![]()

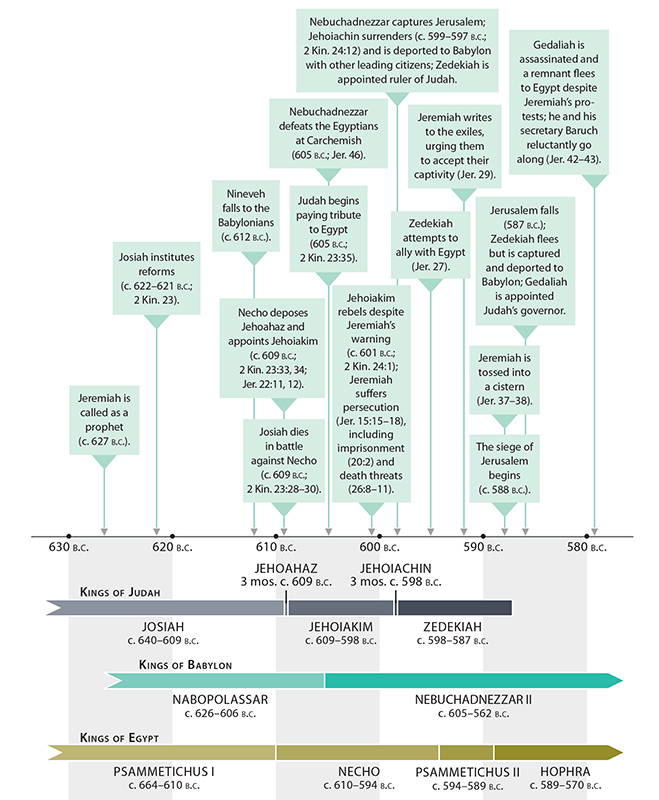

Jeremiah in Chronological Order

Jeremiah’s ministry extended through the administrations of five kings and one governor. But the Bible does not present the prophet’s material chronologically. This table suggests one possible sequence.

Josiah: 31 Years (640–609 B.C.)

Jehoiakim: 11 Years (609–598 B.C.)

Jehoiachin: 3 Months (598 B.C.)

Zedekiah: 11 Years (598–587 B.C.)

Gedaliah and after

Unknown

![]()

Name means: “The Lord Hurls.”

Not to be confused with: Eight other men in the Old Testament with the same name, including a Rechabite mentioned in the Book of Jeremiah (Jer. 35:3).

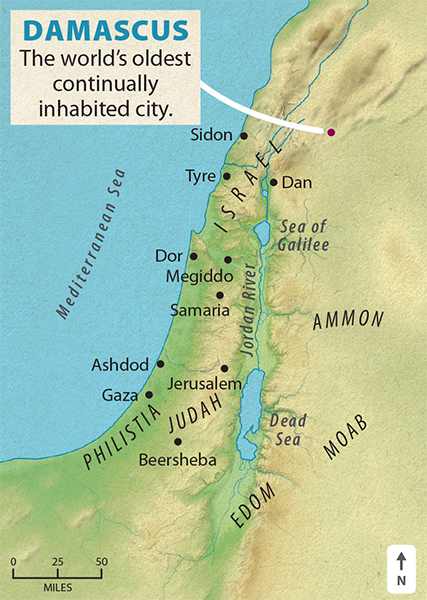

Home: Anathoth, a Levitical city a few miles northeast of Jerusalem.

Family: Son of Hilkiah the priest, not to be confused with Hilkiah the high priest who found the Book of the Law during Josiah’s reign; possibly a descendant of Abiathar, high priest during David’s reign; remained unmarried in obedience to God’s command.

Occupation: Prophet to the southern kingdom of Judah in the late seventh and early sixth centuries B.C.

Best known as: The “weeping prophet” whose tearful confessions and anguished outbursts (Jer. 8:18—9:2; 12:1–4; 20:7–18) combined with forceful denunciations of sinful society to give rise to the term jeremiad. His message of Jerusalem’s impending judgment made him many enemies and led to frequent imprisonments (37:15, 16, 21; 38:6, 28). Some traditions report that he died in Egypt after being dragged there by survivors of Jerusalem’s siege (43:1–7). Others suggest that he was moved from Egypt to Babylon after the Babylonian invasion of 587 B.C.

More: Jeremiah’s secretary was a courageous, loyal friend named Baruch. See his profile at Jer. 45:1.

Go to the Person Profiles Index.

![]()

God first spoke to Jeremiah in the thirteenth year of King Josiah’s reign (c. 627 B.C.). Jeremiah labeled himself a “youth” when he was called (Jer. 1:6), implying that he was in his teens or early twenties at the time and that he had grown up under the reigns of Manasseh (c. 686–642 B.C.) and Amon (642–640 B.C.). Manasseh led Judah into sins more depraved than the offenses of the nations driven out of Canaan (2 Kin. 21:9, 11). Amon reigned only briefly, but he continued his father’s evil acts. The sins of these two kings included …

• Rebuilding the idolatrous “high places” (see “The High Places” at Deut. 12:2) earlier removed by Manasseh’s father Hezekiah (2 Kin. 21:3).

• Reviving Baal worship (21:3).

• Initiating worship of Assyrian gods (21:3).

• Building pagan altars in the temple (21:4, 5).

• Erecting an Asherah pole in the temple (2 Kin. 21:7, 8; see also “The Gods of the Canaanites” at Deut. 32:39).

• Practicing child sacrifice (2 Kin. 21:6).

• Engaging in occult practices such as soothsaying, witchcraft, and consulting mediums (21:6; see also “The Seduction of Spirits” at Deut. 18:9–14).

• Filling Jerusalem with innocent blood (2 Kin. 21:16).

As a result of these sins, God promised devastating calamity (21:12). The people’s fate had been foretold even before Jeremiah was born, and the prophet was called from the womb to proclaim God’s impending judgment (Jer. 1:5, 9, 10). Despite Josiah’s extraordinary reforms (2 Kin. 23), Judah would be conquered and led into exile.

More: Few of God’s followers experience Jeremiah’s dramatic call, but we are called nonetheless. See “Different Callings, Same Purpose” at Ezek. 2:1–5.

![]()

The Life and Times of Jeremiah

Events shown by approximate date unless otherwise noted.

Go to the Timeline Index.

![]()

When the Lord called Jeremiah to prophesy to Judah and beyond, Jeremiah protested that he was too young for the job. He must have been intimidated by the stern and even violent responses he imagined receiving when he spread the news that God would judge his elders’ sins.

People who are young or new in their calling sometimes fear standing in opposition to the prevailing culture of their surroundings, even when that culture rejects biblical values. But consider these thoughts:

• God sends us. He sets us up as His representative in purposeful locations—family, community, the workplace—to seek His glory, not our own.

• God instructs us. We can trust the Lord to speak through His Word, His followers, and their prayers.

• God empowers us. The Lord will lift us up beyond what we can accomplish on our own in order to use our abilities in His way, in His time, and for His glory.

More: Timothy apparently felt inadequate to be a leader in the faith because of his youth. Read the Lord’s message to him in 2 Tim. 1.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

Seeing a nation filled with idolatry prompted Jeremiah’s sarcastic remark that Judah had as many gods as it had cities. This nationwide apostasy started when King Manasseh built so many pagan worship sites that the people of Judah became even more idolatrous than the Canaanites who once inhabited the Promised Land (2 Kin. 21:1–11). Pagan shrines spread from hills and mountains to valleys, towns, and individual homes. Manasseh’s successor Josiah heeded Jeremiah’s rebuke and destroyed these sites throughout both Judah and the former northern kingdom of Israel (23:4–20).

More: Despite being commanded to destroy centers of pagan worship, the Israelites who conquered Canaan let them stand and sometimes attempted to adapt them into worship of the Lord. See “The High Places” at Deut. 12:2.

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

As Jeremiah demanded that God’s people forsake their idols, he charged them with serious offenses: spiritual adultery, treachery, backsliding, breaking the Lord’s commands, and disobeying God’s voice (Jer. 3:9–13). Despite these sins, God invited the nation to reconcile with Him and obtain His mercy and healing. His people should return to Him by confessing and abandoning sin (3:13, 22).

This call to repentance also revealed God’s love for every nation. Once Israel had returned to the Lord, all nations would gather to Him in Jerusalem. People from all over the world would quit following the “dictates of their evil hearts” (3:17) and serve God.

The Lord’s offer of salvation still extends to everyone on earth, and His people remain His primary means for drawing the world to Himself. Judah’s unfortunate history should push us to ask ourselves whether our sins keep others from the Lord. Our repentance may be the door that opens for others to also repent and come to know God.

And you will not prosper by them.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

The “lion” coming up from the thicket was the Babylonian empire. Babylonia was indeed a “destroyer of nations.” In 612 B.C. King Nabopolassar led a coalition of Babylonians, Medes, and Scythians against Nineveh, the Assyrian capital. They took the city by siege and left it in ruins. Jerusalem soon faced similar devastation, as did many other Middle Eastern city-states. For nearly a century, Babylon held the region with an iron grip.

