{ FIFTEEN }

Brahmin Left: New Euro-American Cleavages

In Chapter 14 we studied the transformation of political cleavages in France since World War II. In particular, we saw how the “classist” structure of the period 1950–1980 gradually gave way to a system of multiple elites in the period 1990–2020. At the heart of that system were the party of the highly educated (the “Brahmin left”) and the party of the highly paid and wealthy (the “merchant right”), both of which alternated in power. The very end of the period witnessed an attempt to create a new electoral bloc in France bringing those two elites together; it is too soon to say whether this will last.

To gain a better understanding of the dynamics and possible future developments, in this chapter I turn to the United States and United Kingdom. It is striking to discover how much these two countries, despite everything that differentiates them from France, have since 1945 followed a path broadly similar to the French. Nevertheless, the differences are also important—and revealing. I will continue this comparative approach in Chapter 16, in which I will look at other West and East European democracies along with several non-Western democracies such as India and Brazil. Comparing the different trajectories of all these countries will help us to understand the reasons for the transformations they experienced and what might lie ahead. In particular, I will consider in the final chapter the conditions under which it might be possible to avoid the social-nativist trap. I will also outline a form of social federalism and participatory socialism that could help to confront the new identitarian menace.

The Transformation of the US Party System

We begin with the United States, proceeding as we did for France by examining how the socioeconomic structure of the vote for the Democratic and Republican Parties changed from 1945 to the present. In the US case we have postelection surveys from 1948 on. These surveys allow for a relatively detailed analysis, whose main conclusions I will present here.1 I will focus on the structure of the vote in presidential elections from 1948 to 2016. These are the elections from which the national dimension of political conflict emerges most clearly.2 In most presidential elections in this period the two major parties received between 40 and 60 percent of the vote, and races were usually fairly tight (Fig. 15.1). Third-party candidates usually captured less than 10 percent of the vote, with the exception of the southern segregationist governor of Alabama, George Wallace, who got 14 percent of the vote in 1968 and the businessman Ross Perot, who garnered 20 percent in 1992 and 10 percent in 1996. In what follows I will focus on the Democrat-Republican cleavage and ignore the vote for third-party candidates.

FIG. 15.1. Presidential elections in the United States, 1948–2016

Interpretation: The scores obtained by the candidates of the Democratic and Republican Parties in US presidential elections from 1948 to 2016 generally varied from 40 to 60 percent of the total popular vote. The scores obtained by third-party candidates have usually been low (less than 10 percent of the vote), except for George Wallace in 1968 (14 percent) and H. Ross Perot in 1992 and 1996 (20 and 10 percent). Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

Our first finding is that the educational cleavage has totally reversed. In the 1948 presidential election, the result is quite clear: the more educated the voter, the more likely to vote Republican. Specifically, 62 percent of voters with only a primary education or without a high school diploma, who constituted 63 percent of the US electorate at the time, voted for Harry Truman, the Democratic candidate (Fig. 15.2). Of those with high school diplomas (31 percent of the electorate), Truman scored barely 50 percent. Of those with college degrees (6 percent of the electorate), just over 30 percent voted Democratic, and the score was even lower among those with master’s or higher degrees (more than 70 percent of whom voted for the Republican candidate, Thomas Dewey). Things were not much different in the 1960s: the higher the level of education, the lower the Democratic vote. The educational cleavage begins to flatten out in the 1970s and 1980s, however. Then, from the 1990s on, the higher the level of education, the more likely to vote Democratic, particularly among those with advanced degrees.

FIG. 15.2. Democratic vote by diploma, 1948–2016

Interpretation: In 1948, the Democratic candidate (H. Truman) won 62 percent of the vote among voters with a primary education (no high school diploma) (63 percent of the electorate at the time) and 26 percent of the vote among voters with advanced degrees (1 percent of the electorate at the time). In 2016, the Democratic candidate (H. Clinton) won 45 percent of the vote among those with high school diplomas (59 percent of the electorate) and 75 percent of the vote among those with a doctorate (2 percent of the electorate). As in France, the electoral cleavage totally reversed between 1948 and 2016. Note: BA: bachelor’s degree or equivalent; MA: master’s degree or law or medical school degree; PhD: doctorate. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

For example, in the 2016 presidential election, voters with doctoral degrees (2 percent of the electorate) voted 75 percent of the time for the Democrat, Hillary Clinton, while fewer than 25 percent voted for the Republican, Donald Trump. Now, the important point is that this was not a whim of intellectuals who suddenly quit the Republican Party because it failed to choose a reasonable candidate. It was rather the culmination of a structural evolution that began half a century earlier. Indeed, if one looks at the gap in the Democratic vote between those with and without college degrees, one finds that it has grown slowly but steadily since the 1960s. Clearly negative in the period 1950–1970, it rose toward zero in the period 1970–1990, then turned distinctly positive after 1990 (Fig. 15.3).

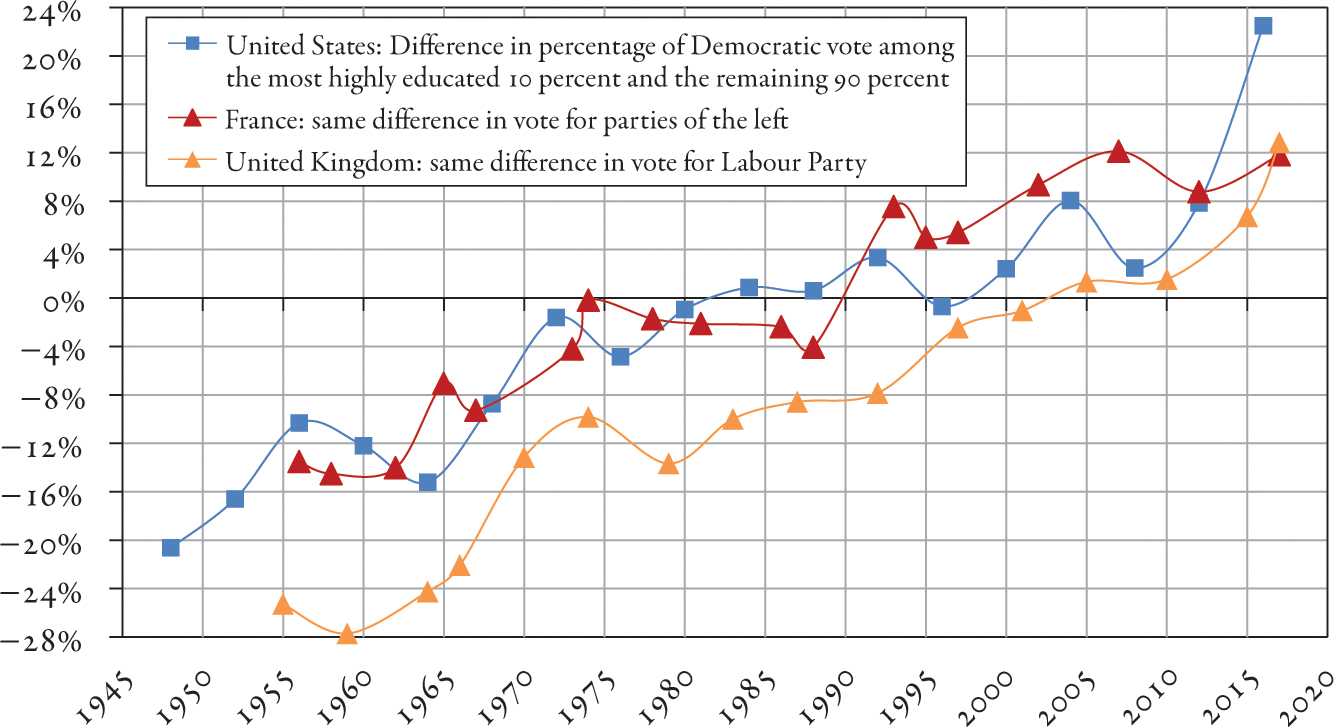

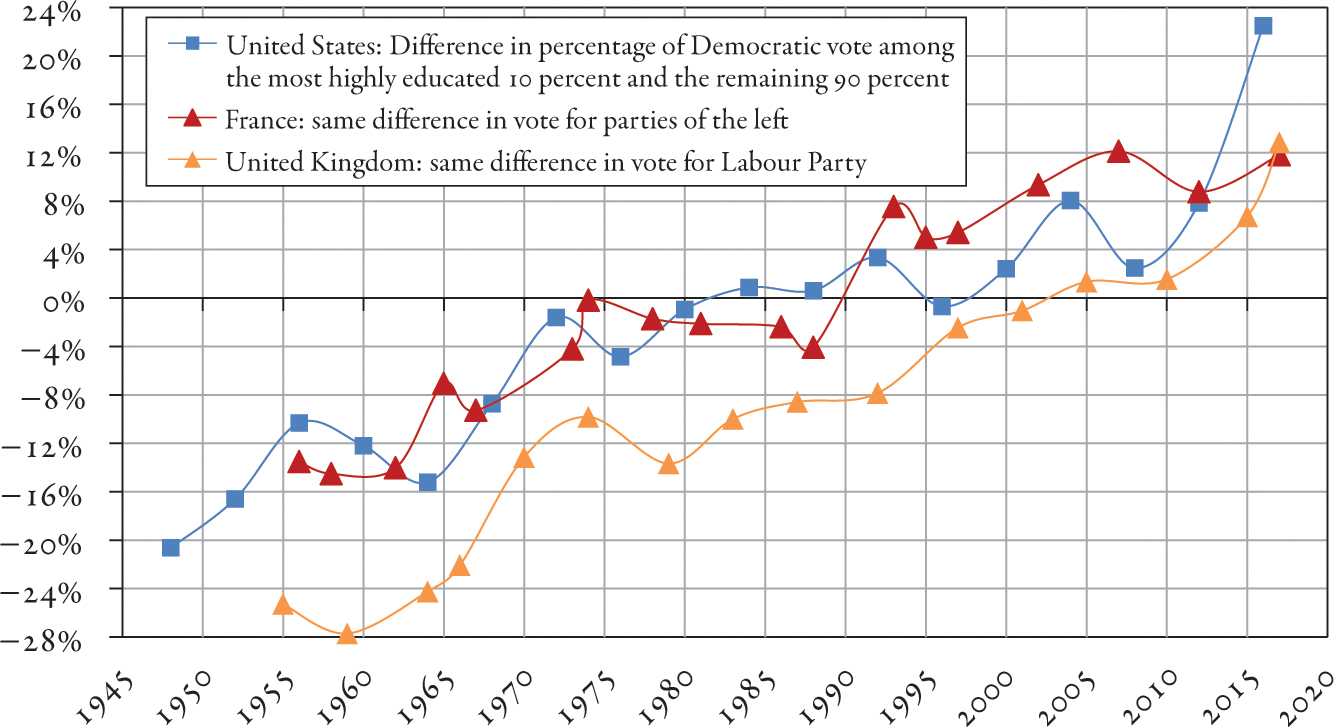

The evolution is even more dramatic if one looks at the gap between the most highly educated 10 percent and the remaining 90 percent (Fig. 15.4). This is because voting of the college-educated also turned around. In the 1950s and 1960s, the more advanced the diploma, the more likely the holder would vote Republican. In the 2000s and 2010s, the reverse is true: those with bachelor’s degrees (obtained after three or four years of study at a college or university) are more likely to vote Democratic than those who have only a high school diploma, but they are less enthusiastically Democratic than those with a master’s or a medical or law school degree, and even they are outdone by those with PhDs.3 We also find the same evolution if we look at the gap between the Democratic vote for the most highly educated 50 percent and the remaining 50 percent.4

