Figure 5.1 Discovery frequency of oil and gas or gas-condensate reservoirs versus depth for 17 parishes in southwest Louisiana, 1952–56, inclusive (data from Ira Rinehart’s Yearbooks).2

Gas-condensate production may be thought of as intermediate between oil and gas. Oil reservoirs have a dissolved gas content in the range of zero (dead oil) to a few thousand cubic feet per barrel, whereas in gas reservoirs, 1 bbl of liquid (condensate) is vaporized in 100,000 SCF of gas or more, from which a small or negligible amount of hydrocarbon liquid is obtained in surface separators. Gas-condensate production is predominantly gas from which more or less liquid is condensed in the surface separators—hence the name gas condensate. The liquid is sometimes called by an older name, distillate, and also sometimes simply oil because it is an oil. Gas-condensate reservoirs may be approximately defined as those that produce light-colored or colorless stock-tank liquids with gravities above 45 °API at gas-oil ratios in the range of 5000 to 100,000 SCF/STB. Allen has pointed out the inadequacy of classifying wells and the reservoirs from which they produce entirely on the basis of surface gas-oil ratios—for the classification of reservoirs, as discussed in Chapter 1, properly depends on (1) the composition of the hydrocarbon accumulation and (2) the temperature and pressure of the accumulation in the Earth.1

As the search for new fields led to deeper drilling, new discoveries consisted predominately of gas and gas-condensate reservoirs. Figure 5.1, based on well test data reported in Ira Rinehart’s Yearbooks, shows the discovery trend for 17 parishes in southwest Louisiana for 1952–56, inclusive.2 The reservoirs were separated into oil and gas or gas-condensate types on the basis of well test gas-oil ratios and the API gravity of the produced liquid. Oil discoveries predominated at depths less than 8000 ft, but gas and gas-condensate discoveries predominated below 10,000 ft. The decline in discoveries below 12,000 ft was due to the fewer number of wells drilled below that depth rather than to a drop in the occurrence of hydrocarbons. Figure 5.2 shows the same data for the year 1955 with the gas-oil ratio plotted versus depth. The dashed line marked “oil” indicates the general trend to increased solution gas in oil with increasing pressure (depth), and the envelop to the lower right encloses those discoveries that were of the gas or gas-condensate types.

Figure 5.1 Discovery frequency of oil and gas or gas-condensate reservoirs versus depth for 17 parishes in southwest Louisiana, 1952–56, inclusive (data from Ira Rinehart’s Yearbooks).2

Figure 5.2 Plot showing trend of increase of gas-oil ratio versus depth for 17 parishes in southwest Louisiana during 1955 (data from Ira Rinehart’s Yearbooks).2

Muskat, Standing, Thornton, and Eilerts have discussed the properties and behavior of gas-condensate reservoirs.3–6 Table 5.1, taken from Eilerts, shows the distribution of the gas-oil ratio and the API gravity among 172 gas and gas-condensate fields in Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi.6 These authors found no correlation between the gas-oil ratio and the API gravity of the tank liquid for these fields.

Table 5.1 Range of Gas-Oil Ratios and Tank Oil Gravities for 172 Gas and Gas-Condensate Fields in Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi

In a gas-condensate reservoir, the initial phase is gas, but typically the fluid of commercial interest is the gas condensate. The strategies for maximizing recovery of the condensate distinguish gas-condensate reservoirs from single-phase gas reservoirs. For example, in a single-phase gas reservoir, reducing the reservoir pressure increases the recovery factor, and a water drive is likely to reduce the recovery factor. In a gas-condensate reservoir, reducing the reservoir pressure below the dew-point pressure reduces condensate recovery, and therefore a water drive that maintains the reservoir pressure above the dew-point pressure will likely increase condensate recovery. Similarly, strategies for increasing condensate recovery differ from those used for oil recovery. In particular, injecting water maintains pressure and displaces oil toward producing wells, but for condensate, it is better to use gas as a pressure maintenance and displacement fluid. This chapter will aid the engineer in designing a recovery plan for a gas-condensate reservoir that will attempt to maximize the production of the more valuable components of the reservoir fluid.

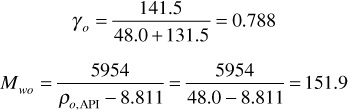

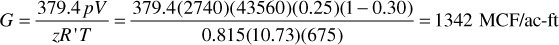

The initial gas and oil (condensate) for gas-condensate reservoirs, both retrograde and nonretrograde, may be calculated from generally available field data by recombining the produced gas and oil in the correct ratio to find the average specific gravity (air = 1.00) of the total well fluid, which is presumably being produced initially from a one-phase reservoir. Consider the two-stage separation system shown in Fig. 1.3. The average specific gravity of the total well fluid is given by Eq. (5.1):

where

R1, R3 = producing gas-oil ratios from the separator (1) and stock tank (3)

γ1, γ3 = specific gravities of separator and stock-tank gases

γo = specific gravity of the stock-tank oil (water = 1.00), given by

Mwo = molecular weight of the stock-tank oil that is given by Eq. (4.20):

Example 5.1 shows the use of Eq. (5.1) to calculate the initial gas and oil in place per acre-foot of a gas-condensate reservoir from the usual production data. The three example problems in this chapter represent the type of calculations that an engineer would perform on data generated from laboratory tests on reservoir fluid samples from gas-condensate systems. Sample reports containing additional example calculations may be obtained from commercial laboratories that conduct PVT studies. The engineer dealing with gas-condensate reservoirs should obtain these sample reports to supplement the material in this chapter. The gas deviation factor at initial reservoir temperature and pressure is estimated from the gas gravity of the recombined oil and gas, as shown in Chapter 2. From the estimated gas deviation factor and the reservoir temperature, pressure, porosity, and connate water, the moles of hydrocarbons per acre-foot can be calculated, and from this, the initial gas and oil in place.

Example 5.1 Calculating the Initial Oil and Gas in Place per Acre-Foot for a Gas-Condensate Reservoir

Given

Initial pressure = 2740 psia

Reservoir temperature = 215°F

Average porosity = 25%

Average connate water = 30%

Daily tank oil = 242 STB

Oil gravity, 60°F = 48.0 °API

Daily separator gas = 3100 MCF

Separator gas specific gravity = 0.650

Daily tank gas = 120 MCF

Tank gas specific gravity = 1.20

Solution

From Eqs. (2.11) and (2.12), pc = 636 psia and Tc = 430°R. Also, Tr = 1.57 and pr = 4.30, from which, using Fig. 2.2, the gas deviation factor is 0.815 at the initial conditions. Thus the total initial gas in place per acre-foot of bulk reservoir is

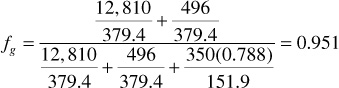

Because the volume fraction equals the mole fraction in the gas state, the fraction of the total produced on the surface as gas is

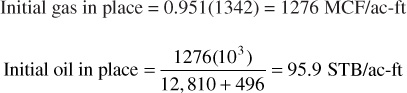

Thus

Because the gas production is 95.1% of the total moles produced, the total daily gas-condensate production in MCF is

The total daily reservoir voidage by the gas law is

The gas deviation factor of the total well fluid at reservoir temperature and pressure can also be calculated from its composition. The composition of the total well fluid is calculated from the analyses of the produced gas(es) and liquid by recombining them in the ratio in which they are produced. When the composition of the stock-tank liquid is known, a unit of this liquid must be combined with the proper amounts of gas(es) from the separator(s) and the stock tank, each of which has its own composition. When the compositions of the gas and liquid in the first or high-pressure separator are known, the shrinkage the separator liquid undergoes in passing to the stock tank must be measured or calculated in order to know the proper proportions in which the separator gas and liquid must be combined. For example, if the volume factor of the separator liquid is 1.20 separator bbl per stock-tank barrel and the measured gas-oil ratio is 20,000 SCF of high-pressure gas per bbl of stock-tank liquid, then the separator gas and liquid samples should be recombined in the proportions of 20,000 SCF of gas to 1.20 bbl of separator liquid, since 1.20 bbl of separator liquid shrinks to 1.00 bbl in the stock tank.

