London’s post-war confidence boost is coming to an end. British products are proving harder to sell now that the protected trade routes afforded by the empire have been removed. In addition, a strong pound is making products more expensive, and the quality is deteriorating as UK industry falls far behind more modern competitors. Factories across the city are going out of business at an alarming rate, leaving scores of workers unemployed (between 1959 and 1974, London loses 38% of its manufacturing jobs.) The new trend for using shipping containers has made transport easier and faster, but large container ships can’t reach London docks, and they have to close one by one. New jobs are emerging in the service industry, but not nearly enough. War in the Middle East and the resulting 1973 oil crisis prove to be the final straw – quality of life in the city is declining for the first time in decades.

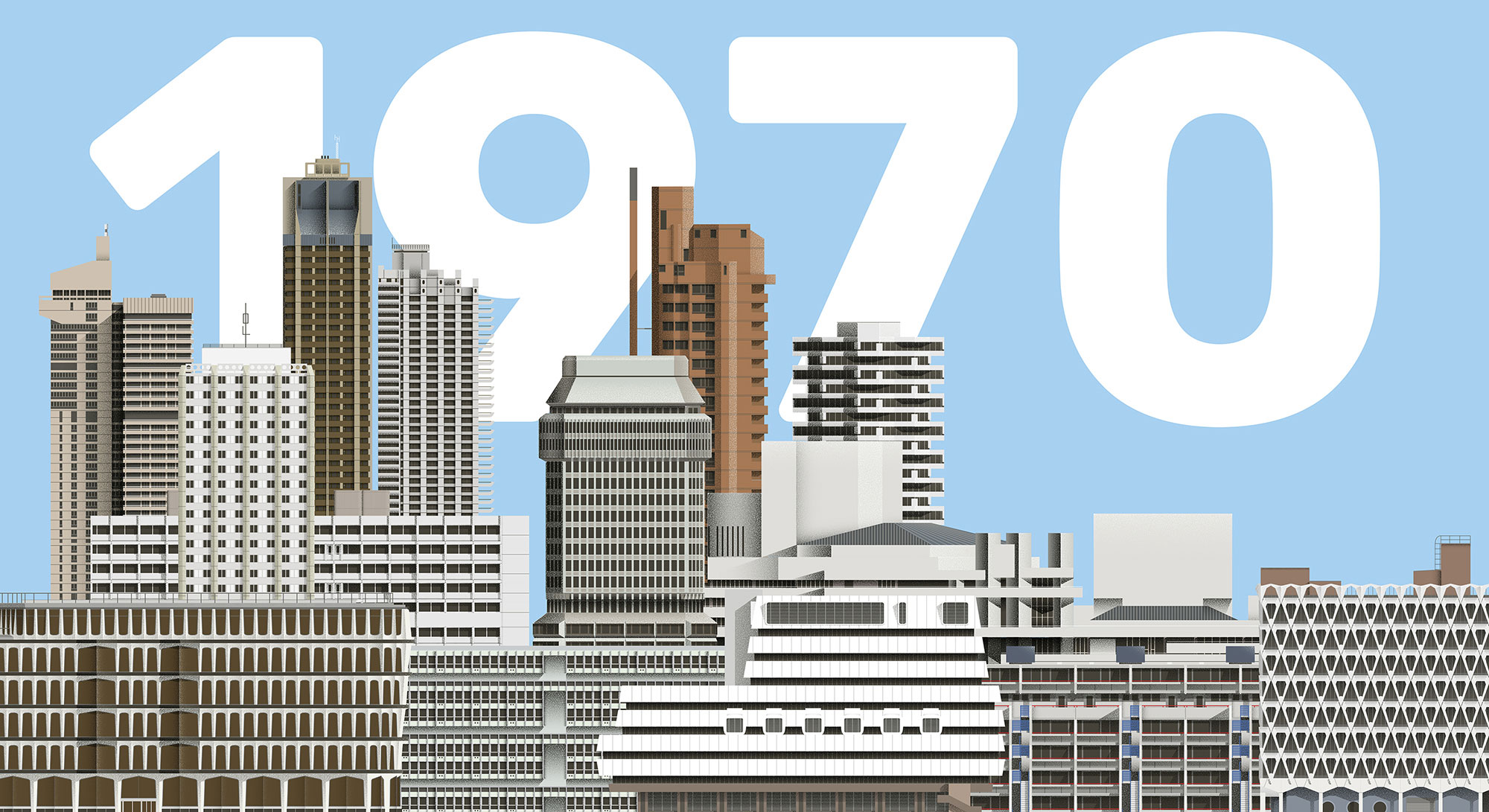

Croydon was an area that saw significant post-war development, earning it the (slightly sarcastic) nickname of ‘mini Manhattan’; its high-rise towers and car-friendly streets were the work of James Marshall, the authoritarian leader of Croydon Council who hoped to capitalise on the building boom. Many corporations took advantage of the cheap land and limited planning restrictions, relocating there from central London.

