![]()

The pathogenic Ascomycota (see Chapter 1 and Table 1.1) are not as dependent on water as the zoosporic fungi. Their sexual structures, the sac-like asci that contain the haploid ascospores, are usually protected from the extremes of the environment by a fruit body, the ascocarp, composed of fungal tissue. The details of ascus and ascospore form, the way in which the asci are arranged, the mechanism of ascospore discharge and the structure and shape of the ascocarp determine the place of these fungi in modern classifications. The asexual spores*, the conidia, lack flagella and are usually distributed by wind or insect carriers. As with all pathogenic fungi, both the sexual and asexual spores remain vulnerable until they have germinated and sent new hyphae into the moist internal environment of their plant hosts.

After germination of the spore on the surface of the plant, the germ tube usually forms an appressorium and infection peg, which grows through the cuticle, where it expands to form a subcuticular hypha. This either spreads further under the cuticle or grows down between the epidermal cells and colonises the tissues of the leaf or stem. There the subsequent relationship with the host may be biotrophic, hemibiotrophic or necrotrophic according to species.

When the ascocarps are formed they have a comparatively long life, and the capacity to survive the long periods of desiccation that may occur before high humidity once more makes conditions favourable for them to shoot their spores through the boundary layer of still air that covers all surfaces into the turbulent air in which they are dispersed. This gives them a certain independence from their moist substrate and also the capacity to spread spores over considerable distances to new hosts.

We deal here with the Ascomycota that cause leaf curls, scabs, spots and rots. Those that cause wilts and powdery mildews will be considered in Chapters 6 and 8 respectively.

STRIPPED FOR ACTION: THE TAPHRINALES

The first group of parasitic Ascomycota we describe are not in fact recognisable from the introductory description because they do not form an ascocarp. Instead, following infection, the fungal mycelium spreads between the leaf cells, eventually forming a well marked layer beneath the cuticle. This produces large numbers of asci, which then poke through the cuticle onto the leaf surface. The relationship with the host is biotrophic. Although haustoria are never produced, hyphae may penetrate the living cells of the leaf and become surrounded by the cell membrane. Invariably, infection leads to abnormal growth of the tissues of the host.

One of the most spectacular members of this group is Taphrina deformans, the cause of peach leaf curl disease (Plates 3). Affected peaches (Prunus persica) and their relatives, such as nectarines (P. persica var. nectarina) and occasionally almonds (P. amygdalus), have greatly distorted, blistered and incurled leaves in the spring. As the disease develops the leaves become patchily red or purple, fading to yellow and finally brown; in their red or purple phase they look at first sight like strips of meat hanging on the tree. Before the colours fade the upper surfaces of infected leaves become covered with a greyish bloom. On examination this is seen to be formed by the serried ranks of asci breaking through the cuticle to appear naked on the surface. Infected leaves fall prematurely, and it is the resulting massive loss of functional leaves that weakens the tree and interferes with fruiting.

The elongated asci on the leaf surface each produce eight ascospores, which sometimes bud within the ascus or after being forcibly discharged, thus increasing the inoculum. Infection by ascospores requires humid conditions and peaches only escape infection in dry, semi-arid regions such as the southwest USA, and in dry irrigated areas such as occur in Washington State in the northwest USA. In glasshouses in Britain careful watering and humidity control are required to ensure freedom from the disease without spraying.

Confusion over the method of infection delayed the development of effective control measures for peach leaf curl for many years. It was at first believed that the fungus infected the young shoots and was present inside the buds, so that spraying had to be directed at the emerging leaves, with critical timing. When it was discovered that leaf infection was initiated from spores overwintering on the surface of the shoots the efficacy of winter spraying with fungicides was easily demonstrated. Here we see the importance of a thorough understanding of the infection process for the development of good control measures.

It is not easy to identify clearly defined lesions in the pathogenic relationship between Taphrina deformans and its hosts. Indeed, when the other common Taphrina spp. on wild plants are examined, and there are over a hundred of them worldwide, some delimitation of infection may be seen, but no marked, visible tissue reaction to contain the infecting mycelium. With T. populina, which commonly occurs on the leaves of poplars (Populus italica and P. nigra x serotina) in Britain and mainland Europe, the infected portion of the leaf expands more than the uninfected portions to form an inverted cup, its mouth facing downwards (Fig. 5.1). Masses of golden yellow asci are produced within this cup on the underside of the leaf. There may be two or three such infected areas on each leaf, with no regular size, although they never occupy the whole of the leaf area. Other species attack the individual catkin scales of poplar, alder (Alnus spp.) and birch, causing swelling and abnormal growth. Still others attack the fruits of cultivated and wild plums (Prunus spp.) to form ‘pocket plums’ with swollen, misshapen hollow fruits, the surfaces of which are covered with a bloom of asci (Fig. 5.2). These occur variously in Britain, in mainland Europe and also, with slight taxonomic differences, in the USA. Here the fungal infection is limited by the size of the organ it attacks and from which it does not spread.

FIG. 5.1

Taphrina populina causing distortion of leaves of poplar (Populus sp.) in Cambridge. (D.S. Ingram)

FIG. 5.2

‘Pocket plums’ resulting from infection by Taphrina padi on bird cherry (Prunus padus) at Juniper Bank, Peeblesshire, Scotland. (Debbie White, Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh.)

Other Taphrina spp. cause witches’ broom disease on a number of trees such as birch (T. betulina) (Fig. 5.3) and T. wiesneri on cherry (Prunus avium and P. cerasus) in Britain and on other genera in mainland Europe and the USA. In these cases infection of the bud or developing shoot leads to a proliferation of the apex and ultimately a spectacular much branched structure, the eponymous witches’ broom.

THE ENCLOSED ORDERS

Turning now to those members of the Ascomycota where the asci are developed and protected within an ascocarp (Fig. 5.4), we find first a group of fungi that were once called quite simply the ‘Plectascales’ or ‘Plectomycetes’, and which have completely closed ascocarps (cleistothecia) containing rounded asci (Fig. 5.4a). The mature ascospores are released into the environment by the decay of the enclosing structures. On the whole the members of this group are not pathogenic to plants but are members of the saprophytic soil flora, obtaining nutrients by degrading various dead natural substrates. A few, such as the Eurotiales (known as Penicillium and Aspergillus in the anamorph stages) cause soft rots of fruits and storage organs such as bulbs and corms, especially if these are over-mature or wounded. The pale brown rots caused by Penicillium expansum, decorated with the blue-green conidia of the pathogen, are frequently seen on ripe apples damaged by birds or wasps (Fig. 2.3). Similarly the blue-green conidia of P. italicum may be seen on damaged oranges in the fruit bowl and may spread to neighbouring fruit, while other Penicillium spp. are found as basal rots of narcissus (Narcissus spp.), tulip (Tulipa spp.) and hyacinth (Hyacinthus orientalis) bulbs after winter storage.