FIG. 15.3. The Democratic Party and education: United States, 1948–2016

Interpretation: In 1948, the Democratic candidate obtained a score 20 percent lower among college graduates than among nongraduates; in 2016, the same figure was fourteen points higher. Controlling for other variables affects levels but does not change the trend. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

FIG. 15.4. The Democratic vote in the United States, 1948–2016: From the workers’ party to the party of the highly educated

Interpretation: In 1948 the Democratic share of the vote among the best educated 10 percent was twenty-one points lower than his share of the other 90 percent of the electorate; in 2016, the same figure was twenty-three points higher than for the rest of the electorate. Controlling for other variables affects the levels but not the trend. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

As in France, we also find that if we control for other socioeconomic variables, the basic pattern remains the same; these findings appear to be extremely robust. In the US case, it turns out that controlling for other variables raises the level of the curve. The primary reason for this is the racial factor (Figs. 15.3–15.4).5 Because the effect of race is roughly of the same size throughout the half century under investigation, it has no effect on the underlying trend.6

It is striking to see how similar the US and French results are. Like the left-wing parties in France, the Democratic Party in the United States transitioned over half a century from the workers’ party to the party of the highly educated. The same is true of the Labour Party in the United Kingdom and of various social-democratic parties in Europe (for instance, in Germany and Sweden). In all these countries, the expansion of educational opportunity coincided with a reversal of the educational cleavage in the voting structure. Although the general educational level in the United States was relatively advanced compared with Europe in the 1950s, the majority of the electorate did not yet have a college or even a high school diploma. In 1948, 63 percent of voters had not finished high school, and 94 percent did not have a college degree. Most of these voters identified as Democrats. Clearly, many of the children and grandchildren of those voters experienced upward mobility in terms of education. And the striking fact is that, just as in France, those who rose the most continued to vote Democratic whereas those who were less successful in their educational careers tended to identify more with the Republican Party (Fig. 15.2).7

Will the Democratic Party Become the Party of the Winners of Globalization?

Why did the Democratic Party become the party of the educated? Before attempting to answer this question, it is interesting to see how the structure of the Democratic electorate evolved in terms of income. Because education is an important determinant of income, it is natural to expect that the party of the highly educated will also have become the party of the highly paid. And indeed, we do observe an evolution of this sort. In the period 1950–1980, the profile of the Democratic vote as a function of income was clearly decreasing (the higher the income decile, the lower the Democratic vote). Then the curve flattened out in the 1990s and 2000s. Finally, in 2016, for the first time in the history of the United States, we find that the Democratic Party won more votes among the top 10 percent of US earners than did the Republican Party (Fig. 15.5).

FIG. 15.5. Political conflict and income in the United States, 1948–2016

Interpretation: In 1964, the Democratic candidate won 69 percent of the vote of the lowest income decile, 37 percent of the vote of the top income decile, and 22 percent of the vote of the top income centile. Generally, the profile of the Democratic vote is decreasing with income, particularly earlier in the period. In 2016, for the first time, the profile reversed: the top decile voted 59 percent Democratic. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

Does it follow, however, that the Democratic Party is on its way to becoming the party of the winners of globalization, like the new inegalitarian internationalist coalition in France? This is without a doubt one possible path forward. The reality is more complex, however, and I think it is important to emphasize the diversity of possible trajectories and variety of potential switch points ahead. Political-ideological transformation depends above all on the balance of power of the contending groups and their relative capacity for mobilization, and there is no justification for a deterministic analysis. In the French case, we saw that the highly educated class did not perfectly coincide with the highly paid class, in part because people with equivalent levels of education may choose more or less lucrative career paths (or experience different degrees of success in a given path), and in part because achieving a high income also depends in part on possessing some wealth, which is not fully correlated with level of education.

FIG. 15.6. Social cleavages and political conflict: United States, 1948–2016

Interpretation: In the period 1950–1970, the Democratic vote was associated with voters with lower levels of education, income, and wealth. In the period 1980–2010 it came to be associated with highly educated voters. In the period 2010–2020, it is close to being associated with high-income and wealthy voters as well. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

In fact, the available data suggest that high wealth has always been strongly associated with voting Republican and remained so in 2016 with Trump as the candidate, even though the strength of the relationship decreased (Fig. 15.6).8 In other words, the US party system in the period 1990–2020 has become a system of multiple elites, with a highly educated elite closer to the Democrats (the “Brahmin left”) and a wealthier and better paid elite closer to the Republicans (“merchant right”). This regime may be on the verge of turning into a classist confrontation in which these two elites merge in support of the Democratic Party, but the process is still incomplete and may yet change direction of a variety of reasons.

It bears emphasizing, moreover, that serious limitations of the available data make it very difficult to know the exact structure of the US vote. According to the data, the top centile of the income distribution was less likely to vote for Hillary Clinton than the top decile as a whole (Fig. 15.5). But the sample sizes and questionnaires make it impossible to be perfectly precise about this. In addition, the information we have about wealth from the US postelection surveys is quite rudimentary (and much more limited than in the French case) so that the estimates shown here should be treated with caution. It appears that the wealthiest voters continued to show a slight preference for the Republican candidate in 2016, but the gaps are so much reduced that uncertainty remains (Fig. 15.6).9

Among the factors that may encourage continued political-ideological evolution along these lines and lead to a gradual unification of elites, the evolution of the socioeconomic structure of inequality in the United States deserves to be mentioned. First, top incomes have increased sharply in the United States since the 1980s, and the beneficiaries, many of whom are highly educated and successful in their careers, have been able to accumulate a great deal of wealth in a short period of time. This means that the highly paid elite and the wealthy elite coincide to a greater degree now than was the case prior to 1980.10 Second, the fact that the system of higher education has become extremely costly for students (to say nothing of the fact that parental gifts are sometimes a factor in admission) is a structural factor contributing to the unification of the Brahmin and merchant elites. As noted earlier, the probability of access to higher education in general is strongly correlated with parental income in the United States.11 Recent studies of admissions to the best US universities have shown that most of them draw a larger proportion of their students from families in the top centile of the income distribution than from families in the bottom 60 percent (which means that children of the top centile are at least sixty times more likely to be admitted than children of the latter group).12 The fusion of educational and patrimonial elites will of course never be complete at the individual level, if only because of the diversity of aspirations and career choices. Nevertheless, compared with countries where the commodification of higher education is less advanced, the United States is probably the place where a political unification of elites is most likely to occur.13

It is also important to note that political parties and campaigns are for the most part privately financed in the United States. Now that the Supreme Court has eliminated the ban on corporate contributions, there is an obvious risk that candidates will represent the interests of financial elites.14 Furthermore, this affects both the Republicans and Democrats. Note, interestingly, that it was the Democratic Party (in Barack Obama’s 2008 campaign) that for the first time chose to renounce public funding to avoid limits on the amount it could spend from private contributions.15

Nevertheless, other factors cast doubt on the long-term viability of a transformation of the Democratic Party into the party of the winners of globalization in all its dimensions: educational as well as patrimonial. First, the presidential debates of 2016 showed the degree to which cultural and ideological differences remain between the Brahmin and merchant elites. Whereas the intellectual elite stressed values of level-headed rationality and cultural openness, which Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton sought to project, business elites favored deal-making ability, cunning, and virility, of which Donald Trump presented himself as the embodiment.16 In other words, the system of multiple elites has not yet breathed its last because at bottom it rests on two different and complementary meritocratic ideologies. Second, the 2016 presidential election showed the risk that any political party runs if it becomes too blatantly identified as the party of the winners of globalization. It then becomes the target of anti-elitist ideologies of all kinds: in the United States in 2016, this allowed Donald Trump to deploy what one might call the nativist merchant ideology against the Democrats. I will come back to this.

Last but not least, I do not believe that this evolution of the Democratic Party is viable in the long run because it does not reflect the egalitarian values of an important part of the Democratic electorate and of the United States as a whole. Dissatisfaction was obvious in the 2016 Democratic primaries, in which the “socialist” senator from Vermont, Bernie Sanders, ran neck-and-neck with Hillary Clinton despite the fact that Clinton enjoyed much greater support from the media. As mentioned earlier, the 2020 presidential contest now under way shows that nothing is written in advance, and some Democrats are now openly proposing a strongly progressive tax on large fortunes (especially financial wealth).17 The history of every inequality regime studied in this book shows that the ideologies deployed to justify inequality must have some minimum degree of plausibility if they are to survive. In view of the very rapid growth of inequality in the United States and the stagnation of the standard of living of the majority, it is unlikely that a political-ideological platform centered on the defense of the neo-proprietarian status quo and the celebration of the winners of globalization can last for long. As in France and elsewhere, the question facing the United States is rather one of possible alternatives to the status quo: more specifically, a choice between some form of nativist ideology and some form of democratic, egalitarian, and internationalist socialism.

On the Political Exploitation of the Racial Divide in the United States

For obvious reasons, the question of political exploitation of the racial divide has a long history in the United States. Slavery was in a sense congenital with the American Republic: recall that eleven of the first fifteen presidents were slaveowners. The Democratic Party was historically the party of slavery and states’ rights—especially the right to preserve and extend the slave system. Thomas Jefferson thought abolition possible only if the freed slaves could be sent back to Africa because he believed that peaceful coexistence with them on US soil was impossible. Slavery’s principal theoreticians, such as Democratic Senator John Calhoun of South Carolina, never tired of denouncing the hypocrisy of northern industrialists and financiers, who they said pretended to care about the fate of blacks but whose only objective was to turn them into proletarians to be exploited like the others. Abraham Lincoln’s victory on a “free soil” platform in the 1860 presidential elections led to the secession of the southern states, the Civil War, and then the occupation of the South by federal troops. But in the 1870s segregationist Democrats regained control in the South and imposed strict racial segregation (since it was impossible to send all blacks back to Africa). The Democratic Party also gained support in the North by championing the cause of the poor and of newly arrived immigrants against Republican elites. In 1884 they regained the presidency and in subsequent decades alternated regularly with Republicans on the basis of a social-nativist platform (segregationist and differentialist with respect to blacks but more social and egalitarian than the Republicans when it came to whites).18

That is more or less how things stood when Franklin D. Roosevelt, a Democrat, was elected president in 1932. At the federal level, of course, the new economic and social policies enacted under the New Deal benefited poor blacks as well as poor whites. But Roosevelt continued to rely on segregationist Democrats in the South, where many blacks were denied the right to vote. The first postelection surveys conducted after the presidential elections of 1948, 1952, 1956, and 1960 showed that black voters in the North were slightly more likely to vote for Democrats than for Republicans.19 It was not until the John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson administrations of the 1960s that the Democrats, partly against their will and under pressure from African American civil rights activists, wedded the cause of civil rights and won the massive support of the black electorate. In all presidential elections from 1964 to 2016, roughly 90 percent of blacks have voted for the Democratic candidate (Fig. 15.7). We even find peaks above 95 percent in 1964 and 1968, in the heat of the battle over civil rights, as well as in 2008, when Barack Obama was elected for the first time. Thus, the Democratic Party, which had been the party of slavery until the 1860s and then the party of racial segregation until the 1960s, became the preferred party of the black minority (along with abstention).

