Introduction

Every human society must justify its inequalities: unless reasons for them are found, the whole political and social edifice stands in danger of collapse. Every epoch therefore develops a range of contradictory discourses and ideologies for the purpose of legitimizing the inequality that already exists or that people believe should exist. From these discourses emerge certain economic, social, and political rules, which people then use to make sense of the ambient social structure. Out of the clash of contradictory discourses—a clash that is at once economic, social, and political—comes a dominant narrative or narratives, which bolster the existing inequality regime.

In today’s societies, these justificatory narratives comprise themes of property, entrepreneurship, and meritocracy: modern inequality is said to be just because it is the result of a freely chosen process in which everyone enjoys equal access to the market and to property and automatically benefits from the wealth accumulated by the wealthiest individuals, who are also the most enterprising, deserving, and useful. Hence modern inequality is said to be diametrically opposed to the kind of inequality found in premodern societies, which was based on rigid, arbitrary, and often despotic differences of status.

The problem is that this proprietarian* and meritocratic narrative, which first flourished in the nineteenth century after the collapse of the Old Regime and its society of orders* and which was radically revised for a global audience at the end of the twentieth century following the fall of Soviet communism and the triumph of hypercapitalism, is looking more and more fragile. From it a variety of contradictions have emerged—contradictions which take very different forms in Europe and the United States, in India and Brazil, in China and South Africa, in Venezuela and the Middle East. And yet today, two decades into the twenty-first century, the various trajectories* of these different countries are increasingly interconnected, their distinctive individual histories notwithstanding. Only by adopting a transnational perspective can we hope to understand the weaknesses of these narratives and begin to construct an alternative.

Indeed, socioeconomic inequality has increased in all regions of the world since the 1980s. In some cases it has become so extreme that it is difficult to justify in terms of the general interest. Nearly everywhere a gaping chasm divides the official meritocratic discourse from the reality of access to education and wealth for society’s least favored classes. The discourse of meritocracy and entrepreneurship often seems to serve primarily as a way for the winners in today’s economy to justify any level of inequality whatsoever while peremptorily blaming the losers for lacking talent, virtue, and diligence. In previous inequality regimes, the poor were not blamed for their own poverty, or at any rate not to the same extent; earlier justificatory narratives stressed instead the functional complementarity of different social groups.

Modern inequality also exhibits a range of discriminatory practices based on status, race, and religion, practices pursued with a violence that the meritocratic fairy tale utterly fails to acknowledge. In these respects, modern society can be as brutal as the premodern societies from which it likes to distinguish itself. Consider, for example, the discrimination faced by the homeless, immigrants, and people of color. Think, too, of the many migrants who have drowned while trying to cross the Mediterranean. Without a credible new universalistic and egalitarian narrative, it is all too likely that the challenges of rising inequality, immigration, and climate change will precipitate a retreat into identitarian* nationalist politics based on fears of a “great replacement” of one population by another. We saw this in Europe in the first half of the twentieth century, and it seems to be happening again in various parts of the world in the first decades of the twenty-first century.

It was World War I that spelled the end of the so-called Belle Époque (1880–1914), which was belle only when compared with the explosion of violence that followed. In fact, it was belle primarily for those who owned property, especially if they were white males. If we do not radically transform the present economic system to make it less inegalitarian, more equitable, and more sustainable, xenophobic “populism” could well triumph at the ballot box and initiate changes that will destroy the global, hypercapitalist, digital economy that has dominated the world since 1990.

To avoid this danger, historical understanding remains our best tool. Every human society needs to justify its inequalities, and every justification contains its share of truth and exaggeration, boldness and cowardice, idealism and self-interest. For the purposes of this book, an inequality regime will be defined as a set of discourses and institutional arrangements intended to justify and structure the economic, social, and political inequalities of a given society. Every such regime has its weaknesses. In order to survive, it must permanently redefine itself, often by way of violent conflict but also by availing itself of shared experience and knowledge. The subject of this book is the history and evolution of inequality regimes. By bringing together historical data bearing on societies of many different types, societies which have not previously been subjected to this sort of comparison, I hope to shed light on ongoing transformations in a global and transnational perspective.

From this historical analysis one important conclusion emerges: what made economic development and human progress possible was the struggle for equality and education and not the sanctification of property, stability, or inequality. The hyper-inegalitarian narrative that took hold after 1980 was in part a product of history, most notably the failure of communism. But it was also the fruit of ignorance and of disciplinary division in the academy. The excesses of identity politics and fatalist resignation that plague us today are in large part consequences of that narrative’s success. By turning to history from a multidisciplinary perspective, we can construct a more balanced narrative and sketch the outlines of a new participatory socialism for the twenty-first century. By this I mean a new universalistic egalitarian narrative, a new ideology of equality, social ownership, education, and knowledge and power sharing. This new narrative presents a more optimistic picture of human nature than did its predecessors—and not only more optimistic but also more precise and convincing because it is more firmly rooted in the lessons of global history. Of course, it is up to each of us to judge the merits of these tentative and provisional lessons, to rework them as necessary, and to carry them forward.

What Is an Ideology?

Before I explain how this book is organized, I want to discuss the principal sources on which I rely and how the present work relates to Capital in the Twenty-First Century. But first I need to say a few words about the notion of ideology as I use it in this study.

I use “ideology” in a positive and constructive sense to refer to a set of a priori plausible ideas and discourses describing how society should be structured. An ideology has social, economic, and political dimensions. It is an attempt to respond to a broad set of questions concerning the desirable or ideal organization of society. Given the complexity of the issues, it should be obvious that no ideology can ever command full and total assent: ideological conflict and disagreement are inherent in the very notion of ideology. Nevertheless, every society must attempt to answer questions about how it should be organized, usually on the basis of its own historical experience but sometimes also on the experiences of other societies. Individuals will usually also feel called on to form opinions of their own on these fundamental existential issues, however vague or unsatisfactory they may be.

What are these fundamental issues? One is the question of what the nature of the political regime should be. By “political regime” I mean the set of rules describing the boundaries of the community and its territory, the mechanisms of collective decision making, and the political rights of members. These rules govern forms of political participation and specify the respective roles of citizens and foreigners as well as the functions of executives and legislators, ministers and kings, parties and elections, empires and colonies.

Another fundamental issue has to do with the property regime, by which I mean the set of rules describing the different possible forms of ownership as well as the legal and practical procedures for regulating property relations between different social groups. Such rules may pertain to private or public property, real estate, financial assets, land or mineral resources, slaves or serfs, intellectual and other immaterial forms of property, and relations between landlords and tenants, nobles and peasants, masters and slaves, or shareholders and wage earners.

Every society, every inequality regime, is characterized by a set of more or less coherent and persistent answers to these questions about its political and property regimes. These two sets of answers are often closely related because they depend in large part on some theory of inequality between different social groups (whether real or imagined, legitimate or illegitimate). The answers generally imply a range of other intellectual and institutional commitments: for instance, commitments to an educational regime (that is, the rules governing institutions and organizations responsible for transmitting spiritual values, knowledge, and ideas, including families, churches, parents, and schools and universities) and a tax regime (that is, arrangements for providing states or regions; towns or empires; and social, religious, or other collective organizations with adequate resources). The answers to these questions can vary widely. People can agree about the political regime but not the property regime or about certain fiscal or educational arrangements but not others. Ideological conflict is almost always multidimensional, even if one axis takes priority for a time, giving the illusion of majoritarian consensus allowing broad collective mobilization and historical transformations of great magnitude.

Borders and Property

To simplify, we can say that every inequality regime, every inegalitarian ideology, rests on both a theory of borders and a theory of property.

The border question is of primary importance. Every society must explain who belongs to the human political community it comprises and who does not, what territory it governs under what institutions, and how it will organize its relations with other communities within the universal human community (which, depending on the ideology involved, may or may not be explicitly acknowledged). The border question and the political regime question are of course closely linked. The answer to the border question also has significant implications for social inequality, especially between citizens and noncitizens.

The property question must also be answered. What is a person allowed to own? Can one person own others? Can he or she own land, buildings, firms, natural resources, knowledge, financial assets, and public debt? What practical guidelines and laws should govern relations between owners of property and nonowners? How should ownership be transmitted across generations? Along with the educational and fiscal regime, the property regime determines the structure and evolution of social inequality.

In most premodern societies, the questions of the political regime and the property regime are intimately related. In other words, power over individuals and power over things are not independent. Here, “things” refers to possessed objects, which may be persons in the case of slavery. Furthermore, power over things may imply power over persons. This is obviously true in slave societies, where the two questions essentially merge into one: some individuals own others and therefore also rule over them.

The same is true, but in more subtle fashion, in what I call ternary or “trifunctional” societies (that is, societies divided into three functional classes—a clerical and religious class, a noble and warrior class, and a common and laboring class). In this historical form, which we find in most premodern civilizations, the two dominant classes are both ruling classes, in the senses of exercising the regalian powers of security and justice, and property-owning classes. For centuries, the “landlord” was also the “ruler” (seigneur) of the people who lived and worked on his land, just as much as he was the seigneur (“lord”) of the land itself.

