{ NINE }

Ternary Societies and Colonialism: Eurasian Trajectories

In previous chapters we studied first slave societies and then postslave colonial societies, looking in particular at the cases of Africa and India. Before beginning our study of the crisis of proprietarian and colonial societies in the twentieth century, which we will do in Part Three, we must first complete our analysis of colonialism and its consequences for the transformation of non-European inequality regimes. In this chapter we will be looking specifically at the cases of China, Japan, and Iran and, more generally, at the way in which the encounter between European powers and the principal Asian state structures affected the political-ideological and institutional trajectories of these various inequality regimes.

We will begin by examining the central role played by rivalries among European states in the development of unprecedented levels of fiscal and military capacity in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, far beyond the capacities of the Chinese and Ottoman empires in the same period. This European state power, spurred by intense competition among states and sociopolitical communities of comparable size in Europe (especially France, the United Kingdom, and Germany), was largely responsible for the West’s military, colonial, and economic domination, which for a long time was the characteristic feature of the modern world. We will then analyze the various ideological and political constructs that supplanted trifunctional society in Asia in the wake of the encounter with European colonialism. In addition to the Indian case, which we have already discussed, we will be looking at Japan, China, and Iran. Once again, we will find that many trajectories were possible, and this leads us to minimize the role of cultural or civilizational determinism and to emphasize instead the importance of sociopolitical developments and the logic of events in the transformation of inequality regimes.

Colonialism, Military Domination, and Western Prosperity

We have already touched at several points on the central role of slavery, colonialism, and the most brutal forms of coercion and military domination in the rise of European power between 1500 and 1960. It is hard to deny that pure force played a key role in the triangular trade that brought slaves from Africa to French and British slave colonies, the southern United States, and Brazil. The fact that the raw material extracted from slave plantations yielded considerable profits to the colonial powers and that cotton in particular played a central role in the takeoff of the textile industry is also well established. We have also seen that the abolition of slavery led to generous compensation for the slaveowners (in the Haitian case resulting in a heavy debt to France that was not repaid until 1950, and in the American case resulting in the denial of civil rights to the descendants of slaves until the 1960s—or in South Africa until the 1990s). Finally, we saw how postslave colonialism relied on various forms of legal and status inequality, including forced labor, which persisted in France’s colonies until 1946.1

We turn now to the question of how European military domination, which gradually emerged in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and led to European hegemony in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, depended on the European states’ development of an unprecedented level of fiscal and administrative capacity. Although the sources that would enable us to measure the tax revenues of all these countries prior to the nineteenth century are limited, certain facts are well established. In particular, recent research has shown that it is possible to collect reasonably homogeneous data on tax receipts for the major European countries and the Ottoman Empire from the early sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries.2 The main difficulty is to compare the numbers in a meaningful way. Although the populations of the countries in question are relatively well understood, at least to a first approximation, the same cannot be said of their levels of economic activity, about which our information is woefully incomplete. It is also important to remember that many obligatory (or quasi-obligatory) payments at that time were made not to the state but to other actors, such as religious organizations, pious foundations, and local seigneuries or military orders, not only in Europe but also in the Ottoman Empire, Persia, India, and China; comparison along these lines might also be interesting. In what follows, however, attention will be focused solely on monies collected by the central government in the strict sense of the word.

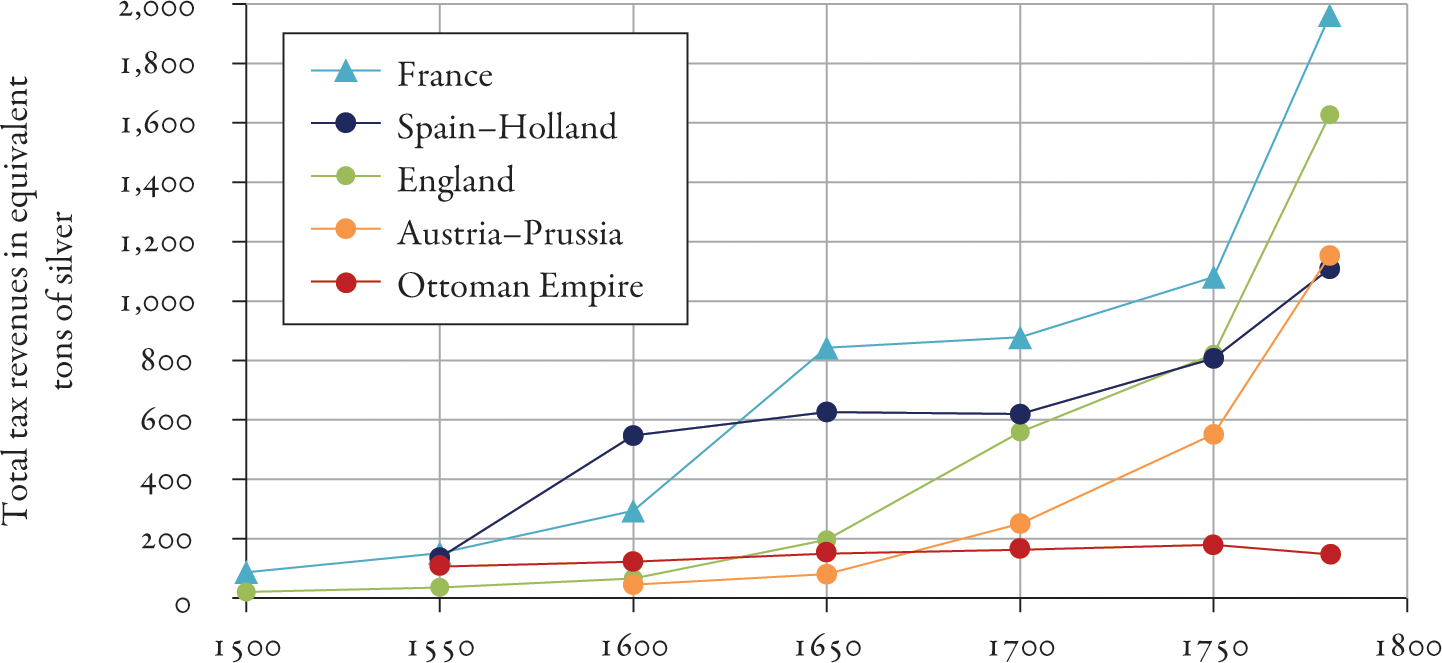

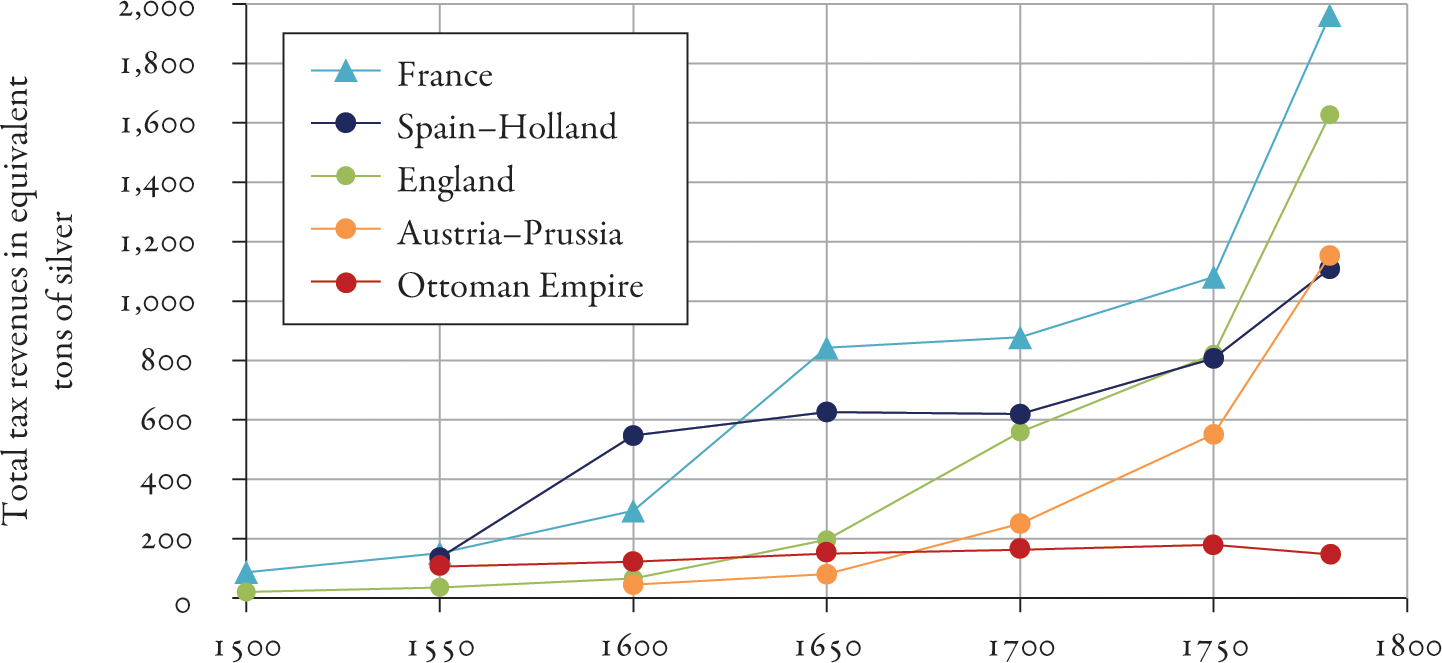

One way to proceed would be to estimate the gold or silver equivalent of the sums collected by states in various currencies. Since all currencies at the time had a metallic base, this would give us a good idea of each state’s capacity to pay for its policies by remunerating its soldiers, purchasing commodities, or financing the construction of roads and ships. What we find is a prodigious increase in the sums collected by European states between the early sixteenth and the late eighteenth centuries. In the period 1500–1550, the tax receipts of the major European powers such as France and Spain amounted to 100–150 tons of silver per year, roughly the same as the Ottoman Empire. At that time England was taking in barely fifty tons a year, partly owing to its smaller population.3 In the centuries that followed these sums would grow spectacularly, mainly due to the intensifying rivalry between England and France: both countries were taking in 600–900 tons of silver in 1700, 800–1,100 tons in the 1750s, and 1,600–1,900 tons in the 1780s, leaving all other European powers far behind. Importantly, Ottoman tax receipts remained virtually unchanged from 1500 to 1780: barely 150–200 tons. After 1750, it was not only France and England that had a far greater tax capacity than the Ottoman Empire; so did Austria, Prussia, Spain, and Holland (Fig. 9.1).