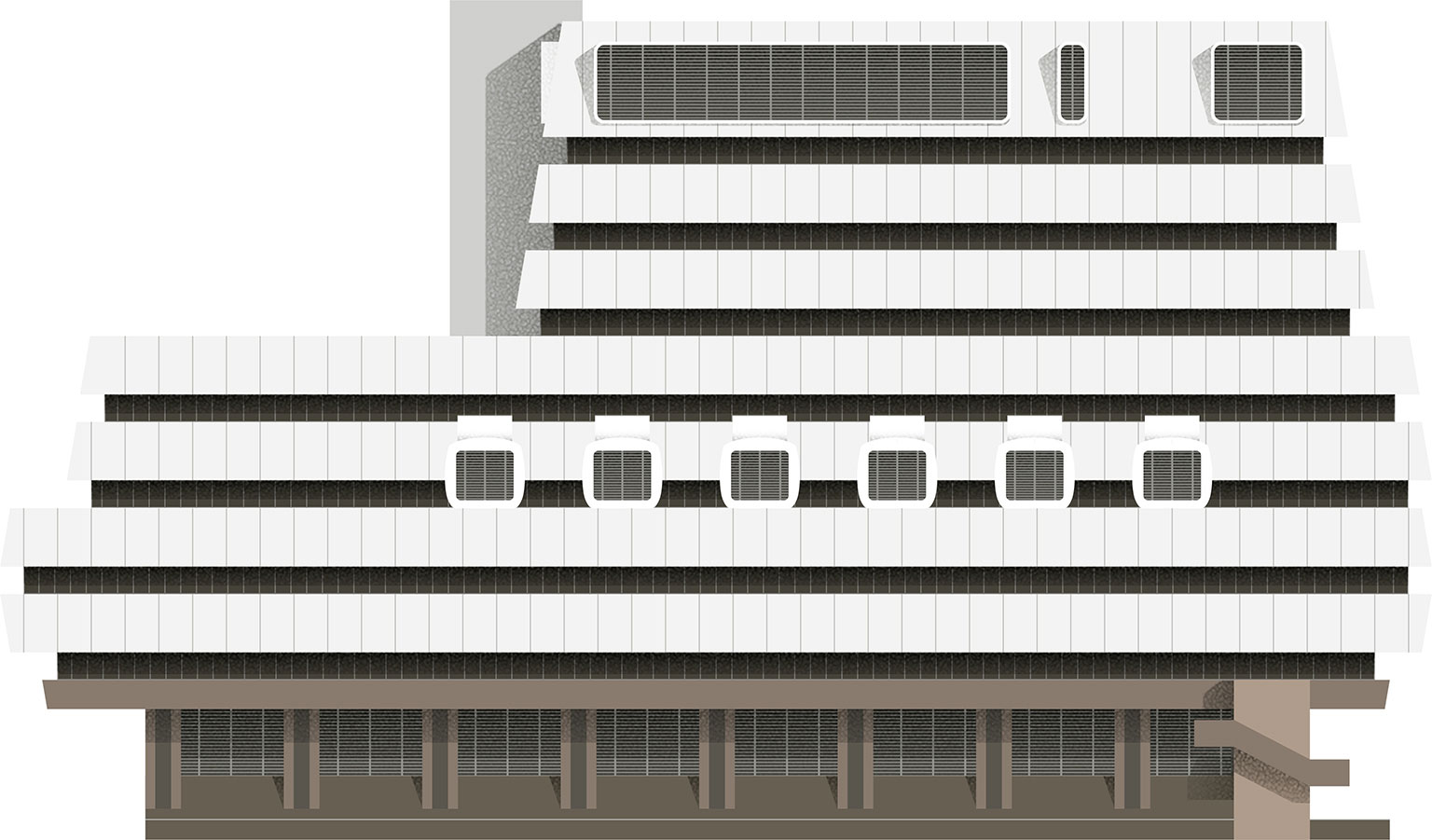

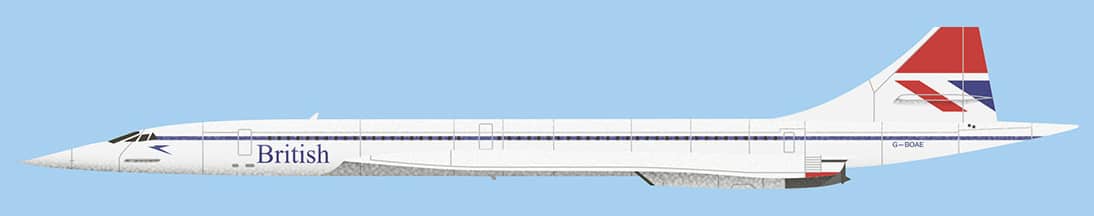

Richard Seifert’s practice added the NLA Tower (063) (now No 1 Croydon) to the skyline. It became known locally as ‘the wedding cake’ or ‘50p building’, in response to its layered storeys and trimmed edges. The tower was originally planned as part of a larger development, but a single homeowner refused to sell her house. As a result, the building had to squeeze onto the middle of a roundabout. The resulting geometric beauty is arguably one of R. Seifert and Partners’ best works.

063 NLA Tower

R. Seifert and Partners

1970

1970  CR0 0XT

CR0 0XT  82M

82M

Jubilee Line

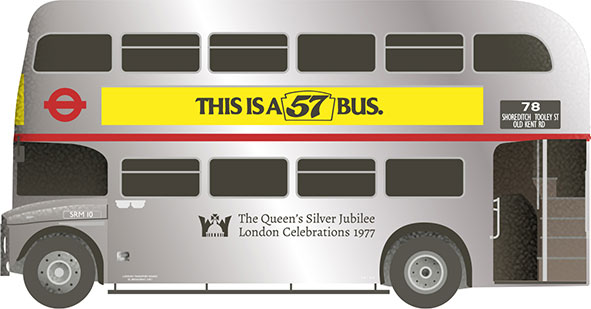

In 1977, Britain celebrated Queen Elizabeth II’s Silver Jubilee, marking twenty-five years on the throne. Subsequently, the name of a new Underground line was changed from the Fleet Line (after the River Fleet) to Jubilee. It officially opened in 1979.

