Chapter 5. Manipulating PDF Files

Introduction: Hacks #51-73

A lot of people think of PDFs as frozen files, printed once and then impossible to modify. That isn’t the case, however! Whether you have Adobe Acrobat or not, there are lots of ways to manipulate PDF files: breaking them up, making their file sizes smaller, encrypting and decrypting them, and presenting them to users in different ways.

Split and Merge PDF Documents (Even Without Acrobat)

You can create new documents from existing PDF files by breaking the PDFs into smaller pieces or combining them with information from other PDFs.

As a document proceeds through its lifecycle, it can undergo many changes. It might be assembled from individual sections and then compiled into a larger report. Individual pages might be copied into a personal reference document. Sections might be replaced as new information becomes available. Some documents are agglomerations of smaller pieces, like an expense report with all of its lovely and easily lost receipts.

While it’s easy to manipulate paper pages by hand, you must use a program to manipulate PDF pages. Adobe Acrobat can do this for you, but it is expensive. Other commercial products, such as pdfmeld from FyTek (http://www.fytek.com), also provide this basic functionality. The pdftk PDF toolkit [Hack #79] is a free software alternative.

Quickly Combine Pages in Acrobat

In Acrobat 6, select File → Create PDF → From Multiple Files . . . . Click the Browse . . . button (Choose . . . on a Macintosh) to open a file selector. You can select multiple files at once. On Windows, you can select a variety of file types, including Microsoft Office documents. Arrange the files into the desired order and click OK.

To quickly combine two PDF documents using Acrobat 5, begin by opening the first PDF in Acrobat. In the Windows File Explorer, select the PDF you want to append, drag it over the PDF open in Acrobat, and then drop it. A dialog will open, asking where you want to insert the PDF. Select After Last Page and it will be appended to the first PDF.

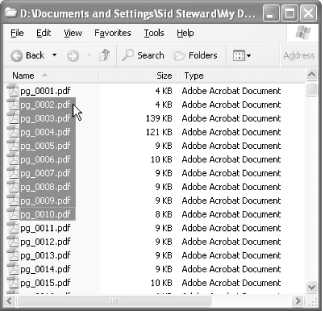

If you have a folder of PDF files to combine and their order in the Windows File Explorer is the order you want in the final document, begin by opening the first PDF in Acrobat 5. Next, in the File Explorer, select the remaining PDFs to merge. Finally, click the first PDF in this selection, as shown in Figure 5-1, drag the selection over the PDF currently open in Acrobat, and then drop it. A dialog will open, asking where you want to insert these PDFs. Select After Last Page and they will be appended to the first PDF. Review the document to ensure the PDFs were appended in the correct order.

Tip

Acrobat also allows you to arrange, move, and copy PDF pages using its Thumbnails view [Hack #14] .

Manipulate Pages with pdftk, the PDF Toolkit

pdftk is a command-line tool for doing everyday things with PDF documents. It can combine PDF documents into a single document or split individual pages out into a new PDF document. Read [Hack #79] to install pdftk and our handy command-line shortcut. pdftk is free software.

Open a command prompt and then change the working directory to the folder that holds the input PDF files. Or, you can open a handy command line by right-clicking the folder that holds your input PDF files and selecting Command from the context menu.

Tip

Instead of typing the input PDF filename, drag-and-drop the PDF file from the Windows File Explorer into the command prompt. Its full filename will appear at the cursor.

To combine pages into one document, invoke pdftk like so:

pdftkcat [] output

A couple of quick examples give you the flavor of it. Here is an example of combining the first page of in2.pdf, the even pages in in1.pdf, and then the odd pages of in1.pdf to create a new PDF named out.pdf:

pdftk A=in1.pdf B=in2.pdf cat B1 A1-endeven A1-endodd output out.pdf

Here is an example of combining a folder of documents to create a new PDF named combined.pdf. The documents will be ordered alphabetically:

pdftk *.pdf cat output combined.pdf

Now, let’s dig into the parameters:

-

<input PDF files> Input PDF filenames are associated with handles like so:

=where a handle is a single, uppercase letter. For example,

A=in1.pdfassociates the handleAwith the file in1.pdf.- Specify multiple input PDF files like so:

A=in1.pdf B=in2.pdf C=in3.pdf

A file handle is necessary only when combining specific pages or when the input file requires a password.

-

[<input PDF pages>] Describe input PDF page ranges like so:

[[-[]]]where the handle identifies one of the input PDF files, and the beginning and ending page numbers are one-based references to pages in that PDF file. The qualifier can be even or odd. A few examples make this clearer. If

A=in1.pdf:-

A1-12 Means the first 12 pages of in1.pdf

-

A1-12even Means pages 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12

-

A12-1even Means pages 12, 10, 8, 6, 4, and 2

-

A1-end Means all the pages from in1.pdf

-

A Means the same thing as

A1-end-

A10 Means page 10 from in1.pdf

-

You can see from these examples that page ranges also specify the

output page order. Notice the keyword

end, which refers to the

final page in a PDF.

Specify a sequence of page ranges like so:

A1 B1-end C5

When combining all the input PDF documents in their given order, you

can omit the <input

PDF

pages> section.

-

<output PDF filename> The output PDF filename must be different from any of the input filenames.

If any of the input files are encrypted, you will need to supply their owner passwords [Hack #52] .

Encrypt and Decrypt PDF (Even Without Acrobat)

Restrict who can view your PDF and how they can use it.

You can use PDF encryption to lock a file’s content behind a password, but more often it is used to enforce lighter restrictions imposed by the author. For example, the author might permit printing pages but prohibit making changes to the document. Here, we continue from [Hack #2] and explain how pdftk [Hack #79] can encrypt and decrypt PDF documents. We’ll begin by describing the Acrobat Standard Security model (called Password Security in Acrobat 6) and the permissions you can grant or revoke.

Tip

PDF file attachments get encrypted, too. After opening an encrypted PDF, document file attachments can be opened, changed, or deleted only if the owner granted ModifyAnnotations permission.

Page file attachments behave differently than document file attachments. Once you open an encrypted document, you can open files attached to PDF pages regardless of the permissions. Changing or deleting one of these attachments requires the ModifyAnnotations permission. Of course, if you have the owner password, you can do anything you want.

PDF Passwords

Acrobat Standard Security enables you to set two passwords on a PDF: the user password and the owner password. In Acrobat 6, these are also called the Open password and the Permissions password, respectively.

The user password, if set, is necessary for viewing the document pages. The PDF encryption key is derived from the user password, so it really is required. When a PDF viewer tries to open a PDF that was secured with a user password, it will prompt the reader to supply the correct password.

The owner password, if set, is necessary for changing the document security settings. A PDF with both its user and owner passwords set can be opened with either password, so you should choose both with equal care.

An owner password by itself does not provide any real PDF security. The content is encrypted, but the key, which is derived from the (empty) user password, is known. By itself, an owner password is a polite but firm request to respect the author’s wishes. A rogue program could strip this security in a second. See [Hack #66] for additional rights management options.

Standard Security Encryption Strength

If your PDF must be compatible with Acrobat 3 or 4, you must use the weaker, 40-bit encryption strength. Otherwise, use the stronger, 128-bit strength. In both cases, the encryption key is created from the user password, so a good, long, random password helps improve your security against brute force attacks. The longest possible PDF password is 32 characters.

Standard Security Permissions

Set the user password if you don’t want people to see your PDF. If they don’t have the user password, it simply won’t open.

You also have some control over what people can do with your document once they have it open. The permissions associated with 128-bit security (Acrobat 5 and 6) are more precise than those associated with 40-bit security (Acrobat 3 and 4). Tables Table 5-1 and Table 5-2 list all available permissions for each security model, and Figure 5-2 shows the permissions as seen through Acrobat. The tables also show the corresponding pdftk flags to use.

|

To allow readers to . . . |

Apply this pdftk permission |

|

Print—pages are top quality |

Printing |

|

Modify page or document contents,insert or remove pages, rotate pages or add bookmarks |

ModifyContents |

|

Copy text and graphics from pages, extract text and graphics data for use by accessibility devices |

CopyContents |

|

Change or add annotations or fill form fields with data |

ModifyAnnotations |

|

Reconfigure or add form fields |

ModifyContents and ModifyAnnotations |

|

All of the above |

AllFeatures |

|

To allow readers to . . . |

Apply this pdftk permission |

|

Print—pages are top quality |

Printing |

|

Print—pages are of lower quality |

DegradedPrinting |

|

Modify page or document contents, insert or remove pages, rotate pages or add bookmarks |

ModifyContents |

|

Insert or remove pages, rotate pages or add bookmarks |

Assembly |

|

Copy text and graphics from pages |

CopyContents |

|

Extract text and graphics data for use by accessibility devices |

ScreenReaders |

|

Change or add annotations or fill form fields with data |

ModifyAnnotations |

|

Fill form fields with data |

FillIn |

|

Reconfigure or add form fields |

ModifyContents and ModifyAnnotations |

|

All of the above, and top-quality printing |

AllFeatures |

Comparing these two tables, you can see that Assembly is a weaker version ofModifyContents and FillIn is a weaker version of ModifyAnnotations.