Example 5.2 shows the calculation of initial gas and oil in place for a gas-condensate reservoir from the analyses of the high-pressure gas and liquid, assuming the well fluid to be the same as the reservoir fluid. The calculation is the same as that shown in Example 5.1, except that the gas deviation factor of the reservoir fluid is found from the pseudoreduced temperature and pressure, which are determined from the composition of the total well fluid rather than from its specific gravity. Figure 5.3 presents charts for estimating the pseudocritical temperature and pressure of the heptanes-plus fraction from its molecular weight and specific gravity.

Figure 5.3 Correlation charts for estimation of the pseudocritical temperature and pressure of heptanes plus fractions from molecular weight and specific gravity (after Mathews, Roland, and Katz, proc. NGAA).7

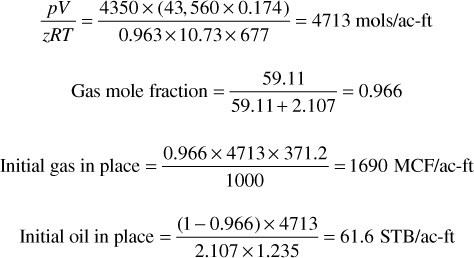

Example 5.2 Calculating the Initial Gas and Oil in Place from the Compositions of the Gas and Liquid from the High-Pressure Separator

Given

Reservoir pressure = 4350 psia

Reservoir temperature = 217°F

Hydrocarbon porosity = 17.4%

Standard conditions = 15.025 psia, 60°F

Separator gas = 842,600 SCF/day

Stock-tank oil = 31.1 STB/day

Molecular weight  in separator liquid = 185.0

in separator liquid = 185.0

Specific gravity  in separator liquid = 0.8343

in separator liquid = 0.8343

Specific gravity separator liquid at 880 psig and 60°F = 0.7675

Separator liquid volume factor = 1.235 bbl/STB at 880 psia, both at 60°F

Compositions of high-pressure gas and liquid = Table 5.2, columns 2 and 3

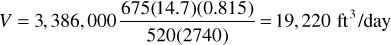

Table 5.2 Calculations for Example 5.2 on Gas-Condensate Fluid

Molar volume at 15.025 psia and 60°F = 371.2 ft3/mol

Solution

Note that column numbers refer to Table 5.2:

1. Columns 1, 2, and 3 are given. This information typically comes from a lab test performed on a sample taken from the separator. Column 4 is additional information that can also be found in Table 2.1. Using this information, calculate the mole proportions in which to recombine the separator gas and liquid. Multiply the mole fraction of each component in the liquid (column 3) by its molecular weight (column 4) and enter the products in column 5. The sum of column 5 is the molecular weight of the separator liquid, 127.48. Next, the ratio of liquid barrel per mole is needed for each component. This information is also found in Table 2.1. The last column of Table 2.1 is the estimated gal/lb-mol—these data will need to be converted to bbl/mol. The next several steps are used to match the quantity of produced liquid to produced gas and determine the composition of the entire well fluid rather than just the liquid or gas. Because the specific gravity of the separator liquid is 0.7675 at 880 psig and 60°F, the moles per barrel is

The separator liquid rate is 31.1 STB/day × 1.235 sep. bbl/STB so that the separator gas-oil ratio is

Because the 21,940 SCF is 21,940/371.2, or 59.11 mols, the separator gas and liquid must be recombined in the ratio of 59.11 mols of gas to 2.107 mols of liquid.

If the specific gravity of the separator liquid is not available, the mole per barrel figure may be calculated as follows. Multiply the mole fraction of each component in the liquid, column 3, by its barrel per mole figure, column 6, obtained from data in Table 2.1, and enter the product in column 7. The sum of column 7, 0.46706, is the number of barrels of separator liquid per mole of separator liquid, and the reciprocal is 2.141 mols/bbl (versus 2.107 measured).

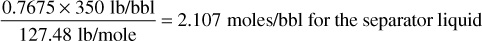

2. Now that the ratio of the gas to liquid produced is known, recombine 59.11 mols of gas and 2.107 mols of liquid. Multiply the mole fraction of each component in the gas, column 2, by 59.11 mols, and enter in column 8. Multiply the mole fraction of each component in the liquid, column 3, by 2.107 mols, and enter the solution in column 9. Enter the sum of the moles of each component in the gas and liquid, column 8, plus column 9, in column 10. Divide each figure in column 10 by the sum of column 10, 61.217, and enter the quotients in column 11, which is the mole composition of the total well fluid. Column 12 is the critical pressure for each component; it is also found in Table 2.1. With that information, the partial critical pressure (column 13) can be found. The same will be done for columns 14 and 15 for temperature. Calculate the pseudocritical temperature 379.23°R and pressure 668.23 psia from the composition by summing the partial temperature and partial pressure values for each component. From the pseudocriticals, find the pseudoreduced criticals and then the deviation factor at 4350 psia and 217°F, which is 0.963.

3. Find the gas and oil (condensate) in place per acre-foot of net reservoir rock. From the gas law, the initial moles per acre-foot at 17.4% hydrocarbon porosity is

Because the high-pressure gas is 96.6% of the total mole production, the daily gas-condensate production expressed in standard cubic feet is

The daily reservoir voidage at 4350 psia is

The behavior of single-phase gas reservoirs is treated in Chapter 4. Since no liquid phase develops within the reservoir, where the temperature is above the cricondentherm, the calculations are simplified. When the reservoir temperature is below the cricondentherm, however, a liquid phase develops within the reservoir when pressure declines below the dew point, owing to retrograde condensation, and the treatment is considerably more complex, even for volumetric reservoirs.

One solution is to closely duplicate the reservoir depletion by laboratory studies on a representative sample of the initial, single-phase reservoir fluid. The sample is placed in a high-pressure cell at reservoir temperature and initial reservoir pressure. During the depletion, the volume of the cell is held constant to duplicate a volumetric reservoir, and care is taken to remove only gas-phase hydrocarbons from the cell because, for most reservoirs, the retrograde condensate liquid that forms is trapped as an immobile liquid phase within the pore spaces of the reservoir.

Laboratory experiments have shown that, with most rocks, the oil phase is essentially immobile until it builds up to a saturation in the range of 10% to 20% of the pore space, depending on the nature of the rock pore spaces and the connate water. Because the liquid saturations for most retrograde fluids seldom exceed 10%, this is a reasonable assumption for most retrograde condensate reservoirs. In this same connection, it should be pointed out that, in the vicinity of the wellbore, retrograde liquid saturations often build up to higher values so that there is two-phase flow, both gas and retrograde liquid. This buildup of liquid occurs as the one-phase gas suffers a pressure drop as it approaches the wellbore. Continued flow increases the retrograde liquid saturation until there is liquid flow. Although this phenomenon does not affect the overall performance seriously or enter into the present performance predictions, it can (1) reduce, sometimes seriously, the flow rate of gas-condensate wells and (2) affect the accuracy of well samples taken, assuming one-phase flow into the wellbore.

The continuous depletion of the gas phase (only) of the cell at constant volume can be closely duplicated by the following more convenient technique. The content of the cell is expanded from the initial volume to a larger volume at a pressure a few hundred psi below the initial pressure by withdrawing mercury from the bottom of the cell or otherwise increasing the volume. Time is allowed for equilibrium to be established between the gas phase and the retrograde liquid phase that has formed and for the liquid to drain to the bottom of the cell so that only gas-phase hydrocarbons are produced from the top of the cell. Mercury is injected into the bottom of the cell and gas is removed at the top at such a rate as to maintain constant pressure in the cell. Thus the volume of gas removed, measured at this lower pressure and cell (reservoir) temperature, equals the volume of mercury injected when the hydrocarbon volume, now two phase, is returned to the initial cell volume. The volume of retrograde liquid is measured, and the cycle—expansion to a next lower pressure followed by the removal of a second increment of gas—is repeated down to any selected abandonment pressure. Each increment of gas removed is analyzed to find its composition, and the volume of each increment of produced gas is measured at subatmospheric pressure to determine the standard volume, using the ideal gas law. From this, the gas deviation factor at cell pressure and temperature may be calculated using the real gas law. Alternatively, the gas deviation factor at cell pressure and temperature may be calculated from the composition of the increment.

