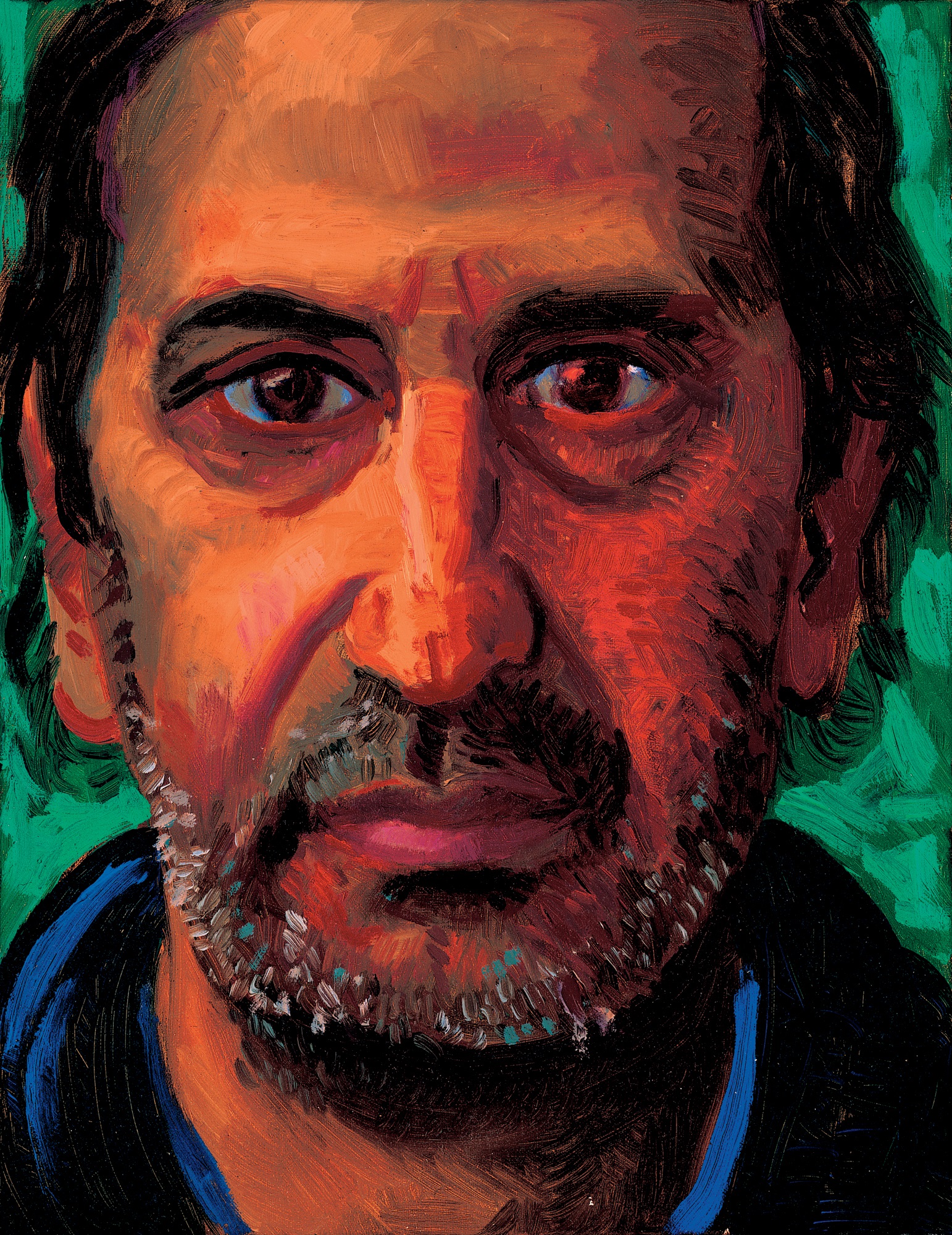

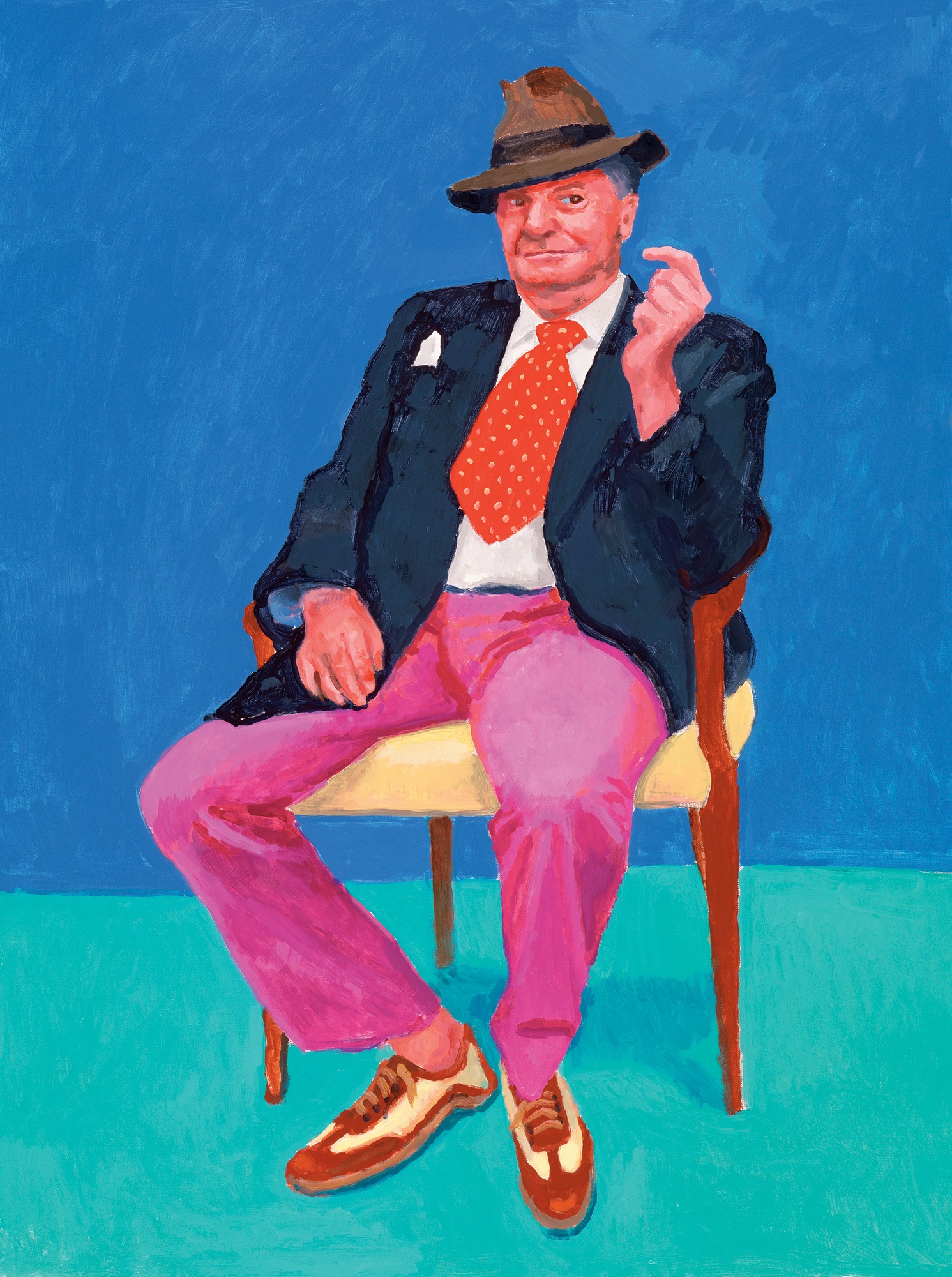

208 Jonathan Silver, February 27, 1997, 1997

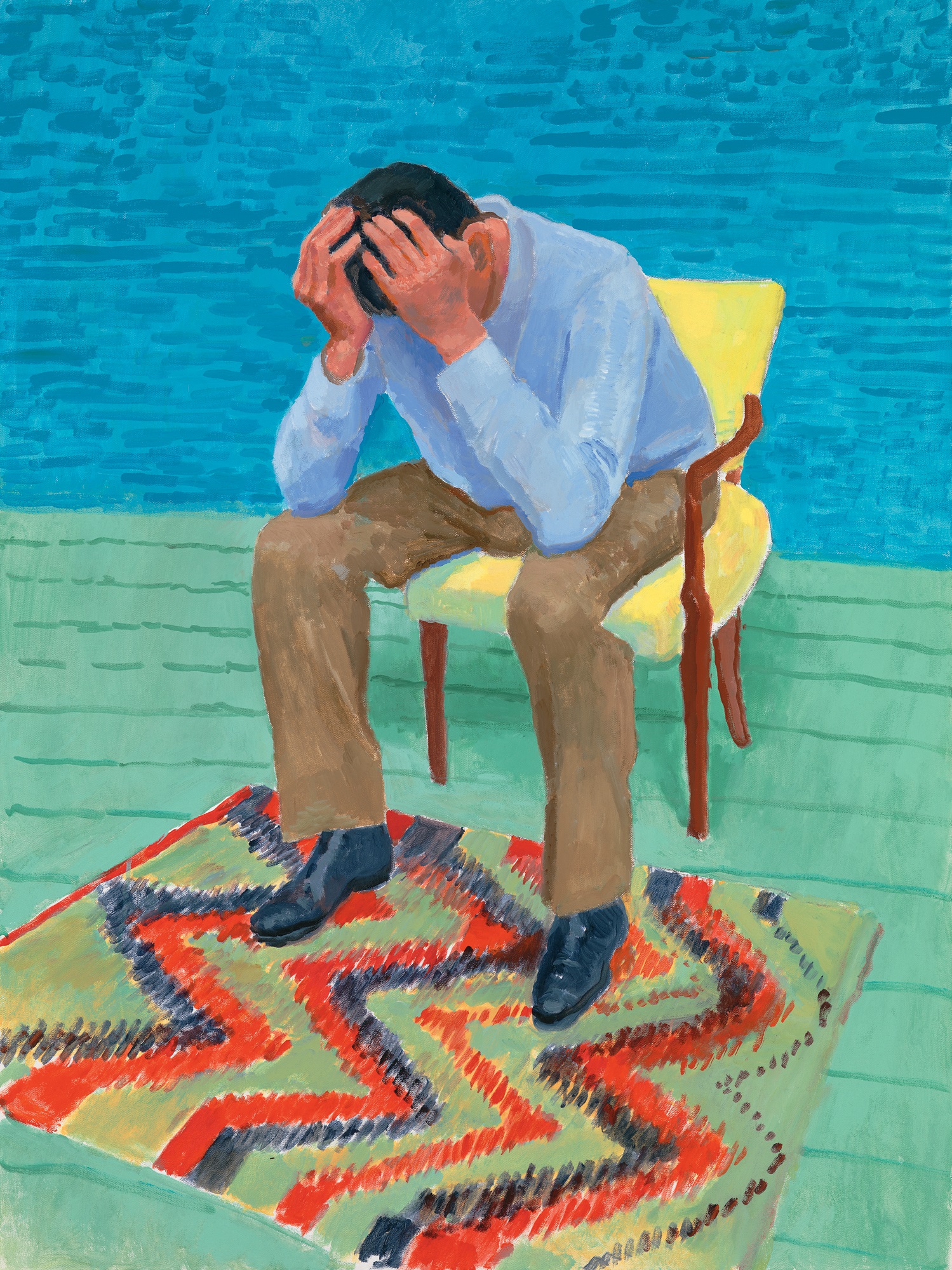

For a combination of personal and professional reasons, in the late 1990s Hockney began again, for the first time in many years, to spend much more time in the UK. He had been drawn back to be by the bedside of his great friend Jonathan Silver, who had established a gallery devoted exclusively to the display of Hockney’s work, the 1853 Gallery at Salts Mill in Saltaire, just outside Bradford. On hearing that Jonathan was laid low by cancer (from which he eventually died in November 1997), Hockney rushed to Yorkshire in summer 1997, having made more frequent trips there in recent years, this time staying for several months in the house he had bought less than a decade earlier for his mother and sister in the seaside town of Bridlington. From there he made daily journeys by car to visit his friend on the other side of York.

During 1996 and 1997, wherever he found himself, Hockney made small head-and-shoulder portraits in oil on canvas of family and friends, mostly in the same small format that enabled him to represent their heads more or less life-size. The format was a familiar one to him, since he had used it in 1988 to make a similarly extended series of portraits painted quickly from life [189], but these new pictures were more sombre in their colour schemes and more violently, even expressionistically, brushed. A selection of twenty-seven of these was shown between May and July 1997 at Annely Juda Fine Art in London as part of his exhibition ‘Faces and Spaces’; one of the two volumes of the accompanying catalogue was devoted exclusively to these works. Despite the use of heated colour, with many of the faces showing a ruddy complexion, the psychological tone of the paintings is solemn, even at times despairing. This is understandable given the shadow of death then hanging over some of the sitters, particularly in the case of Silver [208], in temporary recovery after his first treatment for cancer, and Hockney’s mother, Laura. Strong contrasts of colour are used to model the heads three-dimensionally, the powerful lateral lighting serving to project each person’s features with a moving physical presence.

The message is clear: these people are alive, seated or standing a very short distance away, often fixing us with an unblinking gaze. There is a sense of an electric, unspoken communication between sitter and artist and therefore by extension between sitter and viewer. Several portraits of the artist’s mother in her bed, made during the same period but not included in the Juda exhibition, are perhaps the most haunting of this group of paintings. Mum Sleeping, 1st Jan. 1996, 1996 [209], is one of the most affecting of these confrontationally direct, brutally honest portraits of loved ones. Laura had turned ninety-five a month earlier and was in a particularly fragile state. The morning after her death on 11 May 1999, Hockney confided to me that ‘until yesterday I always knew exactly where my mother was. If I wanted to have a chat with her I could phone her and she would drop whatever she was doing to talk to me.’ Laura had long been one of his most patient and obliging sitters, and the person who in the past had elicited from him his most sensitive responses. Coming so soon after the colourful and sometimes rather forced cheerfulness of the Very New Paintings and other abstract landscapes of the early 1990s, the portrait’s tone of melancholia, resignation and physical suffering produces something of a shock, but there is also a great tenderness in the way Hockney has captured his mother’s determination and endurance, and not just her physical frailty. Her hands, gnarled and crippled by arthritis, adopt ungainly and highly expressive postures at right angles to her wrists, as if on the point of being severed from her body.

208 Jonathan Silver, February 27, 1997, 1997

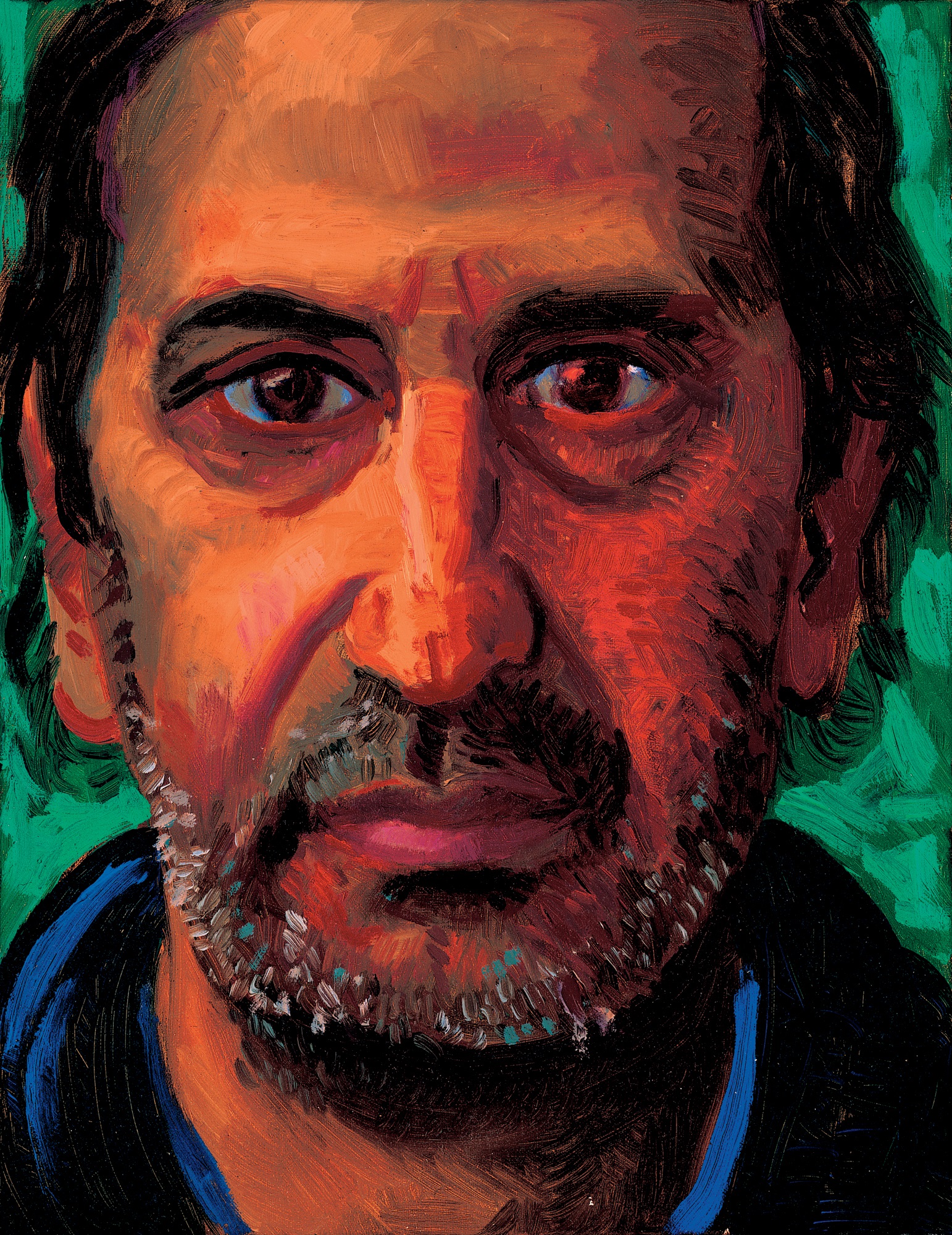

Much lighter in mood are the large portrait etchings that Hockney produced over a period of more than a year in 1998, working again with the printer Maurice Payne [210, 211]. Maurice knew full well that Hockney had lost his enthusiasm for travelling to print workshops with the express intention of producing a new body of graphic work. Having got used to the luxury of making prints on his own at home, with the ‘home-made prints’ of the mid-1980s [187], the fax drawings that followed soon after [190] and the colour laser prints of the 1990s such as 112 L.A. Visitors [191], Hockney appears to have developed a distaste for the artificiality of the print-workshop situation, which can be likened to the pressures of time and money experienced by pop musicians incarcerated in a recording studio to write and record an album. Payne came to the Hollywood Hills as a house guest and cleverly left prepared plates lying around in the hope that Hockney would be motivated to pick them up and draw on them with the spontaneity he displayed in the sketches he made directly on paper. The strategy worked, resulting in a series of portraits that exude a relaxed informality. Around fifty etchings were produced, not all of them editioned; these included also some luminous still lifes such as Red Wire Plant (printed predominantly in red) and fifteen individual portraits of his beloved dachshunds gathered together as a group under the title Dog Wall. Everything was done literally ‘in house’, as Maurice had even set up his printing press next door and was able to print the full editions there. This proved to be the artist’s most prolific and successful engagement with etching – and, sadly, perhaps his final involvement with the medium – since the Blue Guitar portfolio just over twenty years earlier [150].

