As you get more adventurous with CSS, you'll probably encounter—like many web designers before you—some of the weird intricacies of working with floats. This section describes a few common problems and their solutions. (And if you ever stumble upon a problem not listed here, you can always take it to one of the online forums or discussion lists in Appendix C.)

Note

When it comes to designing pages that work in Internet Explorer 6, there are even more potential pitfalls. So many, in fact, that this chapter has a separate section dedicated to dealing with that one browser. See Handling Internet Explorer 6 Bugs.

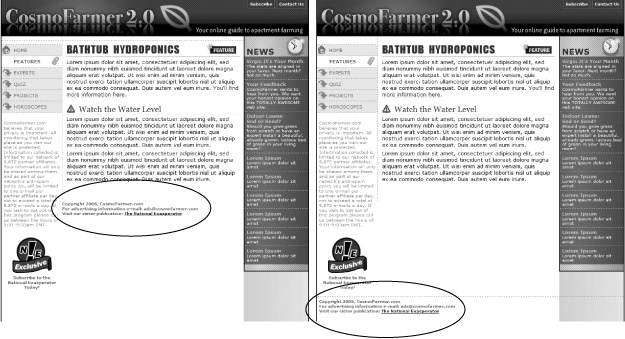

Floats are powerful design tools because they let content flow around them. Floating a photo lets text below it move up and wrap around the image (Figure 12-1). When you're creating float-based column designs, though, sometimes you don't want content to move up and next to a floated element. For example, you frequently want to keep copyright notices, contact information, or other housekeeping details at the bottom of your web page, below all other content.

In the two- and three-column designs you've seen so far, if the main column is shorter than either of the floated sidebar columns, a footer can move up and around the left floated column (Figure 12-7, left). To make the footer stay down below the sidebars, you can use the clear property (Stopping the Float). This property prevents an element from wrapping around floats. You can make an element drop below a left-floated object (clear: left;) or a right floated object (clear: right;). For footers and other items that need to appear at the bottom of the page, you should clear both left and right floats, like this:

#footer { clear: both; }Figure 12-7. You don't always want an item to wrap around a floated element (left). Copyright notices and other material that belongs at the bottom of a page usually need to clear any floats they encounter. To achieve this, use the clear property for the copyright notice to force it to the bottom of the page below any floated elements.

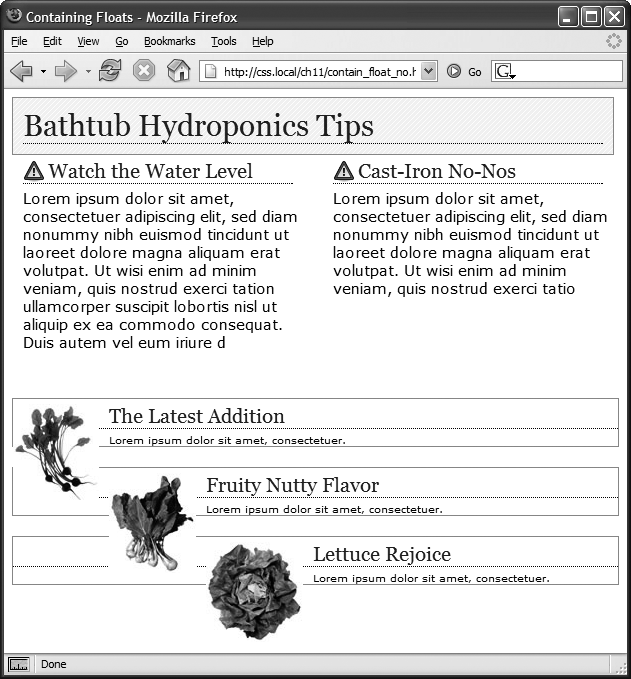

Another problem occurs when you float one or more elements inside a non-floated containing tag like a <div> tag. When the floated element is taller than the other content inside the div, it sticks out of the bottom of the enclosing element. This snafu is especially noticeable if that tag has a background or border. The top of the web page in Figure 12-8 shows a <div> tag that has an <h1> tag and two columns created by floating two divs. The background and border, which appear only around the <h1> tag, are actually applied to the entire enclosing <div>, including the area where the two columns are. However, since the columns are floated, they pop out of the bottom instead of expanding the borders of the box.

