Worksheets: Your Thinking Sheets

This appendix is meant both as a summary of the design process described in this book and as a checklist of the recommended steps toward creating an integrated conceptual water harvesting design.

Teachers may find these worksheets useful for teaching integrated water harvesting in their classrooms. Note that additional water-harvesting curriculum (designed to be used in conjunction with this book) is available at HarvestingRainwater.com. Once there, search “curriculum.”

This appendix follows the thought-flow in volume 1 of Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and Beyond. The result will begin with basic observations about your land and lead to steps you can take to have a more water-and life-abundant home and yard—one more comfortable and beautiful in both winter and summer.

STEP 1/CHAPTER 2: ASSESSING YOUR SITE’S WATER RESOURCES AND MORE

A. Walk your site’s watershed.

Identify its ridgelines/boundaries, and observe how water flows within them. Make any notes below. Refer to Watersheds and Subwatersheds—Determining Your Piece of the Hydrologic Cycle for more information.

If runoff flows across your land, pay particular attention to what direction it comes from, its volume, and the force of the water’s flow. Look at what surfaces water flows over to estimate the water’s quality. Note any observations below. You may also want to look for erosion patterns when it’s dry (see appendix 1). Write down your observations.

B. Create a site plan and map your observations.

First, photograph your site so you’ll have “before” photos with which to document your progress with future “after” photos. You may want to include copies of these photos with these worksheets.

Now, use grid paper or an aerial photo of your site from Google Earth or Google Maps, and using figure 2.3 as a model create a “to-scale” site plan of your property’s boundaries. Leave wide margins to mark the locations where resources—such as runoff from your neighbor’s yard—flow on, off, or along-side your site. Draw or identify buildings, driveways, patios, existing vegetation, natural waterways, underground and above-ground utility lines, etc. to scale. Next, draw any catchment surfaces that drain water off your site (for example, a driveway sloping toward the street), and any catchment surfaces draining water onto your site from off-site; indicate the direction and flow of any runoff and runon water. Refer to figure 2.2 and figure 2.4 as you do all this. Write down additional notes below.

Additional observations you may want to record at this time:

What vegetation lives solely off on-site water (rainwater), and which depends on pumped water or imported irrigation water? __________

What unirrigated native vegetation do you see growing within a 25-mile (40-km) radius of your site (in similar microclimates as those that exist on your site) that could do well on your site? __________

C. Calculate your site’s rainwater resources.

C1. Your Site’s Rain “Income”

Determine the “income” side of your site’s water budget so you can compare them with the “expense” side. For this section refer to pages Calculate Your Site’s Rainfall Volume and additional calculations found in appendix 3.

• What is the area’s average annual precipitation in inches or mm? __________

• What is the area of your site (land) in square feet, acres, or hectares? __________

• What is the area of the roofs of your house, garage, sheds, and other buildings on your property (see the calculations appendix 3, equations 1–3)? __________, __________, __________

Now, use the calculations in box 2.3, or in appendix 3, to determine your site’s rainfall resources. You will want to answer the question: In an average year, how much rain falls on your site? For this you will use your site’s area and annual precipitation to get some kind of ballpark figures about your annual rainwater resources in gallons or liters. If you have a difficult time with the math, then just use the “rule of thumb” figures in box A3.2 of appendix 3.

Do your calculations below.

X. Your site’s annual rainfall resources in gallons or liters. How much water falls onto your site?

X = __________

C2. Your Site’s Rain “Loss”

Now, refer to the calculations in box 2.4 and figure 2.4 to determine how much runoff drains from your impervious catchment surfaces for potential storage/use in adjoining tanks or earthworks. You don’t need to be exact; you just want a good estimation.

Roof runoff __________

Driveway runoff __________

Patio runoff __________

__________ runoff __________

Then note how much of that runoff (and additional potential runoff from other built or disturbed surfaces such as mounded sections of the landscape or bare dirt areas) currently drains off your property. Add the estimated total and write it below:

Y. Loss/runoff from your site in gallons or liters. How much runoff runs off your site?

Y = __________

C3. Your Site’s Water Gain

Now, you want to estimate how much water (annually) you’re gaining from runoff from other properties onto your site. Use the same calculations as above.

