{ SIXTEEN }

Social Nativism: The Postcolonial Identitarian Trap

In the previous chapters, we looked at the transformation of political and electoral cleavages in the United Kingdom, United States, and France since World War II. In particular, we saw how, in all three countries, the “classist” party systems of the period 1950–1980 gradually gave way in the period 1990–2020 to systems of multiple elites, in which a party of the highly educated (the “Brahmin left”) and a party of the wealthy and highly paid (the “merchant right”) alternated in power. The very end of the period was marked by increasing conflict over the organization of globalization and the European project, pitting the relatively well-off classes, on the whole favorable to continuation of the status quo, against the disadvantaged classes, which are increasingly opposed to the status quo and whose legitimate feelings of abandonment have been cleverly exploited by parties espousing a variety of nationalist and anti-immigrant ideologies.

In this chapter, we will begin by verifying that the evolutions observed in the three countries studied thus far can also be found in Germany, Sweden, and virtually all European and Western democracies. We will also analyze the singular structure of political cleavages in Eastern Europe (especially Poland). This illustrates the importance of postcommunist disillusionment in the transformation of party systems and the emergence of social nativism, which can be seen as a consequence of a world that is at once postcommunist and postcolonial. We will consider the extent to which it is possible to avoid the social-nativist trap and outline a form of social federalism adapted to the European situation. We will then study the transformation of political cleavages in non-Western democracies, notably India and Brazil. In both cases we will find examples of incomplete development of cleavages of the classist type, which will help us to gain a better understanding of both Western trajectories and the dynamics of global inequality. Finally, with all these lessons in mind, we will turn in the final chapter to the elements of a program for creating, in a transnational perspective, new forms of participatory socialism for the twenty-first century.

From the Workers’ Party to the Party of the Highly Educated: Similarities and Variants

To be clear from the outset: we will not be able to treat each of the subsequent cases in as much detail as we studied France, the United States, and the United Kingdom, partly because to do so would take us beyond the scope of this book and partly because the necessary sources are not available for all countries. In this chapter, I will begin with a relatively succinct presentation of the main results currently available for the other European and Western democracies. I will then analyze in greater detail the results for India (and in somewhat less detail for Brazil). Not only does India’s democracy include more voters than all the Western democracies combined, but study of the structure of the Indian electorate and of the transformation of India’s sociopolitical cleavages from the 1950s to the present illustrates the urgent need to go beyond the Western framework if we are to gain a better understanding of the political-ideological determinants of inequality as well as the conditions under which redistributive coalitions can be assembled.

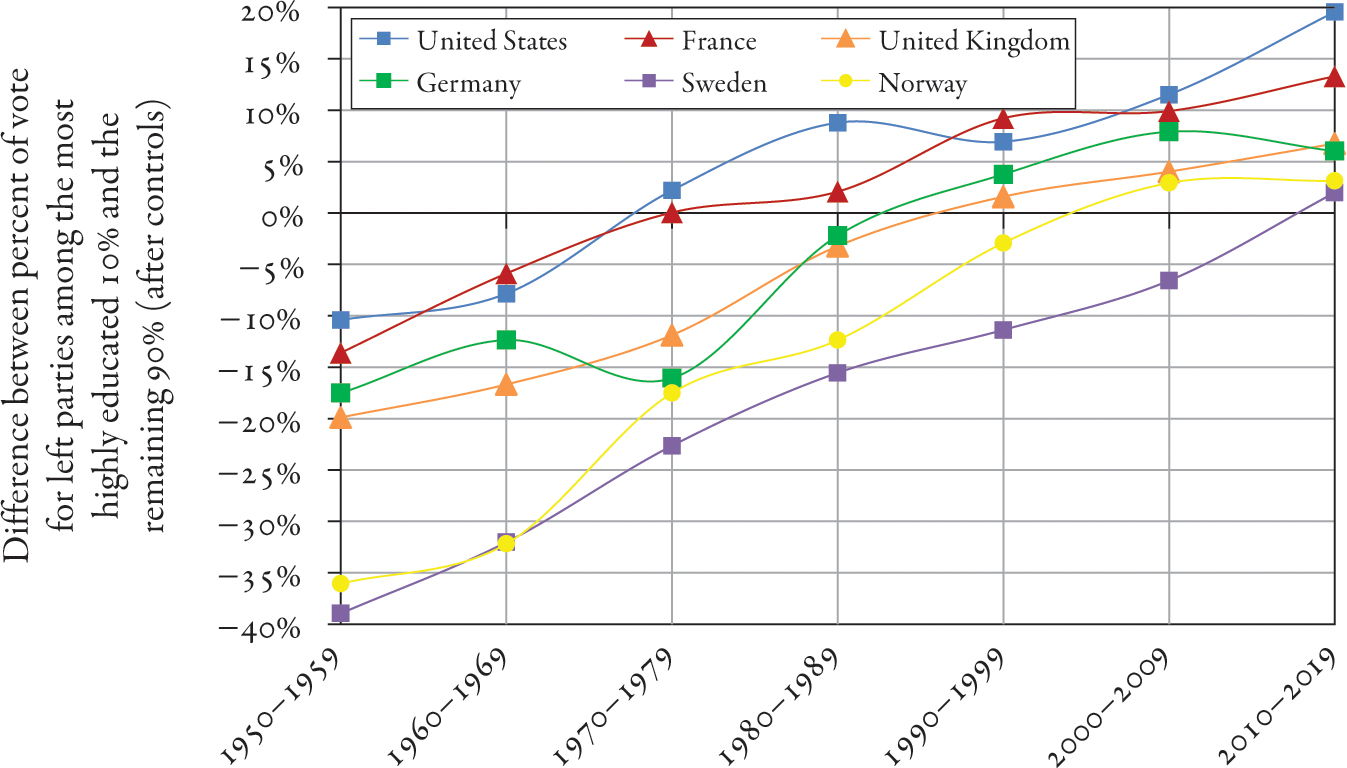

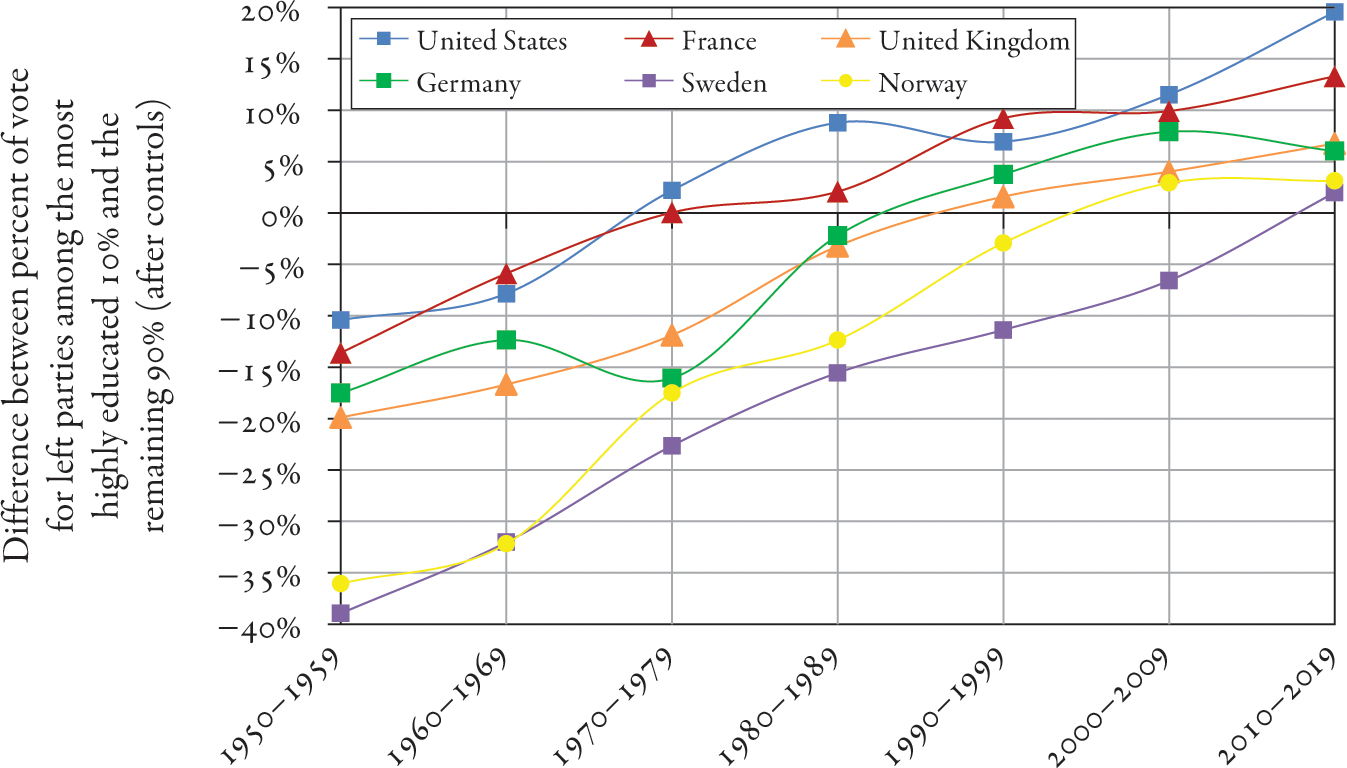

In regard to Western democracies, the principal conclusion is that the results obtained for the United Kingdom, United States, and France are representative of a much more general evolution. First, we find that the reversal of the educational cleavage took place not only in the three countries already studied but also in the Germanic and Nordic countries that constitute the historic heart of social democracy: Germany, Sweden, and Norway (Fig. 16.1). In all three countries, the political coalition associated with the workers’ party in the postwar decades (which did particularly well among more modest voters) became the party of the educated in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, achieving its highest scores among those who obtained higher degrees.

In Germany, for example, we find that, in the period 1990–2020, the vote for the Social Democratic Party (SPD) and other parties of the left (especially Die Grünen and Die Linke) was five to ten points higher among highly educated voters than among the less educated, whereas it was around fifteen points lower in the period 1950–1980. To make the results as comparable as possible across time and space, I will focus here on the difference between the vote of the 10 percent most diplomaed voters and the 90 percent least diplomaed (after controlling for other variables). Note, however, that as in the French, American, and British cases, the trends are similar if one compares voters with and without college degrees or the 50 percent most educated with the 50 percent least educated, both before and after controlling for other variables.1 In the case of Germany, note that the amplitude of the reversal of the educational cleavage is almost identical to that observed in the United Kingdom (Fig. 16.1). Note, too, the role played by the emergence of the Greens (Die Grünen) in shaping the German trajectory. From the 1980s on, the ecological party has attracted a substantial share of highly educated voters. Yet one still sees a reversal of the educational cleavage (though less pronounced at the end of the period) if one focuses exclusively on the SPD vote.2 Broadly speaking, although the institutional structure of parties and factions varies widely from country to country as we saw in comparing France with the United States and United Kingdom, it is striking to see how limited the effect of these differences is on the basic trends that interest us here.

