![]()

Deuteronomy renews the covenant made between God and Israel at Mount Sinai (Ex. 20–31). Later, the covenant was again renewed at Shechem (Josh. 24). All three records of the covenant reflect to some degree the treaty style shown in the table below. This style is consistent with the structure of treaties dating from the period between 1400 and 1200 B.C.

Treaty Form | Where to Find It |

Title | |

Indicates the ruler making the treaty or laws. | Identifies Moses as the speaker but notes that he represents the Lord (compare Ex. 19:21–25). |

Prologue | |

Reviews the history between the ruler and those with whom he makes the treaty, and its bearing on the laws that follow. | Reviews the history between the Lord and the Israelites, from Mount Horeb (Num. 10:11–13) to the present. |

Laws | |

Sets forth the ruler’s binding expectations for those with whom he makes the treaty. | Reviews the general laws (4:44—11:32) and specific laws (chs. 12–26) by which the Israelites were to live in the Promised Land. |

Deposition | |

Establishes terms for the treaty to be preserved. | Calls for the preservation of the stone tablets on which the Law was written, in the ark of the covenant. |

Reading | |

Requires the treaty to be regularly read in public lest its terms be forgotten. | Requires the people to constantly review the Law at home, and the king to record and read the Law publicly. |

Witnesses | Deut. 4:26; 31:19, 26, 28 |

Calls on the gods of the ruler and of those with whom he makes the treaty as witnesses to the agreement. | As the Lord is the only true God, He is the only witness needed. However, Moses calls on other forms of witness from God’s creation. |

Blessings and curses | |

Lists the benefits of keeping the treaty and the consequences of breaking it. | Lists the benefits of keeping the Law and the consequences of breaking it. |

Oath and ceremony | |

Requires parties to the agreement to ratify it by swearing an oath at a formal ceremony. | Calls for the erection of memorial stones containing the Law once the people have entered the Promised Land and for a ratification ceremony at Mount Ebal; commits the people and their descendants to a binding oath of loyalty to God’s faithful covenant. |

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

A Journey of Eleven Days … and Forty Years

After only eleven days of travel from Horeb (Mount Sinai) to Kadesh, Israel spent forty years getting from Kadesh to the plains of Moab, on the eastern side of Canaan. Talk about a long layover! Find out why they suffered this forty-year delay in Kadesh’s profile at Numbers 13:26 and “Seeing Beyond the Hurdles” at Numbers 13:27–33.

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

The Amorite capital taken by Israel was named Heshbon, meaning “Reckoning.” The city changed hands frequently over the centuries. See the site’s profile at Numbers 21:26.

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

The spies who scouted the Promised Land reported that Canaan’s cities were “fortified up to heaven” with towering walls. This discouraging news exaggerated some real facts: Canaanite cities were well-defended, especially Jericho, with its nearly impregnable double wall (see “The Wall of Jericho” at Josh. 6:20). High walls were the primary means of defense for ancient cities—but they weren’t infallible. See “Five Ways to Capture a Walled City” at 2 Kings 25:1–4.

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

The Israelites experienced painful consequences when they ignored warnings from Moses and the Lord not to attack southern Canaan (Deut. 1:42, 43; compare Num. 14:39–45). They had already rejected God’s plans and promises at Kadesh Barnea (Num. 14:1–10). Now they were badly defeated by the Amorites inhabiting that region of Canaan. Like bees, Amorite warriors swarmed the foolish Israelites and drove them out of the land. The text calls these enemies “Amorites,” but the Old Testament frequently uses that term as a synonym for Canaanites in general. The account in the Book of Numbers identifies these foes as Amalekites and Canaanites (Num. 14:43). For more about these tribes, see “A Promise and a Purpose” at Genesis 15:16; “The Canaanites” at Joshua 3:10; “Amorites and Canaanites” at Joshua 5:1; and “The Amalekites” at 1 Samuel 15:2, 3.

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

Some people spend their whole lives working behind the scenes, toiling away to the best of their abilities but with little to show for their efforts. The Hebrews trudged through the wilderness for forty years, and many of them may have felt unnoticed, undervalued, and discouraged. This decades-long detour on the way to the Holy Land resulted from their crisis of faith at Kadesh Barnea (see “Seeing Beyond the Hurdles” at Num. 13:27–33). Everyone twenty years of age and older was condemned to die in the wilderness, except for Joshua and Caleb (14:29, 30). Those who had been children when Israel fled Egypt were now in their forties and fifties. Yet what had they done with their lives but wander through desert wastes, waiting for their parents’ generation to expire?

Moses’ assurance that “the LORD your God … knows your trudging through this great wilderness” (Deut. 2:7, emphasis added) must have come as a much-needed word of encouragement. God had not forgotten this new generation. He knew the “work of [their] hand,” the difficult task of surviving the wilderness journey.

God also sees us when we work without reward or recognition. He knows our good times and bad times. He has been and will be with us every step of the way.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

As Moses reviewed the history of Israel’s wilderness journey, he briefly mentioned “our brethren, the descendants of Esau.” This passing reference to the Edomites was a kind gesture given the trouble that the Hebrews’ cousins had caused.

The king of Edom had refused the Israelites access to the King’s Highway, a major thoroughfare that passed through Edomite territory and the most natural route to take from Kadesh to the plains of Moab (Num. 20:14–21; see also “The King’s Highway” at Num. 20:17). This discourtesy forced Israel to travel around Edom, and the people grew discouraged and complained. God punished their rebellion by sending fiery serpents (21:4–9; see also “The Bronze Serpent” at Num. 21:8, 9). The incident likely would not have occurred if not for the obstinacy of Israel’s Edomite “brethren.”

Moses may have overlooked the slight, but the rest of nation did not. During the reigns of Saul and David, military campaigns against the Edomites resulted in mass extermination (see “Pain That Leads to Prejudice” at Num. 20:14–21). Holding a grudge can lead to tragedy that far outweighs the original offense. Forgiveness not only helps to avoid such tragedy but also paves the way for blessings that might otherwise have been missed.

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

The land that Moses designated for Reuben and Gad was the eastern portion of a geographical region known as the Arabah, a plain beginning south of the Sea of Chinnereth (or Galilee). See its location on the map “The Plains of Israel” here.

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

Moses labored his entire life, leading Israel through extreme spiritual highs and lows until they arrived at the brink of receiving their great inheritance. Yet the fruit of his labors would go to someone else. Despite a lifetime of leadership, he would pass the reins to Joshua, who would finally take the people into the Promised Land.

Moses accepted the transition with remarkable goodwill. Perhaps because Moses was a humble man (Num. 12:3), he never assumed that the authority and position he enjoyed were his to keep. He saw them for what they were—temporary gifts from God to be held in trust during his brief life on earth.

We often cling to possessions or positions of power, suspicious that God might take them away. But, like Moses, we can gain the humility to hold them with a light touch, mindful that everything we have is a gift from God (1 Cor. 4:7), given to us to use—and even to give away—but not to own.

More: Moses was called the humblest man on the face of the earth (see “The Humblest Man on the Face of the Earth” at Num. 12:3). But in a moment of weakness, Moses forfeited the opportunity to enter the Promised Land. See “Overcoming Impulses” at Num. 20:10–13.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

Moses carried out one of the key tasks of a leader when he taught the Israelites. By teaching them to understand and follow God’s laws, he empowered them to act responsibly, wisely, and independently, unleashing their potential to become “a great nation” of “wise and understanding people.”

If we think authority means merely telling others what to do, then we will inevitably train others to become passively dependent, waiting for their next orders. If we instead view authority as an opportunity to invest in others and help them develop their own expertise, then we empower them to become leaders for a new generation.

More: For more on empowering rather than overpowering subordinates, see “Practical Principles for Leadership” at Ex. 18:13–23.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

Moses’ prophetic words about the Lord scattering the Israelites among the other peoples of the earth were fulfilled centuries later. As the Hebrews turned from the Lord to serve idols more and more, they acted even more corruptly than the Canaanites they had displaced. God allowed foreigners to capture their cities and take them as captives to distant lands. See “Scattered Among the Gentiles” at Jeremiah 9:16 and “The Dispersion of the Jews” at Jeremiah 52:28–30.

