Chapter 57 NURSING MANAGEMENT: the patient with a stroke

1. Describe the incidence of and risk factors for stroke.

2. Explain the mechanisms that affect cerebral blood flow.

3. Compare and contrast the aetiology and pathophysiology of ischaemic and haemorrhagic strokes.

4. Correlate the clinical manifestations of stroke with the underlying pathophysiology.

5. Identify diagnostic studies performed for patients with a stroke.

6. Analyse the multidisciplinary care, drug therapy and nutritional therapy for a patient with a stroke.

7. Evaluate the acute nursing management of the patient with a stroke.

8. Describe the rehabilitative nursing management of the patient with a stroke.

9. Explain the psychosocial impact of a stroke on the patient and family.

Stroke

Stroke occurs when there is ischaemia (inadequate blood flow) to a part of the brain or haemorrhage into the brain resulting in death of brain cells. Functions that were controlled by the affected area of the brain (e.g. movement, sensation or emotions) are lost or impaired. The severity of the loss of function varies according to the location and the extent of the brain involved.

Stroke is a major public health concern. Each year an estimated 60,000 people in Australia and 6000 people in New Zealand will suffer a new or recurrent stroke. A quarter of all strokes occur in people under 65, although 40 strokes a year in New Zealand are suffered by children.1,2 Stroke is the second most common cause of death in Australia3 and the third most common cause in New Zealand.2 Stroke kills more women than breast cancer, and around 10% of stroke deaths occur in people under 65. A further increase in stroke incidence can be expected due to the ageing population. Indigenous Australians and Māori are at a higher risk of stroke than the general population.2,3 Māori aged over 55 years have a much higher mortality rate from stroke than the general New Zealand population,4 and the incidence of stroke in Indigenous Australians is nearly twice as high as in the general Australian population.5

Stroke is also a leading cause of serious, long-term disability. Over a lifetime, four out of five families will be affected by stroke. There are an estimated 350,000 stroke survivors in Australia and 45,000 in New Zealand.2,3 For individuals who have their first stroke, 20% will die in the first month and 33% will die within 1 year.6 The percentages are higher for people aged 65 and older. Of those who survive, the majority will be disabled at least in the early stages of stroke and approximately 50% will still be dependent on others for activities of daily living (ADLs) after 1 year. Common long-term disabilities include hemiparesis, inability to walk, complete or partial dependence for ADLs and aphasia.

In addition to the physical, cognitive and emotional impacts of stroke on stroke survivors and their families, stroke has an enormous financial impact. The annual direct and indirect costs of stroke are estimated to be in the order of A$2.14 billion in Australia1 and NZ$138 million (for hospital services alone) in New Zealand.2

RISK FACTORS FOR STROKE

The most effective way to decrease the burden of stroke is prevention. With the majority of strokes being first-ever strokes, awareness and control of modifiable risk factors can have a greater impact on reducing the incidence and burden of stroke than prevention of recurrent stroke. Risk factors can be divided into non-modifiable and modifiable. Stroke risk increases several-fold with multiple risk factors.

Non-modifiable risk factors include age, gender, race and heredity. Stroke risk increases with age, doubling each decade after age 55. Although stroke can occur at any age, 75–80% of people who have a stroke are 60 years old or over.3 The overall incidence and prevalence of stroke are almost equal for men and women, but women die more often than men from stroke. The preponderance of death from stroke in women is due to women living longer than men and therefore having more opportunity to suffer a stroke. The higher incidence of stroke in Indigenous Australians and Māori may be related, in part, to their higher incidence of hypertension, obesity and diabetes mellitus.4,5 A family history of stroke, a prior transient ischaemic attack or a prior stroke also increase the risk of stroke.

Modifiable risk factors are those that can potentially be altered through lifestyle changes and medical treatment, thus reducing the risk of stroke (see Box 57-1). Hypertension is the single most important modifiable risk factor but it is still often undetected and inadequately treated. Increases in systolic and diastolic blood pressures independently increase the risk of stroke. Stroke risk can be reduced by about one-third by lowering systolic blood pressure by 10 mmHg.4,6,7

Heart disease, including atrial fibrillation (AF), myocardial infarction, cardiomyopathy, cardiac valve abnormalities and cardiac congenital defects, is another risk factor. Of these, AF is the most important treatable cardiac-related risk factor.8,9 The incidence of AF increases with age. Following myocardial infarction, nearly 8% of men and 11% of women will have a stroke within 6 years. Diabetes mellitus is also a significant risk factor for stroke.1,2,4,6 Although tight control of hypertension in persons with diabetes significantly decreases stroke risk, tight control of blood glucose levels has not been shown to have the same effect.10

Increased serum cholesterol levels has been shown to have an association with stroke in persons with coronary heart disease.11,12 Smoking nearly doubles the risk of stroke.1,2,12 Fortunately, the risk associated with smoking decreases over time after quitting smoking and is reduced to that of a non-smoker after 5 years of quitting. Asymptomatic carotid stenosis, which can be detected by the presence of a cervical bruit or by ultrasound testing, is another risk factor.4,7,12

Other modifiable risk factors include lifestyle habits, such as excessive alcohol consumption, obesity, physical inactivity, poor diet and drug abuse. The effect of alcohol on stroke risk appears to depend on the amount consumed. Moderate alcohol consumption (≤2 drinks/day) may be protective but heavy alcohol consumption (>2 drinks/day) is associated with increased risk.13 Abdominal obesity in men increases stroke risk, and obesity and weight gain in women increase the risk of ischaemic stroke but not haemorrhagic stroke. In addition, obesity is also associated with conditions such as hypertension, high blood glucose levels and elevated blood lipid levels, which also increase stroke risk.

An association between physical inactivity and increased stroke risk is present in both men and women. The benefits of physical activity can occur with even light-to-moderate regular activity and may be partly related to the beneficial effects of exercise on other risk factors. The effect of diet on stroke risk is not clear, although a diet high in saturated fat and low in fruits and vegetables may increase stroke risk. Illicit drug use, most commonly cocaine, has been associated with stroke risk.12,13

Oral contraceptives have been associated with increased risk of stroke. One study suggests that oral contraceptives increase the levels of activated protein of the intrinsic coagulation system in young women, thereby increasing the risk of ischaemic stroke.14 The absolute risk is low, however, given modern oral contraceptives are lower in dose and the low incidence of stroke in this group of individuals. Other conditions that may increase stroke risk include migraine headaches, inflammatory states and hyperhomocysteinaemia; the reasons for this increase remains unclear, but the data show a minor increase in stroke risk.

Hypercoagulation disorders predispose to vascular occlusive diseases, including ischaemic stroke, especially in younger adults.14 Sickle cell disease is another known risk factor for stroke.15

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Anatomy of cerebral circulation

Blood is supplied to the brain by two major pairs of arteries: the internal carotid arteries (anterior circulation) and the vertebral arteries (posterior circulation). The carotid arteries branch to supply most of the frontal, parietal and temporal lobes, the basal ganglia and part of the diencephalon (thalamus and hypothalamus). The major branches of the carotid arteries are the middle cerebral and anterior cerebral arteries. The vertebral arteries join to form the basilar artery, which branches to supply the middle and lower part of the temporal lobes, the occipital lobes, cerebellum, brainstem and part of the diencephalon. The main branch of the basilar artery is the posterior cerebral artery. The anterior and posterior cerebral circulation is connected at the circle of Willis by the anterior and posterior communicating arteries (see Fig 57-1). Anomalies in this area are common and not all connecting vessels may be present.16

Regulation of cerebral blood flow

The brain requires a continuous supply of blood to provide the oxygen and glucose that neurons need to function. Blood flow must be maintained at 750–1000 mL per minute (55 mL per 100 g of brain tissue), or 20% of the cardiac output, for optimal brain functioning. If blood flow to the brain is totally interrupted (e.g. cardiac arrest), neurological metabolism is altered in 30 seconds, metabolism stops in 2 minutes and cellular death occurs in 5 minutes.16

The brain is normally well protected from changes in mean systemic arterial blood pressure over a range from 50 to 150 mmHg by a mechanism known as cerebral autoregulation. This involves changes in the diameter of cerebral blood vessels in response to changes in pressure so that the blood flow to the brain stays constant. Cerebral autoregulation may be impaired following cerebral ischaemia and cerebral blood flow then changes directly in response to changes in blood pressure. Carbon dioxide is a potent cerebral vasodilator and changes in arterial carbon dioxide levels have a dramatic effect on cerebral blood flow (increased carbon dioxide levels increase cerebral blood flow, and vice versa). Very low arterial oxygen levels (PaO2 <50 mmHg [<6.75 kPa]) or an increase in hydrogen ion concentration also increase cerebral blood flow.

