Use Built-in Automation Features

Although it may not be apparent at first glance, OS X contains dozens of built-in automation features, just waiting for you to make use of them. In fact, later in this book, I’ll discuss numerous ways to take advantage of built-in features, such as:

- Use Trackpad and Magic Mouse Gestures

- Use OS X’s Text Replacement

- Use the Spotlight Menu as a Launcher

- Use OS X Automation Technologies (Services, Automator, AppleScript, and shell scripts)

- Manage Incoming Apple Mail with Rules

- Search Faster with Smart Mailboxes

- Log In Faster with iCloud Keychain and Safari Autofill

- Run Backups Automatically with Time Machine

But in this chapter, I want to introduce you to a core set of built-in automation capabilities that don’t fit logically within another topic—or that don’t go as far as the more capable third-party tools that I discuss later in this book. Most of these involve things you can do in the Finder or in System Preferences, and they’re among the easiest ways to start automating your Mac.

Find Files Faster with Finder Tags

Mavericks added tags to the Finder. A tag is a text label you create yourself—a word or phrase that tells you something about what’s in a file. For example, you might use the word recipe as a tag and apply it to any document that contains a recipe. That would enable you to quickly locate recipes later, even if none of them contain the actual word “recipe” in their title or contents.

Any file can have more than one tag. So you might apply the tags recipe, dessert, French, and vegetarian to your recipe for crème brûlée. Other files would have different combinations of tags, and as you search by tags, only those that match the combination you specify would show up.

You can use tags instead of, or in addition to, hierarchical filing in nested folders. You might have tax-related documents scattered in dozens of folders on your disk, but if they’re all tagged with tax info, you can instantly see them all in one place. (The Finder also allows you to associate a color with your text labels to make them easier to identify quickly.)

If you apply tags to files you create or download, that makes it quicker and easier for you to find them later—either manually or as part of a smart folder (see Create and Use Smart Containers). Ergo: a shortcut!

To apply a tag:

- Select one or more files in the Finder.

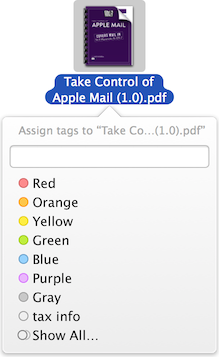

- Choose File > Tags, and then, in the popover that appears (see Figure 1), do one of the following:

- To add a new tag, type a word or phrase. Press Return; this creates the tag and applies it to the file(s).

- To add an existing tag that isn’t one of the default options, start typing its name. OS X will attempt to autocomplete the name with matches from your existing list, and you can also use the Up or Down Arrow keys to select the right one. Then press Return.

- To add one of the default tags (or a tag you’ve manually added as a favorite, as described ahead), choose a dot from the bottom of the File menu (hover over a dot to see the tag’s name). Repeat as desired to add more tags.

Figure 1: Use this popover to add tags to a file.

To manage tags:

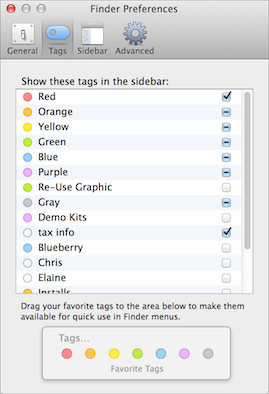

- Choose Finder > Preferences > Tags (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Tags can be reordered, renamed, and shown or hidden in the Finder sidebar or menu by making adjustments in this window.

- You can now do any of the following:

- Edit a tag’s name: Double-click it and type a new name.

- Change a tag’s color: Click the colored dot to its left and choose a new color from the pop-up menu.

- Show a tag in the sidebar of Finder windows: Select its checkbox.

- Change the order in which tags appear in the sidebar: Drag them to a new location.

- Assign a color to a custom tag: Click the (initially white) dot to the left of the tag’s name and choose one of the eight possible colors from the pop-up menu.

- Add favorite tags to the default list (the row of colored dots at the bottom): Drag a tag to that area.

- Delete a tag: Right-click (or Control-click) it and choose Delete Tag “Tag Name” from the contextual menu.

To find tagged files:

- Sidebar: Select a tag in the sidebar of any Finder window to see all the files with that tag.

- Find: Type a tag name in the search field at the top of any Finder window and then select the tag name from the pop-up list to find all files with that tag. You can add multiple tags to your search, with or without other text or attributes, to look for files with all those tags (or attributes).

- Smart folder: To save the search as a smart folder, do a find as in the last point, but then click Save. Give the saved search a name and, for quicker access, select Add to Sidebar. Click Save. Then you can select that sidebar item at any time to display all items with the selected tag(s).

Use OS X’s Built-in Keyboard Shortcuts

Every app that comes with OS X, including the Finder, has keyboard shortcuts for common commands.

Menu Shortcuts

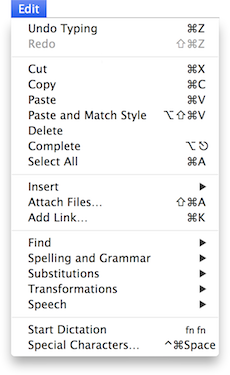

The best-known type of keyboard shortcut performs a menu command. You can see the shortcuts right on the menus (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Examples of menu commands with predefined keyboard shortcuts.

The symbols represent modifier keys:

- ⌘ means Command

- ⌥ means Option

- ^ means Control

- ⇧ means Shift

So, if you see a command labeled ^⌘T (File > Add to Sidebar in the Finder), that means hold down both the Control key and the Command key and press T.

