Left: Francis Alleyne, active 1774–1790. Margot Wheatley. 1786.

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection. B1981.25.15.

Dear Reader,

Welcome to The American Duchess Guide to 18th Century Beauty, wherein we take you on a journey of Georgian style as regards the head and shoulders. We realized, when we wrote The American Duchess Guide to 18th Century Dressmaking, we presented four of the most common styles of eighteenth-century gowns along with the millinery needed to complete each outfit for the 1740s, 1760s, 1780s and 1790s. While the hair and makeup in the first book were done using period-correct products and methods, we never discussed them in the book. We felt the absence of that information, as your hair and makeup are both essential to achieving that “stepped out of a portrait” appearance.

Georgian hairstyling, particularly in the last half of the eighteenth century, is of particular importance and interest to those re-creating this period. It is difficult to imagine Marie Antoinette without her famously tall hair, defying gravity. It has come to define the entire eighteenth century in pop culture today. So, with this book, we wanted to explore the wonderful world of eighteenth-century beauty and hair. On this journey, you will learn the historically accurate methods of dressing and beautifying the hair and face, the recipes and techniques to create the tools and products needed and a selection of millinery to top it all off.

There are a great many myths and mysteries surrounding makeup and hairstyling of this period. Our intent with this book is to present a correct picture of how women in the last half of the eighteenth century cared for their hair and complexions. Through myriad primary documents, close interpretation of imagery, inspection of original artifacts and ongoing experiments in re-creating the tools and techniques of the Georgian hairdresser, we can present to you here a much clearer, commonsense routine.

In this book, you will learn about eighteenth-century hair care and hygiene and how the methods and products used in the toilette made possible all of these sculptural coiffures. We then provide you with the recipes and step-by-step instructions to create these hairstyles yourself in the historically accurate method, along with fun millinery patterns to decorate your new style and finish your look perfectly.

We had a lot of fun writing this book, and we think that it shows in the pages to follow. While we strive to use period-correct terms and solid references throughout the projects, we were seldom able to find a definitive name for a hairstyle or cushion. They were either nameless or called many different things in fashion plates. So in the spirit of the French magazines, we have bestowed our own whimsical names on these creations. Be advised that the names are not historically specific or correct unless otherwise noted.

Now, with that, hold on to your comb, because your adventure in artifice starts now!

Francis Wheatley, 1747–1801. Mrs. Barclay and Her Children. 1776–1777. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection. B1977.14.124.

The American Duchess Guide to 18th Century Beauty is several books rolled into one. Here you will find a cookbook, a sewing guide and a hairstyling manual. Each of the sections works together to supply you with the tools, materials, skills and decorations needed to complete your Georgian-era ensemble beyond-the-dress.

In Part 1, you’ll find recipes and instructions for making the tools of your toilette. These are original eighteenth-century recipes taken from Toilet de Flora, Plocacosmos and other primary sources. Each recipe yields a lot of product, so you may wish to halve or even quarter the weights and measures.

Part 2 deals with the hairstyles from 1750 to 1780 and focuses on sculpting hair on or around a cushion. If you’re looking for a tall hairstyle to rock your best Marie Antoinette impression, this is the section for you.

Part 3 is all about the different types of curls and frizz worn in the 1780s and 90s. We demonstrate four different curling techniques: crape, papillote curls, heat-set with a small curling iron and a wet-set with pomatum. Experiment with the curling method that works best for your hair type.

We have made every effort to address different hair lengths, types and textures. Please see here for notes and advice on working with pomade, powder and your hair type. While the specific date of the style may not be what you need for your ensemble, the techniques for working with the hair are the same.

As always, there is variation and transition in styling. We may show a style done with long straight hair, but this does not mean the same style cannot be done accurately with curly hair, hairpieces or wigs. If we show a smooth chignon at the back, it does not mean you cannot choose a braided chignon instead. Study fashion plates and paintings to determine what was trendy in your chosen time frame.

No hair? Short hair? No problem. Georgian women made use of various hairpieces, blending their own hair into the carefully-matched additions, even if their natural hair was quite short. In the pages to follow, we include instructions on how to make your own toupee, chignon and curls or “buckles.” All of these are incredibly useful for the modern woman!

We experimented with different stuffing options for our cushions, all of which would have been available in the period. Each stuffing material has benefits and drawbacks. Cork is a bit tricky to work with because it can spill everywhere and isn’t as good at filling out the space in the cushions. Wool roving, while easy to find and use, is really difficult to pin through. Horsehair is the best to work with, easy to pin through but can be a bit itchy. [1] Experiment with the different options to decide what works best for you. [2]

All of our cushions are made from wool knit. In addition to being a historically accurate fabric, wool knit is easy to pin through, blends better with hair and helps hold hair in place while styling.