By contrast, ownership (or proprietarian) societies* of the sort that flourished in Europe in the nineteenth century drew a sharp distinction between the property question (with universal property rights theoretically open to all) and the power question (with the centralized state claiming a monopoly of regalian rights*). The political regime and the property regime were nevertheless closely related, in part because political rights were long restricted to property owners and in part because constitutional restrictions then and now severely limited the possibility for political majorities to modify the property regime by legal and peaceful means.

As we shall see, political and property regimes have remained inextricably intertwined from premodern* ternary* and slave societies to modern postcolonial and hypercapitalist ones, including, along the way, the communist and social-democratic societies that arose in reaction to the crises of inequality and identity that ownership society provoked.

To analyze these historical transformations I therefore rely on the notion of an “inequality regime”* which encompasses both the political regime and the property regime (as well as the educational and fiscal regimes) and clarifies the relation between them. To illustrate the persistent structural links between the political regime and the property regime in today’s world, consider the absence of any democratic mechanism that would allow a majority of citizens of the European Union (and a fortiori citizens of the world) to adopt a common tax or a redistributive or developmental scheme. This is because each member state, no matter how small its population or what benefits it derives from commercial and financial integration, has the right to veto all forms of fiscal legislation.

More generally, inequality today is strongly influenced by the system of borders and national sovereignty, which determines the allocation of social and political rights. This has given rise to intractable multidimensional ideological conflicts over inequality, immigration, and national identity, conflicts that have made it very difficult to achieve majority coalitions capable of countering the rise of inequality. Specifically, ethno-religious and national cleavages often prevent people of different ethnic and national origins from coming together politically, thus strengthening the hand of the rich and contributing to the growth of inequality. The reason for this failure is the lack of an ideology capable of persuading disadvantaged social groups that what unites them is more important than what divides them. I will examine these issues in due course. Here I want simply to emphasize the fact that political and property regimes have been intimately related for a very long time. This durable structural relationship cannot be properly analyzed without adopting a long-run transnational historical perspective.

Taking Ideology Seriously

Inequality is neither economic nor technological; it is ideological and political. This is no doubt the most striking conclusion to emerge from the historical approach I take in this book. In other words, the market and competition, profits and wages, capital and debt, skilled and unskilled workers, natives and aliens, tax havens and competitiveness—none of these things exist as such. All are social and historical constructs, which depend entirely on the legal, fiscal, educational, and political systems that people choose to adopt and the conceptual definitions they choose to work with. These choices are shaped by each society’s conception of social justice and economic fairness and by the relative political and ideological power of contending groups and discourses. Importantly, this relative power is not exclusively material; it is also intellectual and ideological. In other words, ideas and ideologies count in history. They enable us to imagine new worlds and different types of society. Many paths are possible.

This approach runs counter to the common conservative argument that inequality has a basis in “nature.” It is hardly surprising that the elites of many societies, in all periods and climes, have sought to “naturalize” inequality. They argue that existing social disparities benefit not only the poor but also society as a whole and that any attempt to alter the existing order of things will cause great pain. History proves the opposite: inequality varies widely in time and space, in structure as well as magnitude. Changes have occurred rapidly in ways that contemporaries could not have imagined only a short while before they came about. Misfortune did sometimes follow. Broadly speaking, however, political processes, including revolutionary transformations, that led to a reduction of inequality proved to be immensely successful. From them came our most precious institutions—those that have made human progress a reality, including universal suffrage, free and compulsory public schools, universal health insurance, and progressive taxation. In all likelihood the future will be no different. The inequalities and institutions that exist today are not the only ones possible, whatever conservatives may say to the contrary. Change is permanent and inevitable.

Nevertheless, the approach taken in this book—based on ideologies, institutions, and the possibility of alternative pathways—also differs from approaches sometimes characterized as “Marxist,” according to which the state of the economic forces and relations of production determines a society’s ideological “superstructure” in an almost mechanical fashion. In contrast, I insist that the realm of ideas, the political-ideological sphere, is truly autonomous. Given an economy and a set of productive forces in a certain state of development (supposing one can attach a definite meaning to those words, which is by no means certain), a range of possible ideological, political, and inequality regimes always exists. For instance, the theory that holds that a transition from “feudalism” to “capitalism” occurred as a more or less mechanical response to the Industrial Revolution cannot explain the complexity and multiplicity of the political and ideological pathways we actually observe in different countries and regions. In particular, it fails to explain the differences that exist between and within colonizing and colonized regions. Above all, it fails to impart lessons useful for understanding subsequent stages of history. When we look closely at what followed, we find that alternatives always existed—and always will. At every level of development, economic, social, and political systems can be structured in many different ways; property relations can be organized differently; different fiscal and educational regimes are possible; problems of public and private debt can be handled differently; numerous ways to manage relations between human communities exist; and so on. There are always several ways of organizing a society and its constitutive power and property relations. More specifically, today, in the twenty-first century, property relations can be organized in many ways. Clearly stating the alternatives may be more useful in transcending capitalism than simply threatening to destroy it without explaining what comes next.

The study of these different historical pathways, as well as of the many paths not taken, is the best antidote to both the conservatism of the elite and the alibis of would-be revolutionaries who argue that nothing can be done until the conditions for revolution are ripe. The problem with these alibis is that they indefinitely defer all thinking about the postrevolutionary future. What this usually means in practice is that all power is granted to a hypertrophied state, which may turn out to be just as dangerous as the quasi-sacred property relations that the revolution sought to overthrow. In the twentieth century such thinking did considerable human and political damage for which we are still paying the price. Today, the postcommunist societies of Russia, China, and to a certain extent Eastern Europe (despite their different historical trajectories) have become hypercapitalism’s staunchest allies. This is a direct consequence of the disasters of Stalinism and Maoism and the consequent rejection of all egalitarian internationalist ambitions. So great was the communist disaster that it overshadowed even the damage done by the ideologies of slavery, colonialism, and racialism and obscured the strong ties between those ideologies and the ideologies of ownership and hypercapitalism—no mean feat.

In this book I take ideology very seriously. I try to reconstruct the internal coherence of different types of ideology, with special emphasis on six main categories which I will call proprietarian, social-democratic, communist, trifunctional,* slaveist (esclavagiste), and colonialist ideologies. I start with the hypothesis that every ideology, no matter how extreme it may seem in its defense of inequality, expresses a certain idea of social justice. There is always some plausible basis for this idea, some sincere and consistent foundation, from which it is possible to draw useful lessons. But we cannot do this unless we take a concrete rather than an abstract (which is to say, ahistorical and noninstitutional) approach to the study of political and ideological structures. We must look at concrete societies and specific historical periods and at specific institutions defined by specific forms of property and specific fiscal and educational regimes. These must be rigorously analyzed. We must not shrink from investigating legal systems, tax schedules, and educational resources—the conditions and rules under which societies function. Without these, institutions and ideologies are mere empty shells, incapable of effecting real social change or inspiring lasting allegiance.

I am of course well aware that the word “ideology” can be used pejoratively, sometimes with good reason. Dogmatic ideas divorced from facts are frequently characterized as ideological. Yet often it is those who claim to be purely pragmatic who are in fact most “ideological” (in the pejorative sense): their claim to be post-ideological barely conceals their disdain for evidence, historical ignorance, distorting biases, and class interests. This book will therefore lean heavily on “facts.” I will discuss the history of inequality in several societies, partly because this was my original specialty and partly because I am convinced that unbiased examination of the available sources is the only way to make progress. In so doing I will compare societies which are very different from one another. Some are even said to be “exceptional” and therefore unsuitable for comparative study, but this is incorrect.

I am well placed to know, however, that the available sources are never sufficient to resolve every dispute. From “facts” alone we will never be able to deduce the ideal political regime or property regime or fiscal or educational regime. Why? Because “facts” are largely the products of institutions (such as censuses, surveys, tax records, and so on). Societies create social, fiscal, and legal categories to describe, measure, and transform themselves. Hence “facts” are themselves constructs. To appreciate them properly we must understand their context, which consists of complex, overlapping, self-interested interactions between the observational apparatus and the society under study. This of course does not mean that these cognitive constructs have nothing to teach us. It means, rather, that to learn from them, we must take this complexity and reflexivity into account.

Furthermore, the questions that interest us, which pertain to the nature of the ideal social, economic, and political organization, are far too complex to allow answers to emerge from a simple “objective” examination of the “facts,” which inevitably reflect the limitations of past experiences and the incompleteness of our knowledge and of the deliberative processes to which we were exposed. Finally, it is entirely conceivable that the “ideal” regime (however we interpret the word “ideal”) is not unique and depends on specific characteristics of each society.