More: Assyria’s capital Nineveh was considered impregnable, but the Babylonians destroyed it nonetheless. See “The Fall of Nineveh” at Nah. 2:6–8.

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

The prophets often compared Jerusalem to Sodom, an ancient city destroyed for persistent rebellion. The Lord would have spared Sodom had He found within it even ten righteous people, but the city fell short (Gen. 18:32, 33; 19:24, 25). The Lord promised to preserve Jerusalem if it contained only one righteous citizen, but Jeremiah searched in vain for that one. He found that the poor were ignorant of justice and truth (Jer. 5:4), and leaders who could read the Law, rediscovered by Josiah (2 Kin. 22:8—23:3), had nevertheless left God’s ways (Jer. 5:5). Jerusalem was doomed.

How would God evaluate our communities? Are they as lacking in morality as Sodom—or Jerusalem? If Jeremiah searched our hometowns for God’s followers, would he count us among them? How many others would he find?

More: God destroyed Sodom and three other “cities of the plain” for sins such as sexual immorality and failure to care for the poor. See Sodom and Gomorrah’s profile at Gen. 18:20.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

The massive walls of ancient cities were difficult if not impossible to breach. An enemy might attempt to topple or tunnel under a wall or burn city gates. Jeremiah predicted that Jerusalem’s attackers would employ an alternative strategy—a siege ramp constructed by piling up dirt, boulders, trees, and other debris against a city wall. Soldiers marched up a completed ramp and fought their way over the wall. A ramp built by the Romans still exists at the fortress of Masada in southeastern Israel.

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

Devout religion involves caring for orphans and widows and keeping oneself morally untainted (James 1:27). By that measure, the religion of Jeremiah’s day could not have been more lacking. The people …

• failed to act justly in business,

• oppressed the weak and disadvantaged,

• committed manslaughter,

• practiced idolatry,

• stole from each other,

• committed adultery, and

• lied under oath and went back on their word (Jer. 7:5–9).

And yet even after committing these “abominations,” the Lord’s people came to the temple expecting God to bless them (7:10). They believed the false prophets who assured them that prosperity would continue as long as they kept up a pretense of worship (7:4, 8). The Lord told Jeremiah to stand in the temple gate and denounce this hypocrisy and warn the people to change their ways (7:1–3). God was not looking for pious words but for altered behavior. If we claim to be God’s people, we must worship Him with more than words.

More: Like Jeremiah, Isaiah said that true worship must include public service and an advocacy of social justice. See “Worship and Service” at Is. 58:6–12.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

Shiloh was once home to the tabernacle, the center of Israel’s religious life (see Shiloh’s profile at 1 Sam. 1:3). But now the city lay in ruins. Citizens of the northern kingdom had been taken captive by the Assyrians after they rejected the Lord in favor of idols. Jeremiah warned that the residents of Jerusalem could expect the same fate—and for the same reason.

The thought of judgment must have seemed preposterous. Jerusalem was the site of the temple, the magnificent house of worship that David had envisioned and Solomon had built for God’s glory (see “Solomon’s Temple” at 2 Chr. 5:1). But if anyone doubted Jeremiah’s warning, they could have seen evidence of judgment little more than twenty miles north at Shiloh. Unfortunately, few people heeded the prophet’s word, because within a few years, Jerusalem fell to the Babylonians. The temple was burned, its residents killed or deported.

Idolatry is letting anything take God’s place (see “Modern-Day Idols” at Is. 46:5–10). Shiloh teaches us that God sometimes takes away the object of our affections to redirect our attention to Him.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

Jerusalem’s future was grim. By the time Jeremiah arrived on the scene to speak for God, sin was openly tolerated and obvious to all. God’s people habitually engaged in fraud, corruption, sexual immorality, injustice, murder, and idolatry. The Lord promised a firestorm of judgment (Jer. 4:4; 5:14; 6:29; 7:20).

The Lord told Jeremiah to cry out to his fellow citizens to avert the wrath coming on a day of “disaster from the north” (4:6–9, 20; 6:1–5, 19; 10:22). The imminent Babylonian invasion could be avoided if Judah returned to God and reaffirmed its covenant with Him (3:12—4:4; 7:5–7). But the prophet was severely persecuted for his unpopular warning, and the people refused to come back to God.

No one knows whether modern cities stand under God’s impending judgment. But where we see sin like what became the norm in Jerusalem, we know by God’s character, revealed in Scripture, that He will not allow evil to go unchecked forever. There were several reasons why Jerusalem fell under God’s wrath:

1. Jerusalem lost its vision. God established Jerusalem as a city of justice, a model of peace, and a light to the nations. But its citizens forgot their special place in God’s plan (2:2–7). Rulers, prophets, and priests left their holy calling to pursue unholy alliances and false gods (2:8–37; 5:31; 7:1—8:3; 10:1–16). Jerusalem became as wicked as Sodom (23:14; Lam. 4:6; see also “Not One Righteous Person” at Jer. 5:1).

2. Leaders failed to address problems. Despite King Josiah’s reforms (3:6; 2 Kin. 22–23) and Assyria’s sobering decimation of Israel (Jer. 3:7–10), Judah continued to rebel. Jerusalem’s leadership pursued worthless idols (2:11), vain wealth (4:30), and illusory power (2:36, 37). These predators took the necessities, property, and even the lives of others (5:26–28). No one upheld justice and truth (5:1). The blood of “poor innocents” was spilled not in secret but plainly for all to see (2:34). And where there should have been justice and mercy, there was injustice and idolatry. Instead of addressing the city’s failures, leaders offered only false assurances: “Peace, peace!” they cried, when there was no peace (6:14; 8:11).

3. Citizens chose to do nothing. A century earlier, the Lord had allowed Israel to be ransacked as a result of the people’s idolatry and other sins (7:12–15; 2 Kin. 17). Now Judah had crossed the line of rebellion. Measured by God’s standards, the nation was found wanting, even more than its “stiff-necked” forefathers in the wilderness (Jer. 7:23–26). Judah could avoid destruction, waste, and captivity by thoroughly amending its ways (7:5–7), or it could remain hard-hearted. The nation’s existence depended on its choice. But Jerusalem and the cities of Judah did nothing to mend their ways.

Many modern communities face social, moral, and spiritual problems like those of Jerusalem—and they face similar opportunities for renewal. While God’s specific promises to Jerusalem do not necessarily apply today, any community can expect God to bless efforts to remove immorality, greed, corruption, and violence. Our well-being is connected to the well-being of our communities. “Seek the peace of the city,” Jeremiah wrote to the captives in Babylon, “for in its peace you will have peace” (29:7).

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

The process of gathering wood, kindling a fire, and preparing cakes for the “queen of heaven” probably refers to making incense or meal offerings to Anath, mistress of the Canaanite idol Baal. See “The Gods of the Canaanites” at Deuteronomy 32:39.

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

God’s people faced the consequences of turning from Him—they “went backward and not forward.” Instead of pursuing a relationship of sustained obedience, they went their own way and chased the “dictates of their evil hearts.”

Faith is a lifelong journey. At any moment, we either move backward or forward. We make progress when we step toward the Lord as best we know how. If we fail and fall, God invites us to get back on our feet and move forward to Him. Paul described his own experience of this dynamic spiritual movement: “Forgetting those things which are behind and reaching forward to those things which are ahead, I press toward the goal for the prize of the upward call of God in Christ Jesus” (Phil. 3:13, 14).

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

The high places of Tophet in the Valley of the Son of Hinnom were the scene of the Israelites’ most gruesome sins—child sacrifices conducted during the reigns of Ahaz and Manasseh. King Josiah destroyed this pagan altar (2 Kin. 23:10), but Jeremiah warned that God would judge Judah nonetheless. Part of that judgment included a name change: the Valley of the Son of Hinnom would be called the Valley of Slaughter. For more, see “The Valley of Hinnom” at Joshua 18:16.

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

Jeremiah’s world grew more dangerous by the day. The declining Assyrian empire created an atmosphere of political instability. Seeing an opportunity for its own advancement, Egypt launched offensive campaigns from the south. Babylon was also on the rise as a new superpower.

Despite these ever-increasing threats, false prophets comforted Judah with peace-filled words. Citizens huddled in their walled cities, assuming that their defenses ensured safety from hostile forces (Jer. 8:14). And they ignored the gravest danger of all: sin was already inside their gates, because they had turned their backs on God (8:5, 8–12).

We might attempt to find safety today by moving to the suburbs or settling inside gated communities. But evil is not easily excluded (8:15). It cannot be stopped just by controlling our environment, because we bring sin with us wherever we go. The only lasting way to deal with sin is through repentance (25:4–7; 35:15; Matt. 11:28). God does not fault us for protecting ourselves and our families. But true peace does not come from shutting out external evil. We must also stop sin inside.

