{ THIRTEEN }

Hypercapitalism: Between Modernity and Archaism

In Chapter 12 we looked at the role of communist and postcommunist societies in the history of inequality regimes, especially in relation to the resurgence of inequality since the 1980s. Today’s world is a direct consequence of the great political-ideological transformations that inequality regimes experienced over the course of the twentieth century. The fall of communism led to a certain disillusionment concerning the very possibility of a just society. Disillusionment led to retreat and to the defense of national, ethnic, and religious identities; this must be overcome. The end of colonialism gave rise to new, ostensibly less inegalitarian economic relations and migration flows between different regions of the world, but the global system remains hierarchical and not sufficiently social or democratic, and new tensions have arisen both within and between countries. Finally, proprietarian ideology has returned in a new form, which I call neo-proprietarian despite the many differences between the old version and the new. But the neo-proprietarian regime is less unified and more fragile than it might appear.

In this chapter we will study several of the major inegalitarian and ideological challenges that all societies face today, with an emphasis on the potential for change and evolution. We will begin by looking at the various types of extreme inequality that exist in the world today, as old and new logics come together. We will then ask why our economic and financial system has become increasingly opaque, particularly with respect to recording and measuring income and wealth. In a world that regularly celebrates the era of “big data,” this may come as a surprise. It reflects a dereliction of duty on the part of government authorities and statistical agencies. Worse, it greatly complicates the task of organizing an informed global debate about inequality and other major issues, beginning with climate change, which could serve as a catalyst for a new politics. After that, we will review other fundamental global challenges related to inequality: the persistence of strong patriarchal inequalities between men and women, which only vigorous proactive measures can overcome; the paradoxical pauperization of the state in developing countries as a consequence of trade liberalization imposed without sufficient preparation or political coordination; and finally, the new role of monetary creation since 2008, which has deeply altered perceptions of the respective roles of governments and central banks, taxes and monetary creation, and, more generally, of the idea of a just economy. All of this will help us to understand today’s neo-proprietarianism and what needs to be done to overcome it.

Forms of Inequality in the Twenty-First Century

The most obvious characteristic of today’s global inequality regime is that societies around the world are more intensely interdependent than ever before. Globalization is of course a very long-term process. Relations among the different regions of the world have been gradually expanding since 1500. Violence was often involved, as in the era of slavery and colonialism. But at other times trade and cultural exchange took more peaceful forms. In terms of commerce, immigration, and finance, the world achieved a remarkable level of integration during the Belle Époque (1880–1914). But since then, globalization has attained another level altogether in the era of hypercapitalism and digital technology (1990–2020). International travel has become routine, and images, texts, and sounds can now be transmitted instantaneously to the four corners of the earth. New information technologies have given rise to previously unknown forms of cultural, sociopolitical, and political-ideological exchange and interdependence. These changes have taken place, moreover, against a background of rapid demographic growth and broad rebalancing. The United Nations predicts that the global population will reach 9 billion in 2050: 5 billion in Asia, 2 billion in Africa, 1 billion in the Americas, and less than 1 billion in Europe (Fig. 13.1).

Such interconnectedness is not incompatible with a great social and political diversity, however. According to available sources, the top decile’s share of total income is less than 35 percent in Europe but close to 70 percent in the Middle East, South Africa, and Qatar (Fig. 13.2). If we look at the share of national income going to the bottom 50 percent, the next 40 percent, and the top 10 percent (or 1 percent), we find large variations between countries. In the least inegalitarian countries, the top decile share is “only” 1.5 times as large as that of the bottom 50 percent, compared with seven times as large in the most inegalitarian countries (Fig. 13.3). The top centile share is half that of the bottom 50 percent in the most egalitarian countries (which is quite a lot, considering that the top centile is one-fiftieth the size) but more than triple the bottom 50 percent’s share in the most inegalitarian countries (Fig. 13.4). These figures show why it is a mistake to compare countries only in terms of macroeconomic averages (such as gross domestic product [GDP] per capita). Equivalent averages can conceal totally different realities in terms of income distribution among different social groups.

FIG. 13.1. Population by continents, 1700–2050

Interpretation: In 1700, the global population was about 600 million, of whom 400 million lived in Asia and the Pacific, 120 million in Europe and Russia, 60 million in Africa, and 15 million in America. In 2050, according to UN projections, it will be about 9.3 billion, with 5.2 billion in Asia/Pacific, 2.2 in Africa, 1.2 in the Americas, and 0.7 in Europe/Russia. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

FIG. 13.2. Global inequality regimes, 2018

Interpretation: In 2018, the top decile share of national income was 34 percent in Europe, 41 percent in China, 46 percent in Russia, 48 percent in the United States, 55 percent in India, 56 percent in Brazil, 64 percent in the Middle East, 65 percent in South Africa, and 68 percent in Qatar. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

FIG. 13.3. Inequality in Europe, the United States, and the Middle East, 2018

Interpretation: The top decile’s share of total income is 64 percent in the Middle East (population 420 million) compared with 9 percent for the bottom 50 percent. In Europe (enlarged EU, pop. 540 million), these shares are 34 and 21 percent, and in the United States (pop. 320 million), 47 and 13 percent. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

FIG. 13.4. Global inequality regimes, 2018: The bottom 50 percent versus the top 1 percent

Interpretation: The top centile’s share of total income is 30 percent in the Middle East compared with 9 percent for the bottom 50 percent. In Europe, these two shares are 21 and 11 percent; in China, 15 and 14 percent; and in the United States, 20 and 13 percent. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

These regional differences are important and instructive, and they may be helpful for understanding what kinds of social and fiscal institutions are useful for keeping inequality down (as Europe has done). Bear in mind, however, that inequality levels are high and rising nearly everywhere (including in Europe).1 Hence it is not a very good idea to use such data to explain to Europe’s lower and middle classes that, because their lot is so enviable compared to the rest of the world, they must make sacrifices. Unfortunately, people at the top of the global income and wealth distribution (and the politicians they support) often invoke such arguments to justify sacrifices in their favor. Rhetoric of this kind may be politically effective, but it is also dangerous. Most Europeans are perfectly well aware that the level of inequality in Europe is lower than in South Africa, the Middle East, Brazil, and the United States. To argue that immutable laws of economics require them to accept the kinds of inequality that exist elsewhere (a totally fantastic and baseless assertion, which in no way helps to clarify the issues) is surely the best way to persuade them to turn against globalization.

A more relevant comparison for European citizens is to note that while income inequality in Europe decreased considerably over the course of the twentieth century, it has increased sharply since the 1980s.2 To be sure, the increase has been smaller than that observed elsewhere, but it still represents a clear and well-documented reversal of the previous trend, for which there is no obvious justification. Indeed, the increase of inequality has coincided with a decrease in the growth rate.3 Furthermore, inequality remains extremely high in absolute terms. In fact, the concentration of wealth in Europe has always been stunning, and it has been increasing since the 1980s: the bottom 50 percent owns barely 5 percent of the wealth, while the top 10 percent owns 50–60 percent.4

Turning now to the regions of the world where inequality is highest, it is interesting to note that they contain several distinct types of political-ideological regime (Fig. 13.2).5 First, one finds countries with a legacy of status inequality and discrimination based on race, colonialism, or slavery. This is the case in South Africa, which ended apartheid in the early 1990s, and in Brazil, which was the last country to abolish slavery at the end of the nineteenth century.6 The racial dimension and history of slavery may also help to explain why the United States is more unequal than Europe and has had greater difficulty building social-democratic institutions.7

The Middle East: Pinnacle of Global Inequality

Sharing the pinnacle of the global inequality hierarchy is the Middle East, whose inequality has more “modern” roots in the sense that it is linked not to past racial divisions or a history of slavery but to the concentration of petroleum resources in small countries with modest populations compared to the region as a whole.8 This oil, exported around the world, is being transformed into permanent financial wealth via financial markets and the international legal system. This sophisticated system is the key to understanding the exceptional level of inequality in the region. For instance, Egypt, a country of 100 million people, annually spends on its schools 1 percent of the combined petroleum revenues of Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Qatar, whose populations are tiny.9

Inequality in the Middle East is also closely connected to the borders laid down by the French and British at the end of World War I as well as to the military protection that Western powers subsequently provided to the oil monarchies. Without that protection, the political map would probably have been redrawn several times, notably after the invasion of Kuwait by Iraq in 1990.10 The 1991 military intervention, whose purpose was to restore Kuwait’s oil to its emirs and to promote Western interests, coincided with the collapse of the Soviet Union, which facilitated Western intervention (now that there was no longer a rival superpower to contend with). These events marked the beginning of the new political-ideological era of hypercapitalism. They also illustrate the fragility of the compromise that was struck at the time. A few decades later, the Middle Eastern inequality regime epitomizes the explosive mixture of archaism, hyper-financialized modernity, and collective irrationality typical of recent times. It bears traces of the logic of colonialism and militarism; it contains reserves of petroleum that would be better kept in the ground to prevent global warming; and its wealth is protected by the extremely sophisticated services of international lawyers and financers, who find ways to put it beyond the reach of covetous have-nots. Finally, note that the oil monarchies of the Persian Gulf are, together with postcommunist Russia, the countries that make most extensive use of the world’s tax havens.11