Z. Gain/runon in gallons or liters. How much off-site runoff runs onto your site? (Use the same calculations as above.)

Z = _______

C4. Totaling It Up

X (on-site rainfall) - Y (runoff draining off site) + Z (runon to your site) = T (TOTAL: HOW MUCH YOU CURRENTLY DO HARVEST)

X __________ - Y __________ + Z __________ = T __________

T = __________

This equals the total on-site rainwater resources you currently do harvest.

D. Estimate your site’s water needs.

This step determines the “expense” side of your water budget by estimating your household and landscape water needs. See Estimate Your Site’s Water Needs.

•What is your annual water consumption based on your water bill? __________

•In which months are your water consumption/ needs highest? __________

The next steps are to try to determine how much of your water is used indoors versus outdoors.

•Estimate your average annual indoorwater consumption using the user-friendly website h2ouse.org. __________

•Estimate your average annual outdoorwater consumption (based on plant water-need requirements; see appendix 4): List some of your larger plants and their water requirements below.

•Or/And: Subtract your estimated indoor water consumption from your water bill for a ballpark estimate of your current outdoor needs. __________

E. Compare your needs and resources.

•How much of your domestic water needs could you meet by harvesting rooftop runoff in one or more tanks? __________

•How much vegetation could you support by simply harvesting rain falling and infiltrating directly in your soil? __________

•How much vegetation could you support if onsite runoff was also directed to the planted areas (this runoff could be diverted directly and passively to planted areas or harvested in a tank and doled out to the planted areas as needed)? _________

•List what other steps you could take to balance your water budget using harvested rainwater as your primary water source. See the conservation strategy suggestions in box I.7.

Indoors __________

Outdoors __________

F. Greywater sources

Estimate the average volume of accessible household greywater you could reuse within your landscape, using the information in boxes 2.6 to 2.8. Accessible means you can access current drain pipes or install new ones to direct the greywater to mulched and vegetated basins within the landscape. You will need to maintain a minimum 1/4-inch drop per linear foot of pipe (2-cm drop per linear meter) for gravity to freely and conveniently distribute your greywater from a point downstream of the p-trap for the greywater source (washing machine, sink, etc.) to the greywater pipe outlet in the landscape.

washing machine __________

shower __________

bathtub __________

bathroom sink __________

kitchen sink (dark greywater) __________

other __________

Total __________

G. Additional “wasted” waters that can become harvested waters

See box 2.9 and estimate the average (or seasonal) volume of household wasted waters you could harvest.

evaporative cooler bleed off ___________

air-conditioning condensate ___________

reverse-osmosis water-filter discharge ___________

other ____________

H. “A One-Page Place Assessment” for Your Location

Look at figure 2.7, “A One-Page Place Assessment” for Tucson, Arizona. Create your own “One-Page Place Assessment” with the how-to tips on the One-Page Place Assessment page on my website HarvestingRainwater.com, or see if an assessment for your community already exists on that webpage. If you lack computer access or skills, take figure 2.7 to your local library or cooperative extension agent, and ask for help finding similar information for your locale. Refer to that One-Page Place Assessment when using this section of the worksheets.

H1. Climate

Temperature variability affects vegetation: human comfort, stress, and potential; and animals both on top and within the soil. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) plant hardiness/climate zone maps reflect this. To find out the USDA plant zone you are in, see http://planthardiness.ars.usda.gov/PHZMWeb/

The USDA generates new maps as climates change. You can learn a lot when you compare past and current maps. For maps that compare and illustrate differences between 1990 and 2012, see http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/special/local/planthardinesszones/index.html. And for predicted future changes due to climate change see http://epa.gov/climatechange/

Has your climate zone changed? __________

What was it before? __________

How have USDA Hardiness Zone Maps changed due to a changing climate? __________

For the 1960 and 1965 USDA Hardiness Zone Maps see http://www.garden.bsewall.com/topics/hardiness/history.html

How do you feel your climate’s temperatures at the following times?

What are comfortable indoor temperatures and how can we adapt to feel comfortable in an expanded indoor temperature range? In the U.S., 72˚F (22.2˚C) is often considered a comfortable mean indoor temperature, yet authors David Bainbridge and Ken Haggard, in Passive Solar Architecture state that in China “rural residents found indoor winter temperatures of 52.7˚F (11.5˚C) comfortable, while urban Chinese felt 57˚F (13.8˚C) was better; … many people when sleeping prefer cooler temperatures and a good comforter, … and can be quite comfortable at 60˚F or less; … and in summer 80% of the people may feel comfortable at 86˚F (30˚C) in tropical climates with outdoor mean monthly air temperatures of 95˚F (35˚C).”1

How could a change of attitudes or practices change your perception of hot and cold? __________

What changes in your clothing could help provide free heating (sweaters or long underwear, for instance) and cooling (shorts and short sleeves)? __________

What do you observe about the seasonal difference between daily outdoor high temperatures and nightly low temperatures? __________

At your location, are hot daily high temperatures offset by cool nights? __________

Are cold nightly temperatures offset by warm daytime temperatures? __________

If so, when __________?