209 Mum Sleeping, 1st Jan. 1996, 1996

210 Maurice, 1998

211 Soft Celia, 1998

One of the most arresting of these images is the portrait of Maurice himself [210], which focuses attention equally on the sitter’s face, his intertwined hands and his dark, loose-fitting jacket. A nervous energy courses through the whole image, including the freely cross-hatched lines that define the plane of the wall behind him. As attested by the title Soft Celia [211], the portrait of Celia Birtwell is its gentle, quiet, delicately traced, highly feminine counterpart; though Birtwell herself self-effacingly refers to the representation here of her facial features as ‘owl-like’, the picture conveys well the depth of the artist’s continuing fondness for a woman who has served as a confidante and trusted friend since the late 1960s. These and the other etchings from that sequence bear instructive comparison with the etchings made during these years by Hockney’s friend Lucian Freud, also printed just in black. Both series rely on close scrutiny of the sitter from life, reconfigured in characterful marks, in contrasts of tone achieved by cross-hatching and in precise linear delineation. Freud’s marks accumulate slowly, doggedly, with the same concentration as the brushmarks in his oil paintings; Hockney’s are much freer, more supple and organic, a network of spidery lines achieved by drawing on to the plates with specially made wire brushes.

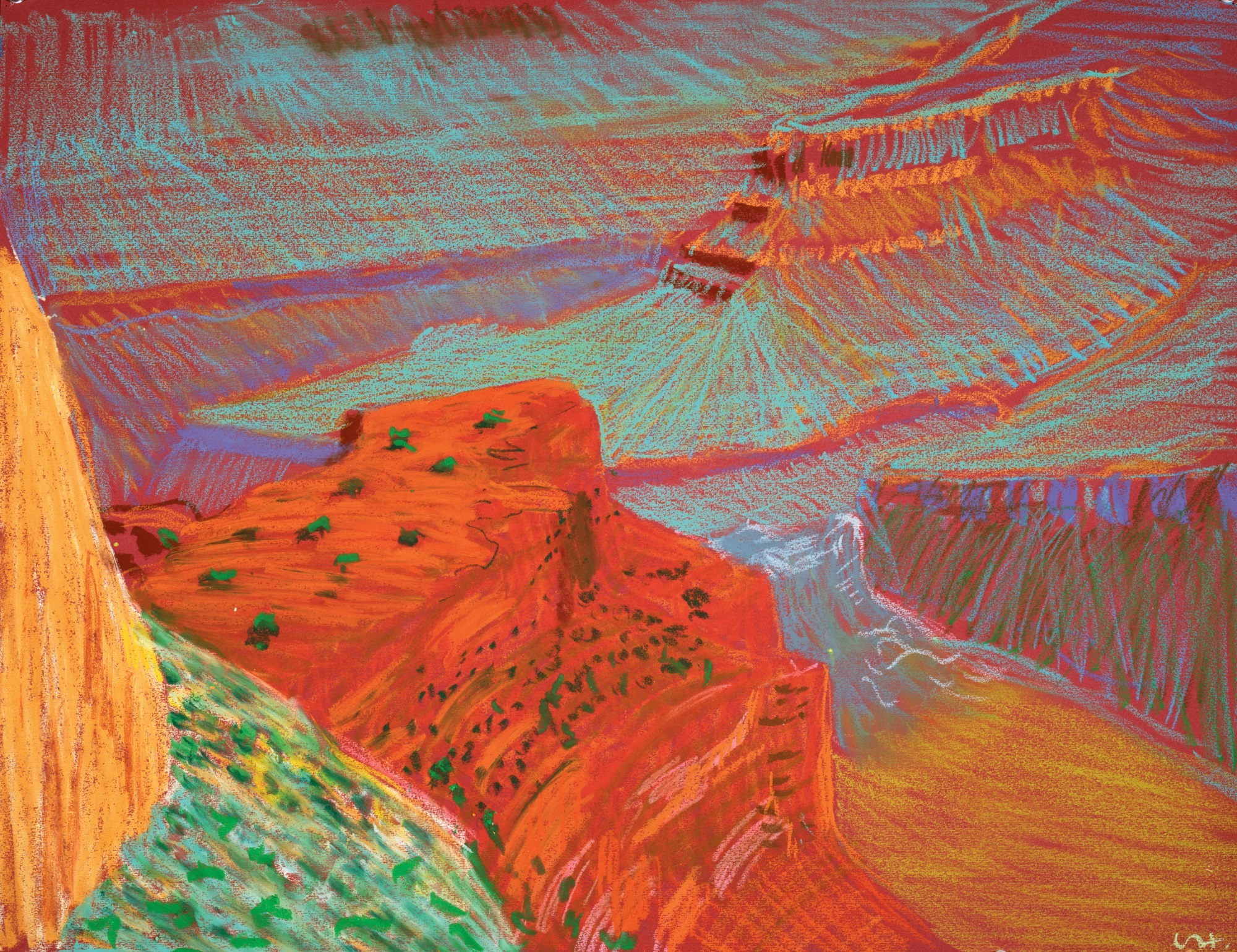

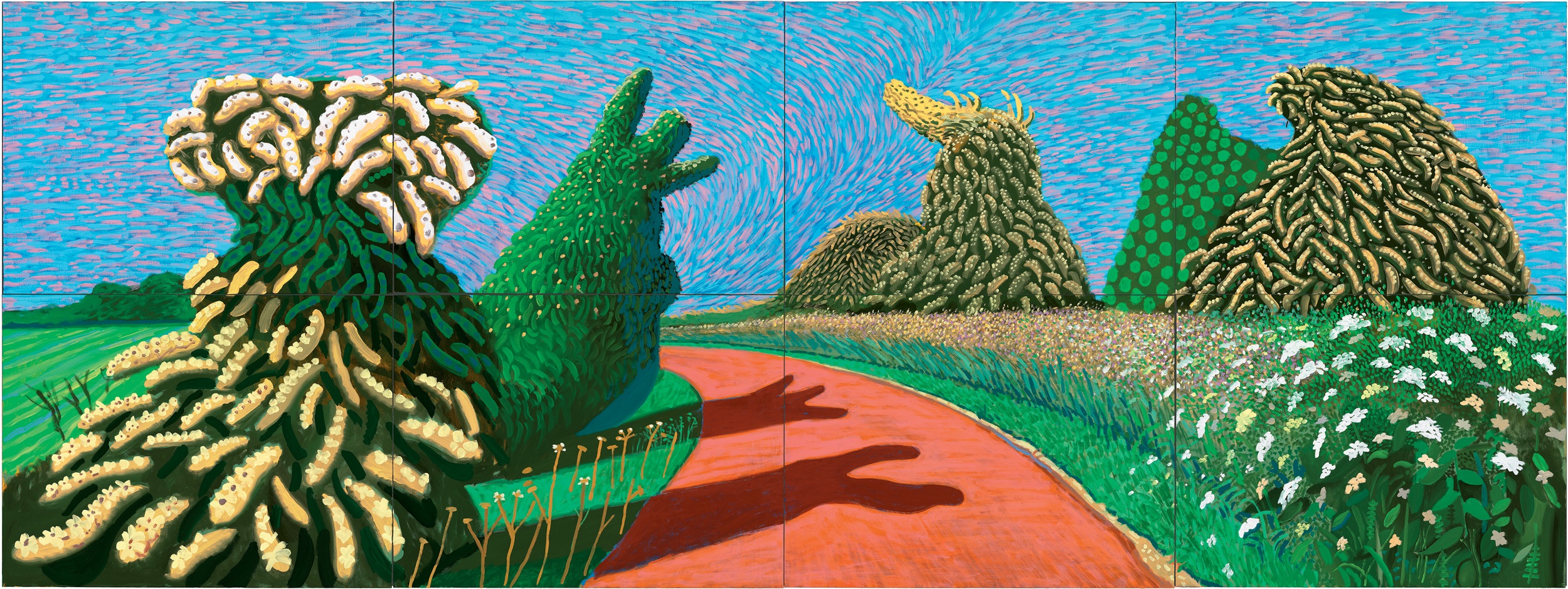

For many years, Silver had pleaded with Hockney to address in his paintings the landscape of his native Yorkshire. Having for so long avoided England as a subject, Hockney felt the urgency of indulging his friend’s persistent wish. He was well aware that Jonathan was now in the terminal stage of his illness; in ‘King of Salt’s Mill’, the touching tribute to his old friend published in The Telegraph on 22 November 1997, not long after Silver’s death at the age of forty-seven, Hockney described him as having been ‘my main contact with England outside my family’ during the previous fifteen years. Wanting to do everything in his power to keep Jonathan entertained and optimistic, Hockney made daily drives on the scenic back roads from Bridlington to Wetherby, fourteen miles west of York, gathering a memory bank of images of the largely unspoiled landscape of the East Yorkshire Wolds. Slowly he built up the momentum to make a small group of paintings of that landscape during the summer months back in the attic studio of the house in Bridlington, synthesizing his recollections of those particular routes much as he had done in 1980 when painting Mulholland Drive [172] and Nichols Canyon [161]. The first four – The Road to York through Sledmere [212], the sweeping bird’s-eye view of The Road across the Wolds, the bucolic idyll of North Yorkshire and (out of particular deference to Silver and his family) Salts Mill, Saltaire, Yorkshire – were followed in 1998 by two more painted on Hockney’s return to Los Angeles: Garrowby Hill [213] and the panoramic Double East Yorkshire, an expansive diptych nearly thirteen feet in width.

Like their Hollywood Hills forebears, these paintings all describe the sensation of moving through the landscape by car. They thus exist in a constant present, one in which the timelessness of an essentially unspoiled agrarian landscape is viewed through the windscreen of a quintessentially modern means of locomotion. Though playing on the nostalgic associations of traditional landscape painting and of the poster art of the interwar years celebrating the English landscape, these pictures amusingly provide a subliminal critique of the supposedly much more radical ‘Land Art’ pioneered by a slightly younger generation of artists during the late 1960s and 1970s. Richard Long, one of the foremost practitioners of this more overtly conceptualized mode of landscape art, documented his sculptural interventions in remote places in work combining photographs and texts, or brought back stones and other material evidence from those distant locations and presented them in post-Minimalist geometrical configurations in pristine gallery spaces; crucially, though, he conveyed a sensation of being in nature from the vantage point of a solitary walker, an essentially Romantic notion that in some way transports his work philosophically back to the early nineteenth century. By contrast, in The Road to York through Sledmere one feels the visceral impact of being catapulted at greater speed along a road, the twists and turns of which invite comparison with a roller-coaster ride with its attendant giddy thrills. The even more vertiginous perspectives afforded by Garrowby Hill, in which distant fields many miles away are spied from the summit of a steep hill, reinforce a sense of almost airborne freedom, a release from the constraints of gravity.

212 The Road to York through Sledmere, 1997

213 Garrowby Hill, 1998

These Yorkshire paintings, Hockney’s first to be set in his native county since his student works of the mid-1950s, seemed an unusual and exciting anomaly at the time, but proved to be extraordinarily prescient of the concerns he was to explore a decade later with a manic commitment. In January 1999 Hockney spent some weeks in Paris with his team, supervising the installation of his most substantial show in the French capital since the 1974 retrospective at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs. This took place between 27 January and 26 April 1999 in the expansive ground-floor galleries of the Centre Georges Pompidou when the rest of the building was closed for refurbishment. Curated by Didier Ottinger, ‘David Hockney: Espace/Paysage’ was the first exhibition to concentrate on Hockney’s landscapes, until then a subject of only passing and occasional interest, and more generally on his concern with conveying sensations of space. This exhibition had a momentous impact on his work during the following decade, particularly in directing him to landscape as a major focus of his attention.

