{ TWELVE }

Communist and Postcommunist Societies

Thus far, we have analyzed the fall of ownership society between 1914 and 1945 and the way in which the social-democratic societies that were constructed in the period 1950–1980 entered a period of crisis in the 1980s. For all its successes, social democracy proved unable to cope adequately with the rise of inequality because it failed to update and deepen its intellectual and political approach to ownership, education, taxation, and above all the nation-state and regulation of the global economy.

We turn now to the case of communist and postcommunist society, primarily in Russia, China, and Eastern Europe. The goal is to analyze communist society’s place in the history and future of inequality regimes. Communism, especially in its Soviet form as the Union of Socialist Soviet Republics (USSR), was the most radical challenge that proprietarian ideology—its diametrical opposite—ever faced. Whereas proprietarianism wagered that total protection of private property would lead to prosperity and social harmony, Soviet Communism was based on the complete elimination of private property and its replacement by comprehensive state ownership. In practice, this challenge to the ideology of private property ultimately reinforced it. The dramatic failure of the Communist experiment in the Soviet Union (1917–1991) was one of the most potent factors contributing to the return of economic liberalism since 1980–1990 and to the development of new forms of sacralization of private property. Russia, in particular, became a symbol of this reversal. After three-quarters of a century as a country that had abolished private property, Russia now stood out as the home of the new oligarchs of offshore wealth—that is, wealth held in opaque entities with headquarters in foreign tax havens: in the game of global tax evasion, Russia became a world leader. More generally, postcommunism in its Russian, Chinese, and East European variants has today become hypercapitalism’s best ally. It has also inspired a new kind of disillusionment, a pervasive doubt about the very possibility of a just economy, which encourages identitarian disengagement.

We will begin by analyzing the Soviet case, especially the reasons for the failure of communism and the inability to imagine any form of economic or social organization other than hypercentralized state ownership. We will also study the Russian regime’s kleptocratic turn since the fall of Communism and its place in the global rise of tax havens. We will then look at the case of China, who took advantage of Soviet and Western failures to build a dynamic mixed economy with which it was able to make up the ground lost under Maoism. In addition, the Chinese regime raises fundamental questions for Western parliamentary democracies. The answers it proposes, however, require a degree of opacity and centralism incompatible with effective regulation of the inequalities produced by private property. Finally, we will examine the postcommunist societies of Eastern Europe, their role in the transformation of the European and global inequality regime, and the way in which they reveal the ambiguities and limitations of the economic and political system currently in place in the European Union.

Is It Possible to Take Power Without a Theory of Property?

To study the Soviet Communist experience (1917–1991) today is first of all to try to understand the reasons for its dramatic failure, which still weighs heavily on any new attempt to think about how capitalism might be overcome. The Soviet failure is also one of the main political-ideological factors responsible for the global rise of inequality in the 1980s.

The reasons for this failure are numerous, but one is obvious. When the Bolsheviks took power in 1917, their action plan was not nearly as “scientific” as they claimed. It was clear that private property would be abolished, at least when it came to the major industrial means of production, which in any case were relatively limited in Russia at that time. But how would the new relations of production and property be organized? What would be done about small production units and about the commercial, transport, and agricultural sectors? How would decisions be made, and how would wealth be distributed by the gigantic state planning apparatus? In the absence of clear answers to these questions, power quickly became ultra-personalized. When results failed to measure up to expectations, reasons had to be found and scapegoats designated, which led to accusations of treason and capitalist conspiracies against the Communist state. The regime then resorted to purges and imprisonments, which to some extent continued until its downfall. It is easy to proclaim the abolition of private property and bourgeois democracy but more complex (as well as more interesting) to draw up detailed blueprints for an alternative political, social, and economic system. The task is not impossible, but it requires deliberation, decentralization, compromise, and experimentation.

My purpose is not to blame Marx or Lenin for the failure of the Soviet Union but simply to observe that before the seizure of power in 1917, neither they nor anyone else had envisioned solutions to the crucial problems involved in organizing an alternative society. To be sure, in Class Struggles in France (1850) Marx did warn that the transition to communism and a classless society would require a phase of “dictatorship of the proletariat,” during which all means of production would need to be placed in the hands of the state. The term “dictatorship” was hardly reassuring. But in reality this formula really said nothing about how the state should be organized, and it is very difficult to know what Marx would have recommended had he lived to see the Revolution of 1917 and its aftermath. As for Lenin, we know that shortly before his death in 1924 he favored the New Economic Policy (NEP), which envisioned an extended period of reliance on a regulated market economy and private property (even if the modes of regulation remained largely undefined). Joseph Stalin, wary of anything that might slow the process of industrialization, chose to avoid these complexities: in 1928 he ended the NEP and ordered immediate collectivization of agriculture and full state ownership of the means of production.

The absurdity of the new regime became quite apparent in the late 1920s when the government moved to criminalize independent workers who did not fit readily into standard categories but were nevertheless essential to urban life and the Soviet economy. Among those stripped of civil rights (including the right to vote and, above all, the right to rations, which made survival difficult) were not only members of the old Tsarist military and clerical classes but also anyone “deriving income from private commerce or wholesale activities” as well as anyone “hiring a worker for the purpose of earning a profit.” In 1928–1929, some 7 percent of the urban and 4 percent of the rural population were thus included on so-called listenzii lists for engaging in prohibited activities. In practice, this measure targeted a whole population of carters, food sellers, craftsmen, and tradespeople.

In their applications for rehabilitation, which involved endless bureaucratic paperwork, these people described their “little lives” and scant possessions—nothing more than a horse and cart or a humble food stand—and professed their bewilderment at being targeted by a regime they supported and whose forgiveness they implored.1 The absurdity of the situation stemmed from the fact that it is obviously impossible to organize a city or a society solely with authentic proletarians, if “proletarian” is defined as a worker in a large factory. People need to eat, dress, move about, and find housing, and these things require large numbers of workers in production units of various sizes, sometimes quite small, which can be organized only in a fairly decentralized way. Society depends on each person’s knowledge and aspirations and sometimes requires small businesses funded with private capital and employing a handful of workers.

The 1936 Constitution of the USSR, promulgated at a time when it was believed that these deviant practices had been definitively eradicated, instituted “personal property” alongside “socialist property” (meaning state property, including collective farms and cooperatives strictly controlled by the state). But personal property consisted solely of possessions acquired with the income from one’s work, as opposed to “private property,” which consisted of ownership of the means of production and therefore implied exploitation of the work of others, which was completely banned, no matter how small the production unit. To be sure, exceptions to the rule were regularly negotiated: for instance, collective farmworkers were allowed to sell a small part of their production at farmers’ markets, and Caspian Sea fishermen were permitted to sell part of their haul for their own benefit. The problem was that the regime devoted considerable time to undermining and renegotiating its own rules, partly out of ideological dogmatism and wariness of subversive practices and also because it needed scapegoats and “saboteurs” to blame for its failures and for the frustrations of its people.

At the time of Stalin’s death in 1953, more than 5 percent of the adult Soviet population was in prison, more than half for “theft of socialist property” and other minor larceny, the purpose of which was to make their daily lives more bearable. This was the “society of thieves” described by Juliette Cadiot—a symbol of the dramatic failure of a regime that was supposed to emancipate the people, not incarcerate them.2 To find a similar incarceration rate, one would have to look at the black male population of the United States today (about 5 percent of adult black males are in prison). Looking at the United States as a whole, about 1 percent of the adult population was behind bars in 2018, enough to make the country the unchallenged world leader in this category in the early twenty-first century.3 The fact that the Soviet Union had an incarceration rate five times as high in the 1950s says a great deal about the magnitude of the human and political disaster. It is particularly striking to discover that the incarcerated were not just dissidents and political prisoners; the majority were economic prisoners, accused of stealing state property, which was supposed to be the means of achieving social justice on earth. Soviet prisons were full of hungry people who pilfered from their factories or collective farms: petty thieves accused of stealing a chicken or a fish and factory managers accused of corruption or embezzlement, often wrongly. Such people became targets of officials determined to brand “thieves” of socialist property as enemies of the people and were subject to five to twenty-five years of hard labor for minor thefts and capital punishment for more serious offenses. Interrogation and trial transcripts allow us to hear the voices and justifications of these alleged thieves, who do not hesitate to challenge the legitimacy of a regime that failed to keep its promise of improving living conditions.