By contrast, the Republican Party, having been the party that freed the slaves, became in the 1960s the last refuge of those who had a hard time accepting the end of segregation and the growing ethnic and racial diversity of the United States. In the wake of George Wallace’s fruitless third-party run in 1968, southern Democrats who supported segregation began a slow migration to the Republican Party. There is no doubt that this “racist” vote (or “nativist” vote, to employ a more neutral term) played an important role in most subsequent Republican victories, especially Richard Nixon’s in 1968 and 1972, Ronald Reagan’s in 1980 and 1984, and Trump’s in 2016.

FIG. 15.7. Political conflict and ethnic identity: United States, 1948–2016

Interpretation: In 2016, the Democratic candidate won 36 percent of the vote of white voters (70 percent of the electorate), 89 percent of the vote of African American voters (11 percent of the electorate), and 64 percent of the vote of Latinos and those declaring themselves to be of other ethnicities (19 percent of the electorate, of which 16 percent are Latinos). In 1972, the Democratic candidate won 32 percent of the white vote (89 percent of the electorate), 82 percent of the African American vote (10 percent of the electorate), and 64 percent of other categories (1 percent of the electorate). Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

Note, moreover, that the ethno-racial structure of the United States, as measured both by the US census and the postelection surveys, has changed considerably over the past half century. From the presidential election of 1948 to that of 2016, blacks have represented about 10 percent of the electorate. Other “ethnic minorities” accounted for a little over 1 percent in 1968 but thereafter increased sharply to 5 percent in 1980, 14 percent in 2000, and 19 percent in 2016. These are mainly people who declare themselves to be “Hispanic or Latino” according to the terms of the census and surveys.20 All told, in the 2016 election won by Trump, “minorities” accounted for 30 percent of the electorate (11 percent black, 19 percent Latinos and other minorities), compared with 70 percent white; the white share will diminish in the coming decades. Note, too, that Latinos and other minorities have always voted strongly in favor of Democratic candidates (55–70 percent) but not as strongly as blacks (90 percent). As for whites, since 1968 a majority of white voters have voted Republican: if only whites had voted, not a single Democratic president would have been elected in the last fifty years (Fig. 15.7).

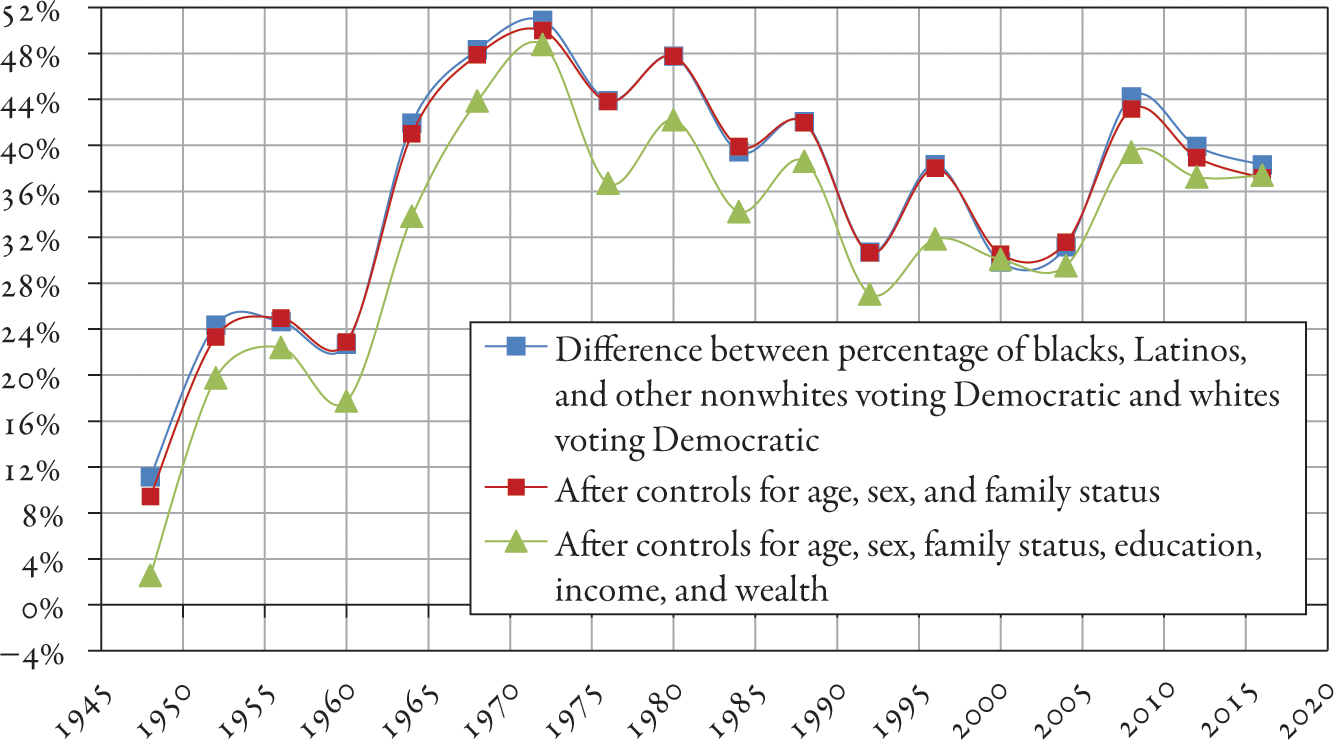

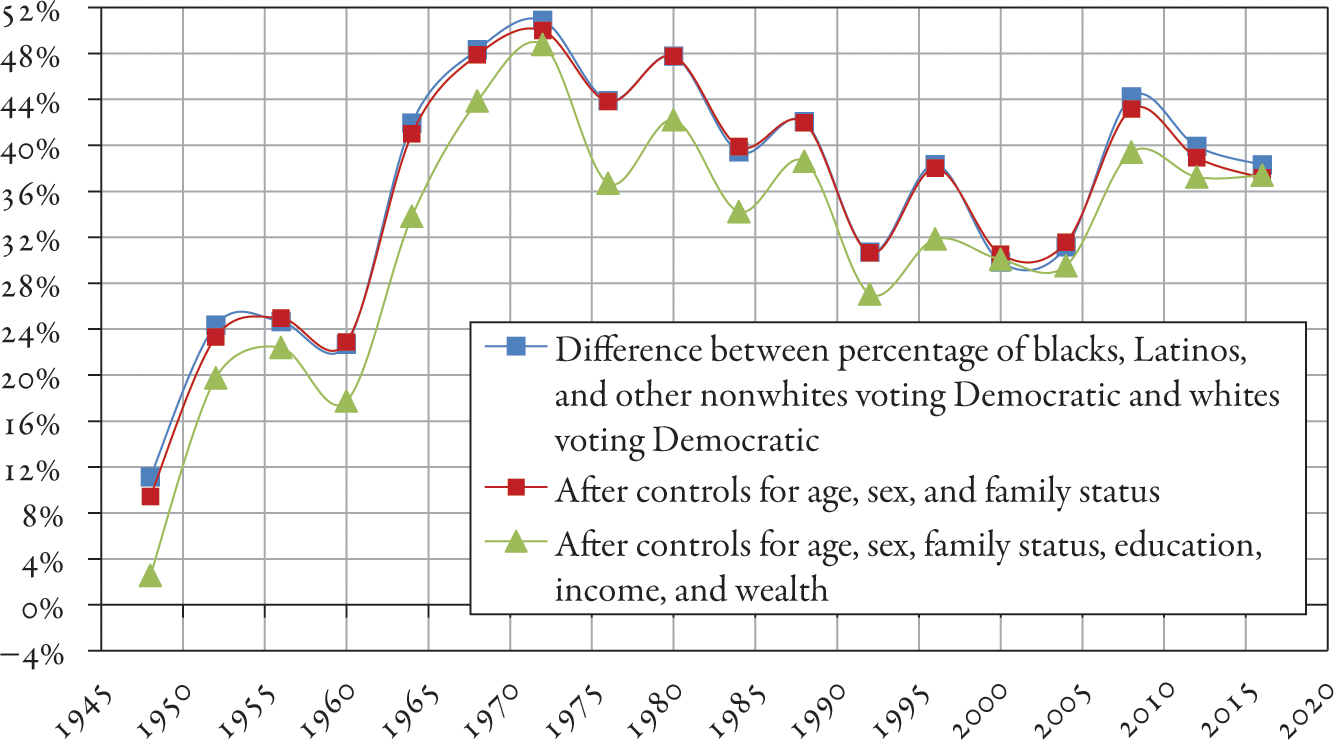

FIG. 15.8. Political conflict and racial cleavage in the United States, 1948–2016

Interpretation: In 1948, the Democratic vote was eleven points higher among African American and other minority voters (9 percent of the electorate) compared with whites (91 percent of the electorate). In 2016, the Democratic vote was thirty-nine points higher among African Americans and other minorities (30 percent of the electorate) than among whites (70 percent of the electorate). Controlling for other socioeconomic variables has a limited impact on this gap. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

Note, moreover, that only a small part of the massive minority vote in favor of Democratic candidates since the 1960s can be explained by socioeconomic characteristics of the electorate. The roughly forty-point gap between the minority and white votes for Democrats decreases very slightly over time owing to the increasing relative share of Latinos but remains extremely high (Fig. 15.8). The obvious explanation for this very stark electoral behavior is that minorities, especially the black minority, perceive the Republicans as violently hostile to them.