Collective Learning and the Social Sciences

Nevertheless, my position is not one of indiscriminate relativism. It is too easy for the social scientist to avoid taking a stand. So I will eventually make my position clear, especially in the final part of the book, but in so doing I will attempt to explain how and why I reached my conclusions.

Social ideologies usually evolve in response to historical experience. For instance, the French Revolution stemmed in part from the injustices and frustrations of the Ancien Régime. The Revolution in turn brought about changes that permanently altered perceptions of the ideal inequality regime as various social groups judged the success or failure of revolutionary experiments with different forms of political organization, property regimes, and social, fiscal, and educational systems. What was learned from this experience inevitably influenced future political transformations and so on down the line. Each nation’s political and ideological trajectory can be seen as a vast process of collective learning and historical experimentation. Conflict is inherent in the process because different social and political groups have not only different interests and aspirations but also different memories. Hence they interpret past events differently and draw from them different implications regarding the future. From such learning experiences, national consensus on certain points can nevertheless emerge, at least for a time.

Though partly rational, these collective learning processes nevertheless have their limits. Nations tend to have short memories (people often forget their own country’s experiences after a few decades or else remember only scattered bits, seldom chosen at random). Worse than that, memory is usually strictly nationalistic. Perhaps that is putting it too strongly: every country occasionally learns from the experiences of other countries, whether indirectly or through direct contact (in the form of war, colonization, occupation, or treaty—forms of learning that may be neither welcome nor beneficial). For the most part, however, nations form their visions of the ideal political or property regime or just legal, fiscal, or educational system from their own experiences and are almost completely unaware of the experiences of other countries, particularly when they are geographically remote or thought to belong to a distinct civilization or religious or moral tradition or, again, when contact with the other has been violent (which can reinforce the sense of radical foreignness). More generally, collective learning experiences are often based on relatively crude or imprecise notions of the institutional arrangements that exist in other societies (or even within the same country or in neighboring countries). This is true not only in the political realm but also in regard to legal, fiscal, and educational institutions. The usefulness of the lessons derived from such collective learning experiences is therefore somewhat limited.

This limitation is not inevitable, however. Many factors can enhance the learning process: schools and books, immigration and intermarriage, parties and trade unions, travel and encounters, newspapers and other media, to name a few. The social sciences can also play a part. I am convinced that social scientists can contribute to the understanding of ongoing changes by carefully comparing the histories of countries with different cultural traditions, systematically exploiting all available resources, and studying the evolution of inequality and of political and ideological regimes in different parts of the world. Such a comparative, historical, transnational approach can help us to form a more accurate picture of what a better political, economic, and social organization might look like and especially what a better global society might look like, since the global community is the one political community to which we all belong. Of course, I do not claim that the conclusions I offer throughout the book are the only ones possible, but they are, in my view, the best conclusions we can draw from the sources I have explored. I will try to explain in detail which events and comparisons I found most persuasive in reaching these conclusions. I will not hide the uncertainties that remain. Obviously, however, these conclusions depend on the very limited state of our present knowledge. This book is but one small step in a vast process of collective learning. I am impatient to discover what the next steps in the human adventure will be.

I hasten to add, for the benefit of those who lament the rise of inequality and of identity politics as well as for those who think that I protest too much, that this book is in no way a book of lamentations. I am an optimist by nature, and my primary goal is to seek solutions to our common problems. Human beings have demonstrated an astonishing capacity to imagine new institutions and develop new forms of cooperation, to forge bonds among millions (or hundreds of millions or even billions) of people who have never met and will never meet and who might well choose to annihilate one another rather than live together in peace. This is admirable. What is more, societies can accomplish these feats even though we know little about what an ideal regime might look like and therefore about what rules are justifiable. Nevertheless, our ability to imagine new institutions has its limits. We therefore need the assistance of rational analysis. To say that inequality is ideological and political rather than economic or technological does not mean that it can be eliminated by a wave of some magic wand. It means, more modestly, that we must take seriously the ideological and institutional diversity of human society. We must beware of anyone who tries to naturalize inequality or deny the existence of alternative forms of social organization. It means, too, that we must carefully study in detail the institutional arrangements and legal, fiscal, and educational systems of other countries, for it is these details that determine whether cooperation succeeds or fails and whether equality increases or decreases. Good will is not enough without solid conceptual and institutional underpinnings. If I can communicate to you, the reader, a little of my educated amazement at the successes of the past and persuade you that knowledge of history and economics is too important to leave to historians and economists, then I will have achieved my goal.

The Sources Used in This Book: Inequalities and Ideologies

This book is based on historical sources of two kinds: first, sources that enable us to measure the evolution of inequality in a multidimensional historical and comparative perspective (including inequalities of income, wages, wealth, education, gender, age, profession, origin, religion, race, status, etc.) and second, sources that allow us to study changes in ideology, political beliefs, and representations of inequality and of the economic, social, and political institutions that shape them.

Regarding inequality, I rely in particular on the data collected in the World Inequality Database (WID.world). This project represents the combined effort of more than a hundred researchers in eighty countries around the world. It is currently the largest database available for the historical study of wealth and income inequality both within and between countries. The WID.world project grew out of work I did with Anthony Atkinson and Emmanuel Saez in the early 2000s, which sought to extend and generalize research begun in the 1950s and 1970s by Atkinson, Simon Kuznets, and Alan Harrison.1 This project is based on systematic comparison of available sources, including national accounts data, survey data, and fiscal and estate data. With these data it is generally possible to go back as far as the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when many countries established progressive income and estate taxes. From the same data we can also infer conclusions about the distribution of wealth (taxes invariably give rise to new sources of knowledge and not only to tax receipts and popular discontent). For some countries we can push the limits of our knowledge back as far as the late eighteenth or early nineteenth centuries. This is true, for instance, of France, where the Revolution established an early version of a unified system of property and estate records. By drawing on this research I was able to set the post-1980 rise of inequality in a long-term historical perspective. This spurred a global debate on inequality, as the interest aroused by the publication in 2013 of Capital in the Twenty-First Century illustrates. The World Inequality Report 2018 continued this debate.2 People want to participate in the democratic process and therefore demand a more democratic diffusion of economic knowledge, as the enthusiastic reception of the WID.world project shows. As people become better educated and informed, economic and financial issues can no longer be left to a small group of experts whose competence is, in any case, dubious. It is only natural for more and more citizens to want to form their own opinions and participate in public debate. The economy is at the heart of politics; responsibility for it cannot be delegated, any more than democracy itself can.

The available data on inequality are unfortunately incomplete, largely because of the difficulty of gaining access to fiscal, administrative, and banking records in many countries. There is a general lack of transparency in economic and financial matters. With the help of hundreds of citizens, researchers, and journalists in many countries, I was able to gain access to previously closed sources in Brazil, India, South Africa, Tunisia, Lebanon, Ivory Coast, Korea, Taiwan, Poland, and Hungary and, to a lesser extent, China and Russia. One of many shortcomings of my previous book, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, included a too-exclusive focus on the historical experience of the wealthy countries of the world (that is, in Western Europe, North America, and Japan), partly because it was so difficult to access historical data for other countries and regions. The newly available data enabled me to go beyond the largely Western framework of my previous book and delve more deeply into the nature of inequality regimes and their possible trajectories. Despite this progress, numerous deficiencies remain in the data from rich countries as well as poor.

For the present book I also collected many other sources and documents dealing with periods, countries, or aspects of inequality not well covered by WID.world, including data about preindustrial and colonial societies as well as inequalities of status, profession, education, gender, race, and religion.

For the study of ideology I naturally relied on a wide range of sources. Some will be familiar to scholars: minutes of parliamentary debates, transcripts of speeches, and party platforms. I look at the writings of both theorists and political actors to see how inequalities were justified in different times and places. In the eleventh century, for example, bishops wrote in justification the trifunctional society, which consisted of three classes: clergy, warriors, and laborers. In the early 1980s Friedrich von Hayek published Law, Legislation, and Liberty, an influential neo-proprietarian and semi-dictatorial treatise. In between those dates, in the 1830s, John Calhoun, a Democratic senator from South Carolina and vice president of the United States, justified “slavery as a positive good.” Xi Jinping’s writings on China’s neo-communist dream or op-eds published in the Global Times are no less revealing than Donald Trump’s tweets or articles in praise of Anglo-American hypercapitalism in the Wall Street Journal or the Financial Times. All these ideologies must be taken seriously, not only because of their influence on the course of events but also because every ideology attempts (more or less successfully) to impose meaning on a complex social reality. Human beings will inevitably attempt to make sense of the societies they live in, no matter how unequal or unjust they may be. I start from the premise that there is always something to learn from such attempts. Studying them in historical perspective may yield lessons that can help guide our steps in the future.