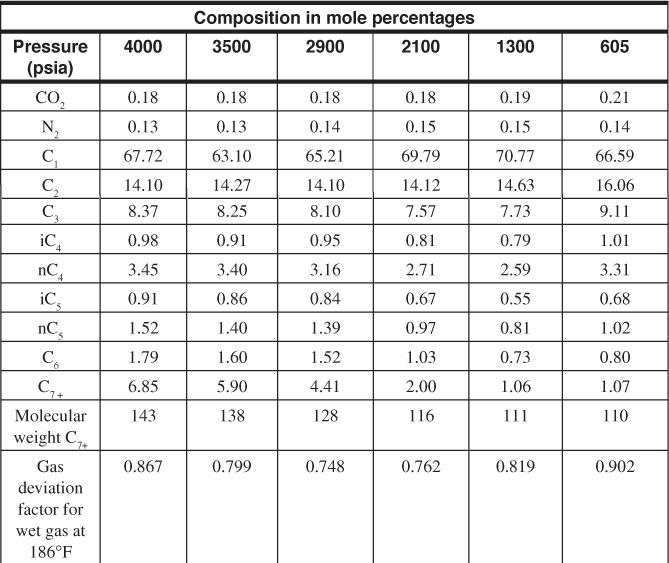

Figure 5.4 and Table 5.3 give the composition of a retrograde gas-condensate reservoir fluid at initial pressure and the composition of the gas removed from a pressure-volume-temperature (PVT) cell in each of five increments, as previously described. Table 5.3 also gives the volume of retrograde liquid in the cell at each pressure and the gas deviation factor and volume of the produced gas increments at cell pressure and temperature. As shown in Fig. 5.4, the produced gas composition changes as the pressure of the cell decreases. For example, 2500 psia shows a substantial decrease in the mole fraction of the heptanes-plus, a smaller decrease for the hexanes, even smaller for pentanes, and so on, compared to the 3000 psia composition. The lighter hydrocarbons have a corresponding increase in their mole fraction of the composition over that same interval. The trend is for the heavier hydrocarbons to selectively condense in the cell, and, therefore, they are not produced. As the cell continues to be depleted, the pressure reaches the point, as shown by point B2 in Fig. 1.4, when the heavier components begin to revaporize. For this reason, as shown in Fig. 5.4 and Table 5.3, the trend from the 1000 psia to the 500 psia increments shows an increase of the mole fraction of the heavier hydrocarbons and a decrease in the mole fraction of the lighter hydrocarbons.

Figure 5.4 Variations in the composition of the produced gas phase material of a retrograde gas-condensate fluid with pressure decline (data from Table 5.3).

The liquid recovery from the gas increments produced from the cell may be measured by passing the gas through small-scale separators, or it may be calculated from the composition for usual field separation methods or for gasoline plant methods.8,9,10 Liquid recovery of the pentanes-plus is somewhat greater in gasoline plants than in field separation and much greater for the propanes and butanes, commonly called liquefied petroleum gas (LPG). For simplicity, the liquid recovery from the gas increments of Table 5.3 is calculated in Example 5.3, assuming 25% of the butanes, 50% of the pentanes, 75% of the hexanes, and 100% of the heptanes-plus are recovered as liquid.

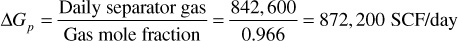

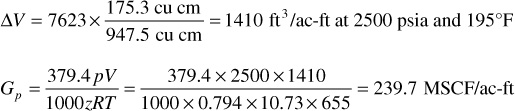

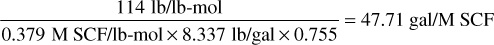

Example 5.3 Calculating the Volumetric Depletion Performance of a Retrograde Gas-Condensate Reservoir Based on the Laboratory Tests Given in Table 5.3

Given

Initial pressure (dew point) = 2960 psia

Abandonment pressure = 500 psia

Reservoir temperature = 195°F

Connate water = 30%

Porosity = 25%

Standard conditions = 14.7 psia and 60°F

Initial cell volume = 947.5 cm3

Molecular weight of C7+ in initial fluid = 114 lb/lb-mol

Specific gravity of C7+ in initial fluid = 0.755 at 60°F

Compositions, volumes, and deviation factors given in Table 5.3

Assume the same molecular weight and specific gravity for the C7+ content for all produced gas. Also assume liquid recovery from the gas is 25% of the butanes, 50% of the pentanes, 75% of the hexanes, and 100% of the heptanes and heavier gases.

Solution

Note that column numbers refer to Table 5.4.

Table 5.4 Gas and Liquid Recoveries in Percentage and per Acre-Foot for Example 5.3

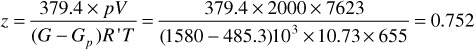

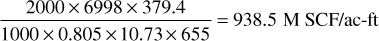

1. Calculate the increments of gross production in M SCF per ac-ft of net, bulk reservoir rock. First, calculate VHC, the hydrocarbon volume per acre-ft of reservoir. Enter the following in column 2:

VHC = 43,560 × 0.25 × (1 – 0.30) = 7623 ft3/ac-ft

For the increment produced from 2960 to 2500 psia, for example, the hydrocarbon volume will be multiplied by the ratio of the produced gas (from Table 5.3) to the cell volume given. That volume is then converted to standard units as shown.

Find the cumulative gross gas production, Gp = ∑ΔGp, and enter in column 3.

2. Calculate the M SCF of residue gas and the barrels of liquid obtained from each increment of gross gas production. Enter in columns 4 and 6. Assume that 25% of C4, 50% of C5, 75% of C6, and all C7+ are recovered as stock-tank liquid. For example, in the 239.7 M SCF produced from 2960 to 2500 psia, the mole fraction recovered as liquid is

ΔnL = 0.25 × 0.028 + 0.50 × 0.019 + 0.75 × 0.016 + 0.034

= 0.0070 + 0.0095 + 0.0120 + 0.034 = 0.0625 mole fraction

As the mole fraction also equals the volume fraction in gas, the M SCF recovered as liquid from 239.7 M SCF is

ΔGL = 0.0070 × 239.7 + 0.0095 × 239.7 + 0.0120 × 239.7 + 0.034 × 239.7

= 1.681 + 2.281 + 2.881 + 8.163 = 14.981M SCF

The gas volume can be converted to gallons of liquid using the gal/M SCF figures of Table 2.1 for C4, C5, and C6. The average of the iso- and normal compounds is used for C4 and C5.

For C7+,

0.3794 is the molar volume at standard conditions of 14.7 psia and 60°F. Then the total liquid recovered from 239.7M SCF is 1.681 × 32.04 + 2.281 × 36.32 + 2.881 × 41.03 + 8.163 × 47.71 = 53.9 + 82.8 + 118.2 + 389.5 = 644.4 gal = 15.3 STB. The residue gas recovered from the 239.7 M SCF is 239.7 × (1 – 0.0625) = 224.7 M SCF. Calculate the cumulative residue gas and stock-tank liquid recoveries from columns 4 and 6 and enter in columns 5 and 7, respectively.

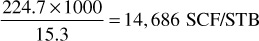

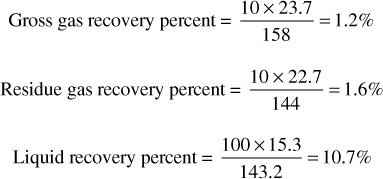

3. Calculate the gas-oil ratio for each increment of gross production in units of residue gas per barrel of liquid. Enter in column 8. For example, the gas-oil ratio of the increment produced from 2960 to 2500 psia is

4. Calculate the cumulative recovery percentages of gross gas, residue gas, and liquid. Enter in columns 9, 10, and 11. The initial gross gas in place is

Of this, the liquid mole fraction is 0.088 and the total liquid recovery is 3.808 gal/M SCF of gross gas, which are calculated from the initial composition in the same manner shown in part 2. Then

At 2500 psia, then

The results of the laboratory tests and calculations of Example 5.3 are plotted versus pressure in Fig. 5.5. The gas-oil ratio rises sharply from 10,060 SCF/bbl to about 19,000 SCF/bbl near 1600 psia. Maximum retrograde liquid and maximum gas-oil ratios do not occur at the same pressure because, as pointed out previously, the retrograde liquid volume is much larger than its equivalent obtainable stock-tank volume, and there is more stock-tank liquid in 6.0% retrograde liquid volume at 500 psia than in 7.9% at 1500 psia. Revaporization below 1600 psia helps reduce the gas-oil ratio. However, there is some doubt that revaporization equilibrium is reached in the reservoir; the field gas-oil ratios generally remain higher than that predicted. Part of this is probably a result of the lower separator efficiency of liquid recovery at the lower pressure and higher separator temperatures. Lower separator temperatures occur at higher wellhead pressures, owing to the greater cooling of the gas by free expansion in flowing through the choke. Although the overall recovery at 500-psia abandonment pressure is 86.1%, the liquid recovery is only 53.7%, owing to retrograde condensation. The cumulative production plots are slightly curved because of the variation in the gas deviation factor with pressure and with the composition of the reservoir fluid.