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

The declaration that the Lord is uniquely God, that “there is none other besides Him,” is especially remarkable in the context of the cultures surrounding the Hebrews. Israel’s monotheism was unique among the Egyptians, Moabites, Edomites, and Canaanites, who all worshiped numerous gods. God’s nature as the one true God also negates the popular modern view that “all religions are basically the same” and that Christianity is just one among many equally valid belief systems. See “No Other Name” at Acts 4:12. Find out more about Canaanite deities in “The Gods of the Canaanites” at Deuteronomy 32:39.

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

Contrary to popular belief, urban centers do not inherently act as breeding grounds for danger and violence. In fact, the Bible presents the city as a place of safety and lawfulness. Israel’s cities of refuge represent this perspective. God set aside these cities to shelter people who had committed accidental manslaughter. Rather than running away from a community, the suspect was encouraged to run toward one. Citizens of the city were to protect the suspect and ensure a fair hearing rather than leave him in the open to be preyed upon by the dead person’s relatives.

The hazards of modern life in cities (or anywhere) are often a result of the loss of community. The answer to urban crime is not to flee to the suburbs but to reclaim the benefits of living alongside one’s neighbors in peace, without fear or prejudice but with meaningful interaction and generosity. God yearns for us to live in fellowship with one another (see “Love Every Neighbor” at Luke 10:27–37; see also Matt. 18:20).

More: The apostle Paul realized that God was at work in the city. See “Paul’s Urban Strategy” at Acts 16:4.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

Bezer, Ramoth Gilead, and Golan were three cities on the eastern side of the Jordan River set aside as places of refuge for those who had unintentionally caused the death of another person. Three other cities were selected on the western side of the river so that Hebrews throughout the land could have ready access to asylum. Find out more about this provision of the Law to avoid tragic cases of revenge in “Cities of Refuge” at Numbers 35:11.

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

Some tend to imagine the past as a simpler time, but Scripture indicates that many things vied for people’s attention in the ancient world as they do today—so much so that Moses went out of his way to help the Israelites put off distractions and focus on what really mattered. After briefly reviewing how God had rescued them from Egypt and watched over them during their desert journeys, Moses challenged the nation to focus on the Lord’s “statutes and judgments.” He urged them …

• to “hear” the statutes and judgments—to listen to them attentively and repeatedly,

• to “learn” them—to go beyond simple memorization to personal ownership,

• to “be careful to observe” them—to make them a way of life.

After Moses reviewed the Ten Commandments (Deut. 5:6–21), the core of the Law, he repeated his call for a three-part response to the Law (5:32, 33):

• “Be careful to do” them—a response of obedience.

• “You shall not turn aside” from them—a response of focus.

• “You shall walk in all the ways”—a response of integrating the Law into everyday life.

This emphasis on staying attentive to what God says is repeated throughout Deuteronomy (for example, “Hear, O Israel,” 6:4; 9:1; 20:3; 27:9). It is also echoed throughout Scripture (for example, Ps. 19:7–11; 119:9, 11; Matt. 4:4, 7, 10; Rom. 12:2). God’s people should always remember what really matters: amid the many demands that confront us, we must maintain a single-minded focus on the Lord and His words.

More: The Ten Commandments summarized the Law for Israel. Christians have also developed helpful summaries of belief and practice. See “Creeds and Confessions” at 2 Chr. 15:14, 15.

Go to the Focus Index.

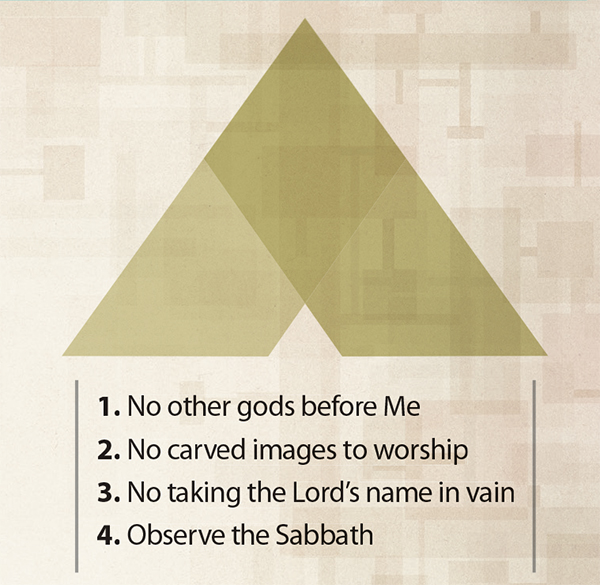

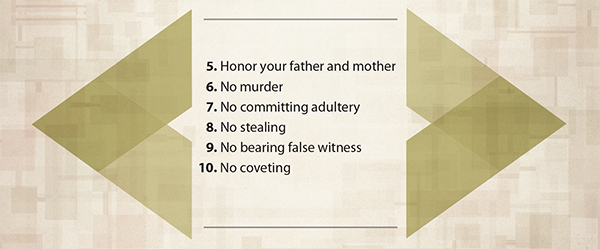

![]()

Jesus said that the entire Law rests on two preeminent commandments: loving God and loving our neighbors as we love ourselves (Matt. 22:36–40; compare Deut. 6:5; Lev. 19:18). The Ten Commandments (Deut. 5:6–21), which summarize the Law, speak to practical ways we should fulfill our duty to love God and others. The first four commandments (5:6–15) address our love for God.

The last six commandments (5:16–21) concern our love for others.

Loving God and loving others are interdependent in that we cannot do one without the other (James 2:10; 1 John 4:7, 8). The more we love God, the more we must engage in serving others’ needs. And if we want to sustain our love for people, we must continually draw on God’s love for us.

Christians throughout history have often emphasized one love or the other, sometimes to the near exclusion of the other. But the Ten Commandments do not allow for an either/or approach to love. God’s people must love Him and love others. The two cannot be separated (1 John 4:7–16; 5:2, 3).

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

The commandment to keep the Sabbath holy did not render other days of the week and their activities unholy. God designed the Sabbath to remind Israel that human beings are His creatures, ultimately dependent not on themselves but on Him for their livelihood and well-being. Like the Hebrews, our observance of Sunday as the Lord’s Day can help temper our feelings of ambition and self-reliance. People have a tendency to overdo good things, including work (see “Modern-Day Idols” at Is. 46:5–10), but God’s invitation to a regular day of rest can liberate us from this self-inflicted bondage.

More: A day off is God’s gift to us. See “Taking a Break” at Ex. 35:1–3.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

The command to honor our parents is the “first commandment with promise,” as Paul pointed out (Eph. 6:2, 3). The promise is a long and prosperous life. If we willfully disobey our parents and reject their authority—and if as grown children we dishonor them—we are likely to suffer hardship as a natural consequence of such behavior. The ancient Hebrews took this commandment so seriously that they regarded chronic rebellion as a capital offense. Unyieldingly disobedient young men were eventually stoned to death. See “Juvenile Delinquents” at Deuteronomy 21:18–21.

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

The Israelites displayed deep reverence for God when they stood before Him at Mount Sinai. They were terrified of the lightning and fire that marked the Lord’s presence, so they begged Moses to climb the mountain and act as their spokesperson while they stayed below (Deut. 5:23–27; compare Ex. 19:14–16; 20:18–21).

Yet God knew their hearts. As long as the people stood before Him, they might fear and obey Him, but once they departed, they would quickly forsake His ways. Out of sight, out of mind! Thus God’s sobering comment to Moses: “Oh, that they had such a heart in them that they would fear Me and always keep all My commandments” (Deut. 5:29, emphasis added).

God longs for faithfulness. He wants us to be committed to Him not only when we feel Him watching but even when it seems as though our actions go unseen. We tend to imagine that righteousness coincides with encountering God’s presence. But it is what we do when we feel apart from God that defines our faithfulness.

More: Even as the Lord spoke with Moses on the mountain, the people turned to idolatry, worshiping a golden calf as their deliverer from Egypt. See “Seeing vs. Believing” at Ex. 32:1–4.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

The Hebrews were different from many ancient peoples in their belief in only one God. Most surrounding cultures were polytheistic, worshiping multiple gods. For example, the Canaanites had at least seventy deities (see “The Gods of the Canaanites” at Deut. 32:39). Likewise, the Egyptians had a large pantheon of gods and they also considered their pharaohs divine. Throughout the Middle East, it was common for cities to have their own “local” gods in addition to more widely recognized gods.