The easiest way to learn what keyboard shortcuts are available for menu commands is to take a look at the menus as you use them. Although every app has its own set of shortcuts, most apps are consistent in their use of a number of common shortcuts, such as:

- ⌘A for Select All

- ⌘B for Bold

- ⌘C for Copy

- ⌘D for Duplicate

- ⌘F for Find

- ⌘I for Italic

- ⌘N for New

- ⌘O for Open

- ⌘P for Print

- ⌘Q for Quit

- ⌘S for Save

- ⌘U for Underline

- ⌘V for Paste

- ⌘W for Close

- ⌘X for Cut

- ⌘Z for Undo

- ⌘, for Preferences

- Return to click the default (highlighted) button in any dialog

- ⌘. or Esc to cancel the current action

Every Mac user should know these common shortcuts cold, because they’re useful in nearly every app.

For many more common shortcuts, see Apple’s OS X keyboard shortcuts page.

In addition, you should know a couple of general principles about menu commands. These are not hard-and-fast rules, but they’re overall trends worth being aware of:

- Adding Shift to a shortcut often reverses its meaning. For example, press Command-Tab to switch to the next open application, or Command-Shift-Tab to switch to the previous application. Or, in the Finder, while Command-Z is Undo, Command-Shift-Z is Redo.

- Adding Option to a shortcut often applies the command to a broader scope. For example, in the Finder, Command-M is Minimize (to minimize an open Finder window), while Command-Option-M is Minimize All (as in minimize all Finder windows). In TextEdit, Command-W is Close (a document), while Command-Option-W is Close All (open documents).

- Adding multiple modifiers to a shortcut often means “the same thing, but with different options.” For example, Command-V is Paste, but in most apps, Command-Option-Shift-V (or sometimes just Command-Shift-V) is Paste as Plain Text. Similarly, Command-Shift-S is often Duplicate (that is, save the entire document as a duplicate) whereas Command-Option-Shift-S is Save As (that is, save the entire document with a different name).

Text Editing Shortcuts

Besides shortcuts for menu commands, OS X has many built-in shortcuts for working with text. Here are a few you should know:

- Arrow keys: Move the insertion point in the direction of the arrow.

- Option-Left Arrow or Option-Right Arrow: Move the insertion point left or right by a word.

- Command-Left Arrow or Command-Right Arrow: Move the insertion point to the beginning or end of the current line.

- Option-Up Arrow or Option-Down Arrow: Move the insertion point to the beginning or end of the current paragraph.

- Command-Up Arrow or Command-Down Arrow: Move the insertion point to the top or bottom of the document.

- Shift plus any of the above: Select the text from here to the destination. For example, Option-Shift-Right Arrow selects the next word; Command-Shift-Left Arrow selects to the beginning of the line.

Spend an hour or so practicing these shortcuts and you’ll be able to do much of your text editing without reaching for a mouse or other pointing device.

Create Your Own OS X Keyboard Shortcuts

If a menu command in one of the apps you use doesn’t already have a keyboard shortcut—or if it does, but you want to change it to something different—follow these steps to create your own:

- Go to System Preferences > Keyboard > Shortcuts > App Shortcuts.

- Click the plus

button.

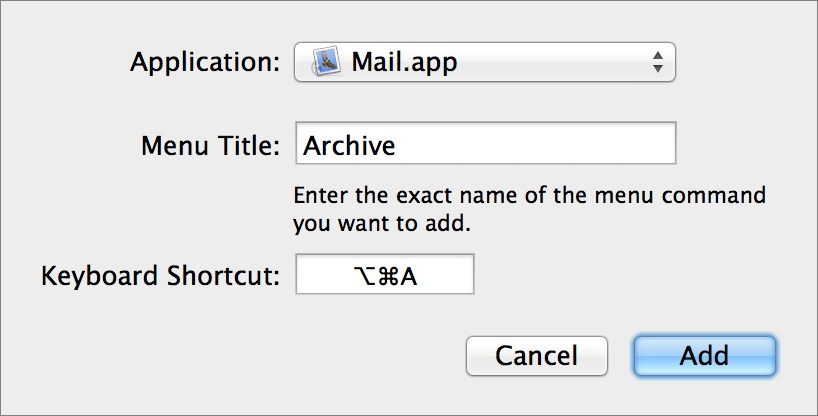

button. - In the dialog that appears (Figure 4), select the app you want the shortcut to work with from the pop-up Application menu. (If you don’t see it listed there, choose Other, navigate to the application, and click Add.) If you want your shortcut to work in all applications (or in, say, the pop-up PDF menu that appears in the Print dialog of all your apps), choose All Applications from the pop-up menu.

Figure 4: Specify the application, menu command, and keyboard shortcut in this dialog.

- Enter the menu command (not the name of the menu itself) for which you want to specify a shortcut in the Menu Title field.

You must get everything—including capitalization, punctuation, and spaces—exactly correct. If what you type here doesn’t precisely match what’s on the menu, it won’t work. One exception: If you see an ellipsis (…) at the end of a command, you can type either the single ellipsis character (Option-;) or three periods. Either way works.

- Click in the Keyboard Shortcut field and press the key combination you want to use. (If another command previously used the shortcut you enter, your new shortcut will override it.)

- Click Add.

The new shortcut should immediately appear next to the menu command in the app—even if the app is still running—and can be used right away.

