{ SEVEN }

Colonial Societies: Diversity and Domination

In the previous chapter we looked at slave societies and the manner of their disappearance, particularly in the Atlantic and Euro-American space. This allowed us to observe some surprising facets of the quasi-sacralized private property regime characteristic of the nineteenth century. We saw why it was necessary to indemnify slaveowners but not slaves when slavery was abolished. And we discovered that in Haiti, freed slaves were required to pay a heavy tribute to their former owners as the price of their freedom—a tribute that continued until the middle of the twentieth century. We also analyzed how the American Civil War and the end of slavery in the United States led to the development of a specific system of political parties and ideological cleavages, with important consequences for the subsequent evolution and current structure of inequality and political conflict not only in the United States but also in Europe and in other parts of the world.

We turn now to forms of domination and inequality that were less extreme than slavery but encompassed far vaster regions of the planet under the aegis of Europe’s colonial empires, which survived until the 1960s, with far-reaching consequences for today’s world. Recent research has shed light on the extent of socioeconomic inequality in both colonial and contemporary societies, and that is where we begin. We will then review the various factors that explain the very high levels of inequality observed in the colonial world. The colonies were to a very large extent organized for the sole benefit of the colonizers, especially regarding social and educational investment. Inequalities of legal status were quite pronounced and involved various forms of forced labor. All of this was shaped—in contrast to slave societies—by an ideology based on concepts of intellectual and civilizational domination in addition to military and extractive domination. Furthermore, the end of colonialism was accompanied, as we will see, by debates about possible regional and transcontinental forms of democratic federalism. With the perspective afforded us by the passage of time, we can see that these debates are rich in lessons for the future, even if they have yet to bear fruit.

The Two Ages of European Colonialism

This is obviously not the place to put forward a general history of the various forms of colonial society, which would far exceed the scope of this book. More modestly, my objective is to situate colonial societies in the broader history of inequality regimes and to bring out those aspects that are most important for the analysis of the subsequent evolution of inequality.

Broadly speaking, it is common to distinguish between two eras of European colonization. The first begins around 1500 with the “discovery” of the Americas and of maritime routes from Europe to India and China and ends in the period 1800–1850, specifically with the gradual extinction of the Atlantic slave trade and the abolition of slavery. The second begins in the period 1800–1850, reaches a peak between 1900 and 1940, and ends with the former colonies’ achievement of independence in the 1960s (or even the 1990s if one includes the special case of South Africa and the end of apartheid as an instance of colonialism).

To simplify, the first age of European colonization, between 1500 and 1800–1850, was based on a logic that is today widely recognized as military and extractive. It relied on violent military domination and forced displacement and/or extermination of populations, in particular in the form of the triangular trade and the development of slave societies in the French and British West Indies, the Indian Ocean, Brazil, and North America, as well as with the Spanish conquest of Central and South America.

The second colonial age, from 1800–1850 until 1960, is often said to have been kinder and gentler, especially by the former colonial powers who like to insist on the intellectual and civilizational aspects of the second phase of colonial domination. Although the differences between the two phases are significant, it is important to note that violence was scarcely absent from the second phase and that elements of continuity between the two eras are quite apparent. In particular, as we saw in the previous chapter, the abolition of slavery did not happen all at once but took most of the nineteenth century. Furthermore, slavery was supplanted by various forms of forced labor, which as we will see continued until the middle of the twentieth century, especially in the French colonies. We will also discover that, in terms of concentration of economic resources, postslave colonial societies figure among the most inegalitarian societies history has ever known, not far behind slave societies despite real differences of degree.

It is also common to distinguish between colonies with a significant population of European origin and colonies in which the European settler population was quite small. In the slave societies of the first colonial era (1500–1850), the proportion of slaves reached its highest levels in the French and British West Indies in the 1780s, with slaves accounting for more than 80 percent of the population of the islands and as much as 90 percent in Saint-Domingue (Haiti)—the highest concentration of slaves anywhere in the period and also the site of the first victorious slave rebellion in 1791–1793. Nevertheless, the proportion of Europeans in the West Indies in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries was close to or above 10 percent, which is a lot compared with most other colonial societies. Slavery rested on total and complete domination of the slave population, which required a significant proportion of colonizers in the population. In the other slave societies that we studied in Chapter 6 and that proved more durable, the proportion of Europeans was even higher—two-thirds on average (compared to one-third slaves) in the southern United States with a minimum just above 40 percent whites (compared to 60 percent slaves) in South Carolina and Mississippi in the 1850s. In Brazil, the slave population was close to 50 percent in the eighteenth century and fell to around 20–30 percent in the second half of the nineteenth century (see Figs. 6.1–6.4).

In both the North American and “Latin” American cases, however, it is important to note that the question of European settlement raises two further issues: the brutal treatment of the native population and interbreeding.1 In Mexico, for example, it has been estimated that the indigenous population in 1520 was between 15 and 20 million; as a result of military conquest, political chaos, and disease introduced by the Spaniards, the population fell to less than 2 million by 1600. Meanwhile, interbreeding among the indigenous and European populations as well as African populations grew rapidly, accounting for a quarter of the population by 1650, a third to a half by 1820, and nearly two-thirds in 1920. In the regions now occupied by the United States and Canada, the Amerindian population when Europeans first arrived has been estimated at 5 to 10 million before falling to less than a half million in 1900, by which time the population of European descent exceeded 70 million, so that the latter became ultra-dominant without significant interbreeding with either the indigenous or African populations.2

If we now turn to the empires of the second colonial era (1850–1960), the norm is that the European population was generally quite small or even minuscule, but again there was a great deal of diversity. Note first that European colonial empires in the period 1850–1960 attained much larger transcontinental dimensions than in the first colonial era—indeed, dimensions that were unrivaled in the entire history of humanity. At its peak in 1938, the British colonial empire encompassed a total population of 450 million, including more than 300 million in India (which is a veritable continent unto itself, and about which I will have more to say in Chapter 8); at the time, the metropolitan population of the United Kingdom itself was barely 45 million. The French colonial empire, which reached its zenith at the same moment, numbered around 95 million (including 22 million in North Africa, 35 million in Indochina, 34 million in French West and Equatorial Africa, and 5 million in Madagascar), compared with a little over 40 million in metropolitan France. The Dutch colonial empire comprised roughly 70 million people, mostly in Indonesia, at a time when the population of the Netherlands was barely 8 million. Bear in mind that the political, legal, and military ties that defined the borders of these various empires were highly diverse, as were the conditions under which censuses were conducted, so that the figures cited should be taken as approximate and valid only as indicators of orders of magnitude.3