Factors that affect blood flow to the brain include systemic blood pressure, cardiac output and blood viscosity. During normal activity, oxygen requirements vary considerably but changes in cardiac output, vasomotor tone and distribution of blood flow normally maintain adequate blood flow to the head. Cardiac output has to be reduced by one-third before cerebral blood flow is reduced. Changes in blood viscosity affect cerebral blood flow, with decreased viscosity increasing flow.

Collateral circulation may develop to compensate for a decrease in cerebral blood flow. Because of the connections between arteries at the circle of Willis, an area of the brain can potentially receive blood supply from another blood vessel if its original blood supply is cut off (e.g. because of thrombosis). Individual differences in collateral circulation partly determine the degree of brain damage and functional loss when a stroke occurs.6

Intracranial pressure (ICP) also influences cerebral blood flow (see Ch 56). Increased ICP causes brain compression and reduced cerebral blood flow.

Atherosclerosis

Atherosclerosis (hardening and thickening of arteries) is a major cause of stroke. It can lead to thrombus formation and contribute to emboli. (The role of atherosclerosis in thrombosis and emboli development is discussed in Ch 33.) Initially there is abnormal infiltration of lipids in the intimal layer of the artery. This fatty streak further develops into a plaque. Plaques often develop in areas of increased turbulence of the blood, such as at the bifurcation of an artery or a tortuous area (see Fig 57-2).

Figure 57-2 Common sites for the development of atherosclerosis in the extracranial and intracranial arteries. The main locations are just above the common carotid bifurcation (most common site) and the start of the branches from the aorta, innominate and subclavian arteries.

Calcified, brittle plaques may rupture or fissure. Platelet and fibrin stick to the roughened plaque surface. Plaques lead to narrowing or occlusion of the artery. In addition, parts of the plaque or thrombus can break off and travel to a narrower distal artery. Cerebral infarction occurs when an artery becomes blocked and blood supply to the brain beyond the blockage is cut off.

In response to ischaemia a series of metabolic events, termed the ischaemic cascade, occur, including inadequate adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production, loss of ion homeostasis, release of excitatory amino acids (e.g. glutamate), free radical formation and cell death.12 Around the core area of ischaemia is a border zone of reduced blood flow, termed the ischaemic penumbra, where ischaemia is potentially reversible. If adequate blood flow can be restored early (i.e. within 3 hours) and the ischaemic cascade can be interrupted, there may be less brain damage and less neurological function lost. Research is ongoing to identify thrombolytic therapies to re-establish blood flow and protect neurons from further ischaemic damage.

TRANSIENT ISCHAEMIC ATTACK

A transient ischaemic attack (TIA) is a temporary focal loss of neurological function caused by ischaemia of one of the vascular territories of the brain, lasting less than 24 hours and often less than 15 minutes. Most TIAs resolve within less than 3 hours. TIAs may be due to microemboli that temporarily block the blood flow. TIAs are a warning sign of progressive cerebrovascular disease. The signs and symptoms of a TIA depend on the blood vessel that is involved and the area of the brain that is ischaemic. If the carotid system is involved, patients may have a temporary loss of vision in one eye (amaurosis fugax), a transient hemiparesis, numbness or loss of sensation or a sudden inability to speak. Signs of a TIA involving the vertebrobasilar system may include tinnitus, vertigo, darkened or blurred vision, diplopia, ptosis, dysarthria, dysphagia, ataxia and unilateral or bilateral numbness or weakness.16

Evaluation must be done to confirm that the signs and symptoms of a TIA are not related to other brain lesions, such as a developing subdural haematoma or an increasing tumour mass. Computed tomography (CT) of the brain without contrast is the most important initial diagnostic study. Cardiac monitoring and tests may reveal an underlying cardiac condition that is responsible for clot formation. Drugs that prevent platelet aggregation, such as aspirin, clopidogrel, dipyridamole (in combination or without aspirin), ticlopidine and anticoagulant drugs (e.g. oral warfarin), may be prescribed for long-term therapy after a TIA.

TYPES OF STROKE

Strokes are classified as ischaemic or haemorrhagic based on the underlying pathophysiological findings (see Fig 57-3 and Table 57-1).

TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

Source: Adapted from Clinical guidelines for stroke management. Melbourne: National Stroke foundation; 2010. New Zealand guidelines for stroke management. Wellington: Stroke foundation of new Zealand; 2010.

Ischaemic stroke

Ischaemic stroke results from inadequate blood flow to the brain from partial or complete occlusion of an artery and accounts for approximately 85% of all strokes.6 Ischaemic strokes can be further divided into thrombotic and embolic strokes.

Thrombotic stroke

Thrombosis occurs in relation to injury to a blood vessel wall and formation of a blood clot. The lumen of the blood vessel becomes narrowed and, if it becomes occluded, infarction occurs. Thrombosis develops readily where atherosclerotic plaques have already narrowed blood vessels. Thrombotic stroke, which is the result of thrombosis or narrowing of the blood vessel, accounts for 20% of all strokes.4,7,12 Approximately 40% of thrombotic strokes are preceded by a TIA.12

The extent of the stroke depends on the rapidity of onset, the size of the lesion and the presence of collateral circulation. Most patients with ischaemic stroke do not have a decreased level of consciousness in the first 24 hours, unless it is due to a brainstem stroke or other conditions such as seizures, increased ICP or haemorrhage. Ischaemic stroke symptoms may progress in the first 72 hours as infarction and cerebral oedema increase.

A lacunar stroke refers to a stroke from occlusion of a small penetrating artery with development of a cavity in the place of the infarcted brain tissue. This most commonly occurs in the basal ganglia, thalamus, internal capsule or pons. Although a large percentage of lacunar strokes are asymptomatic, when present, symptoms can cause considerable deficits. These include pure motor hemiplegia, pure sensory stroke (contralateral loss of all sensory modalities), contralateral leg and face weakness with arm and leg ataxia, and isolated motor or sensory stroke. Multiple small vessel infarcts may also result in a decrease in cognitive function (i.e. multi-infarct dementia; see Ch 59).1,2,12

Embolic stroke

Embolic stroke occurs when an embolus lodges in and occludes a cerebral artery, resulting in infarction and oedema of the area supplied by the involved vessel. Embolism accounts for about 20% of all strokes.6,17 The majority of emboli originate in the endocardial (inside) layer of the heart, with plaque breaking off from the endocardium and entering the circulation. The embolus travels upwards to the cerebral circulation and lodges where a vessel narrows or bifurcates. Heart conditions associated with emboli include AF, myocardial infarction, infective endocarditis, rheumatic heart disease, valvular prostheses and atrial septal defects. Less common causes of emboli include air and fat from long bone (femur) fractures.