FIG. 5.3

‘Witches’ broom’ of birch (Betulina sp.) resulting from infection by Taphrina betulina, near Stobo, Peeblesshire, Scotland. (D.S. Ingram.)

FIG. 5.4

The diversity of ascocarps produced by members of the Ascomycota: (a) a cleistothecium, as in Erotium; (b) a perithecium, here embedded in host tissue, as in Venturia; (c) perithecia embedded in a perithecial stroma, as in Claviceps; (d) an apothecium, here arising from a sclerotium, as in Sclerotinia. (Illustrations (not to scale) by Mary Bates.)

The Eurotioles are distinct from the remaining fungi with protected asci, which were once called the ‘Pyrenomycetes’ or flask fungi. A clearly defined group of these have dark-walled ascocarps (perithecia) with longish necks, giving them a flask-like appearance (Fig. 5.4b). The ascospores are shot out from the elongate asci through a hole at the top of the neck, caught up by the wind and dispersed to new hosts. A parallel group, the Hypocreales, sometimes forms its (mostly) coloured ascocarps on or in a thickened tissue called a stroma (Fig. 5.4c) and is associated with a range of well-known anamorph genera such as Fusarium, Verticillium, Gliocladium and Trichoderma. The fungi in this order also produce a range of metabolites that are poisonous or react with the metabolism of other fungi or green plants with sometimes spectacular effects.

A third group, in which the elongate asci are formed on the surface of an open disc or saucer (the apothecium), were once called the ‘Discomycetes’ (Fig. 5.4d). Most are saprophytic, but the Sclerotiniaceae are pathogens.

APPLE SCAB – CLASSIC ‘PYRENOMYCETE’ DISEASE

Venturia inaequalis (Dothideales) contrasts sharply with Taphrina in all the details of its pathological life history. It is the cause of apple scab, which has probably been with us since the Garden of Eden (Plate 4) The cosmetically attractive fruits that we find in the supermarket, polished and shining yellow, green or rosy red, are a credit to the plant pathologists who devised the technology to control the disease. We can still find infected fruit and leaves on crab apples (Malus sylvestris) and on eating apples (M. pumila) in gardens, in tumbledown orchards and on some country market stalls displaying produce from these sources. In the orchards of our ancestors unblemished fruits were the exception.

Infected fruits and leaves show circular or irregular, brownish, velvety (later corky) scabs, 5–10 mm across. These do not appear to affect the flesh of the apple or the deeper tissues of the leaf. They may, if the infection occurs early enough in the development of fruit, cause cracking of the surface, sometimes allowing the entry of rotting organisms. Sometimes infections may not develop immediately into lesions, but cause scabs to appear later in the season or on apples in store. Scrapings from the scabs, when examined with the microscope, are found to contain characteristic one or two-celled conidia. These asexual spores are known by the anamorph name, Spilocaea pomi, and are responsible for much of the summer spread of the pathogen.

The infection is initiated afresh each season. Much of it, and almost all in certain situations, comes from ascocarps which are formed in the spring by the pathogen growing saprophytically on overwintered leaves infected the previous summer. They release their ascospores to be carried by the wind to the surface of the newly emerging leaves, fruit buds and eventually young fruits. The ascospore (or later the conidia) germinate on the leaf surface and form an appressorium from which a germ tube grows through the young cuticle to produce hyphae. These grow between the cuticle and the upper wall of the epidermal cells, eventually forming a layer, several hyphae thick, from which are developed the conidia (Spilocaea). The fungal growth eventually ruptures the cuticle, exposing the spores to the air. Further infection takes place on both leaf surfaces, that on the upper surface being strictly limited in area while that on the lower surface spreads along the veins and midrib to give a less clearly defined infection. With some varieties and in some situations infection of young twigs leads to cracking and cankering of the twigs, and overwintering of conidia within these cracked areas.

In living leaves, even when heavily infected, the fungal mycelium is largely restricted to the outside of the leaf between cuticle and epidermis. Contact with living tissue may occur later as intercellular hyphae begin to penetrate further into the leaf. The situation changes again when the leaves die and fall to the ground. The subcuticular mycelium now begins to colonise the whole dead leaf and then, as winter passes, the mycelium aggregates in certain areas and ascocarps are formed. Eventually these produce asci and ascospores, which are released through the beak-like neck of the perithecium which emerges on the surface of the leaf. The ascospores consist of two unequal cells, either or both of which may germinate to initiate a new infection and begin the cycle again.

Venturia thus has a restricted saprophytic phase, which follows from the foothold obtained in the leaves in its biotrophic phase; from this foothold it can expand into dead tissue ahead of possible competition from other saprophytes. However, it never grows as a free-living saprophyte, competing successfully for nutrients with other saprophytes on non-host tissues.

Control of apple scab has been attempted in four ways. Firstly, attempts were made to prevent infection by spraying with fungicides, beginning each year at bud-burst. The first fungicide used was Bordeaux mixture, but it had the disadvantage of russeting the fruit and was replaced by lime sulphur, which could also be toxic in some situations. Elaborate spraying schedules were developed relating to the time of opening of the fruit buds, designed to maintain a complete cover of the fungicide on fruit and leaf surfaces throughout the growing period. Insecticides were also incorporated, and the floor of apple orchards could become like a desert with the weight of toxic material applied to the trees and incidentally to the soil below. Gradually new organic fungicides and insecticides were produced and methods developed for applying them at low volume in less water, thus reducing the cost of each application. Methods of cultivating and pruning the trees changed too, restricting their height so that there was less need for powerful spraying machinery projecting large quantities of liquid high in the air.

Secondly, attempts were made, both in the USA and Britain, to develop a predictive system to forecast the annual development of the disease epidemic. By trapping the fungal ascospores produced in an apple orchard in the spring it was possible to correlate the numbers of spores with rainfall, relative humidity and temperature and from this develop a method for predicting the time of appearance of the first spore showers and the time when the first spray should be applied. Later infection was routinely controlled by spraying at seven-day intervals. The critical factors controlling the initial spore discharge from asci were rainfall and temperature. This approach was also valuable in making growers aware of the natural history of the disease, an awareness which was translated into good management practices in a number of areas.

