GROUP 4, “Ethical Principles,” consists of twelve chapters that discuss typically Confucian themes such as humaneness, righteousness, wisdom, the rectification of names, and filial piety. With the exception of the last three chapters, which are closely associated with the Classic of Filial Piety, they develop these ethical principles in conjunction with the Spring and Autumn, demonstrating how that text, often through specific illustrations, supports and illuminates them. These chapters appear to have been grouped together by the Chunqiu fanlu’s compiler or perhaps by an earlier editor whose work the compiler adopted on the basis of content (Confucian ethical principles) and classical grounding (Spring and Autumn, Classic of Filial Piety).

GROUP 4: ETHICAL PRINCIPLES, CHAPTERS 29–42

29. 仁義法 Ren yi fa Standards of Humaneness and Righteousness

30. 必仁且智 Bi ren qie zhi The Necessity of [Being] Humane and Wise

31. 身之養莫重於義 Shen zhi yang mo zhong yu yi For Nurturing the Self, Nothing Is More Important Than Righteous Principles

32. 對膠西 [i.e., 江都] 王越大夫不得為仁 Dui Jiaoxi [Jiangdu] Wang: Yue dafu bu de wei ren An Official Response to the King of Jiangdu: The Great Officers of Yue Cannot Be Considered Humane

33. 觀德 Guan de Observing Virtue

34. 奉本 Feng ben Serving the Root

35. 深察名號 Shen cha ming hao Deeply Examine Names and Designations

36.

實性 Shi xing Substantiating Human Nature

37. 諸侯 Zhuhou The Lords of the Land

38. 五行對 Wuxing dui An Official Response Regarding the Five Phases

39. [Title and text are no longer extant]

40. [Title and text are no longer extant]

41. 為人者天 Wei ren zhe tian Heaven, the Maker of Humankind

42. 五行之義 Wuxing zhi yi The Meaning of the Five Phases

Description of Individual Chapters

Chapter 29, “Standards of Humaneness and Righteousness,” consists of a single essay that discusses how the

Spring and Autumn uses these central virtues of the Confucian tradition to bring order to the self and society at large: “What the

Spring and Autumn brings order to is others and the self. The means by which it brings order to others and the self is humaneness and righteousness. It employs humaneness to pacify others and righteousness to correct the self.”

1 But in contemporary society, people pervert and misapply these two virtues, using humaneness to enrich themselves and righteousness to oppress others. This, the essay argues, is the main reason why the

Spring and Autumn devotes so much attention to clarifying the meaning and application of these virtues. It does so by setting clear standards that demonstrate that humaneness “lies in loving others, not in loving the self” and that “righteousness lies in correcting the self, not in correcting others.”

2 Moreover, the ability to censure others does not qualify as righteousness, and the ability to love oneself does not qualify as humaneness. Several examples demonstrate this point: Duke Ling of Jin was filled with self-love but failed to love others; in contrast, Duke Zhuang was an exemplar of humaneness, for he worried over the most distant in the land. King Ling of Chu may have punished the rebels of Chen and Cai, but he failed to rectify his own person, and thus the

Spring and Autumn did not consider him a standard of righteousness. These distinctions are critical to ordering the self and society at large. Thus, the essay concludes, the ruler’s self-rectification is paramount. This conclusion explains the methodology of praise and blame in the

Spring and Autumn: “The

Spring and Autumn censures the faults of those above and pities the hardships of those below. It does not call attention to minor transgressions external [to the ruler], but when they reside in [the ruler] himself, it records and condemns them.”

3 The ruler must ponder these standards of humaneness and righteousness. If not, even if he possesses the Way of the Sages, he will fail to understand the meaning of the

Spring and Autumn.

Chapter 30, “The Necessity of [Being] Humane and Wise,” consists of two unrelated sections. Section 30.1 is an essay that defines humaneness and wisdom and their relationship to each other. The opening paragraph shares interesting parallels with section 9.30 of the

Huainanzi’s

chapter 9, “The Ruler’s Techniques,” although the

Huainanzi passage describes humaneness and wisdom differently: “In human nature nothing is more valuable than Humaneness; nothing is more urgently needed than Wisdom. Humaneness is used as the basic stuff; Wisdom is used to carry things out.”

4 In contrast,

chapter 30 of the

Chunqiu fanlu states: “Humaneness is the means to love all human beings, and wisdom is the means to rid them of harm.”

5 Neither humaneness nor wisdom is identified with the basic substance of a human being, but both are means or methods to improve the human community. Such an approach is consistent with Dong Zhongshu’s views of human nature expressed in his memorials that, for example, define human nature as “the unadorned character of the basic substance,” a topic we will turn to in greater detail later. The remaining discussion amplifies these initial claims by describing the various attributes associated with humaneness and wisdom.

The brief passage that constitutes section 30.2 is about natural disasters and bizarre events initiated by Heaven. It characterizes natural disasters as Heaven’s warnings and bizarre events as Heaven’s threats and maintains that natural disasters always precede strange events and are less ominous. It interprets both as confirmation of Heaven’s humane concern and argues that by these means it is possible to observe Heaven’s will. Although natural disasters and bizarre events should be feared, they should not be despised, as they express Heaven’s desire to rescue the ruler from his errors and save him from doing wrong. Thus, the passage concludes, “If a sagely ruler or worthy lord still delights in receiving the reproofs of his loyal ministers, then how much more should they delight in receiving Heaven’s warnings.”