Sometimes an app has two or more menu commands with the same name, located on different menus or submenus. For example, in Mail, you can find Format > Quote Level > Increase as well as Format > Indentation > Increase. Likewise, the mailbox names on the Message > Move to and Message > Copy to submenus are the same. So if you specify only the menu command name (like Increase), it may not connect to the right command.

To address this problem, instead of entering just the menu command name, enter the full path through all the submenus, with -> (that is, a hyphen followed by a greater-than sign)—and no spaces—between each step, like so: Format->Quote Level->Increase. This ensures that the shortcut goes only with the menu command you specify.

If you’re uncertain what keyboard shortcuts might be useful, here are some ideas to get you started:

- If you frequently assign tags to files (see Find Files Faster with Finder Tags), you may want to assign a keyboard shortcut to the Finder’s File > Tags… command. Command-T, Command-Shift-T, and Command-Option-T are already used by other menu commands, but you can reassign any of them to Tags… if you like.

- How about an All Applications keyboard shortcut to open System Preferences (found with a trailing ellipsis […]—on the Apple menu)?

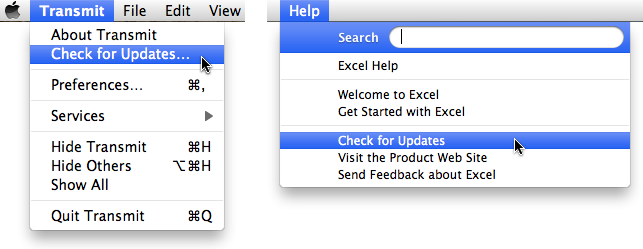

- Lots of apps have Check for Updates… commands (usually on the application menu—the one bearing the application’s name), but that command almost never has a keyboard shortcut. If you use that command frequently, it might benefit from an All Applications shortcut.

- Your keyboard may have keys you rarely if ever press (F13–F15, anyone?), and they can be put to good use. Most of these keys have preassigned shortcuts, which you can see by looking through the various categories of System Preferences > Keyboard > Shortcuts, but if you think a key can serve you better by performing a different action, you should feel completely free to change it.

Use OS X Text Substitutions and Transformations

If you look at the Edit menu in TextEdit, Mail, Messages, Safari, and numerous other applications that include text editing features, you’ll see a Substitutions submenu and a Transformations submenu. These two submenus contain shortcuts for manipulating text. You don’t have to do anything to make them appear (and you can’t add the commands in apps that don’t natively support them), but I think everyone should know about them, because they’re often useful—yet overlooked.

Substitutions

As you work with text in supported apps, OS X can automatically change certain attributes in order to make your text more readable and useful. When an item on the Edit > Substitutions submenu is checked, it means that substitution is enabled for that app (only) until you deselect it. (Choose a menu command again to toggle it.)

Substitution options are as follows:

- Smart Copy/Paste: If you double-click a word to select it, and then copy and paste it, a space is added before and/or after if necessary to separate it from the adjacent text. Similarly, if you double-click a word to select it and then press Delete, extra spaces are removed. (Smart copy/paste does not occur if you manually drag to select the word.)

- Smart Quotes: As you type, this feature converts straight quotation marks and apostrophe (

" ') into curly quotation marks and apostrophes (“” ‘’). - Smart Dashes: As you type, this feature converts two consecutive hyphens (

--) into an em dash (—). - Smart Links: As you type, this feature converts URLs (including strings OS X interprets as URLs, even if they don’t start with a scheme such as

httporhttps) into clickable links. - Data Detectors: This feature intelligently identifies strings of text that match patterns like street addresses, dates (even vaguely stated dates, like “next Tuesday” or “breakfast tomorrow”), phone numbers, and flight numbers—and then lets you do appropriate things with them like add an entry to Contacts, schedule an event in Calendar, look up a location in Maps, track a flight, and so on.

With Data Detectors enabled, if you see a chunk of text that looks like one of the kinds of data I just mentioned, move your pointer over it. If Data Detectors considers it to be an appropriate kind of data, a dotted box will appear around it, with a downward pointing triangle on the right. Click the triangle

to display either a contextual menu with one or more options, or a popover with additional controls, depending on the type of data.

to display either a contextual menu with one or more options, or a popover with additional controls, depending on the type of data. - Text Replacement: As you type, this feature replaces abbreviations with user-specified words or phrases—or corrects misspellings. (This feature is important enough that I talk about it separately; see Use OS X’s Text Replacement.)

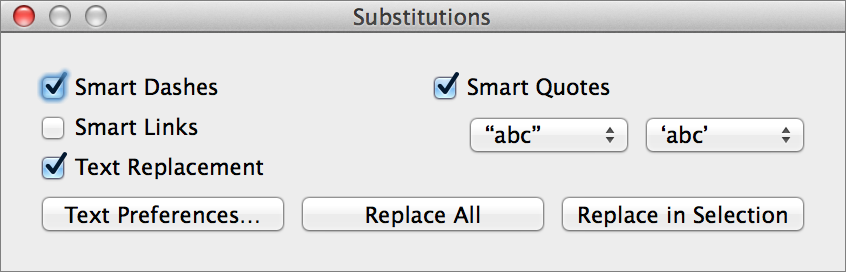

- Show Substitutions: Select this command to display the Substitutions window (Figure 5), in which you can change any of your settings for the current app (selecting or deselecting the checkboxes has the same effect as selecting the corresponding menu command) or apply substitutions retroactively.

