Introduction

This book is based on the principles of marlinspike seamanship, a term used in the marine trades to describe rope work, wire work, and knots. Sailors use practical marlinspike seamanship skills to make, customize, or fix a boat’s running rigging, anchor lines, docklines, and other ropes and wires used to operate a boat and keep the crew safe.

Sailors also use their marlinspike seamanship skills to make decorative items, called “fanciwork.” A sailor might employ fanciwork to decorate his ditty bag or sea chest. He or she might tie a wide, flat sennit (braid), or a series of knots to serve as a lanyard for a belt or knife, or tie a decorative flat knot to use as a trivet or doormat.

Earth-Friendly Shellacking

When it was first suggested to me that I write an earth-friendly knot book, I thought to myself, how easy! Knot tyers the world over have been demonstrating their skills for hundreds of years in leather, cotton, hemp, and colorful silks. However, one small but important part of knot tying almost stopped me in my quest: what to use for glue and coating? I’ve always loved shellac, but how could I get around the use of denatured alcohol? What did the artisans of old use in place of the toxic stuff? I realized that I needed to use a different form of alcohol. Feeling a little weird, I explained what I was searching for to the first clerk in the first liquor store I happened upon. Nancy Laboissonniere listened to me carefully, and when I finished my story she stepped from around the counter and disappeared down the aisle, a moment later returning with a bottle of pure grain alcohol in her fist.

“This will do it,” she explained.

All I could say was “Wow, how do you know this?”

“I have a masters degree in clinical laboratory science from the University of Rhode Island,” she answered.

I’m delighted to report that grain alcohol works better than denatured alcohol for dissolving the shellac flakes.

Grain alcohol can be used instead of denatured alcohol when working with shellac flakes, making the entire process much more enjoyable.

The overhand knot is the most common knot and serves as the base for many more complex knots.

The square knot has many practical purposes.

What I call a package knot is kind of a nick name. The sailors (and others in the trade) tie the first part of the square knot with an extra turn–that way one can tie the rest of the square knot without asking someone to hold it with their finger so it won’t slip. The package knot is a binding knot. A true package knot is tied completely differently.

If you look around, you will see knots everywhere and tied into all sorts of strings and ropes: the overhand knot used for sewing, the bow knot used to tie shoelaces, the square knot used to bundle newspapers or branches for recycling. This book focuses on using simple knots such as these to make both practical and decorative projects.

We start the book with two basic knots, the Turk’s Head knot (described in Chapter 1) and the square knot (described in Chapter 2). Square knotting might bring back memories of 1960s crafts or Boy Scout or Girl Scout projects. Those who have served on maritime duty might know the square knot as the one used in McNamara’s lace. The square knot with a minor manipulation turns into a surgeon’s knot. The Ashley’s knot #2216 is a highly decorative knot. You’d want to use it as a knob covering—perhaps a gearshift knob or a knob at the end of a tiller. This knot is described in Chapter 3.

Overhand knots arranged in a special way turn into a trucker’s hitch that will hold a bundle of branches effortlessly. The overhand knot is also the starter knot for netting, described in Chapter 5.

There is a saying that perfectly reflects the theme of this book: “What’s old is new again.” All knots begin with a piece of rope or cordage, and Chapter 9 explains how to make rope and how to use this homemade rope in several projects. (See the Choosing Cordage section in this chapter for advice on purchasing cordage.) Ropes and cordage have been made like this since the time of the Pharaohs. Lengths of cordage or rope twisted from papyrus fibers have been found in Egyptian tombs. Shellac, used as a coating in some of the projects in this book, was used as a finish for wooden items in China since the time of the Emperor Tang.

Many of you will recognize the patterns that I used for the projects in this book. My variations on these patterns include a small ocean plat knot sewn to embroidered canvas to make an eyeglass case (Chapter 7). I also created an Altoids tin cover based on a cigarette case pattern from the Encyclopedia of Knots (Chapter 2), which I couldn’t have done without the help of another knot tyer, Marty Casey. I’m awfully proud of the rope hammock as well (Chapter 13). Hammocks that are tied rather than woven are usually really uncomfortable, but my hammock is both lovely to look at and comfortable to lie in.