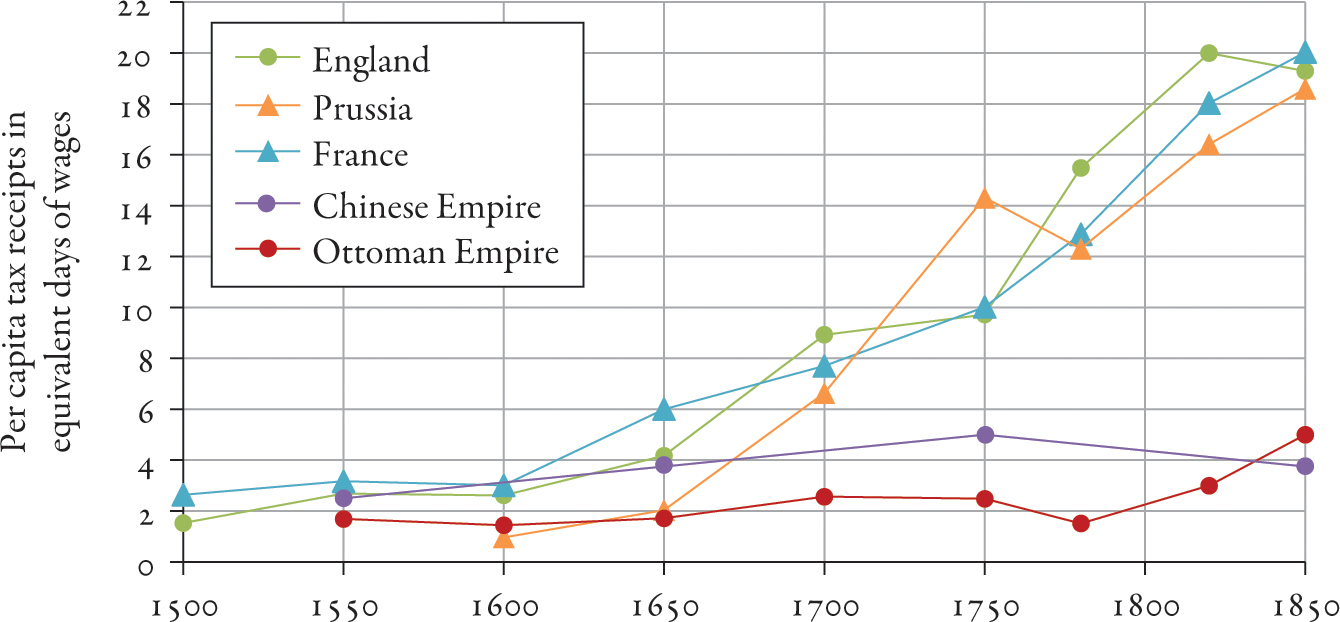

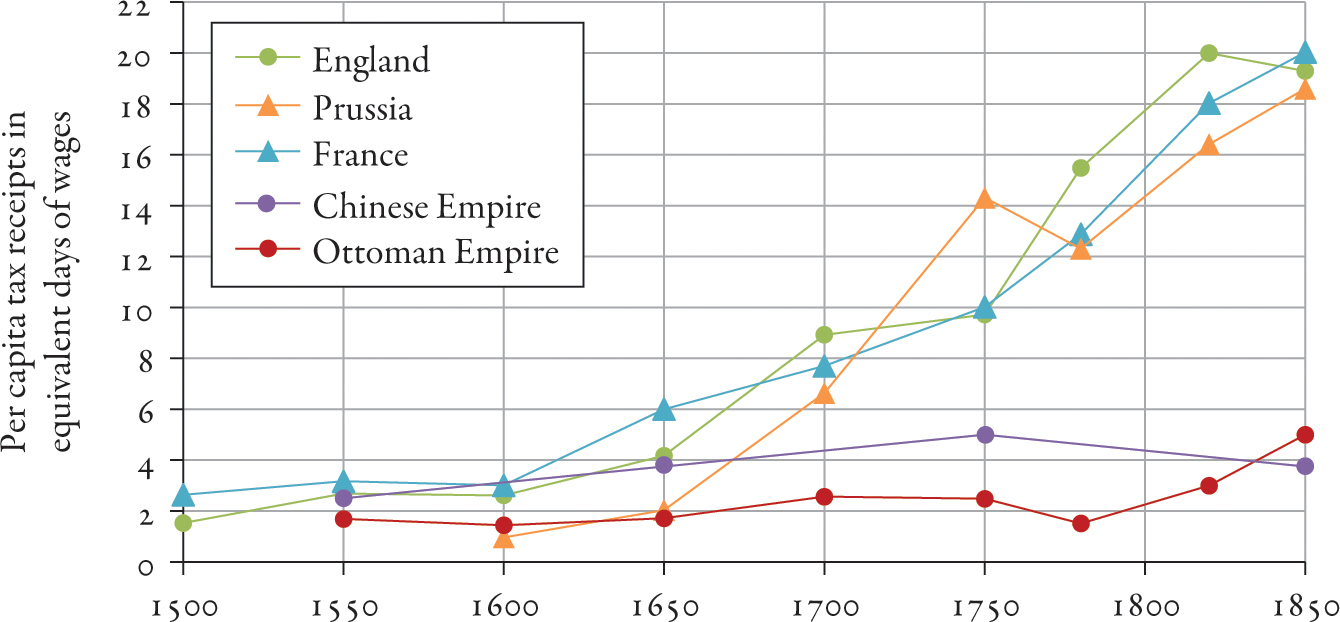

These changes can be explained in part by population changes (recall that in the eighteenth century France was by far the most populous country in Europe) and changes in output (England, for instance, made up for its smaller population by producing more per capita). But the main reason for the increase in tax receipts was intensified fiscal pressure from European governments while Ottoman appetites remained stable. A good way to measure the intensity of taxation is to look at tax receipts per capita and compare the results with daily wages in urban construction. Urban construction wages are relatively well known and easy to compare across countries over a long period both in Europe and the Ottoman Empire and to some extent in China. The available data are imperfect, but the orders of magnitude are quite striking. We find, for example, that per capita tax receipts amounted to two to four days of unskilled urban labor in the period 1500–1600 in Europe, the Ottoman Empire, and the Chinese empire. Tax pressure then intensified in Europe in the period 1650–1700. It rose to ten to fifteen days of wages in the period 1750–1780 and to nearly twenty days in 1850, following very similar trajectories in the major states, including France, England, and Prussia, where state and nation building (though begun much earlier) picked up speed in the eighteenth century. The growth of fiscal pressure in Europe was extremely rapid: although there was no clear difference between Europe, the Ottoman Empire, and China in 1650, the gap begins to widen around 1700 and becomes significant in the period 1750–1780 (Fig. 9.2).

FIG. 9.1. State fiscal capacity, 1500–1780 (tons of silver)

Interpretation: In 1500–1550, tax receipts of the principal European states as well as the Ottoman Empire were equivalent to 100–200 tons of silver per years. In the 1780s, the tax receipts of England and France were between 1600 and 2000 tons of silver per year, while those of the Ottoman Empire remained below 200 tons. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

Why did European states increase their fiscal pressure in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and why did the Ottomans and Chinese not follow suit? To be clear, note that this level of fiscal pressure is still very low compared with modern times. As we will see in subsequent chapters, taxes and other obligatory payments in Europe and the United States did not exceed 10 percent of national income throughout the nineteenth century and until World War I before jumping upward between 1910 and 1980 and then stabilizing at between 30 and 50 percent of national income after 1980 (see Fig. 10.14). In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries fiscal pressure was relatively low (never above 10 percent of national income) compared with modern times.