You’ll notice that for smart quotes, smart dashes, smart links, and text replacement, I mentioned earlier in the list that substitutions occur as you type. In other words, if you open a document that already contains straight quotation marks, double hyphens, or plain-text links, OS X does not convert them automatically. If you want to make such conversions after the fact, open the Substitutions window, select the desired checkboxes, and click Replace All (to affect the entire document) or select a portion of the text and click Replace in Selection.

You’ll notice that for smart quotes, smart dashes, smart links, and text replacement, I mentioned earlier in the list that substitutions occur as you type. In other words, if you open a document that already contains straight quotation marks, double hyphens, or plain-text links, OS X does not convert them automatically. If you want to make such conversions after the fact, open the Substitutions window, select the desired checkboxes, and click Replace All (to affect the entire document) or select a portion of the text and click Replace in Selection.

Transformations

The Transformation submenu contains three commands that change the case of the selected text:

- Make Upper Case: Converts all lowercase letters to their uppercase equivalents

- Make Lower Case: Converts all uppercase letters to their lowercase equivalents

- Capitalize: Converts the first letter of each word in the selected text to uppercase (regardless of whether that would constitute proper “title case”)

Control Your Mac with Speakable Items

Macs have had built-in speech recognition for a long time. Although this was cool when it first appeared in the mid-1990s, I’m sorry to say that Apple has paid little attention to this feature over the years, and it doesn’t work especially well. Perhaps a future version of OS X will include Siri’s much more advanced capabilities, but for now, it’s possible to get at least basic voice control with Speakable Items. And for the purpose of this book, the interesting point is that you can create your own voice commands to open documents and apps, run scripts, press keys, and do other custom activities—that is, your voice can trigger shortcuts, just like a menu command or keyboard shortcut.

To use Speakable Items:

- Go to System Preferences > Accessibility > Speakable Items > Settings.

- Select the On radio button. A floating window appears (Figure 6).

Figure 6: This window shows the current status of Speakable Items.

- Hold down the Esc key and speak a command or query, such as “What time is it?” or “Switch to Finder.”

If you’re lucky, what you expect will happen! (And, if you’re done playing with this feature and you want to get rid of that floating window, go back to System Preferences > Accessibility > Speakable Items > Settings and select the Off radio button.)

OS X comes with many speakable commands for built-in applications, and some third-party applications add their own commands. To see what it’s possible to say, press and hold Esc to activate Speakable Items and say, “Show me what to say.” A floating window appears with a list of all possible commands. Although that list is quite long—and Speakable Items does understand some small variants in phrasing—it doesn’t come close to the plain-English comprehension capabilities of Siri.

However, you can add your own items to this list! Apple provides simple instructions to do so on the page OS X Mountain Lion: Create spoken commands (which also applies to Mavericks). You might use this, for example, to speak commands like these:

- Say, “Computer, surf!” to run an AppleScript (see Get to Know AppleScript) that opens all your favorite Web sites in Safari tabs.

- Say, “Computer, boilerplate” to insert a predefined reply into an email message you’re composing.

- Say, “Computer, fix this!” to trigger a keystroke that runs a Nisus Writer Pro macro (see Create Macros in Nisus Writer Pro) to correct formatting issues in your current document.

If you like, you can eliminate the need to press Esc and instead use a trigger word. For example, if you preface each command with “Computer…” that can alert Speakable Items that the next thing you say should be interpreted as a command. To do this, go to System Preferences > Accessibility > Speakable Items > Listening Key. Select Listen Continuously with Keyword, optionally enter a different name (yes, you can call your computer “Cindy” if you want to), and choose an item from the Keyword Is pop-up menu to specify whether the keyword is optional, required before every command, or required only 15 or 30 seconds after the last command.

To learn more about Speakable Items, read the Apple support article OS X Mountain Lion: Create spoken commands (which still applies to Mavericks).

You can also create your own speakable items using Automator; for instructions, see Speakable-Workflows at Mac OS X Automation.

Keep Tabs on Important Activities with Notifications

If you’ve used Mavericks (or its predecessor, Mountain Lion) for any period of time, you’ve undoubtedly seen the system-wide Notifications feature, which puts little messages in the upper-right corner of your screen to tell you about things like new email messages, Twitter mentions, and birthdays.

Although they may sometimes seem more like time-wasters than time-savers, notifications can become useful automation tools when you tailor them to your needs, using them to reveal important information that would otherwise require significant digging.

First, the basics. To determine what the system does when an app sends a notification:

