention span |

“What do you think of.…” (mention a recent item in the news). “How has your memory been?” “Are you worried about it?” “Suppose we test it. Can you name the last several presidents?” “See whether you can remember.…” (name an item, eg, a table, a color, and an address) |

Calculation and attention span |

“Subtract 7 from 100, then take off seven more and continue subtracting 7’s.” “Spell world” (or other word) backward, forward, or by alphabetical sequence of the letters. |

G. An operational definition of the sensorium

These deliberations allow us to hazard an operational definition: The sensorium consists of those brain functions tested by a standard set of questions that elicit more or less objective answers about the person’s past, present, and future.

For clinical purposes, we judge “objectivity” and “normality” by matching the Pt’s answers against the answers that standard persons with common sense would make.

H. Where does the sensorium reside within the body?

1. The sensorium cannot be in the limbs and other parts of the body. Their destruction does not alter the sensorium. The two historical contenders for the site have been the heart and the brain.

2. Many ancient savants and scholars located the sensorium in the heart (Keele, 1957; Gross, 2009). After all, the heart races when you are frightened, and when the heart stops, the sensorium stops.

a. The ancient Egyptians seemed to favor the heart because in their embalming practices, they always preserved the heart in a canopic jar or by returning it to the thorax, but they discarded the brain.

b. Aristotle, a Greek (384–322 BC), advocated the heart. In his De Partibus Animalum, he asserted:

For the heart is the first of all the parts to be formed; and no sooner is it formed than it contains blood. Moreover, the motions of pleasure and pain, and generally of all sensations plainly have their source in the heart and find in it their ultimate termination.

3. But dissenters throughout time raised their voices. Hippocrates (5th century BC) said:

And men should know that from nothing else but from the brain came joys, delights, laughter and jests, and sorrows, griefs, despondency and lamentations. And by this, in especial manner, we acquire wisdom and knowledge, and see and hear and know what are foul and what are fair, what sweet and what unsavory.

4. Aristotle’s view of the heart as the site of life and consciousness has persisted in our popular culture, and until the 1960s persisted also in medicine in the very definition of death.

a. In our vernacular, the heart remains the site of consciousness and emotion.

i. We say that a person with no feeling or compassion has no heart. Or the person may be faint-hearted or lion-hearted.

ii. We still speak of love as an affair of the heart, and the heart remains the Valentine’s Day symbol of love. (Can we ever change our vocabulary from sweetheart to “sweetbrain” and declare, “I love you with all of my brain,” rather than, “I love you with all of my heart”?)

b. The Aristotelian view, even though acknowledged as wrong, determined the very definition of death into the 1960s. Medically and legally, death was defined as irreversible cessation of the heartbeat and breathing. We still record the time of death as when the heart stops, even though the brain died long before.

I. Where does the sensorium reside within the brain?

1. Indisputable evidence from clinicopathologic studies clearly places the sensorium in the brain. No contrary evidence exists, now that the critical and decisive experiment, heart transplantation, has once and for all excluded the heart as the site of the sensorium.

2. Although not localizing as specifically as sensorimotor functions, certain parts of the sensorium appear to localize to particular brain regions.

a. Consciousness and attention span to some degree co-localize through the ascending reticular activating system.

b. Recent memory and orientation to person, time, and place are impaired after lesions of the medial temporal lobes and the closely related hippocampal-fornix-mamillary body circuit and basal forebrain (Fig. 11-10), but diffuse cortical or white matter lesions also impair these functions.

c. Calculation has a nodal point in the left angular gyrus region.

d. Insight, judgment, and planning are in large measure executive functions of the frontal lobes.

3. Functional brain imaging undoubtedly will localize sensorial functions, affective states, and thought processes better than the clinicopathologic correlation studies of the past.

4. To end the preliminaries poetically, we may regard the sensorium as the place of knowing, that place where we know what we see, hear, and feel; or, ironically in Aristotelian terms, it is where the heart is, where we have our perceptions, feelings, and priorities.

J. The sensorium and sensory deprivation

The notion that the sensorium knits all of the individual sensory impressions into a stream of consciousness anticipated modern studies in sensory deprivation. A person confined to a stimulus-free, totally dark, totally soundproof, constant-temperature chamber devoid of environmental fluctuations and human contact finds that the sensorium weakens. Boredom alternates with fright. The thoughts become loose and detached, and hallucinations follow. Continued isolation causes complete disintegration. The sensorium requires incessant change—the interplay of light and dark, sound and silence, pain and pleasure—to function. The philosophic ideal of pure thought, free from the fetters of the flesh and its environment, is therefore exposed as a fraud. The sensorium functions not floating free as a cloud but with respect to the ever-changing stream of internal and external stimuli. Thus, you behave differently in a classroom than in a swimming pool, and you survive in both.

K. Detailed examination of the sensorium

1. Consciousness: Because you obviously cannot respond consciously when asleep, the sensorium is a property of the waking state. For the moment, we define consciousness intuitively as awareness of self and environment. (Chapter 12 discusses operational tests of consciousness.) Does the Pt make responses that prove awareness of self and environment?

2. Attention span: After consciousness comes attentiveness, the attention span of the individual. Can the Pt attend to stimuli long enough to comprehend and respond to them, or attend to a task long enough to complete it? For a simple, effective test, ask the Pt to recite the months backward or spell the word world backward (McCrea et al, 1998).

3. Orientation: If conscious and attentive, does the Pt comprehend who and where he or she is and when it is? This orientation as to person, place, and time requires ongoing sensory impressions. Have you ever awakened from a deep sleep momentarily disoriented as to the day, the hour, or even where you were? If so, you had to process different afferent stimuli, until all of the pieces of the puzzle suddenly fell into place. Judge the Pt’s orientation:

a. As to person: Does the Pt recognize him- or herself and his or her role, the other people present, and their roles?

b. As to place: Does the Pt recognize that he or she is in a clinic or hospital, its name, and the name of the city and state?

c. As to time: Can the Pt recite the time of day, day of the week, the month, and the year?

4. Memory: Orientation, attention span, and memory intertwine inextricably. Screen for memory this way:

a. Note how well the Pt recalls and relates the events of the medical history.

b. Inquire, “Does your memory work all right?” Or more bluntly, “Do you have trouble with your memory?” If you suspect a memory disturbance, say to the Pt, “Suppose we try out your memory?” Ask the Pt to name the presidents backward from the present one. Although also requiring a long attention span, this task requires more attention and memory than reciting the months backward.

c. Next provide the Pt with an address, a color, and an object to remember, three nonsense items that have no special relation: 5330 Broadway, orange, and table. Have the Pt repeat the items to ensure that they have registered. Then, at the end of the NE, ask the Pt to recite them.

d. Determine whether the Pt differs in the ability to recall recent or remote events. Can the Pt remember what he or she ate for breakfast? Recent memory suffers most in aging or brain diseases in general. To easily remember this difference, recall that grandfather cannot remember where he just laid his glasses, but he can wax eloquently about the events of long ago.

5. Fund of information: The oriented, attentive Pt with a good memory knows what is happening in the world. Ask about current activities or events. If unable to discuss current activities and events, the Pt has organic brain disease, cultural deprivation, or is so withdrawn as to need psychiatric care.

6. Insight, judgment, and planning: Simply ask what the Pt plans to do. Do the proffered goals and plans match the Pt’s physical and mental capabilities? The Pt with quadriplegia who expects to work as a carpenter or the individual with a borderline IQ who expects to become a chemist lacks insight, judgment, and planning. Does the Pt recognize the illness and its implications?

7. Calculation: Test calculation by asking whether the Pt can balance a checkbook, make change, do formal paper-and-pencil calculations, and subtract 7’s serially from 100.

L. Affective responses

Besides being conscious, attentive, and oriented, having a good memory, a fund of information, insight, judgment, and planning, the standard person reacts emotionally to ongoing events. Imagine your reaction to a hand grenade thrown onto your table or merely to a cockroach. Your alarm or aversion differs in the two cases. Affective responses should have the appropriate quality and quantity.

1. Assay affective responses not by blunt questions, but by comparing the observed with the expected reactions. What affect would you expect as a Pt discusses her paralyzed arm? What affect would you expect if the Pt complains that the “apparatus” plots to kill him? A blunted, bland, or indifferent affect occurs most commonly with hysteria, schizophrenia, and bifrontal lobe lesions.