Note

For a good explanation of why floated elements can break outside of their containing blocks, read www.complexspiral.com/publications/containing-floats.

A similar problem happens in the bottom example in Figure 12-8. In this case, each image is floated left inside a containing <div> that has a border. Because the images are taller than their boxes, they pop out of the bottom. Unfortunately, this example is even worse than the previous one, because each image causes the image below it to wrap to the right, creating an ugly staggered effect.

Figure 12-8. A floated element can escape its containing <div> if it's taller than the container itself. If the containing tag includes a background or border, then the escaping elements can look like they're not even part of the container (top of page). In addition, a floated element can bump into other elements—including other floats, thereby creating a "stair-stepped" effect (bottom of page) instead of the nicely stacked boxes in Figure 12-9.

You have many ways to tackle the problem of these renegade floating elements. We'll cover all of these techniques below, because it's good to have more than one solution under your belt.

Add a clearing element at the bottom of the containing div. This solution is the most straightforward. Simply add a tag—like a line break or horizontal rule—as the last item in the <div> containing the floated element (that is, right before the closing </div> tag). Then use the clear property to force that extra tag below the float. This trick makes the enclosing div expand, revealing its background and border. You can add a line break—<br> (HTML) or <br /> (XHTML)—before the closing </div> tag and add a class to it: <br class="clear"/>. Then create a style for it, like this:

br.clear { clear: both; }The problem with this technique is that it adds extra HTML.

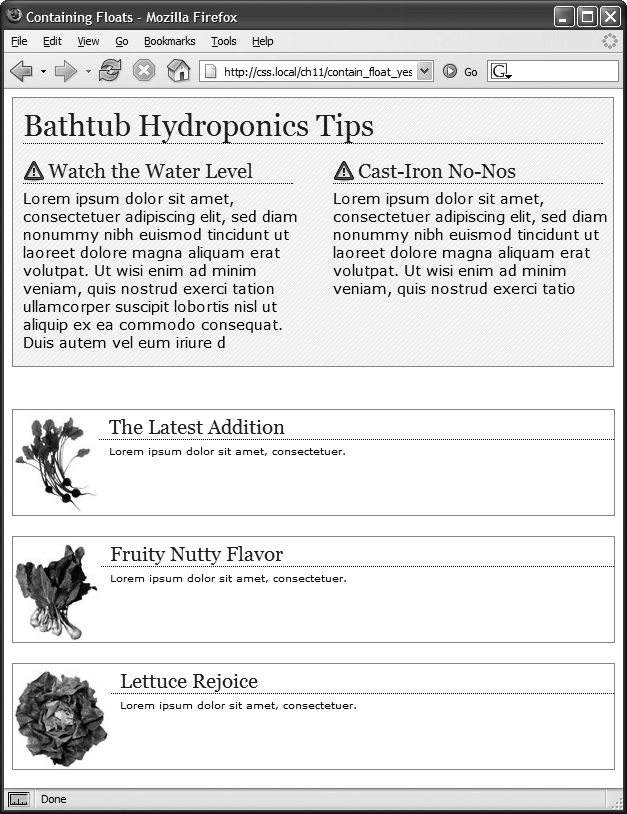

Float the containing element. An easier way is to just float the <div> containing the floated elements as well. A floated container <div> expands to fully contain any floated elements inside it. In Figure 12-9, top, the <div> containing the heading and two floated columns is floated to the left of the page. In the process, its entire box—background and borders—expands to fit everything inside it, including the floated elements. Strange, but true.

If you go this route, make sure you add a clear property to whatever element follows the floated container to make sure the following element drops below the container.