DegradedPrinting sends pages to the printer as rasterized images, whereas Printing sends pages as PostScript. A PostScript stream can be intercepted and turned back into (unsecured) PDF, so the Printing permission is a security risk. However, DegradedPrinting reduces the clarity of printed pages, so you should test your document to make sure DegradedPrinting yields acceptable, printed pages.

After setting these permissions and/or a user password, changing them requires the owner password, if it is set.

pdftk and Encrypted Input

When using pdftk on encrypted PDF documents, the owner password must be supplied. If an encrypted PDF has no owner password, the user password must be given instead. If an encrypted PDF has neither password set, no password should be associated with this document when calling pdftk.

Input PDF passwords are listed right after the input filenames, like so:

pdftkinput_pw...

The file handles assigned in <input PDF

files> are used to associate files with passwords in

<input file passwords> like so:

=For example:

A=foopass

Adding this parameter to our example in [Hack #51] produces:

pdftk A=in1.pdf B=in2.pdf C=in3.pdf \ input_pw A=foopass cat A1 B1-end C5 output out.pdf

Use pdftk to Encrypt Output

You can encrypt any PDF created with pdftk by simply adding encryption parameters after the output filename, like so:

...output<output filename>\[encrypt_40bit | encrypt_128bit] [allow] \[owner_pw] [user_pw]

Here are the details:

-

[encrypt_40bit | encrypt_128bit] Specify an encryption strength. If this strength is not given along with other encryption parameters, it defaults to

encrypt_128bit.-

[allow <permissions>] List the permissions to grant users. If this section is omitted, no permissions are granted. See Tables Table 5-1 and Table 5-2 for a complete list of available permissions.

-

[owner_pw <owner password>] Use this combination to set the owner password. It can be omitted; in which case no owner password is set.

-

[user_pw <user password>] Use this parameter to set the user password. It can be omitted; in which case no user password is set.

Adding these parameters to our example in [Hack #51] yields this:

pdftk A=in1.pdf B=in2.pdf C=in3.pdf \ cat A1 B1-end C5 output out.pdf \ encrypt_128bit allow CopyContents Printing \ owner_pw ownpass

Simply Encrypting or Decrypting a File

The previous examples were in the context of [Hack #51] . Here are examples of simply adding or removing encryption from a single file:

Add PDF Encryption Actions to Windows Context Menus

Apply or remove encryption from a given PDF with a quick right-click.

[Hack #52] discussed how to apply or remove PDF encryption with pdftk [Hack #79] . Let’s streamline these security operations by adding handy Encrypt and Decrypt items to the PDF context menu. The encryption example simply applies a user password to the selected PDF, so nobody can open it without the password. The decryption example removes all (Standard) security, upon success.

Add the Encrypt PDF Context Menu Item

Windows XP and Windows 2000:

In the Windows File Explorer menu, select Tools → Folder Options . . . and click the File Types tab. Select the PDF file type and click the Advanced button.

Click the New . . . button and a New Action dialog appears. Give the new action the name

Encrypt.Give the action an application to open by clicking the Browse . . . button and selecting cmd.exe, which lives somewhere such as C:\windows\system32\ (Windows XP) or C:\winnt\system32\ (Windows 2000).

Add these arguments after

cmd.exe, changing the path to suit, like so:C:\windows\system32\cmd.exe

/C C:\windows\system32\pdftk.exe "%1" output "%1.encrypted.pdf"encrypt_128bits user_pw PROMPTClick OK, OK, OK and you should be done with the configuration.

Add the Decrypt PDF Context Menu Item

Follow the preceding procedure, except name the action

Decrypt and replace the cmd.exe

arguments in step 4 with:

C:\windows\system32\cmd.exe/C C:\windows\system32\pdftk.exe "%1" input_pw PROMPToutput "%1.decrypted.pdf"

Using Encrypt or Decrypt

Right-click your PDF of interest and select Encrypt or Decrypt from the context menu. A command prompt will open and ask for the password. Upon success, the command prompt will close. pdftk will create a new PDF file with a name based on the original PDF’s filename. If pdftk has trouble executing your request, the command prompt will remain open with a message. Press Enter to close this message.

If you invoke one of these commands on a selection of multiple PDFs, you will get one command prompt for each PDF.

Add Attachments to Your PDF (Even Without Acrobat)

Include live data that your readers can unpack and use.

PDF provides a convenient package for your document. A typical PDF contains fonts, images, page streams, annotations, and metadata. It turns out that you can pack anything into a PDF file, even the source document used to create the PDF! These attachments enjoy the benefits of PDF features such as compression, encryption, and digital signatures. Attachments also enable you to provide your readers with document data, such as tables, in a native file format that they can easily use. People often ask, [Hack #7] . Attach your document data as HTML or Excel files and give your readers exactly what they need.

This hack explains how to attach files to your PDF. [Hack #55] goes on to describe how to quickly extract your document’s tables for PDF attachment.

Page Attachments Versus Document Attachments

You can attach a file to a particular PDF page, where it is visible as an icon. Or, you can attach a file to the PDF document so that it keeps a lower profile. After encrypting your PDF, document attachments can’t be unpacked without the ModifyAnnotations permission [Hack #52] . Page attachments, on the other hand, can be unpacked at any time, regardless of the security permissions you imposed. Of course, the PDF must be opened first, which could require a user password.

Attach Files to a PDF with Acrobat

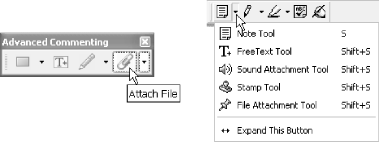

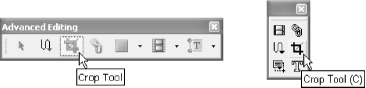

Attach your file to a PDF page using the Attach File commenting tool. In Acrobat 6, access this tool using the Advanced Commenting toolbar or from the Tools → Advanced Commenting → Attach menu. In Acrobat 5, access this tool using the Commenting toolbar. The Attach File tool button hides under the Note tool button; click the little down arrow to discover it, as shown in Figure 5-3.

Activate the Attach File tool and the cursor becomes a push pin. Click the page where you want the attachment’s icon to appear and a file selector dialog opens. Select the file to attach. A properties dialog will open, where you can customize the appearance of your attachment’s icon.

As we noted, document attachments are different from page attachments. In Acrobat 6, access document attachments by selecting Document → File Attachments . . . . Select Document File Attachments and click Import . . . to add an attachment. In Acrobat 5, select File → Document Properties → Embedded Data Objects . . . . Click Import . . . to add an attachment.

Attach Files to PDFs with pdftk

Our free pdftk [Hack #79] can attach files to PDF documents and pages.

When attaching files to an existing PDF, call pdftk like so:

pdftk <PDF filename> attach_file <attachment filename> \ [to_page <page number>] output <output filename>

The output filename must be different from the input filename. For example, attach the file data.xls to the first page of the PDF report.pdf like so:

pdftk report.pdf attach_file data.xls to_page 1 output report.page_attachment.pdf

Attach data.xls to

report.pdf as a document attachment instead of a

page attachment by simply omitting the

to_page parameter:

pdftk report.pdf attach_file data.xls output report.doc_attachment.pdf

You can include additional output parameters, too, such as PDF encryption options.

Attachments and Encryption

When you encrypt a PDF, you also encrypt its attachments. The permissions you apply can affect whether users can unpack these attachments. See [Hack #52] for details on how to apply encryption using pdftk.

Once the PDF is open in Acrobat/Reader (which might require a password), any files attached to PDF pages can be unpacked, regardless of the PDF’s permissions. This enables you to disable copy/paste features, yet still make select data available to your readers.

Document attachments are more restricted than page attachments. You must grant the ModifyAnnotations permission if you want your readers to be able to unpack and view document attachments.

Easily Attach Your Document’s Tables

Pack your document’s essential information into its PDF edition.

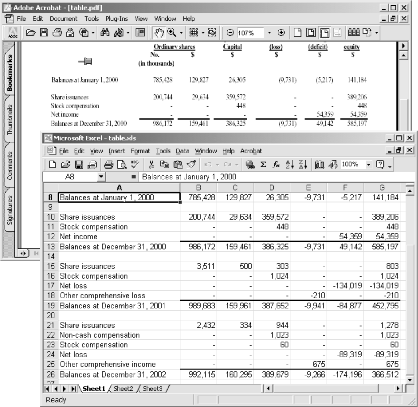

Readers copy data from PDF documents to use in their own documents or spreadsheets. Tables usually contain the most valuable data, yet they are the most difficult to extract from a PDF [Hack #7] . Give readers what they need, as shown in Figure 5-4, by automatically extracting tables from your source document, converting them into an Excel spreadsheet, and then attaching them to your PDF.