More: For a different take on the challenges of urban life, see “The Ten Percent Solution” at Neh. 11:1, 2 and the articles under “Urban Life” in the Themes to Study index.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

Jeremiah’s prophecy likened Babylon’s invading armies to deadly snakes, an image that recalled an incident from the days when the Hebrews’ ancestors wandered in the wilderness. The people’s incessant, ungrateful complaints caused the Lord to send venomous serpents among them (Num. 21:6). After they had repented, Moses, following the Lord’s instructions, crafted a bronze serpent and lifted it on a pole to offer healing to the dying (21:8, 9).

But although many survived this earlier event, nothing would now be able to turn away Nebuchadnezzar’s troops. The “serpents” coming to Jerusalem in Jeremiah’s day were “vipers which cannot be charmed.” The Babylonians would fulfill the Lord’s longstanding vow to send the “poison of serpents” against His unfaithful people (Deut. 32:24).

More: Snake charmers were common in the ancient Middle East. Cobras were especially popular, and training them was considered an occult art. Snake charming and the worship of serpents may have been among the evils practiced in Jerusalem in the days leading to its destruction (2 Chr. 28:2, 3; Ezek. 8:9, 10; see also “The Seduction of Spirits” at Deut. 18:9–14).

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

Prophets are often portrayed as angry, wild-eyed people who probably enjoy predicting others’ misfortunes. Jeremiah in no way fit that stereotype. As he reflected on Jerusalem’s impending destruction, he didn’t sneer or gloat. His heart broke for his people and their grand city. And even as the peril advanced, Jeremiah did not abandon his fellow citizens. This weeping prophet may have wanted to flee to safety in the wilderness, but he stood by the doomed of Jerusalem.

The Lord’s true messengers are not numb to the pain and suffering they foresee. They are driven by compassion, not rage. Their aim is to heal and to help others avert danger, not to hasten or triumph over their misfortunes.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

The covenant between Israel and the Lord stipulated blessing for obedience to the Law and judgment for disobedience (Lev. 26; Deut. 28). The judgments progressed in severity from economic hardship to disease and drought to military defeat and foreign oppression to siege and exile. The Lord warned that He would scatter the disobedient “among all peoples, from one end of the earth to the other” (28:64).

This scattering, or dispersion, began when the northern kingdom of Israel fell to the Assyrians in 722 B.C. Later, after the Babylonians conquered more and more of Judah in 599–586 B.C., relatively few Jews returned to Palestine (see “The Journey Back to Jerusalem” at Ezra 2:1). The vast majority were scattered abroad, fulfilling the conditions of the Law and Jeremiah’s prophecies (Jer. 13:24).

1. Captives from the northern kingdom were resettled by the Assyrians in the Habor River region, the district of Nineveh, and Media. It is presumed that they were eventually absorbed into these communities. Meanwhile, Israel was repopulated by outsiders (2 Kin. 17:24).

2. Exiles from Judah were relocated by the Babylonians to villages along the Chebar River between Babylon and Nippur. The majority remained in Babylon, establishing a Jewish community that continued into the Middle Ages.

3. Under the Seleucid empire (third century B.C.), Jewish settlements were established throughout Mesopotamia and Asia Minor. Many of these were later represented at Pentecost (Acts 2:9–11). However, Jews were not always welcome among the Gentile majority (16:20; 19:34). In the capital of Seleucia, 50,000 were killed in a massacre during the first century A.D.

4. Substantial numbers of Jews migrated to Italy by the second century B.C. A proclamation in 139 B.C. ordered their expulsion from Rome, but it was ultimately ineffective, as were similar decrees in later years (compare Acts 18:2; 28:17).

5. Cyrene had a population of 100,000 Jews in the first century A.D.

6. Many survivors of the Jerusalem siege fled to Egypt, settling along the Nile in colonies that endured for centuries. They were later joined by other immigrants from Palestine. Some of the more noteworthy settlements were at Yeb (Elephantine), Thebes, Noph (Memphis), Tahpanhes, Alexandria, and Migdol. By the first century A.D., more than one million Jews are believed to have been living in Egypt.

7. Large Jewish colonies were established in Syria by the first century A.D.

More: The dispersion of the Jews throughout the world helped the gospel spread rapidly in the first century A.D. See “The Dispersion of the Jews” at Jer. 52:28–30 and “The Nations of Pentecost” at Acts 2:8–11.

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

Jeremiah’s sobering message declares that God is against all sin. His wrath falls on the wrongdoing of every individual and nation, whether Jew (“circumcised”) or Gentile (“uncircumcised”). As Paul put it, “The wrath of God is revealed from heaven against all ungodliness and unrighteousness of men” (Rom. 1:18; emphasis added).

The Bible declares that all people have sinned and stand under God’s judgment (3:10–18, 23). No individual is exempt. No group has special privileges. And God leaves no room for bargaining. He will judge peoples from every corner of the earth and throughout time. He sees no difference between the failings of man or woman, or the deficiencies of cultures ancient or modern. The sins of one are as serious as the sins of another.

This is the bad news that makes what Christ accomplished on the cross very good news. Yet even this worst of news shows that God is as evenhanded in judgment as He is in mercy and grace (3:29, 30). He warns of judgment for all, and He offers life to all. No one can hide from His all-seeing eyes, but no one has to miss out on His salvation.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

The Lord vowed to overthrow the false gods that proliferated in Judah (see “A God for Every City” at Jer. 2:28). The Lord is the all-powerful Creator, but idols are completely without power. They are a “work of errors” and a “worthless doctrine” (Jer. 10:8). The Lord’s declaration that He is God and there is no other is in direct conflict with widespread modern ideas about God and religion. But on this point God leaves no room for compromise.

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

The Unsilenced Voice

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (1918–2008) grew up during an era of internal strife in Russia that toppled the nation’s tsarist rulers and ultimately led to the rise of the communist Soviet Union. He became a leading dissident voice against Soviet oppression and atheism, and later stridently spoke against the materialism and moral decline of the Western world.

Solzhenitsyn’s father was a philosophy student who enlisted in the Russian army in 1914. He died in a hunting accident in 1918, six months before his son’s birth. Aleksandr was raised in modest circumstances, and their family property was confiscated and made into a collective farm. His mother quietly raised him in the Russian Orthodox Church and pushed him to further his education. Solzhenitsyn was not yet twenty when he began to conceive a grand work on World War I and the Russian Revolution.

The young thinker became an artillery captain during World War II and was decorated for his service. But he soon grew disgusted by the brutal violence he witnessed his fellow soldiers take as “revenge” against innocent women and children who were considered Russia’s “enemies.” Solzhenitsyn reacted by privately criticizing the Soviet Union’s dictatorial premier Joseph Stalin, a crime for which he was sentenced to eight years in a forced labor camp. His internment in the Gulag was followed by internal exile for life in Kazakhstan. He was freed from exile and exonerated, however, after a 1956 speech by Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, who criticized the brutal purges of his predecessor.

A decade of imprisonment and exile had destroyed Solzhenitsyn’s trust in the Soviet system, and he emerged a philosophically-minded Christian who saw himself as culpable as his tormenters in the Gulag. Solzhenitsyn’s spiritual awakening had occurred as a result of a conversation with a physician who worked in the Gulag’s infirmary. Dr. Boris Nikolayevich Kornfeld recited the story of his conversion from Judaism to Christianity, and described his belief that no punishment is undeserved, for no person is without sin. “If you go over your life with a fine-tooth comb and ponder it deeply,” Kornfeld remarked, “you will always be able to hunt down that transgression of yours for which you have now received this blow.”

The next morning, Solzhenitsyn awoke to the news that his new friend had been brutally murdered. “And so it happened that Kornfeld’s prophetic words were his last words on earth,” wrote the prisoner, “and those words lay upon me as an inheritance. You cannot brush off that kind of inheritance by shrugging your shoulders.” After much deliberation, Solzhenitsyn came to the conclusion that the meaning of life lies not in prosperity or lack of punishment, but in the development of the soul.

After his release, Solzhenitsyn taught school by day and wrote in secret by night, building on writings he had begun during his imprisonment. He feared discovery and assumed his work would never reach print. But Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich was freely published in 1962, defended by Khrushchev as an aid to rooting out lingering Stalinism. The book sold out in the Soviet Union and gained attention in the West as the first honest Soviet publication since the 1920s.

Just as quickly as he was officially acclaimed, however, Solzhenitsyn was discarded. He continued to covertly write his most subversive work, The Gulag Archipelago, a lengthy and explosive history of Soviet prison camps later hailed as one of the most important books of the twentieth century. Solzhenitsyn was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1970. He was expelled from the Soviet Union in 1974 and lived for almost two decades in the United States, where he lashed out at the spiritual emptiness of modern culture and the personal autonomy assumed by Westerners. He returned to Russia in 1994 after the collapse of the Soviet system.

Looking back with grief on his homeland’s history, Solzhenitsyn said, “If I were asked today to formulate as concisely as possible the main cause of the ruinous revolution that swallowed up some sixty million of our people, I could not put it more accurately than to repeat [the explanation he had heard as a child]: ‘Men have forgotten God; that’s why all this has happened.’”

