{ EIGHT }

Ternary Societies and Colonialism: The Case of India

We turn now to the case of India, which is particularly important for our study. This is not just because the Republic of India has been the “largest democracy in the world” since the middle of the twentieth century and will soon become the most populous nation on the planet. If India plays a central role in the history of inequality regimes, it is also because of its caste system, which is generally regarded as a particularly rigid and extreme type of inequality regime. It is therefore essential that we understand its origins and peculiarities.

Apart from its historical importance, the caste system has left traces in contemporary Indian society much more prominent than the status inequalities stemming from the European society of orders (which have almost entirely disappeared except for largely symbolic vestiges such as hereditary peerages in the United Kingdom). Our task is therefore to understand whether these distinct evolutionary trajectories can be explained by longstanding structural differences between European orders and Indian castes or if they are better understood in terms of specific social and political trajectories and distinct switch points.

We will find that the trajectory of Indian inequality can be correctly analyzed only within a more general framework involving the transformation of premodern trifunctional societies. What distinguishes the Indian trajectory from the various European ones is the fact that state construction in the vast subcontinent followed an unusual path. Specifically, the process of social transformation, state construction, and homogenization of statuses and rights (which were particularly disparate in India) was interrupted by a foreign power, the British colonizer, which in the late nineteenth century sought to map the caste hierarchy to assert control over society. Its primary tool for doing this was the census, which was conducted every ten years from 1871 to 1941. An unanticipated consequence of the census was that it gave the caste hierarchy an administrative existence, which made the system more rigid and resistant to change.

Since 1947, independent India has tried to use the state’s legal powers to correct the legacy of caste discrimination, especially in access to education, government jobs, and elective office. The government’s policies, though far from perfect, are highly instructive, all the more so since discrimination exists everywhere, not least in Europe, which has just begun to deal with ethnic and religious hostilities of the sort with which India has had to contend for centuries. The course of Indian inequality was profoundly altered by its encounter with the outside world in the form of a remote foreign power. Now, in turn, the rest of the world has much to learn from India’s experience.

The Invention of India: Preliminary Remarks

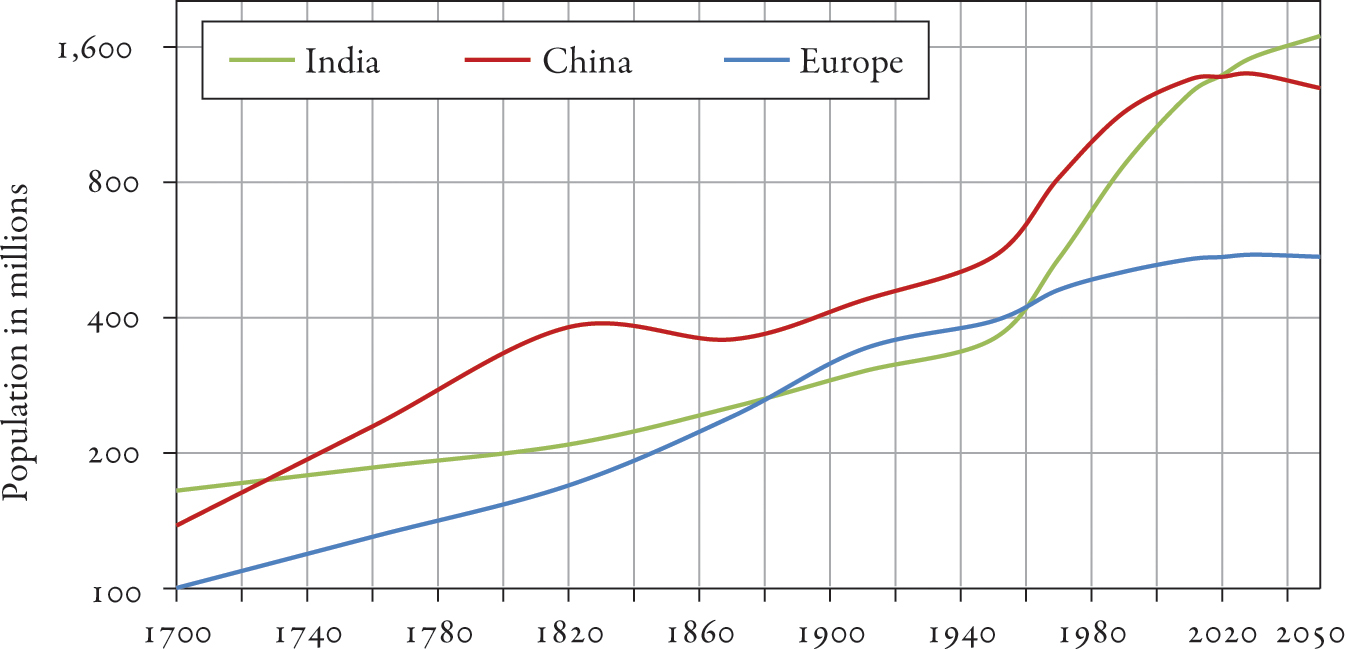

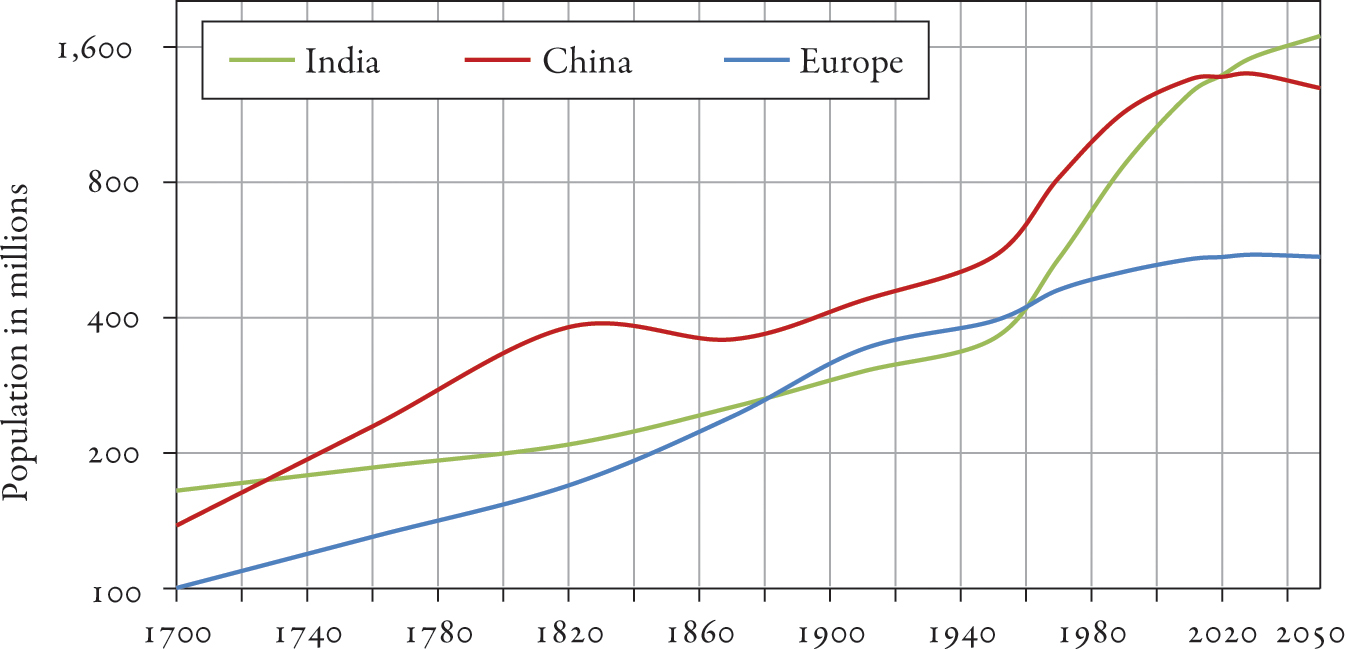

As far back as we can go in the demographic sources, we find that the territory now occupied by the Republic of India and the People’s Republic of China has always been home to more people than Europe and other parts of the world. In 1700, the population of India was about 170 million and that of China about 140 million, compared with 100 million in Europe. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries China leapt ahead of India. Since China’s adoption of a single child per family policy in 1980, however, its population has been shrinking, and by the end of the 2020s India should once again be the most populous country-continent on the planet. It will remain so for the rest of the twenty-first century, with nearly 1.7 billion citizens by 2050 if one believes the latest projections from the United Nations (Fig. 8.1). To explain the exceptional population densities in China and India, many authors have followed the lead of Fernand Braudel, who insisted in Civilisation matérielle, économie et capitalisme on the importance of different dietary regimes: the reason for Europe’s lower population density, Braudel argues, is that Europeans are too fond of meat, since it takes more acres to produce animal calories than to produce vegetable calories.

Our focus is on inequality, however. We have already seen the crucial importance of centralized state building in the evolution of structures of inequality. The first question to ask now is how did a population as large as India’s (already 200 million by the end of the eighteenth century, when the population of the largest European country, France, was less than 30 million and already in the throes of revolution) manage to coexist peacefully in a single large state. The first answer is that Indian unity is actually a very recent development. India as a human and political community developed only gradually, following a complex social and political trajectory. Many state structures coexisted in India for centuries. Some of them extended over vast portions of the Indian subcontinent: for instance, the Maurya Empire in the third century BCE and the Mughal Empire, which even at its peak in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries never covered all of present-day India and thereafter went into decline.