FIG. 16.1. The reversal of the educational cleavage, 1950–2020: United States, France, United Kingdom, Germany, Sweden, and Norway

Interpretation: In the period 1950–1970, the vote for Democrats in the United States and for various left parties in Europe (labor, social-democratic, socialist, communist, radical, and ecologist) was higher among less educated voters; in the period 2000–2020, it was higher among more educated voters. The change came later in Nordic Europe but went in the same direction. Note: “1950–59” includes elections from 1950 to 1959, and “1960–69” includes those from 1960 to 1969, and so on. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

In Sweden and Norway, the politicization of the class cleavage in the postwar period stands out starkly. Specifically, the social-democratic vote among the 10 percent most highly educated voters was on the order of thirty to forty points lower than among the remaining 90 percent in 1950 to 1970. By contrast, this same gap was on the order of fifteen to twenty points in Germany and the United Kingdom and ten to fifteen points in France and the United States (Fig. 16.1). This shows the degree to which the Nordic social-democratic parties were built around an exceptionally strong mobilization of the working class and manual laborers.3 This mobilization was necessary, moreover, to overcome the particularly extreme proprietarian inequality that persisted into the twentieth century (particularly in Sweden, where the electoral system weighted votes in proportion to wealth); it led to the establishment of unusually egalitarian societies in the postwar period.4 Nevertheless, both in Sweden and Norway we find an erosion of this electoral base, which begins in the 1970s and continues throughout the period 1990–2020. Less educated voters little by little withdrew their confidence from the social democrats, which by the end of the period were racking up their highest scores among the highly educated. To be sure, compared with what we see in the United States and France and to a lesser degree in the United Kingdom and Germany, the social-democratic vote did hold up better among the disadvantaged classes in Sweden and Norway. But the basic tendency, which has been under way now in all countries for more than half a century, is clearly the same.

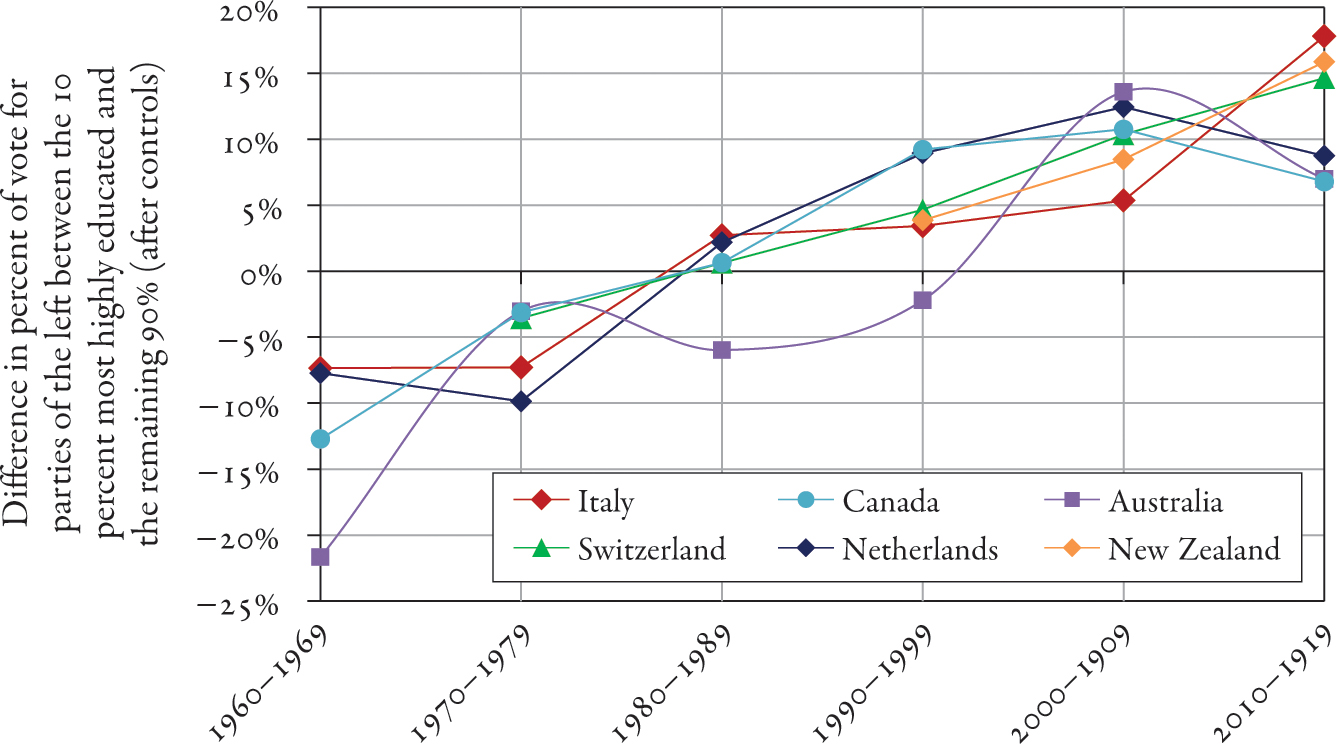

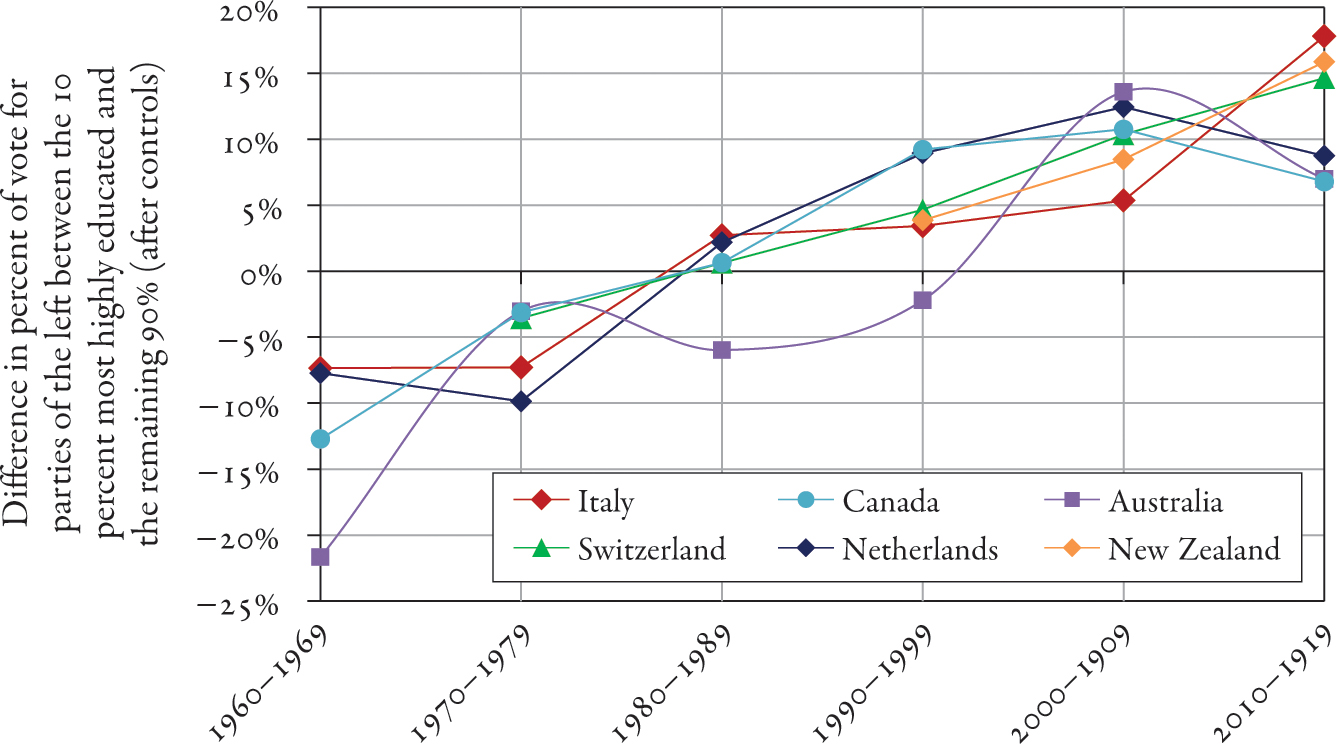

The postelection surveys available in each country do not always allow us to go all the way back to the 1950s. The types of survey that were conducted and the state of the surviving records are such that in many cases we cannot begin systematic comparison until the 1960s or even the 1970s or 1980s. The sources we have gathered nevertheless allow us to conclude that the reversal of the electoral cleavage is an extremely general phenomenon in Western democracies. In nearly all the countries studied, we find that the vote profile of left-wing parties (labor, social-democratic, socialist, communist, radical, and so on, depending on the country) has reversed over the past half century. In the period 1950–1980, the profile was decreasing with educational level: the more educated the voter, the less likely he or she was to vote for the parties of the left. This gradually turned around in the period 1990–2020: the more highly educated the voter, the more likely to vote for the parties of the left (whose identity had clearly changed in the meantime)—increasingly so as time went by. We find this same evolution in countries as different as Italy, the Netherlands, and Switzerland as well as Australia, Canada, and New Zealand (Fig. 16.2).5 When the questionnaires and surveys allow, we also find results comparable with those obtained for France, the United States, and the United Kingdom regarding the evolution of the vote profile as a function of income and wealth.6

Within this general scheme, several countries exhibit distinct variations owing to their socioeconomic and political-ideological configurations. These specific trajectories deserve more detailed analysis, which would take us far beyond the scope of this book.7 I will say more later, however, about Italy, a textbook case of advanced decomposition of a postwar party system leading to the emergence of a social-nativist ideology.

