In 2011, as the Arab Spring unfolded, a protest emerged in the city of Deraa, Syria, over the arrest of fifteen schoolchildren who had been accused of writing antigovernment graffiti (BBC 2015b). What began as a series of spontaneous protests was met harshly with state repression and has become a full-scale internationalized intrastate war with too many rebel groups to count, many of which transcend borders, spilling over into Iraq and Turkey. The conflict in Syria is truly dynamic. Initially, international efforts, led by the United States, sought to identify and support more moderate elements in their effort against the Assad regime, particularly in light of its use of chemical weapons. As the conflict has continued, however, one rebel faction has emerged and demonstrated great capacity to take territory and threaten both Assad and U.S. interests. The success of the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL, or ISIS, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria) has led to a transition in U.S. policy. As a splinter faction of Al Qaeda that has expanded through terrorist tactics, ISIL has become a primary opponent in the U.S. War on Terror. In addition to employing air strikes, the United States has backed Syrian Kurdish rebels, who are fighting both ISIL and Assad. This has been much to the dismay of Turkey, a U.S. ally that has had its own decades-long battle with its Kurdish population and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), a rebel faction. The actors involved in and around Syria are indeed complex, as are the tactics employed by the various rebel factions involved and their supporters.

Clearly, civil instability continues to pose a serious challenge for the international community. Countries’ seemingly internal struggles, such as those occurring in Syria, threaten to destabilize entire regions or, at the very least, spill into neighboring countries, prompting international response. Efforts to bring about resolution are challenged by resistant governments and emboldened rebels, both of which make tactical decisions repeatedly over time to achieve their goals. As a result of their decisions, and those of outside actors, civil disputes may endure at varying intensities over long periods of time and may become internationalized in the process.

Much of the early literature examining intrastate strife tended to focus on either the onset or the termination of violence using country- or conflict-level characteristics to examine both. Subsequent work continued to employ this approach in order to examine other aspects of this complex problem better. Yet scholars remained challenged by the curious nature of civil disputes. Countries like Myanmar and Indonesia, which are examined in this volume, have experienced many conflicts in different regions throughout their histories. These disputes involved varying numbers of armed factions of diverse capacities that evolved over time. Government efforts to subdue or eradicate factions also changed over time. Previous efforts to understand a set of conflicts like those in Myanmar or Indonesia tended to either collect all of those disputes into one country-level analysis or include all actors in one conflict-level examination. These approaches were suboptimal, as subsuming all of a conflict’s complexity into a single unit ignored the importance and impact of key variations, potentially resulting in misunderstanding the situation.

Because of this, scholars have increasingly moved toward “disaggregating civil war” or “going beyond the state” as the unit of analysis. This involves the “intensive analysis of individual conflicts . . . more systematically” (Cederman and Gleditsch 2009, 489). By taking a more detailed, or microlevel, approach to intrastate disputes, the field has moved away from examining civil war as a single event. Instead, scholars now analyze the wide variety of groups and incidents that comprise civil conflicts and study their reciprocal relations to gain a more comprehensive understanding of what influenced the actors’ capacities. Many in-depth case studies that have taken this approach have improved the understanding of specific conflicts (see, for example, Christia’s analysis of Afghanistan [2012]). To move the field forward in this disaggregated approach, this book presents a theoretical framework through which the dynamic nature of relative group capacities and the resulting tactical decisions can be examined across a range of cases, in a systematic fashion, and over time as conflicts evolve. That framework is then applied to six case studies to illustrate its utility both for gaining better understanding of individual conflicts and for comparing across them.

What becomes clear is that civil conflicts do indeed ebb and flow over time, expanding and contracting through the relationships that emerge. Rebels may work together against a common enemy or may fight among themselves, as seen in Syria. Further, groups may find support from outside actors or end up facing them on the battlefield. Rebel group capacity to wage war is impacted dramatically by these relationship dynamics, which in turn influence, and are influenced by, the tactics they employ.

