10.8. Flow Past a Circular Cylinder

In general, analytical solutions of viscous flows can be found (possibly in terms of perturbation series) only in two limiting cases, namely Re ≪ 1 and Re ≫ 1. In the Re ≪ 1 limit the inertia forces are negligible over most of the flow field; the Stokes-Oseen solutions discussed in the preceding chapter are of this type. In the opposite limit of Re ≫ 1, the viscous forces are negligible everywhere except close to the surface, and a solution may be attempted by matching an irrotational outer flow with a boundary layer near the surface. In the intermediate range of Reynolds numbers, analytical solutions are elusive or do not exist, and one has to depend on experimentation and numerical solutions. Some of these experimental flow patterns are described in this section, taking the flow over a circular cylinder as an example. Instead of discussing only the intermediate Reynolds number range, the experimental-observed phenomena for the entire range from small to very high Reynolds numbers is presented.

Low Reynolds Numbers

Consider creeping flow around a circular cylinder, characterized by Re = U∞d/ν < 1, where U∞ is the upstream flow speed and d is the cylinder's diameter. Vorticity is generated close to the surface because of the no-slip boundary condition. In the Stokes approximation this vorticity is simply diffused, not advected, which results in fore and aft symmetry of streamlines. The Oseen approximation partially takes into account the advection of vorticity, and results in an asymmetric velocity distribution far from the body (which was shown for a sphere in Figure 9.20). The vorticity distribution is qualitatively analogous to the dye distribution caused by a source of colored fluid at the position of the body. The color diffuses symmetrically in very slow flows, but at higher flow speeds the dye is confined behind a parabolic boundary with the dye source at the parabola's focus.

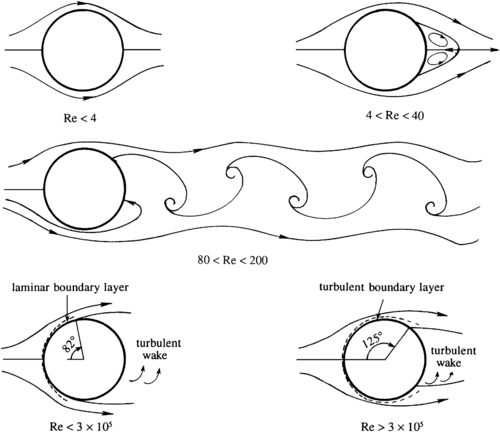

For increasing Re above unity, the Oseen approximation breaks down, and the vorticity is increasingly confined behind the cylinder because of advection. For Re > 4, two small steady eddies appear behind the cylinder and form a closed separation zone contained with a separation streamline. This zone is sometimes called a separation bubble. The cylinder's wake is completely laminar and the vortices rotate in a manner that is consistent with the exterior flow (Figure 10.18). These eddies grow in length and width as Re increases.

Moderate Reynolds Numbers

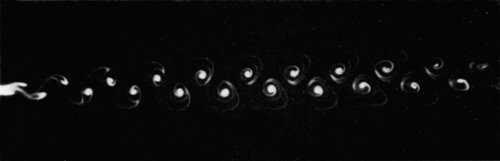

A very interesting sequence of events begins to develop when Re reaches 40, the point at which the wake behind the cylinder becomes unstable. Experiments show that for Re ∼ 102 the wake develops a slow oscillation in which the velocity is periodic in time and downstream distance, with the amplitude of the oscillation increasing downstream. The oscillating wake rolls up into two staggered rows of vortices with opposite sense of rotation (Figure 10.19). von Karman investigated the phenomenon as a problem of superposition of irrotational vortices; he concluded that a non-staggered row of vortices is unstable, and a staggered row is stable only if the ratio of lateral distance between the vortices to their longitudinal distance is 0.28. Because of the similarity of the wake with footprints on a street, the staggered row of vortices behind a blunt body is called a von Karman vortex street. The vortices move downstream at a speed smaller than U∞. This means that the vortex pattern slowly follows the cylinder if it is pulled through a stationary fluid.