The estimates of Middle Eastern inequality shown in Fig. 13.2 should be seen as lower limits owing to the limitations of the available sources and the hypotheses needed to interpret them. The measurement of inequality in the Middle East is complicated by the extreme difficulty of obtaining data about income and wealth, particular in the oil monarchies. The evidence suggests, however, that wealth in these states is very highly concentrated, both within the native population and between natives and foreign workers (who make up 90 percent of the population of Qatar, the Emirates, and Kuwait and 40 percent of the population of Saudi Arabia, Oman, and Bahrain). For want of sufficient data, the estimates given here are based on very conservative hypotheses about within-country inequalities; it is primarily the very wide gaps between countries that give rise to the differences depicted here. By adopting alternative (and very likely more realistic) hypotheses, one would arrive at estimates of top decile shares on the order of 80–90 percent (rather than 65–70), especially for Qatar and the Emirates—a level of inequality close to that of the most inegalitarian slave societies ever observed.12

There is little doubt that the extreme inequality observed in the Middle East has heightened tensions and contributed to the region’s persistent instability. In particular, the wide gap between the reality of the situation and officially proclaimed religious values (based on principles of sharing and social harmony within the community of believers) is quite likely to provoke allegations of illegitimacy and lead to violence. In the abstract, a democratic federal regional organization such as the Arab League or some other political organization could allow wealth to be shared while coordinating vast investments in a better future for the region’s youth. For the time being, however, little has been done in this direction.13 Why not? Not only because of the limitations of the strategies of regional actors but also because the wider world lacks the requisite political and ideological vision. In particular, the Western powers as well as private interests in Europe and the United States see advantages in maintaining the status quo, especially when the oil monarchies buy their weapons and offer financial support to their sports teams and universities. Yet in this as in other cases, strict respect for existing power relations and property rights has failed to yield a viable model of development. Indeed, Western actors have every reason to look beyond their short-term financial interests in order to promote a democratic, social, federalist agenda that would allow these contradictions to be overcome. Ultimately, it was the refusal to contemplate new egalitarian postnational solutions that gave rise to reactionary and authoritarian political projects in Europe in the first half of the twentieth century; the same is true of the Middle East in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.14

Measuring Inequality and the Question of Democratic Transparency

Along with global warming, the rise of inequality is one of the principal challenges confronting the world today. Whereas the twentieth century witnessed a historic decline in inequality, its revival since the 1980s has posed a profound challenge to the very idea of progress. What is more, the challenge of inequality is closely related to the climate challenge. Indeed, it is clear that global warming cannot be stopped or at least attenuated without substantial changes in the way people live. For such changes to be acceptable to the majority, the effort demanded must be apportioned as equitably as possible. The need for fair apportionment of the effort is all the more obvious because the rich are responsible for a disproportionate share of greenhouse gas emissions while the poor will suffer the worst consequences of climate change.

For these reasons, the issue of democratic transparency regarding inequalities of income and wealth is of paramount importance. Without intelligible indices based on reliable and systematic sources, it is impossible to have a reasoned public debate at the national level, much less at the regional or global level. The data presented in this book are drawn in large part from the World Inequality Database (WID.world), an independent consortium supported by a number of research centers and international organizations whose main objective is precisely to facilitate public debate about inequality on the basis of the most complete available data.15 The information in the database is the result of systematic comparison of available sources (including national accounts, household surveys, tax and estate records, and so on). With this information we have been able to provide the first comprehensive map of global inequality regimes and their evolution. Note, however, that despite the best efforts of everyone involved, the currently available sources remain fragmentary and insufficient. The main reason for this is that the data made public by governments and statistical agencies suffer from considerable limitations. Indeed, economic and financial opacity have increased in recent years, especially with respect to accounting for capital income and financial assets. This may seem paradoxical at a time when modern information technology should in theory facilitate greater transparency. The failure in some cases reflects a veritable surrender by governments, fiscal authorities, and statistical agencies; more than that, it reflects a political-ideological refusal to take the issue of inequality seriously, particularly when it comes to wealth inequality.

Let us begin with the question of the indices used to describe and analyze the distribution of income and wealth. These should be as intuitive as possible so that everybody can understand them. That is why it is preferable to use indices such as the share of total income (or wealth) accruing to the bottom 50 percent, the middle 40 percent, and the top 10 percent. Every citizen can take from these figures a fairly concrete idea of what each distribution means (Figs. 13.2–13.4).

To compare inequality between countries, an especially simple and expressive index is the ratio between the share of the top 10 percent (or top 1 percent) and that of the bottom 50 percent. This reveals quite significant differences between countries. For instance, we find that the ratio of the top decile’s share of income to that of the bottom 50 percent is roughly eight in Europe, nineteen in the United States, and thirty-five in South Africa and the Middle East (Fig. 13.5). The ratio between the top centile’s share and that of the bottom 50 percent is currently about twenty-five in Europe, eighty in the United States, and 160 in the Middle East (Fig. 13.6). The advantage of this type of index is twofold: it is very easy to understand, and it can be directly related to fiscal and social policy. In particular, citizens can form their own opinions about how different tax rates might modify the distribution of income.16 The same is true if one looks at the concentration of wealth and the potential for wealth redistribution: the share of wealth claimed by different groups shows immediately how a redistribution of property rights would affect each group’s holdings.

By contrast, indices such as the Gini coefficient, often used in official inequality statistics, are much more difficult to interpret. The Gini coefficient is a number between zero and one, with zero representing total equality and one representing total inequality. It tells us nothing about which social groups are responsible for differences in the index over time or between countries. Broadly speaking, the Gini coefficient masks flesh-and-blood social conflict between different groups in the income or wealth hierarchy and often obscures ongoing changes.17 For instance, inequality strongly increased between the middle and the top of the distribution at the global level since 1980 while it declined between the bottom and the middle, so that a synthetic indicator like the Gini coefficient could wrongly give the impression that we live in an era of complete distributional stability and balanced growth.18 Furthermore, the Gini coefficient is generally calculated on the basis of data that inherently tend to underestimate the degree of inequality—most notably, household surveys in which income and wealth are self-declared; such surveys often absurdly understate the income and wealth of people at the top of the distribution. For these reasons, indices like the Gini coefficient frequently conceal flaws (or outright aberrations) in the underlying data or at the very least cast a discreet veil over the difficulties involved.19

FIG. 13.5. Inequality between the top 10 percent and the bottom 50 percent, 2018

Interpretation: In 2018, the ratio of the average income of the top decile and that of the bottom 50 percent was 8 in Europe, 14 in China and Russia, 19 in the United States and India, 20 in Brazil, 34 in the Middle East, 35 in South Africa, and 36 in Qatar. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

FIG. 13.6. Inequality between the top 1 percent and the bottom 50 percent, 2018

Interpretation: In 2018, the ratio between the average income of the top centile and that of the bottom 50 percent was around 25 in Europe, 46 in China, 61 in Russia, 80 in the United States, 72 in India, 85 in Brazil, 161 in the Middle East, 103 in South Africa, and 154 in Qatar. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

Another frequently used approach is simply to ignore the part of the distribution that lies above a certain threshold, such as the ninetieth percentile (above which lies the top decile). One then divides the ninetieth percentile level by the median level (which corresponds to the fiftieth percentile) or the tenth percentile level (below which lies the bottom decile).20 The problem with this approach is that it amounts to neglecting a significant part of the distribution: the top decile’s share of total income is generally 30–70 percent, but its share of total wealth is generally 50–90 percent. If such a large share of income or wealth is simply swept under the rug, the transparency of democratic debate suffers, and the credibility of government statisticians and agencies is impaired.

On the Absence of Fiscal Transparency

Apart from the choice of indices, the most important question for the measurement of inequality is obviously the availability of sources. The only way to obtain a comprehensive view of inequality is to compare different sources (including national accounts, household surveys, and fiscal data), which shed complementary light on different segments of the distribution. Experience has shown that fiscal data, though highly imperfect, generally improve the quality of measurement substantially by correcting the data at the top end of the distribution (which surveys always seriously underestimate). This is true even in countries where the fiscal authorities lack the means to control fraud and where income tax data are rudimentary. For instance, as we saw in Chapter 12, although tax data from Russia and China are seriously incomplete and unsatisfactory, we were able to use this information to make substantial upward revisions to official inequality measures (based exclusively on surveys), yielding more plausible (though still probably low) estimates. In India and Brazil, thanks to the help of many researchers, citizens, and journalists, governments and agencies recently agreed to open up previously inaccessible records, and this has added to our knowledge of income inequality in those countries.21 Similarly, recent work on Lebanon, Ivory Coast, and Tunisia has shown that the use of tax data resulted in considerable improvement over previously available measures of inequality.22 In all these countries, data from current income tax reports—though flawed and disregarding the fact that much income probably goes untaxed—led to substantial upward revisions of official measures of inequality. It should therefore be clear that widely used official measures, based as they often are on self-declared household surveys, understate inequality to a significant degree, and this systematic distortion can substantially bias public debate.23

The use of tax sources, however imperfect, can also reveal poor enforcement of tax laws and inefficiency in their application. Research can thus equip society with the tools to mobilize and demand better fiscal enforcement. Take China, for example. If the authorities were to publish data on the number of taxpayers in each income bracket, in city after city and year after year, with details about the sources of income for those in the highest brackets, it would no doubt be possible to fight corruption more effectively than with the methods currently being used. Fiscal transparency links the measurement of inequality to the challenge of mobilizing people politically to transform the government.