I think you’ll find that this book covers the basics, with projects for young and old and the expert or novice knot tyer. All the projects are handsome and useful in an earth-friendly way.

NOTE: By no means do these projects demand cotton, leather, manila, or rayon. They can be easily tied in corresponding-size synthetic material. Use the flame from a lighter to fuse the ends of synthetic cordage. Instant glue from the tube will hold ends together nicely, and a coating of polyurethane will harden, seal, and add shine to your work, if desired.

Choosing Cordage

I think just about the best thing in the world is to curl up with a good book. I like the real kind–carefully crafted with hard covers front and back, nice paper pages, and easy-to-read print. But I also love my e-reader. Almost every evening before I go to sleep, I prop it up right in front of me and turn the pages with just a light push. Reading the printed word in either format makes me happy and content.

I feel the same way about today’s cordage—thankful for the longstanding natural material and simultaneously appreciative of the possibilities offered by the new materials. In Chapter 5 I focus on projects from the net knot, for example. I’d use a natural fiber to make the net knot string shopping bag. Isn’t that the idea—to replace the plastic ones? But if I used the bag to carry clothes to and from the laundromat, I’d make it from synthetic cordage, which is tough, light, and quick-drying. It’s nice that we have a choice between natural and synthetic cordage, because it hasn’t always been the case; synthetic cordage first appeared in 1938.

Cordage is as elegant as it is simple. Groups of individually twisted strands are themselves twisted around one another in the opposite direction. The finished product is a bundle of interlocking tension, with each strand holding another in check and keeping the entire rope from unraveling.

The quality of the cordage depends on the number of levels of interlocking twists, the quality of the fundamental material (the length of the “staple” in natural cordage, and the chemical makeup of synthetic cordage), the consideration given to twist tension (or braid), and whether the cordage is finished properly. Synthetic cordage is heat set—the last step after the cordage is twisted is passing it through an oven. Other cordage is often coated with a wax or, in the case of natural fiber ropes or twines designed for uses on a farm, often impregnated with rodent repellent. Interesting enough, special synthetic rope designed to be used in trucking is impregnated with chemicals that repel UV rays.

Naturally, cordage made with more care costs more. I hope that all who decide to purchase cordage for a project in this book will not use cheap or used string. Even the most skilled knot tyers are doomed and destined to produce a less than perfect result if they choose poor quality cordage.

Understanding Materials and Measurements

Here are the two “M”s of cordage for projects in this book: material and measurements.

These are the materials I used to make different projects in this book:

I use cotton in the seine twine and cotton rope projects, including net knot bags (Chapter 5), monkey’s fist projects (Chapter 4), and square knot projects (Chapter 2).

I use cotton in the seine twine and cotton rope projects, including net knot bags (Chapter 5), monkey’s fist projects (Chapter 4), and square knot projects (Chapter 2).

I use manila (also called abaca) in doormats (Chapter 7).

I use manila (also called abaca) in doormats (Chapter 7).

I use cotton rope for the companionway stair treads (Chapter 7).

I use cotton rope for the companionway stair treads (Chapter 7).

I use rayon and leather to make the knotted jewelry in Chapter 10.

I use rayon and leather to make the knotted jewelry in Chapter 10.

