“Every perfect work is the death mask of its intuition.” Returning finally to the epigraph that set this book in motion, we are reminded that Walter Benjamin tried out his lapidary thought in January 1924 in one among several letters on art, history and criticism to his intellectual confidant, Florens Christian Rang. And then, as if to exemplify the wisdom of what he wrote, he cleansed it in revision, making it over into something less daring. “The work is the death mask of conception,” he now wrote, as the final entry in “The Writer’s Technique in Thirteen Theses,” in the miscellany published as Einbahnstrasse in 1928.1 Benjamin draws back now from the extremity of perfection. The mysteries implicit in intuition give place to conception, decidedly less mysterious, more rational.

Characteristically, Benjamin set his sights on a moment that can never click into focus: the unimaginable moment during which idea (and, by extension, art) is imagined—in which the intuitive is transfixed as text. Benjamin’s Death Mask invokes the moment at which this elusive, ephemeral, wavelike process of creation is spent: what remains is called the Work. The spontaneity, the play of creation is over. The vitality of making gives way to artifact. The fluidity of composition, the act of creating, is stopped, petrified in the formal construct that more readily responds to cognition and analysis. But this moment at which text is fixed and intuition silenced is a phenomenon fraught with imponderables of its own.

It was during these troubled and productive years that Benjamin produced the imposing, often impenetrable essay on Goethe’s Wahlverwandtschaften (Elective Affinities), the act of reading made into a Probestück in search of a genuine criticism over against the literal commentary that conventionally bore the name.2 If the latter describes the material content of the work, the former goes after its truth content. Having suggested that the history of the work prepares for its critique, and that historical distance consequently increases the power of such critique, Benjamin conjures this extravagant simile: “If one views the growing work as a burning funeral pyre, then the commentator stands before it like a chemist, the critic like an alchemist. Whereas, for the commentator, wood and ash remain the sole objects of his analysis, for the critic the flame itself alone preserves an enigma: that of what is alive. Thus, the critic inquires into the truth, whose living flame continues to burn over the heavy logs of what is past and the light ashes of what has been experienced.”3

Why Wahlverwandtschaften? If one were casting about for a work whose living flame illuminates an enigma, Goethe’s riddling novella, in its meshing of timeless parable and contemporary romance, makes the short list. However we think to reconcile the symmetries and alignments of its plot, the invertible counterpoint that its characters perform and the themes of morality and art that control the discourse, there is yet one aspect of the work that remains supremely and intentionally unintelligible, and it has to do with the figure and image of Ottilie, whose obscure, expressionless beauty, somewhere between puberty and maturity, is only affirmed in Goethe’s text but never described in conventional literary detail. Her beauty is not of this world. She comes then to signify beauty in some abstract sense, at the margins of experience. Indeed, it is through her eyes that Ottilie is represented in her singular and curious engagement with her environment. When for the first time she holds the infant son born to Charlotte, her aunt and protectress, she is “startled to see in his open eyes the very image of her own.”4 The curiosity of such a revelation would hint strongly of irony—in the first instance because Ottilie bears only a remote kinship to little Otto, and in the second because the eye, in its optical essence, is not an element of which we are cognizant in our own physical appearance: it is absolutely unrevealing in itself. And yet the meeting of eyes suggests, as does no other human (or even animal) conduct, a deeper contact: an intimacy of inner beings, of souls. There is no irony here. The magnetic, mystical force of Ottilie’s eyes are made a pronounced theme. The eye of Ottilie seems to stand for some mystical quest toward the idea of beauty, in the paradox of sensual love and abstract, formal beauty, and finally, in the notion of a pure beauty without expression—indeed, without life. In her gradual withdrawal from the world, Ottilie lapses into utter silence and finally, a self-willed death. On the funeral bier, her beauty takes on an ethereal aspect. In a “state resembling rather sleep than death,” as Goethe puts it, her attraction becomes even more magnetic.5

Wahlverwandtschaften is about many things, not least about the imponderable mysteries of art and beauty. How does the critical mind come to grips with such a work? This, it seems to me, is the problem that consumed Benjamin. For while his essay, too, is about these other aspects of Wahlverwandtschaften, at the end of the day it is about the nature of the beautiful, and the critic’s access to such abstractions.