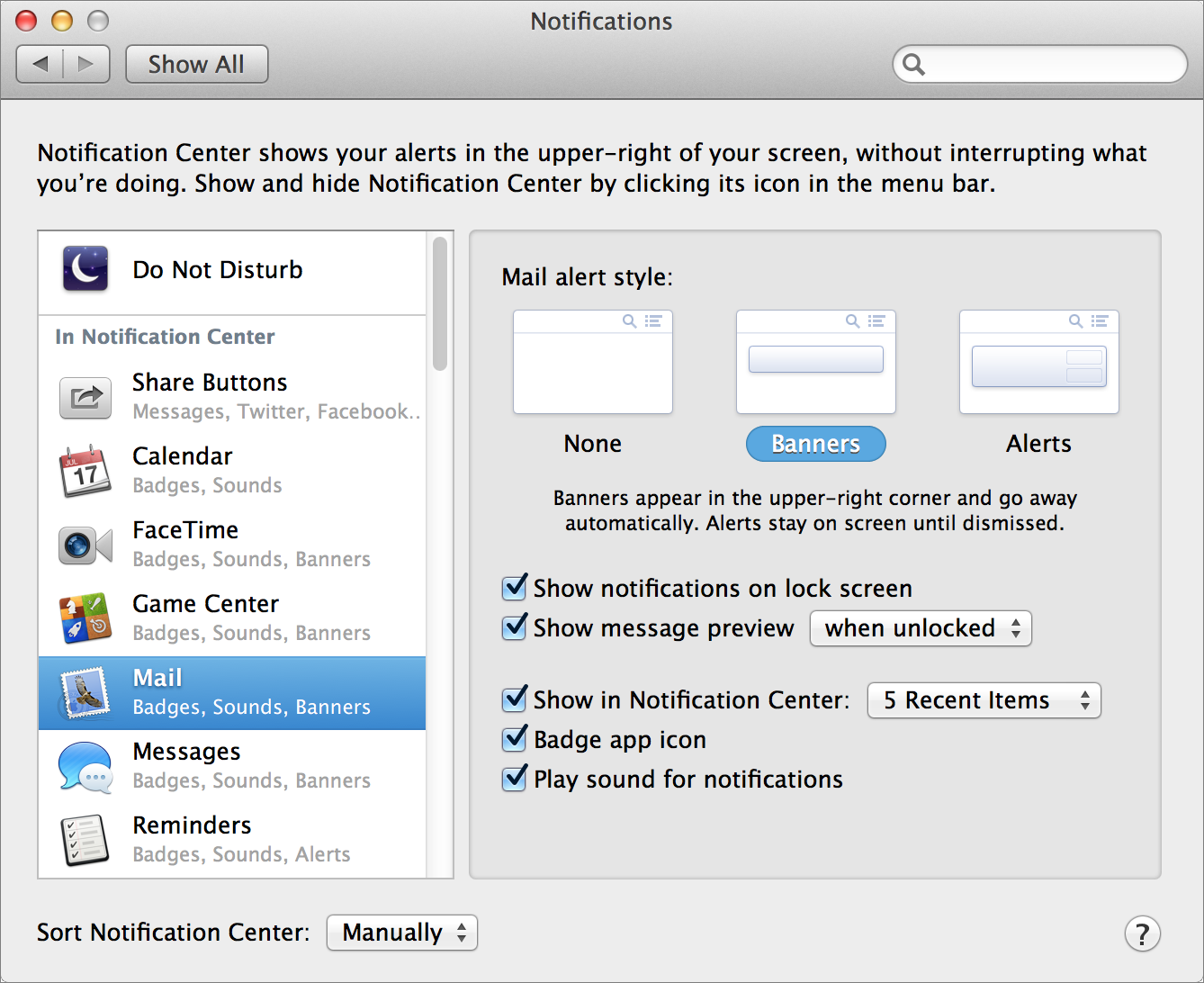

- Go to System Preferences > Notifications (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Set system-wide notifications for each app in the Notifications pane of System Preferences.

- Select an app in the list on the left.

- Click None, Banners, or Alerts to set what type of notification (if any) should appear when the app needs to notify you of something. Banners appear and then fade away automatically after a few seconds, whereas Alerts stay on screen until you dismiss them.

- Select Show Notifications on Lock Screen if you want to display notifications for that app when your Mac’s screen is locked and requires a password (configure the screen lock in System Preferences > Security & Privacy > General).

- Set any other options, which vary from app to app, to meet your needs. For example, you can determine whether a notification from Mail includes a preview of the messages.

- To set the maximum number of notifications for this app that can accumulate in Notification Center—the global list of alerts that appears when you click the list

icon in the upper-right corner of your screen—choose 1, 5, 10, or 20 Recent Items from the Show in Notification Center pop-up menu. Or, to prevent notifications from appearing in Notification Center at all, uncheck the box here.

icon in the upper-right corner of your screen—choose 1, 5, 10, or 20 Recent Items from the Show in Notification Center pop-up menu. Or, to prevent notifications from appearing in Notification Center at all, uncheck the box here. - If you want to prevent Notification Center from listing the number of outstanding notifications on the app’s Dock icon, uncheck Badge App Icon.

- If you want to prevent Notification Center from playing a sound when a notification occurs from this app, uncheck Play Sound for Notifications.

Changes take place immediately.

Having set up those system-wide preferences, you need to visit each individual app’s preferences to determine which events or conditions trigger a notification. That’s where the real power comes in.

Every app is different, but let me give you some ideas about uses for notifications that may not be immediately obvious:

- Mail: You can set Mail’s preferences to trigger a notification whenever a new message arrives in your Inbox, any mailbox, or a particular smart mailbox; or when you receive a message from a sender you’ve designated as a VIP, or from anyone in your Contacts list. You can even have a rule trigger a notification according to any criteria you choose (see Manage Incoming Apple Mail with Rules).

- AppleScript and Automator: If you use either of these tools to automate your Mac (see Use OS X Automation Technologies), you can include a command to display a notification when any desired condition exists. (In AppleScript, it’s

display notification [text]; in Automator, use the Display Notification action.) For example, you might have an AppleScript Folder Action display an alert when someone adds a file to a shared folder. For more details, see the System Notifications Support page at Mac OS X Automation. - Macros: Keyboard Maestro (see Control Your Mac with Keyboard Maestro) can trigger a notification as a step in any macro—which means you have almost unlimited control over what conditions result in a notification. For example, you might have a macro that runs every hour to check for certain text on a Web page, and it could display a banner if the text exists.

