Chapter 7. Basic Image Retouching

You may be perfectly happy using Elements only in Quick Fix mode. That’s fine, as long as you understand that you’ve hardly scratched the surface of what the program can do. Sooner or later, you’ll probably run across a photo where your best Quick Fix efforts just aren’t enough. Or maybe you’re simply curious what else Elements has under its hood. That’s when you finally get to put all your image-selecting and layering skills to good use.

Elements gives you loads of ways to fix photos beyond the limited options in Quick Fix. This chapter guides you through fixing basic exposure problems, shows you various ways of sharpening photos, and (most importantly) explains how to improve the colors in your images. You’ll also learn how to use the amazing Smart Brush tool that lets you apply many common fixes by brushing over the problem area.

To get the most out of Elements, you need to understand a little about how your camera, computer, and printer think about color. Along with resolution (Changing the Size of an Image), color is one of the most important concepts in Elements. After all, almost all the adjustments that image-editing programs make involve changing the color of pixels. So quite a bit of this chapter is about understanding how Elements—and by extension, you—can manipulate the color in images.

Tip

Most of Elements’ advanced-fix dialog boxes have a Preview checkbox that lets you watch what’s happening as you adjust the settings. It’s a good idea to keep these checkboxes turned on so you can decide whether you’re improving things. And for a handy “before” and “after” comparison, simply toggle the checkbox on and off.

Fixing Exposure Problems

Incorrectly exposed photos are the number one problem photographers face. No matter how carefully you set up a shot and how many different settings you try on your camera, it always seems like the picture you want to keep is the one that’s over- or underexposed.

The Quick Fix commands (Smart Fix) can really help photos, but if you’ve tried using them to bring back a picture that’s badly exposed, you’ve probably run into the limitations of what Quick Fix can do. Similarly, the Shadows/Highlights command (The Shadows/Highlights Command) can do a lot, but it’s not intended to fix a photo whose exposure is totally botched—just ones where the contrast between light and dark areas needs a bit of help. And if you push Smart Fix (Smart Fix) to its limits, the results may be a little strange. In those situations, you need to move on to some of Elements’ more powerful tools to help improve the image’s exposure.

Tip

In this section, you’ll learn about the more traditional ways of correcting exposure in Elements, as well as how to use the Smart Brush tool for corrections. But be sure to also check out the Adobe Camera Raw Converter (The Raw Converter), which can help with your JPEG and TIFF images, too. Your results with non-raw photos may vary, but the Raw Converter just might turn out to be your best choice.

Deciding Which Exposure Fix to Use

When you open a poorly exposed photo in Elements, the first thing to do is figure out what’s wrong with it, just like a doctor diagnosing a patient. If the exposure isn’t right, what exactly is the problem? Here’s a list of common symptoms to help figure out what to do next:

Everything is too dark. If your photo is really dark, try adding a Screen layer, as explained on The Shadows/Highlights Command. If it’s just a bit too dark, try using Levels (Using Levels).

Everything is too light. If the whole photo looks washed out, try adding a Multiply layer (The Shadows/Highlights Command). If it’s just a bit too light, try Levels (Using Levels).

The photo is mostly OK, but the subject is too dark or the light parts of the photo are too light. Try the Shadows/Highlights command (The Shadows/Highlights Command) or the Smart Brush tool (Correcting Part of an Image).

You just can’t decide quite what the problem is. Try Auto Smart Tone (Auto Smart Tone), which adjusts the overall tone of your photo as you drag around a grid.

If you’re lucky (or a really skilled photographer), you may not see any of these problems, in which case, skip to Using Levels if you want to make the image’s colors pop. And if you’re lucky enough to have bracketed exposures (multiple exposures of exactly the same image), then check out the Exposure Merge feature (Blending Exposures), which makes it simple to blend them into one properly exposed image.

Note

You may have noticed that Brightness/Contrast (Contrast) wasn’t mentioned in the preceding list. A lot of people jump for the Brightness/Contrast controls when facing a poorly exposed photo. That’s logical—after all, these settings can usually help improve the picture on your TV or monitor. But in Elements, about 99 percent of the time, you’ve got a whole slew of powerful tools—like Levels and the Shadows/Highlights command—that can do much more than Brightness/Contrast can, but feel free to give Brightness/Contrast a try when you need to make only very subtle changes.

Fixing Major Exposure Problems

If your photo is completely over- or underexposed, you need to add special layers to correct the problem. You follow the same steps to fix either issue; the only difference is the layer blend mode (Image Views) you use: Multiply darkens an image’s exposure while Screen lightens it. Figure 7-1 shows Multiply in action and gives you a sense of the limitations of this technique if your photo’s exposure is really far gone.

Be careful, though: If only part of your photo is out of whack, using a Multiply or Screen layer can ruin the exposure of the parts that were OK to start with, because these layers increase or decrease the exposure of the whole photo. So if the exposure problem doesn’t affect the entire image, try the Smart Brush (Correcting Part of an Image) or Shadows/Highlights command (The Shadows/Highlights Command) instead. Or use a layer mask to restrict the Multiply or Screen layer’s changes to only part of the image, as explained in step 4 next.

If the whole photo needs an exposure correction, here’s how to use layers to fix it:

Duplicate your image layer.

Open your photo and press Ctrl+J/⌘-J or go to Layer→Duplicate Layer. Check to be sure the duplicate layer is the active layer.

In the Layers panel, change the new layer’s blend mode.

From the drop-down menu in the panel’s upper left, choose Multiply if the photo is overexposed or Screen if it’s underexposed. (Make sure you change the duplicate layer’s mode, not the original layer’s.)

If needed, adjust the layer’s opacity.

If the effect of the new layer is too strong, then at the top of the Layers panel, lower its Opacity setting.

If you decide that part of the image was better exposed before you added the new layer, mask out the areas where the exposure was OK.

Follow the instructions on Layer Masks to add a mask to the duplicate layer, and then paint with black over the areas where the original image was properly exposed so that the Background layer shows through. Remember that you can also paint on the mask with shades of gray to control how much of the original shows through, which can be very helpful in getting the most realistic results from this technique.

Repeat as necessary.

You may have to use as many as five or six layers if your photo is in really bad shape. If you need extra layers, you’ll probably want them at 100 percent opacity, so you can just keep pressing Ctrl+J/⌘-J to duplicate the current top layer, including its layer mask (if you added one).

You’re more likely to need several more layers to fix overexposure than underexposure. And there are limits to what Elements can do for a blindingly overexposed image. Overexposure is usually tougher to fix than underexposure, especially if the area is blown out (see the box on Avoiding Blowouts).

The Shadows/Highlights Command

This command is one of Elements’ best features. It’s incredibly powerful for adjusting only the dark or light areas of a photo without messing up the rest of it. Figure 7-2 shows what a great help it can be.

The Shadows/Highlights command in Expert mode works pretty much the same way it does in Quick Fix (Shadows, Midtones, and Highlights). The single flaw in this great feature is that you can’t apply it as an Adjustment layer (Adjustment and Fill Layers), so you may want to apply it to a duplicate layer rather than the original. That way, you can discard the changes later on if you want to take another whack at adjusting the photo. In any case, it’s easy to make amazing changes to your photos with Shadows/Highlights. Here’s how:

Open a photo and duplicate the image layer (Ctrl+J/⌘-J) if you want to.

If you haven’t edited the photo before, the image layer is probably the Background layer, but you can use this command on any layer. Duplicating the image layer makes it easier to undo Shadows/Highlights later if you change your mind.

Go to Enhance→Adjust Lighting→Shadows/Highlights.

Elements opens the Shadows/Highlights dialog box and makes your photo several shades lighter. (You may need to drag the dialog box out of the way to get a good view of your image.) Don’t panic—as soon as you select this command, the Lighten Shadows setting automatically jumps to 35 percent, which is way too much for most photos. Just shove the slider back to 0 to undo this change before you start making corrections.

Adjust the sliders in the Shadows/Highlights dialog box until you like the result.

The sliders do exactly what they say: Lighten Shadows makes the dark areas of the photo lighter, and Darken Highlights makes the light areas darker. (Midtone Contrast is discussed in a moment.) Dragging the sliders to the right increases their effect.

When your photo looks good, click OK.

Tip

If you’re applying Shadows/Highlights on a duplicate layer, you can use a layer mask (Layer Masks) to restrict your changes to only certain areas of the image.

The Shadows/Highlights dialog box is a cinch to use because you just make decisions based on what you’re seeing. When you’re using it, keep these tips in mind:

You may want to add a smidgen of the opposite tool to balance things out. For example, if you’re lightening shadows, you may get better results by giving the Darken Highlights slider a teeny nudge, too.

The Midtone Contrast slider can help keep your photo from looking flat after you adjust the other sliders, especially if you’ve made big adjustments. Move the Midtone Contrast slider to the right to increase the photo’s contrast. Doing so usually adds a bit of darkening, so you may need to adjust one of the other sliders after you use it.

You can overdo the Shadows/Highlights feature. If you see halos around the objects in your photo, you’ve pushed the settings too far.