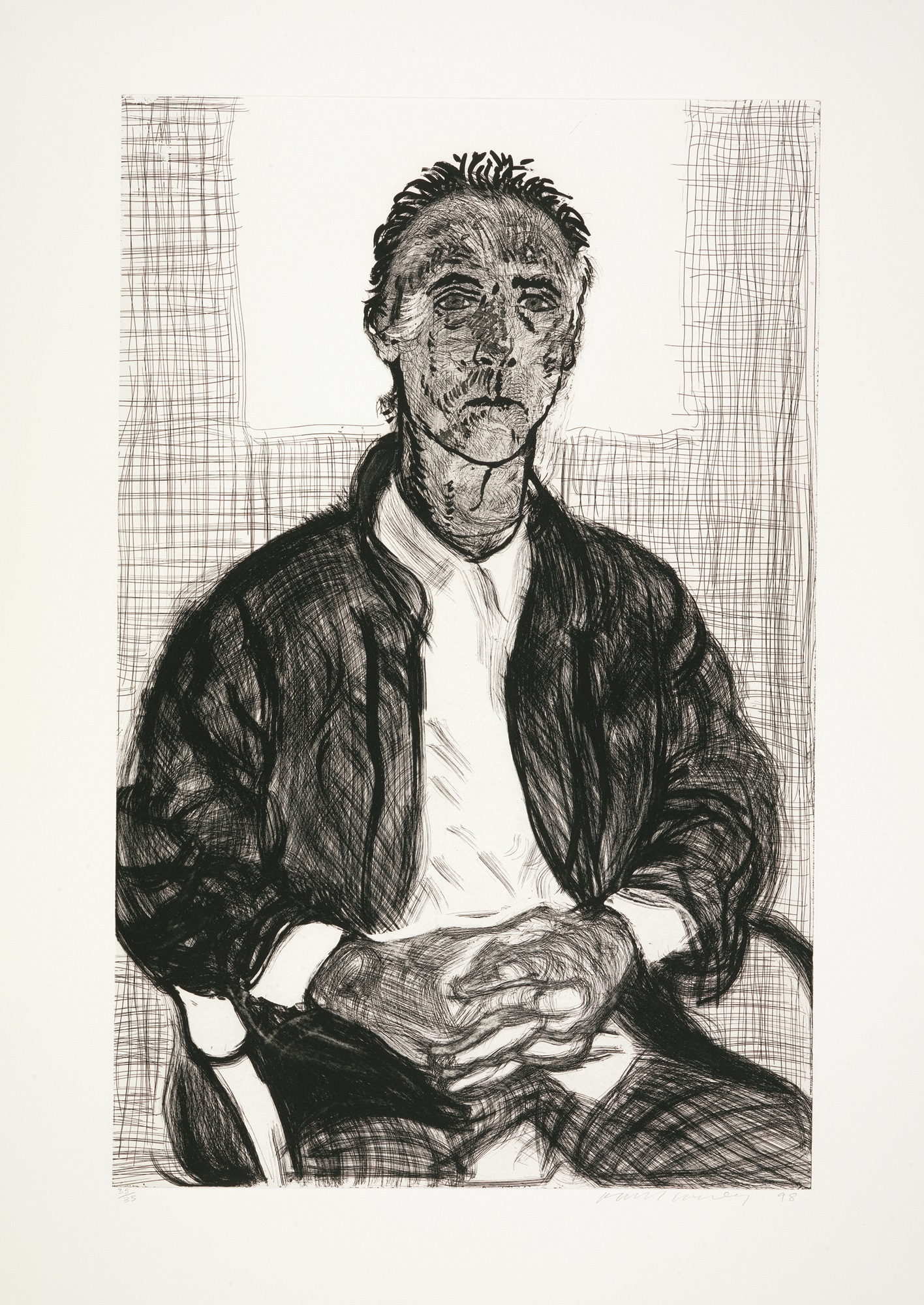

214 Study for A Closer Grand Canyon VI, from Pima Point, 1998

215 Gouache Study for A Closer Grand Canyon, 1998

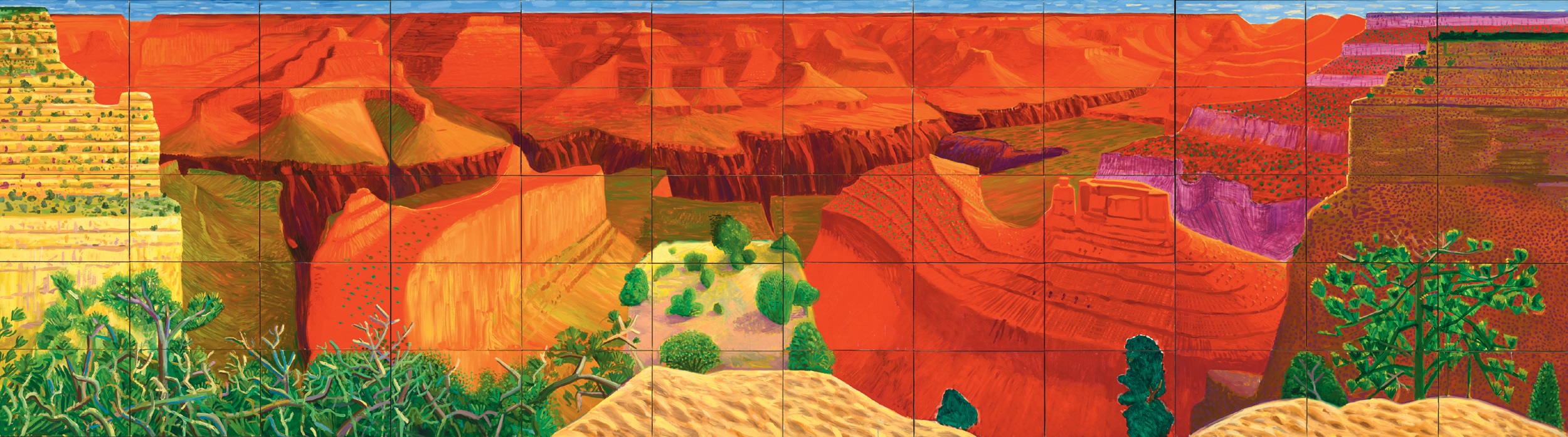

216 A Closer Grand Canyon, 1998

Hockney astutely understood that the Pompidou exhibition offered him the prospect not of a conventional retrospective, one that looked backwards at past achievements, but of a large space that itself could be animated as a complete installation. By involving himself closely in the hanging of the works and, more importantly, by deciding to make two huge new paintings as a thrilling climax to the exhibition and as a powerful demonstration of its themes, he conceived of the entire show as an immersive experience for the spectator. With characteristic energy and ambition, he set himself the punishing task of producing his two largest paintings yet, each one depicting the majestic spaces of ‘the biggest hole in the world’, the Grand Canyon. A Bigger Grand Canyon and its successor, A Closer Grand Canyon [216], were painted in 1998 in his Los Angeles studio from memory and on the basis of a number of studies in charcoal, oil pastel and gouache drawn on the spot [214, 215]. In 1982 he had attempted to capture the same natural wonder in two of his largest photocollaged ‘joiners’, one in a fan-like shape measuring over eight feet in width and the other, in a rectilinear grid, nearly ten feet wide. Sixteen years later, he had come to view the camera, even when used so resourcefully with multiple vanishing points, as an inadequate tool for conveying such a vast space: the colours in those photographic prints were necessarily muted in comparison with what could be achieved with oil paints, and the more distant details seemed remote and visually and psychologically ungraspable.

217 Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres Mrs John Mackie, née Dorothea Sophia Des Champs, 1816

Hockney decided therefore to dispense with photographic studies and to concentrate instead entirely on hand-wrought images that communicated a strong sense of being on that cliffside, surveying the vastness at his feet. The effects of light at different times of day, giving the rocky terrain an other-worldly glow; the heat arising from those desert surfaces; the sense of even the most distant points on the horizon looming into view as the eyes are focused: all of this comes into play. The two final monumental paintings, each constructed from a grid of identically sized canvases – a lesson digested from the Polaroid photocollages of 1982 – are on a suitably vast scale that could be described, in Hollywood terms, as CinemaScope. In its original manifestation, as exhibited in Paris, A Closer Grand Canyon had an additional three registers for a heavily clouded sky, but by the time Hockney showed it again at the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition later that year, he had removed those thirty-six canvases and cropped the image so that one’s entire field of vision is encompassed by the rocky terrain of the Grand Canyon itself. Now presented in five rows of twelve canvases, the vista becomes a powerful equivalent for the awe-inspiring sweep of that miraculous slice of nature.

218 Stephen Stuart-Smith. London. 30th May 1999, 1999

While his Paris exhibition was pulling in the crowds, Hockney also made the first of several visits to an impressive exhibition that was taking place simultaneously in London: ‘Portraits by Ingres: Image of an Epoch’, on view at the National Gallery between 27 January and 25 April 1999. He was particularly excited by the exquisitely detailed portraits drawn in Rome between 1806 and 1820 on an almost miniaturist scale [217], and he became obsessed with working out how such sureness and accuracy had been achieved when depicting sitters who were virtual strangers to the artist. Perplexed that the lengthy texts in the enormous catalogue spoke almost entirely about the sitters and offered no discussion about the processes and techniques, he discovered that an optical instrument used as a drawing aid, the camera lucida, had been patented in 1807. This device, which can be simply described as a prism on a stick, works by casting a virtual image on to the paper that can then be traced. Hockney quickly purchased both antique and newly manufactured examples of the camera lucida and in March 1999 began experimenting with it himself. He immediately became engrossed in the thrill of applying such close scrutiny to working from life, for the first time in his career actively seeking out strangers as well as old friends (whose faces he knew well) as potential models, and by the following year had completed 280 portraits. These include some of his most accomplished drawings of single sitters [218], as well as a work in twelve parts, representing uniformed attendants employed by the National Gallery in London, as his response to contribute to a group exhibition of works inspired by art in the gallery’s collection: Hockney bent the rules, taking as his inspiration the pencil drawings he had so admired in the recent Ingres show [219].

The plotting of the essential coordinates provided by the virtual image took up only a few minutes out of a session that might last several hours. The rest of the time was spent repeatedly building up a wholly convincing pictorial equivalent for a real person in space out of many hundreds of accumulated glances and strokes. The intense observational discipline that Hockney imposed on himself through this period was to prove of inestimable value when he returned to painting, setting aside not just the camera lucida but all lens-based equipment and photographic images. For several years, however, he made almost no paintings at all, so fired up was he by his discoveries and by his hunches about the use of optical instruments by artists over a period of five centuries preceding the invention of chemical photography. In an article titled ‘The Coming Post-Photographic Age’, published in the Royal Academy’s RA Magazine in summer 1999, Hockney concluded that ‘The period of chemical photography is over – the camera is returning to the hand (where it started) with the aid of the computer. All images will be affected by this. The photograph has lost its veracity. We are in a post-photographic age.’

219 Ron Lillywhite. London. 17th December 1999, 1999–2000

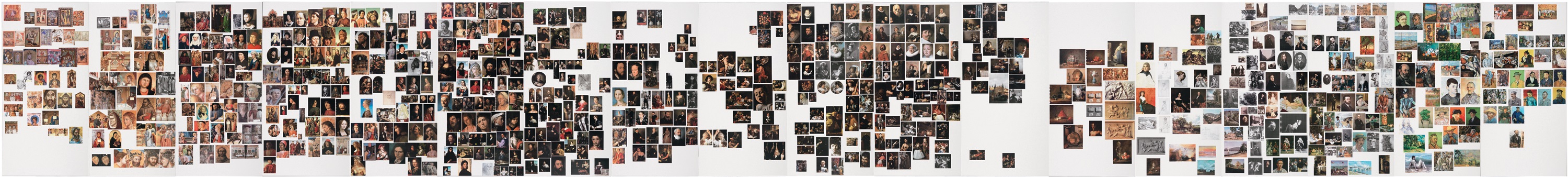

220 The Great Wall, 2000

Corresponding with sympathetic art historians and scientists, and sending his London assistant David Graves repeatedly to the British Library to dig out more historical information, for the next two years Hockney devoted himself to art history. Lucian Freud, who was among the circle of artist friends with whom he was sharing his discoveries, cannily described him as an art detective. Gradually he and his assistants accumulated a wealth of visual evidence in the form of colour reproductions that they pinned up in the studio on what they termed the ‘Great Wall’ [220]. He was given particular support and encouragement in the early stages by the Leonardo scholar Martin Kemp, and then found a great ally in the American experimental physicist Charles Falco, who not only enthusiastically embraced Hockney’s hypotheses but also collaborated with him on various practical demonstrations to gather visual proof.

The research eventually found form in a book published in 2001 by Thames & Hudson, Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the lost techniques of the Old Masters. Performing his own experiments to support his hunches, using the visual evidence of paintings by a very diverse range of artists, Hockney argued that the camera’s way of seeing had informed painting as long ago as the 1420s in Flanders. Though some art historians took umbrage, perhaps interpreting his views as an assault on their own credibility, he was less concerned with overturning scholarly assumptions than in opening everyone’s eyes to the limitations – even the fatal flaws – of photographic ways of seeing. However illuminating art historically Hockney’s observations are on the methods that may have been employed by artists as far back as Jan van Eyck, his book had an even more ambitious aim: to encourage a discussion on how lens-based solutions to representing perceptual reality have thoroughly conditioned our way of seeing the world, leading us to believe that only this way of seeing is ‘real’. It was time, he argued, to return to more subjectively human ways of looking and pictorially reshaping the world, making use of what the Chinese termed the conjunction of the eye, the heart and the hand.

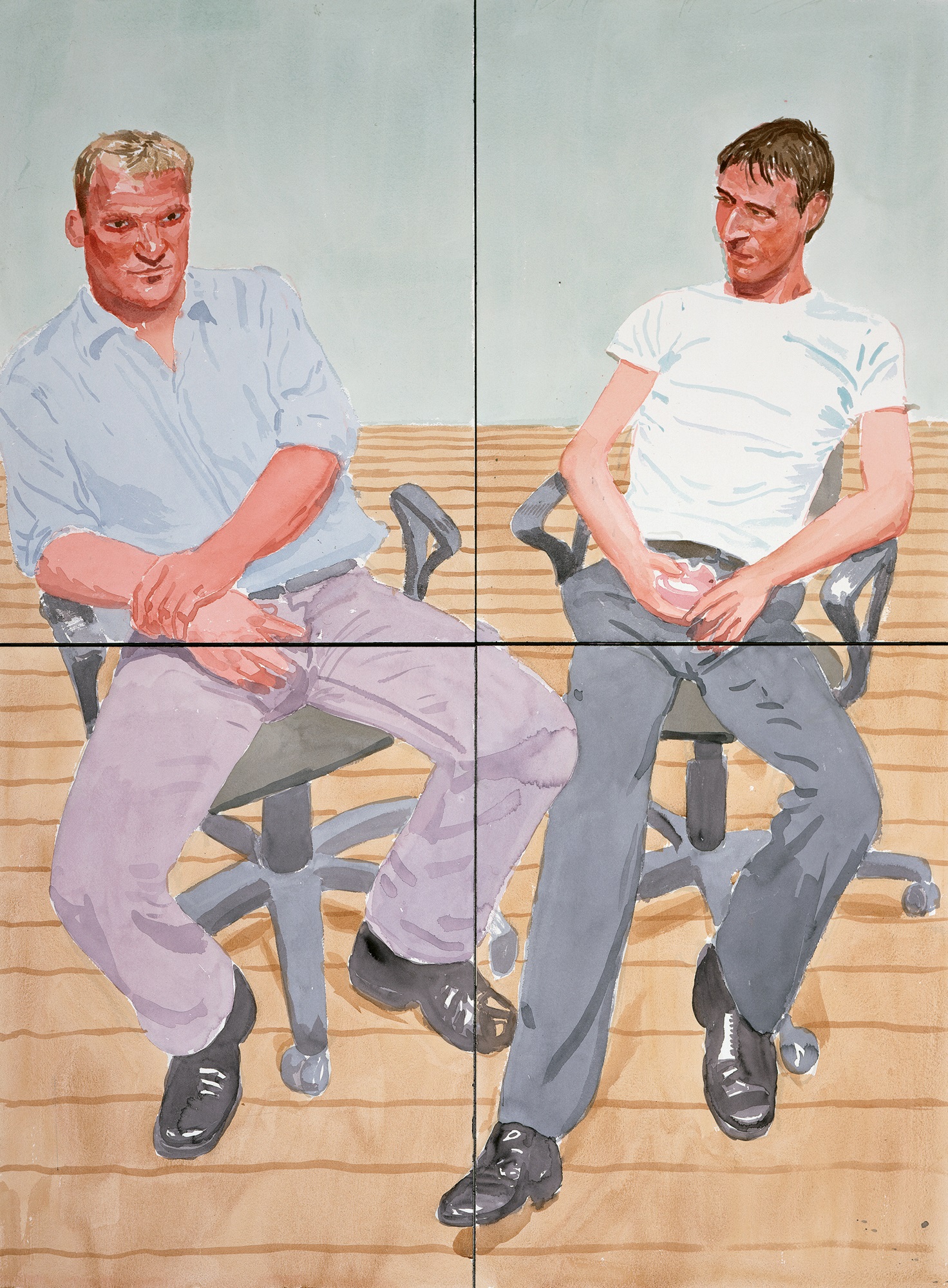

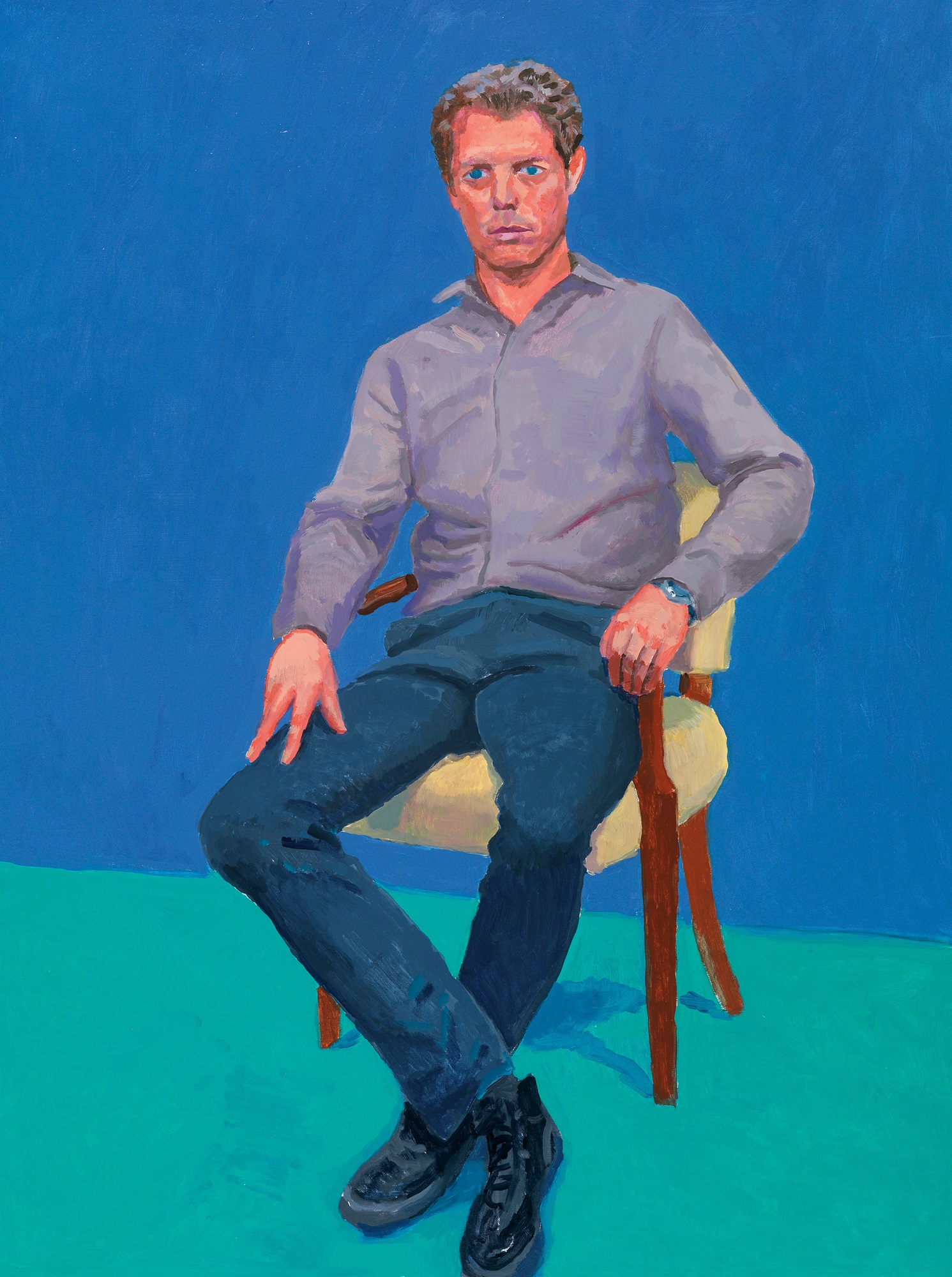

When Hockney returned in earnest to painting, it was, surprisingly, in watercolour, which he had previously used only intermittently and without great enthusiasm. Excited to be reminded about the watercolours he had made on a visit to Egypt in 1963, he decided to reinvestigate a medium often derided as the preserve of amateurs. In March 2002, during a stopover in New York City on a return visit to Britain, he painted some lively watercolour views of Central Park from his hotel window [272]. With his characteristic obsessiveness on discovering the possibilities of a new subject or process, he found himself immediately wedded to this water-based medium, relying on it almost exclusively for the next two years in landscapes, still lifes and a major series of nearly life-sized portraits. The sitters for more than thirty double portraits, each composed on a grid of four sheets measuring 24 by 18 inches each, began with a gay couple, the author of this book and his publisher partner [266].