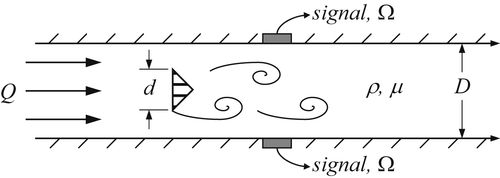

Figure 10.18 Depiction of some of the flow regimes for a circular cylinder in a steady uniform cross flow. Here, Re = U∞d/ν is the Reynolds number based on free-stream speed U∞ and cylinder diameter d. At the lowest Re, the streamlines approach perfect fore-aft symmetry. As Re increases, asymmetry increases and steady wake vortices form. With further increase in Re, the wake becomes unsteady and forms the alternating-vortex von Karman vortex street. For Re up to Recr ∼ 3 × 105, the laminar boundary layer separates approximately 82° from the forward separation point. Above this Re value, the boundary-layer transitions to turbulence, and separation is delayed to 125° from the forward separation point.

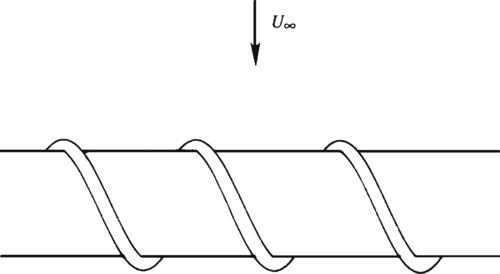

In the range 40 < Re < 80, the vortex street does not interact with the pair of attached vortices. As Re increases above 80, the vortex street forms closer to the cylinder, and the attached eddies (whose downstream length has now grown to be about twice the diameter of the cylinder) themselves begin to oscillate. Finally the attached eddies periodically break off alternately from the two sides of the cylinder. While an eddy on one side is shed, that on the other side forms, resulting in an unsteady flow near the cylinder. As vortices of opposite circulations are shed off alternately from the two sides, the circulation around the cylinder changes sign, resulting in an oscillating lift or lateral force perpendicular to the upstream flow direction. If the frequency of vortex shedding is close to the natural frequency of some structural mode of vibration of the cylinder and its supports, then an appreciable lateral vibration may be observed. Engineered structures such as suspension bridges, oil drilling platforms, and even automobile components are designed to prevent coherent shedding of vortices from cylindrical structures. This is done by including spiral blades protruding out of the cylinder's surface, which break up the spanwise coherence of vortex shedding, forcing the vortices to detach at different times along the length of these structures (Figure 10.20).

The passage of regular vortices causes velocity measurements in the cylinder's wake to have a dominant periodicity, and this frequency Ω is commonly expressed as a Strouhal number (4.102), St = Ωd/U∞. Experiments show that for a circular cylinder the value of St remains close to 0.2 for a large range of Reynolds numbers. For small values of cylinder diameter and moderate values of U∞, the resulting frequencies of the vortex shedding and oscillating lift lie in the acoustic range. For example, at U∞ = 10m/s and a wire diameter of 2 mm, the frequency corresponding to a Strouhal number of 0.2 is 1000 cycles per second. The singing of telephone and electrical transmission lines and automobile radio antennae have been attributed to this phenomenon. The value of St given here is that observed in three-dimensional flows with nominally two-dimensional boundary conditions. Moving soap-film experiments and calculations suggest a somewhat higher value of St = 0.24 in perfectly two-dimensional flow (see Wen & Lin, 2001).

Figure 10.19 von Karman vortex street downstream of a circular cylinder at Re = 55. Flow visualized by condensed milk. S. Taneda, Jour. Phys. Soc., Japan 20: 1714–1721, 1965, and reprinted with the permission of The Physical Society of Japan and Dr. Sadatoshi Taneda.

Figure 10.20 Spiral blades used for breaking up the span-wise coherence of vortex shedding from a cylindrical rod. Coherent vortex shedding can produce tonal noise and potentially large (and undesired) structural loads on engineered devices that encounter wind or water currents.

Below Re = 200, the vortices in the wake are laminar and continue to be so for very large distances downstream. Above 200, the vortex street becomes unstable and irregular, and the flow within the vortices themselves becomes chaotic. However, the flow in the wake continues to have a strong frequency component corresponding to a Strouhal number of St = 0.2. However, above a Reynolds number of several thousand, periodicity in the wake is only perceptible near the cylinder, and the wake may be described as fully turbulent beyond several cylinder diameters downstream.