Embolic strokes can affect any age group. Rheumatic heart disease is one cause of embolic stroke in young to middle-aged adults (this is particularly relevant in Australia, where Indigenous Australians living in remote communities have the highest incidence of rheumatic heart disease in the world; see Ch 3618). An embolus arising from an atherosclerotic plaque is more common in older adults. Warning signs are less common with embolic stroke than with thrombotic stroke. The onset of an embolic stroke is usually sudden and may or may not be related to activity. The patient usually remains conscious but may have a headache. Prognosis is related to the amount of brain tissue deprived of its blood supply. The effects of the emboli are initially characterised by severe neurological deficits, which can be temporary if the clot breaks up and allows blood to flow. Smaller emboli then continue to obstruct smaller vessels, which in turn involve smaller portions of the brain with fewer deficits noted. The embolic stroke often occurs rapidly and the body does not have time to accommodate by developing collateral circulation. Recurrence of embolic stroke is common unless the underlying cause is treated aggressively.4,7

Haemorrhagic stroke

Haemorrhagic stroke accounts for approximately 13% of all strokes and results from bleeding into the brain tissue itself (intracerebral or intraparenchymal haemorrhage) or into the subarachnoid space or ventricles (subarachnoid haemorrhage or intraventricular haemorrhage).1,2,12

Intracerebral haemorrhage

Intracerebral haemorrhage is bleeding within the brain caused by a rupture of a vessel (see Fig 57-4). Hypertension is the most important cause of intracerebral haemorrhage. Other causes include cerebral amyloid angiopathy, vascular malformations, coagulation disorders, anticoagulant and thrombolytic drugs, trauma, brain tumours and ruptured aneurysms. Haemorrhage commonly occurs during periods of activity. There is most often a sudden onset of symptoms, with progression over minutes to hours because of ongoing bleeding. Symptoms include neurological deficits, headache, nausea, vomiting, decreased level of consciousness (in about 50%) and hypertension. The extent of the symptoms varies depending on the amount and duration of the bleeding. A blood clot within the closed skull can result in a mass that causes pressure on brain tissue, displaces brain tissue and decreases cerebral blood flow, leading to ischaemia and infarction.16

Figure 57-4 Massive hypertensive haemorrhage rupturing into a lateral ventricle.

Source: Kumar V, Abbas AK. Robbins & Cotran pathologic basis of disease. 7th edn. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2005.

About half of intracerebral haemorrhages occur in the putamen and internal capsule, central white matter, thalamus, cerebral hemispheres and pons. Initially, patients experience a severe headache with nausea and vomiting. Clinical manifestations of putaminal and internal capsule bleeding include weakness of one side (including the face, arm and leg), slurred speech and deviation of the eyes. Progression of symptoms related to a severe haemorrhage includes hemiplegia, fixed and dilated pupils, abnormal body posturing and coma.12,16,17 Thalamic haemorrhage results in hemiplegia with more sensory than motor loss. Bleeding into the subthalamic areas of the brain leads to problems with vision and eye movement. Cerebellar haemorrhages are characterised by severe headache, vomiting, loss of ability to walk, dysphagia, dysarthria and eye movement disturbances. Haemorrhage in the pons is the most serious because basic life functions (e.g. respiration) are rapidly affected. Haemorrhage in the pons can be characterised by hemiplegia leading to complete paralysis, coma, abnormal body posturing, fixed pupils, hyperthermia and death. The prognosis of patients with intracerebral haemorrhage is poor: more than 50% die soon after the haemorrhage occurs and only about 20% are functionally independent at 6 months.4,7,12

Subarachnoid haemorrhage

Subarachnoid haemorrhage occurs when there is intracranial bleeding into the cerebrospinal fluid-filled space between the arachnoid and pia mater membranes on the surface of the brain. Subarachnoid haemorrhage is commonly caused by rupture of a cerebral aneurysm (congenital or acquired weakness and ballooning of vessels). Aneurysms may be saccular or berry aneurysms, ranging from a few millimetres to 20–30 mm in size, or fusiform atherosclerotic aneurysms. The majority of aneurysms are in the circle of Willis.17 Other causes of subarachnoid haemorrhage include arteriovenous malformations (AVMs), trauma and illicit drug (cocaine) abuse. The incidence increases with age and is higher in women than in men.

The patient may have warning symptoms if the ballooning artery applies pressure to brain tissue or minor warning symptoms from leaking of an aneurysm before major rupture. The characteristic presentation of a ruptured aneurysm is the sudden onset of a severe headache that is different from a previous headache and typically the ‘worst headache of one’s life’. Loss of consciousness may or may not occur and the patient’s level of consciousness may range from alert to comatose, depending on the severity of the bleed. Other symptoms include focal neurological deficits (including cranial nerve deficits), nausea, vomiting, seizures and stiff neck. Despite improvements in surgical techniques and management, many patients with subarachnoid haemorrhage die and many are left with significant morbidity, including cognitive difficulties.1,4,12

Complications of aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage include rebleeding before surgery or other therapy is initiated and cerebral vasospasm (narrowing of the large blood vessels at the base of the brain), which can result in cerebral infarction. Cerebral vasospasm is most likely due to an interaction between the metabolites of blood and the vascular smooth muscle. During the lysis of subarachnoid blood clots, metabolites are released. These metabolites can cause endothelial damage and vasoconstriction. In addition, release of endothelin (a potent vasoconstrictor) may play a major role in the induction of cerebral vasospasm after subarachnoid haemorrhage.

The most frequent surgical procedure to prevent rebleeding is clipping of the aneurysm (see Fig 57-8). Endovascular techniques may also be used. In the procedure known as coiling, a metal coil can be inserted into the lumen of the aneurysm via interventional neuroradiology (see Fig 57-9). This results in thrombus formation around the coil, resulting in blockage of the aneurysmal sac. Interventions to treat cerebral vasospasm either before or following aneurysm clipping or coiling include administration of the calcium channel-blocker nimodipine. Following aneurysmal occlusion, hyperdynamic therapy, including haemodilution, induced hypertension using vasoconstricting agents (e.g. phenylephrine or dopamine) and hypervolaemia, may be instituted in an effort to increase the mean arterial pressure and increase cerebral perfusion. Volume expansion is achieved via crystalloid or colloid solution.

Figure 57-9 Guglielmi detachable coil. A, A coil is used to occlude an aneurysm. Coils are made of soft, spring-like platinum. The softness of the platinum allows the coil to assume the shape of irregularly shaped aneurysms while posing little threat of rupture of the aneurysm. B, A catheter is inserted through an introducer (small tube) in an artery in the leg. The catheter is threaded up to the cerebral blood vessels. C, Platinum coils attached to a thin wire are inserted into the catheter and then placed in the aneurysm until the aneurysm is filled with coils. Packing the aneurysm with coils prevents the blood from circulating through the aneurysm, reducing the risk of rupture.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

A stroke can have an effect on many body functions, including motor activity, elimination, intellectual function, spatial–perceptual alterations, personality, affect, sensation and communication. The functions affected are directly related to the artery involved and the area of the brain it supplies (see Box 57-2). Manifestations related to right- and left-brain damage differ somewhat and are shown in Figure 57-5.

BOX 57-2 Clinical manifestations: specific cerebral artery involvement

Anterior cerebral artery involvement

Occlusion of stem*

Occlusion distal to anterior communicating artery

Contralateral sensory and motor deficits of foot and leg, greatest distally

Contralateral weakness of proximal upper extremity

Urinary incontinence (possibly unrecognised by patient)

Sensory loss (discrimination, proprioception)

Contralateral grasp and sucking reflexes may be present

Personality change: flat affect, loss of spontaneity, loss of interest in surroundings, distractibility, slowness in responding

Posterior cerebral artery and vertebrobasilar involvement†

*There is usually no problem if the stem is occluded near the anterior communicating artery because perfusion from the opposite side is maintained.

†The site of occlusion, the origin of the basilar arteries and the arrangement of the circle of Willis are involved in the type of deficit seen. This can occur from a thrombus or embolus.

The term brain attack is increasingly being used to describe stroke and communicate the urgency of recognising stroke symptoms and treating their onset as a medical emergency, similar to heart attack. The National Stroke Foundation in Australia and the Stroke Foundation in New Zealand promote use of the acronym FAST to emphasise the need for people to respond quickly if they experience any of the following symptoms:

If a person has one or more of these deficits in the face, arm or speech, they need to contact the emergency services or get to hospital as soon as possible. The time frame between onset of symptoms and hospitalisation can be critical to the outcome: immediate medical attention is crucial if disability is to be minimised and the risk of death reduced.