FIG. 8.1. Population of India, China, and Europe, 1700–2050

Interpretation: Around 1700, the population of India was about 170 million, of China 140 million, and of Europe 100 million (roughly 125 million if one includes the area corresponding to today’s Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine). In 2050, according to UN forecasts, the population of India will be about 1.7 billion, of China 1.3 billion, and of Europe (EU) 550 million (720 million if one includes Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine). Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

When the British Raj (as Britain’s colonial empire in India was known) gave way to independent India in 1947, the country still comprised 562 princely states and other political entities under the tutelage of the colonizing power. To be sure, the British directly administered more than 75 percent of the country’s population, and the censuses conducted from 1871 to 1941 covered the entire country (including the princely states and autonomous regions). The British administration nevertheless relied heavily on local elites and often did little more than maintain order. Infrastructure and public services were as rudimentary or nonexistent as in the French colonies.1 It was left to independent India to achieve administrative and political unification after 1947 under a vibrant, pluralist parliamentary democracy. India’s political practice was of course influenced by its direct contact with Britain and its parliamentary model. It is important to recognize, however, that India developed this form of government on a larger human and geographic scale than anything that preceded it in history. Europe is currently attempting to build a political organization on a large scale with the European Union and European Parliament (although Europe’s population is less than half of India’s and its political and fiscal integration is much less advanced). Meanwhile, the United Kingdom, which parted company with Ireland in the early twentieth century and may lose Scotland in the twenty-first, has had a hard time maintaining unity on the British Isles.

In the eighteenth century, when the British were preparing to push further inland, India was divided into a multitude of states led by Hindu and Muslim princes. Islam began to make inroads into northwest India as early as the eighth to tenth centuries, which led to the founding of the first kingdoms and then the seizure of Delhi by Turco-Afghan dynasties in the late twelfth century. The Delhi Sultanate then expanded and transformed itself in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, after which new waves of Turco-Mongol immigration led to the founding of the Mughal Empire, which dominated the Indian subcontinent from 1526 to 1707. The Mughal state, led from Agra and later Delhi by Muslim sovereigns, was multiconfessional and polyglot. In addition to the Indian languages spoken by the vast majority of the population and the Hindu elites, the Mughal court spoke Persian, Urdu, and Arabic. The Mughal state was a complex and shaky structure, clearly running out of energy by 1707 and permanently contested by Hindu kingdoms such as the Maratha Empire, initially located in present-day Maharashtra (centered on Mumbai) before extending its reach into northern and western India between 1674 and 1818. It was in this context of rivalry among Muslim, Hindu, and multiconfessional states and gradual decay of the Mughal Empire that the British slowly took control, first under the auspices of the shareholders of the East India Company from 1757 to 1858 and then under the authority of the Empire of India from 1858 to 1947. The Empire was directly linked to the British Crown and Parliament after the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857 showed London the need for direct administration. In 1858 the British seized the opportunity to depose the last Mughal emperor, whose empire had shrunk to a small territory in the neighborhood of Delhi but who still symbolized moral authority and a semblance of native sovereignty in the eyes of Hindu and Muslim rebels who had sought his protection for their efforts to mount a rebellion against the European colonizer.

Broadly speaking, the very long shared history of Hindus and Muslims in India, from the Delhi Sultanate of the late twelfth century to the ultimate fall of the Mughal Empire in the nineteenth, gave rise to a unique cultural and political syncretism in the Indian subcontinent. A significant minority of India’s military, intellectual, and commercial elites gradually converted to Islam and forged alliances with the conquering Turco-Afghans and Turco-Mongols, whose numbers were quite small. As the Muslim sultanates extended their dominion into the center and south of India in the sixteenth century at the expense of the Hindu kingdoms, especially the Vijayanagara Empire (in today’s Karnataka), they forged close ties with Hindu elites and literary circles associated with the various courts, including Brahmin scholars working for Muslim sultans and Persian chroniclers who frequented the palaces. Their ties to the European colonizers were even closer, especially with the Portuguese who established colonies (most notably in Goa and Calicut) on the Indian coast after 1510 and who sought to overwhelm the Muslim kings and take up the cause of the Vijayanagara Empire while refusing the emperor’s offer of matrimony.2 Hostility between Hindus and Muslims also existed, especially since many who converted to Islam came from the lower strata of Hindu society and saw conversion as a way to flee a particularly hierarchical and inegalitarian caste system. Muslims are still overrepresented in the poorest segments of Indian society; in Part Four of this book we will see that the attitude of Hindu nationalists toward poor Muslims has been a key structural feature of Indian politics from the late twentieth century to the present, in some respects comparable to recent conflicts in Europe (with the important difference that there have been Muslims in India for centuries, whereas in Europe their presence dates back only a few decades).3

At this stage, note simply that thanks to the imperial censuses conducted every ten years from 1871 to 1941 and continued after independence from 1951 to 2011, we can measure the evolution of the country’s religious diversity (Fig. 8.2). We find that Muslims accounted for roughly 20 percent of the 250 million people enumerated in the first two censuses, in 1871 and 1881, and that this proportion rose to 24 percent in 1931 and 1941 thanks to a higher birth rate among Muslims. In 1951, in the first census organized by the independent Republic of India, the proportion of Muslims fell to 10 percent owing to the partition of the country: Pakistan and Bangladesh, where most Muslims lived, ceased to be part of India and were therefore no longer included in the census, in addition to which there were large-scale movements of Hindus and Muslims after partition. Since then, the proportion of Muslims has risen slightly (again owing to a slightly higher birth rate), reaching 14 percent in the 2011 census out of a population of more than 1.2 billion.

FIG. 8.2. The religious structure of India, 1871–2011

Interpretation: In the 2011 census, 80 percent of the population of India was declared Hindu, 14 percent Muslim, and 6 percent other religions (Sikhs, Christians, Buddhists, no religion, etc.). These figures were 75 percent, 20 percent, and 5 percent in the colonial census of 1871; 72, 24, and 4 percent in the census of 1941; 84, 10, and 6 percent in the first census of independent India in 1951 (after the partition with Pakistan and Bangladesh). Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

Religions other than Hinduism and Islam have accounted for around 5 percent of the population in every census from 1871 to 2011. Among them we find mainly Sikhs, Christians, and Buddhists (in roughly comparable numbers), as well as individuals professing no religion at all (of whom there are very few—always less than 1 percent). Bear in mind, however, that colonial censuses and to a lesser extent those conducted after independence as well are based on a complex mix of self-declared identities and identities assigned by census agents and administrators. If a person did not clearly belong to a listed religion (Muslim, Sikh, Christian, or Buddhist), the default classification was generally “Hindu” (since Hindus accounted for 72–75 percent of the population in the colonial era and 80–84 percent in the era of independence), even when the person belonged to a pariah group subject to discrimination by Hindus, including lower castes, former untouchables, and aborigines.

|

TABLE 8.1 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The structure of the population in Indian censuses, 1871–2011 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

1871 |

1881 |

1891 |

1901 |

1911 |

1921 |

1931 |

1941 |

1951 |

1961 |

1971 |

1981 |

1991 |

2001 |

2011 |

||||||||||||||||

|

Hindus |

75% |

76% |

76% |

74% |

73% |

72% |

71% |

72% |

84% |

83% |

83% |

82% |

81% |

81% |

80% |

|||||||||||||||

|

Muslims |

20% |

20% |

20% |

21% |

21% |

22% |

22% |

24% |

10% |

11% |

11% |

12% |

13% |

13% |

14% |

|||||||||||||||

|

Other religions (Sikhs, Christians, Buddhists, etc.) |

5% |

4% |

4% |

5% |

6% |

6% |

7% |

4% |

6% |

6% |

6% |

6% |

6% |

6% |

6% |

|||||||||||||||

|

Total |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

|||||||||||||||

|

Scheduled castes (SC) |

15% |

15% |

15% |

16% |

17% |

16% |

17% |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Scheduled tribes (ST) |

6% |

7% |

7% |

8% |

8% |

8% |

9% |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Total Indian population (millions) |

239 |

254 |

287 |

294 |

314 |

316 |

351 |

387 |

361 |

439 |

548 |

683 |

846 |

1,029 |

1,211 |

|||||||||||||||

|

Interpretation: The results indicated here are based on censuses conducted in the Empire of India from 1871 to 1941 and then in independent India from 1951 to 2011. The proportion of Muslims fell from 24 percent in 1941 to 10 percent in 1951 owing to the partition of Pakistan and Bangladesh. From 1951 on, the censuses recorded “scheduled castes” (SC) and “scheduled tribes” (ST)—untouchables and disadvantaged aborigines. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The overwhelming “Hindu” majority is therefore partly artificial and masks immense disparities of status, identity, and religious practice within Hindu polytheism, especially since different groups do not enjoy the same level of access to ceremonies and temples. Islam, Christianity, and Buddhism purport to be egalitarian religions (in which everyone has access to God or wisdom in the same way, independent of origin or social class), at least in theory, since in practice those religions have also developed trifunctional and patriarchal ideologies that structure the social and political order and justify social inequalities and sexual division of labor and functions. Hinduism is more explicit in linking religion to social organization and class inequality. I will say more later about the way in which Hindu castes were defined and measured in colonial censuses as well as the way in which independent India has developed new categories, “scheduled castes” (SC) and “scheduled tribes” (ST), which account for roughly 25 percent of the population in the most recent censuses (Table 8.1). The purpose was of course to correct old discrimination but with the risk that these new categories could become permanent. Before taking up that question, we need to gain a better understanding of the origins of the caste system.