2. If you have cause to cry or laugh, how much provocation does it take to make you start and how much time does it take you to get over it? If the Pt cries for 15 seconds and then starts to laugh when you ask him to tell you a funny story, the Pt has affective lability, the opposite of affective blunting. Affective lability, on-and-off laughing and crying, commonly accompanies bilateral upper motoneuron (UMN) disease, as we have seen in pseudobulbar palsy and diffuse brain diseases.

M. Perceptual distortions: illusions, hallucinations, and delusions

1. Illusions: Everyone has experienced the illusion of water shimmering on a hot highway on a summer’s day. The water is an illusion. An illusion is a false sensory perception based on natural stimulation of a sensory receptor. The healthy person recognizes the illusory nature of such an experience, but the sick person may not.

2. Hallucinations: Observe that sweating, tremulous man cowering on the bed, screaming about dogs and snakes in the corner of his room. Or observe this calm woman with an expressionless face who tells you in a flat voice that she hears God’s voice ordering her to drown her baby. Both Pts display characteristic hallucinations: the man has delirium tremens, and the woman schizophrenia. Before an epileptic seizure, many Pts experience visual, auditory, or somatic hallucinations. An hallucination is a false sensory perception not based on natural stimulation of a sensory receptor (Videos 11-1 and 11-2). The mentally ill Pt usually does not recognize the hallucination as a false representation of reality, whereas the Pt with epilepsy does.

Video 11-1. Musical hallucinations.

Video 11-2. Release visual hallucinations following a right posterior cerebral artery territory infarction in a patient demonstrating a congruous left homonymous hemianopia.

Hypnagogic and hypnopompic hallucinations are not true hallucinations. A hypnagogic hallucination represents wakeful dreaming while falling asleep, while a hypnopompic hallucination represents wakeful dreaming immediately after waking up.

3. Delusions: This Pt, eyeing a nurse carrying a tray into the room, says to you sotto voce, “There is one of them now. She is trying to poison me.” You err in responding to this remark if you try to reason with him that she has merely come to take his temperature. Somehow, his psychic economy needs to misperceive the nurse as a conspirator, and all the reason in the world will not dispel his belief. A delusion is a false belief that reason cannot dispel.

4. Literary geniuses frequently depict illusions, hallucinations, and delusions. Try to identify these perceptual distortions (and get reaccustomed to the programming that follows in the next section):

a. Here, Macbeth muses alone after murdering Duncan:

Is this a dagger which I see before me,

The handle toward my hand? Come, let me clutch thee:

I have thee not, and yet I see thee still.

Are thou not, fatal vision, sensible

To feeling as to sight? Or art thou but

A dagger of the mind, a false creation,

Proceeding from the heat-oppressed brain?…

Mine eyes are made the fools o’th’other senses.

Or else worth all the rest: I see thee still.…

b. This exemplifies  an illusion/

an illusion/ an hallucination/

an hallucination/ a delusion, which is defined as_________

a delusion, which is defined as_________

_________ hallucination) (a false sensory perception not based on natural stimulation of a sensory receptor)

hallucination) (a false sensory perception not based on natural stimulation of a sensory receptor)

c. Here is a passage from Gérard De Nerval poem The Dark Blot:

He who has gazed against the sun everywhere he looks thereafter, palpitating on the air before his eyes, a smudge that will not go away.

d. This exemplifies  an illusion/

an illusion/ a hallucination/

a hallucination/ a delusion which is defined as _________

a delusion which is defined as _________ illusion) (a false sensory perception based on natural stimulation of a sensory receptor)

illusion) (a false sensory perception based on natural stimulation of a sensory receptor)

e. Here, lawyer Porfiry Petrovitch, in Fyodor Dostoyevsky Crime and Punishment, discusses a client:

“Yes, in our legal practice there was a case almost exactly similar, a case of morbid psychology,” Porfiry went on quickly. “A man confessed to murder and how he kept it up! It was a regular hallucination; he brought forward facts, he imposed upon every one and why? He had been partly, but only partly, unintentionally the cause of a murder and when he knew that he had given the murderers the opportunity, he sank into dejection, it got on his mind and turned his brain, he began imagining things, and he persuaded himself that he was the murderer. But at last the High Court of Appeals went into it and the poor fellow was acquitted and put under proper care.”

i. Was lawyer Petrovitch correct in stating that his client suffered from “a regular hallucination”?  Yes/

Yes/ No. (

No. ( No)

No)

ii. Is the client’s mental aberration  an illusion/

an illusion/ a delusion? (

a delusion? ( delusion)

delusion)

iii. Define a delusion. (A delusion is a false belief that reason cannot dispel.)

5. Localizing significance of hallucinations: Although hallucinations may accompany a variety of mental illnesses or diffuse metabolic diseases, repetitively experienced hallucinations may indicate a lesion of the appropriate sensory cortex. A lesion in the occipital cortex might cause hallucinations of vision; in the uncus, of smell; and in the postcentral gyrus, of somatic sensation. Such hallucinations often constitute part of the aura, or forewarning, of an epileptic seizure produced by a focal epileptic discharge in one of these areas.

BIBLIOGRAPHY · The Mental Status

Arciniegas DB, Beresford TB. Neuropsychiatry. New York, NY: Cambridge Univ. Press; 2001.

Gross CG. A Hole in the head. More Tales in the History of Neuroscience. Cambridge, Massachusetts, London, England: The MIT Press; 2009.

Keele K. Anatomics of Pain. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas; 1957.

McCrea M, Kelly JP, Randolph C, et al. Standardized assessment of concussion (SAC): on site mental status evaluation of the athlete. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 1998;13:27–35.

Strub RL, Black FW. The Mental Status Examination in Neurology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, FA: Davis; 2000.

II. AGNOSIA, APRAXIA, AND APHASIA

I translate into ordinary words the Latin of their corrupt preachers, whereby it is revealed as humbug.

A. Introduction to agnosia, apraxia, and aphasia

Fate foredooms every medical student to address the deficits signified by these three mystifying Greek terms. Despite the fascinating subject, the name-plagued literature on agnosia, apraxia, and aphasia discourages even the hardiest scholar. Aphasiologists, in particular, are a contentious lot. Each one, compulsively it seems, must disagree with the methods, concepts, and nomenclature of their predecessors. Philosophy and polysyllabic words prevail, resulting in considerable humbug, hence, the quote from Brecht. For salvation, we shun the rhetoric and simply ask: By what operations do we discover the signified deficits?

B. Agnosia

1. Review of agnosia: Agnosia means literally not knowing. A root of a word when attached to -agnosia or -ognosia then specifies what the Pt does not know. As a review from Chapter 10, list some common agnosias tested in the Standard NE.

_________

_________

2. General definition of agnosia: Knowing the operations that disclose agnosia (eg, give the Pt certain stimuli to identify) justifies a general definition. Agnosia is the inability to understand the meaning, import, or symbolic significance of ordinary sensory stimuli even though the sensory pathways and sensorium are relatively intact. Learn this definition. Agnosias affect various modalities, visual, auditory, or tactile. The Pt may fail to recognize stimuli in one modality but then recognize them in another.

3. An optimal definition not only states what something is but what it is not and the conditions necessary to diagnose it. The necessary conditions to diagnose agnosia are:

a. The Pt’s sensory pathways are relatively intact.

b. The Pt’s sensorium and mental status are relatively intact.

c. The Pt previously understood the symbolic significance of the stimulus, that is, was familiar with it.

d. An organic cerebral lesion causes the deficit.

4. These conditions exclude Pts with interrupted sensory pathways, intellectual developmental disorders, overt dementia, and functional mental illnesses such as somatic symptom disorders and negativistic personality disorders.

5. Agnosias beyond the scope of this text include associative visual agnosia (modality-specific inability to recognize and name previously known objects or their pictures or to demonstrate their use), apperceptive visual agnosia (impaired perception of patterns and inability to recognize shapes; Giannakopoulos, 1999), and color agnosias.