Analyzing intrastate conflict as a process is not a straightforward endeavor. Identifying groups operating within states is a challenge. Armed opposition groups are often shadowy figures prone to splintering. In addition, a country may experience multiple intrastate conflicts at any one time. At the very least, this complicates the approach of the government and of outside actors, but this may be particularly true when multiple intrastate rebel factions decide to act collectively by forming a coalition in opposition to the government. Conversely, intrastate rivals may begin to fight one another, making the government’s work to suppress opposition easier. Unlike interstate conflict involving two recognized members of the nation-state system, intrastate conflicts involve a nation-state pitted against a difficult-to-define dynamic opponent. Further, once groups are identified, additional challenges emerge when attempting to analyze conflict processes systematically.

Conflict scholars have argued that during the course of civil war, opponents become demonized, constructive interaction disappears, and populations are socialized to the conflict, thus making resolution more difficult (Kriesberg 1998). The polarization of the parties sustains the conflict, extending its duration and increasing its intensity, even as changed circumstances may reduce or limit the relevance of the conflict’s original causes. Examining civil wars or groups in isolation can provide a better understanding of what state- or group-level characteristics are associated with civil war onset or termination. However, it can overlook conflict, tactical, power, and organizational shifts that can move a conflict toward resolution or away from it. In essence, the factors that shape the warring actors and their decisions are missing. Thus, by focusing on the “guts” of a conflict, systematically, across a range of cases, analysis can progress beyond seemingly fixed characteristics to recognize the factors that change over time and the impact those have on tactical decisions.

Further, civil wars or conflicts do not happen in a vacuum. As was the case in the Middle East, events in Tunisia sparked similar events elsewhere. Civil wars spill over as refugees flee across borders (Weiner 1996), rebels seek safe havens in neighboring states, and external actors feel compelled to intervene. Decisions by external actors to engage diplomatically either through offers of mediation or pressure can influence group capacity, moving conflicts in different directions. The same applies to decisions by external actors to intervene militarily, as was seen in the cases of Libya and Syria. These attempts to exert influence by outside actors are themselves the product of a complex set of interactions. Ultimately, external actors aim to bring civil war to an end through various forms of intervention (Regan 2000a). That said, they certainly hope to do so in strategically important ways. In Syria, the United States would like to see ISIL defeated and would prefer Assad be removed. Conversely, Iran would like to see ISIL defeated but considers Assad an ally. Russian military intervention on behalf of Assad seemed to change the power balance entirely. All three interveners have sought to use their influence to bring about resolution in Syria, but under their own terms. For their part, various rebel factions have reacted to these efforts hoping to position themselves opportunistically amid this dynamic power structure. Civil conflicts and wars can be viewed in this regard as a series of actions followed by reactions that collectively determine the tactics rebels will employ to achieve their goals and the resulting impact those decisions will have on the conflict as it unfolds.

Civil wars have been identified as particularly perplexing events, more intense than their interstate counterparts (Miall 1992) with much higher rates of civilian casualties, and are seemingly more difficult to resolve (Licklider 1995). Yet, not all civil wars are intractable and deadly. Whereas some involve heavy civilian casualties and terrorist activity, others are more amenable to negotiation and mediation attempts. The ability to identify the types of factors that influence these tactical decisions among civil war actors would allow policy makers the opportunity to address such conflicts more quickly and effectively. If the answers to such questions lie in the details, that is, the conflict process, then the disaggregated conflict dynamic approach becomes not only informative but necessary. It can be assumed that particular actions and reactions by parties to intrastate conflict may be contentious based on a case or two, but the advantages to studying such moves over a larger set of cases in a more systematic fashion avoids the danger of assuming, particularly when the stakes appear to be very high.