FIG. 16.2. Political cleavage and education, 1960–2020: Italy, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand

Interpretation: In the period 1950–1970, the vote for Democrats in the United States and for various left parties in Europe (labor, social-democratic, socialist, communist, radical, and ecologist) was higher among less educated voters; in the period 2000–2020, it was higher among more educated voters. We find the same result in the United States and Europe, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. Note: “1960–1969” includes elections between 1960 and 1969, “1970–1979” includes elections between 1970 and 1979, and so on. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

The only real exception to this general evolution of the cleavage structure of electoral democracy in the developed countries is Japan, which never developed a classist party system of the sort observed in the Western countries after World War II. In Japan, the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) has held power almost continuously since 1945. Historically, this quasi-hegemonic conservative party has done best among rural farm voters and the urban bourgeoisie. By placing postwar reconstruction at the center of its program, it bridged the gap between the economic and industrial elite and traditional Japanese society. It was a complicated moment, marked by the US occupation and extreme anticommunism induced by the proximity of Russia and China. By contrast, the Democratic Party usually did best among modest-to-middling urban wage-earners together with more highly educated voters, who were eager to contest the US presence and the new moral and social order represented by the LDP. It was never able to constitute an alternative majority, however.8 More generally, the specific structure of Japanese political conflict should be seen in relation to long-standing cleavages around nationalism and traditional values.9

Rethinking the Collapse of the Left-Right Party System of the Postwar Era

To recapitulate: Compared with the very high concentration of income and wealth observed in the nineteenth century and until 1914, income and wealth inequality fell to historically low levels in the period 1950–1980. This was due in part to the shocks and devastation of the period 1914–1945, but a more important cause of change was the far-reaching critique to which the dominant proprietarian ideology of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was subjected. Between 1950 and 1980, new institutions and social and fiscal policies were created for the express purpose of reducing inequality: these included mixed public-private ownership, social insurance, progressive taxes, and so on.10 During this period, the political systems of all the Western democracies were structured around a “classist” conflict between left and right, and political debate centered on redistribution. The social-democratic parties (broadly understood to include the Democratic Party in the United States and various coalitions of social-democratic, labor, socialist, and communist parties in Europe) drew their support mainly from the socially disadvantaged classes, while the parties of the right and center-right (including the Republicans in the United States and various Christian-democratic, conservative, and conservative-liberal parties in Europe) drew their support mainly from the socially advantaged. This was true regardless of which dimension of social stratification—income, education, or wealth—one looked at. This classist structure of political conflict became so widespread in the postwar decades that many people came to believe that no other form of political organization was possible and that any deviation from this norm could only be a temporary anomaly. In reality, this classist left-right structure reflected a particular historical moment and was the product of specific socioeconomic and political-ideological conditions.

In all the countries studied, this left-right system has gradually broken down over the past half century. In some cases the names of the parties have remained the same, as in the United States, where the labels “Democrat” and “Republican” endure despite their countless metamorphoses. Elsewhere, parties have sometime updated their nomenclature, as in France and Italy in recent decades. But whether the names have changed or remained the same, the structure of political conflict in the Western democracies in 1990–2020 no longer has much to do with that of the period 1950–1980. In the postwar period, the electoral left was everywhere the workers’ party, but in recent decades it has become the party of the educated (the “Brahmin left”): the more educated the voter, the more likely to vote for the left. In all the countries studied, less educated voters have little by little ceased to vote for the parties of the left, leading to a complete reversal of the educational cleavage; the same voters have sharply reduced their participation in the political process.11 When a divorce of such magnitude occurs in so many countries as the result of a long-term process extending over six decades, it is clear that something real is happening and that this cannot be attributed to some unfortunate misunderstanding.

The decomposition of the postwar left-right system and in particular the fact that the disadvantaged classes gradually withdrew their confidence from the parties to which they had given their support in the period 1950–1980 can be explained by the fact that those parties failed to adapt their ideologies and platforms to the new socioeconomic challenges of the past half century. Two of those challenges stand out: the expansion of education and the rise of a global economy. With the unprecedented growth of higher education, little by little the electoral left became the party of the highly educated (the “Brahmin left”) while the electoral right remained the party of the highly paid and wealthy (the “merchant right”), though less so over time. As a result, the social and fiscal policies of the two coalitions have converged. Furthermore, as commercial, financial, and cultural exchanges began to develop on a global scale, many countries experienced the pressure of heightened social and fiscal competition, which benefited those with the most educational capital on the one hand and the most financial capital on the other. Yet the social-democratic parties (in the broadest sense of the term) never really revised their redistributive thinking so as to transcend the limits of the nation-state and meet the challenges of the global economy. In a sense, they never responded to the critique Hannah Arendt proposed in 1951 when she observed that to regulate the unbridled forces of global capitalism, new forms of transnational politics would need to be developed.12 Instead, the social-democratic parties contributed in the 1980s–1990s to liberalize the flow of capital everywhere without regulation, compulsory information sharing, or common fiscal policy (even on the European level).13

Other important factors explaining the decomposition of the postwar party system include the end of the old colonial empires; the growth of trade and increasing competition between the old industrial powers and the poor but developing countries where labor was cheap; and finally, the influx of immigrants from the former colonies. Taken together, these factors contributed in recent decades to the emergence of unprecedented identitarian and ethno-religious political cleavages, especially in Europe. New anti-immigrant parties arose on the right while existing parties (such as the Republicans in the United States, the Conservatives in the United Kingdom, and various traditional right-wing parties on the continent) took a tougher line on immigration-related issues. Two points should be noted, however. First, the decomposition of the classist left-right structure of the postwar period unfolded very gradually; it began in the 1960s, well before the immigration cleavage became salient in most Western countries (which generally did not happen until the 1980s and 1990s and in some cases even later). Second, when we look at the various Western countries, what stands out is that, over the past half century, the reversal of the educational cleavage proceeded nearly everywhere at the same pace and without apparent relation to the magnitude of cleavages over race or immigration (Figs. 16.1–16.2).

In other words, while it is clear that anti-immigrant parties (and anti-immigrant factions within older parties) have exploited identity cleavages in recent decades, it is just as clear that the reversal began for other reasons. A more satisfactory explanation is that the disadvantaged classes felt abandoned by the social-democratic parties (in the broadest sense) and that this sense of abandonment provided fertile ground for anti-immigrant rhetoric and nativist ideologies to take root. As long as the absence of redistributive ambition responsible for this sense of abandonment remains uncorrected, it is hard to see what might prevent that fertile ground from being exploited further.

Finally, an additional reason for the collapse of the left-right system of the postwar era is undoubtedly the fall of Soviet Communism and the ensuing shift in the political-ideological balance of power. For many years the mere existence of a communist countermodel put pressure on capitalist elites and political parties that had long been hostile to redistribution. But it also limited the redistributive ambitions of the social-democratic parties, which were de facto integrated into the anticommunist camp and therefore felt little incentive to seek an internationalist socialist alternative to capitalism and private ownership of the means of production. Indeed, the collapse of the communist countermodel in 1990–1991 convinced many political actors, especially among social democrats, that redistributive ambition had become superfluous. Markets, they now believed, were self-regulating, and the new goal of political action was to extend them as far as possible, both within Europe and around the world. The 1980s and 1990s were the crucial years when many key measures were decided, beginning with the complete liberalization of capital flows (without regulation). This effort was to a large extent led by social-democratic governments, and social-democratic parties remain unable even today to perceive alternatives to the situation they themselves created.

The Emergence of Social Nativism in Postcommunist Eastern Europe

The case of Eastern Europe clearly illustrates the role played by postcommunist disillusionment and the ideology of competitive markets in the collapse of the postwar party system (based on a clear left-right cleavage). In the transition to democracy following the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe, former ruling parties transformed themselves into social-democratic parties, in some cases fusing with newly emerged political movements and in others splintering and then recombining with them. Although much of the public remained hostile to the old parties (for understandable reasons related to their past errors), former state bureaucrats and managers of state enterprises affiliated with those parties often exercised important responsibilities in the early stages of the transition.

Consider, for example, the Democratic Left Alliance (SLD), which held power in Poland from 1993 to 1997 and again from 2001 to 2005. Eager to forget the communist past and join the European Union, the SLD adopted a platform that was social-democratic in name only. Its first priority was to privatize firms and open Polish markets to competition and investment from Western Europe, thus forcing the country to meet the criteria for EU admission as rapidly as possible. To attract capital, and in the absence of the slightest fiscal harmonization at the European level, a number of East European countries, including Poland, also set very low tax rates on corporate profits and high incomes in the 1990s and early 2000s.

Yet when the postcommunist transition was complete and Poland finally joined the European Union, the results did not always live up to expectations. Income inequality increased sharply, and large segments of the population felt left behind. German and French investments often generated large profits for shareholders while promised raises for wage-earners failed to materialize. This fostered strong resentment of the dominant powers within the EU, which were always quick to remind the Poles of the generous transfers of public funds they had received while forgetting that the reverse flow of private profits out of Poland (and other East European countries) significantly exceeded the influx of public transfers.14 In addition, since the 1990s, political life in Eastern Europe has been scarred by a large number of financial scandals, often linked to privatizations and involving individuals close to the party in power. Several corruption cases (such as the Rywin Affair in Poland in 2002–2004) revealed alleged links between the media and political and economic elites.15

Such was the deleterious climate in which the SLD went down to defeat in the 2005 Polish elections, in which the party received barely 10 percent of the vote and the “left” was virtually wiped off the political map. Since then, political conflict in Poland has revolved around the conservative liberals of the Civic Platform (PO) on one side and the conservative nationalists of the Law and Justice Party (PiS) on the other. It is striking to see how the electorates of these two parties have evolved along classist lines since the early 2000s. In the elections of 2007, 2011, and 2015, the conservative liberals of Civic Platform did best among highly paid and highly educated voters while the conservative nationalists of PiS appealed mainly to the less well paid and less educated. SLD voters occupy an intermediate position, although the party scarcely registers in the current political lineup.16 Their income is slightly below average, and their educational level slightly above, but the cleavage is smaller than with either the PO or PiS (Figs. 16.3–16.4).17

FIG. 16.3. Political conflict and income in Poland, 2001–2015

Interpretation: Between 2001 and 2015, the PO (Civic Platform) (conservative liberal) vote shifted toward higher income groups, whereas the PiS (Law and Justice) (conservative nationalist) vote shifted toward lower-income voters. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

In Brussels, Paris, and Berlin, officials often worry that PiS seems hostile to the EU which PiS party leaders frequently accuse of treating Poland like a second-class partner. By contrast, Eurocrats love PO because it is always quick to endorse EU decisions and rules and religiously adheres to the principle of “free and undistorted competition.” PiS is rightly accused of championing authoritarian government and traditional values: for instance, it vehemently opposes abortion and same-sex marriage.18 Note, however, that since PiS came to power in 2015, it has also enacted fiscal and social measures to help people of low income, including a sharp increase of family benefits and pension hikes for the poorest retirees. By contrast, PO, in power from 2005 to 2015, generally preferred policies that favored the well-to-do. In short, PiS has been readier to flout budget rules than PO and more willing to spend on social programs.