India and the Quaternary Order: Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas, Shudras

In our study of European societies of orders, we learned that the earliest texts giving formal expression to the trifunctional organization of society, with a religious class (oratores), a warrior class (bellatores), and a laboring class (laboratories), were penned by bishops in England and France in the tenth and eleventh centuries.4 The origins of the trifunctional idea in India date from much earlier. The functional classes in the Hindu system are called varnas, and the varnas appear as the four parts of the god Purusha in Sanskrit religious texts of the Vedic era, the oldest of which date from the second millennium BCE. But the fundamental text is the Manusmriti, or Code of Laws of Manu, a compendium of laws written in Sanskrit between the second century BCE and the second century CE and constantly revised and commented on ever since. This was a normative political and ideological text. Its authors described the way they thought society should be organized and specifically the way they thought the dominated and laborious classes should obey rules set by religious and warrior elites. It is in no sense a factual or historical description of Indian society at the time of its writing or at any time thereafter. That society encompassed thousands of social micro-classes and professional guilds, and the political and social order were constantly being challenged by revolts of the dominated classes and by the regular appearance of new warrior classes, which emerged from the ranks bearing new promises of harmony, justice, and stability—sometimes with effect, sometimes not, just as in Christian Europe and other parts of the world.

The heart of the Manusmriti is a description of the rights and duties of the several varnas, or social classes, whose role is defined in the first chapters. Brahmins functioned as priests, scholars, and men of letters; Kshatriyas were warriors responsible for maintaining order and providing security for the community; Vaishyas were farmers, herders, craftsmen, and merchants; and Shudras were the lowest level of workers, whose only mission was to serve the three other classes.5 In other words, this was an explicitly quaternary rather than ternary system, in contrast to the theoretical trifunctional order of medieval Christendom. In practice, however, the Christian system included serfs until a relatively late date, at least the fourteenth century in Western Europe and almost to the end of the nineteenth in the East, so that the laboring class really included two subgroups (free workers and servile workers), as in India. Note, moreover, that the scheme set forth in the Manusmriti was theoretical; in practice, the line between Vaishyas and Shudras, workers of different status and unequal duties, was often blurry. Depending on the context, it is reasonable to think that the distinction roughly corresponded to the difference between farmers who owned their own land and landless rural workers, or, in Europe, to the distinction between free peasants and serfs.

After defining the four major social classes, the Manusmriti goes into great detail about the rituals and rules that Brahmins must obey as well as the conditions governing the exercise of royal power. In principle, the king is a Kshatriya, but he is supposed to choose a group of counselors consisting of seven or eight Brahmins, preferably the wisest and most learned of their class. He is urged to consult with them daily about affairs of state and finances and is admonished not to make major military decisions without the approval of the most illustrious Brahmin.6 The Vaishyas and Shudras are more cursorily described. The Manusmriti also contains detailed descriptions of how the courts are supposed to function in a well-ordered Hindu kingdom, along with a large number of civil, criminal, fiscal, and successoral rules pertaining to such matters as the share of an estate due to children of “mixed” marriages between members of different varnas (which were discouraged but not forbidden). The text seems to be addressed primarily to a sovereign seeking to establish a kingdom in a new territory but also pertains to existing Hindu kingdoms. Distant barbarians are mentioned, especially Persians, Greeks, and Chinese, and it is stipulated that they should be considered and treated as Shudras, even if they were Kshatriyas by birth, because they do not obey the law of the Brahmins. In other words, a noble foreigner is the same as a Shudra as long as he has not been civilized by a Brahmin.7

Many scholars have tried to determine the context in which this text was written, circulated, and used. The Manusmriti is said to be the collective work of a group of Brahmins (the name Manu refers not to the actual author of the text but to a mythical legislator from centuries prior to the drafting of the code) who supposedly drafted and then polished this theoretical corpus in stages starting in the second century BCE. The goal was clearly to restore the power of the Brahmins, which in the eyes of the drafters was the basis of social and political harmony in Hindu society, in the particularly fraught political circumstances that followed the fall of the Maurya Empire (322–185 BCE). Brahmin power had been challenged in the third century BCE by the conversion to Buddhism of Emperor Asoka (268–232 BCE). The first Buddha, Siddhartha Gautama, who supposedly lived in the late sixth and early fifth centuries BCE, was according to tradition the scion of a family of Kshatriyas, and his ascetic, meditative, and monastic way of life constituted a challenge to the traditional Brahminic clerical class. Even though Asoka seems to have relied on both traditional Brahmin priests and Buddhist ascetics, his conversion raised questions about some of the rites and animal sacrifices performed by the Brahmins. In fact, it was allegedly in reaction to competition from Buddhist ascetics and to enhance their prestige in the eyes of the other classes that the Brahmins became strict vegetarians.

In any case, the Manusmriti clearly expresses a desire to place (or replace) learned Brahmins at the heart of the political system. The authors plainly believed that the time had come to promote their preferred model of society by drafting and circulating a wide-ranging legal and political-ideological treatise. The other chief complaint that emerges from the text is related to the fact that the Maurya emperors themselves were descended from military leaders risen from the ranks and born into the lower class of Shudras. Brahmins leveled the same criticism at any number of the other dynasties that succeeded one another in northern India before and after Alexander the Great’s invasion of the northwestern Indian subcontinent in 326 BCE.

What the Manusmriti proposes is a social structure and rules intended to end the permanent chaos and restore order to the Hindu social and political system: Shudras are encouraged to remain in their place at the bottom of the social hierarchy while kings must be chosen among the Kshatriyas under the strict supervision of learned Brahmins.8 In practice, the Brahmins’ demand that kings be chosen from among the authentic Kshatriyas (which can be read more prosaically as a demand that kings and warriors submit to the wisdom of the Brahmins and that the ceaseless changes of political and military power should come to an end) would never be fully satisfied. As in European and all other human societies, the warrior elites of India’s various regions would continue to battle one another for superiority, and the eternal task of the intellectuals, no less in India than anywhere else, would be to impose discipline on the warriors or, at the very least, insist on a modicum of respect for their vast knowledge.

The Brahmin discourse in the Manusmriti should of course be analyzed as the centerpiece of a bid for social and political dominance. As with the trifunctional schema put forward by bishops in medieval Europe, its primary objective was to see to it that the lower classes accepted their fate as workers subordinate to the priests and warriors. The Indian text added a further fillip: a theory of reincarnation. Members of the lowest varna, the Shudras, could in theory be reincarnated as members of higher varnas. Conversely, members of the first three varnas—Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas—were twice-born: the ceremony by which they were initiated into their varna was regarded as a second birth, which entitled them to wear a sacred thread, the yagyopavita, across their breast. The logic here was in a sense the opposite of the logic of meritocracy, with its exaggerated emphasis on individual talent and merit. In the Brahminic system, each individual occupies an assigned place and works together with all the others like the various parts of a single body to ensure social harmony; in a future life, however, the same individual might just as well occupy another place. The point was to ensure earthly harmony and avoid chaos while making use of acquired or inherited knowledge and skills; personal effort and discipline might be required, and individual advancement was not impossible, but the process must not lead to unbridled social competition, which would threaten the stability of the society. One finds in all civilizations the idea that strict assignment of social positions and political functions can serve as a check on hubris and ego; this is often used as a defense of hereditary hierarchies, especially in monarchic and dynastic systems.9

Brahminic Order, Vegetarian Diet, and Patriarchy

Like the Christian trifunctional schema, the Brahminic order expressed an ideal equilibrium of different forms of legitimacy. In both, the goal was to make sure that kings and warriors, the embodiment of brute force, did not neglect the wise counsel of learned clerics and that political power availed itself of the power of knowledge and intellect. Recall that Gandhi, who criticized the British for having taken once-fluid caste divisions and made them more rigid to better divide and conquer India, also took a rather respectful conservative position with respect to the Brahmin ideal.

Of course, Gandhi fought for a less inegalitarian, more inclusive society, particularly regarding the lower classes of Shudras and “untouchables,” a category even lower than the Shudras which included those whom the Hindu order relegated to the margins, many of whom were engaged in occupations deemed unclean, such as the slaughter of animals or the tanning of animal hides. But Gandhi also insisted on the essential role of Brahmins—or at any rate those whom he took to behave like Brahmins, namely, without arrogance or greed but with kindness and magnanimity, using their knowledge and learning for the benefit of society. Himself a member of the twice-born Vaishya caste, Gandhi defended (in a number of speeches, especially one delivered in Tanjore in 1927) the functional complementarity that he believed to be the basis of traditional Hindu society. By recognizing the principle of heredity in the transmission of talents and occupations, not as an absolute, rigid rule but as a general principle allowing for individual exceptions, the caste regime assigned a place to everyone, thus avoiding unbridled competition among social groups, the war of all against all, and therefore the kind of class warfare that existed in the West.10 Gandhi was particularly wary of the anti-intellectual aspects of anti-Brahmin discourse. Although not a Brahmin himself, he associated himself through his personal practice with the Brahmin virtues of sobriety and wisdom, which he believed were indispensable for achieving general social harmony. He was also wary of Western materialism and its boundless thirst for wealth and power.