Tip

If the Shadows/Highlights feature washes out your photo’s colors—making everyone look like they’ve been through the laundry too many times—adjust the color intensity with one of the Saturation commands, either in Quick Fix or Expert mode (as described on Auto Color). Watch people’s skin tones when increasing the saturation—if the people in your photo start looking like sunless-tanning-lotion disaster victims, you’ve gone too far. Also, check out the Vibrance slider in Quick Fix (Auto Color), or try adjusting colors with Color Curves (Color Curves: Enhancing Tone and Contrast).

Correcting Part of an Image

The Shadows/Highlights command is great if you want to adjust all the light or dark areas of a photo, but what if you want to tweak the exposure in only certain areas? Or what if the photo’s background looks fine, but you want to tweak the subject a little? You can use a layer mask on a duplicate layer and make adjustments there, or you can select the area you want to tweak, copy the selection to a new layer, and then make adjustments to that layer. But Elements gives you an even simpler way to apply a correction to just the area you want: the Smart Brush tools.

Correcting Color with a Brush

The Smart Brush is actually two different tools—the Smart Brush and the Detail Smart Brush—that work just like the Quick Selection tool and the regular Selection Brush, respectively. Only instead of merely selecting part of your photo, they also edit it as you brush. So you may be able to make targeted adjustments to different areas of your photo just by drawing a line over them. (The smart brushes don’t always work, but when they do, they’re truly amazing.) The smart brushes don’t alter your original image because they always put the changes they make on new layers, so it’s easy to edit the areas they affect.

This section explains how to correct exposure with the Smart Brush, but you have a whole menu of different things you can do with this tool: Change the color of someone’s jacket, apply different special effects, put a little lipstick on someone, convert an area to black and white—the list goes on and on. As a matter of fact, if you’ve been working in the Quick Fix window, you may have already met the Smart Brush, although it doesn’t go by that name there: The Whiten Teeth tool (Whitening Teeth) uses the Smart Brush to apply its effects.

Here’s how to put this nifty pair of tools to work:

In Expert mode, open a photo, and then activate the Smart Brush.

Click the tool’s icon in the Tools panel (it’s in the Enhance section: the wide house-painter’s brush just below the Red Eye Removal tool) or press F. Check the Tool Options area to be sure you’re using the regular Smart Brush. It shares its Tools panel slot with the Detail Smart Brush, which works like the Selection Brush in that it changes only the area directly under the cursor instead of automatically expanding your selection to include the whole object you brush over. For now, see if the regular Smart Brush is smart enough to select the area you want.

Choose the adjustment you want to apply.

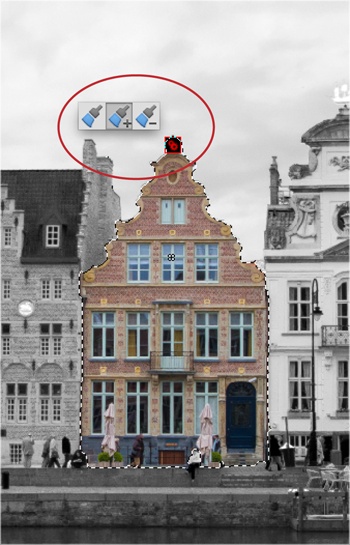

In the Tool Options area, click the thumbnail to the right of the brush icons. Then choose a category from the Presets drop-down menu and find an adjustment you like. (Both smart brushes have the same Tool Options settings, discussed on Correcting Color with a Brush. The important one is explained in Figure 7-3.)

Figure 7-3. The things you can do with the Smart Brush are grouped into the categories listed in this drop-down menu. Select different categories to see different presets. Each thumbnail image shows that option applied to a photo. For exposure issues, start by looking at the Lighting category (choose Lighting from the drop-down menu at the top of the panel). You can choose to make the area you’re about to paint darker or brighter, increase or decrease its contrast, or add a spotlight effect to it. Just put your cursor over each thumbnail to find the effect you want, and then click it to select it.Drag over the area you want to change.

This step is just like using the Quick Selection tool (Selecting with a Brush). You don’t need to make a careful selection, since Elements figures out which area it thinks you want to include and creates the selection for you. A simple line should do it. As you drag, Elements applies the adjustment you chose in step 2 (and an Adjustment layer appears in your Layers panel).

If necessary, tweak the selection.

If Elements didn’t quite select everything you want, then add to the selection by brushing again. (If you’ve got the Tool Options area’s Inverse checkbox turned on—more on that in a sec—then your selected area looks the same as the rest of the photo. If you’re doing an inverse black and white, for example, the colored area becomes black and white like the rest of the photo till you let go of the mouse button.)

If you still need to modify the selection, then use the selection-editing tools explained in Figure 7-4. If you’re really unhappy with the Smart Brush’s selection talents, then head back to the Tool Options area and switch to the Detail Smart Brush instead.

You can invert a selection by turning on the Inverse checkbox in the Tool Options area. Then what you brush over is excluded from your selection, and everything else is included. You can turn on the checkbox before or after using the Smart Brush, as long as it’s still the active tool. If you come back to the Smart Brush after using another tool, then you need to reactivate your Smart Brush selection by clicking the pin shown in Figure 7-4 before you can invert the selection.

Figure 7-4. Once you’ve used the Smart Brush, Elements puts a little icon called a pin (the red icon in the area circled here) in your photo to let you know that the selected region is now under the power of the Smart Brush. Click the pin to see a trio of icons (circled) that let you edit the selected area. From left to right, the icons are New Selection, “Add to Selection,” and “Subtract from Selection.” If you’re pressed for time, there’s an even quicker way to modify your selection: Just drag again to expand the area affected by the Smart Brush (or to use the same adjustment on another part of your photo). The Smart Brush always adds new areas when you click again; it doesn’t start a new selection each time you click the way the regular selection tools do. Alt-drag/Option-drag to remove changes from an area. You’ll see the pin anytime you activate the Smart Brush again, even after you’ve closed and saved your photo.Once Elements has selected the right area, adjust the effect (if necessary).

The Smart Brush gives you several ways to change what it’s done:

Choose a different adjustment. Head to the Tool Options area and choose a different adjustment (see step 2). Elements automatically updates your image.

Add another adjustment. If you want to tweak your image in a second way, head to the right end of the Tool Options area, click the little four-line square, and then choose Reset Tool. Then you can drag in your image again and the Smart Brush will put down an additional adjustment instead of just changing what you’ve already done. You can also use this technique to double up an effect—to add Lipstick twice, for instance—if you thought the first pass was too faint. Each Smart Brush adjustment gets its own pin, so if you have two Smart Brush adjustments in your photo, then you’ll have two pins, too. (Each pin is a different color.) You can add as many different adjustments as you like.

Change the settings for and adjustment you’ve already applied. Rather than adding another Adjustment layer to increase the effect, you can adjust the settings for the change you’ve already made. Double-click the adjustment’s pin in your image. Depending on the kind of adjustment you’ve made, a window or panel pops up showing the current settings so you can tweak the effect you’re brushing on. (Not all the Smart Brush adjustments have adjustable settings.) Since the Smart Brush uses Adjustment layers to make most of its changes, the available settings are the same as they would be if you had created a regular Adjustment layer. For example, if you’re using the Brighter option, as shown in Figure 7-3, then you get the settings for a Brightness/Contrast Adjustment layer.

Note

If you’re using certain of the Smart Brush’s black-and-white adjustments, you may not be able to edit them afterward. If you try, you’ll just see a weird message telling you that the layer was created in the full version of Photoshop, even though you know it wasn’t. You can delete the Adjustment layer or edit its layer mask, but that’s all. Also, if you apply effects (Effects) with the Smart Brush, once you’re done, the only edit you can make to them is to adjust the area they cover. (The thumbnails for effects look like a tree instead of the photo thumbnails you normally see—the presets in the Smart Brush’s Artistic category are all Effects, for example, although the presets in the Reverse Effects and Special Effects categories aren’t.)

When you’re happy with how things look, you’re done.

You can always adjust your Smart Brush edits later. Just activate the Smart Brush (click it in the Tools panel or press F) and the pin(s) reappear so you can easily change what you’ve done. To delete Smart Brush changes, go to the Layers panel and discard their layers (you can do this anytime, whether the Smart Brush is active or not). You can also edit a Smart Brush adjustment’s layer mask the way you’d edit any other layer mask, as described on Editing a Layer Mask. But usually it’s easier just to click the pin and then adjust your selection.

The Smart Brush is especially handy for projects like creating images that are part color and part black-and-white, or even for silly special effects like making an object look like it’s been isolated on a ’60s-style psychedelic background.

Tip

Check out the textures available for the Smart Brush—they’re handy for creating backgrounds for isolated objects. To find them, head to the Tool Options area, click the thumbnail image, and in the panel that appears, choose Textures from the Presets drop-down menu.

The Smart Brush has several Tool Options settings, but you usually don’t need to use them:

Presets. Click this thumbnail image for a panel of all the possible Smart Brush adjustments, grouped into categories.