Motor function

Motor deficits are the most obvious effect of stroke. Motor deficits include impairment of: (1) mobility; (2) respiratory function; (3) swallowing and speech; (4) gag reflex; and (5) self-care abilities. Symptoms are caused by the destruction of motor neurons in the pyramidal pathway (nerve fibres from the brain and passing through the spinal cord to the motor cells). The characteristic motor deficits include loss of skilled voluntary movement (akinesia), impairment of integration of movements, alterations in muscle tone and alterations in reflexes. The initial hyporeflexia (depressed reflexes) progresses to hyperreflexia (hyperactive reflexes) for most patients.6

Motor deficits as a result of stroke follow certain specific patterns. Because the pyramidal pathway crosses at the level of the medulla, a lesion on one side of the brain affects motor function on the opposite side of the brain (contralateral). The arm and leg of the affected side may be weakened or paralysed to different degrees depending on which part of, and to what extent, the cerebral circulation was compromised. A stroke affecting the middle cerebral artery leads to a greater weakness in the upper extremity than the lower extremity. The affected shoulder tends to rotate internally and the hip rotates externally. The affected foot is plantar flexed and inverted. An initial period of flaccidity may last from days to several weeks and is related to nerve damage. Spasticity of the muscles follows the flaccid stage and is related to interruption of upper motor neuron influence.

Communication

The left hemisphere is dominant for language skills in right-handed persons and in most left-handed persons. Language disorders involve expression and comprehension of written and spoken words. The patient may experience aphasia (total loss of comprehension and use of language) when a stroke damages the dominant hemisphere of the brain. Dysphasia refers to difficulty related to the comprehension or use of language and is due to partial disruption or loss. Patterns of dysphasia may differ as the stroke affects different portions of the brain. Dysphasias can be classified as non-fluent (minimal speech activity with slow speech that requires obvious effort) or fluent (speech is present but contains little meaningful communication). Most dysphasias are mixed with impairment in both expression and understanding. A massive stroke may result in global aphasia, in which all communication and receptive function is lost.4,7 Strokes affecting Wernicke’s area of the brain exhibit symptoms of receptive aphasia, when neither the sounds of speech nor its meaning can be understood. This results in impairment of the patient’s comprehension of both spoken and written language. Strokes affecting Broca’s area of the brain cause expressive aphasia (difficulty in speaking and writing).

Many stroke patients also experience dysarthria, a disturbance in the muscular control of speech. Impairments may involve pronunciation, articulation and phonation. Dysarthria does not affect the meaning of communication or the comprehension of language but it does affect the mechanics of speech. Some patients experience a combination of aphasia and dysarthria.

Affect

Patients who have had a stroke may have difficulty controlling their emotions. Emotional responses may be exaggerated or unpredictable. Depression and feelings associated with changes in body image and loss of function can make this worse. Patients may also be frustrated by mobility and communication problems, and then display an emotional reaction (e.g. crying or anger) that was uncharacteristic before the stroke.

Intellectual function

Both memory and judgement may be impaired as a result of stroke. These impairments can occur with strokes affecting either side of the brain. A left-brain stroke is more likely to result in memory problems related to language. Patients with a left-brain stroke often are very cautious in making judgements. The patient with a right-brain stroke tends to be impulsive and to move quickly. An example of behaviour with right-brain stroke is the patient who tries to rise quickly from the wheelchair without locking the wheels or raising the footrests. The patient with a left-brain stroke would move slowly and cautiously from the wheelchair. Patients with either type of stroke may have difficulty generalising, which interferes with their ability to learn.

Spatial–perceptual alterations

A stroke on the right side of the brain is more likely to cause problems in spatial–perceptual orientation, although this can also occur with left-brain stroke. Spatial–perceptual problems may be divided into four categories. The first is related to the patient’s incorrect perception of the self and illness. This deficit follows damage to the parietal lobe. Patients may deny their illnesses or their own body parts. The second category concerns the patient’s erroneous perception of the self in space. The patient may neglect all input from the affected side. This may be worsened by homonymous hemianopsia, in which blindness occurs in the same half of the visual fields of both eyes. The patient also has difficulty with spatial orientation, such as judging distances. The third spatial–perceptual deficit is agnosia, the inability to recognise an object by sight, touch or hearing. The fourth deficit is apraxia, the inability to carry out learned sequential movements on command. Patients may or may not be aware of their spatial–perceptual alterations.

Elimination

Fortunately, most problems with urinary and bowel elimination occur initially and are temporary. When a stroke affects one hemisphere of the brain, the prognosis for normal bladder function is excellent. At least partial sensation for bladder filling remains and voluntary urination is present. Initially, the patient may experience frequency, urgency and incontinence. Although motor control of the bowel is usually not a problem, patients are frequently constipated. Constipation is associated with immobility, weak abdominal muscles, dehydration and diminished response to the defecation reflex. Urinary and bowel elimination problems may also be related to inability to express needs and to manage clothing.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

When symptoms of a stroke occur, diagnostic studies are done to: (1) confirm that it is a stroke and not another brain lesion, such as a subdural haematoma; and (2) identify the likely cause of the stroke (see Box 57-3).

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Additional studies

CT, computed tomography; CTA, computed tomography angiography; MRA, magnetic resonance angiography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; MRS, magnetic resonance spectroscopy; PET, positron emission tomography; SPECT, single photon emission computed tomography.

*A lumbar puncture to obtain cerebrospinal fluid is avoided if increased intracranial pressure is suspected.

Tests also guide decisions about therapy to prevent a secondary stroke. A CT scan is the primary diagnostic test used after a stroke. CT can indicate the size and location of the lesion and differentiate between ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke. CT angiography (CTA) provides visualisation of vasculature and can be performed at the same time as the CT scan. CTA allows detection of intracranial or extracranial occlusive disease. Serial CT scans may be used to assess the effectiveness of treatment and to evaluate recovery.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is used to determine the extent of brain injury. Compared to CT, MRI has greater specificity. Diffusion-weighted MRI is a more sensitive MRI technique that better delineates ischaemic brain injury early after a stroke when CT and standard MRI may appear normal. Use of MRI may be restricted in patients with claustrophobia or in the presence of devices such as pacemakers that would be affected by the magnetic field. Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) is a non-invasive method of assessing vascular occlusive disease in the head or neck, similar to CTA.

Other tests used to diagnose stroke and assess the extent of tissue damage include positron emission tomography (PET), magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS), xenon CT, single photon emission CT (SPECT) and cerebral angiography. PET shows the metabolic activity of the brain and provides a depiction of the extent of tissue damage after a stroke. Less active or diseased tissue appears darker than healthy, active cells. MRS detects biochemical changes that may be present before physical changes are apparent. Its value in the clinical evaluation of stroke remains to be determined. Angiography is the gold standard for imaging the carotid arteries. It can identify cervical and cerebrovascular occlusion, atherosclerotic plaques and malformation of vessels. Intraarterial digital subtraction angiography (DSA) reduces the dose of contrast material, uses smaller catheters and shortens the length of the procedure compared to conventional angiography. DSA involves the injection of a contrast agent to visualise blood vessels in the neck and the large vessels of the circle of Willis. It is considered safer than cerebral angiography because less vascular manipulation is required. Risks of angiography include dislodging an embolus, vasospasm, inducing further haemorrhage and allergic reaction to the contrast medium.

Transcranial Doppler (TCD) ultrasonography is a non-invasive study that measures the velocity of blood flow in the major cerebral arteries. TCD ultrasonography has been shown to be effective in detecting microemboli and vasospasm. Other neurodiagnostic tests, such as skull X-rays, brain scan, lumbar puncture and electroencephalogram (EEG), are currently used much less in the diagnosis of stroke. A skull X-ray result is usually normal after a stroke but there may be a pineal shift with a massive infarction.

A lumbar puncture may be done to look for evidence of red blood cells in the cerebrospinal fluid if a subarachnoid haemorrhage is suspected but the CT does not show haemorrhage. A lumbar puncture is avoided if there are signs of increased ICP because of the danger of herniation of the brain downwards, leading to pressure on cardiac and respiratory centres in the brainstem and potentially death. An EEG may show low-voltage, slow-wave activity suggestive of ischaemic infarction. If the stroke is due to a haemorrhage, the EEG may show high-voltage slow waves. If the suspected cause of the stroke includes emboli from the heart, diagnostic cardiac tests should be done (see Box 57-3).

Blood tests are also done to help identify conditions contributing to stroke and to guide treatment (see Box 57-3).