I will also make use of literature, which is often one of our best sources when it comes to understanding how representations of inequality change. In Capital in the Twenty-First Century I drew on classic nineteenth-century novels by Honoré de Balzac and Jane Austen, which offer matchless insights into the ownership societies that flourished in France and England between 1790 and 1840. Both novelists possessed intimate knowledge of the property hierarchies of their time. They had deeper insight than others into the secret motives and hidden boundaries that existed in their day and understood how these affected people’s hopes and fears and determined who met whom and how men and women plotted marital strategies. Writers analyzed the deep structure of inequality—how it was justified, how it impinged on the lives of individuals—and they did so with an evocative power that no political speech or social scientific treatise can rival.

Literature’s unique ability to capture the relations of power and domination between social groups and to detect the way in which inequalities are experienced by individuals exists, as we shall see, in all societies. We will therefore draw heavily on literary works for invaluable insights into a wide variety of inequality regimes. In Destiny and Desire, the splendid fresco that Carlos Fuentes published in 2008 a few years before his death, we discover a revealing portrait of Mexican capitalism and endemic social violence. In This Earth of Mankind, published in 1980, Pramoedya Ananta Toer shows us how the inegalitarian Dutch colonial regime worked in Indonesia in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; his book achieves a brutal truthfulness unmatched by any other source. In Americanah (2013), Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie offers us a proud, ironic view of the migratory routes her characters Ifemelu and Obinze follow from Nigeria to the United States and Europe, providing unique insight into one of the most important aspects of today’s inequality regime.

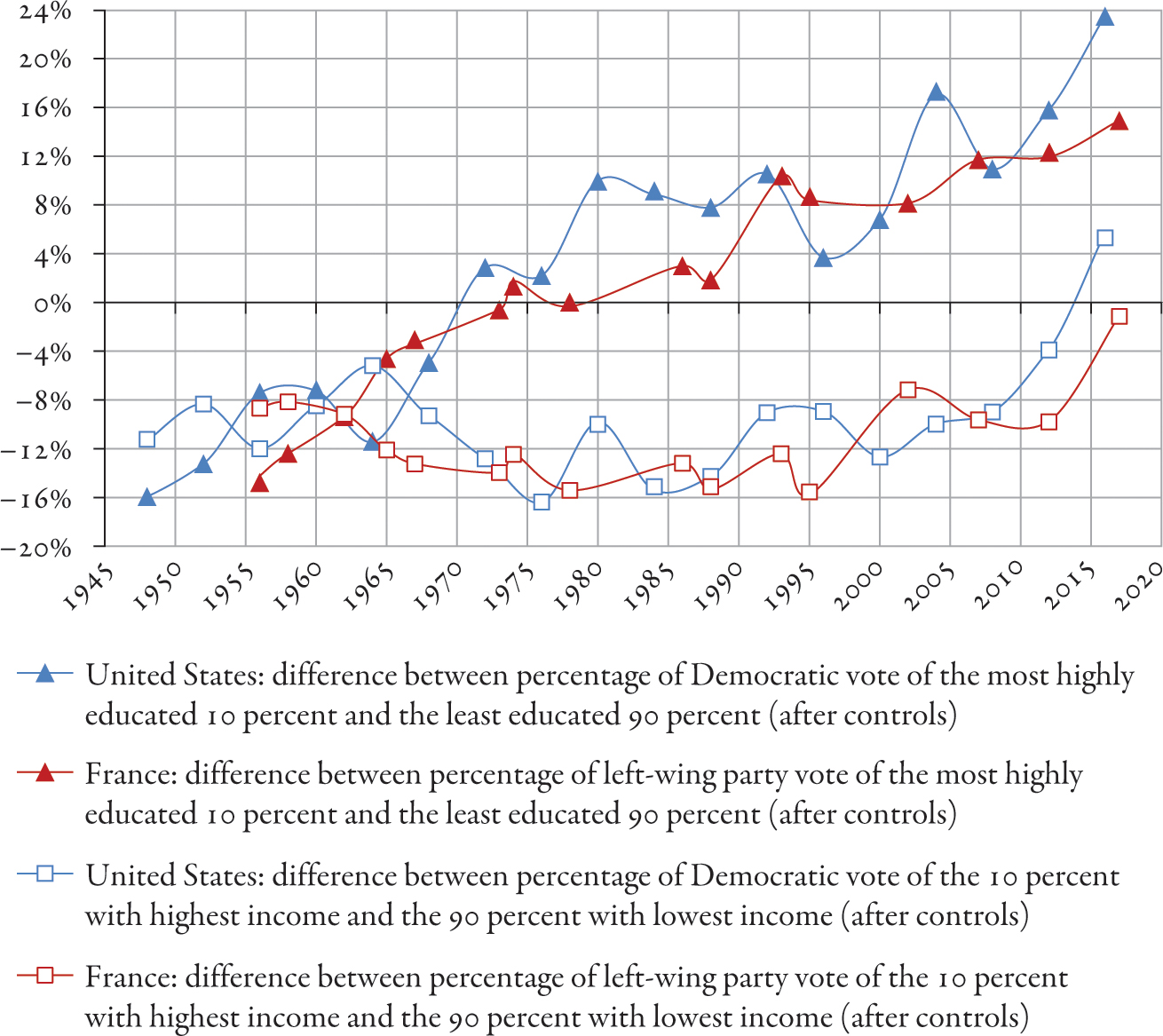

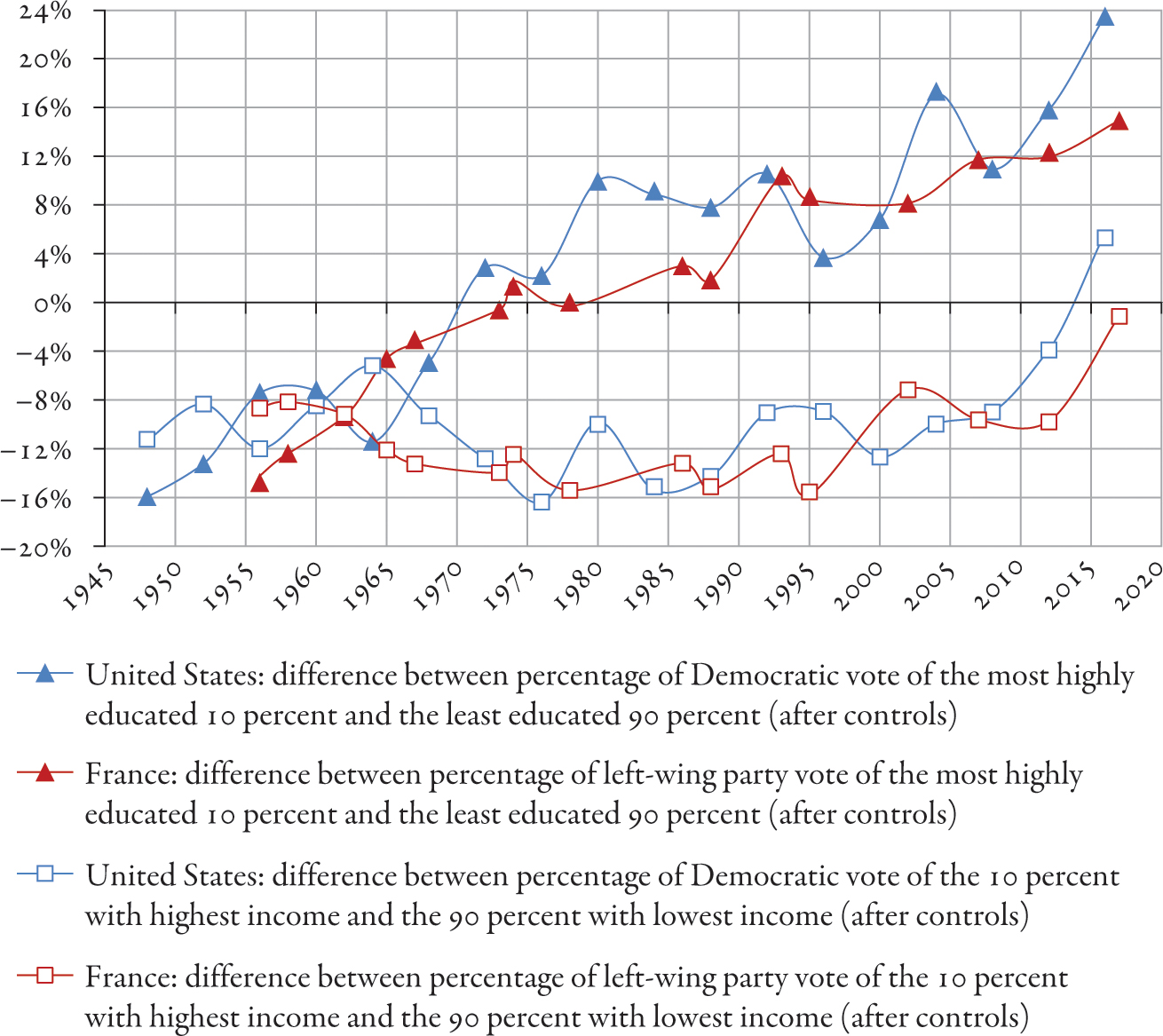

To study ideologies and their transformations, I also make systematic and novel use of the postelection surveys that have been carried out since the end of World War II in most countries where elections are held. Despite their limitations, these surveys offer an incomparable view of the structure of political, ideological, and electoral conflict from the 1940s to the present, not only in most Western countries (including France, the United States, and the United Kingdom, to which I will devote special attention) but also in many other countries, including India, Brazil, and South Africa. One of the most important shortcomings of my previous book, apart from its focus on the rich countries, was its tendency to treat political and ideological changes associated with inequality and redistribution as a black box. I proposed a number of hypotheses concerning, for example, changing political attitudes toward inequality and private property owing to world war, economic crisis, and the communist challenge in the twentieth century, but I never really tackled head on the question of how inegalitarian ideologies evolve. In the present work I try to do this much more explicitly by situating the question in a broader temporal and spatial perspective. In doing so I make extensive use of postelection surveys and other relevant sources.