Go to the Life Studies Index.

![]()

Death threats from Anathoth’s men must have been particularly dismaying to Jeremiah. Located less than five miles northeast of Jerusalem, Anathoth was set aside for the Levites (see “The Levitical Cities” at Josh. 21:1–3). It was the hometown of Abiathar the priest (1 Kin. 2:26) and two of David’s mighty men (2 Sam. 23:27; 1 Chr. 12:3). It also happened to be Jeremiah’s hometown. The neighbors of his youth apparently became his betrayers.

The Levitical city of Anathoth should have been a model of justice and righteousness. Its people should have rushed to repent when Jeremiah warned of impending disaster. In fact, the city had already been captured once, by Sennacherib’s army (Is. 10:30), but Anathoth nevertheless rejected God’s message and messenger. As a consequence, God singled out Anathoth for destruction (Jer. 11:22, 23), an event that likely transpired during one of Babylon’s sieges of nearby Jerusalem (c. 599–597, 588–587 B.C.).

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

The cultures around Israel taught the Lord’s people to “swear by Baal,” that is, to worship and serve their gods. This idolatry broke Israel’s covenant with the Lord and led to the nation’s captivity.

These “evil neighbors” may have been remnants of the Canaanite tribes dispelled from the land by early Israelites. They could have been nations marched into captivity alongside Judah, such as Moab, Syria, and Ammon. Or they may have been the Babylonians, captors of the Lord’s people in exile. The Israelites imported and worshiped gods from all three of these groups.

Whatever the identity of these “evil neighbors,” God reached out to them with an amazing promise: He would allow them to learn about Him, just as they had taught the Israelites about their gods. Rather than destroying them for leading His chosen people into sin, the Lord gave them an opportunity to turn from their worthless idols and serve the true God.

This gesture of grace demonstrates God’s open heart for every person. It proves the truth that Peter later expressed: the Lord does not wish for anyone to perish but for all to repent (2 Pet. 3:9).

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

The linen sash was an appropriate symbol for proud Judah. Costly linen (Is. 3:23) was often imported from Egypt (Prov. 7:16). It was saved for exquisite furnishings like those inside the tabernacle (Ex. 26:1, 31, 36) or for fine garments worn by priests (28:39) or favored people (Esth. 8:15; Ezek. 16:10, 13).

The Lord at first warned Jeremiah not to let his linen sash get wet—in other words, to avoid ruining the costly material. But later God instructed the prophet to hide the sash along the Euphrates River to allow water to spoil the belt. It became a powerful image of Judah—a people intended for worthy purposes now rotted and worthless because of sinful arrogance. Just as Jeremiah’s sash was ruined, so the pride of God’s people destroyed their ability to fulfill His purpose. Their evil ways made them “profitable for nothing” (Jer. 13:10).

More: Jeremiah often acted out parables and employed word pictures to convey truth. See “The Parables of Jeremiah” at Jer. 18:1–10.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

Farmers in ancient Israel separated kernels from chaff by beating grain to dislodge the kernels, then tossing everything into the air. Stiff eastern winds known as the “wind of the wilderness” (see “The Four Winds” at Ps. 48:7) carried away the light chaff as heavy kernels fell to the ground and were collected for grinding. The Lord vowed to blow away disobedient Judah like this chaff, or “stubble,” scattering His people far and wide. This judgment had been declared centuries earlier and was partly fulfilled during Jeremiah’s lifetime as part of a long-term migration of Israelites out of Palestine. See “Scattered Among the Gentiles” at Jeremiah 9:16 and “The Dispersion of the Jews” at Jeremiah 52:28–30.

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

The droughts that Judah suffered were proof that God keeps His word. Hundreds of years earlier, God had promised that He would bless the land so long as His people followed the Law. If they disobeyed the Law and worshiped other gods, the Lord would turn annual rains to “powder and dust” (Deut. 28:24; compare Lev. 26:18, 19).

As Judah surpassed Israel in idolatry and wickedness, the Lord kept His word by sending a series of droughts. Jeremiah pleaded for mercy, but God told him that it was too late. He had already put Judah’s discipline into motion (Jer. 14:11, 12).

There was irony in sending drought as punishment. The Israelites had abandoned God to worship Canaanite gods who supposedly had power over nature (see “The Gods of the Canaanites” at Deut. 32:39). By holding back rain, God demonstrated the futility of these idols (Jer. 14:22).

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

Throughout his ministry, Jeremiah endured intense persecution because of his boldness for God. In this he was not alone. Another prophet named Urijah also spoke out against the evil policies and practices of Jerusalem’s leaders. He was sentenced to die and fled to Egypt, but King Jehoiakim had Urijah extradited and put to death (Jer. 26:20–23).

Leaders later turned on Jeremiah, launching verbal attacks and plotting to kill him (18:18). They eventually put him on trial for speaking against Jerusalem, a crime for which they demanded the death penalty (26:10, 11). An official named Ahikam intervened and was able to spare Jeremiah’s life (26:24), but the prophet was nevertheless imprisoned for his message. He was vindicated when his prediction that Jehoiakim would not die peacefully in Jerusalem (22:18, 19) came to pass around 598 B.C. (2 Chr. 36:5, 6).

More: Watchman Nee and Eric Liddell were also imprisoned for their faith. See here for an article on the life of Watchman Nee. See here for an article on the life of Eric Liddell.

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

A parable is a truth wrapped in a memorable story or word picture. A parable can be fictional, dramatized, or the result of a vision. Jesus delivered much of His teaching through parables (see “The Parables of Jesus” at Luke 8:4) as did several Old Testament prophets. Note Jeremiah’s parables and the points he made:

1. The Boiling Pot (Jer. 1:13–16)

Symbolized God’s impending judgment of idolatrous Judah.

2. The Ruined Sash (13:1–11)

Illustrated the ruin that Judah’s pride had caused in its relationship with God.

3. The Potter and the Clay (18:1–10)

Showed God’s sovereign role in raising up and pulling down nations, including Judah.

4. The Broken Flask (19:1–13)

Illustrated how God would shatter Judah for its wickedness.

5. The Good and Bad Figs (24:1–10)

Demonstrated two ways that God would deal with his people: accepting good and rejecting evil.

6. The Bonds and Yokes (chs. 27–28)

Advised Judah’s leaders to submit to Babylonian rule.

7. The Deed of Purchase (ch. 32)

Testified that God would eventually bring back survivors from Babylon who would buy and sell fields in Judah.

8. The Stones in the Clay (43:8–13)

Foretold that God would allow the Babylonians to dominate Egypt.

More: Ezekiel and Zechariah also used parables to communicate their messages. See “The Parables of Ezekiel” at Ezek. 15:1–8 and “The Parables of Zechariah” at Zech. 5:1–4.

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

We reject wood and stone idols as objects of worship, incredulous that anyone could think they are gods. But just as the Israelites worshiped the work of their hands (Jer. 10:3, 4, 8, 9), we may be guilty of worshiping our handiwork, the process and product of our careers. Work easily becomes a god, the controlling center and defining identity of life.

Our society sees overworking as an acceptable, even admirable addiction. A person can sacrifice everything on the altar of work—family, friends, even personal health—and be rewarded for showing drive and initiative.

That is a profound tragedy. God designed work as a satisfying means of serving Him (see “People at Work” at Ps. 8:6). He is a worker, and He created us in His image as His coworkers (see “God the Creator” at Gen. 1:1–31 and “God: The Original Worker” at John 5:17). But work was never meant to be an end unto itself, and was certainly never intended to become an idol. Work may express who we are, but it was never meant to become who we are.

In part to keep us from idolizing work, the Lord modeled an essential principle by ceasing from His creative labors on the seventh day. In doing this He showed us that life is about more than work. Our jobs have a place in life, but there are other things that occupy more important places—and the most important place of all is that of the Lord Himself. The point of the Sabbath in the Old Testament and the Lord’s Day in the New Testament is to express our ultimate trust in and devotion to God.

We should not overlook the fact that the people of Jeremiah’s day abused the Sabbath at the same time that they engaged in rampant idolatry (Jer. 17:21–27). Sins of work and sins of worship often go hand in hand.

More: To consider other idols present in our world today, see “Modern-Day Idols” at Is. 46:5–10.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

The prophet Jeremiah used visual aids, such as a broken flask, to help his listeners grasp the meaning behind his message. It could be argued that Jeremiah’s demonstrations were unproductive, because apparently few of his listeners took his words to heart. But the prophet’s words live on today, taken to heart by many modern believers even though they were rejected in his own lifetime.

Like Jeremiah, we should do everything we can to communicate clearly and effectively to our society, and often that requires giving people something to see as well as hear. Imagery, both in language and in visual media, can be a powerful method of reaching our culture, but the most commanding way to illustrate God’s messages is to act as a living example of His ways. Our lives are the clearest communicators of our hearts.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

The “dead” for whom Jeremiah was told not to weep may have been King Josiah, Judah’s boy king who grew up to accomplish nationwide reforms.