Copy Tables into a New Document

In Microsoft Word, use the following macro to copy a document’s tables into a new document. In Word, create the macro like so.

Open the Macros dialog box (Tools → Macro → Macros

. . . ). Type

CopyTablesIntoNewDocument

into the “Macro

name:” field, set “Macros

in:” to Normal.dot, and click

Create.

A window will open where you can enter the macro’s

code. It already will have two lines of code: Sub

CopyTablesIntoNewDocument() and

End

Sub. You

don’t need to duplicate these lines.

You can download the following code from http://www.pdfhacks.com/copytables/:

Sub CopyTablesIntoNewDocument( )

' version 1.0

' http://www.pdfhacks.com/copytables/

Dim SrcDoc, NewDoc As Document

Dim SrcDocTableRange As Range

Set SrcDoc = ActiveDocument

If SrcDoc.Tables.Count <> 0 Then

Set NewDoc = Documents.Add(DocumentType:=wdNewBlankDocument)

Set NewDocRange = NewDoc.Range

Dim PrevPara As Range

Dim NextPara As Range

Dim NextEnd As Long

NextEnd = 0

For Each SrcDocTable In SrcDoc.Tables

Set SrcDocTableRange = SrcDocTable.Range

'output the preceding paragraph?

Set PrevPara = SrcDocTableRange.Previous(wdParagraph, 1)

If PrevPara Is Nothing Or PrevPara.Start < NextEnd Then

Else

Set PPWords = PrevPara.Words

If PPWords.Count > 1 Then 'yes

NewDocRange.Start = NewDocRange.End

NewDocRange.InsertParagraphBefore

NewDocRange.Start = NewDocRange.End

NewDocRange.InsertParagraphBefore

NewDocRange.FormattedText = PrevPara.FormattedText

End If

End If

'output the table

NewDocRange.Start = NewDocRange.End

NewDocRange.FormattedText = SrcDocTableRange.FormattedText

'output the following paragraph?

Set NextPara = SrcDocTableRange.Next(wdParagraph, 1)

If NextPara Is Nothing Then

Else

Set PPWords = NextPara.Words

NextEnd = NextPara.End

If PPWords.Count > 1 Then 'yes

NewDocRange.Start = NewDocRange.End

NewDocRange.InsertParagraphBefore

NewDocRange.FormattedText = NextPara.FormattedText

End If

End If

Next SrcDocTable

End If

End SubRun this macro from Word by selecting Tools → Macro → Macro . . . , selecting Copy Tables Into New Document, and clicking Run. A new document will open that contains all the tables from your current document. It will also include the paragraphs immediately before and after each table. This feature was added to help readers find the table they want. Modify the macro code to suit your requirements.

Create an HTML or Excel Document from Your Tables Document

Use [Hack #35] to convert this new document into HTML. Make this HTML file act like an Excel spreadsheet by changing its filename extension from html to xls. Excel is perfectly comfortable opening data this way.

Attach the Tables to Your PDF

See [Hack #54] for the detailed procedure. Speed up attachments with quick attachment actions [Hack #56] .

Add PDF Attachment Actions to Windows Context Menus

Pack or unpack PDF attachments from the Windows File Explorer with a quick right-click.

It’s best to perform simple tasks in a simple manner, especially when you must perform them often. Wire pdftk [Hack #79] into Windows Explorer so that you can pack or unpack attachments using PDF’s right-click context menu.

Create the Attach File Context Menu Item

In Windows XP and Windows 2000:

In the Windows File Explorer menu, open Tools → Folder Options . . . and click the File Types tab. Select the PDF file type and click the Advanced button.

Click the New . . . button and a New Action dialog appears. Give the new action the name

Attach File.Give the action an application to open by clicking the Browse . . . button and selecting cmd.exe, which lives somewhere such as C:\windows\system32\ (Windows XP) or C:\winnt\system32\ (Windows 2000).

Add these arguments after

cmd.exe, changing the path to suit, like so:C:\windows\system32\cmd.exe

/C C:\windows\system32\pdftk.exe "%1" attach_file PROMPT output PROMPTClick OK, OK, OK and you should be done with the configuration.

Create the Unpack Attachments Context Menu Item

Follow the previous procedure, except name the action Unpack

Attachments and replace the cmd.exe

arguments in step 4 with:

/C C:\windows\system32\pdftk.exe "%1" unpack_files

Using Attach File or Unpack Attachments

Right-click your PDF of interest and select Attach File or Unpack Attachments from the context menu. A command prompt will open and ask for additional information. Upon success, the command prompt will close. If pdftk has trouble executing your request, the command prompt will remain open with a message. Press Enter to close this message.

Tip

Use drag-and-drop to quickly enter the filenames for the files you want to attach. Select a file in Explorer, drag it over to the command-line window, and drop it. Its full filename will appear at the cursor. This works for only one file at a time.

If you invoke one of these commands on a selection of multiple PDFs, you will get one command prompt for each PDF.

Create a Traditional Index Section from Keywords

Add a search feature to your print edition.

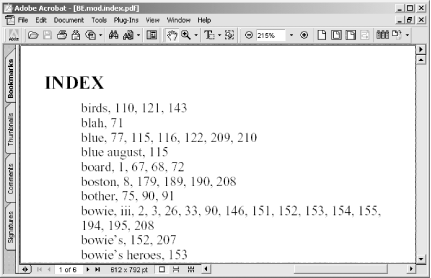

Creating a good document Index section is a difficult job performed by professionals. However, an automatically generated index still can be very helpful. Use automatic keywords [Hack #19] or select your own keywords. This hack will locate their pages, build a reference, and then create PDF pages that you can append to your document, as shown in Figure 5-5. It even uses your PDF’s page labels (also known as logical page numbering) to ensure trouble-free lookup.

Tool Up

Download and install pdftotext [Hack #19] , our kw_index [Hack #19] , and pdftk [Hack #79] . You must also have enscript (Windows users visit http://gnuwin32.sf.net/packages/enscript.htm ) and ps2pdf. ps2pdf comes with Ghostscript [Hack #39] . Our kw_index package includes the kw_catcher and page_refs programs (and source code) that we use in the following sections.

The Procedure

First, set your PDF’s logical page numbering [Hack #62] to match your document’s page numbering. Then, use pdftk to dump this information into a text file, like so:

pdftkdump_data output

Next, convert your PDF to plain text with pdftotext:

pdftotext Create a keyword list [Hack #19] from mydoc.txt using kw_catcher, like so:

kw_catcherkeywords_only>

Edit mydoc.kw.txt to remove duds and add missing keywords. At present, only one keyword is allowed per line. If two or more keywords are adjacent in mydoc.txt, our page_refs program will assemble them into phrases.

Now pull all these together to create a text index using page_refs:

page_refs>

Finally, create a PDF from mydoc.index.txt using enscript and ps2pdf:

enscript --columns 2 --font 'Times-Roman@10' \--header '|INDEX' --header-font 'Times-Bold@14' \--margins 54:54:36:54 --word-wrap --output -\| ps2pdf -

The Code

Of course, the thing to do is to wrap this procedure into a tidy

script. Copy the following Bourne shell script into a file named

make_index.sh, and make it executable by

applying chmod 700. Windows

users can

get a Bourne shell by installing MSYS

[Hack #97]

.

#!/bin/sh

# make_index.sh, version 1.0

# usage: make_index.sh <PDF filename> <page window>

# requires: pdftk, kw_catcher, page_refs,

# pdftotext, enscript, ps2pdf

#

# by Ross Presser, Imtek.com

# adapted by Sid Steward

# http://www.pdfhacks.com/kw_index/

fname=`basename $1 .pdf`

pdftk ${fname}.pdf dump_data output ${fname}.data.txt && \

pdftotext ${fname}.pdf ${fname}.txt && \

kw_catcher $2 keywords_only ${fname}.txt \

| page_refs ${fname}.txt - ${fname}.data.txt \

| enscript --columns 2 --font 'Times-Roman@10' \

--header '|INDEX' --header-font 'Times-Bold@14' \

--margins 54:54:36:54 --word-wrap --output - \

| ps2pdf - ${fname}.index.pdfRunning the Hack

Pass the name of your PDF document and the kw_catcher window size to make_index.sh like so:

make_index.shThe script will create a document index named mydoc.index.pdf. Review this index and append it to your PDF document [Hack #51] if you desire. The script also creates two intermediate files: mydoc.data.txt and mydoc.txt. If the PDF index is faulty, review these intermediate files for problems. Delete them when you are satisfied with the PDF index.

The second argument to make_index.sh controls the keyword detection sensitivity. Smaller numbers yield fewer keywords at the risk of omitting some keywords; larger numbers admit more keywords and also more noise. [Hack #19] discusses this parameter and the kw_catcher program that uses it.

Rasterize Intricate Artwork with Illustrator or Photoshop

When distributing a PDF online, some vector drawings outweigh their usefulness.