Human Progress, the Revival of Inequality, and Global Diversity

Now to the heart of the matter: human progress exists, but it is fragile. It is constantly threatened by inegalitarian and identitarian tendencies. To believe that human progress exists, it suffices to look at statistics for health and education worldwide over the past two centuries (Fig. I.1). Average life expectancy at birth rose from around 26 years in 1820 to 72 years in 2020. At the turn of the nineteenth century, around 20 percent of all newborns died in their first year, compared with 1 percent today. The life expectancy of children who reach the age of 1 has increased from roughly 32 years in 1820 to 73 today. We could focus on any number of other indicators: the probability of a newborn surviving until age 10, of an adult reaching age 60, or of a retiree enjoying five or ten years of good health. Using any of these indicators, the long-run improvement is impressive. It is of course possible to cite countries or periods in which life expectancy declined even in peacetime, as in the Soviet Union in the 1970s or the United States in the 2010s. This is generally not a good sign for the regimes in which it occurs. In the long run, however, there can be no doubt that things have improved everywhere in the world, notwithstanding the limitations of available demographic sources.3

FIG. I.1. Health and education in the world, 1820–2020

Interpretation: Life expectancy at birth worldwide increased from an average of 26 years in 1820 to 72 years in 2020. Life expectancy at birth for those living to age 1 increased from 32 to 73 years (because infant mortality before age 1 decreased from roughly 20 percent in 1820 to less than 1 percent in 2020). The literacy rate of those 15 years and older worldwide rose from 12 to 85 percent. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

People are healthier today than ever before. They also have more access to education and culture. UNESCO defines literacy as the “ability to identify, understand, interpret, create, communicate and compute, using printed and written materials associated with varying contexts.” Although no such definition existed at the turn of the nineteenth century, we can deduce from various surveys and census data that barely 10 percent of the world’s population aged 15 and older could be classified as literate compared with more than 85 percent today. This finding is confirmed by more precise indices such as years of schooling, which has risen from barely one year two centuries ago to eight years today and to more than twelve years in the most advanced countries. In the age of Austen and Balzac, fewer than 10 percent of the world’s population attended primary school; in the age of Adichie and Fuentes, more than half of all children in the wealthiest countries attend university. What had always been a class privilege is now available to the majority.

To gauge the magnitude of these changes, it is also important to note that the world’s population is more than ten times larger today than it was in the eighteenth century, and the average per capita income is ten times higher. From 600 million in 1700 the population of the world has grown to more than 7 billion today, while average income, insofar as it can be measured, has grown from a purchasing power of less than 100 (expressed in 2020 euros) a month in 1700 to roughly 1,000 today (Fig. I.2). This is a significant quantitative gain, although it should be noted that it corresponds to an annual growth rate of just 0.8 percent (extended over three centuries, which proves, if proof were needed, that earthly paradise can be achieved without a growth rate of 5 percent). Whether this increase in population and average monthly income represents “progress” as indubitable as that achieved in health and education is open to question, however.

FIG. I.2. World population and income, 1700–2020

Interpretation: Global population and average national income increased more than tenfold between 1700 and 2020: population rose from 600 million in 1700 to more than 7 billion in 2020; income, expressed in terms of 2020 euros and purchasing power parity, increased from barely 80 euros per month per person in 1700 to roughly 1,000 euros per month per person in 2020. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

It is difficult to interpret the meaning of these changes and their future implications. The growth of the world’s population is due in part to the decline in infant mortality and the fact that growing numbers of parents lived long enough to care for their children to the brink of adulthood. If this rate of population growth continues for another three centuries, however, the population of the planet will grow to more than 70 billion, which seems neither desirable nor sustainable. The growth of average per capita income has meant a very substantial improvement in standards of living: three-quarters of the globe’s inhabitants lived close to the subsistence threshold in the eighteenth century compared with less than a fifth today. People today enjoy unprecedented opportunities for travel and recreation and for meeting other people and achieving emancipation. Yet several issues bedevil the national accounts I rely on to describe the long-term trajectory of average income. Because national accounts deal with aggregates, they take no account of inequality and have been slow to incorporate data on sustainability, human capital, and natural capital. Because they try to sum up the economy in a single-figure, total national income, they are not very useful for studying long-run changes in such multidimensional variables as standards of living and purchasing power.4

While the progress made in the areas of health, education, and purchasing power has been real, it has masked vast inequalities and vulnerabilities. In 2018, the infant mortality rate was less than 0.1 percent in the wealthiest countries of Europe, North America, and Asia, but nearly 10 percent in the poorest African countries. Average per capita income rose to 1,000 euros per month, but it was barely 100–200 euros a month in the poorest countries and more than 3,000–4,000 a month in the wealthiest. In a few tiny tax havens, which are suspected (rightly) of robbing the rest of the planet, it is even higher, as is also the case in certain petro-monarchies whose wealth comes at the price of future global warming. There has been real progress, but we can always do better, so we would be foolish to rest on our laurels.

Although there can be no doubt about the progress made between the eighteenth century and now, there have also been phases of regression, during which inequality increased and civilization declined. The Euro-American Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution coincided with extremely violent systems of property ownership, slavery, and colonialism, which attained historic proportions in the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries. Between 1914 and 1945 the European powers themselves succumbed to a phase of genocidal self-destruction. In the 1950s and 1960s the colonial powers were obliged to decolonize, while at the same time the United States finally granted civil rights to the descendants of slaves. Owing to the conflict between capitalism and communism, the world had long lived with fears of nuclear annihilation. With the collapse of the Soviet empire in 1989–1991, those fears dissipated. South African apartheid was abolished in 1991–1994. Yet soon thereafter, in the early 2000s, a new regressive phase began, as the climate warmed and xenophobic identity politics gained a foothold in many countries. All of this took place against a background of growing socioeconomic inequality after 1980–1990, propelled by a particularly radical form of neo-proprietarian ideology. It would make little sense to assert that everything that happened between the eighteenth century and today was somehow necessary to achieve the progress noted above. Other paths could have been followed; other inequality regimes could have been chosen. More just and egalitarian societies are always possible.

If there is a lesson to be learned from the past three centuries of world history, it is that human progress is not linear. It is wrong to assume that every change will always be for the best or that free competition between states and among economic actors will somehow miraculously lead to universal social harmony. Progress exists, but it is a struggle, and it depends above all on rational analysis of historical changes and all their consequences, positive as well as negative.

The Return of Inequality: Initial Bearings

Among the most worrisome structural changes facing us today is the revival of inequality nearly everywhere since the 1980s. It is hard to envision solutions to other major problems such as immigration and climate change if we cannot both reduce inequality and establish a standard of justice acceptable to a majority of the world’s people.