Josiah died in battle against Pharaoh Necho of Egypt, who was advancing north to help the Assyrians fend off the Babylonians. Josiah may have gathered his army against the Egyptians because he saw Necho’s trespass through Canaan as a challenge to Judah’s sovereignty.

Whatever Josiah’s reasoning, the Egyptian king warned him not to attack, insisting that God had summoned him to aid the struggling Assyrians. But Josiah ignored Necho’s advice and marched into battle, where he was mortally wounded by Egyptian archers (2 Chr. 35:20–24).

This was a critical loss for Judah. It ended the spiritual revival under Josiah, and it signaled the beginning of the end for the nation. Even before Josiah was born, God had warned that judgment was imminent (2 Kin. 21:10–15). He reaffirmed that intention to Josiah, although He promised to delay the end until after Josiah’s death (22:15–20).

Now the kingdom’s final days were at hand. Ironically, Josiah’s attack delayed the Egyptians from arriving in time to help the Assyrians, and Babylonia became master of the Middle East. Around 598 B.C., Nebuchadnezzar captured Jerusalem and deported most of its leadership. He returned around 587 B.C. to destroy the city and carry survivors into exile.

More: Josiah was the last of the God-fearing kings of Judah. See his profile at 2 Chr. 34:1 and see here for an article on his life.

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

King Jehoiakim indulged his fondness for cedar even while his people paid heavy taxes (2 Kin. 23:35) and labored for minimal wages.

Cedar was imported from Phoenicia in Lebanon. Always expensive, it was probably becoming even more costly in Jehoiakim’s time. Extrabiblical sources report that the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar was also importing huge quantities from what was a dwindling source.

Jehoiakim may have had illusions of returning the kingdom to Solomon’s glory days. But unlike Solomon, who honored the Lord in his younger years, Jehoiakim rejected God’s ways from the start of his reign (2 Kin. 23:36, 37). He would later die in disgrace, and his body would be tossed on a garbage heap like the carcass of a donkey (Jer. 22:18, 19).

More: Due to the extravagance of many ancient rulers, the forests of Lebanon were decimated by overcutting. See “The Cedar Trade” at 1 Kin. 7:2.

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

Scripture seems to suggest two ways we can know God. The first happens when we enter into and enjoy a personal relationship with Him (see “Written on Their Hearts” at Jer. 31:31–34). We can know God in this way because Christ’s death and resurrection removed the barrier of sin that separated us from Him (Gal. 4:3–9; Heb. 8:11, 12). This kind of knowing God goes hand in hand with a second way of knowing God: living a godly lifestyle. If we claim to know God, our actions should prove it (James 2:17; 1 John 1:6; 4:7).

It was on this point that Jeremiah challenged King Jehoiakim. The ruler had been appointed king by the Egyptians, who deposed his brother Jehoahaz after only three months on the throne (2 Kin. 23:31–34). Judah became a tributary of Egypt, paying one hundred talents of silver and one talent of gold, probably annually. To raise that sum, Jehoiakim levied taxes, creating hardship for the poor (Jer. 22:16, 17). At the same time, he launched extravagant building projects that oppressed the working class (22:13, 14).

On top of these sins, Jehoiakim reintroduced the idols that his father Josiah had removed (Ezek. 8:5–17) and hunted down a prophet of the Lord and had him executed (Jer. 26:20–23). God assessed this king to be a man committed only to his own covetousness (22:17).

Jehoiakim may have thought that because he was an Israelite and the son of a man who knew the Lord, he automatically knew God as well. But he was badly mistaken. Josiah matched his words with actions, living with justice and righteousness and not merely talking about them. Josiah truly knew the Lord.

Having a personal relationship with God, based on faith in Christ, is essential. And when it comes to knowing God, reflecting our relationship with Him in what we do is equally important—especially in how we treat others, particularly the disadvantaged. We must be careful about claiming to know God if we act as if we have never heard of Him (Luke 6:46–49).

More: More help in cultivating a relationship with God can be found in the articles under “Knowing and Serving God” in the Themes to Study index.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

Coniah, also known as Jehoiachin (Jer. 52:31), continued his father Jehoiakim’s evil acts (2 Kin. 24:8–9) and suffered a comparable fate, just as Jeremiah prophesied.

King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon arrived at Jerusalem around 599 B.C. to deal with a revolt by his Judean vassal, Jehoiakim. The Babylonians captured Jehoiakim and prepared to take him to Babylon in chains (2 Chr. 36:6). The Judean king died on the way, however, and extrabiblical sources report that his body was unceremoniously dumped outside Jerusalem’s walls, fulfilling a prophecy uttered by Jeremiah (Jer. 22:18, 19).

After Jehoiakim’s death, Nebuchadnezzar appointed Jehoiachin as king of Judah. Yet only three months later he changed his mind, and the Babylonians returned and laid siege to Jerusalem. Eighteen-year-old Jehoiachin immediately surrendered. He was taken captive to Babylon along with the city’s leading citizens (2 Kin. 24:10–12).

The Babylonians apparently still considered Jehoiachin king of Judah, but Nebuchadnezzar appointed his uncle Mattaniah (or Zedekiah; 2 Kin. 24:17) to rule in Jerusalem (see “A Long Layover” at Ezek. 1:2). Fulfilling Jeremiah’s word, Jehoiachin lived out his days in captivity, eventually receiving better treatment from Nebuchadnezzar’s successor, Evil-Merodach (Jer. 52:31–34).

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

Bad Shepherds and the Good Shepherd

The shepherds that Jeremiah condemned were not literal animal herders. They were Judah’s rulers, people of power and influence. These corrupt politicians led people astray, acting more like predators than shepherds (see “On the Eve of Destruction” at Jer. 7:17).

God vowed to judge opportunistic leaders (23:2). But He also promised to send a future leader who would restore the people and do what is just and right (23:5, 6; compare 33:15, 16; Ezek. 34:23–31). This is Jeremiah’s clearest reference to Jesus the Messiah, the Good Shepherd who came to care for the lost sheep of Israel (Matt. 10:5–7; John 10:1–18).

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

Indigenous to the Middle East, the fig tree grows well in the region’s stony soil. It can produce up to three crops each year. Autumn figs are the main fruit (Jer. 8:13). Winter figs ripen in early spring so long as they survive winter winds (Rev. 6:13). Summer figs usually ripen in late summer and are considered the tastiest (Jer. 24:2). Fig trees mature slowly and take years to cultivate properly (Prov. 27:18), so their destruction spelled long-term disaster (Jer. 5:17; Hab. 3:17).

More: Jesus performed a miracle involving a fig tree. To learn more, see “The Fig Tree and the Mountain” at Mark 11:12–26.

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

With its description of the “wine cup of fury” that the Lord would force the nations to drink (Jer. 25:15, 16, 27–29), Jeremiah 25 is one of the Bible’s most sobering chapters. The reason for God’s wrath is clear. He is the Creator and sovereign Lord. He revealed Himself to the Israelites through prophets like Jeremiah. Yet the entire world—Judah included—had abandoned Him to serve false gods.

The situation resembled what Paul described in the opening of Romans: “Although they knew God, they did not glorify Him as God … but became futile in their thoughts … and changed the glory of the incorruptible God into an image made like corruptible man—and birds and four-footed animals and creeping things” (Rom. 1:21–23). Every nation of that day was steeped in idolatry and stood under imminent judgment (Jer. 25:8–26).

1. Judah was among the worst (see “A God for Every City” at Jer. 2:28). God’s wrath would begin with Judah’s destruction by Babylon (25:8–11).

2. The Lord would eventually punish Babylon for its own sins (25:12–14).

The Lord’s wrath would then spread to all the other nations (25:19–26):

3. Egypt, Uz, and Philistia in the southwest.

4. Edom, Moab, and Ammon in the southeast.

5. Tyre, Sidon, and the coastlands in the northwest.

6. Dedan, Tema, Buz, and other nations in the far corners of the earth.

7. Arabia and the desert peoples, and Zimri, Elam, and Media in the east.

8. All kings of the north and all the kingdoms of the earth.

God is God, and there is no other. He is the everlasting King of all nations, and none can share His glory. The terror of His wrath against sin—particularly the sin of worshiping other gods—is worldwide in scope. No one is excluded. The Bible repeats this truth again and again, all the way to the end (Rev. 6–18).

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

Faith in God can be so unpopular that it triggers death threats. Jeremiah was threatened with death in response to his message of God’s impending judgment of Jerusalem and its people. The prophet’s influential friends prevented harm from touching him (Jer. 26:16, 24), but many others in Scripture and throughout history proved their commitment to God with their blood. Their sacrifice challenges us to examine our hearts carefully even if we live where we are not fiercely persecuted. We should ask ourselves if we would be as courageous and loyal as those who faced death for following the Lord.