More broadly, Brahminic domination always had an intellectual and civilizing dimension, especially with respect to mores and diet. The slaughter of animals was prohibited, and the strict vegetarian diet reflected (then and now) not only an ideal of purity and asceticism but also a supposedly more responsible attitude toward nature and the future. Slaughtering a cow might make for a feast today but did nothing to lay the groundwork for the future harvests needed to feed the broader community over the long run. Brahmins also denied themselves the use of alcohol. Their moral code was strict, particularly with respect to women (widows were forbidden to remarry, and arranged marriages involving prepubescent girls and under strict parental control was the norm), whereas the lower castes were regularly accused of debauchery.

It is important to insist once again on the fact that the Manusmriti, like the medieval texts in which Christian monks and bishops set forth their descriptions of the trifunctional schema, was a theoretical account of a political-ideological ideal type, not a description of an actual society. The authors believed that one could and should seek to emulate this ideal, but the reality of power relations at the local level was always more ambiguous. In the high Middle Ages in Europe, the ternary schema was clearly understood to be an idealized normative construct conceived by a handful of clerics rather than an operational description of social reality. The actual elite was more complicated, and it was difficult to discern a single, unified nobility.11 It was only in the final stages of transformation of trifunctional society—as revealed, for example, by the Swedish censuses of the mid-eighteenth century and beyond or, more generally, in the transition to absolutism, proprietarianism, and censitary voting in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Europe, and especially in Britain and France—that the ternary categories began to harden even as they were about to disappear, culminating a long process at the center of which lay the construction of the centralized modern state and the unification of legal statuses.12

Similarly, in the Indian context, society was in practice composed of thousands of overlapping social categories and identities, partly reflected in specific occupational guilds and military and religious roles but also related to dietary and religious practices, some of which depended on access to different temples or sites. These thousands of distinct groups, which the Portuguese called “castes” (castas) when they discovered India in the early sixteenth century, were only loosely related to the four varnas of the Manusmriti. The British, whose knowledge of Hindu society came largely from books like the Manusmriti, one of the first Sanskrit texts translated into English at the end of the eighteenth century, met with great difficulty when it came to fitting these complex professional and cultural identities into the rigid framework of the four varnas. Yet fit them they did, especially the lowest and highest groups, because doing so seemed to them the best way to understand and control Indian society. From this encounter and this project of simultaneous understanding and domination came a number of essential features of today’s India.

The Multicultural Abundance of the Jatis, the Quaternary Order of the Varnas

There is a great deal of confusion about the meaning of “caste,” about which I want to be clear. The word “caste” is often used to refer to occupational or cultural micro-groups (called jatis in India), but in some cases it is also used to refer to the four major theoretical classes of the Manusmriti (varnas). The two terms refer to two very different realities, however. The jatis are elementary social units with which individuals identify at the most local level of society. There are thousands of jatis across the vast Indian subcontinent corresponding to both specific occupational groups and specific regions and territories; they are often defined by complex mixtures of cultural, linguistic, religious, and culinary identities. In Europe one might speak of masons from the Creuse, carpenters from Picardy, wet nurses from Brittany, chimney sweeps from Wales, grape harvesters from Catalonia, or dockworkers from Poland. One of the peculiarities of the Indian jatis—and probably the main distinctive feature of the Indian social system overall—is the persistence to this day of a very high degree of endogamy within jatis, although it is also the case that exogamous marriage has become much more common in urban milieus. The important point is that the jatis do not reflect any hierarchy of social identities. They are occupational, regional, and cultural identities, which are in some ways comparable with national, regional, and ethnic identities in the European or Mediterranean context; they serve as the foundation of horizontal solidarities and networks of sociability, not of a vertical political order like the varnas.

The confusion between jatis and varnas stems in part from Indian history itself: certain Indian elites tried for centuries to organize society hierarchically around the four varnas, and while they met with some success, it was neither total nor lasting. The confusion was compounded when the British colonizers tried to fit the jatis within the framework of the varnas and give the whole setup a stable, bureaucratic existence with the colonial government’s stamp of approval. One consequence of this was to make certain social classifications considerably more rigid than they had been, starting with the Brahmins, a category that included hundreds of jatis of vaguely Brahminic priests and scholars whom the British were determined to treat as a single class throughout the subcontinent, partly to assert their own power at the local level but more importantly to simplify India’s infinitely complex and indecipherable social reality—the better to dominate it.

Hindu Feudalism, State Construction, and the Transformation of Castes

Before turning to the censuses conducted by the British Raj, it will be useful to review what we know about Indian social structures before the arrival of the British in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and thus before the invention of “castes” in their colonial form. Our knowledge is limited, but it has progressed over the past few decades. Broadly speaking, recent work has shown that social and political relations in India were in constant flux from the fifteenth to the eighteenth centuries. The processes of change were probably not very different from those observed in Europe in the same period when the traditional trifunctional feudal system came into conflict with the construction of centralized states. In saying this I do not mean to deny the specificity of the Indian caste system or the inegalitarian political and ideological regime associated with it. Among its distinctive features were an emphasis on ritual and dietary purity, strong endogamy within jatis, and specific forms of separation and exclusion dividing upper from lower classes (untouchables). If we are to understand the variety of possible historical trajectories and switch points, however, we also need to insist on the features that the Indian and European cases share in common, especially in regard to trifunctional political organization and social conflict and transformation.

The European colonizers liked to depict the Indian caste system as frozen in time and totally alien because this allowed them to justify their civilizing mission and entrench their power. India’s castes were the living incarnation of oriental despotism, utterly opposed to European realities and values: in this respect they constitute the paradigmatic example of an intellectual construct whose purpose was to justify colonial rule. Abbé Dubois, who in 1816 published one of the first works on “the mores, institutions, and ceremonies of the peoples of India”—a work based on the sparse testimony of a few late-eighteenth-century Christian missionaries—was firm in his conclusion. First, it was impossible to convert the Hindus, because they were under the influence of an “abominable” religion. Second, the castes provided the only means of disciplining such a people. This says it all: castes are oppressive, but use must be made of them for the purpose of imposing order. Many British, German, and French scholars ratified this view in the nineteenth century, and this understanding persisted to the middle of the twentieth century and sometimes beyond. Max Weber’s work on Hinduism (published in 1916), like that of Louis Dumont’s (published in 1966), described a caste system which in broad outline had not changed since the Manusmriti, topped by the eternal Brahmins, whose purity and authority no other social group had seriously contested.13 Both authors relied primarily on classic Hindu texts and normative religious legal treatises, starting with the Manusmriti, which they frequently cited. Although their judgment of Hinduism was more measured than Abbé Dubois’s, their approach remains relatively textual and ahistorical. They did not attempt to study Indian society as a conflictual and evolving sociopolitical process, nor did they explore sources that might have allowed them to analyze the transformations of that society. Instead, they sought to describe a society they assumed from the outset to be eternal and unchanging.

Since the 1980s a number of scholars relying on new sources have begun to fill in the gaps in our knowledge. Unsurprisingly, Indian societies turn out to have been complex and ever changing; they bear little resemblance to the frozen caste structures depicted by colonial administrators or to the theoretical varna system one finds in the Manusmriti. For example, Sanjay Subrahmanyam has compared Hindu and Muslim chronicles and other sources to study the transformations of power and court relations in Hindu kingdoms and Muslim sultanates and empires in the period 1500–1750. The multiconfessional dimension appears to be central to understanding the dynamics at work here; by contrast, scholars in the colonial era tended to treat the Hindu and Muslim societies of the subcontinent separately, as watertight entities governed by different social and political logics (when they did not simply ignore the Muslim societies altogether).14 Among Muslim states, it is also important to distinguish between Shiite sultanates such as that of Bijapur and Sunni states such as the Mughal Empire, although we find in both similar elites, practices, and ideas about the art of governing pluralistic communities. Their methods of government were nevertheless quite different from those of the British colonizers, and none of these states ever organized a census comparable with the colonial censuses conducted by the British.15

In addition, Susan Bayly and Nicholas Dirks have shown that the military, political, and economic elites of Hindu kingdoms were frequently renewed by infusions of new blood and that the warrior classes often dominated the Brahmins rather than the other way around. More broadly, the social structures of both Hindu states and Muslim sultanates were shaped by property and power relations similar to those observed in France and Europe. For example, we find systems in which several rents were paid on the same piece of land, with free peasants paying both local Brahmins and local Kshatriyas for their respective religious and regalian services, while some groups of rural workers, classified as Shudras, were not allowed to own land and were relegated to a status closer to serfdom. Relations among these groups had social, political, and economic—as well as religious—dimensions and evolved as the balance of political and ideological power shifted.