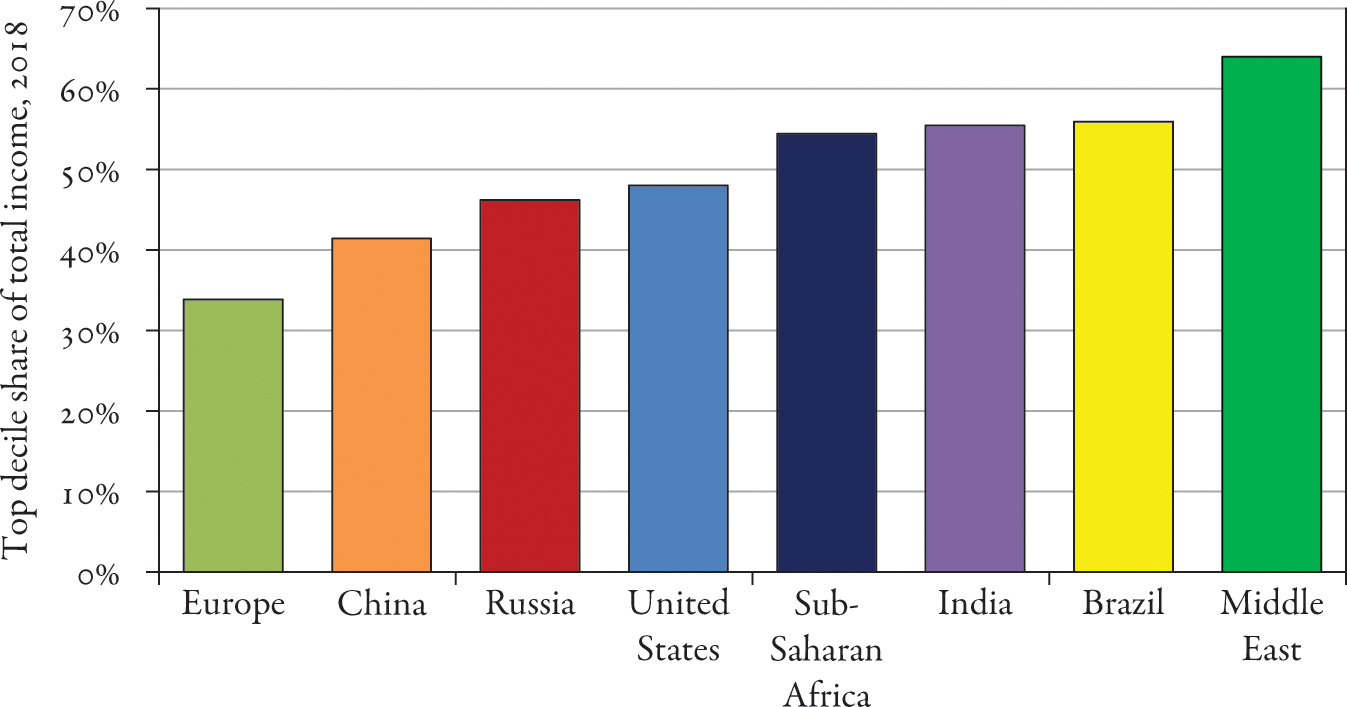

Let us begin by looking at a simple indicator, the share of the top decile (that is, the top 10 percent) of the income distribution in various places since 1980. If perfect social equality existed, the top decile’s share would be exactly 10 percent. If perfect inequality prevailed, it would be 100 percent. In reality it falls somewhere between these two extremes, but the exact figure varies widely in time and space. Over the past few decades we find that the top decile’s share has risen almost everywhere. Take, for example, India, the United States, Russia, China, and Europe. The share of the top decile in each of these five regions stood at around 25–35 percent in 1980 but by 2018 had risen to between 35 and 55 percent (Fig. I.3). How much higher can it go? Could it rise to 55 or even 75 percent over the next few decades? Note, too, that there is considerable variation in the magnitude of the increase from region to region, even at comparable levels of development. The top decile’s share has risen much more rapidly in the United States than in Europe and much more in India than in China.

FIG. I.3. The rise of inequality around the world, 1980–2018

Interpretation: The share of the top decile (the 10 percent of highest earners) in total national income ranged from 26 to 34 percent in different parts of the world and from 34 to 56 percent in 2018. Inequality increased everywhere, but the size of the increase varied sharply from country to country at all levels of development. For example, it was greater in the United States than in Europe (enlarged European Union, 540 million inhabitants) and greater in India than in China. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

When we look more closely at the data, we find that the increase in inequality has come at the expense of the bottom 50 percent of the distribution, whose share of total income stood at about 20–25 percent in 1980 in all five regions but had fallen to 15–20 percent in 2018 (and, indeed, as low as 10 percent in the United States, which is particularly worrisome).5

If we take a longer view, we find that the five major regions of the world represented in Fig. I.3 enjoyed a relatively egalitarian phase between 1950 and 1980 before entering a phase of rising inequality since then. The egalitarian phase was marked by different political regimes in different regions: communist regimes in China and Russia and social-democratic regimes in Europe and to a certain extent in the United States and India. We will be looking much more closely at the differences among these various political regimes in what follows, but for now we can say that all favored some degree of socioeconomic equality (which does not mean that other forms of inequality can be ignored).

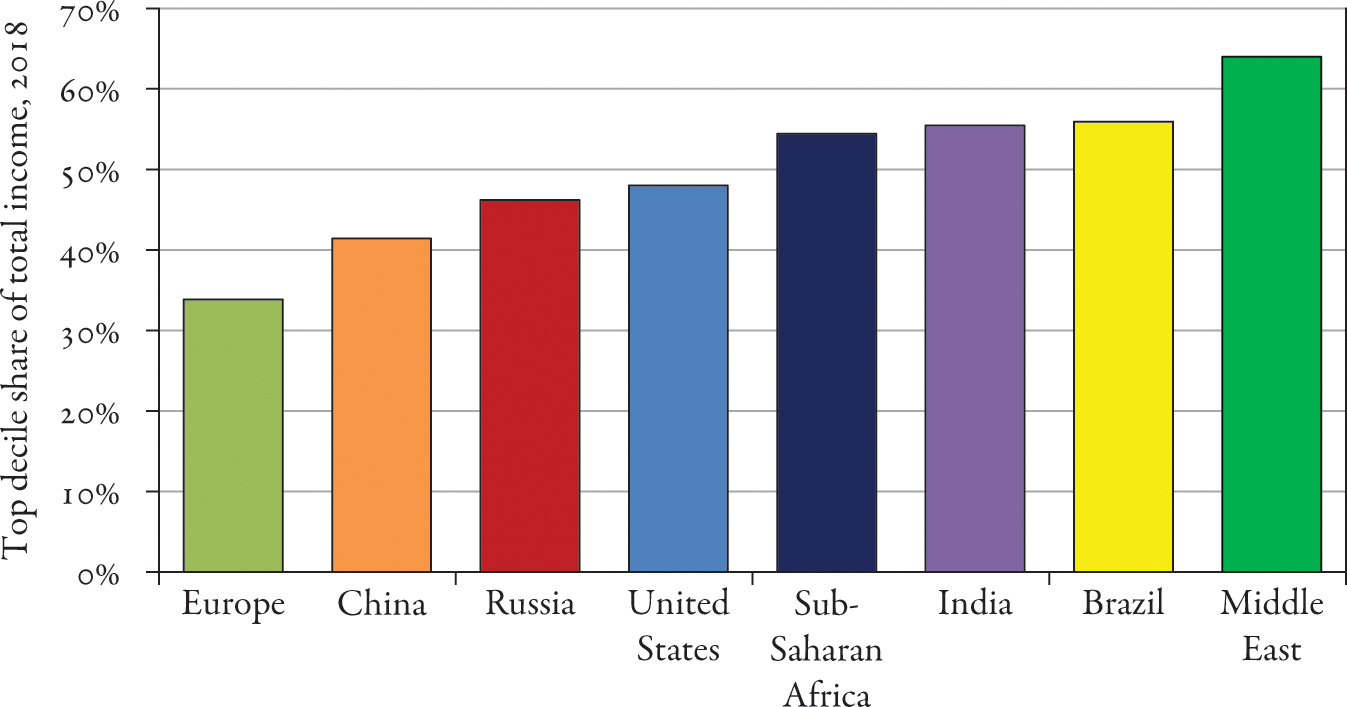

If we now expand our view to include other parts of the world, we see that inequalities were even greater elsewhere (Fig. I.4). For instance, the top decile claimed 54 percent of total income in sub-Saharan Africa (and as much as 65 percent in South Africa), 56 percent in Brazil, and 64 percent in the Middle East, which stands out as the world’s most inegalitarian region in 2018 (almost on a par with South Africa). There, the bottom 50 percent of the distribution earns less than 10 percent of total income.6 The causes of inequality vary widely from region to region. For instance, the historical legacy of racial and colonial discrimination and slavery weighs heavily in Brazil and South Africa as well as in the United States. In the Middle East more “modern” factors are at play: petroleum wealth and the financial assets into which it has been converted are concentrated in very few hands thanks to the workings of global markets and sophisticated legal systems. South Africa, Brazil, and the Middle East stand at the frontier of modern inequality, with top decile shares of 55–65 percent. Despite deficiencies in the available historical data, moreover, it appears that inequality in these regions has always been high: they never experienced a relatively egalitarian “social-democratic” phase (much less a communist one).

To sum up, inequality has increased in nearly every region of the world since 1980, except in those countries that have always been highly inegalitarian. In a sense, what is happening is that regions that enjoyed a phase of relative equality between 1950 and 1980 are moving back toward the inegalitarian frontier, albeit with large variations from country to country.