6One commentator has suggested that section 30.2 would be more appropriate as part of

chapter 15, “Two Starting Points,” which also discusses anomalies in conjunction with the

Spring and Autumn and in relation to the ruler’s transgressions.

7 This is an attractive suggestion, as the passage clearly seems out of place here and bears little relation to the discussion of humaneness and wisdom in section 30.1.

Chapter 31, “For Nurturing the Self, Nothing Is More Important Than Righteous Principles,” develops an important distinction concerning self-cultivation that Mencius made some two centuries earlier, between the greater aspects of personhood (

dati 大體) and the lesser aspects of personhood (

xiaoti 小體):

Gongduzi asked: “We all are men. Why, then, are some great men while others are small men?” Mencius replied: “Those who follow the greater aspects of their person become great men; those who follow the lesser aspects of their person become small men.” Gongduzi then asked: “How is it that some follow the greater aspects of their person while others follow the lesser aspects of their person?” Mencius replied: “The faculties of hearing and sight are unable to think and so can be misled by external things. When one thing interacts with another, it leads one another astray, that’s all. The faculty of the mind is thought. If it does think, it will find the answer. If it does not think, it will not find the answer. This is what Heaven has bestowed on us. If you seek to establish yourself relying on the greater aspects of your person, then the lesser aspects of your person will not displace them. This is what makes a person a great man and nothing more.”

8

Taking this famous dictum as its starting point,

chapter 31 affirms that material benefits and righteous principles equally are gifts from Heaven but that their purposes are different: “[M]aterial benefits to nourish the body; righteous principles to nourish the heart.”

9 In addition, righteous principles are more important than material benefits, as borne out in the following argument: “When people amply possess righteous principles but sorely lack material benefits, though poor and humble, they may still bring honor to their conduct, thereby cherishing their persons and rejoicing in life.”

10 In contrast, “When people amply possess material benefits but utterly lack righteous principles, though exceedingly wealthy, they are insulted and despised. If their misdeeds are excessive, their misfortunes are serious. If they are not executed for their crimes, they [nevertheless] are struck down by an early death. They can neither rejoice in life nor live out their years.”

11 Nonetheless, people typically forget this fact. Forgetting righteous principles, they lust after material benefits. Disregarding inherent principles and following hateful ways, they not only harm themselves but endanger their families as well. In contrast, the sage perfectly embodies righteous principles, manifesting them in his virtuous conduct and instructing the people through his personal example. Through his personification of righteous principles, he can move others:

Having moved others, he can transform them. Having transformed them, he can glorify their conduct. Having transformed and glorified their conduct, laws are not disobeyed. When laws are not disobeyed, punishments are not employed. When punishments are not employed, the virtue of Yao and Shun is achieved. This is the Way of Great Governance. The former sages transmitted and received it in succession. Thus Confucius said: “Who can go out without using the door? Why, then, does no one follow the Way?”

12

The essay concludes that this is the Way of Great Governance. If the ruler fails to follow this course of action, even though he may institute severe and harsh punishments, it will serve only to harm the people he rules and compromise his power and positional advantage.

Chapter 32, “An Official Response to the King of Jiangdu: The Great Officers of Yue Cannot Be Considered Humane,” also addresses the subject of humaneness. In this case, the topic is raised during an exchange between the imperial kinsman Liu Fei, who reigned as King Yi of Jiangdu, and Dong Zhongshu, who at the time was serving as the kingdom’s administrator. (A second recension of the official document recording the exchange is preserved in the

Han shu’s “Biography of Dong Zhongshu,” affirming its close association with Dong. The original chapter title indicates that this response was to the king of Jiaoxi, but we follow

Han shu 56 in assigning it to the court of Jiangdu.) The dialogue between the king and the administrator reflects the unsettled political situation of Emperor Wu’s reign. Part of the imperial realm was under the emperor’s direct control, and part was divided into kingdoms ruled by imperial relatives. On several occasions, some of these neofeudal lords rebelled against the imperial throne, and the empire also had to contend with incursions of the nomadic Xiongnu, who from time to time attacked across the northern frontier from their homeland in the distant steppes. Some of the regional kings and military officials who took up arms to defend the emperor may have seen themselves as fitting the mold of the hegemons of the Spring and Autumn period, wielding political and military power on behalf of the Son of Heaven. Others may simply have been trying to curry favor with an emperor who was not averse to crushing the neofeudal kingdoms and incorporating their territory into the imperial domain.

Chapter 32 provides testimony to the relevance and appeal of the hegemonic system for at least some of the Han regional kings. The king of Jiangdu initiates a dialogue concerning one of the five famous hegemons of the Spring and Autumn period,

13 the king of Yue, and his worthy ministers. The king of Jiangdu himself was a devoted military man who had rallied to defend the imperial throne during the Rebellion of the Seven Kingdoms in 154

B.C.E. and who at the time was contemplating taking up arms once again to fight the Xiongnu. Querying Dong Zhongshu, who had already established his reputation as an incorruptible scholar, the king asks a leading question: Were King Goujian of Yue and his two most trusted ministers exemplars of humaneness, even though they went to war to defend their ruler? Clearly the king expected an affirmative answer, one that by implication would endorse his own credentials for humaneness. Typical of his uncompromising character, Dong was unwilling to cede the point. His answer was unambivalent: the kingdom of Yue lacked even one humane man, he said, much less three. Why so? Dong explained that the hegemons relied on treachery and force rather than humaneness and righteousness: “Compared with other Lords of the Land, the Five Hegemons were worthy; compared with the sages, how can they be considered worthy? They were but coarse stone to polished jade.”