In your area, how do average high and low temperatures compare to the record high and low? __________

How can you could moderate such extreme temperatures with the addition of on-site water harvesting, shading, solar access, and other passive strategies. See chapters 3 and 4 for ideas. Write down your thoughts. __________

H2: Sun

Where does the sun rise and set on the summer solstice at your location? __________

Where does the sun rise and set on the in winter solstice? __________

Where and how is the sun’s rising and setting in summer different from that in winter? __________

Can you visualize the sun's rising and setting, during winter and summer? Spring and fall? Sketch out a site map for your location showing the part of the sky the sun rises and sets in during these seasons. Take a look at the sun path diagram for your latitude in appendix 7 to help you fill out this section. Write any observations. __________

How high is the sun at noon in different seasons of the year (winter and summer solstices, spring and fall equinoxes)? __________

What times of year and where might you want to deflect that sun? When and where might you want to harvest that sun?

How does the sun’s seasonal path at your site compare to seasonal sun paths at other latitudes where you, friends, and/or family have lived? __________

Now, look at the monthly average temperatures (in A One-Page Place Assessment and How To Use It) for these different times of the year. What correlation do you observe in your location between the sun’s position and average monthly temperatures? __________

What times of year do you have more sunny days, and when do you have more cloudy days (look at the water section)? __________

How might the number of sunny and cloudy days affect the potential to produce renewable power at your site? __________

In the coastal northwest U.S. sunny summers make solar power viable in that season, while overcast rainy falls, winters, and springs make micro-hydro power viable in those seasons. Look at the wind section for wind power potential.

Note how the insulating, blanket-like effect of cloudy high-humidity weather reduces temperature fluctuations between day and night. In contrast, cloudless, low-humidity weather allows radiant heat to quickly dissipate into the atmosphere at night, resulting in lower nighttime temperatures and greater temperature fluctuations between day and night.

What is your site’s elevation and how does that affect temperature? __________

On the average, temperatures drop 3.5° F (1.94° C) per 1,000 feet (304 m) of altitude.2 However, this temperature drop is greater in sunny weather (5.4˚ F/1,000 ft or 9.8˚ C/1,000 m) and less in rainy, snowy, overcast weather (3.3˚ F/1,000 ft or 6˚ C/1,000 m).3

H3. Wind

Note how the wind’s speed and direction varies when affected by landforms, buildings, and vegetation. As with water, the wind’s velocity increases when its path is constricted and straightened. Thus, when straight roads and paths—and the trees and shrubs planted along them—are parallel with the wind’s direction, these locations may become wind tunnels in high-speed winds. Meandering roads and paths, along with their adjoining vegetation, can lessen this effect. See appendix 8 for more on wind patterns and strategies to harvest or deflect these winds, and see chapter 4 for ideas on how to integrate these wind strategies with sun and shade harvesting. Write down any thoughts and/or observations on your local wind patterns. ___________

H4. Water

Based on your location’s precipitation data, what can you conclude about rainfall distribution? How many “rainy seasons” are there per year, and when do they occur? __________

Compare average monthly temperatures to average monthly rainfall. Does rain fall in warmer months when growing plants need more water? __________

If not, how could you increase water availability and storage when rain does fall to get you through dry months and droughts? __________

See chapter 3 for ideas.

If you have a rainwater tank/cistern, at what time(s) of the year would you be filling it? __________

How often could you fill it, use the rainwater, and refill it in the course of a year? __________

How much of your precipitation falls as rain and how much as snow? __________

If you have a tank, is there a winter-time risk in your location of frozen pipes and tank, or iced-over downspouts and rainhead screens? __________ If so, how would you deal with these issues? __________

Your freeze-protection strategies might include placing the tank, downspouts, and rainhead screens where they would be warmed by winter sun. You could also disconnect, shut off, and/or drain water-holding pipes during months when freezing could occur. In addition, you could install your plumbing underground below the frost line.