The Israelites stood apart. Abraham and his family originally lived in Ur (Gen. 11:27–30), a Sumerian city-state dedicated to the moon god Ninna (later called Sin) and the goddess Ningal. In the midst of this polytheistic society, the Lord spoke to Abraham, instructing him to leave his home and country behind (12:1–3; Acts 7:2, 3). It appears that Abraham believed in only one God from that point forward—the God who continued to reveal Himself over many years to this man and his descendants. By Moses’ day, the Lord referred to Himself as the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob (Ex. 3:15).

The distinction between monotheism and polytheism lies not only in the number of gods but also in their natures.

Polytheism vs. Biblical Monotheism

Polytheism | Monotheism |

Belief in many gods. | Belief in one God. |

Usually a chief god reigns over the other gods. | The Lord God is the one and only God. |

Rivalries exist within the pantheon. Gods can be assimilated into other religions if their nations or cities are conquered in war. | The Lord God has no rivals. His enemies (Satan and demons) are not gods but created beings. God’s existence and nature do not change even if people choose to believe otherwise. |

Gods are often identified with natural phenomena, such as storms, fire, and the planets. | The Lord God is separate from His creation, which He made not out of Himself but out of nothing. God sometimes causes natural phenomena to occur, but they are not any part of His being. |

Gods are usually as prone to moral failure as human beings, if not more so. | The Lord God is holy, the absolute standard of moral purity and goodness. |

Although the Israelites had a monotheistic religion, they often lapsed into idolatry. Yet their false worship only reaffirmed the Lord as supreme, because each time they turned from Him, He reasserted Himself, exposing the futility of their idols and the necessity of His sovereignty.

The God of Scripture is not the same as other gods. He is not merely some “higher power” or local idol. He is not merely one member of a throng of deities. He alone is Lord over all the heavens and the earth. He alone is worthy of our devotion. He alone loves us with a perfect love. He is the one true God.

More: Moses’ declaration that “the LORD our God, the LORD is one” (Deut. 6:4) was echoed centuries later by another Old Testament prophet who called people to unwavering commitment. See “Moses and Elijah” at 1 Kin. 19:11. For more on the uniqueness of God, see “No Other Name” at Acts 4:12.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

Faith is always one generation away from extinction. No matter how much one generation embraces religion, belief is an individual decision. Yet although Christians cannot believe on behalf of their children, they can help them take their first steps toward faith.

Moses urged the Israelites to teach the Law to their children (Deut. 4:9, 10; 6:7–9, 20, 21; 11:19). The people already had a rich legacy of stories to draw upon in explaining God’s ways to new generations: the creation narrative, the lessons of the patriarchs, the Exodus account, and the memory of the wilderness journey (6:20–25). Now the Law would help the Israelites talk about concrete ways to obey God, and Moses offered suggestions for imparting these statutes to young people, principles still useful today.

1. Know God’s Word. Moses challenged the Israelites to be a “wise and understanding people” who were educated and discerning about the Law (4:6). He instructed them …

• not to add anything to the words of the Law (4:2);

• to speak from experience by putting the commandments into practice (4:5, 6);

• not to forget anything God had said or done for them in the past (4:9);

• not to forget the Lord or substitute anything or anyone for Him (4:15–19, 23, 24).

Moses’ words challenge parents to read and study the Bible for themselves, to follow God’s commandments, to put Him first, and to hold dear the remembrance of His actions. Truly knowing the Word requires active involvement. If we try to teach our children through only secondhand information, our lessons will fall flat.

2. Grow in passion for God. Moses exhorted the people to seek personal experience with God (6:1–9). He told them …

• to fear the Lord all the days of their life (6:2);

• to love the Lord with all their being—heart, soul, and strength (6:5);

• to establish habits for recalling and rehearsing stories of God’s dealings in their own lives and in the histories of their ancestors (6:7–9);

• to live with gratitude, because every good thing was a gift from God and not the result of their own efforts (6:10, 11).

Parents cannot inspire their children toward a faith that they themselves do not possess. And for the Christian, to truly possess faith is to engage in a vibrant relationship with the living God.

3. Teach by example. Moses urged the Israelites to practice the Law so their children could see it in action rather than simply hear it recited (10:12, 13; 11:1, 2, 7, 8). He reminded them …

• to live with the perspective that God owns everything (10:14);

• to maintain integrity by refusing bribes, ensuring justice for orphans and widows, and showing loving care for strangers (10:17, 18);

• to worship the Lord regularly through fasting, praise, and remembering His dealings with Israel (10:20–22);

• to live out their faith in front of their children, who lacked the experience their parents had with Him (11:2);

• to stay singularly focused on the Lord and avoid faith-destroying loyalties, especially to idols (11:13, 16);

• to talk about truths of God during the routines of day-to-day life (11:19, 20).

Children pick up on unspoken cues and know intuitively what their parents truly believe and where their loyalties lie. We need to model Christlikeness before our children if we want to see them take God seriously.

4. Be creative. Moses wrote a song to declare God’s ways to Israel (32:1–47), using the arts to celebrate the Lord and encourage children toward faith in Him (31:9–13, 19, 22, 30). Likewise, Moses advised the people …

• to rehearse the Law every seventh year for the whole community, including children and aliens (31:10–13);

• to develop music to honor the Lord and declare His mighty acts (31:19, 22);

A famous youth pastor once said, “It’s a sin to bore a kid with the gospel.” Unfortunately, that’s what happens if we don’t make the effort to be creative teachers. Children need to learn about God in a way that reflects how interesting He is, or else we risk losing their interest altogether.

What more could we wish for our children than love, protection, and forgiveness from the Creator of the universe, who will be a Parent to them no matter what else may happen? What more than the one relationship that will never fail them, the one pursuit wherein lies their future hope and joy? We can help our children see that God will guide them and fulfill their needs along the way they travel with Him.

More: Susanna Wesley stands out as a parent who succeeded in guiding her children through their spiritual development, teaching them not only to believe but to actively engage with God. See here for an article on her life.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

When Israel moved into Canaan, they discovered more than farms, forests, and fields. The land contained many “large and beautiful cities” that were “great and fortified up to heaven” (Deut. 6:10; 1:28). The Israelites took possession of a patchwork of city-states that included dozens of settlements listed in Joshua (Josh. 15:21–63; 18:21—19:48; 21:1–40). They continued to conquer Canaanite cities into the period of the judges (Judg. 1:8–26).

So God gave His people a land complete with walled cities, houses, water systems, cisterns, courtyards, terraces, temples, and palaces. These urban assets came with conditions spelled out by Moses (Deut. 6:12–19). The main stipulation was faithfulness to the Lord: if Israel continued to follow God after they took possession of the cities, then it would “be righteousness” for them (6:25).

There are some who claim that cities are inherently more corrupt than the country, but the biblical record seems to negate this. Just as God placed His people in an early urban society to live out His commandments, we too can follow Him in the midst of the city. Wherever we may be, in the heart of a metropolis or at the far edges of a wilderness, we need never be far from God.

More: The only major city believed to have been originally founded by the Israelites is Samaria, capital of the northern kingdom (1 Kin. 16:24). Christianity eventually prevailed as the dominant worldview of the Roman empire because early believers planted churches in dozens of major cities. Learn more about this strategic approach in “Churches Unlock Communities” at Acts 11:22.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

The biblical word translated here as mercy (Hebrew: chesed) did not suggest that God ignored, excused, or indulged wrongdoing. It conveyed that a person could be counted on to carry out promises made in a covenant or agreement. Thus God kept “covenant and mercy” with His people by showing them loyalty even when they did not deserve it.

God calls those who fear Him to show this sort of mercy in every aspect of life. Some examples:

• Governments show mercy when they enforce laws that prevent oppression of the vulnerable.

• Husbands and wives show mercy when they keep their vows of marital faithfulness, love, and service.

• Employers show mercy when they follow through on agreements, written or spoken, regardless of their profit margins.

• Employees show mercy when they give assignments their best efforts despite fatigue and competing demands on their attention.

• Businesses show mercy when they provide customers with the quality of merchandise and service that has been advertised and paid for, even if the business must take a loss (Ps. 15:4).