14

Chapter 33, “Observing Virtue,” and

chapter 34, “Serving the Root,” develop the cosmic aspects of virtue and ritual in ways reminiscent of the works of Xunzi.

Chapter 33 begins by situating human virtue in the larger context of cosmic virtue. That is, not only do we form one body with the universe but our virtue derives from Heaven and Earth as well: “Heaven and Earth are the root of the myriad things, the place from which our first ancestors emerged…. The Way of ruler and minister, father and son, and husband and wife derive from Heaven and Earth.”

15 To observe the “vast and limitless” Virtue of Heaven and Earth, the text avers, we need only contemplate how the subtle wording of the

Spring and Autumn ranks all who appear in its pages in accordance with this cosmic virtue. Numerous examples demonstrate this general claim, spelling out the different patterns of notation in the

Spring and Autumn and making explicit their relevance to the virtue of specific actors.

Section 33.3 discusses the rules said to be observed in the Spring and Autumn for referring to foreign peoples and blood relatives. Contact with foreigners apparently is regarded as embarrassing for the Sinitic states, and therefore the Spring and Autumn downplays such instances. Conversely, the chapter’s author gives special attention to blood relations, citing examples in which the Spring and Autumn sets aside its usual terminology because of blood ties, literally “sharing the same surname.” During the Han, these claims may have been especially relevant to foreign relations, on the one hand, and rank, precedence, and subordination in the imperial Liu clan, on the other.

The opening section of

chapter 34, “Serving the Root,” cites the most important attributes of the rites: they “connect Heaven and Earth; embody yin and yang; [and] are punctilious about host and guest.”

16 Heaven, Earth, and humanity each have quintessential counterparts reflecting their abiding virtue: the sun and moon are the quintessence of Heaven; mountains are the quintessence of Earth; and the Son of Heaven is the quintessence of humanity. But what promises to be a compelling essay on ritual and its relation to the virtues of the three realms quickly breaks down. The remaining four sections of this chapter are disparate fragments brought together in patchwork fashion, perhaps because of their references to the

Spring and Autumn.

Chapter 35, “Deeply Examine Names and Designations,” and the closely related

chapter 36, “Substantiating Human Nature,” develop a position on human nature close to that of Xunzi. Indeed, these two chapters share much with the

Xunzi, particularly the ideas set forth in

Xunzi 22, “On the Correct Use of Names,” and 23, “[Human] Nature Is Bad.” Like the

Xunzi, these two chapters of the

Chunqiu fanlu define human nature as what is inborn and natural, and contend that human nature cannot be considered good because goodness is a virtue acquired through education. They also develop Xunzi’s ideas about language in three important ways: they emphasize the cosmic origins of language, they associate his rectification of names with the

Spring and Autumn, and they use the rectification of names and draw on the

Spring and Autumn to develop a position on the inherent qualities of human nature.

Chapters 35 and

36 share many parallel passages and arguments, which has led some scholars to conclude that

chapter 36 is an abbreviated version or a synopsis of

chapter 35 and thus is the later of the two essays. We believe the reverse to be more likely: the shorter

chapter 36 is actually the earlier of the two essays on human nature, and

chapter 35 amplifies and develops it. Not only does

chapter 35 contain passages that also appear in

chapter 36, but

chapter 35 also develops these positions in novel ways. The rectification of names, for example, is given a cosmological basis in

chapter 35, and nature and emotions are related to yin and yang only in

chapter 35. Since the arguments of

chapter 36 are encompassed by

chapter 35, our discussion of

chapter 35 will introduce both chapters.

Chapter 35, “Deeply Examine Names and Designations,” has four sections. Each addresses the rectification of names but for different purposes. Section 35.1 introduces the rectification of names as the starting point of social order and posits that the rectification of names itself originates with Heaven and Earth. Thus, the argument continues, when the sages created language, they were simply imitating what was already inherent in the patterns of the cosmos itself. Therefore, names and designations are ultimately “the means by which the sage communicates Heaven’s intentions.” The sage does so by availing himself of the two essential categories of language, names and designations, which serve complementary but distinct functions: names denominate, and designations generalize. As the numerous examples that follow demonstrate, all things in the universe possess an inherent name and designation. Thus, this short essay concludes, “For this reason, when each affair complies with its name and each name complies with Heaven, the realms of Heaven and humankind are united and become one.”

17 This is another manifestation of the Way of Virtue.

Section 35.2 continues this in-depth examination of names and designations, using orthographic (visual) and aural puns to explore the range of meanings connoted by two related terms:

wang 王 (king) and

jun 君 (lord). By analyzing these two terms, the section leads the reader to understand how, in the

Spring and Autumn’s theory of language, they are imbued with inherent virtue. Section 35.3 returns to the sage’s use of names, emphasizing that the sage employs names to authenticate things—that is, to distinguish what is so from what is not so. This claim concerning the rectification of names serves as a preamble to the heart of the essay, a discussion of human nature. The author believes that the question of nature is mired in confusion, which he proposes to clarify. He does so in section 35.3 (and an analogous paragraph in

chapter 36) through a critique of Mencius, who asserted that human nature is inherently good because it contains the starting points of virtue. Even though, like Mencius, the author of this critique associates the word “nature” (

xing 性) with “what is inborn” (

sheng 生), his understanding of this basic stuff (

zhi 質), which constitutes a person’s nature, is much closer to the position adopted by Xunzi. Human nature, as with Xunzi, is the natural and uncultivated stuff with which one is born. Furthermore, goodness, as with Xunzi, is achieved through education. Therefore, says the author of section 35.3, to identify human nature with goodness is to misunderstand and misrepresent its reality: “If we search for the basic substance of ‘nature’ in the name ‘good,’ is it capable of hitting the mark?”