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Prevention

Primary prevention is a priority for decreasing morbidity and mortality from stroke (see Box 57-4).4,7 The goals of stroke prevention include health management for the well individual and education and management of modifiable risk factors to prevent a primary or secondary stroke. Health management focuses on: (1) healthy diet; (2) weight control; (3) regular exercise; (4) no smoking; (5) limiting alcohol consumption; and (6) routine health assessments. Patients with known risk factors, such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, obesity, high serum lipid levels or cardiac dysfunction, require close management.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Drug therapy

Measures to prevent the development of a thrombus or an embolus are used in patients at risk of stroke. Antiplatelet drugs are usually the chosen treatment to prevent further stroke in patients who have had a TIA related to atherosclerosis.13 Aspirin is the most frequently used antiplatelet agent, commonly at a dose of 100 mg per day. Other drugs include clopidogrel, dipyridamole, ticlopidine, and combined dipyridamole and aspirin. Oral anticoagulation using warfarin is the treatment of choice for individuals with AF who have had a TIA.4,7,13

Surgical therapy

Surgical interventions for the patient with TIAs from carotid disease include carotid endarterectomy, transluminal angioplasty, stenting and extracranial–intracranial (EC–IC) bypass. In a carotid endarterectomy, the atheromatous lesion is removed from the carotid artery to improve blood flow (see Fig 57-6).13 Transluminal angioplasty is the insertion of a balloon to open a stenosed artery and improve blood flow. Stenting involves intravascular placement of a stent in an attempt to maintain patency of the artery (see Fig 57-7). These procedures are still being evaluated as options to carotid endarterectomy.

Figure 57-6 Carotid endarterectomy is performed to prevent impending cerebral infarction. A, A tube is inserted above and below the blockage to reroute the blood flow. B, Atherosclerotic plaque in the common carotid artery is removed. C, Once the artery is stitched closed, the tube can be removed. A surgeon may also perform the technique without rerouting the blood flow.

Figure 57-7 Brain stent used to treat blockages in cerebral blood flow. A, A balloon catheter is used to implant the stent into an artery of the brain. B, The balloon catheter is moved to the blocked area of the artery and then inflated. The stent expands due to the inflation of the balloon. C, The balloon is deflated and withdrawn, leaving the stent permanently in place, holding the artery open and improving the flow of blood.

Source: courtesy of Center for Endovascular Surgery. Available at: http://neuro.wehealny.org/endo/proc_stents-angioplasty.asp

EC–IC bypass involves anastomosing (surgically connecting) a branch of an extracranial artery to an intracranial artery (most commonly, superficial temporal to middle cerebral artery) beyond an area of obstruction with the goal of increasing cerebral perfusion. This procedure is generally reserved for those patients who do not benefit from other forms of therapy.13,15 Further study is needed to determine the benefits of this therapy over medical therapy.

Acute care

The goals for multidisciplinary care during the acute phase are preserving life, preventing further brain damage and reducing disability. In many acute care settings, care of the patient following a stroke will be undertaken in a specialised stroke unit. Studies have found that stroke unit care reduces the risk of death due to stroke by 14% and reduces disability by 18%.19 These results are attributable to a coordinated multidisciplinary approach, specialist staff with a focus on patient and family education, and access to early rehabilitation. Treatment differs according to the type of stroke and changes as the patient progresses from the acute to the rehabilitation phase.

Table 57-2 outlines the emergency management of the patient with a stroke. Acute care begins with managing the ABCs. Patients may have difficulty keeping an open and clear airway because of a decreased level of consciousness or decreased or absent gag and swallowing reflexes. Maintaining adequate oxygenation is important. Both hypoxia and hypercarbia are to be avoided because they can contribute to secondary neuronal injury. Oxygen administration, artificial airway insertion, intubation and mechanical ventilation may be required. Baseline neurological assessment is carried out and patients are monitored closely for signs of increasing neurological deficit. About 25% of patients will worsen in the first 24–48 hours.6

Elevated blood pressure is common immediately after a stroke, often lasting 48–72 hours, and may be a protective response to maintain cerebral perfusion. Immediately after ischaemic stroke, use of drugs to lower blood pressure is recommended only if blood pressure is markedly increased (mean arterial pressure >130 mmHg or systolic pressure >220 mmHg).20 Oral antihypertensive drugs are generally preferred. Although low blood pressure immediately following stroke is uncommon, hypotension and hypovolaemia should be corrected if present. Hypervolaemic haemodilution using crystalloids and colloids and drug-induced hypertension may be used in patients with ischaemia caused by vasospasm following subarachnoid haemorrhage once the aneurysm has been successfully clipped or coiled (coils placed in the aneurysm sac).

Fluid and electrolyte balance must be controlled carefully.20 The goal generally is to keep the patient adequately hydrated to promote perfusion and decrease further brain injury. Overhydration may compromise perfusion by increasing cerebral oedema. Adequate fluid intake during acute care via oral, intravenous (IV) or tube feedings should be 1500–2000 mL per day. Urine output is monitored. If secretion of antidiuretic hormone (ADH) increases in response to the stroke, urine output decreases and fluid is retained. Low serum sodium levels (hyponatraemia) may occur. IV solutions with glucose and water are avoided because they are hypotonic and may further increase cerebral oedema and ICP. In addition, hyperglycaemia may be associated with further brain damage and should be treated. In general, decisions about fluid and electrolyte replacement therapy are based on the extent of intracranial oedema, symptoms of increased ICP, central venous pressure levels, laboratory values for electrolytes, and intake and output.

Increased ICP is more likely to occur with haemorrhagic strokes but can occur with ischaemic strokes. Increased ICP from cerebral oedema usually peaks in 72 hours and may cause brain herniation. Management of increased ICP includes practices that improve venous drainage, such as elevating the head of the bed, maintaining the head and neck in alignment, and avoiding hip flexion. Hyperthermia, which is seen commonly following stroke and may be associated with poorer outcome, should be avoided as increased temperature contributes to increased cerebral metabolism. Other measures to manage increased ICP include pain management, avoidance of hypervolaemia and management of constipation. Cerebrospinal fluid drainage may be used in some patients to reduce ICP. Diuretic drugs, such as mannitol and frusemide, may be used to decrease cerebral oedema. As a last resort in the management of ICP, a bone flap may be removed to allow for cerebral oedema without increases in ICP. The bone flap is implanted in the patient’s abdominal fat or frozen and replaced later.13

Drug therapy

Recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (alteplase) is used to re-establish blood flow through a blocked artery to prevent cell death in patients with the acute onset of ischaemic stroke symptoms.21 Thrombolytic drugs, such as alteplase, produce localised fibrinolysis by binding to the fibrin in the thrombi. The lytic action of alteplase occurs as the plasminogen is converted to plasmin (fibrinolysin); the enzymatic action digests fibrin and fibrinogen and thus lyses the clot. Because it is clot-specific in its activation of the fibrinolytic system, alteplase is less likely to cause haemorrhage than streptokinase or urokinase (see Evidence-based practice box and Ch 33).

Stroke and thrombolytic therapy

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

Clinical question

Is thrombolytic therapy (I) safe and effective (O) in patients with acute ischaemic stroke (P)?

Background

Recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA) is given for thrombolytic therapy in ischaemic stroke if administered within 3 hours of stroke onset in selected patients.

Objectives

The objectives of this study were to assess the safety and efficacy of thrombolytic agents used in acute treatment of ischaemic stroke, factors that might influence risk or benefit, and estimate whether current data can identify the latest time window for treatment.

Critical appraisal and synthesis of evidence

• Overall, among the selected populations of patients included in the trials to date (99% of whom were aged <80 years), rtPA significantly reduced the proportion of patients with poor outcomes after stroke (and conversely increased the proportion of patients with good outcomes).

• This overall benefit was apparent despite a non-significant increase in deaths, mostly attributable to ICH.

• There were insufficient data to determine the risk–benefit ratio for different categories of patients.

Implications for nursing practice

• Use of rtPA within existing guidelines is supported by the available evidence, but data are insufficient to determine risks and benefits in clinically important subgroups of patients, especially those aged >80 years, and by vascular risk factors and medical history, brain scan appearances, stroke subtype or the latest time for benefit.