C. Agraphognosia (agraphesthesia)

1. Technique for testing: With the Pt’s eyes closed, trace letters or numbers between 1 and 10 on the skin of the palm or fingertips. Use any blunt tip, such as the cap end of a ballpoint pen.

a. Normal educated people rarely miss the traced figures, but a normal person unpracticed in numbers may sometimes err.

b. In testing for agraphognosia in the left hand, you test the  right/

right/ left _________

left _________ right; parietal)

right; parietal)

2. For a Pt unable to recognize letters written on the skin and whose lesion had destroyed sensory pathways, the correct term would be _________

3. The same pathway from the periphery to the somatosensory cortex that detects the direction of movement of a stimulus across the skin also mediates graphognosia (Bender et al, 1982).

D. Prosopagnosia

1. Prosopagnosia means the inability to recognize faces in person or in photos (Video 11-3).

Video 11-3. Prosopagnosia.

2. Technique to test for prosopagnosia: The Ex asks someone known to the Pt to enter the room. The Pt cannot recognize the person’s face but does recognize the individual immediately by the voice sound when the person speaks. When looking at a facial photo of family or a well-known celebrity, the Pt can see the face and can even describe the parts but fails to recognize who the person is. It probably should be noted that this syndrome is not just limited to recognizing human faces, but to recognizing items with specific historical significance within a class of objects. As such, patients with prosopagnosia also have trouble identifying their car among a series of cars, their own clothing, etc.

3. The lesion usually occupies the inferomedial temporo-occipital region, irrigated by cortical branches of the posterior cerebral artery (Damasio and Damasio, 1989; Hudson and Grace, 2000; Tranel and Damasio, 1996). The lesion is usually bilateral, but if unilateral, it is usually right-sided (Wada and Yamamoto, 2000). Lesions in this region also cause an acquired type of color agnosia (achromatopsia or chromatagnosia).

E. Technique to test for agnosias of the body scheme: autotopagnosia (asomatognosia)

1. The concept of a body scheme: One’s brain knows one’s anatomic parts, boundaries, and postures as a grand gestalt called the body scheme or somatognosia (Castle and Phillips, 2002; Coslett et al, 2002; Miller et al, 2001). Even a puppy knows its parts and separates self from nonself. The normal body scheme, such as finger localization (finger gnosia) and right-left orientation, only becomes formally testable in 4- to 6-year-old children and thus illustrates a definite developmental timetable (Reed, 1967).

2. Neuropsychiatric disorders may cause body scheme delusions (Castle and Phillips, 2002). In anorexia nervosa, the person perceives herself as too fat, no matter how emaciated she actually becomes. A person may erroneously perceive normal body parts, such as the nose, breasts, or, in cases of gender dysphoria, the genitalia, as misshapen.

3. Several terms express the concept of somatognosia or its antonym somatagnosia. Topagnosia is the inability to localize skin stimuli. Autotopagnosia means the inability to locate, identify, and orient one’s body parts, that is, body scheme agnosia.

4. Technique to test for two autotopagnosias: tactile finger agnosia and right-left disorientation

a. For identifying the fingers, assign the numbers 1 to 5 to the digits of each of the Pt’s hands, beginning with the thumb, or use names. Then, with the Pt’s eyes closed, randomly touch a digit on the right or left hand and ask the Pt to identify the finger by number or name and whether it is the right or left hand (Reitan and Wolfson, 1993).

i. If the Pt seems to have right-left disorientation, give further commands such as, “Touch your right hand to your left ear,” to verify the deficit.

ii. To further explore right-left disorientation, ask the Pt to point out your own right and left hands and digits by number or name.

iii. The lesion usually occupies the region of the left angular gyrus (posterior parasylvian area). See Gerstmann syndrome, Section III O.

b. Also test the Pt for autotopagnosia by placing a part in one position and asking the Pt to duplicate the position with the opposite extremity, with the eyes closed. For example, elevate the Pt’s arm to a position on one side and ask the Pt to hold it there and to duplicate the position with the opposite extremity.

F. Left-side hemispatial inattention

1. Patients with right parietal lesions often fail to attend to the entire left half of space. Evidence for this unilateral neglect comes from observing that the Pt ignores persons, objects, or any stimuli from the affected side, fails to dress that side, and fails to eat the food from that half of the plate. Such Pts, at least early after an acute lesion, often have anosognosia (see Section G).

2. Technique to test for left-side hemispatial inattention

a. Ask the Pt to draw a cross or any symmetrical figure such as a bicycle wheel with spokes or the face of a clock (Freedman et al, 2000). The Pt will draw the right half of the figure accurately but make mistakes in completing the drawing on the opposite side (Fig. 11-4; Critchley, 1953; Stone et al, 1991).

b. The line bisection test demonstrates left-side inattention better than drawing a clock face (Ishiai et al, 1993). Draw a straight line 20 cm long across a sheet of paper and ask the Pt to make a pencil mark exactly in the center. The Pt with a right parietal lobe lesion makes the mark considerably to the right of the true center because of neglect of the left half of space (Tegner and Levander, 1991).

G. Anosognosia

1. Definition: Josef Babinski (1857–1932) introduced anosognosia to describe a Pt who had a left hemiplegia and left-side sensory loss but who was unaware of his neurologic deficits. Some authors now use anosognosia generically for lack of awareness of any bodily defect. Although highly characteristic on the left side after right parietal lesions, it can affect the right side after left parietal lesions, particularly in the acute phase of the lesion (Stone et al, 1991).

2. Technique to test for anosognosia

a. The Ex, noting a left hemiplegia, asks the Pt whether anything is wrong with the side. The Pt replies No. If the Ex asks whether the Pt can move the left arm, the Pt will reply Yes despite complete hemiplegia (Levine et al, 1991).

b. The most dramatic test for anosognosia is this: Stand on the left side of the Pt’s bed and place the Pt’s hemiplegic arm on the bed alongside the Pt. Lay your own left arm across the Pt’s waist. Ask the Pt to reach over and pick up his own left hand. He will grope across his abdomen, grasp your hand, and hold it triumphantly aloft, never realizing the error.

H. Inattention to double simultaneous cutaneous stimuli

1. Synonyms include sensory suppression, sensory extinction, and sensory inattention. As with agnosias, the sensory pathways from the periphery to and including the primary sensory cortex must be intact, making the phenomenon a test of association cortex. Inattention to bilateral double stimuli occurs with vision (Chapter 3, Section I B 2), hearing (Chapter 8, Section IV H), and touch.

2. Technique to test for tactile inattention to simultaneous bilateral stimuli (double simultaneous stimulation)

a. Inform the Pt that you may touch one or both sides. With the Pt’s eyes closed and using light pressure, brush one or simultaneously both cheeks randomly with the tips of your index finger or wisps of cotton.

b. The Pt reports whatever is felt and should perceive one or both stimuli. Similarly test the dorsum of the hands and then the feet.

c. If the Pt reports only one stimulus after the Ex has applied simultaneous stimuli, the Ex again states, “I may be touching you in more than one place. Don’t let me fool you.” Then alternate, randomly touching only one or both sides, until you determine whether the Pt consistently does or does not feel bilateral simultaneous stimuli.

d. Inattention to simultaneous bilateral stimuli is most prominent after right parietal lobe lesions, in which case the Pt fails to attend to the stimulus on the left (Bender, 1952; Critchley, 1953; Meador et al, 1998; Weinstein and Friedland, 1977). Occasionally, with left parietal lesions, the Pt will not attend to the right side on simultaneous stimulation. After simultaneous stimulation of both sides, the Pt with a right parietal lesion inattends to stimuli from the  right/

right/ left side. (

left side. ( left)

left)

3. Technique to test for inattention to simultaneous unilateral stimuli

a. On one side, simultaneously touch the face and hand several times, and then the foot and hand and face and foot. The person normally reports both stimuli. Parietal lobe lesions impair recognition of both stimuli.

b. Learning-disabled children without gross structural lesions of the brain often suppress double stimulation on one side. Usually the Pt feels the face or foot stimulus and suppresses the hand stimulus.

I. Review of localization of agnosias and loss of discriminative sensory modalities

1. Recite the definition of agnosia and the qualifying requirements.

2. Agnosias generally signify lesions of the association areas that extend from the primary sensory receptive areas or of the thalamocortical circuits of the association areas. The cortex works by thalamocortical and corticothalamic feedback circuits. The association nuclei of the thalamus project to the association areas of the cortex, just as the sensory nuclei of the thalamus project to the respective sensory cortices. The thalamic projections to primary sensory cortex run courses different from those for the association pathways and can be preserved when lesions interrupt the association circuitry. Interruption of a feedback circuit at any point may cause defects similar to lesions of only the cortical component of the circuit. Thus thalamic lesions may cause hemineglect, some agnosias, and aphasia (Bruyn, 1989). In these instances, the sensory pathways are at least partly preserved, as the definition requires.