Settler Colonies, Colonies Without Settlement

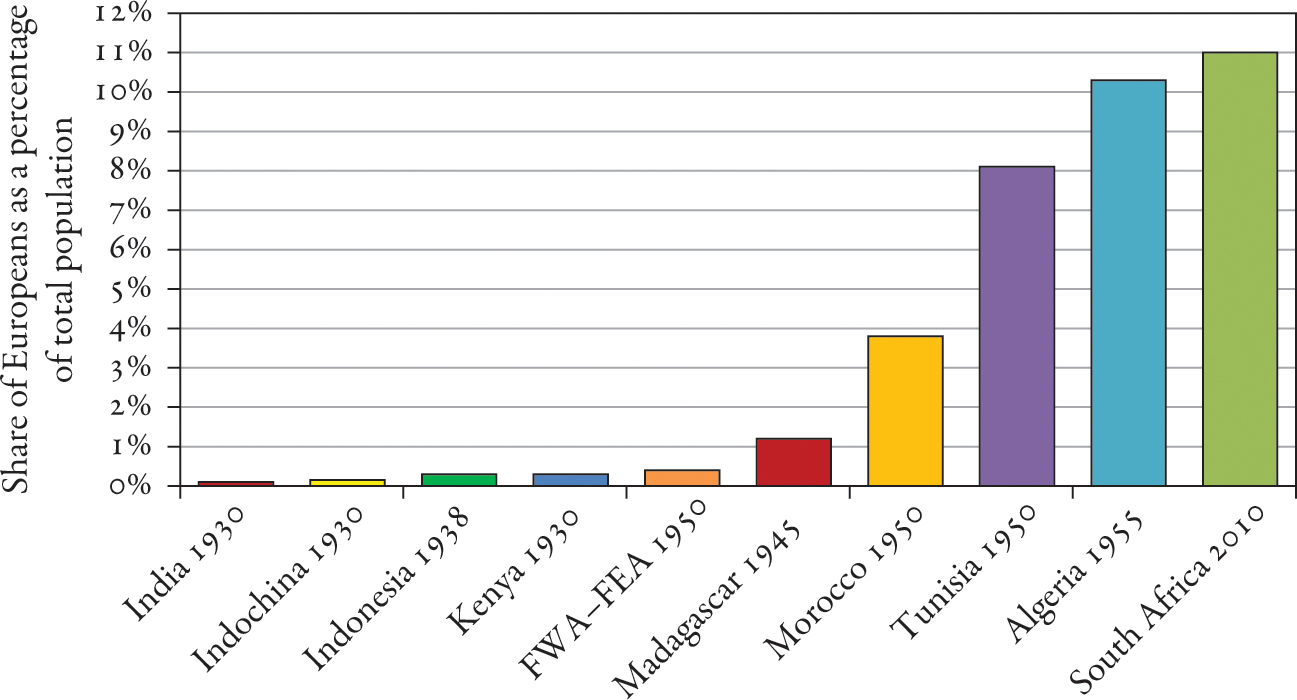

In most cases European settlement in these vast empires was quite limited. In the interwar years, the European (and mostly British) population of the vast British Raj never exceeded 200,000 (of whom 100,000 were British soldiers) or less than 0.1 percent of the total population of India (more than 300 million). These figures quite eloquently tell us that the type of domination that existed in India had little to do with that which existed in Saint-Domingue. In India, domination was of course based on military superiority, which was demonstrated in undeniable fashion in a number of decisive confrontations, but more than that, it rested on an extremely sophisticated form of political, administrative, police, and ideological organization as well as on numerous local elites and multiple decentralized power structures, all of which led to a kind of consent and acquiescence. Thanks to this organization and ideological domination, with a tiny population of colonizers the British were able to break the resistance and organizational capacity of the colonized—at least up to a point. This order of magnitude—a European settler population of 0.1–0.5 percent—is in fact fairly representative of many regions in the second colonial era (Fig. 7.1). For instance, in French Indochina in the interwar years and into the era of decolonization in the 1950s, the proportion of Europeans in French Indochina was barely 0.1 percent. In the Dutch East Indies (today Indonesia), the European population reached 0.3 percent in the interwar years, and we find similar levels in the same period in British colonies in Africa, such as Kenya and Ghana. In French West Africa (FWA) and French Equatorial Africa (FEA), the European population was about 0.4 percent in the 1950s. In Madagascar, the European population reached a comparatively impressive 1.2 percent in 1945 on the eve of the violent clashes that would lead to independence.

Among the rare examples of authentic settler colonies, one must mention the case of French North Africa, which, along with Boer and British South Africa, offers one of the few examples in colonial history of a confrontation between a significant European minority (roughly 10 percent of the total population) and an indigenous majority (of roughly 90 percent): there, domination was extremely violent and interbreeding virtually nonexistent. This pattern was quite different from what we see in British settler colonies (the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand), where the indigenous population plummeted after the arrival of the Europeans (and there was almost no interbreeding), as well as Latin America, where there was a great deal of interbreeding between the native and European populations, especially in Mexico and Brazil.

In the 1950s, the European population, essentially of French origin but with Italian and Spanish minorities, accounted for nearly 4 percent of the total population in Morocco, 8 percent in Tunisia, and more than 10 percent in Algeria. In the Algerian case, European settlers numbered about 1 million on the eve of the war for independence out of a total population of barely 10 million. It was, moreover, a European population of fairly long standing, since the French colonization of Algeria began in 1830; the settler population began to grow quite rapidly in the 1870s. In the census of 1906, the European share of the population exceeded 13 percent and rose as high as 14 percent in 1936 before falling sharply to 10–11 percent in the 1950s owing to even more rapid growth of the indigenous Muslim population. The French were particularly well represented in the cities. In the 1954 census, there were 280,000 Europeans in Algiers compared with 290,000 Muslims for a total of 570,000. Oran, the second largest city in the country, had a population of 310,000, of whom 180,000 were European and 130,000 Muslim. The French colonizers, certain of their own righteousness, rejected independence for a country they regarded as their own.