18What, then, are the spontaneous qualities that one possesses at birth and that define the basic substance called “nature”? To answer this question, the author analyzes the closely related term

xin 心, which means both “heart” and “mind,” arguing that the heart/mind acts to restrain human nature. If nature were inherently good, would it require such restraint? The word “body” is thought to be closely related to Heaven. Like Heaven, which possesses two aspects of

qi manifested in yin and yang, the body possesses two aspects of nature manifested as greed and humaneness. Moreover, just as Heaven places controls on yin and yang, a person must restrain his emotions and desires. This assertion emphasizes Heaven’s control of yin (which, as we will see in

group 5, “Yin-Yang Principles,” is strongly identified with negative qualities) and therefore a person’s need to restrain his greed and other negative mental states.

Accordingly, rather than viewing education as Mencius envisioned it—as a process of developing the inchoate sprouts of goodness that are present at birth as part of human nature—goodness is presented here as a human achievement, not as the development of an inherent human quality. This is shown in the final term examined in the essay, the designation min 民 (common people), which, the author asserts, is derived from the term mian 眠 (eyes closed). Our eyes, the author continues, are closed in sleep and only when we awaken can we see. Analogously, the common people are ignorant and depraved and only when they are given an education can they become good.

In a slight semantic shift, the essay next associates the sleeping person with the nature (

xing) and the emotions (

qing 情) mutually conferred by Heaven and Earth. Humans partake of both nature and emotions. Those who claim that human nature is good do not account for the emotions: “Therefore the sage [Confucius] never referred to the nature as good because it would have violated the [meaning of the] name. A person has a nature and emotions, just as Heaven has yin and yang. To speak of one’s basic substance without mentioning one’s emotions is like speaking of Heaven’s yang without mentioning its yin.”

19 The essay concludes by pointing out that its discussion of human nature does not refer to the highest or the lowest type of person but to average people. Like an egg that awaits incubation to become a chicken and a silk cocoon that awaits unwinding and spinning to become silk thread, ordinary people must await education to become good: “The people receive from Heaven a nature that is not yet capable of being good, and they humbly receive from the king the education that will complete their nature.”

20Section 35.4 refutes the Mencian position once again, but from a slightly different perspective. This last section consists of an exchange (real or imagined?) between two people. The exchange is initiated by the phrase “[Suppose] someone says,” and then this unnamed “someone” raises the notion of “sprouts of goodness.” A long discussion follows, introduced by the words “[I] would say in response.” The respondent attempts to settle the debate as to whether human nature is inherently good by turning to the subject of “goodness” as a standard in the teachings of Mencius and Confucius. He maintains that Mencius and Confucius differed radically in the ideals of goodness they espoused and that Mencius was wrong and Confucius was right. Mencius’s position is described as follows: “[Human] nature contains the sprouts of goodness. Children love their fathers and mothers so are better than birds and beasts. In this sense, [their nature] is called good. This is Mencius’s notion of goodness.”

21 In contrast, Confucius’s position is described as having a much more rigorous idea of goodness:

Therefore Confucius said, “A good man is not mine to see. If I saw a man who possessed constancy, I would be content….”

22 If simply activating the sprouts of goodness that make one better than birds and beasts may be called goodness, why did Confucius maintain that he never saw such a person? … The nature of the myriad commoners is better than that of birds and beasts but it cannot be called good.

23

Mencius’s notion of goodness embodied the lowest ideal of the term, and Confucius’s represented the highest. What Confucius called goodness “was not easy to match,” whereas what Mencius called goodness was simply a matter of “being better than the birds and the beasts.” The passage concludes:

Mencius looked below to find the substance [of goodness] in comparison with what birds and beasts do and therefore said that nature is inherently good. I look above to find the substance [of goodness] in comparison to what the sages did, and therefore I say that nature is not yet good. Such a standard of goodness surpasses nature, just as the sages surpass this standard of goodness. The

Spring and Autumn attaches importance to the origins of things. Therefore it is meticulous with regard to the correct use of names. If the name is not traced to its beginning, how can you say whether the nature is not yet good or inherently good?

24

The stance of

chapter 36 on nature and goodness—and so, by extension, the stance of the entire group—is to reject the Mencian position in favor of more stringent views resembling those of Xunzi.

The very brief

chapter 37, “The Lords of the Land,” states that great sages of antiquity observed Heaven’s cycles because they understood that although Heaven does not speak, its intentions to benefit and sustain the people are evident in those cycles. Therefore, when the sages faced south to rule the world, they invariably brought universal benefit to their people. Because what they could see and what they could hear were limited, they parceled out lands to be ruled by overlords who were established as their eyes and ears. Using a play on words, the essay defines “Lords of the Land” (

zhuhou 諸侯) as “numerous servants” (

zhuhou 諸候), making clear that although the king delegates power to the lords, the proper hierarchical relationship between ruler and nobles must be respected. Despite being projected back into antiquity, the relevance of this definition to the neofeudal kings of the Han is obvious: they exist only to serve the Son of Heaven. This was a timely message in the era of Emperors Jing and Wu. Faced with interminable problems with the regional kings during the first century or so of Western Han rule, the emperors would very likely have welcomed an ideological justification for doing away with them.