It is interesting to note that one paradoxical consequence of World War II was that the Soviet regime briefly adopted a somewhat more expansive concept of private property, at least on the surface. This had to do with postwar Russian demands for indemnification and compensation for Nazi destruction and pillage in occupied parts of Russia between 1941 and 1944. Under international law at that time private losses would receive more generous indemnities than public losses. Soviet commissions therefore methodically set about collecting testimony about damage to private property, including losses by small production units that had supposedly been abolished by the constitution of 1936. In practice, however, this invocation of private property was essentially a rhetorical strategy that the regime deployed on the diplomatic and legal front, usually without direct consequences in terms of actual restitution to the individuals said to have suffered the losses.4

On the Survival of “Marxism-Leninism” in Power

Given these depressing results, it is natural to ask how the Soviet regime could have stayed in power for so long. Clearly its repressive capacity is part of the answer, but as with all inequality regimes, one must also consider its persuasive capacity. The fact is that “Marxist-Leninist ideology,” on which the Soviet ruling class relied to maintain itself in power, had, for all its weaknesses, a number of strengths. The most obvious was the comparison with the previous regime. Not only had the Tsarist regime been deeply inegalitarian; it had also failed dismally to develop Russia’s economy, society, and schools. The Tsarist government relied on noble and clerical classes directly descended from premodern trifunctional society. It abolished serfdom in 1861, only a few decades before the Russian Revolution of 1917. At that time serfs still accounted for nearly 40 percent of the population. At the time of abolition, the imperial government decreed that former serfs must pay an annual indemnity their former owners until 1910 in return for their freedom. The spirit was similar to that of the financial compensation awarded to slaveowners when the United Kingdom abolished slavery in 1833 and France in 1848, except that the serfs lived in the Russian heartland rather than on remote slave islands.5 Although most payments ended in the 1880s, the episode places the Tsarist regime and Russian Revolution in perspective by reminding us of the extreme forms that the sacralization of private property and the rights of property owners sometimes took before World War I (regardless of the nature and origin of the property).

With the Tsarist government as point of comparison, the Soviet regime had no difficulty portraying its project as one that held out greater promise for the future in terms of both equality and modernization. And in spite of repression, ultra-centralization, and state appropriation of all property, public investment in the period 1920–1950 clearly did lead to rapid modernization that brought the Soviet Union closer to Western European levels, especially in the areas of infrastructure, transportation, education (and literacy), science, and public health. Within a few decades the Soviet regime had considerably reduced the concentration of income and wealth while raising the standard of living, at least until the 1950s.