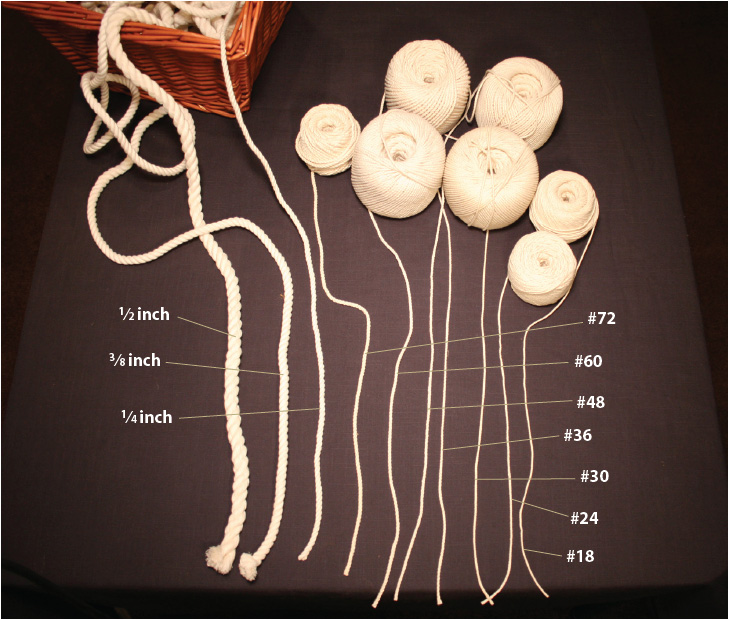

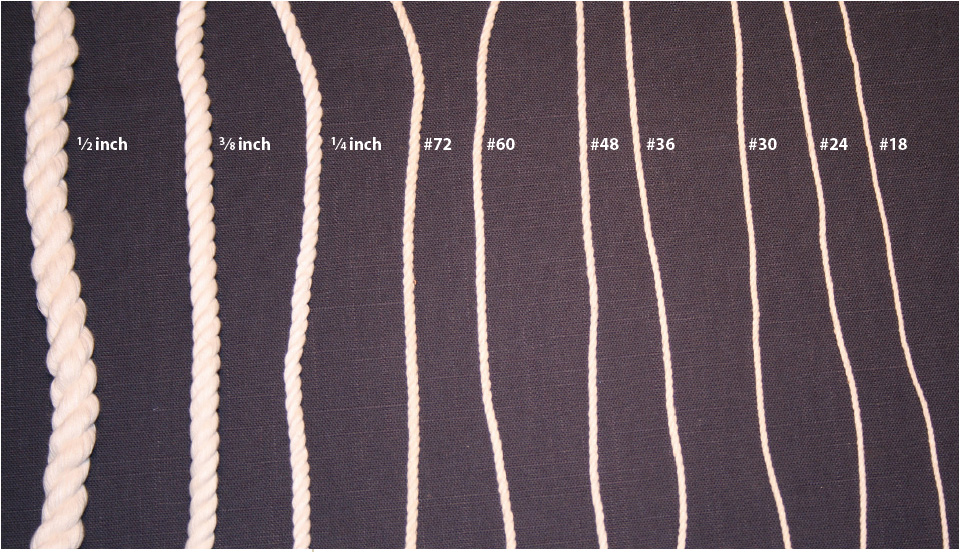

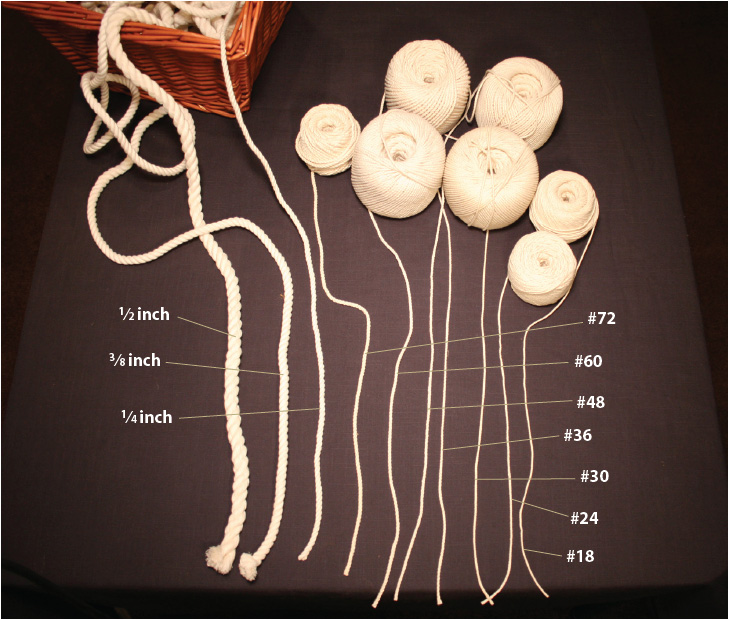

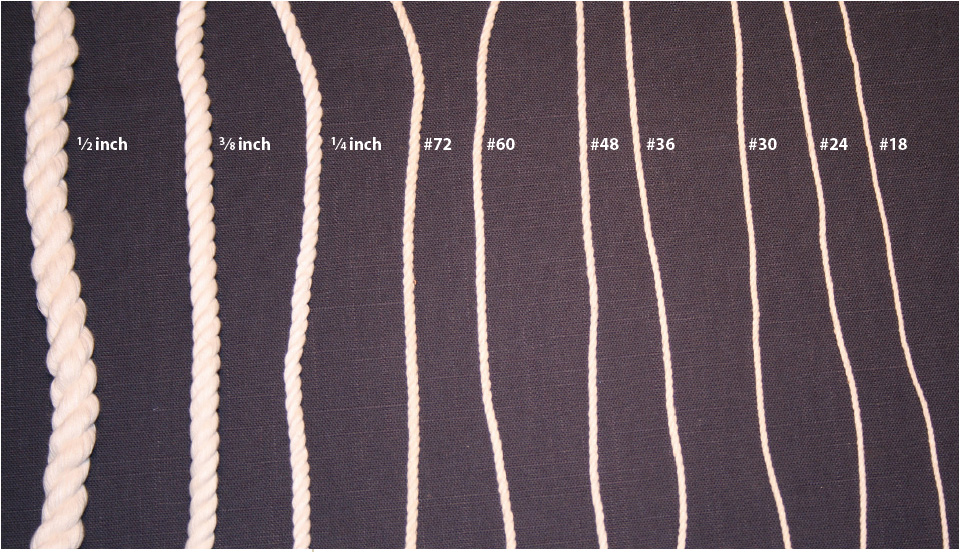

Thinner cotton seine twine is measured by the number of threads it contains. Shown here is cotton seine twine from #18 up to #72. Thicker cotton rope is measured in inches, shown here from ¼ inch up to ½ inch.

Measurement information holds true for either natural or synthetic cordage. For our purpose let’s examine a favorite of mine, #48 cotton seine twine. The “48” means that it is made of 48 threads of cotton. The #18 cotton seine twine is about half as big, and the #84 cotton seine twine is twice as big as #48 cotton seine twine. After #120, cotton seine twine measurements “morph” into inches, and cotton seine twine becomes cotton rope. For the sake of simplicity, I chose projects using manila (abaca) fibers in rope form because projects using this stuff are measured in inches. Also, be aware that cotton rope is very expensive—so the knot tyer will want to take this into account. Can he or she execute the project in the less expensive (but still natural) fiber rather than out of the very expensive cotton rope?

