Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

David R. Weber, Nicholas Jospe

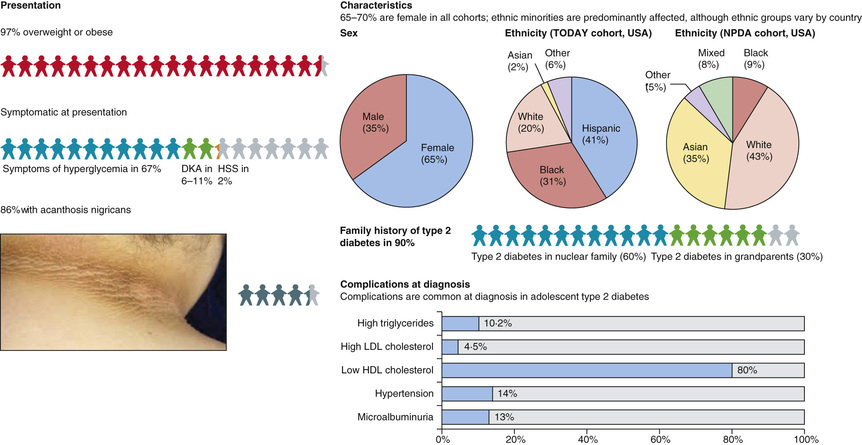

Formerly known as non–insulin dependent diabetes or adult-onset diabetes, T2DM is a heterogeneous disorder, characterized by peripheral insulin resistance and failure of the β-cell to keep up with increasing insulin demand. Patients with T2DM have relative rather than absolute insulin deficiency. Generally, they are not ketosis prone, but ketoacidosis is the initial presentation in 5–10% of affected subjects. The specific etiology is not known, but these patients do not have autoimmune destruction of β-cells, nor do they have any of the known causes of secondary diabetes (Table 607.14 ).

Table 607.14

Characteristics at Presentation for Type 1, Type 2, and Monogenic Diabetes

| TYPE 1 DIABETES | TYPE 2 DIABETES | MATURITY-ONSET DIABETES OF THE YOUNG | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of onset during childhood and adolescence | Any | Rarely before puberty | Any |

| Weight status | Any | Rarely with normal weight | Any |

| Symptomatic (polyuria, polydipsia, weight loss) | Nearly universal | Two-thirds | Common |

| Duration of symptoms before presentation | <1 month | Frequently >1 month | Any |

| Diabetic ketoacidosis at presentation | Common | Rare (6–11%) | .. |

| Family history of diabetes before age 40 | Uncommon | Strong family history for type 2 diabetes | Very strong family history, classically in 3 generations |

| Acanthosis nigricans | Rare | Common (86%) | .. |

| Ethnicity | Any | Predominantly black or minority ethnicity | Any |

| Diabetes-associated antibodies (IA2, glutamate decarboxylase, insulin) | Positive in majority | Negative (<10%) | Negative (<1%) |

| Genetic mutation in HNF1A, GCK , orHNF4A | Negative | Negative | Nearly universal |

| Complications at presentation | Very rare | Common | Rare |

IA2, tyrosine phosphatase-related islet antigen 2.

From Viner R, White B, Christie D: Type 2 diabetes in adolescents: a severe phenotype posing major clinical challenges and public health burden. Lancet 389:2252–2260, 2017.

Natural History

T2DM is considered a polygenic disease aggravated by environmental factors, with low physical activity and excessive caloric intake. Most patients are obese, although the disease can occasionally be seen in normal weight individuals. Asians in particular appear to be at risk for T2DM at lower degrees of total adiposity. Some patients may not necessarily meet overweight or obese criteria for age and gender despite abnormally high percentage of body fat in the abdominal region. Obesity, in particular central obesity, is associated with the development of insulin resistance. In addition, patients who are at risk for developing T2DM exhibit decreased glucose-induced insulin secretion. Obesity does not lead to the same degree of insulin resistance in all individuals and even those who develop insulin resistance do not necessarily exhibit impaired β-cell function. Thus, many obese individuals have some degree of insulin resistance but compensate for it by increasing insulin secretion. Those individuals who are unable to adequately compensate for insulin resistance by increasing insulin secretion develop IGT and IFG (usually, although not always, in that order). Hepatic insulin resistance leads to excessive hepatic glucose output (failure of insulin to suppress hepatic glucose output), while skeletal muscle insulin resistance leads to decreased glucose uptake in a major site of glucose disposal. Over time hyperglycemia worsens, a phenomenon that has been attributed to the deleterious effect of chronic hyperglycemia (glucotoxicity) or chronic hyperlipidemia (lipotoxicity) on β-cell function and is often accompanied by increased triglyceride content and decreased insulin gene expression. At some point, blood glucose elevation meets the criteria for diagnosis of T2DM (see Table 607.2 ), but most patients with T2DM remain asymptomatic for months to years after this point because hyperglycemia is moderate and symptoms are not as dramatic as the polyuria and weight loss at presentation of T1DM. Weight gain may even continue. The prolonged hyperglycemia may be accompanied by the development of microvascular and macrovascular complications. Among the differences between T2DM in children and adults is a faster decline in beta cell function and insulin secretion, as well as faster development of diabetes complications. In time, β-cell function can decrease to the point that the patient has absolute insulin deficiency and becomes dependent on exogenous insulin. In T2DM, insulin deficiency is rarely absolute, so patients usually do not need insulin to survive. Nevertheless, at the time of diagnosis, glycemic control can be best improved by exogenous insulin. Although DKA is uncommon in patients with T2DM, it can occur and is usually associated with the stress of another illness such as severe infection. DKA tends to be more common in African American patients than in other ethnic groups. Although it is generally believed that autoimmune destruction of pancreatic β-cells does not occur in T2DM, autoimmune markers of T1DM—namely, glutamic acid decarboxylase antibody, ICA512, and insulin-associated autoantibody—may be positive in up to one third of the cases of adolescent T2DM. The presence of these autoimmune markers does not rule out T2DM in children and adolescents. At the same time, because of the general increase in obesity, the presence of obesity does not preclude the diagnosis of T1DM. Although the majority of newly diagnosed children and adolescents can be confidently assigned a diagnosis of T1DM or T2DM, a few exhibit features of both types and are difficult to classify.

Epidemiology

The Search for Diabetes in Youth (SEARCH) study found that the prevalence of T2DM in the 10-19 yr old age group in the United States was 0.24/1000 in 2009. The incidence of T2DM in children has risen dramatically in recent years, from 9 cases per 100,000 youth in 2002 to 12.5 cases per 100,000 in 2011. Certain ethnic groups appear to be at higher risk; for example, Native Americans, Hispanic Americans, and African Americans (in that order) have higher incidence rates than white Americans (Fig. 607.8 ). Although a majority of children presenting with diabetes still have T1DM, the percentage of children presenting with T2DM is increasing and represents up to 50% of the newly diagnosed children in some centers.

Prevalence in the rest of the world varies widely and accurate data are not available for many countries, but it is clear that the prevalence is increasing in every part of the world. Asians in general seem to develop T2DM at lower body mass index levels than Europeans. In conjunction with their low incidence of T1DM, this means that T2DM accounts for a higher proportion of childhood diabetes in many Asian countries.

The epidemic of T2DM in children and adolescents parallels the emergence of the obesity epidemic. Although obesity itself is associated with insulin resistance, diabetes does not develop until there is some degree of failure of insulin secretion. Thus, when measured, insulin secretion in response to glucose or other stimuli is always lower in persons with T2DM than in control subjects matched for age, sex, weight, and equivalent glucose concentration.

Genetics

T2DM has a strong genetic component; concordance rates among identical twins are in the 40–80% range, but there is not a simple Mendelian pattern. It should be kept in mind, however, that twinning itself increases the risk of T2DM (because of intrauterine growth restriction) and this may distort estimates of genetic risk. Monozygotic twins have a lifetime concordance of T2DM of around 70%, indicating that shared environmental factors (including the prenatal environment) may play a large role in the development of T2DM, and dizygotic twins have a lifetime concordance of around 20–30%. The genetic basis for T2DM is complex and incompletely defined; no single identified defect predominates, as does the HLA association with T1DM. Genome-wide association studies have now identified certain genetic polymorphisms that are associated with increased T2DM risk in most populations studied; the most consistently identified are variants of the TCF7L2 (transcription factor 7—like 2) gene, which may have a role in β-cell function. Other identified risk alleles include variants in PPARG and KCNJ11-ABCC8 as well as many others. But to date, and together, all these identified variants explain only a small portion (probably less than 20%) of the population risk of diabetes and in many cases the mechanism by which these polymorphisms confer risk of T2DM is not clear so far. It is hoped that these will provide clues to the vexing problem of disease pathophysiology and address new venues for therapy.

Epigenetics and Fetal Programming

Low birthweight and intrauterine growth restriction are associated with increased risk of T2DM. This risk appears to be higher in low-birthweight infants who gain weight more rapidly in the 1st few years of life. These findings have led to the formulation of the thrifty phenotype hypothesis, which postulates that poor fetal nutrition somehow programs these children to maximize storage of nutrients and makes them more prone to future weight gain and development of diabetes. Epigenetic modifications may play a role in this phenomenon, given that so few of the known T2DM genes are associated with low birthweight, but the detailed molecular mechanisms involved have yet to be determined. Whatever the exact mechanism, altered methylation profiles and/or transcriptional dysregulation and histone modifications, prenatal and early childhood environments play an important role in the pathogenesis of T2DM and may do so by epigenetic modification of the DNA (in addition to other factors).