Use overflow:hidden. Another common technique is to add the following two properties to a style for the containing block:

overflow: hidden; zoom: 1;

The overflow:hidden property is just another one of those weird CSS things: It forces the containing block to expand and contain the floated elements. The zoom:1 is just for Internet Explorer 6 (and earlier)—it won't affect any other browser. If you want you can put this property into a separate style sheet using IE conditional comments described on Isolate CSS for IE with Conditional Comments. (The whole zoom:1 weirdness is described in the box on Stopping the Float.)

In general, this technique works very well. However, if you have any absolutely positioned elements (see How Positioning Properties Work) inside the container, they may not show up. You can get into this situation if you have a drop-down menu inside another tag and the drop-downs, when they appear, are supposed to appear outside the container element. If that's the case, use one of the other methods described on these pages.

Use the "easy clearing method." With this technique, created by Tony Aslett of CssCreator.com and the folks behind PositionIsEverything.com, you add just a few styles and a class name to the <div> tag containing the floated element. Of course, the name "easy clearing method" is a bit of a misnomer, since the CSS behind it is anything but easy. You must add three different styles to your style sheet: One applies to Firefox, Safari, Internet Explorer 8, and other modern browsers; another style applies to IE 7 and earlier. The whole shebang looks like this:

.clear:after { content: "."; display: block; height: 0; font-size: 0; clear: both; visibility: hidden; } .clear { zoom:1; }The last two styles make IE 5, 6, and 7 "have layout" as described in the box on Tutorial: Multiple-Column Layouts.

Once you've added these styles to a style sheet, you simply add the class name to the div containing the escaping floats: <div class="clear">. See the bottom of Figure 12-9. This technique is very reliable; however, unlike the previous two techniques, you do have to add extra HTML to the page.

Note

The zoom property makes your page flunk the CSS validator check. To get around that, you can put this rule (along with any other IE-only styles) into an external style sheet and attach it to your web pages using any of the tricks described in Chapter 15 (Using Multiple Style Sheets).

Figure 12-9. Don't let a float escape! You have several ways to make floated elements stay inside the borders and backgrounds of their containing tag. Two methods are pictured here, though any of the four discussed would produce the same results. Floating the container works (top), as does a special combination of CSS—affectionately called the "easy clearing method" (bottom). Both methods result in borders and backgrounds that surround the container and the floats inside.

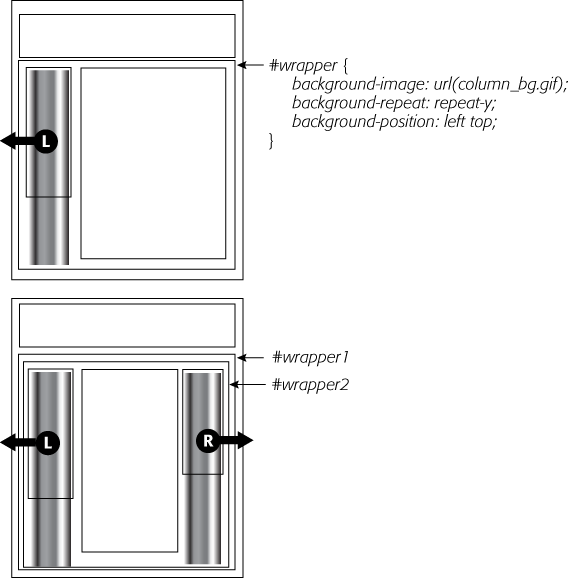

HTML tables aren't great for web page layout for several reasons. They add lots of code, are difficult to update, and don't work well on alternative browsers like those used by cellphones. But tables have one thing going for them in the layout department—the ability to create columns of equal height. Equal-height columns let you add a background color or graphic to one column and have it fill the entire height of the page. The backgrounds of the two sidebars in the top image of Figure 12-10 fill the screen height, creating solid, bold stripes on either side of the page.