Thirdly, an attempt was made to control the discharge of the ascospores from the leaves on the orchard floor. This was pursued more energetically in the USA than in Britain, where the perceived importance of stem lesions in varieties such as Cox’s Orange Pippin directed attention from the leaves as the main source of overwintering inoculum. The demonstration in the USA that substances such as dinitro-orthocresol could eradicate ascocarps on the orchard floor introduced a new element into the control of the disease.

A final approach was to attempt to develop varieties resistant to the disease. Observations showed differences in the intensity of attack on different apple varieties, some not being infected at all. Moreover, certain wild species, such as Malus sikkimensis, were apparently resistant to attack by the pathogen. It was hoped to use this resistance in the breeding of commercially acceptable apple varieties.

Scientific interest in breeding for resistance was fuelled by the possibility of an even greater prize. The similarity between the fruit bodies and asci of Venturia and those of Neurospora crassa, the bread mould, with which a great deal of classical genetic analysis had been carried out, suggested that detailed genetic analysis of Venturia might perhaps lay bare the metabolic steps in the interaction between pathogen and host.

Not surprisingly, no successful resistant commercial varieties of apple emerged from this breeding programme. The market makes great demands on potentially successful varieties. The fruit must look good, travel well, store well, taste good, yield well, outclass the already established varieties, have a good orchard habit, not be subject to biennial bearing, stand up to spraying and picking and so on. To meet all the commercial requirements and to incorporate resistance to disease in a crop with a life cycle as long as that of the apple is a tall order indeed. Moreover, the genetics of resistance proved to be hard to handle; by 1988 genes controlling virulence had been identified at no less than 19 loci!

As far as the genetic analysis of pathogenicity went, however, some interesting facts emerged, although the great breakthrough still eluded the investigators. It was found that matching genes for virulence and avirulence at particular loci gave either a ‘lesion’ or a ‘fleck’. In the first the fungus became established in the leaf, spread for some distance under the cuticle and sporulated freely. In the second it germinated and produced appressoria but thereafter the progress of the mycelium was sharply restricted by a hypersensitive reaction (see Chapter 3). Although the further detailed analysis of pathogenicity proved impossible, enough had been done to suggest that modern molecular genetic methods using this system as a base could expand our knowledge of the interactions between pathogen and host.

Other Venturia spp. that infect members of the rose family (Rosaceae) are: V. pirina, which infects pears (Pyrus communis) in a parallel fashion to V. inaequalis on apples; V. crataegi, which affects hawthorn; and V. cerasi, which occasionally attacks cherries. There are also three Venturia spp. that occur on willows (Salix spp.) in Europe, of which V. saliciperda is a serious problem on Salix alba, S. amygdalina and S. babylonica, especially where they are planted as specimen trees in areas with moist climates.

A relative of Venturia, Hormotheca robertiani, is a pathogen of wild herb Robert (Geranium robertianum) throughout Europe. It is found on the upper sides of the leaves, especially the older ones, and consists of a layer of mycelium one cell thick, which spreads under the cuticle without destroying the underlying cells. There is no obvious external sign of the parasite at this stage and no lesion. Eventually the fungal layer begins to thicken in discrete areas and builds the flattened ascocarps in which the asci are formed. This subcuticular fungus seems almost to have adopted the strategy of the mutualistic fungi (see Chapter 7) in reducing the activities which might signal its presence and elicit a resistance reaction.

Another interesting variation of the pathogenic pattern shown by Venturia is seen in the life cycle of Apiognomonia erythrostoma, the cause of cherry leaf scorch, which is widespread on Prunus spp. in mainland Europe. In Britain it is particularly prevalent on the wild cherry P. avium, especially more recently in the south of England. Its interest for us lies in the leaf infections that occur as the leaves are first opening but do not show until they are mature in the middle of summer, when small lesions appear. Infected leaves then fail to form an abscission zone, and instead of falling off the tree in the autumn can be found hanging as brown and slightly shrivelled flags throughout the winter. Ascospores are formed on these leaves in the spring. Here we have a delay in symptom expression, for the fungus is apparently latent in the leaves until midsummer. The trigger for symptom expression is not known. The other interest lies in the failure of the leaves to absciss, which suggests that the fungus is interfering with the normal hormone control of leaf abscission in the plant.

FIG. 5.5b

FIG. 5.5c

‘Take-all’ of wheat caused by Gaeumannomyces graminis at Cambridge, England: (a) an infected root (right) beside a healthy one (left); (b) whiteheads on artificially infected plants (right hand group) beside healthy plants (left hand group); (c) dark runner hyphae on the surface of infected roots. (P.R. Scott, CAB International.)

TAKE ALL, THE MYSTERIOS ASSASSIN

Take-all is one of the most important foot-rot diseases of cereals worldwide (Fig. 5.5a). In conditions favourable to the disease it causes the death of large patches of maturing cereals, the individual plants showing ‘whiteheads’ of ears that have failed to fill (Fig. 5.5b). A spectacular cause of crop failure in the USA, Canada and Australia, it occurs widely in Britain and mainland Europe, although with less devastating results. Even so, some say that the yield of wheat may often be reduced by 10% as a result of take-all infection. Gaeumannomyces graminis, the causal organism (classified in the Magnaporthaceae; its order has yet to be determined) attacks the roots of wheat and barley and also of certain wild grasses. Oats are attacked by a forma specialis. Characteristic dark hyphae (Fig. 5.5c) spread over the surface of the roots of infected plants and send short non-pigmented branches into their tissues, destroying them. Once the pathogen reaches the endodermis, the layer of cells surrounding the central vascular region of the root, individual cells appear to slow down the progress of infection by encasing the invading hyphae in wall material, forming structures called lignitubers. A build up of dark hyphae around the stem and lower leaf bases is also characteristic of the disease. The ascocarps are not common, but when they appear on the lower leaf bases they are flask-shaped and immersed in the tissues. The asci project their elongated ascospores into the air through the short, open, beak-like necks positioned to one side of the ascocarp.

Our knowledge of the natural history of pathogenic fungi derives from intensive work on a limited number of commercially important diseases of crop plants and the extrapolation of this knowledge more widely. Each study yields an insight into a different facet of disease and there is no doubt that the study of Gaeumannomyces graminis has allowed the construction of a theoretical framework for understanding the ecology of a great range of soil-borne plant diseases and has elucidated the nature of pathogenesis in a wide range of disease situations.