FIG. 9.2. State fiscal capacity, 1500–1850 (days of wages)

Interpretation: In 1500–1600, per capita tax receipts in Europe were equivalent to two to four days of unskilled urban labor; in 1750–1850 this rose to ten to twenty days of wages. Receipts remained around two to five days of wages in the Ottoman and Chinese Empires. With national income per capita of around 250 days of urban wages, this meant that receipts stagnated at 1–2 percent of national income in the Chinese and Ottoman Empires but rose from 1–2 to 6–8 percent in Europe. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

It is also interesting to note that the earliest estimates of national income (that is, the total income in cash and kind earned by the residents of a given country) appeared in the United Kingdom and France around 1700, thanks to authors such as William Petty; Gregory King; Pierre Le Pesant, sieur de Boisguilbert; and Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban.4 The purpose of their work was to estimate the state’s fiscal potential and consider possible reforms of the tax system at a time when everyone felt that the central state was increasing its fiscal pressure and needed to take a more rational, quantitative approach to its finances. Estimates of national income were based on calculations of surface area and agricultural output as well as on commercial and wage data (including wages in the construction sector), and they provide useful orders of magnitude. The national income and gross domestic product series based on seventeenth-and eighteenth-century data enable us to see overall levels and progressions, but the decade-by-decade changes are too uncertain to use here, which is why I prefer to express the evolution of tax receipts in terms of tons of silver and days of unskilled urban labor (units of measurement better adapted to statistical work on these periods). To clarify our thinking, however, we can say the following: the increase in per capita tax receipts that we see in France, the United Kingdom, and Prussia, from two to four days’ wages in 1500–1550 to fifteen to twenty days’ wages in 1780–1820, corresponds to an increase in total tax receipts from barely 1–2 percent of national income in the early sixteenth century to about 6–8 percent of national income in the late eighteenth century (Fig. 9.2).5

When the State Was Too Small to Be the Night Watchman

As rough as these approximations may be, the orders of magnitude are worth keeping in mind because they correspond to very different state capacities. A state that claims only 1 percent of national income has very little power and very little capacity to mobilize society. Broadly speaking, it can put 1 percent of the population to work on tasks it deems useful.6 By contrast, a state that claims around 10 percent of national income as taxes can put about 10 percent of the population to work (or finance transfers or purchases of goods and equipment of a similar amount), which is a good deal more. Concretely, with tax receipts of 8–10 percent of national income, which is what European states were collecting in the nineteenth century, it is certainly not possible to pay for an elaborate educational, health, and welfare system (with free elementary and high schools, universal health insurance, retirement pensions, social transfer payments, and so on), which as we will see required much higher levels of fiscal pressure in the twentieth century (typically 30–50 percent of national income). By contrast, such sums are more than sufficient to allow the centralized state to pay for “night watchman” functions such as police forces and courts capable of maintaining order and protecting property at home along with equipping a military capable of projecting force abroad. In practice, when the fiscal pressure rose to around 8–10 percent of national income as in Europe in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, or even 6–8 percent as in the late eighteenth century, military expenses alone generally absorbed half of all tax revenues and in some cases more than two-thirds.7

By contrast, a state with barely 1–2 percent of national income in tax receipts is condemned to be a weak state, incapable of maintaining order and carrying out even the minimal functions of the night watchman state. By this measure, most states around the world were weak until relatively recent times; this is true of European states until the sixteenth century and of the Ottoman and Chinese states until the nineteenth century. More precisely, the latter were weakly centralized state structures, incapable of autonomously guaranteeing the security of people and property and of maintaining public order and enforcing respect for the rights of property throughout the territory supposedly under their control. In practice, to carry out these regalian tasks, these states relied on various local entities and elites—seigneurial, military, clerical, and intellectual elites within the framework of trifunctional society in one of its many variants. Once European states developed a more significant fiscal and administrative capacity, new dynamics were set in motion.

Within the countries in question, the development of the centralized state coincided with the transformation of ternary societies into ownership societies, accompanied by the rise of proprietarian ideology and based on strict separation of regalian powers (henceforth the monopoly of the state) from property rights (supposedly open to all). Abroad, the capacity of European states to project force beyond their borders led to the formation first of slave and then of colonial empires and to the development of the various political-ideological constructs around which these were structured. In both cases, the processes by which fiscal and administrative capacities were constructed were inseparable from political-ideological developments. State capacities always developed with an eye to structuring domestic and international society (in the rivalry with Islam, for example); the process, unstable by nature, always involved social and political conflict.

To summarize, the development of the modern state involved two great leaps forward. The first unfolded between 1500 and 1800 in the leading states of Europe, which were able to increase their tax revenues from barely 1–2 percent of national income to about 6–8 percent. This process was accompanied by the development of ownership societies at home and colonial empires abroad. The second leap forward came in the period 1910–1980, when the rich countries as a group went from tax revenues of 8–10 percent of national income on the eve of World War I to revenues of 30–50 percent of national income in the 1980s. This transformation was accompanied by a broad process of economic development and historic improvement in living conditions and gave rise to various forms of social-democratic society. Within this general pattern different trajectories were possible. It proved difficult to extend the second leap forward to poorer countries in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, as we will see later.

Back to the initial question: Why did the first leap forward, the development of an unprecedented fiscal capacity, take place in the leading European states in the period 1500–1800 and not in, say, the Ottoman Empire or Asia? There is no single answer to this question and no deterministic explanation. Nevertheless, one factor seems to have been particularly important: specifically, the political fragmentation of Europe into several states of comparable size, which led to intense military rivalries. From this another question naturally follows: What was the reason for Europe’s political fragmentation compared with the relative unity of China or even (to a lesser degree) India? It is possible that geographical and physical barriers played a role in Europe, especially in Western Europe (where France is separated from its most important neighbors by mountains, seas, or rivers). Clearly, however, different states might have emerged on different parts of European soil or in other parts of the world had socioeconomic and political-ideological developments taken a different course.

Nevertheless, if we take as given the state borders that existed in 1500, and if we then examine the sequence of events that led to the near tenfold increase of European state fiscal capacity between 1500 and 1800 (Figs. 9.1–9.2), we find that each major increase in tax revenues corresponded to a need to recruit new soldiers and field more armies in view of the quasi-permanent state of war that existed in Europe at the time. Depending on the nature of the political regime and the socioeconomic structure of each country, these recruitment needs led to the development of extensive fiscal and administrative capacities.8 Historians have focused mainly on the Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648), the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714), and the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763), the first European conflict of truly global scope since it involved the colonies in America, the West Indies, and India and laid the groundwork for revolutions in the United States, Latin America, and France. But in addition to these major conflicts, there was also a host of shorter, more localized wars. If we include all military conflicts across the continent in each period, we find that European countries were at war 95 percent of the time in the sixteenth century, 94 percent in the seventeenth century, and still 78 percent in the eighteenth century (compared with 40 percent in the nineteenth century and 54 percent in the twentieth century).9 The period 1500–1800 was one of incessant rivalry among Europe’s military powers, and this is what fueled the development of unprecedented fiscal capacity as well as numerous technological innovations, particularly in the areas of artillery and warships.10

By contrast, the Ottoman and Chinese states, which had fiscal capacities close to those of European states in the period 1500–1550 (Figs. 9.1–9.2), did not face the same incentives. Between 1500 and 1800 they ruled large empires in a relatively decentralized fashion and felt no need to increase their military capacity or fiscal centralization. Heightened competition among the medium-sized European states that were organizing themselves in this same period does indeed appear to have been the central factor in the development of specific state structures—structures that were more highly centralized and fiscally developed than the states emerging in the Ottoman, Chinese, and Mughal empires. In the beginning, European states developed their fiscal and military capacity primarily because of internal conflict in Europe, but ultimately this competition endowed these states with much greater power to strike states in other parts of the world. In 1550, the Ottoman infantry and navy comprised roughly 140,000 men, equal to the French and English forces combined (respectively, 80,000 men and 70,000 men). This equilibrium would be disrupted over the next two centuries, which were marked by endless wars in Europe. By 1780, Ottoman forces remained virtually unchanged (150,000 men), while the French and English armies and navies now numbered 450,000 (280,000 soldiers and sailors for France, 170,000 for England); in warships and firepower they also enjoyed marked superiority over potential enemies. To these numbers one must add 250,000 men for Austria and 180,000 for Prussia (states that had had no military to speak of in 1550).11 In the nineteenth century, the Ottoman and Chinese empires were clearly dominated militarily by the states of Europe.12

Interstate Competition and Joint Innovation: The Invention of Europe

Is Western economic prosperity due entirely to the military domination and colonial power that European states exercised over the rest of the world in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries? Clearly, it is very difficult to give a single answer to such a complex question, especially since military domination also fostered technological and financial innovations that proved useful in themselves. In the abstract, one can imagine historical and technological trajectories that would have enabled the countries of Europe to enjoy the same prosperity and the same Industrial Revolution without colonization: for instance, if planet Earth had been one vast European island-continent allowing no possibility of foreign conquest, no “great discovery” of other parts of the world, and no extraction of any kind. To conceive such a scenario would require a certain imagination, however, as well as a willingness to speculate boldly on the pace of technological innovation.

Kenneth Pomeranz has shown in his book on “the great divergence” how much the Industrial Revolution of the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries—first in Britain and then in the rest of Europe—depended on large-scale extraction of raw material (especially cotton) and energy (especially in the form of wood) from the rest of the world—extraction achieved through coercive colonial occupation.13 In Pomeranz’s view, the more advanced parts of China and Japan had attained a level of development in the period 1750–1800 more or less comparable to corresponding regions of Western Europe. Specifically, one finds similar forms of economic development based in part on demographic growth and intensive agriculture (made possible by improved agricultural techniques as well as a considerable increase in cultivated acres thanks to land clearing and deforestation); one also finds comparable process of proto-industrialization, particularly in the textile industry. Subsequently, Pomeranz argues, two key factors caused European and Asian trajectories to diverge. First, European deforestation, coupled with the presence of readily available coal deposits, especially in England, led Europe to switch quite rapidly to sources of energy other than wood and to develop corresponding technologies. More than that, the fiscal and military capacity of European states, largely a product of their past rivalries and reinforced by technological and financial innovations stemming from interstate competition, enabled them in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to organize the international division of labor and supply chains in particularly profitable ways.

