Introduction

Researchers define hospitality in various ways. Telfer (1996: 83) defines hospitality as “the giving of food, drink and sometimes accommodation to people who are not regular members of a household”. Being hospitable to strangers or customers involves motives based on a desire to please customers or to fulfil moral obligations (see Chapter 1, this volume). In some situations, providers may combine personal and commercial motivations for hospitality. Tideman (1983: 1) defines hospitality from the perspective of economic exchange that involves “a supply of goods and services in a quantity and quality desired by the guest and at a price that is acceptable to him so that he feels the product is worth the price”. In addition to personal motivations and economic exchange, lodging businesses also provide security and protection that “extend to all, irrespective of status or origins” (Lashley 2008: 71).

Relatively few studies acknowledge commercial hospitality in religious contexts. Studies on the provision of hospitality to pilgrims (Cohen 1992; Hill 2002; O’Gorman 2007; Timothy & Iverson 2006), for example, emphasise religious activities and attractions while others focus on religious and spiritual tourism (Cochrane 2009; Haq & Wong 2010; Huntley & Barnes-Reid 2003). Hence, little research exists on an in-depth understanding of hospitality business in a religious context (Din 1989; Weidenfeld 2006; Kirillova, Gilmetdinova & Lehto 2014). Commercial hospitality businesses primarily emphasise monetary transactions although the social and religious aspects of hospitality are still important in some cultures (Chambers 2009) depending on how countries ascribe value to the religious context. Therefore, understanding the religious dimensions of hospitality remains important in enabling providers to understand the current and future needs of customers (O’Connor 2005).

Halal hospitality

Growth in travel for leisure and business by Muslims has created interest in their travel needs, including accommodation, food services, transportation, and attractions (Sahida, Rahman, Awan & Man 2011). The need to respond to Islamic values in a commercial tourism and hospitality setting has generated awareness of halal products and services targeting the Islamic market. The commercial fulfilment of halal requirements for Muslim travellers is referred to as halal hospitality, while the demand for halal hospitality services when customers are on leisure holiday or engaging in business travel, is usually referred to as halal tourism. Importantly, due to changing patterns of international migration, travel flows, and halal hospitality, the concept has also been introduced to non-Muslim countries (Kamali 2011). However, in Muslim countries, the notion of services being halal has long been taken as given.

Due to commercial and religious interest in the Muslim market, many accommodation providers offer halal products and services (Wilson et al. 2013; see also Chapter 2, this volume). Nevertheless, the area is greatly under-researched (Stephenson 2014). Much of the available literature focuses on halal food certification (Zailani, Fernando & Mohamed 2010; Razalli, Yusoff, & Mohd Roslan 2013; Samori, Ishak & Kassan 2014) and the restaurant sector (Gayatri, Hume & Mort 2011; Marzuki, Hall & Ballantine 2014; Prabowo, Abd & Ab 2012) rather than on the larger picture of what constitutes halal in a hospitality setting.

Hospitality in the Islamic context is more than just a technical or commercial service, rather it should be understood as part of a particular set of social relationships embedded within a broader spiritual significance. Although this dimension of halal and hospitality is still limited in the literature, arguably it underpins the services provided to guests by providers who embrace the halal concept, and potentially the broader orientation towards their customers as noted in the Quran.

Has the story reached you, of the honoured guests [three angels: Jibrael (Gabriel) along with another two] of Ibrahim (Abraham)? When they came in to him, and said, “Salam, (peace be upon you)!” He answered; “Salam, (peace be upon you),” and said: “You are a people unknown to me,” Then he turned to his household, so brought out a roasted calf [as the property of Ibrahim (Abraham) was mainly cows]. And placed it before them, (saying): “Will you not eat?”

(Surah adz-Dzaariyaat, 24–27)

The concept of hospitality has numerous dimensions. Lashley and Morrison (2000) suggest that it involves social (i.e. obligation according to culture/religion), private (i.e. hospitality offered at home), and commercial (e.g. host–guest relationship) dimensions. In this chapter, we add a technical dimension of hospitality, which refers to the products and services provided by accommodation providers to meet religious requirements. Although the social and commercial dimensions of hospitality are widely discussed in previous studies (Marci 2013; McMillan, O’Gorman & MacLaren 2011), there is relatively limited knowledge of these two dimensions in an Islamic context. The interpretation of halal comes from the authority of the Quran and the Sunnah that prescribes the way of life for Muslims, and also from government and religious institutions that can regulate products and services referred to as Shariah or halal requirements (Halal Malaysia 2014). Shariah compliance or halal hospitality is characterised according to halal requirements. Razzaq et al. (2016) identified 37 halal attributes for accommodation business (Table 4.1) based on several studies including Stephenson (2014), Battour, Ismail and Battor (2011), and Henderson (2010). These attributes inform customers about the halal services offered and are useful for tourism purposes especially for the positioning of Malaysia as a global halal hub.