The last three extant chapters in this group—

chapter 38, “An Official Response Regarding the Five Phases”;

chapter 41, “Heaven, the Maker of Humankind”; and

chapter 42, “The Meaning of the Five Phases”—all discuss the virtue of filial piety.

Chapters 38 and

42 link filial piety to the Mutual Production Sequence of the Five Phases, and

chapter 41 quotes extensively from the

Classic of Filial Piety.

25Section 38.1 purports to be an official exchange between “Master Dong of Wencheng” and “King Xian of Hejian.” As the chapter title, “An Official Response Regarding the Five Phases,” implies, this chapter is ostensibly (though not necessarily) an official account of the exchange between the king and the master, duly reported to the central court. Section 38.2, a brief interpretive passage on the

Classic of Filial Piety, very likely migrated from

chapter 41 to

chapter 38 at some point during the long transmission of the text. Because it shares many formal features with the materials collected in the second part of

chapter 41, we will discuss it in conjunction with that chapter.

In the opening lines of section 38.1, King Xian of Hejian initiates a dialogue with “Master Dong” (possibly a fictional version of Dong Zhongshu) by requesting an explication of a passage from the

Classic of Filial Piety. The passage defines filial piety as “Heaven’s Warp and Earth’s Righteousness.” What does this mean?

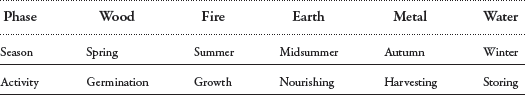

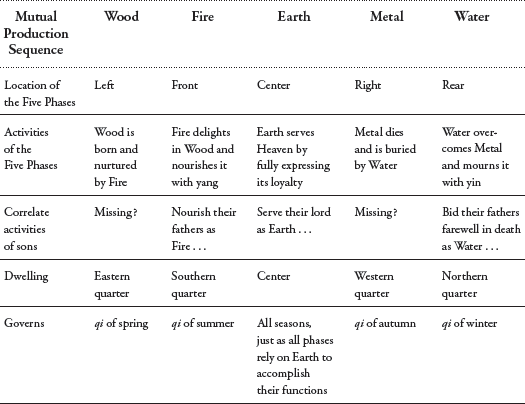

26 Master Dong responds in two steps. He explains Heaven’s Warp in terms of the Mutual Production Sequence of the Five Phases, which he also associates with the five seasons and their five characteristic activities, to yield the correlations presented in

table 1. Although the Five Phases are said to exemplify the five forms of human conduct, filial piety is the sole virtue discussed in the first part of Master Dong’s response, consistent with the question he was asked. In the Mutual Production Sequence, each phase engenders the next; that is, the next phase receives what the previous one has engendered. Master Dong interprets this as a cosmic template for the father–son relationship. In this reading, filial piety exemplifies the Way of Heaven because each phase in turn is the cosmic expression of the “father conferring and the son receiving.”

In the second part of his response, Master Dong explains Earth’s righteousness first as an analogy to the weather: even though Earth is the source of wind and rain, it confers the merit for these achievements on Heaven, as exemplified in the expressions “Heavenly rain” and “Heavenly wind.” Earth’s service to Heaven, characterized by “diligence and hard work,” in turn provides the cosmic template for “great loyalty,” the proper service offered by subordinates to their superiors.

Master Dong’s response then turns to Five-Phase analogies, and he reiterates, again in accordance with the Mutual Production Sequence, that Earth is the son of Fire. But this part of the response emphasizes the special status of Earth in relation to the Five Phases and its subordinate status to Heaven: “Thus subordinates serve superiors, just as Earth serves Heaven…. Earth is the son of Fire. Of the Five Phases, none is more noble than Earth.”

27 But despite Earth’s special status, it plays only a minor role in the seasons (which, in the second part of the essay, consist of only the four conventional seasons, in contrast to the earlier five): “Earth’s relation to the four seasons is that there is nothing that it commands, and it does not share in the accomplishments and reputation of Fire.”

28 This last enigmatic statement is explained in a later chapter,

29 which makes clear that nothing can impede Fire’s potent yang:

[The phase] Earth resembles “earth” [meaning “soil”]. Earth rules righteousness [as Heaven rules humaneness]…. Although [the phase] Earth dwells in the center, it also rules for seventy-two days of the year, helping Fire blend, harmonize, nourish, and grow. Nevertheless, it is not named as having done such things, and all the achievement is ascribed to Fire. Fire obtains it and thereby flourishes. [Earth’s] not daring to take a share of the merit from its father is the ultimate in the perfection of filial piety. Thus both the conduct of the filial son and the righteousness of the loyal minister are modeled on Earth. Earth serves Heaven just as the subordinate serves the superior.

30

Finally, the nobility of Earth is reaffirmed in relation to its correlates among the five tones, five flavors, and five colors: “The righteousness of the loyal minister and the actions of the filial son are derived from Earth. Earth is the most noble of the Five Phases, and nothing can augment its righteousness, [just as] of the five tones, none is more noble than

gong; of the five flavors, none is more noble than sweetness; of the five colors, none is more luxuriant than yellow.”