Much of this success can be attributed to the percipient work of Denis Garrett, who devoted his life to research on this organism and developed important generalisations about soil-borne diseases from his studies. His work was characterised by extreme simplicity and great attention to detail. Others had shown the causal relationship between G. graminis and take-all, but when he started work in 1929 the disease was still full of mystery. It appeared in some fields and not in others; its presence seemed to be related to soil type, but healthy crops could be grown on the suspect soils; application of nitrogen fertilisers sometimes favoured the disease and sometimes the plant; it was a parasite but it also seemed to exist saprophytically in the soil. How could these anomalies be reconciled?

What Garrett did was to recognise that the variability of conditions in the field made it virtually impossible to draw meaningful conclusions from field observations alone. He therefore determined to create conditions where as many environmental factors as possible were strictly controlled. Instead of spending time building complex equipment he chose to use cheap glass tumblers or jam jars, in which he placed field soils that had been dried and remoistened to a standard. Nutrients were added to these soils in standardised form, whilst moisture loss and temperature fluctuations were controlled by frequent weighing and topping up of the containers, placed in standard microbiological incubators. In these controlled conditions inoculum of the fungus was allowed to colonise standard lengths of straw buried in the soil, and these were later graded for colonisation and subjected to biological tests for infectivity. These were methods which any one of us could reproduce in our own homes, their one disadvantage being the sheer hard work required to achieve maximum uniformity. Many of the research students who worked with Garrett looked up wistfully from the straw they were painstakingly cutting into exact lengths to their neighbours whose electronic machines seemed to produce results with effortless ease. But Garrett’s methods, carefully used, and accompanied by much thought and hypothesising, yielded valuable results and information.

The fungus survives the intercrop period on the roots or stubble debris of previously infected crops and spreads to neighbouring plants, mostly in early summer. It is reduced by adequate rotation but, where cereal follows cereal, as is now common in many agricultural systems, as little as 1% of infected plants can give rise in the following year to a serious loss of crop. The disease is most. serious on light, loose alkaline soils poor in nutrients but reasonably moist. The critical point in the life cycle seems to be the saprophytic phase when the fungus is surviving in the dead crop residues. At this time the fungus is very sensitive to competition from other soil saprophytes, and its survival is also very dependent on the amount of nitrogen available to support fungal growth. Hence nitrogen applied early, even the year before, will encourage the survival of the fungus. Conversely, however, if infection has begun, nitrogen-manuring of the growing crop in early spring will enable the plant to produce new roots to replace the infected ones and to recover from the disease.

Based on this framework, farming methods that favoured high yields of wheat and barley and at the same time discouraged infection with take-all were worked out and put into practice. Today the disease is rarely a problem except in situations where agricultural systems are changing from a standard rotation to the serial cultivation of wheat or barley. It has been found, quite independently of Garrett, that take-all increases, in spite of the appropriate agronomic measures, for the first three or four years of serial cultivation, at which point the amount of take-all begins to decline to levels where it no longer threatens crop yields. The cause of this take-all decline is probably a build-up in the soil of fluorescent bacteria and other microorganisms which are competitors of Gaeumannomyces and other fungi.

Here we see a pathogen able to infect a range of cereal and grass species but sharply recognised and excluded by others. Where plants are attacked, the amount of inoculum and its vigour, which Garrett called ‘inoculum potential’, appear to be important in the success of the attack, and this vigour is determined by the success of the saprophytic survival of the organism in cereal and grass residues. But, and here is one of the unexpected bonuses of Garrett’s studies, the saprophytic phase is sensitive to the presence of other soil-inhabiting organisms, and either grows more slowly or stops growing completely. When a range of root-inhabiting organisms is examined, the parasitic forms have nearly all lost their ability to compete in a soil environment. Garrett went on to theorise further from these observations and to suggest that the qualities that make for good saprophytic existence (i.e. rapid growth, the release of large quantities of exogenous enzymes and the production of antibiotic substances) are in fact the features which make for easy ‘recognition’ of the fungus by the host and its exclusion by the mechanisms already alluded to in Chapter 3. These and others of his ideas, too numerous to iterate here, have become the coinage of modern plant pathology and demonstrate how, with simple tools and careful thought, great advances can be made. Perhaps we should note, in conclusion, Garrett’s remarkably shrewd approach to his choice of pathogen for a lifetime of study. Not for him the pure ‘academic’ approach but, as he wrote in the preface to his book Pathogenic Root-Infecting Fungi (1970): ‘I need stress no further this economic aspect of their [root-infecting fungi] importance, except to remark that more information, more co-operation and more financial assistance are available for the study of an organism of economic importance than for one that is not; all university biologists must now be aware of this – though some may refuse to act upon it.’

THE COLOURFUL MEDICIS, A POSIONOUS BUNCH OF FUNGAL PATHOGENS

We turn now to some members of the Ascomycota with coloured ascocarps. Those discussed here are grouped in the families Hypocreaceae and Clavicipitaceae.

A very familiar member of the Hypocreaceae is the coral spot fungus (Nectria cinnabarina), which appears as small cinnabar-red cushions (0.1–0.5 mm in diameter) on the surface of dead branches of a variety of trees and shrubs (Fig. 5.6a). It is especially common on lime (Tilia spp.), horse chestnut (Aesculus hippocastanum) and sycamore (Acer pseudoplatanus). Examination of the cushions, the Tubercularia anamorph, reveals small oblong conidia borne all over the cushion surface. The ascocarps (about 0.5 mm in diameter) are much harder to find but invariably appear where, for example, pea-sticks of sycamore have been left in the ground over winter. Then the cinnabar-red cushions are replaced by the dark red clusters of ascocarps at soil level (Fig. 5.6b).

With this behaviour the fungus looks like a good saprophyte, but it can also behave as a parasitic necrotroph. It frequently causes a dieback of soft fruit, especially redcurrant (Ribes rubrum) and gooseberry (R. uva-crispa) bushes, and it can also attack young trees, causing spectacular dieback of individual branches in the summer. The fungus apparently cannot make a direct entry into the plant through leaves or stems, and seems to enter through pruning wounds and broken branches. From these infection sites it enters the woody tissues of the xylem, spreading upwards and downwards as well as laterally. When, in the redcurrant, it spreads laterally sufficiently to girdle the stem, the whole bush collapses. The invasion of the plant through the vessels of the xylem and their apparent blockage, either by interaction with the poisonous products of the fungus or by the hyphae themselves, foreshadows the wilt fungi, many of which are related and which are described in detail in Chapter 6.

