Hősök Tere és Városliget

Museum of Fine Arts (Szépművészeti Múzeum)

Vajdahunyad Castle (Vajdahunyad Vára)

Széchenyi Baths (Széchenyi Fürdő)

Attractions Behind Széchenyi Baths

The grand finale of Andrássy út, at the edge of the city center, is also one of Budapest’s most entertaining quarters. Here you’ll find the grand Heroes’ Square, dripping with history (both monumental and recent); the vast tree-filled expanse of City Park, dressed up with fanciful buildings that include a replica Transylvanian castle and an Art Nouveau zoo; and, tucked in the middle of it all, Budapest’s finest thermal spa and single best experience, the Széchenyi Baths. If the sightseeing grind gets you down, take a mini-vacation from your busy vacation and relax the way Budapesters do: Escape to City Park.

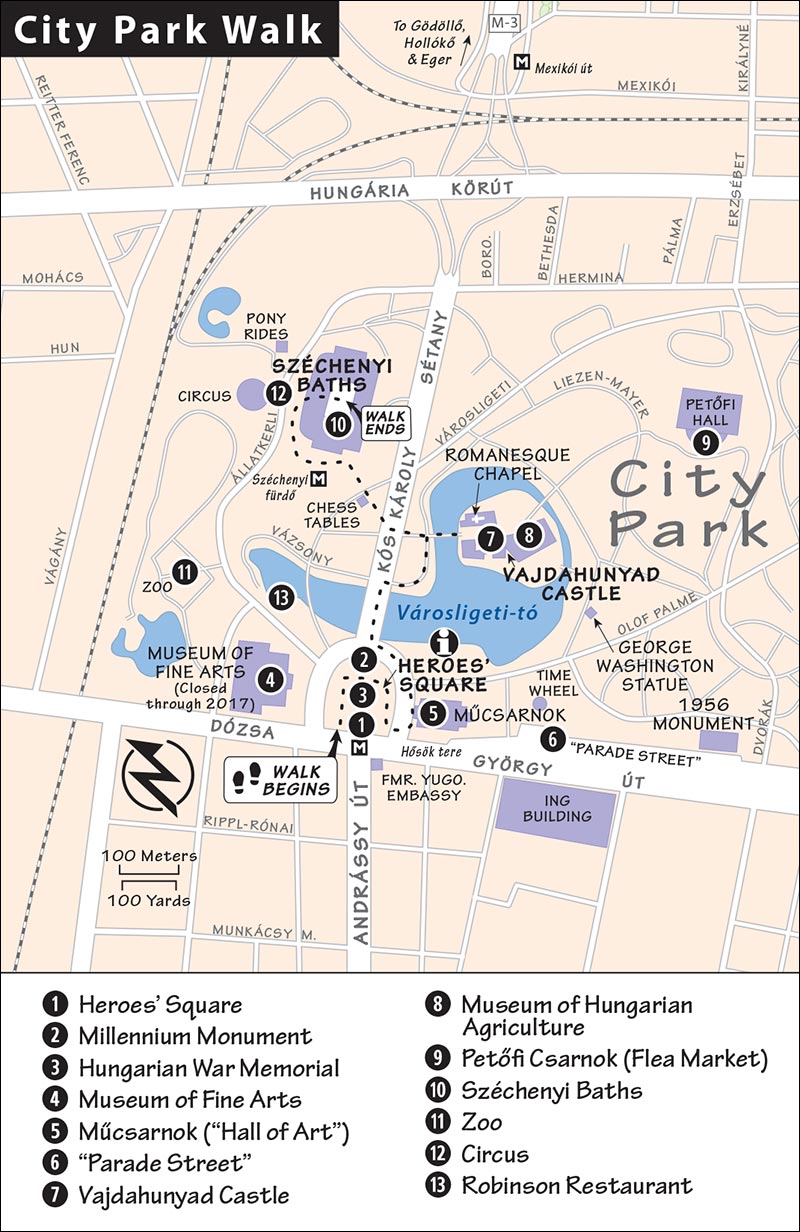

(See "City Park Walk" map, here.)