Benjamin makes only the briefest and most riddling references to music, and they seem to stand at the last outpost of the knowable, at the leap into the world beyond cognition. They come toward the end of the essay, the first of them in the midst of a tortuous hunt for the location of beauty in semblance and in essence. “Everything essentially beautiful,” he writes, “is always and in its essence bound up, though in infinitely different degrees, with semblance.”6 In the intensity of the ensuing interrogation of the Platonic idea of the beautiful, semblance and essence, intimately fused in the work of art, are pulled apart:

Beautiful life, the essentially beautiful, and semblance-like beauty—these three are identical… . An element of semblance remains preserved in that which is least alive, if it is essentially beautiful. And this is the case with all works of art, but least among them music. Accordingly, there dwells in all beauty of art that semblance—that is to say, that verging and bordering on life—without which beauty is not possible. The semblance, however, does not comprise the essence of beauty. Rather, the latter points down more deeply to what in the work of art in contrast to the semblance may be characterized as the expressionless; but outside this contrast, it [this essence, he must mean] neither appears in art nor can be unambiguously named.7

All of which leads to this ultimate arcanum: “Never has a true work of art been grasped other than where it ineluctably represented itself as a secret. Since only the beautiful and outside it nothing—veiling or being veiled—can be essential, the divine ground of the being of beauty lies in the secret.”8

This semblance, this expression, which is a necessary veil that obscures the “essentially” beautiful is perceptible even at those extreme points of abstraction—the work stripped down to its core—where nothing seems to reside but the essentially beautiful itself. But these traces of the veil, of life, of expression are least of all present in music. In that sense (if I am grasping the implications of Benjamin’s obscure reference), music is the art that comes closest to conveying the purely, the essentially beautiful.

For Benjamin, the deepest expression of the mystery of the novella is couched in that luminous phrase through which Goethe captures the doomed moment of final embrace between Ottilie and Eduard: “Hope soared away above their heads like a star falling from the heavens.”9 And this inspires the apotheosis in Benjamin’s critique:

… the symbol of the star falling over the heads of the lovers is the form of expression appropriate to whatever of mystery in the exact sense of the term dwells within the work. The mystery is, on the dramatic level, that moment in which it projects up, out of the domain of its own language into a higher and unattainable one. Therefore, this moment can never be expressed in words but is expressible solely in representation: it is the “dramatic” in the strictest sense. An analogous moment of representation in the Wahlverwandtschaften is the falling star. To its epic foundation in the mythic, its lyrical breadth in passion and affect, is joined its dramatic crowning in the mystery of hope. If music encloses genuine mysteries, it remains thus in a mute world from which its reverberations will never sound forth.10

In a passage fraught with mysteries of its own, music is invoked as an encrypted language that might yet illuminate something of this leap from the purely linguistic to that other realm, “nicht erreichbaren,” this moment–“dramatic in the strictest sense”—that can never be expressed in words. What is it, precisely, that Benjamin attributes to music, in its concealing of mysteries that can never be sounded forth? Perhaps, that in music the representational—the symbolic, in Benjamin’s highest sense: the extralinguistic—is inseparable from its linguistic basis. Its mysteries remain embedded in the notes.

These days, it might be thought quaint to engage in such talk of essences and Beauty. And yet it seems to me that in these imponderable reflections Benjamin is worrying more than a definition of Beauty: there is a playing out that has to do with the place of works of literature—of Art—in a Europe, in the 1920s, where a concept of beauty as a last frontier of meaning, and therefore of genuine culture, had become estranged from the increasingly politicized banalities of Kultur.

Not too many years earlier—in 1911—Thomas Mann grappled with this estrangement in the conceiving of Der Tod in Venedig, a novella whose mystical quest toward the idea of beauty seems now and again to echo the haunting themes of Goethe’s Wahlverwandtschaften, a work which Mann himself claimed to have read through no less than five times in the course of his own writing during that Venetian summer.11 More than that, in its density of thought, the writing often seems to prefigure Benjamin’s efforts to get at the nub of Goethe’s veiled meaning. Beauty is approached through a vision in which two figures, one elderly and one young, one ugly and one beautiful, turn out to be Socrates and Phaedrus. The famous dialogue is not of course cited in any literal mode, but remembered, half-dreamed, through a distorting lens. These passages are no less about the “essence” of the beautiful than are Benjamin’s, though perhaps it might be suggested that Mann and Benjamin begin at different points on the axis and end up again at opposite ends.