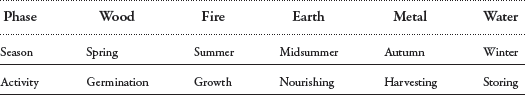

31Chapter 42, “The Meaning of the Five Phases,” repeats many of the arguments that appear in chapter 38.1. The phases are listed in the Mutual Production Sequence, called here the “Heavenly endowed sequence,” which is said to embody the father–son relationship. Heaven is identified with filial piety and Earth with loyalty, two of the five modes of virtuous conduct. Here, too, Earth enjoys a special status in relation to the Five Phases. The phases are correlated with the seasons and directions in the standard ways: Wood-spring-east; Fire-summer-south; Earth-[no season]-center; Metal-autumn-west; and Water-winter-north. Earth is not correlated with any particular season (unlike in chapter 38.1, which employs the alternative strategy of positing a special season of “midsummer” for Earth); instead, its influence is distributed over all the four natural seasons. The emphasis of the Five-Phase reasoning in

chapter 42 is entirely on ethical issues, foregrounded in filial piety. The ruler, ritually facing south, conforms to the influences and activities of the phases according to the correlations shown in

table 2. As presented here, the relationships between Wood and Fire and between Metal and Water are interesting and unusual. When Wood is born, its lesser yang is nurtured by the greater yang of its successor, Fire; when Metal is born, its demise is both hastened and mourned by its successor, Water. With these specific correlations defined, the remainder of the essay expands on the special status of Earth as the “Heavenly Fructifier,” the “arms and legs of Heaven.” Just as the four flavors—sourness, saltiness, acridness, and bitterness—could not perfect their respective tastes without the ruling flavor of sweetness (as was already affirmed in

chapter 38), the four seasonal phases could not accomplish their respective functions without the assistance of the ruling phase, Earth: “Sweetness is the root of the Five Tastes; Earth is the ruler of the Five Phases.”

32

TABLE 2

In its current form,

chapter 42 does not explicitly subordinate Earth to Fire. But it originally may have done so, as in

chapter 38. The passage that we just quoted—“Earth dwells in the center, … helping Fire blend, harmonize, nourish, and grow” but “is not named as having done such things, and all the achievement is ascribed to Fire”

33—places Earth in the role of the loyal minister, wielding great power but selflessly subordinating himself to the great yang authority of the ruler. The chapter concludes by once again correlating Earth with the virtue of loyalty. This emphasis on loyalty is a distinctive feature of

chapters 38 and

42.

The similarity in the structure and content of the arguments presented in

chapters 38 and

42 suggests that they are closely related, and both chapters also share important features with

chapters 43 and

44. Both

chapters 38 and

42 develop the cosmic implications of filial piety and loyalty celebrated in the

Classic of Filial Piety by establishing clear links to the Mutual Production Sequence of the Five Phases. As we shall see, these distinctive features provide important clues to the dating and attribution of these chapters.

Chapter 41, “Heaven, the Maker of Humankind,” also has important links to the

Classic of Filial Piety. The title of the chapter derives from its opening lines, which assert the categorical unity of Heaven and humanity: “What gives birth cannot make human beings. The maker of human beings is Heaven. The humanness of human beings is rooted in Heaven. Heaven is also the supreme ancestor of human beings. This is why human beings are elevated to be categorized with Heaven.”

34 Section 41.1 discusses the human correlates of Heaven, supplying many examples that will be elaborated in

group 5, “Yin-Yang Principles.” The task of the ruler, the passage concludes, is to husband these Heaven-endowed aspects of the self.

Section 41.2 similarly draws on the

Classic of Filial Piety to lend authority to its statements. This section consists of three short passages (four, if we include a short passage now located in chapter 38.2 that probably was originally part of section 41.2). Each has a number of identical formal features, and each begins with a short saying introduced by the formulaic phrase “a tradition states” (

zhuan yue 傳曰), an expression often used in the

Chunqiu fanlu and other Han texts to introduce lore transmitted orally through the generations.

35 The saying is then briefly explained, beginning with a term or phrase repeated from the opening saying. The explication concludes with a citation from the

Classic of Filial Piety marked off with the standard “Thus it is said” (

gu yue 故曰).

36 A typical example is the following:

OPENING SAYING

A tradition states: “The Son of Heaven alone receives orders from Heaven; the world receives orders from the Son of Heaven; a single state receives orders from its lord.”

If the lord’s orders comply [with Heaven], the people will have cause to comply with his orders; if the lord’s orders defy [Heaven], the people will have cause to disobey his orders.

37

CONCLUDING CANONICAL REFERENCE

Thus it is said: “When the One Man enjoys blessings, the myriad commoners will rely on it.”

The formal features employed here and in chapter 38.2 follow a pattern of explication seen most prominently in the

Hanshi waizhuan,

39 the only significant difference being that the explications of oral sayings in that text close with citations from the

Classic of Odes rather than the

Classic of Filial Piety. There is no doubt, however, that these three chapters—38, 41, and 42—appear at this point in the text because of their common aim to explicate various aspects of filial piety and that their focus on a key Confucian virtue supports their identification as part of

group 4, “Ethical Principles.”

Issues of Dating and Attribution

The chapters of

group 4 preserve quite diverse materials. Their dates, and the authorship of these chapters and their sections, can be assigned with varying degrees of certainty. Some (chapters 30.2 and 32) are unquestionably the work of Dong Zhongshu; we know that because the same materials have been preserved in other Han sources that identify Dong as their author. Others (

chapters 35 and

36) may confidently be attributed to Dong because they are similar in spirit to statements on the same subject ascribed to him in Han sources or because they are highly consistent with Han descriptions of his thought. Several chapters in this group (29, 30, 31, 33, 34) may reasonably be ascribed to Dong Zhongshu or his disciples, but without direct evidence of their authorship, because they are broadly consistent with what we know about Dong’s teachings.

On the other end of the spectrum, we find materials that almost certainly are not by Dong Zhongshu or anyone in his immediate circle.