If you choose to craft your project from one of the natural fiber ropes, you’ll need to protect it from damp, mold, mildew, and small rodents. If you make the ditty bag out of canvas (see Chapter 13), you’ll also need to protect your project from chafe. Any bag rubbing against woodwork or a cabin bulkhead in time will become worn in that spot.

Projects made from synthetic seine twine or rope are generally impervious to damp, mold, mildew, and small rodents. For the most part, synthetic stuff is tough and will hold up well.

Sources of Materials

I purchase my materials from the following places of business. Foremost in my mind are these criteria: value for my dollar, availability of the product, consistency of the product, customer service, and the company’s knowledge of the product.

Wilcox Marine Supply 30

Wilcox Road

Stonington, CT 06378

(860)536-4206

My favorite, a family owned business.

R and W Enterprises

http://rwrope.com/

Memphis Net and Twine

http://www.memphisnet.net/

La Stella Celeste, Inc.

5130 Abel Lane

Jacksonville, FL 32254

http://stellaceleste.com

(Rayon Supplier)

www.satincord.com

1-888-728-8245

Finish Supplies

www.shellac.net

Good quality, nice people, too.

Tandy Leather

http://www.tandyleatherfactory.com/

I use cotton in the seine twine and cotton rope projects, including net knot bags (

I use cotton in the seine twine and cotton rope projects, including net knot bags (