FIG. 16.4. Political conflict and education in Poland, 2001–2015

Interpretation: Between 2001 and 2015, the PO (Civic Platform) (conservative liberal) vote shifted toward more highly educated groups, while the PiS (Law and Justice) (conservative nationalist) vote shifted toward the less educated. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

Thus, PiS developed an ideology that one might characterize as “social-nationalist” or “social-nativist,” offering redistributive social and fiscal measures together with an intransigent defense of Polish national identity (deemed to be under threat from unpatriotic elites). The issue of immigration from outside Europe took on new importance in the wake of the refugee crisis of 2015, which provided PiS with an opportunity to voice its vigorous opposition to an EU plan to relocate immigrants throughout Europe (a plan that was quickly abandoned).19 Note, however, that the classist structure of the PO and PiS electorates was already in place before the issue of immigration really figured on the political agenda.

Unfortunately, it is not possible at this stage to systematically compare the evolution of the electoral cleavage structure in the various countries of Eastern Europe since the postcommunist transition of the 1990s owing to the inadequacy of the available postelection surveys.20 Circumstances varied widely from country to country, and there was rapid turnover of political movements and ideologies. Social nativism has been spreading, with a mixture of strong hostility to non-European immigration (which has become the symbol of what the much-reviled Brussels elites would like to surreptitiously impose, despite the fact that the actual numbers of refugees are extremely small compared with the European population) and with a variety of social policies intended to show that the social-nativist parties care more about the lower and middle classes than do the pro-European parties.

The Hungarian case is in some ways similar to the Polish. Since 2010 the country has been governed by the conservative nationalist party Fidesz and its leader Victor Orban, who has without a doubt become one of the most prominent proponents of social-nativist ideology in Europe. Although officially a member of the European Peoples’ Party, the same parliamentary group to which the German Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and other “center-right” parties belong, Orban did not hesitate to plaster his country with provocative anti-refugee posters in 2015 along with giant billboards denouncing the alleged nefarious influence of George Soros, a Hungarian-born billionaire said to symbolize a conspiracy of globalized Jewish elites against the peoples of Europe. For the “social” component of its program, Fidesz (like PiS) increased family benefits, which for obvious reasons served as a symbol of social nativism.21 The Hungarian government also created subsidized jobs aimed at putting the unemployed back to work under the control of local governments and mayors loyal to the ruling party. Fidesz also sought to encourage Hungarian entrepreneurs and companies by offering government contracts in exchange for political fealty. These measures demonstrated Fidesz’s readiness to resist EU budget and competition rules, in contrast to its political rivals, especially the social democrats, who were regularly accused of marching to orders from Brussels.22

It is worth recalling the circumstances in which Fidesz came to power in 2010. In 2006 (as in 2002), the social-democratic Hungarian Socialist Party, or MSZP (a direct descendant of the Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party, or MSZMP, which had ruled from 1956 to 1989 and then been reorganized as the MSZP in 1990) won a narrow victory over a coalition led by Fidesz, whose popularity was rapidly increasing. The social-democratic leader—Ferenc Gyurcsany, who served as prime minister of Hungary from 2004 to 2009—was also an entrepreneur and one of the wealthiest men in the country, having amassed a fortune out of the privatizations of the 1990s. Shortly after his reelection in 2006, he gave a speech to party leaders that was supposed to remain confidential but somehow leaked to the media. In it, Gyurcsany candidly explained how he had lied for months to secure his victory, in particular concealing from voters planned budget cuts, which he regarded as inevitable. Social spending was to be slashed and the health care system overhauled. The news came as a bombshell; an unprecedented wave of demonstrations ensued. Orban saw the scandal as the long-awaited proof of the social democrats’ shameless hypocrisy and shrewdly exploited the chaos. For Fidesz, which began as a conservative nationalist movement, the situation provided a perfect opportunity to demonstrate that it was more sincerely devoted to the disadvantaged than the so-called social democrats, who had in reality become pro-market elitist liberals. Gyurcsany was ultimately forced to resign in 2009 in circumstances further complicated by the financial crisis of 2008 and the imposition of budgetary austerity throughout Europe. This sequence culminated in 2010 with the ultimate collapse of the social democrats and the triumph of Fidesz, which then easily won the legislative elections of 2014 and 2018.23

The Emergence of Social Nativism: The Italian Case

It would be quite wrong to think of the development of social nativism as a specifically East European phenomenon without implications for Western Europe or the rest of the world. Eastern Europe should rather be seen as a laboratory where conditions were perfect for the combination of two ingredients that we also find in only slightly less extreme forms elsewhere. Together, these two factors give rise to social nativism: first, a strong sense of postcommunist and anti-universalist disillusionment leading to extreme identitarian withdrawal, and second, a global (or European) economy that prevents the establishment of coordinated, effective, and nonviolent policies of social redistribution and inequality reduction. In this light, it is particularly instructive to look at how a social-nativist coalition was formed in Italy after the legislative elections of 2018.