The aging Gustav von Aschenbach undertakes his self-willed journey of the soul from a priestly aesthetic station: aloof, distant, classicizing, perceiving beauty in the idealized abstractions of form. His first aperceptions of the Polish adolescent beach boy are as of frozen sculpture, like Winckelmann’s views of Greek antiquity. Tadzio is caught in posture—evoking those friezelike tableaux vivants at the outset of Book II of Wahlverwandtschaften. Gradually, in a studied degeneration of the soul that Mann so painstakingly calibrates, Aschenbach succumbs: to the sensual, the erotic, the forbidden. And everywhere, this is coupled with images of decay, of disease, of masks (Aschenbach in the barbershop–hauntingly portrayed in Visconti’s film)—and of death.

At a critical turn in Der Tod in Venedig, inspired now by the physical presence of Tadzio on the beach and resolved to capture in prose—to possess, through an act of writing—the fusion of Beauty and Eros that his figure embodies, Aschen-bach is consumed in this overwrought reflection:

The writer’s joy resides in the thought that can become feeling, feeling that can merge wholly into thought. Such a pulsating thought, such precise feeling possessed the solitary Aschenbach at that very moment: namely, that Nature trembles with rapture when the spirit bows in homage before Beauty.12

This epiphanous moment seems very close to just such a moment in Goethe’s novella. Ottilie has been fixed in posture, statuelike, as the Mother of God in a tableau-vivant on Christmas eve. A thousand thoughts pass like lightning through her soul in these frozen moments:

With a celerity with which nothing else can be compared, feeling and thought reacted one against the other within her. Her heart beat fast and her eyes filled with tears, while she strove to stay as still as a statue.13

Aschenbach, unlike Ottilie, translates his ecstatic moment into prose:

Never had he known so well that Eros is in the word, as during those perilous and precious hours when he sat at his rude table, within the shade of his awning, his idol full in view and the music of his voice in his ears, and fashioned his little essay after the model Tadzio’s beauty set, that page and a half of choicest prose, so chaste, so lofty, so poignant with feeling, which would shortly inspire the admiration of his readers. Certainly it is a good thing that the world knows only the beautiful work, and nothing of its sources, of the circumstances of its origin; for a knowledge of the springs from which the artist’s inspiration flowed would only confuse and intimidate it, and thus compromise the effects of its excellence.14

Then comes the poignant collapse:

Strange, curious hours! Strange, unnerving labor. How mysterious this act of intercourse and begetting between a mind and a body! When Aschenbach put away his work and left the beach, he felt exhausted, even broken, his conscience reproached him as though after a debauch.15

There is more than a whiff of irony in this transparent, furtive sighting of the shuddering moment at which art is born, even as Mann, through Aschenbach, protests the irrelevancy of such intimate knowledge to the appreciation of its beauty. And yet he wants us to know. He insists that we know. His work completed, the Aschenbach who comes up from the beach is spent [“erschöpft”]. The perfect work is the Death Mask of its intuition. In his little scena on the beach, Aschenbach act outs, dramatizes as though in parable, Benjamin’s conceit.