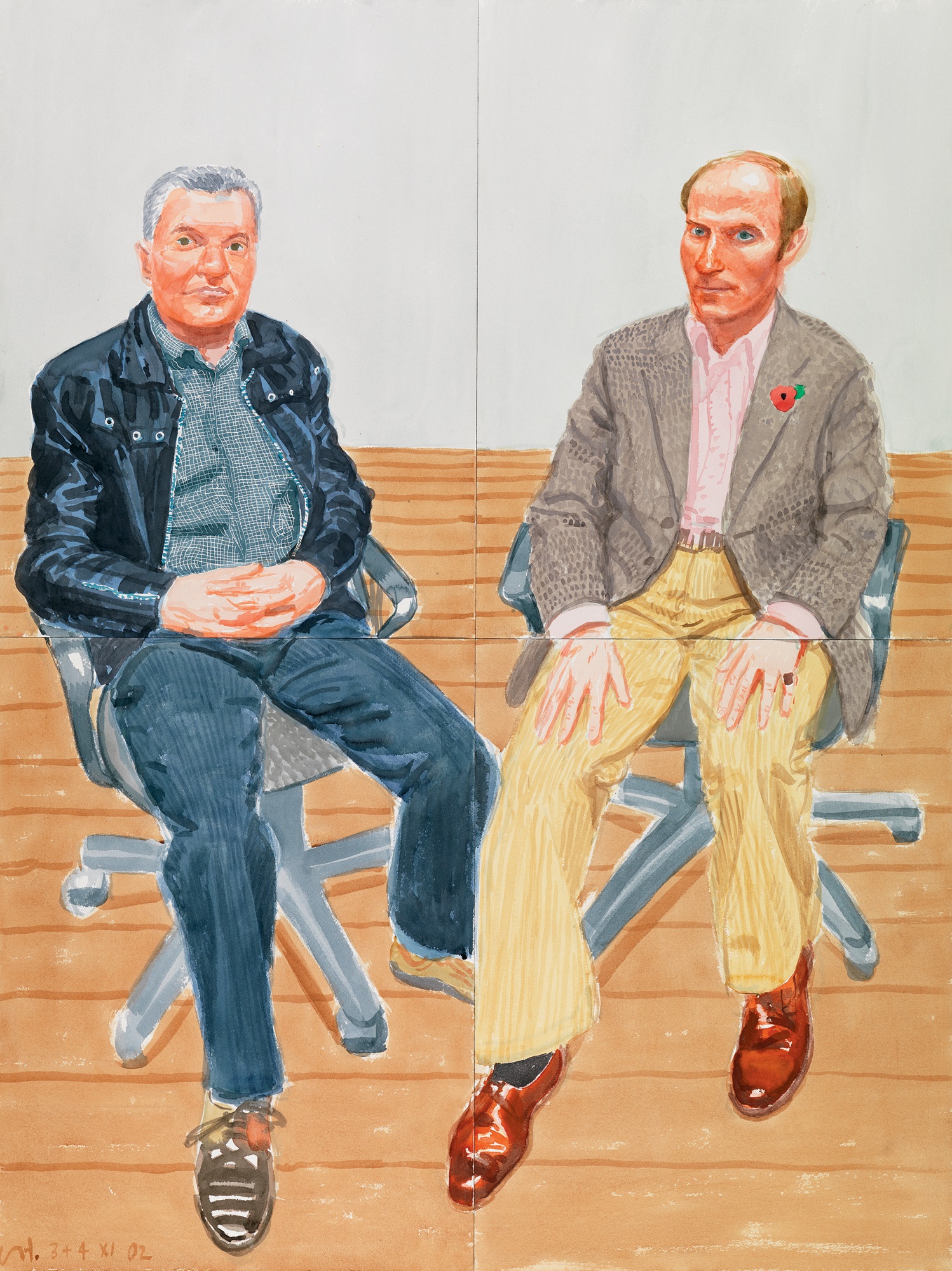

Given that Hockney’s fame as a painter of the human figure rested in part on the dozen or so carefully considered and slowly executed double portraits that he had painted from the late 1960s to the late 1970s [57, 89, 92, 109, 132, 144, 145, 151, 166], he took something of a risk in suddenly adding to this history so many other pairs of people now painted in a single intense session from life. These included other gay and straight couples – among them the painter Howard Hodgkin with his opera scholar partner, Antony Peattie; the painter Brian Young and his wife, Jacqui Staerk; and the curators Manuela Mena and Norman Rosenthal – and various pairs of siblings, including the twins Tom and Charles Guard (a particular challenge to his powers of observation). He addressed himself also to other types of relationships that intrigued him equally, for example between the painter Lucian Freud (for whom Hockney was sitting every day for four months for a portrait in oils) and his long-standing assistant, David Dawson [221]; the investment banker and art collector Jacob Rothschild and his writer and film-maker daughter, Hannah; and Hockney’s boyfriend, John Fitzherbert, and his half-brother, Robbie [222]. Working entirely from life and seeking to produce each of these in a single, long day with only one short break for lunch, Hockney accepted that the results would be variable, especially since watercolour is such an unforgiving medium, one that does not readily allow for corrections or overpainting. One has to work from light to dark, thinking from the start about the position of highlights by leaving those patches of paper exposed or coated in the most delicate wash; to really take command of the medium requires the ability to plot every move well in advance, as in a well-played game of chess. The best of these portraits, which take into account all these factors in the course of the complex act of observing and depicting, are tours de force.

221 Lucian Freud and David Dawson, 2002

222 John & Robbie (Brothers), 2002

A selection of these watercolours featured in the first major retrospective devoted to this subject, curated by Sarah Howgate and Barbara Stern Shapiro, ‘David Hockney Portraits’, which was presented at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston from 26 February to 14 May 2006 before travelling to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (11 June–4 September 2006) and the National Portrait Gallery in London (12 October 2006–21 January 2007). Characteristically, Hockney seized on this project as an opportunity to create new work. The exhibition included a staggering nineteen new portraits in oil, all painted in 2005. These featured, among others, Hockney’s sister, Margaret; his boyfriend, John; Gregory Evans; David and Ann Graves; his long-standing LA-based studio assistant, Richard Schmidt; his friend Charlie Scheips (who had worked briefly as an assistant in the 1980s); his new assistant, Jean-Pierre Gonçalves de Lima; his Los Angeles dealer, Peter Goulds; the art writer Lawrence Weschler; Celia Birtwell’s granddaughter Isabella; and his old friend Arthur Lambert.

Perhaps the most arresting of the single-figure paintings from this group is that of Dr Leon Banks [223], a Los Angeles collector who had sat for similarly intense and self-possessed portraits in watercolour on paper and in acrylic on acid-free board thirty-five years earlier. Taken together, the paintings produced in 2005 are not Hockney’s greatest achievements in portraiture. They are a little unimaginative in their repertoire of standing and seated postures, and they perhaps suffer from a sense of being somewhat hastily painted in order to meet the catalogue deadline. Nevertheless, they show courage in aiming for the freshness of Hockney’s earlier portraits from life, such as those made in 1988–89 [189] and 1996–97 [208, 209], but on a much larger scale: the standing figures are almost life-size. Best of all from this series is Self-Portrait with Charlie [207], a welcome return to the artist’s self-scrutiny, this time at his easel with a pair of brushes in his hand; a slightly comical note is introduced by the appearance of the bow-tied Charlie Scheips (reflected in the mirror behind the artist), who, by deciding to watch the master at work, must knowingly have hoped to insinuate himself into the picture and to be immortalized with his former employer. Hockney could have chosen not to paint him in, but by doing so he alludes wittily to the sometimes chaotic social conditions in which he works and to the network of friends who sustain him, in the process also making spatially specific the depth of the room in which the painting was made.

223 Dr. Leon Banks, 2005

Hockney’s prolonged period of working in watercolour was extremely important as a prelude to his return to oil paint not just in his portraits but also in the landscape paintings on canvas that he began making in 2005, enriched by all he had first learned in the observational, topographical studies of his sketchbook drawings and independent watercolours. Intriguingly, he did not immediately think of painting Yorkshire, which was to emerge as his constant subject for a full decade, when he took up the medium so closely associated with English topographical artists of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, including J. M. W. Turner, John Constable, John Varley and John Sell Cotman. He began naturally enough with pictures of his immediate surroundings in London; for example, of the flowering gardens in the courtyard of Pembroke Studios [224] and of the larger open spaces of neighbouring Holland Park, succinctly depicted, full of spatial play and imbued with great charm and freshness. In search of inspiration, his thoughts turned to travel, which had served him so well in the past. He journeyed with a few close friends first to Iceland and northern Norway in search of the light on the long summer days, and later to southern Spain, under a much harsher, brilliant, heat-infused sun.

224 Cherry Blossom, 2002

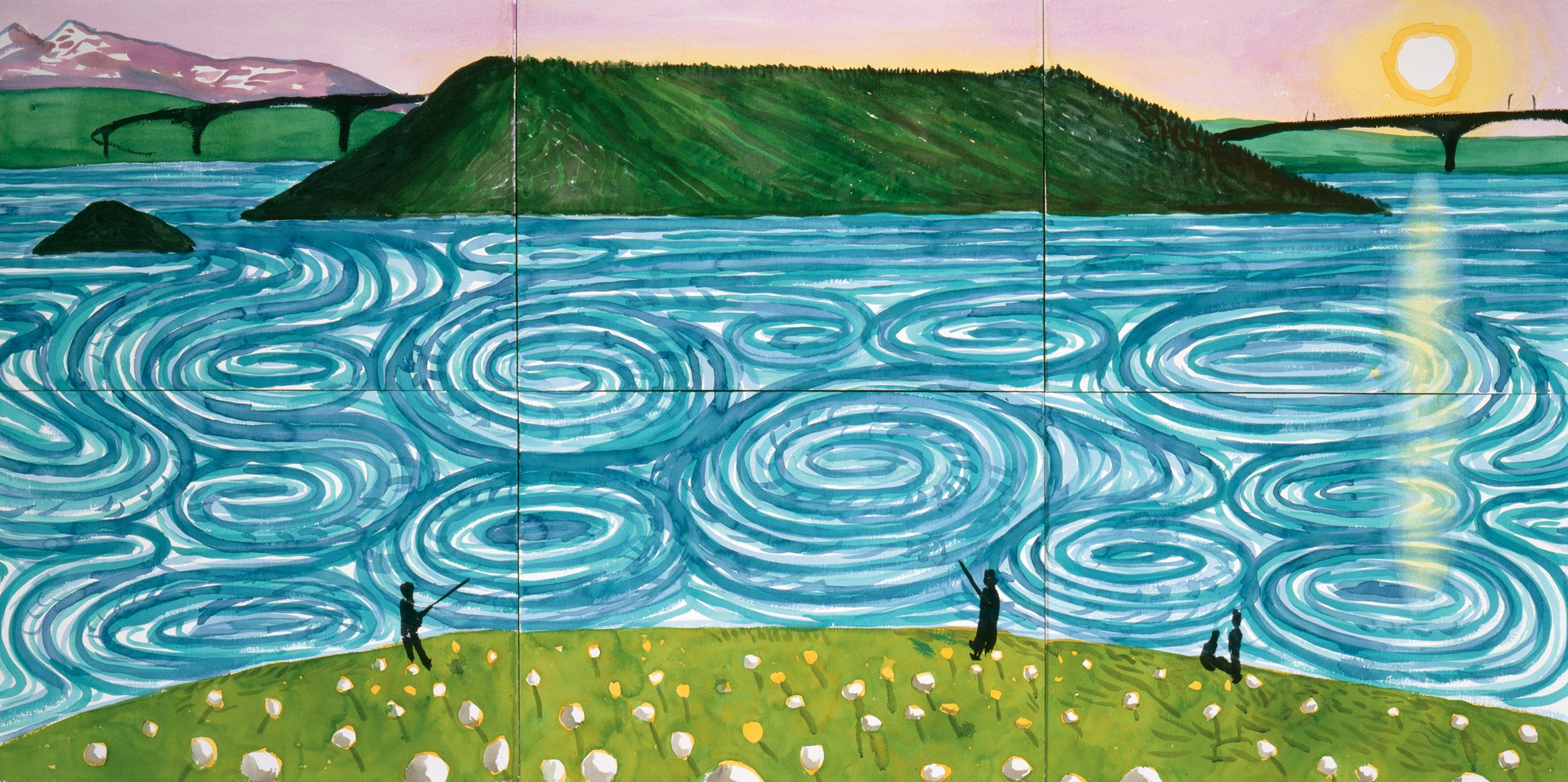

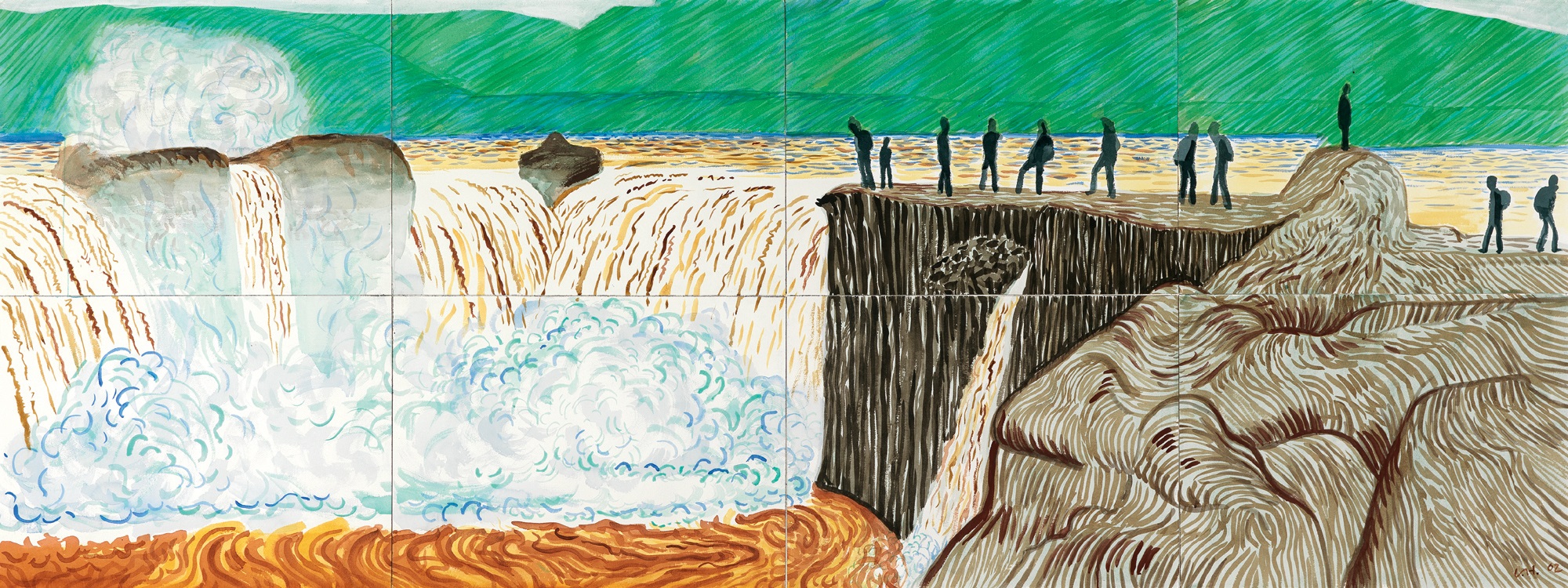

The Valley, Stalheim, 2002 [225], and The Maelstrom, Bodø, 2002 [226], each on six sheets of identical size, and Godafoss, Iceland, 2002 [227], on a grid of eight such sheets, typify the freedom, schematization, vivid colour schemes and luminosity of the very large watercolours that Hockney painted on his return to London. Basing these images on the ink and watercolour sketchbook drawings he had made from the motif, he worked to a significant extent from memory to compress the sensations of the vistas that he had documented in those much smaller drawings. Confronted by the vastness of the Norwegian landscape, he was clearly affected by recollections of the work of the country’s greatest painter, Edvard Munch. The six-sheet Tujfjord. Nordkapp II, 2002, for instance, with its acid colours and the burning orb of a setting sun reflected in the water, channels the Symbolist master to such a degree as to constitute an homage. The vertical format chosen for The Valley, Stalheim accentuates the majestic scale of the great gash bisecting the mountainous terrain of Hordaland county in Norway, taking the viewer into an experience of the sublimity of nature. Even more striking is the painting of the municipality of Bodø, in Nordland county, about two-thirds of the way up Norway’s immensely long western coastline. The small strait of Saltstraumen there is reputed to have the strongest tidal current in the world, and it is the energy of that maelstrom that caught Hockney’s eye as a potential subject for a painting celebrating the forces of nature. Whirling blue spirals describe the frantic motion of the water; the silhouettes of a few fishermen and onlookers along the lower bank of the strait reinforce, through their ant-like presence, the immensity of the location. The desire to induce a sensation of awe in the face of nature relates directly to the nineteenth-century paintings of the Hudson River School, which Hockney had studied closely on several visits to the exhibition ‘American Sublime’ at Tate Britain (21 February–19 May 2002) just as he was beginning to paint in watercolour.