Unfortunately, pressuring governments and tax authorities to open up their tax records is not enough to resolve all the problems. There is another issue: the evolution of the international fiscal and legal system has also reduced the quality of the available data. The free circulation of capital in conjunction with the absence of adequate international coordination on tax-related matters (and especially the lack of any requirement to share information about cross-border wealth holdings) has led some countries, especially in Europe, to adopt special preferential rules for taxing capital income (such as flat tax systems). In practice, this has resulted in a deterioration in the quality of sources that allow us to link an individual’s labor income to his or her capital income. This impoverishment of the European sources does not augur well for what is likely to happen in less wealthy countries. The difficulty of measuring income inequality is only compounded when it comes to measuring wealth inequality, about which even less is known, as we will see shortly.

Social Justice, Climate Justice

Let us take a closer look at the notion of income, whose inequality we are trying to measure, and in particular at the difficulties we encounter when we try to account fully for the degradation of the environment. To measure a country’s economic prosperity, it is broadly preferable to rely on national income rather than GDP. Recall the key differences between the two: national income is equal to GDP minus depreciation of capital (also called consumption of fixed capital) plus net income from abroad (or minus net outflow, as the case may be). For example, a country whose entire population was occupied reconstructing a capital stock destroyed by a hurricane could have a high GDP but zero national income. The same would be true if all the country’s output went abroad to remunerate the owners of its capital. The notion of GDP reflects a production-centered view and does not worry about the degradation of capital (including natural capital) or about the distribution of income and wealth. For these various reasons, national income is clearly a more useful notion. It is also more intuitive: national income per capita corresponds to the average income that citizens of the country actually earn.24

The problem is that available estimates do not allow us to correctly measure the depreciation of natural capital.25 In practice, official national accounts do register an upward trend in the depreciation of capital. Globally, consumption of fixed capital amounted to slightly more than 10 percent of global GDP in the 1970s but rose to nearly 15 percent in the late 2010s.26 In other words, national income was about 90 percent of GDP in the 1970s but only 85 percent today.27 This rising depreciation reflects the accelerated obsolescence of certain types of equipment, such as machinery and computers, which need to be replaced more often today than in the past.28

In principle, these estimates should also include the consumption of natural capital. In practice, this runs into difficulties of several kinds. Consider, first, available estimates of annual extraction of natural resources from 1970 to 2020, including hydrocarbons (oil, gas, coal), minerals (iron, copper, zinc, nickel, gold, silver, etc.), and wood. It turns out that these flows were substantial (generally 2–5 percent of global GDP, depending on the year) and that they varied considerably with time (as prices changed) and country. Calculations are based on the annual value of the material extracted net of any replenishment (very slow for hydrocarbons and minerals, somewhat less so for forests). Many uncertainties bedevil the data.29

The first problem is to evaluate these flows in terms of market values, which is probably not the best choice. The social cost of natural resource extractions should be factored in, especially the impact of CO2 and other greenhouse gas emissions on global warming. Such estimates are by their nature highly uncertain. In 2007, the Stern Review estimated that global warming could eventually reduce global GDP by 5 to 20 percent.30 The acceleration of global warming over the past decade could lead to even larger snowball effects.31 As noted in Chapter 12, it is not clear that it always makes sense to try to quantify things in monetary terms. In this case, it might be a better idea to set climate targets that are not to be exceeded and then to deduce the consequence in terms of maximum permissible emissions and the policies needed to meet that goal, including (but not limited to) setting a “price on carbon” and imposing a carbon tax on the worst polluters. In any case, it is essential to reason in the future in terms of national income rather than GDP growth and to account for the consumption of fixed capital on the basis of plausible estimates of the true social cost of natural resource extraction (possibly with a range of estimates based on different methodologies).32

The second difficulty is that national accounts as developed to date include natural resources only from the point at which they begin to be exploited economically. In other words, if a company or a country begins exploiting a deposit in 2000 or 2010, the value of the reserves in question generally appears in estimates of public or private wealth in official national accounts only as of 2000 or 2010.33 It will not appear in estimates for 1970 or 1980, even though the deposit in question was obviously already there. This has the potential to severely distort the measure of the evolution of total private wealth (as a percentage of national income or GDP) over the entire period.34 Research under way in countries rich in natural resources (such as Canada) shows that this is enough to completely transform the long-term picture; some data series need to be recalculated retrospectively.35 This illustrates once again a conclusion I have already emphasized several times—namely that the increase in the total value of private property often reflects an increase in the power of private capital as a social institution and not an increase in “the capital of mankind” in the broadest sense.

We encounter the same set of issues with respect to the private appropriation of knowledge. If a company were some day to obtain the rights to the Pythagorean theorem and begin collecting royalties from every schoolchild using it, its stock market capitalization would probably be substantial, and total global private wealth would increase accordingly, even more so if other aspects of human knowledge could be similarly appropriated. Nevertheless, mankind’s capital would not increase one iota, since the theorem has been known for millennia. This hypothetical case might seem extreme, but it is not dissimilar to that of private companies like Google, which has digitized public libraries and archives, opening up the possibility of some day billing for access to resources that were once free and public and thereby generating significant profits (potentially far beyond the investment required). Indeed, the stock market value of technology firms includes patents and knowhow that might not exist were it not for basic research financed with public money and accumulated over decades. Such private appropriation of common knowledge could increase dramatically in the coming century. What happens will depend on the evolution of legal and tax systems and on the social and political response.36