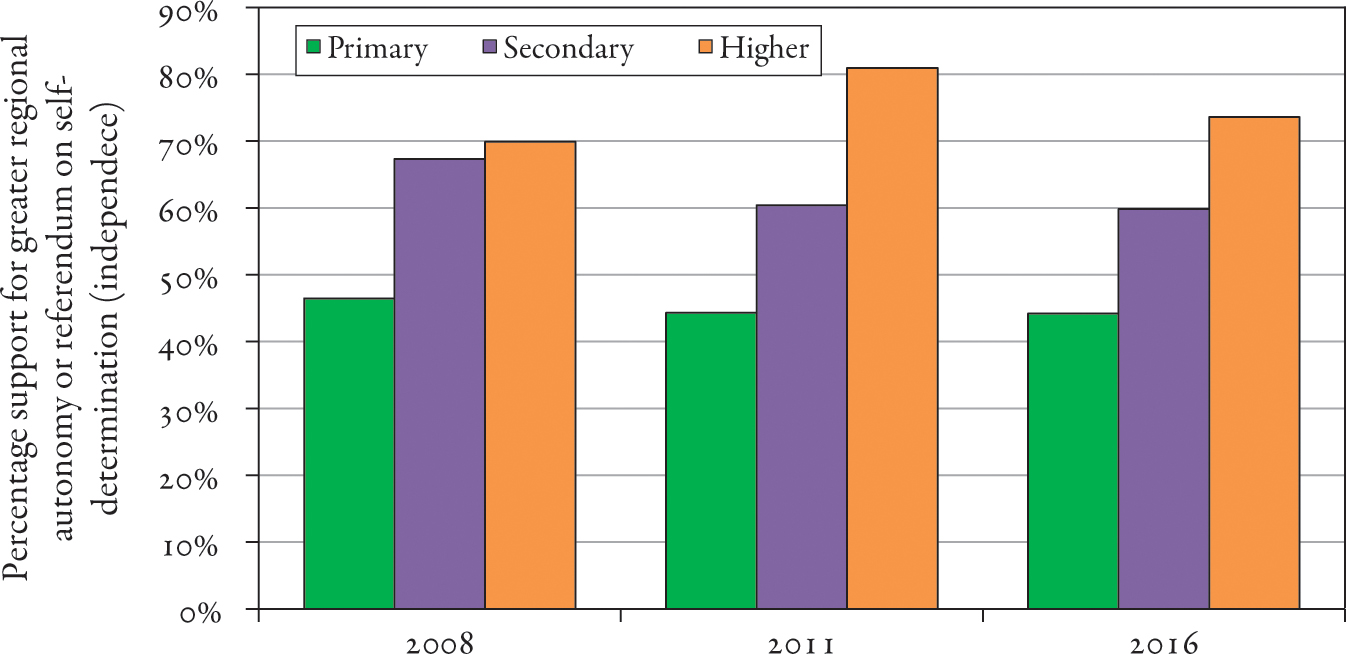

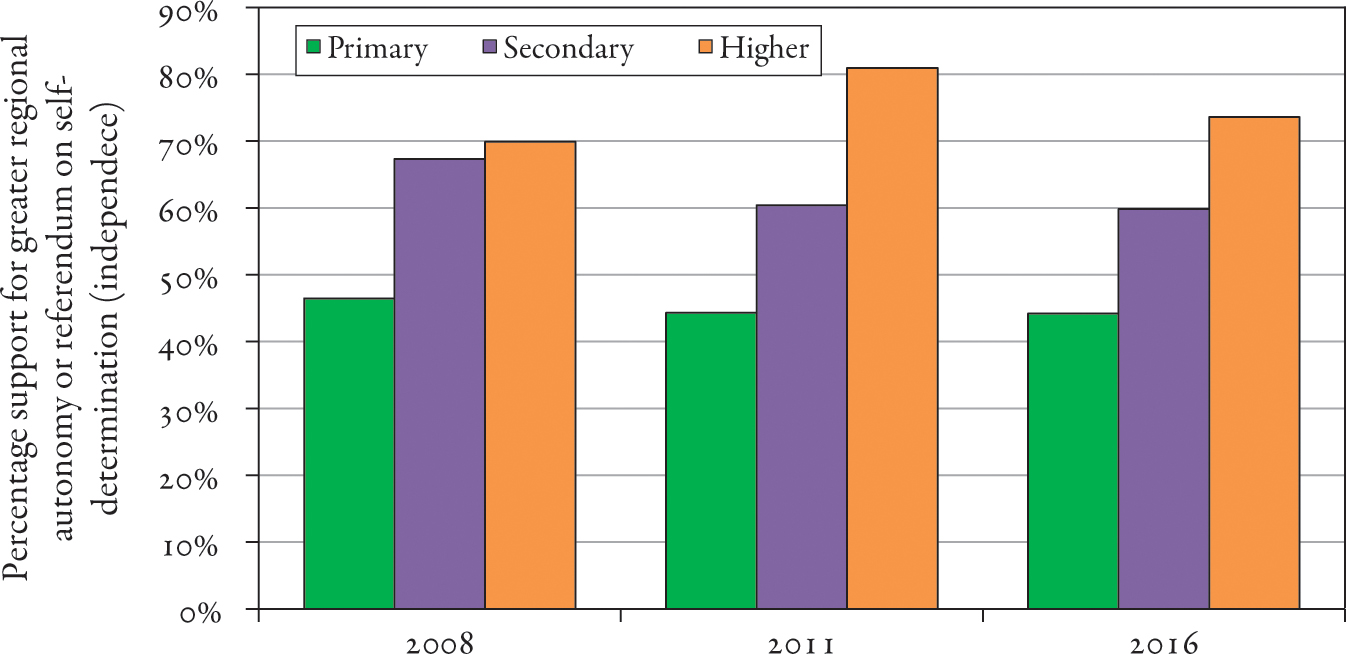

Compared with other Western democracies, Italy is distinctive in several ways. For one thing, the Italian postwar party system imploded in the wake of financial scandals unearthed by the anti-Mafia judges who conducted the Mani Pulite (Clean Hands) investigation in 1992. This led to the downfall of the two parties that had dominated Italian politics since 1945: the Christian Democrats and the Socialists. On the right of the political spectrum, the Christian Democrats were replaced in the 1990s by a complex and changing set of parties, including Silvio Berlusconi’s conservative-liberal Forza Italia and the Lega Nord (Northern League). The Lega was initially a regionalist antitax party, which advocated fiscal autonomy for “Padania” (northern Italy) and opposed transfer payments to the south, a region deemed to be lazy and corrupt. Since the refugee crisis of 2015, the Lega has become a nationalist anti-immigrant party devoted to ridding the country of foreigners. Lega leaders regularly denounce the alleged invasion of Italy by blacks and Muslims, who they claim threaten to take over the peninsula. The party appeals to anti-immigrant voters among the least favored classes, especially in the north, where it has also retained a base of antitax voters from the ranks of management and the self-employed.

On the left the situation is no less complicated. The collapse of the Socialist Party in 1992 and its ultimate dissolution in 1994 inaugurated a cycle of political realignment and renewal. The Italian Communist Party (PCI), long the most powerful in Europe along with its French counterpart, was hard-hit by the fall of the Soviet Union and chose in 1991 to transform itself into the Democratic Left Party (PDS). The PDS then joined other movements to create the Democratic Party (PD) in 2007, with the ambition of unifying “the left,” like the Democratic Party in the United States. In 2013, the party organized an internal election to choose its new leader. The winner, Matteo Renzi, became prime minister in 2014 and served in that post until 2016 as the head of a coalition led by the PD.

What happened on the left went beyond name changes. The left electorate (Socialist Party, or PS; PCI; PDS; PD) has been totally transformed in recent decades. In the 1960s and 1970s these parties racked up their highest scores among the disadvantaged classes, but that is no longer the case. In the 1980s and 1990s, the PS and PCI (and later the PDS) obtained their best results among the highly educated. This trend continued in the 2000s and 2010s. In the 2013 and 2018 elections, the vote for the PD was twenty points higher among the highly educated than among the rest of the population.24 The PD’s policies, especially the loosening of restrictions on layoffs (“Jobs Act”) enacted by Renzi soon after he took power, provoked strong opposition from the unions and huge demonstrations (a million people took to the streets of Rome in October 2014), which made the party even less popular among workers. Renzi’s reforms received strong public support from Christian Democratic German Chancellor Angela Merkel, and they would not have been approved by the Italian parliament had the PD not entered into a de facto coalition with Forza Italia. These developments convinced many Italian that the PD no longer had much to do with the postwar Socialist and Communist Parties that figured in its pedigree.

The latest arrival on the Italian political scene was the Movimento Cinque Stelle (or Five-Star Movement—M5S). Founded in 2009 by the humorist Beppe Grillo, M5S portrays itself an antisystem, antielitist party that cannot be placed on the usual left-right spectrum. One of its signature issues is a universal basic income. Compared with the PD, the M5S runs up its highest scores among less educated voters, among the disadvantaged classes in the south, and among the disillusioned of all the other parties, who are drawn to the movement’s promises to spend more on social measures and develop neglected regions. Within a few years, M5S had capitalized on discontent with the former governing parties, starting with Forza Italia and the PD, and had begun winning a quarter to a third of the vote in each new election.

In the legislative elections of 2018, the electorate divided into three large blocs: M5S got 33 percent of the vote, the PD 23 percent, and a coalition of right-wing parties 37 percent.25 The right-wing coalition was quite heterogeneous because it included the anti-immigrant Lega (17 percent), the conservative-liberal Forza Italia (14 percent), and a number of smaller conservative nationalist parties (6 percent). Since no single bloc obtained a majority of the seats, a coalition was necessary to form a government. An M5S-PD alliance was briefly considered, but mutual suspicion made this impossible. M5S and the Lega, which had already joined forces to oppose Renzi’s Jobs Act both in parliament and in the streets in 2014, ultimately reached an agreement to govern the country on the basis of a synthesis of their two platforms, including both the guaranteed minimum income advocated by M5S and the uncompromising anti-refugee policy championed by the Lega.26 The heterogeneous nature of this coalition agreement is reflected in the structure of the government: Luigi di Maio, the young leader of M5S, became the minister of economic development, labor, and social policy, which is responsible for overseeing the minimum income, territorial development, and public investment in the south while Matteo Salvini, the leader of the Lega, occupies the strategic post of minister of the interior, from which in the summer of 2018 he launched several spectacular anti-immigration operations, including closing all Italian ports to humanitarian ships engaged in rescuing refugees adrift on the Mediterranean.

The M5S-Lega coalition that has ruled Italy since 2018 is clearly a social-nativist alliance; it naturally calls to mind the PiS government and Poland and the Fidesz government in Hungary. Of course, there is no guarantee that this coalition will survive. Either of the two pillars on which it stands could collapse, bringing down the whole edifice. Relations between the two governing parties are very tense, and all indications are that the nativists are on the verge of emerging as the dominant partner in the coalition. Salvini’s sallies against refugees have made him increasingly popular and may allow the Lega to outstrip M5S in the next elections or even to win an absolute majority. In any case, the mere fact that such a social-nativist coalition could come to power in an old West European democracy like Italy (the third-largest economy in the Eurozone) shows that the phenomenon is not limited to postcommunist Eastern Europe. Social-nativist leaders in several countries, including Orban and Salvini, have not been shy about publicizing their shared antielitist attitudes and common view of Europe’s future in both immigration and social policy.27

On the Social-Nativist Trap and European Disillusionment

It is natural to ask whether a similar political-ideological coalition could emerge in other countries, especially France. This would have significant consequences for the political equilibrium of the European Union. When we look at the distribution of votes in the 2018 Italian elections, we find three voting blocs (or four, if we distinguish between the two components of the right bloc, the Lega and Forza Italia, which split over the question of alliance with M5S). This configuration of Italy’s ideological space has some important points in common with the four-part division we saw in the 2017 French presidential election as well as some significant differences.28 In the French context, the closest equivalent to the M5S-Lega alliance would be a hypothetical alliance between the radical left, La France Insoumise (LFI), and the Front National (which in 2018 renamed itself the Rassemblement National, or RN). At this stage, an LFI-RN alliance seems out of the question, however. The RN electorate includes voters most fiercely opposed to immigration while the LFI electorate (on the evidence of 2017) includes the voters most favorable to immigration.29 The social and redistributive policies favored by LFI voters and party leaders, such as progressive taxation, are directly descended from the historical policies of the socialist and communist left. The RN draws on a very different ideological corpus, which makes it hard to imagine any way that the two parties could agree on a common plan of action, at least in the near future. Despite many attempts to win respectability and bury its historic origins (in Vichy, colonialism, and Poujadism), even to the point of changing its name, the RN remains the heir of a movement that the vast majority of LFI voters regard as untouchable.30

Nevertheless, the rapidity of change in Italy suggests a need for caution in anticipating what trajectories might be possible in the medium term. Several things made the social-nativist alliance of 2018 possible in Italy. One was the damage done by the collapse of the postwar party system in 1992. As the integrity of all the postwar parties was called into question, people lost faith in the old faces and promises to the point where they could no longer find their political bearings. Ideologies that had once seemed solid shattered into a thousand pieces, and previously unthinkable alliances became acceptable.31

One reason why the social-nativist cocktail became thinkable in Italy has to do with specific features of the Italian immigration controversy. Because of its geographical situation, Italy became the destination of choice for large numbers of refugees fleeing Syria and Africa via Libya.32 The other countries of Europe, always prompt to lecture the rest of the world—including Italy—on the need for generosity, mostly refused to consider any plan to apportion responsibility for the refugees in a rational and humane way. France showed itself to be particularly hypocritical on this score: French border police were ordered to turn back any immigrants attempting to cross from Italy. Since 2015, France has admitted only one-tenth as many refugees as Germany.33 In the fall of 2018, the French government decided to close its ports to the humanitarian vessels turned away by Italy, and it went so far as to refuse to allow the Aquarius to sail under a French flag, condemning the ship chartered by the humanitarian organization SOS Méditerranée to remain tied up in port while refugees drowned at sea. Salvini had a field day attacking the attitude of France and particularly its young president Emmanuel Macron, elected in 2017, who in Salvini’s eyes was the very embodiment of Europe’s hypocritical elite. French hypocrisy thus became his justification for cracking down on immigrants in Italy.

The charge of hypocrisy is of course one of the classic rhetorical devices of the anti-immigrant right. The Front National and other parties of its ilk have always denounced the self-righteousness of elites quick to defend open borders as long as they do not have to bear the consequences.34 But rhetoric of this type (pioneered in France by Jean-Marie Le Pen in the 1980s) is usually convincing only to those who already believe because it is clear that those who use it are interested mostly in stirring up hatred as a stepping stone to power for themselves. In Salvini’s case, in the context of a Europe-wide conflict over immigration with a particularly bitter clash between France and Italy, the charge of hypocrisy has acquired a certain plausibility. The specific nature of this conflict is part of the reason for the Lega’s growing popularity in Italy. It also helps to explain why the M5S, although relatively moderate on the refugee issue, could agree to a coalition with the Lega: the tough anti-immigrant line could be presented as part of a broader attack on elite hypocrisy.

Last but perhaps not least, the social-nativist coalition in Italy is fueled by a widespread distaste for European rules and in particular European budgetary rules, which allegedly prevented Italy from investing and from recovering from the 2008 crisis and the purge that followed. Indeed, it is hard to deny that the European decision, pushed by Germany and France in 2011–2012, to impose deficit reduction throughout the Eurozone led to a disastrous “double-dip” recession and a sharp spike in unemployment, especially in the south.35 It is also clear that Franco-German conservatism on the issue of pooling public debt and establishing a common interest rate at the European level—a policy change that would be consistent with having a common concurrency and would protect the countries of the south from speculation in the financial markets—is due largely to the fact that France and Germany would prefer to continue enjoying the benefits of near-zero interest rates by themselves, even if it means leaving the European project at the mercy of the markets in any future financial crisis.