Figure 5.5 Gas-oil ratios, retrograde liquid volumes, and recoveries for the depletion performance of a retrograde gas-condensate reservoir (data from Tables 5.3 and 5.4).

The volumetric depletion performance of a retrograde condensate fluid, such as given in Example 5.3, may also be calculated from the initial composition of the single-phase reservoir fluid, using equilibrium ratios. An equilibrium ratio (K) is the ratio of the mole fraction (y) of any component in the vapor phase to the mole fraction (x) of the same component in the liquid phase, or K = y/x. These ratios depend on the temperature and pressure and, unfortunately, on the composition of the system. If a set of equilibrium ratios can be found that are applicable to a given condensate system, then it is possible to calculate the mole distribution between the liquid and vapor phases at any pressure and reservoir temperature and also the composition of the separate vapor and liquid phases, as shown in Fig. 5.4. From the composition and total moles in each phase, it is also possible to calculate with reasonable accuracy the liquid and vapor volumes at any pressure.

The prediction of retrograde condensate performance using equilibrium ratios is a specialized technique. Standing and Rodgers, Harrison, and Regier gave methods for adjusting published equilibrium ratio data for condensate systems to apply to systems of different compositions.4,8,11,12,13,14 They also gave step-by-step calculation methods for volumetric performance, starting with a unit volume of the initial reservoir vapor of known composition. An increment of vapor phase material is assumed to be removed from the initial volume at constant pressure, and the remaining fluid is expanded to the initial volume. The final pressure, the division in volume between the vapor and retrograde liquid phases, and the individual compositions of the vapor and liquid phases are then calculated using the adjusted equilibrium ratios. A second increment of vapor is removed at the lower pressure, and the pressure, volumes, and compositions are calculated as before. An account is kept of the produced moles of each component so that the total moles of any component remaining at any pressure are known by subtraction from the initial amount. This calculation may be continued down to any abandonment pressure, just as in the laboratory technique.

Standing points out that the prediction of condensate reservoir performance from equilibrium ratios alone is likely to be in considerable error and that some laboratory data should be available to check the accuracy of the adjusted equilibrium ratios.4 Actually, the equilibrium ratios are changing because the composition of the system remaining in the reservoir or cell changes. The changes in the composition of the heptanes-plus particularly affect the calculations. Rodgers, Harrison, and Regier point out the need for improved procedures for developing the equilibrium ratios for the heavier hydrocarbons to improve the overall accuracy of the calculation.8

Jacoby, Koeller, and Berry studied the phase behavior of eight mixtures of separator oil and gas from a lean gas-condensate reservoir at recombined ratios in the range of 2000 to 25,000 SCF/STB and at several temperatures in the range of 100°F to 250°F.15 The results are useful in predicting the depletion performance of gas-condensate reservoirs for which laboratory studies are not available. They show that there is a gradual change in the surface production performance from the volatile oil to the rich gas-condensate type of reservoir and that a laboratory examination is necessary to distinguish between the dew-point and bubble-point reservoirs in the range of 2000 to 6000 SCF/STB gas-oil ratios.

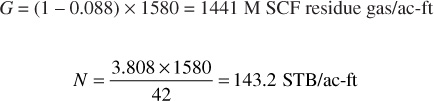

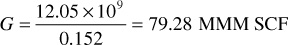

The laboratory test on the retrograde condensate fluid in Example 5.3 is itself a material balance study of the volumetric performance of the reservoir from which the sample was taken. The application of the basic data and the calculated data of Example 5.3 to a volumetric reservoir is straightforward. For example, suppose the reservoir had produced 12.05 MMM SCF of gross well fluid when the average reservoir pressure declined from 2960 psia initial to 2500 psia. According to Table 5.4, the recovery at 2500 psia under volumetric depletion is 15.2% of the initial gross gas in place, and therefore the initial gross gas in place is

Because Table 5.4 shows a recovery of 80.4% down to an abandonment pressure of 500 psia, the initial recoverable gross gas or the initial reserve is

Initial reserve = 79.28 × 109 × 0.804 = 63.74 MMM SCF

Since 12.05MMM SCF has already been recovered, the reserve at 2500 psia is

Reserve at 2500 psia = 63.74 – 12.05 = 51.69 MMM SCF

The accuracy of these calculations depends, among other things, on the sampling accuracy and the degree of which the laboratory test represents the volumetric performance. Generally there are pressure gradients throughout a reservoir to indicate that the various portions of the reservoir are in varying stages of depletion. This is due to greater withdrawals in some portions and/or to lower reserves in some portions because of lower porosities and/or lower net productive thicknesses. As a consequence, the gas-oil ratios of the wells differ, and the average composition of the total reservoir production at any prevailing average reservoir pressure does not exactly equal the composition of the total cell production at the same pressure.

Although the gross gas production history of a volumetric reservoir follows the laboratory tests more or less closely, the division of the production into residue gas and liquid follows with less accuracy. This is due to the differences in the stage of depletion of various portions of the reservoir, as explained in the preceding paragraph, and also to the differences between the calculated liquid recoveries in the laboratory tests and the actual efficiency of separators in recovering liquid from the fluid in the field.

The previous remarks apply only to volumetric single-phase gas-condensate reservoirs. Unfortunately, most retrograde gas-condensate reservoirs that have been discovered are initially at their dew-point pressures rather than above them. This indicates the presence of an oil zone in contact with the gas-condensate cap. The oil zone may be negligibly small or commensurate with the size of the cap, or it may be much larger. The presence of a small oil zone affects the accuracy of the calculations based on the single-phase study and is more serious for a larger oil zone. When the oil zone is of a size at all commensurate with the gas cap, the two must be treated together as a two-phase reservoir, as explained in Chapter 7.

Many gas-condensate reservoirs are produced under a partial or total water drive. When the reservoir pressure stabilizes or stops declining, as occurs in many reservoirs, recovery depends on the value of the pressure at stabilization and the efficiency with which the invading water displaces the gas phase from the rock. The liquid recovery is lower for the greater retrograde condensation because the retrograde liquid is generally immobile and is trapped together with some gas behind the invading waterfront. This situation is aggravated by permeability variations because the wells become “drowned” and are forced off production before the less permeable strata are depleted. In many cases, the recovery by water drive is less than by volumetric performance, as explained in Chapter 4, section 3.4.