Regarding deforestation, Pomeranz insists that by the end of the eighteenth century Europe came close to confronting a very significant “ecological” constraint. Forests in the United Kingdom, France, Denmark, Prussia, Italy, and Spain had been shrinking rapidly for several centuries: whereas they had once covered 30–40 percent of the land area around 1500, by 1800 they had decreased to little more than 10 percent (16 percent in France, 4 percent in Denmark). At first, imported wood from still-forested areas in eastern and northern Europe partially made up for the loss, but these new supplies quickly proved to be insufficient. China also experienced deforestation between 1500 and 1800 but to a lesser degree than in Europe, in part because the more advanced regions were better integrated politically and commercially with the wooded inland regions.

In the European case, the “discovery” of America, the triangular trade with Africa, and commerce with Asia made it possible to overcome this ecological constraint. The exploitation of land in North America, the West Indies, and South America using slave labor imported from Africa produced the raw materials (wood, cotton, and sugar) that not only earned handsome profits for the colonizers but also fed the textile factories that began to develop rapidly in the period 1750–1800. Military control of long-distance shipping routes allowed for the development of large-scale complementarities. The profits earned by exporting British textiles and other manufactured goods to North America compensated the owners of the plantations that produced wood and cotton, who could then feed their slaves with a portion of their profits. Note that a third of the textiles used to clothe slaves in the eighteenth century came from India, while imports from Asia (textiles, silk, tea, porcelain, and so on) were paid for in large part with silver mined in America from the sixteenth century on. By 1830, British imports of cotton, wood, and sugar required the exploitation of more than 10 million hectares of cultivable land, according to Pomeranz’s calculations, or 1.5–2 times all the cultivable land available in the United Kingdom.14 If the colonies had not made it possible to circumvent the ecological constraint, Europe would have needed to find other sources of supply. One is of course free to imagine scenarios of historical and technological development that would have enabled an autarkic Europe to achieve a similar level of industrial prosperity, but it would take considerable imagination to envision fertile cotton plantations in Lancashire and soaring oaks springing from the soil outside Manchester. In any case, this would be the history of another world, having little to do with the one we live in.

It seems wiser to take as given the fact that the Industrial Revolution emerged from Europe’s intimate ties to America, Africa, and Asia and to think about alternative ways in which these relationships might have been organized. What happened, as we have seen, was that international relations were shaped by European military and colonial domination, which made possible the forced transfer of slave labor from Africa to America and the West Indies, the forcible opening of Indian and Chinese ports, and so on. But those relations did not have to be as they were; they might have been organized in countless other ways, allowing for fair trade, free migration of labor, and decent wages, had the political and ideological balance of power been other than it was. By the same token, it is possible to imagine many ways of structuring global economic relations in the twenty-first century under many different sets of rules.

Accordingly, it is striking to note how little Europe’s successful military strategies and institutions in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries resembled the virtuous institutions that Adam Smith recommended in The Wealth of Nations (1776). In that foundational text of economic liberalism, Smith advised governments to adhere to low taxes and balanced budgets (with little or no public debt), absolute respect for property rights, and markets for labor and goods as integrated and competitive as possible. In all these respects, Pomeranz argues, Chinese institutions in the eighteenth century were far more Smithian than the United Kingdom’s. In particular, China’s markets were much more integrated. The grain market operated over a much broader geographic area, and labor mobility was significantly greater. One reason for this was the continuing influence of feudal institutions in Europe, at least until the French Revolution. Serfdom persisted in Eastern Europe until the nineteenth century (whereas it had almost totally disappeared from China by the early sixteenth century). Furthermore, there were more restrictions on labor mobility in Western Europe in the eighteenth century, especially in the United Kingdom and France, owing to Poor Laws and the great latitude granted to local elites and seigneurial courts to impose coercive regulations on the laboring classes. Europe also suffered from the prevalence of ecclesiastical property, much of which could not be sold.

Last but not least, taxes were much lower in China: barely 1–2 percent of national income compared with 6–8 percent in Europe in the late eighteenth century. The Qing dynasty enforced strict budget orthodoxy: taxes paid for all expenses, and there was no deficit. By contrast, European states, starting with France and the United Kingdom, accumulated significant public debt despite their higher taxes, especially in wartime, because tax revenues were never enough to cover the exceptional expenses of war together with interest payments on the accumulated debt.

On the eve of the French Revolution, both France and the United Kingdom had amassed public debts close to a year’s national income. By the end of the American Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (1792–1815), British public debt had soared to more than 200 percent of national income; the debt was so high that one-third of the taxes paid by British taxpayers between 1815 and 1914 (mainly by people of middle and low income) was devoted to repayment of the debt and interest (profiting the wealthy who had lent the government money to pay for the wars). We will come back to all this later when we look at the problems posed by public debt and its reimbursement in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. At this stage, note simply that these colossal debts do not seem to have impeded European development. Like Europe’s higher tax rates, its debts helped to build state and military capacity that proved decisive for increasing European power. To be sure, taxes and debts might have been used to pay for things more useful than armies in the long run (such as schools, hospitals, roads, and clean water). It also might have been preferable to tax the wealthy rather than allow them to become still wealthier by buying government bonds. In view of the era’s violent interstate competition, and with political power in the hands of the wealthy, the choice was made to spend money on the military and to finance it with public debt, and this helped to secure European domination over the rest of the world.

On Smithian Chinese and European Opium Traffickers

In the abstract, Smith’s tranquil, virtuous institutions might have made sense if all countries had adopted them in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (although he underestimated the usefulness of taxes for financing productive investment and neglected the importance of educational and social equality for economic development). But in a world in which some countries develop superior military capacity, the most virtuous are not always the ones who come out on top. The history of European-Chinese relations is a case in point. By the eighteenth century Europe had exhausted the supply of American silver with which it had paid for its trade with China and India, and Europeans feared they might have nothing to sell in exchange for imported silk, textiles, porcelain, spices, and tea from the two Asian giants. The British accordingly attempted to intensify their growing of opium in India to export to Chinese resellers and consumers who had developed a taste for it. The opium trade grew substantially over the course of the eighteenth century, and in 1773 the East India Company established its monopoly over the production and export of the drug from Bengal.

The Qing emperor, seeing the enormous increase in opium imports and under pressure from his bureaucracy and enlightened public opinion to stop it, tried to enforce a ban on the recreational use of opium in 1729. Subsequent emperors took a more proactive approach for obvious public health reasons. In 1839 the emperor ordered his envoy in Canton not only to end the traffic but also to burn existing opium stores without delay. In late 1839 and early 1840, the British press launched a vigorous anti-China campaign, which was paid for by opium dealers; articles denounced China’s unacceptable violation of British property rights and attack on the principle of free trade. Unfortunately, the Qing emperor had seriously underestimated the UK’s progress in increasing its fiscal and military capacity: in the First Opium War (1839–1842) Chinese forces were quickly routed. The British sent a fleet to shell Canton and Shanghai and forced the Chinese in 1842 to sign the first “unequal treaty” (as Sun Yat-sen would call it in 1924). The Chinese indemnified the British for the destroyed opium and war costs while granting British merchants legal and fiscal privileges and ceding the island of Hong Kong.

The Qing government nevertheless refused to legalize the opium trade. England’s trade deficit continued to grow until the Second Opium War (1856–1860), and the sack of the summer palace in Beijing by French and British troops in 1860 finally forced the emperor to give in. Opium was legalized, and the Chinese were obliged to grant the Europeans a series of trading posts and territorial concessions and forced to pay a large war indemnity. In the name of religious freedom it was also agreed that Christian missionaries would be allowed to roam freely in China (while no thought was given to granting similar privileges to Buddhist, Muslim, or Hindu missionaries in Europe). The irony of history is this: owing to the military tribute that the French and British imposed on China, the Chinese government was obliged to abandon its Smithian budget orthodoxy and for the first time experiment with a large public debt. The debt snowballed, and the Qing were forced to raise taxes to repay the Europeans and eventually to cede more and more of their fiscal sovereignty, following a classic colonial scenario of coercion through debt, which we have already encountered elsewhere (in Morocco, for example).15

Another important point about the very heavy public debts that European states took on to finance their internecine wars in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries: these played an important role in the development of financial markets. This is true in particular of British debt issued during the Napoleonic wars, which to this day represents one of the highest levels of national debt ever attained (more than two years of national income or GDP, which was a lot, especially in view of the country’s share of the global economy in 1815–1820). To sell this debt to wealthy and thrifty British subjects, the country had to develop a solid banking system and networks of financial intermediation. I have already alluded to the role of colonial expansion in creating the first global-scale joint-stock companies—the British East India Company and Dutch East India Company, companies that commanded veritable private armies and exercised regalian powers over vast territories.16 The many costly uncertainties associated with maritime trade also encouraged the development of insurance and freight companies, which would have a decisive impact later on.