Abel (Gen. 4:1–8) | Killed by his brother Cain for offering a better sacrifice to God; Jesus praised him as a model of righteousness (Matt. 23:35). |

Zechariah (2 Chr. 24:20–22) | A prophet stoned by his fellow citizens, including the previously faithful King Joash, for rebuking their idolatry; Jesus applauded him as one whose “righteous blood” was unjustly spilled (Matt. 23:35). |

Urijah (Jer. 26:20–23) | A prophet hunted down and murdered by King Jehoiakim. |

John the Baptist (Mark 6:17–29) | Executed by order of King Herod after his wife Herodias demanded John’s death for criticizing their adulterous marriage. |

Peter (John 21:18, 19) | Jesus’ follower and a leader of the early church; tradition holds that he was crucified under orders of the emperor Nero, and by his request, upside down. |

Stephen (Acts 7:54–60) | An early evangelist stoned to death by members of the Jewish Council after delivering a scathing speech implicating them in Jesus’ death. |

Unnamed martyrs (Heb. 11:37; Rev. 17:6) | Faithful people killed because of their unswerving loyalty to God. |

Antipas (Rev. 2:13) | A little-known member of the early church at Pergamos, whose death gave other followers of Christ an opportunity to stand firm for the Lord. |

More: William Tyndale, who produced the first English-language Bible translated from the original Greek and Hebrew texts, was martyred for his holy work. See here for an article on his life.

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

The prophet Micah of Moresheth was a contemporary of Isaiah who denounced Judah for two primary sins. To find out more and to learn about the man Micah, see his profile at Micah 1:1.

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

Nebuchadnezzar: Servant of God?

No matter who we may consider as the most dangerous, treacherous, criminal world leader in recent history, we probably cannot regard that person with greater suspicion, horror, and disdain than the people of Judah had for Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon. Yet God described this barbarous king as His “servant” (Jer. 25:9). That label must have been shocking for the people who heard Jeremiah preach. Nebuchadnezzar represented enormous evil. He ruled a ruthless superpower poised to overrun their lands and destroy their communities. How could he possibly be God’s servant?

Intriguingly, the Lord’s description of Nebuchadnezzar sounds like His designation for the Persian king Cyrus: “My shepherd” and “His anointed” (Is. 44:28—45:1). Both rulers had power over vast territories of the ancient Middle East. Their decisions determined innumerable historical events. From a human perspective, they were in charge.

But prophecies from Isaiah and Jeremiah reveal that these rulers actually had no control at all. Whether they knew it or not, they were finite human beings given authority by God. They were God’s agents, and their decisions ended up serving God’s purposes. Their knowledge and acquiescence were unnecessary and irrelevant.

Yet even as these two men unwittingly fulfilled God’s will, the Lord sought them out. He wanted them to know and worship Him. For example, God used Daniel to steer Nebuchadnezzar toward Him (see “Heaven Rules” at Dan. 4:26, 27 and “God at Work for His People” at Dan. 4:27). It is possible that we will meet Nebuchadnezzar in heaven. Likewise, the Lord may have confronted Cyrus (Ezra 1:1). An encounter may have prompted the king to worship God by issuing the decree allowing Jews to return to Judah and rebuild the temple (1:2–4).

God is the King of all kings—then and now. Perhaps the leaders we most dislike are in fact servants of the living God. Like Nebuchadnezzar and Cyrus, God seeks not merely to use them but to save them. And it is our duty to pray for them and work toward that goal (1 Tim. 2:1, 2), for “all things are possible to him who believes” (Mark 9:23).

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

When Jeremiah told King Zedekiah of Judah to submit his country to Babylon’s authority, the prophet was likely still wearing a wooden yoke as well as bonds or shackles on his hands (Jer. 27:2). A yoke was used to team oxen or other animals for plowing. This was one of several parables that Jeremiah acted out to communicate the Lord’s message to His people. To discover others, see “The Parables of Jeremiah” at Jeremiah 18:1–10.

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

Ethicists debate whether some circumstances justify deception, but Scripture seems to indicate that honesty is always the best policy. Furthermore, deceit often turns on its source, who pays an even higher price in the long run than if he or she had told the truth in the first place.

Hananiah the prophet misled Judah by denouncing Jeremiah’s unpleasant message and speaking his own prophecy, announced with the words, “Thus says the LORD.” But the Lord had not spoken to him (Jer. 28:10, 11). False prophecy was a serious sin punishable by death (Deut. 13:1–5), and it was no surprise when the Lord made Hananiah pay for his deception with his life (Jer. 28:15–17).

The Bible offers multiple examples demonstrating that the Lord hates dishonesty (Prov. 6:16, 17) and that “he who speaks lies shall perish” (19:9):

• A lie brought sin and death into the world (Gen. 3:1–7; 1 Tim. 2:14).

• Cain tried to lie his way out of answering for the murder of his brother Abel, then spent a lifetime in fear of meeting a similar fate (Gen. 4:1–16).

• Rebekah and Jacob told Isaac a lie in order to steal the family blessing from Esau. The result was family estrangement and hostility, which endured for generations (27:5–17, 41–46; see also “A Tale of Two Brothers” at Obad. 10).

• Joseph’s brothers lied to their father Jacob about selling Joseph to slave traders, causing Jacob profound heartache (Gen. 37:28–35).

• Potiphar’s wife lied in order to frame Joseph for attempted rape, resulting in an unjust prison sentence (39:7–20).

• David caused Uriah’s murder in order to cover up his affair with Bathsheba. His deceit caused his child to die and his family to suffer profound conflict (2 Sam. 11–12).

• Peter denied knowing the Lord, bringing shame and sorrow on himself (Matt. 26:69–74).

• Ananias and Sapphira lied to the church and the Holy Spirit about a financial gift, inviting their untimely death (Acts 5:1–11).

Jesus spoke clearly about the nature of lying when he declared that lies are of the devil (John 8:44). By contrast, Jesus is the source of all truth, and those who speak and practice the truth demonstrate that they belong to Him (14:6; 1 John 3:19).

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

As Christians we live with hope in the return of Christ and eternity with Him. In the meantime, we are visitors on earth (1 Pet. 2:11). As we wonder about our purpose in this less-than-perfect world, we can gain insight from the Lord’s instructions to the Judean captives living in Babylon.

The Babylonians struck Judah in 605 B.C. and again in 599–597 B.C. After each attack, they carried off the nation’s brightest leaders (2 Kin. 24:14–16; Jer. 27:20; 29:2; Dan. 1:1–6). These exiles were settled along the Chebar River (Ezek. 1:1), possibly near a canal of the Euphrates on the eastern side of Babylon.

Shortly after the second deportation, the false prophet Hananiah announced to Zedekiah and the people left in Jerusalem that the captives would come home within two years (Jer. 28:1–4). Prophets in Babylon apparently were saying the same thing (29:8, 9). Jeremiah denounced this claim (28:15, 16), and within two months, Hananiah died (28:17).

Jeremiah wrote to tell the exiles that they should expect seventy years of Babylonian captivity (29:1, 10). His message opened with startling news: God Himself had caused the exiles to be carried away to Babylon (29:4). Their plight was not just the result of Nebuchadnezzar’s policies but of God’s purposes. The captives were sent to fulfill a mission.

Part of that mission was to live out the seventy years of exile in submission to God’s judgment. So Jeremiah told the refugees to build houses, plant gardens, marry, and have children (29:5, 6). The captives were not going anywhere for at least a couple of generations, so they might as well make the best of their lot. After all, the Lord also intended for His people to survive the captivity so that He could bring a remnant back to the Promised Land.

But another part of the exiles’ mission was to “seek the peace of the city” of Babylon (29:7). This must have been unthinkable—to pray and work for the good of enemies who had dragged them from their homeland and would soon demolish their capital and its temple! Yet Jeremiah affirmed that the exiles’ well-being was tied to that of the Babylonians (29:7).

This hints at how we should interpret the circumstances in which God places us today. Like the exiles of Judah, we may live in communities and countries that do not uphold God’s values—they may even actively promote evil. Nevertheless, we should seek the peace of these places where we go about our lives.

The “peace” (Hebrew: shalom) that God wants us to pursue is a just peace—not peace without justice, or justice without peace, but justice and peace together, in harmony. This responsible compassion happens through prayer and hard work, and it demonstrates that God is with us (James 3:17, 18).

More: Discover some practical ways to seek peace for your community by consulting the articles under “Urban Life” in the Themes to Study index.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

Countless readers of the Bible have found comfort in the words of Jeremiah 29:11, “For I know the thoughts that I think toward you, says the LORD, thoughts of peace and not of evil, to give you a future and a hope.”

These words were originally given to the captives in Babylon, who must have felt that their glory days were over, that never again would they enjoy the peace and prosperity that came with having a special covenant relationship with the Creator. Yet even in their darkest hour, God soothed their broken hearts with the promise that their hardships were not permanent. They would eventually return to their homeland, and He Himself would never be far; any who sought Him would find Him (29:10, 12–14).