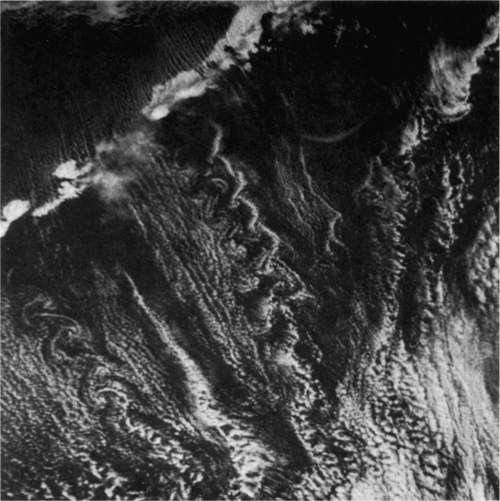

Striking examples of vortex streets have also been observed in stratified atmospheric flows. Figure 10.21 shows a satellite photograph of the wake behind several isolated mountain peaks when the wind is blowing toward the lower right of picture. The mountains pierce through the cloud level, and the flow pattern becomes visible in the cloud pattern. The wakes behind at least two mountain peaks display the characteristics of a von Karman vortex street. The strong density stratification in this flow has prevented vertical motions, giving the flow the two-dimensional character necessary for the formation of vortex streets.

High Reynolds Numbers

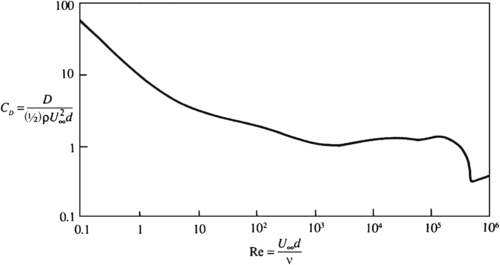

At high Reynolds numbers the frictional effects upstream of separation are confined near the surface of the cylinder, and the boundary-layer approximation is valid as far downstream as the point of separation. For a smooth cylinder up to Re < 3 × 105, the boundary layer remains laminar, although the wake formed behind the cylinder may be completely turbulent. The laminar boundary layer separates at ≈82° from the forward stagnation point (Figure 10.18). The pressure in the wake downstream of the point of separation is nearly constant and lower than the upstream pressure (Figure 10.22). The drag on the cylinder in this Re range is primarily due to the asymmetry in the pressure distribution caused by boundary-layer separation, and, since the point of separation remains fairly stationary in this Re range, the cylinder's drag coefficient CD also stays constant at a value near unity (see Figure 10.23).

Important changes take place beyond the critical Reynolds number of Recr ∼ 3 × 105. When 3 × 105 < Re < 3 × 106, the laminar boundary layer becomes unstable and transitions to turbulence. Because of its greater average near-surface flow speed, a turbulent boundary layer is able to overcome a larger adverse-pressure gradient. In the case of a circular cylinder the turbulent boundary layer separates at 125° from the forward stagnation point, resulting in a thinner wake and a pressure distribution more similar to that of potential flow. Figure 10.22 compares the pressure distributions around the cylinder for two values of Re, one with a laminar and the other with a turbulent boundary layer. It is apparent that the pressures within the wake are higher when the boundary layer is turbulent, resulting in a drop in the drag coefficient from 1.2 to 0.33 at the point of transition. For values of Re > 3 × 106, the separation point slowly moves upstream as the Reynolds number increases, resulting in a mild increase of the drag coefficient (Figure 10.23).

Figure 10.21 A von Karman vortex street downstream of mountain peaks in a strongly stratified atmosphere. There are several mountain peaks along the linear, light-colored feature running diagonally in the upper-left quadrant of the photograph. North is upward, and the wind is blowing toward the southeast. R. E. Thomson and J. F. R. Gower, Monthly Weather Review 105: 873–884, 1977; reprinted with the permission of the American Meteorological Society.