Public debt linked to European warfare also drove the process of securitization and other financial innovations. Some experiments in this area ended in resounding failure, starting with the famous bankruptcy of John Law in 1718–1720, which stemmed from competition between France and Britain to redeem their debts by offering the bearers of government bonds stock in colonial companies, some of whose assets were rather dubious (like those of the Mississippi company that triggered the collapse of Law’s “Mississippi bubble”). At the time, most joint-stock companies derived their revenues from colonial commercial or fiscal monopolies; they were more a sophisticated, militarized form of highway robbery than a productive entrepreneurial venture.17 In any case, by developing financial and commercial technologies on a global scale, Europeans created infrastructure and comparative advantages that would prove decisive in the age of globalized industrial and financial capitalism (in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries).

Protectionism and Mercantilism: The Origins of the “Great Divergence”

Recent research has largely confirmed Pomeranz’s conclusions concerning the origins of the “great divergence” and the central role of military and colonial domination and the financial and technological innovations that went with it.18 In particular, Jean-Laurent Rosenthal and R. Bin Wong insist that while Europe’s political fragmentation has had largely negative effects over the very long run (illustrated by Europe’s self-destruction in 1914–1945 as well as difficulties forming a European union after World War II or, more recently, facing up the financial crisis of 2008), it nevertheless allowed European states to gain the upper hand over China and the rest of the world from 1750 to 1900, thanks in large part to innovations stemming from military rivalries.19

Sven Beckert’s work has also shown the crucial importance of slave extraction and cotton production in the seizure of control of the global textile industry by the British and other Europeans in the period 1750–1850. In particular, Beckert points out that half of the African slaves shipped across the Atlantic between 1492 and 1882 sailed in the period 1780–1860 (especially between 1780 and 1820). This late phase of accelerated growth in the slave trade and cotton plantations played a key role in the rise of the British textile industry.20 Finally, the Smithian idea that the British and European advance was due to peaceful and virtuous parliamentary and proprietarian institutions has few champions nowadays.21 Some researchers have collected detailed data on wages and output that should allow us to compare Europe, China, and Japan before and during “the great divergence.” Despite the deficiencies of the sources, the available data confirm the thesis of a late divergence between Europe and Asia, which begins to take shape only in the eighteenth century, with minor differences among authors.22

Prasannan Parthasarathi emphasizes the key role played by anti-India protectionist policies in the emergence of the British textile industry.23 In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, manufactured export products (such as textiles of all sorts, silk, and porcelain) came mainly from China and India, and they were largely paid for with silver and gold originating in Europe and America (as well as Japan).24 Indian textiles, especially print fabrics and blue calico, were all the rage in Europe and throughout the world. In the early eighteenth century, 80 percent of the textiles that English traders exchanged for slaves in West Africa were manufactured in India, and by the end of the century that figure still remained as high as 60 percent. Freight records show that Indian textiles in the 1770s alone accounted for a third of the cargo loaded in Rouen onto ships bound for Africa to barter for slaves. Ottoman records indicate that Indian textile exports to the Middle East were still greater than those bound for West Africa, which did not seem to pose any major problem for the Turkish authorities, who were more sensitive to the interests of local consumers.

European merchants soon realized that they stood to profit by stirring up hostility against Indian imports to advance their own transcontinental projects. In 1685 the British Parliament introduced customs duties of 20 percent on textile imports, and this rose to 30 percent in 1690 before imports of printed and dyed fabrics were simply banned in 1700. From that date on, only virgin fabrics were imported from India, which allowed British manufacturers to improve their techniques for producing colored fabrics and prints. Similar measures were approved in France while British import restrictions, including a 100 percent tariff on all Indian textiles in 1787, continued to be tightened throughout the eighteenth century. Pressure from Liverpool slave traders, who urgently needed quality textiles to expand their business on the African coast without depleting their metallic currency reserves, played a decisive role, especially between 1765 and 1785, a period during which the quality of English production improved rapidly. Only after acquiring a clear comparative advantage in textiles, most notably through the use of coal, did the United Kingdom begin in the mid-nineteenth century to adopt a more full-throated free trade rhetoric (though not without ambiguities, as in the case of opium exports to China).

The British also relied on protectionist measures in the shipbuilding industry, which was flourishing in India in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In 1815 they levied a special tax of 15 percent on all goods imported on India-built ships; a subsequent measure provided that only English ships could import merchandise from east of the Cape of Good Hope to the United Kingdom. While it is difficult to suggest an overall estimate, it clear that, taken together, these protectionist and mercantilist measures, imposed on the rest of the world at gunpoint, played a significant role in achieving British and European industrial domination. According to available estimates, the Chinese and Indian share of global manufacturing output, which was still 53 percent in 1800, had fallen to 5 percent by 1900.25 Again, it would be absurd to view this as the only possible trajectory leading to the Industrial Revolution and modern prosperity. For instance, one can imagine other historical trajectories that would have allowed European and Asian producers to grow at the same rate (or, together, at an even higher rate) without anti-India and anti-Chinese protectionism, without colonial and military domination, and with more balanced and egalitarian trade and interactions among different regions of the globe. This would certainly be a very different world from the one we live in. But the role of historical research is precisely to demonstrate the existence of alternatives and switch points and to show how choices are conditioned by the political and ideological balance of power among contending groups.

Japan: Accelerated Modernization of a Ternary Society

We turn next to the way in which the encounter with European colonial powers affected the transformation of the ternary inequality regimes prevalent in different parts of Asia before the arrival of Europeans. In Chapter 8 we saw how inequalities in precolonial India were structured by trifunctional ideology, with a kind of rough balance between military warrior elites (Kshatriyas) and clerical and intellectual elites (Brahmins) in a variety of evolving and unstable configurations whose development depended on the emergence of new warrior elites, on competition between Hindu and Muslim kingdoms, and on the shifting identities and allegiances of the jatis. We also saw how the British administration, by rigidifying castes through its colonial policies and censuses, contributed to the emergence of a unique inequality regime in India based on a novel mix of ancient status inequalities and modern inequalities of wealth and education.

The Japanese case is different from the Indian in many ways, but there are also numerous similarities. Japan in the Edo era (1600–1868) was a strongly hierarchical society with many social disparities and status rigidities of the trifunctional type, similar in some respects to those seen in Ancien Régime Europe and precolonial India. Society was dominated on the one hand by a warrior nobility, with daimyos (great feudal lords) at the top under the authority of the shogun (military leader), and on the other hand, by a class of Shinto priests and Buddhist monks (with degrees of symbiosis and rivalry between the two religions which varied over time). The distinctive feature of the Japanese regime in the Edo period was that the warrior class had assumed marked superiority over the others. After restoring order in 1600–1604 following decades of feudal warfare, the hereditary shoguns of the Tokugawa dynasty gradually ceased to be mere military captains and became the real political leaders of the country at the head of an administrative and judicial system centered in the capital Edo (Tokyo) while the emperor in Kyoto was reduce to the symbolic functions of a spiritual leader.

The legitimacy of the shogun and of the warrior class was seriously shaken, however, by the arrival in Tokyo Bay in 1853 of a fleet of heavily armed warships under the command of Commodore Matthew Perry of the United States. When Perry returned in 1854 with an armada twice the size of the first, reinforced by the ships of several European allies (Britain, France, the Netherlands, and Russia), the shogunate had no choice but to grant the commercial, fiscal, and jurisdictional privileges demanded by the coalition. This unmistakable humiliation initiated a phase of intense political and ideological reflection in Japan, resulting in the beginning of a new era, the Meiji, in 1868. The last Tokugawa shogun was deposed and the authority of the emperor was restored at the behest of a segment of the Japanese nobility and elite eager to modernize the country and compete with the Western powers. Japan thus offers an unusual example of accelerated sociopolitical modernization, which began with an imperial restoration (largely symbolic, to be sure).26

The reforms undertaken from 1868 on rested on several pillars. Old status distinctions were eliminated. The warrior nobility lost its legal and fiscal privileges. This reform affected not only the high aristocracy of daimyos (a very small group comparable in size to British lords) but also other warriors endowed with fiefs (revenues derived from village production); both groups received partial financial compensation. The constitution of 1889, inspired by the British and Prussians, provided for a house of peers (which allowed a select portion of the old nobility to retain a political role) and a house of representatives, initially elected on a property-qualified basis by barely 5 percent of adult males, before male suffrage was extended in 1910 and again in 1919, ultimately becoming universal in 1925. Women were given the right to vote in 1947, at which time the house of peers was abolished.27