How much of your community’s utility water consumption could be met by harvesting rainfall community wide? __________

What other conclusions can you draw? __________

H5. Watergy

See appendix 9 for information about the Water-Energy connection.

What data can you find out data for your city? _________

If none, use the data provided in the Water Costs of Energy, Energy Costs of Water, and Carbon Costs of Energy charts in appendix 9.

What are some ways you can reduce your water, energy, and carbon footprint, and your community’s footprint? __________

See Table A9.1 One Average U.S. Household’s Monthly Energy-Water-Carbon Costs for ideas of changes you could make in your household.

H6: Totem Species

Ask staff at a local nature center, natural history museum, or library for information about endangered species, ecosystems, and water sources in your area. What did you learn? __________

Ask long-time residents which animal and plant species they remember being abundant when they first lived here and what the landscape looked like. __________

What species are missing or hardly seen now? __________

Which species are common now, or more common? __________

What contributed to their rise and fall? __________

What can you do to help create or enhance healthy habitat/conditions for indigenous species, ecosystems, and water sources? __________

H7. Taking your One-Page Place Assessment further

What other key indicators (past, present, and future) of the health, challenges, and potential of your location should be captured in your One-Page Place Assessment (these may make your assessment longer than one page)? __________

Consider including:

•Information on your area’s geology and soils. For example are you losing, maintaining, or gaining topsoil, organic matter, and fertility?

•Light pollution or its abatement to your assessment, to monitor how many constellations are disappearing or reappearing in your night sky. These constellations more directly connect us to the stories, histories, and knowledge of cultures that have used those stars in the past.

•Culture indicators, including diversity and density of different cultural groups in the past and present, the languages spoken, how long these cultures have been present, what knowledge and strategies supported them then and support them now, and how these have changed.

See the “How to Create Your Own One-Page Place Assessment” subpage on the One-Page Place Assessment page at HarvestingRainwater.com for tips on, and resources for, these additional indicators and more.

STEP 2/CHAPTER 3: OVERVIEW: HAVESTING WATER WITH EARTHWORKS, TANKS, OR BOTH

Refer to the comparisons in box 3.1 and see the overview of strategies later in chapter 3 to decide how you might best harvest the water for your planned uses.

Now that you’ve (more or less) estimated your on-site water resources and needs (from the previous worksheets), the next step is to answer again the following questions:

How do you currently use your water resources (rough breakdown):

indoors_______

outdoors_______

How do you plan to use your water resources?

landscape and garden use_______

washing and bathing_______

potable use_______

other_______

After reviewing chapter 3, and the Eight Rainwater-Harvesting Principles from chapter 1, what do you think you’d want to do:

first?_______

second?_______

third?_______

Compare the above to your answers in the earlier interlude. What’s different, now that you have more information to work from?

STEP 3/CHAPTER 4: INTEGRATED DESIGN

This chapter is intended to heighten your awareness of additional on-site resources and challenges, and to show you how to maximize their potential by integrating their harvest with that of water. The numbers below follow the Seven Integrated Design Patterns and their Action Steps found in chapter four.

If needed, make a new photocopy of your site map and mark the directions of north, south, east, and west.

One: Orienting Buildings and Landscapes to the Sun

•What is your site’s latitude (web search it or ask your local friendly librarian if you don’t know): __________

•How is your site and/or your home oriented? (See figures 4.5A and B). Put this information on your site map as well as writing it below.

On your site map:

•Identify the “winter-sun/equator-facing side,” and the “winter-shade side” of your home.

•Map the location of the rising and setting sun on the summer and winter solstice.

•Also mark any of the following, and any additional incoming resources or challenges (see figure 4.4): where you would like more shade or exposure to sun; the direction or location where prevailing winds, noise, or light come from; and the foot traffic patterns of people, pets, or wildlife.

•Where are the warm and cold spots in winter? The hot and cool spots in summer? What areas inside your house get direct sun in the morning and afternoon, in winter and summer? Do you get sun and shade on your garden and outdoor areas when and where you want it? Mark your site map appropriately and write your observations below.