The case of the Hindu kingdom of Pudukkottai in southern India (present-day Tamil Nadu) is illuminating. There, a small, energetic local tribe, the Kallars, who elsewhere were considered a low caste and whom the British would later classify as a “criminal caste” (the better to subjugate them), seized power and set itself up as a new royal warrior nobility in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In the end the Kallars forced the local Brahmins to swear allegiance to them, in exchange for which priests, temples, and Brahminic foundations were rewarded with tax-exempt land. Power relations of this sort are reminiscent of those that existed in feudal Europe between the Church and its monasteries on the one hand and new noble and royal classes on the other, regardless of whether the latter emerged through conquest or rose from the ranks, which happened regularly in both Europe and India. It is interesting to note that it was not until the British strengthened their hold on the Pudukkottai kingdom in the second half of the nineteenth century, at the expense of the Hindu warrior class and other local elites, that the Brahmins saw their influence increase and their preeminence recognized, which allowed them to impose their own religious, familial, and patriarchal norms.16

More generally, the collapse of the Mughal Empire around 1700 contributed to the rise of numerous Hindu kingdoms built around new military and administrative elites. To establish their dominance, these groups and their Brahmin allies then turned to the old ideology of the varnas, which enjoyed a certain renaissance in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, all the more so because the new state forms made it possible to apply the religious, familial, and dietary norms of the upper castes on a much broader scale and in a more systematic fashion. The founder of the Maratha Empire, Shivaji Bhonsle, was initially a member of the Maratha peasant class who had served as a tax collector for Muslim sultanates allied with the Mughal Empire. After consolidating power in an independent Hindu state in western India in the 1660s and 1670s, he demanded that local Brahmin elites recognize him as a twice-born Kshatriya. The Brahmins hesitated, some on the grounds that the authentic Kshatriyas and Vaishyas of ancient times had disappeared with the arrival of Islam. Shivaji ultimately obtained the recognition he wanted by way of a scenario with which we are by now familiar, one that was frequently replayed in both India and Europe: a compromise was struck between the new military elite and the old religious one to achieve the much-desired social and political stability. In Europe, one thinks of Napoleon Bonaparte being crowned emperor by the Pope, like Charlemagne a thousand years before him, before rewarding his generals, family, and loyal followers with titles of nobility.

In Rajasthan, new groups of Kshatriyas, the Rajputs, emerged in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries from local landowning and warrior classes, on which Muslim sovereigns and later the Mughal Empire sometimes relied to maintain social order; some succeeded in negotiating their way to autonomous principalities.17 The British also sought support among the upper classes or portions thereof, depending on their interests at the moment. In the case of Shivaji’s kingdom, Brahmin ministers known as peshwas ultimately became hereditary rulers in the 1740s. But they got in the way of the East India Company, which decided to depose them in 1818 on the grounds that they had usurped a Kshatriya role to which they had no right, thereby winning the British the support of those who had taken a dim view of the unusual seizure of political power by Brahmin scholars.18

On the Peculiarity of State Construction in India

The conclusion that emerges clearly from this work is that Hindu varnas were no more solid in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries than were European classes and elites in the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, or the Ancien Régime. The varnas were flexible categories that enabled groups of warriors and priests to justify their rule and paint an image of a durable and harmonious social order, whereas in reality that order evolved constantly as the balance of power shifted among social groups. All of this unfolded in a context of rapid economic, demographic, and territorial development accompanied by the emergence of new commercial and financial elites. Indian society in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries thus appears to have been evolving just as much as European society. It is of course impossible to say how the various societies and states of the Indian subcontinent would have evolved in the absence of British colonization. It is not unreasonable to think, however, that status inequalities stemming from the ancient trifunctional logic would gradually have disappeared through the process of central state formation in the same way we have observed in Europe—and, as we will see in Chapter 9, in China and Japan.

Within this overall pattern, however, there exists a broad spectrum of possibilities. In the European case we have already noted the diversity of possible trajectories and switch points. In Sweden, for example, large property owners joined the old nobility in creating a political system (1865–1911) in which the number of votes a person could cast was strictly proportional to that person’s wealth.19 Had Brahmins and Kshatriyas been left to their own devices, they would no doubt have proved to be just as imaginative (perhaps by awarding votes on the basis of the number of diplomas or ascetic lifestyle or dietary habits, or simply on the basis of property and taxes paid) before being driven from power by a popular uprising. Because there are so many structural differences between Indian and European inequality regimes, the number of possible trajectories one can imagine is especially large.

If we take the long view, the main difference between India and Europe probably has to do with the role of Muslim kingdoms and empires. In vast swathes of the Indian subcontinent, regalian powers were exercised by Muslim sovereigns for centuries, in some cases from the twelfth or thirteenth centuries to the eighteenth or nineteenth. Under these conditions, the prestige and authority of the Hindu warrior class would clearly have suffered. In the eyes of many Brahmins, the authentic Kshatriyas had quite simply ceased to exist in many parts of the country, even though in practice the Hindu military classes often played supporting roles under Muslim princes or retreated into independent Hindu states and principalities like the Rajputs in Rajasthan. The relative retreat of the Kshatriyas also increased the prestige and preeminence of Brahmin intellectual elites; this retreat allowed the Brahmins to fulfill their religious and educational functions on which Muslim sovereigns (and later the British) relied to uphold the social order, often going so far as to validate and enforce judgments handed down by Brahmins concerning dietary or familial laws or access to temples, water, and schools, in some cases even imposing excommunication. Compared with other trifunctional societies not only in Europe but also in other parts of Asia (especially China and Japan) and around the world, this may have led to a certain imbalance between the religious and warrior elites, enhancing the importance of the former or even leading in some regions to a quasi-sacralization of the power of the Brahmins, which was temporal as well as spiritual. As we have seen, however, the balance of power could shift very quickly, leading to the emergence of new Hindu states backed by new military and political elites.

The second important difference between the Indian and European cases has to do with the fact that the Brahmins were a true social class unto themselves, with families and children, accumulated wealth and inheritances, whereas the Catholic clergy had to replenish its ranks from the other classes owing to the celibacy of priests. We saw how this led in the European society of orders to the emergence of ecclesiastical institutions and religious organizations (such as monasteries, bishoprics, and the like), which accumulated significant amounts of property on behalf of the clergy and thus also led to the development of sophisticated economic and financial rules.20 This may also have made the European clerical class (which was not really a class) more vulnerable. The decisions to expropriate monasteries in Britain in the sixteenth century or to nationalize clerical property in France in the late eighteenth century were not easy, to be sure, but no hereditary class was affected. On the contrary: the nobility and bourgeoisie benefited substantially. In India, expropriation of Brahmin temples and religious foundations would have to have been more gradual, although the development of new nonreligious ruling classes in Hindu kingdoms in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries again shows that it wouldn’t have been impossible. In any case, we will see that when British colonization interrupted the autochthonous state construction process, census reports show that the Brahmin class commanded a very large share of the wealth as well as of educational, cultural, and professional resources.

The Discovery of India and Iberian Encirclement of Islam

Before analyzing how the British sought to take the measure of India’s castes with its colonial censuses in the nineteenth century, it will also be useful to remind the reader that Europe’s discovery of India came in stages and originated in an unusual quest, based on quite limited knowledge. Much research, especially the work of Sanjay Subrahmanyam (based on systematic comparison of Indian, Arab, and Portuguese sources), has shown that Vasco da Gama’s expedition in 1497–1498 was based on numerous misunderstandings.

During the second half of the fifteenth century, the Portuguese government was deeply divided over the issue of overseas expansion. One faction of the landed nobility was content with the success of the Reconquista and opposed to further action against Islam. But the Military Orders, especially the Orders of Christ and Santiago (to which da Gama’s family belonged), having played a key role in mobilizing the lesser warrior nobility during the era of “reconquest” of Iberian territory from Islam, favored pursuing the Moors to the coast of Morocco and pushing them back as far as possible from Christian shores. The boldest warriors proposed further exploration of the African coast in order to outflank the Muslims to the south and east and ultimately link up with the mythical “Kingdom of Prester John.” This apocryphal Christian kingdom, inspired by Ethiopia, played an important part in Europe’s confused representations of global geography from the era of the Crusades (eleventh to thirteenth centuries) to the Age of Discovery, fostering hopes of ultimate victory over Islam. The ambitious strategy of encircling the Muslim enemy did not command unanimous support, however, and ideological conflict between the landed faction and the imperial anti-Islamic faction gave the Portuguese monarch pause. In the face of pressure from the Orders, which he wanted to keep tethered to the monarchy, the king finally decided in 1497 to send da Gama on his voyage with orders to round the Cape of Good Hope, which Bartolomeu Dias had discovered ten years earlier.

Thanks to surviving sailors’ accounts (some of which lay undiscovered until the nineteenth century) and comparison with Arabic and Indian sources, it has been possible to reconstruct the various stages of the voyage in considerable detail.21 After leaving Lisbon in July 1497, da Gama’s three ships reached the South African coast in November and then set sail slowly northward along the east coast of Africa, stopping at Muslim ports in Mozambique, Zanzibar, and Somalia in search of Christians, whom the Portuguese never found. At the time, Indian Ocean commerce was the province of Arabs, Persians, Gujaratis, Keralans, Malays, and Chinese, whose intersecting networks encompassed a vast multilingual region and brought large imperial and agrarian states (under the Vijayanagara, Ming, Ottomans, Safavids, and Mughals) into contact with small commercial coastal states (Kilwa, Ormuz, Aden, Calicut, Malacca). Disappointed by these unanticipated encounters and worried about the hostility of Muslim merchants, da Gama continued on his way, reaching the Indian coast in May 1498. A series of tense encounters and blunders ensued, most notably in Calicut (in present-day Kerala in the south of India). Da Gama visited Hindu temples that he mistook for the churches of a Christian kingdom, to the astonishment of the Brahmins, who were equally surprised by the very modest gifts tendered by a man who claimed to be representing the greatest kingdom in Europe. Da Gama finally returned to Lisbon under difficult conditions.