| No. | Item | 19 | Gym on-site |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mentions halal | 20 | Proximity to gambling venues |

| 2 | Multilingual | 21 | Serves food on their premises |

| 3 | Family-friendly | 22 | Has in-unit cooking facilities |

| 4 | Pet-friendly | 23 | Has a dining establishment on-site |

| 5 | Proximity to ‘red light’ district | 24 | Alcohol is served on-site |

| 6 | Can cater to specific religious needs | 25 | Has a bar on-site |

| 7 | Can provide prayer time | 26 | Has room service |

| 8 | Can provide a prayer mat | 27 | Has a mini-bar |

| 9 | Can provide a copy of the Quran | 28 | Certified halal items |

| 10 | Provides Sky television (TV service) | 29 | Vegetarian options |

| 11 | Provides DVD players | 30 | Gluten-free options |

| 12 | Provides satellite or cable television | 31 | Dairy-free options |

| 13 | Provides multilingual TV channels | 32 | Offers off-premises food options |

| 14 | Provides movies | 33 | Able to cater to special dietary needs |

| 15 | Pool on-site | 34 | Has a Qibla marker |

| 16 | Spa bath or pool on-site | 35 | Has a special prayer facility on-site |

| 17 | Day spa on-site | 36 | Female-only floor |

| 18 | Sauna on-site | 37 | Gender-segregated facilities |

Source: Adapted from Razzaq et al., 2016: 95.

Halal hospitality in a Malaysian context

Malaysia is actively promoting halal tourism and hospitality as part of its aim to be the world’s halal hub (Ministry of Finance, Malaysia 2011). Hence, awareness of halal issues has increased among providers in the accommodation sector (Samori et al. 2014). Income from the tourism industry increased from RM53.4 billion in 2009 to RM65.44 billion in 2013 (Ministry of Tourism and Culture, Malaysia (MOTOUR), 2014), indicating the continuing growth of the industry in terms of tourist arrivals and expenditure. However, there is limited knowledge available on halal in the accommodation context as many halal hospitality studies have emphasised mainly the food dimension (Mohd Shariff & Abd Lah 2014; Bohari, Hin & Fuad 2013; Ratnamaneichat & Rakkarn 2013).

Currently, much of the accommodation in Malaysia, including hotels, resorts, and homestays, are promoted as providing halal hospitality (Sahida, Zulkifli, Rahman, Awang & Man 2014). In the Malaysian context, websites have proven to be the fastest and cheapest way to become a one-stop centre to offer halal information (Halal Dagang 2013) and can help providers to promote halal hospitality and offer better customer service (Nasution & Mavondo 2008), increase potential customers and sales (Hashim 2008), and provide online booking services (Díaz & Koutra 2013; Tian & Wang 2017). However, accommodation providers do not always fully utilise the advantages provided by a website (De Marsico & Levialdi 2004). Therefore, it is important to evaluate the extent to which website information satisfies customer needs (Dragulanescu 2002). Razzaq et al. (2016), for example, state that it is important to create awareness and promote halal service offerings to Muslim tourists through accommodation providers’ websites. In their study only 3 out of the 367 accommodation providers’ websites analysed for Auckland and Rotorua mentioned halal in their hospitality offering. However, so far, no study has been carried out on halal attributes published on the websites of accommodation providers in Malaysia. Using the halal attributes proposed by Razzaq et al. (2016), a similar analysis of providers’ websites was conducted in this study.

The provision of halal hospitality involves both Muslim and non-Muslim accommodation providers (Alserhan 2010) as motivations to provide halal products and services may potentially lie beyond religious motivations. Although the potential significance of Islamic tourism and halal hospitality has been recognised in the Malaysian context (Sahida et al. 2014), no specific research has been conducted into Malaysian accommodation providers’ understanding of halal hospitality as indicated by the information provided on their websites. Given the growth of academic and industry interest in halal tourism and hospitality, such research may have significant implications for service provisions and providing a deeper understanding of the notion of halal from a supply perspective than has previously been the case. However, there is no detailed research available on how Malaysian accommodation providers understand the concept of halal hospitality, and the implications that this has for service provision (Ab Talib & Mohd Johan 2012). Moreover, in the New Zealand context, it was noted that in some cases businesses would not display certification for halal foods, even though they may have had it because they felt that as ‘good Muslims’ their words should be sufficiently trusted (Wan Hassan & Hall 2003; Wan Hassan 2008). No research exists to understand whether the same situation may exist in Malaysia. This study therefore aims to examine the understanding of halal hospitality among Malaysian accommodation providers with the aim of furthering our understanding of not only commercial and technical aspects of hospitality and halal services but also social dimensions of hospitality, particularly within an Islamic context.