Eighteenth-century cosmetic recipes are interesting. We have elected to make some minor changes due to allergen issues and the availability of ingredients. All changes we made are noted in the recipes. We also strongly suggest that you do a spot test with any essential oils or ingredients to which you may be allergic.

All of the gridded patterns in this book use a 1-inch (2.5-cm) grid scale. You can scale up the patterns on a computer, with a projector or by hand using 1-inch (2.5-cm) grid paper. None of the patterns include seam allowance, but in general we recommend adding ½ inch (1.2 cm) to turn and stitch for a ¼-inch (6-mm) finished hem.

Please note that the hair cushions, caps and other accessories are sized specifically for the hairstyle shown. It is important not to mix your time periods without altering the patterns for the accessories. For example, avoid pairing the very tall 1770s calash with the very short 1750s Coiffure Française. You may also wish to alter the patterns, particularly the cushions, for your head measurements.

Additionally, the social class of your character matters: would she be wearing her hair low and smooth or in a fashionably frizzed style? Alter the patterns to your liking and as relates to your persona’s specific time period and social status.

We hope you enjoy using this book and learning about the second half of the eighteenth century from the shoulders up. Most importantly, explore, experiment and have fun!

Historic Stitches and How to Sew Them

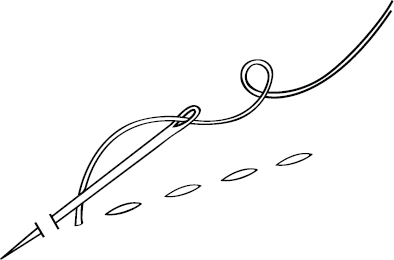

Working from right to left, weave the needle up and down through all the layers. When you’re using running stitches for hemming or a seam, make sure that the visible stitch is very fine. Basting stitches should be long and even.

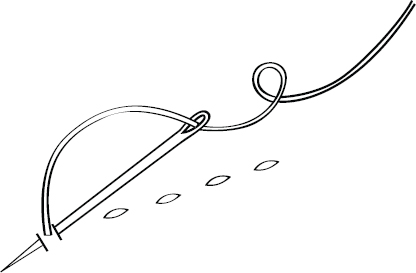

Working right to left, anchor the knot on the wrong side of the fabric, bringing the needle up through all the layers. Travel a couple of threads to the right of where your needle came through, push the needle through all the layers and bring it back up equidistant from the first puncture. Bring the needle to that same thread entry point, pushing down through all the layers, traveling equidistant to the left, bring the needle up through and repeat. This is the strongest stitch, ideal for seams.

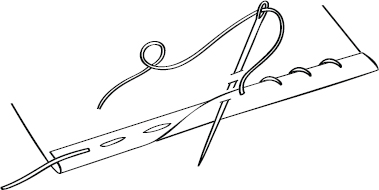

Using the instructions above, combine the running and backstitch. Stitch two or three running stitches and then a backstitch for strength.

Working from right to left, anchor the knot on the wrong side of the fabric, and come straight up through all the layers. Bring your needle down 1 or 2 threads to the right, making sure the needle goes through all the layers. Bring the needle up equidistant from how far you spaced the stitches from the seam edge. For example, if you’re sewing ¼ inch (6 mm) in from the folded edge, space your stitches ¼ inch (6 mm) apart. This careful and visible spaced backstitch is used most often on side seams.

Working left to right, turn up half of the seam allowance on the edge of your fabric and baste with long running stitches. Turn up the remaining seam allowance again to encase the raw edge. To hem stitch, bury your knot between the fold and fabric, bringing the needle out toward you. Travel a little bit to the left and pass the needle through the outer fabric, bringing it back in through the folded layers. The resulting stitch is visible on the outside of the garment, and should be small and fine.

Working left to right, turn up a narrow seam allowance (⅛ to ¼ inch [3 to 6 mm]) on the edge of your fabric and baste with long running stitches. Then fold this edge up again in half so the finished hem is between $$ and ⅛ inch (1 and 3 mm) wide. Hem stitch from right to left in the same technique explained above.

This stitch is commonly used to join the fashion fabric and the lining. Before stitching, turn in the seam allowances on both pieces and baste. With the two pieces placed wrong sides together, offset the fashion fabric to be slightly above the lining fabric and pin into place. With the lining side facing you, bury your knot between the two layers with the needle coming out toward you through the lining. Travel a small amount to the left and make a small stitch catching all the layers, and bring the needle back toward you. Repeat. This stitch is visible on the outside and should be small.