On Inequality of Carbon Emissions Between Countries and Individuals

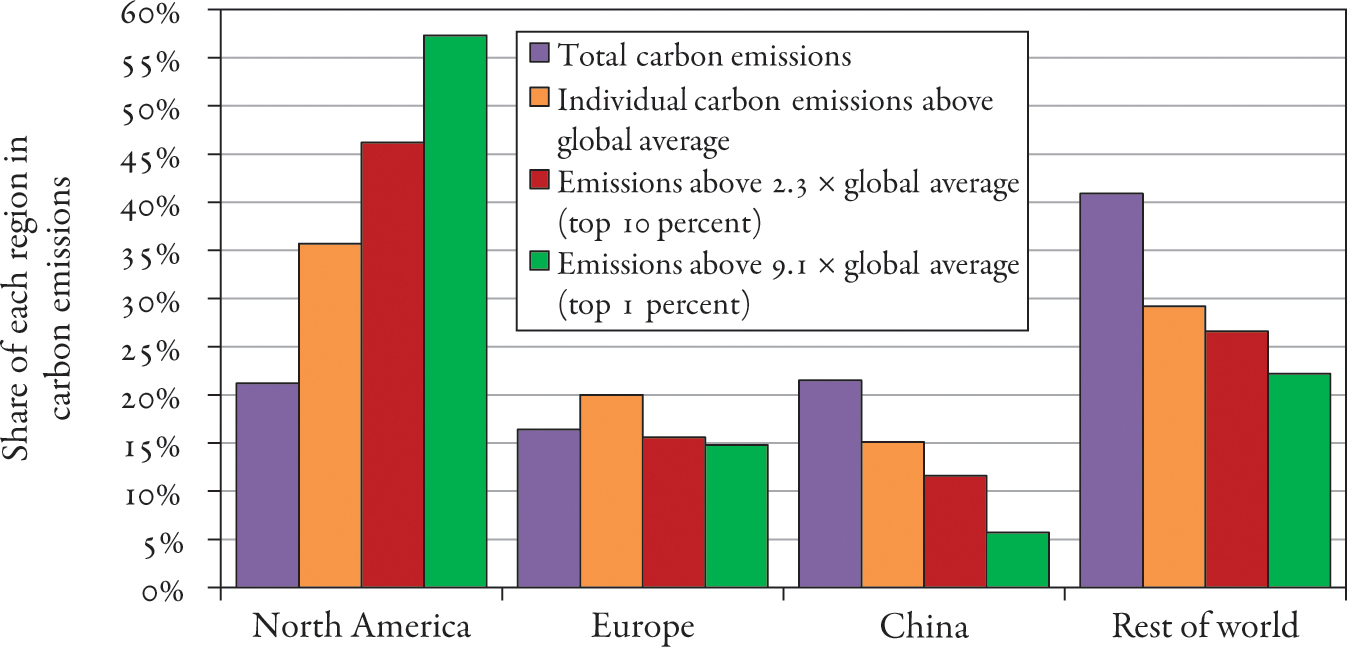

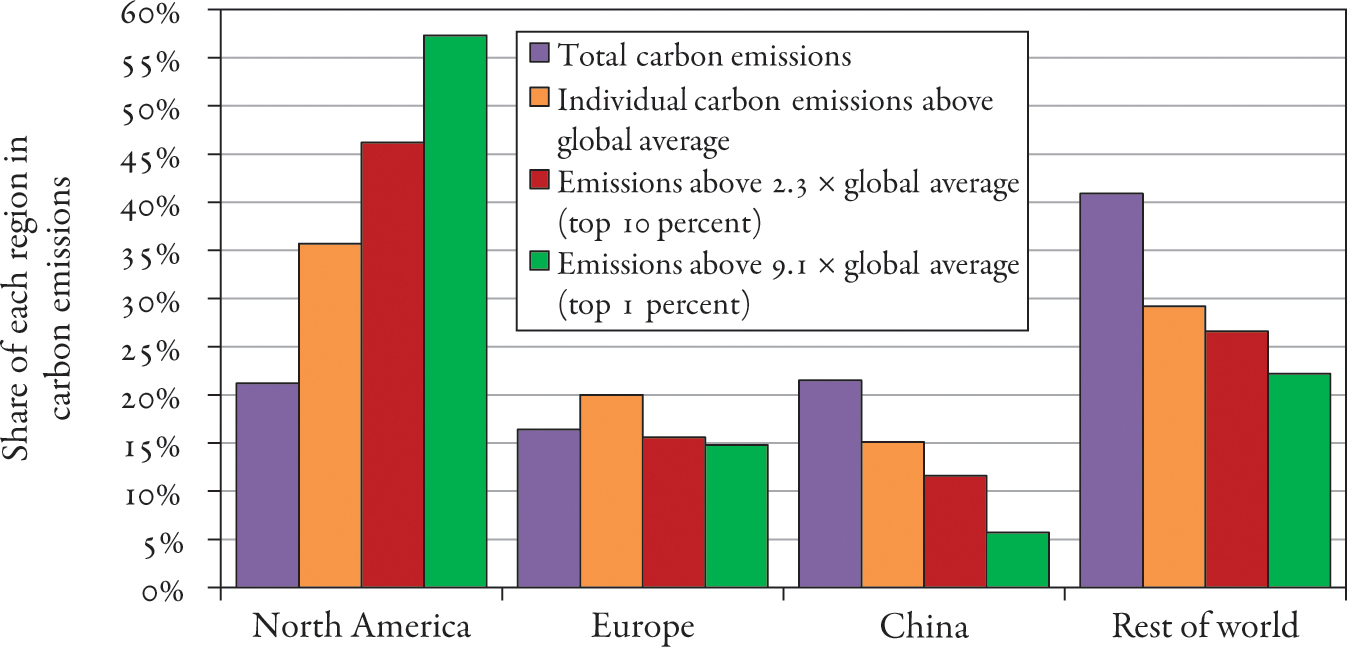

Finally, the third and probably most important difficulty is that it is imperative to take environmental inequalities into account, both in terms of damages caused and damages suffered. In particular, carbon emissions are not solely the responsibility of the countries that produce hydrocarbons or the countries that host factories generating significant emissions. Consumers in the importing countries, particularly the wealthiest of them, bear part of the responsibility as well. By using available data on the income distribution in various countries together with surveys that allow us to associate income with consumption profiles, it is possible to estimate how responsibility for carbon emissions is distributed among the world’s people. The principal results are shown in Fig. 13.7. These estimates reflect both direct emissions (from transportation and home heating, for example) and indirect emissions; that is, emissions incurred in the use and production of goods consumed by individuals in different countries as well as in the shipment of those goods from the place of origin to the place of consumption.37 Looking at all carbon emissions in the period 2010–2018, we find that North America and China are each responsible for about 22 percent of global emissions, Europe for 16 percent, and the rest of the world for about 40 percent. But if we focus on individuals responsible for the heaviest emissions, the distribution changes completely. The 10 percent of the world’s people responsible for the highest emissions emit on average 2.3 times the global average; together they account for 45 percent of global emissions. Of these emissions, North America represents 46 percent, Europe 16 percent, and China 12 percent. If we look at emissions greater than 9.1 times the global average, which gives us the top centile of emitters (who account for 14 percent of total emissions, more than the bottom 50 percent combined), North America (essentially the United States) represents 57 percent, versus 15 percent for Europe, 6 percent for China, and 22 percent for the rest of the world (including 13 percent for the Middle East and Russia and barely 4 percent for India, Southeast Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa).38

FIG. 13.7. The global distribution of carbon emissions, 2010–2018

Interpretation: The share of North America (United States and Canada) in total (direct and indirect) carbon emissions is 21 percent on average in 2010–2018 but 36 percent if one looks at individual emissions greater than the global average (6.2 tonnes CO2 per year), 46 percent for emissions above 2.3 times the global average (the top 10 percent of world emitters, responsible for 45 percent of all emissions, compared to 13 percent for the bottom 50 percent of world emitters), and 57 percent of those emitting more than 9.1 times the global average (the top 1 percent of emitters, responsible for 14 percent of all emissions). Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

This extremely high concentration of the highest emitters in the United States is a result of both higher income inequality and a way of life that is particularly energy intensive (owing to large homes, highly polluting vehicles, and so on). Of course, these results alone will not persuade people around the world to agree on who should make the greatest effort. In the abstract, given the facts about who is to blame, it would not be illogical for the United States to compensate the rest of the world for the damage it has done to global well-being, which is potentially considerable (bearing in mind that global warming may eventually lead to a loss of 5–20 percent of global GDP, if not more). In practice, it is quite unlikely that the United States would spontaneously undertake to do this. By contrast, it is not totally fanciful to think that the rest of the world might some day demand an accounting and impose sanctions to compensate for the damage it has suffered. To be sure, the extent of the damage due to global warming is such that this could lead to violent political tensions between the United States and the rest of the world.39 In any case, the search for a compromise and for norms of justice acceptable to the majority will necessitate shared awareness of how emissions are distributed globally.

The high level of individual emissions inequality also has consequences for climate policy at the national level. It is often argued that the best way to combat global warming is to levy a carbon tax proportional to emissions together with setting building and pollution standards and investing in renewable energy. For instance, a recent report suggested that carbon dioxide emissions should be taxed at a rate of up to $100 a ton between now and 2030 to meet the criteria set by the Paris Accords of 2015.40 That is, each country should set up an additional tax of $100 per ton on all emissions.41 The problem with such a proportional tax on carbon is that it can be quite socially unjust, both within and between countries. In practice, many households with low to middling incomes are required to spend a higher proportion of their income on transportation and heating than are wealthier households, particularly in areas where there is inadequate or no mass transportation or where homes are not insulated. A better solution would be to levy a higher tax on those who produce higher levels of emissions. For instance, one might offer an exemption to households emitting less than the global average and place a tax of $100 a ton on emissions above the average, then $500 a ton on emissions above 2.3 times the average and $1,000 (or more) on emissions above 9.1 times the average.

I will come back to the question of a progressive carbon tax in Chapter 17, where I consider what a just tax system might look like. At this stage, note simply that no policy will succeed in combating global warming unless it tackles the issues of social and fiscal justice. There are several ways to work toward a progressive, durable, and collectively acceptable carbon tax. At a minimum, all proceeds of the carbon tax must be put toward financing the ecological transition, particularly by compensating the hardest-hit low-income families. One could also explicitly exempt electricity and gas consumption up to a certain threshold and impose higher taxes on those consuming more than the limit. And one could set higher taxes on goods and services associated with elevated emissions: air travel, for example.42 What is certain is that if one does not take inequality seriously, major misunderstanding is likely, and this could block any hope of achieving an effective climate policy.