Data collection

This study uses a sequential mixed-methods approach. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 16 Muslim and 2 non-Muslim respondents (i.e. from hotels, budget hotels, homestays/lodges, and chalets) to explore their understanding of halal hospitality as influenced by their perceptions, religious beliefs, and experience in commercial hospitality settings (Kirillova et al. 2014). The interviews were guided by a set of open-ended research questions that allowed respondents to elaborate on their perceptions and beliefs. This qualitative phase was followed by a quantitative analysis of the halal hospitality attributes (Razzaq et al. 2016) that could be identified from 781 websites of accommodation providers in Malaysia obtained from the Ministry of Tourism and Culture Malaysia (MOTAC) website at www.motac.gov.my/.

Findings

The interview findings are presented in two themes. First, accommodation providers’ understanding of halal hospitality are elaborated upon followed by accommodation providers’ own perspectives of halal hospitality business.

The accommodation providers’ understanding of halal hospitality

The findings indicated that many Muslim respondents understood halal hospitality as per Islamic teaching and according to their own understanding and interpretation of this teaching. These respondents believed that one must provide halal hospitality as per religious requirements as illustrated in the following two quotes.

We are Muslims; therefore, we must provide halal services. (Respondent N)

We are Muslims and we are accountable to provide the right service to the customers. We have to be answerable in the hereafter for all our acts. (Respondent P)

These respondents believed that they must avoid haram activities and be responsible to themselves and others. They believed that it is their responsibility to remind others of religious obligations and thus having signage, giving advice, and preventing haram activities could encourage customers to follow Islamic obligations. They also emphasised that being an accomplice to vices is a sin, hence religious obligations should be presented as part of the business offering as illustrated in the quotes here.

It is a responsibility of a Muslim to remind other Muslims about religious obligations. Providing halal hospitality is one way of doing dakwah (proselytisation) to people. (Respondent B)

We do not want to be accomplices for anything haram. We monitor the youngsters that come here so that there are no haram activities … we do not want to be accomplices …We have to take care of our responsibilities as Muslims. (Respondent O)

I do not compromise in letting non-married couples stay together. This is always a problem for any hotel businesses. If we allow them to stay here, then we are also an accomplice to the vice and have to also bear the sin. (Respondent Q)

By affirming that their business practised halal hospitality, respondents expected customers to respect the halal status and cooperate with the Jabatan Agama Kemajuan Islam Malaysia (JAKIM) for inspections to prevent vices at their premises. This is exemplified by the business practices put in place as illustrated in the quotes below. However, it must be noted that businesses cannot fully control the type of haram activities that customers may engage in.

We do not serve or allow any alcoholic drinks even to non-Muslim foreigners. If the customers bring their own alcoholic drinks without our knowledge, then that is beyond our control. (Respondent R)

To avoid vices here, we hope that once people know that this is a Shariah compliant hotel, they will stop from doing any vice here. Although we do not allow them, we do not have the authority to stop them. Only the relevant authority can. (Respondent B)

In Islam, we cannot force people to follow our rules. In my opinion, we only can prevent. We are a business, we need to think of many factors in implementing halal requirements, for example, where we work, our government, the laws gazetted, and other factors. We can put up signage to remind about Islamic rules but the most important is the individuals themselves, if they want to go against the rules, we cannot do anything … We have many foreigners, we do not know whether they are Muslims or not, we just need to avoid any activities against our practices. (Respondent A)

Muslims respondents believed that they will receive spiritual rewards for good deeds. They will not be rewarded for mixing halal and haram activities in their hospitality service. The respondents thought that it is important to preach to non-Muslims about halal as it is a responsibility to spread the religion to others. Muslim respondents believed that halal means no harm to anybody and Muslims and non-Muslims gain benefits from halal hospitality. These ideas are illustrated in these quotes:

The most important thing is our intention … As a Muslim, you have to believe that when you do good, you are rewarded. (Respondent N)

It is one of our intentions to preach to non-Muslims to get them to understand what is halal and why do the Muslims do it. (Respondent E)

If we carry out our deeds with the intention to do good, this becomes part of worship. (Respondent H)

It is all about the sustenance that Allah SWT provides for me. If we mix the halal with the haram, we won’t be rewarded. (Respondent O)

Halal is not necessarily only for Muslims actually, non-Muslims too, great. Things that are halal, means pure right, the way it is clean, the way its handled and all, certainly, there’s no doubt. (Respondent G)

Respondents believed that avoiding haram could increase the spiritual feeling (intrinsic value) of being closer to Allah hence they were concerned about the mixing of halal and haram sources. Any contamination requires ritual cleanliness to avoid impurity to one’s soul as shown in the quotes below.