In July 1499 the king of Portugal proudly announced to his fellow Christian kings that the route to the Indies was open and that his envoy had discovered on the Indian coast a number of Christian kingdoms, including one in Calicut, “a city larger than Lisbon and inhabited by Christians.”22 It was several years before the Portuguese awoke to their mistake and realized that the sovereigns of Calicut and Kochi were Hindus who traded with Muslims, Malays, and Chinese; and before long these Hindu sovereigns were at war with one another over which of them would do business with the Christians. Da Gama returned to Kochi as viceroy of the Indies in 1523 to defend the Portuguese trading posts that were by then numerous in Asia. In the meantime, in 1500, Cabral had discovered Brazil (as da Gama had come close to doing in 1499 on his way back from India), and Magellan had sailed around the world in 1521.

It would take an even longer time for the nature of Portugal’s imperial project to change. The messianic dimension—to promote Christianity over Islam—would continue to play a central role throughout the sixteenth century, especially after the founding of the Society of Jesus (Jesuits) in 1540. This outsized messianic motive explains, by the way, how a tiny country of barely 1.5 million people could have set out to conquer the world, to say nothing of countries that not only had much larger populations but also were in many respects more advanced. The mercantile motive never entirely eclipsed the messianic. In the Dutch case, however, the mercantile motive was paramount: the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC, or Dutch East India Company), one of the first large joint-stock companies in the world, was founded in 1602. Over the course of the seventeenth century it would gradually take over many of Portugal’s Asian trading posts.23 In 1511 the Portuguese had occupied the strategic port of Malacca, ending the Muslim sultanate that had controlled a crucial strait on the maritime route connecting India to China, between today’s Malaysia and the island of Sumatra (Indonesia). The Dutch took Malacca from the Portuguese in 1641 before ceding sovereignty to it as well as Singapore to the British in 1810.

Unlike the Portuguese, the Spanish built their empire on dry land: it grew rapidly, starting with the occupation of Mexico by Hernan Cortes in 1519 and of Cuzco and Peru by Francisco Pizarro in 1534. By the 1560s Spanish navigators had mastered the Pacific currents, enabling them to cross in both directions, thus linking Mexico to the Philippines and the Asian parts of the empire. In the early 1600s Mexico was truly the multicultural heart of the Spanish Empire, the place where “the four corners of the world” evoked by Serge Gruzinski came together at a time when states exerted less control over borders and identities than they would later. There, the mixing of blood among Mexican Indians, Europeans, Brazilian mulattos, Filipinos, and Japanese led to some astonishing mises en abîme by chroniclers writing in different languages and representing different cultures. The Catholic monarchy of Spain, which at its zenith absorbed Portugal under a single crown (1580–1640), once again faced Islam as its global rival, including in the Philippines and Moluccas (Indonesia)—where Muslims had gained a foothold shortly before the arrival of the Iberians and where Spanish soldiers had not expected to find their old European rivals so far from Grenada and Andalusia, from which they had just expelled the last infidels in 1492, the very year in which Columbus landed in Hispaniola (Saint-Domingue) while searching for the Indies.24

Domination by Arms, Domination by Knowledge

When Europeans arrived in India and found Muslim sultanates and empires playing a major role there, they naturally took the side of the Hindu kingdoms against their Muslim rivals. Religious, commercial, and military conflicts soon arose, however. After the messianic era came the mercantile era, embodied to perfection by the Dutch VOC and the British East India Company (EIC). These joint-stock companies, founded in the early 1600s, were much more than trading companies to which European monarchs had granted commercial monopolies. They were in fact private companies charged with exploiting vast regions of the world and maintaining order at a time when the boundary between public functions (such as tax farming) and lucrative state-licensed private businesses was extremely porous. In the middle of the eighteenth century, especially in the wake of English victories over Bengali armies in the 1740s, the EIC took de facto control of great swathes of the Indian subcontinent. The EIC maintained veritable private armies made up mainly of Indian soldiers paid from its coffers. It extended its control by taking advantage of the void left by the collapse of the Mughal Empire and the rivalry between contending Hindu and Muslim powers.

Nevertheless, the many abuses that the EIC committed on Indian soil quickly led to notorious scandals. By the 1770s members of Parliament were calling on the Crown to tighten its oversight of the EIC. One of the most outspoken critics was the conservative philosopher Edmund Burke, famous today for his Reflections on the French Revolution (1790). Burke insisted on the need to put an end to the corruption and brutality of the company’s agents, and after a tense trial in the House of Commons in 1787 he succeeded in impeaching Warren Hastings, the former head of EIC and governor-general of Bengal. Although Hastings was ultimately acquitted by the House of Lords in 1795, British elites were increasingly convinced that Parliament needed to play a greater role in the colonization of India. It was felt that Britain’s civilizing mission could proceed only on the basis of rigorous administration and solid knowledge and that sovereignty could no longer be delegated to a gang of greedy traders and mercenaries. Administrators and scholars were needed.

Edward Saïd, in his book on the origins of “orientalism,” showed how important this new colonial presence in Asia was. Henceforth domination was to depend not just on brute military force but more on cognitive, intellectual, and civilizational superiority.25 Saïd notes that this cognitive moment, which followed the messianic and mercantilist eras, found its first embodiment in Bonaparte’s Egypt expedition (1798–1801). Of course, there was no shortage of political, military, and commercial motives for this adventure, but the French were careful to insist on the scientific aspects of the campaign. Some 167 scholars, historians, engineers, botanists, draftsmen, and artists accompanied the soldiers, and their discoveries led to the publication between 1808 and 1828 of twenty-eight large-format volumes of “Descriptions of Egypt.” The residents of Cairo, who rose up in late 1798 to drive out the French, were clearly not entirely convinced of the disinterested motives of these civilizing benefactors, any more than were the Egyptian and Ottoman soldiers who, with support from the British Navy, sent the expedition packing back to France in 1801. This episode nevertheless marked a historical turning point: henceforth colonization would more and more often be portrayed as a civilizing necessity, a service rendered by Europe to civilizations frozen in time and unable to evolve or to discover their own identities, much less preserve their historical legacy.

In 1802 François-René de Chateaubriand published his Génie du christianisme, followed in 1811 by Itinéraire de Paris à Jérusalem, both of which directed harsh criticism at Islam and justified the civilizing role of the Crusades.26 In 1833 the poet Alphonse de Lamartine published his famous Voyage en Orient, in which he theorized the European right to sovereignty over the Orient even as France was waging a brutal war of conquest in Algeria. No doubt these violent civilizational discourses can be read as a response to a major hidden European trauma. For a millennium, from the first Muslim incursions into Spain and France in the early eighth century to the decline of the Ottoman Empire in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Christian kingdoms had feared that they might never see the end of the Muslim states that had seized control of the Iberian peninsula and Byzantine Empire and occupied much of the Mediterranean coast. This ancient but ultimately banished existential fear found clear expression in the writing of Chateaubriand, along with a centuries-old thirst for revenge, whereas Lamartine insisted more on the mission to preserve and civilize.

Saïd showed that the influence of orientalism on Western representations continued well after the colonial period. The refusal to historicize “oriental” societies, the insistence on essentializing them and portraying them as frozen in time, eternally flawed and structurally incapable of governing themselves—ideas that justify every kind of brutality in advance—continued, Saïd argued, to permeate European and American perceptions in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries: for example, at the time of the invasion of Iraq in 2003. Orientalism yielded scholarship and knowledge along with specific ways of looking at remote societies, specific modes of knowledge that for a long time explicitly served the political purposes of colonial domination and often continued to reflect their initial biases in postcolonial academia and society. Inequality is not simply a matter of social disparities within countries; it is also at times a clash of collective identities and models of development. Their respective merits and limitations might in theory be subjects for calm and constructive debate, but in practice they are often transformed into violent clashes of identity. This is as much the case today as in centuries past, despite important contextual changes. Hence it is essential to describe the historical genealogy of these conflicts to gain a better understanding of what is currently at stake.

British Colonial Censuses in India, 1871–1941

We turn now to the records of the censuses conducted by the British colonizers in the Indian Empire. Although the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857–1858 was quickly put down, it frightened the colonial authorities and convinced them of the need for direct administration. To that end, they needed a better understanding of India’s land tenure systems in order to levy taxes. They also needed to know more about local elites and social structures, especially castes, which they only dimly understood but feared might foster group solidarity and thus lead to future revolts. The first experimental censuses were conducted in northern India in 1865 and 1869 in the “Northwestern Provinces” and in Oudh, which in the administrative subdivision of the early British Raj corresponded roughly to the Ganges valley and present-day Uttar Pradesh (population 204 million according to the 2011 census; already more than 40 million at the time of the first censuses). The census was then extended to the entire population of the Indian Empire in 1871—some 239 million people, of whom 191 million lived in areas under direct British administration and 48 million in principalities under British tutelage. The census was then repeated in 1881, 1891, and every ten years thereafter until 1941. After each census the authorities published hundreds of thick volumes presenting thousands of tables for every province and district, relating caste to religion, occupation, education, and in some cases land ownership. These volumes attest to the immensity of the undertaking, which involved thousands of census takers and covered vast expanses of territory—an eminently political enterprise. Questions were posed in the various Indian languages and then translated into English, eventually yielding thousands upon thousands of pages. These documents, together with the many reports and pamphlets that record the hesitations and doubts of colonial administrators and scholars, tell us at least as much about the nature of colonial rule as about the social realities of India.