This is also true for us today. As Christ said, “Ask, and it will be given to you; seek, and you will find; knock, and it will be opened to you” (Matt. 7:7; Luke 11:9). The fulfillment of these promises can sometimes surprise us, but when we seek the Lord with a pure heart, we will never be disappointed. God has nothing but good thoughts toward us, and good plans to achieve good things. The full measure of this will be seen at the end of time as we joyfully receive the ultimate gift of this promise, embarking on the greatest future and hope we could ever imagine in the kingdom of heaven.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

A Liberating Love

In 1960 an African was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for the first time in history. The winner was Albert Lutuli (1898–1967), a political activist who organized the masses to rise up against the discrimination imposed by the white minority in South Africa. This official system of segregation, called apartheid (“the state of being apart”), stripped black citizens of their rights and dignity as human beings equally loved and honored by God. As Lutuli declared, “If I find a man in the mud, it is my duty to uplift him and remind him ‘You are not of the mud.’ If there be human beings who … have forgotten their rights and wallow in the mud, it is the duty of all who see, to say to them ‘Don’t wallow in mud.’ ”

After his father’s death, Lutuli was raised by his mother in her family home in Groutville, South Africa. His mother fought for him to obtain an education, and he progressed through Congregationalist and Methodist schools to obtain a teaching degree. A scholarship allowed Lutuli to gain more training, and he taught primary school for fifteen years after declining another scholarship to a university, choosing instead to join the workforce in order to provide financial support for his mother.

Lutuli advocated for a free liberal education for all black Africans that would be equal to the schooling white children received, and he became president of the African Teacher’s Association in 1933. He was also an active lay preacher who advanced through several leadership positions in the Methodist Church.

In 1936, Lutuli accepted a call from tribal elders to become chief of his tribe. But as South Africa’s government imposed more and more restrictions on black Africans—for example, revoking voting rights from the few who had been allowed to vote—Lutuli’s concern expanded to his entire nation. Lutuli joined the African National Congress (ANC) in 1942 and began to organize nonviolent opposition to the oppressive laws of the ruling Nationalist Party.

The Nationalist Party had gained control of the government in 1948 and had been responsible for the establishment and implementation of apartheid. Under this corrupt policy, laws codified in the 1950s restricted black citizens’ movements and prohibited them from owning land, marrying outside their race, receiving an education that qualified them to attend college, or pursuing virtually any occupation other than manual labor.

Upon his election as president of the ANC in 1951, the government removed Lutuli from his chieftainship. He was banned from attending any political or public gatherings and was prohibited from entering any major South African city. Lutuli was arrested for high treason in 1956 and jailed for a year, and subsequently confined to a fifteen-mile radius of his home. When he publicly burned his pass (pass books were required to be carried by all black citizens when traveling outside designated areas) in 1960 in support of sixty-nine demonstrators who had been massacred in the South African township of Sharpeville, the ANC was outlawed and Lutuli sentenced to prison.

Released due to his poor health, Lutuli was allowed to leave the vicinity of his home only to accept the Nobel Peace Prize. His personal convictions compelled him to advocate peaceful revolt even as other political leaders launched an armed wing of the ANC.

Lutuli published an autobiography in 1962 titled Let My People Go, in which he describes his motivation to combat the evils of segregation. He writes, “My own urge because I am a Christian, is to get into the thick of the struggle … taking my Christianity with me and praying that it may be used to influence for good the character of the resistance.” Lutuli died in 1967 when he was struck by a train as he walked along a bridge near his home.

Go to the Life Studies Index.

![]()

Few heartaches run deeper than the pain of a parent whose child grows up to be an obstinate rebel. A parent experiencing that inconsolable sorrow may react with hostility and rejection, as if the wayward child no longer deserves love—or with self-recrimination, as if the parent deserves all the blame for how a child turns out.

Scripture offers a model for the parent of a difficult child—God Himself. His dear son Ephraim—the northern kingdom of Israel—had completely abandoned His commands in favor of pagan religion (2 Kin. 17:7–18). As a result, the Lord allowed Assyria to take the Israelites into exile in 722 B.C. But God never forgot His people, nor did He stop loving them. Like the merciful father in Jesus’ parable of the prodigal son (Luke 15:22–32), the Lord never wavered in His affection for Israel. He stood ready to welcome His people back whenever they wished to halt their rebellion. And Jesus Himself was the supreme evidence of God’s loyalty to His faithless children: “He came to His own, and His own did not receive Him” (John 1:11). Yet he came nonetheless.

When we find ourselves in the position of a parent of a prodigal child, we can remember that the one-and-only perfect Parent raised wayward children. Because we are sinful human beings, we may struggle to love our children with the love that God has for us. But as we wonder how to best deal with our children, we can ask God to empower us with love, wisdom, and grace.

More: For more insights into raising children and caring for family, see the articles under “Family” in the Themes to Study index. Many influential Christians began as prodigal children, kicking and screaming all the way to God. See articles on the lives of some of these believers here (C. H. Spurgeon), here (C. S. Lewis), and here (Bakht Singh Chabra).

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

Knowing God begins with entering into and enjoying a personal relationship with Him because of what He accomplished on the cross. Yet centuries before Jesus arrived, Scripture outlined what personal intimacy with God would be like. The Lord gave Jeremiah a vision of a “new covenant” that Jesus would initiate. The prophet foresaw that …

• God’s children would know Him firsthand, not just know about Him (Jer. 31:34).

• God would teach His people (31:34) just as He taught Jesus (John 5:19; 8:28; 12:49; 14:10).

• God’s teaching would go beyond moral precepts or an external code of ethics to inscribing His Word (or His law) on His children’s hearts to shape their identity and behavior (Jer. 31:33).

The New Testament discloses that the words that God writes on human hearts are inscribed by the Holy Spirit (2 Cor. 3:1–3), who empowers God’s followers to live in a way that reflects His character. This profound truth of a new covenant is so significant that Jeremiah 31 is quoted three times in the New Testament (John 6:45; Heb. 8:10; 10:16, 17).

We are designed to experience this close connection with the Lord. It begins by calling out to God, confessing our sinfulness and thanking Him for the forgiveness He extends to us as a result of Jesus’ death and resurrection.

More: Having a relationship with God goes hand in hand with living a godly lifestyle. See “Knowing God” at Jer. 22:15, 16 and read James 2:14–26. A. Wetherell Johnson, founder of Bible Study Fellowship, spent her life helping others to understand and apply the Word of God to their lives, helping to introduce them to Jesus and grow as vessels of the Holy Spirit. See here for an article on the life of A. Wetherell Johnson.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

The purchase of a cousin’s field was a legal transaction to which Jeremiah was both entitled and obligated (see “The Redeeming Relative” at Lev. 25:25). But he turned the occasion into a potent lesson by instructing Baruch to take special care to preserve the deed of purchase.

When land changed hands in ancient Israel, two deeds of purchase were drawn up (Jer. 32:11). One was an open copy used for easy reference. The other was an archival copy placed in an earthen jar sealed with pitch, which was an airtight container that could preserve a document indefinitely. Archaeologists have discovered documents preserved in this way that are thousands of years old yet retain their original condition.

Jeremiah instructed Baruch to place both the sealed and open copies in a second, larger earthen vessel. Then he publicly declared that God would preserve a remnant through the coming exile, which would return to Judah and buy and sell property.

Jeremiah’s words testified to his faith and foretold the future. His special care of the deeds was also a prudent thing to do. Exiles who eventually returned needed proof of ownership to determine which lands belonged to which families. Perhaps some of the 128 men of Anathoth who returned with Zerubbabel (Ezra 2:23) used the deed so carefully preserved by their predecessor Jeremiah.

More: Jeremiah’s creative use of everyday activities and objects to communicate God’s truth was a hallmark of his ministry. See “The Parables of Jeremiah” at Jer. 18:1–10.

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

Jerusalem: From Desolation to Joy

The holy city of Jerusalem was destroyed by the Babylonians in 587 B.C., but Jeremiah envisioned the city’s restoration and a return to prosperity and joy (Jer. 32:42–44). His prophecy was partially fulfilled when Ezra and Nehemiah led exiles back to rebuild the temple and the city walls. But Jerusalem’s joy would fully and finally come about through the new covenant (31:31), initiated at Christ’s coming (Heb. 8:6–13). God withdrew from Jerusalem for a time as a consequence of His people’s violation of their original covenant with Him (Jer. 32:28–42). But under the new covenant, His people would know Him up close, turning the city of desolation into a city of joy.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

When King Zedekiah tried to halt a form of slavery in Jerusalem, he discovered the difficulties of stopping institutionalized sin.

Old Testament law allowed people who could not satisfy debts to become slaves of their creditors. But the length of servitude could not exceed a maximum of six years. In the seventh year, or Sabbath year, slaves were to be released. Not only were debts to be forgiven, but former owners were to send off freed slaves with material provisions (Deut. 15:12–18).

As Judah’s economy faltered, the wealthy devised ways to keep their neighbors in permanent bondage (compare Is. 3:14, 15). Faced with the Lord’s imminent judgment, Zedekiah arranged for the people to renew the covenant and release their slaves. But once the slave-owners perceived that the threat of punishment had passed, they broke their commitments and returned their debtors to slavery. Renewing the covenant was no more than an empty gesture.