When an oil zone is absent or negligible, the material balance Eq. (4.13) may be applied to retrograde reservoirs under both volumetric and water-drive performance, just as for the single-phase (nonretrograde) gas reservoirs for which it was developed:

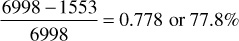

This equation may be used to find either the water influx, We, or the initial gas in place, G. The equation contains the gas deviation factor z at the lower pressure. It is included in the gas volume factor Bg in Eq. (4.13). Because this deviation factor applies to the gas-condensate fluid remaining in the reservoir, when the pressure is below the dew-point pressure in retrograde reservoirs, it is a two-phase gas deviation factor. The actual volume in Eq. (2.7) includes the volume of both the gas and liquid phases, and the ideal volume is calculated from the total moles of gas and liquid, assuming ideal gas behavior. For volumetric performance, this two-phase deviation factor may be obtained from such laboratory data as obtained in Example 5.3. For example, from the data of Table 5.5, the cumulative gross gas production down to 2000 psia is 485.3M SCF/ac-ft out of an initial content of 1580 M SCF/ac-ft. Since the initial hydrocarbon pore volume is 7623 ft3/ac-ft (Example 5.3), the two-phase volume factor for the fluid remaining in the reservoir at 2000 psia and 195°F as calculated using the gas law is

Table 5.5 Two-Phase and Single-Phase Gas Deviation Factors for the Retrograde Gas-Condensate Fluid of Example 5.3

Table 5.5 gives the two-phase gas deviation factors for the fluid remaining in the reservoir at pressures down to 500 psia, calculated as before for the gas-condensate fluid of Example 5.3. These data are not strictly applicable when there is some water influx because they are based on cell performance in which vapor equilibrium is maintained between all the gas and liquid remaining in the cell, whereas in the reservoir, some of the gas and retrograde liquids are enveloped by the invading water and are prevented from entering into equilibrium with the hydrocarbons in the rest of the reservoir. The deviation factors in Table 5.5, column 4, may be used with volumetric reservoirs and, with some reduction in accuracy, with water-drive reservoirs.

When laboratory data such as those given in Example 5.3 have not been obtained, the gas deviation factors of the initial reservoir gas may be used to approximate those of the remaining reservoir fluid. These are best measured in the laboratory but may be estimated from the initial gas gravity or well-stream composition using the pseudoreduced correlations. Although the measured deviation factors for the initial gas of Example 5.3 are not available, it is believed that they are closer to the two-phase factors in column 4 than those given in column 5 of Table 5.5, which are calculated using the pseudoreduced correlations, since the latter method presumes single-phase gases. The deviation factors of the produced gas phase are given in column 6 for comparison.

Allen and Roe have reported the performance of a retrograde condensate reservoir that produces from the Bacon Lime Zone of a field located in East Texas.13 The production history of this reservoir is shown in Figs. 5.6 and 5.7. The reservoir occurs in the lower Glen Rose Formation of Cretaceous age at a depth of 7600 ft (7200 ft subsea) and comprises some 3100 acres. It is composed of approximately 50 ft of dense, crystalline, fossiliferous dolomite, with an average permeability of 30 to 40 millidarcys in the more permeable stringers and an estimated average porosity of about 10%. Interstitial water is approximately 30%. The reservoir temperature is 220°F, and the initial pressure was 3691 psia at 7200 ft subsea. Because the reservoir was very heterogeneous regarding porosity and permeability, and because very poor communication between wells was observed, cycling (section 5.6) was not considered feasible. The reservoir was therefore produced by pressure depletion, using three-stage separation to recover the condensate. The recovery at 600 psia was 20,500 MM SCF and 830,000 bbl of condensate, or a cumulative (average) gas-oil ratio of 24,700 SCF/bbl, or 1.70 GPM (gallons per MCF). Since the initial gas-oil ratios were about 12,000 SCF/bbl (3.50 GPM), the condensate recovery of 600 psia was 100 × 1.7/3.5, or 48.6% of the liquid originally contained in the produced gas. Theoretical calculations based on equilibrium ratios predicted a recovery of only 1.54 GPM (27,300 gas-oil ratio), or 44% recovery, which is about 10% lower.

Figure 5.6 Production history of the Bacon Lime Zone of an eastern Texas gas-condensate reservoir (after Allen and Roe, trans. AlME).13

Figure 5.7 Calculated and measured pressure and p/z values versus cumulative gross gas recovery from the Bacon Lime Zone of an eastern Texas gas-condensate reservoir (after Allen and Roe, trans. AlME).13

The difference between the actual and predicted recoveries may have been due to sampling errors. The initial well samples may have been deficient in the heavier hydrocarbons, owing to retrograde condensation of liquid from the flowing fluid as it approached the wellbore (section 5.3). Another possibility suggested by Allen and Roe is the omission of nitrogen as a constituent of the gas from the calculations. A small amount of nitrogen, always below 1 mol %, was found in several of the samples during the life of the reservoir. Finally, they suggested the possibility of retrograde liquid flow in the reservoir to account for a liquid recovery higher than that predicted by their theoretical calculations, which presume the immobility of the retrograde liquid phase. Considering the many variables that influence both the calculated recovery using equilibrium ratios and the field performance, the agreement between the two appears good.

Figure 5.8 shows good general agreement between the butanes-plus content calculated from the composition of the production from two wells and the content calculated from the study based on equilibrium ratios. The liquid content expressed in butanes-plus is higher than the stock-tank GPM (Fig. 5.7) because not all the butanes—or, for that matter, all the pentanes-plus—are recovered in the field separators. The higher actual butanes-plus content down to 1600 psia is undoubtedly a result of the same causes given in the preceding paragraph to explain why the actual overall recovery of stock-tank liquid exceeded the recovery based on equilibrium ratios. The stock-tank GPM in Fig. 5.7 shows no revaporization; however, the well-stream compositions below 1600 psia in Fig. 5.8 clearly show revaporization of the butanes-plus, and therefore certainly of the pentanes-plus, which make up the majority of the separator liquid. The revaporization of the retrograde liquid in the reservoir below 1600 psia is evidently just about offset by the decrease in separator efficiency at lower pressures.

Figure 5.8 Calculated and measured butanes-plus in the well streams of the Bacon Lime Zone of an eastern Texas gas-condensate reservoir (after Allen and Roe, trans. AlME).13

Figure 5.8 also shows a comparison between the calculated reservoir behavior based on the differential process and the flash process. In the differential process, only the gas is produced and is therefore removed from contact with the liquid phase in the reservoir. In the flash process, all the gas remains in contact with the retrograde liquid, and for this, the volume of the system must increase as the pressure declines. Thus the differential process is one of constant volume and changing composition, and the flash process is one of constant composition and changing volume. Laboratory work and calculations based on equilibrium ratios are simpler with the flash process, where the overall composition of the system remains constant; however, the reservoir mechanism for the volumetric depletion of retrograde condensate reservoirs is essentially a differential process. The laboratory work and the use of equilibrium ratios discussed in section 5.3 and demonstrated in Example 5.3 approaches the differential process by a series of step-by-step flash processes. Figure 5.8 shows the close agreement between the flash and differential calculations down to 1600 psia. Below 1600 psia, the well performance is closer to the differential calculations because the reservoir mechanism largely follows the differential process, provided that only gas phase materials are produced from the reservoir (i.e., the retrograde liquid is immobile).

Figure 5.9 shows the good agreement between the reservoir field data and the laboratory data for a small (one well), noncommercial, gas-condensate accumulation in the Paradox limestone formation at a depth of 5775 ft in San Juan County, Utah. This afforded Rodgers, Harrison, and Regier a unique opportunity to compare laboratory PVT studies and studies based on equilibrium ratios with actual field depletion under closely controlled and observed conditions.8 In the laboratory, a 4000 cm3 cell was charged with representative well samples at reservoir temperature and initial reservoir pressure. The cell was pressure depleted so that only the gas phase was removed, and the produced gas was passed through miniature three-stage separators, which were operated at optimum field pressures and temperatures. The calculated performance was also obtained, as explained previously, from equations involving equilibrium ratios, assuming the differential process. Rodgers et al. concluded that the model laboratory study could adequately reproduce and predict the behavior of condensate reservoirs. Also, they found that the performance could be calculated from the composition of the initial reservoir fluid, provided representative equilibrium ratios are available.

Figure 5.9 Comparison of field and laboratory data for a Paradox limestone gas-condensate reservoir in Utah (after Rodgers, Harrison, and Regier, courtesy AlME).8

Table 5.6 shows a comparison between the initial compositions of the Bacon Lime and Paradox limestone formation fluids. The lower gas-oil ratios for the Bacon Lime are consistent with the Bacon Lime fluid’s much larger concentration of the pentanes and heavier gases.