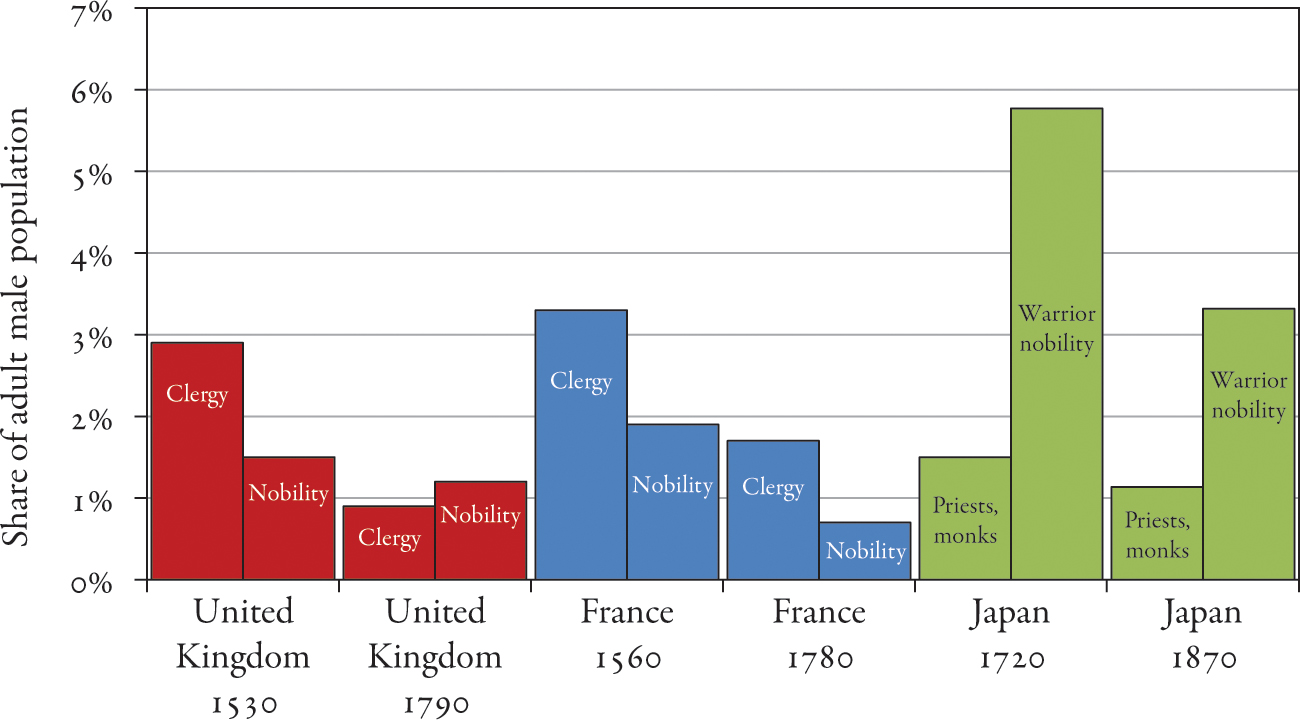

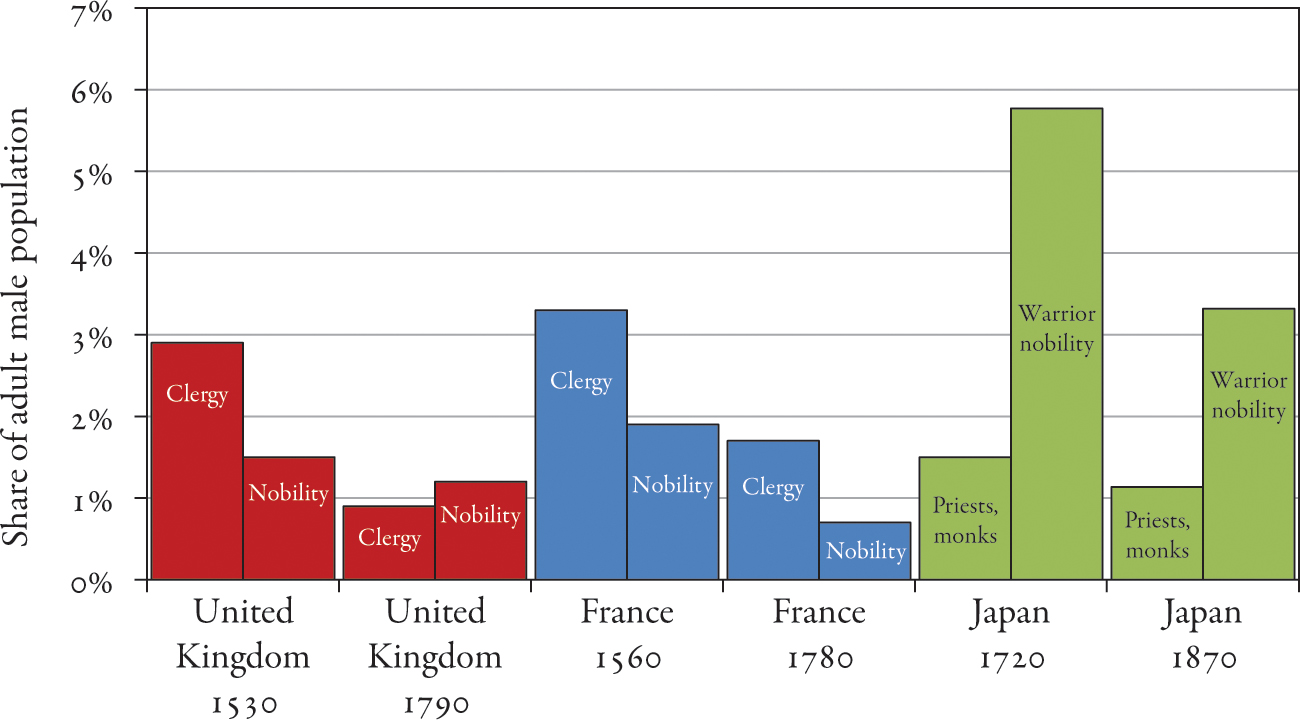

According to the censuses by class carried out under the Tokugawa from 1720 on, the class of daimyos and warriors with fiefs represented 5–6 percent of the population, with considerable variation by region and principality (from 2–3 percent to 10–12 percent). The size of this group seems to have decreased in the Edo era, since the warrior class represented only 3–4 percent of the population in the census of 1868, at the beginning of the Meiji era, shortly before fiefs and the warrior class (except for peers) were abolished. Shinto priests and Buddhist monks accounted for 1–1.5 percent of the population. If we compare this with Europe in the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries, we find that the warrior class was larger in Japan than in France or the United Kingdom while the religious class was slightly smaller (Fig. 9.3).28 As we have seen, other European countries, as well as certain subregions of India, had warrior and noble classes of a size close to or greater than that observed in Japan.29 All things considered, these orders of magnitude are not very different and attest to a certain similarity among trifunctional societies, at least in terms of formal structure.

Beyond the abolition of fiscal privileges and forced labor, the reforms of the early Meiji era eliminated the many status inequalities that had existed among various categories of urban and rural workers under the previous regime. In particular, the new government officially ended discrimination against the burakumin (“hamlet people”), the lowest category of workers under the Tokugawa, whose pariah status was in some ways similar to that of untouchables and aborigines in India. It is generally believed that the burakumin accounted for less than 5 percent of the population in the Edo era, but they were not usually counted in censuses; the category was officially abolished in the Meiji era.30

FIG. 9.3. The evolution of ternary societies: Europe-Japan 1530–1870

Interpretation: In the United Kingdom and France, the two dominant classes in trifunctional society (clergy and nobility) decreased in size between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries. In Japan, the proportion of the warrior nobility (daimyo) and warriors endowed with fiefs was significantly higher than that of Shinto priests and monks, but it decreased sharply between 1720 and 1870, according to Japanese census data from the Edo and early Meiji eras. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

In addition, the Meiji regime developed a series of policies intended to promote accelerated industrialization and catch up with the Western powers. The central government’s fiscal and administrative capacity was rapidly increased (with prefects and regions taking the place of daimyos and fiefs), and significant taxes were levied to finance investments in the social and economic development of the country, especially in the areas of transportation infrastructure (roads, railroads, shipping) and health and education.31

Investment in education was truly spectacular. The intent was not only to train a new elite capable of rivaling Western engineers and scientists but also to bring literacy and education to the masses. With the elites, the motive was clear: to avoid Western domination. Japanese students who sailed from Kagoshima in 1872 to study in Western universities told their stories with no sugarcoating. While stopped at an Indian port on their way to Europe, they watched young Indian children reduced to diving into the ocean after small coins for the amusement of British settlers on the shore. From this they concluded that they had better study like mad in order to make sure that Japan would not experience the same fate.32 Mass literacy and technical training were also seen as indispensable prerequisites for successful industrialization.

On the Social Integration of Burakumin, Untouchables, and Roma

The point here is not to idealize Meiji policies of social and educational integration. Japan remained an inegalitarian hierarchical society. Groups like the burakumin continued to struggle against real (albeit illegal) discrimination even after World War II, and traces of this oppressive legacy persist to this day (though to a much lesser extent than in the case of the lower castes in India). What is more, Japanese social integration went hand in hand with rising nationalism and militarism, which led to Pearl Harbor and Hiroshima.

For some Japanese nationalists, the long conflict with the West from 1854 to 1945 should be seen as the “Great War of East Asia” (as it is called in the military museum of the Yasukuni shrine in Tokyo), a war in which Japan, despite crushing defeats, led the way to the decolonization of Asia and the world. Proponents of this view emphasize Japanese support for independence movements in India, Indochina, and Indonesia during World War II and, more generally, the fact that Europe and the United States had never truly accepted the idea of an independent Asian power and would never have agreed to the end of colonial domination had it not been for the willingness of some Asians to fight. Despite brilliant military victories in China in 1895, Russia in 1905, and Korea in 1910—irrefutable proof of the success of Meiji-era reforms—Japan felt that it could never gain the full respect of the West or be admitted to the club of industrial and colonial powers.33 In the eyes of Japanese nationalists, the ultimate humiliation was the West’s refusal to incorporate the principle of racial equality into the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, despite repeated Japanese demands.34 Even worse was the Washington Naval Conference (1921), which stipulated that the naval tonnage of the United States, United Kingdom, and Japan should remain frozen in the ratio 5–5–3. This rule condemned Japan to eternal naval inferiority in Asian waters no matter what industrial or demographic progress it made. The Japanese empire rejected the agreement in 1934, paving the way to war.