“Welfare Queens” and “Racial Quotas”: The Republicans’ Southern Strategy

Of course, no Republican candidate—not Nixon or Reagan or Trump—has ever explicitly proposed reinstating racial segregation. But they have openly admitted former proponents of segregation into their ranks. To this day, they have continued to tolerate white supremacist movements, at times appearing with their leaders. This was clear after the events of 2017 in Charlottesville, Virginia, when President Trump said that he saw “good people on both sides” of a demonstration pitting neo-Nazis and remnants of the Ku Klux Klan against protesters.21

Many segregationist Democrats eventually left the party and joined the Republicans: for example, Strom Thurmond, who served as a Democratic senator from South Carolina from 1954 to 1967 and then as a Republican from 1964 to 2003. A great advocate of the cause of states’ rights (that is, the right of the southern states to continue to practice segregation and more generally not to enforce federal laws and executive orders deemed too favorable to blacks and other minorities), Thurmond symbolized the transfer of these issues from the Democratic Party (which had been their standard bearer from the early nineteenth to the middle of the twentieth centuries) to the Republicans. In 1948, worried about the influence that northern pro–civil rights Democrats had already begun to exert on the Democratic Party, Thurmond ran for president as a dissident segregationist Democrat under the banner of the ephemeral “States’ Rights Democratic Party” (commonly known as “Dixiecrats”).22

The situation grew tenser after the Johnson administration tried to force the southern states to end segregation, especially in schools, after 1964. Barry Goldwater, the Republican candidate in the 1964 election, opposed the Civil Rights Act. Although he lost to Johnson, he took up the cause of the South and its opposition to the federal government. To circumvent the hostility of southern state governments, Johnson promoted programs such as Head Start, which in effect funneled federal money directly to local nonstate organizations so as to fund day care and health centers in disadvantaged neighborhoods, many of them black.23 Nixon won the 1968 election by opposing such federal interference. In particular, he stood against any generalization of timid experiments with busing, which sought to mix children from black and white neighborhoods in the same schools, and brandished the threat of racial quotas that would allow blacks to take the place of allegedly better qualified whites in universities and government jobs.24 The Republicans’ “southern strategy” paid off handsomely in the 1972 presidential election, in which Nixon captured the votes that had gone to Wallace in 1968. He was triumphantly reelected over the Democrat George McGovern, a strong opponent of the Vietnam War and proponent of new social policies intended to cap off Roosevelt’s New Deal and Johnson’s War on Poverty, which Nixon successfully opposed.

Since Nixon, Republican candidates have resorted to more subtle, coded attacks on social policies alleged to lavish money on the African American population. It was common, for instance, to attack “welfare queens,” code for “single black mothers.” This term was used by Ronald Reagan in the 1976 Republican primaries and then again in the 1980 campaign. Reagan was a fervent supporter of Goldwater in the 1964 campaign, during which he launched his political career by speaking on behalf of the Republican candidate. Reagan also opposed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which he attacked as unnecessarily humiliating to southerners and excessively intrusive.25 Broadly speaking, exploitation of racial issues played an important role in the movement leading to the triumph of the “conservative revolution” in the 1980s.26 The new conservative ideology that developed around Goldwater in 1964, Nixon in 1972, and Reagan in 1980 was based on both virulent anticommunism and strident opposition to the New Deal and to the growing power of the federal government and its social policies. Those social policies were charged with encouraging the alleged laziness of people of color (a canard endlessly repeated since the abolition of slavery). The money spent on the modest welfare state that the United States had established in the New Deal and New Frontier eras was said to be wasteful and intrusive and above all a diversion from the more important demands of the Cold War and national security, which the “socialistic” Democrats were accused of neglecting, while Republicans promised to restore American greatness.

These episodes are important because they remind us that Donald Trump’s position on racial issues (as indicated by his remarks after the white supremacist demonstrations in Charlottesville in 2017 and his comments on statues of Confederate generals) has to be seen in the context of a long Republican tradition dating back to the 1960s. What is new is that in the meantime other minorities have also become important. Trump therefore attacks Latinos, whom he describes in particularly unflattering terms. To stop them from coming into the United States he wants to build a huge wall, a symbol of the importance he ascribes to the border issue. During his 2016 campaign and since his election he has attacked virtually every nonwhite group in the United States, especially the Muslim minority (despite its small numbers on US soil).

Electoral Cleavages and Identity Conflicts: Transatlantic Views

European countries, and especially France, have long been intrigued by racial cleavages in the United States and their role in America’s exotic politics and partisan dynamics. In particular, it has always been hard for Europeans to understand how the Democratic Party could have gone from the pro-slavery and segregationist party to the party of minorities while the Republican Party, which once counted so many abolitionists in its midst, became the racialist and nativist party, which minorities massively reject. In fact, these surprising transformations and comparisons are highly instructive. They can help us to understand changes currently under way and therefore to anticipate some possible political-ideological trajectories in the years to come, not only in the United States but also in Europe and other parts of the world.

It is particularly striking to see that electoral cleavages due to identity conflicts are today comparable in magnitude on both sides of the Atlantic. In the United States, the gap between the black and Latino vote for the Democratic Party and the vote of the white majority has been about 40 percentage points for the past half century; controlling for variables other than race barely changes this finding (Figs. 15.7–15.8). In France, we found that the gap between the Muslim vote and the vote of the rest of the population for parties of the left (themselves undergoing redefinition) has also been about 40 percentage points for several decades now, and controlling for other variables again has little effect.27 In both cases the cleavage defined by racial or religious identity is immense—much greater, for instance, than the gap between the vote of the top income decile and that of the bottom 90 percent, which in both France and the United States is generally on the order of ten to twenty points. In the United States we find that since the 1960s, in election after election, 90 percent or more of African American voters have voted for the Democratic Party (and barely 10 percent for the Republicans). In France, 90 percent of Muslims vote in election after election for the parties of the left (and barely 10 percent for the parties of the right and extreme right).

Apart from these formal similarities (which would have astonished a French observer if one had predicted them a few decades ago), it is important to note the differences between the two countries. In the United States, the black minority is in large part descended from slaves, and the Latino minority is largely the product of immigration from Mexico and Latin America. In France, the Muslim minority is the product of postcolonial immigration, primarily from North Africa and to a lesser extent from sub-Saharan Africa. To be sure, the two cases share an important point in common. In both countries, a white majority of European origin, which long wielded uncontested power over the nonwhite population (whether by slavery, segregation, or colonial domination), must now cohabit with nonwhites in a single political community. Disagreements must be settled at the ballot box, in principle on the basis of (at least formally) equal rights. In the long run of human history, this is clearly a radically new phenomenon. For centuries, relations between populations from different regions of the world were limited to military domination and brute force or else to commercial relations largely structured by the balance of military power. The fact that we are now witnessing, within the confines of a single society, relations of a quite different kind—based on dialogue, cultural exchange, intermarriage, and the emergence of unprecedented mixed identities—is an undeniable sign of civilizational progress. The resulting identity conflicts have been exploited for political purposes, and this has given rise to significant challenges, which need to be examined closely. Nevertheless, even a rapid comparison of today’s intergroup relations with those observed in the past suggests that we need to keep the magnitude of current difficulties in perspective and refrain from idealizing the past.

Beyond this general similarity between the US and French situations, however, it is clear that the identity conflicts in the two countries take very specific forms. In terms of electoral cleavages, what is most striking about the United States is that Latinos and other (nonblack) minorities (henceforth lumped together as “Latinos”), which currently account for about 20 percent of the electorate, fall somewhere between white and blacks in voting behavior. For instance, 64 percent of Latinos voted for the Democratic candidate in 2016, compared with 37 percent of whites and 89 percent of blacks. This intermediate position has not changed much since 1970 (Fig. 15.7). How it evolves in the future will have a decisive impact on the structure of political conflict in the United States in view of the increasing weight of minorities in general (30 percent of the electorate in 2016 if one groups together blacks, Latinos, and other minorities) and the declining importance of the white majority (70 percent in 2016).28

FIG. 15.9. Political conflict and origins: France and United States

Interpretation: In 2012, the Socialist candidate in the second round of the French presidential election obtained 49 percent of the vote of those with no foreign origin (no foreign-born grandparent) and of those with European foreign origin (primarily Spain, Italy, and Portugal) and 77 percent of the vote of those with non-European foreign origin (primarily North Africa and sub-Saharan Africa). In 2016, the Democratic candidate in the US presidential election obtained 37 percent of the white vote, 64 percent of the vote of Latinos and others, and 89 percent of the African American vote. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

By contrast, in France, we find that people of European foreign origin vote on average the same way as those who declare themselves to be of French descent. For example, in the 2012 presidential election, 49 percent of both groups voted for the Socialist candidate in the second round, compared with 77 percent of voters of non-European foreign origin (Fig. 15.9). Note, too, that people who declare themselves to be of foreign origin (defined as having at least one foreign-born grandparent) accounted for about 30 percent of the French electorate in the 2010s, roughly the same as “minorities” in the United States. But this analogy is purely formal. In particular, voters who declared themselves to be of European origin—primarily from Spain, Portugal, and Italy and roughly 20 percent of the population—do not see themselves and are not perceived as a “minority,” much less as a “Latino” minority. Similarly, voters who declared themselves to be of non-European foreign origin—in practice mainly from North Africa and sub-Saharan Africa and roughly 10 percent of the population—are in no way a homogeneous group, much less an ethnic or religious category. Many say they have no religion. Indeed, this group only partially overlaps the group of people who identify as Muslims.29

On the Fluidity of Identities and the Danger of Fixed Categories

One key difference between the United States and France (and Europe more generally) has to do with the fact that ethno-religious cleavages in France are more fluid that racial cleavages in the United States. According to the “Trajectories and Origins” (TeO) survey conducted in France in 2008–2009, for example, more than 30 percent of respondents with a parent of North African descent are children of mixed couples (in which one parent is not of foreign origin).30 When intermarriage levels are this high, clearly the very idea of “ethnic” identity has to be quite flexible. Origins and identities are constantly mixing, as we see for instance, in the very rapidly changing relative popularity of first names from generation to generation.31 It would not make much sense to ask such people to say whether they wholly identify with this or that “ethnic” group. That is why there is a fairly broad consensus in France, and to a certain extent in Europe (although the United Kingdom is in an intermediate situation, as we will see in a moment), that it is not appropriate to ask people what “ethnic” group they identify with. To require an answer to such a question would be unfair to those who see their origins and identity as mixed and multidimensional and who aspire simply to live their lives without having to show their papers and declare their “ethnic” identity. People can of course volunteer to answer questions in specific, noncompulsory surveys about their origins and about the birthplace of their parents or grandparents or their religious, philosophical, or political beliefs. But that is very different from requiring them to identify with an ethnic or racial group on a census form or mandatory administrative procedure.

In the United States, the business of assigning identities has very different historical roots. In the slave era and beyond, census agents assigned a “black” identity to slaves and their descendants, generally in accordance with the “one-drop rule”: if a person had a single black ancestor, no matter how many generations back, that person was considered “black.” Until the 1960s, many southern states prohibited interracial marriage. The US Supreme Court made that illegal in 1967. Intermarriage has increased considerably since then, including marriage between blacks and whites: 15 percent of African Americans were in mixed marriages in 2010 (compared with barely 2 percent in 1967).32 Still, the obligation to declare ethno-racial identity in the United States, in censuses and other surveys, has probably sharpened lines between groups, even though identities are much less clear-cut in reality.