Of course, the alternatives proposed by the Lega and M5S are far from perfect or well thought out. Some in the Lega seem to be contemplating an exit from the euro and return to the lira, which would allow for debt reduction through moderate inflation. The majority of Italians worry about the unpredictable consequences of such a move, however. Most leaders and voters of the Lega and M5S would prefer a change of Eurozone rules and of the policy stance of the European Central Bank (ECB). If the ECB could print trillions of euros to save the banks, people ask, why can’t it help Italy by deferring its debt until better times return? I will say more later about these complex and unprecedented debates, which remain underdeveloped. What is certain is that answers to these questions cannot be postponed indefinitely. Social discontent with the EU and deep incomprehension of the authorities’ inability to muster the same energy and deploy the same resources to help large numbers of people as they did to save the financial sector will not magically disappear.

The Italian case also shows that the sense of disillusionment with Europe, which the Lega shares with M5S, can serve as a powerful bond for a social-nativist coalition. What makes the Lega and its leader Matteo Salvini so dangerous is precisely Salvini’s ability to combine nativist rhetoric with social rhetoric—attacks on immigrants with attacks on speculators and financiers—and to wrap all of it up in a critique of hypocritical elites. A similar formula could be used to build social-nativist coalitions in other countries, including France, where disillusionment with Europe runs high among supporters of both the far left and the far right. The fact that Europe is so often instrumentalized for the pursuit of antisocial policies, as was clear in the sequence of events leading up to the Yellow Vest crisis of 2017–2019 (which followed abolition of the wealth tax in the name of European competition, financed by a carbon tax that fell heavily on the poorer half of the population), unfortunately makes such an evolution plausible. Indeed, if the nativist party opportunistically tones down its anti-immigrant rhetoric and concentrates instead on social issues and resistance to the European Union, it is not out of the question that we could someday see a social-nativist coalition similar to the Lega-M5S coalition in Italy coming to power in France.

The Democratic Party: A Case of Successful Social Nativism?

Some readers, even among those generally hostile to anti-immigrant politics, might nevertheless be tempted to welcome social-nativist movements in Europe. After all, wasn’t the Democratic Party that backed the New Deal in the United States in the 1930s and ultimately supported the civil rights movement in the 1960s and elected a black president in 2008 originally an authentic social-nativist party? Having supported slavery and contemplated sending slaves back to Africa, the Democratic Party reconstructed itself after the Civil War around a social-differentialist ideology, combining very strict segregation in the South with a relatively egalitarian social policy for whites (especially white Italian and Irish immigrants and indeed the white working class generally). In any case, whatever its shortcomings, Democratic social policy was certainly more egalitarian than Republican social policy. Yet it was not until the 1940s that the Democratic Party tried to do something about the segregationist element within it, which it finally purged in the 1960s under pressure from the civil rights movement.

With this example in mind, one might imagine a trajectory in which PiS, Fidesz, the Lega, and the Rassemblement National follow a similar course in the coming decades, offering relatively egalitarian social measures to “native Europeans” combined with a very harsh crackdown on non-European immigrants and their children. Later, perhaps half a century or more in the future, the nativist component would fade away or perhaps even transform itself to the point of embracing diversity once conditions were right. There are several problems with this idea, however. First, before becoming the party of the New Deal and civil rights, the Democratic Party did a great deal of damage. From the 1870s to the 1960s, Democrats in the South imposed segregation on blacks, kept black children from attending the same schools as whites, and supported or covered up lynchings organized by the Ku Klux Klan and similar vigilante groups. It makes no sense to suggest that there was no other path to the New Deal and the Civil Rights Act. There are always alternatives. Everything depends on the ability of political actors to mobilize and search for them.36

In the current European context, the potential damage if social nativists were to take power would likely be of the same order. Indeed, the damage has already begun where social nativists currently hold power: not only have they cracked down on immigrants in their own countries, but they have also pressured timorous governments elsewhere in Europe to enact more restrictive immigration policies. Meanwhile, thousands of migrants die in the Mediterranean and hundreds of thousands molder in camps in Libya and Turkey. If the social-nativist parties were free to do as they wished, they might very well turn to more violent attacks on non-European immigrants and their descendants living in Europe, retroactively stripping them of nationality and deporting them, as purportedly democratic regimes have done in the past in both Europe and the United States.37

What is more, there are serious reasons to doubt that today’s social-nativist movements are capable of enacting genuinely redistributive policies. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the Democratic Party in the United States helped develop tools for social redistribution, including the federal income and inheritance taxes enacted in 1913–1916 and social insurance (pensions and unemployment) and minimum wage programs in the 1930s—and remember that under Democratic leadership the United States led the way in progressive taxation, raising top marginal rates to the highest levels ever seen anywhere in the period 1930–1980.38 Contrast this record with the rhetoric and accomplishments of PiS in Poland, Fidesz in Hungary, and the M5S-Lega alliance in Italy. It is striking to see that none of these parties has proposed any explicit tax increase on the wealthy, even though they sorely need the revenue to finance their social policies. True, PiS did reduce certain tax deductions beneficial to people with high incomes so that they ended up paying somewhat more than before, but the Polish government still has not dared to raise tax rates on the wealthy.39

Interstate Competition and the Rise of Market-Nativist Ideology

In Italy, it is noteworthy and revealing that M5S agreed to include the Lega’s campaign proposal for a “flat tax” (a legacy of the Lega’s origins as an antitax party) in its coalition agreement with Salvini’s party. If this measure were fully implemented, it would mean that every taxpayer, no matter how high his or her income, would pay the same flat rate—thus completely dismantling the progressive tax system. This would result in an enormous loss of tax revenue, the benefits of which would go to people of middle-to-high income but which would be paid for by increased public borrowing, on the model of Ronald Reagan’s tax reforms of the 1980s. Because this would pose a serious problem for a heavily indebted country like Italy, this part of the coalition’s reform program has been postponed and will no doubt be enacted only in some very limited form with a reduction of top marginal rates rather than complete elimination of progressive taxation. Nevertheless, the fact that M5S could have agreed to such a proposal says a great deal about the movement’s lack of ideological backbone. It is hard to see how one can possibly finance an ambitious basic income proposal and a vast program of public investment while eliminating progressive taxes on top incomes.

Why do today’s social nativists lack appetite for progressive taxation? There are several possible explanations. It may be that they do not want to be associated with the legacy of the social-democratic, socialist, Labour (United Kingdom), or New Deal left. M5S has embraced the idea of a universal basic income, which it sees as innovative and modern, but rejects the progressive tax system that could finance it, which it finds complicated and tired. Another point that bears emphasizing is the degree to which the ECB’s policy of massive monetary creation since 2008 has changed people’s perceptions. Because the ECB created trillions of euros to save the banks, it is difficult for social nativists to admit that complex and potentially unjust and evadable new taxes are needed to pay for a universal basic income or new investment in the real economy. One finds repeated references to the need for just monetary creation in the rhetoric of M5S, the Lega, and other social-nativist movements. Until European governments propose a more convincing means of mobilizing resources, such as a European tax on the wealthy, the idea of paying for social expenditures by contracting new debt and creating new money will continue to attract strong support among social-nativist voters.

The lack of appetite for progressive taxes is also a consequence of several decades of antitax propaganda and sanctification of the principle of competition of all against all. Today’s hypercapitalist economy is one of heightened interstate competition. Competition to attract high earners and wealthy capitalists already existed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. But it was less intense than competition today. This was partly because the means of transportation and information technology were different back then. More importantly, the international treaties that have defined the global economy since the 1980s have ensured that the new technology would be used to protect the legal and fiscal privileges of the rich rather than the majority. That technology could be used instead to create a public financial register, which would allow countries that so desire to impose redistributive taxes on transnational wealth and the income it generates. Such a system is not only possible but also desirable: it would replace existing treaties, which allow the capital to circulate freely, with new treaties that would create a regulated system built on the public financial register.40 But this would require substantial international cooperation and ambitious efforts to transcend the nation-state, especially on the part of smaller countries (such as the nations of Europe). Nativist and nationalist parties are by their very nature not well equipped to achieve this kind of cross-border cooperation.

Therefore, it seems quite unlikely that today’s social-nativist movements will develop ambitious plans for progressive taxation and social redistribution. The most probable outcome is that once they arrive in power, they will find themselves (whether they like it or not) caught up in the mechanism of fiscal and social competition and thus be forced to do whatever it takes to promote their national economies. Only for opportunistic reasons did the Rassemblement National in France oppose abolition of the wealth tax during the Yellow Vest crisis. If the RN were to come to power, it would likely cut taxes on the rich to attract new investment, not only because such a course would be in keeping with its old antitax instincts and its ideology of national competition but also because its hostility to international cooperation and a federal Europe would force it to engage in fiscal dumping. More generally, the disintegration of the EU (or just the reinforcement of state power and anti-migrant ideology within the EU) to which the accession of nationalist parties to power could lead would intensify social and fiscal competition, increase inequality, and encourage identitarian retreat.41

On Market-Nativist Ideology and Its Diffusion

In other words, social nativism is highly likely to lead in practice to a market-nativist type of ideology. In the United States, Donald Trump has clearly gone this route. In the 2016 presidential campaign, Trump tried to give his politics a social dimension by portraying himself as the champion of the American worker, whom he described as the victim of unfair competition from Mexico and China and as citizens abandoned by Democratic elites. But the actual policies of the Trump administration have combined more or less standard nativist measures (such as reducing the influx of immigrants, building a border wall, and supporting Brexit and nativist governments in Europe) with tax cuts for the rich and multinational corporations. Reagan’s 1986 Tax Reform Act featured a reduction of the top marginal income tax rate (to 28 percent, later raised to 35–40 percent under George H. W. Bush and Bill Clinton but never restored to previous levels). The tax reform that Trump negotiated with Congress in 2017 pushed this logic even further by focusing cuts on corporations and “entrepreneurs.” The federal corporate tax rate, which had been 35 percent since 1993, was abruptly cut to 21 percent in 2018, with an amnesty on profits repatriated from abroad. This reduced corporate tax receipts by half and very likely triggered a global race to the bottom on corporate taxes, an essential component of public finance.42 On top of that, Trump obtained an additional tax reduction focused specifically on self-employed entrepreneurs (like himself), whose business income will henceforth be taxed at a maximum rate of 29.6 percent, compared with 37 percent on top salaries. The combined impact of these two measures is that the rate at which the wealthiest 0.01 percent of taxpayers (including the 400 richest people in the country) are taxed has for the first time fallen below the rate assessed on people lower down in the top centile or even the top thousandth; top rates are sinking closer and closer to the effective rate paid by the poorest 50 percent.43 Trump also sought complete elimination of the progressive tax on inheritances, but Congress refused to go along with him on that point.