Mercy should define our relationships with others. We emulate God’s mercy when we follow through on our words just as He does.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

If we think of mercy as the act of overlooking wrongdoing, then we are likely to view justice as its opposite, as if mercy moves to limit punishment, whereas justice demands full payment. This is not how God understands mercy and justice. We sometimes struggle to balance the two, but to Him they are never at odds.

God is “of purer eyes than to behold evil, and cannot look on wickedness” (Hab. 1:13). He chooses to withhold punishment not out of indulgence but because He patiently waits for repentance, allowing us ample time to change our ways (Is. 30:18; 2 Pet. 3:9, 15). Yet if repentance never comes, the Lord’s mercy moves Him to enforce justice (Deut. 5:9; 7:9–11).

God’s response is similar to what we mean when we talk about “tough love.” Genuine love entails commitment to another’s welfare. And watching out for someone else’s welfare does not always mean making them happy. God loves us too much to let us stay captive to sin. His infinite love sometimes moves Him to exact judgment when we refuse to do the right thing.

More: As you exercise leadership over others, consider how God exercises mercy and judgment. You have been given power to build others up, not to tear them down. See “Spiritual Authority” at 2 Cor. 13:10.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

God’s promise to bless and multiply the people, animals, and fruit of the land in exchange for obedience to the Law must have offered the Israelites immense hope. Fertility was such a concern in the ancient world that a woman who did not bear children was considered cursed. See “Barrenness” at Genesis 18:11, 12.

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

The God Who Gives Wealth and Treasures the Poor

Moses’ word to the Israelites that “God … gives you power to get wealth” shows that wealth ultimately comes from God. Many Scriptures reinforce that God deserves credit and thanks for whatever we possess (for example, 1 Sam. 3:7; Hos. 2:8). On the other hand, the Bible does not teach that financial riches are a reward for good behavior or what God desires for all of His followers. So the lesson of this verse is twofold: abundance is a blessing, but need is not a punishment.

The fact that the Lord is the ultimate source of prosperity proves that wealth in itself is not evil (compare James 1:17). Moses’ statement also shows the importance of human responsibility in obtaining wealth. God did not give wealth directly so much as give His people the ability to work their fields and develop their resources so that they could prosper.

On the other hand, the Lord’s repeated commands to act charitably and generously toward those less fortunate (for example, Ex. 22:21, 22; Deut. 24:17–21; Ps. 82:3, 4; Heb. 13:1–3; James 1:27) show that God cares deeply for those who have been brought low—the poor, the widowed, the orphaned, the outsider, the ill, the imprisoned. And He not only commanded us to watch out for them but even identified them with Himself, proclaiming that those who are kind to the humble are also showing kindness to Him (Matt. 25:31–46).

All that we have ultimately comes from God. We should never expect God to give us financial gain, especially without effort, yet we can continually turn to Him for wisdom and strength if we are in need.

More: To find out more about the intersection of wealth and faith, see “Giving to Get” at 1 Tim. 6:3–6 and “Christians and Money” at 1 Tim. 6:6–19.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

Among the peoples inhabiting Canaan before the Israelite invasion were the descendants of Anak, or Anakim. The Old Testament often comments on their stature, but we know little about the group except that they were “great and tall.”

The spies sent into Canaan reported seeing “giants” (Hebrew: nephilim), and the text explains that the Anakim were descended from the “giants” (Num. 13:33). The spies claimed to have felt like grasshoppers in comparison to them. The Anakim were perhaps similar in height to the Philistine champion Goliath, who measured six cubits and a span, or about nine feet and nine inches tall (1 Sam. 17:4). A person of this size would be imposing, deserving of the proverb that asked, “Who can stand before the descendants of Anak?” (Deut. 9:2). For the Israelites, the Anakim became a benchmark for evaluating the size of other peoples (2:10, 21).

The Anakim lived in the hill country of southern Canaan. Kirjath Arba, later known as Hebron (see the city’s profile at Gen. 23:19), may have been their principal settlement. Most Anakim were killed or driven out early in Joshua’s conquest (Josh. 11:21, 22), and Caleb expelled the remainder when he was allotted Hebron (21:11, 12; Judg. 1:20). It seems appropriate that the two spies who refused to be intimidated by the Anakim were the ones who inherited their lands (Num. 14:6–9).

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

Justice for the Outcast

Pandita Ramabai (1858–1922) has been acclaimed as a “mother of modern India” for her work on behalf of widows and orphans. As a Christian convert, she struggled to express the values of her new faith without denying her cultural heritage or validating the imperialist forces in her home country.

In a place and time when women were denied even basic schooling, Ramabai’s father scandalized his high-caste friends by countering prevailing Hindu culture and teaching his wife and daughters to read the Sanskrit classics.

Ramabai was still in her mid-teens when her sister and parents perished during a severe famine, leaving behind Ramabai and a brother. The two siblings walked across the vast stretches of India, visiting holy Hindu shrines and attracting audiences with Ramabai’s recitation of Sanskrit poetry. They eventually arrived at Calcutta, where Ramabai met university scholars who were astonished by her skills in interpreting sacred texts and awarded her the title of Pandita (“Learned Master”).

At the age of twenty-two, Ramabai, a high-caste Chitpavan Brahmin, shocked onlookers by marrying a lower-caste lawyer. The next year she founded Arya Mahila Sabha, the first organization in India to advocate for women’s education. She and her husband Babu planned to start a school for child widows as well, but he died only two years after their wedding, leaving Ramabai a widow with an infant daughter, Manorama.

Ramabai’s present circumstances made her increasingly concerned about the bleak plight of widows and orphans, and her continued study of the Hindu scriptures did little to reassure her. She began what she later described as an agonizing process of conversion: “Having lost all faith in my former religion, and with my heart hungering after something better, I eagerly learnt everything I could about the Christian religion, and declared my intention to become a Christian.” Ramabai’s work had brought her into contact with Christian missionaries, who invited her to visit England; it was during these travels that Ramabai undertook a serious study of the Bible and decided to be baptized.

In 1888 Ramabai wrote a book entitled High Caste Hindu Women to expose the dark lives of Indian women, exploring topics such as child brides, widowhood, and institutionalized abuse by society and government. The practice among higher castes of betrothing young girls to much older men (her own mother had been nine years old, her father over forty, when they were wed) had contributed to the vast number of widows in India, who were entirely bereft of status or education.

In her home country Ramabai faced opposition for both her faith and her proposed reforms, yet she persevered to found the resident school Sharda Sadan (“House of Knowledge”). She began with twenty girls, but that year India faced another severe famine. She rescued thousands of starving children, widows, and other destitute women, bringing home an additional two hundred girls to live at Sharda Sadan, where they were given basic education and training in marketable skills. Eventually more than two thousand girls and women lived in what grew to become the Mukti (“Liberation”) Mission, an enterprise that still provides housing, education, medical care, and vocational training for the needy, including widows, orphans, and the blind.

Ramabai’s activism was fueled by her interpretation of the gospel, which to her deeply validated her growing belief that to serve the poor and the socially outcast was a religious and not simply a social work. “People must not only hear about the kingdom of God,” said Ramabai, “but must see it in actual operation, on a small scale perhaps and in imperfect form, but a real demonstration nonetheless.” From the Bible Ramabai had learned that to love God and to love one’s neighbor as oneself was at the heart of authentic faith.

Over a period of twelve years, Ramabai translated the Bible into her native language of Marathi from the original Hebrew and Greek texts, completing final revisions only hours before her death. Today only a wooden cross amid humble farmland marks her grave.

Go to the Life Studies Index.

![]()

Of all the information and stories in the Bible, one point captures what God wants from us as individuals: “Fear the LORD.” That is, we should respect Him, keep His commandments, love Him, and serve Him with all that we are and have. Nothing else is more important.

More: No clearer statement of God’s intentions can be found in Scripture than the formula to fear Him and love Him completely, a statement frequently repeated throughout the Bible (for example, Deut. 6:5; Eccl. 12:13; Mic. 6:8; Matt. 22:36–40).

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

Israel’s national prosperity was directly connected to its moral and spiritual health, measured by its adherence to the Law. If the people obeyed God and followed His ways, He promised to bless their lands with abundance. If they abandoned Him and turned to other gods, He threatened to bring drought and economic ruin.