3. Although right parietal lesions most commonly cause contralateral hemiinattention, lesions of either parietal lobe regularly cause loss of discriminative modalities contralaterally, such as astereognosis, agraphognosia, atopagnosia, and loss of two point discrimination (Fig. 11-9). The primary modalities of touch, pain and temperature, and vibration remain more or less intact with cortical lesions. Lesions of infracortical pathways or in the periphery more commonly significantly impair these modalities.

4. For autotopagnosias such as finger agnosia and right-left disorientation, the relevant association area is the left posterior parasylvian area. In this case, a unilateral lesion causes bilateral deficits of the body scheme. Lesions of the left posterior parasylvian area cause, in addition to bilateral finger agnosia and right-left disorientation, dyscalculia and dysgraphia (see Gerstmann syndrome).

5. In summary, lesions of either parietal lobe may cause contralateral loss of astereognosis and other discriminative modalities, but hemispatial inattention and anosognosia are more common with  right/

right/ left parietal lobe lesions. (

left parietal lobe lesions. ( right)

right)

6. In contrast, finger agnosia and right-left disorientation are more common with  right/

right/ left posterior parasylvian lesions. (

left posterior parasylvian lesions. ( left)

left)

BIBLIOGRAPHY · Agnosia

Bender M. Disorders in Perception, with Particular Reference to the Phenomena of Extinction and Displacement. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas; 1952.

Bender M, Stacy C, Cohen J. Agraphesthesia: a disorder of directional cutaneous kinesthesia or a disorientation in cutaneous space. J Neurol Sci. 1982;53:531–555.

Bruyn RPM. Thalamic aphasia: a conceptual critique. J Neurol. 1989;236:21–25.

Castle DJ, Phillips Ka. Disorders of Body Image. Petersfield, United Kingdom: Wrightson Biomedical; 2002.

Coslett HB, Saffran EM, Schwoebel J. Knowledge of the human body. A distinct semantic domain. Neurology. 2002;59:357–363.

Critchley M. The Parietal Lobes. London: Edward Arnold & Co; 1953.

Damasio H, Damasio AR. Lesion Analysis in Neuropsychology. New York, NY: Oxford Univ. Press; 1989.

Freedman M, Leach L, Kaplan E, et al. Clock Drawing: A Neuropsychological Assessment. New York, NY: Oxford Univ. Press; 1994.

Hudson AJ, Grace GM. Misidentification syndromes related to face specific area in the fusiform gyrus. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;69:645–648.

Ishiai S, Sugishita M, Ichikawa T, et al. Clock-drawing test and unilateral spatial neglect. Neurology. 1993;43:106–110.

Levine DN, Calvanio R, Rinn WE. The pathogenesis of anosognosia for hemiplegia. Neurology. 1991;41:1770–1780.

Meador KJ, Ray PG, Day L, et al. Physiology of somatosensory perception. Cerebral lateralization and extinction. Neurology. 1998;51:721–727.

Miller BL, Seeley WW, Mychak P, et al. Neuroanatomy of the self. Evidence from patients with frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 2001;57:817–821.

Reed J. Lateralized finger agnosia and reading achievement at ages 6 and 10. Child Dev. 1967;38:213–220.

Reitan RM, Wolfson D. The Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery. Theory and Clinical Interpretation. 2nd ed. Tucson, AZ: Neuropsychology Press; 1993.

Stone SP, Wilson B, Wroot A, et al. The assessment of visuo-spatial neglect after acute stroke. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1991;54:345–350.

Tegner R, Levander M. The influence of stimulus properties on visual neglect. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1991;54:882–887.

Tranel D, Damasio AR. Agnosias and apraxias. In: Bradley WG, Daroff R, Fenichel GM, Marsden CD, eds. Neurology in Clinical Practice. Principles of Diagnosis and Management. 2nd ed. Boston, MA: Butterworth Heinemann; 1996, Chap. 16, 119–130.

Wada Y, Yamamoto T. Selective impairment of facial recognition due to a haematoma restricted to the right fusiform and lateral occipital region. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;71:254–257.

Weinstein EA, Friedland RP, eds. Hemi-attention Syndromes and Hemisphere Specialization. Advances in Neurology. Vol 18. New York, NY: Raven; 1977.

J. Apraxia

1. Definition of apraxia: The ability to execute a voluntary act is called praxia (praxis = action, as in practice). By negating praxia, the ability to act, we describe apraxia, the inability to act. Apraxia means the inability to perform a voluntary act even though the motor system, sensory system, and mental status are relatively intact. Learn this definition.

2. Formal criteria to distinguish apraxia from other motor defects

a. The Pt’s motor system is sufficiently intact to execute the act.

b. The Pt’s sensorium is sufficiently intact to understand the act.

c. The Pt comprehends and attempts to cooperate.

d. The Pt’s previous skills were sufficient to perform the act.

e. The Pt has an organic cerebral lesion as the cause of the deficit.

f. In summary, the Pt must comprehend the act, cooperate in attempting it, and have a motor system sufficiently intact to execute the act. These requisites exclude Pts with paralysis or functional mental illnesses, such as hysteria or negativism, profound dementia, and mental retardation, to whom apraxia is not meant to apply.

g. If the definition and conditions for diagnosing apraxia causes the strange feeling of repeating a previous experience (the déjà vu of anterior temporal lobe lesions), we are on the right track. Review frame II B 2 that defines agnosia.

3. Distinction between apraxia and other motor deficits: Apraxic Pts are often unaware of their deficits and may do an act automatically that they cannot do on command. For example, apraxic Pts may fail to stick out their tongue and lick their lips on command but may then lick their lips automatically. The Pt may fail to make a fist when asked in close the fingers but may automatically grasp an object, such as a spoon.

a. With pyramidal lesions, the paralysis precludes doing the act voluntarily or automatically, thus violating a necessary condition that the motor system be fairly intact. The paralyzed Pt may also have apraxia, but the paralysis prevents its recognition.

b. The Pt with a cerebellar lesion retains the ability to perform an act but cannot perform it smoothly.

c. With basal motor nuclei lesions, involuntary movements or rigidity impede down the act, but the sequence of the act remains possible.

K. Technique to test for common apraxias

1. The Ex tests for apraxia almost inadvertently in giving routine commands such as: “Stick out your tongue.” “Make a fist.” “Walk across the room.” These commands disclose tongue, hand, and gait apraxias, respectively.

2. For formal testing, the Ex makes special verbal requests and, if that fails, demonstrates acts for the Pt to pantomime.

3. Face-tongue (bucco-facial) apraxia: Ask the Pt to protrude the tongue and move it up, down, right, and left and lick the lips. Ask the Pt to act as if blowing out a match or sucking on a straw. If verbal instruction fails, try miming.

4. Arm (ideomotor) apraxia: More complicated apraxias such as ideomotor apraxia require sequential actions. Ask the Pt to demonstrate a sequence: how to use silverware, thread a needle, strike a match and light a candle, and use a key to lock and unlock a lock, or use scissors or other tool. The Ex may provide the actual materials or tools or may have the Pt imitate gestures and hand positions (Heilman and Valenstein, 1979; O’Hare et al, 1999).

5. Constructional apraxia: Ask the Pt to copy geometric figures (a cross, interlocking pentagons, or clock face) or construct them out of matchsticks.

6. Dressing apraxia: Watch the Pt try to get dressed. The apraxic Pt cannot orient the clothes to put them on and gets the shoes on the wrong foot. Usually this is associated with right parietal lesions and is part of the neglect syndrome.

7. Gait apraxia (Bruns ataxia): Ask the Pt to rise and walk.

8. Writing and speaking apraxia (aphasia): Explained in the next section.

9. Global apraxia in children: The child lags in motor skills such as chewing, swallowing, dressing, tying shoelaces, buttoning, and the use of cutting tools such as a knife and fork and scissors.