Environmental and Lifestyle-Related Risk Factors

Obesity is the most important lifestyle factor associated with development of T2DM. This, in turn, is associated with the intake of high-energy foods, physical inactivity, TV viewing (screen time), and low socioeconomic status (in developed countries). Maternal smoking also increases the risk of diabetes and obesity in the offspring. Increasingly, exposure to land pollutants and air pollutants is demonstrated to contribute to insulin resistance. The lipophilic nature of these organic pollutants and their consequent storage in adipose tissue may promote obesity and insulin resistance. In addition, sleep deprivation and psychosocial stress are associated with increased risk of obesity in childhood and with IGT in adults, possibly via over-activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Many antipsychotics (especially the atypical antipsychotics like olanzapine and quetiapine) and antidepressants (both tricyclic antidepressants and newer antidepressants like fluoxetine and paroxetine) induce weight gain. In addition to the risk conferred by increased obesity, some of these medications may also have a direct role in causing insulin resistance, β-cell dysfunction, leptin resistance, and activation of inflammatory pathways. To complicate matters further, there is evidence that schizophrenia and depression themselves increase the risk of T2DM and the metabolic syndrome, independent of the risk conferred by drug treatment. As a result, both obesity and T2DM are more prevalent in this population. Furthermore, with increasing use of antipsychotics and antidepressants in the pediatric population, this association is likely to become stronger.

Clinical Features

In the United States, T2DM in children is more likely to be diagnosed in Native American, Hispanic American, and African American youth, with the highest incidence being reported in Pima Indian youth. While cases may be seen as young as 4 yr of age, most are diagnosed in adolescence and incidence increases with increasing age. Family history of T2DM is present in practically all cases. Typically, patients are obese and present with mild symptoms of polyuria and polydipsia, or are asymptomatic and T2DM is detected on screening tests. Presentation with DKA occurs in up to 10% of cases. Physical examination frequently reveals the presence of acanthosis nigricans, most commonly on the neck and in other flexural areas. Other findings may include striae and an increased waist to hip ratio. Laboratory testing reveals elevated HbA1c levels. Hyperlipidemia characterized by elevated triglycerides and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels is commonly seen in patients with T2DM at diagnosis. Consequently, lipid screening is indicated in all new cases of T2DM. As well, the current recommendation is that blood pressure measurement, random urine albumin to creatinine ratio, and a dilated eye examination should be performed at diagnosis. Because hyperglycemia develops slowly, and patients may be asymptomatic for months or years after they develop T2DM, screening for T2DM is recommended in high-risk children (Table 607.15 ). The American Diabetes Association recommends that all youth who are overweight and have at least 2 other risk factors be tested for T2DM beginning at age 10 yr or at the onset of puberty and every 2 yr after that. Risk factors include family history of T2DM in first- or second-degree relatives, history of gestational diabetes in the mother, belonging to certain ethnic groups (i.e., Native American, African American, Hispanic, or Asian/Pacific Islander groups), and having signs of insulin resistance (e.g., acanthosis nigricans, hypertension, dyslipidemia, or polycystic ovary syndrome). The current recommendation is to use fasting blood glucose as a screening test, but some authorities now recommend that HbA1c be used as a screening tool. In borderline or asymptomatic cases, the diagnosis may be confirmed using a standard oral glucose tolerance test, but this test is not required if typical symptoms are present or fasting plasma glucose or HbA1c is clearly elevated on 2 separate occasions.

Table 607.15

Testing for Type 2 Diabetes in Children

|

• Criteria* Overweight (body mass index >85th percentile for age and sex, weight for height >85th percentile, or weight >120% of ideal for height) Any 2 of the following risk factors: Family history of type 2 diabetes in 1st- or 2nd-degree relative Race/ethnicity (Native American, African American, Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander) Signs of insulin resistance or conditions associated with insulin resistance (acanthosis nigricans, hypertension, dyslipidemia, polycystic ovary syndrome) • Age of initiation: age 10 yr or at onset of puberty if puberty occurs at a younger age |

* Clinical judgment should be used to test for diabetes in high-risk patients who do not meet these criteria.

From Type 2 diabetes in children and adolescents. American Diabetes Association, Diabetes Care 23:386, 2000. Reproduced by permission.

Treatment

T2DM is a progressive syndrome that gradually leads to complete insulin deficiency during the patient's life. A systematic approach for treatment of T2DM should be implemented according to the natural course of the disease, including adding insulin when hypoglycemic oral agent failure occurs. Nevertheless, lifestyle modification (diet and exercise) is an essential part of the treatment regimen, and consultation with a dietitian is usually necessary. This is particularly so because the largest pediatric clinical trial to date, the Treatment Options for Type 2 Diabetes in Adolescents and Youth (TODAY study), showed that oral agent monotherapy did not maintain lasting glucose control in close to half of those with T2DM.

There is no particular dietary or exercise regimen that has been conclusively shown to be superior and practitioners recommend a low-calorie, low-fat diet and 30-60 min of physical activity at least 5 times/wk. The ultimate goal is to bring the BMI below the 85% for age and gender, with attention to weight reduction versus maintenance depending on the age of the subject. Screen time should be limited to 1-2 hr/day. Children with T2DM often come from household environments with a poor understanding of healthy eating habits. Commonly observed behaviors include skipping meals, heavy snacking, and excessive daily television viewing, video game playing, and computer use. Adolescents engage in non–appetite-based eating (i.e., emotional eating, television-cued eating, boredom) and cyclic dieting (“yo-yo” dieting). Treatment in these cases is frequently challenging and may not be successful unless the entire family buys into the need to change their unhealthy lifestyle.

It is recommended, unless insulin needs to be used at the outset, that oral hypoglycemic agents be introduced at the time of diagnosis (Tables 607.16 and 607.17 ). Patients who present with DKA or with markedly elevated HbA1c (>9.0%) will require treatment with insulin using protocols similar to those used for treating T1DM. Once blood glucose levels are under control, most cases can be managed with oral hypoglycemic agents and lifestyle interventions, but some patients will continue to require insulin therapy. Ongoing care should include periodic review of weight and BMI, diet, and physical activity, blood glucose monitoring, and monitoring of HbA1c at 3 mo intervals. Frequency of home glucose monitoring can range from 3 to 4 times daily for those on multiple daily insulin injections, to twice daily for those on a stable insulin long-acting regimen or metformin.

Table 607.16

| MEDICATIONS | CLASS | MECHANISM OF ACTION | ROUTE | FDA-APPROVED AGE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pramlintide | Amylin analogue | Increases satiety, slows gastric emptying, and suppresses postprandial glucagon secretion, resulting in decreased postmeal glucose excursions | Subcutaneous injection | >18 yr |

| Metformin | Biguanide | Improves hepatic insulin sensitivity. Increases GLP-1 and PYY | Oral | 10-18 yr |

| Colesevelam* | Bile acid sequestrant | Increases GLP-1 secretion and may increase peripheral insulin sensitivity | Oral | >10 yr † |

|

Alogliptin* Linagliptin* Saxagliptin* Sitagliptin* |

DPP-4 inhibitors | Inhibits DPP-4 from degrading GLP-1 and GIP | Oral | >18 yr |

|

Albiglutide Dulaglutide Exenatide* Liraglutide* |

Glucagon-like peptide agonists | Increase release of GLP-1, which stimulates release of insulin | Subcutaneous injection | >18 yr |

| Afrezza | Rapid-acting insulin | Pulmonary absorption of regular human insulin into systemic circulation | Inhaled | >18 yr |

| Degludec* | Long-acting insulin | Addition of hexadecanoic acid to lysine allows for multihexamer depot for slow insulin release | Subcutaneous injection | Awaiting new drug application to FDA |

| Detemir | Long-acting insulin | Addition of a fatty acid to lysine facilitates insulin binding to albumin resulting in slow insulin release | Subcutaneous injection | ≥6 yr |

| Glargine u300 | Long-acting insulin | Substitution of glycine and addition of 2 arginines at the carboxy terminal causes crystallization at physiologic pH resulting in slow insulin release | Subcutaneous injection |

>18 yr for the u300 (300 units/mL) form >5 yr for the u100 (100 units/mL) form |

| Peglispro* | Long-acting insulin | Reversal of lysine and proline at the carboxy terminal with the addition of PEG results in slow insulin release | Subcutaneous injection |

Awaiting new drug application to FDA ≥3 yr for the nonpegylated lispro |

|

Nateglinide Repaglinide |

Meglitinides | Causes rapid secretion of insulin by acting on the ATP sensitive potassium channel of pancreatic beta cells | Oral | >18 yr |

|

Canagliflozin Dapagliflozin Empagliflozin* |

Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors | Promotes renal excretion of glucose at the level of the proximal tubule causing an osmotic diuresis | Oral | >18 yr |

* Ongoing clinical trials in pediatrics.

† Lipid lowering only, www.accessdata.fda.gov .

ATP, adenosine triphosphate; GIP, glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide; PEG, polyethylene glycol; PYY, peptide YY.

From Meehan C, Silverstein J: Treatment options for type 2 diabetes in youth remain limited. J Pediatr 170:20–27, 2016.