Despite these important differences of national context, identity issues are currently being exploited in both the United States and France (and elsewhere in Europe), and the resulting political cleavages are of comparable magnitude. The exploited prejudices and cultural stereotypes are not exactly the same in the two cases, but there are common elements. In the United States, a term like “welfare queen” is meant to stigmatize both the alleged laziness of the single mother and the absence of the father. In France, racists accuse individuals of Maghrebi or African background of irrepressible criminal tendencies. Immigrants are often suspected of abusing the welfare system. They are also associated with unpleasant “noise and smells,” even by political leaders not of the far right but of the center-right.33

This type of racist discourse calls for several responses. First, many studies have shown that allegations of minority abuse of the welfare system are baseless. On the other hand, many studies have shown that minorities and non-European immigrants are discriminated against in the workplace: given equal levels of education, the minority applicant is less likely to be hired than the white applicant.34 Although studies of this kind will never convince everyone, they can and should be more widely publicized and brought to bear in public debate.35

It is also important, I think, to note that identity conflicts are fueled by disillusionment with the very ideas of a just economy and social justice. In Chapter 14, we saw that the French electorate was divided into four nearly equal parts by the conjunction of two issues: immigration and redistribution. If redistribution between the rich and the poor is ruled out (not just in the realm of political action but sometimes even in the realm of debate) on the grounds that the laws of economics and globalization strictly prohibit it, then it is all but inevitable that political conflict will focus on the one area in which nation-states are still free to act, namely, defining and controlling their borders (and if need be inventing internal borders). Even though we are living in a postcolonial world, identify conflict is not inevitable. If it sometimes seems that way, part of the reason, I think, is that the fall of communism extinguished all hope of truly fundamental socioeconomic change. If we want our politics to be about something other than borders and identity, we must therefore bring the issue of a just distribution of wealth back into public debate. I will have more to say about this.

The Democratic Party, the “Brahmin Left,” and the Issue of Race

We come now to a particularly complex and important issue. In the US context, it is tempting to explain the “Brahminization” of the Democratic Party by the growing importance of racial and identity cleavages since the 1960s. The argument goes like this: disadvantaged whites left the Democratic Party because they refused to accept that their party had become the champion of blacks. On this view, it is nearly impossible for disadvantaged blacks and whites to join forces in a viable political coalition in the United States. As long as the Democratic Party was overtly racist and segregationist, or at any rate as long as disagreement on racial issues between northern and southern Democrats remained muted (broadly speaking, until the 1950s), it was possible to enlist the support of disadvantaged whites. But once the party ceased to be antiblack, it became almost inevitable that it would lose lower-class whites to the Republican Party, which had no choice but to fill the racist void left vacant by the Democrats. In the end, the only exception to this iron law of American politics will have been the period 1930–1960, the era of the New Deal coalition, which somehow managed to keep disadvantaged whites and blacks together in the same party at the cost of some tenuous compromises and, even then, only under exceptional conditions (the Great Depression and World War II).

To my mind, this theory is too deterministic and ultimately not very convincing. The problem is not just that it depends on the notion that the disadvantaged classes are by their very essence permanently racist. As noted in the French case, the working class is no more naturally or eternally racist that the middle class, the self-employed, or the elite. More importantly, the theory is unconvincing because it fails to account for the observed facts. First, although there is no denying that racial issues played a key role in the flight of southern whites from the Democratic Party after 1963–1964,36 the reversal of the educational cleavage since the 1950s occurred throughout the United States, in both North and South, independent of attitudes on racial issues. Furthermore, it unfolded slowly and steadily from the 1950s to the present (Figs. 15.2–15.4). It is difficult to explain such a long-term structural evolution in terms of a change of position of the Democratic Party on racial issues—a change that came about quite rapidly in the 1960s and whose effects on the black vote and the differential between the minority vote and the white vote were in any case immediate (Figs. 15.7–15.8).

One final but very important point: the same reversal of the educational cleavage also occurred in France, with a magnitude and chronology virtually identical to the United States (Figs. 14.2 and 14.9–14.11). We will also find the same basic trend in the United Kingdom, Germany, Sweden, and all the Western democracies. In these countries there was no civil rights movement and nothing comparable to the radical repositioning of the Democratic Party on racial issues in the 1960s. To be sure, one could point to the rising importance of the cleavage around immigration and identity in France, the United Kingdom, and elsewhere in Europe. But this cleavage begins to play a central role only much later, in the 1980s and 1990s, and cannot explain why the educational cleavage began to turn around much earlier, in the 1960s. Finally, we will see later that the educational cleavage also turns around in countries where the cleavage with respect to immigration never played a central role.

It therefore seems to me more promising to look for more direct explanations. If the Democratic Party has become the party of the highly educated while the less educated have fled to the Republicans, it must be because the latter group believes that the policies backed by the Democrats increasingly fails to express their aspirations. Furthermore, if such a belief is sustained for half a century and shared across so many countries, it cannot be a simple misunderstanding. Hence it seems to me that the most likely explanation is the one I began to develop for France. To summarize: the Democratic Party, like the parties of the electoral left in France, changed its priorities. Improving the lot of the disadvantaged ceased to be its main focus. Instead, it turned its attention primarily to serving the interests of the winners in the educational competition. From the turn of the twentieth century until the 1950s, the ambitions of the Democratic Party were strongly egalitarian, not only in tax policy but also with respect to education. Its goal was to ensure that everyone in every age cohort would receive not just a primary but also a secondary education. On this and other social and economic issues, the Democrats seemed to be clearly less elitist and more concerned with the disadvantaged (and ultimately with the prosperity of the country) than the Republicans.

Between 1950–1970 and 1990–2010, that perception was totally transformed. The Democratic Party became the party of the educated in a country where the university system is highly stratified and inegalitarian and the disadvantaged have virtually no chance of gaining admission to the most selective colleges and universities. In such circumstances, and in the absence of structural reform of the system, it is not abnormal that the least advantaged feel abandoned by the Democrats. The Republicans’ skill in exploiting racial issues and above all in exploiting the fear of loss of status among disadvantaged whites surely explains part of their electoral success. In 1972, when McGovern proposed a federal minimum income to be paid for by an increase in the progressivity of the inheritance tax, Nixon supporters whispered that he was proposing yet another form of welfare for African Americans. Similarly, one reason for hostility to Obama’s healthcare reform, the 2010 Affordable Care Act (popularly known as Obamacare), was that whites did not want to pay for health insurance for minorities. In general, the race factor has often been cited (rightly) among the structural reasons why social and fiscal solidarity are weaker in the United States than in Europe and why the United States has no equivalent to the European welfare state.37 But it would be a mistake to reduce everything to the race factor, which cannot explain why we find an almost identical reversal of the educational cleavage on both sides of the Atlantic. If Democrats are now seen as serving the interests of the highly educated rather than the disadvantaged, it is above all because they never came up with an appropriate response to the conservative revolution of the 1980s.

Lost Opportunities and Incomplete Turns: From Reagan to Sanders

In the 1980 election campaign, Ronald Reagan succeeded in persuading Americans to accept a new account of their own history. To a country plagued by doubt after the Vietnam War, Watergate, and the Iranian Revolution, Reagan promised a return to greatness. His recipe was simple: cut federal taxes and make them less progressive. It was the New Deal and its confiscatory taxes and socialistic policies that had sapped the energy of American entrepreneurs and allowed the countries that had lost World War II to catch up with the United States. Reagan had rehearsed these themes during the 1964 Goldwater campaign as well in his 1966 race for governor of California, where he repeatedly explained that the “Golden State” could no longer be “the welfare capital of the world” and that no country in the world had ever survived paying a third of its gross domestic product (GDP) in taxes. In 1980 and 1984—in a country obsessed by fear of decline; the Cold War; and the rapid growth of Japan, Germany, and the rest of Europe—Reagan successfully parlayed these issues into a victory in the presidential race. The top federal income tax rate, which had averaged 81 percent from 1932 to 1980, was cut to 28 percent by the 1986 tax reform, the quintessential Reagan-era reform.38

From the vantage point of 2019, the effects of Reagan’s reforms seem quite dubious. Growth of per capita national income fell by half in the three decades following Reagan’s term (compared with the previous three or four decades). Since the goal of the reforms was to boost productivity and growth, this can hardly be counted a satisfactory outcome. In addition, inequality skyrocketed, so much so that the bottom 50 percent of the income distribution has seen no income growth since the early 1980s, which is totally unprecedented in US history (and fairly uncommon for any country in peacetime).39

And yet the Democratic presidents who followed Reagan, Bill Clinton (1992–2000) and Barack Obama (2008–2016), never made any real attempt to revise the narrative or reverse the policies of the 1980s. In particular, in regard to the reduction of the progressive income tax (whose top marginal rate fell to an average of 39 percent from 1980 to 2018, half its level in the period 1932–1980) and the de-indexing of the federal minimum wage (which led to a clear loss of purchasing power since 1980),40 the Clinton and Obama administrations basically validated and perpetuated the basic thrust of policy under Reagan. This may be because both Democratic presidents, who lacked the hindsight we have today, were partly convinced by the Reagan narrative. But it may also be that acceptance of the new fiscal and social agenda was partly due to the transformation of the Democratic electorate and to a political and strategic choice to rely more heavily on the party’s new and highly educated supporters, who may have found the turn toward less redistributive policies personally advantageous. In other words, the “Brahmin left,” which is what the Democratic Party had become by the period 1990–2010, basically shared common interests with the “merchant right” that had ruled under Reagan and George H. W. Bush.41

The fall of the Soviet Union in 1990–1991 was clearly another political-ideological factor that played a key role in the United States, Europe, and elsewhere in this period. In some ways this validated the Reagan strategy of restoring US power and the capitalist model. The collapse of the communist countermodel was undoubtedly a powerful reason for the renewal of faith—in some cases unlimited faith—in the self-regulated market and private ownership of the means of production. It was also one of the reasons why Democrats in the United States and Socialists, Labourites, and Social Democrats in Europe largely gave up thinking about ways to embed the market and transcend capitalism in the period 1990–2010.

As usual, however, it would be a mistake to interpret these trajectories in a deterministic fashion. These long-term intellectual and ideological shifts were important, but there were also many switch points where things might have taken a different course. For instance, the 1978 tax revolt in California, which was in some ways a harbinger of Reagan’s successful run for the presidency two years later,42 began with skyrocketing real estate prices in California in the 1970s, which led to sharp and largely unanticipated increases in the property taxes paid by homeowners. These tax hikes were often staggering, and they were a problem because the sudden increase in house prices was not accompanied by a corresponding increase in the income needed to pay the tax. Taxpayer resentment was even greater because the property tax is proportional: all homeowners pay the same rate, regardless of how many financial assets they own or how much debt they owe. Hence homeowners with low incomes and buried in debt still found themselves burdened with huge tax increases.43 Discontent with this situation was cleverly exploited by conservative antitax activists, whose agitation led to the passage in June 1978 of the famous Proposition 13, which set a permanent ceiling on the property tax of 1 percent of the value of the property. This law, still in force today, has limited funding for California schools and led to repeated state budget crises.