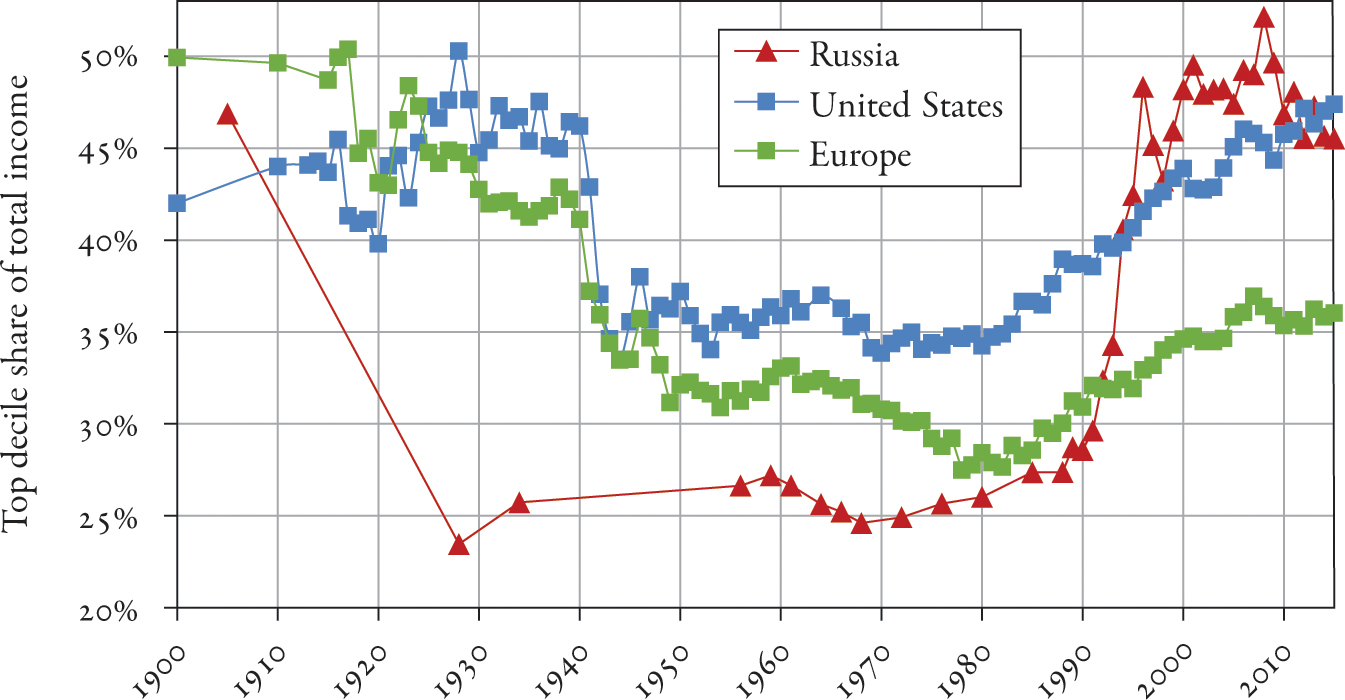

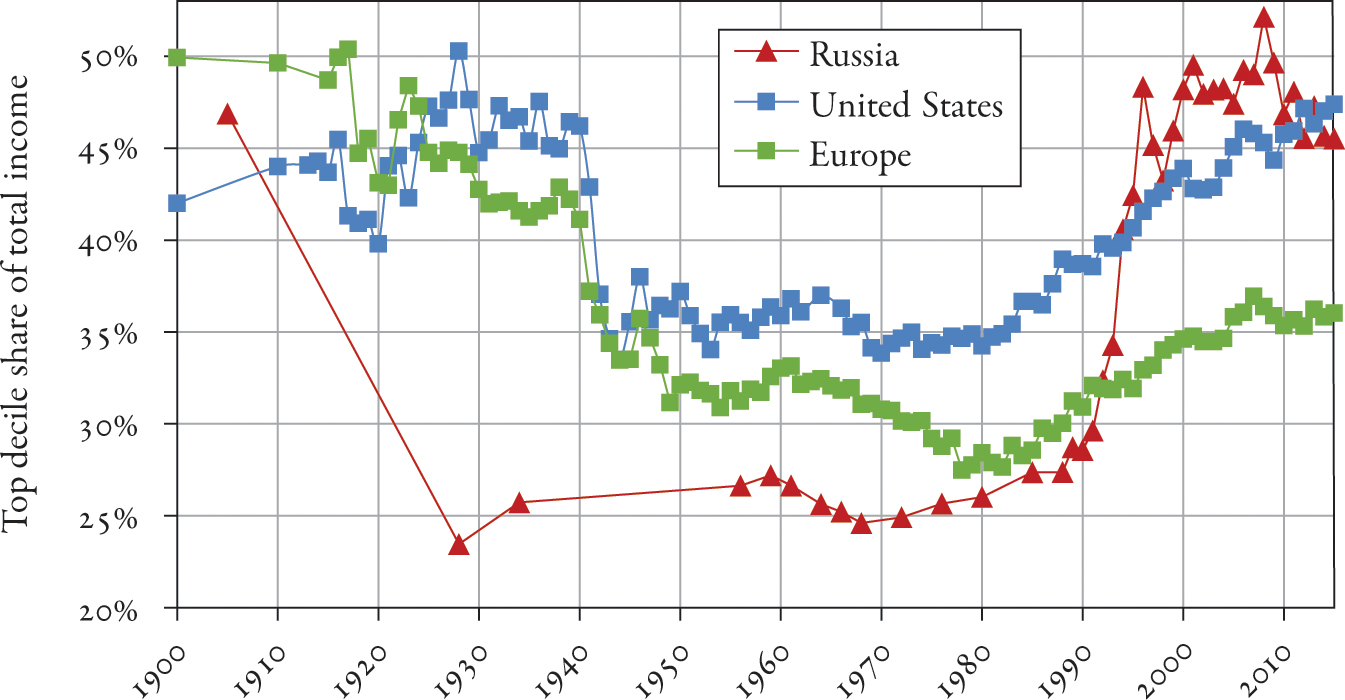

With respect to income inequality, recent work has shown that the top decile’s share of national income remained fairly low throughout the Soviet period, around 25 percent from the 1920s to the 1980s, compared with 45–50 percent under the Tsars (Fig. 12.1). The top centile’s share decreased to around 5 percent of total income in the Soviet era compared with 15–20 percent before 1917 (Fig. 12.2). To be sure, such estimates have their limits. The available data on monetary incomes have been corrected to reflect the in-kind benefits available to the privileged classes in the Soviet regime (including access to special stores, vacation centers, and so on), but such corrections are by their nature approximate.6 In the end, the data on income inequality in the Soviet period mainly demonstrate the fact that the Communist regime did not structure its inequalities around money. For one thing, capital income, which constitutes a large share of the income of high earners in other societies, was totally absent in the Soviet Union. For another, the pay differences between a worker, an engineer, and a government minister were relatively small.7 This was an essential characteristic of the new regime, which would have lost all internal ideological coherence and forfeited all legitimacy if it had begun paying its leaders salaries and bonuses one hundred times the pay of ordinary workers.

FIG. 12.1. Income inequality in Russia, 1900–2015

Interpretation: The top decile share of total national income averaged 25 percent in Soviet Russia, lower than in Western Europe or the United States, before rising to 45–50 percent after the fall of communism, surpassing both Europe and the United States. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

FIG. 12.2. The top centile in Russia, 1900–2015

Interpretation: The top centile share of total national income averaged 5 percent in Soviet Russia, lower than in Western Europe or the United States, before rising to 20–25 percent after the fall of communism, surpassing both Europe and the United States. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

However, this should not obscure the fact that the regime organized its inequalities in other ways by offering in-kind benefits and privileged access to certain goods to its officials. These are difficult to take fully into account. There were also stark status differences: the mass incarceration of whole classes of people is only the most extreme instance of this; there was also a sophisticated internal passport system, which restricted the mobility of some, including the ability of peasants, who suffered greatly from the collectivization of agriculture and the forced march toward industrialization, to migrate to the cities. Suspect or condemned groups were confined to certain areas, and workers were prevented from moving if planners felt that they were needed in certain places or that there was insufficient housing to accommodate them elsewhere.8 It would be misleading to try to integrate all these aspects of Soviet inequality into a single quantitative index based on monetary income. In my view, it is best to indicate what is known about monetary inequality while insisting on the fact that this was only one dimension of Soviet inequality (and not necessarily the most significant one); the same is true of other inequality regimes.

FIG. 12.3. The income gap between Russia and Europe, 1870–2015

Interpretation: Expressed in terms of purchasing power parity, the national income per adult in Russia was 35–40 percent of the Western European average (Germany, France, and the United Kingdom) from 1870 to 1980, before rising from 1920 to 1950, then stabilizing at about 60 percent of the Western European level from 1950 to 1990. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

As for the evolution of the standard of living under Soviet rule, once again the evidence is incomplete. According to the best available estimates, the standard of living, as measured by per capita national income, stagnated in Russia in the period 1870–1910 at around 35–40 percent of the West European level (defined as the average of the United Kingdom, France, and Germany); it then rose gradually in the period 1920–1950 to about 60 percent of the West European level (Fig. 12.3). Although these comparisons should not be viewed as perfectly precise, the orders of magnitude may be taken as significant. There is no doubt that Russia began to catch up with Western Europe between the Revolution of 1917 and the 1950s. Some of this was of course due to the fact that Russia started out so far behind. Its progress was made more visible by the poor performance of the capitalist countries in the 1930s, when production collapsed in Western Europe and the United States, while the planned Soviet economy continued full speed ahead. For both structural and conjunctural reasons, then, it was possible in the 1950s to see the Soviet Union’s results as globally positive.

Over the next four decades (1950–1990), however, Russian national income stagnated at about 60 percent of the West European level (Fig. 12.3). This was clearly a failure, especially in view of the rapid advance in level of education during this period in Russia (as well as elsewhere in Eastern Europe), which should normally have led to continuation of the catch-up process and gradual convergence with Western Europe. The fault must therefore lie with the organization of the system of production. The frustration was even greater because the scientific, technological, and industrial achievements of the communist regimes were abundantly praised in the 1950s and 1960s both inside and outside the communist bloc. In the eighth edition (1970) of Paul Samuelson’s celebrated economics textbook, used by generations of North American students, it was predicted on the basis of observed trends in the period 1920–1970 that Soviet gross domestic product (GDP) might surpass that of the United States sometime between 1990 and 2000.9 During the 1970s, however, it became increasingly clear that the catch-up process had ground to a halt and that the Russian standard of living had stagnated compared to that of the capitalist countries.

It is also possible, moreover, that these comparisons underestimate the actual gap in standard of living between East and West, particularly at the end of the period. Indeed, if the poor quality of consumer goods (such as household appliances and cars) available in the communist countries is taken into account in the price indices used in these comparisons, it is quite possible that the gap grew even wider in the 1960s and afterward. Another complication stems from the bloated Soviet military sector, which represented as much as 20 percent of GDP during the Cold War, compared with 5–7 percent in the United States.10 To be sure, the concentration of material investments and intellectual resources in strategic sectors did lead to spectacular successes, such as the launching of the first Sputnik satellite in 1957, to the consternation of the United States. But none of that can mask the mediocrity of living conditions for ordinary citizens and the increasingly glaring backwardness relative to the capitalist countries in the 1970s and 1980s.

The Highs and Lows of Communist and Anticolonialist Emancipation

In view of the significant differences between Eastern and Western methods of tallying production and accounting for income as well as the multidimensional character of the gaps, the best way to measure how bad conditions in Soviet Russia were is probably to use demographic data. The numbers show a worrisome stagnation of life expectancy from the 1950s on. Indeed, in the late 1960s and early 1970s we even find a slight decrease in life expectancy for men, which is unusual in peacetime; in addition, infant mortality rates stopped decreasing.11 These figures point to a health system in crisis. In the 1980s, the efforts of Mikhail Gorbachev, the last president of the Soviet Union, to reduce alcohol abuse played an important role in the decline of his popularity and the ultimate collapse of the regime. Soviet Communism, once celebrated for rescuing the Russian people from Tsarist misery, had become synonymous with rampant poverty and shortened lives.

On the political-ideological level, the Soviet Union suffered in the 1970s from loss of the prestige it had enjoyed in the postwar era. In the 1950s the Soviet Union’s international reputation was enhanced by the decisive role it had played in the victory over Nazism and by the fact that, through the Communist International which it controlled, it was the only political and ideological force that stood in clear and radical opposition to colonialism and racism. In the 1950s, racial segregation was still widely practiced in the southern United States. It was not until 1963–1965 that American blacks mobilized to force the Democratic administrations of John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson (who had no desire to send troops into the South to defend blacks) to grant civil and voting rights to African Americans. South Africa introduced and then reinforced apartheid in the 1940s and early 1950s with a series of laws intended to confine blacks to the townships and preventing them from setting foot in other parts of the country (Chapter 7). The South African regime, close to Nazism in its racialist inspiration, was supported by the United States in the name of anticommunism. It was not until the 1980s that international sanctions were imposed on South Africa, despite opposition from the Reagan administration in the United States, which continued until 1986 (when Reagan used his veto to try to thwart Congressional disapproval of apartheid but was overridden).12

In the 1950s, the decolonization movement had just begun, and France was on the verge of waging a fierce war in Algeria. While the Socialists participated in the government and supported increasingly violent operations to “maintain order” in Algeria, only the Communist Party spoke out unambiguously in favor of immediate independence and withdrawal of French troops. At that key point in time, the communist movement seemed to many intellectuals and to the international proletariat to be the only political force in favor of organizing the world on an egalitarian social and economic basis, while colonialist ideology continued to prefer an inegalitarian, hierarchic, racialist logic.