L. Patient analysis for identification of constructional and dressing apraxia

1. Medical history: A 67-year-old right-handed salesman with a college education had noticed dizziness, fatigue, and blurring of vision for 3 months. Three weeks before hospitalization, he began to have right frontal headaches. For 1 week, he had noticed weakness and slight numbness of his left extremities. Although he appeared dull and apathetic and did arithmetic poorly, his sensorium was otherwise intact.

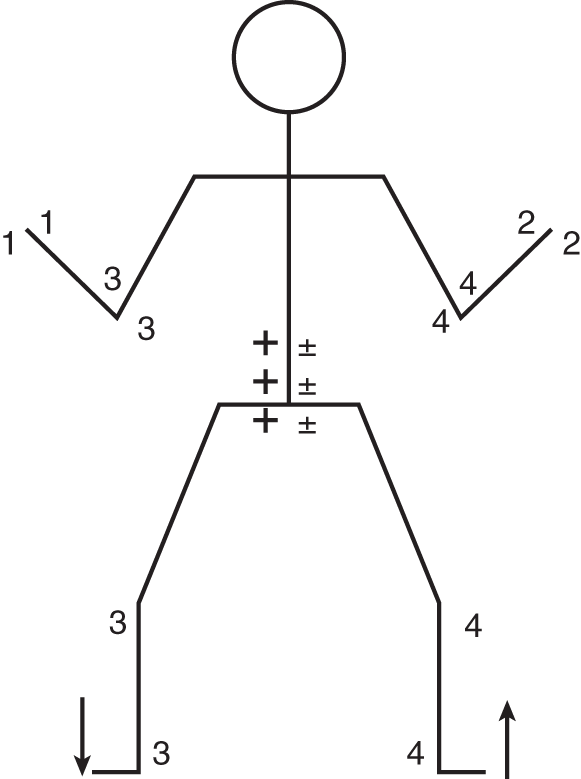

2. Motor examination: The Pt could walk, but movements on the entire left side were moderately weak, except for normal frontalis and orbicularis oculi strength. He had no atrophy, tremor, dystaxia, or involuntary movements. Manipulation of the Pt’s left extremities showed an initial catch followed by yielding of the part. Figure 11-2 shows the reflex pattern.

FIGURE 11-2. Reflex figurine of the patient.

a. His facial weakness was  upper motoneuron/

upper motoneuron/ lower motoneuron. (

lower motoneuron. ( upper motoneuron)

upper motoneuron)

b. Manipulation of the Pt’s left extremities showed a type of hypertonus called _________

c. Integrate the total information from the physical examination and Fig. 11-2 to summarize the motor deficits and reflex changes detected thus far:

_________

_________

3. Sensory examination

a. Although the Pt could feel light touch on either side, perhaps less well on the left, he consistently failed to report a left-side stimulus when the Ex simultaneously touched both of the Pt’s hands. He failed to report left-side stimuli when simultaneous sound stimuli were presented. This type of sensory deficit is called sensory _________

b. On the line bisection test, the Pt made the mark to the right of the true center.

c. The Pt recognized coins or a safety pin by vision or when placed in the right hand, but not in the left. The left-side deficit is called _________

d. He had difficulty recognizing numbers traced on the left palm, a defect called _________

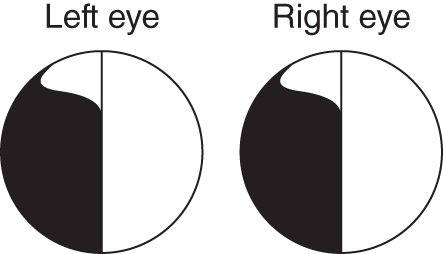

e. The visual field defect shown in Fig. 11-3 is called

_________

FIGURE 11-3. Visual fields of the patient.

f. Would the Pt perceive simultaneous stimuli presented in the upper part of the left visual field and the temporal half of the right visual field?  Yes/

Yes/ No. (

No. ( No)

No)

g. Could you correctly say that the Pt had visual agnosia for the entire left half of space?  Yes/

Yes/ No. Explain.

No. Explain.

_________

_________ No) (The Pt had a left incomplete homonymous hemianopia, which means blindness in the left visual field. His lesion had to interrupt the optic pathway to the visual cortex. Because the lesion interrupted the modality pathway or the defect does not qualify as agnosia.)

No) (The Pt had a left incomplete homonymous hemianopia, which means blindness in the left visual field. His lesion had to interrupt the optic pathway to the visual cortex. Because the lesion interrupted the modality pathway or the defect does not qualify as agnosia.)

4. Testing for constructional apraxia

a. As part of the test battery (to be described), the Pt named and tried to copy several geometric figures. Study his efforts in Fig. 11-4.

b. In each instance, the Pt failed to complete the  right/

right/ left side of the figure. To appreciate the limitation of the defect to the left side, draw a vertical line to divide each of the Pt’s figures exactly into right and left halves. (

left side of the figure. To appreciate the limitation of the defect to the left side, draw a vertical line to divide each of the Pt’s figures exactly into right and left halves. ( left)

left)

c. This Pt, a college graduate, failed to complete a simple voluntary act such as copying geometric figures. Yet he understood the task and had normal motility of his right hand. At first thought, you might suspect that his left hemianopsia caused the difficulty, but experience shows that Pts with only hemianopsia complete such figures. Because the present Pt met all of the criteria for apraxia, his deficit in the construction of geometric figures is called constructional apraxia. He also could not construct figures from match sticks. In Pts with left hemisphere lesions, the type of constructional apraxia for drawing or copying involves the gestalt of the figure, or both sides, rather than the left half, as in the Pt just described.

FIGURE 11-4. Stimulus figures for patient to name and copy. In the right-hand column are the attempts of the patient to copy the figures after he had named them correctly.

5. Testing for dressing apraxia: At the end of the NE, the Ex handed the Pt his pajama top. Ordinarily, if the Pt is disabled, the Ex helps the Pt dress. Watching this Pt dress constituted an essential part of the NE. He repeatedly fumbled the garment while trying put it on, demonstrating dressing apraxia.

6. Localizing significance of dressing apraxia and left-side constructional apraxia

a. Dressing apraxia and constructional apraxia, in which the Pt fails to complete the left side of figures, occur most frequently with a right posterior parietal lesion (Critchley, 1969; Joynt and Goldstein, 1975; Weinstein and Friedland, 1977). Check the finding(s) that would most likely accompany a right posterior parietal lesion:  sensory inattention/

sensory inattention/ anosognosia/

anosognosia/ bilateral finger agnosia/

bilateral finger agnosia/ right-left disorientation. (

right-left disorientation. ( sensory inattention;) (

sensory inattention;) ( anosognosia)

anosognosia)

b. Ideomotor apraxias occur with lesions of the language-dominant hemisphere, almost always the left (Heilman et al, 2000; Meador et al, 1999). Usually the Pt with ideomotor apraxia also has aphasia (Papagno et al, 1993). Both hands are usually affected, although the lesion is unilateral.

7. Summary of the Pt’s clinical deficits

a. Motor: Mild spastic, hyperreflexic left hemiparesis with an extensor toe sign. Severe constructional and dressing apraxia.

b. Sensory: Slight left hemihypesthesia and hemihypalgesia, left-side astereognosis, left-side tactile and auditory inattention, and incomplete left homonymous hemianopia.

8. Localizing significance of the Pt’s neurologic signs: How to “think circuitry.”

a. This Pt’s hemiparesis implicates involvement of the _________ pyramidal)

pyramidal)

b. To cause the hemiparesis, the pyramidal lesion would have to involve some level between the motor cortex and the upper cervical cord. What motor finding locates the pyramidal tract lesion at or rostral to the pons?