Log In to Your Mac Automatically

When you first set up a new Mac, part of the process involves creating an administrator account for yourself as the owner. If you stick with the default settings, OS X logs you in automatically with that account whenever you turn on or restart your Mac.

The alternative is to select or enter your username and then type your account password. And that’s a safer approach, because it means that if your Mac were lost or stolen, or if someone else got access to it, there’d be at least a modest barrier between any other user and your data. However, if you’re confident enough in your Mac’s physical security to enable automatic login and it’s currently disabled, you can turn it back on as follows:

- Go to System Preferences > Security & Privacy > General.

- Click the lock

icon and enter your password.

icon and enter your password. - If Disable Automatic Login is selected, deselect it. (If it’s already deselected, you’re done.)

- Choose your username from the Automatically Log In As pop-up menu and enter your password.

- Click OK.

The next time you turn on or restart your Mac, it logs you in automatically and you’ve just saved yourself a bit of time every day.

Open Items Automatically on Login

Why waste time every morning opening up Mail, Safari, and whatever other apps or documents you always use? Instead, set them to open automatically so you’ll be good to go.

You log in—either explicitly (by entering your username and password) or implicitly (using Automatic Login, described just previously)—when you turn on or restart your Mac, or when one user logs out (Apple > Log Out Username) and another logs in. Whenever that happens, OS X can open apps, folders, or documents for you.

To configure any item currently in your Dock to open on Login, click and hold on its Dock icon and choose Options > Open at Login from the contextual menu.

To configure other items to open on login:

- Go to System Preferences > Users & Groups > Login Items.

- Drag any item (application, file, folder, server, etc.) from the Finder to the list. Alternatively, click the plus

button, navigate to the item you want to open, and click Add.

button, navigate to the item you want to open, and click Add. - To hide any app (that is, to achieve the same effect as opening the app and choosing Hide App Name from the application menu), select its Hide checkbox.

The next time you log in, the specified items open automatically. (To remove an item from this list, select it and click the minus  button.)

button.)

Sleep, Wake, and Shut Down on a Schedule

You can shut down your Mac or put it to sleep manually whenever you want by using commands on the Apple menu, but you can also configure your Mac to shut down, sleep, or wake on a schedule. The main reason to bother with this is to save electricity. Even though modern Macs don’t use very much, it does add up over time. Once you’ve got this set up, your Mac will be ready and waiting for you when you arrive to work in the morning.

To configure automatic shutdown, sleep, and wake settings:

- Go to System Preferences > Energy Saver.

- If your Mac is a laptop, click either Battery or Power Adapter to configure its behavior with that power source (and then repeat the process with the other source).

- To schedule automatic sleep after an idle period, drag the Computer Sleep slider to the desired time period (or Never, to never sleep automatically). You can independently adjust Display Sleep, if you like. (Depending on your Mac model, your options may be slightly different here.)

- To spin down any internal or external hard disks (not applicable to SSDs), select Put Hard Disks to Sleep When Possible.

- Click Schedule, and then:

- To schedule automatic startup (if your Mac is shut down at the scheduled time) or wake (if it’s asleep), check Start Up or Wake. Then choose a day or range from the pop-up menu (such as Every Day, Weekdays, or Thursday) and enter a time.

- To schedule automatic sleep, restart, or shutdown on a fixed schedule, select the second checkbox, choose Sleep, Restart, or Shut Down from the pop-up menu, and again set the desired day(s) and time.

Your Mac then sleeps, shuts down, and/or wakes according to your new settings.

Update Apple and Mac App Store Software Automatically

In Mavericks, all updates to Apple software (including OS X itself, built-in software such as Safari and QuickTime, and optional purchases such as iPhoto and Pages), are delivered through the Mac App Store app. And, of course, you can update all the third-party apps you’ve purchased from the App Store at the same time.

To check for updates manually, you open the App Store app and click the Updates button on the toolbar. (As a shortcut, choose Apple > Software Update.) Then, to update a single application, click the Update button next to it. (In some cases, Apple groups multiple software updates together; click the More link to see details on each one.) To update all the listed applications at once, click Update All. Enter your Apple ID and password if prompted to do so, and click Sign In. The App Store downloads and installs the updates.

But this is a book about automation, so we’re more interested in how to make this happen automatically! You can have Software Update merely inform you of future updates or download (and optionally install) them as soon as they appear.

Because software updates often fix crucial bugs and add important features, I like to learn about them as soon as possible. And, because I install almost every update, it saves time to let OS X download updates automatically in the background. I don’t necessarily install updates as soon as they appear, because I might be busy with things that can’t be interrupted—and I want to know when something might be about to change—but some people may choose to do so as the fastest and most hands-off method. Still others never want to be interrupted with alerts about new software and dislike the idea of anything downloading behind their backs, or they need to keep an eye on a bandwidth usage cap. You can decide where you stand and set up your Mac accordingly.

To configure App Store updates, follow these steps:

- Open the App Store pane of System Preferences.

- Select or deselect (as you prefer) the Automatically Check for Updates checkbox to enable or disable automatic checking. If it’s selected, you can also select any or all of:

- Download Newly Available Updates in the Background, which not only notifies you of updates but downloads them for you so you can install them without further waiting

- Install App Updates, which installs updates to nonessential apps (that is, those that don’t fall into the next category) automatically in the background

- Install System Data Files and Security Updates, which automatically (without prompting you) installs essential updates—but only after they’ve been available in the Mac App Store for 3 days

- If you’re signed in to the Mac App Store, you can also check or uncheck Automatically Download Apps Purchased on Other Macs, which does exactly what it says.