Selection brushes. These three brush icons let you tell Elements how you want to adjust your selection:

—Click the top brush icon to add the same effect elsewhere in your photo. (Just clicking someplace else with the brush does the same thing. Be careful, though: The Smart Brush may think that the new area is a continuation of your previous selection, so it may combine the two. If that happens, try using a smaller brush.)

—Click the middle brush icon to put the Smart Brush in add-to-selection mode (the brush enters this mode automatically even if you don’t click this icon).

—Did the Smart Brush take in more area than you wanted? Click the bottom brush icon before brushing away what you don’t want, or just Alt-drag/Option-drag.

Size. If you have trouble getting a good selection, then try adjusting the size of your brush.

Brush Settings. Click this button to change the brush’s size, hardness, spacing, angle, or roundness. If you have a graphics tablet, the Size setting in this panel gives you a couple of ways to control brush size on the fly.

Inverse. If you want to apply the adjustment to the area you didn’t select with the Smart Brush, then turn on this checkbox.

Refine Edge. Click this button if you want to make the edges of your effect sleeker, or to extract the area you’ve edited for use elsewhere. Refining Selection Edges has details.

Tip

If you like the idea of the Smart Brush but never seem to find exactly the adjustments you want, or if you always want to change the settings you apply, then you can create your own presets, as described in the box on Making Smart Brush Presets.

Controlling the Colors You See

You want your photos to look as good as possible and to have beautiful, breathtaking color. Heck, that’s probably why you bought Elements. But now that you’ve got the program, you’re likely having a little trouble getting things to look the way you want. Does the following situation sound familiar?

What’s going on? The answer has to do with the fact that Elements is a color-managed program. That means Elements uses information about your monitor when deciding how to display images. Color management is the science of making sure that the color in an image is always exactly the same, no matter who opens the file or what kind of hardware she’s viewing it on or printing it with. If you think of all the different monitor and printer models out there, you get an idea of what a big job this is.

Graphics pros spend their whole lives grappling with color management, and you can find plenty of books about the finer points of it. At its most sophisticated, color management is complicated enough to make you curl up in the fetal position and swear never to create another picture. Luckily, Elements makes color management easy. Most of the time, you have only two things to deal with: monitor calibration and color space. The following pages cover both.

Note

There are a couple of other color-related settings for printing, but you can deal with those when you’re ready to print. Chapter 16 has the details.

Calibrating Your Monitor

Most programs pay no attention to your monitor’s color settings, but color-managed ones like Elements rely on the monitor’s profile—the information your computer stores about your monitor’s settings—when deciding how to display a photo onscreen or how to print it. If that profile isn’t accurate, the color in Elements won’t be either.

So you may need to calibrate your monitor, which is a way of adjusting its settings. A properly calibrated monitor makes all the difference in the world in getting great-looking results. If your photos look bad only in Elements or if your printed pictures don’t look anything like they do onscreen, then calibrating is a good way to begin fixing the problem.

Calibrating a monitor sounds intimidating, but it’s actually not that hard—some people think it’s even kind of fun. And it’s worth it, because afterward your monitor may look a thousand times better than you thought it could. Calibrating may even make it easier to read text in Word, for instance, because the contrast is better.

Your calibrating options are:

Use a colorimeter. This method may sound disturbingly scientific, but it’s actually the easiest and best. A colorimeter is a device with special software that does the calibrating for you; using such a device is much more accurate than calibrating by eye. For a long time, only pros could afford colorimeters, but these days, if you shop around, you can find something like the Spyder4EXPRESS or ColorMunki Smile for about $100. If you’re willing to spend more, you can find professional calibrators like the i1Display Pro or the ColorMunki Display. If you’re serious about controlling colors in Elements, using a colorimeter is by far your best option.

Note

The colorimeter’s software will probably ask you to set your monitor’s brightness and contrast before you begin calibrating, even though many modern monitors don’t have any easy way to adjust these settings. If you’re happy with your monitor’s current brightness and contrast, you can safely ignore this step. The next steps will ask you to choose a white point and gamma for your monitor. Unless you have a reason to use different settings, you usually want to set the white point to 6500 (Kelvin) and your gamma to 2.2.

Use a program. Whether you have a Windows computer or a Mac, you likely have some kind of software that can help you improve what you see:

—Windows: There’s a good chance that the drivers (software) for your computer’s graphics card include some kind of calibration tool. Go to Control Panel→“Appearance and Personalization”→Display→Calibrate Color to use the Windows calibrator.

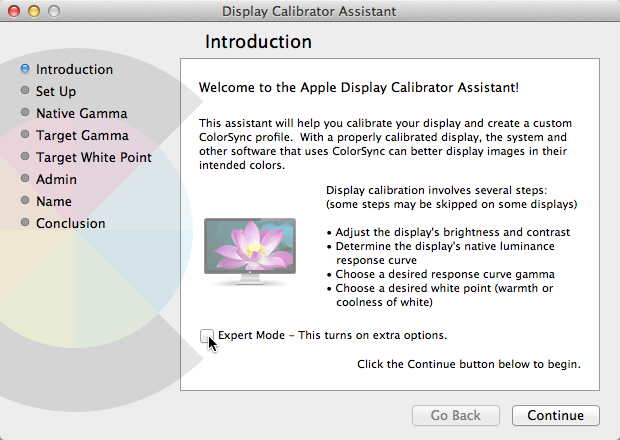

—Mac: If you go to System Preferences→Displays→Color→Calibrate, you can use Apple’s Display Calibrator Assistant to calibrate your monitor—sort of (see Figure 7-5). You can also find lots of calibration programs online, but most of them aren’t much, if any, better than the Assistant.

Figure 7-5. Using the Display Calibrator Assistant is pretty simple. You can do a basic calibration that sets your gamma and white point, or turn on the Expert Mode checkbox for a more elaborate color-balancing process. In Expert mode, you look at a series of apples (of course!) on a striped background and adjust things until the apples blend into the background. The problem is that it’s almost impossible to get accurate results from a visual calibration. The Display Calibrator Assistant is better than nothing, but a colorimeter is a much better option.

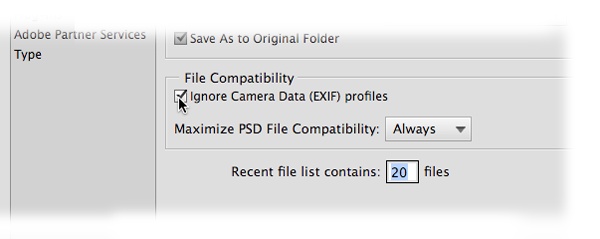

If your photos still look a little odd even after you’ve calibrated your monitor, you may need to turn on the Ignore EXIF setting in the Editor’s preferences; Figure 7-6 explains how.

Choosing a Color Space

The other thing you may need to do to get good color from Elements is to check which color space the program is using. Color spaces are standards that Elements uses to define colors. That may sound pretty abstruse, but they’re simply ways of defining what colors mean.

For example, when someone says “green,” what do you envision: a lush emerald color, a deep forest green, a bright lime, or something else? Choosing a color space helps make sure that everything that handles a digital file—Elements, your monitor, your printer, and so on—sees the file’s colors the same way. Over the years, the graphics industry has agreed on standards so that everyone has the same understanding of what you mean when you say “red” or “green”—as long as you specify which color space (set of standards) you’re using.

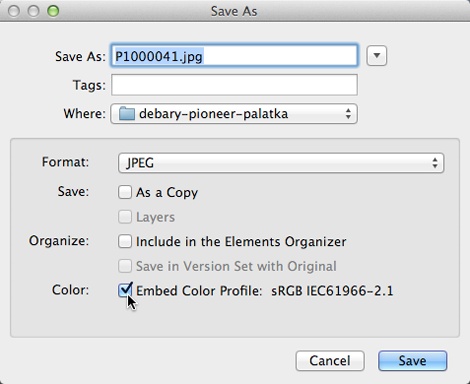

Elements gives you two color spaces to pick from: sRGB (also called sRGB IEC61966-2.1 if you want to impress your geek friends) and Adobe RGB. When you choose one, you’re telling Elements which set of standards you want it to apply to your photos.

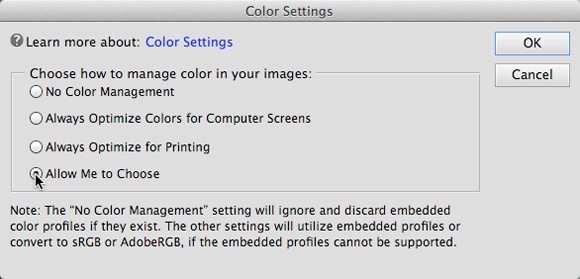

If you’re happy with the colors you see on your monitor in Elements and you like the prints you’re getting, you don’t need to make any changes. If, on the other hand, you aren’t satisfied with what Elements is showing you, you’ll probably want to modify your color space, which you can do in the Color Settings dialog box (Figure 7-7). Go to Edit→Color Settings or press Shift+Ctrl+K/Shift-⌘-K. Here are your choices:

No Color Management. This setting makes Elements ignore any information that your file already contains—like color-space data from your camera—and doesn’t attempt to add any color info to the file. (When you do a Save As, the Embed Color Profile checkbox offers you the option of embedding your monitor profile in the file. Don’t turn on this checkbox, since your monitor profile is best left for the monitor’s own use, and putting the profile into the file might cause trouble if you ever send the file someplace else for printing.)