Construction Alert: The city has embarked on ambitious plans to build a new “Museum Quarter” in the corner of the City Park along Dózsa György út (a.k.a. “Parade Street,” near today’s 1956 Monument). Eventually this will consolidate several far-flung museum collections, including the National Gallery and museums of contemporary art (Ludwig collection), ethnography, photography, architecture, and music. The historic building of the Hungarian Technical and Transportation Museum—sloppily rebuilt after World War II as a shadow of its former self—may also be rebuilt. The plans also include a complete redevelopment of the park itself. As work will likely be ongoing through at least 2018, you may find part of this area torn up. For the latest updates, see www.ligetbudapest.org.

Length of This Walk: One hour, not including museum visits or the baths.

What to Bring: If taking a dip in the Széchenyi Baths, bring your swimsuit and a towel from your hotel (or rent these items there). You may also want to bring flip-flops, sunscreen, and soap and shampoo to shower afterward.

Museum of Fine Arts: Likely closed for renovation through 2017; if open likely 1,800 Ft, audioguide-500 Ft, Tue-Sun 10:00-17:30, closed Mon, last entry 30 minutes before closing, Dózsa György út 41, tel. 1/469-7100, www.szepmuveszeti.hu.

Műcsarnok (“Hall of Art”): 1,800 Ft, Tue-Wed and Fri-Sun 10:00-18:00, Thu 12:00-20:00, closed Mon, Dózsa György út 37, tel. 1/460-7000, www.mucsarnok.hu.

Museum of Hungarian Agriculture (in Vajdahunyad Castle): 1,100 Ft; April-Oct Tue-Sun 10:00-17:00; Nov-March Tue-Fri 10:00-16:00, Sat-Sun 10:00-17:00, closed Mon year-round, last entry 30 minutes before closing; tel. 1/363-1117, www.mezogazdasagimuzeum.hu.

Széchenyi Baths: 4,500 Ft for locker (in gender-segregated locker room), 500 Ft more for personal changing cabin, 200 Ft more on weekends, cheaper after 19:00; admission includes outdoor swimming pool area, indoor thermal baths, and sauna; swimming pool generally open daily 6:00-22:00, thermal baths and sauna daily 6:00-19:00, may be open later on summer weekends, last entry one hour before closing, Állatkerti körút 11, district XIV, tel. 1/363-3210, www.szechenyibath.hu.

Starring: A lineup of looming Hungarian greats, a faux-Transylvanian castle, Budapest’s best baths, and the city’s most enticing green patch.

Nearby Eateries: For restaurants in City Park, see here.

(See "City Park Walk" map, here.)

• Stand in the middle of...

Like much of Budapest, this Who’s Who of Hungarian history at the end of Andrássy út was commissioned to celebrate the country’s 1,000th birthday in 1896 (see here). Ironically, it wasn’t finished until 1929—well after Hungary had lost World War I and two-thirds of its historical territory, and was facing its darkest hour. Today, more than just the hottest place in town for skateboarding, this is the site of several museums and the gateway to City Park.

• The giant colonnades and tall column that dominate the square make up the...

Step right up to meet the world’s most historic Hungarians (who look to me like their language sounds). Take a moment to explore this monument, which offers a step-by-step lesson in the story of the Hungarians. (Or, to skip the history lesson, you can turn to “Museum of Fine Arts” on here.)

The granddaddy of all Magyars, Árpád stands proudly at the bottom of the pillar, peering down Andrássy út. He’s surrounded by six other chieftains; altogether, seven Magyar tribes first arrived in the Carpathian Basin (today’s Hungary) in the year 896. Remember that these ancestors of today’s Hungarians were from Central Asia and barely resembled the romanticized, more European-looking figures you see here. (Only one detail of these statues is authentically Hungarian: the bushy moustaches.) Magyar horsemen were known and feared for their speed: They rode sleek Mongolian horses (rather than the powerful beasts shown here), and their use of stirrups—revolutionary in Europe at the time—allowed them to ride fast and turn on a dime in order to quickly overrun their battlefield opponents. Bows and spears were their weapons of choice; they’d have had little interest in the chain mail and heavy clubs and battle axes that Romantic sculptors gave them. They used these skills to run roughshod over the Continent, laying waste to Europe.

The 118-foot-tall pillar supports the archangel Gabriel as he offers the crown to Árpád’s great-great-grandson, István (as we’ll learn, he accepted it and Christianized the Magyars).

In front of the pillar is the Hungarian War Memorial (fenced in to keep skateboarders from enjoying its perfect slope).

The sculptures on the top corners of the two colonnades represent, in order from left to right: Work and Welfare, War, Peace, and the Importance of Packing Light.