From now on, your App Store software updates according to your settings without you doing a thing.

Update Non-Mac App Store Software Automatically

Software that doesn’t come from the App Store must use a separate update mechanism. Happily, most modern applications contain some sort of update feature. Unhappily, they don’t all work the same way. Some check for updates every time they’re launched, or on a fixed schedule, while others check only on demand; of those that do check automatically, not all have this feature turned on initially. Some programs can download and install new versions of themselves automatically, while others download a disk image and expect you to open it and run the installer yourself; still others do nothing but open a Web page with links to updates you can download manually.

In an ideal world, updates would require no intervention other than a click or two to confirm that you’re aware of, and approve of, the installation; everything else would happen automagically. Because many applications still lack that level of automation, though, you may have to perform some extra steps.

For now, do the following. Whenever you download and install a new app that doesn’t come from the App Store, check its preferences to see whether there’s an Automatically Check for Updates (or similar) feature. If so, be sure to turn it on! If you can choose how often to check, choose the most frequent option. You might also do the same for your most frequently used apps the next time you open them.

Figure 8: In some applications, such as Transmit (left), the Check for Updates command appears in the application menu—the one with the same name as the application. In others, such as Excel (right), it appears in the Help menu. Wording may also differ between apps.

Work with Rule-based Searches

When you put together a rule-based search—whether it’s a smart folder in the Finder or a smart playlist in iTunes—you let your Mac do the tedious work of identifying items (files, messages, songs, and so on) that are of interest to you. This saves you the time and effort of manually looking through many potential matches for just the right thing. Define the search once, and even if it’s extremely complex, you can repeat it whenever you want with just one click—a classic automation shortcut.

Advanced searches in the Finder, rules in Mail, smart playlists in iTunes, and numerous other environments—including some in third-party apps such as Hazel (see Organize Files with Hazel) and DEVONthink—use a nearly identical interface for finding things based on a series of conditions. Once you’ve learned how to construct one of these rule-based searches in one place, you can recycle that knowledge, with minor variations, in lots of different places, many of which I cover in the next topic (Create and Use Smart Containers).

Before we begin, let me clarify some basic concepts:

- Condition: A condition (sometimes called a criterion) is any piece of information used to identify an item you’re searching for—a word in a filename, a modification date, the sender of an email message, and so on.

- Multiple conditions: A search can have more than one condition, which can be used together or individually.

For example, I can search for all files that both (a) contain the word “book” and (b) were modified within the last week, in which case files that have one of those attributes but not the other wouldn’t show up in such a search. This is known as an All search, because all the conditions must match. Or I can search for files that either contain the word “book” or were modified with the last week, which would match a much larger number of files. This is known as an Any search, because matching any one of the conditions is enough for a positive result.

- Nested conditions: Most rule-based search environments (sadly, not Mail’s rules) have a hidden capability to simulate Boolean (AND/OR/NOT) logic by grouping conditions in Any, All, and None categories. For example, I can search for files that contain Any of Jack or Jill, or All (i.e., both) of Cindy and Sandy, but None of Thomas. In other words, written in Boolean notation it would look like (Jack OR Jill) OR (Cindy AND Sandy) AND NOT Thomas. You can use this technique to devise highly detailed and specific searches.

I’ll use the Finder to illustrate how to set up a rule-based search; remember, you follow the same steps wherever you use this technique.

To perform a rule-based search in the Finder:

- Open any Finder window and press Command-F (for Find). The insertion point jumps to the Search field in the upper-right corner.

- Type some text in that field, such as

book. The window begins filling with all the files on your Mac containing that text. Press Return to search for the text you’ve entered in the contents of any file, or select a narrower category (such as “Name matches: book”) from the pop-up menu that appears.Your search now has its first condition, such as “must contain the text

book,” but you can change that later. - Optionally change the search scope by clicking a folder name, This Mac, All, or another term on the left side of the search bar.

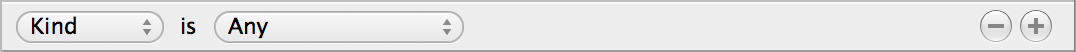

- Click the round plus

button next to the Save button (below the Search field). A new row appears (Figure 9).

button next to the Save button (below the Search field). A new row appears (Figure 9).

Figure 9: When you click the plus button, a new condition row appears.

- From the leftmost pop-up menu in this new row, choose an attribute to search for, such as Kind, Name, or Contents.

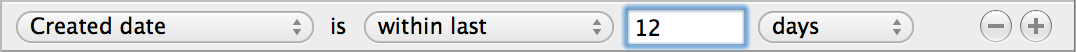

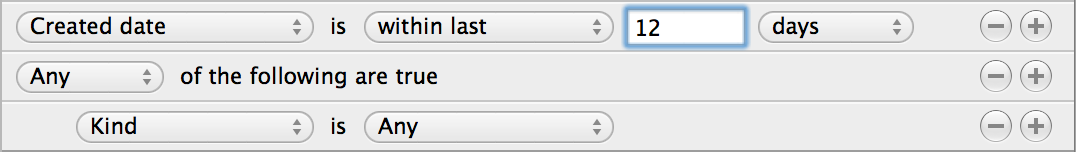

Depending on what attribute you choose, the rest of the row may change. For example, if the attribute is Kind, then the only thing left in the row is a single pop-up menu you can use to pick a kind. But if you choose

[Created Date], you see additional pop-up menus and/or fields (Figure 10), where you can specify, for example,is [Within Last] [12] [Days]. With each choice you make, the rest of the row adjusts accordingly. For example, if you chose[Created Date]followed byis [exactly], then the remainder of the row changes to show only a date field where you can enter a single, specific date. Use the pop-up menus and fields to specify your entire condition as you wish.