Vector drawings yield the highest possible quality across all media. For simple illustrations such as charts and graphs, they are also more efficient than bitmaps. However, when preparing a PDF for online distribution, you will sometimes find an intricate vector drawing that has tripled your PDF’s file size. With Acrobat and Illustrator (or Photoshop), you can rasterize this detailed drawing in-place and reduce your PDF’s file size.

Big Drawings in Little Spaces

How does this happen? Vector artwork scales easily without altering its quality. This means a big, detailed, 2 MB vector drawing can be scaled down perfectly to the size of a postage stamp. Even though most of its detail might no longer be visible on a paper printout or on-screen, the drawing is still 2MB in size. Again, this becomes an issue only when you go to distribute this file online and you want to reduce the document’s file size.

Integrate Illustrator or Photoshop into Acrobat

If you have Adobe Acrobat 6 Pro or Acrobat 5 and Adobe Illustrator or Adobe Photoshop, you can rasterize a PDF’s drawings. First you must configure Acrobat’s TouchUp Object tool to open your PDF selections in Illustrator or Photoshop.

In Acrobat, select Edit → Preferences → General . . . → TouchUp. Click Choose Page/Object Editor and then browse over to Illustrator.exe, which might be located somewhere such as C:\Program Files\Adobe\Illustrator 9.0.1\. Or, use Photoshop instead of Illustrator by browsing over to Photoshp.exe, which might be located somewhere such as C:\Program Files\Adobe\Photoshop 6.0\. Click Open and then click OK to confirm your new Preferences setting.

Rasterize Drawings In-Place with Acrobat

First, make a backup copy of your PDF so that you can go back to where you started at any time.

Open your PDF in Acrobat and locate the drawing you want to rasterize. Activate the TouchUp Object tool (Tools → Advanced Editing → TouchUp Object, in Acrobat 6) and try to select the drawing. This usually requires patience and experimentation because one illustration might use dozens of separate drawing objects. And, it usually is tangled with other items on the page that you don’t want to rasterize.

First, try dragging out a selection rectangle that encloses the artwork. If other, unwanted items get caught in your dragnet, try dropping them from your selection by holding down the Shift key and clicking them. If you missed items that you wanted to select, you can add them the same way: Shift-click. The Shift key is a useful way to incrementally add or remove items from your current selection. You can even hold down the Shift key while dragging out a selection rectangle. Items in the rectangle will be toggled in or out of the current selection, depending on their previous state.

If you accidentally move an item, immediately press Ctrl-Z (Edit → Undo) to restore it. If things ever get messed up, close the PDF without saving it and reopen it to start again.

Using Illustrator

After your selection is made in Acrobat, right-click inside the selection and click Edit Objects . . . . Adobe Illustrator will open and your selected material will appear. Now, you must select the items you want to rasterize. If your selection in Acrobat worked just right, you can simply select the entire page (Edit → Select All). If your original selection included unwanted items, carefully omit these items from this new selection. The Shift key works the same way in Illustrator as it did in Acrobat, as you assemble your selection.

After making your selection in Illustrator, select Object → Rasterize . . . and a dialog opens. Select a suitable color model (e.g., RGB) and resolution (e.g., 300 pixels per inch) and click OK. Inspect the results to make sure the artwork retained adequate detail. If you like the results, save and close the Illustrator file. Acrobat will automatically update the PDF to reflect your changes. If you still like them, save the PDF in Acrobat. Otherwise, discard them by pressing Ctrl-Z (Edit → Undo) or by closing the PDF and starting over.

Using Photoshop

If you are using Photoshop instead of Illustrator, you won’t have a chance to select the objects you want rasterized; Photoshop immediately rasterizes everything you selected in Acrobat. One advantage of using Photoshop is that it won’t try to substitute fonts, as Illustrator sometimes does.

After your selection is made in Acrobat, right-click inside the selection and click Edit Objects . . . . Photoshop will open and ask you for a resolution. Enter a resolution (e.g., 300 pixels per inch), click OK, and the rasterized results will appear. Inspect the results to make sure the artwork retained adequate detail. If you like the results, save the Photoshop file. By default, it should save as PDF, but sometimes you must change the Format to PDF in the Save dialog. Before saving the file, Photoshop will ask which encoding to use (ZIP or JPEG). If you choose JPEG, you can also set its quality level. After saving the rasterized artwork in Photoshop, Acrobat will automatically update the PDF to reflect your changes. If you still like them, save the PDF in Acrobat. Otherwise, discard them by pressing Ctrl-Z (Edit → Undo) or by closing the PDF in Acrobat and starting over.

Reordering Page Layers in Acrobat

Sometimes, when the rasterized artwork is brought back into the PDF, it will cover up and obscure other items on the page. The trick is to place the new bitmap behind the obscured items.

In Acrobat 5, select the bitmap with the TouchUp Object tool, right-click, and select Cut. Right-click the page anywhere and select Paste In Back. The bitmap should appear in the same location, but behind the other items on the page. If it didn’t reappear, it is probably being obscured by a larger, background item. Select this obscuring object and cut-and-paste it the same way. Save the PDF when you are done.

In Acrobat 6, open the Content tab (View → Navigation Tabs → Content) and click on the plus symbol to open a hierarchy of document page references. Locate your page and then click on its plus symbol to open a hierarchy of page objects. Lower objects on this stack overlap the higher objects. Identify your image (it will be wrapped inside an XObject node), then click and drag it to a higher level in the page hierarchy. This will take some experimentation. See [Hack #63] for tips on dragging and dropping these nodes. Save the PDF when you are done.

Crop Pages for Clarity

Aggressive page cropping ensures maximum on-screen clarity.

When viewing a PDF in Reader or Acrobat, the page is often scaled to fit its width or its height into the viewer window. This means you can make page content appear larger on-screen by cropping away excess page margins, as shown in Figure 5-6. Cropping has no effect on the printed page’s scale, but it might alter the content’s position on the printed page.

Acrobat’s cropping tool can remove excess page margins. Use it in combination with our freely available BBOX Acrobat plug-in. These two tools make it easy to find the best cropping for a page and then apply this cropping to the entire document.

Acrobat’s Crop Tool

With Acrobat’s Crop tool, shown in Figure 5-7, you can draw a free-form crop region by clicking the page and dragging out a rectangle. Double-click this new region or simply double-click the page and the Crop Pages dialog opens. The Crop Pages dialog enables you to directly enter the widths you want to trim from each margin. You can also specify a range of document pages to crop according to these settings. The Remove White Margins setting sounds like just what we need, but it is inconsistent and it yields pages with irregular dimensions.

Using the Crop tool to draw a free-form region gives you an irregular page size that probably doesn’t precisely center your content. The solution is to activate the Snap to Grid feature (View → Snap to Grid). By default, this grid is set to three subdivisions per inch. A more useful setting might be four or eight subdivisions per inch.

BBOX Acrobat Cropping Plug-In for Windows

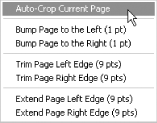

BBOX is a simple tool I use in my PDF production. Download it from http://www.pdfhacks.com/bbox/, unzip, and copy pdfhacks_bbox.api into your Acrobat plug_ins folder [Hack #4] . When you restart Acrobat, it will add a menu named Plug-Ins → PDF Hacks → BBOX (the contents of which are shown in Figure 5-8).

The BBOX Auto-Crop feature crops as much as it can from the currently visible page. It trims away multiples of 1/8 inch (9 points), so the resulting page size isn’t irregular. It tries to be smart, but it sometimes leaves margins that need additional cropping.

The Trim Page features enable you to trim 1/8 inch from the left or right page edges. If you go too far, use the Extend Page features to add 1/8 inch instead.

Sometimes 1/8-inch units are not fine enough to center a page. For these cases, we have the Bump Page features. These do not alter the page width, but appear to move the page one point at a time. They simply reduce the crop on one side and increase the crop on the other, giving you fine control over page centering.

Document Cropping Procedure

Does your document jog back and forth from one page to the next? Then you have page gutters. You will need to crop your even pages separately from your odd pages.

Find a representative page and crop it to your satisfaction using any combination of the Crop and BBOX tools. If your document has gutters, turn to the next page and give it the same treatment. Flip back and forth between these two pages as you work to remove the gutter, trying to get the pages to stop jogging back and forth.

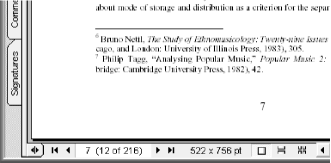

When your representative page is cropped to your satisfaction, open the Crop Pages dialog by selecting the Crop tool and double-clicking the page. Set the page range to All Pages. If you are cropping even and odd pages separately, set the nearby drop-down box to Even Pages Only or Odd Pages Only depending on which page you currently have displayed. Click OK. Even and odd in this context refer to the physical page numbers (or page indexes) in your document, shown in Figure 5-9, not the logical page numbers (or page labels).