In 1966, a newly independent Senegal organized in Dakar a “World Festival of Negro Arts.” This was an important event for the pan-African movement and the idea of “negritude,” a literary and political concept elaborated by Léopold Senghor in the 1930s and 1940s. Senghor, a writer and intellectual, became the first president of Senegal in 1960 after trying in vain to form a broad West African federation.13 All the major powers, capitalist as well as communist, responded to the invitation and sought to make a good impression. At the Soviet stand, a delegation from Moscow displayed a brochure setting forth its convictions and political analyses. Russia, unlike the United States and France, did not need slavery to industrialize, this document argued. It was therefore in a better position to forge development partnerships with Africa on an egalitarian basis.14 This claim apparently surprised no one because it seemed so natural at the time.

By the 1970s, this Soviet moral prestige had almost totally dissipated. The era of decolonization was over, black Americans had obtained their civil rights, and antiracism and racial equality were among the values to which the capitalist countries laid claim now that they had become postcolonial and social-democratic. Of course, racial issues and the question of immigration would soon play a growing role in European and American political conflict in the 1980s and 1990s. I will say much more about this in Part Four. But the fact remains that by the 1970s the communist camp had lost its clear moral advantage on these issues, and critics of communism could now focus on its repressive and carceral policies, its treatment of dissidents, and its poor social and economic performance. In the television series The Americans, Elizabeth and Philip are KGB (the USSR’s Committee for State Security) agents operating in the United States in the early 1980s. Elizabeth has an affair with a black American activist, which shows that she remains more sincerely attached to the communist ideal than Philip, the Soviet agent posing as her husband, who wonders why he is doing what he is doing as the end of the Soviet regime draws near. Broadcast between 2013 and 2018, this series shows how much things had changed since the days when Soviet Communist was widely regarded as a champion of antiracism and anticolonialism.15

A similar though less dramatic shift occurred with feminism. In the period 1950–1980, when the patriarchal ideology of the housewife reigned supreme in the capitalist countries, communist regimes took the lead in advocating equality between men and women, particularly in the workplace. Support was offered in the form of public day care and preschools as well as contraception and family planning. This positioning was not free of hypocrisy, to judge by the fact that political leadership in the communist countries was as male-dominated as anywhere else.16 Still, soviets and other parliamentary assemblies in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe were up to 30–40 percent female in the 1960s and 1970s, at which time women made up less than 5 percent of parliaments in Western Europe and the United States. Of course, assemblies in the communist countries had limited political autonomy and were often chosen by elections in which there was only one candidate or perhaps a token opposition candidate, with the Communist Party holding nearly all the real power. The inclusion of female candidates therefore had only limited consequences for the reality of power and its distribution.

In any case, the proportion of female representatives abruptly fell from 30–40 percent to little more than 10 percent in Russian and Eastern Europe in the 1980s and 1990s, roughly the same level as in the West or even slightly below.17 By the way, it is worth noting that China and several other countries in South and Southeast Asia were well ahead of the West in regard to the proportion of female representatives in the 1960s and 1970s. In Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s novel Half of a Yellow Sun, which is set in Nigeria in the early 1960s on the eve of the Nigerian civil war, the intellectual Igbo Odenigbo is passionate about his newly independent country’s politics. He follows the news as a citizen of the world, from the struggle for racial equality in Mississippi to the Cuban revolution, to say nothing of the election of the first female prime minister in Ceylon. In the 1990s the Western countries would take up the feminist cause, like so many others before it, with varying degrees of sincerity and effectiveness when it came to achieving actual equality between the sexes (I will come back to this).

Communism and the Question of Legitimate Differences

To return to the Soviet attitude toward poverty, it is important to try to understand why the government took such a radical stance against all forms of private ownership of the means of production, no matter how small. Criminalizing carters and food peddlers to the point of incarcerating them may seem absurd, but there was a certain logic to the policy. Most important was the fear of not knowing where to stop. If one began by authorizing private ownership of small businesses, would one be able to set limits? And if not, would this not lead step by step to a revival of capitalism? Just as the proprietarian ideology of the nineteenth century rejected any attempt to challenge existing property rights for fear of opening Pandora’s box, twentieth-century Soviet ideology refused to allow anything but strict state ownership lest private property find its way into some small crevice and end up infecting the whole system.18 Ultimately, every ideology is the victim of some form of sacralization—of private property in one case, of state property in another; and fear of the void always looms large.

With the advantage of hindsight and knowledge of the twentieth century’s successes and failures, it is possible to outline new ideas—such as participatory socialism and temporary shared ownership—with which it might be possible to go beyond both capitalism and the Soviet form of communism. Specifically, one can imagine a society that allows privately owned firms of reasonable size while preventing excessive concentration of wealth by means of a progressive wealth tax, a universal capital endowment, and power sharing between stockholders and employees. Historical experience can teach us to set limits and map boundaries. Of course, history cannot tell us with mathematical certainty what the perfect policies are in every situation. Instead, the lessons we draw must be subject to permanent deliberation and experimentation. Still, history can teach us where to begin in order to move ahead. For example, we now know that the top centile’s share of total wealth can fall from 70 to 20 percent without impeding growth (quite the contrary, as Western European experience in the twentieth century shows). We know from experience with Germanic and Nordic versions of co-management that employee and shareholder representatives can each control half the voting rights in a firm and that such power sharing can improve overall economic performance.19 The path from these concrete experiences to a fully satisfactory form of participatory socialism is complex, especially since it is hard to draw the line between small production units and large ones. Indeed, it is indispensable to conceptualize the entire system and to think about how firms of different sizes, from the smallest to the largest, might be flexibly regulated and taxed.20 Nevertheless, history is sufficiently rich in lessons that we can draw from it many ideas about possible paths forward.21

Why did Bolshevik leaders reject the path of decentralized participatory socialism in the 1920s? It was not just because they lacked the experimental knowledge gained over the course of the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, concerning most notably the successes and limitations of social democracy. Nor was it solely because they worried about the complexities mentioned earlier. To have a clear idea of the virtues of decentralization, one also has to articulate a clear vision of human equality—a vision that fully recognizes the many legitimate differences among individuals, especially with respect to knowledge and aspirations, and the importance of these differences in determining how social and economic resources are deployed. Soviet Communism tended to neglect the importance and especially the legitimacy of such differences, probably because it was in the grip of an industrial and productivist illusion. Specifically, if one believes that human needs are few in number and relatively simple (for, say, food, clothing, housing, education, and medical care) and can be satisfied by providing virtually identical goods and services to everyone (partly on the reasonable ground that all human beings share fundamentally the same hopes), then decentralization may seem unimportant. A centrally planned society and economy should be able to do the job, allocating every material and human resource as needed.

In fact, however, the problem of social and economic organization is more complex. It cannot be reduced to satisfying a basic set of simple, homogeneous needs. In all societies—whether in Moscow in 1920 or Paris or Abuja in 2020—individuals “need” an infinite variety of goods and services to lead their lives and fulfill their hopes and aspirations. Of course, some of these “needs” are artificial or exploitative or harmful or polluting and therefore inimical to the basic needs of others, in which case their expression must be limited through collective deliberation, laws, and institutions. But much of this diversity of human needs is legitimate, and if the central government attempts to suppress it, the government risks becoming oppressive to both individuality and individuals. In 1920s Moscow, for example, some people preferred, because of their personal history or social habits, to live in certain neighborhoods or eat certain foods or wear certain clothes. Others had come to own a cart or food stand or to possess certain specific skills. The only way such legitimate differences could be expressed and made to interact with one another would have been through decentralized organization. A centralized state could not do the job, not only because no state could ever gather enough relevant information about every individual but also because the mere attempt to do so would negatively affect the social process through which individuals come to know themselves.