Always Optimize Colors for Computer Screens. This option selects the sRGB color space, which is what most web browsers use; this is a good choice when you’re preparing graphics for the Web. Many online printing services also prefer sRGB files. This is the setting that’s selected when you first run Elements; you need to change it only if you want to use one of the others.

Always Optimize for Printing. This option uses the Adobe RGB color space, which is wider than sRGB, meaning it allows more color gradations. This is sometimes your best choice for printing—but not always. Don’t be afraid to try one of the other settings instead. Many home inkjet printers actually cope better with sRGB or no color management than with Adobe RGB.

Allow Me to Choose. This option assumes that you’re using the sRGB color space, but lets you assign either an Adobe RGB tag, an sRGB tag, or no tag at all (color tags are explained in a moment). After you select this option, each time you open a file that isn’t sRGB, you see the dialog box shown in Figure 7-7, which you can use to assign a different profile to the photo. Just save the image once without a profile (turn off the Embed Color Profile checkbox in the Save As dialog box), and then reopen it and choose the profile you want from this dialog box. Or, the box on Converting Profiles in Elements explains an easier way to convert a color profile if you need to make a change.

So what’s your best option? Once again, if everything looks good, leave things alone. Otherwise, for general use, you’re probably best off starting with No Color Management and then trying the other options if that doesn’t work.

When you save the file, Elements attempts to embed it with a color tag, info about the file’s color space—either Adobe RGB or sRGB. (This kind of tag isn’t related to the Organizer tags you read about in Chapter 2.) If you don’t want a color tag—also known as an ICC profile (ICC stands for International Color Consortium)—in your file, just turn off the Embed Color Profile checkbox before saving the file. Figure 7-8 shows where to find the profile information in the Save As dialog box, and how to turn the whole process off.

Note

When you’re working in a given color space (sRGB or Adobe RGB), if you open a file that’s tagged with a different color space, Elements will open the image in your current color space without telling you that it’s done so. That means you won’t know that there’s a mismatch between the file’s color tag and the color space you’re using. (If, on the other hand, you try to open a file in a color mode that Elements can’t handle, like CMYK, then Elements offers to convert it to a mode you can use.) For example, if you have an Adobe RGB file and you’re working in “Always Optimize Colors for Computer Screens” (which uses the sRGB color space), Elements doesn’t warn you about the mismatch the way early versions of the program did—it just opens the file. So if you consistently get strange color shifts when you open your Elements-edited files in other programs, check to see if there’s a profile mismatch between your images and Elements.

Using Levels

People who’ve used Elements for a while will tell you that the Levels command is one of the program’s most essential tools. You can fix an amazing array of problems simply by adjusting the level of each color channel in your images. Each color displayed on your monitor is composed of three channels: red, green, and blue. In Elements, you can make very precise adjustments by adjusting these channels separately.

Just as its name suggests, Levels adjusts the amount, or level, of each color in an image. You can make several different adjustments with Levels, from brightening a photo’s overall colors to fixing a color cast (Removing Unwanted Color has more about color casts). Many digital photo enthusiasts treat almost every picture they take to a dose of Levels because there’s no better way to spruce up the color.

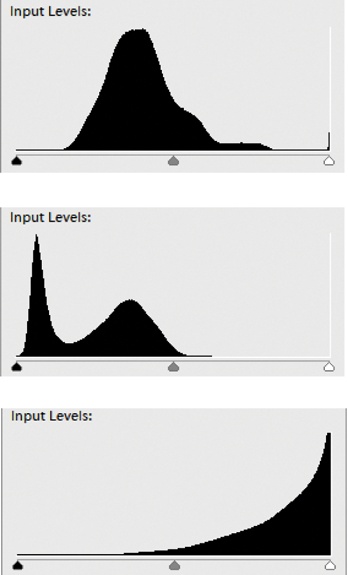

The way Levels works is fairly complex. Start by thinking of the possible ranges of brightness in any photo on a scale from 0 (black) to 255 (white). Some photos may have pixels in them that fall at both those extremes, but most photos don’t. Even the ones that do may not have the full range of brightness in each individual color channel. Most of the time, you’ll find some empty space at one or both ends of the scale.

When you use Levels, you tell Elements to consider the range of colors available in your photo as the total tonal range it has to work with, and Elements redistributes the image’s colors accordingly. Basically, you just get rid of the empty space at the ends of the scale of possibilities. This can dramatically change the color distribution in a photo, as you can see in Figure 7-9.

Fortunately, it’s much, much easier to use Levels than to understand it, as you know if you’ve tried Auto Levels in Quick Fix (Adjusting Exposure), a command that’s great for, well, quick fixes. But if you really need to massage an image, Levels has a lot more under the hood than you can access in Quick Fix. The next section shows you how to get at these settings.

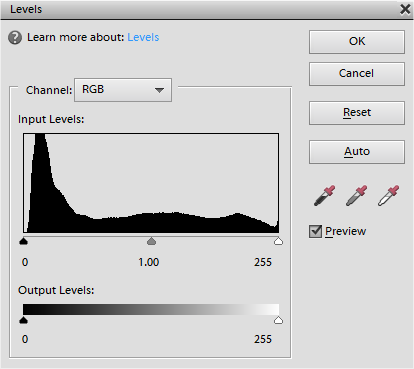

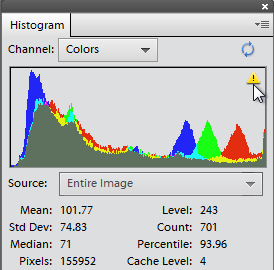

Understanding the Histogram

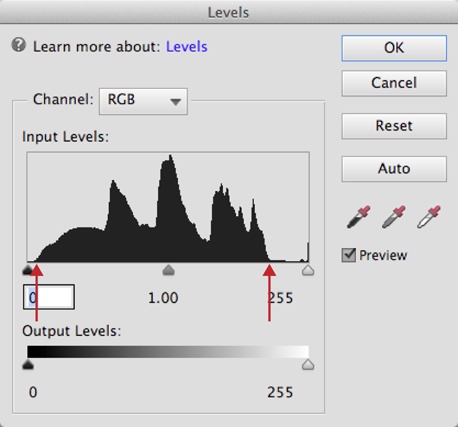

Before you get started adjusting Levels, you need to understand the heart, soul, and brain of the Levels dialog box: the histogram, visible in Figure 7-10. (You can call up this dialog box by pressing Ctrl+L/⌘-L.)

The histogram is the black bumpy mound in the middle of the dialog box. It’s really nothing more than a bar graph indicating the distribution of the colors in your photo—there’s just no space between the bars, which is why it looks like mountains.

From left to right, the histogram shows the brightness range from dark to light (the 0–255 range mentioned earlier in this section). The height of the “mountain” at any given point shows how many pixels in your photo have that particular brightness. You can tell a lot about a photo by where the mound is before you adjust the image, as Figure 7-11 explains.

Above the Levels dialog box’s histogram is the Channel menu. If you click it, you can choose to see a separate histogram for each individual color channel. You can adjust all three channels at once with the RGB setting, or change each channel separately for maximum control.

The histogram contains so much info about your photo that Adobe also makes it available in Expert mode in its own panel (Figure 7-12), so you can always see it and use it to monitor how you’re changing the colors in an image. Once you get fluent in reading Histogramese, you’ll probably want to keep this panel around.

The histogram is just a graph, and you don’t do anything to it directly. When you use Levels, you simply use the histogram as a guide to help you tell Elements what to consider the black and white points—that is, the darkest and lightest points—in your photo. (Remember, for these settings, you’re thinking in terms of brightness values, not shades of color.)

Once you’ve set these end points (you’ll learn how in a moment), you can adjust the image’s midtones—the tones in between that would appear gray in a black-and-white photo. If that seems complicated, it’s not—at least, not when you’re actually doing it. Once you’ve made a Levels adjustment, the next time you open the Levels dialog box, you’ll see that your histogram’s values now run the whole length of the scale because you’ve told Elements to redistribute your colors so that they cover the full dark-to-light range.

The next two sections show you—finally!—how to actually adjust an image with Levels.

Tip

Once you learn how to interpret Elements’ histograms, you can try your hand with your camera’s histogram (if it has one). Your camera’s histogram can be a big help in figuring out how well exposed your shot is going to be, or to check how you did after a shot. Alas, you’ll need to check your owner’s manual to figure out how to display the histogram on your particular camera.

Adjusting Levels: The Eyedropper Method

One way to adjust Levels is to set the image’s black, white, and/or gray points by using the eyedroppers in the Levels Adjustments panel. It’s quite simple—just follow these steps:

Bring up the Levels Adjustments panel by selecting Layer→New Adjustment Layer→Levels.

If you like, you can name the layer in the New Layer dialog box that appears, or just click OK to get on with it and create the layer. If you don’t want a separate layer for your Levels adjustment, go to Enhance→Adjust Lighting→Levels or press Ctrl+L/⌘-L instead. (You’ll get a dialog box instead of the panel, but it works the same way.) But making the Levels changes on an Adjustment layer gives you more flexibility for making future changes.