The British initially approached the exercise through the prism of the four varnas of the Manusmriti but soon realized that these categories were not very useful. The individuals surveyed identified instead with the jatis, a broader and more fluid set of social classifications. The problem was that colonial administrators had no complete list of jatis, and the people they were interviewing had extremely diverse opinions about what jatis were most relevant and how they should be grouped. Many Indians must also have wondered why these strange British lords and their census-taking agents were so interested in their identities, occupations, and diets and so determined to have their views on social classifications and ranks. The 1871 census enumerated some 3,208 different “castes” (in the sense of jatis); by 1881 the number had risen to 19,044 distinct groups, including subcastes. The average population of each caste was less than 100,000 in the first census and less than 20,000 in the second. Often these “castes” were merely small local occupational groups present only in limited areas. It was very difficult to discern any order in such data, let alone produce knowledge of use on an imperial scale. To get an idea of the scope of the undertaking, try to imagine how an Indian sovereign taking control of Europe in the eighteenth or nineteenth centuries might have gone about conducting a census across the continent from Brittany to Russia and Portugal to Scotland, classifying people by occupation, religion, and dietary preferences. No doubt they would have invented categories that would surprise us today.27 But the fact is that by producing these categories and using them to administer the country, the British colonizers exerted a deep and lasting impact on Indian identities and on the structure of Indian society itself.

Some colonial administrators also explored racialist explanations. They started with the premise that, according to certain Hindu myths, the varnas were rooted in racial differences from the era of conquest. Light-skinned Aryans from Iran, to the north, had supposedly invaded the Ganges valley before moving into southern India, perhaps early in the second millennium BCE; their descendants became Brahmins, Kshatriyas, and Vaishyas, according to the myths, while the darker-skinned natives and even blacks in the southernmost parts of the subcontinent became subjugated Shudras.28 Many administrators and scholars therefore set about measuring skulls and jawbones and examining noses and skin textures in the hope of discovering the secret of India’s castes. Herbert Risley, an ethnographer who was appointed census commissioner in 1901, argued that, if the British wished to beat the Germans in the area of racial research, a field in which German scholars were particularly active at the time, it was of the utmost strategic importance to study the races of India.29 In practice, the racial approach yielded no tangible results because most castes exhibited thoroughly mixed ethnic and racial origins.

Even earlier, in 1885, John Nesfield—an administrator who had been assigned the job of reflecting on new classifications that might better capture the reality of Indian society and who believed that castes should be thought of primarily as occupational groups—was already aware that racial theory was of little use in understanding castes. One had only to go to Benares, he remarked, where 400 young Brahmins were studying in the most prestigious Sanskrit schools. There, it was easy to see that they represented the full palette of skin colors from the entire subcontinent.30 Risley had his own theory on the subject. For one thing, the Brahmins had mixed thoroughly with other castes between the time of the Aryan invasions, early in the second millennium BCE, and the time when the Manusmriti recommended strict endogamy (around the second century BCE). For another, competition with Buddhism, which was especially intense from the fifth century BCE to the fifth century CE, had ostensibly led the Brahmins to incorporate many lower-caste Indians into their ranks. Finally, many Hindu rajahs had allegedly created new classes of Brahmins over the centuries to cope with the indiscipline of existing Brahmins.

The testimony of administrators like Nesfield is generally much more instructive than that of racialist ethnographers like Risley and Edgar Thurston because the administrators reported on interesting exchanges with the populations they were charged with counting. To be sure, Nesfield’s analysis reflects prejudices of his own as well as those of his interlocutors (who were drawn mainly from the upper castes), but those prejudices are themselves significant. For example, Nesfield explains that the aborigines and untouchables excluded themselves from the Hindu community by their behavior. Specifically, they were groups of hunters who lived in forests or on the outskirts of villages in a state of unimaginable filth, always on the brink of rebellion or plunder. They were denied access to temples because their morals were deplorable: they did not shrink from prostituting their own daughters when necessary. The topographic descriptions in this part of Nesfield’s account suggest that he is talking about isolated aboriginal tribes rather than untouchables as such, although he doesn’t always distinguish clearly between the two groups, particularly when he is discussing habitats on the outskirts of villages relatively far from the wooded and mountainous areas generally associated with aborigines. In any event, he is clearly referring to groups whose way of life was radically different from the norm.31

Nesfield adds that these pariah groups also included lesser agricultural castes whose morals and dietary customs linked them to the lowest of the low. He mentions in particular groups that still ate rodents such as nutrias and field rats, a deplorable practice proscribed centuries earlier by the Manusmriti. He also discusses certain occupational groups such as the chamars (tanners) and scavengers who collected human waste, garbage, and animal carcasses. According to Nesfield’s informants, their morals were also questionable, and their frequent public drunkenness and regrettable promiscuity did not escape his notice. He is convinced, moreover, that the less prestigious social classes generally performed tasks requiring the least knowledge and skills, such as basket weaving, an activity that he notes is common not only among the very lowest castes in India but also among the Roma in Europe. Conversely, those higher up the social ladder engaged in more sophisticated work such as pottery making, weaving, and at the very top of the craft hierarchy, metallurgy, glass making, jewelry making, and stone cutting. This same hierarchy is observed in other walks of life: hunters are less prestigious than fishermen, who are themselves less prestigious than farmers and breeders.

The most important Banyas (merchants) lived by a moral code similar to that of the Brahmins; in particular, their widows were forbidden to remarry. Nesfield also remarks that the former Kshatriya warriors, now called Rajputs (a term that initially designated individuals of royal blood) or Chattris (derived from Kshatriyas and kshatras, a term designating the owner of a landed estate), had lost much of their prestige under Muslim and then British domination. Some found employment as soldiers or police in the colonial service while others lived on the rent from their land and still others vegetated. In addition, Nesfield points out that the Brahmins have long since branched out from their original activity as priests and taken up work as teachers, doctors, accountants, and administrators while still collecting comfortable rents from others in their rural communities.

While recognizing that the administrative skills of the Brahmins were much more useful to the colonial authorities and that their talents were much better suited to modern times than those of the now-sidelined warriors, Nesfield argues that there are far too many Brahmins in relation to the services they render (up to 10 percent of the population in some parts of northern India). On the whole, he found that the Indian social hierarchy looked rather good apart from the excessive number of Brahmins, who truly abused their dominant position. The conclusion was obvious: the time had come for British administrators to replace them as the country’s leaders.

Enumerating Social Groups in Indian and European Trifunctional Society

What statistical results can we glean from the census data? Broadly speaking, colonial administrators had no idea how to group the thousands of jatis into intelligible categories, so the presentation of the results varied greatly from one census to the next. Some administrators, including Nesfield, proposed abandoning the varnas almost entirely in favor of an entirely new set of occupational classifications based on trades and skills, which Nesfield proposed to develop for use throughout imperial India. In reality, what the British decided to do from 1871 to 1931 was to classify every local group they believed to be related to the Brahmins under the head “brahmin.” Already in 1834 a survey had found 107 different Brahmin groups. In the communities that Nesfield studied, he, too, had distinguished numerous subgroups: the acharjas supervised religious ceremonies, the pathaks specialized in the education of children, the dikshits were in charge of initiation ceremonies for the twice-born, the gangaputras assisted priests, the baidyas served as physicians, the pandes were responsible for educating lower castes, and so on, to say nothing of the khataks and bhats, former Brahmins who became singers and artists, or again, the malis, a sophisticated agricultural caste specialized in the production of flowers and wreaths used in processions, who were sometimes counted as Brahmins. Nesfield estimated that only 4 percent of Brahmins were full-time priests, while 60 percent assisted in one way or another in religious functions to supplement their primary work as teachers, physicians, administrators, or landowners. In a sense this was a bourgeoisie of literate landowners who participated in the teaching of religion.