Basically, it means not to mix with whatever that is haram. So, our income if possible, should not be mixed with haram sources. (Respondent R)

We cannot eat haram food, it will generate negativity in oneself, soul, and body, and indirectly in the future, until one dies. If one’s eat or is involved with many haram things, sin is one part, it is between oneself with God, but if the haram thing is already in one’s soul, it will be there, it will always have some influence on one’s soul as it has become part of our flesh and blood, and will be very difficult to remove. (Respondent A)

I have my own rules and regulations that I enforce at my accommodation … there is a notice of no beer, no liquor, and no pork. We do not want our place to be unclean. (Respondent M)

For me there is a bit of reservations towards non-Muslims. It is all right for them to stay, but no barbeque as I am not confident and such because they may have non-halal food. That would be a problem to me. (Respondent O)

The respondents also condemned unethical conducts such as misuse of the halal logo and having the halal certificate but not following the requirements, as illustrated in the following quotes.

We have to be more careful about the misuse of halal and the halal logo. The authorities say its halal but in reality, it is not halal, but so many people have eaten or used that thing. They have to answer to that in the hereafter. (Respondent I)

If we can obtain the certificate, but don’t follow it, then it’s of no use. (Respondent E)

The accommodation providers’ own perspectives on halal hospitality business

The respondents mentioned that hospitality in a commercial context requires them to follow Shariah requirements such as halal certification, Islamic funding, facility design, staff training, entertainment, and the management of halal hospitality business. The respondents believed that riba (interest) is haram, therefore, conventional financing must be avoided. Some respondents removed entertainment activities and replaced them with Islamic entertainment (see Al Qaradawi 1960). The respondents also believed that top management is responsible for providing halal-related training for staff and the availability of halal advisers to manage halal certification processes. These ideas are illustrated in the quotes below.

Hospitality is a service. If you combine it with halal, then you must adhere to all the requirements. For us here, for halal hospitality, we have to be Shariah compliant. (Respondent A)

It is difficult for me to explain halal hospitality. For halal hospitality, you need certification, and staffs have to be trained on how to handle the preparation, the process, know the suppliers and things like that. (Respondent P)

People are reassured as halal is not just about the food, but it’s concerned with the cleanliness, the preparation, the ingredients, even imported ingredients. (Respondent N)

Firstly, if we really want to do halal, the design, for example, the toilet cannot be facing the Qibla. Secondly, when we start, even from financing, we need to find a halal financing. Don’t take the conventional financing. Thirdly, we really have to make sure the customers that come to the hotel follow our guidelines. If we really want to be strict, they have to be in hijab to stay at this hotel, but then we are not up that level yet, for halal hospitality. (Respondent E)

Previously, we had an in-house band in the upstairs lounge, we had snooker tables. Now we do not have these anymore. There is a TV in every room, but not with all channels. There are news channels, sports, family and films … We have eliminated all alcohol, wine. (Respondent C)

We have a panel of Shariah advisors, so any enhancements or changes; we have to inform them first. We have these advisors to make sure we are doing the right thing. (Respondent B)

Many respondents viewed halal hospitality as an opportunity for them to undertake a hospitality-related business; thus their business is designed according to halal principles. The respondents viewed that halal offerings attract businesses in other industries to engage in halal business as illustrated in the quotes below.

If we do non-halal, people won’t come. So it is better to orient towards halal hospitality because our main customers are Muslims. (Respondent K)

We don’t have many corporate clients. We get more customers from government organisations, so being halal is important. Moreover, one more thing, the majority of our staff here are Malay Muslims. Our guests too are local Muslims. (Respondent C)

It gives us the opportunities to do business with the government. (Respondent N)

Other hotels that have non-Muslims upper management may not be able to do halal hospitality like we do. However, the non-Muslims are also seeing the halal concept as a business opportunity, for example, Rayani Air. It is owned by a non-Muslim but it is Shariah compliant. (Respondent B)

Findings from the analysis of accommodation providers’ websites

Given some of the findings of the qualitative research where emphasis on certain attributes and practices were seen as an important indicator of a business offering halal hospitality, the next stage of the analysis was to identify the most common halal attributes presented online by accommodation providers. This provides an insight into how they communicate halal hospitality to their customers. Despite accommodation providers showing some knowledge of halal hospitality and the attributes that customers are searching for to know if a provider is offering halal services, many of the halal attributes identified in this study were not mentioned on the accommodation websites.

The websites of accommodation providers analysed in this study are from businesses located in the Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur (17 per cent), followed by Sabah (11.8 per cent), Selangor (9.5 per cent), Pahang (8.8 per cent), Johor (8.6 per cent), Melaka (7.7 per cent), Pulau Pinang (6.4 per cent), Perak, Sarawak (5.8 per cent), Kedah (5 per cent), and Terengganu (4.9 per cent), among others. More than 50 per cent of these accommodation providers are hotels, followed by budget hotels (39.7 per cent), chalets (2.4 per cent), and homestay/guesthouse/rest house/hostels (1.4 per cent). In Malaysia, a business with 50 rooms and above is considered to be a large size while one with 10 to 49 rooms is considered to be an accommodation provider of medium size. Based on these criteria, about 70 per cent of the accommodation providers belong to the large size category followed by 29 per cent for medium size.