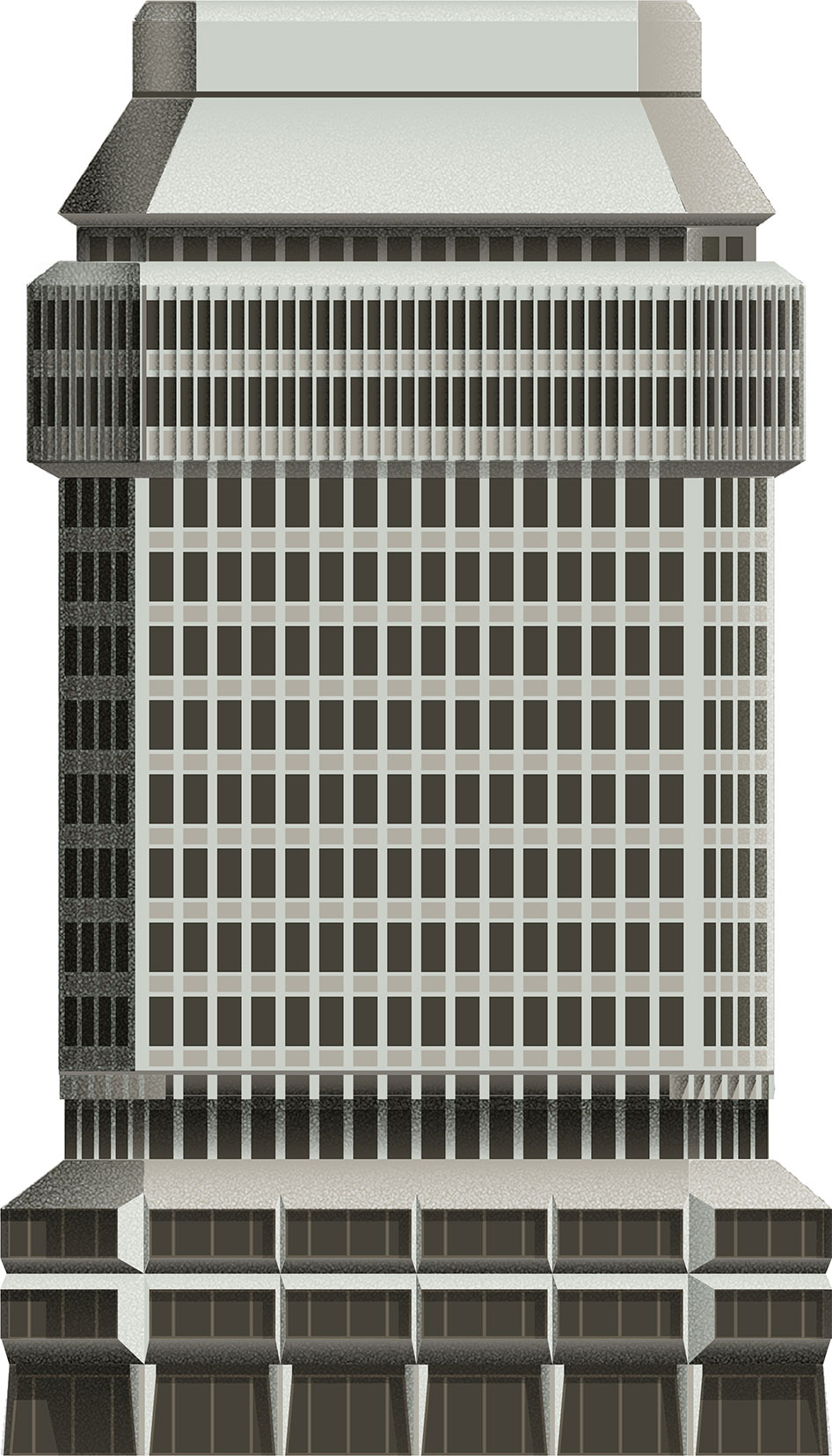

Back in the City, the new Guy’s Tower (064) rose to an incredible 142 metres. The tower opened in 1974 and became the tallest hospital in the world. It kept the title until 1990, probably because it’s not exactly the most practical layout for a hospital. The building is actually made of two parts. A plain block with strip windows is connected to the service tower, which has a strange bulge of a lecture theatre on the top floor. In 2014, it was badly weathered and the concrete façade was reclad with ‘fancy’ aluminium panels, which incidentally make it look worse.

064 Guy’s Tower

W. H. Watkins, Gray and Partners

1974

1974  SE1 9RT

SE1 9RT  142M

142M

Amid a declining quality of life, dismay in London grew. Unemployment rose dramatically, as did prices – in 1975, inflation reached 25%. The economy was crippled by massive strikes by powerful trade unions, and the government had to introduce a three-day week in order to save energy. Streets and parks were flooded with rubbish, as waste collectors went on strike. Meanwhile, the conflict in Northern Ireland grew bloodier. The violence had begun in the 1960s, but at this point was barely making headlines in the UK. Irish Republicans decided to change all that and began a bombing campaign on London, in the belief that spreading fear and terror would force the government to retreat its advances on Northern Ireland.

But while the language of the gun was how some did business, old-fashioned diplomacy was also still a powerful force, and other countries wanted a new embassy just like the US (see 059). The Czechoslovak Embassy (065) in Kensington offered the central European country the opportunity to present itself and its rich architectural history (of which it was particularly proud) to an international audience. The project started in 1965 and remained on track for completion even after the country was invaded by Soviet forces three years later.

065 Czechoslovak Embassy

Jan Bočan, Jan Šrámek, Robert Matthew

1970

1970  W8 4QY

W8 4QY

A team of progressive architects was led by Jan Šrámek – they went on to design a number of embassies around the globe. In London, they joined forces with Robert Matthew, one of the architects of the Royal Festival Hall (036). Critics admired the quality of the work and technical detail, and in 1971 the building was unanimously voted by RIBA as the best work by a foreign architect in the UK. Back in Czechoslovakia, people linked the new brutalist buildings with the growingly oppressive communist regime and were (and still are) far from appreciative of them.

HMS Belfast

The almost 200-metre-long cruiser served with the Royal Navy in the Second World War and the Korean War. After it was decommissioned, it was moored between Tower and London Bridge and became a museum ship in 1971.

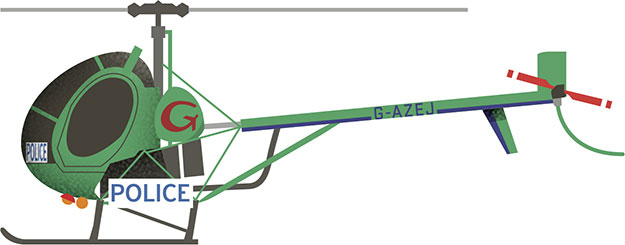

Hughes 300

The nimble American helicopter was operated by the first British female commercial helicopter pilot, Gay Absalom Barrett. She flew missions for the Metropolitan Police in the early 1970s.

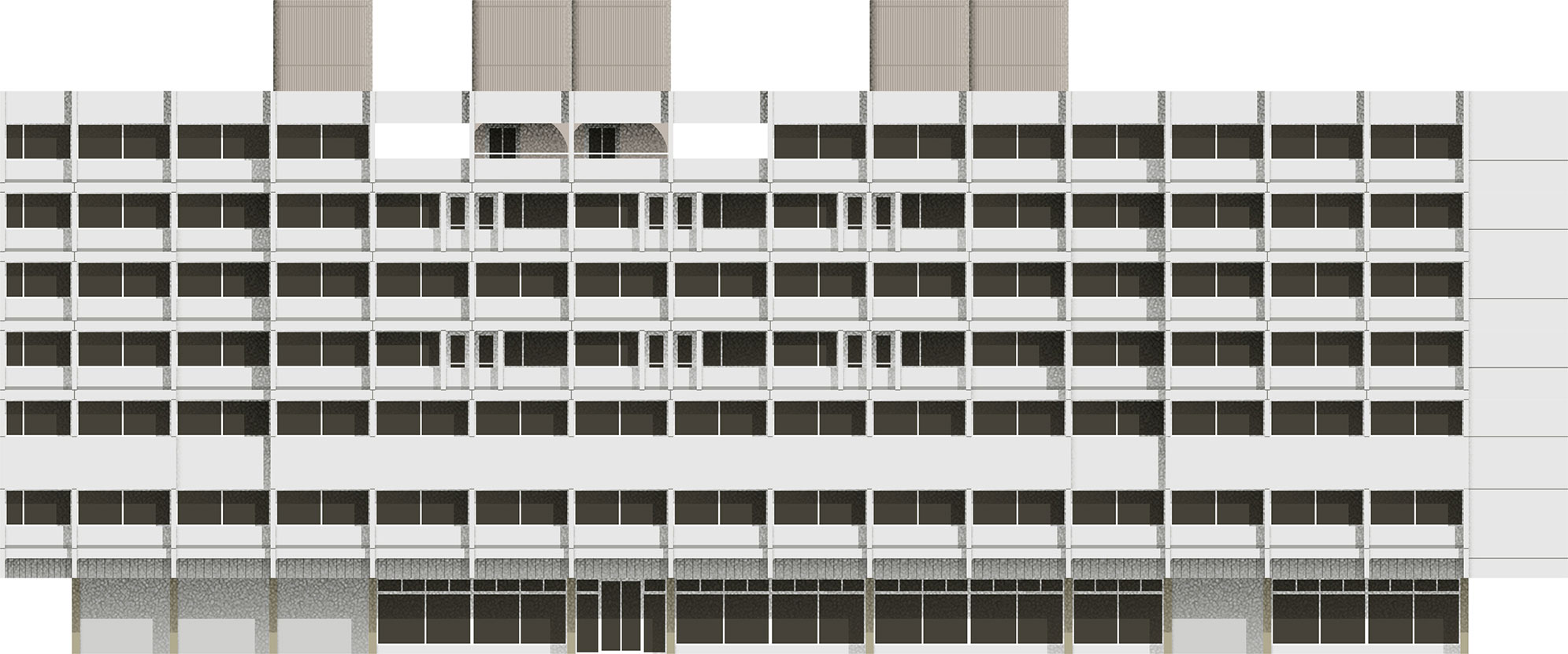

Prince Charles had a similar opinion on almost any new building, and rallying against modern architecture became one of his pastimes when off royal duty. He used his connections and influence to sabotage a number of modern developments, most notably the extension of the National Gallery. The Darth Vader of modern architecture branded Mondial House (066) ‘a word processor’ (early computer), which was a surprisingly close call – it being the main telecommunications hub in the country.