Chapter 41 represents an exegetical tradition grounded in the

Classic of Filial Piety; no independent contemporary source links Dong’s teachings to that text. The formal character of

chapter 38 leads us to believe that it is a forgery, and both it and the closely related

chapter 42 address themes that did not arise in Han political discourse until well after Dong Zhongshu’s lifetime.

Han shu 56, “The Biography of Dong Zhongshu,” provides corroborating evidence that several chapters (and one section) in this group are by Dong Zhongshu: chapters 30.2, 32, 35, and 36. For example, in his memorial to Emperor Wu, Dong Zhongshu grounds his omenology in the

Spring and Autumn and in Confucius’s authorial intentions. In addition, Dong’s memorial states, “When a state is about to suffer a defeat because [the ruler] has strayed from the proper path, Heaven first sends forth disastrous and harmful [signs] to reprimand and warn him. If the [ruler] does not know to look into himself [in response], then Heaven again sends forth strange and bizarre [signs] to frighten and startle him.”

40 The language and spirit of the brief passage on anomalies that constitutes chapter 30.2 is nearly identical to these passages from Dong’s memorials. Consider, for example, “Natural disasters are Heaven’s warnings; bizarre events are Heaven’s threats. If Heaven warns [the ruler] and he does not acknowledge [these warnings], then Heaven will frighten him with threats.”

41 Given that 30.2 so closely resembles arguments in Dong’s first memorial to Emperor Wu, preserved in

Han shu 56, and that it also contains the kind of formulaic language known to have been used in memorials, petitions, and letters to the throne, we believe this to be an excerpt from the original memorial to Emperor Wu. The small differences between the two documents are probably simply the result of typical editorial decisions made by Ban Gu when he quoted the memorial in “The Biography of Dong Zhongshu.”

Chapter 32, preserving an official exchange between King Yi of Jiangdu and Dong Zhongshu, also is quoted in

Han shu 56, attesting to its early provenance and the reliability of its attribution to Dong Zhongshu. The formulaic writing of the document also indicates beyond question that it is a contemporary record of an official communication. This communication must have been sent to the imperial court, where it was read and then stored in the imperial archives. Thus it would have been available years later to Ban Gu, who included it in his biography of Dong Zhongshu.

42 Furthermore, the opening line of

chapter 32 refers to Dong’s official title, administrator. Dong Zhongshu served Liu Fei, who reigned as King Yi of Jiangdu, in that capacity for several years beginning in the mid-130s

B.C.E., enabling us to date the document with reasonable accuracy.

43 We also can match the document’s political agenda to events occurring at that time. Although on the surface,

chapter 32 is a discussion of humaneness and its relationship to hegemonic rule, in reality it is a coded discussion of the mounting challenges posed by the Xiongnu, who threatened China’s northern frontier. The

Shiji reports: “In the fifth year of the Yuanguang era (130

B.C.E.), when the Xiongnu were invading and plundering Han territory in great numbers, [Liu] Fei submitted a letter [to Emperor Wu] requesting permission to attack the Xiongnu, but the throne did not grant permission.”

44 In

chapter 32, the humiliations suffered by King Goujian of Yue at Guiji, when his army was surrounded and defeated by the army of King Fuchai of Wu, allow Dong Zhongshu to argue, using veiled language, against Liu Fei’s enthusiasm for leading an attack on the Xiongnu. This grounding in historical events provides additional corroboration that

chapter 32 was written by Dong Zhongshu himself.

45

Chapters 35 and

36 address human nature, a topic on which thinkers during the Warring States period expressed a range of strong opinions and which continued to attract great interest among Han intellectuals. Its continued importance is hardly surprising, given the demand for well-educated, morally upright officials to staff the burgeoning bureaucracy of the Han Empire. Human nature also pertained to the question of the education of the emperor himself and his designated heir. Influential scholars from Lu Jia, Jia Yi, Liu An, Liu Xiang, and Yang Xiong in the Western Han to Ban Gu, Wang Chong, Xu Shen, Wang Fu, and Xun Yue in the Eastern Han, offered their views concerning human nature. Dong Zhongshu was no exception. Indeed, the content of these essays, with their polemical edge and combative claim that contemporary discussions on human nature are hopelessly mired in confusion, indicates that they were written as contributions to a robust and flourishing discourse on the topic.

The earliest surviving testimony to Dong’s views on human nature beyond the

Chunqiu fanlu come from his memorials preserved in

Han shu 56. There we find a discussion of human nature wholly consonant with that of

chapters 35 and

36 of the

Chunqiu fanlu: left to their own devices, human beings are incapable of becoming good; they are wholly reliant on the transformative influences of moral instruction initiated by the sage-king.

The distinction between the nature and the disposition made in this chapter also appears in

chapter 35: “A person has a nature and emotions just as Heaven possesses yin and yang. To speak of one’s basic substance without mentioning one’s emotions is like speaking of Heaven’s yang without mentioning its yin.”

Chapter 36 likens human nature to raw materials and claims: “What Heaven does stops with the cocoon, hemp, and rice plant. Using hemp to make cloth, the cocoon to make silk, the rice plant to make food, and the nature to make goodness—these all are things that the sage inherits from Heaven and advances. They are not things that the unadorned substance of the emotions and the nature is able to achieve.”