To understand the tactical decisions made by civil war actors, a theoretical framework employing a systematic, disaggregated look at civil conflict has been developed. This was done by integrating previously disparate theoretical arguments that focused on specific aspects of intrastate strife into a cogent, interactive framework. The focus of this book is on the dynamic nature of civil wars, their actors, their capacity, and the conflict environment, all of which are thought to influence how rebels will attempt to achieve their goals. The goal of the book is to take a relatively comprehensive approach to examining the evolving nature of violence in intrastate conflicts and the actors involved by focusing on the conflict context, group and government capacity, and actor goals. To achieve this goal, the theoretical framework presented demonstrates how these variables influence tactical decisions, which subsequently impact the decisions of others. Two major undertakings were necessary to make this project possible.

First, theoretical arguments regarding the factors thought to influence how rebel factions and their government work to achieve their goals were examined and analyzed. Both static and dynamic characteristics of the conflicts are included in the study. Each conflict occurs in its own unique environment. The terrain of the country, its historical context, and the nature of the groups engaged are considered part of this environment. These factors are identified as static, meaning that they change only minimally over the duration of the belligerent relationship. Each can have an influence on the tactics selected by both government and its opposition and, therefore, on the trajectory any conflict may experience.

The nature of the conflict environment, although influential, is just one piece of the puzzle. Dynamic variables are also examined. These are aspects of the conflicts that could be expected to undergo significant changes in response to activities of the state and rebel groups. The most important dynamic variable is the relative capacity of the actors involved. Capacity consists of the size, cohesion, and leadership of each side, the degree to which it enjoys popular support, and the quality and quantity of weaponry available. Capacity is also influenced by the previous tactics in which each side engaged, particularly the success or failure of those actions. It is the relative capacity of the factions involved and their government that is important. The case studies presented confirm that the actions of warring actors are dramatically influenced by not only their relative capacity but also their perception of it. If one actor thought the other was about to gain or lose capacity, it could be enough to bring about calls for peace or the escalation of violence.

Tactical decisions and conflict trajectory are also thought to be influenced by one final dynamic variable, which is the overarching group goal. This may include desires for representation, policy/regime change, autonomy, or secession. Group demands can change over time, starting at any one of the goals and moving among them, depending on their situation and their experience over the course of the conflict. A government can have similar goals in that it may choose any of these as an acceptable or unacceptable solution to the problem with a group and will act accordingly. In other words, the government may prefer autonomy for a region rather than secession, which governments tend to do. Tactical decisions flow from these static and dynamic variables, as actors choose their actions for the future based on the success and failures of past and current decisions. Tactical options may include engaging in dialogue, appeals for international assistance, guerrilla warfare, or terrorism. These decisions or actions, along with the responses of other conflict actors, ultimately determine the direction or trajectory of a conflict.

International intervention, of course, is very important to the patterns of violence experienced by states in conflict. Intergovernmental organizations, nongovernment organizations, states, and individuals are examples of the types of actors that may choose or be invited to intervene. Among the relevant factors for this characteristic of conflicts are the motives of the intervener, whether the intervener seeks to change the behavior of the group or the state, the intervening power of the actor, and whether the intervention comes in the form of financial influence, diplomatic involvement, or military support. The addition of a third party into a conflict will impact group and government capacity, which varies depending on the type and direction of intervention. Capacity influences both tactical decisions and conflict trajectory.