On the Role of Private Property in a Decentralized Social Organization

Workers’ cooperatives were often discussed in debates around the NEP in 1920s Russia as well as in the 1980s in connection with Gorbachev’s perestroika (economic restructuring). Yet even cooperatives cannot respond fully to the challenges posed by the diversity of human needs and aspirations. Recall our discussion in Chapter 11 of the individual who wanted to open a restaurant or an organic grocery store. We saw there that it would not have made much sense to accord the same decision-making power to the person who had invested all her savings and energy in getting such a project off the ground as to the person hired as an employee the day before, who might be dreaming of starting his own business, in which it would make just as little sense to take away his primary role. Such individual differences with respect to both projects and aspirations are legitimate, and they will continue to exist even in a perfectly egalitarian society in which each person starts out with strictly the same economic and educational capital. In that case they would simply reflect the diversity of human aspirations, subjectivities, and personalities and the range of possible individual histories. Indeed, private ownership of the means of production, correctly regulated and limited, is an essential part of the decentralized institutional organization necessary to allow these various individual aspirations and characteristics to find expression and in due course come to fruition.

Of course, the resulting concentration of private property and the power that flows from it will need to be rigorously debated and controlled and should not exceed what is strictly necessary; this could be accomplished through devices such as a steeply progressive wealth tax, a universal capital endowment, and fair power sharing between a firm’s employees and shareholders. As long as private property is viewed in such purely instrumental terms, without sacralization of any kind, it is indispensable, provided that one agrees that the ideal socioeconomic organization must respect the diversity of aspirations, knowledge, talent, and skills that constitutes the wealth of humankind. By contrast, criminalizing every form of private property, down to the carter’s cart and the food vendor’s stand, as the Soviet authorities tried to do in the 1920s, comes down to assuming that this diversity of aspirations and subjectivities is of limited value when it comes to organizing production and building an industrial economy.

Finally, one additional element of complexity is worth pointing out. In practice, legitimate differences of aspiration have often been used rhetorically to justify quite dubious inequalities. For instance, parental preferences for different types of schools and curricula are often cited as justifications for inequality between schools and for disadvantaging children whose parents are less skilled at deciphering the codes and choosing the most promising schools and courses. A reasonable solution to this problem might be to banish market competition from the sphere of education and supply adequate and equal funding to all schools, which is what most countries have in fact done, at least at the primary and secondary level.22 In general, the rules appropriate to each sector should be decided by collective democratic deliberation. When a good or service is reasonably homogeneous—for instance, when a given community can agree on the knowledge and skills that every child of a certain age ought to have—then there is little need for competition among the units producing that good or service (much less for private profit-generating ownership of the means of production); indeed, competition may well prove harmful in such circumstances. By contrast, in sectors where there is a legitimate diversity of individual aspirations and preferences—for instance, in the supply of clothing or food—then decentralization, competition, and regulated private ownership of the means of production are justified.

This reflection on the extent of legitimate differences is of course complex. It is too simple to say that private ownership is the solution to every problem or, conversely, that it should be criminalized in all circumstances. The question must be dealt with, however, if the goal is to rethink property as temporarily private but ultimately social in the framework of a global strategy of emancipation designed not to reproduce the fatal errors of Soviet Communism.

Postcommunist Russia: An Oligarchic and Kleptocratic Turn

In contrast to the Soviet Union, a “society of petty thieves,” postcommunist Russia is a society of oligarchs engaged in grand larceny of public assets. Let us begin with a glance back at recent history. The dismantling of the Soviet Union and its productive apparatus in 1990–1991 led directly to a sharp decline in the standard of living in 1992–1995. In the late 1990s per capita income began to climb until in the 2010s it stood at about 70 percent of the West European level in terms of purchasing power parity (Fig. 12.3) but at half that level using current exchange rates (owing to the weakness of the ruble). On the whole, although the situation has improved since the end of communism, the results have been mediocre, especially since inequality increased dramatically in the 1990s (Figs. 12.1–12.2).

It is important to note that it is very difficult to measure and analyze income and wealth in postcommunist Russia because the society is so opaque. This is due in large part to decisions taken first by the governments headed by Boris Yeltsin and later by Vladimir Putin to permit unprecedented evasion of Russian law through the use of offshore entities and tax havens. In addition, the postcommunist regime abandoned not only any ambition to redistribute property but also any effort to record income or wealth. For example, there is no inheritance tax in postcommunist Russia, so there are no data on the size of inheritances. There is an income tax, but it is strictly proportional, and its rate since 2001 has been just 13 percent, whether the income being taxed is 1,000 rubles or 100 billion rubles.

Note, by the way, that no other country has gone as far as Russia in rejecting the very idea of a progressive tax. In the United States, the Reagan and Trump administrations did make reduction of top marginal tax rates a central plank in their platforms in the hope of stimulating economic activity and entrepreneurial spirits, but they never went so far as to reject the principle of progressive taxation itself: tax rates on the lowest income brackets remain lower in the United States than rates on the highest brackets, which Republican administrations reduced to 30–35 percent when they had the chance, but not to 13 percent.23 A flat tax of 13 percent would trigger vigorous opposition in the United States, and it is hard to imagine an electoral or ideological majority willing to approve such a policy (at least for the foreseeable future). The fact that Russia did opt for such a tax policy shows that postcommunism is in a sense the ultimate form of the inegalitarian ultra-liberalism of the 1980s and 1990s.

Note, too, that there were no progressive income or inheritance taxes in the communist countries (or, if there were, their role was minor), because central planning and state control of firms allowed the state to set wages and incomes directly. When planning was abandoned and firms were privatized, however, progressive taxation could have played a role similar to the role it played in the capitalist countries in the twentieth century. The fact that this did not happen demonstrates once again how little countries share experiences and learn from one another.

As usual, the lack of a political commitment to progressive taxation coincided in Russia with a particularly opaque fiscal administration. The available tax data are extremely limited and rudimentary. With Filip Novokmet and Gabriel Zucman, however, we were able to access certain sources, which allowed us to show that official estimates, which are based on self-declared survey data and ignore top incomes almost entirely, seriously underestimate the increase of income inequality since the fall of communism. Concretely, the data show that the top decile’s share of total income, which was just over 25 percent in 1990, rose to 45–50 percent in 2000 and then stabilized at that very high level (Fig. 12.1). Even more dramatic was the increase in the top centile’s share from barely 5 percent in 1990 to about 25 percent in 2000, a level significantly higher than the United States (Fig. 12.2). Peak inequality was probably achieved in 2007–2008. The highest Russian incomes have probably declined since the crisis of 2008 and the imposition of economic sanctions on Russia after the Ukraine crisis of 2013–2014, although the level remains extremely high (and is no doubt underestimated owing to the limitations of the available data). Thus, in less than ten years, from 1990 to 2000, postcommunist Russia went from being a country that had reduced monetary inequality to one of the lowest levels ever observed to being one of the most inegalitarian countries in the world.

The rapidity of postcommunist Russia’s transition from equality to inequality between 1990 and 2000—a transition without precedent anywhere else in the world according to the historical data in the WID.world database—attests to the uniqueness of Russia’s strategy for managing the transition from communism to capitalism. Whereas other communist countries such as China privatized in stages and preserved important elements of state control and a mixed economy (a gradualist strategy that one also finds in one form or another in Eastern Europe), Russia chose to inflict on itself the famous “shock therapy,” whose goal was to privatize nearly all public assets within a few years’ time by means of a “voucher” system (1991–1995). The idea was that Russian citizens would be given vouchers entitling them to become shareholders in a firm of their choosing. In practice, in a context of hyperinflation (prices rose by more than 2,500 percent in 1992) that left many workers and retirees with very low real incomes and forced thousands of the elderly and unemployed to sell their personal effects on the streets of Moscow while the government offered large blocks of stock on generous terms to selected individuals, what had to happen did happen. Many Russian firms, especially in the energy sector, soon fell into the hands of small groups of cunning shareholders who contrived to gain control of the vouchers of millions of Russians; within a short period of time these people became the country’s new “oligarchs.”