Institutionalized evil demands fundamental change from the top to the bottom of society. Because Judah never undertook that kind of reformation, the nation eventually fell under the Lord’s judgment (Jer. 34:17–22; 52:4–27).

More: God warned the Israelites to honor their commitments to Him and to others. See “Making Promises to God” at Num. 30:2.

Go to the Focus Index.

![]()

Baruch the scribe was a lifelong friend of Jeremiah and played a crucial role in the prophet’s work. The Book of Jeremiah may have been a product of Baruch’s efforts as well as Jeremiah’s.

The Bible indicates that Baruch recorded many of Jeremiah’s prophecies from dictation (Jer. 36:17, 18; 45:1). Some believe that he initially took down the words in shorthand and later fleshed out the text (36:32). Whatever his process, he was conscious of recording God’s words as given to Jeremiah (36:4, 6). Baruch also occasionally read the prophet’s words in public. Reading and preserving Scripture were part of Baruch’s official duties as a scribe (36:10, 20; compare 2 Kin. 22:8–10).

Baruch served Jeremiah at immense personal risk. When one of his scrolls was presented to King Jehoiakim, it was slashed and burned, and orders were issued to arrest its authors (Jer. 36:20–28). Baruch was later accused of biasing Jeremiah against Judeans who wanted God’s permission to flee to Egypt (43:3). Like the prophet, Baruch complained to the Lord about his sufferings, and he was comforted with assurances that his life would be protected (45:1–5).

More: Baruch was probably deeply familiar with government leaders and issues. His brother was a royal official under King Zedekiah. For more on Baruch, see his profile at Jer. 45:1. To discover more about the important work of scribes, see “Scribes” at Luke 20:39.

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

Name means: “The Lord Raises Up.”

Also known as: Eliakim (“God Is Setting Up”); Pharaoh Necho changed his name to Jehoiakim as a sign of subordination (2 Kin. 23:34).

Not to be confused with: Eliakim, an official in the time of King Hezekiah (18:18), or three other men named Eliakim mentioned in Scripture, including two who were ancestors of Jesus (Neh. 12:41; Matt. 1:13; Luke 3:30).

Home: Jerusalem.

Family: Son of Josiah and Zebudah; brother of Jehoahaz and Zedekiah; father of Jehoiachin, his successor.

Occupation: King of Judah (609–598 B.C.) but a vassal of the Egyptian pharaoh Necho early in his reign and later of the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar.

Best known as: The godless king who burned Jeremiah’s scroll (Jer. 36:9–24). He ruled by greed, dishonesty, oppression, and injustice (22:13–19). He murdered the prophet Urijah and attempted to kill Jeremiah and Baruch, who escaped death only through the protection of friends in high places (26:20–24; 36:19, 26).

More: To learn more about Jehoiakim’s place in Judah’s history and his influence on Jeremiah’s life and prophecy, see “The Life and Times of Jeremiah” at Jer. 1:3.

Go to the Person Profiles Index.

![]()

Godly Fathers with Troubled Sons

Although Scripture urges parents to raise their children “in the training and admonition of the Lord” (Eph. 6:4), it never guarantees how children will turn out. Each individual must decide whether to follow the Lord or ignore His commands. Even though parents point their children in the right direction, emerging adults determine which way they will go.

That fact explains why godly parents can have spiritually rebellious children—and why people of enormous faith and compassion can come from homes where God was dishonored or unknown.

Josiah was a faithful man and conscientious ruler (see his profile at 2 Chr. 34:1). But all three of his sons disobeyed God and paid a tragic price. Note these other fathers in Scripture who honored the Lord but whose sons largely deserted His ways:

Father | Son(s) |

Isaac: pleaded with God to give his wife Rebekah a child (Gen. 25:21). | Jacob: used deception to deprive his brother of his father’s blessing, which set off generations of conflict (Gen. 27:6–29, 41–46); he later began to fear the Lord (32:24–32). |

Aaron: helped lead the people of Israel during the Exodus and was consecrated as the nation’s first high priest (Ex. 28:1). | Nadab and Abihu: dishonored God in their official duties by offering “profane fire” before the Lord (Lev. 10:1–3). |

Gideon: obeyed God’s call to lead the Israelites in a successful rout of the Midianites (Judg. 6:11–14; 7:19–22). | Abimelech: hired assassins to murder his 70 brothers and led a treacherous assault on Shechem (Judg. 9). |

Manoah: worshiped the Lord during a period of great spiritual darkness (Judg. 13). | Samson: dishonored his parents’ Nazirite vow, visited prostitutes, and gave little indication of fearing the Lord until the end of his life (Judg. 14–16). |

Samuel: judged Israel with integrity and anointed its first two kings (1 Sam. 3:19–21; 9:27—10:1; 16:11–13). | Joel and Abijah: accepted bribes and violated justice in their positions as judges in Beersheba (1 Sam. 8:1–5). |

David: appointed as God’s choice for Israel’s king and described as a “man after God’s own heart” (1 Sam. 13:14). | • Amnon: raped his half sister Tamar, provoking his half brother Absalom to murder him (2 Sam. 13:1–18). • Absalom: had Amnon assassinated and later led a rebellion against his father David, hoping to seize the throne for himself (13:21–33; 15:1—18:33). • Adonijah: schemed to wrest the right of succession away from his brother Solomon (1 Kin. 1). • Solomon: feared the Lord in his youth but later turned away from Him, influenced by the idolatry of his many wives (11:1–8). |

Solomon: was granted unprecedented wisdom by God (1 Kin. 3:5–15) and built and dedicated the temple (5:1—6:38; 8:1–64). | Rehoboam: rejected his father’s wise counselors in favor of his own companions, whose advice triggered a permanent split in the kingdom (1 Kin. 12:1–19). |

Hezekiah: enacted numerous reforms and remained faithful to the Lord during an Assyrian siege of Jerusalem (2 Kin. 18–20). | Manasseh: thoroughly reversed his father’s reforms, reinstituted idolatry, and ruled by violence (2 Kin. 21). |

Josiah: cleaned out the temple, renewed the covenant, and restored proper worship of the Lord (2 Kin. 22:1—23:30). | • Jehoahaz: rejected his father’s example during a brief reign marked by evil (2 Kin. 23:31–33). • Jehoiakim: returned to idolatry, overtaxed the people, had the prophet Urijah executed, and actively opposed Jeremiah (23:35–37; Jer. 26:20, 21; 36:26). • Zedekiah: continued the pattern of evil initiated by his brothers (2 Kin. 24:18–20), serving as a weak, vacillating ruler. |

More: Even the “best” families include “black sheep.” See “Advice Without Assurance” at Lev. 10:1–3. The Law provided strong measures against chronically rebellious youths. See “Juvenile Delinquents” at Deut. 21:18–21.

Go to the Insight Index.

![]()

Blowing the Whistle with Wisdom

God instructed Jeremiah to point out Judah’s flagrant sins and warn of impending judgment. But as the prophet delivered this unpopular message, crowds attacked the messenger. He was arrested and jailed on a fabricated charge of defecting to the enemy (see “The Persecuted Prophets” at Jer. 15:15–18).

Like Jeremiah, we are at times called to expose evil. We might wish we could block out our concerns about unjust, oppressive, or dangerous situations. Or we might want to confront an issue but not know how. The complexity of each situation demands its own finely crafted response, but one point is universally true: Scripture never encourages us to close our eyes to wrongdoing. We are to “abhor what is evil” and “cling to what is good” (Rom. 12:9). We are not to be “overcome by evil, but overcome evil with good” (12:21).

This does not mean we should ignore the potential hazards of speaking out against wrongs. Nor should we always remain silent if the cons seem to outweigh the pros. But we should consider the costs of speaking up, and Jeremiah’s life offers ten guidelines for exposing evil with courage and wisdom:

1. Be sure that your charges are true and can be substantiated. Jeremiah stood in the temple and accused worshipers of committing several specific sins (see “What Is Religion?” at Jer. 7:2–4). Anyone could easily verify whether Jeremiah’s charges were true.

2. Consider whether God has called you to the task. Jeremiah knew with certainty that God had called him to be a prophet (1:4–10). Before you open your mouth, pray long and hard about how God might want you to proceed.

3. Be prepared to depend on God. When Jeremiah faced persecution, he turned to God rather than turning on his enemies (11:18–20). God may not take suffering away, but He will give you strength to stand (38:5, 6, 28).

4. Document your position with written evidence. Jeremiah had his scribe Baruch record his prophecies for future reference (see “Baruch Behind the Scenes” at Jer. 36:4–8). In the long run, these records vindicated the prophet (Jer. 36; compare Ezra 1:1; Dan. 9:2).

5. Don’t expect quick acceptance of your message. The people who heard Jeremiah seemed firmly committed to rejecting whatever he said (Jer. 5:21–31; 43:1–7).