FIG. I.4. Inequality in different regions of the world in 2018

Interpretation: In 2018, the share of the top decile (the highest 10 percent of earners) in national income was 34 percent in Europe, 41 percent in China, 46 percent in Russia, 48 percent in the United States, 54 percent in sub-Saharan Africa, 55 percent in India, 56 percent in Brazil, and 64 percent in the Middle East. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

The Elephant Curve: A Sober Debate about Globalization

The revival of within-country inequality after 1980 is by now a well-established and widely recognized phenomenon. There is, however, no agreement on what to do about it. The key question is not the level of inequality but rather its origin and justification. For instance, it is perfectly possible to argue that the level of income inequality was kept artificially and excessively low under Russian and Chinese Communism before 1980. Hence there is nothing wrong with the growing income inequality observed since then; inequality has actually stimulated innovation and growth for the benefit of all, especially in China, where the poverty rate has decreased dramatically. But to what extent is this argument correct? Care is necessary in evaluating the data. Was it justifiable, for example, for Russian and Chinese oligarchs to capture so much natural wealth and so many formerly public enterprises in the period 2000–2020, especially when those oligarchs frequently failed to demonstrate much talent for innovation, except when it came to inventing legal and fiscal stratagems to secure the wealth they appropriated? To fully answer this question one cannot simply say that there was too little inequality prior to 1980.

A similar argument could be made about India, Europe, and the United States—namely, that equality had gone too far in the period 1950–1980 and had to be curtailed for the sake of the poor. Here, however, the problems are even greater than in the case of Russia or China. Even if this argument were partly correct, would it justify a priori any level of inequality whatsoever, without so much as a glance at the data? Growth rates in both Europe and the United States were higher, for example, in the egalitarian period (1950–1980) than in the subsequent phase of rising inequality. This casts doubt on the argument that greater inequality is always socially useful. After 1980, inequality increased more in the United States than in Europe, but this did not lead to a higher rate of growth, much less benefit the bottom 50 percent of the income distribution, whose standard of living stagnated in absolute terms and fell sharply compared to that of top earners. In other words, overall growth of national income decreased in the United States, as did the share of the bottom half. In India, inequality increased much more sharply after 1980 than in China, but India’s growth rate was lower so that the bottom 50 percent was doubly penalized by both a lower growth rate and a decreased share of national income. Clearly, then, the argument that the income gap between high and low earners had been compressed too much in the period 1950–1980, thus calling for a corrective, has its shortcomings. Nevertheless, it should be taken seriously, up to a point, and we will do so in what follows.

One clear way of representing the distribution of global growth in the period 1980–2018 is to plot the cumulative income growth of each decile of the global income distribution. The result is sometimes referred to as “the elephant curve” (Fig. I.5).7 This can be summarized as follows. The sixth to ninth deciles of global income (comprising people who belonged to neither the bottom 60 percent nor the top 10 percent of the income distribution or, in other words, the global middle class) did not benefit much at all from global economic growth in this period. By contrast, the groups above and below this global middle class benefited a great deal. Some relatively poor households (in the second, third, and fourth deciles of the world income distribution) did improve their position; some of the wealthiest households in the wealthiest countries gained even more (namely, those in the tip of the elephant’s trunk, the ninety-ninth percentile or top 1 percent, and especially the top tenth and one-hundredth of a percent, whose incomes rose by several hundred percent). If the global income distribution were stable, this curve would be flat: each percentile would progress at the same rate as all the others. There would still be rich people and poor people as well as upward and downward mobility, but the average income of each percentile would increase at the same rate.8 In other words, “a rising tide would lift all boats,” to use an expression that became popular in the postwar era, when the tide did seem to be rising. The fact that the elephant curve is so far from flat illustrates the magnitude of the change we have been witnessing over the past three decades.

FIG. I.5. The elephant curve of global inequality, 1980–2018

Interpretation: The bottom 50 percent of the global income distribution saw substantial growth in purchasing power between 1980 and 2018 (60–120 percent). The top centile saw even stronger growth (80–240 percent). Intermediate categories grew less. In sum, inequality decreased between the bottom and middle of the income distribution and increased between the middle and the top. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

The elephant curve is fundamental because it explains why globalization is so politically controversial: for some observers the most striking fact is that the remarkable growth of certain less developed countries has so dramatically reduced global poverty and inequality while others deplore the sharp increase of inequality at the top due to the excesses of global hypercapitalism. Both sides have a point: inequality between the bottom and middle of the global income distribution has decreased, while inequality between the middle and top has increased. Both aspects of the globalization story are real. The point is not to deny either part of the story but rather to figure out how to retain the good features of globalization while getting rid of the bad. Here we see the importance of choosing the right terminology and conceptual framework. If we tried to describe inequality using a single indicator, such as the Gini coefficient,* we could easily deceive ourselves. Because we would then lack the means to perceive complex, multidimensional changes, we might think that nothing had changed at all: with a single indicator, several disparate phenomena can cancel one another out. For that reason, I avoid relying on any single “synthetic” index. I will always be careful to distinguish the various deciles and percentiles of the relevant wealth and income distributions (and thus the social groups to which they correspond).9

Some critics object that the elephant curve focuses too much attention on the top 1 or 0.1 percent of the global population, where the gains have been highest. It is foolish, they say, to arouse envy of such a tiny group rather than rejoice in the manifest growth at the lower end of the distribution. In fact, recent research confirms the importance of looking at top incomes; indeed, it shows that the gains at the top are even larger than the original elephant curve suggested. Between 1980 and 2018, the top 1 percent captured 27 percent of global income growth, versus just 12 percent for the bottom 50 percent (Fig. I.5). In other words, the tip of the pachyderm’s trunk may concern only a tiny segment of the population, but it has captured an elephant-sized portion of the world’s growth—its share is twice as large as that of the 3.5 billion individuals at the bottom end.10 In other words, a growth model only slightly less beneficial to those at the top would have permitted a much more rapid reduction in global poverty (and could still do so in the future).

Although this type of data can clarify the issues, it cannot end the debate. Everything depends on the causes of inequality and how it is justified. How much can the growth of top incomes be justified by the benefits the wealthy contribute to the rest of society? If one believes that greater inequality always and everywhere leads to higher income and better living standards for the poorest 50 percent, can one justify the 27 percent of world income growth captured by the top 1 percent—or perhaps even at higher percentages—why not 40 or 60 or even 80 percent? The cases mentioned earlier—the United States versus Europe and India versus China—suggest that this is not a very persuasive argument, however, because the countries where top earners gained the most are not those where the poor reaped the largest benefits. Analysis of these cases suggests that the share going to the top 1 percent could have been reduced to 10 or 20 percent, or perhaps even less, while still allowing significant improvement in the living standards of the bottom 50 percent. These issues are important enough to call for more detailed investigation. In any case, the data suggest that there is no reason to believe that there is just one way to organize the global economy. There is no reason to believe that the top 1 percent must capture precisely 27 percent of income growth (versus 12 percent for the bottom 50). What the global growth figures reveal is that the distribution of gains is just as important as overall growth. Hence there is ample room for debate about the political and institutional choices that affect distribution.

On the Justification of Extreme Inequality

The world’s largest fortunes have grown since 1980 at even faster rates than the world’s top incomes depicted in Fig. I.5. Great fortunes grew extremely rapidly in all parts of the world: among the leading beneficiaries were Russian oligarchs, Mexican magnates, Chinese billionaires, Indonesian financiers, Saudi investors, Indian industrialists, European rentiers, and wealthy Americans. In the period 1980–2018, large fortunes grew at rates three to four times the growth rate of the global economy. Such phenomenal growth cannot continue indefinitely, unless one is prepared to believe that nearly all global wealth is destined to end up in the hands of billionaires. Nevertheless, the gap between top fortunes and the rest continued to grow even in the decade after the financial crisis of 2008 at virtually the same rate as in the two previous decades, which suggests that we may not yet have seen the end of a massive change in the structure of the world’s wealth.11

In the face of such spectacular change, many justifications of wealth inequality have been proposed, some of them quite surprising. In the West, for example, apologists like to divide the rich into two categories. On the one hand, there are Russian oligarchs, Middle Eastern oil sheiks, and billionaires of various nationalities, be they Chinese, Mexican, Guinean, Indian, or Indonesian. Critics question whether such people “deserve” their wealth, which they allegedly owe to close ties to the powers that be in their respective countries: for example, it is often insinuated that these fortunes originated with unfair appropriation natural resources or illegitimate licensing arrangements. The beneficiaries supposedly did little to stimulate economic growth. On the other hand, there are entrepreneurs, usually European or American, of whom Silicon Valley innovators serve as a paradigmatic example. Their contributions to global prosperity are widely praised. If they were properly rewarded for their efforts, some say, they would be even richer than they are. Society, their champions argue, owes them a moral debt, which it should perhaps repay in the form of tax breaks or political influence (which in some countries they may already have achieved on their own). Such hyper-meritocratic, Western-centric justifications of inequality demonstrate the irrepressible human need to make sense of social inequality, at times in ways that stretch credulity. This quasi-beatification of wealth often ignores inconvenient facts. Would Bill Gates and his fellow techno-billionaires have been able to build their businesses without the hundreds of billions of dollars of public money invested in basic research over many decades? Would the quasi-monopolies they have built by patenting public knowledge have reaped such enormous profits without the active support of legal and tax codes?