Apart from its importance in the rise of Reaganism, this episode is interesting because it shows how very short-term phenomena (such as the spike in real estate prices in the 1970s and the success of a campaign for an antitax referendum) can combine with longer-term intellectual and ideological failures (in this case, failure to think about transforming property taxes into progressive taxes on all assets, both real estate and financial, net of debt) to produce major political changes. As in the case of the progressive income tax, it is important to be able to tax net wealth at different levels depending on whether an individual has amassed a fortune of $10,000, $100,000, $1 million, or $10 million.44 All surveys show that citizens favor such a progressive tax.45 It is also essential to index the brackets of any wealth tax to the evolution of asset prices to prevent the tax from increasing automatically just because asset prices rise, without any prior debate, justification, or decision. In the case of the 1978 California tax revolt, the damage was even greater because the referendum put an end to revenue sharing between rich and poor school districts, which the California Supreme Court had authorized in 1971 and 1976 (in the so-called Serrano decisions) and which enjoyed widespread popular support at the time.46

Several recent developments suggest that the phase of US politics that began with Reagan’s election in 1980 is about to end. First, the 2008 financial crisis showed that deregulation had gone too far. Second, growing awareness of the extent of the increase of inequality since 2000 and of wage stagnation since 1980 has gradually increased people’s willingness to reevaluate the Reagan turn. Both of these factors have helped to open up political and economic debate in the United States, as the very close 2016 Democratic primary race between Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders shows. As noted previously, in the 2020 presidential campaign, several candidates (including Sanders and Senator Elizabeth Warren) have proposed restoring the progressivity of the income and inheritance taxes and creating a federal wealth tax.47 Revenue produced by such a wealth tax could be invested in the educational system, especially in public universities, whose finances have suffered greatly compared with those of the best private universities. There have also been proposals to share power and voting rights between employees and shareholders on the boards of directors of private US firms as well as to create a universal health insurance plan (Medicare for All), as is the norm in Europe (with better results at lower cost than the current US system provides).48

It is much too soon to say what will come of these developments. I think it is important, however, to insist on two things: first, the total reversal of the educational cleavage is not going to be undone overnight, and second, it is extremely important to reform the educational system. The Democratic Party has become the party of the highly educated in a country with a hyper-stratified inegalitarian educational system. Democratic administrations never did anything to change this (nor did they even say how they might go about changing if they ever commanded a majority for doing so). Such a situation can only breed mistrust between the disadvantaged classes and the hypereducated Democratic elite, who might as well be living in different worlds. Trump rode a wave of distrust for the “Brahmin” elite to win the election (without proposing any tangible solutions to the country’s problems other than building a wall on the Mexican border and cutting his own taxes, for all the good either will do).49 The answer is not simply to increase investment in public universities. Basic changes in the admissions policies of both private and public universities are needed, including common rules to improve the chances of currently disadvantaged groups. In general, without bold and clearly comprehensible reforms, it is hard to see how the disadvantaged classes, always somewhat alienated from politics in the United States, can be brought back into the process.50

The Transformation of the British Party System

Let us turn now to the case of the United Kingdom. Using postelection surveys as in France, we can study the structure of the electorate in British elections since the mid-1950s. Compared with the United States, the bipartite system in Britain is more complex and fluctuating. When we look at the distribution of votes for the main parties in legislative elections from 1945 to 2017, we find that although the Labour Party and the Conservative Party were dominant, the situation is more complex than in the United States (Fig. 15.10).

In the 1945 elections, Labour won 48 percent of the vote compared with 36 percent for the Tories; the two parties together thus claimed 84 percent of the vote. Despite the prestige garnered from having stewarded the country to victory in World War II, the Conservatives, led by Winston Churchill, were decisively beaten, and Labour’s Clement Attlee became prime minister. The 1945 election was of fundamental importance in both British and European electoral history. It was the first time that the Labour Party by itself won a majority of seats in the House of Commons, which enabled it to assume power and enact its program to establish the National Health Service (NHS), institute an ambitious social insurance system, and significantly increase the progressivity of income and inheritance taxes. Furthermore, the 1945 election turned the two-party system in Britain upside down: throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries the two main parties had been the Tories (or Conservatives) and the Whigs (renamed the Liberals in 1859). Barely thirty years after the People’s Budget, which marked the Liberals’ victory over the House of Lords in 1909–1911, Labour came to power in 1945 following several decades of intense competition with the Liberals, whom they permanently replaced as the main alternative to the Conservatives. The country that had been the most aristocratic of all at the turn of the twentieth century, the one in which the trifunctional schema had formed a symbiotic relationship with the logic of proprietarianism, also became the country in which a self-avowed party of the working class now held power.51

FIG. 15.10. Legislative elections in the United Kingdom, 1945–2017

Interpretation: In the 1945 legislative election, Labour won 48 percent of the vote and the Conservatives 36 percent (for a total of 84 percent of the vote for the two main parties). In the 2017 elections, the Conservative Party won 42 percent of the vote and Labour 40 percent (for a total of 82 percent). Note: Liberals/LibDem: Liberals, Liberal Democrats, SDP Alliance. SNP: Scottish National Party. UKIP: UK Independence Party. Other parties include green and regionalist parties. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

The Liberals would never regain their previous role. They eventually redefined themselves as Liberal Democrats and then as an SDP-Liberal alliance in the 1980s after a split in the Labour Party.52 After winning 10–25 percent of the vote in the period 1980–2010, the Liberal Democrats fell back to less than 10 percent in the 2015 and 2017 elections. In 2017, the Conservatives led by Theresa May won 42 percent of the vote while Labour, led by Jeremy Corbyn, won 40 percent, for a total of 82 percent for the two major parties; the remaining votes were shared by the LibDems, the UK Independence Party (UKIP), the Scottish National Party (SNP), and green and regionalist parties. As in the United States, I will focus on the evolution of the structure of the vote for the two main parties, Labour and Conservative, in the period 1955–2017.53

The first finding is that, over the past half century, the Labour Party, like the Democrats in the United States, has also become a party of the highly educated. In the 1950s the Labour vote among the highly educated was 30 percentage points lower than among the rest of the population. In the 2010s it was the reverse: ten points higher among those with tertiary degrees compared with the rest of the population. As in France and the United States, this reversal of the educational cleavage has affected all levels of education (not only between primary, secondary, and tertiary levels but also within the secondary and tertiary groups). The reversal has been slow and steady over six decades, and the basic trend is barely affected when we control for age, sex, and other individual socioeconomic characteristics (Figs. 15.11–15.12).

Compared with the French and US cases, however, the British evolution takes place slightly later. At the beginning of the period, the Labour vote is concentrated among the less educated at the beginning of the period, and it is not until the very end that the more highly educated clearly swing over to the Labour side (Fig. 15.13).54 This relative lag reflects an important reality—namely, that the Labour vote is still more of a working-class vote than either the Democratic vote in the United States or the Socialist and Communist votes in France.

FIG. 15.11. Labour Party and education, 1955–2017

Interpretation: In 1955, the Labour Party scored twenty-six points lower among those with college degrees compared to those without; in 2017, it scored six points higher among those with college degrees compared to those without. Controlling for other variables affects the levels but does not alter the trend. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

FIG. 15.12. From the workers’ party to the party of the highly educated: The Labour vote, 1955–2017

Interpretation: In 1955, the Labour Party scored twenty-five points lower among the most highly educated 10 percent than among the other 90 percent of voters; in 2017, its score was thirteen points higher among the most highly educated 10 percent. Controlling for other variables affects levels but does not alter the trend. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

It is interesting, moreover, to note that the authentically working-class British Labour party long frightened some of Britain’s intellectual elite. The most famous example is that of John Maynard Keynes, who in a 1925 article explained why he could never vote for Labour and would continue, come what may, to vote for the Liberals. In sum, he worried about Labour’s lack of intellectuals worthy of the name (and no doubt economists in particular) to keep the masses in line: “I do not believe that the intellectual elements in the Labour Party will ever exercise adequate control; too much will always be decided by those who do not know at all what they are talking about.… I incline to believe that the Liberal Party is still the best instrument of future progress.”55 Note that Hayek, whose political point of view was quite different from Keynes’s, also worried a great deal about handing power to the Labour Party—or to the Swedish Social Democrats. In his view, there was a danger that both would quickly more toward authoritarian rule and trample individual liberties underfoot; he therefore did his best to warn his intellectual friends against the dangerous sirens to which he believed they had succumbed.56

FIG. 15.13. The electoral left in Europe and the United States, 1945–2020: From the workers’ party to the party of the highly educated

Interpretation: In the period 1950–1970, the vote for the Democratic Party in the United States, for the parties of the left (Socialists-Communists-Radicals-Greens) in France, and for the Labour Party in the United Kingdom was associated with less educated voters; in the period 1990–2010, it came to be associated with more highly educated voters. The British evolution slightly lags the French and American but goes in the same direction. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

By contrast, recall that the Labour sociologist Michael Young worried in the 1950s that his party, by failing to undertake a sufficiently ambitious egalitarian reform of Britain’s horribly hierarchical educational system, would eventually alienate the less educated classes and become a party of “technicians” pitted against the masses of “populists.” But even he never imagined that the Labour Party would ultimately displace the Conservatives as the party of the highly educated.57

On the “Brahmin Left” and the “Merchant Right” in the United Kingdom

Somewhat later than in France and the United States, the Labour Party thus also became a “Brahmin left” of a sort, racking up its best results among the highly educated. I turn now to the evolution of electoral cleavages as a function of income. In the period 1950–1980, we find a very marked income cleavage in the United Kingdom: the lower a voter’s income, the more likely that voter was to vote for Labour, while the top income deciles voted heavily Conservative. This disparity was particularly clear in the 1979 election, which Margaret Thatcher won on a platform of anti-union measures, privatizations, and tax cuts for top earners in a time of economic crisis and high inflation. According to the available data, fewer than 20 percent of voters in the top income decile voted Labour in 1979, compared with 25 percent in 1955 and 1970. In every case the Conservatives won 75–80 percent of the vote in the top income decile (Fig. 15.14).

Compared to France, the income cleavage has historically been more pronounced in the United Kingdom. In France, the profile of the vote for parties of the left (Socialists, Communists, Radicals, and Greens) is relatively flat through the bottom 90 percent of the income distribution, falling off only in the top decile.58 If we look at the detailed survey data by sector of activity, we find that the difference is explained mainly by the fact that in France there are more self-employed individuals, and especially farmers, whose income is not always very high but who often own professional assets and are wary of the left-wing parties. In the United Kingdom, the agricultural and self-employment sectors shrank earlier than in France, and most workers are wage earners; hence the classist cleavage is more pronounced, especially with respect to income. This also explains why the educational cleavage was historically less pronounced and turned around earlier in France than in the United Kingdom: the self-employed (particularly self-employed farmers) are a large and relatively less educated group that has never voted strongly for the left.