It should be noted that the critical Reynolds number at which the boundary layer undergoes transition is strongly affected by two factors, namely the intensity of fluctuations existing in the approaching stream and the roughness of the surface, an increase in either decreases Recr. The value of 3 × 105 is found to be valid for a smooth circular cylinder at low levels of fluctuation of the oncoming stream.

We close this section by noting that this flow illustrates three instances where the solution is counterintuitive. First, small causes can have large effects. If we solve for the flow of a fluid with zero viscosity around a circular cylinder, we obtain the results of Section 7.3. The inviscid flow has fore-aft symmetry and the cylinder experiences zero drag. The bottom two panels of Figure 10.18 illustrate the flow for small viscosity. In the limit as viscosity tends to zero, the flow must look like the last panel in which there is substantial fore-aft asymmetry, a significant wake, and significant drag. This is because of the necessity of a boundary layer and the satisfaction of the no-slip boundary condition on the surface so long as viscosity is not exactly zero. When viscosity is exactly zero, there is no boundary layer and there is slip at the surface. Thus, the resolution of d’Alembert’s paradox lies in the existence of, and an understanding of, the boundary layer.

Figure 10.22 Surface pressure distribution around a circular cylinder at subcritical and supercritical Reynolds numbers. Note that the pressure is nearly constant within the wake and that the wake is narrower for flow at supercritical Re. The change in the top- and bottom-side, boundary-layer separation points near Recr is responsible for the change in Cp shown.

Figure 10.23 Measured drag coefficient, CD, of a smooth circular cylinder vs. Re = U∞d/ν. The sharp dip in CD near Recr is due to the transition of the boundary layer to turbulence, and the consequent downstream movement of the point of separation and change in the cylinder's surface pressure distribution.

The second instance of counterintuitivity is that symmetric problems can have non-symmetric solutions. This is evident in the intermediate Reynolds number middle panel of Figure 10.18. Beyond a Reynolds number of ≈40, the symmetric wake becomes unstable and a pattern of alternating vortices called a von Karman vortex street is established. Yet the equations and boundary conditions are symmetric about a central plane in the flow. If one were to solve only a half problem, assuming symmetry, a solution would be obtained, but it would be unstable to infinitesimal disturbances and unlikely to be observed in a laboratory.

The third instance of counterintuitivity is that there is a range of Reynolds numbers where roughening the surface of the body can reduce its drag, the reason that golf balls have dimples. This is true for all blunt bodies. In this range of Reynolds numbers, the boundary layer on the surface of a blunt body is laminar, but sensitive to disturbances such as surface roughness, which would cause earlier transition of the boundary layer to turbulence than would occur on a smooth body. Although the skin friction of a turbulent boundary layer is much larger than that of a laminar boundary layer, most of the drag on a bluff body is caused by incomplete pressure recovery on its downstream side as shown in Figure 10.22, rather than by skin friction. In fact, it is because the skin friction of a turbulent boundary layer is much larger – as a result of a larger velocity gradient at the surface – that a turbulent boundary layer can remain attached farther on the downstream side of a blunt body, leading to a narrower wake, more complete pressure recovery, and reduced drag. The drag reduction attributed to the turbulent boundary layer is shown in Figure 10.23 for a circular cylinder and Figure 10.24 for a sphere.

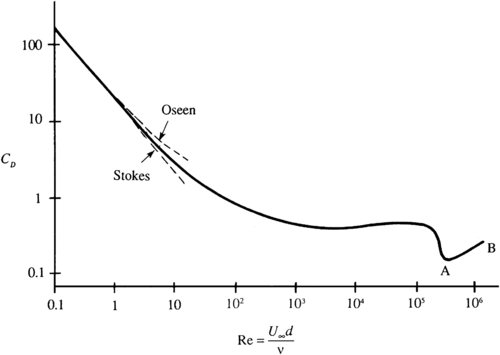

Figure 10.24 Measured drag coefficient, CD, of a smooth sphere vs. Re = U∞d/ν. The Stokes solution is CD = 24/Re, and the Oseen solution is CD = (24/Re) (1 + 3Re/16); these two solutions are discussed at the end of Chapter 9. The increase of drag coefficient in the range A–B has relevance in explaining why the flight paths of sports balls bend in the air.