FIG. 7.1. The proportion of Europeans in colonial societies

Interpretation: The proportion of the population of European origin in colonial society between 1930 and 1955 was 0.1–0.3 percent in India, Indochina, and Indonesia, 0.3–0.4 percent in Kenya and French West Africa (FWA), 1.2 percent in Madagascar, nearly 4 percent in Morocco, 8 percent in Tunisia, 10 percent in Algeria in 1955 (13 percent in 1906, 14 percent in 1931). The proportion of whites in South Africa was 11 percent in 2010 (and between 15 and 20 percent from 1910 to 1990). Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

Against all probability the French political class insisted that France would hold on to this particular colony (“Algeria is France”), but the settlers were wary of the government in Paris, which they suspected, not without reason, of being prepared to abandon the country to the independence forces. In 1958 French generals in Algeria attempted a putsch, which might have ended in an autonomous Algerian colony under the control of the settlers. But the events in Algeria in fact led to General Charles de Gaulle’s return to power in Paris, and the general was soon left with no choice but to put an end to the brutal war and accept Algerian independence in 1962. It is natural to compare these events with what happened in South Africa, where, after the end of British colonization, the white minority managed to hold on to power from 1946 until 1994 under the apartheid regime, about which I will say more later. The white minority in South Africa represented 15–20 percent of the population; by 2010 this had fallen to 11 percent (Fig. 7.1), owing to white departures and the rapid increase of the black population. This is a level quite close to that of French Algeria, and it is interesting to compare the level of inequality observed in both cases given the many differences and similarities between the two colonial systems.

Slave and Colonial Societies: Extreme Inequality

What can we say about the extent of socioeconomic inequality in slave and colonial societies, and what comparisons can be made with inequality today? Unsurprisingly, slave and colonial societies rank among the most inegalitarian ever observed. Nevertheless, the orders of magnitude and their variation in time in space are interesting in themselves and deserve to be examined closely.

The most extreme case of inequality for which we have evidence is that of the French and British slave islands in the late eighteenth century. Let’s begin with Saint-Domingue in the 1780s, when slaves represented 90 percent of the population. Recent research allows us to estimate that the wealthiest 10 percent of the island’s population—slaveowners (including some who resided partially or totally in France), white settlers, and a small mixed-race minority—appropriated roughly 80 percent of the wealth produced in Saint-Domingue every year, whereas the poorest 90 percent, which is to say the slaves, received (in the form of food and clothing) the equivalent in monetary value of barely 20 percent of annual production—more or less the subsistence level. Note that this estimate was carried out in such a way as to minimize inequality. It is possible that the share going to the top decile was in fact greater than 80 percent of the wealth produced, perhaps as high as 85–90 percent.4 In any case, it could not have been much higher owing to the subsistence constraint. In other slave societies in the West Indies and Indian Ocean, where slaves generally represented 80–90 percent of the population, all available evidence suggests that the distribution of the wealth produced was not much different. In slave societies where the proportion of slaves was smaller, such as Brazil and the southern United States (30–50 percent, or as high as 60 percent in a few states), inequality was less extreme, with the top decile claiming an estimated 60–70 percent of annual income depending on the extent of inequality in the free white population.

Other recent research provides data for comparison with nonslave colonial societies. The available statistics are limited, primarily because tax systems in the colonies relied for the most part on indirect taxation. There were, however, some British and to a lesser extent French colonies in the first half of the twentieth century in which the competent authorities (governors and administrators theoretically under the supervision of the colonial ministry and the metropolitan government but in practice allowed a certain autonomy in circumstances that varied widely) applied progressive direct income taxes similar to those levied in the metropole. Statistics derived from those taxes have survived, especially for the interwar years and the period just before independence. Facundo Alvaredo and Denis Cogneau have worked on such data from the French colonial archives, while Anthony Atkinson has done the same with data from the British and South African colonial archives.5