Each statue in the two colonnades represents a great Hungarian leader, with a relief below showing a defining moment in his life. Likewise, each one represents a trait or trend in the colorful story of this dynamic people. (For all the details, see the Hungary: Past and Present chapter.)

• Behind the pillar, look to the...

The first colonnade features rulers from the early glory days of Hungary.

After decades of terrorizing Europe, the Magyars were finally defeated at the Battle of Augsburg in 955. King Géza realized that unless they could learn to get along with their neighbors, the Magyars’ military might only garner them short-term prosperity. Géza decided to baptize his son, Vajk, gave him the Christian name István (Stephen), and married him off to a Bavarian princess. On Christmas Day in the year 1000, commissioners of the pope (pictured in the relief below) brought to István the same crown that still sits under the Parliament dome. To historians, this event marks the beginning of the Christian—and therefore European—chapter of Magyar history. (For more on István, see here.)

Known as Ladislas in English, László was a powerful knight/king who carried the Christian torch first taken up by his cousin István. Joining the drive of his fellow European Christian leaders, he led troops into battle to expand his territory into today’s Croatia. Don’t let the dainty chain-mail skirt fool you...that axe ain’t for chopping wood. In the relief below, see László swing the axe against a pagan soldier who had taken Christian women hostage. László won a chunk of Croatia, then lost it...but was sainted anyway (hence the halo). László’s story is the first of many we’ll hear about territorial expansion and loss—a crucial issue to Hungarian leaders across the centuries (and even today).

Kálmán (Coloman) traded his uncle László’s bloody axe for a stack of books. Known as “the Book Lover,” Kálmán was enlightened before his time, acclaimed as being the most educated king of his era. He was the first European ruler to prohibit the trial or burning of women as witches (on the relief, see him intervening to save the cowering woman in the bottom-right corner). He was also the king who retook Croatia yet again, bringing it into the Hungarian sphere of influence through the early 20th century. Kálmán reminds us that the Hungarians pride themselves on being a highly intellectual people, as demonstrated by the many scientists, economists, and other great minds they’ve produced. (As you walk through City Park in a few minutes, keep an eye out for chess players.)

András (Andrew) II is associated with the golden charter he holds in his hand (with the golden medallion dangling from it)—the Golden Bull of 1222. This decree granted some measure of power to the nobility, releasing the king’s stranglehold and acknowledging that his power was not absolute. This was the trend across Europe at the time (the Magna Carta, a similarly important document, was signed in 1215 by England’s King John). András demonstrates the importance Hungarians place on self-determination: Like many small Central European nations, Hungary has often been dominated by a foreign power...but has always shown an uncrushable willingness to fight back. (We’ll meet some modern-day Hungarian freedom fighters shortly.) It’s no surprise that so many place names in Hungary include the word Szabadság (“Liberty”). The relief shows that the Hungarians are willing to fight for this ideal for others, as well: András is called “The Jerosolimitan” for his success in the Fifth Crusade, in which his army liberated Jerusalem. Here he is depicted alongside the pope kissing the rescued “true cross.”

Despite his achievements, András is far less remembered today than his daughter Elisabeth (1207-1231, not depicted here), who was sent away to Germany for a politically expedient marriage. She is the subject of an often-told legend: The pious, kindly Elisabeth was known to sneak scraps of food out of the house to give to poor people on the street. One evening, her cruel confessor saw her leaving the house and stopped her. Seeing her full apron (which was loaded with bread for the poor), he demanded to know what she was carrying. “Roses,” she replied. “Show me,” he growled. Elisabeth opened her apron, the bread was gone, and rose petals miraculously cascaded out onto the floor. In her short life, Elisabeth went on to found hospitals and carry out other charitable acts, and (unlike her father) became a saint. Elisabeth remains a popular symbol of charity not only in Hungary, but also in Germany. (It’s easy to confuse St. Elisabeth with the equally adored Empress Elisabeth, a.k.a. Sisi, the Habsburg monarch, described on here.)