_________

_________

c. The agnosia and apraxia implicate a lesion at the level of the  brainstem/

brainstem/ sensorimotor cortex/

sensorimotor cortex/ association cortex or its intracerebral connections. (

association cortex or its intracerebral connections. ( association cortex or its intracerebral connections)

association cortex or its intracerebral connections)

d. The particular types of agnosia and apraxia implicate a lesion of the  right/

right/ left/

left/ both cerebral hemisphere(s), mainly in the

both cerebral hemisphere(s), mainly in the  frontal/

frontal/ parietal/

parietal/ occipital/

occipital/ temporal region. (

temporal region. ( right;

right;  parietal)

parietal)

9. The principle of parsimony: Although a brainstem lesion might account for the Pt’s left hemiparesis and mild hemihypesthesia, his apraxia and agnosia require a lesion of the dorsolateral cerebral wall in the parietal region. Thus, although we might postulate separate lesions at the levels of the brainstem and cerebral wall, we now invoke a most important principle in diagnosis, the principle of parsimony. Called Occam razor (William of Occam, 1280–1349), this principle requires us to seek the simplest explanation: a single lesion and a single diagnosis. In other words, we seek the simplest, the most parsimonious, explanation. Thus, if a single lesion caused the hemiparesis, hemihypesthesia, and agnosia-apraxia, it involves the  spinal cord/

spinal cord/ brainstem/

brainstem/ dorsolateral cerebral wall. (

dorsolateral cerebral wall. ( dorsolateral cerebral wall)

dorsolateral cerebral wall)

a. The hemianopia indicates a lesion at some level along the visual pathway. Review the visual pathway in Fig. 3-4 and the course of the optic radiation through the lateral cerebral wall in Figs. 3-5 and 3-6. Hemianopia implicates a lesion:

(1) In the retina or optic nerve

(1) In the retina or optic nerve

(2) In the anterior part of the temporal lobe

(2) In the anterior part of the temporal lobe

(3) Between the optic chiasm and the visual cortex of the calcarine fissure (

(3) Between the optic chiasm and the visual cortex of the calcarine fissure ( (3))

(3))

b. Applying the principle of parsimony, could the previously postulated lesion of the dorsolateral cerebral wall in the parietal lobe also interrupt the optic pathway? If so, where? Yes/

Yes/ No. Explain.

No. Explain.

_________

_________ Yes) (The geniculocalcarine tract runs through the deep white matter of the parietotemporal region. See Fig. 3-5A.)

Yes) (The geniculocalcarine tract runs through the deep white matter of the parietotemporal region. See Fig. 3-5A.)

c. The preservation of a bit of the superior visual field indicates that the most inferior axons of the geniculocalcarine tract are intact. The lesion that causes the partial hemianopia involves the superior part of the geniculocalcarine tract, which runs through the parietal lobe and adjacent temporal and occipital lobes (Fig. 3-5A).

d. In addition to the agnostic-apraxic and visual field deficits, implicating the posterior inferior parietal area, the slight hemihypalgesia and hemihypesthesia implicate the primary somesthetic receptive region of the _________ right/

right/ left _________

left _________ right; parietal)

right; parietal)

e. The mild left hemiparesis implicates the motor area located in the right _________

f. The left-side auditory inattention implicates the auditory association area in the  anterior/

anterior/ posterior part of the

posterior part of the  right/

right/ left temporoparietal region. (

left temporoparietal region. ( posterior;

posterior;  right)

right)

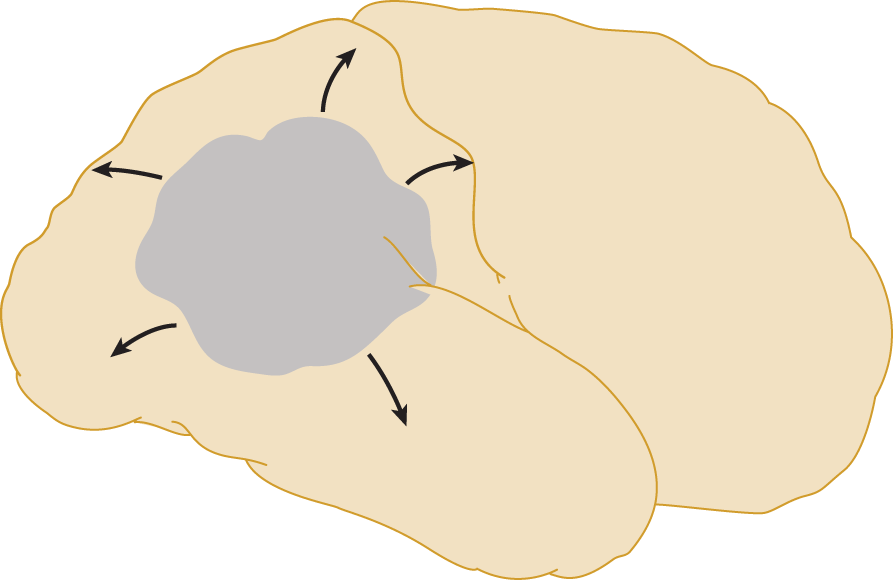

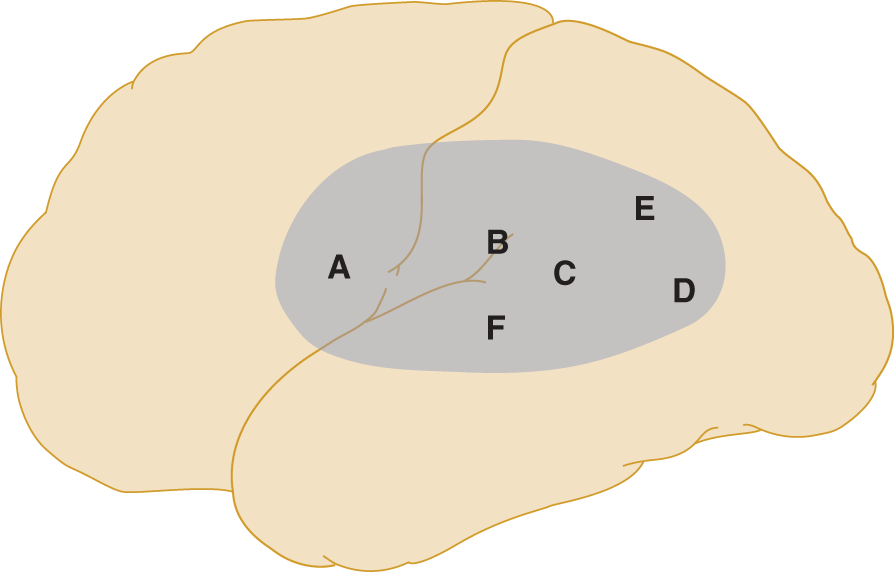

g. Shade Fig. 11-5 to show the presumed extent of the lesion. Use dark shading for the regions that have produced the severest or most complete deficits and lighter shading for the regions responsible for the lesser deficits. Frame L 7, earlier, summarizes the deficits that require a localizing explanation.

FIGURE 11-5. Blank of right cerebral hemisphere to be shaded to show the presumed location of the patient’s lesion.

10. Neuropathologic considerations

a. By causing edema and compressing vessels, focal lesions may impair the function of surrounding brain tissue. The severest signs usually reflect the site of maximum tissue damage and, therefore, best predict the lesion site. The Pt’s severest defects, the hemianopia and dressing and constructional apraxia, suggest maximum damage to the right posterior parasylvian area, with less involvement of the sensorimotor cortex of the paracentral region.

b. Radiographic examination showed a mass in the predicted right parieto-occipital region. Craniotomy and biopsy disclosed a large, expanding neoplasm, a glioblastoma, causing pressure on the surrounding brain. The surgeon removed the right occipital lobe, providing internal decompression. Postoperatively, the left hemiparesis disappeared, suggesting that pressure and edema from the neoplasm had caused it, rather than direct extension of the neoplasm to the paracentral area (Fig. 11-6).

c. Ordinarily, a Pt with a lesion in the right posterior parasylvian area might also have anosognosia. The Pt failed to show it before the operation, but afterward he failed to recognize that he had a left hemianopia. Anosognosia occurs more commonly with large, acute lesions, such as infarcts, than when lesions evolve relatively slowly, as with neoplasms.

FIGURE 11-6. Lateral view of the right cerebral hemisphere to show the actual location of the patient’s lesion, as determined at autopsy examination. The arrows indicate the surrounding edema of the hemisphere, which led to clinical signs such as hemiparesis, implicating damage to tissue beyond the immediate confines of the neoplasm.

BIBLIOGRAPHY · Apraxia

See end of Aphasia section.

III. APHASIA: AGNOSIA AND APRAXIA OF LANGUAGE

A. Survey of the levels and types of speech disturbance

1. Communicative speech consists of words arranged according to the rules of grammar and syntax and invested with prosody. Many factors—culture, thought disorders such as schizophrenia, neuroses, and structural lesions of the brain—alter the communicative content and emotional connotation of speech.