In 1940–1941, two increasingly antagonistic worldviews confronted each other: Japan demanded a full Western withdrawal from East Asia while the United States demanded a withdrawal of all colonial powers (including Japan) from China and deferred the broader issue of decolonization until later. When Roosevelt imposed an oil embargo on Japan, threatening to immobilize its army and navy in short order, Japanese generals felt that they had no choice but to attack Pearl Harbor. This Japanese nationalist view is interesting and in some respects comprehensible, but it omits one essential point: the people of Korea, China, and other Asian countries occupied by Japan do not remember the Japanese as liberators but as yet another colonial power exhibiting the same brutality as the Europeans (or in some cases worse, although this needs to be judged case by case, given the very high bar). The colonial ideology that seeks to liberate and civilize nations in spite of themselves generally leads to disaster, no matter what the color of the colonizer’s skin.35

If we leave aside the always bitter conflicts among colonial powers and ideologies and the memories of the colonized populations, it remains true that the policies of social and educational integration and economic development that Japan adopted in the Meiji era (1868–1912) and that demilitarized Japan continued to pursue after 1945 represent an experiment with the particularly rapid sociopolitical transformation of a premodern inequality regime. The success of Japan’s proprietarian and industrial transition shows that the mechanisms at work have nothing whatsoever to do with Christian culture or European civilization.

Last but not least, the Japanese experience shows that proactive policies, especially regarding public infrastructure and investment in education, can overcome very strong and longstanding status inequalities in a matter of decades—inequalities that in other contexts are seen as rigid and unalterable. Although past discrimination against pariah classes has left traces, Japan nevertheless became over the course of the twentieth century a country whose standard of living is among the highest in the world and whose income inequality falls between European and US levels.36 Japanese government policies intended to achieve socioeconomic and educational development and social integration between 1870 and 1940 were not perfect, but they were a good deal more effective than, for example, British colonial policy in India, which showed little concern with reducing social inequality or improving the literacy and skills of the lower castes. In Part Three of this book we will see that the reduction of social inequality in Japan was further assisted by an ambitious program of agrarian reform in the period 1945–1950 as well as by highly progressive taxation of top incomes and large estates (a policy that began in the Meiji period and continued in the interwar years but was reinforced after the defeat).

In the European context, the Roma are probably the group most directly comparable with the burakumin in Japan and the lower castes in India in terms of social discrimination. The Council of Europe uses the term “Roma” to describe any number of nomadic or sedentarized populations known by various other names (including Tziganes, Romani, Romanichels, Manouchians, Travelers, and Gypsies), most of which have lived in Europe for at least a millennium and can trace their origins back to India and the Middle East, despite a great deal of racial mixing over the years.37 By this definition, the Roma numbered between 10 and 12 million in the 2010s, or roughly 2 percent of the total population of Europe. This is a smaller proportion than the Japanese burakumin (2–5 percent) or the lower castes of India (10–20 percent) but still significant. One finds Roma in nearly every European country, especially Hungary and Romania, where Roma slavery and serfdom were abolished in 1856, after which the newly emancipated populations fled their old masters and scattered across the continent.38

Compared with the fate of the burakumin, untouchables, and aborigines, integration of the Roma was very slow. This can be explained in large part by the absence of adequate integration policies and above all by the fact that European countries have tried to shift responsibility for these groups to others. These excluded groups continue to be the object of prejudices regarding their allegedly alien way of life and supposed refusal to integrate when in fact they are subject to significant discrimination and little effort has been made to integrate them.39 The case of the Roma is particularly interesting in that it can help Europeans, who are often prompt to give lessons to the rest of the world, to gain a better understanding of the difficulties that countries like Japan and India have faced in trying to integrate the burakumin or the lower castes—social groups that have faced prejudices similar to those confronting the Roma. Nevertheless, these countries have succeeded in overcoming prejudice through long-term policies of social and educational integration.

Trifunctional Society and the Construction of the Chinese State

Let us turn now to the way in which colonialism affected the transformation of the Chinese inequality regime. Throughout its history, until the revolution of 1911 that gave rise to the Republic of China, China was organized in terms of an ideological configuration that can be characterized as trifunctional, analogous to the trifunctional regimes found in Europe and India until the eighteenth or nineteenth centuries. However, one important difference has to do with the nature of Confucianism, which is closer to a civic philosophy than to a religion in the sense of Christian, Jewish, or Muslim monotheism or Hinduism. Kongfonzi (Latinized as Confucius) was a peerless scholar and teacher who lived in the sixth and early fifth centuries BCE. Born into a princely family buffeted by the constant conflict among the Chinese kingdoms, Confucius, according to tradition, crisscrossed China to deliver his lessons and demonstrate that peace and social harmony could be achieved only through education, moderation, and a search for rational and pragmatic solutions (which in practice were usually fairly conservative in terms of morals and included respect for elders, property, and property owners). As in all trifunctional societies, the moderation of scholars and men of letters was to play a central role in the political order, balancing the unruliness of the warriors.

Confucianism—ruxue in Chinese (“the teaching of the literati”)—thus became official state doctrine in the second century BCE and remained so until 1911, even as it underwent a series of transformations and exchanged symbioses with Buddhism and Taoism. From time immemorial Confucian literati were seen as scholars and administrators who placed their vast stores of knowledge and competence, their understanding of Chinese literature and history, and their very strict domestic and civil morality at the service of the community, public order, and the state—rather than being seen as a religious organization distinct from the state. This was a fundamental difference between the Confucian and Christian versions of trifunctionality, and it offers one of the most natural explanations for the unity of the Chinese state in contrast to the political fragmentation of Europe (notwithstanding the Catholic Church’s many attempts to bring the Christian kingdoms closer together).40

Some may also be tempted to compare Confucianism, which in the history of the Chinese empire functioned as a “religion of state unity,” with modern Chinese communism, which in a different sense is also a form of state religion. They would argue, in other words, that the Confucian administrators and literati who served the Han, Song, Ming, and Qing emperors have simply evolved into officials and high priests of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), serving the president of the People’s Republic. Such comparisons are sometimes used to suggest that the Communist regime’s efforts to achieve national unity and social harmony are merely a continuation of China’s Confucian past. It was in this spirit that CCP leaders restored Confucius to a place of honor in the early 2010s—a rather remarkable turnabout, since the economic and social conservatism of Confucianism was much criticized during the Cultural Revolution and the campaign against “the four olds” (old things, old ideas, old culture, and old habits), landlords, and mandarins. Abroad but sometimes in China as well, the same historical parallel is often used in a negative sense to suggest that the Chinese government has always been authoritarian with immutable masses under the thumb of a millennial despotism that is a reflection of China’s culture and soul: emperors and their mandarins have simply given way to Communist leaders and apparatchiks. Such comparisons are fraught with difficulties. They assume a continuity and determinism for which there is no evidence and prevent us from thinking about the complexity and diversity of China’s past—and, indeed, the complexity and diversity of all sociopolitical trajectories.

The first problem raised by these comparisons is that the imperial Chinese state utterly lacked the means to be despotic. It was a structurally weak state with extremely limited fiscal revenues and little to no capacity for economic or social intervention or oversight compared with today’s Chinese government. Available studies suggest that tax receipts under the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1912) dynasties never exceeded 2–3 percent of national income.41 If we express per capita tax receipts in terms of days of wages, we find that the resources available to the Qing governments amounted to no more than a quarter to a third of the resources of European states in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries (Fig. 9.2).

The recruitment of imperial and provincial functionaries (whom the Europeans called “mandarins”) followed very strict procedures, including the famous examinations, which were given throughout the empire for thirteen centuries, from 605 to 1905. The examination system made a great impression on Western visitors to China and inspired similar efforts in France and Prussia. But the total number of Chinese functionaries was always quite small: in the middle of the nineteenth century there were barely 40,000 imperial and provincial officials, or 0.01 percent of the population (of around 400 million), and generally 0.01–0.02 percent of the population across the ages.42 In practice, most of the resources of the Qing state were devoted to the warrior class and the army (as is always the case in states of such limited means), and what was left for civil administration, public health, and education was negligible. As we have seen, the Qing state in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries lacked the means to ban the use of opium within its borders. In practice, the Chinese administration operated in an extremely decentralized way, and imperial and provincial officials had no choice but to rely on the power of local warrior, scholar, and landowner elites over which they exerted very limited control, as was also the case in Europe and other parts of the world before the rise of the modern centralized state.43

Another point bears emphasizing: as in other trifunctional societies, the Chinese inequality regime relied on a complex and evolving relationship of compromise and competition between literary and warrior elites; the former did not dominate the latter. This is particularly clear in the era of the Qing dynasty, which began when Manchu warriors conquered China and seized control of Beijing in 1644. The Manchu warrior class arose in early seventeenth-century Manchuria and was organized under the “Eight Banners” system. Warriors were given rights to land and administrative, fiscal, and legal privileges denied to the rest of the population. The Manchus brought their military organization with them to Beijing and gradually integrated new Han Chinese elements into the Manchu warrior elite.