In this respect, the so-called revolt of the gilets jaunes, or yellow vests, in France in late 2018 is especially emblematic. The French government had planned to increase its carbon tax sharply in 2018–2019 but chose to abandon the idea in the wake of this violent protest movement. The affair was particularly badly handled, almost to the point of caricature. Only a small part (less than a fifth) of the additional carbon tax revenues were to be applied to the ecological transition and measures of compensation, with the rest going to finance other priorities, including major tax cuts for the social groups with the highest income and greatest wealth.43

Note, too, that the various forms of carbon tax currently levied in France and Europe contain numerous exemptions. For instance, kerosene is totally exempt from the carbon tax under European competition rules. What this means is that people of modest means who drive to work every morning must pay the full carbon tax on the gasoline they use, but wealthy people who fly off for a weekend vacation pay no tax on the jet fuel they consume. In other words, the carbon tax is not even proportional: it is hugely and blatantly regressive, with lower rates on those responsible for the highest emissions. Examples like this, widely publicized during the winter 2018–2019 protests in France, played an important role in persuading demonstrators that French climate policy was mainly a pretext to force them to pay higher taxes and that French and European authorities cared more about the haves than the have-nots.44 Of course, no matter what climate policy is adopted, there will always be people who oppose it. Clearly, however, it only strengthens the opposition if no effort is made to design a more just carbon tax. What this episode shows is once again the crucial need for new forms of transnational taxation, in this instance a true European tax system. If European governments continue to operate as they have always done—on the principle that the benefits of fiscal competition always outweigh the (real but manageable) costs and complications of a common tax policy—they will very likely face further tax revolts in the future and fatally compromise their climate policy. By contrast, the political movement to do something about climate change, which is gaining strength among the young, might change the political equation regarding democratic transparency and transnational fiscal justice.

On the Measurement of Inequality and the Abdication of Governments

It is paradoxical that in the so-called age of big data, public data on inequality are so woefully inadequate. Yet that is the reality, as is clear from the extreme difficulty of measuring the distribution of wealth. I alluded earlier to the inadequacy of the data on income distribution. The situation is even worse with respect to wealth, especially financial assets. To put it in a nutshell, statistical agencies, tax authorities, and, above all, political leaders have failed to recognize the degree to which financial portfolios have been internationalized and have not developed the tools needed to assess the distribution of wealth and to follow its evolution over time. To be clear, there is no technical obstacle to developing such tools; it is purely a political and ideological choice, the reasons for which we will try to unravel.

Of course it is possible, by exploiting and systematically comparing all currently available sources (national accounts, survey data, and tax records), to paint in broad strokes the way in which the concentration of wealth has evolved in the various regions of the world. The main results are shown in Figs. 13.8 and 13.9, which describe the evolution of the top decile and top centile shares of total wealth in France, the United Kingdom, the United States, India, China, and Russia. The oldest series are from France, where abundant estate tax records enable us to trace the history all the way back to the French Revolution (see Chapter 4). The available sources concerning the United Kingdom and other European countries (such as Sweden) are less precise but also enable us to work back to the beginning of the nineteenth century (see Chapter 5). For the United States, the data take us back to the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and the quality improves after the creation of the federal estate tax in 1916. In India, the available sources (mainly surveys of estates) begin in the 1960s. In China and Russia, it is only since the wave of privatizations in the 1990s that it has become possible to analyze the evolution of the wealth distribution.

FIG. 13.8. Top decile wealth share: Rich and emerging countries

Interpretation: The top decile share of total private wealth (real estate, professional and financial assets, net of debt) has increased sharply in China, Russia, India, and the United States since the 1980s and increased to a lesser degree in the United Kingdom and France. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

FIG. 13.9. Top centile wealth share: Rich and emerging countries

Interpretation: The top centile share of total private wealth (real estate, professional and financial assets, net of debt) has increased sharply in China, Russia, India, and the United States since the 1980s and increased to a lesser degree in the United Kingdom and France. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

The big picture is relatively clear. In the Western countries, the concentration of wealth diminished sharply after World War I and remained low until the 1970s, then turned upward in the 1980s.45 Wealth inequality rose more in the United States and India than in France or the United Kingdom, as did income inequality. The increase in the concentration of wealth was particularly large in China and Russia in the wake of privatization. While this overall pattern is well established, it is important to keep in mind that there are many aspects of recent developments that remain unclear. Paradoxically, the data in Figs. 13.8–13.9 for the last three decades (1990–2020) are undoubtedly less accurate than the data for the entire period (1900–2020). This is partly because the quality of the sources is not as good as it used to be and partly because the authorities have not developed the tools needed to follow the internationalization of wealth.

As for income, the sources from which we can glean information about wealth are of several kinds. First, there are national accounts: by combining the balance sheets of firms with many surveys and inventories of production, wages, housing, and so on, statistical agencies produce estimates of GDP, national income, and financial and nonfinancial assets held by households, governments, and firms. In addition to problems associated with accounting for the degradation of national capital, which I discussed earlier, the main limitation of the national accounts is that, by design, they are concerned only with aggregates and averages and not with distribution. Nevertheless, they do provide the most complete and internationally comparable estimates of both total national income and total private and public wealth, and it is natural to begin with these totals before delving into their distribution. Household surveys are one of the main sources for studying distributions. Their strength is that they pose dozens of questions about the composition of income and wealth as well as other individual characteristics not generally available in tax data (such as level of education and professional and family background). The disadvantage is that the answers that respondents give, in the absence of any sanction or verification, are often inaccurate, particularly at the top end of the distribution where income and wealth are generally hugely understated. This is already highly problematic when it comes to measuring income inequality, but with wealth, which is much more highly concentrated (with the top decile generally holding 50 to 90 percent), it is clearly crippling.