Figure 10: As you change search attributes, the rest of the row adjusts.

- To add a second condition that will narrow the search, click the plus

button at the right of the current condition and repeat Step 4.

button at the right of the current condition and repeat Step 4.

- To add a nested condition or group of conditions with its own Any/All/None specification, hold down the Option key and click the ellipsis

button, which replaces the plus button. A new section (Figure 11) appears.

button, which replaces the plus button. A new section (Figure 11) appears.

Figure 11: When you hold down Option and click the ellipsis button, your search options expand considerably.

Choose Any, All, or None from the pop-up menu, fill in the condition just as in Step 5, and optionally add more conditions as in Step 6. Repeat this step (at any level of the rule) to add still more nested conditions.

- Recall from Step 2 that in Finder searches, whatever you initially typed into the Search field remains part of the search. If you want to remove it (to search only for the detailed conditions you added later), select the text in the Search box and press Delete.

That may seem like a lot of steps, but most of them are optional—and once you’ve done a few searches this way, the process will seem both quick and obvious. With this technique under your belt, you can now move on to create smart containers.

Create and Use Smart Containers

The Finder has smart folders. iTunes has smart playlists. Mail has smart mailboxes. iPhoto has smart albums. Contacts has smart groups. I refer to all these (and similar constructions in other apps) collectively as smart containers. Although they may look like folders or mailboxes or whatever, they’re really just saved searches. You construct search rules as described previously, click a button to save the search, and give it a name. Then…hey, presto! Select that smart container whenever you want to display an up-to-date list of all the items that currently match your search.

Here’s a quick overview of how to create and use smart containers in several popular apps:

- Smart folders (Finder): Choose File > New Smart Folder (Command-Option-N), or simply create a search rule as described in the previous topic. When you’re finished, click the Save button in the search bar. Give the smart folder a name, choose a location (the default is

~/Library/Saved Searches), and for maximum convenience, also check Add to Sidebar. Click Save. Thereafter, select that item in a Finder window’s sidebar (or open it wherever you saved it) to show currently matching items. - Smart playlists (iTunes): In iTunes, choose File > New > Smart Playlist (Command-Option-N). Fill out the desired conditions, and optionally select the checkboxes to limit the playlist to a certain number of tracks, match only checked items, or use live updating.

(I recommend live updating, by the way; without it, the smart playlist will always show whatever it happens to match at the time you created it, unless you manually update it by right-clicking or Control-clicking the smart playlist and choosing Update Smart Playlist from the contextual menu. However, live updating may make iTunes slower to respond; if so, you’ll have to decide which annoyance you’d rather endure.) To view and play the items in that playlist, select Playlists (if the sidebar isn’t already visible) and then select the smart playlist.

- Smart mailboxes (Mail): In Mail, choose Mailbox > New Smart Mailbox. Fill in the conditions you want to use, bearing in mind that Mail does not support nested Any/All/None conditions. Optionally select Include Messages from Trash or Include Messages from Sent, as you prefer. Give the smart mailbox a name and click OK. Smart mailboxes appear in their own category in Mail’s sidebar—if it’s not visible, choose View > Show Mailbox List.

- Smart albums (iPhoto): In iPhoto, choose File > New Smart Album. Fill in the your conditions, name the smart album, and click OK. Smart albums appear in the Albums portion of iPhoto’s sidebar. To view all of the photos in a smart album, select it.

- Smart groups (Contacts): In Contacts, choose File > New Smart Group (Command-Option-N). Fill in the conditions that you want to use, name the smart group, and click OK. Smart groups appear with your other groups (if any) in the sidebar. To view all the contacts in a smart group, select it.

If you’re still not sure how a smart container might serve as a useful shortcut, consider these ideas:

- A smart folder that shows all the files created or modified in the preceding calendar year that also have the tag

tax info, regardless of the files’ locations. Handy for tax time! - A smart mailbox that shows you all the messages you sent or received in the last month that mention a certain family member, regardless of where those messages are filed.

- A smart playlist in iTunes that includes all purchased music tracks that you haven’t yet listened to at least five times. Make sure you get to know all your newly purchased music!

- A smart group in Contacts that contains all the other parents of kids in the same class as your child. You can do this by having a smart group

[Note] [Contains] [school]and then putting the word “school” in the Note field of each parent’s contact. As the class composition changes, you can add or remove “school” from records, and the smart group updates automatically.

menu in the toolbar of a Finder window, which also contains a Tags item and the default tags, or right-click (or Control-click) a file and choose Tags or a default tag from the contextual menu.

menu in the toolbar of a Finder window, which also contains a Tags item and the default tags, or right-click (or Control-click) a file and choose Tags or a default tag from the contextual menu. menu or the Bluetooth

menu or the Bluetooth  menu. To create keyboard shortcuts for those commands, you’ll have to

menu. To create keyboard shortcuts for those commands, you’ll have to