2. We may now distinguish four levels of disturbed speech production: dysphonia, dysarthria, dysprosody, and dysphasia. At the lowest level, dysphonia consists of a disturbance in, or a lack of, the production of sounds in the larynx. Dysarthria means a disorder in articulating speech sounds. Then come the dysprosodies that consist of scanning speech (cerebellar), plateau speech (basal motor nuclei/Parkinsonian), and stuttering, cluttering, and absence of emotional inflections (cerebral). At the highest level, dysphasia means a disturbance in the understanding or expression of words as symbols for communication. Review (or if you wish, write out) the definitions of these terms and check your definitions against the ones given in Section III of the Standard NE.

3. One end of the neuropsychiatric spectrum of speech disorders consists of little or no speech, called mutism or aphonia. Varieties of mutism include deaf mutism, elective mutism, psychogenic mutism, autism and other retardation syndromes, catatonia, depression, postictal state, and cerebellar mutism following posterior fossa surgery (Gordon, 2001). Akinetic mutism or bradylalia may follow bilateral lesions of the thalamus, basal motor nuclei, or upper brainstem. Absence of speech or delayed speech in a child always raises the question of intellectual developmental disorders, autism spectrum disorder, or deafness.

4. The other end of the speech spectrum consists of too much speech, logorrhea (pressure of speech or an increase in the amount and rate of speech, as seen in mania), fluent aphasia, cluttering, echolalia, vocal tics, and finally the compulsive talker, the conversational narcissist who never has a silent thought and articulates every bit of trivia that comes to mind.

B. Definition of aphasia

1. Literally, a = lack of, and phasis = speech. Aphasia means the inability to understand or express words as symbols for communication, even though the primary sensorimotor pathways to receive and express language and the mental status are relatively intact (Video 11-4). Learn this definition. The definition excludes language disturbances caused by functional mental illness, intellectual developmental disorder, dementia, blindness, deafness, stuttering, or neuromuscular disease.

Video 11-4. Wernicke aphasia due to cardioembolic (nonvalvular atrial fibrillation) infarction.

2. The purist would reserve aphasia for total loss of language, and dysphasia for partial loss, but clinicians use the prefixes a- and dys- interchangeably.

C. The four avenues for communication by language

1. A moment’s introspection discloses four major avenues of language. We express language by speaking or writing, and we receive it by reading or listening. Thus, we speak/write and listen/read. Additional modes of communication include Morse code, Braille, sign language, facial expression, pantomime, not to mention “body language” and the information conveyed by clothing, tattoos, hair style, and makeup.

2. Some Pts with brain lesions, although neither deaf nor blind, fail to understand the meaning of spoken or written words. The general term for failure of a mentally intact Pt with intact sensory pathways to understand the meaning of a stimulus is _________

3. Some Pts with brain lesions produce the wrong syllables, wrong words, or even no words when attempting to speak or write. The general term for failure of a mentally intact, nonparalyzed Pt to execute such voluntary acts is _________

4. We call apraxia for writing or speaking expressive or motor aphasia.

5. Recite the four ordinary avenues for receiving and expressing language: _________

D. Volitional, propositional, or declarative speech versus automatic or exclamatory speech

1. Some speech, exclamatory speech, communicates the emotional state of the moment, rather than ideas. On stubbing a toe, we automatically exclaim, “Ouch!” Exclamations, particularly expletives, erupt spontaneously, unwilled, without deliberation or forethought, although we can also produce them volitionally. Patients with Tourette syndrome may produce involuntary exclamations as vocal tics.

2. In contrast, we communicate ideas by volitional declarations or propositions. The sentence may consist of a simple declaration, “The fire engine is red,” or a distinct proposition, “Fire engines ought to be red.” A proposition states something for analysis that was, is, or could be. A proposition is preeminently volitional, planned, and often crafty. Aphasics lose declarative and propositional speech but tend to retain some exclamatory speech. Thus, after struggling but completely failing to produce a propositional statement, the aphasic Pt sighs in anger and exclaims spontaneously and with perfect clarity, “Oh damn, I can’t.” Yet when asked to repeat the automatically uttered sentence, the Pt fails again because it now has become propositional or volitional speech. In analogy, recall that in pseudobulbar palsy, the Pt loses volitional movements but retains or even shows exaggerated, automatic laughing or crying. These facts demonstrate that the brain uses different circuits for volitional behavior, as contrasted to emotional or more automatic behavior (Bookheimer et al, 2000). In general, aphasics also retain humming and singing better than spoken language.

E. Clinical testing for aphasia

1. Detecting aphasia during the history: Aphasia testing begins with the history. You will readily detect gross defects in language reception or expression. The mildly aphasic Pt produces less than the expected amount of written and spoken language. Although the Pt’s conversation remains goal directed, the Pt fails to hit the nail on the head with crisp, logical statements. The speech may degenerate to circumlocutions, platitudes, and clichés dredged more from memory than composed of volitional, novel, or artful word combinations. Less commonly, the aphasic Pt becomes wordy, as if by preempting the conversation, the Pt can prevent the other person from saying something that the Pt cannot understand, or the Pt may show a gratuitous redundancy in searching for le mot juste (just the right word). The clues to dysphasia are as follows:

a. Searching for words, pauses, and hesitations.

b. Substitution of the wrong words or phonemes.

c. Poverty of speech or the converse, excessive production of sounds that resemble words but fail to communicate.

d. Puzzlement and hesitations in response to ordinary statements made in the course of conversation.

e. Loss of intonation and prosody.

f. Frequent dysarthria.

g. Irritation or distress at the inability to communicate.

2. Usual operational steps in examining the Pt for aphasia

a. During the give and take of the history, listen for word choice, in particular word substitutions, a searching for words, articulation, hesitations, prosody, and the quantity of speech.

b. Test ability of the Pt to repeat words spoken by the Ex.

c. Test word comprehension by questions and commands.

d. Show the Pt common objects to name.

e. Have the Pt write a sentence to dictation.

f. Have the Pt read and interpret a sentence, a paragraph, or symbols.

3. Formal aphasia screening tests: The Ex uses a formal and comprehensive battery (eg, Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination [Goodglass et al, 2000], Western Aphasia Battery [Shewan and Kertesz, 1980]) to test the Pt’s ability to read, write, name things, repeat words and sentences, and copy them to dictation and to follow written and verbal commands. The indication for the test battery is a suspicion raised during the history or NE of a brain lesion (Damasio, 1992).

F. General classification of aphasia

1. Expressive and receptive aphasia: Traditionally, neurologists have classified aphasia as receptive, expressive, or mixed expressive-receptive aphasia, also called global aphasia. Most Pts have mixed expressive and receptive language deficits, with at least some impairment of all four avenues of language. In judging relative loss of receptive and expressive language, recall that the active expression of language requires more effort than receiving it. Therefore, aphasics typically comprehend language better than they express it, just as children do as they learn to talk (Klein et al, 1992).

2. Fluent and nonfluent aphasia: Many researchers classify aphasia as fluent or nonfluent, depending on the amount of speech sounds produced and combine these terms with the traditional expressive-receptive scheme (Goodglass, 1993; Table 11-4).