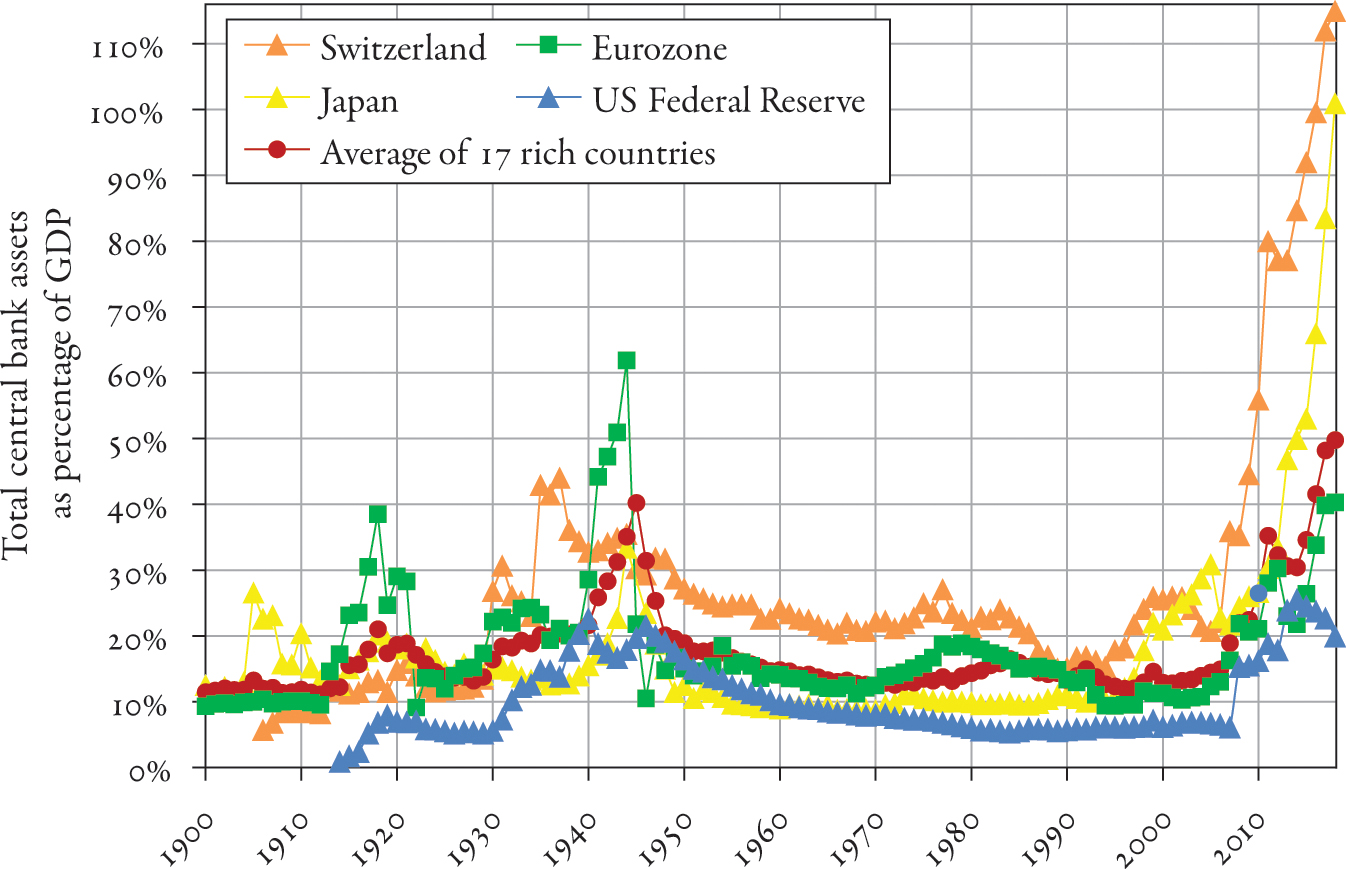

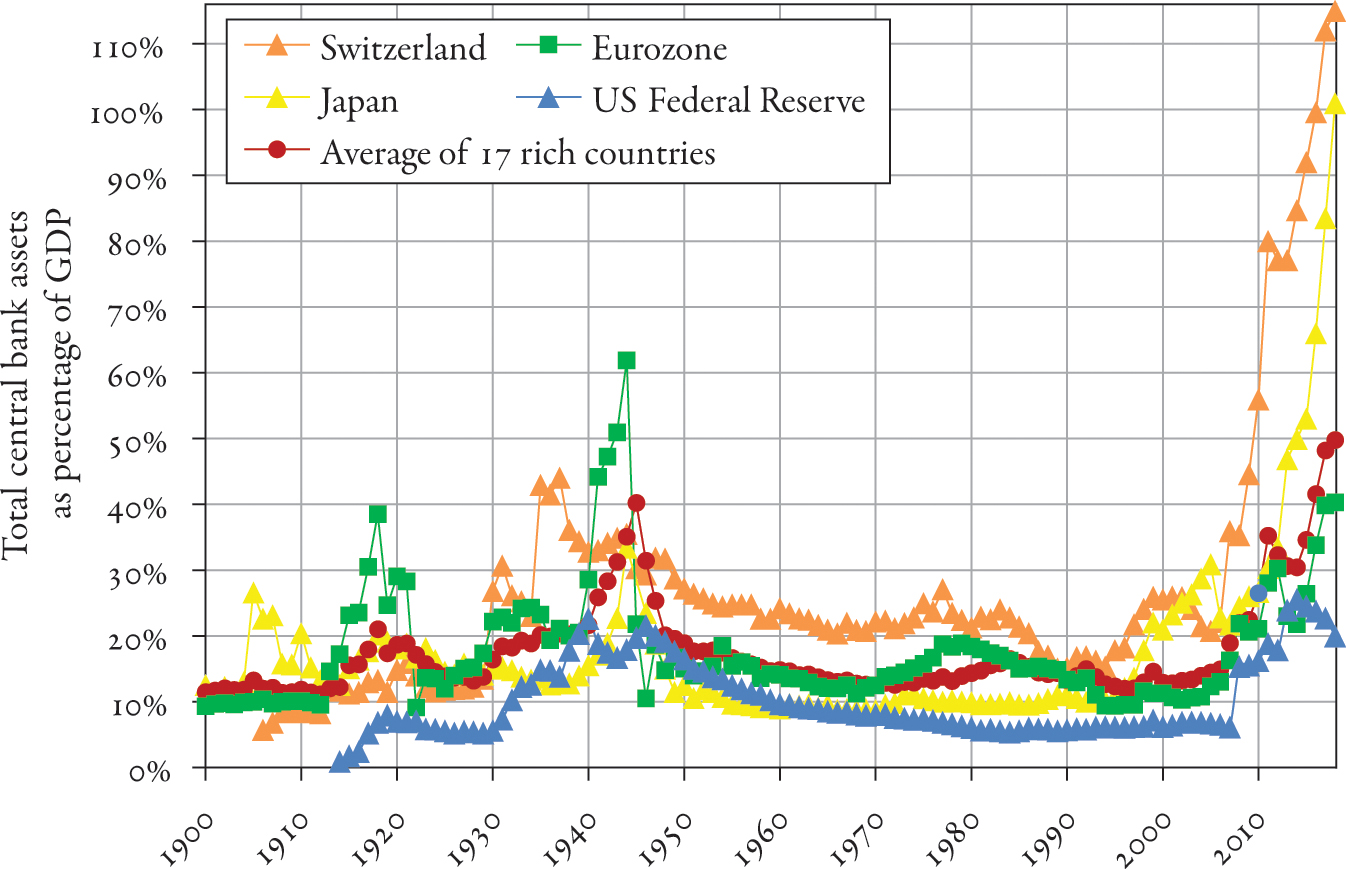

The most important surveys of wealth are conducted jointly by statistical agencies and central banks. This makes sense, given that central banks are the public institutions most directly concerned with the evolving structure of assets and liabilities. The monetary and financial policies of central banks have a major influence on the evolution of asset prices and yields as well as on their distribution at the individual level on the one hand and the firm and government level on the other. The oldest and most complete wealth survey is the Survey of Consumer Finances, which the US Federal Reserve has conducted every three to four years since the 1960s with tens of thousands of participating households. In Europe, the European Central Bank (ECB) has since 2006 coordinated wealth surveys in the various countries of the Eurozone with an eye to harmonizing methods and questionnaires, which were totally incompatible prior to the creation of the euro in 1999–2002.46 In both the United States and Europe, central bank statisticians have made real efforts to improve the reliability of these surveys. Unfortunately, the task is beyond their reach. It is unfortunately impossible to measure the distribution of wealth, especially financial assets, properly on the basis of self-declared surveys. Despite all the efforts to improve the results, the total wealth declared in the Household Finance and Consumption Survey (HFCS) coordinated by the ECB is at most 50–60 percent of the total estimated in national accounts. This is primarily the result of understatement of wealth by respondents at the top of the distribution, particularly in regard to financial assets. In a nutshell, the ECB prints hundreds of billions of euros (indeed, trillions of euros, as we will see later) to influence the European economy and the formation of asset prices, but it does not know how to measure the distribution of all that wealth correctly.

Overcoming Opacity: A Public Financial Register

What is particularly distressing about this situation is that the problem can easily be solved by developing better tools. Indeed, it would suffice to correlate survey data with data from financial institutions and tax authorities concerning financial assets. Real estate ownership has long been recorded not only in deed registries but also by tax authorities charged with collecting the property tax in the United States or the real estate tax (taxe foncière) in France. One of the main institutional innovations of the French Revolution was to establish a national cadastre (property register) covering all real estate (agricultural and nonagricultural land, homes, buildings, warehouses, factories, shops, offices, and so on). Similar reforms were introduced in most countries: in a sense, this marked the birth of ownership society. The centralized state assumed responsibility for recording and protecting property rights, supplanting the noble and clerical classes that had previously regulated power and property relations in premodern trifunctional societies (see Chapters 3–4). This process coincided with the development of the legal infrastructures required to organize relations of exchange and production on a wider scale than in the past.

Financial assets are in fact recorded in various ways that could be tracked. The problem is that governments have largely left responsibility for this in the hands of private financial intermediaries. In each country (or continent) there are private institutions that serve as central repositories (custodian banks) for financial assets. Their function is precisely to keep track of the ownership of nonphysical assets issued by companies (such as stocks, bonds, and other financial instruments). The goal is to make sure that no two individuals can both claim ownership of the same financial assets, which for obvious reasons would complicate the workings of the economy. The best known custodian banks are the Depository Trust Company in the United States and Clearstream and Eurostream in Europe.47 The fact that this function is discharged by private companies, which incidentally have in recent years drawn complaints about the opacity of their operations, raises a number of problems. Governments in the United States and Europe could easily decide to nationalize them or at a minimum to regulate them more closely to establish a true public register of financial assets. They could then establish rules to allow the identification of the ultimate holders of each asset (that is, the physical person exercising effective control, beneath the veil of shell companies and other complicated financial structures), which is not always the case today because of the way custodian banks operate.48

While it would be desirable for such a financial register to cover the widest possible expanse of territory—Europe, say, or Europe and the United States, or Europe and Africa, and ultimately the entire globe—it is important to point out that each state can make progress toward the final goal without waiting for others to act. Specifically, each country can immediately impose regulations on companies doing business within its borders. Each government could, for instance, require companies to provide detailed information about their stockholders. Indeed, rules of this sort exist already for both listed and unlisted firms, but they could be significantly reinforced and systematized in light of the possibilities offered by new information technologies.

Furthermore, tax authorities have for a long time required banks, insurance companies, and financial institutions to transmit information about interest, dividends, and other financial income received by taxpayers. In many countries, this information appears automatically in pre-filled tax statements sent to taxpayers for verification along with information about other third-party income (such as wages and pensions). The new technology makes it possible to automate monitoring procedures that were previously hit-and-miss. In principle, technology should make it possible to tabulate detailed information about financial income and the assets from which it derives. This information could be used both to ensure more efficient tax collection and to produce statistics on the distribution of wealth and its evolution.

To date, however, political choices have limited the potential positive effects of new technology. For one thing, bank reporting requirements often omit various forms of financial income subject to special rules.49 Exemptions of this kind seem to have proliferated in recent decades, especially in Europe. In some cases, income from financial assets is taxed separately at a flat rate rather than the progressive rates applicable to other types of income (especially wages).50 In theory, it should be entirely possible to separate the mode of taxation from the transmission of information. In practice, whenever financial income of a certain type—and especially a flat tax—is made subject to special rules, the relevant information generally disappears from tax statements and published statistics, thus decreasing the quality of the public data and democratic transparency as to capital income, even though modern information technology should have the opposite effect.51 On top of that, there has been a clear degradation of the quality of inheritance data (which in some cases is disappearing), so it is no exaggeration to say that published wealth statistics have become much poorer in recent years.