If necessary, move the Adjustments panel or the Levels dialog box out of the way so you have a good view of your photo.

The dialog box loves to plunk itself down smack in the middle of the most important part of your image. Just grab its top bar and drag it somewhere else.

In the Adjustments panel or Levels dialog box, click the black eyedropper.

In the Adjustments panel, from top to bottom, the eyedroppers are black, gray, and white. In the dialog box, they’re arranged from left to right instead.

Move your cursor over your photo and click an area that should be black.

Should be, not is. That’s a mistake lots of people make the first time they use the Levels eyedroppers: They click a spot that’s the same color as the eyedropper rather than one that ought to be that color. For instance, if your photo includes a wood carving that looks black but that you know is actually dark brown instead, that’s a bad place to click. Try clicking a black coffee mug or belt instead. This process is called “setting a black point.”

Repeat with the other eyedroppers for their respective colors.

Now select the white eyedropper and then click a spot that should be white (like maybe a cloud that’s a little off-white now), and then use the gray eyedropper to click one that should be gray; doing so sets your white and gray points. That’s the way this process is supposed to work, anyway, but you can’t always use all the eyedroppers in a given photo. Experiment to see what gives you the best-looking results.

If you’re using the dialog box, when you’re happy with what you see, click OK.

If you’re working with the Adjustments panel, you don’t have to do anything: Elements has already applied your changes, so you’re done.

See, it’s not so hard. If you mess up, just click the dialog box’s Reset button to start over again. In the Adjustments panel, click the word “Reset” at the panel’s bottom right.

Adjusting Levels: The Slider Method

The eyedropper method works fine if your photo has spots that should be black, white, or gray, but sometimes your pictures don’t have any of these colors. Fortunately, the Levels sliders give you yet another way to apply Levels. This is by far the most popular method, and it gives you maximum control over your colors.

In the Levels Adjustments panel or dialog box (press Ctrl+L/⌘-L to open it), right below the histogram, are three little triangles called input sliders. The left slider sets the black point in your photo, the right slider sets the white point, and the middle slider adjusts the midtones (grays). You just drag them to make changes to the color levels in your photo, as shown in Figure 7-13.

When you move the left input slider, you tell Levels, “Take all the pixels from this point down and consider them black.” With the right slider, you’re saying, “Make this pixel and all higher values white.” The middle slider adjusts the brightness values that are considered medium gray. All three adjustments improve the contrast of your image.

Tip

If there are small amounts of color data (flat lines) at the ends of the histogram, or if all the data is clumped in the middle of the graph, watch your photo as you move the left and right input sliders to decide how far in you should drag them. Moving them all the way in may be too drastic. Your own taste should always be the deciding factor when adjusting a photo.

Here’s the easiest way to use the Levels sliders:

Bring up the Levels dialog box or the Levels Adjustments panel.

Use one of the methods described in step 1 of the eyedropper method (Adjusting Levels: The Eyedropper Method). If necessary, move the dialog box or panel so you’ve got a clear view of your photo.

Grab the black input slider (the one below the left end of the histogram) and drag it to the right, if necessary.

Move it over until it’s under the farthest-left part of the histogram that has a mound in it. For the histogram in Figure 7-13, for example, you’d move the left slider just a tiny bit, to where the left red arrow is. (Incidentally, although you’re adjusting the image’s colors, the Levels histogram is always black and white—you don’t see any color in the dialog box itself.)

You may not need to move the black slider at all if there’s already a good bit of data at the left end of the histogram. You don’t have to adjust all the sliders for every photo.

Grab the white slider (the one on the right) and drag it left, if necessary.

Bring it under the farthest-right area of the histogram that has a mound in it.

Now adjust the gray slider.

This is the midtones slider, and it adjusts—you guessed it—the midtones of your image. Move it back and forth while watching your photo until you like what you see. This slider has the most impact on the overall result, so take some time to play with it.

Tip

If you know the numerical value of the pixels you want to designate for any of these settings, you can type that information into the unlabeled input levels boxes below the histogram. You can set the gray value from 0.10 to 9.99 (it’s set to 1.00 automatically), and the other two boxes anywhere from 0 to 255.

If you’re using the Levels dialog box, click OK to let Elements know you’re done.

You can adjust the whole image at once or each color channel individually. The most accurate method is to open the Levels dialog box and then choose each color channel in turn from the Channel drop-down menu. Adjust the end points for each channel, and then choose RGB from the menu and tweak just the midtones (gray) slider.

The last controls you may want to use in the Levels dialog box or Levels Adjustments panel are the Output Levels sliders, which work roughly the same way as the brightness and contrast controls on your TV. Moving these sliders makes the darkest pixels darker and the lightest pixels lighter. Image pros call this process “adjusting the tonal range of a photo.”

Adjusting Levels can improve almost every photo, but if your image has a bad color cast—if it’s too orange or too blue, say—you may need something else. The next section explains how to get rid of color like that.

Removing Unwanted Color

It’s not uncommon for an otherwise good photo to have a color cast—that is, to have all its tonal values shifted so it’s too blue, like Figure 7-14, or too orange.

Elements gives you several ways to correct color-cast problems:

Auto Color Correction doesn’t give you any control over its changes, but it often does a good job. To use it, go to Enhance→Auto Color Correction or press Shift+Ctrl+B/Shift-⌘-B.

The Raw Converter (The Raw Converter) may be the easiest way to fix color problems, though it works only on raw, JPEG, and TIFF files. Just run your photo through the Raw Converter and adjust its white balance as described on Rotating, Straightening, and Cropping.

Levels gives you the finest control of all. You can often eliminate a color cast by adjusting the image’s individual color channels (as explained in the previous section) till the unwanted color is gone. The drawbacks are that Levels can be very fiddly for this sort of work; sometimes this method doesn’t work if the problem is severe; and it can take much longer than the other methods.

Remove Color Cast is a command designed to correct a color cast with one click. The next section explains how to use it.

The Photo Filter command gives you much more control than the Remove Color Cast command, and you can apply Photo Filters as Adjustment layers, too. See Photo Filter for details.

The Average Blur filter, used with a blend mode, can fix color casts, too. As you’ll read on Color Correcting with the Average Blur Filter, it’s something like creating a custom photo filter.

The Adjust Color for Skin Tone feature makes Elements adjust a photo based on the skin colors of people in the image. In practice, this adjustment is often more likely to introduce a color cast than to correct one, but if your photo has a slight bluish cast that’s visible in the subject’s skin (as explained on Adjusting Skin Tones), it may do the trick. This option works best for slight, annoying casts that are too subtle for the other techniques in this list.

Note

If you’re a fan of Color Variations from older versions of Elements, sorry, but Adobe removed that feature back in Elements 12.

You can use any of these methods, but a good bet is to start with Levels and then move on to the Remove Color Cast or Photo Filter command. To practice any of the fixes you’re about to learn, download the photo crossover.jpg from this book’s Missing CD page at www.missingmanuals.com/cds.

The Remove Color Cast Command

This command uses an eyedropper to adjust the colors in a photo based on the pixels you click. With this method, you show Elements where a neutral color should be. As you saw in Figure 7-14, Remove Color Cast can make a big difference with just one click. To use it:

Go to Enhance→Adjust Color→Remove Color Cast.

Your cursor should change to an eyedropper when you move it over your photo. If it doesn’t, in the Remove Color Cast dialog box, click the eyedropper icon.

Click an area that should be gray, white, or black.

You only have to click once in your photo for this feature to work. As with the Levels eyedropper tool, click an area that should be gray, white, or black (as opposed to an area that’s currently one of these colors). If the image you’re trying to fix has several such areas, try clicking different spots in the photo. Just click Reset in the dialog box between each click on the photo until you find the spot that gives you the most natural-looking color.

Click OK in the dialog box.

Remove Color Cast works pretty well if your image has areas that should be black, white, or gray—even if they’re tiny. If your image doesn’t have any areas that should be one of those colors, consider using the Photo Filter command instead (Layer Masks).

Choosing Colors

So far, the color corrections you’ve read about in this chapter have all done most of the color assigning for you. But a lot of the time, you want to tell Elements what colors to work with—like when you’re selecting the color for a Background or Fill layer, or when you want to paint on an image.

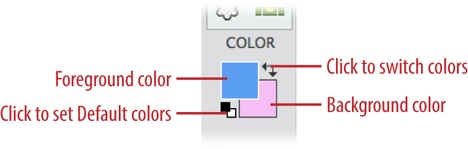

Although you can use any of the millions of colors your screen can display, Elements loads only two colors at a time. You choose these colors by using the foreground and background color squares at the bottom of the Tools panel (see Figure 7-15).

Foreground and background mean just what they sound like—use the foreground color with tools like the Brush or the Paint Bucket, and the background color to fill in backgrounds. You can include as many colors in your images as you want, of course, but you can only use two at any given time.