Table 607.17

Existing and Future Glucose-Lowering Therapeutic Options by Organ or Organ System

| PATHOPHYSIOLOGICAL DEFECT | GLUCOSE-LOWERING THERAPY | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Existing | Future (Phase 1-3 Clinical Trials) | ||

| Pancreatic β cell | Loss of cell mass and function; impaired insulin secretion | Sulfonylureas; meglitinides | Imeglimin |

| Pancreatic α cell | Dysregulated glucagon secretion; increased glucagon concentration | GLP-1 receptor agonist | Glucagon-receptor antagonists |

| Incretin | Diminished incretin response | GLP-1 receptor agonist; DPP-IV inhibitors | Oral GLP-1 receptor agonist; once-weekly DPP-IV inhibitors |

| Inflammation | Immune dysregulation | GLP-1 receptor agonist; DPP-IV inhibitors | Immune modulators; antiinflammatory agents |

| Liver | Increased hepatic glucose output | Metformin; pioglitazone | Glucagon-receptor antagonists |

| Muscle | Reduced peripheral glucose uptake; insulin resistance | Metformin; pioglitazone | Selective PPAR modulators |

| Adipose tissue | Reduced peripheral glucose uptake; insulin resistance | Metformin; pioglitazone | Selective PPAR modulators; FGF21 analogues; fatty acid receptor agonists |

| Kidney | Increased glucose reabsorption caused by upregulation of SGLT-2 receptors | SGLT-2 inhibitors | Combined SGLT-1/-2 inhibitors |

| Brain | Increased appetite; lack of satiety | GLP-1 receptor agonist | GLP-1-glucagon-gastric inhibitory peptide dual or triple agonists |

| Stomach or intestine | Increased rate of glucose absorption | GLP-1 receptor agonist; DPP-IV inhibitors; alpha-glucosidase inhibitors; pramlintide | SGLT-1 inhibitors |

| Colon (microbiome) | Abnormal gut microbiota | Metformin; GLP-1 receptor agonist; DPP-IV inhibitors | Probiotics |

DPP-IV inhibitors, dipeptidyl peptidase-IV inhibitors; FGF21, fibroblast growth factor 21; GIP, gastric inhibitory peptide; GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide-1; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor; SGLT-1/SGLT-2 inhibitors, sodium glucose co-transporter-1/sodium glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors.

From Chatterjee S, Khunti K, Davies MJ: Type 2 diabetes. Lancet 389:2239–2250, 2017, Table 1.

The most commonly used and the only FDA-approved oral agent for the treatment of T2DM in children and adolescents is metformin. Renal function must be assessed before starting metformin as impaired renal function has been associated with potentially fatal lactic acidosis. Significant hepatic dysfunction is also a contraindication to metformin use, although mild elevations in liver enzymes may not be an absolute contraindication. The usual starting dose is 500 mg once daily, with dinner to minimize the potential for side effects. This may be increased to a maximum dose of 2,000 mg/day. Abdominal symptoms are common early in the course of treatment, but in most cases they will resolve with time.

Other agents such as thiazolidinediones, sulfonylureas, acarbose, pramlintide, incretin mimetics, and sodium-glucose transport protein inhibitors are being used routinely in adults but are not used as commonly in pediatrics. While the number of classes of glucose-lowering medications has close to tripled in the past years, these have not been readily studied for use in children, nor therefore approved. Lastly, they have relatively weak glucose-lowering effects. Sulfonylureas are widely used in adults, but experience in pediatrics is limited. Sulfonylureas cause insulin release by closing the potassium channel (KATP ) on β-cells. They are occasionally used when metformin monotherapy is unsuccessful or contraindicated for some reason (use in certain forms of neonatal diabetes is discussed in the section on neonatal diabetes). Thiazolidinediones are not approved for use in pediatrics. Pramlintide (Symlin) is an analog of IAPP (islet amyloid polypeptide), which is a peptide that is co-secreted with insulin by the β-cells and acts to delay gastric emptying, suppress glucagon, and possibly suppress food intake. It is not yet approved for pediatric use. Incretins are gut-derived peptides like GLP-1, GLP-2, and GIP (glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide, previously known as gastric inhibitory protein) that are secreted in response to meals and act to enhance insulin secretion and action, suppress glucagon production, and delay gastric emptying (among other actions). GLP-1 analogs (e.g., exenatide) and agents that prolong endogenous GLP-1 action (e.g., sitagliptin) are now available for use in adults but are not yet approved for use in children; they may be associated with side effects such as hepatic injury and pancreatitis. The sodium-glucose transport protein (SGLT-2) inhibitors are a new class of glucose-lowering drugs. They act by blocking glucose reabsorption in the proximal renal tubule, but their effect is of course limited by the amount of glucose delivered to the tubule. As of this writing, these drugs are being studied in the pediatric population and may thus soon be approved for use. Lastly, bariatric surgical therapy, such as gastric bypass or banding, is not yet recommended for youth with T2DM, and while the experience is limited, it is growing such that long-term outcomes will be forthcoming. Guidelines are emerging that suggest that bariatric surgery may be indicated in certain conditions in late adolescence with BMI > 40 kg/m2 .

Complications

In the SEARCH study of diabetes in youth, 92% of the patients with T2DM had 2 or more elements of the metabolic syndrome (hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, decreased high-density lipoprotein, increased waist circumference), including 70% with hypertension. In addition, the incidence of microalbuminuria and diabetic retinopathy appears to be higher in T2DM than it is in T1DM. In the SEARCH study, the incidence of microalbuminuria among patients who had T2DM of less than 5 yr duration was 7–22%, while retinopathy was present in 18.3%. Thus, all adolescents with T2DM should be screened for hypertension and lipid abnormalities. Screening for microalbuminuria and retinopathy may be indicated even earlier than it is in T1DM. Treatment guidelines are the same as those for children with T1DM. Sleep apnea and fatty liver disease are being diagnosed with increasing frequency and may necessitate referral to the appropriate specialists. Complications associated with all forms of diabetes and recommendations for screening are noted in Table 607.13 ; Table 607.18 lists additional conditions particularly associated with T2DM.

Table 607.18

From Liu L, Hironaka K, Pihoker C: Type 2 diabetes in youth, Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 34:249–280, 2004.

Prevention

The difficulties in achieving good glucose control and preventing diabetes complications make prevention a compelling strategy. This is particularly true for T2DM, which is clearly linked to modifiable risk factors (obesity, a sedentary lifestyle). The Diabetes Prevention Program was designed to prevent or delay the development of T2DM in adult individuals at high risk by virtue of IGT. The Diabetes Prevention Program results demonstrated that intensified lifestyle or drug intervention in individuals with IGT prevented or delayed the onset of T2DM. The results were striking. Lifestyle intervention reduced the diabetes incidence by 58%; metformin reduced the incidence by 31% compared with placebo. The effects were similar for men and women and for all racial and ethnic groups. Lifestyle interventions are believed to have similar beneficial effects in obese adolescents with IGT. Screening is indicated for at-risk patients (see Table 607.13 ).

Other Specific Types of Diabetes

David R. Weber, Nicholas Jospe

Most cases of diabetes in children as well as adults fall into the 2 broad categories of type 1 and type 2 diabetes, but between 1% and 10% of cases are caused by single-gene disorders. These disorders include hereditary defects of β-cell function and insulin action, as well as rare forms of mitochondrial diabetes.

Genetic Defects of β-Cell Function

Transient Neonatal Diabetes Mellitus

Neonatal diabetes is transient in approximately 50% of cases, but after an interim period of normal glucose tolerance, 50–60% of these patients develop permanent diabetes (at an average age of 14 yr). There are also reports of patients with classic T1DM who formerly had transient diabetes as a newborn. It remains to be determined whether this association of transient diabetes in the newborn followed much later in life by classic T1DM is a chance occurrence or causally related (Fig. 607.9 ).

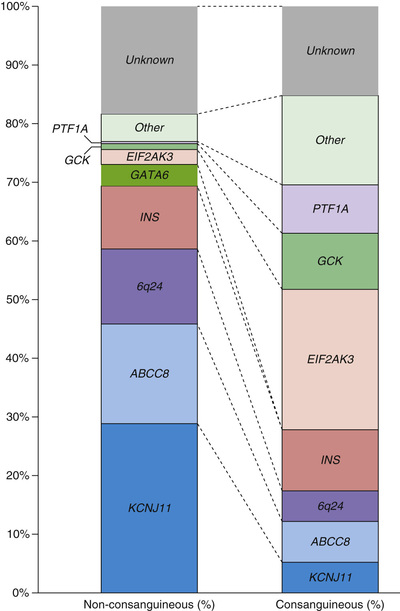

The syndrome of transient DM in the newborn infant has its onset in the 1st wk of life and persists several weeks to months before spontaneous resolution. Median duration is 12 wk. It occurs most often in infants who are small for gestational age and is characterized by hyperglycemia and pronounced glycosuria, resulting in severe dehydration and, at times, metabolic acidosis, but with only minimal or no ketonemia or ketonuria. There may also be findings such as umbilical hernia or large tongue. Insulin responses to glucose or tolbutamide are low to absent; basal plasma insulin concentrations are normal. After spontaneous recovery, the insulin responses to these same stimuli are brisk and normal, implying a functional delay in β-cell maturation with spontaneous resolution. Occurrence of the syndrome in consecutive siblings has been reported. About 70% of cases are due to abnormalities of an imprinted locus on chromosome 6q24, resulting in overexpression of paternally expressed genes such as pleomorphic adenoma gene–like 1 (PLAGL1/ZAC) and hydatidiform mole associated and imprinted (HYMAI). Most of the remaining cases are caused by mutations in KATP channels. Mutations in KATP channels also cause many cases of PND, but there is practically no overlap between the mutations that lead to transient neonatal DM and those causing permanent neonatal DM. This syndrome of transient neonatal DM should be distinguished from the severe hyperglycemia that may occur in hypertonic dehydration; that usually occurs in infants beyond the newborn period and responds promptly to rehydration with minimal or no requirement for insulin.