Table 5.6 Comparison of the Compositions of the Initial Fluids in the Bacon Lime and Paradox Formations

Because the liquid content of many condensate reservoirs is a valuable and important part of the accumulation and because through retrograde condensation a large fraction of this liquid may be left in the reservoir at abandonment, the practice of lean gas cycling has been adopted in many condensate reservoirs. In gas cycling, the condensate liquid is removed from the produced (wet) gas, usually in a gasoline plant, and the residue, or dry gas, is returned to the reservoir through injection wells. The injected gas maintains reservoir pressure and retards retrograde condensation. At the same time, it drives the wet gas toward the producing wells. Because the removed liquids represent part of the wet gas volume, unless additional dry (makeup) gas is injected, reservoir pressure will decline slowly. At the conclusion of cycling (i.e., when the producing wells have been invaded by the dry gas), the reservoir is then pressure depleted (blown down) to recover the gas plus some of the remaining liquids from the portions not swept.

Although lean gas cycling appears to be an ideal solution to the retrograde condensate problem, a number of practical considerations make it less attractive. First, there is the deferred income from the sale of the gas, which may not be produced for 10 to 20 years. Second, cycling requires additional expenditures, usually some more wells, a gas compression and distribution system to the injection wells, and a liquid recovery plant. Third, it must be realized that even when reservoir pressure is maintained above the dew point, the liquid recovery by cycling may be considerably less than 100%.

Cycling recoveries can be broken down into three separate recovery factors, or efficiencies. When dry gas displaces wet gas within the pores of the reservoir rock, the microscopic displacement efficiency is in the range of 70% to 90%. Then, owing to the location and flow rates of the production and injection wells, there are areas of the reservoir that are not swept by dry gas at the time the producing wells have been invaded by dry gas, resulting in sweep efficiencies in the range of 50% to 90% (i.e., 50% to 90% of the initial pore volume is invaded by dry gas). Finally, many reservoirs are stratified in such a way that some stringers are much more permeable than others, so that the dry gas sweeps through them quite rapidly. Although considerable wet gas remains in the lower permeability (tighter) stringers, dry gas will have entered the producing wells in the more permeable stringers, eventually reducing the liquid content of the gas to the plant to an unprofitable level.

Now suppose a particular gas-condensate reservoir has a displacement efficiency of 80%, a sweep efficiency of 80%, and a permeability stratification factor of 80%. The product of these separate factors is given an overall condensate recovery by cycling of 51.2%. Under these conditions, cycling may not be particularly attractive because retrograde condensate losses by depletion performance seldom exceed 50%. However, during pressure depletion (blowdown) of the reservoir following cycling, some additional liquid may be recovered from both the swept and unswept portions of the reservoir. Also, liquid recoveries of propane and butane in gasoline plants are much higher than those from stage separation of low-temperature separation, which would be used if cycling was not adopted. From what has been said, it is evident that the question of whether to cycle involves many factors that must be carefully studied before a proper decision can be reached.

Cycling is also adopted in nonretrograde gas caps overlying oil zones, particularly when the oil is itself underlain by an active body of water. If the gas cap is produced concurrently with the oil, as the water drives the oil zone into the shrinking gas cap zone, unrecoverable oil remains not only in the original oil zone but also in that portion of the gas cap invaded by the oil. On the other hand, if the gas cap is cycled at essentially initial pressure, the active water drive displaces the oil into the producing oil wells with maximum recovery. In the meantime, some of the valuable liquids from the gas cap may be recovered by cycling. Additional benefits will accrue, of course, if the gas cap is retrograde. Even when water drive is absent, the concurrent depletion of the gas cap and the oil zone results in lowered oil recoveries, and increased oil recovery is produced by depleting the oil zone first and allowing the gas cap to expand and sweep through the oil zone.

When gas-condensate reservoirs are produced under an active water drive such that reservoir pressure declines very little below the initial pressure, there is little or no retrograde condensation, and the gas-oil ratio of the production remains substantially constant. The recovery is the same as in nonretrograde gas reservoirs under the same conditions and depends on (1) the initial connate water, Swi; (2) the residual gas saturation, Sgr, in the portion of the reservoir invaded by water; and (3) the fraction, F, of the initial reservoir volume invaded by water. The gas volume factor Bgi in ft3/SCF remains substantially constant because reservoir pressure does not decline, so the fractional recovery is

where Vi is the initial gross reservoir volume, Sgr is the residual gas saturation in the flooded area, Swi is the initial connate water saturation, and F is the fraction of the total volume invaded. Table 4.3 shows that residual gas saturations lie in range of 20% to 50% following water displacement. The fraction of the total volume invaded at any time or at abandonment depends primarily on well location and the effect of permeability stratification in edgewater drives and well spacing and the degree of water coning in bottomwater drives.

Table 5.7 shows the recovery factors calculated from Eq. (5.4), assuming a reasonable range of values for the connate water, residual gas saturation, and the fractional invasion by water at abandonment. The recovery factors apply equally to gas and gas-condensate reservoirs because, under active water drive, there is no retrograde loss.

Table 5.7 Recovery Factors for Complete Water-Drive Reservoirs Based on Eq. (5.4)

Table 5.8 shows a comparison of gas-condensate recovery for the reservoir of Example 5.3 by (1) volumetric depletion, (2) water drive at initial pressure of 2960 psia, and (3) partial water drive where the pressure stabilizes at 2000 psia. The initial gross fluid, gas, and condensate, and the recoveries by depletion performance at an assumed abandonment pressure of 500 psia, are obtained from Example 5.3 and Tables 5.3 and 5.4. Under complete water drive, the recovery is 57.1% for a residual gas saturation of 20%, a connate water of 30%, and a fractional invasion of 80% at abandonment, as may be found by Eq. (5.4) or Table 5.7. Because there is no retrograde loss, this figure applies equally to the gross gas, gas, and condensate recovery.

Table 5.8 Comparison of Gas-Condensate Recovery by Volumetric Performance, Complete Water Drive, and Partial Water Drive (Based on the Data of Tables 5.3 and 5.4 and Example 5.3. Sw = 30%; Sgr = Sor + Sgr = 20%; F = 80%)

When a partial water drive exists and the reservoir pressure stabilizes at some pressure, here 2000 psia, the recovery is approximately the sum of the recovery by pressure depletion down to the stabilization pressure, plus the recovery of the remaining fluid by complete water drive at the stabilization pressure. Because the retrograde liquid at the stabilization pressure is immobile, it is enveloped by the invading water, and the residual hydrocarbon saturation (gas plus retrograde liquid) is about the same as for gas alone, or 20% for this example. The recovery figures of Table 5.8 by depletion down to 2000 psia are obtained from Table 5.4. The additional recovery by water drive at 2000 psia may be explained using the figures of Table 5.9. At 2000 psia, the retrograde condensate volume is 625 ft3/ac-ft, or 8.2% of the initial hydrocarbon pore volume of 7623 ft3/ac-ft, 8.2% being found from the PVT data given in Table 5.3. If the residual hydrocarbon (both gas and condensate) saturation after water invasion is assumed to be 20%, as previously assumed for the residual gas saturation by complete water drive, the water volume after water drive is 80% of 10,890, or 8712 ft3/ac-ft. The remaining 20% (2178 ft3/ac-ft), assuming pressure stabilizes at 2000 psia, will consist of 625 ft3/ac-ft of condensate liquid and 1553 ft3/ac-ft of free gas. The reservoir vapor at 2000 psia prior to water drive is

Table 5.9 Volumes of Water, Gas, and Condensate in 1 Acre-Foot of Bulk Rock for the Reservoir in Example 5.3

The fractional recovery of this vapor phase by complete water drive at 2000 psia is

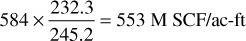

If F = 0.80—or only 80% of each acre-foot, on the average, is invaded by water at abandonment—the overall recovery reduces to 0.80 × 0.778, or 62.2% of the vapor content at 2000 psia, or 584 M SCF/ac-ft. Table 5.4 indicates that, at 2000 psia, the ratio of gross gas to residue gas after separation is 245.2 to 232.3 and that the gas-oil ratio on a residue gas basis is 17,730 SCF/bbl. Thus 584 M SCF of gross gas contains residue gas in the amount of

and tank or surface condensate liquid in the amount of

Table 5.8 indicates that for the gas-condensate reservoir of Example 5.3, using the assumed values for F and Sgr, best overall recovery is obtained by straight depletion performance. Best condensate recovery is by active water drive because no retrograde liquid forms. The value of the products obtained depends, of course, on the relative unit prices at which the gas and condensate are sold.