TABLE 11-4 • Classification of the Aphasias

Type of aphasia |

Fluency |

Understands |

Repetition |

Naming |

Lesion location |

Broca |

Poor; effortful |

Good |

Poor |

Poor |

Left posterior inferior frontal operculum (Fig. 11-7A) |

Wernicke |

Good; fluent sounds but “word salad” |

Poor |

Poor |

Poor |

Posterior parasylvian, temporal operculum (Figs. 11-7F and 11-7C) |

Conduction |

Good; poor articulation |

Good |

Poor |

Poor |

Posterior parasylvian (Figs. 11-7C and 11-7B–11-7E) |

Transcortical motor |

Poor |

Good |

Good |

May be normal |

Frontally (Fig. 11-7A) and superiorly, extending inward to striatum |

Transcortical sensory |

Good |

Poor |

Good |

Usually normal |

Parietal, temporal (Fig. 11-7C) involving the thalamocortical circuit |

Global |

None or scanty; or expletives only |

Very poor |

Very poor |

Very poor |

Entire parasylvian area (Figs. 11-7A–11-7F) |

SOURCE: Data from Damasio AR. Aphasia. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:531-539. |

|||||

G. General localization of lesions causing aphasia

1. Localization to the left hemisphere

a. The lesion that causes aphasia occupies the left cerebral hemisphere in almost all right-handed and most left-handed Pts. Therefore, we designate the left hemisphere as usually dominant for language. Operationally, in designating a hemisphere as dominant for language, we mean that a lesion of that hemisphere will result in aphasia, that physiologic tests, such as cortical stimulation (Penfield and Roberts, 1959), electrocorticography, and that functional scans will document activation of one or more zones of the left hemisphere during language tasks. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies have indicated that 96% of right-handers are left hemisphere dominant, 76% of left-handers are left hemisphere dominant, and 10% of left-handers are right hemisphere dominant, at least for silent word generation (Pujol et al, 1999).

b. Normal hemispheres are anatomically asymmetric, with the left hemisphere larger than the right, particularly the planum temporale. The planum is a submerged area between the transverse temporal gyri (the primary auditory sensory cortex) and the posterior end of the Sylvian fissure.

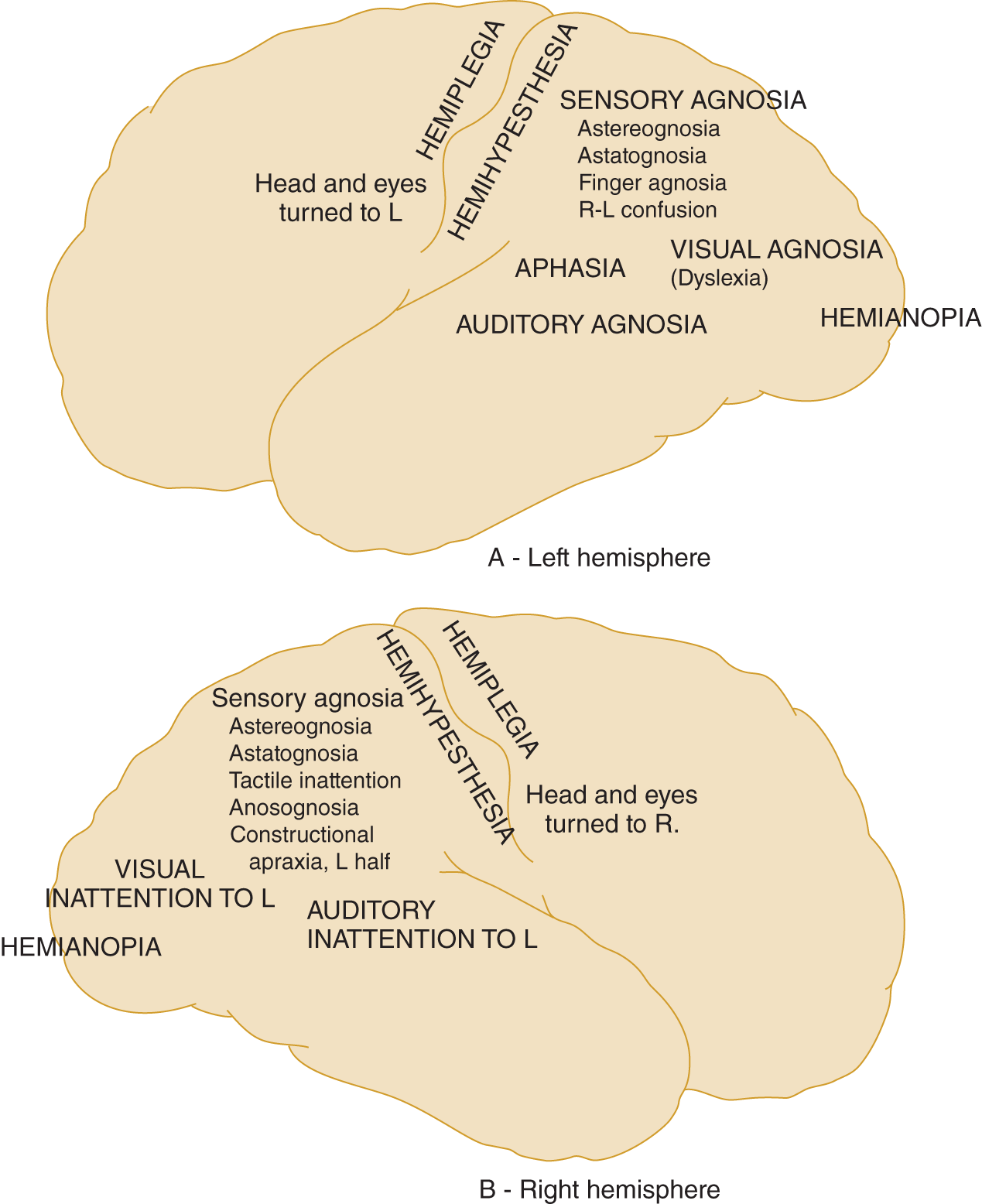

c. Localization within the dominant hemisphere: The lesion usually involves the parasylvian region of the left hemisphere (Fig. 11-7).

FIGURE 11-7. Lateral view of the left cerebral hemisphere to show the expected lesion sites in aphasic patients.

d. The lesion may extend into the subjacent deep white matter and into the caudate-putamen or the thalamus, thus interrupting the connections of the parasylvian cortex with the deep nuclear masses (Bruyn, 1989; Damasio, 1992; Kreisler et al, 2000; Mega and Alexander, 1994). Uncommonly, mostly in left-handers, the lesion occupies the homologous regions of the right hemisphere.

e. The clinical features of the aphasia fairly well predict the site of the lesion within the aphasiogenic zone depicted in Fig. 11-7. The lesions that cause expressive aphasia are more forward, toward the anterior inferior frontal region, and the lesions causing receptive aphasia are more posterior, toward the parieto-occipito-temporal junction (posterior parasylvian area; Brazis et al, 2001).

H. Broca aphasia (motor aphasia, or nonfluent aphasia)

1. Clinical features

a. The nonfluent aphasic Pt speaks telegraphically, sparsely, and slowly—hence, the term nonfluent (Mohr et al, 1978). The Pt has difficulty in word finding and naming. The Pt may use some nouns and verbs but omits the small connecting words, conjunctions such as but, or, and and, and articles such as a, an, or the, and prepositions. The Pt says, “I go house,” instead of “I go to the house.” In fact, as an excellent test sentence, ask the Pt to repeat “No if’s, and’s, but’s, for’s, or or’s.”

b. The Pt fails to make associations, such as naming the manufacturers of automobiles or naming a number of objects that are red.

c. The Pts with Broca aphasia fails to inflect and modulate the normal rhythms of speech and thus displays one form of dysprosody.

d. The Pt with Broca aphasia also has difficulty writing, suggesting that the posterior inferior part of the frontal lobe mediates speaking and writing.

e. Importantly, the Pt retains the ability to audit language and to read, but lacks the ability to repeat sentences.

2. Lesion site for Broca aphasia: The lesion occupies the anterior part of the aphasic zone, in the posterior inferior part of the frontal lobe (Broca area, site A in Fig. 11-7). This region abuts on the classic motor area, in harmony with the predominantly motor function of this region. Because of the inverted homunculus in the motor strip, the speech area abuts on the face area of the primary motor cortex. Thus, a right-side upper motoneuron facial palsy, if not a frank right hemiplegia, frequently accompanies Broca aphasia.

I. Wernicke aphasia (receptive aphasia, fluent aphasia)

1. Clinical features: In direct contrast to Broca aphasia, the fluent aphasic produces plentiful but garbled sounds, perhaps best described as a “word salad” or “word potpourri.” The substitution of erroneous words or parts of words and phonemes (paraphasia) robs the speech of meaning. Even so, the jargon may retain prosody, rhythm, and inflection, thus sounding like speech but deficient in meaning (Video 11-4). Thus, the term fluent aphasia, implying fluent communication is almost an oxymoron. Children also may have fluent aphasia.

2. Patients with fluent aphasia lose the ability to audit their own words and the words of others and often fail to realize the severity of their deficit in expression. They cannot use their auditory feedback to monitor or correct their own errors in word production. To appreciate the experience of a Pt with medication-induced Wernicke aphasia, read Lazar et al (2000).