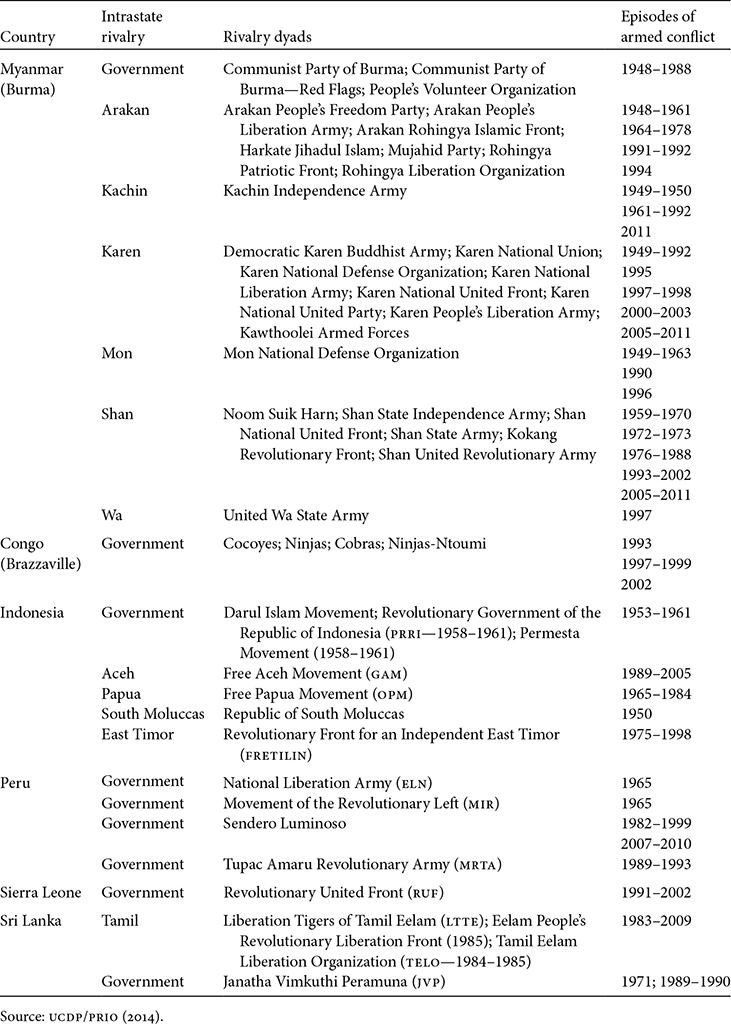

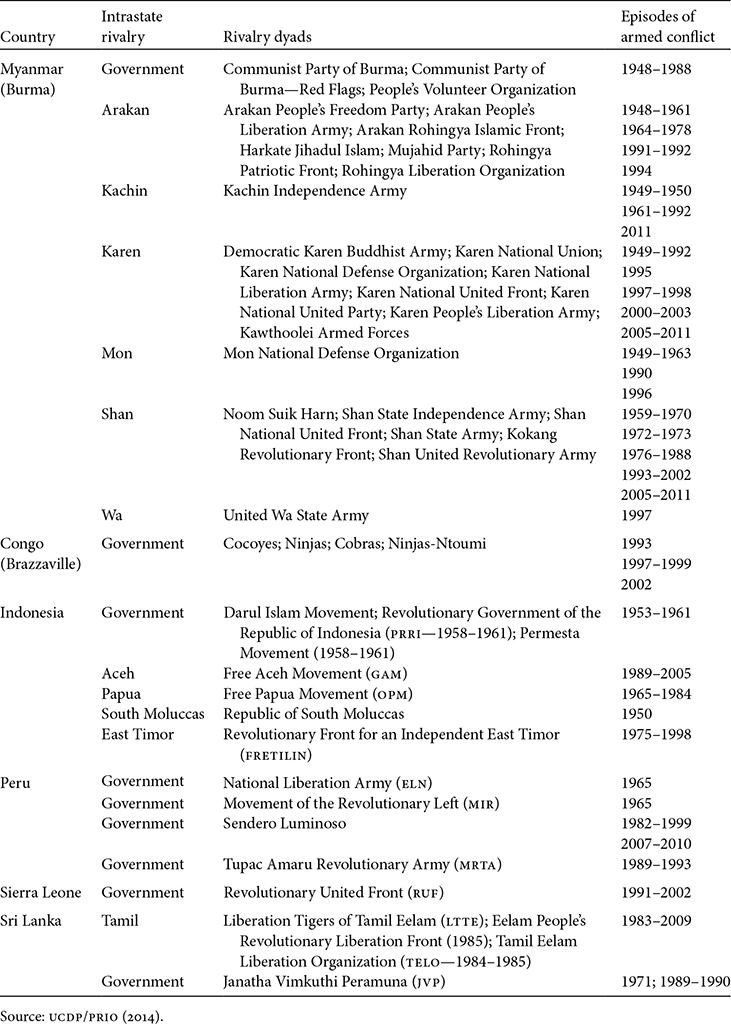

The book proceeds with an intensive examination of six countries that have experienced intrastate conflict. The theoretical arguments proposed in chapter 1 are applied in order to gain an improved understanding of each case. In an effort to examine the complex nature of conflict as it changes over time and interacts across other actors, the project moves away from the typical approach of examining dyads (the state versus one rival) in conflict. Instead, the case studies examine a number of conflicts and conflict actors for the state during the period under investigation, which was from either 1945 or the date of independence until 2011.

Conflict has been distinguished from a war consistent with the work of civil conflict scholars. Conflict occurs between a recognized member of the nation-state system and an armed nonstate actor operating within its borders. Violent interactions between those actors must meet a minimum battle death threshold of twenty-five in a given year to be considered a civil conflict (Gleditsch et al. 2002). A civil conflict escalates to the level of civil war when the same actors reach a battle death threshold of one thousand in a given year (Small and Singer 1982; Gleditsch et al. 2002).1 Some of the conflicts examined have evolved over time through their persistence into what DeRouen and Bercovitch (2008) have termed internal enduring rivalries, which can appear to be intractable in nature. As a result, intrastate conflicts that are episodic in nature, or those that are short bouts of violence that do not repeat, can be distinguished from those that endure involving multiple armed events over time. Further, in some cases, the repeated nature of the disputes involves political rivalries, or the same elites entangled in repeated interactions within the conflict itself. For clarity, political rivalry (i.e., conflicts involving elite-level actors) is distinguished from enduring rivalry (intrastate conflicts that have endured over time).

The complexity of the cases, as examined here in the number of rebel factions rivaling the state, ranges from one competitor in the case of Sierra Leone to as many as nine in the case of Myanmar. Governments’ interactions with groups influence their responses to other groups and their future actions. When a government is facing multiple factions or conflicts at the same time, its ability to fight any one of them may be constrained. A government may also feel it has to repress one faction to demonstrate to other potential competitors that rebellion is costly. In other words, to understand conflict progression, and