According to the classifications published by Forbes, Russia thus became within a few years the world leader in billionaires of all categories. In 1990, Russia quite logically had no billionaires, because all property was publicly owned. By the 2000s, the total wealth of Russian billionaires listed in Forbes amounted to 30–40 percent of the country’s national income, three or four times the level observed in the United States, Germany, France, and China.24 Also according to Forbes, the vast majority of these billionaires live in Russia, and they have done particularly well since Vladimir Putin came to power in the early 2000s. Note, moreover, that these figures do not include all the Russians who have accumulated not billions but merely tens or hundreds of millions of dollars; these Russians are far more numerous and more significant in macroeconomic terms.

In fact, what has distinguished Russia in the period 2000–2020 is that the country’s wealth is largely in the hands of a small group of very wealthy individuals who either reside entirely in Russia or divide their time between Russia and London, Monaco, Paris, or Switzerland. Their wealth is for the most part hidden in screen corporations, trusts, and the like, ostensibly located in tax havens so as to escape any future changes in Russia legal and tax systems (although Russian authorities have not shown themselves to be particularly vigilant). The use of screens, cutouts, and other legal subterfuges to place assets outside the legal jurisdiction of a given country while affording solid guarantees to the owners and while the actual economic activity of the firm takes place inside the country is a general characteristic of the economic, financial, and legal globalization that has taken place since the 1980s.25 This has occurred because the international treaties and accords that Europe and the United States agreed on to liberalize capital flows in this period did not include any regulatory mechanisms or provisions for exchanges of information that would have allowed states to establish appropriate fiscal, social, and legal policies and cooperative structures for coping with this new environment (see Chapter 11). Responsibility for this state of affairs is therefore broadly shared. But even within this general landscape, Russian abuse of the system has attained unheard-of proportions, as recent work by legal scholars has shown.26

When Offshore Assets Exceed Total Lawful Financial Assets

Note, too, that in terms of macroeconomic significance of capital flight, Russia is also in a league of its own. Because of the very nature of financial dissimulation, it is of course difficult to give a precise accounting. In Russia, however, the very magnitude of the sums involved simplifies things somewhat, as does the fact that the country enjoyed enormous trade surpluses in the period 1993–2018: Russia’s annual trade surplus averaged 10 percent of GDP over this twenty-five-year period, or a total of nearly 250 percent of GDP (2.5 years of national product). In other words, since the early 1990s, Russian exports, especially gas and oil, massively exceeded Russian imports of goods and services. In principle, then, the country should have accumulated enormous financial reserves of roughly the same amount. This is what we see in other petroleum-exporting countries such as Norway, whose sovereign wealth fund held assets in excess of 250 percent of GDP in the mid-2010s. But Russia’s official reserves in 2018 amounted to less than 30 percent of GDP. Something like 200 percent of Russian GDP has therefore gone missing (and this does not even take into account the income those assets should have produced).

Official Russian balance-of-payments statistics reveal other astonishing features. Public and private assets invested abroad seem to have obtained remarkably mediocre yields, with large capital losses in some years, whereas foreign investments in Russia invariably earned exceptional yields, especially in view of fluctuations in the value of the ruble, which would partly explain why the country’s net wealth position vis-à-vis the rest of the world did not increase more. It is quite possible that these statistics hide operations linked to capital flight. In any case, even if we accept these yield differentials as legitimate, the fact remains that the official reserves in the balance-of-payments data are still much too low. Using these very conservative assumptions, one can estimate that cumulative capital flight from 1990 to the mid-2010s amounts to roughly one year of Russian national income (Fig. 12.4). To be clear, this is a minimum estimate; the actual figure might be twice as high or even higher.27 In any event, this minimum estimate implies that the financial assets tucked away in tax havens are roughly equal to the total amount of all financial assets legally owned by Russian households inside Russia (roughly one year of national income). In other words, offshore property has become at least as important in macroeconomic terms as legal financial property—and probably is more important. In a sense, then, illegality has become the norm.

FIG. 12.4. Capital flight from Russia to tax havens

Interpretation: By examining the growing gap between cumulative Russian trade surpluses (nearly 10 percent a year on average from 1993 to 2015) and official reserves (barely 30 percent of national income in 2015), and using various hypotheses about yields obtained, one can estimate that the amount of Russian assets held in tax havens was between 70 and 110 percent of national income in 2015, with an average value of around 90 percent. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

There are also other sources that reveal (or confirm) the magnitude of Russian capital flight and, more generally, the unprecedented growth of tax havens around the world since the 1980s. For instance, one can look at inconsistencies in international financial statistics. In theory, looking at a country’s balance of payments should allow us to measure financial flows and in particular inward and outward flows of capital income (dividends, interest, and profits of all kinds). In principle, the total of all positive and negative flows should sum to zero every year at the international level. Of course, the complexity of the accounting may result in small discrepancies, but these should be both positive and negative and even out over time. Since the 1980s, however, there has been a systematic tendency for outward capital income flows to exceed inward flows. From these and other anomalies it is possible to estimate that in the early 2010s, financial assets held in tax havens and not registered in other countries amounted to nearly 10 percent of total global financial assets. All signs are that this has only increased since then.28

Furthermore, by exploiting data made public by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) and the Swiss National Bank (SNB) on countries where assets are held, one can estimate each country’s approximate share of offshore assets held in tax havens relative to the total (lawful and unlawful) assets held by residents of each country. The results are as follows: “only” 4 percent for the United States, 10 percent for Europe, 22 percent for Latin America, 30 percent for Africa, 50 percent for Russia, and 57 percent for the petroleum monarchies (Fig. 12.5). Once again, these should be regarded as minimum estimates. These calculations exclude (or only partially account for) real estate and shares in unlisted companies.29 Note, by the way, that financial opacity is a problem everywhere, particularly in the less developed countries, for which it is an obstacle to state building and to finding a standard of fiscal justice acceptable to a majority of citizens.

The Origins of “Shock Therapy” and Russian Kleptocracy

Why did postcommunist Russia go from the land of soviets and (monetary) income equality to the land of oligarchs and kleptocrats? It is tempting to see this as a “natural” swing of the pendulum: traumatized by the Soviet failure, the country moved energetically in the opposite direction, that of ruthless capitalism. This explanation cannot be totally wrong, but it leaves out a lot and is too deterministic. There was nothing “natural” about Russia’s postcommunist transformation, any more than the transformation of any other inequality regime. There were many choices available in 1990, as there always are. Rather than rehearse the various deterministic accounts, it is more interesting to see what happened as the fruit of contradictory and conflictual socioeconomic and political-ideological processes, which could have taken any number of paths and turned out differently had the balance of power and capacity for mobilization of the various contending groups been different.