FIG. 5.6a

FIG. 5.6b

Nectria cinnabarina, cause of coral spot of dying trees and shrubs: (a) the cinnabar-red conidial cushions (0.1–0.5 mm diameter); (b) dark red ascocarps (approximately 0.5 mm diameter); both at Juniper Bank, Peeblesshire, Scotland. (Debbie White, Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh.)

Nectria galligena, a close relative of the coral spot fungus, is the cause of canker of apple trees (Fig. 5.7). The conidial pustules (anamorph name Cylindrocarpon mali) are here buff-coloured and produce either unicellular spores or sickle-shaped spores with one to five septa. Infection of the apple branch takes place through small cracks in the bark caused by natural leaf fall, by woolly aphids (Eriosoma lanigerum) or by the apple scab fungus Venturia inaequalis. The pathogen spreads into the bark tissues and is temporarily impeded by the production of corky layers. There is no regrowth of host tissue under the original infection and the limited annual reinfection of the stem growth on the margin of the infected area leads to the development of a crater-shaped canker. Some cankers girdle the stem, with the subsequent death of the branch or of the tree. The disease is found on apples in moister areas, is worse on some soils than others and can be affected by the rootstock and vigour of the tree. It particularly affects certain old varieties such as ‘James Grieve’, ‘Cox’s Orange Pippin’ and ‘Worcester Pearmain’, but is rarely seen on ‘Bramley’s Seedling’, ‘Sturmer Pippin’ and ‘Blenheim Orange’.

Gibberella zeae, with blackish-blue ascocarps, bears some resemblance to Nectria. It infects cereals, killing the young plants, and also appears as a pinkish, mycelium bearing sickle-shaped, multicellular conidia on the ears in wet weather. This conidial phase (the anamorph) is given the name Fusarium graminearum. The fungus is sometimes troublesome on maize in the USA and occurs with varying severity on wheat and barley. Its most interesting feature is the production of mycotoxins (fungal toxins that affect animals and/or humans) such as zearalenone in the infected grain. The first spectacular mycotoxins to be identified were the aflatoxins formed in ground nuts contaminated with the saprophytic fungus Aspergillus flavus and its relatives. In the initial outbreak in 1960 they were responsible for the death of 100,000 turkey poults from ‘Turkey X disease’, then of unknown origin. The aflatoxin B1 is now regarded as one of the most carcinogenic substances known. From the time of the first outbreak, attempts were made to associate sickness in animals, and to a lesser extent in humans, with the contamination of feed grains by fungi. The process of identifying the different syndromes and relating them to specific fungal contamination was a slow one, but a clear connection was made quite early between grain contaminated with Gibberella zeae and a number of conditions, most particularly infertility in pigs.

FIG. 5.7

Canker of apple caused by Nectria galligena at Aberlady, East Lothian, Scotland. (D.S. Ingram.)

Zeranol, a synthetic oestrogen with growth-promoting properties, was produced from zearalenone and used extensively in the 1970s and 1980s on castrated beef animals to promote muscle growth, but the use of such compounds is now prohibited.

Another Gibberella species, G. fujikuroi, attacks cereals in subtropical areas. Morphologically identical forms are found on tropical fruit, particularly banana (Musa spp.) and pineapple (Ananas comosus). The anamorph is known as Fusarium moniliforme. In rice (Oryza sativa) some plants are killed but others, at least initially, grow taller than their neighbours. Work by P.W. Brian on the cause of this bakanae (foolish seedling) disease showed that the overgrowth was caused by material secreted by the fungus, later identified as gibberellic acid. This turned out to be one of a series of related terpenoids, the gibberellins, many of which are important plant hormones. Gibberellic acid is now used commercially to induce fruit set without pollination in the production of seedless grapes, for example, and in brewing to speed up and synchronise the germination of barley during the malting process.

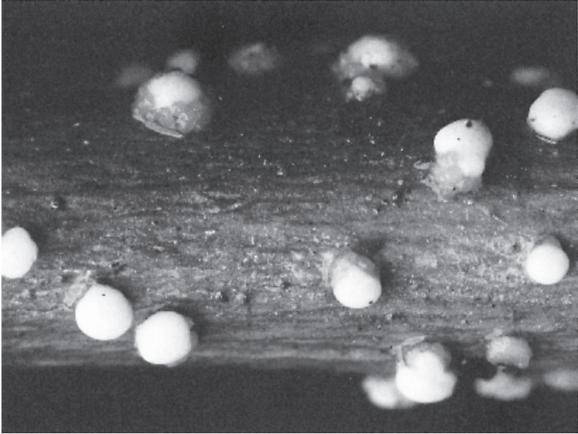

FIG. 5.8

Sphacelia (anamorph) stage of ergot (Claviceps purpurea): a droplet of honeydew containing conidia on an infected flower of sea lyme grass (Elymus arenarius) at Gullane, East Lothian, Scotland (D.S. Ingram.)

Two members of the related family Clavicipitaceae demand our attention. The first, Epichloe typhina, cause of choke disease of a range of grasses (Plate 4), is especially conspicuous on cocksfoot (Dactylis glomerata). The fungus forms a creamy sheath, later turning golden yellow to orange, around the basal parts of the leaves and stems of infected plants. Single-celled conidia form on the surface of this fungal sheath (technically a stroma), which then develops within itself a number of flask-shaped ascocarps containing asci, each with eight filamentous septate ascospores. The openings of these ascocarps can be seen as minute pits all over the surface of the stroma. Flowering of the grasses is impeded. The mycelium grows systemically throughout the plant and is transmitted in seeds or by vegetative propagation. The role of the ascospores in infecting flowers varies in different genera and requires further investigation. Infected plants are said to be toxic to animals.