The relationship between obedience and national prosperity is less exact today. The promises of Deuteronomy reflect a special covenant between God and a people of His choosing, and the Lord has never entered into a similar agreement with any other nation. Nevertheless, a nation that respects God will experience definite benefits, whether material or otherwise. All nations ultimately answer to Him (see “No Authority Except from God” at Ps. 2:4–6). He therefore monitors the actions of governments and their citizens. He does not allow evil to go unchecked, nor does He reward faith and obedience with unmitigated disaster.

More: The guarantee of national prosperity in the often-quoted 2 Chr. 7:14 is a specific promise for Israel. See “National Renewal” at 2 Chr. 7:14. We imperil our faith when we adopt God’s promises to Israel as guarantees to us as individuals. See “Giving to Get” at 1 Tim. 6:3–6.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

After reviewing the history of Israel’s years in the wilderness, Moses pointed to the western horizon where two mountains in central Canaan, Gerizim and Ebal, could be seen in the distance. He designated them as symbols for a blessing and a curse. The meaning of this odd incident would become clear later. See “Signing Off on the Covenant” at Deuteronomy 27:11–13.

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

Moses frequently reminded the Israelites to teach the Law to their children. The new generation had not witnessed God’s works during the Exodus or wilderness journey. They had no firsthand experience of the Lord’s deliverance and provision of food, water, protection, and guidance. They were not present during His appearance at Mount Sinai. They depended on their parents to describe and explain these things to them.

Little ones still largely depend on their parents’ worldview while developing their own, so modern parents must find ways to convey the Lord’s goodness and greatness to the next generation. Some ideas:

• Explain how you came to know God.

• Tell stories of how God has worked in your life.

• Share how difficulties have caused you to grow spiritually.

• Pray together at meals, bedtime, or when significant events are taking place.

• Invite your children into your joys, sorrows, successes, and failures as you journey with God through life.

Our children need to see us as real people with real faith. By making God part of our daily conversations, we give our kids a concrete idea about faith, which they can build on as they develop their own relationship with Him.

More: For more ideas on communicating God’s ways to children, see “The Faith of Our Children” at Deut. 6:7–9 and “Help for Families” at Heb. 12:3–13.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

Like many ancient peoples, the Canaanites worshiped their gods on the tops of mountains and hills. These “high places” were centers of idolatry destined for destruction when Israel entered the Promised Land.

The elevation of the high places made worshipers feel closer to their gods. Vistas overlooking their farmlands perhaps gave worshipers a sense of power as well. Baal, a principal god given the epithet “rider of the clouds,” was sometimes depicted sitting on the crest of a hill.

Worship on the high places took place among sacred groves, graven images of the gods, and large stones said to mark where a god had visited earth. A main goal of the rites was to increase the fertility of people, livestock, and crops. Ritual prostitution was common.

Despite God’s command to destroy the Canaanite high places, the Israelites often let them stand, sometimes attempting to adapt them into the worship of the Lord (for example, 1 Sam. 9:19–24; 10:5, 6; 1 Kin. 3:2). More often, however, the sites were used for idolatry (for example, 1 Kin. 11:7; 12:26–31; 2 Kin. 12:3). A few leaders brought about revival by cutting down sacred groves and pulling down idolatrous pillars (for example, 2 Kin. 18:4; 23:14). But usually within a generation or two, the reforms were abandoned (for example, 2 Kin. 21:3).

By the days of Jeremiah, so many idolatrous worship sites existed—not only atop mountains and hills but in valleys, towns, and individual homes—that the prophet remarked that Judah had as many gods as cities (Jer. 2:28; compare 2 Kin. 17:9).

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

When individuals become the ultimate authorities in religion, people feel free to reject any demand that feels limiting or imposing and instead develop self-styled beliefs and habits. Some pick and choose from established Christianity. Others invent outlandish ideas about God and indulge in eccentric lifestyles.

A similar attitude characterized the Israelites as they prepared to enter the Promised Land. Apparently they had made up their own minds about how to go about religious observances. They had not necessarily turned away from God, but the lack of a permanent worship center seems to have fostered laxness regarding ritual obligations.

Moses warned that such latitude should end once the people entered the land and God designated a site for worship. The Lord expected the Israelites to follow the Law’s detailed instructions for sacrifices, holy days, tithes and offerings, and other religious habits.

The New Testament’s instructions for worship are not nearly as detailed as those of the Old Testament law. The new covenant offers more freedom to individual believers and communities of faith. Yet that liberty does not permit a do-it-yourself approach to religion. Scripture outlines objective truths and behaviors for believers. There may be room within those boundaries for cultural, ethnic, and geographic expressions, but we fall into sin when we move outside Jesus’ clear delineation of right and wrong. However we worship God, we are still called to worship Him “in spirit and truth” (John 4:23).

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

God commanded the Israelites to periodically offer a “tithe” or “tenth part” of their produce or income for three reasons: to celebrate the abundance that He had provided; to provide for the Levites, who owned no land because they were responsible for the tabernacle and worship (Deut. 14:27; Num. 18:20–24); and to provide for the poor (Deut. 14:28, 29).

Christians are not bound by this law of the tithe, but its principles still apply: Jesus told His followers to “freely give” just as they had “freely received” from the Lord (Matt. 10:8). And when asked by a wealthy man what he must do to gain eternal life, Jesus replied that he should keep the commandments and “go, sell what you have and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven; and come, and follow Me” (Matt. 19:21).

God invites us to feast and be joyful in light of His provision and goodness. We should express our thankfulness for the blessings we have received by making the most of our financial resources to celebrate God’s abundance, support vocational Christian workers, and provide for the poor.

More: Find out more about Christians’ approach to the law of the tithe in “Tithing” at Matt. 23:23, 24.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

The Third-Year Tithe and Government Aid

Every government debates about what to do for the impoverished living within its domain. One view insists that the poor should fend for themselves, that helping them would make them an intolerable burden on society. Another holds that it is inhumane not to give aid to any member of the populace who is unable to provide for his or her own needs. Christians question whether the Bible endorses government-sponsored assistance or whether that assistance should come from another source.

The debate is not easily settled. But we can consider God’s instructions to the Israelites. The Law assumed that certain types of people in Hebrew society would be at an economic disadvantage: Levites, orphans, widows, and “strangers,” or non-Hebrew foreigners. Thus the Law mandated that a tithe (or 10 percent) of every third year’s produce should be set aside for these groups. It was to be stored “within [the] gates,” indicating that the aid should be collected and administered not by individual households but by municipalities.

The system of the third-year tithe was designed to prevent laziness or chronic dependence. The poor were welcome to eat what they needed from the supplies, with regulated distribution preventing abuse. And since beneficiaries of this aid were neighbors living within the community, it was impossible for someone to travel from town to town freeloading.

The regularity of the third-year tithe, which was collected and distributed in the third and sixth years of every seven-year cycle (Lev. 25:4), made it an effective program of relief, but its infrequency ensured that no one could shirk all work and survive purely on charity.

More: Israel’s poor also obtained assistance by gleaning, going over a field or vineyard after the harvest to collect leftover produce. See “Gleaning and the Poor” at Lev. 19:9, 10. The New Testament instructs churches to implement systematic relief for the disadvantaged. See 2 Cor. 8–9 and “Effective Care for the Needy” at 1 Tim. 5:3–16.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

The “creditor” mentioned in Deuteronomy was not an ancient counterpart of a modern banker or credit institution. He was merely a neighbor who had loaned something to another. Institutional banking was unknown in ancient Israel until the Babylonian captivity (587–538 B.C.). The absence of banks resulted in part from laws against charging interest on loans, a traditional function of banks, when lending to fellow Israelites (Ex. 22:25; Deut. 23:19, 20). As for the protection of valuables, people either hid them (Josh. 7:21; Matt. 13:44; Luke 19:20), left them with a neighbor (Ex. 22:7), or, in Solomon’s time, deposited them at the temple or palace, where the national wealth was stored (1 Kin. 14:26). By New Testament times, however, banking had become an established institution (see “Banking in the New Testament” at Luke 19:23).

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

Success always comes with the danger of forgetting what we have left behind—the drudgery of low-status jobs, the difficulties of learning a new culture, the fear of wondering how the future will turn out. To keep the Israelites from forgetting their humble past, Moses repeated again and again, “Remember that you were a slave in the land of Egypt” (Deut. 5:15; 15:15; 16:12; 24:18, 22). That history gave the Hebrews every reason to show kindness to their own slaves and servants (15:12–14).