Most justifications of extreme wealth inequality are less grandiose, however. The need for stability and protection of property rights is often emphasized. In other words, defenders admit that inequality of wealth may not be entirely just or invariably useful, especially when it reaches the level observed in places like California. But, they argue, challenging the status quo might initiate a self-reinforcing process whose effect on the poorest members of society would ultimately be negative. This quasi-religious defense of property rights as the sine qua non of social and political stability was characteristic of the ownership societies that flourished in Europe and the United States in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The need for stability also figured in justifications of trifunctional and slave societies. Lately, the stability argument has been augmented by the claim that states are less inefficient than private philanthropy—an old argument that has recently regained prominence. All of these justifications of inequality deserve a hearing, but they can be refuted by applying the lessons of history.

Learning from History: The Lessons of the Twentieth Century

To understand and learn from what has been happening in the world since 1980, we must adopt a long-term historical and comparative perspective. The current inequality regime, which I call neo-proprietarian, bears traces of all the regimes that preceded it. To study it properly, we must begin by examining how the trifunctional societies of the premodern era, which were based on a ternary structure (clergy, nobility, and third estate), evolved into the ownership societies of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and then how those societies collapsed in the twentieth century in the face of challenges from communism and social democracy, world war, and, finally, wars of national liberation, which put an end to centuries of colonial domination. All human societies need to make sense of their inequalities, and the justifications given in the past turn out, if studied carefully, to be no more incoherent than those of the present. By examining them all in their concrete historical contexts, paying close attention to the multiplicity of possible trajectories and forks in the road, we can shed light on the present inequality regime and begin to see how it might be transformed.

The collapse of ownership and colonialist society in the twentieth century plays an especially important role in this history. It radically transformed the structure and justification of inequality, leading directly to the present state of affairs. The countries of Western Europe—most notably France, the United Kingdom, and Germany, which had been more inegalitarian than the United States on the eve of World War I—became more egalitarian over the course of the twentieth century, partly because the shocks of the period 1914–1945 resulted in a greater compression of inequalities there and partly because inequality increased more in the United States after 1980 (Fig. I.6).12 In both Europe and the United States, the compression of inequality in the period 1914–1970 can be explained by legal, social, and fiscal changes hastened by two world wars, the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, and the Great Depression of 1929. In an intellectual and political sense, however, those changes were already under way by the end of the nineteenth century, and it is reasonable to think that they would have occurred in one form or another even if those crises had not occurred. Historical change takes place when evolving ideas confront the logic of events: neither has much effect without the other. We will encounter this lesson numerous times in what follows, for example, when we analyze the events of the French Revolution or changes in the structure of inequality in India since the end of the colonial era.

FIG. I.6. Inequality, 1900–2020: Europe, United States, and Japan

Interpretation: The top decile’s share of total national income was about 50 percent in Western Europe in 1900–1910 before decreasing to roughly 30 percent in 1950–1980 and then rising again to more than 35 percent in 2010–2020. Inequality grew more strongly in the United States, where the top decile share approached 50 percent in 2010–2020, exceeding the level of 1900–1910. Japan was in an intermediate position. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

Among the changes that contributed to the reduction of inequality in the twentieth century was the widespread emergence of a system of progressive taxation of both income and inherited wealth. The highest incomes and largest fortunes were taxed more heavily than smaller ones. In this the United States led the way: in the Gilded Age (1865–1900) and beyond, as industrial and financial wealth accumulated, Americans worried that their country might one day become as inegalitarian as the societies of the Old World, which they viewed as oligarchic and therefore at odds with the democratic spirit of the United States. The United Kingdom also turned to progressive taxation. Although the United Kingdom experienced much less destruction of wealth than either France or Germany between 1914 and 1945, it nevertheless chose (in calmer political circumstances than prevailed on the continent) to reject its highly inegalitarian past by imposing steeply progressive taxes on income and estates.

In the period 1932–1980, the top marginal income rate averaged 81 percent in the United States and 89 percent in the United Kingdom compared with “only” 58 percent in German and 60 percent in France (Fig. I.7). Note that these rates include only the income tax (and not other levies such as consumption taxes). In the United States they include only the federal income tax and not state income taxes (which can add 5–10 percent on top of the federal tax). Clearly, the fact that top marginal rates remained above 80 percent for nearly half a century did not destroy capitalism in the United States—quite the opposite.

As we will see, highly progressive taxation contributed strongly to the reduction of inequality in the twentieth century. We will also analyze in detail how progressive taxation was undone in the 1980s, especially in the United States and United Kingdom, and investigate what lessons can be drawn from this. The drastic reduction of top tax rates was the signature issue of the “conservative revolution” waged by the Republican Party under Ronald Reagan in the United States and the Conservative Party under Margaret Thatcher in Britain in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The ensuing political and ideological shift had a marked impact on taxes and inequality not only in the United States and United Kingdom but also around the world. Moreover, the turn to the right was never really challenged by the parties and governments that followed Reagan and Thatcher. In the United States the top marginal federal income tax rate has fluctuated between 30 and 40 percent since the end of the 1980s. In the United Kingdom it has ranged from 40 to 45 percent, with a slight upward trend since the crisis of 2008. In both cases, the top rate between 1980 and 2018 has remained at roughly half that of the period 1932–1980 (40 percent compared with 80 percent; see Fig. I.7).

FIG. I.7. Top income tax rates, 1900–2020

Interpretation: The top marginal tax rate applied to the highest incomes averaged 23 percent in the United States from 1900 to 1932, 81 percent from 1932 to 1980, and 39 percent from 1980 to 2018. Over the same period, the top rates averaged 30, 89, and 46 percent in the United Kingdom; 18, 58, and 50 percent in Germany; and 23, 60, and 57 percent in France. The tax system was most progressive in the middle of the century, particularly in the United States and United Kingdom. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

For champions of the fiscal turn, the spectacular decrease of progressivity was justified by the idea that top marginal rates had risen to unconscionable levels prior to 1980. Some argued that high top rates had sapped the entrepreneurial spirit of British and American innovators, allowing the United States and United Kingdom to be overtaken by West European and Japanese competitors (a prominent campaign issue in both countries in the 1970s and 1980s). In hindsight, these arguments cannot withstand scrutiny. The issue deserves a fresh look. Many other factors explain why Germany, France, Sweden, and Japan caught up with the United States and United Kingdom in the period 1950–1980. Those countries had fallen seriously behind the leaders, especially the United States, and a growth spurt was all but inevitable. Growth was also spurred by institutional factors, including relatively ambitious (and egalitarian) social and educational policies adopted after World War II. These policies helped rivals catch up with the United States and surge ahead of the United Kingdom, where the educational system had been seriously neglected since the late nineteenth century. And once again, it should be stressed that productivity growth in the United States and United Kingdom was higher in the period 1950–1990 than in 1990–2020, thus casting serious doubt on the argument that reducing top marginal tax rates spurs economic growth.

In the end, it is fair to say that the move to a less progressive tax system in the 1980s played a large part in the unprecedented growth of inequality in the United States and United Kingdom between 1980 and 2018. The share of national income going to the bottom half of the income distribution collapsed, contributing perhaps to the feeling on the part of the middle and lower classes that they had been abandoned in addition to fueling the rise of xenophobia and identity politics in both countries. These developments came to a head in 2016, with the British vote to leave the European Union (Brexit) and the election of Donald Trump. With this recent history in mind, the time has come to rethink the wisdom of progressive taxation of both income and wealth, in rich countries as well as poor—the latter being the first to suffer from fiscal competition and lack of financial transparency. The free and unchecked circulation of capital without sharing of information between national tax authorities has been one of the primary means by which the conservative fiscal revolution of the 1980s has been protected and extended. It has adversely affected the process of state building and the development of just tax systems everywhere. Which raises another key question: Why have the social-democratic coalitions that emerged in the postwar era proved so unable to respond to these challenges? In particular, why have social democrats been so inept at constructing a progressive transnational tax system? Why have they not promoted the idea of social and temporary private ownership? If there were a sufficiently progressive tax on the largest holders of private property, such an idea would emerge naturally, because property owners would then be obliged to return a significant fraction of what they owned to the community every year. This political, intellectual, and ideological failure of social democracy must count among the reasons for the revival of inequality, reversing the historic trend toward ever greater equality.

On the Ideological Freeze and New Educational Inequalities

To understand what is happening, we will also need to look at political and ideological changes affecting other political and social institutions that have contributed to the reduction and regulation of inequality. I am thinking primarily of economic power sharing and employee involvement in business decision making and strategy setting. In the 1950s, several countries, including Germany and Sweden, were pioneers in this area, but until recently their innovations were not widely adopted or improved on. The reasons for this failure surely have to do with the specific histories of individual countries. Until the 1980s, for instance, the British Labour Party and French Socialists favored programs of nationalization, but after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of communism they abruptly gave up on redistribution altogether. Moreover, in no region has enough attention been paid to transcending private property in its present form.