225 The Valley, Stalheim, 2002

226 The Maelstrom, Bodø, 2002

227 Godafoss, Iceland, 2002

The inclusion of a row of diminutive figures at the edge of the waterfall in Goðafoss, Iceland [228], serves a similar purpose. Their position looks precarious, as if they could be swept off the precipice and swallowed up by the torrents at any moment. In such a situation, one cannot help but feel humble, even insignificant, all too aware of our tiny place in the greater scheme of things. It is a telling use of a device familiar from the Romantic paintings of Caspar David Friedrich, one of the great masters of northern European art whose work Hockney had admired since the 1960s. Where Friedrich’s technique was polished and tightly controlled, in the academic tradition, Hockney sought instead to preserve the boldness and spontaneity of his plein-air sketches, satisfying his long-held desire to capture in his paintings the spirit of his drawings. The entire scene is animated with a nervous energy that courses through every mark and through the patterns they make; even the way he has represented the cliffside in the lower-right quadrant of the picture, using marks reminiscent of the sepia ink reed-pen drawings he had made in 1978 under the influence of Van Gogh, appears charged with a fluid movement as powerful as that of the tonnes of water pouring into the Skjálfandafljót River. The sweeping gestures made by the artist’s hand, wrist or arm echo, in microcosm, the vast forces of nature, and in so doing serve as a potent subliminal reminder that we ourselves are simply minuscule elements within that infinite surge of life and energy.

Hockney’s subsequent trip to southern Spain resulted in a group of attractive watercolours, including one of the interior of the late eighth-century great mosque at Cordova (Córdoba) [228] that served as the basis for an oil painting on two conjoined canvases measuring more than eleven feet in width, Andalucía, Mosque, Cordova, 2004. The building is now known as the Mezquita-Catedral as it has served as the city’s Catholic cathedral since the mid-thirteenth century. One of the most extraordinary features of this ancient building, among the earliest surviving monuments from the Moorish period of Muslim control of Spain, is the hypostyle prayer hall, so named because of its intricate geometry of columns surmounted by semicircular arches. To walk through that space is to feel oneself beneath a complex, endless canopy of perfectly symmetrical trees. It is this forest-like appearance, which reverses the relationship between interior and exterior space, that clearly captured the imagination of the artist at a crucial moment of his reinvention as a landscape painter. During this period Hockney became fond of quoting Van Gogh’s assertion that, after becoming an artist, he had exchanged his youthful faith in his father’s religion for a veneration of the infinity of nature, and it is this prayerful wonder at an endlessly repeated man-made pattern emulating organic growth that here becomes his subject. Rendered in thinned oils on a bright white ground, Hockney’s painting captures the lightness of touch of watercolour as well as the medium’s translucency. The lively marks that occupy the upper register, reminiscent of those he had employed in his set designs and paintings of the early 1980s, lead the eye upwards in a soaring movement that creates an almost ecstatic atmosphere. His joy at re-engaging with painting is palpable and contagious.

228 Andalucía, Mosque, Cordova, 2004

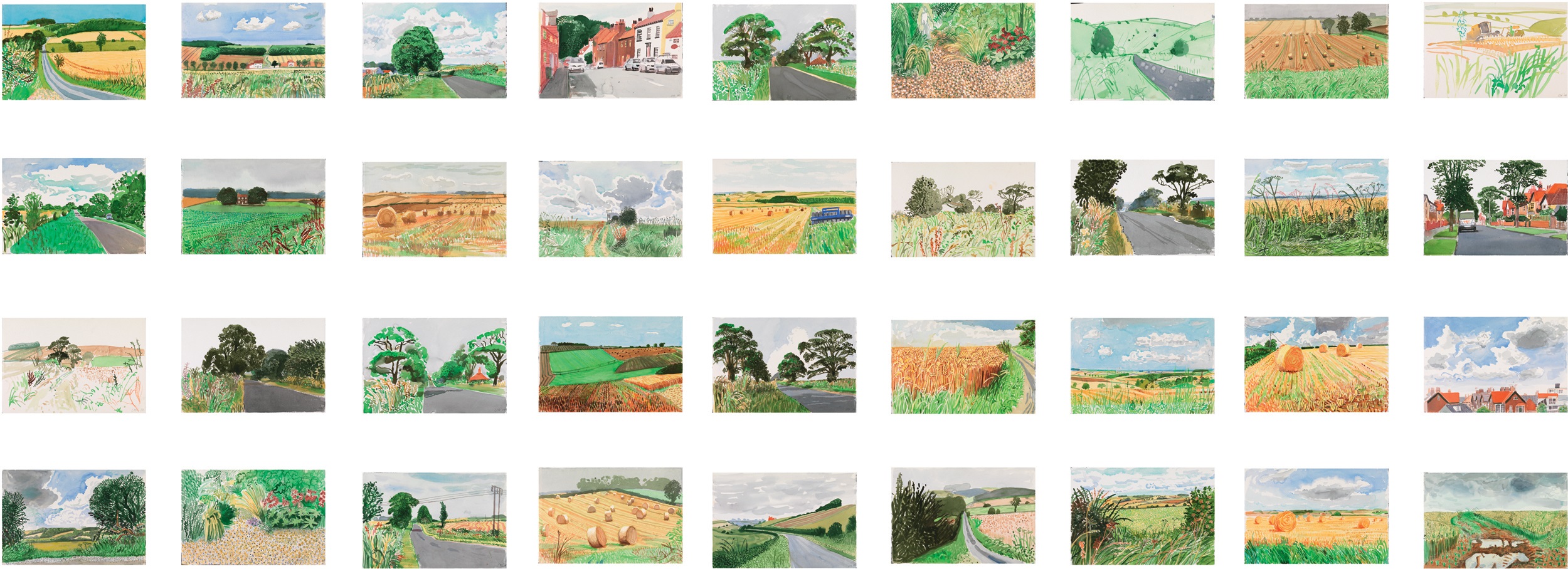

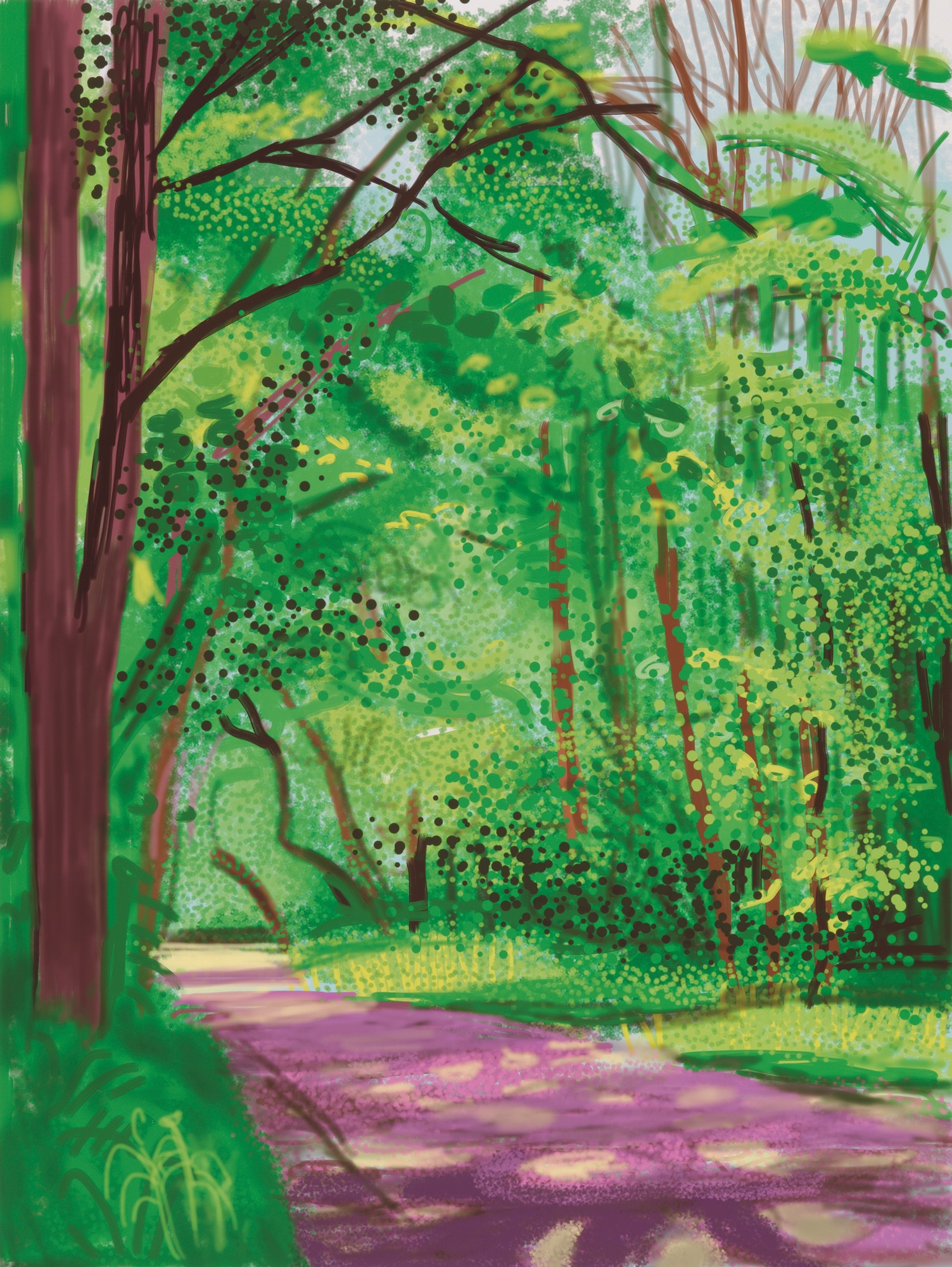

229 Midsummer: East Yorkshire, 2004

Having responded to the extravagant views he had witnessed in Norway, Iceland and Spain, Hockney was ready to address himself to the softer light and much quieter, less assertive landscape of East Yorkshire. In 2003, when John Fitzherbert overstayed his US visa by one day and was denied the right of re-entry, Hockney had decided to remain indefinitely in the UK so as not to be separated from his partner. America’s loss was Britain’s gain. When he finally started making watercolours of the Wolds, he immediately abandoned those travels to distant places, as if suddenly realizing that everything he needed, and his real subject, were on his doorstep. It was in these watercolours, culminating in 2004 in a thirty-six-part work entitled Midsummer: East Yorkshire [229], that he began developing the motifs and the repertoire of shorthand marks on which he continued to build in the oil paintings, charcoal drawings and iPad pictures of the same region through to spring 2013, when he finally returned to his Los Angeles home after his lengthiest sojourn in England since 1963.

Beginning in 2003, Hockney spent more and more time in Bridlington, in the very house where his mother had spent her final years in the company of his sister, Margaret, and began to commemorate the still-unspoiled scenery he had known in his youth. This nostalgia for his childhood, focused on the area of England in which he had spent his teenage summers as an agricultural labourer picking fruit and stooking corn, must certainly have been a way of reconnecting himself to his family roots in the aftermath of the deaths half a decade earlier of his mother and Jonathan Silver. The Yorkshire landscapes he had painted in oils in summer 1997 and 1998 celebrated the persistence of life against the backdrop of a heightened awareness of mortality. As with centuries-old depictions of landscape over the four seasons, there is an implicit acknowledgment of the cycles of life in nature, the land constantly regenerating itself, dying and being reborn.

Well aware that watercolour painting had fallen into disrepute as the medium of choice for the amateur artist and Sunday painter, Hockney defiantly set out to reassert its serious possibilities, seeking inspiration from his great British predecessors. The constantly changing skies and the transformative effects of light on the tone and hue of everything it touches – even the paved roads, never represented in the drab greys one imagines as their actual colour – are the aspects one might first notice in the thirty-six views that constitute the composite work of Midsummer: East Yorkshire. The variety of texture and plant life rendered in lively marks, as distinct and bold as those employed by Van Gogh, are equally important to the truthful way in which Hockney captures nature with a spontaneity and assurance that are masterful yet matter-of-fact. Without the benefit of any underdrawing in pencil, and relying exclusively on a medium that allows for no corrections or changes of heart, the artist needs to maintain his concentration as well as a steady rhythm that ensures a dynamic life coursing across each sheet. Every mark is laid bare; nothing is covered over. By giving himself so fully to the moment, he is able to capture, in a thrillingly unselfconscious way, an effect as subtle as the whistling of a breeze through overgrown grasses. Hung in grid formation so that the whole series can be apprehended as a single work – offering the spectator multiple points of entry, rather than a single static viewpoint – Midsummer: East Yorkshire reveals an artist in full command of his native powers. Hockney’s affection for the land is as transparent in these pictures as the washes with which he builds up and enriches his colours. Painted around the time of his sixty-seventh birthday, these watercolours convey a love of life and of the magical properties of painting itself.

After two years of work on Secret Knowledge and four years devoted almost exclusively to relearning how to use watercolour, Hockney was beside himself with excitement at the prospect of painting again in oils, knowing what a luxury this would be. Drying very slowly in comparison to watercolours, oil paint can be manipulated in many ways, with marks of different thickness and relative translucency or opacity; the surface can be wiped clean and repainted; light tones and bright hues can be painted over darker ones. All these options were acted upon as soon as Hockney took himself to the Wolds, set up an easel in front of the motif as an Impressionist painter would have done more than a century earlier, and began making one small landscape after another in a single, focused session. The confidence he had built up during his engagement with watercolour showed at once in the new oil paintings, made quickly and intensely with a calm assurance born of experience. In purely technical terms – but also in their observational accuracy and evocation of space – the landscape paintings that were to occupy him between 2005 and 2011 are the most commanding he has ever made.

Hockney was completely unconcerned that his choice of subject-matter and traditional procedure might appear brazenly old-fashioned in the early twenty-first century. He was convinced that the immediacy and directness of the method could result in paintings that were fresh and of their time rather than traditional or backward-looking. From the very first of these East Yorkshire oil paintings, which began on a modest two-by-three-foot scale completed in half-day sessions, as in the case of Path through Wheat Field, July, 2005 [230], and Tree Tunnel, August, 2005 [273], Hockney sought to empty his mind of a photographic way of looking and to create a straightforward pictorial equivalent for the real space stretching out before him. His immediate success and the speed at which he increased the scale and complexity of the pictures in diptychs and then in paintings that unfold fluidly over four, six, eight or even more conjoined canvases, were products of a lifetime’s experience: a cumulative history of painting and drawing, of looking at nature and of scrutinizing the art of his predecessors. Hockney’s landscapes build on a long tradition stretching back to the electrifying drawings made by Rembrandt with pen, brush and ink in the early seventeenth century, when landscape was just emerging as an independent subject. Having long pored over the reproductions in the catalogue raisonné he owned of Rembrandt’s drawings, judging the figure drawings to be among the greatest ever made, Hockney came also to appreciate the vitality and brilliant observation of the less widely known landscape drawings.

230 Path through Wheat Field, July, 2005

A major exhibition of John Constable’s landscapes held at Tate Britain in 2006, when Hockney was already deep at work painting East Yorkshire, confirmed the importance of the nineteenth-century artist to him and not just because Constable was the painter still most closely identified with the English countryside. Constable’s direct study of nature, which so decisively influenced the development of plein-air painting in France from the Barbizon School into Impressionism, established the precedent followed by many others, not least by Hockney himself. A highlight of the Tate’s Constable exhibition, and of particular interest to him, were the ‘full-size sketches’ for The Hay Wain and other major landscapes of the late 1810s and 1820s (the ‘six-footers’), which, for all their looseness, have an energy and conviction that to many modern eyes exceed those of the more polished final versions. But as Hockney wrote in February 2007 in a short preface for the catalogue for his exhibition ‘David Hockney: The East Yorkshire Landscape’, Constable’s naturalistic vision was heading in the direction of photography, while Hockney himself was turning his back on ‘the optical projection of nature’, which he had come to understand as an ultimately compromised and un-human way of looking at the world: ‘It is the position I now find myself in, realizing that two hundred years ago Constable would have thought the optical projection of nature was something to aim for. I now know it is not – so stand in the landscape you love, try and depict your feelings of space, and forget photographic vision, which is distancing us too much from the physical world.’