CSS floats, on the other hand, fall a bit short in this regard. Table cells in a row are always the same height, which isn't true of divs. The height of a float is usually dictated by the content inside it. When there's not a lot of content, the float is not very tall. Since a background image or background color fills only the float, you can end up with solid-colored columns that stop short of the page bottom, as in the circled areas in Figure 12-10, bottom.

As with most problems related to CSS, there's a workaround. The secret is to add background images to a tag that wraps around the stubby sidebar and the other columns on the page. Say your HTML has two <div> tags that contain the content for a left sidebar and the page's main content:

<div id="sidebar">Sidebar content here</div> <div id="main">Main content for page, this column has a lot of text and is much taller than the sidebar.</div>

The sidebar <div> is floated to the left edge of the page and has a width of 170 pixels. Because there's less content in the sidebar, it's shorter than the main text. Suppose you wrap that HTML in a wrapper <div> tag, like so:

<div id="wrapper"> <div id="sidebar">Sidebar content here</div> <div id="main">Main content for page, this column has a lot of text and is much taller than the sidebar.</div> </div>

That outer div grows to be as tall as the tallest element inside it, so even if the #main div is very tall, that wrapper div will be just as tall. Here's the magic: Create a style for the wrapper <div> with a background image the width of the sidebar, in the background color you want for the sidebar. That way, if the background image tiles vertically, it forms a solid bar the height of the wrapper <div> (Figure 12-10, top).

#wrapper { background: url (images/col_bg.gif) repeat-y left top; }Web browsers display that background image directly under the sidebar, creating the illusion that the sidebar has a background color. In essence, you create a "faux column" in the words of Dan Cederholm, the fellow who first publicized this technique.

Figure 12-10. Full-height columns with bold background colors are a common design technique. The left and right sidebars (top) show how solid backgrounds can help visually define the different areas of a page. When a sidebar's background stops abruptly (circled at bottom), you get extra white space that's both distracting and unappealing.

Note

You're not limited to solid colors either. Since you're using an image anyway, you can make a decorative pattern that tiles seamlessly down the left side of the page.

Reproducing this result for two columns is just a little more involved. First, add two wrapper divs:

<div id="wrapper1"> <div id="wrapper2"> <div id="sidebar1">Sidebar content here</div> <div id="sidebar2">Second sidebar</div> <div id="main">Main content for page, this column has a lot of text and is much taller than the two sidebars.</div> </div> </div>

Note

If the wrapper and each column are all fixed widths, you can create this "faux column" look for both the left and right columns with just a single image and wrapper div. Just make the graphic as wide as the wrapper, with the left side of the graphic being the color and width of the left sidebar, the right side of the graphic the color and width of the right sidebar, and the center part of the graphic matching the background color of the center column.

If the first sidebar appears on the left side of the page and the second sidebar appears on the right side, you create two styles. Apply one style to the first wrapper <div> tag to add a background to the left sidebar; apply one to the second wrapper <div> to add a background to the right sidebar (Figure 12-11, bottom).

#wrapper1 { background: url(images/col1_bg.gif) repeat-y left top; }

#wrapper2 { background: url(images/col2_bg.gif) repeat-y right top; }When adding a background image to the right-hand column, make sure you position the background image in the top right of the second wrapper, so that it falls underneath the second sidebar on the right side of the page.

Note

If you use percentages to define the width of columns, then it's more difficult to create the illusion of full-height columns using graphics. But it's not impossible. To learn how, go to www.communitymx.com/content/article.cfm?page=1&cid=AFC58.

Suddenly, one of your columns simply drops down below the others (Figure 12-12, top). It looks like there's plenty of room for all the columns to coexist perfectly side by side, but they just don't. You've got the dreaded float drop.