It is particularly striking to note the similarity between the tax reforms enacted by presidents Trump and Macron in 2017. In France, in addition to elimination of the wealth tax (ISF) discussed previously, the new government passed a gradual reduction of the corporate tax from 33 to 25 percent and also cut the tax on dividend and interest income to 30 percent (compared with the 55 percent rate on the highest salaries). The fact that a purportedly nativist government like Trump’s adopted a tax policy similar to that of a supposedly more internationalist government like Macron’s shows that political ideologies and practices have converged to a considerable degree. The rhetoric varies: Trump praises “job creators” while Macron prefers to speak of the “climbers at the head of the rope” (“premiers de cordée”). Ultimately, however, both adhere to an ideology according to which the competition of all against all requires offering ever greater tax cuts to the most mobile taxpayers while the masses are exhorted to honor their new benefactors, who bring innovations and prosperity (while omitting to mention that none of this would exist without public support for education and basic research and private appropriation of public knowledge).

Meanwhile, both the French and US governments risk increasing inequality and contributing to the feeling of the lower and middle classes that they have been left to face the consequences of globalization on their own. Trump tries to win them over by claiming that he is doing a better job than the Democrats of stopping immigration and is far more vigilant when it comes to opposing unfair competition from abroad.44 He cleverly portrays “job creators” as more useful than the Democrats’ intellectual elites when it comes to winning the global economic war the United States is waging against the rest of the planet.45 Trump regularly denounces intellectuals as condescending and hectoring, always ready to follow the latest cultural fad no matter how threatening to American values and society. In particular, he loves to denounce the newfound passion for the climate: the idea of climate change is “a hoax,” he says, invented by scientists, Democrats, and foreigners jealous of American prosperity and greatness.46 Anti-intellectual sentiments have also been mobilized by nativist governments in Europe and India, illustrating the crucial need for more education and for citizen appropriation of scientific knowledge.47

The French president has made the opposite wager. He hopes to hold on to power by branding his opponents as nativists and antiglobalists, betting that a majority of the French believe in tolerance and openness and will therefore vote against the social nativists when the moment of truth arrives (in any case, by then the social nativists will have turned into market nativists a la Trump). At bottom, both ideologies insist that there is no alternative to tax cuts benefiting the rich and that the progressive-nativist cleavage is the only remaining axis along which political conflict can occur.48 Both are based on misleading simplifications and a healthy dose of hypocrisy. Indeed, it is still possible for individual countries to pursue ambitious programs of redistribution, even small countries like those found in Europe.49 If even small states can redistribute, the federal government in the United States has all the power it needs to enforce its fiscal policies—provided it can muster the necessary political will.50 Furthermore, there is nothing to prevent efforts to develop greater international cooperation, especially on tax issues, for the purpose of achieving more equitable and durable economic growth.

On the Possibility of Social Federalism in Europe

The most natural way to escape the social-nativist trap would be to develop social federalism in one form or another. International cooperation and political integration can achieve social justice and redistribute wealth by democratic means. Unfortunately, such a harmonious and nonviolent reform of European institutions is not the most likely outcome. It is probably more realistic to prepare for somewhat chaotic changes ahead: political, social, and financial crises could tear the European Union apart or destroy the Eurozone. Whatever lies ahead, reform is essential. No one envisions a return to autarky, and new treaties will therefore be necessary and, if possible, more satisfactory than the existing ones. Here I will focus on the possibility of social federalism in the European context. The lessons are of more general import, however, partly because European social and fiscal policies can have an important impact on other parts of the world and partly because similar forms of transnational cooperation may be applicable to other regions (such as Africa, Latin America, or the Middle East) as well as to relations between regional organizations.

The European Union is a novel and sophisticated attempt to organize an “ever closer union among the peoples of Europe.” In practice, however, European institutions, established in stages from the Treaty of Rome (1957), which constituted the European Economic Community (EEC), to the Maastricht Treaty (1992) establishing the EU and the Lisbon Treaty (2007), which set current EU rules, have mainly sought to organize a vast market and guarantee free circulation of goods, capital, and workers but not to arrive at a common social or fiscal policy. Recall the basic principles on which these institutions operate.51 Broadly speaking, in order for decisions taken by the European Union, whether regulations, directives, or other legislative acts, to take effect, they must be approved by the two institutions that share legislative power: first, the European Council, which consists of heads of state and government (and which also meets, as the Council of the European Union, at the ministerial level depending on the issue under discussion, so there can be a council of ministers of finance, ministers of agriculture, and so on); and second, the European Parliament, which since 1979 has been elected by universal suffrage and represents the member states on the basis of population (with overrepresentation of smaller states).52 Decisions are prepared and promulgated by the European Commission, which acts as a kind of executive body and European government with a president of the Commission as its head and Commissioners in charge of various domains appointed by the Council, which consists of heads of state and government, and then approved by the Parliament.

Formally, the setup resembles a classic federal parliamentary structure with an executive and two legislative chambers. Two particular features make the EU arrangement very different, however. One is the key role played by the unanimity rule and the other is the fact that the council of ministers is totally unsuited for parliamentary deliberation of a pluralistic, democratic kind.

Recall first that most important decisions require a unanimous vote of the council of ministers. In particular, unanimity is required in all matters relating to taxes, the EU budget, and systems of social protection.53 As for regulation of the internal market, free circulation of goods, capital, and people, and trade agreements with the rest of the world, which are ultimately the matters at the heart of the European project, the rule of “qualified majority voting” applies.54 But once any matter touching on common fiscal, budgetary, or social policy—and especially anything touching on taxation or the public finances of the member states—is at issue, the unanimity rule applies. Concretely, this means that every country has veto power. For instance, if Luxembourg, with a population of half a million or barely a tenth of a percent of the total EU population of 510 million, wants to tax corporate profits at zero percent at the expense of its neighbors, nobody can stop it from doing so. Any country, no matter how small—be it Luxembourg, Ireland, Malta, or Cyprus—can block any tax measure that comes up. Moreover, since the treaties guarantee free circulation of capital with no obligation of fiscal cooperation, conditions are ripe for a race to the bottom. Fiscal dumping is the result, and the beneficiaries are those whose capital is most mobile.

Furthermore, the absence of any common tax or budget is what makes the European Union more of a commercial union or international organization than a true federal government. In the United States or India, the central government also has a bicameral legislature, but it has the power to levy taxes for collective projects. In both cases, federal income, inheritance, and corporate taxes bring in revenues of about 20 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), compared with barely 1 percent for the European Union, which in the absence of any common tax system depends on contributions by member states set by unanimous agreement.

On the Construction of a Transnational Democratic Space

Can this be changed? One possibility would be to allow fiscal and budget issues to be decided by qualified majority vote. Leave aside the fact it would not be easy to persuade the small countries to give up their fiscal veto. It would probably take a coalition of countries exerting very strong pressure on the others and threatening them with significant sanctions. In any case, even if one succeeds in imposing the qualified majority rule on all twenty-eight member states (soon to be twenty-seven if the United Kingdom goes through with Brexit, which as of this writing remains uncertain) or if a smaller group of countries agrees to forge ahead on some other basis, the problem remains that the council of finance ministers (or heads of government) is totally unsuited to the task of developing a true European parliamentary democracy.

The reason is simple: the council is a body consisting of one representative per country. As such, it is designed to pit the (perceived) national interests of member states against one another. In no way does it allow for pluralist deliberation or the construction of a majority based on ideas rather than interests. In the Eurogroup,55 the German finance minister alone represents 83 million citizens, the French finance minister 67 million, the Greek finance minister 11 million, and so on. Under these conditions, it is simply impossible to deliberate tranquilly. The representatives of the large countries cannot allow themselves to be publicly placed in the minority on a fiscal or budgetary matter of importance to the home country. As a result, decisions of the Eurogroup (or of any of the European bodies consisting of ministers or heads of state and government) are almost always unanimous, taken under the cover of consensus following deliberation behind closed doors. In these bodies, none of the usual rules of parliamentary debate apply. For example, there are no procedural rules governing amendments, speaking time, or the manner of voting. It makes no sense that such bodies can decide tax policy for hundreds of millions of people. Since at least the eighteenth century and the age of Atlantic Revolutions we have known that the power to levy taxes is the quintessential parliamentary power. Setting tax rules, deciding who and what can be taxed and how much, requires free and open public debate under the watchful eye of citizens and journalists. All shades of opinion in every country need to be fully represented. By its very nature, a council of finance ministers cannot satisfy these requirements.56 To recapitulate: European institutions, in which ministerial councils currently play the central and dominant role, relegating the European Parliament to a supporting role, were designed to regulate the broad market and conclude intergovernmental agreements; they were not designed to make fiscal and social policy.

A second possibility, which is widely supported by European leaders who favor a federal system, would be to transfer all power to approve new taxes to the European Parliament. Elected by direct universal suffrage, subject to the usual rules of parliamentary debate, and taking decisions by majority vote, the European Parliament is clearly better suited than the ministerial councils to deliberate on new taxes and budgets. Although this is clearly a better option than the first, several difficulties remain. We need to consider all the implications and understand why this option is unlikely to succeed. First, note that one essential step to creating a viable European democracy is to completely rewrite the rules governing the lobbies that currently loom so large in Brussels politicking, whose lack of transparency raises serious problems.57 Second, transferring fiscal sovereignty to the European Parliament would mean that the political institutions of the member states would not be directly represented in the vote on European taxes.58 This would not necessarily be problematic, and such bypassing of national institutions already happens in other contexts, but the point nevertheless calls for careful consideration.