Administration of insulin is mandatory during the active phase of DM in the newborn. Rehydration and IV insulin is usually required initially; transition to subcutaneous insulin can occur once clinically stable. A variety of regimens including intermediate or long-acting insulin given in 1-2 daily doses or continuous insulin therapy with an insulin pump have been used successfully. The starting dose is typically 1-2 units/kg/day but will need to be adjusted based upon blood glucose levels. Attempts at gradually reducing the dose of insulin may be made as soon as recurrent hypoglycemia becomes manifested or after 2 mo of age. Genetic testing is now available for 6q24 abnormalities as well as potassium channel defects and should be obtained on all patients, and recurrence risk assessment by a genetic counselor is recommended.

Permanent Neonatal Diabetes Mellitus

Permanent DM in the newborn period is caused, in approximately 50% of the cases, by mutations in the KCNJ11 (potassium inwardly rectifying channel J, member 11) and ABCC8 (adenosine triphosphate–binding cassette, subfamily C, member 8) genes (see Figs. 607.9 and 607.10 ). These genes code for the Kir6.2 and SUR1 subunits of the adenosine triphosphate–sensitive potassium channel, which is involved in an essential step in insulin secretion by the β-cell. Some cases are caused by pancreatic agenesis as a result of homozygous mutations in the IPF-1 gene (where heterozygous mutations cause MODY4); homozygous mutations in the glucokinase gene (where heterozygous mutations cause MODY2); and mutations in the insulin gene. Almost all these infants are small at birth because of the role of insulin as an intrauterine growth factor. Instances of affected twins and families with more than 1 affected infant have been reported. Infants with permanent neonatal DM may be initially euglycemic and typically present between birth and 6 mo of life (mean age of presentation is 5 wk). There is a spectrum of severity and up to 20% have neurologic features. The most severely affected patients have the syndrome of d evelopmental delay, e pilepsy and n eonatal d iabetes (DEND syndrome ). Less-severe forms of DEND are labeled intermediate DEND or i-DEND.

Activating mutations in the KCNJ11 gene (encoding the adenosine triphosphate–sensitive potassium channel subunit Kir6.2) are associated with both transient neonatal DM and permanent neonatal DM, with particular mutations being associated with each phenotype. More than 90% of these patients respond to sulfonylureas (at higher doses than those used in T2DM), but patients with severe neurologic disease may be less responsive. Mutations in the ABCC8 gene (encoding the SUR1 subunit of this potassium channel) were thought to be less likely to respond to sulfonylureas (because this is the subunit that binds sulfonylurea drugs), but some of these mutations are reported to respond and patients have been successfully switched from insulin to oral therapy. Several protocols for switching the patient from insulin to glibenclamide are available and patients are usually stabilized on doses ranging from 0.4 to 1 mg/kg/day. Because approximately 50% of neonatal diabetics have K-channel mutations that can be switched to sulfonylurea therapy, with dramatic improvement in glycemic control and quality of life, all patients with diabetes diagnosed before 6 mo of age (and perhaps even those diagnosed before 12 mo of age) should have genetic testing.

Maturity-Onset Diabetes of Youth

Several forms of diabetes are associated with monogenic defects in β-cell function . Before these genetic defects were identified, this subset of diabetics was diagnosed on clinical grounds and described by the term MODY. This subtype of DM consists of a group of heterogeneous clinical entities that are characterized by onset before 25 yr, autosomal dominant inheritance, and a primary defect in insulin secretion. Strict criteria for the diagnosis of MODY include diabetes in at least 3 generations with autosomal dominant transmission and diagnosis before age 25 yr in at least 1 affected subject. Mutations have been found in at least 11 different genes, accounting for the dominantly inherited monogenic defects of insulin secretion, for which the term MODY is used. The American Diabetes Association groups these disorders together under the broader category of genetic defects of β-cell function . Eleven of these defects typically meet the clinical criteria for the diagnosis of MODY and are listed in Table 607.19 . Just 3 of them (MODY2, MODY3, and MODY5) account for 90% of the cases in this category in European populations, but the distribution may be different in other ethnic groups. Except for MODY2 (which is caused by mutations in the enzyme glucokinase), all other forms are caused by genetic defects in various transcription factors (see Table 607.19 ).

Table 607.19

Summary of MODY Types and Special Clinical Characteristics

| GENE MUTATED | FUNCTION | SPECIAL FEATURE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MODY1 | HNF4 α | Transcription factor | Decreased levels of triglycerides, apolipoproteins AII and CIII (5–10% of MODY), neonatal hypoglycemia, very sensitive to sulfonylureas |

| MODY2 | Glucokinase (GCK) | Enzyme, glucose sensor | Hyperglycemia of early onset but mild and nonprogressive; common (30–70% MODY) |

| MODY3 | HNF1 α | Transcription factor | Decreased renal absorption of glucose and consequent glycosuria; common (30–70% of cases of MODY); very sensitive to sulfonylureas |

| MODY4 | IPF-1 | Necessary for pancreatic development | Homozygous mutation causes pancreatic agenesis |

| MODY5 | HNF1β | Transcription factor | Renal malformations; associated with uterine abnormalities, hypospadias, joint laxity, and learning difficulties, pancreatic atrophy, pancreatic exocrine insufficiency; 5–10% of MODY |

| MODY6 | NEUROD1 | Differentiation factor in the development of pancreatic islets | Extremely rare |

| MODY7 | KFL11 | Zinc finger transcription factor | Early-onset type II diabetes mellitus |

| MODY8 | CEL | Bile salt–dependent lipase | Hyperglycemia; fecal elastase deficiency; exocrine pancreatic atrophy |

| MODY9 | PAX4 | Transcription factor | |

| MODY10 | INS | Insulin gene | Usually associated with neonatal diabetes |

| MODY11 | BLK | B-lymphocyte tyrosine kinase | Early-onset T1DM without autoantibodies |

View full size

MODY, maturity-onset diabetes of the young.

From Nakhla M, Polychronakos C: Monogenic and other unusual causes of diabetes mellitus, Pediatr Clin North Am 52:1637–1650, 2005.

MODY2

This is the second most common form of MODY and accounts for approximately 15–30% of all patients diagnosed with MODY. Glucokinase plays an essential role in β-cell glucose sensing and heterozygous mutations in this gene lead to mild reductions in pancreatic β-cell response to glucose. Homozygotes with the same mutations are completely unable to secrete insulin in response to glucose and develop a form of PND. Patients with heterozygous mutations have a higher threshold for insulin release but are able to secrete insulin adequately at higher blood glucose levels (typically 125 mg/dL [7 mmol/L] or higher). This results in a relatively mild form of diabetes (HbA1c is usually less than 7%), with mild fasting hyperglycemia and IGT in the majority of patients. MODY2 may be misdiagnosed as T1DM in children, gestational diabetes in pregnant women, or well-controlled T2DM in adults (see Table 607.14 ). An accurate diagnosis is important because most cases are not progressive, and except for gestational diabetes, may not require treatment. When needed, they can usually be treated with small doses of exogenously administered insulin. Treatment with oral agents (sulfonylureas and related drugs) can be successful and may be more acceptable to many patients.

MODY3

Patients affected with mutations in the transcription factor hepatocyte nuclear factor-1α show abnormalities of carbohydrate metabolism varying from IGT to severe diabetes and often progressing from a mild to a severe form over time. They are also prone to the development of vascular complications. This is the most common MODY subtype and accounts for 50–65% of all cases. These patients are very sensitive to the action of sulfonylureas and can usually be treated with relatively low doses of these oral agents, at least in the early stages of the disease. In children, this form of MODY is sometimes misclassified as T1DM and treated with insulin. Evaluation of autoimmune markers helps to rule out T1DM; genetic testing for MODY is now available and is indicated in patients with relatively mild diabetes and a family history suggestive of autosomal dominant inheritance. Accurate diagnosis can lead to avoidance of unnecessary insulin treatment and specific genetic counseling.

Less Common Forms of Monogenic Diabetes

Hepatocyte nuclear factor-4α (MODY1), insulin promoter factor (IPF)-1, also known as (PDX-1) (MODY4), hepatocyte nuclear factor 1β/TCF2 (MODY5), and NeuroD1 (MODY6) are all transcription factors that are involved in β-cell development and function and mutations in these lead to various rare forms of MODY. In addition to diabetes they can also have specific findings unrelated to hyperglycemia; for example, MODY1 is associated with low triglyceride and lipoprotein levels and MODY5 is associated with renal cysts and renal dysfunction. In terms of treatment, MODY1 and MODY4 may respond to oral sulfonylureas, but MODY5 does not respond to oral agents and requires treatment with insulin. NeuroD1 defects are extremely rare and not much is known about their natural history.