Recent research has shown that the warrior nobility of the Eight Banners (bannermen) included some 5 million people in 1720, or nearly 4 percent of the Chinese population of approximately 130 million. It is possible that this group grew from roughly 1–2 percent of the population at the time of the Manchu conquest in the mid-seventeenth century to 3–4 percent in the eighteenth century as the new regime was consolidated before declining in the nineteenth century. The sources are fragile, however, and there are many problems with such estimates—similar to those we encountered in estimating the size of the nobility in France and elsewhere in Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries—so that it is impossible to be precise in the absence of any systematic census data prior to the twentieth century (an absence indicative, by the way, of the weakness of the central imperial government).44 The figures we have (which show bannermen accounting for 3–4 percent of the population in the eighteenth century) are relatively high compared with the size of the French and British nobility in the same period (Fig. 9.3) but are of the same order as Japan and India45 and lower than the numbers for European countries where the military orders were large and territorial expansion was in progress, such as Spain, Hungary, and Poland.46

At the beginning of the Qing era, the bannermen were primarily stationed in garrisons near large cities. They lived on land rights and income skimmed from local production or paid by the imperial government. In the middle of the eighteenth century, however, the Qing government decided that the warrior nobility was too large and was costing too much to maintain. As in all trifunctional societies, reform was a delicate matter as any radical move against the warrior nobility risked endangering the regime. In 1742 the Qing emperor tried to relocate some of the bannermen to Manchuria. In 1824 this policy took a new turn: with an eye to both cutting the budget and colonizing and exploiting northern China, the imperial government distributed land in northern China to some bannermen and at the same time encouraged non-nobles to move north and work for the new landowners. This was a difficult undertaking, and its scope remained limited on the one hand because most bannermen had no intention of allowing themselves to be shipped north so easily and on the other hand because the immigrant commoners were often better equipped to exploit the land than the nobles, giving rise to frequent tensions. In the early twentieth century, however, one finds interesting proprietarian micro-societies developing in northern Manchuria, where landownership was highly concentrated in the hands of the old warrior nobility.47

Chinese Imperial Examinations: Literati, Landowners, and Warriors

The Qing state was obliged to maintain a certain equilibrium between the warrior class and other Chinese social groups. In practice, however, it attended mainly to the balance among elites. This was true in particular of the organization of the imperial examination system, which was subject to constant reform over its lengthy history as the balance of power shifted among competing groups. The compromises that were struck are interesting because they reflect the search for a balance between the legitimacy of knowledge on the one hand and the legitimacies of wealth and military might on the other. In practice, officials were recruited in several stages. The first step was to pass the examinations that were given two years out of every three in the various prefectures of the empire; those who passed received a certificate (shengyuan). This certificate did not lead directly to a public job but allowed the holder to sit for various other exams for the selection of provincial and imperial officials.

Holding the shengyuan also granted legal, political, and economic privileges (such as the right to testify in court or participate in local government) as well as considerable social prestige, even for those who never became officials. According to available research, based on exam archives and student lists, in the nineteenth century approximately 4 percent of adult males possessed a classical education (in the sense of having an advanced mastery of Chinese writing and traditional knowledge and having sat at least one examination for the shengyuan). Of this number, roughly 0.5 percent of adult males actually passed the exam and obtained the precious certificate. However, a second group of people had the right to sit directly for examinations leading to official jobs: those who had bought a certificate (jiansheng). The size of this group increased in the nineteenth century: it represented 0.3 percent of adult males in the 1820s and nearly 0.5 percent in the 1870s, almost as many as those who had obtained the shengyuan.48

Recent research on the Jiangnan provincial archives has shown that this mechanism significantly increased social reproduction in the selection of officials: it allowed the sons of landowners and other wealthy individuals to have a chance of being recruited without passing the difficult shengyuan examination while at the same time yielding much-needed revenue for the state (which was the justification given for this practice). The archives show that social reproduction was also very high in the classical procedure: the vast majority of candidates who successfully passed the exam and were recruited as imperial or provincial officials had a father, grandfather, or other ancestor who had occupied a similar position; there were exceptions, however (about 20 percent of cases).49

The possibility of buying a shengyuan certificate existed because the Chinese state ran into budgetary problems in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries; it can be compared to the French Ancien Régime practice of selling offices and charges and numerous other public functions as well as similar practices in many other European states. The difference in the Chinese case was that even those who purchased a certificate were in theory required to sit for the same exams as the others to qualify for official posts (although there was widespread suspicion that this final requirement was not always honored, it is not possible to say to what extent these suspicions were justified). The Chinese system was perhaps more like the system for admission to the most prestigious US universities today, who openly admit that certain “legacy students” whose parents have made large enough gifts may receive special consideration in the admissions process. I will come back to this point later, as it raises many issues about what a fair admissions system and a just society might look like today and again illustrates the need to study inequality regimes in historical and comparative perspective, including comparisons across countries, periods, and institutions that might prefer not to be compared.50

As for Chinese imperial examinations, there is another crucial but relatively little-known aspect of the rules in force during the Qing era: roughly half of the 40,000-odd official posts (equal to about 0.01 percent of the total Chinese population in the nineteenth century and 0.03 percent of the adult male population) were reserved for bannermen.51 In practice, members of the warrior class sat for special exams, sometimes in the Manchu language, to make up for their inadequate knowledge of classical Chinese; for certain posts their exams were similar to those taken by holders of real or purchased certificates but with places reserved for the bannermen. This Chinese version of the “reservations” system was very different from the Indian quota system, which favored members of the lower castes, and it extended well beyond qualifying exams for public service jobs. In each administrative department and job category, there were also quotas for members of the warrior aristocracy (Manchus and Hans) and for literati and landowners recruited through other channels.52 These rules were often contested and permanently renegotiated, but broadly speaking, the warrior aristocracy managed to maintain its advantages until the fall of the empire in 1911, and the wealth privilege (linked to the purchase of certificates) was reinforced throughout the nineteenth and into the twentieth centuries, partly owing to the growing budgetary requirements of the Qing state (which had to pay off a growing debt to the European powers).

Chinese Revolts and Missed Opportunities

To sum up, imperial Chinese society was highly hierarchical and inegalitarian and marked by conflicts among literate elites, landowners, and warriors. All available evidence suggests that these groups overlapped to a degree: the literary and administrative elites were also landowners who collected rents from the rest of the population just as the warrior elites did, and there were many alliances among these groups. The regime was far from static, however: not only was there elite conflict, but there were also many popular rebellions and revolutions, which might have taken China along trajectories other than the one it ultimately followed.

The bloodiest and most spectacular was the Taiping Rebellion (1850–1864). In the beginning this was a rebellion like many others, of poor peasants who refused to pay rent to landowners and who illegally occupied the land. Such revolts had always been common, but they proliferated and became more threatening to the regime after China’s humiliating defeat at the hands of the Europeans in the First Opium War (1839–1842). In fact, the Taiping Rebellion came close to toppling the Qing empire in 1852–1854 in the early years of the movement. The rebels established a capital in Nanking, near Shanghai. In 1853 the regime issued a decree promising to redistribute land to families according to their needs and began to implement it in regions controlled by the rebels. On June 14, 1853, Karl Marx published an article in the New York Daily Tribune stating that the rebellion was on the brink of victory and that events in China would soon provoke turmoil throughout the industrial world, leading to a series of revolutions in Europe. The conflict quickly developed into a vast civil war in the heart of China, pitting imperial forces based in the north (and backed by a relatively weak state) against increasingly well-organized Taiping rebels in the south, in a country whose population had grown enormously over the previous century (from about 130 million in 1720 to nearly 400 million in 1840) despite being ravaged by opium and famine. According to available estimates, the Taiping Rebellion may have caused between 20 and 30 million military and civilian deaths between 1850 and 1864, or more than all the deaths in World War I (which claimed 15 to 20 million lives). Research has shown that the Chinese regions most affected by the rebellion never completely recovered from their population losses as fighting continued in rural areas more or less permanently until the fall of the empire.53

At first the Western powers took a neutral stance in the conflict. One reason for this was that the rebel leader compared himself with Christ and professed to be on a messianic mission, which won him sympathy in some Christian countries, especially the United States, where the public had a hard time understanding why the United States should support the Qing emperor (who was portrayed as reluctant to open his country to Christian missionaries). In Europe, some socialists and radical republicans saw the rebellion as a sort of Chinese equivalent of the French Revolution, but this view was less influential than the messianic image in the United States. But once the rebels began to challenge property rights and not only threaten trade disruptions but also halt China’s repayment of its debts to the West (which the French and British had imposed after sacking Beijing in 1860), the European powers decided to take the side of the Qing government. Their support was probably decisive in the ultimate victory of imperial forces over the rebels in 1862–1864, right in the middle of the US Civil War (which in any case facilitated the European intervention, since American Christians were preoccupied by events at home).54 If the rebels had triumphed, it is very hard to say how China’s political structure and borders might have evolved.

By the end of the nineteenth century, the moral legitimacy of the Qing dynasty and China’s warrior and mandarin elites had fallen very low in the eyes of the Chinese public. The country had been forced to accept a series of “unequal treaties” with the Europeans powers and found itself obliged to increase taxes sharply to repay the Westerners and their bankers what was effectively a military tribute, together with the accumulated interest.55 In such a context, the 1895 defeat of China by Japan (which for millennia had been dominated militarily and culturally by China), together with Japanese incursions into Korea and Taiwan, appeared to signal the end of the road for the Qing.