Having governed over one of the most challenging periods of Hungarian history, the defiant-looking Béla—St. Elisabeth’s brother—is celebrated as the “Second Founder of the Country” (after István). Béla led Hungary when the Tatars swept in from Central Asia, devastating Buda, most of Hungary, and a vast swath of Central and Eastern Europe. Because his predecessors had squandered away Hungary’s holdings, Béla found himself defenseless against the onslaught. In the relief, we see Béla surveying the destruction left by the Tatars. Béla made a deal with God to send his daughter Margaret to a nunnery (on the island that would someday bear her name—see here) in exchange for sparing Hungary from complete destruction. After the Tatars left, he rebuilt his ruined nation. It was Béla who moved Buda to its strategic location atop Castle Hill and built a wall around it, to be better prepared for any future invasion. This was the first of many times that Budapest (and Hungary) was devastated by invaders; later came the Ottomans, the Nazis, and the Soviets. But each time, like Béla, the resilient Hungarian people rolled up their sleeves to rebuild.

Everyone we’ve met so far was a member of the Árpád dynasty—descendants of the tough guys at the base of the big column. But when that line died out in 1301, the Hungarian throne was left vacant. The Hungarian nobility turned to “Charles Robert,” a Naples-born prince from the French Anjou (or Angevin) dynasty, which had married into Hungarian royalty. (His shield combines the red-and-white stripes of Hungary with the fleur-de-lis of France.) The Hungarians were slow to accept Robert—he had to be crowned four different times to convince everybody, and he was actually banned from Buda. (He built his own palace, which still stands, at Visegrád up the Danube—see here.) Eventually he managed to win them over and stabilize the country, even capturing new lands for Hungary (see the relief). Károly Róbert represents the many Hungarian people who are not fully, or even partially, Magyar. Today’s Hungarians are a cultural cocktail of the various peoples—German, Slavic, Jewish, Roma (Gypsy), and many others—that have lived here and been “Magyarized” to adopt Hungarian language, culture, and names.

“Louis the Great” built on his father Károly Róbert’s successes and presided over the high-water mark of Hungarian history. He expanded Hungarian territory to its historical maximum—including parts of today’s Dalmatia (Croatia), Bulgaria, and Bosnia-Herzegovina—and even attempted to retake his father’s native Naples (pictured in the relief). Hungarians still look back with great pride on these days more than six centuries ago, when they were a vast and mighty kingdom.

• Now turn your attention to the...

The gap between the colonnades coincides with some dark times for the Hungarians. The invading Ottomans swept up the Balkan Peninsula from today’s Turkey, creeping deeper and deeper into Hungarian territory...eventually even taking over Buda and Pest for a century and a half. Hungarian nobility retreated to the farthest corners of their lands, today’s Slovakia and Transylvania, and soldiered on.

A military hero who achieved rare success fighting the Ottomans, Hunyadi won the fiercest-fought skirmish of the era, the Battle of Belgrade (Nándorfehérvár in Hungarian). The relief depicts a particularly violent encounter in that battle. (The guy holding the cross is János Kapisztran, a.k.a. St. John Capistrano, an Italian friar and Hunyadi’s right-hand man.) This victory halted the Ottomans’ advance into Hungary for decades. Owing largely to his military prowess, Hunyadi was extremely popular among the people and became wealthier than even the king. He led Hungary for a time as regent, when the preschool-age king was too young to rule. After he died of the plague, Hunyadi’s reputation allowed his son Mátyás to step up as ruler....

Perhaps the most beloved of all Hungarian rulers, Mátyás (Matthias) Corvinus was a Renaissance king who revolutionized the monarchy. He was a clever military tactician and a champion of the downtrodden, known among commoners as “the people’s king.” The long hair and laurel wreath (instead of a crown) attest to his knowledge and enlightenment. And most importantly, he was the first (and last) Hungarian-blooded king from the death of the Árpád dynasty in 1301 until today. Building on his father’s military success against the Ottomans, Matthias achieved a diplomatic peace with them—allowing him to actually expand his territory while other kings of this era were losing it. (He even had time for some vanity building projects—the relief shows him appreciating a model of his namesake church, which still stands atop Castle Hill.) Matthias’ death represented the death of Hungarian sovereignty. After him, Hungary was quickly swallowed up by the Ottomans, then the Habsburgs. For more on King Matthias, see here.

Appropriately, Matthias is the final head of state at Heroes’ Square. Reflecting the sea change after his death, the rest of the heroes here are freedom-fighters who rallied against Habsburg influence.

After Matthias, the Ottomans took over most of Hungary. Transylvania, the eastern fringe of the realm, was fragmented and in a state of ever-fluctuating semi-independence—sometimes under the firm control of sovereign princes, at other times controlled by the Ottomans. The three Hungarian dukes depicted here helped to unify their people through this difficult spell (see the reliefs): Bocskai and Thököly found rare success on the battlefield against the Habsburgs, while Bethlen made peace with the Czechs and united with them to fight against the Habsburgs.