The color-picking tools at the bottom of the Tools panel let you control the color you’re using in a number of different ways:

Reset default colors. Click the tiny black and white squares below the foreground square to return to the standard settings: black for the foreground color and white for the background color. (Pressing the D key does the same thing.)

Swap foreground and background colors. Click the little curved two-headed arrow above the color squares to make the background color into the foreground color, and vice versa. This is helpful when you’ve inadvertently made your color selection in the wrong box. Say you set the foreground color to yellow, but you actually meant to make the background color yellow; just click these arrows or press X and you’re all set.

Change either color square to whatever color you want. Click either square to call up the Color Picker (explained on The Color Picker) to make your new choice. There’s no limit on the number of colors you can select in Elements. (Well, technically there is, but it’s in the millions, so you should find enough choices for anything you want to do.)

You have a few different ways to select foreground and background colors. The next few sections explain how to use the Color Picker, the Eyedropper tool, and the Color Swatches panel.

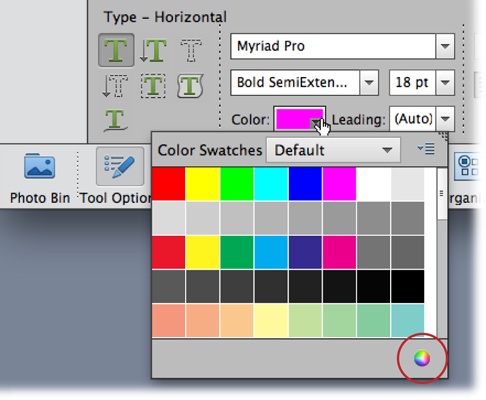

When working with some of Elements’ tools, like the type tools, you can also choose a color in the tool’s Tool Options area. Adobe knows that, given a choice, most people prefer to work with either Color Swatches or the Color Picker, so it’s come up with a way to accommodate both camps, as shown in Figure 7-16.

Tip

Adobe gives you other ways to create colors. You can go to https://kuler.adobe.com/create/color-wheel and use Adobe Kuler, which also comes in app form for your iOS gadget. And if you have an iPad, you’ve got yet another way to create colors for Elements: Adobe’s Color Lava app lets you use your fingers to blend colors and then send them to Elements. Head to www.photoshop.com/products/mobile/colorlava for more info. (That web page says you need Photoshop to use Color Lava, but it works with Elements, too.)

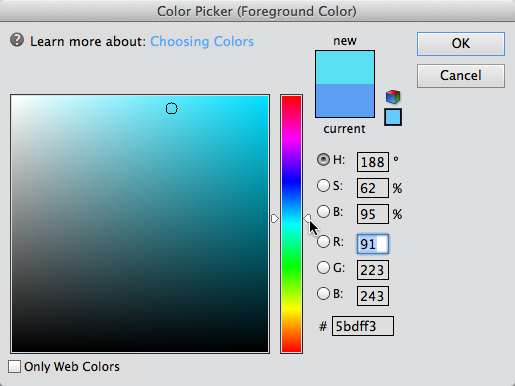

The Color Picker

Figure 7-17 shows the Color Picker, which has an intimidating number of options, but most of the time you don’t need them all. Choosing a color is as simple as clicking wherever you see the color you want. Here’s how:

In the Tools panel, click the foreground or background color square.

Elements launches the Color Picker. Some tools—like the Paint Bucket (The Pencil Tool) and the Selection Brush’s mask color option—also use the Color Picker. It works the same way no matter how you get to it.

Choose the color range you want to select from.

Use the vertical Color slider in the middle of the dialog box to slide through the spectrum until you see the color you want in the big, square Color field.

In the Color field, click the spot where you see the exact shade you want.

You can keep clicking around and watch the color in the window’s “new” box change to reflect what you click. The “current” box shows your original color for comparison.

Click OK.

The color you selected now appears in the foreground or background square in the Tools panel (depending on which one you clicked in step 1).

That’s the basic way to use the Color Picker. The box below explains how to enter a numeric value for a color (if you know it) and how to change which shades the Color Picker offers you.

Note

You’re not limited to Elements’ Color Picker. If you prefer, you can use your operating system’s Color Picker instead (maybe you’re used to working with the Windows Picker, for example). Here’s how:

Windows: In the Elements Editor, go to Edit→Preferences→General. At the top of the dialog box, set the Color Picker menu to Windows. From then on, when you click a color square in Elements, the Windows Color Picker opens up looking pretty feeble, with just a few colored squares and some white ones. But if you click Define Custom Colors, it expands, giving you access to most of the same features as in the Adobe picker. (The plain white squares are like little pigeonholes where you can save your color choices.)

Mac: Go to Photoshop Elements Editor→Preferences→General and, from the Color Picker menu at the top of the dialog box, select Apple. You may prefer Apple’s color picker if you like to choose colors from a color wheel. There’s even a fun view where you choose from a box of crayons. You can save colors in Apple’s color picker by dragging them from the Color field at the top of the window onto the squares at the bottom. Then click a square to choose that color the next time you want it.

The Color Picker/Eyedropper Tool

If you’ve ever repainted your house, you’ve probably had the frustrating experience of spotting the exact color you want to use, but not having a way to capture that color. That’s one problem you’ll never run into in Elements thanks to the handy Eyedropper tool, which lets you sample any color on your monitor and make it your foreground color. If you can get a color onto your computer, Elements can grab it.

Note

Technically, this tool used to go by the sensible name of Eyedropper, but for some incomprehensible reason Adobe now calls it the Color Picker tool even though it has nothing to do with the Color Picker described on The Color Picker, at least not directly. To avoid confusion, this book calls this tool by its old name: the Eyedropper tool. If you go looking for it in the Tools panel, just look for the eyedropper icon in the Draw section.

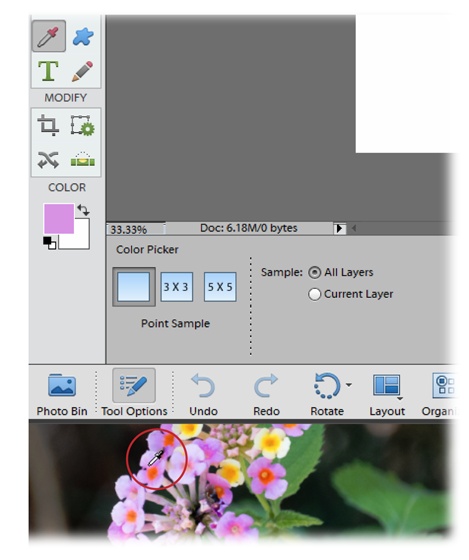

Sampling a color (that is, snagging it for your own use) couldn’t be simpler with the Eyedropper: Just move your cursor over the color you want, and then click. It even works on colors that aren’t in Elements, as explained in Figure 7-18. Sampling is perfect for projects like scrapbook pages where you want to use, say, the color from an event program cover as a theme color for the project. Just scan the program and then sample the color with the Eyedropper tool.

The Eyedropper is one of the easiest tools to use:

Click the eyedropper icon in the Tools panel or press I.

Your cursor changes into a tiny eyedropper.

Put your cursor over the color you want to sample.

If you want to watch the color in the foreground color square change as you move the Eyedropper tool around, hold the mouse button down.

If you have a layered file, you can use the radio buttons in the Tool Options area to tell Elements whether to sample from all the image’s layers or just the active layer.

When your cursor is over the color you want, click or let go of your mouse button.

Elements loads your color choice as the foreground color so it’s ready to use. (To set the background color instead, Alt-click/Option-click the color you want.)

To keep the new color around so you can use it later without having to get the Eyedropper out again, save it in the Swatches panel. The next section teaches you how.

Tip

Unless you tell it otherwise, the Eyedropper tool selects the color of the exact pixel you click. But since there may be some slight pixel-to-pixel variation in a color, you can set it to sample a little block of pixels instead and then average them. In the Eyedropper’s Tool Options area, you can choose between the exact pixel you click (Point Sample), a 3-pixel square average, or a 5-pixel square average; just click the option you want. You can also do this by right-clicking/Control-clicking your image when the Eyedropper tool is active, and then choosing from the pop-up menu. Oddly enough, this setting also applies to the Magic Wand (The Magic Wand). Change it here and you change it for the Wand, too.

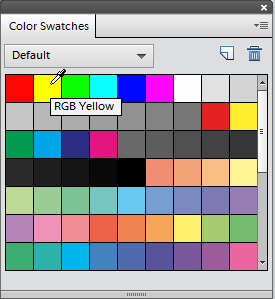

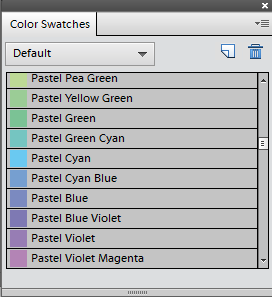

The Color Swatches Panel

The Color Swatches panel holds several preloaded groups of colors you can choose from. To call it up, go to Window→Color Swatches. You can park it in the Panel Bin just like any other panel or leave it floating on your desktop. When you’re ready to choose a color, just head to this panel and click the swatch you want, and it appears in the Tools panel’s foreground color square or in the color box of the tool you’re using.