Primary or secondary defects in the glucose transporter-2, which is an insulin-independent glucose transporter, may also be associated with diabetes. Diabetes may also be a manifestation of a polymorphism in the glycogen synthase gene. This enzyme is crucially important for storage of glucose as glycogen in muscle. Patients with this defect are notable for marked insulin resistance and hypertension, as well as a strong family history of diabetes. Another form of IDDM is the Wolfram syndrome . Wolfram syndrome 1 is characterized by diabetes insipidus, DM, optic atrophy, and deafness—thus, the acronym DIDMOAD . Some patients with diabetes appear to have severe insulinopenia, whereas others have significant insulin secretion as judged by C-peptide. The overall prevalence is estimated at 1 in 770,000 live births. The sequence of appearance of the stigmata is as follows: non-autoimmune IDDM in the 1st decade, central diabetes insipidus and sensorineural deafness in two-third to three-quarters of the patients in the 2nd decade, renal tract anomalies in about half of the patients in the 3rd decade, and neurologic complications such as cerebellar ataxia and myoclonus in half to two-thirds of the patients in the 4th decade. Other features include primary gonadal atrophy in the majority of males and a progressive neurodegenerative course with neurorespiratory death at a median age of 30 yr. Some (but not all) cases are caused by mutations in the WFS-1 (wolframin) gene on chromosome 4p. Wolfram syndrome 2 has early-onset optic atrophy, DM, deafness, and a shortened life span but no diabetes insipidus; the associated gene is CISD2 . Other forms of Wolfram syndrome may be caused by mutations in mitochondrial DNA.

Mitochondrial Gene Defects

Point mutations in mitochondrial DNA are associated with the cause of maternally inherited DM and deafness . The most common mitochondrial DNA mutation in these cases is the point mutation m.3243A>G in the transfer RNA leucine gene. This mutation is identical to the mutation in MELAS (myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like syndrome), but this syndrome is not associated with diabetes; the phenotypic expression of the same defect varies. Diabetes in most of these cases presents insidiously but approximately 20% of patients have an acute presentation resembling T1DM. The mean age of diagnosis of diabetes is 37 yr, but cases have been reported as young as 11 yr; not all patients have deafness. This mutation has been estimated to be present in 1.5% of Japanese diabetics, which may be higher than the prevalence in other ethnic groups. Metformin should be avoided in these patients because of the theoretical risk of severe lactic acidosis in the presence of mitochondrial dysfunction. Some children with mitochondrial DNA mutations affecting complex I and/or complex IV may also develop diabetes.

Abnormalities of the Insulin Gene

Diabetes of variable degrees may also result from mutations in the insulin gene that impair the effectiveness of insulin at the receptor level. Insulin gene defects are exceedingly rare and may be associated with relatively mild diabetes or even normal glucose tolerance. Diabetes may also develop in patients with faulty processing of proinsulin to insulin (an autosomal dominant defect). These defects are notable for the high concentration of insulin as measured by radioimmunoassay, whereas MODY and glucose transporter-2 defects are characterized by relative or absolute deficiency of insulin secretion for the prevailing glucose concentrations.

Genetic Defects of Insulin Action

Various genetic mutations in the insulin receptor can impair the action of insulin at the insulin receptor or impair postreceptor signaling, leading to insulin resistance. The mildest form of the syndrome with mutations in the insulin receptor was previously known as type A insulin resistance. This condition is associated with hirsutism, hyperandrogenism, and cystic ovaries in females, without obesity. Acanthosis nigricans may be present and life expectancy is not significantly impaired. More severe forms of insulin resistance are seen in 2 mutations in the insulin receptor gene that cause the pediatric syndromes of Donohue syndrome (formerly called leprechaunism) and Rabson-Mendenhall syndrome.

Donohue Syndrome

This is a syndrome characterized by intrauterine growth restriction, fasting hypoglycemia, and postprandial hyperglycemia in association with profound resistance to insulin; severe hyperinsulinemia is seen during an oral glucose tolerance test. Various defects of the insulin receptor have been described, thereby attesting to the important role of insulin and its receptor in fetal growth and possibly in morphogenesis. Many of these patients die in the 1st year of life. Potential treatments include high-dose insulin, metformin, and continuous IGF-1 via insulin pump.

Rabson-Mendenhall Syndrome

This entity is defined by clinical manifestations that appear to be intermediate between those of acanthosis nigricans with insulin resistance type A and Donohue syndrome. The features include extreme insulin resistance, acanthosis nigricans, abnormalities of the teeth and nails, and pineal hyperplasia. It is not clear whether this syndrome is entirely distinct from Donohue syndrome; however, by comparison, patients with Rabson-Mendenhall tend to live significantly longer. Therapies with modest benefit have included IGF-1 and leptin.

Lipoatrophic Diabetes

Various forms of lipodystrophy are associated with insulin resistance and diabetes (Table 607.20 ). Familial partial lipoatrophy, or lipodystrophy, is associated with mutations in the LMNA gene, encoding nuclear envelope proteins lamin A and C. Severe congenital generalized lipoatrophy is associated with mutations in the seipin and AGPAT2 genes, but the mechanism by which these mutations lead to insulin resistance and diabetes is not known.

Table 607.20

Clinical and Biochemical Features of Inherited Lipodystrophies

| SUBTYPE | CONGENITAL GENERALIZED LIPODYSTROPHY | FAMILIAL PARTIAL LIPODYSTROPHY | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSCL1 | BSCL2 | FPLD2 | FPLD3 | |

| Defective gene | AGPAT2 | BSCL2 | LMNA | PPARG |

| Clinical onset | Soon after birth | Soon after birth | Puberty | Usually puberty, but may present in younger children |

| Fat distribution | Generalized absence | Generalized absence | Loss of limb and gluteal fat; typically excess facial and nuchal fat; trunk fat often lost | Loss of limb and gluteal fat; preserved facial and trunk fat |

| Cutaneous features | Acanthosis nigricans and skin tags; hirsutism common in women | Acanthosis nigricans and skin tags; hirsutism common in women | Acanthosis nigricans and skin tags; hirsutism common in women | Acanthosis nigricans and skin tags; hirsutism common in women |

| Musculoskeletal | Acromegaloid features common | Acromegaloid features common | Frequent muscle hypertrophy; some have overlap features of muscular dystrophy | Nil specific |

| Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease | Severe | Severe | Yes | Yes |

| Dyslipidemia | Severe associated with pancreatitis | Severe associated with pancreatitis | Yes, may be severe | Yes, may be severe |

| Insulin resistance | Severe early onset | Severe early onset | Severe | Severe; early onset in some |

| Diabetes onset | <20 yr | <20 yr | Variable; generally later in men than women | Variable; generally later in men than women |

| Hypertension | Common | Common | Common | Very common |

| Other | Mild mental retardation possible | |||

From Semple RK, Savage DB, Halsall DJ, O'Rahilly S: Syndromes of severe insulin resistance and/or lipodystrophy. In Weiss RE, Refetoff S, editors: Genetic diagnosis of endocrine disorders, Philadelphia, 2010, Elsevier, Table 4.2.

Stiff-Person Syndrome

This is an extremely rare autoimmune central nervous system disorder that is characterized by progressive stiffness and painful spasms of the axial muscles and very high titers of glutamic acid decarboxylase antibodies. About one third of the patients also develop T1DM.

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

In rare cases, patients with systemic lupus erythematosus may develop autoantibodies to the insulin receptor, leading to insulin resistance and diabetes.

Cystic Fibrosis–Related Diabetes

See Chapter 432 .

As patients with cystic fibrosis (CF) live longer, an increasing number are being diagnosed with cystic fibrosis–related diabetes (CFRD). Females appear to have a somewhat higher risk of CFRD than males and prevalence increases with increasing age until age 40 yr (there is a decline in prevalence after that, presumably because only the healthiest CF patients survive beyond that age). There is an association with pancreatic insufficiency and there may be a higher risk in patients with class I and class II CF transmembrane conductance regulator mutations. A large multicenter study in the United States reported prevalence (in all ages) of 17% in females and 12% in males. Cross-sectional studies indicate that the prevalence of IGT may be significantly higher than this and up to 65% of children with CF have diminished 1st phase insulin secretion, even when they have normal glucose tolerance. In Denmark, oral glucose tolerance screening of the entire CF population demonstrated no diabetes in patients younger than 10 yr, diabetes in 12% of patients age 10-19 yr, and diabetes in 48% of adults age 20 yr and older. At a Midwestern center where routine annual oral glucose tolerance screening is performed, only about half of children and a quarter of adults were found to have normal glucose tolerance.