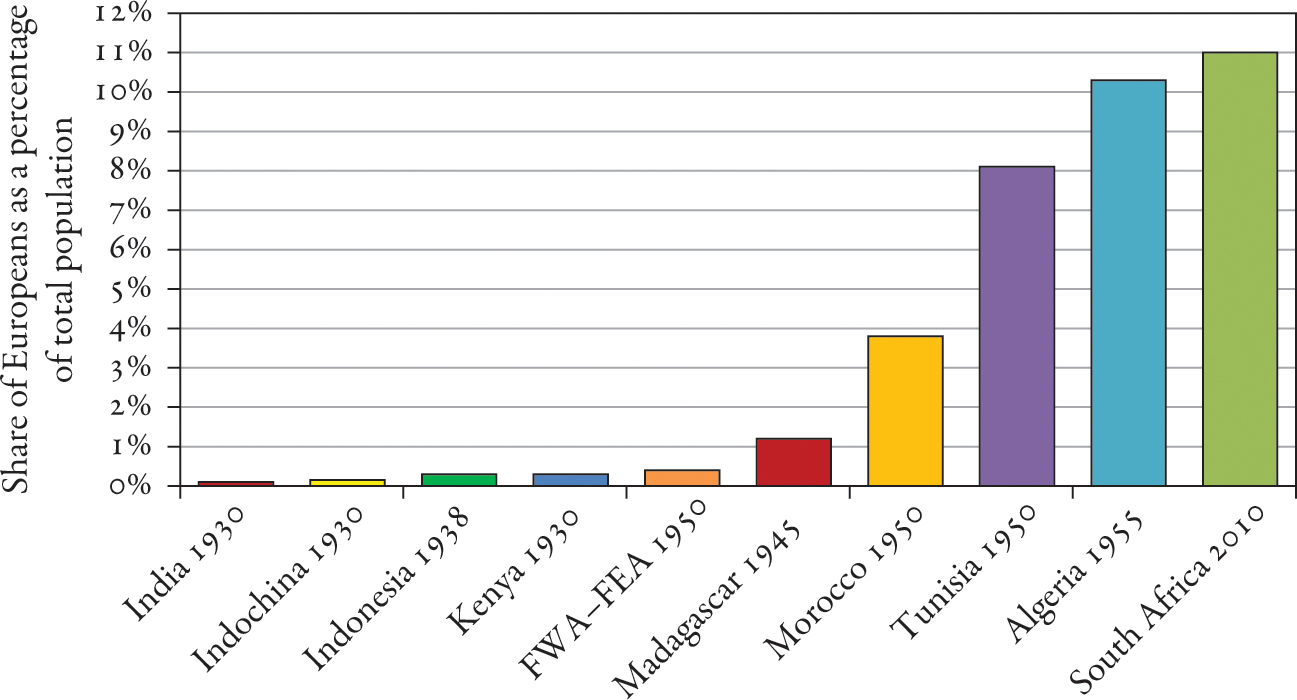

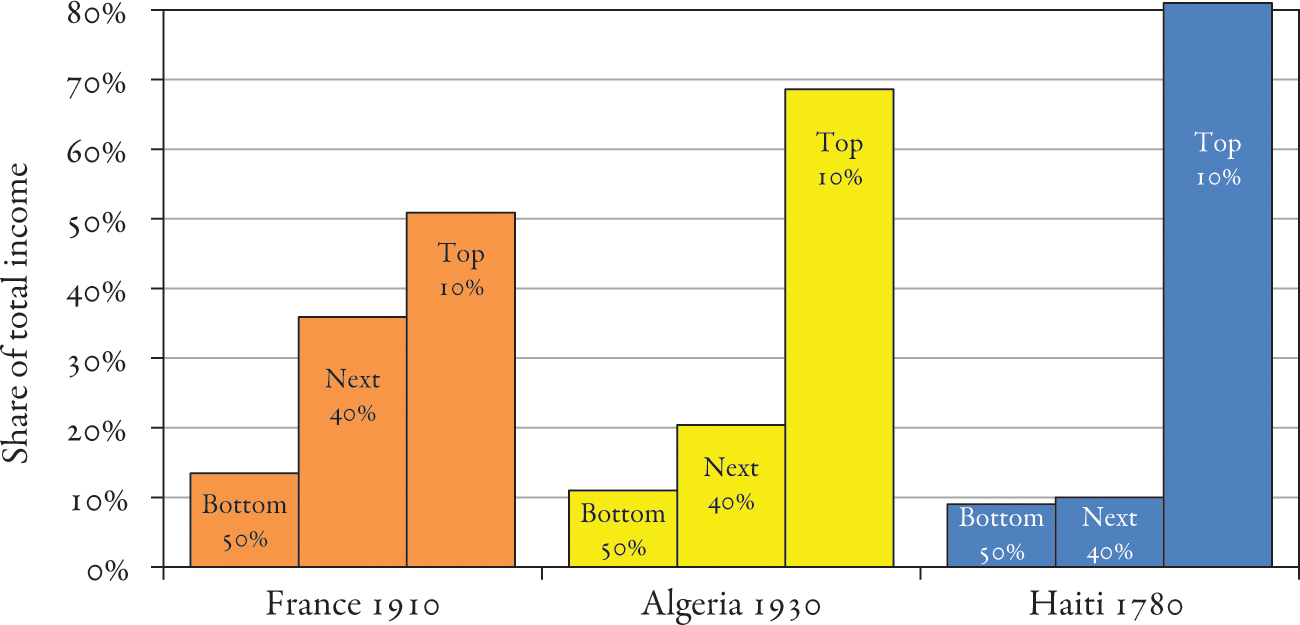

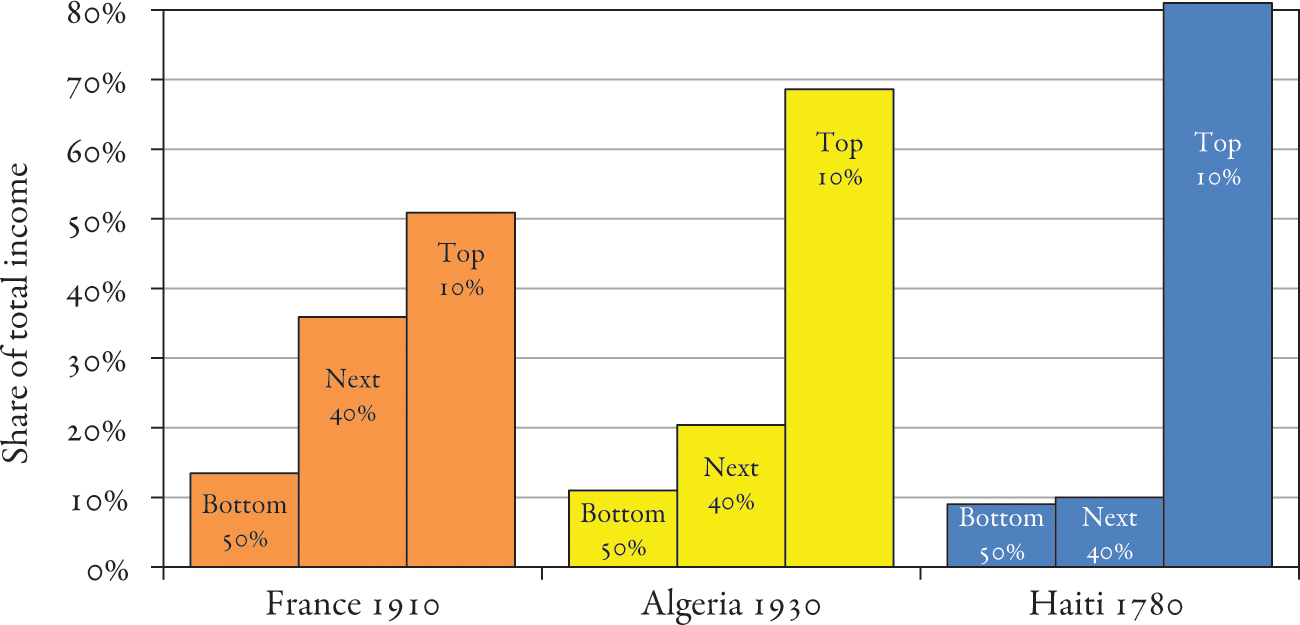

In regard to Algeria, the available data allow us to estimate that the top decile’s share was close to 70 percent of total income in 1930—hence a lower level of inequality than in Saint-Domingue in 1780 but significantly higher than in metropolitan France in 1910 (Fig. 7.2). Of course, this does not mean that the situation of the poorest 90 percent in colonial Algeria (essentially the Muslim population) was in any way close or comparable to that of the slaves of Saint-Domingue. Among the crucial dimensions of social inequality are some that radically distinguish one inequality regime from another, starting with the right to mobility, the right to a private and family life, and the right to own property. Nevertheless, from the standpoint of distribution of material resources, colonial Algeria in 1930 was in an intermediate position between proprietarian France in 1910 and Saint-Domingue in 1780, perhaps a little closer to the latter than the former (although the lack of precision in the available data makes it difficult to be certain about this).