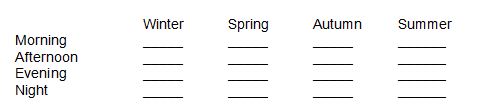

•Shut off all mechanical heating and cooling systems on a couple of sunny days at least once in each season of the year to observe how direct solar exposure—or the lack of it—affects the comfort of your home and yard. (Though don’t do this when there is a possibility your pipes could freeze. And if such pipe freezing could occur then look into how you could retrofit your home so your pipes would not freeze if the power were shut off.) When you shut off all mechanical heating and cooling systems, what are your observations?

winter __________ spring __________

autumn __________ summer __________

Two: Designing Roof Overhangs and Awnings

•Do you have window overhangs? __________

•If so, what is their projection length on the winter-sun side of your house? See figures 4.6A and B__________

•Use the overhang projection information in the Two: Designing Roof Overhangs and Awnings section to determine appropriate overhang sizes for your winter-sun side windows. __________

•Compare existing overhangs to what the calculation or to-scale drawing recommends. __________

•What have you noticed about how overhangs or the lack of them affect your comfort throughout the year? __________

•What can you do (put up awnings or trellises, plant trees, extend overhangs, open up a covered section of winter-sun-facing porch, etc.) to enhance the positive ways sun and shade can affect your building? __________

2B. Windows

Windows are important. Assess where the windows are in your house; how much window area can be opened (casement windows typically let you open the whole window area; sash or slider windows typically let you open half); and whether they have single or double panes, or storm windows (for better insulation), and/or screens (for insect-free summer ventilation)? Write your observations. __________

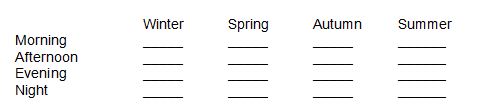

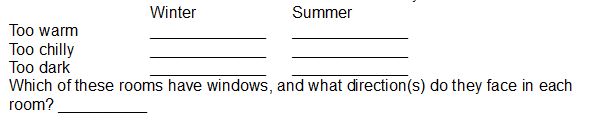

Windows can affect seasonal comfort. In which rooms of your house is it:

How could comfort and energy efficiency be improved by:

Increasing window areas? __________

Adding seasonal shading using an outside overhang or awning? __________

Removing obstructing vegetation outside to allow more sun in? ___________

Making inoperable windows operable/openable to increase ventilation? ___________

Adding an interior transom window?____________

See appendix 8 for how to increase natural ventilation of your rooms and house using different window types and orientations and appropriate placement of outdoor vegetation.

In rooms that are too dark, consider adding windows before adding skylights. Skylights can let in too much direct sun and heat on summer days, and let out valuable heat on winter nights. They can leak when it rains, and may be expensive to replace if damaged.

Prioritize adding windows on the equator-facing side of your house where more winter heating may be needed. Minimize window openings or their access to direct sun on east and west-facing sides if morning and afternoon summer heat gain needs to be reduced.

Consider adding interior operable windows to let light and ventilation pass from one room to the next. High transom windows or opaque glass can be used to maintain privacy between rooms.

Test the winter heat-gain potential of your equator-facing windows on a sunny winter day by putting your hand in the direct sun inside the building window without touching the window glass. If your hand feels warm or hot, it probably is not a low-E window and therefore it is the right kind of window for solar heat gain in winter. If you do not feel significant warmth it is probably a low-E window and will reduce desired passive winter heating. If you need more winter solar gain, you may want to replace low-E windows on the equator-facing side of your house. Write your observations below: __________

See box 4.4 Window Choices Dramatically Affect Passive/Free Heating and Cooling for more info on how to choose the best window glass for you.

Do the same window test when the sun shines through windows on the non-equator-facing sides of your house—especially in the hot months. In these cases, you might not want the added heat from the sun. Depending on your climate and surrounding vegetation, for non-equator-facing windows—including storm windows—you might want to use a low-E type glass that reflects summer heat and insulates interior heat in the cooler seasons. Write your observations below:

__________

In each room with equator-facing windows that receive direct winter sun, what percentage of their floor area equates to the equator-facing windows’ area? __________ (See box 4.5 for guidance.)

Is this a big enough window area to keep you warm enough (or largely so) on sunny days in winter? __________

Is this window area shaded sufficiently by an overhang or awning to keep you cool enough in summer? __________

How does the percentage of your equator-facing window area compared to your floor area compare to the recommendation(s) for your climate in box 4.5?

Make a new site map if needed.

•Do you have any elements of a solar arc in place around your home or garden, such as an existing shade tree, covered porch, or building? If so, mark them on your site map and write comments about them below.

•Now, indicate on your site map where missing pieces of a solar arc should be located to complete it and benefit your home or garden.

•Can you use any water-harvesting strategies (earthworks, trees, cisterns) to create or grow a solar arc or a windbreak?