One of the major disadvantages associated with the use of lean gas in gas-cycling applications is that the income that would be derived from the sale of the lean gas is deferred for several years. For this reason, the use of nitrogen has been suggested as a replacement for the lean gas.16 However, one might expect the phase behavior of nitrogen and a wet gas to exhibit different characteristics from that of lean gas and the same wet gas. Researchers have found that mixing nitrogen and a typical wet gas causes the dew point of the resulting mixture to be higher than the dew point of the original wet gas.17,18 This is also true for lean gas, but the dew point is raised higher with nitrogen.17 If, in a reservoir situation, the reservoir pressure is not maintained higher than this new dew point, then retrograde condensation will occur. This condensation may be as much or more than what would occur if the reservoir was not cycled with gas. Studies have shown, however, that very little mixing occurs between an injected gas and the reservoir gas in the reservoir.17,18 Mixing occurs as a result of molecular diffusion and dispersion forces, and the resulting mixing zone width is usually only a few feet.19,20 The dew point may be raised in this local area of mixing, but this will be a very small volume and, as a result, only a small amount of condensate may drop out. Vogel and Yarborough have also shown that, under certain conditions, nitrogen revaporizes the condensate.18 The conclusion from these studies indicates that nitrogen can be used as a replacement for lean gas in cycling operations with the potential for some condensate formation that should be minimal in most applications.

Kleinsteiber, Wendschlag, and Calvin conducted a study to determine the optimum plan of depletion for the Anschutz Ranch East Unit, which is located in Summit County, Utah, and Uinta County, Wyoming.21 The Anschutz Ranch East Field, discovered in 1979, is one of the largest hydrocarbon accumulations found in the Western Overthrust Belt. Tests have indicated that the original in-place hydrocarbon content was over 800 million bbl of oil equivalent. Laboratory experiments conducted on several surface-recombined samples indicated that the reservoir fluid was a rich gas condensate. The fluid had a dew point only 150 to 300 psia below the original reservoir pressure of 5310 psia. The dew-point pressure was a function of the structural position in the reservoir, with fluid near the water-oil contact having a dew point about 300 psia lower than the original pressure and field near the crest having a dew point only about 150 psia lower. The liquid saturation, observed in constant composition expansion tests, accumulated very rapidly below the dew point, suggesting that depletion of the reservoir and the subsequent drop in reservoir pressure could cause the loss of significant amounts of condensate. Because of this potential loss of valuable hydrocarbons, a project was undertaken to determine the optimum method of production.21

To begin the study, a modified Redlich-Kwong equation of state was calibrated with the laboratory phase behavior data that had been obtained.17,22 The equation of state was then used in a compositional reservoir simulator. Several depletion schemes were considered, including primary depletion and partial or full pressure maintenance. Wet hydrocarbon gas, dry hydrocarbon gas, carbon dioxide, combustion flue gas, and nitrogen were all considered as potential gases to inject. Carbon dioxide and flue gas were eliminated due to lack of availability and high cost. The results of the study led to the conclusion that full pressure maintenance should be used. Liquid recoveries were found to be better with dry hydrocarbon gas than with nitrogen. However, when nitrogen injection was preceded by a 10% to 20% buffer of dry hydrocarbon gas, the liquid recoveries were nearly the same. When an economic analysis was coupled with the simulation study, the decision was to conduct a full-pressure maintenance program with nitrogen as the injected gas. A 10% pore volume buffer, consisting of 35% nitrogen and 65% wet hydrocarbon gas, was to be injected before the nitrogen to improve the recovery of liquid condensate.

The approach taken in the study by Kleinsteiber, Wendschlag, and Calvin would be appropriate for the evaluation of any gas-condensate reservoir. The conclusions regarding which injected material is best or whether a buffer would be necessary may be different for a reservoir gas of different composition.

5.1 A gas-condensate reservoir initially contains 1300M SCF of residue (dry or sales gas) per acre-foot and 115 STB of condensate. Gas recovery is calculated to be 85% and condensate recovery 58% by depletion performance. Calculate the value of the initial gas and condensate reserves per acre-foot if the condensate sells for $95.00/bbl and the gas sells for $6.00 per 1000 std ft3.

5.2 A well produces 45.3 STB of condensate and 742 M SCF of sales gas daily. The condensate has a molecular weight of 121.2 and a gravity of 52.0 °API at 60°F.

(a) What is the gas-oil ratio on a dry gas basis?

(b) What is the liquid content expressed in barrels per million standard cubic feet on a dry gas basis?

(c) What is the liquid content expressed in GPM on a dry gas basis?

(d) Repeat parts (a), (b), and (c), expressing the figures on a wet, or gross, gas basis.

5.3 The initial daily production from a gas-condensate reservoir is 186 STB of condensate, 3750 M SCF of high-pressure gas, and 95 M SCF of stock-tank gas. The tank oil has a gravity of 51.2 °API at 60°F. The specific gravity of the separator gas is 0.712, and the specific gravity of the stock-tank gas is 1.30. The initial reservoir pressure is 3480 psia, and reservoir temperature is 220°F. Average hydrocarbon porosity is 17.2%. Assume standard conditions of 14.7 psia and 60°F.

(a) What is the average gravity of the produced gases?

(b) What is the initial gas-oil ratio?

(c) Estimate the molecular weight of the condensate.

(d) Calculate the specific gravity (air = 1.00) of the total well production.

(e) Calculate the gas deviation factor of the initial reservoir fluid (vapor) at initial reservoir pressure.

(f) Calculate the initial moles in place per acre-foot.

(g) Calculate the mole fraction that is gas in the initial reservoir fluid.

(h) Calculate the initial (sales) gas and condensate in place per acre-foot.

5.4 (a) Calculate the gas deviation factor for the gas-condensate fluid, the composition of which is given in Table 1.3 at 5820 psia and 265°F. Use the critical values of C8 for the C7+ fraction.

(b) If half the butanes and all the pentanes and heavier gases are recovered as liquids, calculate the gas-oil ratio of the initial production. Compare with the measured gas-oil ratio.

5.5 Calculate the composition of the reservoir retrograde liquid at 2500 psia for the data of Tables 5.3 and 5.4 and Example 5.3. Assume the molecular weight of the heptanes-plus fraction to be the same as for the initial reservoir fluid.

5.6 Estimate the gas and condensate recovery for the reservoir of Example 5.3 under partial water drive if reservoir pressure stabilizes at 2500 psia. Assume a residual hydrocarbon saturation of 20% and F = 52.5%.

5.7 Calculate the recovery factor by cycling in a condensate reservoir if the displacement efficiency is 85%, the sweep efficiency is 65%, and the permeability stratification factor is 60%.

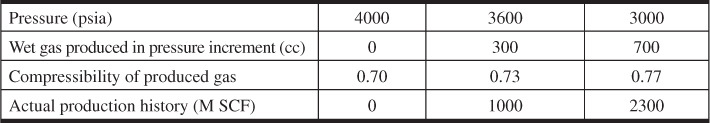

5.8 The following data are taken from a study on a recombined sample of separator gas and separator condensate in a PVT cell with an initial hydrocarbon volume of 3958.14 cm3. The wet gas gal/MSCF (GPM) and the residue gas-oil ratios were calculated using equilibrium ratios for production through a separator operating at 300 psia and 70°F. The initial reservoir pressure was 4000 psia, which was also close to the dew-point pressure, and reservoir temperature was 186°F.

(a) On the basis of an initial reservoir content of 1.00 MM SCF of wet gas, calculate the wet gas, residue gas, and condensate recovery by pressure depletion for each pressure interval.

(b) Calculate the dry gas and condensate initially in place in 1.00 MM SCF of wet gas.

(c) Calculate the cumulative recovery and the percentage of recovery of wet gas, residue gas, and condensate by depletion performance at each pressure.

(d) Calculate the recoveries at an abandonment pressure of 605 psia on an acre-foot basis for a porosity of 10% and a connate water of 20%.

5.9 If the retrograde liquid for the reservoir of Problem 5.8 becomes mobile at 15% retrograde liquid saturation, what effect will this have on the condensate recovery?