P, patient population of interest; I, intervention or area of interest; O, outcome(s) of interest.

Ideally, alteplase must be administered within 3 hours of the onset of clinical signs of ischaemic stroke. Therefore, the single most important factor is timing. Patients must be screened carefully before alteplase can be given. Screening includes a CT or MRI scan to rule out haemorrhagic stroke, blood tests for coagulation disorders and screening for recent history of gastrointestinal bleeding, stroke or head trauma within the past 3 months, or major surgery within 14 days. Thrombolytic therapy given within 3 hours of the onset of symptoms in ischaemic stroke reduces disability but at the expense of an increase in deaths within the first 7–10 days and an increase in intracranial haemorrhage.21 During infusion of the drug, the patient’s vital signs and neurological status are monitored closely to assess for improvement or potential deterioration related to intracerebral haemorrhage. Control of blood pressure is critical during treatment and for the following 24 hours. No anticoagulant or anti-platelet drugs are given for 24 hours after alteplase treatment.

Patients with a stroke caused by thrombi and emboli may also be treated with platelet inhibitors and anticoagulants (after the first 24 hours if treated with alteplase) to prevent further clot formation. Common anticoagulants include heparin and warfarin. Platelet inhibitors include aspirin, clopidogrel, ticlopidine and dipyridamole. IV heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin may be given in the situation of rapidly evolving strokes or stroke caused by emboli travelling from the heart. IV heparin is administered via continuous infusion and activated partial thromboplastin time is closely monitored.

Typically, heparin is replaced by oral warfarin for long-term administration. Warfarin dosage is regulated according to the international normalised ratio (INR), a standardised measure of prothrombin time that adjusts for assay variations. The therapeutic range for the INR is 2–3 times normal. Patients must be monitored closely for haemorrhage at other body sites while using anticoagulants and platelet inhibitors. A patient teaching guide for patients taking long-term warfarin can be found in Chapter 37. Subcutaneous heparin may be administered for deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis.

Anticoagulants and platelet inhibitors are contraindicated for patients with haemorrhagic strokes. The pathogenesis of vasospasm is not yet understood; however, a calcium channel blocker such as nimodipine is given to patients with subarachnoid haemorrhage to decrease the effects of vasospasm and minimise cerebral damage through delayed ischaemia.21

Aspirin is also used to prevent platelet aggregation at the site of atherosclerotic plaque. Complications of aspirin include gastrointestinal bleeding with higher doses. Aspirin is administered cautiously if the patient has a history of peptic ulcer disease or is taking other anticoagulants.

The nurse must closely monitor the patient’s temperature. A temperature elevation of even 1°C can increase brain metabolism by 10% and contribute to further brain damage.22 Drug therapies to treat hyperthermia include aspirin or paracetamol. Cooling blankets may be used to lower temperature cautiously.

Stroke is the most common cause of acquired epilepsy, accounting for 11% of all cases of epilepsy.23 The pathophysiology of early and late-onset post-stroke seizures is believed to differ. While some studies have linked post-stroke seizures to worse outcomes, there is currently no clear evidence to support routine prescription of anticonvulsant drugs for primary and secondary prevention of seizures.23

Surgical therapy

Surgical interventions for stroke include immediate evacuation of aneurysm-induced haematomas or cerebellar haematomas larger than 3 cm. Subarachnoid haemorrhage is usually caused by a ruptured aneurysm. Approximately 20% of patients will have multiple aneurysms.6,13 Treatment of an aneurysm involves clipping, wrapping or coiling the aneurysm to prevent rebleeding (see Fig 57-8). Treatment of AVM is surgical resection. This may be preceded by interventional neuroradiology to embolise the blood vessels that supply the AVM. In the procedure known as coiling, a metal coil is inserted into the lumen of the aneurysm using interventional neuroradiology (see Fig 57-9). Eventually, a thrombus forms within the aneurysm and the aneurysm becomes sealed off from the parent vessel by the formation of an endothelialised layer of connective tissue.

Subarachnoid and intracerebral haemorrhage can involve bleeding into the ventricles of the brain. This situation produces hydrocephalus, which further damages brain tissue from increased ICP. Insertion of a ventriculostomy for cerebrospinal fluid drainage can result in dramatic improvement in these situations.

Rehabilitation care

After the stroke has stabilised for 12–24 hours, multidisciplinary care shifts from preserving life to lessening disability and attaining optimal function. The patient may be evaluated by a specialist team. It is important to remember that some aspects of rehabilitation actually begin in the acute care phase as soon as the patient is stabilised. Depending on the patient’s status, other medical conditions, rehabilitation potential and available resources, the patient may be transferred to a rehabilitation unit. Other options for rehabilitation include outpatient therapy and home-based rehabilitation.4,7 Research has demonstrated that even though permanent neuron damage has occurred, the use of repetitive actions in rehabilitation can result in the reorganisation of the neurons. This reorganisation demonstrates what is called neuroplasticity (see Ch 60 for further discussion on neuroplasticity). This is not quite as simple as it sounds; recovery is based on many factors and the effects of repetitive action in rehabilitation therapy are still being evaluated.24

As part of the long-term multidisciplinary care after a stroke, various members of the healthcare team will be involved in the effort to promote optimal function for the patient and family.4,7 The composition of the team depends on the patient’s and family’s needs and on rehabilitation resources.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: STROKE

NURSING MANAGEMENT: STROKE

Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment

Subjective and objective data that should be obtained from the patient who has had a stroke are presented in Table 57-3. Primary assessment is focused on cardiac and respiratory status and neurological assessment. If the patient is stable, the nursing history is obtained as follows: (1) description of the current illness with attention to initial symptoms, including onset and duration, nature (intermittent or continuous) and changes; (2) history of similar symptoms previously experienced; (3) current medications; (4) history of risk factors and other illnesses such as hypertension; and (5) family history of stroke or cardiovascular diseases. This information is gained through an interview with the patient, family members, significant others or carer.

CT, computed tomography; CTA, computed tomography angiography; MRA, magnetic resonance angiography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; Tia, transient ischaemic attack.

Secondary assessment should include a comprehensive neurological examination of the patient. This includes: (1) level of consciousness (Glasgow Coma Scale); (2) cognition; (3) motor abilities; (4) cranial nerve function; (5) sensation; (6) proprioception; (7) cerebellar function; and (8) deep tendon reflexes. Clear documentation of initial and ongoing neurological examinations is essential to note changes in patient status.

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses for the patient with a stroke may include, but are not limited to, those presented in NCP 57-1.

Planning

Planning

The patient, family and nurse establish the goals of nursing care in a cooperative manner. Typical goals are that the patient will: (1) maintain a stable or improved level of consciousness; (2) attain maximum physical functioning; (3) attain maximum self-care abilities and skills; (4) maintain stable body functions (e.g. bladder control); (5) maximise communication abilities; (6) maintain adequate nutrition; (7) avoid complications of stroke; and (8) maintain effective personal and family coping.

Nursing implementation

Nursing implementation

Health promotion

Health promotion

To reduce the incidence of stroke, the nurse should focus any teaching efforts towards stroke prevention,25 particularly for patients with known risk factors (see Box 57-1). In any healthcare setting and for the population as a whole, nurses can play a major role in the promotion of a healthy lifestyle.6

Another very important aspect of health promotion is teaching patients and families about the early symptoms associated with stroke or TIA and when they should seek healthcare for the symptoms (see Box 57-5).

BOX 57-5 Warning signs of stroke

PATIENT & FAMILY TEACHING GUIDE

If someone is showing one or more of these signs, do not ignore them. Call 000 in Australia or 111 in New Zealand and get medical help immediately.

• Sudden weakness, paralysis or numbness of the face, arm or leg, especially on one side of the body

• Sudden dimness or loss of vision in one or both eyes

• Sudden loss of speech, confusion or difficulty speaking or understanding speech

• Unexplained sudden dizziness, unsteadiness, loss of balance or coordination

Acute intervention

Acute intervention

Stroke affects every part of the patient, so nursing care must be directed at both the emotional and the physical needs of the patient.