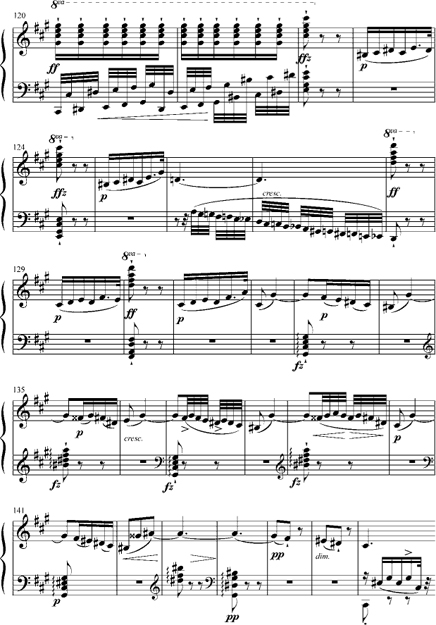

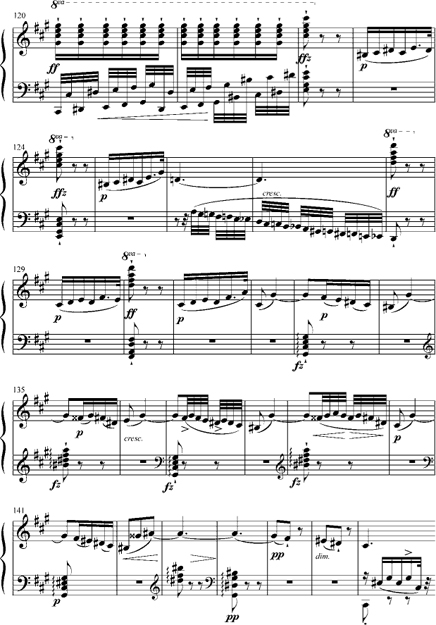

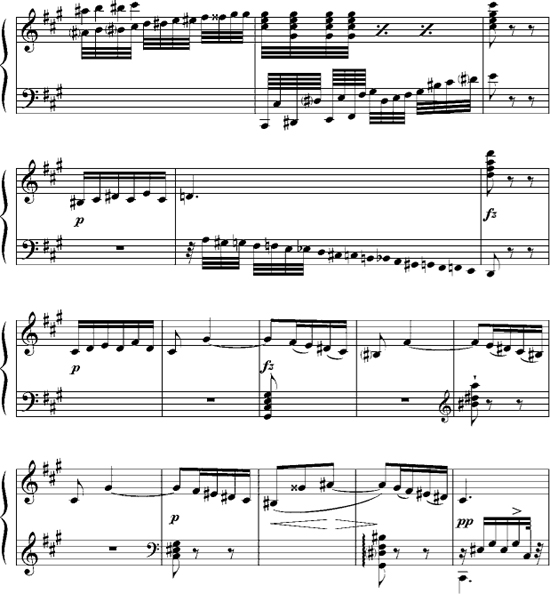

This constellation of thought around the capturing, phenomenologically, of the moment of beauty comes alive for me in the image of a passage in the Andantino of Schubert’s Sonata in A major (D 959) of 1828. Hearing a performance of this music suggests how Benjamin’s sense of the finished work, of a text, implicates performance as well: the performance, we might propose, in its realization, is itself a mask, emulating the process of mind that creates the text—acts out, that is, the life/death that Benjamin’s definition of the work seeks to capture. This is not in any sense to suggest that the work itself “exists” only in such realizations. Rather, the phenomenon of performance excites us (as performers) because we reenact, each time uniquely, this intuitive process that the text suggests of its origins.

Schubert did not often leave behind the concrete evidence of such a process. But a draft for this movement has survived, and it has much to tell us.16 (See ex. 15.1.) The placing of these two documents side by side will invariably inspire narratives toward a theory of “creative process”: by one such script, the draft is shown to be but a naive, precritical glimpse at an idea not yet “perfected.” In another, the draft is valued as a thing in itself, as rare evidence of primary, primal thought: fleet, spontaneous, unmediated by the meddling critical mind. To dismiss out of hand either or both of these views of the draft would be to miss something of value that each has to offer. And yet they are inadequate, and in this sense: to the written document is ascribed in each instance a fixity that traduces the complex privacy of creating—the silent internal colloquy, the torment, the euphoria, the play that is innate in it; a fixity that does not recognize the fluency of a dialectics that flow in the time and space between and around the documents. Construed as something definitive and finished, fixed in its notation, the document, whether of a draft or a sketch or of some perfected “final text,” is made over into a mask that obscures the process of mind behind it.