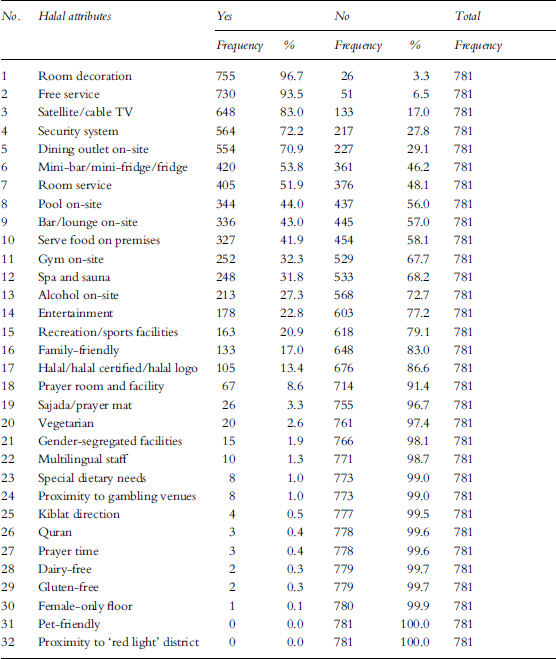

The halal attributes were ranked from the most frequently mentioned to the least, for easy reference (Table 4.2). The findings from the website analysis showed that the technical dimensions of halal hospitality as proposed by Razzaq et al. (2016) were those most commonly communicated on the websites. Specifically, attributes such as service and security, generally considered important in commercial hospitality (Aramberri 2001; King 1995; Kirillova et al. 2014), were among the most commonly communicated. For example, 72.2 per cent of the websites reported having a security system while 93.5 per cent offered some form of free service. In Islam, generosity is encouraged, thus free or complimentary service can be an important aspect of hospitality. Surprisingly, gender-segregated facilities, which are a hallmark of halal hospitality, were mentioned on only 1.9 per cent of the websites. The halal attributes that communicate halal hospitality are not necessarily the attributes emphasised on these websites.

Other attributes that were among the most frequently mentioned on the websites were room decoration (96.7 per cent), satellite/cable (83 per cent), and dining outlet on-site (70.9 per cent). Although Malaysia is actively promoting itself as an international halal hub and has its halal certification, only 105 or 13.4 per cent of the 781 websites mentioned halal, being halal certified, or included a halal logo. Other specific halal attributes, such as prayer room, prayer mat, gender-segregated facilities, kiblat direction, Quran, prayer time, and female-only floor, are rarely mentioned on the websites as can be seen in Table 4.2. Although it has been argued that possessing a halal certificate has a commercial value for businesses in attracting demand for halal products and services from local and international customers (Abdullah et al. 2016), the present study found that only 18.4 per cent of accommodation providers were halal certified by JAKIM. There seems to be an important gap between halal attributes communicated to customers and the positioning of these accommodation providers for their customer base.

Discussion and conclusion

This study argues that an understanding of halal hospitality needs to include the broader fulfilment of religious obligations under Islam. Muslim respondents believed that as a sign of faith (Mukhtar & Butt 2012) they must avoid haram and promote halal activities. They also believed in getting rewards and punishments in this world and the world hereafter. While these beliefs underpin the findings from the qualitative research undertaken with accommodation providers, the same cannot be said about how the concept of halal hospitality is communicated on these providers’ websites. There are obvious differences between the findings of the qualitative and quantitative phases reported in this study, with the former emphasising the importance of religious beliefs and compliance to rules with few of the attributes depicting these beliefs and compliance reported on websites.

From the qualitative phase, respondents stressed halal attributes that conveyed their practice of halal hospitality included Islamic funding, ritual cleanliness, and acceptable entertainment in conformance to religious teachings. These attributes were perceived as differentiating halal hospitality from conventional hospitality. However, from the quantitative findings, it is clear that attributes depicting conventional hospitality such as free service, satellite/cable TV, and room decoration are some of the most commonly reported attributes on the websites. While the interview participants gave priority to religious obligations to keep their Islamic faith even if they have limited number of customers following Islamic rules, the findings from the website analysis show that little of these religious requirements are communicated.