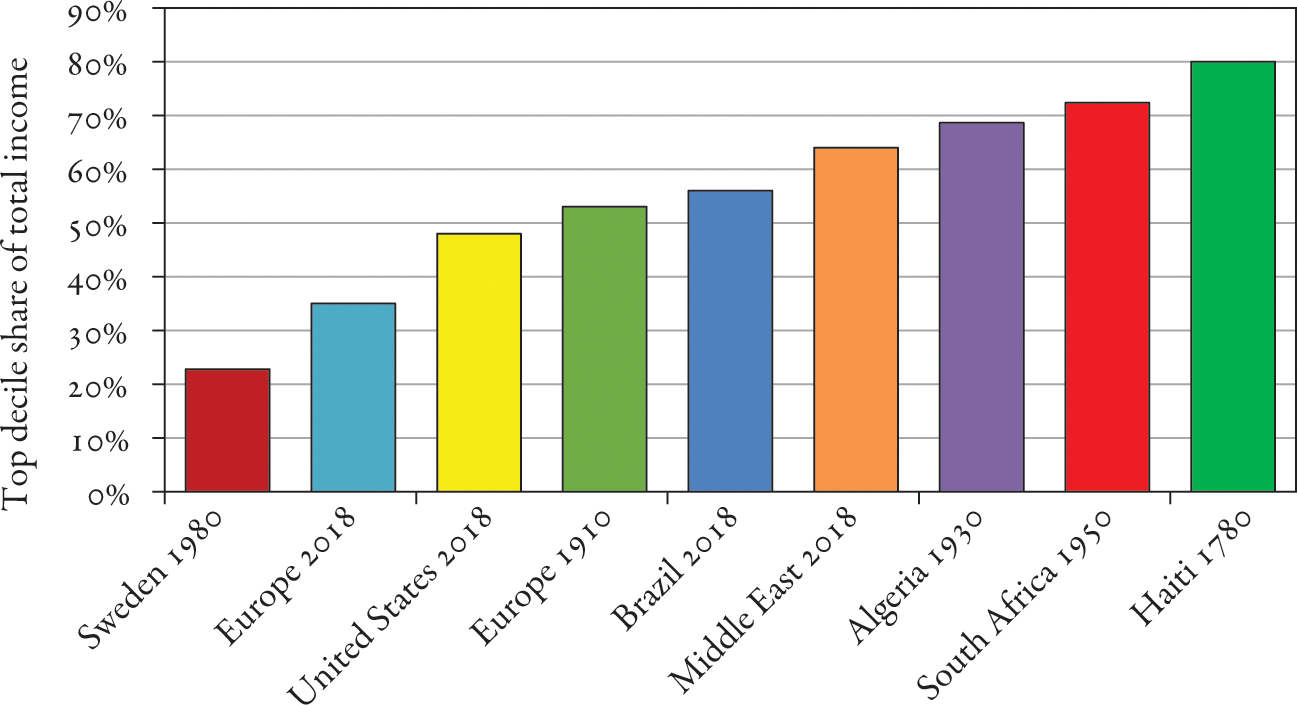

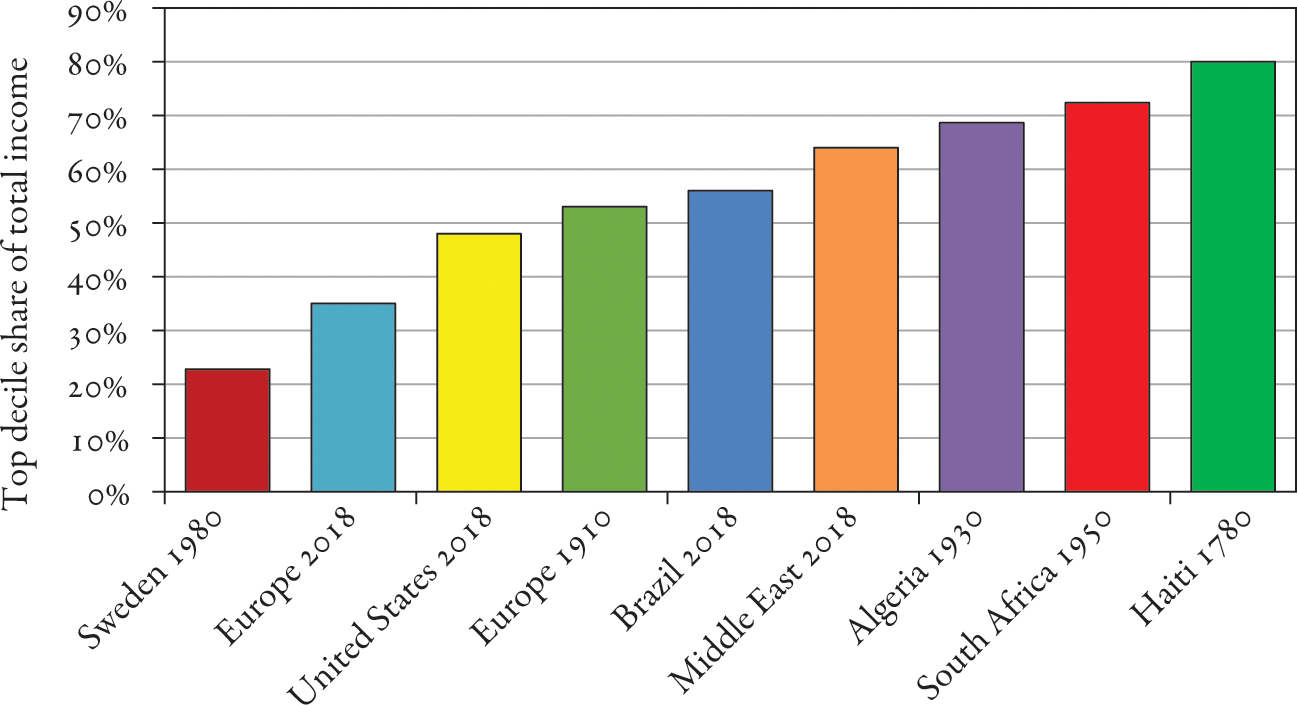

FIG. 7.2. Inequality in colonial and slave societies

Interpretation: The top 10 percent of earners received more than 80 percent of total income in Saint-Domingue (Haiti) in 1780 (where the population was 90 percent slaves and 10 percent Europeans, compared with 70 percent in colonial Algeria in 1930 (90 percent natives and 10 percent European settlers), and around 50 percent in metropolitan France in 1910. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

If we now broaden our spatial and temporal view and compare the share of wealth produced in one year that was appropriated by the wealthiest 10 percent, we find that slave societies such as Saint-Domingue in 1780 were the most inegalitarian in all of history, followed by colonial societies such as South Africa in 1950 and Algeria in 1930. Social-democratic Sweden around 1980 was one of the most egalitarian ever seen in terms of income distribution, so we can begin to make some judgments about the variety of possible situations. In Sweden, the top decile’s share of total income was less than 25 percent, compared with 35 percent for Western Europe and around 50 percent for the United States in 2018; and for proprietarian Europe in the Belle Époque, the top decile’s share of total income was around 55 percent for Brazil in 2018, 65 percent for the Middle East in 2018, roughly 70 percent for colonial Algeria in 1950 or South Africa in 1950, and 80 percent for Saint-Domingue (Fig. 7.3).