This, however, does not get us very close to the funeral pyre that Benjamin conjures. Where is the truth content of this music? Where is its beauty? We follow Benjamin in the quest to separate out the luster, the appearance, the expression of beauty from something at once more abstract, more enigmatic, less open to cognitive grasp or visceral perception. We revisit the draft, its music telegraphically concise almost to a vanishing point. Is this really how the idea came to Schubert? Is the idea, in its irreducible essence, more closely captured in the draft, stripped of all semblance of the expression—of the poignancy of human utterance—that moves us in the music that we all know? These are impossible questions, but in the asking, they expose the folly in trusting that we can nail down, cognitively, some identifiable moment in which the work coalesces. The problem seems to me at one with the Benjaminian riddle of an essential beauty that grows increasingly inaccessible as it is approached. If there is an essential beauty—some essence that allows of apperception—it won’t be found reified in the ultimate distillation that we theorists are forever burning out of the notes. Perhaps we must be content to imagine it, mysteriously inaccessible, embedded in the incessant play between faceless, formal abstraction and irrational, fallible expression.

EXAMPLE 15.1 Schubert, Sonata in A major, D 959, Andantino.

A Published version.

B Draft, Vienna: Stadtbibliothek, MH 171/c.

Surely, it is a mistake to seek answers in the apparent opposition of draft to finished work. There is in effect no opposition here, but rather a fluid process of mind, hopelessly dialectical, obscure to the point of blankness. Benjamin provokes us to penetrate this impenetrable process, of which the draft captures but a single, fragmentary phase. It is not in the nature of the thing that we can ever succeed in the quest to locate that ineffable moment in the process at which Schubert will have found the “essentially beautiful” in this music. The moment itself—Goethe’s falling star—vanishes, as moments do, and we are left with the “vollkommene Werk,” and all that it masks.

The porous boundary between the work, in what Benjamin calls its truth content, and what the author confides as to its meaning was of great concern to Benjamin. “To wish to gain an understanding of Elective Affinities from the author’s own words on the subject is wasted effort, ”he writes. “For it is precisely their aim to forbid access to critique.”17 The second part of Benjamin’s essay, now in close scrutiny of this boundary, opens with a set of maxims on the reading of the author in the text—and here I must again quote Benjamin: “The sole rational connection between creative artist and work of art consists in the testimony that the latter gives about the former.” And, finally: “Works, like deeds, are non-derivable.”18

Those “anderthalb Seiten erlesener Prosa” written by Aschenbach on the beach were years ago identified as the brief essay titled “Auseinandersetzung mit Richard Wagner” (Coming to Terms with Richard Wagner), a manuscript that bears the letterhead of the Grand Hotel des Bains, Lido-Venise (Aschenbach’s hotel) and is dated May 1911.19 In the essay, Mann is very hard on Wagner’s theoretical writings, which he finds absurdly untenable. He doubts whether anyone actually reads this stuff. “Is it,” he wonders, “because his writings are propaganda rather than honest revelation? Because their comments on his work—wherein he truly lives in all his suffering greatness—are singularly inadequate and misleading? There is not much to be learned about Wagner from Wagner’s critical writings.”20

I call up the essay on Wagner for two reasons. For one, it worries this difficult question on the abuse of the author’s privilege that Benjamin worries with Goethe. For another, the Wagner essay is itself implicated in just such a relationship, for the critic who is tempted to reveal the identity of Aschenbach’s burnished prose will invoke the circumstantial evidence that implicates the Wagner essay. This is what I meant in referring to a porous boundary between work and author. There is much in the little Wagner essay that resonates sympathetically with the aesthetic problem in Der Tod in Venedig, and perhaps most notably, the opposition of Eros and classicism; even the “Auseinandersetzung” of its title is suggestive in this regard.21 If we cannot know, if we are meant not to know, what it was that Aschenbach was writing on the beach, we can yet allow these two works, the essay on Wagner and the novella, to continue to resonate sympathetically, taking care, as we must, to respect the autonomy of their texts.

To mask is to disguise, to conceal, to obfuscate. But in an age before photography, the death mask sought to preserve the features of its subject in perfect fidelity: to reveal. Benjamin’s metaphor is thus shrouded in further paradox, for if the finished work is a mirror held up to an intuition now vanished, it remains the only evidence of that intuition. It masks in these two contradictory senses, concealing, altering, disguising the throe of intuition even as it reveals, limits, sets the work in some formal language that allows of its apprehension. The death mask stands neither for the work nor our response to it, but for something less specific: a process, perhaps, internal to the creation of works, a mirror held up to the inner consciousness of the artist. How to figure this image in our efforts to write histories of art—to do criticism—is the difficult challenge that is Benjamin’s legacy.