The next two statues are of Ferenc Rákóczi and Lajos Kossuth, arguably the greatest Hungarian heroes of the Habsburg era and the namesakes of streets and squares throughout the country.

Although he was a wealthy aristocrat educated in Vienna, Rákóczi (Thököly’s stepson) resented Habsburg rule over Hungary. When his countrymen mobilized into a ragtag peasant army to stage a War of Independence (1703-1711), Rákóczi reluctantly took charge. (The relief depicts an unpleasant moment in Rákóczi’s life, when he realizes just how miserable his army will be.) Allied with the French (who were trying to wrest power from the Habsburgs’ western territory, Spain), Rákóczi mounted an attack that caught the Habsburgs off-guard. Moving west from his home region of Transylvania, Rákóczi succeeded in reclaiming Hungary all the way to the Danube. But the tide turned when, during a pivotal battle, Rákóczi fell from his horse and was presumed dead by his army. His officers retreated and appealed to the Habsburgs for mercy, effectively ending the revolution. Rákóczi left Hungary in disgrace and rattled around Europe—to like-minded Habsburg enemies Poland, France, and the Ottoman Empire—in a desperate attempt to gain diplomatic support for a free Hungary. He died in exile in a small Turkish town, but his persistence still inspires Hungarians today.

Kossuth was a nobleman and parliamentarian known for his rebellious spirit. When the winds of change swept across Europe in 1848, the Hungarians began to murmur once again about more independence from the Habsburgs—and Kossuth emerged as the movement’s leader (in the relief, he’s calling his countrymen to arms). After a bitterly fought revolution, Habsburg Emperor Franz Josef enlisted the help of the Russian czar to put down the Hungarian uprising, shattering Kossuth’s dream. (For more on the 1848 Revolution, see here.) Kossuth went into exile and traveled the world, tirelessly lobbying foreign governments to support Hungary’s bid for independence. He even made his pitch to the US Congress...and today, a bust of Kossuth is one of only three sculptures depicting non-Americans in the US Capitol. After Kossuth died in exile in 1894, his body was returned to Budapest for an elaborate three-day funeral. The Habsburg Emperor Franz Josef—who knew how to hold a grudge—refused to declare the former revolutionary’s death a national holiday, so Catholic church bells did not toll...but Protestant ones did.

The less-than-cheerful ending to this survey of Hungarian history is fitting. Hungarians tend to have a pessimistic view of their past...not to mention their present and future. In the Hungarian psyche, life is a constant struggle, and you get points just for playing your heart out, even if you don’t win.

• Two fine museums flank Heroes’ Square. As you face the Millennium Monument, to your left is the...

This giant collection of mostly European art—likely closed for renovation through 2017—is the underachieving cousin of the famous Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. Like that collection, it’s strong in art from areas in the Habsburgs’ cultural orbit: Germanic countries, the Low Countries, and especially Spain. (For the best Hungarian art, head for the National Gallery on Castle Hill—see here.) The collection belonged to the noble Eszterházy family, and was later bought and expanded by the Hungarian government.

If you enjoy European art (particularly Spanish Golden Age), consider visiting this museum. After buying your ticket, grab a floor plan and head up the stairs on the right, go to the end of the hall and through the door on the right, and do a clockwise spin through the good stuff: German and Austrian (including some works by Albrecht Dürer); early Dutch and Flemish (including paintings by both Brueghels); and finally Spanish. The Spanish collection features works by Murillo, Zubarán, and Velázquez, along with five El Grecos and several Goyas, including The Water Carrier.

• Across Heroes’ Square (to the right as you face the Millennium Monument) is the...

Used for cutting-edge contemporary art exhibits, the Műcsarnok (comparable to a German “Kunsthalle”) has five or six temporary exhibits each year. While art lovers enjoy this place, it’s more difficult to appreciate than some other Budapest museums.

The Műcsarnok was also the site of a major event in recent history. On June 16, 1989, several anti-communist heroes who had been executed by the regime were finally given a proper funeral on the steps of this building. The Műcsarnok was draped in black-and-white banners, and in front were four actual coffins (including one with the recently exhumed remains of reformist hero Imre Nagy—see here), and a fifth, empty coffin to honor others who were lost. One of the most memorable speakers from that occasion was a 25-year-old, shaggy-haired burgeoning politician named Viktor Orbán—who now leads the right-of-center Fidesz Party that’s attempting to reshape modern Hungary. The Yugoslav Embassy, which was in the building across the busy ring road from Heroes’ Square (on the left-hand corner), was the last place Imre Nagy was seen alive in public.