Respiratory system

Respiratory system

During the acute phase following a stroke, management of the respiratory system is a nursing priority. Stroke survivors are particularly vulnerable to respiratory problems.26 Advancing age and immobility increase the risk of atelectasis and pneumonia. Risk of aspiration pneumonia may be high because of impaired consciousness or dysphagia. Airway obstruction can occur because of problems with chewing and swallowing, food pocketing (food remaining in the buccal cavity of the mouth) and the tongue falling back. Some patients, especially those with a stroke in the brainstem or haemorrhagic stroke, may require endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation initially and/or with increasing cerebral oedema and/or ICP. Enteral tube feedings also place the patient at risk of aspiration pneumonia.27

Nursing interventions to support adequate respiratory function are individualised to meet the needs of the patient.6 An oropharyngeal airway may be used in unconscious patients to prevent the tongue from falling back and obstructing the airway and to provide access for suctioning. Alternatively, a nasopharyngeal airway may be used to provide airway protection and access. When an artificial airway is required for a prolonged time, a tracheostomy may be performed. Nursing interventions include frequent assessment of airway patency and function, oxygenation, suctioning, patient mobility, positioning of the patient to prevent aspiration and encouraging deep breathing. Patients who have an unclipped or uncoiled aneurysm may experience rebleeding and the possibility of further ICP increases with coughing exercises. Interventions related to maintenance of airway function are described in NCP 57-1.

Neurological system

Neurological system

Early on in care the patient’s neurological status must be monitored closely to detect changes suggestive of extension of the stroke, increased ICP, vasospasm or recovery from stroke symptoms. Neurological assessment includes the Glasgow Coma Scale, mental status, pupillary responses, and extremity movement and strength. (The Glasgow Coma Scale is outlined in Table 56-2.) Vital signs are also closely monitored and documented. A decreasing level of consciousness may indicate increasing ICP. ICP and cerebral perfusion pressure may be monitored as well if the patient is in a critical care environment. Data from the nursing assessment are recorded on flow sheets to communicate evaluation of neurological status to the interdisciplinary team.

Cardiovascular system

Cardiovascular system

Nursing goals for the cardiovascular system are aimed at maintaining homeostasis. Many patients with stroke have decreased cardiac reserves from a secondary diagnosis of cardiac disease. Cardiac efficiency may be further compromised by fluid retention, overhydration, dehydration and blood pressure variations. Fluids are retained if there is increased production of ADH and aldosterone secondary to stress. Fluid retention plus overhydration can result in fluid overload. It can also increase cerebral oedema and ICP. At the same time, dehydration can add to the morbidity and mortality associated with stroke, especially in the patient with vasospasm. IV therapy should be carefully regulated. The nurse should closely monitor intake and output. Central venous pressure, pulmonary artery pressure or haemodynamic monitoring may be used as indicators of fluid balance or cardiac function in the critical care unit. (See Ch 66.)

Nursing interventions include: (1) monitoring vital signs frequently; (2) continuously monitoring cardiac rhythms; (3) calculating intake and output, and noting imbalances; (4) regulating IV infusions; (5) adjusting fluid intake to the individual needs of the patient; (6) monitoring lung sounds for crackles and rhonchi indicating pulmonary congestion; and (7) monitoring heart sounds for murmurs or for S3 or S4 heart sounds. Bedside monitors or telemetry may record cardiac rhythms. Hypertension is sometimes seen following a stroke as the body attempts to increase cerebral blood flow.

After a stroke, the patient is at risk of deep vein thrombosis, especially in the weak or paralysed lower extremity.27 This is related to immobility, loss of venous tone and decreased muscle pumping activity in the leg. The most effective prevention is to keep the patient moving. Active range-of-motion exercises should be taught if the patient has voluntary movement in the affected extremity. For the patient with hemiplegia, passive range-of-motion exercises should be done several times a day. Additional measures to prevent deep vein thrombosis include positioning to minimise the effects of dependent oedema and the use of elastic compression gradient stockings or support hose. Intermittent pneumatic compression stockings may be ordered for bedridden patients. Deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis may include low-molecular-weight heparin. The nursing assessment for deep vein thrombosis includes measuring the calf and thigh daily, observing swelling of the lower extremities, noting unusual warmth of the leg and asking the patient about pain in the calf.

Musculoskeletal system

Musculoskeletal system

The nursing goal for the musculoskeletal system is to maintain optimal function. This is accomplished by the prevention of joint contractures and muscular atrophy. In the acute phase, range-of-motion exercises and positioning are important nursing interventions. Passive range-of-motion exercise is begun on the first day of hospitalisation.4,7 If the stroke is due to subarachnoid haemorrhage, the movement is limited to the extremities. The patient is taught to exercise actively as soon as possible. Muscle atrophy secondary to lack of innervation and activity can develop within 1 month following stroke.4,6,7

The paralysed or weak side needs special attention when the patient is positioned. Each joint should be positioned higher than the joint proximal to it to prevent dependent oedema. Specific deformities on the weak or paralysed side that may be present in patients with stroke include internal rotation of the shoulder; flexion contractures of the hand, wrist and elbow; external rotation of the hip; and plantar flexion of the foot. Subluxation of the shoulder on the affected side is common. Careful positioning and moving of the affected arm may prevent the development of a painful shoulder condition. Immobilisation of the affected upper extremity may precipitate a painful shoulder–hand syndrome.

As well as ensuring referral to a physiotherapist and occupational therapist, nursing interventions to optimise musculoskeletal function include: (1) trochanter roll at the hip to prevent external rotation; (2) hand cones (not rolled washers) to prevent hand contractures; (3) arm supports with slings and lap boards to prevent shoulder displacement; (4) avoiding pulling the patient by the arm to avoid shoulder displacement; (5) posterior leg splints, foot boards or high-topped tennis shoes to prevent footdrop; and (6) hand splints to reduce spasticity.6 Use of a footboard for the patient with spasticity is controversial. Rather than preventing plantar flexion (footdrop), the sensory stimulation of a footboard against the bottom of the foot increases plantar flexion. Likewise, there is disagreement on whether hand splints facilitate or diminish spasticity. The decision about the use of footboards or hand splints is made on an individual patient basis and following discussion with other members of the healthcare team.

Integumentary system

Integumentary system

The skin of the patient with a stroke is particularly susceptible to breakdown related to loss of sensation, decreased circulation and immobility. This is often compounded by age, poor nutrition, dehydration, oedema and incontinence. The nursing plan for prevention of skin breakdown includes: (1) pressure relief by frequent position changes, special mattresses or wheelchair cushions; (2) good skin hygiene; (3) emollients applied to dry skin; and (4) early mobility.6 The ideal position change schedule is side-back-side with a maximum duration of 2 hours for any position. Nurses should position the patient on the weak or paralysed side for only 30 minutes. If an area of redness develops and does not return to normal colour within 15 minutes of pressure relief, the epidermis and dermis are damaged. The damaged area should not be massaged because this may cause additional damage. Control of pressure is the single most important factor in both the prevention and the treatment of skin breakdown. Pillows can be used under lower extremities to reduce pressure on the heels. Vigilance and good nursing care are required to prevent pressure sores.

Gastrointestinal system

Gastrointestinal system

The stress of illness contributes to a catabolic state that can interfere with recovery. Neurological, cardiac and respiratory problems are considered priorities in the acute phase of stroke. However, the nutritional needs of the patient require immediate assessment and treatment. The patient may initially receive IV infusions to maintain fluid and electrolyte balance, as well as for administration of drugs. Patients with severe impairment may require enteral or parenteral nutritional support. Depending on the severity of the stroke, individual assessment and planning for nutrition are necessary.

The first oral feeding should be approached carefully because the gag reflex may be impaired. Before initiation of feeding, the gag reflex may be assessed by gently stimulating the back of the throat with a tongue blade. If a gag reflex is present, the patient will gag spontaneously. If it is absent, feeding should be deferred and exercises to stimulate swallowing should be started. A speech therapist or occupational therapist, if available, may design this program. However, the nurse, if accredited, may be responsible for developing the program in some clinical settings.27

To assess swallowing ability, the speech therapist should be consulted; they will elevate the head of the bed to an upright position (unless contraindicated) and give the patient a small amount of crushed ice or ice water to swallow. If the gag reflex is present and the patient is able to swallow safely, the speech pathologist may proceed with feeding, with the nurse monitoring the patient for signs of aspiration.