Islam permits Muslims to enjoy entertainment so long as halal and haram elements, such as intoxication, obscenity, gambling, and inappropriate mixing of men and women, are not combined (Al Qaradawi 1960). In conventional hospitality services, common entertainment activities such as an in-house band, the provision of snooker tables, or karaoke, involve haram elements; hence replacing these with halal entertainments could satisfy Muslim customers’ needs (Fikri, Rugayah & Tibek 2014). However, it is clear from the findings of the website analysis that 27.3 per cent served alcohol on-site and 53.8 per cent had a mini-bar or mini-fridge. While the former may be due to a proportion of customers being non-Muslim and therefore the accommodation provider is catering for this market, the latter suggests that there is potentially some mixing of halal and haram. It must be acknowledged that customers will choose goods or services that reflect their taste, social status or religious beliefs (Eum 2009), and price, and the fact that the websites of accommodation providers emphasise more commercial rather than halal hospitality requirements is not necessarily surprising. Striking a balance between commercial and religious interests in managing a hospitality business can be difficult. Though one would expect Muslim providers to understand halal hospitality better than non-Muslim providers, there is no evidence to suggest this based on the analysis of the websites. Without a clear understanding of the halal hospitality concept, contamination, violation, or misuse of the halal logo will likely occur (Zakaria 2008).

One key recommendation that can be made on the basis of the findings of this study is that an accommodation management that is driven by halal hospitality processes (Ismaeel & Blaim 2012) should include explicit references to halal income, investment, and financing that clearly portray adherence to religious beliefs. Accommodation providers should also provide training to staff with respect to not only commercial and technical dimensions of halal hospitality but also its social dimensions. Mentoring schemes where a panel of halal advisers is made available to accommodation providers to guide halal businesses and the delivery of halal hospitality should be put in place in the accommodation sector of Malaysia. As indicated by interview participants, it is important to provide services that reinforce a positive image of halal hospitality, as suggested in other studies (e.g. Ivanova & Ivanov 2015).

Accommodation providers should also utilise the advantages of online marketing tools and proactively promote the halal hospitality attributes as they are the cheapest and most efficient means available of reaching potential Muslim customers. However, the findings showed that little information is available on halal hospitality attributes even on the websites of halal-certified accommodation providers in Malaysia. For accommodation providers, publishing information on their desirable halal attributes could help them to reach their halal business objectives. Nevertheless, the overall findings from the website analysis in Malaysia are no different from those in New Zealand (Razzaq et al. 2016), raising significant questions about what is stated with respect to halal information and offerings and what is actually offered. These findings may also reflect a concern among providers that mentioning halal explicitly in their business promotion may deter some customers (Razzaq et al. 2016). Alternatively, it may be that there is no perceived need for halal assurance to be provided if most customers are Muslims.

In conclusion, the concept of halal hospitality is claimed to be important in marketing to the Islamic market in both Muslim and non-Muslim countries, but accommodation providers need a better understanding of what halal hospitality and attributes are. Just as significantly a far better understanding is needed of the substantial gap that appears to exist between market information needs and what is provided by accommodation businesses, especially the reasons for non-declaration of halal. It is hoped that improved understandings of halal hospitality concepts can help cater to the perceived demand for halal tourism and hospitality.

References

Ab Talib, S.M. and Mohd Johan, M.R. (2012) ‘Issues in halal packaging: A conceptual paper’, International Business and Management, 5 (2): 94–98.

Abdullah, M., Syed Ager, S.N., Hamid, N.A.A., Wahab, N.A., Saidpudin, W., Miskam, S. and Othman, N. (2016) ‘Isu dan cabaran pensijilan halal: Satu kajian perbandingan antara Malaysia dan Thailand’. In World Academic and Research Congress 2015 (World-AR 2015). Jakarta, Indonesia.

Al-Qaradawi, Y. (1960) The Lawful and Prohibited in Islam. [ebook]. Available at: https://thequranblog.files.wordpress.com/2010/06/the-lawful-and-the-prohibited-in-islam.pdf (accessed 25 November 2015).

Alserhan, B.A. (2010) ‘On Islamic branding: Brands as good deeds’, Journal of Islamic Marketing, 1 (2): 101–106.

Aramberri, J. (2001) ‘Paradigms in the tourism theory’, Annals of Tourism Research, 28 (3): 738–761.

Battour, M., Ismail, M.N. and Battor, M. (2011) ‘The impact of destination attributes on Muslim tourist’s choice’, International Journal of Tourism Research, 13 (6): 527–540.

Bohari, A.M., Hin, C.W. and Fuad, N. (2013) ‘The competitiveness of Halal food industry in Malaysia: A SWOT–ICT analysis’, Malaysia Journal of Society and Space, 1: 1–9.

Chambers, E. (2009) ‘From authenticity to significance: Tourism on the frontier of culture and place’, Futures, 41 (6): 353–359.

Cochrane, J. (2009) ‘Spirits, nature and pilgrimage: The “other” dimension in Javanese domestic tourism’, Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion, 6 (2): 107–119.