066 Mondial House

Hubbard, Ford and Partners

1978

1978  2007

2007  EC4R 3UB

EC4R 3UB

The futuristic concrete structure was clad in pristine glass-reinforced polystyrene panels, which stayed bright even after thirty years. Built in the middle of the Cold War, the bomb-proof building was specifically designed with protection in mind (it being strategically very important) – it had backup generators, hence the six cooling cubes on the roof. Sitting on the banks of the River Thames, its floors sloped down towards the riverbank, so as not to obstruct the view of St Paul’s Cathedral (like its predecessor the Faraday Building (026) had done forty years earlier). Technology developed with incredible speed, and the equipment inside soon became obsolete. In 2005, to Prince Charles’ relief, the building was demolished.

Contemporary lettering cast in concrete

Only a few architects managed to be both admired and loathed during their lifetime. Basil Spence was one of them. The Scottish architect became known after winning a major competition for the new Coventry Cathedral, the original having been destroyed in the Blitz. While busy working on a pavilion for the Festival of Britain, he designed the cathedral as an evening project. His unconventional design was disliked by the public, the press and even Coventry Council itself. Nevertheless, the cathedral was constructed, and most people grew to like it after a couple of decades.

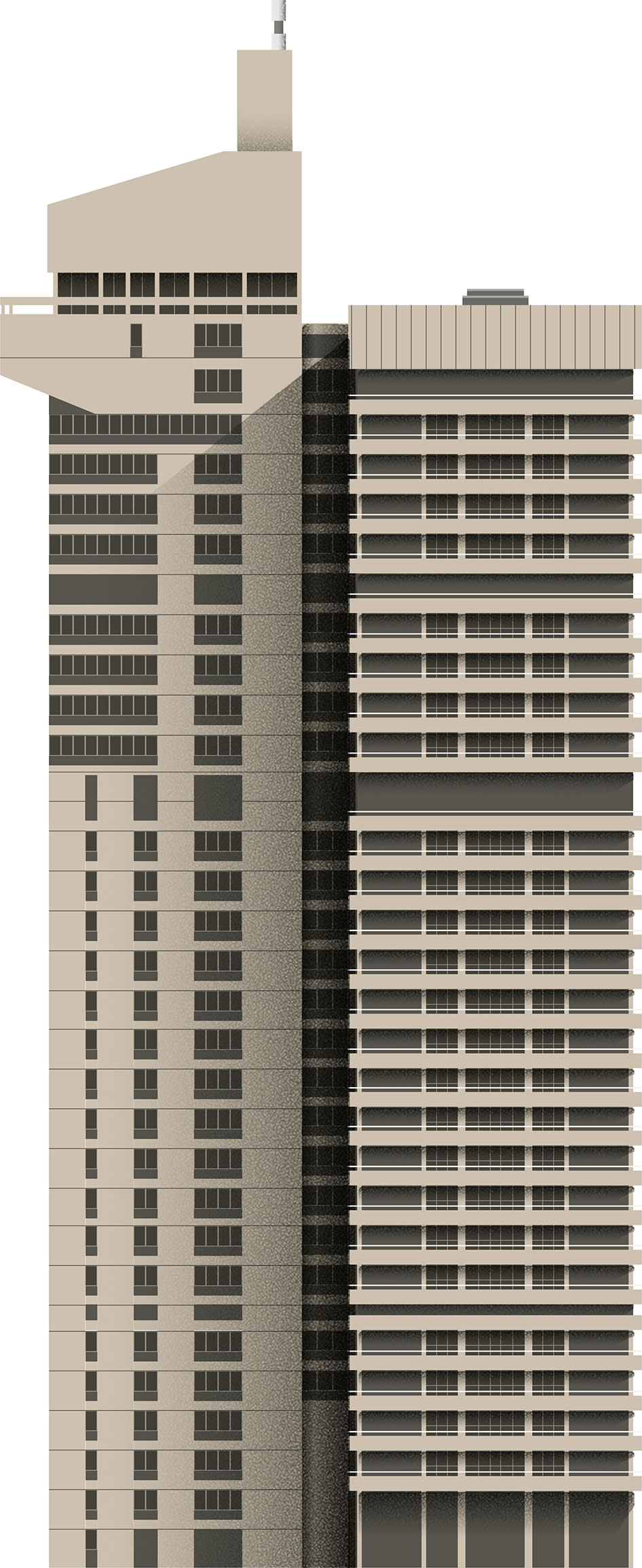

Spence’s Hyde Park Barracks (067) proved to be controversial as well. The home of the Household Cavalry, the barracks are just a short horse ride away from Buckingham Palace, where the cavalry conducts ceremonial duties. The long, narrow site on which Spence’s building now stands had been occupied by the cavalry since 1795, and by this point they were fast outgrowing it. Spence was asked to squeeze in new quarters and a mess hall to accommodate 500 soldiers, along with stables for 273 horses – all while leaving enough space for parade grounds where the soldiers and horses could train.

067 Hyde Park Barracks

Basil Spence

1970

1970  SW7 1SE

SW7 1SE  94M

94M

The architect’s solution was to build a thirty-three-storey tower and couple it with additional lower blocks. He reasoned that the tall and slender tower wouldn’t block views of the park or cast a large shadow, which a lower and wider building slab would. The downside, of course, is that it is much more visible from the park.

Not far away is another Spence work – 50 Queen Anne’s Gate (068) was built on the site of Queen Anne’s Mansions, dating from 1877. The original building was extremely tall for its time and blocked views of the Houses of Parliament from Buckingham Palace. As a result, legislation limiting building height was introduced. There wasn’t much opposition when the unloved building was demolished in the early 1970s. But its replacement garnered outrage again, which uncommonly united the public and the political establishment. Spence, who was the design consultant on the project, was even accused by MPs of providing deceptive drawings.

068 50 Queen Anne’s Gate

Basil Spence

1976

1976  SW1H 9AJ

SW1H 9AJ

The massive, top-heavy concrete building is reminiscent of a fortress, rather than offices. Perhaps suitably, it was a base for the Home Office, which was responsible for everything from security to immigration. Its workers nicknamed the building ‘the Lubyanka’, after the headquarters of the KGB in Moscow. Unfortunately, Spence – no doubt hurt by the mounting rude remarks – died just as the construction was coming to an end.

The Home Office moved in 2005, relocating to new, purpose-built headquarters designed by Terry Farrell. The empty building was refurbished and renamed 102 Petty France. It is now home to the Ministry of Justice.

AEC Routemaster

In 1977, London was captivated by the massive celebrations surrounding Queen Elizabeth II’s Silver Jubilee. A batch of Routemaster buses were painted silver for the occasion.