We need a habit of remembering our beginnings—where our families came from, what we lacked, how we were treated, how we dreamed of more. If we want our hearts to beat with compassion for others, these are things we cannot forget.

More: Paul called Christians at Ephesus to a discipline of remembering. The first half of his letter to them has only one appeal for action, a verb of exhortation: “remember” (Eph. 2:11).

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

Requiring the witnesses against a person accused of a capital crime to be the first to begin a fatal stoning was definitely not a perfect arrangement of justice, but it probably did help prevent unfair punishment as a result of petty differences. It’s one thing to bring charges against someone but quite another to take the leading role in his or her execution. Yet there was at least one circumstance in which accusers were not required to cast the first stone: when parents brought a rebellious son before the elders. See “Juvenile Delinquents” at Deuteronomy 21:18–21.

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

Throughout the wilderness journey, Moses was Israel’s appointed leader. Under him ranked the elders of the twelve tribes. But God knew that sooner or later the nation would cry out for a king. Anticipating that desire, the Lord defined criteria that should characterize any ruler of Israel. He provided guidelines to teach the people to value a monarch who would exercise godly control and resist the abuses for which neighboring nations’ leaders were notorious. Israel’s king should be …

1. Chosen by God (Deut. 17:15). God would choose a king from among the Israelites, a determination made not by popular election but by a divine call to serve the nation (17:20).

2. Not dependent on the military (17:16). The king was not to “multiply horses.” Ancient kings imposed exorbitant taxes to secure horse-drawn chariots, the prized battlefield technology of the day. A ruler obsessed with war would drain the nation of its economic resources and male population in order to build an army.

3. Not allied with superpowers like Egypt (17:16). Asking Egypt for horses or troops would lead Israel back to the pagan values it had left behind. Egypt counted on chariots, but Israel was to rely on the power of its covenant relationship with God (Ps. 20:7).

4. Few wives (Deut. 17:17). A king’s many wives signified power, sexual prowess, and alliances with other nations. The Lord warned against these ties, knowing they would turn the king’s heart from God.

5. Not excessively wealthy (17:17). Rulers could multiply wealth by imposing taxes, engaging in trade, and carrying out other profitable schemes. But riches could seduce a king into pride and make him forget that everything belongs to God.

6. Devoted to the Law (17:18, 19). The king was to make his own copy of the Law, perhaps in his own handwriting. He was to read the Law daily and observe it diligently so he would remain humble, follow God’s ways, prolong his life, and sustain the kingdom through his children.

The books of 1 and 2 Samuel, 1 and 2 Kings, and 1 and 2 Chronicles show that these guidelines were honored incompletely as Israel established its monarchy, and less and less as time passed.

More: For more of the Lord’s warnings about Israel becoming like other nations and begging for a king, see Samuel’s words in 1 Sam. 8:10–22.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

Priests in ancient Israel were to receive gifts from among the firstfruits of the people’s produce. This privilege stemmed from two factors: Levi’s descendants were not allowed to own land and were therefore without a practical means of support (Deut. 14:27; Num. 18:20–24). Also, priests were to be honored because God chose them to represent the people in worship (Deut. 18:5). See how this applies to ministers receiving pay and benefits today in “Professional Christian Workers” at 1 Corinthians 9:1–23.

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

Every culture surrounding Israel practiced magic. Scripture specifically names the Egyptians (Ex. 7:11), the Assyrians (Nah. 3:4), the Babylonians (Dan. 2:2), and the Canaanites (Deut. 18:14). There is no denying the strong seduction of magic and the occult. A longing for power or just plain curiosity can result in an unhealthy fascination with the real or apparent use of supernatural forces.

God’s law speaks clearly against divination, witchcraft, mediums, oracles, and soothsayers, calling them “abominations” (18:9–12). Yet despite these strong warnings in Deuteronomy and elsewhere in Scripture, Israel and its leaders turned to sorcerers and other spiritists for help during several times of crisis (2 Kin. 17:17; 2 Chr. 33:6; Mic. 5:12).

God never employs magic or other dark arts to reveal His will or exercise power. His people have no need to rely on any sort of magic, witchcraft, necromancy, fortune-telling, ritual drug use, or any spiritual practices not solely founded on godly principles as defined by Scripture.

Occult Arts Condemned in Scripture

Practice | Description |

Casting spells or enchantments (Deut. 18:11; Is. 47:9, 12) | Attempting to bind people with spells through chants or wailing. |

Consulting mediums (1 Sam. 28:3, 9) | Conducting a séance to conjure the spirit of a dead person (Is. 8:19; 29:4). |

Divination (Deut. 18:10; Jer. 14:14) | Attempting to forecast the future. |

Magic (Gen. 41:8; Ex. 7:8–13; Dan. 1:20; 2:2; Acts 8:9–25) | An occult art practiced by Egyptians and Babylonian advisors and by Elymas the sorcerer; involves the manipulation of the physical world in ways that seem impossible to observers. |

Passing a son or daughter through the fire (Deut. 18:10) | Child sacrifice (see “The Valley of Hinnom” at Josh. 18:16). |

Soothsaying (Deut. 18:10, 14; Lev. 19:26; 2 Kin. 21:6) | A form of divination, possibly cloud reading. |

Sorcery or witchcraft (Ex. 22:18; Deut. 18:10; Is. 47:9, 12; Jer. 27:9; Acts 8:9, 11; 13:6, 8) | Attempting to extract information or guidance from a pagan god by means such as interpreting the shape of a puddle of oil in a cup (compare Gen. 44:5), throwing down arrows to see which way they pointed, or “reading” the livers of sacrificial animals (Ezek. 21:21). |

More: For more on the dangers and evils of magical practices, see Is. 3:1–3, 18–23; 42:9–13. Magic severely distorted the values of one believer in the Bible, endangering his relationship with Christ. See “Simon the Magician” at Acts 8:9.

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

Earlier, Moses had designated three cities of refuge on the eastern side of the Jordan River (see “Places of Asylum” at Deut. 4:41–43). Once the people conquered Canaan, they were to add three more, scattering six asylums throughout the land. See “Cities of Refuge” at Numbers 35:11 to learn more about these safe havens for those who committed accidental manslaughter.

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

God’s policies on warfare presupposed that Israel would one day be at war with remote peoples since there are rules about besieged cities described as being far from Israel’s borders. The cities of the Canaanites were to be utterly destroyed (Deut. 20:16–18), but a scorched earth policy did not apply outside the borders of the Promised Land.

God did not intend for Israel to become imperialist like Assyria or Babylon, which were both known for devouring foreign territories, demolishing their cities, and exiling their people. The Israelites instead were to occupy the land promised to them and generally remain within its assigned borders (Num. 34:1–12). As much as possible, they were to live at peace with their neighbors.

Nevertheless, Israel would at times be threatened or attacked. Staging a counteroffensive against these foreign enemies might require Israel’s army to strike into enemy territory. When the Israelites encountered walled cities, they were to offer a truce (Deut. 20:10). A city’s response determined whether the Israelites should spare the city or besiege it (20:11, 12). Yet even if the Israelites attacked, foreign cities were to be treated with a measure of mercy and restraint not reserved for the cities of the Canaanites (20:14).

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

The Israelites waged war against the Canaanites because the Lord sent them to fight. That meets the definition of a “holy war,” a war that God declares, fights, leads, and wins. Similar engagements were carried out against the Amorites (Ex. 17:16) and Midianites (Num. 31:1–3).

Unlike the Egyptians, Assyrians, or Babylonians, ancient Israel did not maintain a standing army. Prior to the monarchy, it lacked chariots, horses, or sophisticated weaponry. The Israelites were to rely on the Lord, who promised to fight on their behalf. Even after Israel acquired military hardware and expertise, the nation was still to trust God to bring victory.

The Lord Himself was Israel’s defender. Although the nation’s men were often mustered to battle, the Lord fought through and for them. For this reason, Israelite warriors consecrated themselves to God, in part by abstaining from specific activities such as drinking or having sexual relations. Those who were distracted by fear, a recent marriage, a new house, or a newly planted vineyard were ordered to remain at home (Deut. 20:5–9).