The Impressionists bequeathed to modern art a belief in the present moment, a celebration of transitory sensations of light and space in nature captured in permanent form in painted marks of great vivacity and brilliant colour. They and their successors, including such Post-Impressionists as Vincent van Gogh, as well as the Fauves during the first decade of the twentieth century, all served Hockney as points of reference. Especially in his mind was Claude Monet’s work, notably the Nymphéas arranged in two oval rooms at the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris, which Hockney visited soon after the renovation of the museum and the reinstallation of the paintings were completed in May 2006. The sense in which these late Impressionist masterpieces envelop and submerge the spectator in the spectacle of nature is an unforgettable experience to anyone sensitive to both painting and nature. Hockney, particularly when working on a large scale, seeks to bring the viewer right into the space and for much the same reason: to convey the strength of his feeling and aesthetic response to a particular place, seen at a specific time under unique conditions. Though Hockney, like Monet, came to work in series because of his habit of revisiting certain motifs, his concern has been more with space than with light, with seasons than with times of day. The ambition, however, is a very similar one: to subsume memory and time, including the duration of making the painting, into a moment that exists in a perpetual present. All good art, as Hockney is the first to say, is contemporary. More specifically, in these East Yorkshire landscapes, the time is always now.

By the end of 2005 Hockney had made forty-seven oil paintings, all of them directly from the motif, having graduated in August 2005 from the two-by-three-foot format to canvases measuring three by four feet. Though he started with open vistas and only a month later ventured into the enclosed spaces of a tunnel of trees, Hockney trusted his intuitions and to begin with made his decisions on a fairly spontaneous, day-to-day basis. He produced the first painting with no grand scheme, no sense that he would still be obsessed with the subject more than half a decade later or that he was embarking on the most prolific period of painting he had known in his always industrious life. Nothing was planned: ‘It just happened,’ as Hockney himself recalls. ‘That’s partly the excitement. You don’t know what it will really look like, you don’t know where it will lead. That’s the excitement for me, especially at my age.’ This willingness to go with the flow was the case even with the hiring of Jean-Pierre Gonçalves de Lima, a professional musician who had been doing odd jobs for the artist in London, but who after visits to Bridlington got so caught up in the enterprise that he became Hockney’s full-time assistant: he drove him when necessary, helped him to set up the easels and mix his paints. He also ended up taking many thousands of digital photographs of the artist at work and of each painting in progress, in itself an unprecedented documentary record of a fertile period in a major artist’s work.

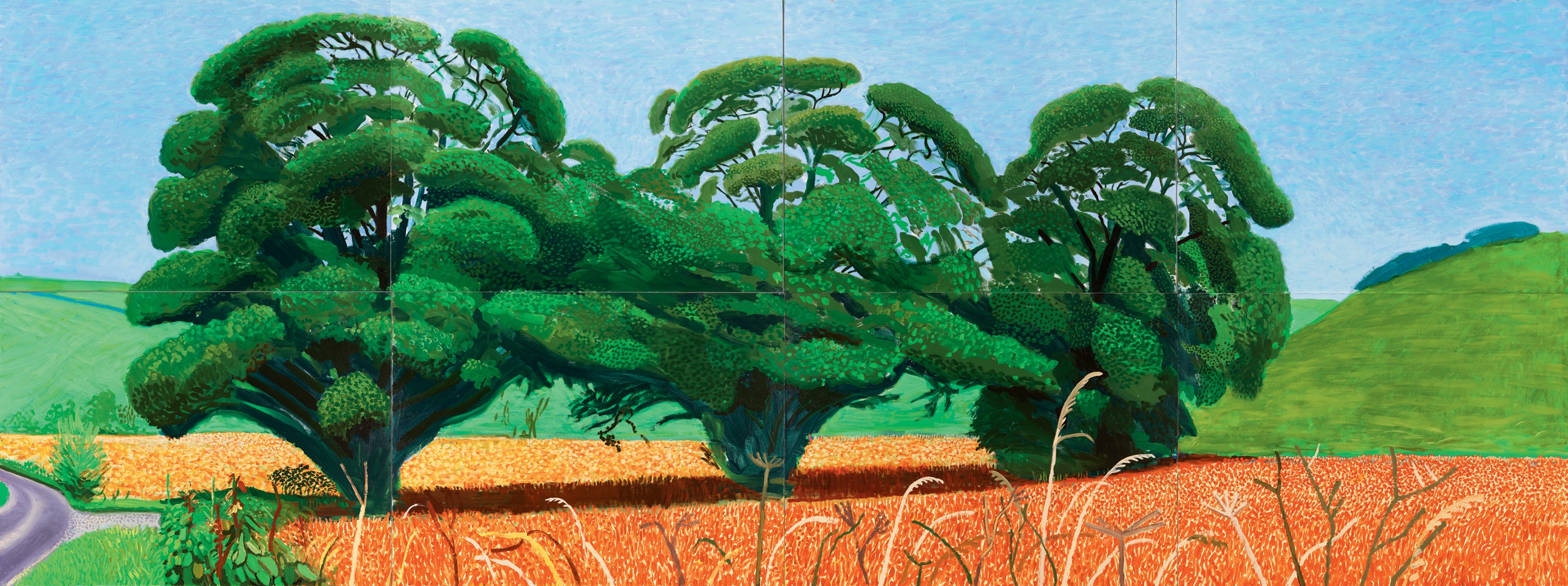

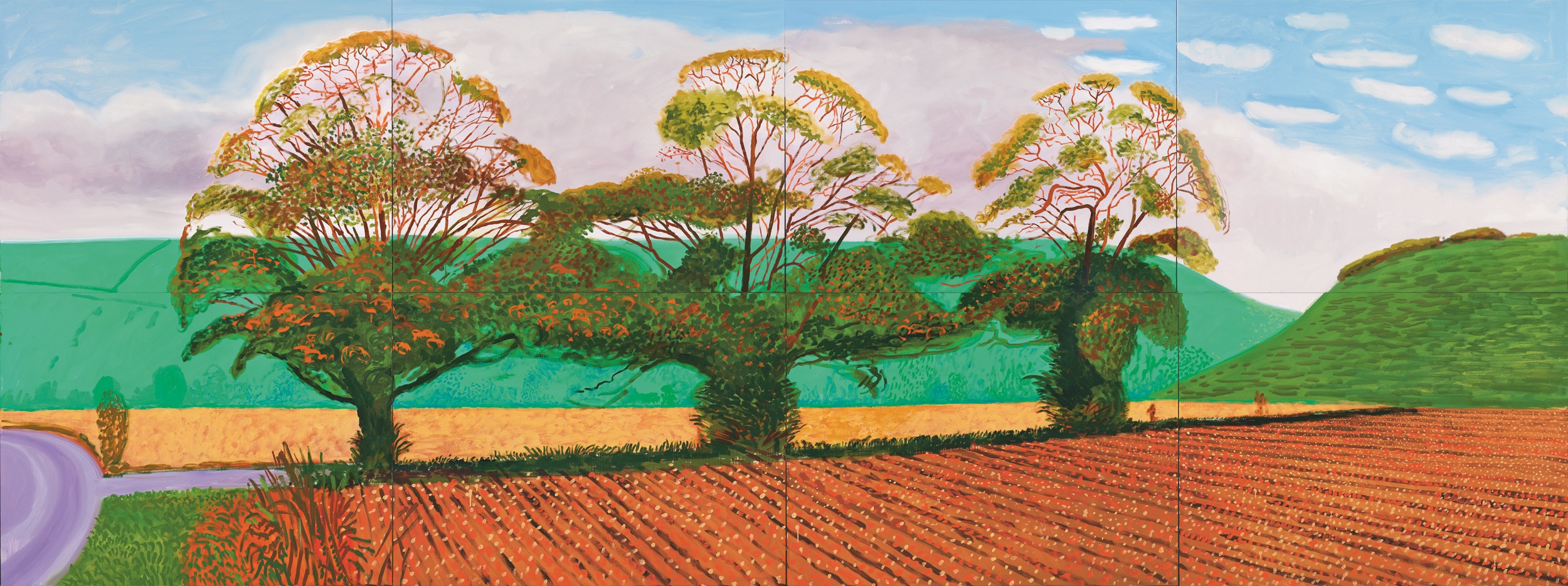

Ever more ambitious and spurred on by the consistent results, in 2006 Hockney produced a further fifty-one works, many of them on multiple canvases and therefore on a much bigger scale. Certain motifs that were first examined on small single canvases, such as the tree-lined mud track that he christened ‘The Tunnel’, were taken up again, sometimes repeatedly, in the much larger new configuration [240, 273]. These included nine six-canvas depictions of Woldgate Woods – viewed from inside the canopy of trees at different times of year, at the junction of three paths – as well as four in the same six-part format of an open vista, The Road to Thwing. The first Woldgate Woods painting took three weeks, from 30 March to 21 April 2006, but with a growing confidence born of daily practice over long hours, Hockney’s speed of execution accelerated at a remarkable rate without the paintings ever looking rushed. Woldgate Woods II was made over just two days, 16 and 17 May 2006, as was the next spring version, again conveying the thrill of sudden growth in verdant greens, less than a week later. He ended up producing a total of six paintings of this single motif, each in the same grid format, in various seasons and consequently with radically different colour schemes and vegetation [231, 232].

231 Woldgate Woods, 26, 27 & 30 July 2006, 2006

The increase in scale was not directed by a desire for monumentality. On the contrary, it induces a greater intimacy, bringing us as it does right inside the space it describes. With this came an even greater freedom in the making of the actual marks. Employing ever larger brushes, as the overall size of his surfaces grew, Hockney adopted bolder and more expansive movements, using not just his right hand, wrist and forearm but even the thrust of his body: the elbow, the shoulder and then the swing of his torso, all intensifying the sense of identification with the landscape, the sensation of physically moving within it and the vibrant physicality of the marks by which it is called into being. A particular fascination developed for trees as powerful living organisms, even as metaphors for human beings, as in the four seasonal variants of Three Trees near Thixendale [233–36], painted over the course of two years, where, by making manifest the cycles of nature, Hockney takes into account, too, a sense of our own mortality and the succession of one generation by another. How could a sensitive person approaching old age – he turned seventy on 9 July 2007, right in the middle of this series – not think about such things?

232 Woldgate Woods, 7 & 8 November 2006, 2006

Gradually Hockney began to increase his options by breaking the rules that he had first set himself. As so often in the past, he preferred to contradict his own strongly held views rather than be constrained by any programmatic limitations. Crucially, in the later paintings, especially the larger multi-canvas ones that are more difficult to manoeuvre in the open air, he no longer worked exclusively from direct observation. Rather than holding dogmatically to that initial system, he began to reintroduce memory when reworking canvases or putting finishing touches on them in the studio, and to invent certain details. The eight-part paintings of Three Trees near Thixendale were made entirely in the studio, because it would have been too unwieldy to set up eight large canvases in situ. By the time he painted these, Hockney had accumulated so much experience of working from the motif, and had got to know his chosen subject so well from many hours of looking, drawing and painting, that he could work again indoors without the paintings losing their veracity as eyewitness accounts. Having at first gone directly from the chosen motif to the canvas, without any preparatory studies, he began during this period to make quick but precise sketchbook notations of particular places from life, as well as to conjure them as memory images reduced to their essences as quick scribbles, on any readily available bits of paper. In 2008 he supplemented these with other, increasingly varied works on paper, including a series of glorious charcoal drawings of Woldgate Woods and hawthorn bushes in blossom, in which the by now familiar saturated colours are masterfully condensed into a subtle range of blacks and greys [239].

233 Three Trees near Thixendale, Spring 2008, 2008

234 Three Trees near Thixendale, Summer 2007, 2007

235 Three Trees near Thixendale, Autumn 2008, 2008

236 Three Trees near Thixendale, Winter 2007, 2007

For certain subjects that came to his attention suddenly, and that had to be seized when there was no time to waste, Hockney did not hesitate to work again in the studio primarily from memory, with only some quickly drawn notes to assist him. Such was the case with a series he initiated in 2008 of highly animated paintings of hedgerows filled with copious amounts of hawthorn blossom, in that thrilling moment of spring when they suddenly come into flower. He took delight in shocking his more genteel listeners by likening the effect of these outbursts of white to the ejaculation of semen – a metaphor that, behind its ribald humour, made a very serious point about the fertility of nature. A particular playfulness entered through this motif, in the almost cartoonish form of depiction and in the exaggerated shadows cast on the road by apparently overexcited plants. Whether conversing with friends or someone he had just met, Hockney was fond of asking, ‘Who was the greatest American artist of the twentieth century?’ The most common answers were Edward Hopper, Jackson Pollock and Andy Warhol. ‘No!’ he would reply triumphantly: ‘Walt Disney!’ Behind the mischievous humour, he was deadly serious in his admiration for the originality of vision of Disney’s great animated films, an influence especially hinted at in the paintings made on a cinematic scale, such as May Blossom on the Roman Road, 2009 [237].

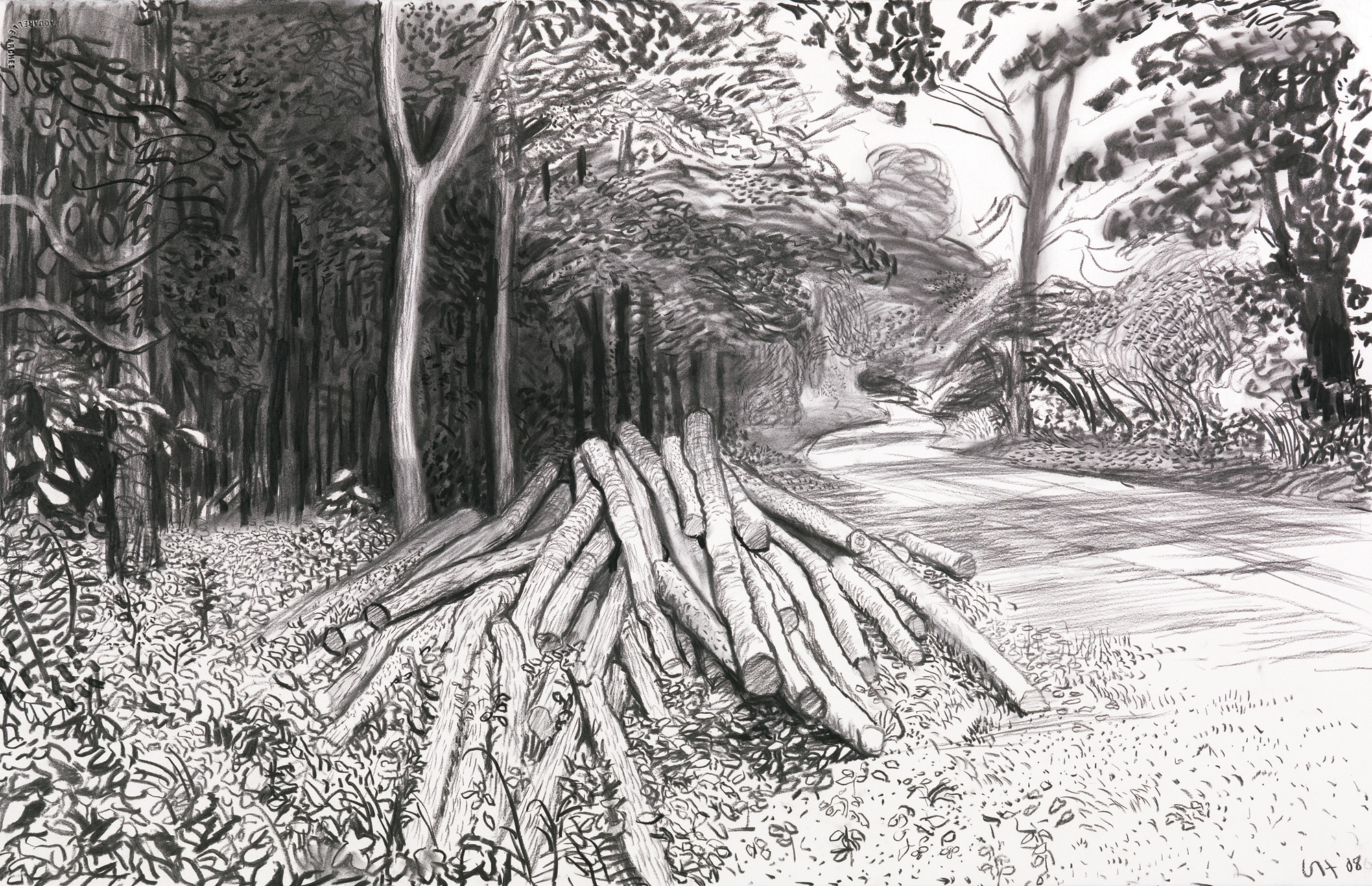

Another subject that imposed itself spontaneously on Hockney’s paintings was that of the felled trees, cut into fresh logs, that he encountered on one of his habitual drives through Woldgate Woods. It must be said that these paintings of logs and of the solitary truncated trunk that he referred to as a ‘totem’ have a different quality from those that preceded them, and not only because of their spiky linearity or the introduction of ‘horizontal trees’ played against the vertical ones: in this case, the fact that they were painted in the studio, depicting a subject seen for a comparatively brief period, necessarily lends them the more schematized air of an image held in memory. The series culminated in the enormous Winter Timber, 2009 [238]. Hockney’s initial distress at encountering the unexpected drama of a beloved grove felled to the ground and arranged in tidy rows was surely occasioned not just by his fury that one of his favourite motifs had suddenly disappeared before he had had the chance to paint it again. On a deeper level, it was about confronting his own mortality through the ‘murder’ of those once imposing trees. So it is that the paintings themselves convey not only a sense of mourning, the logs standing in for human corpses, but also – in the form of the totem – a defiance about survival even in decrepitude [239].