Refry Before Posting Documents Online

Run your assembled PDF through Acrobat Distiller to reduce its file size. In Acrobat 6, try PDF Optimizer.

You started with two or three PDFs, combined them, and then cropped them. Before going any further, consider running your assembled PDF through Distiller. This refrying can reduce duplicate resources and ensures that your PDF is optimized for online reading. It also gives you a chance to improve your PDF’s compatibility with older versions of Acrobat and Reader. In Acrobat 6, you can conveniently refry a PDF without Distiller by using the PDF Optimizer feature. Even so, distilling a PDF can yield better results than the PDF Optimizer can.

Traditional Refrying with Distiller

Refrying traditionally has been done with a simple hack, reprinting the PDF out to Distiller, which creates a new PDF file:

Save your PDF in Acrobat using the File → Save As . . . function. Acrobat will consolidate its resources as much as it can. Acrobat 6 does this more aggressively than Acrobat 5 does.

Open the Acrobat Print dialog (File → Print . . . ) and select the Adobe PDF printer (Acrobat 6) or the Distiller printer (Acrobat 5).

Set the Distiller profile by selecting Properties → Adobe PDF Settings and adjusting the Default Settings (Acrobat 6) or Conversion Settings (Acrobat 5) drop-down box. For online distribution, consider these profiles: eBook, Standard, Screen, or Smallest File Size.

If you cropped your PDF, you should set the Print page size to match your PDF page size. In the Acrobat 6 Print dialog, adjust Properties → Adobe PDF Settings → Adobe PDF Page Size to fit your page. Use the Add Custom Page . . . button if you can’t find your page size among the current options. In the Acrobat 5 Print dialog, adjust Properties → Layout tab → Advanced . . . → Paper Size to fit your page. Select PostScript Custom Page Size if you can’t find your page size among the current options.

Print to Distiller. Do not overwrite your original PDF.

Review the resulting PDF. Is its file size smaller? Is its fidelity acceptable?

Reapply page cropping as needed. You might need to rotate some pages.

To restore bookmarks and other features, see [Hack #61] .

Refrying with PDF Optimizer in Acrobat 6 Professional

PDF Optimizer (Advanced → PDF Optimizer . . . ) performs this service much more conveniently. Its settings resemble Distiller’s, and they enable you to downsample images, remove embedded fonts, or remove unwanted PDF features. You can also change the PDF compatibility to Acrobat 5. Click OK and it will create a new PDF for you. Compare this new PDF with the original and decide whether to keep it or try again. The best time to use the PDF Optimizer is just before you put the PDF online.

The Best Time to Refry Using Distiller

The best time to refry a PDF using Distiller (as opposed to the PDF Optimizer) is after you have assembled it, but before you have added any PDF features. Here is the sequence I typically use when preparing a PDF for online distribution:

Assemble the original PDF pages and Save As . . . to a new PDF.

If page sizes are wildly irregular, crop them [Hack #59] .

Refry the original PDF document and compare the resulting refried PDF to the original. Adjust Distiller settings [Hack #42] as necessary and choose the best results.

Crop and rotate the refried PDF pages as needed.

If the original document had bookmarks or other PDF features, copy them back to the refried PDF [Hack #61] .

Add PDF features [Hack #63] or finishing touches [Hack #62] .

Save again using Save As . . . to compact the PDF. In Acrobat 6, save the final PDF by selecting File → Reduce File Size . . . and set the compatibility to Acrobat 5.

Copy Features from One PDF to Another

Restore bookmarks, annotations, and forms after refrying your PDF.

You just refried your high-fidelity PDF [Hack #60] to create a lightweight, online edition and Distiller burned off the nifty PDF navigation features and forms. Let’s combine the old PDF’s navigation features and forms with the new PDF’s pages to get a lightweight, interactive PDF. Here’s how:

Open the old PDF file (the one with the bookmarks, links, or form fields) in Acrobat.

In Acrobat 6, select Document → Pages → Replace. In Acrobat 5, select Document → Replace Pages from the menu.

A file selector dialog opens. Select the new PDF file (the one with no PDF features).

The Replace Pages dialog opens, requesting which pages to replace. Enter the first and last page numbers of your document.

When it is done, select Save As . . . to save the resulting PDF into a new file.

Test the resulting PDF to make sure all your interactive features came through successfully.

Using the Replace Pages feature like this to separate the visible page from its interactive features can be pretty handy. If you ever need to transfer a page and its interactive features, use the Extract Pages, Insert Pages, and Delete Pages functions.

Polish Your PDF Edition

Little things can make a big difference to your readers.

Most creators don’t use these basic PDF features, yet they improve the reading experience and they are easy to add. Read [Hack #67] to learn about the additional features required for serving individual PDF pages on demand.

Document Initial View

If your PDF has bookmarks, set your PDF to display them when the document is opened. Otherwise, your readers might never discover them. You can change this, and other settings, from the PDF’s document properties. In Acrobat 6, select File → Document Properties . . . → Initial View to access these setting. In Acrobat 5, select File → Document Properties → Open Options.

Logical Page Numbering

Open your PDF in Acrobat and go to page 1. If your PDF doesn’t have logical page numbering, Acrobat thinks its first page is “page 1.” Yet your document’s “page 1” might actually fall on Acrobat’s page 6, as shown in Figure 5-10. Imagine your readers trying to make sense of this, especially when your document refers them to page 52 or when they decide to print pages 42-47.

Synchronize your document’s page numbering with Acrobat/Reader by adding logical page numbers to your PDF. In Acrobat 6, select the Pages navigation tab (View → Navigation Tabs → Pages), click Options, and select Number Pages . . . from the drop-down menu. In Acrobat 5, access the Page Numbering dialog box by selecting Document → Number Pages . . . .

Start from the beginning of your document and work to the end, to minimize confusion. If numbering gets tangled up, reset the page numbers by selecting All Pages, Begin New Section, Style: 1, 2, 3, . . . , Prefix: (blank), Start: 1, and clicking OK.

If your document has a front cover, you can give it the logical page

number Cover by setting its Style to None and

giving it a Prefix of Cover.

Does your document have front matter with Roman-numeral page numbers? Advance through your document until you reach page 1. Go back to the page before page 1. Open the Page Numbering dialog. Set the page range From: field to 1. Set the Style to “i, ii, iii, . . . ,” and make sure Prefix is empty. Click OK. Now, the pages preceding page 1 should be numbered “i, ii, . . . ,” and page 1 should be numbered 1.

Go to the final page in your PDF and make sure the numbering still matches. Sometimes people remove blank pages from a PDF, which causes the document page numbers to skip. If you plan to remove blank pages from your PDF, apply logical page numbering beforehand.

Document Title, Author, Subject, and Keywords

Document metadata doesn’t jump out at readers the way bookmarks and logical page numbers do, but your readers can use it to help organize their collections [Hack #22] . Plus, it looks pretty sharp to have them properly filled in. The title and author fields are often filled automatically with nonsense, such as the document’s original filename (e.g., Mockup.doc) or the typesetter’s username.

Tip

You can disable the automatic metadata added by Distiller. Open Distiller and edit your profile’s settings. Uncheck Advanced → Preserve Document Information from DSC, and click OK.

In Acrobat 6, view and update this information by selecting File → Document Properties . . . → Description or Advanced → Document Metadata . . . . In Acrobat 5, select File → Document Properties → Summary. See [Hack #64] for a broader discussion of PDF metadata.

Page Orientation and Cropping

Quickly page through your document from beginning to end, making sure that your page cropping [Hack #59] didn’t chop off any data. Also check for rotated pages. Adjust rotated pages to a natural reading orientation by selecting Document → Pages → Rotate (Acrobat 6) or Document → Rotate Pages (Acrobat 5).

Rotating and cropping PDF pages can affect how they print. The user should select “Auto-rotate and center pages” from the Print dialog box when printing PDF to minimize surprises.

Add and Maintain PDF Bookmarks

Bookmarks greatly improve document navigation. Adding them is pretty easy.

Ideally, your document’s headings would have been turned into PDF bookmarks when it was created [Hack #32] . If you ended up with no bookmarks or the wrong bookmarks, you can add or change them using Acrobat. Here are a few tricks to speed things up.

Add Bookmarks

Create a bookmark to the current view using the Ctrl-B shortcut (Command-B on the Macintosh). Then, type a label into the new bookmark and press Enter. Note that current view means the current page, current viewing mode (e.g., Actual Size, Fit Width, or Fit Page), or current zoom. For example, if you want a bookmark to fill the page with a specific table, zoom in to that table before creating the bookmark. When quickly creating bookmarks to a document’s headings, I simply use the Fit Page viewing mode.

Every bookmark needs a text label, and this label usually corresponds to a document heading. Instead of typing in the label, use the Text Select tool to select the heading text on the PDF page. When you create the bookmark (Ctrl-B or Command-B), the selected text appears in the label. Review this text for errors.