Patients with CFRD have features of both T1DM and T2DM. In the pancreas, exocrine tissue is replaced by fibrosis and fat and many of the pancreatic islets are destroyed. The remaining islets demonstrate diminished numbers of β-, α-, and pancreatic polypeptide-secreting cells. Secretion of the islet hormones insulin, glucagon, and pancreatic polypeptide is impaired in patients with CF in response to a variety of secretagogues. This pancreatic damage leads to slowly progressive insulin deficiency, of which the earliest manifestation is an impaired 1st phase insulin response. As patients age, this response becomes progressively delayed and less robust than normal. At the same time, these patients develop insulin resistance due to chronic inflammation and the intermittent use of corticosteroids. Insulin deficiency and insulin resistance lead to a very gradual onset of IGT that eventually evolves into diabetes. In some cases, diabetes may wax and wane with disease exacerbations and the use of corticosteroids. The clinical presentation is similar to that of T2DM in that the onset of the disease is insidious and the occurrence of ketoacidosis is rare. Islet antibody titers are negative. Microvascular complications do develop but may do so at a slower rate than in typical T1DM or T2DM. Macrovascular complications do not appear to be of concern in CFRD, perhaps because of the shortened life span of these patients. Several factors unique to CF influence the onset and the course of diabetes. For example: (1) frequent infections are associated with waxing and waning of insulin resistance; (2) energy needs are increased because of infection and pulmonary disease; (3) malabsorption is common, despite enzyme supplementation; (4) nutrient absorption is altered by abnormal intestinal transit time; (5) liver disease is frequently present; (6) anorexia and nausea are common; (7) there is a wide variation in daily food intake based on the patient's acute health status; and (8) both insulin and glucagon secretion are impaired (in contrast to autoimmune diabetes, in which only insulin secretion is affected).

IGT and CFRD are associated with poor weight gain and there is evidence that treatment with insulin improves weight gain and slows the rate of pulmonary deterioration. Because of these observations, the CF Foundation/American Diabetes Association/Pediatric Endocrine Society guidelines recommend that routine diabetes screening of all children with CF begin at age 10 yr. Despite debate over the ideal screening modality, the current recommendation is the 2 hr glucose tolerance test, though it is possible that simply obtaining a single 2 hr postprandial glucose value may be sufficient. When hyperglycemia develops, the accompanying metabolic derangements are usually mild, and relatively low doses of insulin usually suffice for adequate management. Basal insulin may be started initially, but basal-bolus therapy similar to that used in T1DM will eventually be needed. Dietary restrictions are minimal as increased energy needs are present and weight gain is usually desired. Ketoacidosis is very uncommon but may occur with progressive deterioration of islet cell function. IGT is not necessarily an indication for treatment, but patients who have poor growth and inadequate weight gain may benefit from the addition of basal insulin even if they do not meet the criteria for diagnosis of diabetes.

Endocrinopathies

The endocrinopathies listed in Table 607.1 are only rarely encountered as a cause of diabetes in childhood. They may accelerate the manifestations of diabetes in those with inherited or acquired defects in insulin secretion or action.

Drugs

High-dose oral or parenteral steroid therapy usually results in significant insulin resistance leading to glucose intolerance and overt diabetes. The immunosuppressive agents cyclosporin and tacrolimus are toxic to β-cells, causing IDDM in a significant proportion of patients treated with these agents. Their toxicity to pancreatic β-cells was one of the factors that limited their usefulness in arresting ongoing autoimmune destruction of β-cells. Streptozotocin and the rodenticide Vacor are also toxic to β-cells, causing diabetes.

There are no consensus guidelines regarding treatment of steroid-induced hyperglycemia in children. Many patients on high-dose steroids have elevated blood glucose during the day and evening but become normoglycemic late at night and early in the morning. In general, significant hyperglycemia in an inpatient setting is treated with short-acting insulin on an as-needed basis. Basal insulin may be added when fasting hyperglycemia is significant. Outpatient treatment can be more difficult, but when treatment is needed, protocols similar to the basal-bolus regimens used in T1DM are used.

Genetic Syndromes Associated With Diabetes Mellitus

A number of rare genetic syndromes associated with IDDM or carbohydrate intolerance have been described (see Table 607.1 ). These syndromes represent a broad spectrum of diseases, ranging from premature cellular aging, as in the Werner and Cockayne syndromes (see Chapter 109 ) to excessive obesity associated with hyperinsulinism, resistance to insulin action, and carbohydrate intolerance, as in the Prader-Willi syndrome (see Chapters 97 and 98 ). Some of these syndromes are characterized by primary disturbances in the insulin receptor or in antibodies to the insulin receptor without any impairment in insulin secretion. Although rare, these syndromes provide unique models to understand the multiple causes of disturbed carbohydrate metabolism from defective insulin secretion or from defective insulin action at the cell receptor or postreceptor level.

Autoimmune Diseases Associated With T1DM

IPEX Syndrome

IPEX (immunodysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, and enteropathy, X-linked) is a genetic syndrome leading to autoimmune disease. In most patients with IPEX, mutations in the FOXP3 (forkhead box P3) gene, a specific marker of natural and adaptive regulatory T cells, leads to severe immune dysregulation and rampant autoimmunity. Autoimmune diabetes develops in > 90% of cases, usually within the 1st few weeks of life and is accompanied by enteropathy, failure to thrive, and other autoimmune disorders.

Autoimmune Polyendocrine Syndromes

Autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1 (APS-1, also known as APCED) is a syndrome of multiple endocrinopathy related to genetic mutation in the AIRE gene. It typically first manifests in infancy with recurrent mucocutaneous candidiasis, followed variably by hypocalcemia (autoimmune hypoparathyroidism), adrenal insufficiency (Addison disease), T1DM, hypothyroidism (Hashimoto), celiac disease, and other autoimmune conditions. Much more common is APS-2, which typically refers to the presence of Addison disease plus 1 other autoimmune disease. Alternate definitions consider the presence of any 2 autoimmune diseases to be consistent with the diagnosis of APS-2. Regardless, it is clear that any patient with an autoimmune disease is at increased risk for the development of T1DM (and any patient with T1DM is at increased risk of other autoimmune disease) and should be counseled regarding the signs/symptoms of new-onset diabetes. See Table 607.13 for recommendations regarding screening tests to look for other autoimmune disease in patients with T1DM.

Chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis (Hashimoto thyroiditis) is frequently associated with T1DM in children (see Chapter 582 ). About 20% of insulin-dependent diabetic patients have thyroid antibodies in their serum; the prevalence is 2-20 times greater than in control populations. Only a small proportion of these patients acquire clinical hypothyroidism; the interval between diagnosis of diabetes and thyroid disease averages about 5 yr. Celiac disease, which is caused by hypersensitivity to dietary gluten, is another autoimmune disorder that occurs with significant frequency in children with T1DM (see Chapter 364.2 ). It is estimated that approximately 7–15% of children with T1DM develop celiac disease within the 1st 6 yr of diagnosis, and the incidence of celiac disease is significantly higher in children younger than 4 yr of age and in females. Young children with T1DM and celiac disease can present with gastrointestinal symptoms (abdominal cramping, diarrhea, constipation, gastroesophageal reflux), growth failure as a consequence of suboptimal weight gain, unexplained hypoglycemic reactions because of nutrient malabsorption, and less commonly hypocalcemia due to severe vitamin D malabsorption; in some cases the disease can be asymptomatic.

When diabetes and thyroid disease coexist, the possibility of autoimmune adrenal insufficiency should be considered. It may be heralded by decreasing insulin requirements, increasing pigmentation of the skin and buccal mucosa, salt craving, weakness, asthenia and postural hypotension, or even frank adrenal crisis. This syndrome is unusual in the 1st decade of life, but it may become apparent in the 2nd decade or later.

Circulating antibodies to gastric parietal cells and to intrinsic factor are 2-3 times more common in patients with T1DM than in control subjects. The presence of antibodies to gastric parietal cells is correlated with atrophic gastritis and antibodies to intrinsic factor are associated with malabsorption of vitamin B12 . However, megaloblastic anemia is rare in children with T1DM.

Bibliography

Epidemiology, Etiology, Pathology, Classification, and Prevention

Achenbach P, Hummel M, Thümer L, et al. Characteristics of rapid vs slow progression to type 1 diabetes in multiple islet autoantibody-positive children. Diabetologia . 2013;56:1615–1622.

Ali K, Harnden A, Edge JA. Type 1 diabetes in children. BMJ . 2011;342:d294.

American Diabetes Assocition. Children and adolescents. Diabetes Care . 2016;39(Suppl 1):S86–S93.

American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care . 2014;37(Suppl 1):S81–S90.

American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes – 2017. Diabetes Care . 2017;40(Suppl 1):S1–S135.

Atkinson MA, Eisenbarth GS, Michels AW. Type 1 diabetes. Lancet . 2014;383:69–78.

Bach JF. Anti-CD3 antibodies for type 1 diabetes: beyond expectations. Lancet . 2011;378:459–460.

Bach JF, Chatenoud L. The hygiene hypothesis: an explanation for the increased frequency of insulin-dependent diabetes. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med . 2012;2(2):a007799.

Bergenstal RM, Gal RL, Connor CG, et al. Racial differences in the relationship glucose concentrations and hemoglobin A1c levels. Ann Intern Med . 2017;167(2):95–102.

Boerner BP, Sarvetnick NE. Type 1 diabetes: role of intestinal microbiome in humans and mice. Ann NY Acad Sci . 2011;1243:103–118.

Bonifacio E. Targeting innate immunity in type 1 diabetes: strike one. Lancet . 2013;381:1880–1881.

Cardwell CR, Carson DJ, Patterson CC. No association between routinely recorded infections in early life and subsequent risk of childhood-onset type 1 diabetes: a matched case-control study using the UK General Practice Research Database. Diabet Med . 2008;25:261–267.

Choudhary P. Insulin pump therapy with automated insulin suspension: toward freedom from nocturnal hypoglycemia. JAMA . 2013;310:1235–1236.

Concannon P, Rich SS, Nepom GT. Genetics of type 1A diabetes. N Engl J Med . 2009;360:1646–1654.