The area along the busy street beyond the Műcsarnok was once used for communist parades. While the original communist monuments are long gone, two new monuments have replaced them. You’ll also likely see lots of construction in this zone (which may impede your access to these monuments). They’re working on turning this corner of City Park into a state-of-the-art campus of museums, in order to consolidate several small collections that are currently scattered around the city (for details, see “Construction Alert,” earlier).

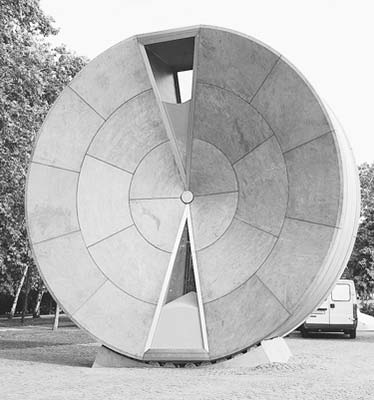

As you walk behind the Műcsarnok, first you’ll see the giant, circular Time Wheel (Időkerék). Notice the sand inside the circle, which acts like a giant hourglass. Unveiled with much fanfare when Hungary joined the European Union on May 1, 2004, the wheel is manually rotated 180 degrees to restart the hourglass every year. Unfortunately, unexpected condensation has gummed up the mechanism (hardly an auspicious kickoff for Hungary’s EU membership). While most Budapesters laugh it off as an eyesore, it’s cheaper to leave it here than to tear it down. We’ll see if it survives the latest round of redevelopment.

Across the street, notice the shiny, undulating ING Bank Headquarters. ING has invested heavily in Budapest in recent years, building both this and the shiny glass mall on Vörösmarty tér.

Continuing along the parking lot, you’ll soon see the impressive 1956 Monument, celebrating the historic uprising against the communists (see here). During the early days of the Soviet regime, this was the site of a giant monument to Josef Stalin that towered 80 feet high (Stalin himself was more than 25 feet tall). While dignitaries stood on a platform at Stalin’s feet, military parades would march past. From the inauguration of the monument in 1951, the Hungarians saw it as a hated symbol of an unwanted regime. When the 1956 Uprising broke out, the removal of the monument was high on the protesters’ list of 16 demands. On the night the uprising began, October 23, some rebels decided to check this item off early. They came here, cut off Stalin just below the knees, and toppled him from his platform. (Memento Park has a reconstruction of the original monument’s base, including Stalin’s boots—see here.) The current monument was erected in 2006 to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the uprising. Symbolizing the way Hungarians came together to attempt the impossible, it begins with scattered individuals at the back (rusty and humble), gradually coming together and gaining strength and unity near the front—culminating in a silver ship’s prow boldly plying the ground. To fully appreciate the monument, walk up the middle of it from the back to the front. Think about how comforting it is to realize you’re not alone, as others like you gradually get closer and closer.

• Head back to the Műcsarnok at Heroes’ Square. The safest way to reach City Park is to begin in front of the Műcsarnok, then use the crosswalk to circle around across the street from the Millennium Monument to reach the bridge directly behind it. (There’s no crosswalk from the monument directly to the bridge.)

Begin walking over the bridge into...

Budapest’s not-so-central “Central Park” was the private hunting ground of wealthy aristocrats until the mid-19th century, when it was opened to the public. Soon after, it became the site of the overblown 1896 Millennium Exhibition, celebrating Hungary’s 1,000th birthday. It’s still packed with huge party decorations from that bash: a zoo with quirky Art Nouveau buildings, a replica of a Transylvanian castle, a massive bath/swimming complex, walking paths, and an amusement park. City Park is also filled with unwinding locals.

Orient yourself from the bridge: The huge Vajdahunyad Castle is across the bridge and on your right. Straight into the park and on the left are the big copper domes of the fun, relaxing Széchenyi Baths. And the zoo is on the left, beyond the lake and the recommended waterfront Robinson restaurant. Near the zoo (not quite visible from here) is the world-famous Gundel restaurant, where visiting bigwigs have dined—though it was recently bought out by an international hotel chain and has gone downhill.