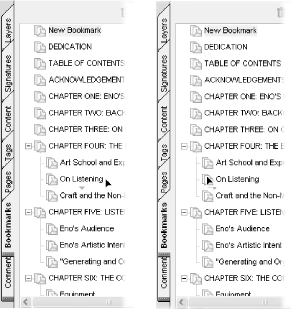

Move Bookmarks

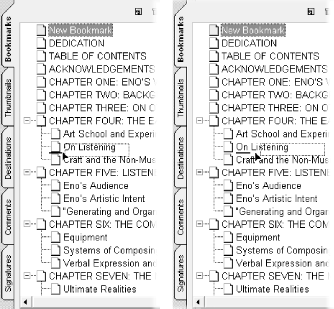

New bookmarks don’t always appear where you want them. Select a bookmark (use a right-click to keep from activating it), click, and drag it to where it belongs. A little cursor will appear, indicating where the bookmark would go if you dropped it. You can indent a bookmark by dragging it to the left (Acrobat 6, shown in Figure 5-11) or the right (Acrobat 5, shown in Figure 5-12) of the intended parent. The little cursor will jump, showing you where the bookmark would go.

Move an entire block of bookmarks by first creating a multiple selection. In Acrobat 6, the order in which you select bookmarks is the order they will have after you move them, which can be a surprise. To preserve their order, add bookmarks to your multiple selection from top to bottom.

Select the first bookmark, hold down the Shift key, and then select the final bookmark in the block. Hold down the Ctrl key and click a bookmark to add or remove it from your selection. Click the selection and drag it to its new location.

Get and Set PDF Metadata

Add document information to your PDF, even without using Acrobat.

Traditional metadata includes things such as your document’s title, authors, and ISBN. But you can add anything you want, such as the document’s revision number, category, internal ID, or expiration date. PDF can store this information in two different ways: using the PDF’s Info dictionary [Hack #80] or using an embedded Extensible Metadata Platform (XMP) stream. When you change the PDF’s title, authors, subject, or keywords using Acrobat, as shown in Figure 5-13, it updates both of these resources. Acrobat 6 also enables you to export or import PDF XMP datafiles. Visit http://www.adobe.com/products/xmp/ to learn about Adobe’s XMP.

In Acrobat 6, view and update metadata by selecting File → Document Properties . . . → Description or Advanced → Document Metadata . . . . In Acrobat 5, select File → Document Properties → Summary. Save your PDF after making changes to the metadata.

Our pdftk [Hack #79] currently reads and writes only the metadata in a PDF’s Info dictionary. However, it does not restrict you to just the title, authors, subject, and keywords. This solves the basic problem of embedding information into a PDF document; pdftk allows you to add custom metadata fields to PDF as needed. pdftk is free software.

Xpdf’s (http://www.foolabs.com/xpdf/) pdfinfo reports a PDF’s Info dictionary contents, its XMP stream, and other document data. pdfinfo is free software.

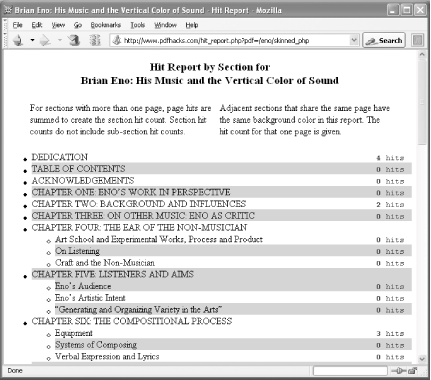

Get Document Metadata

To create a plain-text report of PDF

metadata,

use pdftk’s

dump_data operation. It will also report PDF

bookmarks and page labels, among other things. The command looks like

this:

pdftkdump_data output

Metadata will be represented as key/value pairs, like so:

InfoKey: Creator InfoValue: Acrobat PDFMaker 6.0 for Word InfoKey: Title InfoValue: Brian Eno: His Music and the Vertical Color of Sound InfoKey: Author InfoValue: Eric Tamm InfoKey: Producer InfoValue: Acrobat Distiller 6.0.1 (Windows) InfoKey: ModDate InfoValue: D:20040420234132-07'00' InfoKey: CreationDate InfoValue: D:20040420234045-07'00'

Another tool for reporting PDF metadata is

pdfinfo, which is

part of the Xpdf project (http://www.foolabs.com/xpdf/). In addition to

metadata, it also reports page sizes, page

count, and PDF permissions

[Hack #52]

.

Running pdfinfo

mydoc.pdf

yields a report such as this:

Title: Brian Eno: His Music and the Vertical Color of Sound Author: Eric Tamm Creator: Acrobat PDFMaker 6.0 for Word Producer: Acrobat Distiller 6.0.1 (Windows) CreationDate: 04/20/04 23:40:45 ModDate: 04/22/04 14:39:30 Tagged: no Pages: 216 Encrypted: no Page size: 522 x 756 pts File size: 1126904 bytes Optimized: yes PDF version: 1.4

Use pdfinfo’s options to fine-tune its behavior. Use

its -meta option to view a PDF’s

XMP stream.

Set Document Metadata

pdftk can take a plain-text file of these same key/value pairs and update a PDF’s Info dictionary to match. Currently, it does not update the PDF’s XMP stream. The command would look like this:

pdftkupdate_infooutput

This will add or modify the Info keys given by mydoc.new_data.txt. Note that the output PDF filename must be different from the input. To remove a key/value pair, simply pass in the key/value with an empty value, like so:

InfoKey: MyDataKey InfoValue:

Tip

Use pdftk to strip all Info and XMP metadata from a document by copying its pages into a new PDF, like so:

pdftk mydoc.pdf cat A output mydoc.no_metadata.pdf

The PDF specification defines several Info fields. Be careful to use

these only as described in the specification. They are

Title, Author,

Subject, Keywords,

Creator, Producer,

CreationDate, ModDate, and

Trapped.

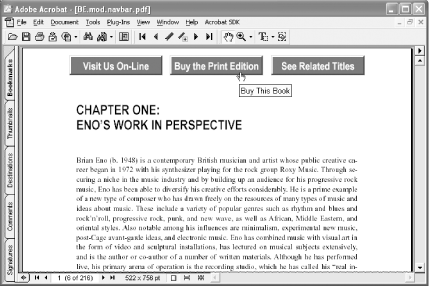

Add a Web-Style Navigation Bar to PDF Pages

Ensure that readers see your essential links.

Styles used on the Web suggest that readers love navigation bars, such as the one shown in Figure 5-14.

Creating a PDF navigation bar in Acrobat and then duplicating it across several (or all) document pages is easy. Links can open external web pages or internal PDF pages. Add graphics and other styling elements to make it stand out. Disable printing to prevent it from cluttering printed pages. All of this is possible with PDF form buttons.

Create Buttons and Set Actions

Create and manage buttons using the appropriate Acrobat tool. In Acrobat 6, activate the Button Tool (Tools → Advanced Editing → Forms → Button Tool), then click and drag out a rectangle. Release the mouse and the Button Properties dialog opens. Select the Actions tab and click the Select Action drop-down box. Choose Go to a Page in this Document or Open a Web Link and click Add . . . . Another dialog opens where you can enter destination details. Click OK and the action should be added to the button’s Mouse Up event. Click Close and your button should be functional. Test it by selecting the Hand Tool and clicking the button.

Tip

Improve your button’s precision by activating Snap to Grid from View → Snap to Grid. Alter its subdivisions from the Units and Guides (Acrobat 6) or Layout Grid (Acrobat 5) preferences.

In Acrobat 5, select the Form Tool, then click and drag out a rectangle. Release the mouse and a Field Properties dialog opens. Enter the button’s name (it can be anything, but it must be unique) and change the Type: to Button. Click the Actions tab, select Mouse Up, and click Add . . . . Curiously, you do not have the choice to go to a page within the document. Instead, select JavaScript and enter this simple code; JavaScript page numbers are zero-based, so this example goes to page 6, not page 5:

this.pageNum = 5;Or, select World Wide Web Link if you want the button to open a web page. Click Set Action and then OK, and your button should be functional. Test it by selecting the Hand Tool and clicking the button.

Styling Buttons and Adding Graphics

By default, buttons are plain, gray rectangles. Change a button’s background and border using the Appearance tab in its properties dialog; you can even make a button transparent. Change a button’s text label using the Options tab.

The Options tab also enables you to select a graphical icon. Change the Layout: to include an Icon and then click Choose Icon. You can use a bitmap, a PostScript drawing (Acrobat 6), or even a PDF page as a button icon.

Consider creating a no-op graphical button as a background to your other (transparent) buttons. This can be easier than trying to split a single navigation bar graphic into several pieces. Just make sure the active buttons end up on top of the graphic layer; otherwise, they won’t work. Do this by creating the graphic layer before creating any of the active buttons, or by giving the graphic layer a lower position in the tabbing order.