A floated column drops down because there's not enough room to fit it. Be careful if you set widths for each column. If the available space in the browser window (or the containing block in a fixed-width design) is less than the total widths of the columns, then you're asking for a float drop. Also, keep the CSS box model in mind: As discussed in the box on Margin and Padding Shorthand, the width of an element displayed in the browser window isn't the same as its width property. The displayed width of any element is a combination of its width, left and right border sizes, left and right padding, and left and right margins. For the columns to fit, the browser window (or containing block) must accommodate the combined total of all those widths.

Figure 12-11. You sometimes need to think outside the tag for creative solutions to CSS problems. To get full-height backgrounds behind floated columns, you need to resort to some extra <div> tags that wrap around all of the main columns of text. These divs grow to be the height of the tallest column in the group. By adding background images to these wrapper divs, you create the appearance of equal-height columns.

Take, for example, the simple three-column layout in Figure 12-12. As you can see in the top example, the three columns don't fit. Here's a breakdown of the math behind the problem:

Wrapper div. A fixed-width wrapper <div> tag encloses the entire design. Its width property is set to 760 pixels, so all three columns can't total more than that.

Sidebar 1 (left side). Its width is 150 pixels, but it also has 10 pixels of padding, making its total onscreen width 170 pixels. (150 + 10 pixels of left padding + 10 pixels of right padding.)

Main content. The main content <div> is 390 pixels wide, with a 1-pixel border and 15 pixels of left and right margin for a total width of 422 pixels. (You may need a calculator for this one: 390 + 1 [left border] +1 [right border] + 15 [left margin] + 15 [right margin].)

Sidebar 2 (right side). This element has a width property set to 150 pixels, with 10 pixels of left and 10 pixels of right padding: 170 pixels, just like Sidebar 1.

The actual widths of each element add up to a grand total of 762 pixels. That's two pixels more than the width of the wrapper <div>. The middle image of Figure 12-12 shows an outline around the main content <div> indicating its total width plus margins. Just those measly two extra pixels of width (circled) are enough to cause a column to drop down. The solution: Remove 2 pixels of space from any of the elements. Changing the main content div's left and right margins from 15 to 14 pixels buys you the extra room needed for all three columns to fit side by side (bottom).

Figure 12-12. It takes only a single pixel or two to ruin a design. When the width of floated elements are just a hair wider than their containing block (like a <div> with a set width, or even the browser window itself), the last floated element drops below the others (top). The actual width of an element combines many CSS properties. In the middle image, the outline around the main content area shows that it's a tad too wide to allow the right sidebar to fit (circled). Adjusting any of the elements by removing a bit of width, padding, or margins can solve the problem (bottom).

While miscalculated column widths are the most common cause of dropping floats, they're not the only cause. Here are a few other culprits:

Rounding errors in percentage widths. Be careful when setting widths in percentages. Browsers sometimes make mistakes when calculating the actual number of pixels needed to display something on the screen. That is, they can round numbers up, making elements slightly too large for the available space. So err on the side of caution and make your percentage widths total slightly less than 100 percent.

Internet Explorer 6's double-margin bug. Under some conditions, Internet Explorer 6 and earlier doubles the margin applied to a floated element, making the element wider than in other browsers. When you have a float drop occurring only in IE 6 or earlier, this bug may be the culprit. See below for a solution.

Internet Explorer 6's 3-pixel gap. Sometimes IE 6 and earlier adds an extra 3 pixels to the side of a float. Again, if you see a float drop only in IE, then this bug could be the reason. See 3-Pixel Gaps for an explanation and solution.

Italic text. IE 6 strikes again (noticing a theme here?) If a floated element contains italicized text, then IE 6 sometimes makes the float wider. When there's a float drop and italics inside the float, check to see if the problem is happening in all browsers or only IE. For a solution, you can remove any italics from the sidebar or add overflow: hidden to the style formatting the sidebar.

Bottom line: Float drops are always caused by not enough room to hold all of the columns. Rather than striving to use every last pixel of onscreen space, give all your elements a little more wiggle room. Get in the habit of making the overall column widths a bit smaller than necessary, and you'll spend less time troubleshooting float drops.