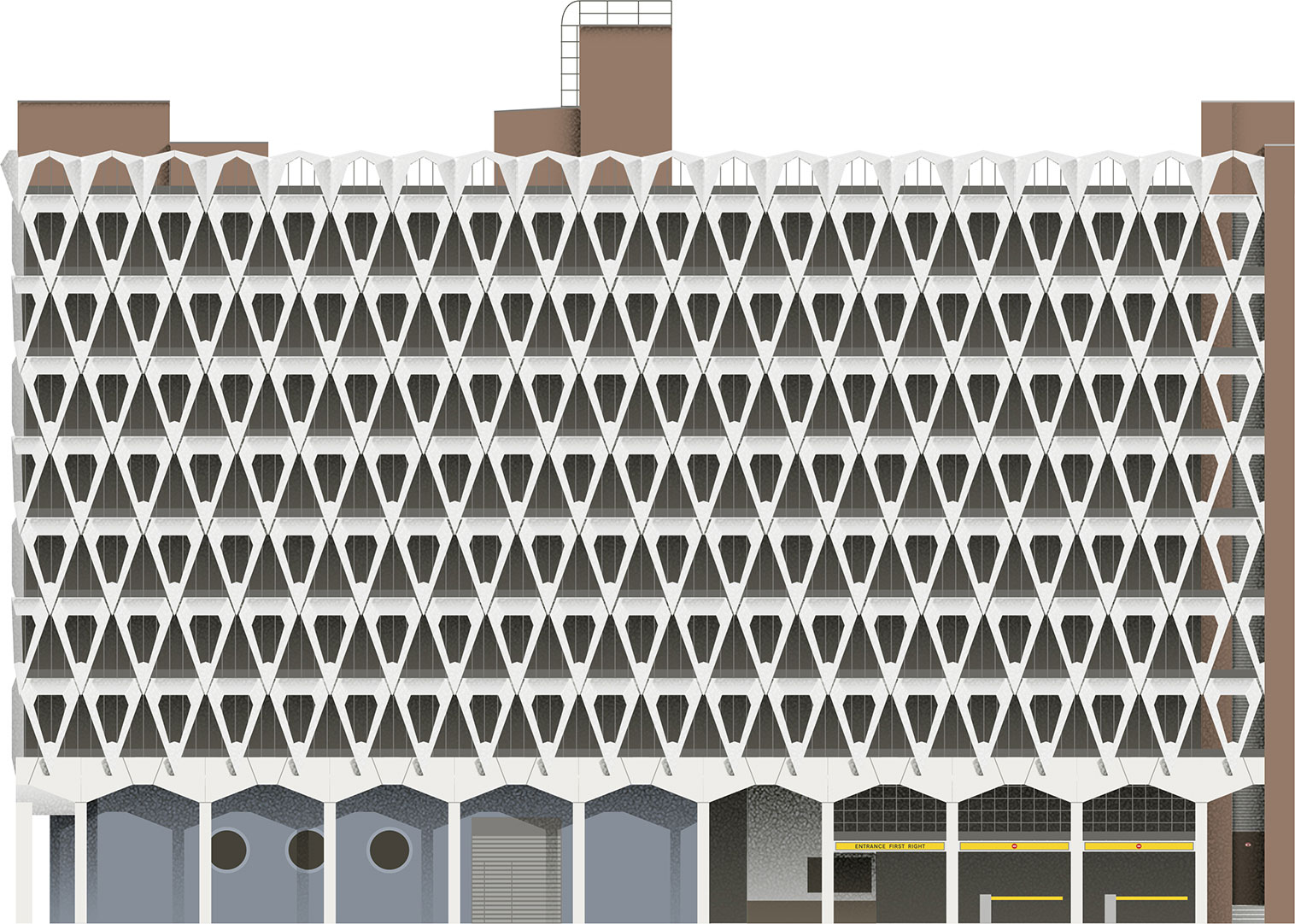

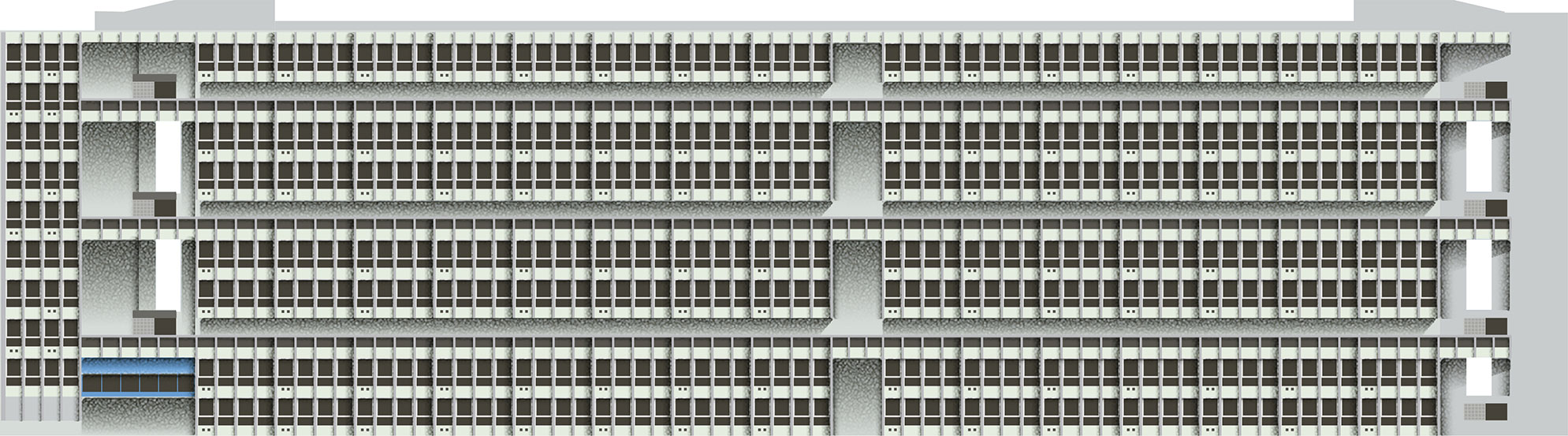

More controversial concrete appeared near Oxford Street, London’s main shopping street. The new Debenhams department store had to build its own parking facilities, as was requested by car-friendly planners of the time. Welbeck Street Car Park (069), with a 400-vehicle capacity, was built just across the road. When finished, the car park attracted more coverage in the architecture press than the actual store.

069 Welbeck Street Car Park

Michael Blampied and Partners

1971

1971  W1G 0BB

W1G 0BB

Its impressive façade is made from interlocked V-shaped concrete units that are also load-bearing, thus removing the need for internal columns – very useful in a car park. Nevertheless, the space was very rarely used – people preferred on-street parking and the area had good public transport links. The building is currently awaiting demolition, despite a lot of support from modernist advocates, as the ground has become increasingly valuable. It is to be replaced by a hotel.

Oxford Austin 1300

Most of the Metropolitan Police Service’s cars up until this point had been painted black, without any markings. When the new colour scheme was introduced, people nicknamed them ‘panda cars’.