Tip

Alter form field tab order in Acrobat 6.0.1 by activating the Select Object Tool (Tools → Advanced Editing → Select Object Tool), selecting Advanced → Forms → Fields → Set Tab Order, and then clicking each field in order. Alter form field tab order in Acrobat 5 by activating the Form Tool, selecting Tools → Forms → Fields → Set Tab Order, and then clicking each field in order.

To prevent a button from printing, open its properties and select the General tab (Acrobat 6) or the Appearance tab (Acrobat 5). Change Form Field: to Visible but Doesn’t Print.

Copying Buttons Across All Pages

Activate the Button Tool (Acrobat 6) or the Form Tool (Acrobat 5), hold down the Shift key, and select each button until all of them are selected. Right-click the selection and choose Duplicate . . . . Enter the desired page range and click OK. Your navigation bar now should exist on those pages, too. Page through your document to ensure they are positioned properly.

Copy-Protect Your PDF

Control how far your document can wander by making it difficult to copy.

A large document represents a great deal of work, and PDF is a good way to distribute large documents. Sometimes, it is too good. Perhaps your readers are paying customers, and you don’t want them to make copies for their friends. Perhaps you want people to read your work only from your web site, not from a downloaded copy. These kinds of controls go beyond standard PDF security [Hack #52] . This hack discusses some solutions.

Low Tech: Print Editions

Copying and sharing print editions of your document would be too much trouble for most readers. Your price for this security is the cost and trouble of production and shipping. However, readers might prefer a print edition, such as the one shown in Figure 5-15, in which case you are also adding value to your work. [Hack #29] discusses how to create print-on-demand (POD) books. Print editions are vulnerable to being converted to unsecured PDF by scanning and OCR.

Online Reading Only

Another idea is to prevent the reader from ever downloading your PDF. A single PDF can always be downloaded. So, burst your document into individual PDF pages and then wrap them in our HTML skins [Hack #71] . When you burst the PDF, supply additional security settings [Hack #52] for the output pages so that the reader won’t be able to easily reassemble them. For example:

pdftk doc.pdf burst encrypt_128bits owner_pw 23@#5dfa allow DegradedPrinting

After integrating your document into your web site, you can employ user accounts, passwords, and other common security devices for enforcing access permissions.

Skinned PDFs are vulnerable to being copied from your site using a recursive HTTP robot. The result would be an exact copy of your site’s pages (PDF and HTML) on the user’s local machine.

Chain the PDF to the User’s Machine

Digital Rights Management (DRM) tools give you fine-grained control over how and when the reader can use your document. Typically, a reader downloads the full PDF, but he can’t read it until he purchases a key. After he makes the purchase, a key is created that can open that PDF only on that computer. Some readers find this model too restricting.

DRM software vendors include Adobe (PDF Merchant), FileOpen Systems, Authentica, and SoftSeal. Their tools tend to be too expensive for the casual user. Consider partnering with a distributor or a self-publishing service [Hack #29] .

Support Online PDF Reading

Serve PDF pages on demand and spare readers a long download.

Sometimes readers want to download the entire document; sometimes they want to read just a few pages. If a reader desires to read a single page from your PDF, she shouldn’t be stuck downloading the entire document. A large document download will turn her away. The easiest solution is to configure your PDF and your web server for serving individual pages on request. An alternative is to use our PDF skins [Hack #71] .

Prepare the PDF

To permit page-at-a-time delivery over the Web, a PDF must be linearized . Linearization organizes a PDF’s internal structure so that a client can request the PDF resources it needs on a byte-by-byte basis. If the reader wants to see page 12, then the client requests only the data it needs to display page 12.

Test whether a PDF is linearized by opening it in Acrobat/Reader and viewing its document properties. Open File → Document Properties . . . → Description (Acrobat 6) or File → Document Properties → Summary (Acrobat 5). A linearized PDF shows Fast Web View: Yes.

The Xpdf project (http://www.foolabs.com/xpdf/) includes a command-line tool called pdfinfo that can tell you if a PDF is linearized. Pass your PDF to pdfinfo like so:

pdfinfo pdfinfo will create a text report on-screen that says Optimized: Yes if your PDF is linearized. pdfinfo is free software.

To create a linearized PDF using Acrobat, first inspect your preferences. Select Edit → Preferences → General . . . and choose the General category (Acrobat 6) or the Options category (Acrobat 5). Place a checkmark next to Save As Optimizes for Fast Web View and click OK.

Open the PDF you want to linearize and then Save As... to the same filename. In Acrobat 6, you can change the PDF’s compatibility level at the same time by selecting File → Reduce File Size instead of Save As.... Open the document properties to check that it worked.

If you ever make changes to the PDF in Acrobat and then simply File → Save your PDF, it will no longer be linearized. You must use Save As... to ensure that your PDF remains linearized.

Ghostscript [Hack #39] includes a command-line tool called pdfopt that can linearize PDF. To create a linearized PDF using pdfopt, invoke it from the command-line like so:

pdfopt

input.pdf output.linearized.pdf

Prepare the Server

Both Apache, Versions 1.3.17 and greater, and Microsoft IIS, Versions 3 and greater, should serve PDF pages on demand without additional configuration. The key to serving PDF pages on demand is byte range support by the web server. HTTP 1.1 describes byte range support (http://www.freesoft.org/CIE/RFC/2068/160.htm). Byte range support means that the client can request a specific range of bytes from the web server. Instead of serving the entire file, the server will send just those bytes.

The web server must indicate its support for byte ranges by sending the “Accept-Ranges: bytes” header in response to a PDF file request. Otherwise, Acrobat might not attempt page-at-a-time downloading. If you want to tell clients to not attempt page-at-a-time serving from your server, send the “Accept-Ranges: none” header instead.

Force PDF Download Rather than Online Reading

Prevent your online PDF from appearing inside the browser.

Some PDF documents on the Web are intended for online reading, but most are intended for download and then offline reading or printing. You can prevent confusion by ensuring your readers get the Save As . . . dialog when they click your Download Now PDF link. Here are a few ways to do this.

Tip

Keep in mind that any online PDF can be downloaded. If your online PDF is hyperlinked to integrate with your web site, you should take precautions against these links being broken upon download.

One option is to use only absolute URLs throughout your PDF.

Another option is to set the Base URL of your PDF. In Acrobat 6, consult File → Document Properties → Advanced → Base URL. In Acrobat 5, consult File → Document Properties → Base URL.

To prevent people from easily downloading your document, see [Hack #71] .

Zip It Up

The quickest solution for a single PDF is to compress it into a zip file, which gives you a file that simply cannot be read online. This has the added benefit of reducing the download file size a little. The downside is that your readers must have a program to unzip the file. You should include a hyperlink to where they can download such a program (e.g., http://www.info-zip.org/pub/infozip/). Stay away from self-extracting executables, because they work on only a single platform.

You can also apply zip compression on the fly with your web server.

Here is an example in PHP. Adjust the passthru

argument so that it points to your local copy of

zip:

<?php

// pdfzip.php, zip PDF at serve-time

// version 1.0

// http://www.pdfhacks.com/serving_pdf/

//

// WARNING:

// This script might compromise your server's security.

$fn= $_GET['fn'];

// as a security measure, only serve files located in our directory

if( $fn && $fn=== basename($fn) ) {

// make sure we're zipping up a PDF (and not some system file)

if( strtolower( strrchr( $fn, '.' ) )== '.pdf' ) {

if( file_exists( $fn ) ) {

header('Content-Type: application/zip');

header('Content-Disposition: attachment; filename='.$fn.'.zip');

header('Accept-Ranges: none'); // we don't support byte serving

passthru("/usr/bin/zip - $fn");

}

}

}

?>If you have a PDF located at http://www.pdfhacks.com/docs/mydoc.pdf and you copied the preceding script to http://www.pdfhacks.com/docs/pdfzip.php, you could serve mydoc.pdf.zip with the URL http://www.pdfhacks.com/docs/pdfzip.php?fn=mydoc.pdf.

Create Download-Only Folders Using .htaccess Files

Do you have an entire directory of download-only PDFs on your web server? You can change that directory’s .htaccess file so that visitors are always prompted to download their PDFs. The trick is to send suitable Content-Type and Content-Disposition HTTP headers to the clients.

This works on Apache and Zeus web servers that have their .htaccess features enabled. In your PDF directory, add a file named .htaccess that has these lines:

<files *.pdf> ForceType application/octet-stream Header set Content-Disposition attachment </files>

Serve PDF Downloads with a PHP Script

This next script enables you to serve PDF downloads. It is handy for when you want to make a single PDF available for both online reading and downloading. You can use its technique of using the Content-Type and Content-Disposition headers in any script that serves download-only PDF.

<?php

// pdfdownload.php

// version 1.0

// http://www.pdfhacks.com/serving_pdf/

//

// WARNING:

// This script might compromise your server's security.