FIG. 15.14. Political conflict and income in the United Kingdom, 1955–2017

Interpretation: The profile of the Labour vote as a function of income decile is strongly decreasing, particularly in the top income decile, especially in the period 1950–1990. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

As for income effects, we also find a fairly clear temporal evolution in the United Kingdom starting in the 1980s–1990s, exactly the same as in France and the United States. In particular, higher-income voters voted more heavily for Tony Blair’s New Labour in the period 1997–2005 than they had voted for Labour previously. That may seem logical, given that New Labour also attracted more and more votes among college-educated people and its fiscal policies were relatively favorable to high earners. Just as the Clinton (1992–2000) and Obama (2008–2016) administrations had validated and perpetuated the Reagan reforms of the 1980s, New Labour governments in the period 1997–2010 largely validated and perpetuated the fiscal reforms of the Thatcher era.59 Compared with the Conservative Thatcher and Major governments, however, the New Labour Blair and Brown governments invested more public funds in the educational system. But they also sharply increased university tuitions when they took office, a move that was hardly favorable to students of modest background.60 Ultimately, these policies point toward a rapprochement of the “Brahmin left” and “merchant right” in the United Kingdom.

The change of Labour Party leadership eventually shook things up, however. In the 2015 and 2017 legislative elections, we find that higher-income voters were much more likely to vote Conservative so that the gap between the educational effect and the income effect increased (Fig. 15.15).61 This can be explained in various ways, and the available data do not allow us to choose one explanation over another. First, Labour’s policy preferences changed significantly after Jeremy Corbyn was elected party leader in 2015. The party now envisions more redistributive tax measures than in the New Labour era and has turned to the left in other ways as well. This may have frightened wealthier voters. On the other hand, the Labour platform now includes policies that may be more appealing to voters from lower income groups. These include measures favorable to unions, giving more power to worker representatives and providing for power sharing between workers and shareholders on boards of directors, comparable with German and Nordic co-management, which has never been tried in the United Kingdom.62 Finally, Labour is now calling for completely free higher education (as in Germany and Sweden)—a complete about-face from the tuition increases New Labour enacted in 1997 and 2010. For obvious reasons, this proposal seems to have been particularly popular among young working-class voters in the 2017 election.63

FIG. 15.15. Social cleavages and political conflict: United Kingdom, 1955–2017

Interpretation: In the period 1950–1990 the Labour vote was associated with low levels of education, income, and wealth; since 1990 it has come to be associated with high levels of education. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

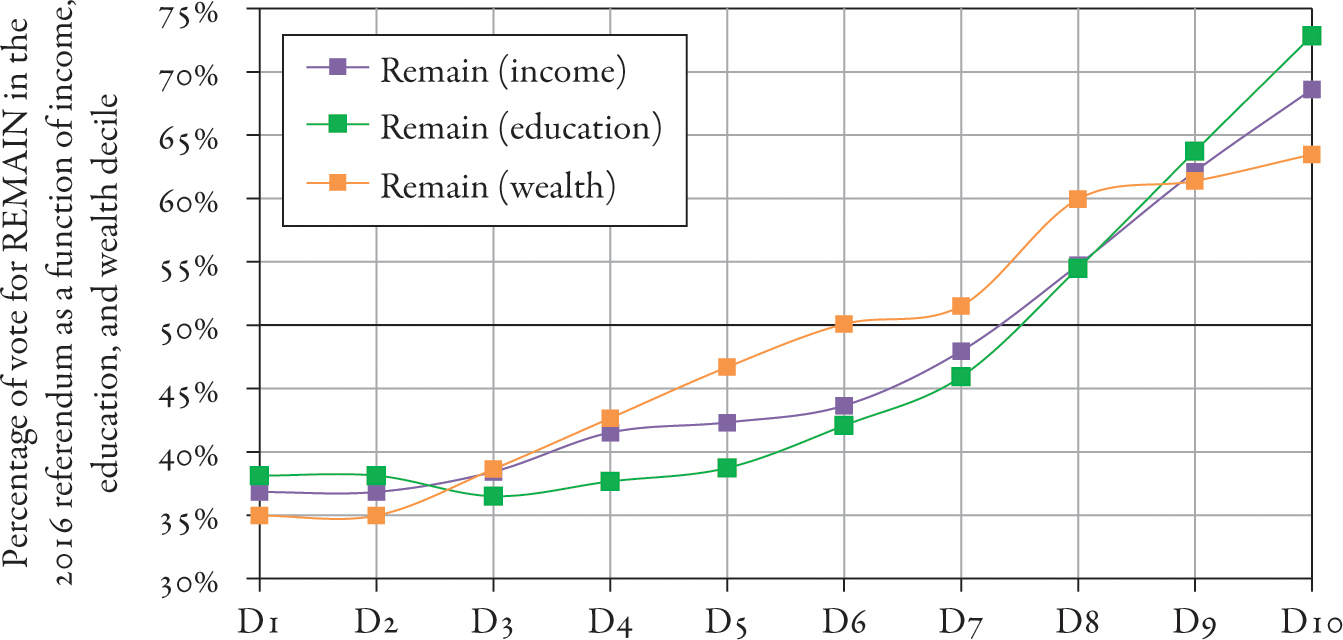

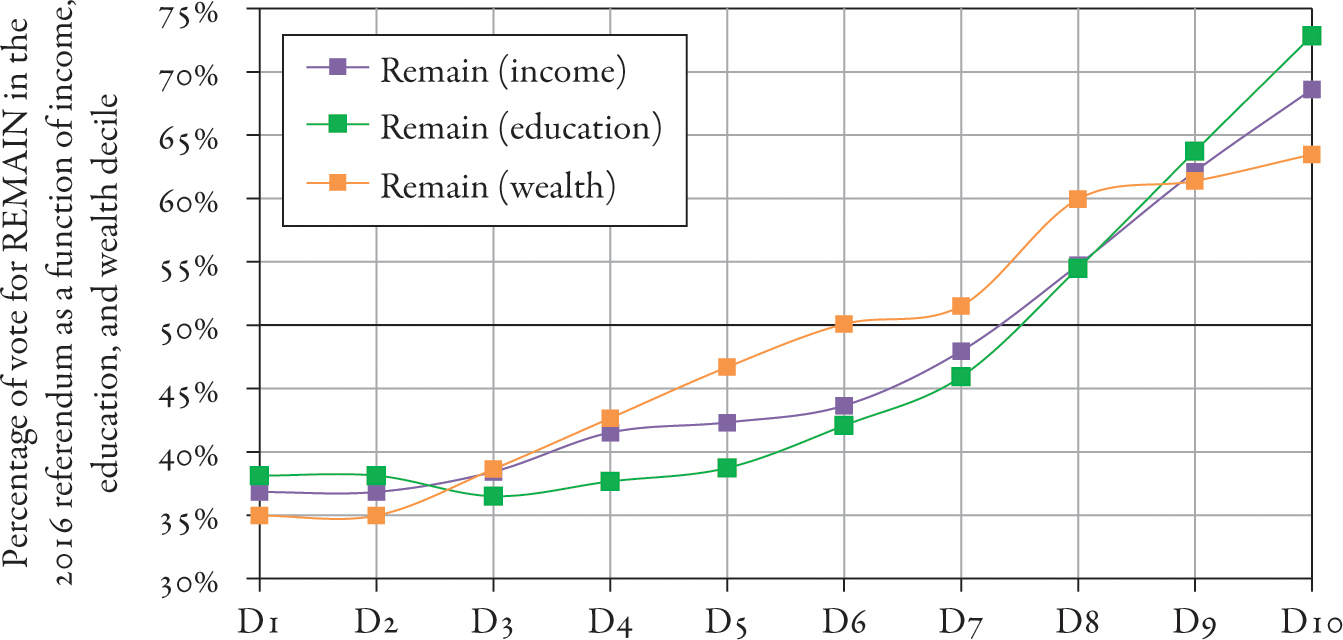

We must also consider the effect of the 2016 Brexit referendum, in which 52 percent of the British electorate voted to leave the European Union, on the 2017 parliamentary elections. Although Corbyn’s personal position on Brexit may have been ambiguous or lukewarm, the Labour Party officially favored “Remain.” This was also the position of more than 90 percent of Labour MPs, compared with roughly half of Conservative MPs. In any case, the Labour vote overall was more pro-Europe than the Conservative vote (the Tories having initiated the 2016 referendum). This may have been one reason for the particularly high vote for Labour in 2017 among those with university degrees, a large majority of whom opposed Brexit. Note that higher-income voters, who were also troubled by Brexit, nevertheless fled Labour in 2017 probably because the left turn instigated by Corbyn worried them even more than Brexit did. In the end, the vote for Labour in 2017 was highest among middle-income people with university degrees. I will say more later about the structure of the Brexit vote and the future of the European Union, which is becoming the central political-ideological issue both in the United Kingdom and on the continent.

To sum up, if we compare the general evolution of the cleavages observed in various countries as a function of education, income, and wealth, we find not only striking commonalities but also significant differences, especially at the very end of the period. In the United Kingdom, the divergence of the educational effect from the income and wealth effects increases in 2015–2017 (Fig. 15.15). By contrast, in the 2016 US presidential election, the income and wealth effects converge with the educational effect: wealthier and higher-income voters join those with higher degrees in voting Democratic (Fig. 15.6). Clearly, the stark contrast between the strategies of the Labour Party and the Democratic Party play an important role. Labour’s pro-redistribution turn under Corbyn drove higher-income voters away from the party and attracted more modest-income voters, whereas the centrist line of the Democratic Party under Hillary Clinton had the opposite effect. If Democratic primary voters had chosen Sanders rather than Clinton, the vote structure might have been closer to that observed in the United Kingdom. France represents a third possibility. Because of its two-round voting system and historically fragmented political parties, the more prosperous elements of the old electoral left and right joined together in a new coalition of the highly educated with the wealthiest and highest paid, enabling Emmanuel Macron to win the presidency in 2017.64

These three situations are quite different from one another. They are interesting because they demonstrate that nothing is written in advance. In particular, everything depends on the mobilization strategies of the parties and the political-ideological balance of power. Admittedly, the underlying trends in all three countries are similar because the classist left-right party systems of the postwar era have given way to a system of dual elites consisting of a “Brahmin left” attractive to the highly educated and a “merchant right” attractive the wealthy and highly paid. But within this general pattern, many distinct trajectories are possible because the new system is extremely fragile and unstable. The “Brahmin left” is divided between pro-redistribution and pro-market wings, and the “merchant right” is just as divided between a faction tempted by the nationalist or nativist line and another that would prefer to maintain a primarily pro-business, pro-market orientation. Depending on which tendency wins out in each camp or on what new syntheses emerge, different trajectories are possible. The effects of turning one way or another are potentially long lasting. I will come back to this in Chapter 16 when I look at other countries and other electoral configurations.

The Rise of Identity Cleavages in the Postcolonial United Kingdom

We turn now to the question of identity cleavages in the United Kingdom. At first sight, the data and the realities they reflect seem relatively similar to the French case. Let us begin by looking at data on voters’ declared religions, which can be found in British postelection surveys since the 1950s. With this information we are able to follow the evolution of the religious cleavage in parliamentary elections from 1955 to 2017.