FIG. 7.3. Extreme inequality in historical perspective

Interpretation: Among the countries observed, the top decile’s share of income ranged from 23 percent in Sweden in 1980 to 81 percent in Saint-Domingue (Haiti) in 1780 (where the population was 90 percent slaves). Colonial societies such as Algeria and South Africa in the period 1930–1950 rank among the most unequal societies in history, with about 70 percent of income going to the top decile, which included the European population. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

If we look now at the share of the top centile (the wealthiest 1 percent), which enables us to include a larger number of colonial societies in the comparison (especially those with limited European populations, for which the available sources generally do not allow us to estimate the total income of the top decile), the terms of comparison are slightly different (Fig. 7.4). We find that some colonial societies stand out for an exceptionally high level of inequality at the peak of the distribution. Southern Africa is a case in point: the top centile’s share was 30–35 percent in South Africa and Zimbabwe in the 1950s and more than 35 percent in Zambia. These were countries in which tiny white elites exploited vast landed estates or derived significant profits from other sectors such as mining. Furthermore, the top thousandth or ten-thousandth claimed an exceptionally large share. This was true to a slightly lesser extent in French Indochina. There, the top centile’s share approached 30 percent, reflecting the very good pay of the colonial administrative elite as well as very high income and profits in sectors such as rubber (although the available data do not allow for a detailed breakdown). By contrast, in other colonial societies, we find that although the top centile’s share was quite high (for example, 25 percent in Algeria, Cameroon, and Tanzania in the period 1930–1950), this was not very different from the levels observed in Belle Époque Europe or in the United States today, and it was distinctly lower than the levels seen today in Brazil and the Middle East (roughly 30 percent). As far as the top centile’s share is concerned, all of these different societies are ultimately fairly similar, especially when compared to social-democratic Sweden in 1980 (with a top centile share below 5 percent) or Europe in 2018 (around 10 percent).

FIG. 7.4. The top centile in historical and colonial perspective

Interpretation: Of all societies observed (except slave societies) the top centile’s share of income varied from 4 percent in Sweden in 1980 to 36 percent in Zambia in 1950. Colonial societies rank among the most inegalitarian ever seen. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

In other words, the summit of the income hierarchy (the wealthiest 1 percent and beyond) was not always all that elevated in colonial societies, at least when compared with very inegalitarian contemporary societies. Take colonial Algeria, for instance: the top centile’s position relative to the average Algerian income at the time was not much higher than the top centile’s position in metropolitan France compared with the average metropolitan income in the Belle Époque. Indeed, in strict standard-of-living terms, the top centile in Algeria was markedly inferior to the top metropolitan centile. By contrast, if one considers the top decile overall, then its distance from the rest of society was noticeably smaller in colonial Algeria than in France in 1910 (Figs. 7.2–7.3). In fact, there are some societies in which a tiny elite of owners (roughly 1 percent of the population) stands apart from the rest of society by virtue of its wealth and lifestyle and other societies in which a broad colonial elite (roughly 10 percent of the population) differentiates itself from the indigenous masses. These parameters define very distinct inequality regimes and systems of power and domination, each with its own specific modes of conflict resolution.

More generally, it was not always the size of the income gap that differentiated colonial inequality from other inequality regimes but rather the identity of the victors—in other words, the fact that colonizers occupied the top of the hierarchy. Colonial tax archives do not always give a clear picture of the respective shares of colonizers and natives in different income tranches. Wherever the sources speak clearly, however—whether in North Africa, Cameroon, Indochina, or South Africa—the results are unambiguous. Although the European population was always a small minority, it always accounted for the vast majority of those with the highest incomes. In South Africa, where fiscal records in the apartheid period were tabulated separately by race, we find that whites always accounted for more than 98 percent of the taxpayers in the top centile. The other 2 percent were Asian (mostly Indian), not blacks, who accounted for less than 0.1 percent of the top earners. In Algeria and Tunisia, the data are not perfectly comparable, but the available indicators show that Europeans generally accounted for 80–95 percent of the top earners.6 This was certainly not as small a percentage as in South Africa, but it nevertheless indicates that the economic domination of the colonizers was virtually absolute.

As for the comparison between Algeria and South Africa, it is interesting to note that Algeria is less inegalitarian in terms of the income distribution, but the difference is relatively small, especially if one looks at the top decile (Figs. 7.3–7.4). The white hyper-elite (top centile or thousandth) was certainly less prosperous in Algeria than in South Africa, but from the standpoint of the top decile the two countries were probably not so far apart. In both cases there was considerable distance between the white colonizers and the rest of the population. To be sure, the concentration of income seems to have decreased in Algeria between 1930 and 1950 as well as in South Africa between 1950 and 1990, but in both countries it remained extremely high (Fig. 7.5).

FIG. 7.5. Extreme inequality: Colonial and postcolonial trajectories

Interpretation: The top decile’s share decreased in colonial Algeria between 1930 and 1950 and in South Africa between 1950 and 2018, while remaining at a level that ranks among the highest in history. In French overseas départements like Réunion and Martinique, income inequality has decreased significantly, while remaining higher than in metropolitan France. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

It is also striking that the top decile’s share has increased in South Africa since the end of apartheid (we will come back to this point). Note, too, that the former French slave islands Réunion, Martinique, and Guadeloupe, which became French départements in 1946 (a century after the abolition of slavery in 1848), have remained extremely unequal in terms of income distribution. Consider Réunion, for example: fiscal archives recently studied by Yajna Govind show that the top decile’s share of total income exceeded 65 percent in 1960 and was still above 60 percent in 1986—levels close to those observed in colonial Algeria and South Africa—before dropping to 43 percent in 2018, which is still much higher than in metropolitan France. The persistence of such a high level of inequality is explained in part by inadequate investment and by the existence of government officials who are very highly paid, at least by local standards, and who in many cases come from France.7