Furthermore, the automatic transmission of information from banks to tax authorities is generally limited to the income from financial assets, whereas it could easily include information about the assets themselves. In other words, using information from financial institutions and real estate registries, the tax authorities could easily compile pre-filled wealth statements, just as the French authorities do now with income statements. Instead, the ECB and European statistical agencies rely entirely on self-declared wealth surveys so that it is completely impossible to track the evolution of the composition of wealth (and especially financial assets) in the Eurozone; hence the ECB cannot even study the effects of its own policies. We find the same statistical backwardness in the United States. The Federal Reserve’s wealth surveys, although more homogeneous and of overall better quality than their European counterparts, also rely entirely on self-declaration with no verification against bank or administrative data, which greatly limits accuracy, particularly when it comes to tracking the portfolios of the wealthiest taxpayers.

On the Impoverishment of Public Statistics in the Information Age

This situation is all the more surprising in that the use of tax and administrative data has become standard practice in the measurement of the income distribution. In the United States, there is a very broad consensus around the idea that self-declared income declarations are not sufficiently accurate and must be complemented by tax data from filed income tax returns. Indeed, it was the use of tax data that established the very sharp increase of inequality after 1980 (an increase that was underestimated in survey data). In Europe, many statistical agencies recognized the limitations of self-declared income surveys and therefore decided decades ago to move to a mixed model. One starts with survey data, which provides social, demographic, occupational, and educational data not available from tax records, but one then adds data from official tax records to provide accurate information about the income of the households responding to the survey. Since these official records reflect data transmitted by firms, government agencies, and financial institutions to the tax authorities, this mixed model is widely seen as more reliable and satisfactory than the self-declared model.52 When it comes to wealth, however, the countries of Europe (as well as the United States) behave as though surveys alone suffice, even though the evidence shows that self-declared wealth is even less reliable than self-declared income.

How can we explain this, and, more generally, how can we explain why the era of “big data” and modern information technology has also witnessed an impoverishment of public statistics, especially regarding the measurement of wealth and its distribution?

Note first that this is a complex phenomenon, with multiple causes. For instance, when tax authorities moved to digital technology in the 1980s, this was in some cases accompanied by a paradoxical loss of statistical memory.53 In my view, however, another piece of the explanation has to do with a certain political fear of transparency and the demands for redistribution that might result from it. Indeed, to lend credibility to the system I have just described (combining a public financial register with pre-filled wealth declarations), it would be ideal to link it to a tax on wealth. In the beginning, this could be a simple registration fee (of 0.1 percent per year or less, for instance), which each asset owner would be required to pay to record his or her ownership of the asset and thus enjoy the protections of the national and international legal system. The government would then have the tool it needs to make the distribution of wealth transparent, and this information would become available for public debate and democratic deliberation, which might (or might not) lead to more substantial progressive wealth tax rates or other redistributive policies.54 Fear that events would take this course is, I think, one key reason why political leaders have been unwilling to support transparency about the distribution of wealth.

This unwillingness is extremely dangerous, I believe, not only for Europe and the United States but also for the rest of the world. Among other things, it takes away an essential tool for understanding the reality of inequality and developing policies to reduce it. These anti-democratic choices make it impossible to develop ambitious international egalitarian programs and ultimately hasten the retreat within the borders of the nation-state and the rise of identitarian reaction. Succinctly stated, if we do not acquire the transnational tools to reduce socioeconomic inequalities, and especially inequality of wealth, then political conflict will inevitably center on questions of national identity and borders. I will have much more to say about this in Part 4.

If the rejection of transparency is bad, how do we get beyond it? First, we need to gain a better understanding of its political-ideological roots. In general terms, the underlying ideology is fairly close to the proprietarian ideology that was dominant throughout the nineteenth and into the early twentieth centuries. Adherents stubbornly refused to open Pandora’s box by questioning the distribution of wealth, for fear that once opened, it could never be closed again. One of the novelties of today’s neo-proprietarianism is precisely that Pandora’s box was opened in the twentieth century as many countries experimented with a variety of redistributive solutions. In particular, the failure of communism is regularly invoked in both postcommunist and capitalist countries as an object lesson—a warning as to where any ambitious redistributive project is likely to end up. But this is to forget that the economic and social success of the capitalist countries in the twentieth century depended on ambitious and largely successful programs to reduce inequality, and in particular on steeply progressive taxes (Chapters 10–11). Why has this lesson been forgotten? Lack of historical memory is one reason, and disciplinary divisions in the academy are another, but these can be overcome. In the twentieth century, exceptional one-time levies on the largest fortunes (in real estate and above all financial assets) played a crucial role in eliminating existing public debt and turning attention from the past to the future, especially in Germany and Japan. It may be tempting to say that the circumstances were unique and that these experiences cannot be repeated. But the reality is that extreme inequality recurs again and again; to deal with it, societies need institutions capable of periodically redefining and redistributing property rights. The refusal to do so in as transparent and peaceful a manner as possible only increases the likelihood of more violent but less effective remedies.

Neo-Proprietarianism, Opacity of Wealth, and Fiscal Competition

Neo-proprietarianism refuses to be transparent about wealth. Opacity is maintained by a specific set of legal and institutional arrangements, which allow free circulation of capital but require no common system of registration or taxation of property. For much of the nineteenth century, proprietarianism depended on censitary suffrage; that is, limited property-qualified access to the polls. Only the wealthiest people enjoyed the right to vote so that the risk of political redistribution of property was quite limited. Today, the international neo-proprietarian legal regime complements constitutional protections of property rights and in a sense serves as a substitute for the censitary system. The refusal of transparency is sometimes justified by the idea that data about property ownership could be used in nefarious ways by dictatorial governments. In Europe, however, this argument has little weight. European banks have long shared information with their countries’ tax authorities, which enjoy reputations for neutrality in systems where the rule of law is unchallenged. The argument that transparency leads to government abuse reminds one of Montesquieu, the owner of the highly lucrative post of president of the Parlement of Bordeaux, who argued for maintaining the jurisdictional privileges of the nobility on the grounds that a centralized legal system would inevitably lead to despotism.55

A potentially more convincing argument, which has played a key role in the rejection of a common European tax system, is that taxes in Europe are already too high and that only intense fiscal competition among governments keeps them from increasing without limit. Besides being anti-democratic, this argument has numerous other problems. If Europeans could vote for common taxes in the framework of a common democratic assembly, it is by no means certain that they would vote for unlimited tax increases. It is just as likely that they would vote for a different tax system altogether: for example, a system that would tax high incomes and large fortunes more heavily in order to alleviate the burden on the lower and middle classes (a burden created by the continuous increase in indirect and direct taxes and contributions on wages and pensions). Bear in mind that there was enough trust among these same European states to establish a common currency and a powerful European Central Bank with the authority to create trillions of euros by simple majority vote of its Governing Council, with minimal democratic control. To reject transparency of ownership and common democratic taxes is particularly dangerous, since it also leaves the ECB itself in the position of conducting monetary policy without reliable data on the distribution of wealth in Europe and its evolution.56

In principle, progress toward greater transparency after the financial crisis of 2008 should have been facilitated by announcements made at various international summits (such as the G8 and G20) concerning the need to combat tax havens and fiscal opacity. Some countries did take concrete steps: for example, in 2010 the United States passed the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act, which in theory requires financial institutions around the world to transmit to relevant tax authorities all information concerning their customers’ bank accounts and asset holdings. In practice, such measures do not go far enough, however, and nothing has been done about replacing custodian banks with a public financial register. What efforts to date have demonstrated, though, is that progress is possible with adequate sanctions, such as the threat to cancel the licenses of Swiss banks to operate in the United States (which helped to eliminate some of the more glaring abuses). In this regard, Europe unfortunately stands out more for its declarations of good intentions than for real action. One important reason for this is that all decisions on tax matters in the European Union are stymied by the rule of unanimity.

In recent years Europe has been hit by a number of financial and fiscal scandals. For instance, in November 2014, the LuxLeaks story broke just as Jean-Claude Juncker was taking office as president of the European Commission. An international consortium of journalists published leaked documents from the period 2000–2012, which showed how the government of Luxembourg had entered into a series of confidential agreements (called tax letters) with private firms. Under the terms of these agreements, negotiated in private, large companies were granted the right to pay taxes below official rates (which were already quite low in Luxembourg). As it happens, the prime minister of Luxembourg from 1995 to 2013 was none other than Jean-Claude Juncker, who also served as the grand duchy’s finance minister and as president of the Eurogroup (the council of finance ministers of the Eurozone).