5.10 If the initial pressure of the reservoir of Problem 5.8 had been 5713 psia with the dew point at 4000 psia, calculate the additional recovery of wet gas, residue gas, and condensate per acre-foot. The gas deviation factor at 5713 psia is 1.107, and the GPM and GOR between 5713 and 4000 psia are the same as at 4000 psia.

5.11 Calculate the value of the products by each mechanism in Table 5.8 assuming (1) $85.00 per STB for condensate and $5.50 per M SCF for gas; (2) $95.00 per STB and $6.00 per M SCF; and (3) $95.00 per STB and $6.50 per M SCF.

5.12 In a PVT study of a gas-condensate fluid, 17.5 cm3 of wet gas (vapor), measured at cell pressure of 2500 psia and temperature of 195°F, was displaced into an evacuated low-pressure receiver of 5000 cm3 volume that was maintained at 250°F to ensure that no liquid phase developed in the expansion. If the pressure of the receiver rises to 620 mm Hg, what will be the deviation factor of the gas in the cell at 2500 psia and 195°F, assuming the gas in the receiver behaves ideally?

5.13 Using the assumptions of Example 5.3 and the data of Table 5.3, show that the condensate recovery between 2000 and 1500 psia is 14.0 STB/ac-ft and the residue gas-oil ratio is 19,010 SCF/bbl.

5.14 A stock-tank barrel of condensate has a gravity of 55 °API. Estimate the volume in ft3 occupied by this condensate as a single-phase gas in a reservoir at 2740 psia and 215°F. The reservoir wet gas has a gravity of 0.76.

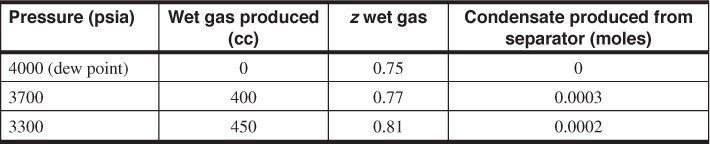

5.15 A gas-condensate reservoir has an areal extent of 200 acres, an average thickness of 15 ft, an average porosity of 0.18, and an initial water saturation of 0.23. A PVT cell is used to simulate the production from the reservoir, and the following data are collected:

The initial cell volume was 1850 cc, and the initial gas contained 0.002 mols of condensate. The initial pressure is 4000 psia, and the reservoir temperature is 200°F. Calculate the amount of dry gas (SCF) and condensate (STB) recovered at 3300 psia from the reservoir. The molecular weight and specific gravity of the condensate are 145 and 0.8, respectively.

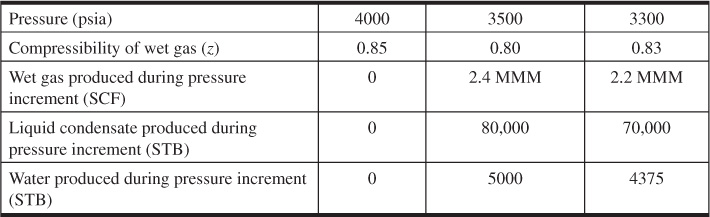

5.16 Production from a gas-condensate reservoir is listed below. The molecular weight and the specific gravity of the condensate are 150 and 0.8, respectively. The initial wet gas in place was 35 MMM SCF, and the initial condensate was 2 MM STB. Assume a volumetric reservoir and that the recoveries of condensate and water are identical, and determine the following:

(a) What is the percentage of recovery of residue gas at 3300 psia?

(b) Can a PVT cell experiment be used to simulate the production from this reservoir? Why or why not?

5.17 A PVT cell is used to simulate a gas-condensate reservoir. The initial cell volume is 1500 cc, and the initial reservoir temperature is 175°F. Show by calculations that the PVT cell will or will not adequately simulate the reservoir behavior. The data generated by the PVT experiments as well as the actual production history are as follows:

1. J. C. Allen, “Factors Affecting the Classification of Oil and Gas Wells,” API Drilling and Production Practice (1952), 118.

2. Ira Rinehart’s Yearbooks, Vol. 2, Rinehart Oil News, 1953–57.

3. M. Muskat, Physical Principles of Oil Production, McGraw-Hill, 1949, Chap. 15.

4. M. B. Standing, Volumetric and Phase Behavior of Oil Field Hydrocarbon Systems, Reinhold Publishing, 1952, Chap. 6.

5. O. F. Thornton, “Gas-Condensate Reservoirs—A Review,” API Drilling and Production Practice (1946), 150.

6. C. K. Eilerts, Phase Relations of Gas-Condensate Fluids, Vol. 1, Monograph 10, US Bureau of Mines, American Gas Association, 1957.

7. T. A. Mathews, C. H. Roland, and D. L. Katz, “High Pressure Gas Measurement,” Proc. NGAA (1942), 41.

8. J. K. Rodgers, N. H. Harrison, and S. Regier, “Comparison between the Predicted and Actual Production History of a Condensate Reservoir,” paper 883-G, presented at the AlME meeting, Oct. 1957, Dallas, TX.

9. W. E. Portman and J. M. Campbell, “Effect of Pressure, Temperature, and Well-Stream Composition on the Quantity of Stabilized Separator Fluid,” Trans. AlME (1956), 207, 308.

10. R. L. Huntington, Natural Gas and Natural Gasoline, McGraw-Hill, 1950, Chap. 7.

11. Natural Gasoline Supply Men’s Association Engineering Data Book, 7th ed., Natural Gasoline Supply Men’s Association, 1957, 161.

12. A. E. Hoffmann, J. S. Crump, and C. R. Hocott, “Equilibrium Constants for a Gas-Condensate System,” Trans. AlME (1953), 198, 1.

13. F. H. Allen and R. P. Roe, “Performance Characteristics of a Volumetric Condensate Reservoir,” Trans. AlME (1950), 189, 83.

14. J. E. Berryman, “The Predicted Performance of a Gas-Condensate System, Washington Field, Louisiana,” Trans. AlME (1957), 210, 102.

15. R. H. Jacoby, R. C. Koeller, and V. J. Berry Jr., “Effect of Composition and Temperature on Phase Behavior and Depletion Performance of Gas-Condensate Systems,” paper presented at the Annual Conference of SPE of AlME, Oct. 5–8, 1958, Houston, TX.

16. C. W. Donohoe and R. D. Buchanan, “Economic Evaluation of Cycling Gas-Condensate Reservoirs with Nitrogen,” Jour. of Petroleum Technology (Feb. 1981), 263.

17. P. L. Moses and K. Wilson, “Phase Equilibrium Considerations in Using Nitrogen for Improved Recovery from Retrograde Condensate Reservoirs,” Jour. of Petroleum Technology (Feb. 1981), 256.

18. J. L. Vogel and L. Yarborough, “The Effect of Nitrogen on the Phase Behavior and Physical Properties of Reservoir Fluids,” paper SPE 8815, presented at the First Joint SPE/DOE Symposium on Enhanced Oil Recovery, Apr. 1980, Tulsa, OK.

19. P. M. Sigmund, “Prediction of Molecular Diffusion at Reservoir Conditions. Part I—Measurement and Prediction of Binary Dense Gas Diffusion Coefficients,” Jour. of Canadian Petroleum Technology (Apr.–June 1976), 48.

20. P. M. Sigmund, “Prediction of Molecular Diffusion of Reservoir Conditions. Part II—Estimating the Effects of Molecular Diffusion and Convective Mixing in Multi-Component Systems,” Jour. of Canadian Petroleum Technology (July–Sept. 1976), 53.

21. S. W. Kleinsteiber, D. D. Wendschlag, and J. W. Calvin, “A Study for Development of a Plan of Depletion in a Rich Gas Condensate Reservoir: Anschutz Ranch East Unit, Summit County, Utah, Uinta County, Wyoming,” paper SPE 12042, presented at the 58th Annual Conference of SPE of AlME, Oct. 1983, San Francisco.

22. L. Yarborough, “Application of a Generalized Equation of State to Petroleum Reservoir Fluids,” Equations of State in Engineering, Advances in Chemical Series, ed. K. C. Chao and R. L. Robinson, American Chemical Society, 1979, 385.