ultimately termination, the importance of decisions made in the midst of conflict, the history those decisions create, and group complexity that drives them must all be understood. This approach results in conclusions about how patterns of violence manifested in the six countries and the ability to make comparisons across the cases, which include Sierra Leone, Republic of the Congo (Brazzaville), Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Indonesia, and Peru. Each case was selected to illustrate important aspects of the theoretical expectations presented in chapter 1 across regions and conflicts.

The country of Sierra Leone, discussed in chapter 2, has been challenged by ineffective governance as it struggled to transition from a British colony to a functioning nation-state. Overcoming the legacy of this colonial history has proved difficult. The ethnically diverse nation has been ravaged by war as political elites vie for power and control over the country’s resources, in particular its alluvial diamond fields. This case analysis brings into the discussion the role of external actors as facilitators of conflict (particularly Liberia’s Charles Taylor) and as resolvers (including the British, the United Nations, and West Africa’s ECOMOG). One interesting aspect of the case is the decision by the state to hire private military corporations in its efforts to boost its capacity versus the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) rebel faction. Unlike other cases, Sierra Leone has only one conflict and it was relatively short-lived, but the country experienced a significant amount of governmental change in the form of coups d’état. The shifting nature of the government pitted against the externally backed RUF is explored in detail, helping to illustrate the impact of such changes on the course of conflict and its resolution.

The Republic of the Congo also had a rather short conflict history. Although the country has experienced multiple intrastate conflicts, they have been episodic in nature involving political rivals, flaring up briefly only to end in a negotiated outcome. Examining this case in light of the theoretical model proposed in chapter 1 provides a better understanding of the influence that goals have on tactical decisions made by rival actors. Each of the episodes of violence occurring in the Congo was a manifestation of elite political divisions defined almost entirely by the players that led them. Of course, the histories of these rivalries became intertwined as well with rivals merging as loyalties shifted. The analysis presented in chapter 3 makes it clear that group goals are indeed a force driving conflict trajectories.