No one was really surprised to learn that Luxembourg countenanced tax evasion—nor did this discovery prevent the European People’s Party, an alliance of Christian Democratic and center-right parties, from designating Juncker as its candidate for the Commission presidency—but the scope of the practice was breathtaking. In Chapter 12, I noted that Chinese tax authorities publish no data to show that they are actually enforcing the ostensible tax code. What went on in Luxembourg was not very different. Caught red-handed, Juncker admitted the facts of the case. He explained in substance that while these practices may not have been very satisfactory from a moral point of view, they were perfectly legal under Luxembourg’s tax laws. In several interviews with European newspapers, he justified what was done on the grounds that Luxembourg had been hit hard by deindustrialization in the 1980s and needed a new development strategy for his country. What he hit upon was a strategy based on the banking sector, “tax dumping,” financial opacity, and siphoning of tax revenues from Luxembourg’s neighbors.57 He promised not to do it again, however, and the leading parties of the European Parliament (including not only his own center-right party but also the liberals and the social democrats sitting on the center-left) chose to reward him with their confidence.

Similar consortiums of journalists subsequently broke other scandals, including Swiss Leaks in 2015 and the Panama Papers in 2016–2017, which disclosed widespread use of tax havens and other occult practices. These revelations demonstrated the extent of the cheating, even in countries reputed for efficient tax administration, such as Norway. Using data from the Swiss Leaks and Panama Papers in conjunction with Norwegian tax records (which were made available for study) and data from random tax audits, researchers were able to show that tax evasion was rare among people with little wealth but amounted to nearly 30 percent of the taxes due on the largest 0.01 percent of fortunes.58

In the end, it is hard to know how these various affairs affected European public opinion, especially in the case of Juncker, who occupied the highest political office in the European Union from 2014 to 2019. What is certain is that no decision was taken in those years to develop a public financial register, to harmonize taxes on the most mobile taxpayers, or in a more general sense, to take steps to make sure that such scandals would not happen again. All this created the impression that the fight for fiscal justice and for higher taxes on major economic actors was not really a priority for the EU. This is dangerous, in my view, because it inevitably encourages anti-European sentiment among the lower and middle classes and provokes nationalist and identitarian reactions from which nothing positive can come.

On the Persistence of Hyperconcentrated Wealth

Let us return now to the measurement of the concentration of wealth and its evolution. In the absence of a public financial register and information from financial institutions, we have to make do with incomplete data. Combining household surveys with income and inheritance tax data is the best way to proceed. The curves shown in Figs. 13.8–13.9 for the United States, France, and the United Kingdom are based on this mixed method. To test the consistency of the results, we also compared them with data from the very top end of the distribution provided by magazines such as Forbes, which has been compiling annual lists of the world’s billionaires since 1987.

For the United States, the income tax method yields results quite close to those found by Forbes while the inheritance tax method yields a smaller (though still significant) increase (as does the uncorrected household survey).59 There are two apparent reasons for this: first, the inheritance tax has been less carefully audited than the income tax in the United States since the 1980s,60 and second, the so-called mortality multiplier method becomes less accurate as the population ages.61 The capitalization method applied to the income tax data also suffers from certain limitations, and the results obtained are not entirely satisfactory.62 In general, both methods (mortality multiplier and capitalization) are second-best solutions: it would be far better to have direct information from financial institutions and tax authorities about the wealth of living taxpayers rather than be forced to make inferences from the amount of capital income and size of estates. For the United Kingdom, the tax data on capital income have deteriorated so much since the 1980s that one has to rely on estate tax data alone, whereas up to the 1970s one can use both methods and compare the results for consistency.63 Finally, in the case of France, both methods yield similar evolutions, globally consistent with the Forbes classifications.64 There has, however, been a dramatic deterioration in the quality of the inheritance tax data for France in recent decades.65 To be sure, the situation is even worse in countries that have abolished the inheritance tax, where information is totally lacking.66

All in all, despite these difficulties, the curves shown in Figs. 13.8–13.9 for the United States, United Kingdom, and France over the last few decades can be considered to be reasonably consistent and accurate, at least to a first approximation. For the other countries shown (China, Russia, and India), there is no sufficiently detailed income tax data (and there is no inheritance tax data at all), so we are reduced to using the Forbes classifications to correct the household survey data at the top end of the distribution.

The results obtained probably bear some resemblance to reality, but I want to stress how unsatisfactory it is to have to rely on such a nebulous “source.” To be sure, published wealth rankings in all countries show dramatic changes in recent decades, and these changes on the whole seem consistent with what we are able to measure using other available sources. Note that, according to Forbes, the world’s largest fortunes have grown at a rate of 6–7 percent a year (correcting for inflation) from 1987 to 2017—that is, three to four times as fast as average global wealth and roughly five times as fast as average income (Table 13.1).

Obviously, such differences cannot persist indefinitely unless one assumes that the share of global wealth owned by billionaires will eventually approach 100 percent, which is neither desirable nor realistic. Most likely, a political reaction will set in well before this occurs. The spectacular growth of large fortunes may have been accelerated by the privatization of many public assets between 1987 and 2017, not only in Russia and China but also in the Western countries and around the world, in which case this evolution may slow in coming years (to the extent that there are fewer and fewer assets to privatize). The legal imagination being what it is, however, it may not be a good idea to count on this. Furthermore, the available data suggest that the gap was equally large in the two subperiods, 1987–2002 and 2002–2017, despite the financial crisis, which suggests that there are deep structural factors at work. It is possible that financial markets are structurally biased in favor of the largest portfolios, which are able to earn real returns higher than others—as high as 8–10 percent a year for the largest US university endowments in recent decades.67 Furthermore, all available evidence suggests that the world’s largest fortunes have made very advantageous use of clever tax-avoidance strategies, which enable them to earn returns higher than smaller fortunes can.

The concepts and methods used by magazines like Forbes to establish these classifications are so vague and imprecise as to be useless for delving more deeply into these questions.68 The fact that the global debate about inequality is partly based on such “sources” and that even public authorities sometimes invoke them is symptomatic of a widespread failure of public institutions to meet the challenge of measuring wealth inequality.69 These are key democratic issues, however, and the public has begun to take notice of them, including in the United States. There, as I noted in Chapter 11, rising inequality has led to calls for more progressive taxes and in turn to demands for greater statistical transparency.70

|

The rise of top global wealth holders, 1987–2017 |

||||

|

Average real annual growth rate, 1987–2017 (corrected for inflation) |

World |

US, Europe, China |

||

|

The 1/100 millionth richest (Forbes) |

6.4% |

7.8% |

||

|

The 1/20 millionth (Forbes) |

5.3% |

7.0% |

||

|

The 0.01 percent richest (WID.world) |

4.7% |

5.7% |

||

|

The 0.1 percent richest (WID.world) |

3.5% |

4.5% |

||

|

The 1 percent richest (WID.world) |

2.6% |

3.5% |

||

|

Average wealth per adult |

1.9% |

2.8% |

||

|

Average income per adult |

1.3% |

1.4% |

||

|

Total adult population |

1.9% |

1.4% |

||

|

GDP or total income |

3.2% |

2.8% |

||

|

Interpretation: From 1987 to 2017, the average wealth of the 100 millionth richest people in the world (about thirty out of 3 billion adults in 1987 and about fifty out of 5 billion in 2017) grew by 6.4 percent a year globally, and the average person’s wealth grew by 1.9 percent a year. The skyrocketing of the largest fortunes was even more marked if one looks only at the United States, Europe, and China. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology. |

||||

FIG. 13.10. The persistence of hyperconcentrated wealth

Interpretation: The top decile of private wealth owners in Europe owned 89 percent of all private wealth (average of the United Kingdom, France, and Sweden) in 1913 (compared with 1 percent for the bottom 50 percent), 55 percent in Europe in 2018 (compared with 5 percent for the bottom 50 percent), and 74 percent in the United States in 2018 (compared with 2 percent for the bottom 50 percent). Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

To recapitulate, the resurgence of wealth inequality coupled with increased financial opacity is an essential feature of today’s neo-proprietarian inequality regime. Although the twentieth century witnessed a deconcentration of wealth that allowed the emergence of a patrimonial middle class, wealth remained quite unequally distributed, with the bottom 50 percent of the distribution owning a negligible share of the total (Fig. 13.10). The sharp increase of the top decile share, especially in the United States, reflects a gradual and worrisome erosion of the share owned by the rest of the population. The lack of diffusion of wealth is a central issue for the twenty-first century, which may undermine the confidence of the lower and middle classes in the economic system—not only in poor and developing countries but also in rich ones.

On the Persistence of Patriarchy in the Twenty-First Century

The hypercapitalist societies of the early twenty-first century are quite diverse. Of course, they are connected to one another by the globalized and digitalized capitalist system. But every country also bears traces of its own particular political-ideological trajectory, whether it be social-democratic, postcommunist, postcolonial, or petro-monarchical. Generally speaking, today’s inequality regimes combine elements of modernity and archaism. Some institutions and discourses are new, while others reflect a return to old beliefs, including a quasi-sacralization of private property.