This technique is used in hat-making. It is a “traveling” stitch that creates a tiny, unobtrusive prick stitch on both sides of the fabric at once. Start on the underside of the fabric or brim. Pass the needle through to the other side, then back down behind the first point to create a teeny tiny backstitch. When you pass the needle through, do so at an angle in your direction of travel so that the needle comes out on the opposite side about ¼ inch (6 mm) away from the previous stitch. Repeat the motion with the tiny backstitch and angled needle to the top side, creating the hidden “figure 8.”

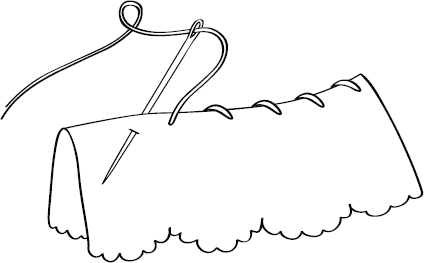

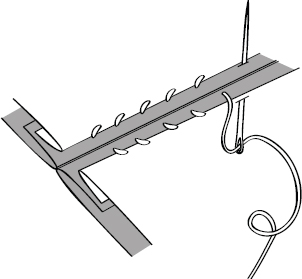

In this book, the blanket stitch is used to securely attach millinery wire to the edge of a hat brim. Knot the thread and pass the needle through the underside of the hat brim. With the wire clipped in place right on the edge of the brim, pass the needle through the hat brim again from the underside to the topside, creating a loop of thread over the wire. With the loop still loose, pass the needle toward you through the thread loop and pull it all taught. Repeat the stitch again about ½ inch (1.2 cm) away from the first stitch.

This is performed just like the hem stitch except that the travel and catches are in reverse. The small stitch is the one you see, and you will travel on the underside. This is used when you’re sewing from the right side of the fabric.

This stitch is commonly used over an edge, either raw or finished. Place the two pieces of fabric right sides together and pin. Working right to left, work with the needle pointing toward you, passing through all the layers. Bring the needle back around to the far layer, passing through the layers with the needle facing you. Repeat.

Working right to left, whip over the edge of the fabric a determined distance. Then pull the thread, gathering up the fabric to the desired length, and knot the thread (but do not cut) before moving on to the next section.

This technique is going to be used for your aprons and 1790s ensemble. It consists of three evenly spaced and stitched running stitches that are then gathered up to fit the desired space. The gathers are then carefully stitched with a hem or whipstitch, making sure that you catch every bump in the gathers.

Turn in the seam allowances on both fashion fabric pieces and both lining pieces and baste. Apply the lining pieces to the fashion fabric pieces, wrong sides together, with the lining edge placed just inside the fashion fabric edge. Baste the lining and fashion fabric together.

Next, place the two pieces with fashion fabric right sides together and pin. Working right to left, bury the knot of your thread between the lining and fashion fabric layer, then pass the needle through the three stacked layers—fashion fabric, fashion fabric and lining. Now turn the needle back, skip the lining layer and pass the needle again through the three stacked layers—fashion fabric, fashion fabric and lining. Keep your stitches very small and tight here, about 12 stitches per inch (2.5 cm).

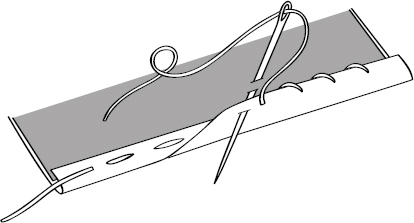

The mantua maker’s seam is an ingenious, efficient way to connect and encase raw edges. Though similar to a modern French seam or felled seam, the mantua maker’s seam is fast, easy and period correct.

To work a mantua maker’s seam, start with two layers of fabric, right sides together. Offset the bottom fabric by ⅛ to ¼ inch (3 to 6 mm), depending on how wide you need this seam to be. Fold the bottom fabric up and over the top fabric once and baste into place, sewing from right to left. Next, fold the baste edge up once more and hem stitch through all the layers. When you’re finished, you will be able to open up this seam and have a clean finish on the outside and an encased raw edge on the interior.

Our goal with this project was to create an inclusive book for the modern costumer and reenactor. The eighteenth century, like the twenty-first century, was a diverse and complicated world. It would be a disservice to only present models of a single ethnic background. We have attempted to demonstrate historically correct eighteenth-century hair practices on a range of hair textures, length and color. We did this not only to reflect the diversity found in our costuming and reenacting community today, but to also ensure that techniques for your hair texture are represented.

Everyone’s hair is different, with an endless variety of texture and characteristics regardless of one’s race. You know your hair best, so experiment with the pomade, powder and styling techniques to find what works best for you.