Dabelea D. The accelerating epidemic of childhood diabetes. Lancet . 2009;373:1999–2000.

Dabelea D, Bell RA, D'Agostino RB Jr, et al. Incidence of diabetes in youth in the United States. JAMA . 2007;297:2716–2724.

DiMeglio LA, Evans-Molina C, Oram RA. Type 1 diabetes. Lancet . 2018;391:2449–2458.

Dunger DB, Todd JA. Prevention of type 1 diabetes: what next? Lancet . 2008;372:1710–1711.

Frohlich-Reiterer EE, Kaspers S, Hofer S, et al. Anthropometry, metabolic control, and follow-up in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus and biopsy-proven celiac disease. J Pediatr . 2011;158:589–593.

Frederiksen B, Kroehl M, Lamb M, et al. Infant exposures and development of Type 1 diabetes mellitus: the Diabetes Autoimmunity Study in the Young (DAISY). JAMA Pediatr . 2013;167(9):808–815.

Graves PM, Barriga KJ, Norris JM, et al. Lack of association between early childhood immunizations and beta-cell autoimmunity. Diabetes Care . 1999;22:1694–1697.

Groop L. Open chromatin and diabetes risk. Nat Genet . 2010;42:190–192.

Hagopian W, Lee HS, Liu E, et al. Co-occurrence of type 1 diabetes and celiac disease autoimmunity. Pediatrics . 2017;149(5):e20171305.

Hober D, Same F. Enteroviruses and type 1 diabetes. BMJ . 2010;341:c7072.

Hoppu S, Ronkainen MS, Kimpimäki T, et al. Insulin autoantibody isotypes during the prediabetic process in young children with increased genetic risk of type I diabetes. Pediatr Res . 2004;55:236–242.

Hummel K, McFann KK, Realsen J, et al. The increasing onset of type 1 diabetes in children. J Pediatr . 2012;161:652–657.

Hummel SP, Fluger M, Hummel M, et al. Primary dietary intervention study to reduce the risk of islet autoimmunity in children at increased risk for type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care . 2011;34:1301–1305.

Ierodiakonou D, Garcia-Larsen V, Logan A, et al. Timing of allergenic food introduction to the infant diet and risk of allergic or autoimmune disease. JAMA . 2016;316(11):1181–1192.

Imperatore G, Boyle JP, Thompson TJ, SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study Group, et al. Projections of type 1 and type 2 diabetes burden in the U.S. population aged <20 years through 2050: dynamic modeling of incidence, mortality, and population growth. Diabetes Care . 2012;35:2515–2520.

Insel RA, et al. Staging Presymptomatic Type 1 Diabetes: a scientific statement of JDRF, the Endocrine Society, and the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care . 2015;38(10):1964–1974.

Karavanaki K, Tsoka E, Liacopoulou M, et al. Psychological stress as a factor potentially contributing to the pathogenesis of Type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Endocrinol Invest . 2008;31:406–415.

Kemppainen KM, Ardissone AN, Davis-Richardson AG, The TEDDY Study Group, et al. Early childhood gut microbiomes show strong geographic differences among subjects at high risk for type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care . 2015;38(2):329–332.

Knip M, Akerblom HK, Becker D, et al. Hydrolyzed infant formula and early β-cell autoimmunity a randomized clinical trial. JAMA . 2014;311:2279–2286.

Krischer JP, Lynch KF, Schatz DA, TEDDY Study Group, et al. The 6 year incidence of diabetes-associated autoantibodies in genetically at-risk children: the TEDDY study. Diabetologia . 2015;58(5):980–987.

Kurppa K, Laitinen A, Agardh D. Coeliac disease in children with type 1 diabetes. Lancet . 2018;2:133–142.

Lima BS, Ghaedi H, Daftarian N, et al. c.376G>A mutation in WFS1 gene causes Wolfram syndrome without deafness. Eur J Med Genetics . 2016;59:65–69.

Mathieu C, Gillard P. Arresting type 1 diabetes after diagnosis: GAD is not enough. Lancet . 2011;378:291–292.

Livingstone SJ, Levin D, Looker HC, et al. Estimated life expectancy in a Scottish cohort with type 1 diabetes, 2008-2010. JAMA . 2014;313(1):37–44.

Mayer-Davis EJ, Lawrence JM, Dabelea D, et al. Incidence trends of type 1 and type 2 diabetes among youths, 2002-2012. N Engl J Med . 2017;376(15):1419–1429.

Mohr SB, Garland CF, Gorham ED, et al. The association between ultraviolet B irradiance, vitamin D status and incidence rates of type 1 diabetes in 51 regions worldwide. Diabetologia . 2008;51:1391–1398.

Mortensen HB, Hougaard P, Swift P, et al. New definition for the partial remission period in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care . 2009;32:1384–1390.

Nanto-Salonen K, Kupila A, Simell S, et al. Nasal insulin to prevent type 1 diabetes in children with HLA genotypes and autoantibodies conferring increased risk of disease: a double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Lancet . 2008;372:1746–1755.

Nejentsev S, Howson JM, Walker NM, et al. Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium, Localization of type 1 diabetes susceptibility to the MHC class I genes HLA-B and HLA-A. Nature . 2007;450:887–892.

Oron T, Gat-Yablonski G, Lazar L, et al. Stress hyperglycemia: a sign of familial diabetes in children. Pediatrics . 2011;128:e1614–e1617.

Patterson CC, Dahlquist GG, Gyurus E, et al. Incidence trends for childhood type 1 diabetes in Europe during 1989–2003 and predicted new cases 2005–20: a multicentre prospective registration study. Lancet . 2009;373:2027–2033.

Quinn M, Fleishman A, Rosner B, et al. Characteristics at diagnosis of type 1 diabetes in children younger than 6 years. J Pediatr . 2006;148:366–371.

Redondo MJ, Jeffrey J, Fain PR, et al. Concordance for islet autoimmunity among monozygotic twins. N Engl J Med . 2008;359:2849–2850.

Richardson SJ, Willcox A, Bone AJ, et al. The prevalence of enteroviral capsid protein vp1 immunostaining in pancreatic islets in human type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia . 2009;52:1143–1151.

Roep BO. New hope for immune intervention therapy in type 1 diabetes. Lancet . 2011;378:376–378.

Sadauskaite-Kuehne V, Ludvigsson J, Padaiga Z, et al. Longer breastfeeding is an independent protective factor against development of type 1 diabetes mellitus in childhood. Diabetes Metab Res Rev . 2004;20:150–157.

Selvin E, Steffes MW, Gregg E, et al. Performance of A1c for the classification and prediction of diabetes. Diabetes Care . 2011;34(1):84–89.

Smyth DJ, Plagnol V, Walker NM, et al. Shared and distinct genetic variants in type 1 diabetes and celiac disease. N Engl J Med . 2008;359:2767–2776.

Tuomi T, Santoro N, Caprio S, et al. The many faces of diabetes: a disease with increasing heterogeneity. Lancet . 2014;383:1084–1092.

Vaarala O. Human intestinal microbiota and type 1 diabetes. Curr Diab Rep . 2013;13:601–607.

Wherrett DK, Bundy B, Becker DJ, et al. Antigen-based therapy with glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) vaccine in patients with recent-onset type 1 diabetes: a randomized double-blind trial. Lancet . 2011;378:319–326.

Whincup PH, Kaye SJ, Owen CG, et al. Birth weight and risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. JAMA . 2008;300:2886–2897.

Writing Group for the TRIGR Study Group. Effect of hydrolyzed infant formula vs conventional formula on risk of type 1 diabetes – The TRIGR randomized clinical trial. JAMA . 2018;319(1):38–48.

Writing Group for the TRIGR Study Group. Effect of oral insulin on prevention of diabetes in relatives of patients with type 1 diabetes – a randomized clinical trial. JAMA . 2017;318(19):1891–1902.

Yeung WC, Rawlinson WD, Craig ME. Enterovirus infection and type 1 diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational molecular studies. BMJ . 2011;342:d35.

Ziegler AG, Rewers M, Simell O, et al. Seroconversion to multiple islet autoantibodies and risk of progression to diabetes in children. JAMA . 2013;309:2473–2479.

Zipitis CS, Akobeng AK. Vitamin D supplementation in early childhood and risk of type 1 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child . 2008;93:512–517.

Genetics

Aly TA, Ide A, Jahromi MM, et al. Extreme genetic risk for type 1A diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA . 2006;103:14074–14079.

Gillespie K, Bain SC, Barnett AH, et al. The rising incidence of childhood type 1 diabetes and reduced contribution of high-risk HLA haplotypes. Lancet . 2004;364:1699–1700.

Gullstrand C, Wahlberg J, Ilonen J, et al. Progression to type 1 diabetes and autoantibody positivity in relation to HLA-risk genotypes in children participating in the ABIS study. Pediatr Diabetes . 2008;9(3 Pt 1):182–190.

Mayer-Davis EJ, Bell RA, Dabelea D, et al. The many faces of diabetes in American youth: type 1 and type 2 diabetes in five race and ethnic populations: the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study. Diabetes Care . 2009;32(Suppl 2):S99–S101.

Oram RA, Patel K, Hill A, et al. A type 1 diabetes genetic risk score can aid discrimination between type 1 and type 2 diabetes in young adults. Diabetes Care . 2016;39:337–344.

Pociot F, Lernmark A. Genetic risk factors for type 1 diabetes. Lancet . 2016;387:2331–2339.