There are many similarities between Epichloe typhina and our second example, Claviceps purpurea, the cause of ergot disease of cereals and grasses (Plate 3 and Figs. 5.8 and 5.9). The outstanding characteristic of ergot is the production of a large elongated and ovoid sclerotium (Fig. 5.9) incorporating the infected ovary. The massed surface hyphae of sclerotia are impregnated with dark chemicals that protect the internal hyphae from desiccation and damage by sunlight. Sclerotia fall into the soil in the autumn and survive for long periods, just as seeds do. They often require a cold spell to induce germination. This helps to ensure that germination does not occur until the spring, when new hosts are available for infection. Upon germination they produce stalked structures with pinkish-violet globose heads, within which flask-shaped ascocarps are formed, their openings being visible as pits all over the heads (Plate 3). The ascospores are filamentous and after discharge are caught by the protruding stigmas of the grass flower, where they germinate and invade the ovary. The first part of the flower to be infected is the style and style base, where the fungus multiplies to form a dirty white structure containing internal folds, on the surface of which are produced the unicellular conidia given the anamorph name Sphacelia; these conidia are secreted in a drop of sugary liquid (the honeydew) and spread by visiting insects (Fig. 5.8). The rest of the ovary is infected by the fungus growing over its surface and invading from the base upwards, at the same time stimulating the ovary to grow very much larger, to many times the size of healthy seed. As the resulting ergot matures the surface hardens and darkens to a violet-black colour. The ergots protruding from the individual florets can easily be seen by the naturalist out for a walk before they are shaken free and fall to the ground.

FIG. 5.9

Ergots of Claviceps purpurea on meadow grass (Poa sp.) at Gullane, East Lothian, Scotland. (Debbie White, Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh.)

Ergot disease occurs very widely on grass species, but is particularly obvious in the large-flowered grasses that grow on the coast, such as sea lyme (Elymus arenarius) and marram (Ammophila arenaria). At one time the disease was commonly found in cereals, most frequently on rye (Secale cereale). It also occurred on barley, durum and Rivet wheat (Triticum turgidum) and some North American hard spring wheats, but was much less common on other wheats. One might guess that rye is particularly susceptible because, unlike other cereals, it is cross-pollinated and exposes the stigmas by opening the flowers for long periods.

There is evidence that Claviceps purpurea exists in a number of formae speciales, each of which attacks a particular group of grasses. Sometimes, however, the absence of cross-infection can be attributed to other causes; for example, the glumes of wheat (bracts enclosing the flowers) open to reveal the stigmata for a very short period each day, and if for reasons of local climate there is no discharge of the ascospores or Sphacelia spores are unavailable there will be no cross-infection.

Ergots have been used with varying success in folk medicine for several centuries, but began to be used with some degree of precision in orthodox medicine from the beginning of the nineteenth century. They contain a number of alkaloids based on lysergic acid. Indeed, LSD (d-lysergic acid diethylamide) itself was originally isolated from ergots. Alkaloids present in ergots and used for medicinal purposes include ergometrine and ergotamine, and the fungus is also rich in other substances, including histamine and ergosterol. In medicine ergots from rye are used for pharmaceutical preparations, and in eastern Europe and Russia the disease is deliberately ‘cultivated’ on a commercial scale. While there is no doubt that ergots from all sources contain pharmacologically active materials, the evidence for the strict comparability of ergots derived from different species is lacking. Nor do we know for certain whether any variation between the ergots from different grass species is due to differences in the fungus or differences in the grasses on which the fungus is growing.

Ergots for pharmaceutical use must be harvested at full maturity in dry weather, before the crop on which they are growing is ripe, and then stored in strictly dry conditions, since ergots that have been damp for any length of time lose their potency. Ergot extracts were originally used for two main purposes, hastening childbirth and controlling haemorrhage afterwards. There is no doubt that in skilled hands they were useful, but knowledge of the severe symptoms and death caused by accidentally eating ergots introduced a note of caution into their use and caused their replacement by other substances wherever possible. The pharmacological basis for their use lay in their effects on smooth muscle contraction and constriction of the smaller blood vessels. Ergometrine tartrate has been used in recent times to control excessive bleeding after childbirth. Ergotamine, which also acts as a vasoconstrictor, reducing the diameter of abnormally dilated blood vessels in the brain, has become a boon to migraine sufferers because it alleviates the pulsating headache that is a characteristic of the condition.

Ergots can cause the disease of ergotism if eaten accidentally but, although this has been recognised for many centuries and plausible accounts exist from about the tenth century, convincing circumstantial detail is only available from about the eighteenth century. Ergotism was not common in Britain but there is a case of ergotism recorded in England, in 1762, at Wattisham near Bury St Edmunds, where the family of a farm labourer was afflicted after eating bread made from discoloured grain of Rivet wheat. We have found no reports of it affecting humans in the USA, but there are numerous reports from mainland Europe, especially France and Germany.

The disease appeared there in two forms. ‘Gangrenous ergotism’ began with a vague lassitude and pains in the lumbar region or limbs, particularly in the calf muscle of the leg. This was followed by swelling in the feet or hands or in whole limbs, and a sensation of violent burning alternating with a feeling of icy cold. The burning sensation gave rise to an early name for the disease, ‘Ignis Sacer’. Later the name ‘St Anthony’s fire’ was coined after miraculous cures were experienced at the church of La Motte au Bois in France, where the bones of St Anthony were said to rest, and the monastic order of St Anthony became closely linked with the treatment of the disease. The stage of alternating heat and cold was followed by the shrivelling and gangrenous decay of the affected area, which might then be shed spontaneously. The disease was horrific. In the initial stages the burning sensations could be so intense as to cause the patients to leave their beds and seek relief in the open air, after which the icy cold caused them to seek relief by immersion in warm water, and a repeat of the cycle of misery. Although in mild cases only the finger nails or solitary fingers or toes would be shed, in severe cases whole limbs might be lost. If death did not intervene those afflicted might recover and live for many years, but if they ate more ergot they could exhibit symptoms for a second time.

‘Convulsive ergotism’ presented a very wide range of varying symptoms, but was distinguished from the gangrenous form by the absence of loss of appendages and limbs. A very common early symptom was a numbness of the extremities and the feeling, known as formication, that ants (some said mice!) were running about under and on the skin surface. This gave way to spasms of the limb muscles, which resulted in the fingers being contracted to give the appearance of an eagle’s beak and limbs being fixed with the thighs drawn forwards and the legs below the knee bent backwards, or the feet forwards and the toes backwards. There were similar contortions of the arms. These contractures often could not be overcome even by a strong man, although patients asked for this service and appeared to find relief when it was successfully offered. Other symptoms included convulsions, psychological problems, dementia, maniacal excitement and loss of sight. Patients could recover from mild attacks, but often died or were left with mental and physical impairment in severe attacks.