The area in front of the castle seems to shift constantly: It’s generally used as a paddleboat pond in summer and a skating rink in winter, but it can also be drained to create a festival ground at any time.

• Cross the bridge, take the immediate right turn, and follow the path to the entrance of...

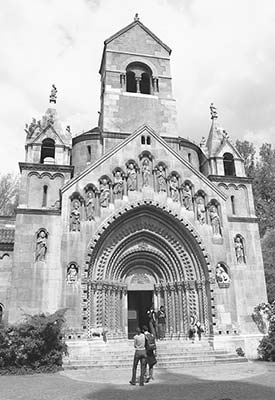

Many of the buildings for Hungary’s Millennial National Exhibition were erected with temporary materials, to be torn down at the end of the festival—as was the case for most world fairs at the time. But locals so loved Vajdahunyad Castle that they insisted it stay, so it was rebuilt in brick and stone. The complex actually has four parts, each representing a high point in Hungarian architectural style: Romanesque chapel, Gothic gate, Renaissance castle, and Baroque palace (free and always open to walk around the grounds).

From this direction, the Renaissance castle dominates the view. It’s a replica of a famous castle in Transylvania that once belonged to the Hunyadi family (János and Mátyás Corvinus—both of whom we met back on Heroes’ Square).

Cross over the bridge and through the Gothic gateway. Once inside the complex, on the left is a replica of a 13th-century Romanesque Benedictine chapel. Consecrated as an actual church, this is Budapest’s most popular spot for weddings on summer weekends. Farther ahead on the right is a big Baroque mansion housing the Museum of Hungarian Agriculture (Magyar Mezőgazdasági Múzeum). It brags that it’s Europe’s biggest agriculture museum, but most visitors will find the lavish interior more interesting than the exhibits.

Facing the museum entry is a monument to Anonymous—specifically, the Anonymous from the court of King Béla IV who penned the first Hungarian history in the Middle Ages.

For an optional detour to yet another monument (of György—er, George—Washington), consider going for a walk in the park. Continue across the bridge at the far end of Vajdahunyad Castle, then turn right along the main path. George Washington (funded by Central European immigrants to the US) is about five minutes down, on the left-hand side.

Deeper in the park is the giant Petőfi Csarnok, which is used for big rock concerts (tel. 1/363-3730, www.petoficsarnok.hu) as well as a weekend flea market (see here).

• Time for some fun. Head back out to the busy main road, and cross it. Under the trees, you’ll pass some red outdoor tables where you’ll likely see elderly locals playing chess. Beyond the tables and a bit to the right, the pretty gardens and copper dome mark the famous...

Budapest’s best thermal baths, and (for me) its single best experience, period, the Széchenyi Baths offer a refreshing and culturally enlightening Hungarian experience. Reward yourself with a soak.  For all the details, see the Thermal Baths chapter.

For all the details, see the Thermal Baths chapter.

• The best entrance to the baths is around the back side. That’s also where you’ll find...

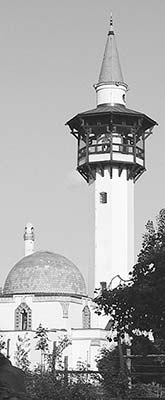

Lining the street behind the baths are two kid-friendly attractions. From the steps of the swimming pool entrance, look through the fence across the street to see the zoo’s colorful Art Nouveau elephant house (pictured at left), slathered with Zsolnay tiles outside and mosaics inside. The zoo was recently expanded to take over the adjacent amusement park; they incorporated some of the most popular rides into the zoo itself. To the right is Budapest’s 120-year-old circus (marked Nagycirkusz). For more details on these attractions, see the Budapest with Children chapter.

• Our walk is over. Your options are endless. Soak in the bath, visit the zoo, rent a rowboat, buy some cotton candy...enjoy City Park any way you like.

If you’re ready for some food, cheap snack stands are scattered around the park; for something fancier, consider the recommended Robinson restaurant (see here).

When you’re ready to head home, the M1/yellow Metró line (with effortless connections to the House of Terror, Opera, the Metró hub of Deák tér, or Vörösmarty tér in downtown Pest) has two handy stops here: The entrance to the Széchenyi fürdő stop is at the southwest corner of the yellow bath complex (easy to miss—to the left and a bit around the side as you face the main entry, just a stairway in the middle of the park); and the Hősök tere stop is back across the street from Heroes’ Square, where we began this walk.