Over in the City, more buildings kept rising. The triangle site of 30 Cannon Street (070) was one of the last Second World War bomb sites to be redeveloped, not least because of its challenging proportions. The building’s distinctive façade is made from ultra-modern panels (a mix of fibreglass and cement), which hide a clever drainage system that keeps the surface clean. The lightness of these panels allowed the architects to design external walls sloping outwards in five-degree angles, making every floor larger than the one below.

070 30 Cannon Street

Whinney, Son and Austen Hall

1977

1977  EC4M 6YQ

EC4M 6YQ

Revolutionary at the time (and built for a French bank), it is now fairly common to add extra floor space like this — although with less elegance (see the Walkie Talkie (116)). The glazing itself was tinted bronze, which went some way to shading the interiors. Tinted glass was quite popular during the 1970s, but practically disappeared with the improvement of air conditioning systems and a growing desire for uninterrupted views. Forty years on, the building still looks remarkably modern, unlike the majority of the commercial buildings of this era, which were largely demolished and replaced. It has also been recently refurbished – the dated window glazing now replaced with clear glass.

Extension of the Underground to Heathrow

London’s largest airport was finally connected with the London Underground network in 1977 when Queen Elizabeth II opened the new Piccadilly Line extension.

Concorde

The supersonic airliner was a British-French design that operated from Heathrow from 1976 to 2003. It immediately became an icon and its silhouette even decorates the Heathrow Terminals 1, 2 and 3 Underground station.

Elevated housing was still being built in the 1970s, even after its heyday had waned. Grenfell Tower (071) in North Kensington was built as a part of the Lancaster West Estate. There was already strong opposition to building new housing in the form of tower blocks, but the need to squeeze as many flats onto a site as possible demanded it. The chief architect of the estate, Clifford Wearden, disliked Grenfell Tower, but nonetheless viewed it as a necessary evil.

071 Grenfell Tower

Clifford Wearden and Associates

1974

1974  W11 1TQ

W11 1TQ  67M

67M

In the wake of the Ronan Point tragedy (062), the structure was designed with extra strength in mind. It even featured external concrete columns, something unseen on similar buildings. The ground floor was used as a car park, and the first three floors were designed as commercial units in a bid to encourage local business and to replicate the settings of more organic residential communities.

One summer night in 2017, a fire broke out in a tenant’s kitchen. The residents were instructed to remain in their flats and wait for rescue. This is standard practice in concrete tower blocks, which are specifically designed to contain fires in the affected unit. Unfortunately, the fire breached the confines of the flat and soon spread, engulfing the entire façade. An estimated seventy-one people perished that night.

A preliminary investigation brought some shocking facts to light: Kensington and Chelsea Council had ignored repeated warnings from residents calling for a review of fire safety. During the refurbishment, the council, despite being one of the richest boroughs in the country, had pushed for the cheapest suppliers and materials possible. As a result, the building was clad in a combustible material, which was only slightly cheaper than the alternative fireproof option.

Beagle Pup

In 1973 a City worker accused of fraud was released on bail. He rented this airplane and flew it between the City towers and even through London Bridge. He continued up north, before eventually crashing into a forest.