Maximal Inequality of Property, Maximal Inequality of Income

Before analyzing the roots of colonial inequalities and the reasons for their persistence, it will be useful to clarify the following point. When we discuss the issue of “extreme” inequality, we need to distinguish between the distribution of property and the distribution of income. In regard to inequality of property, by which I mean the distribution of goods and assets of all kinds that one is allowed to own under the existing legal regime, it is fairly common to observe an extremely strong concentration, with nearly all wealth owned by the wealthiest 10 percent or even the wealthiest 1 percent and virtually no property ownership by the poorest 50 or even 90 percent. In particular, as we saw in Part One, the ownership societies that flourished in Europe in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were characterized by extreme concentration of property. In France, the United Kingdom, and Sweden during the Belle Époque (1880–1914), the wealthiest 10 percent owned 80–90 percent of what there was to own (land, buildings, equipment, and financial assets, net of debt), and the wealthiest 1 percent alone owned 60–70 percent.8 Extreme inequality of ownership can certainly pose political and ideological problems but raises no difficulty from a strictly material point of view. Strictly speaking, one can imagine societies in which the wealthiest 10 or 1 percent own 100 percent of all wealth. And that is not the end of it: large classes of the population can have negative wealth if their debts outweigh their assets. In slave societies, for example, slaves owe all their working time to their owners. The owning classes can therefore own more than 100 percent of the wealth because they own both goods and people. Inequality of wealth is above all inequality of power in society, and in theory it has no limit, to the extent that the owner-established apparatus of repression or persuasion (as the case may be) is able to hold society together and perpetuate this equilibrium.9

Income inequality is different. It refers to the distribution of the flow of wealth that takes place each year, a flow that is necessarily constrained to respect the subsistence of the poorest members of society, for otherwise a substantial segment of the population would die in short order. It is possible to live without owning anything but not without eating. Concretely, in a very poor society, where the output per person is just at the subsistence level, no lasting income inequality is possible. Everyone must receive the same (subsistence) income, so that the top decile’s share of total income would be 10 percent (and the top centile’s share 1 percent). By contrast, the richer a society is, the more it becomes materially possible to sustain a very high level of income inequality. For example, if output per person is on the order of one hundred times the subsistence level, it is theoretically possible for the top centile to take 99 percent of the wealth produced while the rest of the population remains at subsistence level. More generally, it is easy to show that the maximal materially possible level of inequality in any society increases with that society’s average standard of living (Fig. 7.6).10

The notion of maximal inequality is useful because it helps us to understand why income inequality can never be as extreme as property inequality. In practice, the share of total income going to the poorest 50 percent is always at least 5–10 percent (and generally on the order of 10–20 percent), whereas the share of property owned by the poorest 50 percent can be close to zero (often barely 1–2 percent or even negative). Similarly, the share of total income going to the wealthiest 10 percent is generally no more than 50–60 percent, even in the most inegalitarian societies (with the exception of a few slave and colonial societies of the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries, in which this share rose as high as 70–80 percent), whereas the share of property owned by the wealthiest 10 percent regularly reaches 80–90 percent, especially in the proprietarian societies of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and it could rapidly regain such levels in the neo-proprietarian societies in full flower today.

FIG. 7.6. Subsistence income and maximal inequality

Interpretation: In a society where the average income is three times the subsistence income, the maximal share of the top income decile (comparable with a subsistence income for the bottom 90 percent) is equal to 70 percent of total income, and the maximal share of the top centile (compatible with subsistence income for the bottom 99 percent) is 67 percent. The richer a society is, the higher the level of inequality it can achieve. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

The “material” determinants of inequality should not be exaggerated, however. In reality, history teaches us that what determines the level of inequality is above all society’s ideological, political, and institutional capacity to justify and structure inequality and not the level of wealth or development as such. “Subsistence income” is itself a complex idea and not just a simple reflection of biological reality. It depends on representations fashioned by each society and is always a concept with many dimensions (such as food, clothing, housing, hygiene, and so on), which cannot be correctly measured by a single monetary index. In the late 2010s, it was common to situate the subsistence threshold at 1–2 euros per day; extreme poverty was measured at the global level as the number of people living on less than 1 euro per day. Available estimates show that per capita national income was less than 100 euros per month in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries (compared with 1,000 euros per month in 2020, with both amounts expressed in 2020 euros). This implies that a substantial fraction of the population was living not far above the subsistence level in the eighteenth century, a conclusion confirmed by the very high mortality rates and very short life expectancies observed for all age groups, but it also suggests that there was some room for maneuver, and hence that several different inequality regimes were possible.11 More specifically, in Saint-Domingue, a prosperous island thanks to its production of sugar and cotton, the market value of output per capita was on the order of two or three times higher than the global average at the time, so that it was easy from a strict material point of view to extract a maximal level of profit. If a society’s average per capita income exceeds four to five times the subsistence level, that is enough, moreover, for maximal inequality to reach extreme levels, where the top decile or centile can claim as much as 80–90 percent of total income (Fig. 7.6).

In other words, although it is indeed difficult for an extremely poor society to develop an extremely hierarchical inequality regime, a society does not have to be very rich to attain a very high level of inequality. Specifically, in strictly material terms, quite a number—perhaps most—societies that have existed since antiquity could have chosen extreme levels of inequality, comparable with those observed in Saint-Domingue, and today’s wealthy societies could go even further (and some may do so in the future).12 Inequality is determined primarily by ideological and political factors, not by economic or technological constraints. Why did slave and colonial societies attain such exceptionally high levels of inequality? Because they were constructed around specific political and ideological projects and relied on specific power relations and legal and institutional systems. The same is true of ownership societies, trifunctional societies, social-democratic and communist societies, and indeed of human societies in general.

Note, moreover, that while history has given us examples of societies that come close to the maximal level of income inequality in terms of the top decile’s share (around 70–80 percent of total income in the most inegalitarian colonial and slave societies and 60–70 percent in today’s most inegalitarian societies, especially in the Middle East and South Africa), the story of the top centile is different. There, the highest top centile shares amount to 20–35 percent of total income (Fig. 7.4), which is of course quite a high level but still quite a bit below the 70–80 percent of annual output that the top centile could in theory appropriate once average national income exceeds three to four times the subsistence level (Fig. 7.6). No doubt the explanation for this has to do with the fact that it is no simple matter to build an ideology along with institutions that would allow such a narrow group, just 1 percent of the population, to persuade the rest of society to cede control of nearly all newly produced resources. Maybe a handful of particularly imaginative techno-billionaires will be able to do so in the future, but to date no elite has managed such a feat. In the case of Saint-Domingue, which represents the absolute height of inequality in this study, we estimate that the top centile’s share attained, at a minimum, 55 percent of the annual wealth produced, coming quite close to the theoretical maximum (Fig. 7.7). I must stress, however, that this calculation is somewhat contrived in that it includes among the top centile slaveowners who were in fact residing primarily in France rather than Saint-Domingue and who enriched themselves on the sales of goods exported from the island.13 Perhaps this strategy of putting some distance between the top centile and the rest is in general a good way of making inequality more bearable than when it involves cohabitation in the same society. In the case of Saint-Domingue, however, it was not enough to prevent eventual revolt and expropriation.