$fn= $_GET['fn'];

// as a security measure, only serve files located in our directory

if( $fn && $fn=== basename($fn) ) {

// make sure we're serving a PDF (and not some system file)

if( strtolower( strrchr( $fn, '.' ) )== '.pdf' ) {

if( ($num_bytes= @filesize( $fn )) ) {

// use file pointers instead of readfile( )

// for better performance, esp. with large PDFs

if( ($fp= @fopen( $fn, 'rb' )) ) { // open binary read success

// try to conceal our content type

header('Content-Type: application/octet-stream');

// cue the client that this shouldn't be displayed inline

header('Content-Disposition: attachment; filename='.$fn);

// we don't support byte serving

header('Accept-Ranges: none');

header('Content-Length: '.$num_bytes);

fpassthru( $fp ); // this closes $fp

}

}

}

}

?>If you have a PDF located at http://www.pdfhacks.com/docs/mydoc.pdf and you copied the preceding script to http://www.pdfhacks.com/docs/pdfdownload.php, the URL http://www.pdfhacks.com/docs/pdfdownload.php?fn=mydoc.pdf would prompt users to download mydoc.pdf to their computers.

Hyperlink HTML to PDF Pages

Take readers directly to the information they seek.

You can use HTML hyperlinks, those famous filaments of the Web, to integrate PDF documents with HTML documents. A simple link to a PDF document is not enough, though, because a single PDF might hold hundreds of pages. It is like handing a haystack to somebody searching for a needle. The solution is to modify the HTML link so that it takes the reader directly to the PDF page of interest. This kind of seamless integration of HTML and PDF pages requires some groundwork. See [Hack #67] for details.

To tailor a hyperlink’s PDF destination, just add one or more of the suffixes listed in Table 5-3 to the href path.

These are glued together and appended to the href path using a special notation. The first suffix follows a hash mark. Each additional suffix follows an ampersand. These options are fully documented in PDF Open Parameters, located at http://partners.adobe.com/asn/acrobat/sdk/public/docs/PDFOpenParams.pdf.

For example, to open mydoc.pdf to page 17 and display its document bookmarks, the hyperlink href would look like this:

http://pdfhacks.com/mydoc.pdf#page=17&pagemode=bookmarks

Tip

These special PDF hyperlinks do not work when you’re using Internet Explorer and the PDF is on your local disk. For a workaround, see [Hack #17] .

Save Display Settings in the PDF

You can also save these display settings in the PDF file. Whenever and however the PDF is opened, it will be displayed according to your settings. See [Hack #62] for details.

Create an HTML Table of Contents from PDF Bookmarks

Give web surfers an inviting HTML gateway into your PDF.

When browsing the Web, I usually groan at the sight of a PDF link. You have probably experienced it, too. My research has brought me to this point where I must now download a large PDF before I can proceed. The problem isn’t so much with the PDF file, but with my inability to gauge just how much this PDF might help me before I commit to downloading it.

The PDF author might have even gone to great lengths to ensure a good, online read, with nice, clear fonts, navigational bookmarks, and page-at-a-time byte serving for quick, random access. But I can’t tell that from looking at this PDF link. Chances are that I’ll click and wait, and wait. When it finally opens, I’ll probably need to flip, page by page, through illegible text looking for a clue that this tome will help me somehow. I might never find out, especially because I have a dozen other possible lines of inquiry I am pursuing at the same time.

Don’t let this happen to your online PDF. If your PDF has bookmarks, use this hack to create an HTML table of contents that hyperlinks every heading directly to its PDF page (see Figure 5-16.

Tip

This kind of random access into an online PDF is convenient only if the PDF is linearized and the web server is configured for byte serving [Hack #67] . Without both of these, your readers must download the entire document before viewing a single page.

Create a PDF Table of Contents in HTML with pdftk and pdftoc

pdftk [Hack #79] can report on PDF data, including bookmarks. pdftoc converts this plain-text report into HTML. Visit http://www.pdfhacks.com/pdftoc/ and download pdftoc-1.0.zip. Unzip, and move pdftoc.exe to a convenient location, such as C:\Windows\system32\. On other platforms, build pdftoc from the source code.

Use pdftk to grab the bookmark data from your PDF, like so:

pdftkdump_data output

Next, use pdftoc to convert this plain-text report into HTML:

pdftoc>

Alternatively, you can run these two steps together, like so:

pdftkdump_data | pdftoc>

The first argument to pdftoc is the document location that you want pdftoc to use in its hyperlinks. The previous example assumes that mydoc.pdf and mydoc_toc.html will be in the same directory. You can also give a relative path to your PDF, like so:

pdftoc<>

or a full URL:

pdftoc<>

Once readers enter the PDF, they can use its bookmarks for further navigation. To ensure they see your bookmarks, set your PDF to display them upon opening [Hack #62] .

You can also add a download link [Hack #68] on the web page that prompts the user to save the PDF on her local disk. As a courtesy to the user, mention the download file size, too.

PDF Web Skins

Split a PDF into pages and frame them in HTML, where the fun begins.

In general, HTML files are called pages, while PDF files are called documents. By splitting a PDF document into PDF pages we shift it into HTML’s paradigm where we now can program the document like a web site. Let’s start with a basic document skin, shown in Figure 5-17, which gives us a cool look and handy document navigation.

Our Classic skin has a number of nice built-in features:

Table of contents portal page based on PDF bookmarks

Navigation cluster for flipping through pages

Table of Contents navigation sidebar based on PDF bookmarks

A hyperlink to the full, unsplit PDF for download on each page

Convenient Email This Page link on each page

Test-drive our online version at http://www.pdfhacks.com/eno/. The HTML, JavaScript, and user interface icons are freely distributable under the GPL, so feel free to use them in your own templates.

Skinning PDF

First, install pdftk

[Hack #79]

. Next, visit

http://www.pdfhacks.com/skins/

and download pdfskins-1.1.zip.

Unzip, and move pdfskins.exe to a convenient

location, such as C:\Windows\system32\. On other

platforms, compile pdfskins from the included source code. Just

cd

pdfskins-1.1 and run

make.

Download a skin template from http://www.pdfhacks.com/skins/. The template pdfskins_classic_js uses client-side JavaScript to create the dynamic pieces. pdfskins_classic_php uses server-side PHP instead. Pick one and unzip it into a new directory:

unzip pdfskins_classic_js-1.1.zipCopy your PDF document into this new directory and burst it into pages with pdftk. This also creates doc_data.txt, which reports on the document’s title, metadata, and bookmarks:

pdftkburst

Finally, in this same directory, spin skins using pdfskins. It reads doc_data.txt, created earlier, for the document title and other data. Pass the PDF filename as the first argument, if you plan to make the full PDF document available for download. This first argument is used only for constructing the Download Full Document hyperlink. It can be a full or relative URL. Omit this filename, and this hyperlink will not be displayed.

pdfskins Fire up your web browser and point it at index.html, located in the directory where you’ve been working. The portal should appear, showing the table of contents and graphic placeholders for your logo (logo.gif) and document cover thumbnail (thumb.gif). If you used the php or comments templates, the pages must be served to you by a PHP-enabled web server.

Tip

The PDF pages that make up our skinned PDF do not need to be linearized; nor does the web server require byte serving configuration [Hack #67] . The only requirement is that the user has Adobe Reader configured to display PDF inside the browser, which is the default Reader configuration.

Changing Colors, Overriding the Title

You can add or change data in the doc_data.txt file, or you can pass additional, overriding data to pdfskins on the command line. This is most useful for changing the default colors used in the Classic skin. For example:

pdfskins full_doc.pdf -title "Great American Novel" -color1 #336600 \ -color2 white

In the Classic skin, color1 is the color of the

header and color2 is the color around the

upper-left logo. Alternatively, you can add or change these lines in

doc_data.txt:

InfoKey: Color1 InfoValue: #336600 InfoKey: Color2 InfoValue: white InfoKey: Title InfoValue: Great American Novel

PDF Skins as Copy Protection

By bursting your PDF into pages and then not making the full document available for download, you compel readers to return to your site when they desire your material. If this is your intent, you should also secure your pages against merging, so nobody can easily reassemble your pages into the original PDF document. Do this when bursting the document. For example:

pdftk full_doc.pdf burst encrypt_128bits owner_pw 23@#5dfa \ allow DegradedPrinting

See [Hack #52] for more details on how to secure documents with pdftk.

Tip

Test our PHP-based hacks on your Windows machine by installing the Apache web server. See [Hack #74] for a discussion about installing Apache and PHP on Windows using IndigoPerl.

Hacking the Hack

Now, you control the document. You can take it in any direction you choose. See [Hack #21] for some ideas on how to add full-text document search. See [Hack #72] to learn how to add online page commenting.

Share PDF Comments Online (Even Without Acrobat)

Use our PDF skins to add commenting features to PDF pages.

Using Acrobat, you can add various comments and annotations to PDF pages. You can also share these comments via email or by configuring Acrobat’s Online Comments. These collaboration tools require all contributors to have Acrobat; they do not work with Reader. And, in general, all contributors must have the same version of Acrobat.