Cohen, E. (1992) ‘Pilgrimages and tourism: Convergence and divergence’. In A. Moranis (ed.) Sacred Journeys: The Anthropology of Pilgrimage. New York: Greenwood Press, 47–61.

De Marsico, M. and Levialdi, S. (2004) ‘Evaluating web sites: Exploiting user’s expectations’, International Journal of Human–Computer Studies, 60 (3): 381–416.

Díaz, E. and Koutra, C. (2013) ‘Evaluation of the persuasive features of hotel chains websites: A latent class segmentation analysis’, International Journal of Hospitality Management, 34: 338–347.

Din, K.H. (1989) ‘Islam and tourism: Patterns, issues, and options’, Annals of Tourism Research, 16 (4): 542–563.

Dragulanescu, N.-G. (2002) ‘Website quality evaluations: Criteria and tools’, International Information & Library Review, 34 (3): 247–254.

Eum, I. (2009) ‘A study on Islamic consumerism from a cultural perspective: Intensification of Muslim identity and its impact on the emerging Muslim market’, International Area Studies Review, 12 (2): 3–19.

Fikri, S., Rugayah, S. and Tibek, H. (2014) ‘Nasyid as an Islamic alternative entertainment’, IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 19 (7): 43–48.

Gayatri, G., Hume, M. and Mort, S.G. (2011) ‘The role of Islamic culture in service quality research’, Asian Journal on Quality, 12 (1): 35–53.

Halal Dagang. (2013) ‘Halal e-market place’. [Online] Available at: www.daganghalal.com/(accessed 20 March 2014).

Halal Malaysia. (2014) ‘Manual prosidur pensijilan Halal Malaysia’, JAKIM, Putrajaya. [Online] Available at: www.halal.gov.my/v4/index.php?data=bW9kdWxlcy9uZXdzOzs7Ow==&utama=panduan&ids=gp4 (accessed 20 March 2014).

Haq, F. and Wong, H.Y. (2010) ‘Is spiritual tourism a new strategy for marketing Islam?’, Journal of Islamic Marketing, 1 (2): 136–148.

Hashim, N.H. (2008) Investigating internet adoption and implementation by Malaysian hotels: An exploratory study. PhD. University of Western Australia.

Henderson, J.C. (2010) ‘Sharia-compliant hotels’, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 10 (3): 246–254.

Hill, B. (2002) ‘Tourism and religion, by Boris Vukonic’, International Journal of Tourism Research, 4 (4): 327–328.

Huntley, E. and Barnes-Reid, C. (2003) ‘The feasibility of Sabbath-keeping in the Caribbean hospitality industry’, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 15 (3): 172–175.

Ismaeel, M. and Blaim, K. (2012) ‘Toward applied Islamic business ethics: Responsible halal business’, Journal of Management Development, 31 (10): 1090–1100.

Ivanova, M. and Ivanov, S. (2015) ‘Affiliation to hotel chains: Hotels’ perspective’, Tourism Management Perspectives, 16: 148–162.

Kamali, M.H. (2011) ‘Tourism and the halal industry: A global shariah perspective’. In World Islamic Tourism Forum 2011. [Online] Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 12–13. Available at: www.iais.org.my/e/attach/ppts/12-13JUL2011-WITF/ppts/Prof%20Dr%20Hashim%20Kamali.pdf (accessed 8 December 2013).

King, C.A. (1995) ‘Viewpoint: what is hospitality?’, International Journal of Hospitality Management, 14 (3/4): 219–234.

Kirillova, K., Gilmetdinova, A. and Lehto, X. (2014) ‘Interpretation of hospitality across religions’, International Journal of Hospitality Management, 43: 23–34.

Lashley, C. (2008) ‘Studying hospitality: Insights from social sciences’, Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 8 (1): 69–84.

Lashley, C. and Morrison, A. (eds) (2000) In Search of Hospitality: Theoretical Perspectives and Debates. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Marci, T. (2013) ‘Social inclusion in terms of hospitality’, International Review of Sociology, 23 (1): 180–200.

Marzuki, S.Z., Hall, C.M. and Ballantine, P.W. (2014) ‘Measurement of restaurant manager expectations toward halal certification using factor and cluster analysis’, Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 121: 291–303.

McMillan, C.L., O’Gorman, K.D. and MacLaren, A.C. (2011) ‘Commercial hospitality: A vehicle for the sustainable empowerment of Nepali women’, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 23 (2): 189–208.

Ministry of Finance, Malaysia. (2011) Economic Management and Prospect. Kuala Lumpur: Ministry of Finance, Malaysia.

Ministry of Tourism and Culture, Malaysia. (2014) Rated Tourist Accommodation Premises. [Online] Available at: www.motac.gov.my/en/check/hotel?h=&n=&v=0 (accessed 15 February 2015).

Mohd Shariff, S. and Abd Lah, N. (2014) ‘Halal certification on chocolate products: A case study’, Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 121: 104–112.