237 May Blossom on the Roman Road, 2009

238 Winter Timber, 2009

Hockney had begun to make use of the very technology from which he had initially distanced himself – the camera and the computer in tandem – to help him in planning and completing the more ambitious multi-canvas compositions. The first work for which he availed himself of this method was a six-part painting, A Closer Winter Tunnel, February–March, 2006 [240], a highlight of his 2006 solo exhibition at Annely Juda Fine Art in London. Given the difficulties of reassembling the constituent parts on site on each occasion, the opportunity to study the development of the work in this way was hugely helpful in bringing it to a successful conclusion. While still rejecting a photographic mode of vision, Hockney happily made use of the camera for the task to which he has long maintained it is best suited: reproducing works of art. One of the first instances of this reliance on photography and computer technology, and by far the most ambitious, was in the creation of a mural-sized picture, Bigger Trees near Warter [241], painted almost entirely from the motif over a period of three weeks from late March to mid-April 2007 on fifty identically sized canvases that were then hung as a block at the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition of that year. Hockney had already produced three studies – the first on a single three-by-four-foot canvas, the second on a pair of canvases of the same size and the third on six canvases of those dimensions – before gearing himself up to start work on what must be the largest landscape ever painted in the open air.

239 Cut Trees – Timber, 2008

240 A Closer Winter Tunnel, February–March, 2006

241 Bigger Trees near Warter, or/ou Peinture sur le Motif pour le Nouvel Age Post-Photographique, 2007

The idea for the final massive version of this subject had come to Hockney on his return visit to Los Angeles in mid-February 2007, a week or so after the opening of his ‘East Yorkshire Landscape’ exhibition at L.A. Louver, when he witnessed the impressive impact of four of his multipartite landscapes reproduced together on the screen of his computer. He immediately realized that it was possible for him to create a painting on an immense scale, still from direct observation, without the need for ladders or a complex mechanism of easels. Working on a small group of canvases at any one time, he had each canvas photographed as it was made, and then pieced the images together on the computer screen back at the studio, so that he could see how the composition was progressing and make any necessary adjustments. He saw the physically complete work only briefly, in a hired space where it had to be wedged in at an angle, before it was finally hung at the Royal Academy, but by then he had left relatively little to chance.

The excitement created by the display of Bigger Trees near Warter led immediately to an invitation from the Royal Academy Exhibitions Committee to give over all the main galleries, probably the grandest and most beautiful exhibition rooms in London, to a major exhibition of Hockney’s work, the first in the UK on this scale to be presented for nearly twenty-five years. An opening date was set four and a half years away, in late January 2012. The artist seized the opportunity with great enthusiasm, but he was adamant that this be an exhibition of his new Yorkshire landscapes, even if it included two galleries of earlier paintings on a similar theme, rather than a conventional retrospective. I was appointed guest curator, working with the Royal Academy’s Edith Devaney, whose remit included the annual Summer Exhibition and the Academy’s members. Both of us just about managed to keep up with the septuagenarian artist’s frantic pace of production and the constant changes to the hanging plan necessitated almost to the last minute by the sudden appearance of new works.

Building on the lessons gained from a show called ‘David Hockney: Nur Natur/Only Nature’, curated by Hockney with his assistant Gregory Evans and presented at the Kunsthalle Würth in Schwäbisch Hall, Germany, from 27 April to 27 September 2009, the Royal Academy exhibition was conceived through a chronological and thematic unfolding of the subject as a kind of theatrical spectacle. There was no desire to deny the impact on this recent work of Hockney’s previous experience of working for the stage. Indeed, it was his express desire not only to create the whole exhibition as a unified installation punctuated by startling set pieces, but also to enclose the viewers within these surrogates of nature so that they could engage actively with the depictions of landscape as if they were themselves accompanying the artist on a long walk or drive through this treasured, unspoiled and little-visited part of the country. The exhibition reached one of its climaxes in the largest of the galleries with The Arrival of Spring in Woldgate, East Yorkshire in 2011 (twenty-eleven), consisting of one huge painting occupying the same wall as Bigger Trees near Warter and fifty-one large inkjet prints of images drawn on an iPad, each individually dated, that showed the gradual awakening of the landscape between 4 January and 2 June of that year [242]. As so often before, the exhibition ‘David Hockney: A Bigger Picture’ attracted some criticism along with many admiring reviews, but was above all a huge popular success, drawing in about 650,000 visitors during its London run before travelling to the Guggenheim Bilbao and the Museum Ludwig in Cologne.

242 Installation shot of The Arrival of Spring in Woldgate, East Yorkshire in 2011 (twenty-eleven), as installed in the exhibition ‘David Hockney: A Bigger Picture’, Royal Academy of Arts, 21 January–9 April 2012

Towards the end of this immense labour, in 2010, Hockney set himself a new challenge, still connected to landscape but this time based not directly on nature but on the reinterpretation of an untypical painting by the seventeenth-century master Claude Lorrain, The Sermon on the Mount of c. 1656 [243], which he had studied with great interest at the Frick Collection on a recent visit to New York. Despite Claude’s great fame, continuing visibility and interest to art historians – not least as a great influence on Turner and as a progenitor of classical landscape painting – this particular picture had been little remarked upon, partly because it had sustained smoke damage in a fire two centuries earlier and consequently suffered from an overall darkening of the surface that made its individual details difficult to see. Hockney spoke to the museum’s curators and conservators and borrowed from them a high-resolution digital file of the painting, which with the help of his recently hired technical assistant, Jonathan Wilkinson, he subjected to a ‘digital cleaning’. Through a progressive lightening of the image, more and more information not easily visible to the eye came into focus. Hockney then felt ready to make a first, very loose transcription of it on a canvas measuring three by four feet, the size he had used for many of his own Yorkshire landscapes half a decade earlier and as a building block for the subsequent larger works. From this first quick investigation of the composition, which fascinated him for its unusual depiction of distant space partly occluded by the enormous mass of the mount shown just off-centre, he graduated boldly to a much more detailed version on a canvas of precisely the same dimensions as the original by Claude [244].

243 Claude Lorrain The Sermon on the Mount, c. 1656

Hockney had no interest in making a faithful replica, as a skilled copyist trained in Old Master techniques would attempt, but instead sought to remake the picture in his own language as a means of deconstructing and then reassembling the elements. By the end of the year, he had produced an astonishing eleven versions of various sizes and in contrasting styles, much as his hero Picasso had done in the 1950s in his variations on Diego Velázquez’s Las Meninas, Eugène Delacroix’s Femmes d’Alger and Edouard Manet’s Déjeuner sur l’herbe. Some of the freest interpretations by Hockney, such as version VII [245], playfully adopt the pictorial language of late Picasso, which Hockney had long greatly admired and which he referred to as a ‘Cubism of the brush’. The series, which was given a room to itself towards the end of the Royal Academy exhibition, culminated in the largest of all these works, A Bigger Message [246], on a grid of thirty canvases, each measuring three by four feet. Hockney defended this rare excursion into Christian imagery with a self-deprecating joke: ‘Don’t you think that I preach?’ The series was unusual also in its direct reference to a specific work by an Old Master and in its inclusion of numerous figures, in great contrast to the noticeably unpopulated landscapes he had been painting in Yorkshire, which presented spaces to be animated by the spectators themselves. Thinking laterally, Hockney saw the Claude pictures as inextricably linked to his own landscapes from the motif, not just as investigations of pictorial space but also in their tone. Version IV, in which the word ‘LOVE’ is emblazoned over the small figure of Christ at the top of the mount, makes plain the overriding theme of Hockney’s own prolonged engagement with nature and the landscape of East Yorkshire.

244 The Sermon on the Mount II (After Claude), 2010

245 The Sermon on the Mount VII (After Claude), 2010

The last day of the final showing of ‘David Hockney: A Bigger Picture’ was 3 February 2013. Most artists know very well the feeling of let-down, akin to post-partum depression, after giving birth to even a small gallery show, so Hockney must have been bracing himself for a major crash to earth following the phenomenal success of such a major exhibition that had toured for just over a year. His solution, as usual, was to launch himself a mere two days later into another very demanding project, this time to record the arrival of spring in Woldgate not in iPad pictures but in a sequence of intricate charcoal drawings representing five specific motifs on five separate occasions, each over a period of several months.

246 A Bigger Message, 2010

247 Woldgate, 21–22 May from The Arrival of Spring in 2013 (twenty thirteen), 2013

The tragic death on 17 March 2013 of one of Hockney’s assistants, Dominic Elliott, aged just twenty-three, nearly brought the series to a premature close, particularly since this new project was so closely associated with this self same young man, who was accompanying the artist while he drew. Hockney decided to persist, and to bring the series to its conclusion as a way of busying himself when he was on the verge of a breakdown or depression himself, and in some way, too, as a kind of memorial to an affable friend who had first met him as a child. The series was shown in its entirety between 26 October 2013 and 20 January 2014 in ‘David Hockney: A Bigger Exhibition’ at the De Young Museum in San Francisco. The final drawing was completed on 27 May, after which Hockney soon returned to his house in the Hollywood Hills for his first extended stay in California since the late 1990s. One of the last of these drawings, Woldgate, The Arrival of Spring in 2013 (twenty thirteen), 21–22 May 2013 [247], is sublime in its lace-like network of foliage, but the entire group of twenty-five drawings, seen as a single work, must count as one of the artist’s finest achievements. It is of course tempting to read these drawings sentimentally, and to find in them a quiet and contemplative melancholy atmosphere, given the conditions under which most of them were made. Whether or not this would be a misguided application of pathetic fallacy, these delicately wrought and closely observed studies of a by now very familiar but wholly unpopulated country road manifest a sense of human solitariness within nature that is profoundly affecting.

After employing Jonathan Wilkinson to work with him on new technologies in April 2008, Hockney had begun with his usual sense of anticipation and curiosity to explore the possibilities for drawing with computer software, a Wacom graphics tablet and a tablet pen. Learning with great speed not only how to use these instruments, but also how to make them perform in unexpectedly flexible ways, he found the new technology instantly attractive for the possibilities it offered when working back at his home with fresh memories of visual sensations still imprinted on his retina. Some of these computer-assisted landscapes, in the form of inkjet prints, were physically reworked by hand with charcoal or with a coloured medium. Whether or not the resulting drawing has an ‘impure’ status was of no concern: all that counted was the opening-up of fresh possibilities. Hockney even abandoned his decision of just over half a decade earlier to reject photography, this time using high-definition digital cameras for hybrids of photographic imagery with marks drawn ‘freehand’ on the computer. Some of these inkjet-printed computer drawings, such as Winter Road near Kilham, 2008 [248], and its summer pendant, morph freely and somewhat unnervingly from pure invention to hyperreal photographic detail, and combine different vantage points and conceptions of space, so that one has the sensation of floating bird-like through the landscape. Other prints – such as the opulently decorative Autumn Leaves [249], named after the evergreen song popularized in French by Edith Piaf and in English by Nat King Cole among others – were drawn entirely on the computer without photographic intervention.

248 Winter Road near Kilham, 2008

In the late 1980s and early 1990s Hockney had briefly experimented with Quantel Paintbox and Oasis software, drawing images on his computer and printing them out for himself and as gifts to selected friends, but never editioning them [195, 197]. The process at that time was frustratingly slow, with marks made on the flat surface taking so long to materialize on the screen that the picture could not be composed with the speed and fluency that he would have liked. He abandoned these experiments, returning to them only in 2008, when new software and much more powerful computers suddenly made it possible for him to realize such works to more precise standards. When the first of these inkjet-printed computer drawings on paper were shown between 1 May and 11 July 2009 at Annely Juda Fine Art in London, in an exhibition titled ‘David Hockney: Drawing in a Printing Machine’, the artist contributed a catalogue preface in which he remarked:

‘The computer is a powerful tool. Photoshop is a computer tool for picture making. It in effect allows you to draw directly in a printing machine, one of its many uses.… I used to think the computer was too slow for a draughtsman…, but things have improved, and it now enables one to draw very freely and very fast with colour.… The speed allowed here with colour is something new, swapping brushes in the hand with oil or watercolour takes time. These prints … were made for printing, and so will be printed. They are not photographic reproductions.’

249 Autumn Leaves, 2008

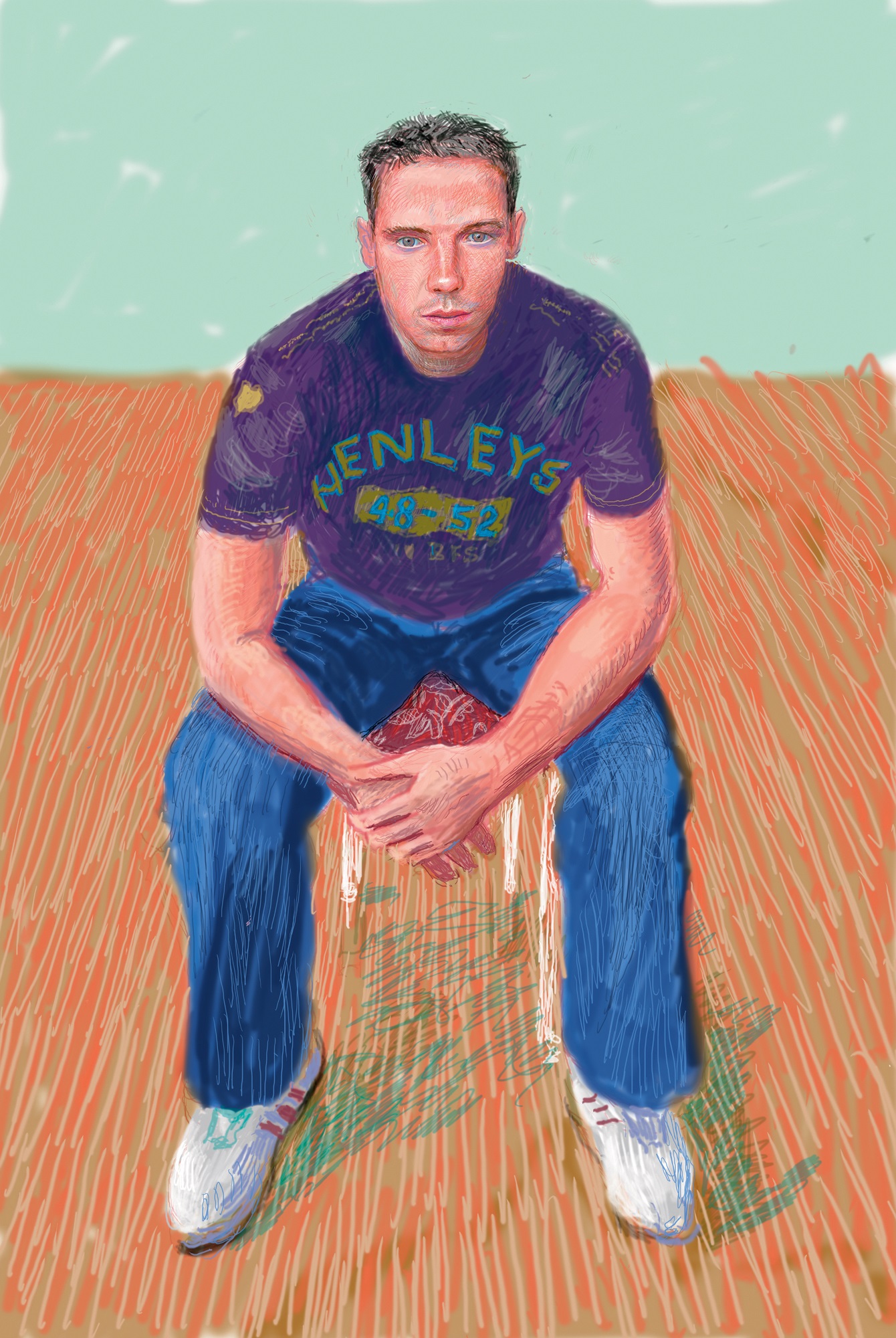

Particularly effective in this exhibition were the nearly twenty portraits of friends, family and associates made using the same process. Two of the young assistants at Hockney’s Bridlington studio, Jamie McHale and Dominic Elliott, were among the sitters, each demonstrating a quietude, self-possession and attentiveness that immediately engage the viewer’s attention [250, 251]. Aware that they are being subjected to such close scrutiny by the artist, they hold his gaze as we, in turn, hold theirs in viewing their portraits. As in the case of the camera lucida drawings of National Gallery attendants that Hockney had produced in 1999 [219], there is a sense of dignity being conferred on people who historically might not have been honoured through portraiture in this way. In three of the other prints, the artist’s brother Paul and sister, Margaret, prone to the family fidgetiness and perhaps mild cases of attention deficit disorder, are amusingly seen lost in thought as they tinker with their iPhones: a way of keeping them busy but relatively still, as if they were children. They share with their artist brother a fascination with new technology; it was, in fact, Margaret who first bought an iPhone and persuaded David to follow her lead.