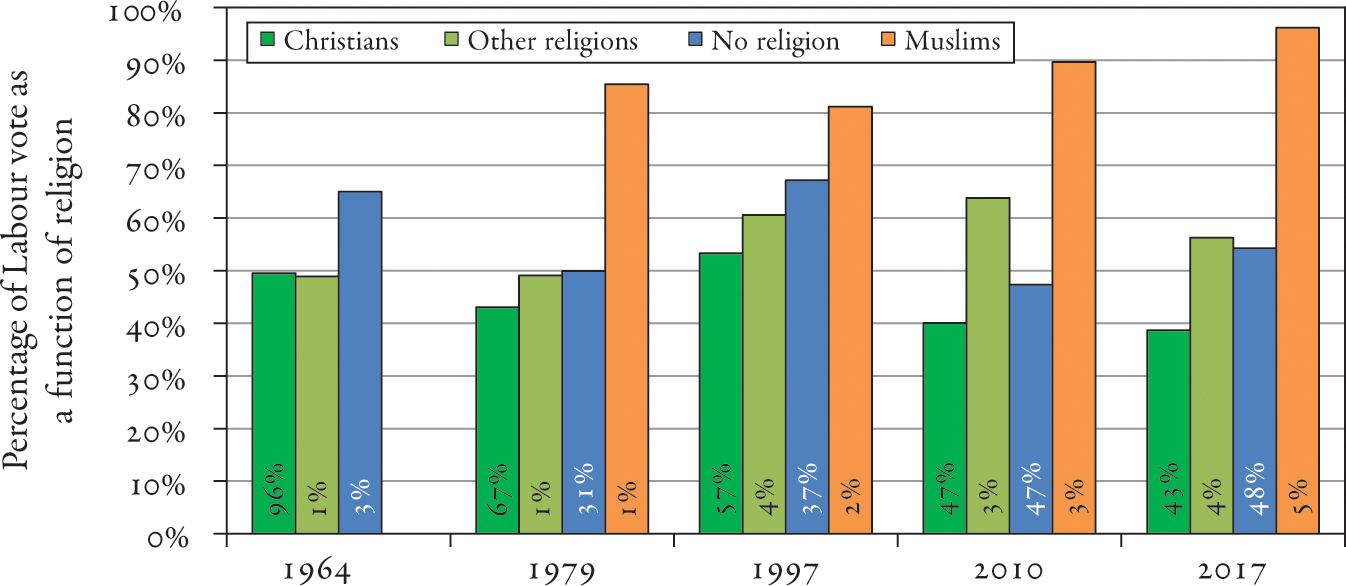

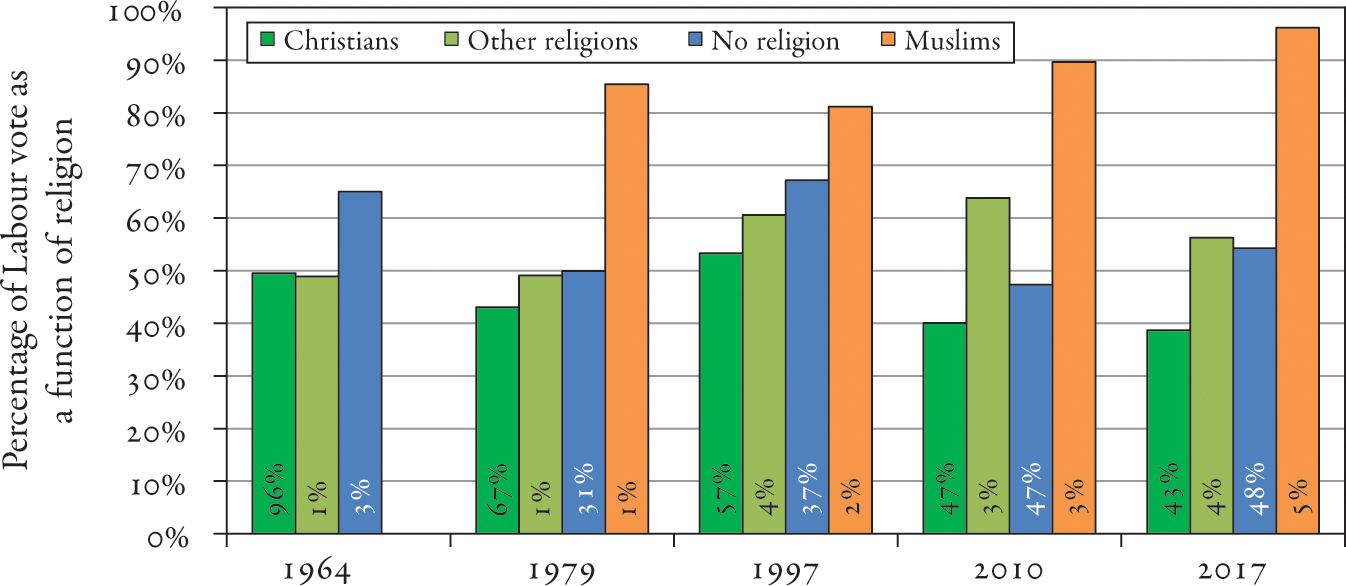

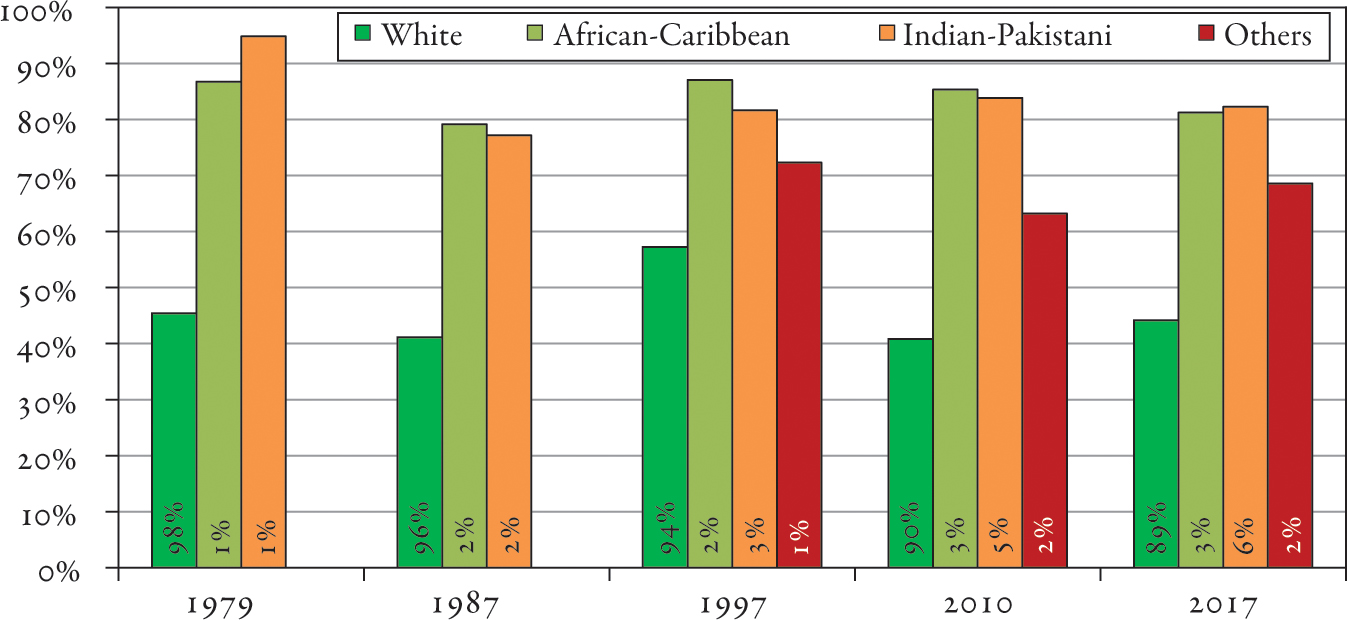

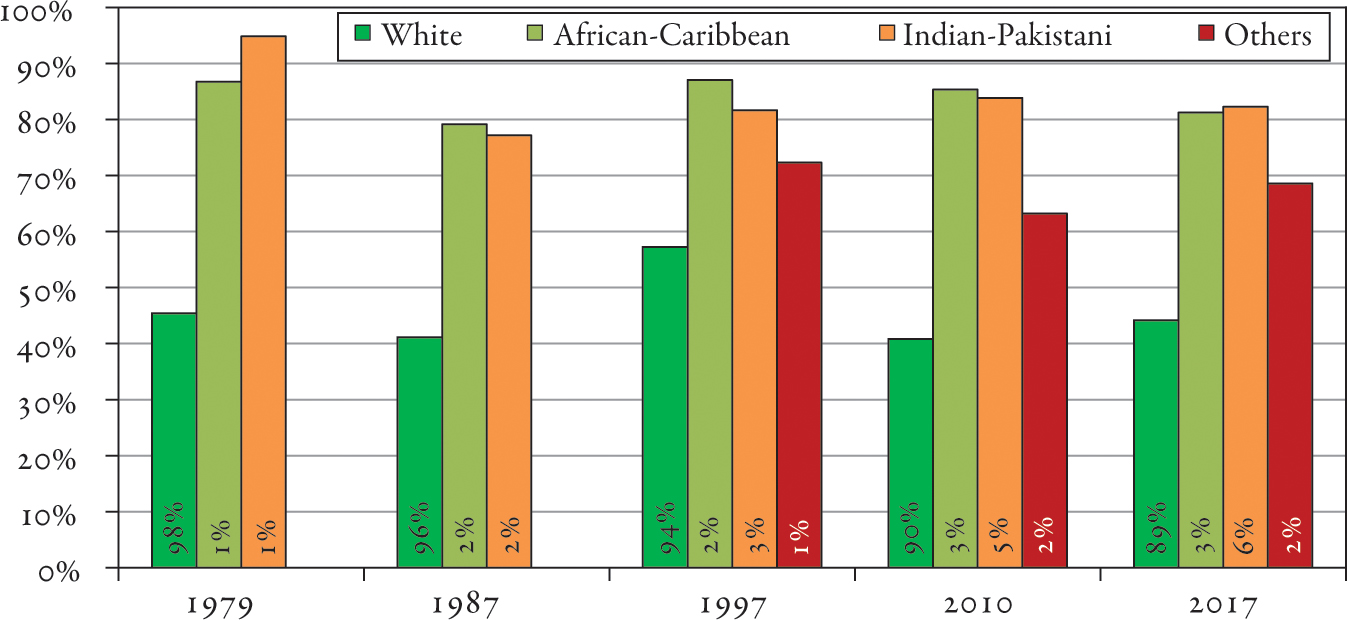

Our first finding is that the United Kingdom, like France, was largely a country of one religion and one ethnicity until the 1960s. In the 1964 elections, 96 percent of the electorate professed to belong to one Christian denomination or another; 3 percent declared no religion, and only 1 percent claimed some other religion (mostly Jews, with a very small number of Muslims, Hindus, and Buddhists).65 The proportion of individuals declaring “no religion” grew dramatically from the late 1960s on, however, rising from 3 percent of the electorate in 1964 to 31 percent in 1979 and 48 percent in 2017. The progression was even more rapid than in France where the proportion of voters with no declared religion rose from 6 percent in 1967 to 36 percent in 2017.66 Importantly, the “no religion” grew much more than in the United States, which in general remains significantly more religious than Europe.67