Mukhtar, A. and Butt, M.M. (2012) ‘Intention to choose halal products: The role of religiosity’, Journal of Islamic Marketing, 3 (2): 108–120.

Nasution, H.N. and Mavondo, F.T. (2008) ‘Customer value in the hotel industry: What managers believe they deliver and what customer experience’, International Journal of Hospitality Management, 27 (2): 204–213.

O’Connor, D. (2005) ‘Towards a new interpretation of “hospitality”’, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 17 (3): 267–271.

O’Gorman, K.D. (2007) ‘Dimensions of hospitality: Exploring ancient and classical origins’. In C. Lashley, P. Lynch and A. Morrison (eds) Hospitality: A Social Lens. Oxford: Elsevier, 17–32.

Prabowo, S., Abd, A. and Ab, S. (2012) ‘Halal culinary: Opportunity and challenge in Indonesia’. In International Halal Conference. Kuala Lumpur: PWTC, 1–10. Available at: www.sciencedirect.com (accessed 8 December 2013).

Ratanamaneichat, C. and Rakkarn, S. (2013) ‘Quality assurance development of halal food products for export to Indonesia’. In Social and Behavioral Sciences Symposium, 4th International Science, Social Science, Engineering and Energy Conference 2012. Bangkok, 134–141. Available at: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.08.488 (accessed 5 May 2014).

Razalli, M.R., Yusoff, R.Z. and Mohd Roslan, M.W. (2013) ‘A framework of halal certification practices for hotel industry’, Asian Social Science, 9 (11): 316–326.

Razzaq, S., Hall, C.M. and Prayag, G. (2016) ‘The capacity of New Zealand to accommodate the halal tourism market—Or not’, Tourism Management Perspective, 18: 92–97.

Sahida, W., Rahman, S.A., Awan, K. and Man, Y.C. (2011) ‘The implementation of Shariah compliance concept hotel: De Palma Hotel Ampang, Malaysia’. In 2nd International Conference on Humanities, Historical and Social Sciences. Singapore: IPEDR, 138–142.

Sahida, W., Zulkifli, W., Rahman, S.A., Awang, K.W. and Man, Y.B.C. (2014) ‘Developing the framework for halal friendly tourism in Malaysia’, International Business Management, 5 (6): 295–302.

Samori, Z., Ishak, A.H. and Kassan, N.H. (2014) ‘Understanding the development of halal food standard: Suggestion for future research’, International Journal of Social Science and Humanity, 4 (6): 482–486.

Stephenson, M.L. (2014) ‘Deciphering “Islamic hospitality”: Developments, challenges and opportunities’, Tourism Management, 40: 155–164.

Telfer, E. (1996) Food for Thought: Philosophy and Food. London: Routledge.

The Noble Quran. (2010) Interpretation of the meanings of the Noble Quran. [Online] Available at: www.noblequran.com/translation/(accessed 18 November 2014).

Tian, J. and Wang, S. (2017) ‘Signaling service quality via website e-crm features more gains for smaller and lesser known hotels’, Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research, 41 (2): 211–245.

Tideman, M.C. (1983) ‘External influences on the hospitality industry’. In E.H. Cassee and R. Reuland (eds) The Management of Hospitality. Oxford: Pergamon, 1–24.

Timothy, D.J. and Iverson, T. (2006) ‘Tourism and Islam: Considerations of culture and duty’. In D.J. Timothy and D.H. Olsen (eds) Religion and Spiritual Journeys. New York: Routledge, 186–205.

Wan-Hassan, W.M. (2008) Halal Restaurants in New Zealand: Implications for the Hospitality and Tourism Industry. PhD. University of Otago.

Wan-Hassan, W.M. and Hall, C.M. (2003) ‘The demand for halal food among Muslim travellers in New Zealand’. In C.M. Hall, L. Sharples, R. Mitchell, B. Cambourne and N. Macionis (eds) Food Tourism Around the World: Developments, Management and Markets. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 81–101.

Weidenfeld, A. (2006) ‘Religious needs in the hospitality industry’, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 6 (2): 143–159.

Wilson, J., Belk, R.W., Bamossy, G.J., Sandikci, Ö., Kartajaya, H., Sobh, R., et al. (2013) ‘Crescent marketing, Muslim geographies and brand Islam: Reflections from the JIMA Senior Advisory Board’, Journal of Islamic Marketing, 4 (1): 22–50.

Zailani, S., Fernando, Y. and Mohamed, A. (2010) ‘Location, star rating and international chain associated with the hoteliers intention for not applying the Halal logo certification’, European Journal of Social Sciences, 16 (3): 401–408.

Zakaria, Z. (2008) ‘Tapping into the world halal market: Some discussion on Malaysian laws and standards’, Shariah Journal, 16: 603–616.