The long-term civil war in Sri Lanka has spawned one of the most unique and innovative rebel organizations of modern history, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Elam (LTTE), which is discussed in chapter 4. The LTTE developed a primitive air force and navy, as well as spearheaded the use of suicide bombings as a tactic. The group had one of the most sophisticated and developed organizational structures of the rebellions examined. Despite these advantages, the government’s victory in 2009 may indicate that the group has been defeated. However, while the conflict with the LTTE was the dominant conflict in the country, it was not the only one. The government had to face other Tamil and Sinhala nationalist groups as well, which challenged its capacity to respond. In some cases the LTTE fought both other Tamil nationalist groups and the government at the same time. This chapter examines the factors that influenced the group’s strategic decisions through time as well as the impact of international interventions and negotiations on the group and the Sri Lankan government. One of the most important points this case illustrates is the potential importance a charismatic leader, in this case Velupillai Prabhakaran, can have on conflict dynamics.

Myanmar, formerly Burma, represents the most complex of all the cases examined in this book and is presented in chapter 5. This case provides an excellent illustration of the fact that intrastate conflicts do not occur in isolation. The country has experienced over nine different conflicts of varying types. Their histories are frequently intertwined as groups coalesce at times, effectively increasing their capacity relative to the government even in the presence of competing goals. At other times, factions of one conflict have also taken up arms alongside the government, pitted against another of the government’s opponents, diminishing the capacity of one while bolstering the other. The Myanmar government has been forced to wage war in several parts of the country through much of its history, facing multiple opponents and a frequently hostile set of external actors. Examining the enduring nature of these conflicts and how they have unfolded over time as tactics have shifted provides a unique insight into how multiple conflict trajectories are formed in the same political space.

Indonesia, the subject of chapter 6, is a truly fascinating case for the study of intrastate conflict. In the immediate post-independence period, the country experienced civil unrest from a variety of different groups that sought changes ranging from more representation and differing policies to secession. Each of these conflicts was resolved in a different way by the government, and each had unique factors that impacted strategy selection, evolution of the conflict, and interventions. Some of the conflicts were resolved relatively quickly, while others have persisted. The diverse conflicts evolved along unique paths and demonstrate the theoretical arguments of this book in different ways. The Indonesian case provides an analysis of a Southeast Asian country with a large number of groups in conflict with each other and the government. It is also a case where the success of international intervention varied based on the characteristics of the specific conflict and its actors. Indonesia has had one ideological and four identity-based conflicts since independence. The country’s archipelagic nature increased the importance that the geography of the country had for the conflict dynamics.

Peru has experienced four distinct intrastate conflicts in the post–World War II time period and is discussed in chapter 7. Each of these conflicts shared the same ideological goal of seeking to move the country toward the left politically. The conflicts diverge, however, in the rebel groups’ ability to survive, in the tactical decisions they made, and, not surprisingly, in their capacities relative to the government. Two Peruvian disputes are episodic, whereas two others are more enduring. The case of Peru demonstrates that when actors make tactical decisions that best match their capabilities, they can flourish. In even the enduring rivalries, however, tactical decisions that resulted in diminished group capacity are evident. The case demonstrates that conflict trajectories are indeed formed through a set of actions and reactions over time.

The final chapter reflects on the importance of both static and dynamic factors in influencing conflict trajectory. Each of the six countries and many conflicts examined provide insight into tactical decisions that actors make in the midst of conflict, how those decisions are reciprocated, and how these interactions influence future activities. The lessons learned through these in-depth case analyses are presented as concluding thoughts on the conflict process. Implications of these findings for the direction of future research on the topic of civil conflict, war, and rivalry are also provided.

TABLE I.1 Rivalries and Groups Examined in This Book