The Color Swatches panel is really handy when you want to keep certain colors at your fingertips. For instance, you can put your logo colors into it, and then you always have them available for any graphics or ads you create in Elements.

Elements starts you off with several different libraries (groups) of color swatches; click the drop-down menu at the top of the panel to see them all. Any swatch you create using the techniques in the next section appears at the bottom of the current library; you can save it there or create your own swatch libraries.

Using the Color Swatches panel to select your foreground or background color is as easy as using the Eyedropper tool; Figure 7-19 shows you how. And Figure 7-20 explains how to change the way the panel displays swatch info.

Saving Colors in the Swatches Panel

You can save any colors you’ve picked using the Color Picker or Eyedropper tool. (If you don’t save them, you’ll lose them as soon as you select a different swatch library or close the panel.) After sampling a color, you can save it as a swatch in one of two ways: Click the New Swatch icon at the top of the Color Swatches panel (it looks like a piece of paper with a folded corner) or click the four-line square in the panel’s upper right, and then choose New Swatch. Either way, a window appears where you can name and save your new swatch.

Your new swatch appears at the bottom of the current swatch library, and its name shows up as a pop-up label when you put your cursor over it in the panel. You can rename the swatch by right-clicking/Control-clicking it, and then choosing Rename Color Swatch. To delete a swatch that you’ve saved, Alt-click/Option-click it or drag it to the trashcan icon in the Color Swatches panel.

If you want to keep your swatches separate from the ones that come with Elements, you can create your own swatch libraries. To do that, click the four-line square at the top right of the Color Swatches panel and pick Save Swatches. Then give the new library a name and save it.

You can also find downloadable swatch libraries online (see Stuff from the Internet for some suggestions of where to look). The best way to load these into Elements is to use the Preset Manager, explained on Stuff from the Internet.

Sharpening Images

Digital cameras are wonderful, but it’s often hard to tell how well-focused your photos are until you download them to a computer. And because of the way cameras’ digital sensors process information, most digital image data needs to be sharpened.

Sharpening is an image-editing trick that makes pictures look more clearly focused. Elements includes some almost miraculous tools for sharpening images. (It’s pretty darned good at blurring them, too, if that’s what you want; see Gaussian Blur: Drawing Attention to an Object.) This section explains your options.

Unsharp Mask

Although this feature sounds like the last thing you’d ever want to use on a photo, Unsharp Mask reigned as the Supreme Sharpener for generations of image correction, despite having the most counterintuitive name in all of Elements.

To be fair, it’s not Adobe’s fault. “Unsharp mask” is an old darkroom term, and it actually does make sense if you know how our film ancestors used to improve a picture’s focus. It refers to a complicated darkroom technique that involved making a blurred copy of the photo at one point in the process.

For several versions of Elements, Unsharp Mask ranked right up there with Levels as a contender for most useful tool in Elements, and some people still think it’s the best way to sharpen photos. Figure 7-21 shows how much a little Unsharp Mask can do for pictures.

To use Unsharp Mask, first finish all your other corrections and changes. A good rule of thumb for sharpening is “last and once.” That’s because Unsharp Mask (or any sharpening tool, for that matter) can undermine other adjustments you make later on, so always make sharpening your last step. And repeatedly applying sharpening can degrade your image’s quality.

Tip

An exception to the rule about sharpening only once is when you’re converting raw images (The Sharpen Tool): You can usually sharpen them both in the Raw Converter and then again as a last step in the Editor without causing problems.

If you’re sharpening an image that has layers, be sure the active layer has something in it. (Applying sharpening to a Levels Adjustment layer, for example, won’t do anything.) Also, perform any file-format conversions before sharpening. Finally, you may want to sharpen a duplicate layer just in case you decide to undo your changes later; press Ctrl+J/⌘-J to create the duplicate layer.

Note

It’s helpful to understand just exactly what Elements does when it “sharpens” a photo. It doesn’t magically correct the focus. As a matter of fact, it doesn’t really sharpen anything. Instead, it increases the contrast where colors meet, giving the impression of crisper focus. So while Elements can dramatically improve a shot that’s a little soft, it can’t fix that old double exposure or a shot where the subject is just a blur of motion.

When you’re ready to apply Unsharp Mask:

Go to Enhance→Unsharp Mask.

You can use Unsharp Mask in either Expert or Quick Fix mode.

In the Unsharp Mask dialog box, adjust the settings until you like what you see.

Move the sliders until you’re happy with your photo’s sharpness (the following list explains what each one does). In the preview part of the dialog box, you can zoom in and out and grab the photo to adjust which part you see. It’s also a good idea to drag the dialog box off to the side so that you can see the changes in your actual image. (You get the most accurate look at how you’re affecting the image if you set the view to 100 percent or Actual Pixels.)

When you’re satisfied, click OK.

The Unsharp Mask sliders work much like other tools’ sliders:

Amount tells Elements how much to sharpen, in percent terms. A higher number means more sharpening.

Radius lets Elements know how far from an edge (a place where two colors meet) it should look when increasing the contrast.

Threshold controls how different a pixel needs to be from the surrounding pixels before Elements considers it an edge and sharpens it. If you leave this setting at zero—which is the standard setting—Elements sharpens all the image’s pixels.

There are many, many different schools of thought about where to move the sliders or which values to plug into each box. Whatever works for you is fine. The one thing you want to watch out for is oversharpening. Figure 7-22 explains how to know if you’ve gone too far.

You’ll probably need to experiment a bit to find out which settings work best for you. Photos you plan to print usually need to be sharpened to an extent that makes them look slightly oversharpened on your monitor, so you may want to create two separate versions of your photo: one for onscreen viewing and one for printing. The Organizer’s version sets (Saving Your Work) are great for keeping track of multiple copies like this.

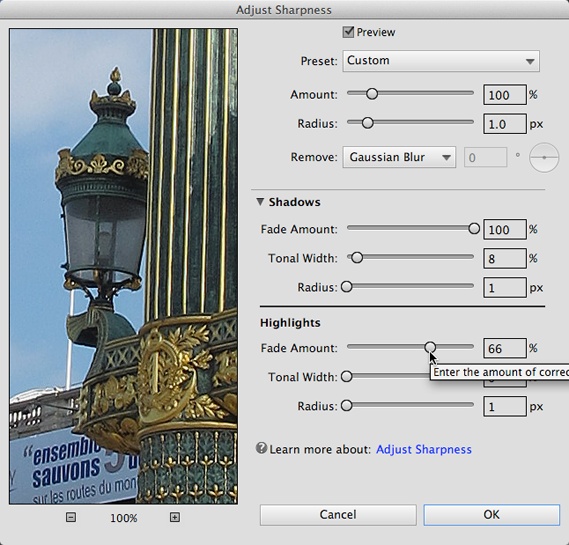

Adjust Sharpness

The Unsharp Mask technique was around long before digital imaging, and a lot of people (including the folks at Adobe) have been thinking that, in the computer age, there’s got to be a better way to sharpen. Happily, there is. The latest tool in the war on poor focus is Adjust Sharpness. In Elements 13, this feature is completely new under the hood and it gives you even more control over sharpening than you had in previous versions of Elements.

Unsharp Mask (described in the previous section) helps boost a photo’s sharpness by using a process something like reducing Gaussian blur (Gaussian Blur: Drawing Attention to an Object). Problem is, Gaussian blurring is rarely the cause of a picture’s poor focus, so there’s only so much Unsharp Mask can do. In real life, blurry photos are usually caused by one of two things:

Lens blur. Your camera’s prime focal point isn’t directly over your subject, or your lens isn’t quite as sharp as you’d like it to be.

Motion blur. You moved the camera—or your subject moved—while you pressed the shutter button.

Adjust Sharpness is as easy to use as Unsharp Mask, and it gives you settings to correct all three kinds of blur—Gaussian, lens, and motion. And in Elements 13, you get some new settings to help you sharpen your photos even more accurately.

When you first open the Adjust Sharpness dialog box, its settings are almost identical to those of Unsharp Mask. It’s the extra things Adjust Sharpness can do that make it a more versatile feature. Here’s how to use it:

Make sure the layer you want to sharpen is the active layer.

See Chapter 6 if you need a refresher on layers.

Go to Enhance→Adjust Sharpness.

You can reach this menu item from either Expert mode or Quick Fix.

In the Adjust Sharpness dialog box, tweak the various settings.

As shown in Figure 7-23, the dialog box gives you a decently sized preview. It’s usually best to stick with 50 or 100 percent zoom (use the + and – buttons below the preview to zoom) for the most accurate view. The other settings are explained in detail after this list.

When you like the way your photo looks, click OK.

Figure 7-23. The Adjust Sharpness dialog box in Elements 13 includes a number of new controls that let you micromanage what happens to sharpening in the dark and very light areas of your photos, both of which can be major problem areas with basic sharpening. Just click the flippy triangle to the left of the words “Shadows / Highlights” to expand the window so you can see these extra controls.

Near the top of the Adjust Sharpness dialog box is the Preset drop-down. You can safely ignore that menu for now, although it can come in handy if you have a bunch of images with similar sharpness problems; Creating and Saving Presets has the details.