The Lord set rules of engagement for His holy war. If a besieged city surrendered, the occupants were to be spared, though they would become servants of the Israelites (20:10, 11). Warriors were also to refrain from cutting down any trees that might serve as a source of food for the local people (20:19, 20). At times the Lord commanded utter destruction of Israel’s enemies (20:16). Once friends and neighbors of the patriarchs, these idolatrous tribes now faced the Lord’s purifying judgment.

The holy war against the Canaanites fulfilled God’s promises to Abraham (Gen. 15:18–21). But this was a unique campaign in human history; God never again called for His people to exterminate a society. Throughout history, political and religious leaders have claimed that God was commanding them and their followers to fight a holy war, but those declarations have always proven false. Holy war is no longer an option. The Lord uses other means to bring about change in the world’s societies—primarily the influence of changed individuals (Rom. 12:2; 1 Thess. 1:6–10).

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

The Israelites had a method of dealing with a chronically stubborn young man: “stone him to death with stones.” A law that prescribes capital punishment of a disobedient juvenile seems cruel and violent today. While we cannot always fully comprehend the concept of justice from a cosmic standpoint, here are a few considerations that can help us grapple with this part of the biblical record:

• The law prescribed an extreme punishment for an extreme situation. The offender was a thoroughly incorrigible youth—perhaps a teenage or young adult male, certainly not a child—who engaged in repeated rebellion. He had turned his back on his parents despite their ongoing attempts at correction.

• The law assumed intact families with parents exercising responsibility and leadership. Parents were responsible for raising their children to know and follow the Law (see “The Faith of Our Children” at Deut. 6:7–9). The law of stoning expands on the fifth commandment to honor one’s parents (5:16); having been instructed in the Lord’s commandments, when a youth dishonored his parents he was in effect turning his back not only on his family but also on God.

• The law assumed community participation in conviction and punishment. Turning to the elders of the community meant that the parents had no other recourse. The elders, not the parents, made the final decision and passed sentence on the son (21:19, 20). If the charges were found to be true, all the men of the city were to stone him to death (21:21). In capital cases the accuser usually cast the first stone (17:7), but in this case the offender’s father was not asked to initiate the punishment. It was a shared responsibility, a dreaded burden shared by many rather than forced on the man who dreaded it most. The shared responsibility of carrying out the sentence also strongly suggests that the entire community probably shared in the attempts to correct the son’s behavior, doing everything possible to avoid taking part in the final penalty.

• The law assumed individual independence. Young adults must make their own decisions. Although parents can point them down God’s path, sooner or later children must choose for themselves how to live, and parents must recognize their independence. And for better or for worse, with free will comes consequences for one’s actions.

It is unknown how often this remedy for rebellion was enforced by the Israelites, and this law by no means gives parents today any license to abuse their children or punish them by life-threatening means. Such behavior completely contradicts Scripture, and our society rightly enforces laws against it.

What this law does do is remind parents of their responsibility for their children’s spiritual and moral training (compare Eph. 6:4). It also implies that society at large and the community of faith especially must help parents do their job, backing them up with resources and support. The goal of all discipline should not be punishment and control but rather encouragement toward true life and the freedom that comes from living responsibly.

More: Scripture provides numerous resources for parents as they try to nurture their children in the ways of the Lord. See “Help for Families” at Heb. 12:3–13.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

Ever since the time of Cain (Gen. 4:17), human communities and the rule of law have aimed at keeping the family from disintegrating, a goal that lies behind Mosaic laws concerning marital purity.

After a wedding celebration that lasted eight days, a groom and bride retreated to their home to consummate their marriage. If the husband then alleged that his wife was not a virgin—whether as a legitimate complaint or as an excuse to annul the marriage—he could not simply divorce her, abandon her, or take revenge on his in-laws. He had to take his case before the elders, who placed the woman’s parents—not the woman—on trial (Deut. 22:15). The elders would consider evidence of the bride’s sexual activity prior to marriage and render a ruling (22:17–21).

This guarantee of due process for women set ancient Israel apart from other Middle Eastern cultures. Marriage was more than a private covenant between two adults. It was a legal commitment publicly honored by the community. Because the nation had a vested interest in healthy marriages and families, the Lord commanded that women’s rights be upheld by society, its leaders, and its legal system.

More: God intended the institutions of family, state, and church to reinforce each other. See “Inseparable Institutions: Family, State, and Church” at Gen. 2:23.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

Popular opinion today tends to assume that cities offer a lower quality of life than do suburbs, small towns, or rural areas. But the Bible spurns the idea that life is always better away from bright city lights. In fact, Scripture seems to hold city dwellers to an remarkably high standard of morality and justice.

Old Testament law held that in the country, if a man and a woman who was betrothed to another were found to have had premarital sex (possibly as a result of rape), the man should be put to death. But if the same situation occurred in the city, the woman was seen as having shared in the guilty act and therefore deserved the same punishment. The law held that rape was possible in the country, where a woman might cry out for help but go unheard, whereas in the city a woman’s neighbors would hear her cries and come to her rescue. It was so unacceptable for a city’s inhabitants not to defend their neighbors that the possibility simply did not factor into this statute.

No matter where we live, we have a responsibility to stand up for what is right. If we hear a cry for help, protection, or justice, it is our duty to respond (see “Love Every Neighbor” at Luke 10:27–37). Whether we make our home in the city or the country, God wants us to fill that place with His presence. He urges us to act against evil rather than let it destroy the people He loves.

More: Consider your worldly responsibilities by studying the articles under “Ethics and Character” in the Themes to Study index.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

God cursed the Moabites for an incident involving Balaam the seer. Twice they attempted to hire him to curse the Israelites. Yet the prophet, constrained by God, instead blessed His people three times. That might have been the end of the story, except that Balaam then evaded God’s instructions by encouraging Israel’s enemies to seduce the Hebrews into idolatry, incurring God’s judgment in the form of a plague. Learn more about this incident and the man who caused it in “The Unscrupulous Prophet” at Numbers 22:6, 7; “Baal of Peor” at Numbers 25:3; and “Playing with Fire” at Numbers 31:15, 16.

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

God told the Israelites not to “abhor” the Edomites living among them. The word comes from a root indicating an “abomination,” an object of utter loathing (Ps. 88:8; Prov. 6:16; 8:7). While it is unclear how the Israelites treated Edomite sojourners in Israel, the nation slaughtered Edomites in nearby Edom by the tens of thousands. To learn about major events in this long-standing hostility, see “The Edomites: Perpetual Enemies of Israel” at Genesis 36:9. To find out how King David’s hatred for the Edomites caused misfortune for his own family, see “How We Will Be Remembered” at 2 Samuel 8:13, 14.

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

Most people do not connect sewage with sacred things. But for the Israelites, who lived in a world without sophisticated plumbing or medical knowledge, God intervened, offering the Israelites a spiritual reason to properly dispose of their waste: “the LORD your God walks in the midst of your camp … therefore your camp shall be holy” (Deut. 23:14). The Lord promulgated laws concerning not only sanitation but also diet, leprosy, skin diseases, boils, burns, and sores. All of these laws contributed to the well-being of Hebrew society. This tells us that God cares about health and safety, topics that should concern us as well. Issues like waste disposal, clean air and water, toxic chemicals, climate change, and other environmental matters deserve our attention and faithful management.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

The religions of Canaanite tribes and neighboring nations were largely fertility cults. Ritualized sexual intercourse was a major part of these religions, which employed both male prostitutes (“perverted one,” or “dog”) and female prostitutes (“harlot”). To learn more about God’s view on ritual prostitution, see “The Abominations of the Canaanites” at Leviticus 18:24–30 and “Prostitutes in the Ancient World” at Judges 16:1.

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

The law that prohibited offering “the price of a dog” for a vow used the term dog as a figure of speech for a male temple prostitute. The Canaanites routinely practiced prostitution as a part of their religion (see “The Abominations of the Canaanites” at Lev. 18:24–30 and “The High Places” at Deut. 12:2). Despite God’s commandment, the Israelites eventually also engaged in ritual prostitution. During King Rehoboam’s reign, centers of idolatry became common, and Scripture records that there were “perverted persons” in the land, another reference to male temple prostitutes (Hebrew: qadesh; 1 Kin. 14:24; compare 15:12; 22:46; 2 Kin. 23:7).