The two forms of ergotism were geographically separated by the River Rhine, the gangrenous form occurring in France and the convulsive form in Germany. Barger makes a convincing case for the gangrenous form being a direct result of the poisonous principles of ergots and for the convulsive form being due to an interaction between the ergot poison and vitamin A deficiency. The areas in both France and Germany where ergotism occurred were areas of extreme poverty where soil conditions favoured the growing of rye, a plant that survives in poor, acid and sandy conditions. In France, in Barger’s view, these were also areas where some dairy products were available, whereas in Germany the land was quite unsuitable for any form of dairying. Hence in Germany the people were susceptible to vitamin deficiency in near starvation conditions, the very conditions under which grains of dubious quality, including ergots, might be eaten.

Modern knowledge has all but eliminated ergotism in humans, but there was a mild outbreak in Britain in 1928 from rye grown in Yorkshire, and a more recent outbreak in France in 1951 has also been documented. In animals ergotism can cause loss of limbs and abortion, and in the USA the form of Claviceps attacking Paspalum spp. has particularly severe effects on cattle, sheep and horses.

THE HEAVY BRIGADE – THE SCLEROTINIACEAE

The Sclerotiniaceae, unusual in the order Leotiales (Table 1.1) in the development of resting sclerotia, are characterised by the production in the teleomorph stages of saucer-shaped ascocarps, the apothecia. These consist of disks of fungal tissue on the open surface of which asci are formed in great numbers, packed shoulder to shoulder with elongated supporting hyphae called paraphyses. In the Sclerotiniaceae the apothecia are usually stalked to raise the disks to the soil surface from the buried sclerotia that produce them (Fig. 5.4d).

Sclerotia are produced by the anamorph stage and are frequently quite large, being between 5 and 10 mm in diameter. Others are much smaller and yet others form a stroma, incorporating host tissue and extending as a thin plate in the leaf or stem. At first no connection was made between the various teleomorph and anamorph stages, but then Anton de Bary demonstrated that the very common Botrytis cinerea was the anamorph of an apothecial fungus which he named Sclerotinia fuckeliana. Botrytis cinerea, now Botryotinia fuckeliana, can be found in temperate climates if wild herbaceous vegetation is examined. When the plants are parted the beautiful conidiophores of the fungus will frequently be found on shaded leaf or stem tissue. It can also be seen in great masses on young plants (Plate 3), the dead stems of tomato plants at the end of the growing season or at the flower end of old cucumbers and courgettes (Cucurbita pipo) from where it may grow on to rot the whole fruit. In wine-producing areas it occurs on grapes at and after maturity and is the ‘noble rot’ that is said to remove the excess water from the grapes and concentrate the sugars to produce the shrivelled berries from which sweet dessert wines are made.

Botryotinia fuckeliana also parasitises the delicate tissues of the petals of roses (Fig. 5.10), sweet peas (Lathyrus odoratus) and other flowers, producing, after a spell of damp weather, circular bleached or darkened spots on the coloured background. These are infection sites derived from individual spores. To begin with the fungus is restricted to a limited area, but it grows out into the surrounding tissue as it ages. In roses it may spread from the outer petals into the whole bud, which then collapses as a wet mass. On strawberries and raspberries it forms restricted infection sites in the green tissue of the sepals and young berries, later spreading to the ripening tissues at maturity. With other related species such as Sclerotinia trifoliorum on clover (Trifolium spp.) and S. sclerotiorum on a range of horticultural crops, a similar pattern may be observed.

FIG. 5.10

Lesions of Botryotinia fuckeliana on senescent rose petals in Aberlady, East Lothian, Scotland. (D.S. Ingram.)

Taxonomy never stands still, and the simple relationship between Botrytis and Sclerotinia was soon modified to make a range of teleomorph genera and associated, widely varying, anamorphs. These are fascinating organisms, in many of which the pathogenic biology has still to be worked out. An attempt is made to summarise their morphology in Table 5.1, and other points of interest in Table 5.2.

TABLE 5.1

Some common genera of the Sclerotiniaceae.

| Teleomorph | Anamorph | Sclerotia or stromata formed |

|---|---|---|

| Botryotinia | Botrytis | Sclerotia |

| Ciboria | None known | Stromata in tissue |

| Ciborinia | None known | Stromata in tissue with black sclerotia at host surface |

| Gloeotinia | Endoconidium (pink and slimy) | Stromata as mummified grass seeds |

| Monilinia | ‘Monilia’ chains of conidia | Mummified infected pome and prune fruits become giant ‘sclerotia’ |

| Myriosclerotinia | Myrioconium | Black sclerotia |

| Ovulinia | Ovulitis | Black sclerotia |

| Sclerotinia | None known | Black sclerotia |

| Septotinia | Septotis | Stromata |

| Stromatinia | None known | Stromata in host tissues, black microsclerotia on surface |

TABLE 5.2

Some interesting members of the Sclerotiniaceae.

Not all sclerotial ascomycetes can be associated with apothecia. Sclerotium cepivorum, the cause of white rot of onions, produces sclerotia that resemble those of related species, but has not itself been associated with apothecia. It attacks onions, garlic (Allium sativum) and to a lesser extent leeks (A. ampeloprasum) in cooler climates. The first symptoms are yellowing and dieback. The roots and base of the growing bulb become covered with a white mycelium, and numerous small black sclerotia are formed within the scales. If the infection has not proceeded far at harvest the decay of the onion continues in storage. The disease can be devastating, and control is currently by soil treatments to kill off the sclerotia, with varying degrees of success, and by crop rotation, to avoid the fungus. However, the ability of the sclerotia to survive for at least ten years in the soil reduces the value of rotation as a control measure. Strenuous efforts have been made to find some means of biological control. The sclerotia are prevented from germinating in natural soil by a mycostasis (inhibition of growth) induced by the saprophytic soil flora, but this suspended animation is broken if the sclerotia are placed in pure water. It is also broken by the presence of onion roots in natural, unsterile soil. The stimulus can also be provided by the alkyl sulphides, chemicals that give onion and its relatives their distinctive flavour; these apparently have no direct effect on the mycostasis but enable the germinating sclerotia to tolerate it.

Other interesting fungi with an enclosing stromatic structure reminiscent of the Sclerotiniaceae are the Rhytismataceae, characterised by dark closed fruiting structures that form on leaves and stems. There they overwinter, breaking open in spring to display an apothecium disk bearing asci. The Rhytismataceae includes an interesting group of conifer pathogens, the needle cast fungi. One, Lophodermium pinastri, is mentioned in Chapter 7 as behaving as a latent pathogen in the green leaves of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris). After the leaves die and fall the ascocarps appear during the winter in dead plant material before opening as apothecia to release their spores in spring. L. seditiosum, formerly confused with this fungus, is a serious pathogen of Scots pine and apparently has only a limited latent period, actively killing leaves, on which it then fruits.