Siljander HT, Veijola R, Reunanen A, et al. Prediction of type 1 diabetes among siblings of affected children and in the general population. Diabetologia . 2007;50:2272–2275.

Stankov K, Benc D, Draskovic D. Genetic and epigenetic factors in etiology of diabetes mellitus type 1. Pediatrics . 2013;132:1112–1122.

Diabetic Ketoacidosis

Dabelea D, Rewers A, Stafford JM, et al. Trends in the prevalence of ketoacidosis at diabetes diagnosis: the SEARCH for diabetes in youth study. Pediatrics . 2014;133:e938–e945.

Dunger DB, Sperling MA, Acerini CL, et al. European Society for Pediatric Endocrinology/Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society consensus statement on diabetic ketoacidosis in children and adolescents. Pediatrics . 2004;113:e133–e140.

Edge JA, Jakes RW, Roy Y, et al. The UK case-control study of cerebral edema complicating diabetic ketoacidosis in children. Diabetologia . 2006;49:2002–2009.

Fiordalisi I, Novotny WE, Holbert D, Critical Care Management Group, et al. An 18-yr prospective study of pediatric diabetic ketoacidosis: an approach to minimizing the risk of brain herniation during treatment. Pediatr Diabetes . 2007;8:142–149.

Glaser NS, Wootton-Gorges SL, Buonocore MH, et al. Subclinical cerebral edema in children with diabetic ketoacidosis randomized to 2 different rehydration protocols. J Pediatr . 2013;131:e73–e80.

Glaser NS, Wootton-Gorges SL, Marcin JP, et al. Mechanism of cerebral edema in children with diabetic ketoacidosis. J Pediatr . 2004;145:164–171.

Hom J, Sinert R. Evidence-based emergency medicine/critically appraised topic. Is fluid therapy associated with cerebral edema in children with diabetic ketoacidosis? Ann Emerg Med . 2008;52:69–75.

Kamel KS, Halperin ML. Acid-base problems in diabetic ketoacidosis. N Engl J Med . 2015;372(6):546–554.

Karges B, Schwandt A, Heidtmann B, et al. Association of insulin pump therapy vs insulin injection therapy with severe hypoglycemia, ketoacidosis, and glycemic control among children, adolescents, and young adults with type 1 diabetes. JAMA . 2017;318(14):1358–1366.

Klingensmith GJ, Tamborlane WV, Wood J, et al. Diabetic ketoacidosis at diabetes onset: still an all too common threat in youth. J Pediatr . 2013;162:330–334.

Kuppermann N, Ghetti S, Schunk JE, et al. Clinical trail of fluid infusion rates for pediatric diabetic ketoacidosis. N Engl J Med . 2018;378(24):2275–2287.

Lawrence SE, Cummings EA, Gaboury I, et al. Population-based study of incidence and risk factors for cerebral edema in pediatric diabetic ketoacidosis. J Pediatr . 2005;146:688–692.

Muir AB, Quisling RG, Yang MCK, et al. Cerebral edema in childhood diabetic ketoacidosis: natural history, radiographic findings, and early identification. Diabetes Care . 2004;27:1541–1546.

Rosenbloom AL. The management of diabetic ketoacidosis in children. Diabetes Ther . 2010;1(2):103–120.

Veverka M, Marsh K, Norman S, et al. A pediatric diabetic ketoacidosis management protocol incorporating a two-bag intravenous fluid system decreases duration of intravenous insulin therapy. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther . 2016;21(6):512–517.

Yadav D, Nair S, Norkus EP, Pitchumoni CS. Nonspecific hyperamylasemia and hyperlipasemia in diabetic ketoacidosis: incidence and correlation with biochemical abnormalities. Am J Gastroenterol . 2000;95(11):3123–3128.

Zeitler P, Haqq A, Rosenbloom A, et al. Hyperglycemic hyperosmolar syndrome in children: pathophysiological considerations and suggested guidelines for treatment. J Pediatr . 2011;158(1):9–14.

Management of Type 1 Diabetes in Children

Alemzadeh R, Berhe T, Wyatt DT. Flexible insulin therapy with glargine insulin improved glycemic control and reduced severe hypoglycemia among preschool-aged children with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Pediatrics . 2005;115:1320–1324.

Alemzadeh R, Palma-Sisto P, Holzum MK, et al. Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion attenuated glycemic instability in preschool children with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Technol Ther . 2007;9:339–347.

Bergenstal RM, Klonoff DC, Garg SK, et al. Threshold-based insulin-pump interruption for reduction of hypoglycemia. N Engl J Med . 2013;369:224–232.

Cameron FJ, Wherrett DK. Care of diabetes in children and adolescents: controversies, changes, and consensus. Lancet . 2015;385:2096–2104.

Chase HP, Lutz K, Pencek R, et al. Pramlintide lowered glucose excursions and was well-tolerated in adolescents with type 1 diabetes: results from a randomized, single-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. J Pediatr . 2009;155:369–373.

Chiang JL, Kirkman MS, Laffel LMB, et al. Type 1diabetes through the life span: a position statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care . 2014;37:2034–2054.

de Kort H, de Koning EJ, Rabelink TJ, et al. Islet transplantation in type 1 diabetes. BMJ . 2011;342:d217.

Donaghue KC, Wadwa RP, Dimeglio LA, et al. Microvascular and macrovascular complications in children and adolescents. Pediatr Diabetes . 2014;15(Suppl 20):257–269.

Farmer A. Use of HbA1C in the diagnosis of diabetes. BMJ . 2012;345:e7293.

El-Khatib F, Balliro C, Hillard MA, et al. Home use of a bihormonal bionic pancreas versus insulin pump therapy in adults with type 1 diabetes: a multicenter randomized crossover trial. Lancet . 2017;389:369–380.

Forlenza GP, Buckingham B, Maahs DM. Progress in diabetes technology: developments in insulin pumps, continuous glucose monitor, and progress towards the artificial pancreas. J Pediatr . 2016;169:13–20.

Garg SK, Weinzimer SA, Tamborlane WV, et al. Glucose outcomes with the in-home use of a hybrid closed-loop insulin delivery system in adolescents and adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther . 2017 [epub ahead of print].

Kapellen TM, Heidtmann B, Lilienthal E, et al. Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion in neonates and infants below 1 year: analysis of initial bolus and basal rate based on the experiences from the German Working Group for Pediatric Pump Treatment. Diabetes Technol Ther . 2015;17(12):872–879.

Lane W, Bailey TS, Gerety G, et al. Effect of insulin degludec vs insulin glargine U100 on hypoglycemia in patients with type 1 diabetes—The SWITCH 1 randomized clinical trial. JAMA . 2017;318(1):33–44.

Lennerz BS, Barton A, Bernstein RK, et al. Management of type 1 diabetes with a very low carbohydrate diet. Pediatrics . 2018;141(6):e20173349.

Libman IM, Miller KM, DiMeglio LA, et al. Effect of metformin added to insulin on glycemic control among overweight/obese adolescents with type 1 diabetes. [for the; T1D Exchange Clinical Network Metformin RCT Study Group] JAMA . 2015;314(21):2241–2250.

Ly TT, Nicholas JA, Retterath A, et al. Effect of sensor-augmented insulin pump therapy and automated insulin suspension vs standard insulin pump therapy on hypoglycemia in patients with type 1 diabetes—a randomized clinical trial. JAMA . 2013;310:1240–1246.

The Medical Letter. Insulin degludec/liraglutide (xultophy 100/3.6) for type 2 diabetes. Med Lett . 2017;59(1529):147–150.

The Medical Letter. MiniMed 530G: an insulin pump with low-glucose suspend automation. Med Lett Drugs Ther . 2013;55:97–98.

The Medical Letter. Minimed 67OG: a hybrid closed-loop insulin delivery system. Med Lett . 2016;58(1508):147–148.

Okawa T, Tsunekawa S, Seino Y, et al. Deceptive HbA1c in a patient with pure red cell aplasia. Lancet . 2013;382:366–367.

Phillip M, Battelino T, Atlas E, et al. Nocturnal glucose control with an artificial pancreas at a diabetes camp. N Engl J Med . 2013;368:824–832.

Raman VS, Heptulla RA. New potential adjuncts to treatment of children with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Pediatr Res . 2009;65:370–374.

Regan FM, Dunger DB. Use of new insulins in children. Arch Dis Child . 2006;91:ep47–ep53.

Runge C, Lee JM. How low can you go? Does lower carb translate to lower glucose? Pediatrics . 2018;141(6):e20180957.

Russell SJ, El-Khatib FH, Sinha M, et al. Outpatient glycemic control with a bionic pancreas in type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med . 2014;371:313–324.

Smart CE, Annan F, Bruno LPC, et al. Nutritional management in children and adolescents with diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes . 2014;15(Suppl 20):135–153.

Staeva TP, Chatenoud L, Insel R, et al. Recent lessons learned from prevention and recent-onset type 1 diabetes immunotherapy trials. Diabetes . 2013;62:9–17.

Taplin CE, Cobry E, Messer L, et al. Preventing post-exercise nocturnal hypoglycemia in children with type 1 diabetes. J Pediatr . 2010;157:784–788.

Turksoy K, Frantz N, Quinn L, et al. Automated insulin delivery – the light at the end of the tunnel. J Pediatr . 2017;186:17–28.