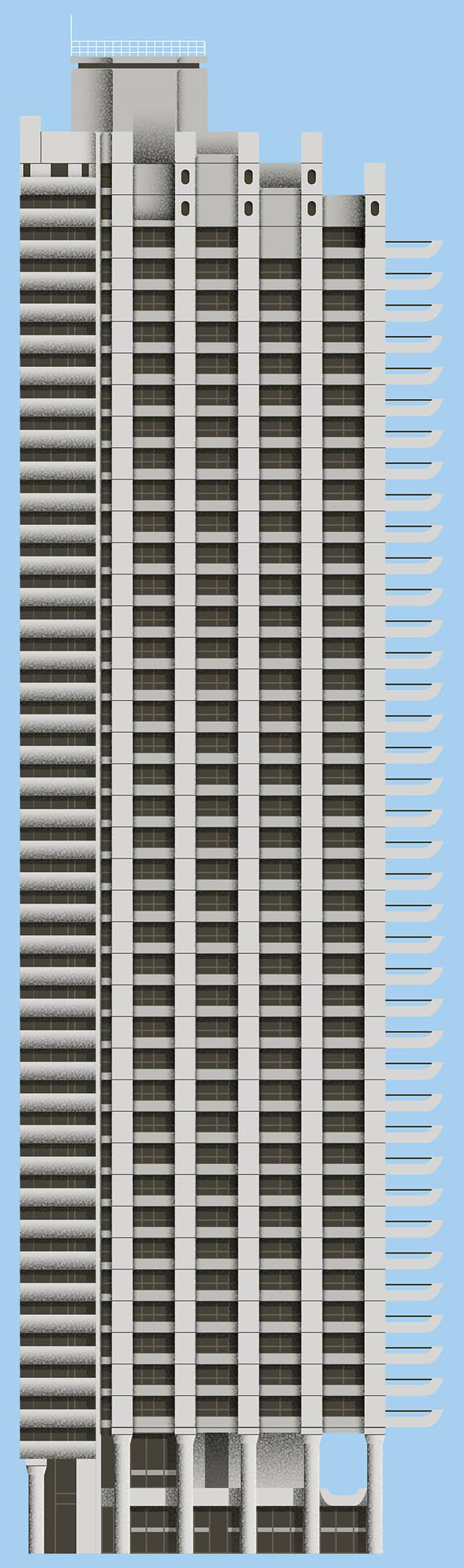

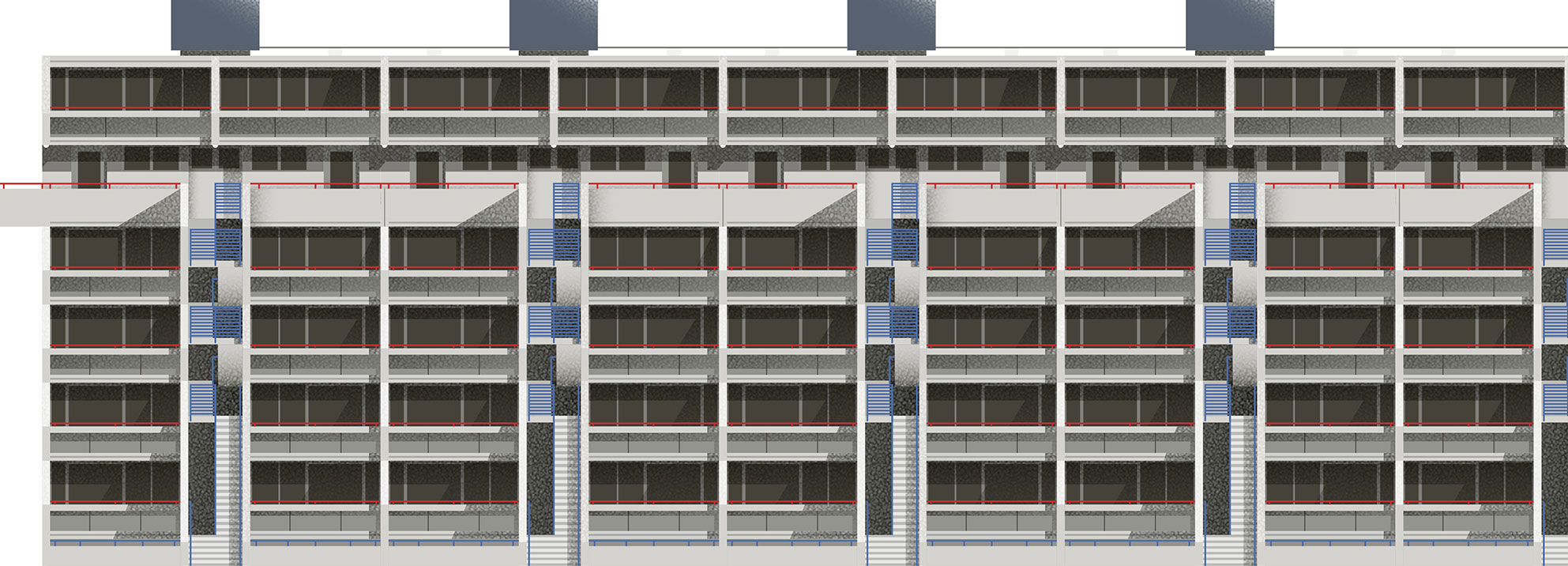

Located in the same borough and designed around the same time as Grenfell Tower, the World’s End Estate (072) is surprisingly different. The architects, Eric Lyons (famous for his modernist Span estates) and Jim Cadbury-Brown, did their best to avoid the mistakes made on high-rise estates of the previous decade. Named after a local pub, the estate was designed for an extremely high population density, almost twice the maximum permitted by London County Council. Plans had initially been rejected and were only passed after a public inquiry, which appreciated the quality of the proposal.

072 World’s End Estate

Jim Cadbury-Brown & Eric Lyons

1977

1977  SW10 0EH

SW10 0EH

Around half of the dwellings are organised into seven high-rise towers of varying heights. The rest of the tenants are spread across low-rise blocks that connect each of the towers, effectively creating one large building. The warm-brick façade stands in contrast to the concrete monoliths of the era, and the polygonal structure helps break down the scale and resulting monotony – two aspects particularly disliked by residents of other estates. It is now a desired place to live and, incredibly, most of the 750 flats are still rented from the council.

The Barbican is one of the most impressive and successful post-war developments in the world. The competition for its design was won by Chamberlin, Powell and Bon who had just finished Golden Lane Estate (043) on the neighbouring site. It was clear from the very start that this was not social housing, but a place for the middle and higher classes – reflected in its construction budget and resulting rents.

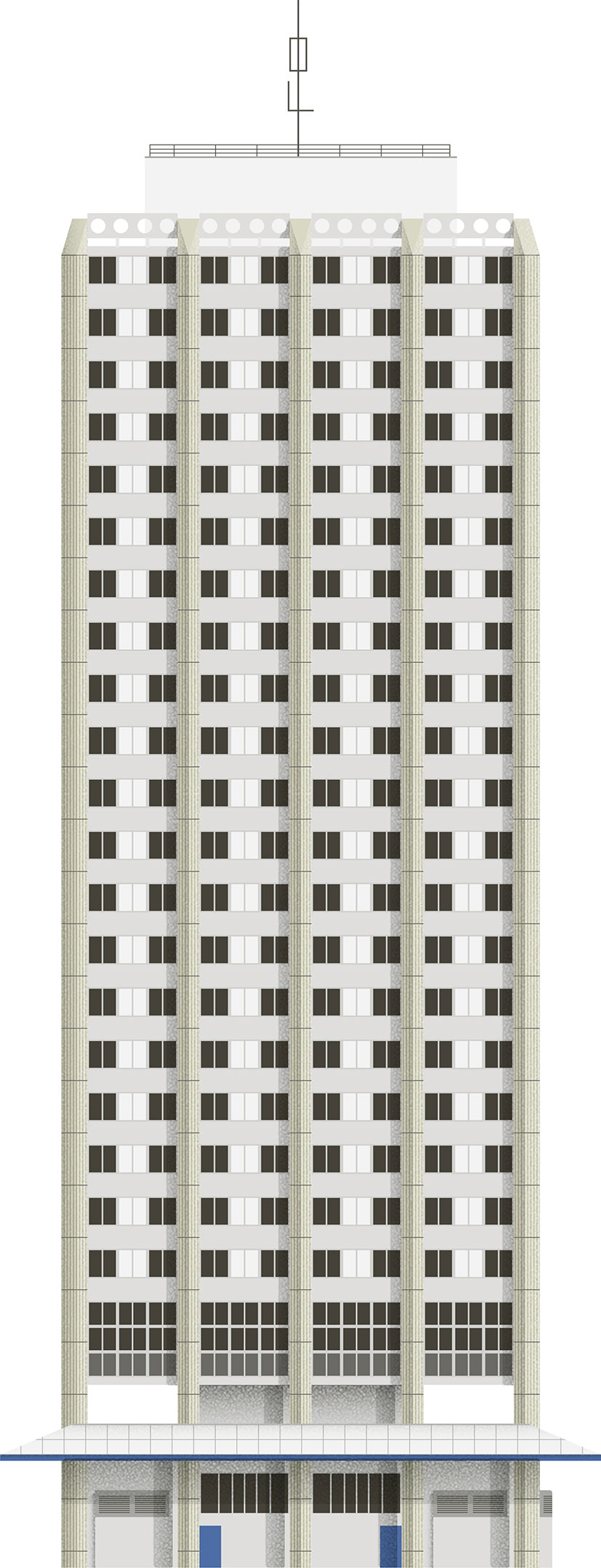

The City was practically empty after the war and the estate was intent on luring people back. Architects designed a vast, car-free complex dominated by three high-rises, including Shakespeare Tower (073). The trio became the tallest residential buildings in Europe. The massive scale of the Barbican complex, alongside numerous builders’ strikes and design tweaks, meant that construction took decades. Barbican Centre (080), one of the last parts to be completed, opened in 1982.

073 Shakespeare Tower

Chamberlin, Powell and Bon

1973

1973  EC2Y 8DD

EC2Y 8DD

But the wait was worth it – it remains one of the most staggering feats of residential design in the world. A rare example of a working ‘city within a city’, the estate is such that residents theoretically never have to leave. Restaurants, shops, parks, an arts centre, a library and even schools form part of the complex.

The original plan saw the Barbican’s walkways connected with a larger system of elevated walkways proposed by the City, named the ‘Pedway’ system. These walkways were intended to stretch right across the City (to the extent that all new buildings had to incorporate street access to the first floor, the NatWest Tower (077) included). Budget cuts – and common sense – meant that the plans were never fully realised.

Daimler Fleetline

London Transport was short of funds and introduced buses operated only by a driver, to save on the salaries of bus conductors. But the buses weren’t reliable and their maintenance proved expensive. After a few years, they disappeared from London’s streets.