Also included here is the common tar spot fungus of sycamore leaves, Rhytisma acerinum (Fig. 5.11). The heavily pigmented, shiny, melanised lesions do not kill the infected leaves. However, following leaf fall in the autumn the fungus survives the winter on the dead tissues. In spring the lesions break open through convoluted lips (Fig. 5.12) to reveal a massive green disk-shaped apothecium. The spores from the asci in the disk are shot out and carried by wind to the young leaves, where each infection begins as a chlorotic area which becomes a tar spot. Associated with the maturing ascocarps is the production of minute spores called microconidia, which are believed to have a sexual function. In the days when coal was the main industrial and domestic fuel, sycamore trees in cities were free of tar spot disease, the pathogen being killed on the leaf surface by the sulphur pollutants from smoke. With the institution of clean air zones and a move away from coal as a fuel, tar spot has returned to city trees. In years when extended wet weather accompanies the period of spore discharge of this fungus, leaves become very heavily spotted and shrivel, making the trees unsightly and causing early leaf fall.

FIG. 5.11

Lesions of Rhytisma acerinum, cause of tar spot of sycamore (Acer pseudoplatanus) on a young tree in Thetford Forest, Norfolk, England. (D.S. Ingram.)

FIG. 5.12

Lesions of Rhytisma acerinum, cause of tar spot, on fallen, overwintered leaves of sycamore (Acer pseudoplatanus), opening to reveal the apothecia. (D.S. Ingram.)

IN SUMMARY

This broad survey of the pathogenic Ascomycota demonstrates how a group of fungi has broken its dependence on water by producing non-motile spores and achieving a close relationship with plants. Different species have adopted necrotrophic, hemibiotrophic and biotrophic modes of nutrition, enabling the group as a whole to occupy a wide range of ecological niches. Moreover, a wide range of growth strategies is deployed, including extensive biotrophic growth beneath the cuticle, destructive ramifications of necrotrophic hyphae through the tissues, and latency. Later we shall encounter yet more strategies in two specialised groups of Ascomycota: firstly those that have evolved to inhabit the vascular system of the host (Chapter 6); and secondly the powdery mildews (Chapter 8), biotrophs that live on the surface of the plant, tapping the living cells of the epidermis by means of complex haustoria.

The greatest number of organisms that cause plant disease are either members of the phylum Ascomycota or anamorphs related to them. And yet, of the 47 orders currently considered to make up the phylum, only about 15 include plant pathogenic species. Apart from a few specialised animal parasites the rest are saprophytes. Many of these are host delimited, however, being able to grow only on one particular dead host species. This leads us to ask if many of these species share with their pathogenic relatives the ability to establish a restricted infection in particular plant species, remaining poised until the death of the host from other causes, when they grow out as saprophytes in the dead tissue. Like necrotrophs they would then have an advantage in being able to colonise the senescent material in advance of competitors.

THE FREE SPIRITS: THE MITOSPORIC FUNGI

Throughout this chapter we have frequently referred to the anamorph stages of the various members of the Ascomycota described. In addition, there are vast numbers of other fungal anamorphs that have not yet been associated with a teleomorph; some possibly never will be. They are classified for convenience as the ‘Fungi imperfecti’ (sometimes Deuteromycetes or mitosporic fungi) with two sub-groups, the Hyphomycetes and the Coelomycetes.

Among the Hyphomycetes, which produce conidia on conidiophores arising direct from the hyphae, are the causal organisms of a number of well-known plant diseases – Fusarium oxysporum and Verticillium albo-atrum, for example, are among the most important plant pathogens known (see Chapter 6). Other well-known disease organisms in this group are the Alternaria spp.: A. brassicae and A. brassicicola, for example, cause leaf spots on brassicas, and A. solani causes early blight of potato and tomato, destroying large areas of the infected leaves. These fungi are recognised by their dark, pear-shaped, multi-celled conidia, often arranged in chains. Ramularia pratensis and R. rubella cause characteristic purple-edged spots on the leaves of sorrels and docks (Rumex spp.) (Fig. 5.13), with the white conidia being produced on the lower surfaces of the lesions.

FIG. 5.13

Lesions of Ramularia sp. on a leaf of dock (Rumex sp.) near Temple, Midlothian, Scotland. (D.S. Ingram.)

FIG. 5.14

A lesion of Phyllosticta hedericola on ivy (Hedera sp.) in Edinburgh, Scotland. (D.S. Ingram.)

Members of the Coelomycetes, in contrast, form their conidia in pycnidia or acervuli. The pycnidia are dark-walled structures embedded in the host tissue. They are nearly spherical, with a domed cap at the leaf surface; the conidia are released through a central pore. The acervuli are mats of fungal hyphae on which conidia are borne in a mass, initially within the host tissue.

Pycnidial genera include Phoma and Septoria, necrotrophic leaf-spotting pathogens of a great many plant species. The conidia are single-celled in Phoma and elongated with septa in Septoria. Familiar pathogenic species are P. exigua, which infects potato, its f.sp. foveata causing destructive lesions on tubers in store, and S. apiicola, which causes a seed-borne blight of celery (Apium graveolens). Sometimes the leaf spots show concentric rings of necrotic tissue, as with Coniothyrium hellebori on Christmas rose (Helleborus spp.) (Plate 3) and Phyllosticta hedericola on ivy (Hedera spp.) (Fig. 5.14). Such lesions are often called target spots and are useful for diagnostic purposes but the mechanism for their production is not fully understood. Observations to determine whether the zones are related to periods of light or darkness, temperature changes or an interaction between the pathogen and host might be very rewarding. Where pycnidial species have been linked to teleomorphs the genera of the Ascomycota involved have included Mycosphaerella, Didymella and Leptosphaeria.

Acervular forms include the pathogenic genus Colletotrichum. This produces sunken sharply defined lesions on leaves and pods, referred to as anthracnose. This symptom is well seen with C. lindemuthianum, cause of anthracnose of French bean and other phaseolus beans. The lesions on pods spread to infect the seeds, which then become the main source of infection from one generation of the host to another.

Although the taxonomy of the Hyphomycetes and Coelomycetes has been well studied, the biology of the diseases they cause, especially on wild plants, has not, and there is an open field of investigation here for the amateur naturalist.