46Further evidence comes from the works of Wang Chong. His essay “The Basic Nature” echoes an essay on human nature by Dong Zhongshu, who was said to have appraised the theories of Mencius and Xunzi. Wang Chong portrays Dong as associating the disposition and nature with yin and yang:

Dong Zhongshu surveyed the writings of Sun [Xunzi] and Mengzi and created a theory about the disposition and the nature. He said, “The great constancy of Heaven consists of yin and yang; the great constancy of humankind consists of the disposition and the nature. The nature is born of yang and the disposition is born of yin. Yin qi is base and yang qi is humane.” Those who say that the nature is good are those who look at yang; those who say it is bad are those who look at yin.

47

Wang Chong appears to be describing Dong’s views accurately, for these correlates are likewise found in

chapter 35, which argues that the

qi of both humaneness and greed coexist in the body:

Now if I use the name “mind” to apprehend the true character of human beings, then I must conclude that the truth about human beings is that they possess both greed and humaneness. The

qi of humaneness and greed coexist in the self…. Heaven [imposes] prohibitions pertaining to yin and yang; the self [observes] restraints on the emotions and desires. In this respect, it is identical to the Way of Heaven…. What Heaven restricts is also restricted in the body…. One must understand that if the Heaven-bestowed nature is not supplemented by education, it ultimately cannot be restrained.

48

Thus we find that

chapters 35 and

36 of the

Chunqiu fanlu are consistent with all surviving contemporaneous claims about Dong’s theory of human nature.

Chapter 38, “An Official Response Regarding the Five Phases,” purports to be an official exchange between King Xian of Hejian and Dong Zhongshu, but the discerning reader will recognize that it is problematical. First, the document is devoid of any of the formulaic expressions of humility that were required in communications to the throne. In responding to the questions raised by King Xian, the so-called Master Dong from Wenchang makes no use of the self-effacing prostrations or expressions that typically preface a response from a subordinate to a superior, such as “Your humble servant” and “knocking his head and bowing.” We could hypothesize that such language was edited out of the document, but why would any editor do that and so portray Dong as committing an almost treasonous ritual affront? A comparison with the two other “official responses” preserved in the text,

chapters 32 and

71, makes the deficiencies of

chapter 38 glaringly apparent. Second, an encounter between Dong Zhongshu and the king of Hejian seems unlikely. Liu De, the son of Emperor Jing by his concubine Lady Li, was appointed as King Xian of Hejian in the second year of Emperor Jing’s reign, 155

B.C.E., and he remained in this post for the next twenty-six years until his death in 129

B.C.E.

49 Liu De was an important patron of Confucian learning. He made great efforts to attract scholars to his court and to collect copies of precious pre-Qin texts for his library, which rivaled that of the capital. He is reported to have done much to promote the

Zuo Commentary, the

Rites of Zhou, and texts associated with the Mao interpretations of the

Odes. There is no evidence that he would have been interested in the views of Dong Zhongshu, a proponent of the

Gongyang Commentary. Third, the reference to “Master Dong from Wencheng” in an official document is equally odd and suspicious. The two official exchanges preserved in

chapters 32 and

71 refer to Dong by his full name and his official titles (the administrator of Jiangdu and the former administrator of Jiaoxi, respectively). Su Yu surmises that the place-name “Wencheng” (

溫成) could be a mistake for “Changcheng” (

昌成), the name of one of the counties in Dong’s native place, the kingdom of Guangchuan (

廣川). But the identification of Dong Zhongshu with this otherwise unknown “Master Dong of Wenchang” seems quite tenuous. In addition, the definition of righteousness used in this supposed official document departs significantly from other teachings about righteousness identified with Dong Zhongshu. Recall that

chapter 29 maintains, for example, that righteousness refers to the self and is the means to correct the self. All these considerations suggest that

chapter 38, if it indeed was supposed to be the work of Dong Zhongshu, is a forgery.

A final point supports that conclusion and speaks to the probable late date of

chapter 38 and the closely related

chapter 42. The subordination of the phase Earth to the phase Fire peculiar to these two chapters (and to the fragment about Fire and Earth that is currently numbered 43.2 but that may originally have been part of

chapter 38 or of

chapter 42) indicates that those chapters could not have been written by Dong Zhongshu or anyone in the early generations of his disciples. Rather, these chapters express a form of highly politicized Five-Phase rhetoric that dates them to the time of Wang Mang. In our introduction to

group 6, “Five-Phase Principles,” we write at length about the polemics associated with the Mutual Production Sequence of the Five Phases that took hold in elite circles toward the end of the Western Han. We note here only that Wang Mang used the Five-Phase theories to support his claim to be the legitimate heir to the Han. Wang Mang identified the ruling power of the Han dynasty as Fire and his own Xin dynasty with the power of Earth; just as Fire peacefully and naturally produces Earth as ashes, so did the Han give way to the Xin. Here we find the key to the emphasis on loyalty in

chapters 38 and

42. It is completely consistent with the arguments that scholars loyal to Wang Mang may have used to demonstrate Wang Mang’s own “great loyalty” to the ruling house of Liu and his filial devotion as the “son” and heir to the former Han rulers. These chapters therefore are best understood as potent political arguments cloaked in cosmological language that clearly postdate Dong Zhongshu.

Summing up, all the chapters in this group address, in one way or another, issues relating to virtues highly esteemed by Confucian scholars during the Western Han. But they represent a range of dates and authorship.

Chapters 29 through

37 are likely to be the work of, or closely associated with, Dong Zhongshu and his circle;

chapter 41 seems atypical of Dong’s teachings and exegetical interests; and

chapters 38 and

42 are both late in time and alien to Dong Zhongshu’s tradition.