After careful assessment of swallowing, chewing, gag reflex and pocketing, oral feedings should be ongoing. Mouth care before feeding helps stimulate sensory awareness and salivation and can facilitate swallowing.27 The patient should remain in a high-Fowler position, preferably in a chair with the head flexed forwards for the feeding and for 30 minutes following oral intake. Foods should be easy to swallow and provide enough texture, temperature (warm or cold) and flavour to stimulate a swallow reflex. Crushed ice can be used as a stimulant. The patient is instructed to swallow and then swallow again. Pureed foods are not usually the best choice because they are often bland and too smooth. Thin liquids are often difficult to swallow and may promote coughing. Milk products should be avoided because they tend to increase the viscosity of mucus and increase salivation. Food should be placed on the unaffected side of the mouth. The nurse should ensure an unrushed, non-stressful atmosphere. Feedings must be followed by scrupulous oral hygiene because food may collect on the affected side of the mouth.

The most common bowel problem for the patient who has experienced a stroke is constipation.28 Physical activity promotes bowel function. Patients may prophylactically be given stool softeners and/or fibre (psyllium). If the patient does not have a daily or every-other-day bowel movement, they should be checked for impaction. Patients with liquid stools should also be checked for stool impaction. Depending on the patient’s fluid balance status and swallowing ability, fluid intake should be 1800–2000 mL per day and fibre intake up to 25 g per day. Laxatives, suppositories or additional stool softeners may be ordered if the patient does not respond to increased fluid and fibre. Similarly, enemas should be used only if suppositories and digital stimulation are ineffective, because they cause vagal stimulation and increase ICP.6

Urinary system

Urinary system

In the acute stage of stroke, the primary urinary problem is poor bladder control, resulting in incontinence. Efforts should be made to promote normal bladder function and avoid the use of indwelling catheters. If an indwelling catheter must be used initially, it should be removed as soon as the patient is medically and neurologically stable. Long-term use of an indwelling catheter is associated with urinary tract infections and delayed bladder retraining.6 An intermittent catheterisation program may be used for patients with urinary retention because of the lower incidence of urinary infections. An alternative to intermittent catheterisation is the external catheter for male patients with urinary incontinence. External catheters do not alleviate the problem of urine retention. Bladder overdistension should be avoided.

A bladder retraining program consists of: (1) adequate fluid intake, with the majority of fluid given between 7 am and 7 pm; (2) scheduled toileting every 2 hours during the day and every 3–4 hours at night, using a bedpan, a commode or the bathroom; and (3) noting signs of restlessness, which may indicate the need for urination.

Communication

Communication

During the acute stage of stroke, the nurse’s role in meeting the psychological needs of the patient is primarily supportive. An alert patient is usually anxious because of lack of understanding about what has happened and because of difficulty with, or inability to, communicate. The patient is assessed both for the ability to speak and for the ability to understand. The patient’s response to simple questions can give the nurse a guideline for structuring explanations and instructions.29 If the patient cannot understand words, gestures may be used to support verbal cues. It is helpful to speak slowly and calmly, using simple words or sentences to enhance communication. The nurse must give the patient extra time to comprehend and respond to communication. The stroke patient with aphasia may be easily overwhelmed by verbal stimuli.30 (Guidelines for communicating with a patient who has aphasia are presented in Box 57-6.) Evaluation and treatment of language and communication deficits are often done by a speech therapist once the patient has stabilised.

BOX 57-6 Communicating with a patient with aphasia

1. Decrease environmental stimuli that may be distracting and disruptive to communication efforts.

2. Treat the patient as an adult.

3. Present one thought or idea at a time.

4. Keep questions simple or ask questions that can be answered with ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

5. Let the person speak. Do not interrupt. Allow time for the individual to complete their thoughts.

6. Make use of gestures or demonstrations as an acceptable alternative form of communication. Encourage this by saying, ‘Show me …’ or ‘Point to what you want’.

7. Do not pretend to understand the person if you do not. Calmly say you do not understand and encourage the use of non-verbal communication, or ask the person to write out what they want.

8. Speak with normal volume and tone.

9. Give the patient time to process information and generate a response before repeating a question or statement.

10. Allow body contact (e.g. the clasp of a hand, touching) as much as possible. Realise that touching may be the only way the patient can express feelings.

11. Organise the patient’s day by preparing and following a schedule (the more familiar the routine, the easier it will be).

12. Do not push communication if the person is tired or upset. Aphasia worsens with fatigue and anxiety.

Sensory–perceptual alterations

Sensory–perceptual alterations

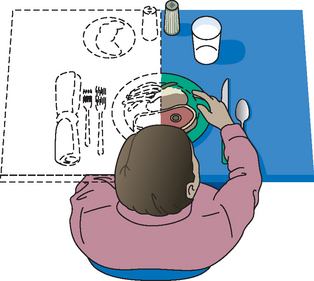

Homonymous hemianopsia (blindness in the same half of each visual field) is a common problem after a stroke (see Fig 57-10).31 Persistent disregard of objects in part of the visual field should alert the nurse to this possibility. Initially, the nurse helps the patient to compensate by arranging the environment within the patient’s perceptual field, such as arranging the food tray so that all foods are on the right side or the left side to accommodate for field of vision (see Fig 57-12). Later, the patient learns to compensate for the visual defect by consciously attending or scanning the neglected side. The weak or paralysed extremities are carefully checked for adequacy of dressing, for hygiene and for trauma.6

Figure 57-10 Spatial and perceptual deficits in stroke. Perception of a patient with homonymous hemianopsia shows that food on the left side is not seen and thus is ignored.

Figure 57-12 Assistive devices for eating. A, The curved fork fits over the hand. The rounded plate helps keep food on the plate. Special grips and swivel handles are helpful for some persons. B, Knives with rounded blades are rocked back and forth to cut food. The person does not need a fork in one hand and a knife in the other. C, Plate guards help keep food on the plate. D, Cup with special handle.

In the clinical situation, it is often difficult to distinguish between a visual field cut and a neglect syndrome. Both problems may occur with strokes affecting either the right or the left side of the brain. A person may be unfortunate enough to have both homonymous hemianopsia and a neglect syndrome, which increases the inattention to the weak or paralysed side.31 A neglect syndrome results in decreased safety awareness and places the patient at high risk of injury. Immediately after the stroke, the nurse must anticipate potential safety hazards and provide protection from injury. Safety measures can include close observation of the patient, elevating side rails, lowering the height of the bed and video monitors. The use of restraints and soft vests is avoided because this may agitate the patient and confine normal movements.

Other visual problems may include diplopia (double vision), loss of the corneal reflex and ptosis (drooping eyelid), especially if the area of stroke is in the vertebrobasilar distribution. Diplopia is often treated with an eye patch.32 If the corneal reflex is absent, the patient is at risk of corneal abrasion and should be observed closely and protected against eye injuries. Corneal abrasion can be prevented with artificial tears or gel to keep the eyes moist, and an eye shield (especially at night). Ptosis is generally not treated because it usually does not inhibit vision.

Ambulatory and home care

Ambulatory and home care

The patient is usually discharged from the acute care setting to home, an intermediate or long-term care facility or a rehabilitation facility. Criteria for transfer to rehabilitation may include the patient’s ability to participate in therapies for a minimum number of hours per day. Functional status scales such as the Barthel Index, Modified Rankin Scale and Functional Independence Measure are used to evaluate the patient.33 Ideally, discharge planning with the patient and family starts early in the hospitalisation and promotes a smooth transition from one care setting to another. The multidisciplinary team provides the guidance for the appropriate care required after discharge. If the patient requires a short- or long-term healthcare facility, the team can make appropriate referrals that allow time for family selection and arrangement of care. A critical factor in discharge planning is the patient’s level of independence in performing ADLs.33 If the patient is returning home, the team can make referrals for necessary equipment and services in preparation for discharge.