FIG. 12.5. Financial assets held in tax havens

Interpretation: By exploiting anomalies in international financial statistics and breakdowns by country of residence from the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) and the Swiss National Bank (SNB), one can estimate that the share of financial assets held in tax havens is 4 percent for the United States, 10 percent for Europe, and 50 percent for Russia. These figures exclude nonfinancial assets (such as real estate) and financial assets unreported to BIS and SNB, and should be considered minimum estimates. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

In the early 1990s, with Russia in a state of extreme weakness, there was brief but intense struggles about the choice of “shock therapy” for the post-Soviet transition. Among the proponents of shock therapy were many representatives of Western governments (especially the United States) and international organizations based in Washington, such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. The general idea was that only an ultra-rapid privatization of the Russian could ensure that the changes would be irreversible and prevent any possibility of a return to communism. It is no exaggeration to say that the dominant ideology among economists working for these institutions in the early 1990s was much closer to Anglo-American capitalism in the Reagan-Thatcher mold than to European social democracy or Germano-Nordic co-management. Most Western advisers working in Moscow at the time were convinced that the Soviet Union had sinned by an excess of egalitarianism; hence, any possible increase of inequality in the wake of privatization and shock therapy should be considered a relatively minor worry.30

With the advantage of hindsight, however, we can see that the levels of (monetary) inequality observed in Soviet Russia in the 1980s were not very different from those observed at the same time in the Nordic countries, especially Sweden: in both cases the top decile claimed about 25 percent of total income and the top centile 5 percent, which never prevented Sweden from ranking among the countries with the highest standard of living and highest productivity levels in the world (see Figs. 10.2–10.3). Thus, the problem was not so much excessive equality as the way the economy and production were organized, which involved central planning and total abolition of private ownership of the means of production. It is reasonable to think that if Russia had adopted Nordic-style social-democratic institutions with a highly progressive tax system, an advanced system of social protection, and co-management by unions and shareholders, it would have been possible to preserve a certain level of equality while raising the level of productivity and standard of living. The choice that Russia made in the 1990s was very different: a small group of people (the future oligarchs) was offered the opportunity to take possession of most of the country’s wealth with a flat income tax of 13 percent (and no inheritance tax), which allowed them to entrench their position; contrast this with the adoption by most Western countries of progressive income and inheritance taxes in the twentieth century. It is sometimes shocking to discover the degree to which historical memory is lacking and just how little countries are able to share and learn from each other’s experiences. It is especially shocking when the people and institutions responsible for these failures are supposed to be the very ones whose presumed purpose is to further international cooperation through shared knowledge and expertise.

It would be a mistake, however, to attribute Russia’s political-ideological choices solely to outside influences. Internal disagreements also mattered. In the late 1980s, Mikhail Gorbachev tried without success to promote an economic model that would preserve the values of socialism while encouraging contributions from cooperatives and regulated (though ill-defined) forms of private ownership. Other groups inside the Russian government, particularly within the security apparatus, did not share Gorbachev’s views. In this respect, Vladimir Putin’s analyses in interviews conducted by (the very pro-Putin) filmmaker Oliver Stone in 2017 are particularly revealing. Putin mocks Gorbachev’s egalitarian illusions and his obsession with saving socialism in the 1980s, especially his liking for “French Socialists” (an approximate but significant reference, since French Socialists at the time represented what was most socialist in the Western political landscape). In substance, Putin concluded that only an unambiguous renunciation of egalitarianism and socialism in all their forms could restore Russia’s greatness, which depended above all on hierarchy and verticality in both politics and economics.

It is important to stress the fact that this trajectory was not foreordained. The post-Soviet economic transition took place in particularly chaotic circumstances, with no real electoral or democratic legitimacy. When Boris Yeltsin was elected president of the Russian Federation by universal suffrage in June 1991, no one knew exactly what his powers would be. The pace of events accelerated after the failed Communist putsch of August 1991, which led to the accelerated dismantling of the Soviet Union in December. Economic reforms then proceeded at full throttle, with the liberalization of prices in January 1992 and “voucher privatization” in early 1993. All this took place without new elections so that key decisions were imposed by the executive on a hostile parliament, which had been elected in March 1990 during the Soviet era (when only a handful of non-Communist candidates were allowed to run). This was followed by a violent clash between the president and parliament, which was settled by force in the fall of 1993 when the parliament was shelled and then dissolved. With the exception of the presidential election of 1996, which Yeltsin won with just 54 percent of the vote in the second round against a Communist candidate, no genuinely contested election has taken place in Russia since the fall of the Soviet Union. Since Putin came to power in 1999, the arrest of political opponents and clamp down on the media have left Russia under de facto authoritarian and plebiscitarian rule. The fundamentally oligarchic and inegalitarian orientation of policy since the fall of communism has never really been debated or challenged.

To sum up, Soviet and post-Soviet experience demonstrates in a dramatic way the importance of political-ideological dynamics in the evolution of inequality regimes. The Bolshevik ideology that dominated after the revolution of 1917 was relatively crude, in the sense that it was based on an extreme form of hypercentralized state rule. Its failures led to steadily increasing repression and a historically unprecedented rate of incarceration. Then the fall of the Soviet regime in 1991 led to an extreme form of hypercapitalism and an equally unprecedented kleptocratic turn. These episodes also demonstrate the importance of crises in the history of inequality regimes. Depending on what ideas are available when a switch point arrives, a regime’s direction may turn one way or another in response to the mobilizing capacities of the various groups and discourses in contention. In the Russian case, the country’s postcommunist trajectory reflects in part the failure of social democracy and participatory socialism to develop new ideas and a workable plan for international cooperation in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when the hypercapitalist and authoritarian-identitarian conservative agendas were in their ascendancy.

If we now look to the future, it is legitimate to ask why the countries of Western Europe have been so uninterested in the origins of Russian wealth and so tolerant of such massive misappropriations of capital. One possible explanation is that they were partly responsible for the shock therapy approach to the transition and benefited from infusions of capital invested by wealthy Russians in West European real estate, financial firms, sports teams, and media. This is obviously true not only of the United Kingdom but also of France and Germany. There is also the fear of a violent response by the Russian government.31 Still, instead of imposing trade sanctions, which affect the entire country, a better solution would be to freeze or severely penalize financial and real estate assets of dubious origin.32 One might then be able to influence Russian public opinion, since the Russian people themselves were the first victims of the kleptocratic turn. If European governments have not been more proactive, it is no doubt because they worry about not knowing where it will end if they begin to question past appropriations of common resources by private individuals (this is the Pandora’s box syndrome that we have encountered several times before).33 Nevertheless, Europe might be better equipped to solve many of the other problems it faces if it were to engage more energetically in the fight against financial opacity by insisting on the creation of a true international register of financial assets.

On China as an Authoritarian Mixed Economy

We turn now to communism and postcommunism in China. It is well known that China drew lessons from the USSR’s failures as well as from its own mistakes in the Maoist era (1949–1976), during which the attempt to completely abolish private property and to initiate a forced march toward collectivization and industrialization ended in disaster. In 1978 the country began experimenting with a novel type of political and economic regime, which rests on two pillars: a leading role for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which has been maintained and even reinforced in recent years, and the development of a mixed economy based on a novel balance between private and public property, which has proved to be durable.

We begin with the second pillar, which is essential for understanding the specificities of the Chinese case. Another advantage of this choice is that the contrast with Western experience is illuminating. The best way to proceed is to pull together data from all available sources concerning the ownership of firms, farmland, residential real estate, and financial assets and liabilities of all kinds in order to estimate the share of property owned by the government (at all levels). The results are shown in Fig. 12.6, which compares China’s evolution with that of the leading capitalist countries (United States, Japan, Germany, United Kingdom, and France).34

FIG. 12.6. The fall of public property, 1978–2018

Interpretation: The share of public capital (public assets net of debt including all public assets: firms, buildings, land, investments, and financial assets) in national capital (total public and private) was roughly 70 percent in China in 1978; it then stabilized at around 30 percent in the mid-2000s. It was 15–30 percent in the capitalist countries in the 1970s and is near zero or negative in the late 2010s. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

The main conclusion is that the public share of capital was close to 70 percent in China in 1978, when economic reforms were inaugurated, but then fell sharply in the 1980s and 1990s before stabilizing at around 30 percent since the mid-2000s. In other words, the gradual privatization of Chinese property ended in 2005–2006: the relative shares of public and private property have barely moved since then. Because the Chinese economy has continued to grow at a rapid rate, private capital has obviously continued to increase: new land has been improved and new factories and apartment buildings have continued to be built at a breakneck pace, but publicly owned capital has also continued to increase at roughly the same rate as privately owned capital. China thus appears to have settled on a mixed-economy property structure: the country is no longer communist since nearly 70 percent of all property is now private, but it is not completely capitalist either because public property still accounts for a little more than 30 percent of the total—a minority share but still substantial. Because the Chinese government, led by the CCP, owns a third of all there is to own in the country, its scope for economic intervention is large: it can decide where to invest, create jobs, and launch regional development programs.