The first two sliders in the Adjust Sharpness dialog box, Amount and Radius, work exactly the same way they do in Unsharp Mask (Unsharp Mask). Here’s what the other settings do:

Reduce Noise. Sharpening often brings out hidden noise (graininess) in photos. If sharpening your photo made it noisier, use this setting to bring it back down. Although this setting is supposed to be smart enough to leave the edges of objects in your photos sharp and only go after noise, you should still be careful—if you get too aggressive with this slider, you can melt away all the crispness you just added to your image. Nudge this slider very gently, a little at a time, and keep checking the results in your document window, not just in the dialog box’s preview area.

Remove. This is where you choose what kind of fuzziness to fix: Gaussian, lens, or motion blur. If you aren’t sure which you want, try all three in turn and see which works best.

Angle. If you’re dealing with motion blur, you can improve your results by telling Elements the angle of the motion. For example, if your grip on the camera slipped, the direction of motion would be downward. Move the line in the little circle or type a number in degrees to approximate the angle. (It’s awfully tricky to get the angle exactly right, so you may find it easier to sharpen without messing with this setting.)

Tip

Although the Amount and Radius settings in the Adjust Sharpness dialog box control the same things as they do in Unsharp Mask, that doesn’t necessarily mean that you can just plug your favorite Unsharp Mask settings into the Adjust Sharpness dialog box and get the same results. You may prefer very different numbers for these settings for the two features.

Those are the settings you use for most everyday sharpening, but new in Elements 13, the dialog box also gives you a bunch of extra settings to help in more difficult situations.

Sometimes it can be tricky to get consistent sharpening across the whole tonal range of an image, so Adobe added a Shadows/Highlights section to the Adjust Sharpness dialog box. You can now adjust the settings for very dark and very light areas separately. Just click Shadows/Highlights to expand that section, and you’ll see two additional sets of sliders, one for shadows and one for highlights. Both sections have the same three settings:

Fade Amount determines how much sharpening Elements applies to either the dark or light areas of your image (depending on whether you’re adjusting this setting in the Shadows or Highlights section). It goes from 0% (no different from how the rest of the image is sharpened) to 100%.

Tonal Width tells Elements how wide a range of brightnesses to affect. This slider starts off at 50%. Move it to the left to restrict Elements to a smaller tonal range (darker areas for the Shadows slider, brighter areas for the Highlights slider), or to the right for a larger range of tones. For example, moving the Shadows slider to the left would restrict sharpening to darker tones, while moving it to the right would include brighter areas. In the Highlights section, moving this slider to the left restricts sharpening to lighter tones, while moving it to the right starts including tones more toward the midrange.

Radius tells Elements how large an area around each pixel it should consider when looking for areas to sharpen. If you leave this slider set at 1, that’s the narrowest area available. To tell Elements to look farther, move this slider to the right.

Using these sliders lets you get attractive sharpening in the difficult outer tonal ranges, especially dark or shadowed areas, which have been notoriously difficult to work with in the past.

Tip

If you’re working in the Adjust Sharpness dialog box and don’t like the way your changes are affecting your image, click the dialog box’s Preset menu and choose Default to return the dialog box to its original settings.

Creating and Saving Presets

If you have a big batch of images that you know are going to need the same sharpening settings—like a dozen different shots of a model taken using your camera’s burst mode or a motor drive—you can speed things up by adjusting one image with the Adjust Sharpness dialog box and then saving those settings as a preset.

The dialog box’s Preset drop-down menu makes it easy to work with presets:

Create a preset. Just move the Adjust Sharpness dialog box’s sliders to where you want them. When you’ve got everything sharpened just right, click the Preset menu, and then choose Save Preset. In the window that opens, name your preset and then save it. Don’t change the save location Elements suggests or the program won’t be able to find your preset. (In Windows, they go in C:\Users\[user]\AppData\Roaming\Adobe\Photoshop Elements\13.0\Presets\Smart Sharpen. In OS X Elements saves presets to [your hard drive]→Library→Application Support→Adobe→Adobe Photoshop Elements 13→Presets→Smart Sharpen.) After that, the name of your preset appears in the Preset menu.

Use presets created by others. You aren’t limited to your own presets. If someone else creates a preset and sends it to you, just open the Preset drop-down menu, choose Load Preset, and then navigate to the file. (You can also use this option to find your own presets if for some reason they don’t appear in the menu.

Remove presets. If you want to get rid of a preset, head to the Preset menu and choose Delete Preset; in the window that opens, choose the doomed preset from the pull-down menu, and then click Delete. If you want to get rid of all your custom presets, choose All Presets instead.

Some people who’ve used Smart Sharpening in the full-featured Photoshop swear they’ll never go back to Unsharp Mask. Adjust Sharpness is Elements’ version of Smart Sharpening, so give it a try and see if you, too, like it better than Unsharp Mask. To give you an idea of the difference between the two methods, Figure 7-24 shows the dog from Figure 7-21 again, only this time with a dose of Adjust Sharpness instead of Unsharp Mask. Some people consider Adjust Sharpness too darned fiddly to use, so feel free to go back to Unsharp Mask if it works better for you. (And, Mac folks, don’t forget that you also have the option of sharpening in Preview [Whitening Teeth]).

The High-Pass Filter

Unsharp Mask is definitely the traditional favorite, and Adjust Sharpness is the latest thing in sharpening, but there’s an alternative method that many people prefer because you apply it on a dedicated layer, which means you can lessen the effect later by adjusting the layer’s opacity. Moreover, you can use this method to punch up the colors in a photo as you sharpen. It’s called high-pass sharpening.

All sharpening methods have their virtues, and you may find that you choose a technique according to the content of your photo. Try the following procedure by downloading the photo tiles.jpg from this book’s Missing CD page at www.missingmanuals.com/cds:

Open a photo and make sure the layer you want to sharpen is the active layer.

Duplicate the active layer by pressing Ctrl+J/⌘-J.

If you have a multilayered image and you want to sharpen all the layers, first flatten the image or use the Stamp Visible command (see the box on Stamp Visible) so everything is on one layer.

Your photo now looks like the victim of a mudslide, buried in featureless gray. Don’t panic—that’s what’s supposed to happen. You’ll restore the color in step 6.

In the High Pass dialog box, move the slider until you can barely see the outline of your subject.

Usually that means picking a setting between roughly 1.5 and 3.5. If you can see colors, your setting is probably too high. (If you can’t quite eliminate every trace of color without totally losing the subject’s outline, a little bit of color is OK.) Keep in mind that the edges you see through the gray are the ones that will get sharpened the most. Use that as your guide for how much detail to include.

Click OK to close the High Pass dialog box.

At the top left of the Layers panel, use the unlabeled drop-down menu to set the new layer’s blend mode to Overlay.

Ta-da! Your subject is back again in glowing, sharper color, as shown in Figure 7-25.

Figure 7-25. Left: A closeup look at the original photo. Right: High-pass sharpening using the Vivid Light blend mode makes the colors stand out more, but it also makes all the tiles a bit coarser and rougher looking than they were in the original. For this technique, you can use any of the blend modes in the group with Overlay except Hard Mix and Pin Light. Vivid Light can make colors pop, but watch out for sharpening artifacts (page 272), since they’ll be more vivid, too. Overlay gives you a softer effect.

Tip

There’s yet another way to create “pop” in photos: the Raw Converter’s Clarity setting (Saving Your Settings), which sharpens and enhances contrast. (If you know what “local contrast enhancement” means, this setting does something similar.) You can use it on raw, JPEG, and TIFF files. It’s especially useful for clearing haze from shots.

The Sharpen Tool

Elements also gives you a dedicated Sharpen tool for working on specific areas of a photo rather than the entire image. It’s a special brush that sharpens just the areas you drag it over; Figure 7-26 shows it in action. To get to it, click the Blur tool’s icon in the Tools panel or press R, and then, in the Tool Options area, choose the Sharpen tool (the triangle).

The Sharpen tool has some of the same Tool Options settings as the Brush tool (see Picking and Using a Basic Brush for more about brush settings), as well as a few all its own:

Mode lets you increase the visibility of an object’s edge by choosing from several different blend modes; Normal typically gives the most predictable results.

Brush. You can choose a brush style here, but usually the one Elements selects is OK.

Size. You need to be fairly precise about the size of the brush cursor so you can target the details you want to sharpen without affecting the surrounding areas.

Figure 7-26. The Sharpen tool isn’t meant for sharpening whole photos, but it’s great for sharpening details. Here it’s being used to touch up the details in the middle statue. (The red arrow points to the circular cursor.) Approach this tool with caution: It’s super easy to overdo it. One pass too many or too high a setting and you’ll start seeing artifacts.Strength controls how much the tool sharpens what you drag it over. A higher number means more sharpening.

Sample All Layers makes the Sharpen tool work on all the image’s visible layers. Leave this checkbox off if you want to sharpen only the active layer.

Protect Detail. This setting helps avoid pixelation (blockiness)—at least, it’s supposed to. In reality, this setting doesn’t always have much effect. Adobe suggests leaving it turned on unless you’re after an exaggerated sharpening effect.