More: When Paul called the Judaizers “dogs” (Phil. 3:2), he may have been paying them an insult by comparing them to male temple prostitutes common in the Greek and Roman world. To learn more about first-century views on prostitution, see “Harlots Enter the Kingdom” at Matt. 21:31, 32.

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

God does not subscribe to the opinion that contracts are made to be broken. He expects people to fulfill their vows and promises, especially pledges made before Him. As the Law pointed out, there is no sin in not making promises. But once we commit ourselves, we sin against God if we fail to follow through (see “Making Promises to God” at Num. 30:2).

More: Keeping one’s word is one of five traits that make for a godly work ethic; read Titus 2:9, 10.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

Divorce was not uncommon in the ancient world. In fact, it may have been easier to procure a divorce during Bible times than during some other periods of history, though the procedures and outcomes usually favored men. The advent of the Law did not prohibit divorce but did seek to prevent God’s people from treating marriage casually.

An Israelite husband could initiate an official “certificate of divorce” to dissolve his marriage on the grounds of a wife’s “uncleanness” (literally “a thing of nakedness”). Scholars are not sure what “uncleanness” entailed in this situation, but whatever it was, it was considered sufficient cause for divorce. The Law spoke less about divorce in general than about whether a previously divorced couple could remarry after the wife had married and divorced a second time. The statute seems to have been aimed at preventing people from moving in and out of marriages in a way that trivialized the institution (compare Jer. 3:1).

Various traditions disagree as to whether Christians are permitted to divorce. But several biblical principles suggest that settling questions about divorce should begin with a proper understanding of marriage.

1. Marriage is a holy institution established by God. When God created the world, he designed male and female to be united in marriage (Gen. 1:27; 2:24). The marital union should be characterized by singular faithfulness to this most sacred of human bonds.

2. Marriage is based on commitment. Whether partners marry for love or follow customs of arranged marriage, God expects husbands and wives to honor their union with exclusive, lifelong commitment (Matt. 19:6).

3. God hates unfaithfulness. A primary cause of divorce is unfaithfulness—not only sexual infidelity but also allowing wandering affections to destroy trust, commitment, and communication. In some cases the men of Israel consorted with prostitutes, divorced in order to take pagan wives, and even divorced and remarried in order to collect dowries. God’s hatred of divorce (Mal. 2:16) flows from His hatred of unfaithfulness.

4. Divorce is a concession. As Jesus explained, God hates divorce, but He permits it as a concession to humanity’s fallen nature (Matt. 19:8). Divorce had become routine in the cultures surrounding Israel. The Law limited the abuse of divorce among the Hebrews.

5. Grounds for divorce are few. The Bible offers few instances when divorce is permissible. (It was never mandated, except when Ezra commanded certain Jews returning from the Exile to end their marriages to pagans; Ezra 9–10.) The New Testament allows two reasons for divorce: adultery (Matt. 5:32; 19:9) and a Christian’s desertion by an unbelieving spouse (1 Cor. 7:12–16). There may be other valid circumstances not explicitly addressed in Scripture, such as persistent physical or emotional abuse.

6. The divorced need compassion. As much as God hates unfaithfulness and divorce, He offers compassion to any who fall short of His expectations. He readily forgives and restores people who seek His pardon. Divorce, whatever the grounds, is neither a decision to take lightly nor an unforgivable sin.

Divorce acknowledges that sin wreaks havoc on God’s design. Yet despite this reality, it should not be the first or only response to a troubled relationship. Marriage is so important that partners should pursue every means possible to preserve its sacred bond. Friends, churches, or professional counselors can assist struggling couples. Most of all, help is available from God Himself, who longs to see marriages succeed.

More: Jesus expressed high expectations for married couples. Find out more about His teaching on marriage in “The Challenge to Commit” at Matt. 19:1–15.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

The Stranger, the Fatherless, and the Widow

Developed nations generally administer economic assistance for the poor through networks of government agencies and nonprofit organizations. In ancient Israel, private citizens were responsible for helping the poor. Gleaning was a primary mechanism for caring for the needy (see “Gleaning and the Poor” at Lev. 19:9, 10).

Gleaning allowed the poor to enter a field, orchard, or vineyard after the main harvest and gather whatever the harvesters had missed or intentionally left for them. The Law encouraged landowners not to be overly zealous in gathering produce from their fields but to purposely leave food behind.

Deuteronomy names three classes of people likely to be poor: the stranger, the fatherless, and the widow. Strangers, or sojourners, were non-Hebrews who came to live in Canaan. Foreigners were given many rights among the Israelites, but they could not own land and often slid into poverty. The fatherless and widows tended to be poor because they lacked a patriarch to provide for their needs and defend their rights.

The Israelites’ emphasis on assisting the poor provides a compelling argument for us to help the disadvantaged today. We may debate the best means of delivering help, but the ends are clear: to see that all people’s basic needs are met even if they cannot provide for themselves.

More: Allowing the poor to glean fields and vineyards was a form of charity suited to ancient Israel’s economy. See “Modern Gleaning” at Lev. 19:10. The Israelites’ own humble beginnings created an obligation to show compassion and justice to the disadvantaged. See “Remember Where You Started” at Deut. 15:15.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

When the Israelites eventually entered the Promised Land, the first thing they were commanded to do was to worship God with produce from their first harvest. Likewise, Christians today are commanded to place Jesus, the Lord of all of life, at the top of their priorities. No matter what else occupies our days, we are to put Him first. Every aspect of life offers opportunities to honor our Savior.

• At home: how we communicate with our spouse, our approach to resolving conflict, how we demonstrate love to our children.

• In our work: how we perform our jobs, the way we deal with coworkers and customers, our priorities in spending our earnings.

• Among our neighbors: our manner of debating issues of public policy, the projects we champion, our allocation of resources, our treatment of others, the justice we show to the powerless.

Others can tell a lot about us by what we put first and foremost in life. Putting Christ first is the only way to achieve true balance.

More: Jesus affects not only our private lives but everything we do in public. See “Faith for Modern Life” in the front matter.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

The Israelites were obligated to pay ten percent of their income every third year to provide material assistance to the Levites and the poor. Neither group owned any land, leaving them no access to the means of production. The tithe provided for their needs (compare Deut. 14:28, 29). After presenting the tithe, the Hebrews were to declare before the Lord that they had fulfilled their obligation. In exchange, God committed to blessing their land with abundance. A cycle of obedience and blessing would ensure that no one experienced deprivation. Yet over the centuries, countless complications were added to the law of the tithe, so that by Jesus’ day, tithing had become a corrupted ritual with no resemblance to the original law (Matt. 23:23, 24; see also “Anonymous Givers” at Matt. 6:1–4).

More: Tithing was intended not as a burden but as a joyful celebration of God’s blessing. See “Celebrating Abundance” at Deut. 14:22–26. The tithe was in effect a ten percent tax. To find out more about taxes in the ancient world, see “Taxes” at Mark 12:14.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

The monument on Mount Ebal was part of an elaborate set of symbols designed to remind Israel that following the Law was a life-and-death matter (see “Signing Off on the Covenant” at Deut. 27:11–13). Like the successors of Moses, leaders now can use symbols to communicate meaning and values. Symbols help achieve several objectives:

• celebrating the history of an organization, along with the values and people that shaped it;

• orienting newcomers by showing what matters and why;

• communicating core values by emphasizing, explaining, and enacting fundamental beliefs and principles; and

• setting standards that establish identity, measure progress, and enforce accountability.

Every group—family, company, community, and church—has symbols. Sometimes symbols should be carefully preserved, and sometimes a change may be needed. Symbols are powerful creative expressions that remind us of what matters most, so leaders should be vigilant in guarding their significance.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

Moses devised an elaborate and memorable way for God’s people to sign off on the Law they were to keep as they inhabited the Promised Land. The plan involved two mountains in central Canaan, Mount Gerizim and Mount Ebal. Moses had earlier designated these two peaks as the sites for the occasion (Deut. 11:26–32). Now he filled in the details for what would occur.

Six tribes were to stand on Mount Gerizim and six on Mount Ebal. The summits of the two hills lay about two miles apart. The valley between formed a natural amphitheater that made it possible for a speaker on either mountain to be heard on the other. A monument to the Law would be erected on Mount Ebal, and sacrifices offered (27:1–8).