On the following pages we provide a rough idea of what to expect with pomatum and powder based on the widely accepted Andre Walker Hair Typing System. [1]

Pompeo Batoni, 1708–1787. Portrait of a Woman, Traditionally Identified as Margaret Stuart, Lady Hippisley. 1785. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection. B1981.25.37.

Type 1A & 1B – Straight and fine hair that is inclined to get oily. For most people with this hair texture small to moderate amount of pomatum with a lot of powder is needed [2] depending on dryness and chemical processing. The result is hair that is several times thicker in appearance and feel and lighter in color. This texture was the most common among our models and also very familiar to us, as we both also have Type 1A and 1B hair. Please see our 1750s and 1785 styles here and here for this hair type.

Additionally, we found that working with Jenny, who is Chinese, we had to use less powder for her hairstyle because she was prone to a lot of breakage and flyaways. You will notice that we “puffed” on the powder with a modern-day bellows in this tutorial to avoid touching the hair with the powder brush. To see Jenny’s 1776 hairstyle, see here.

Type 1C – Straight hair that is thick in texture. This texture can be found in multiple races and ethnicities, and it requires a lot of pomatum and powder. The physical feel is subtler than Type 1A & 1B, though the weight and thickness of the hair will definitely increase. You might find that pomading and powdering this hair texture will take hours versus minutes. For projects with models with this hair texture, please refer to our 1765 style with Cynthia and the 1774 tutorial with Laurie, here and here.

Type 2A – Fine texture but with some wave to it. We suggest the same pomatum and powder application as Type 1A and 1B, and you should expect the same results. Additionally, you’ll have an easier time curling your hair with heat. Check out our 1782 tutorial with Nicole here for an example of this hair texture.

Type 2B & 2C – Wavy and thick (2C being much thicker and coarser than 2B). As with 1C, you’ll need a lot more pomatum for your hair to get to that same “damp” appearance you need before applying the powder. You might also find that your hair doesn’t hold powder as well because the pomade is absorbed into the hair follicle. Just keep adding pomade and powder as needed. For an example of this hair texture, see the 1790s chapter with Zyna here, as her hair could go either 2C or 3A.

Type 3A – Appears straight when wet but dries curly. Depending on how thick the follicle is and how dry the hair is, you might need a little or a lot of pomatum and powder. If you’re inclined to oily hair, you’ll need less pomatum and more powder, whereas dry hair needs a lot more pomatum. You also might find that your curls will straighten out a bit with the weight of the pomatum and powder. If you want to keep your curls in place, you might want to use less powder. If you have thick hair, look at our 1790s project here. If you have fine or medium hair, most of the techniques found in the 1750s, 1782 and 1785 projects will still work for you.

Type 3B & 3C – Thickness of the hair varies, with tight to very tight curls or kinks. With this hair texture, we avoided backcombing as the curls gave us enough texture to work with. Pomatum and powder work fine with the hair. The amount used will depend on how fine the follicle is and how oily or dry your hair is. This is a very desirable texture for eighteenth-century hair, as most of the hairstyles focus on crape-ing and curling the hair to mimic this texture. Keep that in mind when comparing your hair to the projects—you might have less work to do! For an example of this hair type and the specific techniques we used, check out our 1780 style with Jasmine here.

Type 4A – Very tight S-curl, and usually of a coarser texture. This hair type can be delicate and easily damaged. The amount of pomatum and powder you use will be dependent on if the hair is oily or dry and if the individual strands are thick or fine. Like with the 3C hair type, very tightly curled hair was considered quite beautiful and desirable. When you’re re-creating the styles from the 1750s or 1782 chapter, you’ll be able to use your natural texture. You also won’t need to do any teasing or backcombing; you may need to straighten the hair a bit for the buckles and chignon, as seen here.

Type 4B & 4C – Very tight and dense curls. This hair texture is great for creating eighteenth-century hairstyles depending on the length of the hair. The amount of pomatum and powder used is up to you. If you are of African descent with this hair texture, there is historical evidence of hair being worn with and without powder during this period. [3] The choice is yours. You may wish to use your false chignon and buckles hairpieces for ease of styling, or straighten your hair a little to achieve the chignon and buckles with your own locks. Teasing is not recommended for this hair type, and the use of cushions may also not be needed. To learn more, see here and here.

While we hope that using this hair type system has covered the majority of hair textures and types, you might not identify with one particular project or type. We hope you will see the similarities in the different projects to piece together what works best for you. Hair is such a unique part of the human experience, and we cannot stress enough that your hair type and texture is truly unique to you. Have fun, experiment and find your best Georgian-hairstyling workflow.