In the United States, the federal budget and taxes, like other federal laws, must be approved by the Congress, whose members are elected for the purpose and do not directly represent the political institutions of the individual states. Bills must be approved in identical terms by both the House of Representatives and the Senate. Seats in the House are apportioned according to the population of each state while two senators from each state (regardless of size) sit in the Senate. This system, in which neither chamber takes priority over the other, is not a model of its kind and frequently leads to deadlock. But it does function, more or less, perhaps because there exists a certain equilibrium among states of different sizes.59 In India there are also two chambers: the Lok Sabha, or House of the People, directly elected by citizens with districts carefully drawn to ensure proportional representation of the population throughout the country and the Rajya Sabha, or Council of States, whose members are elected indirectly by the legislatures of the states and territories of the Indian Union.60 Laws must in principle be approved in identical terms by both chambers, but in case of disagreement it is possible to convene a joint session to agree on a final text, which in practice gives a clear advantage to the Lok Sabha owing to its numerical superiority.61 In addition, when it comes to fiscal and budgetary measures (“money bills”), the Lok Sabha automatically has the last word.

Nothing stands in the way of imagining a similar solution for Europe: the European Parliament could have the last word on European taxes and a European budget financed by those taxes. There are, however, two key differences that render such a solution unsatisfactory. First, it is unlikely that the EU’s twenty-eight member states would agree to delegate fiscal sovereignty, at least initially. Therefore, those states that wish to forge ahead would need to be allowed to constitute a subchamber of the European Parliament. This could happen, but it would mean a fairly sharp break with the remaining member states. Second, and more important, assuming that all twenty-eight countries are in agreement or that some subgroup is prepared to forge ahead, one key difference remains between the European Union and the United States or India: the nation-states of Europe existed as such before the EU. In particular, each member state is free via its own national parliament to ratify or reject international treaties. In addition, these national parliaments—be it the Bundestag in Germany, the Assemblée Nationale in France, or any of the others—have been voting for decades (in some cases since the nineteenth century) on taxes and budgets; over the years, these have grown to considerable proportions, on the order of 30–40 percent of GDP.

With the taxes approved by these national parliaments, Europe’s nation-states were able to implement novel social and educational polices, pioneering an immensely successful new model of development. They achieved the highest standard of living ever attained while limiting inequality (at least compared with the United States and other parts of the world) and providing relatively equal access to health and education. These national parliaments will continue to exist and continue to levy taxes and approve budgets. No one believes that all decisions should be made in Brussels or that EU spending should jump overnight from 1 to 40 percent of GDP, supplanting all national, regional, and local budgets and social insurance programs. Just as the property regime should be decentralized and participatory, the political regime should also be as decentralized as possible and involve actors on all levels.

Building European Parliamentary Sovereignty on National Parliamentary Sovereignty

For these reasons, if one wants to construct a truly transnational democratic space appropriate to Europe as currently constituted, one had better allow some role for national parliaments. One possibility might be to create a European Assembly (EA) composed partly of representatives of participating national parliaments and partly of members of the European Parliament (MEPs). Each participating country would be represented in proportion to its population, and each political party would be represented in its national delegation in proportion to its representation in the home-country parliament or the European Parliament, as the case may be. These questions of apportionment are too complex to be settled here. One proposal that has emerged as a working hypothesis from recent discussions is that the EA should consist of 80 percent members of national parliaments and 20 percent MEPs.62

The advantage of this proposal, which is based on a draft Treaty on the Democratization of Europe (T-Dem),63 is that it can be adopted by countries that wish to do so without modifying existing European treaties. Although it would be best if it were adopted by as many countries as possible—especially Germany, France, Italy, and Spain (which by themselves account for 70 percent of the population and GDP of the Eurozone)—there is nothing to prevent a smaller subset of countries from moving forward to form, say, a Franco-German Assembly or a Franco-Italo-Belgian Assembly.64 In any case, this EA would be granted the power to approve four important common taxes: a tax on corporate profits, a tax on high incomes, a tax on large fortunes, and a carbon tax. To complement these taxes, the Assembly would also vote on a common budget. Assuming tax revenues of, say, 4 percent of GDP, the money could then be apportioned as follows: half would revert to the member states for their own use (for instance, to reduce taxes on the lower and middle classes, which have thus far borne the brunt of European fiscal competition) while the other half would finance research, education, and the transition to renewable sources of energy, with an additional portion set aside to defray the cost of welcoming new immigrants.65 These suggestions are merely meant to be illustrative; obviously it would be up to the EA to set its own priorities and levy taxes accordingly.66

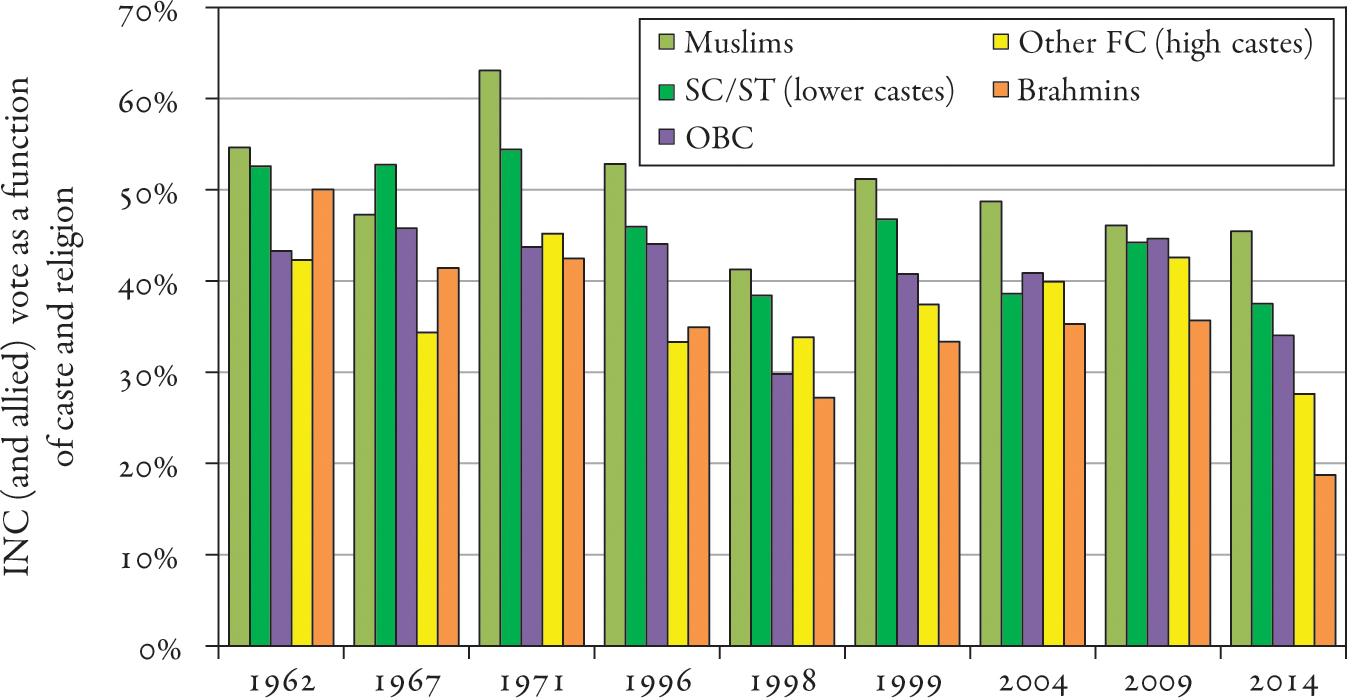

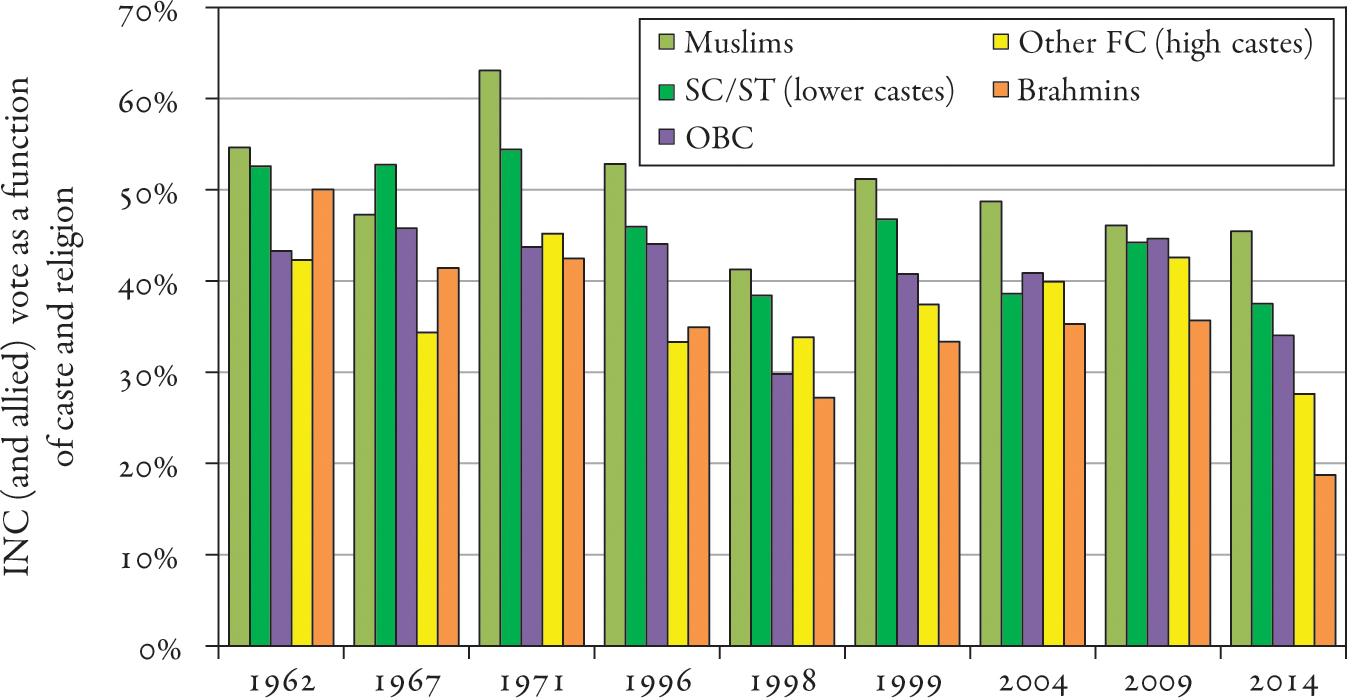

The key point is to create a European space for democratic deliberation and decision making in which it would be possible to adopt strong measures of fiscal, social, and environmental justice. As we saw in analyzing the structure of the French and British referendum votes in 1992, 2005, and 2016, the breach between Europe and the disadvantaged classes has grown to significant proportions.67 Without concrete, visible measures to demonstrate that the European project can be made to serve the goal of greater fiscal and social justice, it is hard to see how this can change.