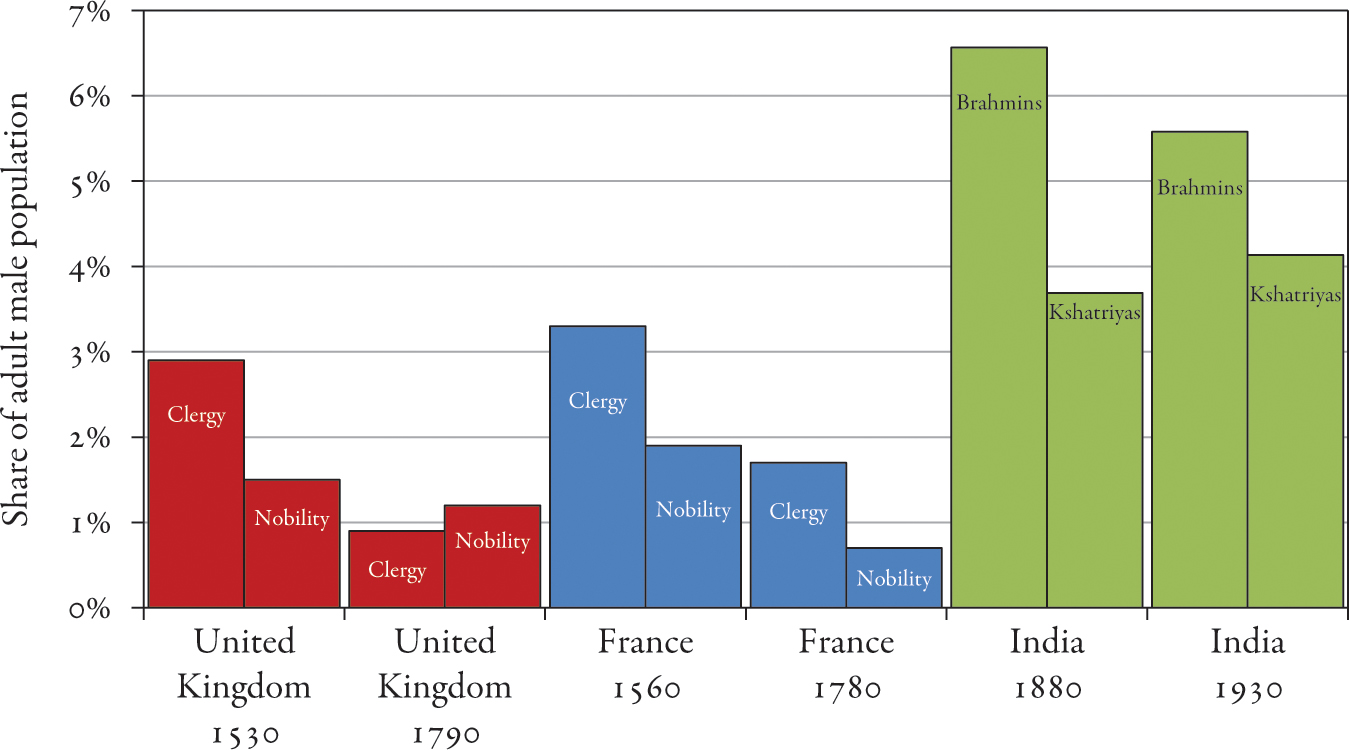

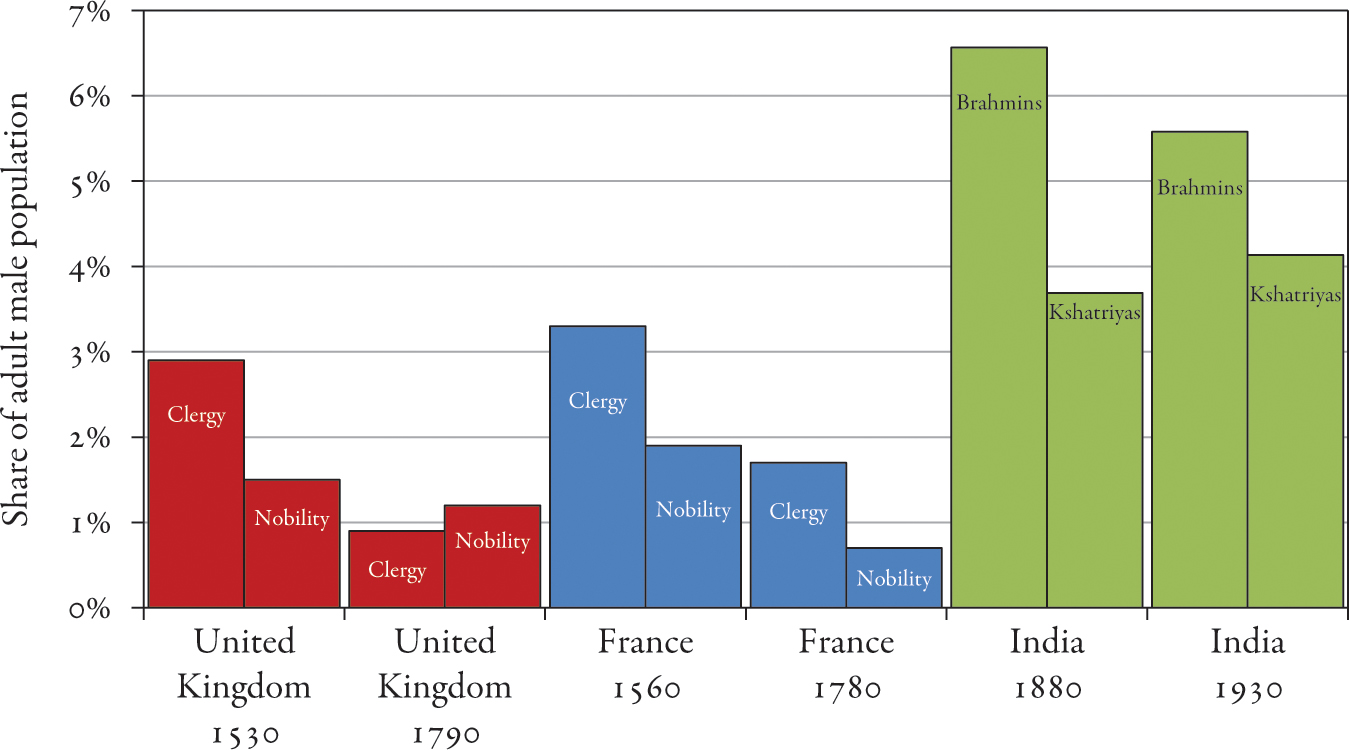

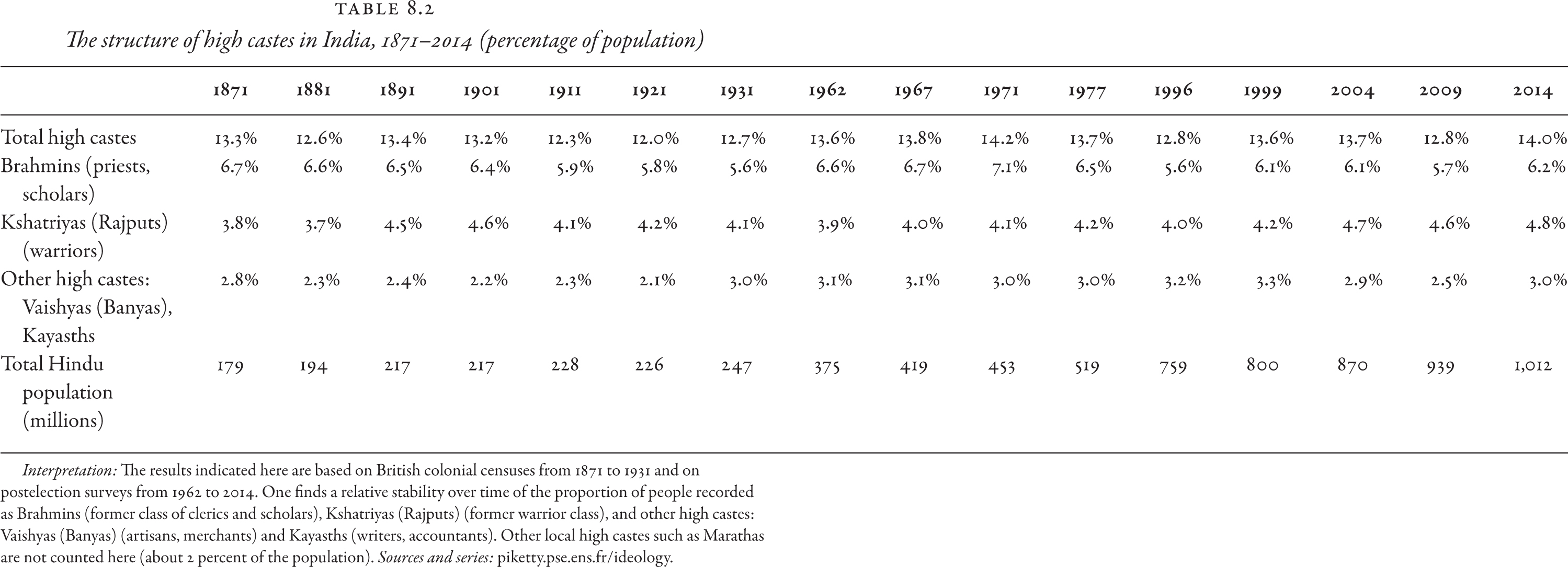

Across India, the proportion of the population categorized as Brahmins in British census reports was significant. In the census of 1881, we find 13 million Brahmins (including their families), or 5.1 percent of the total population of 254 million and 6.6 percent of the Hindu population of 194 million. Depending on the region and province, the proportion of Brahmins varied from barely 2 to 3 percent in southern India to roughly 10 percent in the Ganges valley and northern India, with Bengal (Calcutta) and Maharastra (Mumbai) close to the average (5–6 percent).32 As for the Kshatriyas, the census reports do not give a total figure because the term was rarely used explicitly and the colonizers declined to revive it. By adding up the numbers for the various castes of Chattris and especially Rajputs, which accounted for most of the total, we arrive at a figure of 7 million Kshatriyas in 1881, which amounts to 2.9 percent of the total population and 3.7 percent of the Hindu population, again with regional variations but less marked than in the case of the Brahmins (northern India was a little above average, while southern India and other regions were a little below). All told, we find that the two highest castes accounted for 10 percent of the Hindu population in 1881 (6–7 percent for the Brahmins and 3–4 percent for the Kshatriyas). A half century later, in the census of 1931, the proportion of Brahmins had decreased slightly (from 6.6 to 5.5 percent) while that of Kshatriyas had increased slightly (from 3.7 to 4.1 percent), but the total barely budged. According to the census data, Brahmins and Kshatriyas together accounted for 10.3 percent of the Hindu population in 1881 and 9.7 percent in 1931 (Fig. 8.3).33