250 Jamie McHale 2, 2008

251 Dominic Elliott, 2008

252 Rain on the Studio Window, from My Yorkshire (deluxe edition) 2009

Those first editioned prints of 2008, again made with Wilkinson’s technical assistance, were followed by a computer drawing on a more intimate scale, Rain on the Studio Window [252], conceived in 2009 and printed in late 2011 to accompany the de luxe edition of Hockney’s book My Yorkshire. This is not just an impressive demonstration of the artist’s mastery over the new process, but a brilliant evocation of the grey light and melancholic atmosphere of a rainy English afternoon. Forty-five years earlier, Hockney had escaped the dreary climate of his native land for the cheery sunniness of southern California, where he made celebratory pictures of light glancing off the glass windows of modernist houses and dancing through the inviting waters of swimming pools. Now, even stuck inside the attic studio of his suburban Bridlington house on a wet day, he demonstrates his resourcefulness in making a picture from the most unpromising of circumstances. Beauty resides not in the Velux window or its wood-grained surround, but in the intensity of the looking and the wit in transcribing these observations. The rivulets streaming down the glass like bolts of lightning empower the image with its own electric energy and appear to illuminate it from within.

253 Untitled, 474, 2009

254 Untitled, 522, 2009

As with all of Hockney’s graphic work, in the computer drawings he exploits the medium for its particular qualities rather than as a substitute for another process. Not long after the release by Apple of the first-generation iPhones in summer 2007, he bought one himself, and in the summer of 2009 he began using it as a drawing tool, having been alerted by his sister, Margaret, to an application called Brushes that enabled the gestures made on the screen with one’s thumb or finger to be translated into marks. Like a child with a new toy, Hockney excitedly set about discovering the potential of this novel medium, which quickly became for him a kind of electronic sketchbook that could be carried with him at all times [253, 254]. No longer needing to carry paper, pencils, pens or watercolours, he could make densely layered, richly coloured, highly decorative pictures using a variety of marks from the range of effects offered by that one cheaply available app. Even when lying in bed early in the morning, or taking time out from a day of painting, he could quickly draw whatever caught his eye. Light streaming through louvred windows, a water-filled vase of what Hockney termed ‘fresh flowers’, and sunsets over Bridlington beach were among the favourite motifs of the hundreds of vivid, joyful pictures that he took pleasure in delivering electronically to his friends and colleagues in a spirit of great generosity. As in the case of the fax pictures of the late 1980s, but now in the sumptuous, richly coloured medium of the back-lit screen, he found a way of making art for the sheer joy of it, circumventing any attribution of marketable value as these pictures could be endlessly shared and circulated. He was, nevertheless, canny enough to send them out not as high-resolution Brushes files, which could have been reworked by the recipient, but translated into PDFs as finished images.

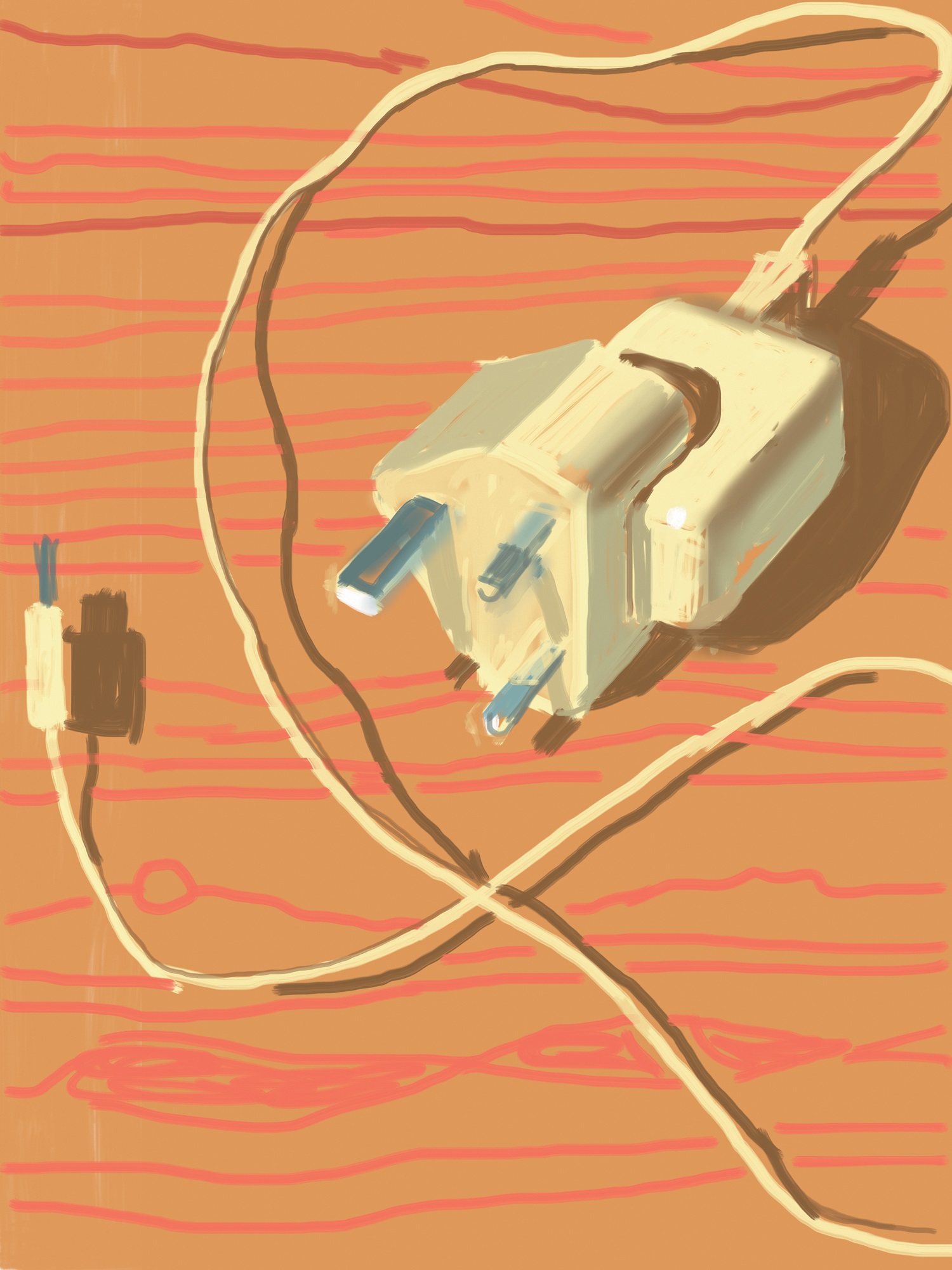

Having gained so much pleasure in drawing on the iPhone, Hockney lost no time in acquiring a first-generation iPad immediately on its release in the USA in April 2010, and began at once to draw on that in preference, using the same techniques he had mastered on the iPhone. The much larger screen allowed him to produce increasingly sophisticated pictures. More detail could be included by zooming in, and the use of a rubber-tipped stylus on the touch-sensitive screen enabled a greater degree of control, with more subtlety and accuracy of line, immeasurably enriching these new pictures [255, 256]. Hockney began drawing the same views along Woldgate that he had been painting, but now from the comfort of his car seat, where he could sit for hours in all weathers with the iPad perched on his lap. These works were made again simply as an end in themselves, and his first thought was to include some of them in the Royal Academy exhibition on a series of wall-mounted iPads, as indeed came to pass. The thrill was compounded for him, however, when he discovered that, with the aid of software tweaked by his own studio assistants, it would be possible to print these images digitally on large sheets of paper without visible pixellation or any loss of focus in the individual marks. Once he had printed some trial images, Hockney knew that he had found the solution for the largest room in the ‘Bigger Picture’ exhibition, The Arrival of Spring in Woldgate, East Yorkshire in 2011 (twenty-eleven), in which he arranged, in chronological order, fifty-one of these iPad drawings in two registers all around the space. At that stage he had no thought of publishing them, still to be convinced that they could be regarded as limited-edition prints in the same way as his earlier etchings, lithographs or even computer drawings. Later he came to the conclusion that their sheer beauty, and the fact that the digital printouts are not reproductions but original images in their own right, warranted their dissemination on paper. In 2014–15 he published forty-nine of them on paper in editions of twenty-five, in a 57-by-44-inch format, and a further twelve on four sheets of Dibond measuring 96 by 72 inches overall [257].

255 Plug in for the Next Generation (684)

256 Self-portrait, 25 March 2012, No. 1 (1231)

257 The Arrival of Spring in Woldgate, East Yorkshire in 2011 (twenty eleven), 28 April, 2011

The greatest surprise at the Royal Academy exhibition was reserved for one of the final spaces, in which Hockney premièred his first video installations, essays in space and time that again took the same Yorkshire landscape as their subject. He had begun to explore the medium in February 2010 in a spirit of curiosity, just as another way of documenting the landscape, without knowing at that point that this would lead to a result that he could even call art. That first video, shot with a single camera, looked a little shaky and home-made, but it was enough to persuade him that he was on to something and that it would be worth investing in much better equipment. Highly critical of what he considered to be the gimmicky 3D technology that was being employed with great fanfare in Hollywood films such as Avatar, released in 2009, he was convinced that he could devise another way of filming that was much truer to the way we see. His solution took into account not only his recent multi-canvas landscapes but also, even more pertinently, the post-Cubist Polaroid photocollages and 35 mm ‘joiners’ that he had made between 1982 and 1985. Mounting nine high-definition digital video cameras on the bonnet of a four-wheel drive, Hockney sat inside the vehicle while one of his assistants drove very slowly down country lanes and another adjusted the positions of the cameras to perfect the ‘drawing’ that the artist was witnessing on the monitors. Only in September 2010, when he and his team were able to view the results on better monitors on a visit back to Los Angeles, could he properly see the results. Hockney was elated. As he wrote in the Royal Academy catalogue, ‘Having nine separate perspectives forces the eye to scan, and it is impossible to see everything at once. This seems to make the outside edge less important, almost taking it away.… This too should make you scan, as in the real world you choose which objects to look at and in which order to do so.’ Once again, but in a highly original way that makes the earlier multi-screen experiments of mainstream cinema, such as the documentary Woodstock in 1970, look primitive, Hockney acted on his understanding of the selectivity of vision, a theme in his work first investigated as long ago as 1963.

258 May 12th 2011, Rudston to Kilham Road, 5 pm, 2011

Among the video sequences presented in ‘A Bigger Picture’, each on a bank of eighteen large monitors, were The Four Seasons, Woldgate Woods (Spring 2011, Summer 2010, Autumn 2010, Winter 2010) [259] and May 12th 2011, Rudston to Kilham Road, 5 pm [258]. The former took the viewer towards the horizon along the same road that had featured in many of the paintings and in the iPad drawings as well, in contrasting seasons; the 2011 work was one of several shot during the same few days that took a lateral view of the verge as it swept by one’s field of vision, replicating in the viewer the experience of closely examining the endlessly changing spectacle of trees, grasses, hedgerows and wild flowers as seen through the passenger’s side window. The effect of these moving pictures, shown on an endless loop, was mesmerizing and for many visitors a high point of the exhibition. Considering that Hockney had begun the Yorkshire landscape adventure with a resolution to dismiss a photographic way of seeing, nobody, least of all the artist himself, could have predicted that these investigations would find their ultimate expression through the camera.

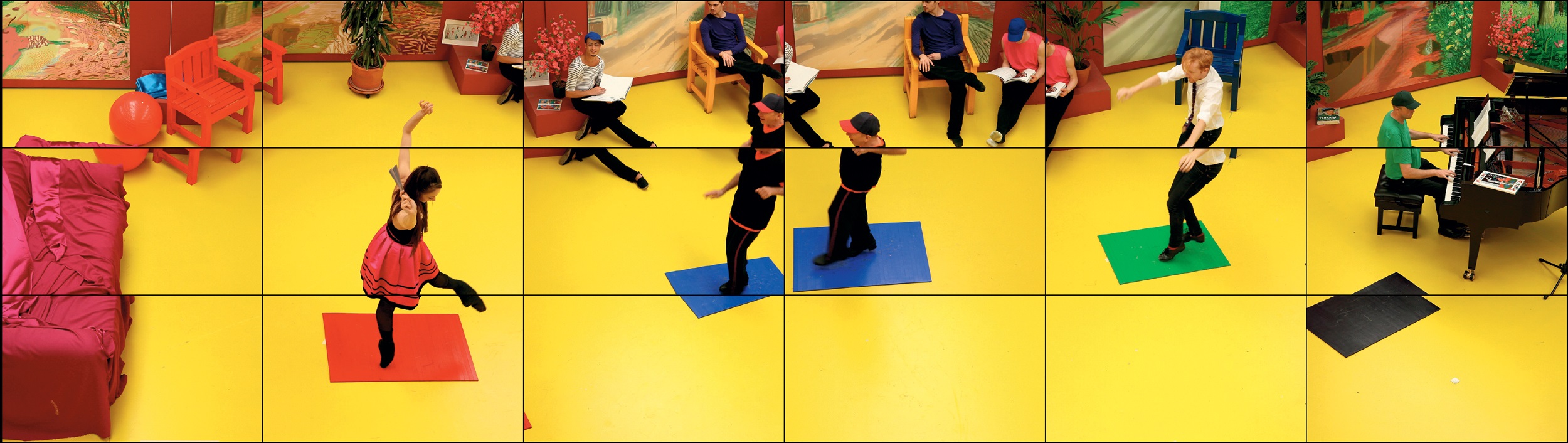

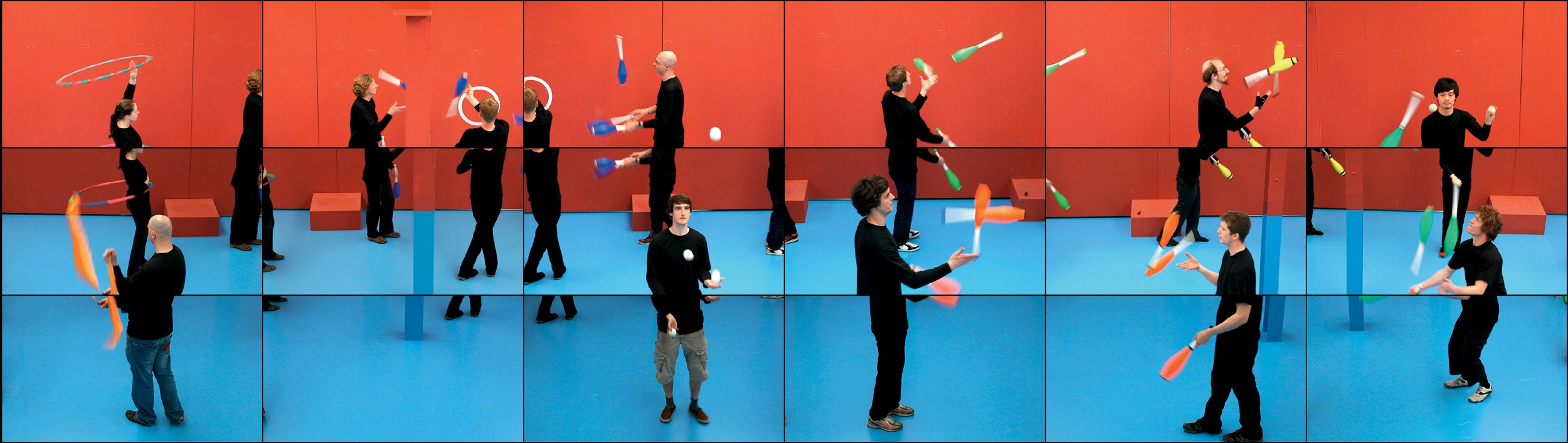

As a consummate rule-breaker and fan of impurity, Hockney could not help acting counter to the self-imposed constraint of landscape as the sole subject of his Royal Academy show by reintroducing human beings into the final video sequences. Not just any human beings, but his old friend, the celebrated ballet dancer Wayne Sleep, acting both as the choreographer and as one of a group of male and female dancers tapping their way joyfully across brightly coloured mats, to the charmingly old-fashioned strains of ‘Tea for Two’ played on the piano [260]. For these sequences, Hockney transformed the 100-by-100-foot studio that he been renting since 2008 on an industrial estate on the outskirts of Bridlington into an enormous film set, having the floor painted in a shrill yellow that set in motion a delirium of colour and movement, this time shot with eighteen cameras. However many times one watches the film, different things come to one’s notice. The darting of the dancers in and out of the separate frames, so that they sometimes seem to dematerialize and at other times appear to dance jaggedly with themselves, cannot fail to raise a smile. A later film first presented at the Museum Ludwig showing of ‘A Bigger Picture’, displaying a number of young jugglers circumnavigating the space [261], was a high point, too, of the De Young Museum’s large survey of Hockney’s recent work.

259 The Four Seasons, Woldgate Woods (Spring 2011, Summer 2010, Autumn 2010, Winter 2010), 2010–11

260 Sept. 4th 2011. The Atelier, 11.32 am: A Bigger Space for Dancing, 2011

261 The Jugglers, 2012, 2012