•From where (roof, patio, etc.) could you harvest on-site water to grow shade where you need it? Chapter 3 gives you ideas.

On your site map, mark where a sun trap might make sense, and indicate any existing elements already in place. Write your observations below.

•Consider the desirability of a fence, new cistern, or plantings within earthworks such as trees, large shrubs, or vines growing on trellises, fences, etc. to create a sun trap. Write any thoughts below.

Five: Maintaining Winter Sun Access

•Where have you noticed winter shadows blocking your sun? Write down observations below, and on your site map indicate features (trees, etc.) that produce long winter shadows.

•What would be the length of a shadow cast by a 20-foot (6-m) tree by the noonday sun on the winter solstice at yourlatitude (see the shadow-ratio correlation in box 4.9 and figures 4.17A to 4.20B)? __________

•Given this information, based on the tree’s height how far to the south (in northern hemisphere) or to the north (in southern hemisphere) would that tree need to be placed from your home if you do not want it to shade your house in winter?

•Solar Rights: Are any buildings, trees, or other structures on your site blocking you or any of your neighbors’ key winter solar access for equator-facing windows, walls, and roof between the hours of 9 A.M. and 3 P.M. or between 10 A.M. and 2 P.M. in latitudes above 40˚? __________

What are these obstructions? ___________

How much do they block the sun? __________

How can they be altered (for example, pruning or thinning trees or shrubs, figure 4.21) to increase solar access? __________

See Box 4.10 Solar Access, Easements, and Rights for more.

•Now, think about where you might want to add appropriately placed new vegetation, structures, or windbreaks to avoid blocking desired winter sunlight for winter sun-facing windows, winter gardens, and solar strategies, while providing other benefits. Note any observations below, and pencil in on your site map if necessary.

Six: Raised Paths, Sunken Basins

•Write your observations of the following: the relative height of paths, patios, sidewalks, driveways and streets compared to adjacent planting areas in your home and community.

•Do you see any “raised path, sunken basin” patterns or a sunken path, raised planting area pattern?

•Is storm water being directed to vegetation, asphalt, or storm drains?

•Now, identify and map areas where you could develop the raised path, sunken basin pattern at home.

Seven: Reduce Paving and Make It Permeable

•Below, write examples of pervious and impervious paving around your home and community.

•Write any thoughts about how you can: reduce the paving on your site; either direct the remaining pavement’s runoff into adjoining earthworks or make remaining pavement more permeable; turn your driveway into a “park-way” or use porous brick, cobbles, or angular open-graded gravel instead of an impervious material such as concrete; etc.

Eight: Degenerative, Generative, and Regenerative Investments

Read the Integrating the Elements and Patterns of Your Site to Create a Regenerative Landscape Design section, then answer the following:

What percentage of your investments in your site (and your life) of effort, time, money, material, or labor are degenerative? _________

What are some examples? _________

What percentage are generative? ________

What are some examples? _________

What percentage are regenerative? ________

What are some examples? _________

What degenerative investments can you transform into generative investments? ________

How will you do this? ________

What generative investments can you transform into regenerative investments? ________

How will you do this? ________

Nine: Tying it All Together: Creating an Integrated Design

Read the linked section above, and remember that you don’t have to implement everything all at once. Start small, start at the top… And—if future observations or realizations justify a change in your plan after you’ve begun implementation, make a change. This is all a process based on long and thoughtful observation, continuing for the duration of your relationship with the site.

CHAPTER 5: AN INTEGRATED URBAN HOME AND NEIGHBORHOOD RETROFIT

What is your site’s regenerative potential?

What is your regenerative potential partnering with the site’s?

What is your community’s essence?

What is the essence of its Place?

What is its regenerative potential?

How can you partner with, and contribute to that potential?

APPENDIX 1. PATTERNS OF WATER AND SEDIMENT FLOW WITH THEIR POTENTIAL WATER-HARVESTING RESPONSE

After reading this appendix, walk your land and your neighborhood (especially its waterways) and observe water and sediment flow patterns. Which do you see?

APPENDIX 2. WATER HARVESTING TRADITIONS IN THE DESERT SOUTHWEST

How might (or how do) these practices of the past inform practices in the present?

Are there similar multi-use plant lists and harvest calendars available in your area? If so, what species and information could you add to them? If not, consider generating them yourself, or working with others, then share them and seek out feedback and participation that can continue to evolve them.