It is important to note that the 30 percent public share of capital is an average that hides very large difference between sectors and asset categories. For instance, residential real estate is almost entirely privatized. In the late 2010s, the government and firms owned less than 5 percent of the housing stock, which has become the leading private investment of Chinese households with sufficient means. This has caused the price of real estate to skyrocket, especially since other savings opportunities are limited and the public retirement system is underfunded and shaky. By contrast, the government held 55–60 percent of the total capital of firms in 2010 (including both listed and unlisted firms of all sizes in all sectors). This share has remained virtually unchanged since 2005–2006. In other words, the state and party continue to maintain tight control over the productive system—indeed, tighter than ever with respect to the largest firms.35 Since the mid-2000s there has been a significant decrease in the share of firm capital held by foreign investors, which has been offset by an increase in the share held by Chinese households (Fig. 12.7).36

From the 1950s to the 1970s, the capitalist countries were also mixed economies, with important variations from country to country. Public assets took many forms, including infrastructure, public buildings, schools, and hospitals; in addition, many firms were publicly owned, and there was public financial participation in certain sectors. Furthermore, public debt was historically low owing to postwar inflation and government measures to reduce debt, such as exceptional taxes on private capital or even outright debt cancellation (see Chapter 10). All told, the share of public capital (net of debt) in national capital was generally 20–30 percent in the capitalist countries in the period 1950–1980.37 In the late 1970s, available estimates show a level of 25–30 percent in Germany and the United Kingdom and 15–20 percent in France, the United States, and Japan (Fig. 12.6). To be sure, these levels are lower than the share of public capital in China today but not by much.

FIG. 12.7. Ownership of Chinese firms, 1978–2018

Interpretation: The Chinese state (at all levels of government) in 2017 held roughly 55 percent of the capital of Chinese firms (both listed and unlisted, of all sizes in all sectors), compared with 33 percent for Chinese households and 12 percent for foreign investors. The share of the latter has decreased since 2006 and that of Chinese households has increased, while the share of the Chinese state has stabilized at around 55 percent. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

The difference is that the Western countries have long since ceased to be mixed economies. Owing to privatization of public assets (for instance, in the utilities and telecommunications sector), limited investment in sectors that have remained public (especially education and health), and the steady increase of public indebtedness, the share of net public capital in national capital has shrunk to virtually zero (less than 5 percent) in all the major capitalist countries; in the United States and United Kingdom, it is negative. In other words, in the latter two countries, public debts exceed the total value of public assets. This is a striking fact, and I will say more later about its significance and implications. At this stage, note simply how rapid the change has been. When I published Capital in the Twenty-First Century in 2013/2014, the latest available complete data sets pertained to the years 2010–2011; among developed countries, only Italy had public debt that exceeded public capital.38 Six years later, in 2019, with data available through 2016–2017, the United States and United Kingdom have also entered the realm of negative public wealth.

By contrast, China appears to have settled on a permanent mixed economy. Of course, it is impossible to predict how things will evolve in the long run: the Chinese case is in many ways unique.39 The country is in the throes of debate about further privatizations, and it is difficult to predict what the outcome will be. For the foreseeable future the current equilibrium will most likely continue, especially since the demand for change is coming from opposing ideological camps and taking contradictory forms. A number of “social-democratic” intellectuals are demanding new forms of power sharing and decentralization with an important role for worker representatives and independent trade unions (which currently do not exist) and a diminished role for the party officials at both the state and local level.40 By contrast, business circles are demanding further privatizations and reinforcement of the role of private shareholders and market mechanisms with an eye to moving China closer to a capitalist model of the Anglo-American type. Meanwhile, CCP leaders feel they have good reasons to oppose both sides, whose proposals they fear might threaten the country’s harmonious and balanced growth in the long run (as well as reduce their own role).

Before going further, several points deserve to be highlighted. In general, it is important to keep in mind that the very definitions of public and private property are not set in stone. They depend on specific features of each legal, economic, and political system. The temporal evolutions and international comparisons shown in Fig. 12.6 indicate rough orders of magnitude, but the precision of the data should not be overestimated.

For example, Chinese farmland was partly private before the 1978 reforms, in the sense that it could be passed on from parents to children (along with improvements to the land), provided that the children remained officially rural residents. China has a system of residential registration and mobility control under which every Chinese citizen holds an official residence permit, the hukou, which designates the holder as a rural or urban resident. A rural resident can work in a city and retain ownership of farmland but only if the migration is temporary. If the person wishes to move permanently to the city and satisfies the requirements (primarily years of residence), he may ask for his rural hukou to be converted into an urban one, which is often necessary for spouse and children to have access to schools and public services (such as health care). However, he must then forfeit ownership of any village land, including any capital gains on the land, which can be considerable because of rising land prices (which explains why some urban migrants prefer to hold on to their rural hukou). If the land is forfeited, it reverts to the local government, which can reassign it to other individuals who hold a rural hukou for that particular village. Such land is therefore a form of property somewhere between private and public; the exact rules governing its ownership have evolved over time, and we have tried to take this into account in our estimates, but the results are inevitably approximate.41

Negative Public Wealth, Omnipotence of Private Property

More generally, it is important to note that the notion of public capital used in these estimates is quite restrictive, in the sense that it is largely dependent on concepts and methods normally used for estimating the value of private property. The only public assets included are those that can be exploited economically or sold, and their value is evaluated in terms of the market price they would fetch if sold. For example, public buildings such as schools and hospitals are counted if there are examples of similar assets being sold at market prices that can be observed (or estimated in terms of the price per square foot of similar buildings).42 In all these estimates we have followed the official rules of national accounting as set forth by the United Nations.43 I will say more about these rules in Chapter 13. They raise many issues, especially in regard to natural resources, which are not included in official national accounts until they begin to be exploited commercially. This inevitably results in underestimating the depreciation of natural capital and overestimating the real growth of GDP and national income, since growth depletes existing reserves while contributing to air pollution and global warming, neither of which is reflected in official national accounts.

At this stage, two points are worth mentioning. First, if one were really determined to assign a value to all public assets in the broadest sense of the term, including all aspects of man’s natural and intellectual patrimony (which very fortunately has not been fully privately appropriated, at least not yet)—encompassing everything from landscapes, mountains, oceans, and air to scientific knowledge, artistic and literary creations, and so on—then it is quite obvious that the value of public capital would be far greater than that of all private capital, no matter what definition one attached to the notion of “value.”44 In the present case, it is by no means certain that such an effort of generalized accounting would make any sense or be in any way useful for public debate. Nevertheless, it is important to bear one essential fact in mind: the total value of public and private capital, evaluated in terms of market prices for national accounting purposes, constitutes only a tiny part of what humanity actually values—namely, the part that the community has chosen (rightly or wrongly) to exploit through economic transactions in the marketplace. I will discuss this point in detail in Chapter 13 in connection with the issues of global warming and knowledge appropriation.

Second, because natural capital has an inherent tendency to depreciate, the share of public capital (in the restricted sense of marketable assets) in official national accounts underestimates the magnitude of ongoing changes. The fact that public capital (in the narrow sense) has fallen to zero or below in most capitalist countries is extremely worrisome (Fig. 12.6). Indeed, it significantly reduces the maneuvering room of governments, especially when it comes to tackling major issues such as climate change, inequality, and education. Let me be clear about the meaning of negative public capital such as we find today in the official national accounts of the United States, United Kingdom, and Italy. Negative capital means that even if all marketable public assets were sold—including all public buildings (such as schools, hospitals, and so on) and all public companies and financial assets (if they exist)—not enough money would be raised to repay all the debt owed to the state’s creditors (whether direct or indirect). Concretely, negative public wealth means that private individuals own, through their financial assets, not only all public assets and buildings, on which they collect interest, but also a right to draw on future tax receipts. In other words, total private property is greater than 100 percent of national capital because private individuals own not only tangible assets but also taxpayers (or some of them, at any rate). If net public wealth becomes more and more negative, a growing and potentially significant share of tax revenues could go to pay interest on the debt.45