The less glamorous council housing at Robin Hood Gardens (074) in Poplar was the product of theoretical work from Alison and Peter Smithson, architects of the outstanding Economist Buildings (060). They developed the design around the concept of ‘streets in the sky’, which had been tried a few times before (with varied success) by other contemporary architects. Wide open walkways provided access to the flats and were supposed to imitate the social life of the actual streets they replaced. But unlike real streets, they weren’t overlooked by residents (the flats backed onto them) and were mostly empty – purely because tenants were spread on different floors and population density was quite low.

074 Robin Hood Gardens

Alison and Peter Smithson

1972

1972  E14 0HG

E14 0HG

The unsupervised space was ideal for vandals and burglars, while the council seriously neglected maintenance and left the buildings to slowly fall apart. Residents’ complaints were twenty times higher than at other Greater London Council estates. The estate was also hemmed in by a busy dual carriageway on three sides. The architects designed a number of clever solutions to limit the noise, including concrete vertical ribs that stopped the sound from travelling over the façade. Another solution was to hide the estate behind a high concrete wall, although this unfortunately isolated the complex.

But by and large the flats would have been envied by most; innovative layouts were generously sized and full of sun. Unfortunately, the rise of nearby Canary Wharf and other commercial pressures accelerated the estate’s demise. Plans were approved to replace the original 252 flats with over 1,500 new homes. Just as the demolition started in late 2017, the Victoria and Albert Museum salvaged a whole three-storey section of the building with the intention to display it.

Commer FC Van

Vans in this dazzling livery were zooming through the streets every day delivering the London Evening Standard, the city’s biggest newspaper.

Further north, Camden Council was very progressive, its architecture department led by Sydney Cook. Cook believed in an alternative to high-rise towers and headhunted the best architects with a similar ethos. Neave Brown – born in New York and who sadly passed away at the start of 2018 – became perhaps the most well-known of them all. Brown believed he could achieve the housing density of high-rise towers, while keeping the street fabric and building low-rise. Alexandra Road Estate (075) is one of the most ambitious housing projects of its time. The concrete megastructure, stretching 300 metres along the railway line, has stepped terraces, forming a ziggurat-type structure.

075 Alexandra Road Estate

Neave Brown

1978

1978  NW8 0SN

NW8 0SN

This permits every flat direct access to the ‘street’, which cuts across the complex and is overlooked by residents’ windows. As a result, the estate had the lowest level of vandalism in the entire borough. Unfortunately, unforeseen issues with the foundations and extraordinarily high inflation rates in the 1970s tripled the costs. A public inquiry into the project revealed that Brown was not responsible for the spiralling costs, but his reputation in Britain nevertheless took a major hit. Unable to find work, he turned to projects in the Netherlands. Thankfully, his genius was reappraised, and forty years later he became the first architect in Britain to have all of his buildings listed.

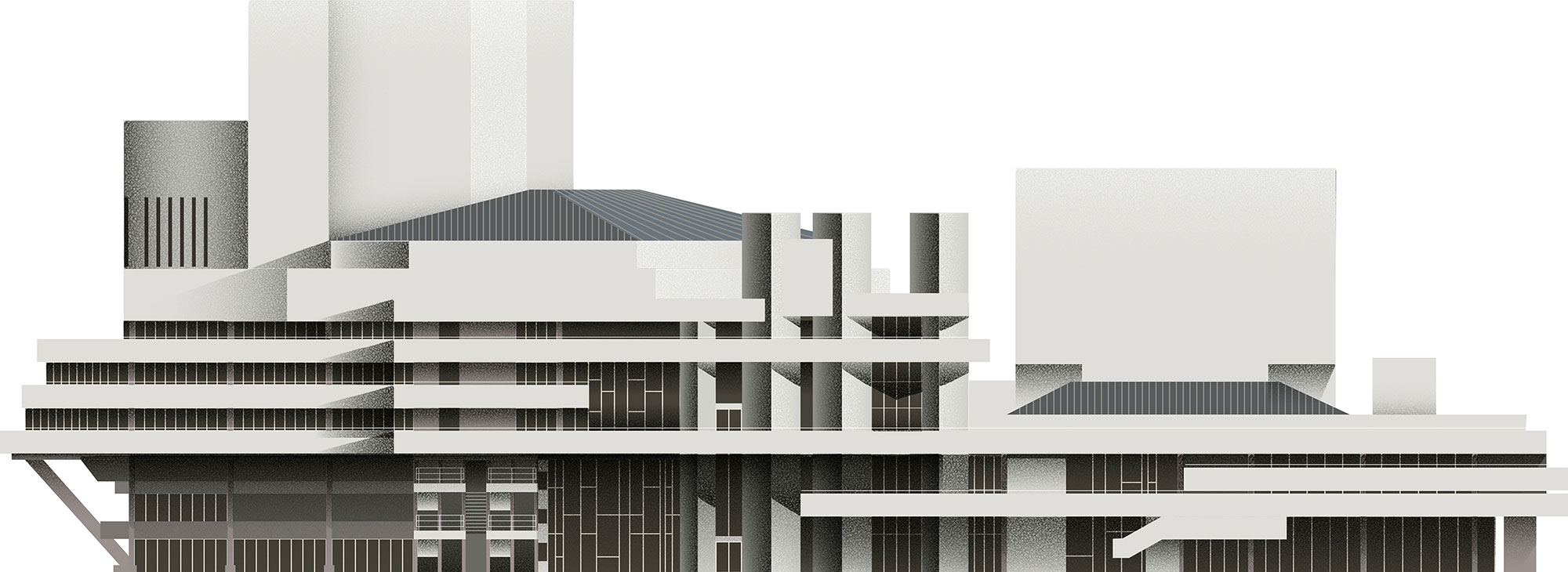

Cultural buildings bloomed in the 1970s, particularly libraries and theatres. Plans for a new National Theatre for London had been in place since the end of the Second World War, and in 1951 a foundation stone was laid on the South Bank. However, problems with funding meant the construction didn’t start until 1969. A board of theatre directors, designers and technical experts was set up to select an architectural team. The board met with many different studios, each of whom brought a large team of experts in a bid to prove their worth and experience. Denys Lasdun was the only one to show up alone, and he reportedly confessed to knowing very little about theatre design.

Nevertheless, his vision and notorious persistence in the study of design and function impressed the board enough that he was selected. Lasdun spent more than a decade researching, designing and building the National Theatre (076). It consists of three separate auditoria, which are loosely based on theatre designs from the greatest periods of drama – namely classical Greek theatres, Tudor inn-yards and more modern theatres of the preceding three centuries. The architect compared the design process to planning a small city, in which a number of elements need to work together.

076 National Theatre

Denys Lasdun

1976

1976  SE1 9PX

SE1 9PX

Some of his solutions were unorthodox though, and had to be amended in subsequent years. The exterior is characterised by vertical stage towers (that hide a rope system for each stage) and a sequence of horizontal terraces. Prince Charles, of course, felt obliged to comment and compared it to a nuclear power station. It was too modern for some, but for architecture critics it was outdated. In 1976, concrete was already out of fashion and buildings so bold and confident seemed inappropriate in a time of economic uncertainty. But today it is seen by many as a brutalist masterpiece shining with high-quality craftsmanship.