FIG. 7.7. The top centile in historical perspective (with Haiti)

Interpretation: If one includes slave societies such as Saint-Domingue (Haiti) in 1780, then the top centile share can go as high as 50–60 percent of total income. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

Colonization for the Colonizers: Colonial Budgets

We turn now to the question of the origins and persistence of colonial inequalities. Among the justifications of the inequalities associated with slavery, we saw in Chapter 6 that economic and commercial competition among rival state powers ranked high, along with denunciation of the hypocrisies of industrial inequality. These arguments also play a role in justifying postslavery colonial domination, but for the colonizers the main justification was always to insist on their mission civilisatrice (to use the standard French phrase, which translates into English as “civilizing mission”). From the standpoint of the colonizers, that mission depended first on keeping order and promoting a proprietarian (and potentially universal) model of development and second on a form of domination that saw itself as intellectual and founded on the diffusion of science and learning.14 It is therefore interesting to study how the colonies were organized concretely, particularly with respect to their budgets, taxes, and legal and social systems; more generally, it will be helpful to examine the various development models that colonizers put in place. Unfortunately, research on these topics is limited, but enough is known to draw some preliminary conclusions.

Broadly speaking, an abundance of evidence shows that colonies were organized primarily for the benefit of the colonizers and the metropole and that any investment in social and educational improvements for the benefit of the indigenous population was extremely limited, not to say nonexistent. We find the same low levels of investment in France’s so-called overseas territories, particularly in the West Indies and Indian Ocean, which have remained attached to France to this day; this may help to explain the persistence of glaring inequalities both within these territories and between them and metropolitan France. For example, French parliamentary reports from the 1920s and 1930s noted extremely low rates of schooling in Martinique and Guadeloupe and, more generally, the “lamentable” state of the school systems on both islands.15 The situation gradually improved in both territories after they became départements in 1946; it also improved to a lesser extent in other French colonies in the 1950s, when the metropole was still hoping to hold on to pieces of its empire. But the accumulated lag was significant, and it would take half a century for the overseas départements to reduce inequalities to anything close to metropolitan levels (Fig. 7.5).

Recent work, especially that of Denis Cogneau, Yannick Dupraz, Elise Huilery, and Sandrine Mesplé-Somps, has given us a better understanding of colonial budgets in North Africa, Indochina, and the French West and Equatorial Africa and how they evolved in the late nineteenth and first half of the twentieth centuries.16 The general principle of French colonization, at least in the second colonial empire (that is, from 1850 to 1960 or so), was that the colonies should be self-sufficient in budgetary terms. In other words, taxes paid in each colony should suffice to finance expenditures in that colony, no more and no less. There should be no fiscal transfer from the colonies to France or from France to the colonies. And indeed, in formal terms, colonial budgets were balanced throughout the period of colonization. Taxes equaled expenditures, in particular in the Belle Époque (1880–1914) and in the interwar years (1918–1939), and more generally throughout the period 1850–1945. The only exception came in the period immediately prior to independence, which roughly coincides with the Fourth Republic (1946–1958), during which we find a modest fiscal transfer from France to the colonies.

It is important, however, to understand what “balanced” colonial budgets meant in the period 1850–1945. In practice, it meant that budgetary costs fell primarily on the colonized for the exclusive benefit of the colonizers. In terms of taxation, we find mainly regressive taxes, with higher rates on low incomes than on high incomes: consumption taxes, indirect taxes, and above all a capitation, or head tax, meaning a tax of a certain amount on each resident, whether rich or poor, without any consideration for the taxpayer’s ability to pay. This is the least sophisticated form of taxation imaginable, which Ancien Régime France had largely done away with in the eighteenth century, even before the Revolution. Furthermore, these colonial budgets make no mention of corvées, or days of forced labor that colonized people owed to the colonial administration, about which I will say more later.

It also bears emphasizing that the level of fiscal extraction was relatively high in view of the poverty of the societies in question. From the available data about output levels (including self-produced foodstuffs), we estimate that in 1925 taxes amounted to nearly 10 percent of GDP in North Africa and Madagascar and more than 12 percent in Indochina, which is almost as high as in the metropole at the same time (where 16 percent of GDP went to taxes), and more than in France from 1800 to 1914 (less than 10 percent) as well as many poor countries today.

Last but perhaps most important, on the expenditure side we find that colonial budgets were designed for the exclusive benefit of the French and European population, in particular to provide very comfortable salaries for the governor, high colonial administrators, and police. In short, the colonized populations paid heavy taxes to finance the luxurious lifestyles of the people who came to dominate them politically and militarily. There was also some investment in infrastructure as well as meager spending on education and health, but most of that was intended for the colonizers. Generally speaking, the number of public officials in the colonies, especially teachers and doctors, was quite small, but they were exceptionally well paid compared to the average local income. Looking at the budgets for all the French colonies in 1925, we find, for example, that there were barely two civil servants for every 1,000 residents, but each of them was paid at roughly ten times the average per capita income. By contrast, in metropolitan France at that time, there were roughly ten civil servants per 1,000 residents, and each was paid about twice the average per capita income.17

In some cases, colonial budgets recorded separately salaries paid to civil servants from the metropole and those recruited from the indigenous population. In Indochina and Madagascar, for example, we find that Europeans represented roughly 10 percent of civil servants but received more than 60 percent of total salaries. Sometimes it is also possible to distinguish the amounts spent on different populations, especially for education, because the school systems open to the children of colonizers were usually strictly segregated from those reserved for native children. In Morocco, primary and secondary schools reserved for Europeans received 79 percent of the total educational expenditure in 1925 (although they accounted for only 4 percent of the population). In the same period less than 5 percent of native children attended school in North Africa and Indochina and less than 2 percent in FWA. It is particularly striking to note that this glaring inequality does not seem to have improved in the final stages of colonization, despite the fact that the metropole had begun to invest more resources in the colonies. In Algeria, budget records show that schools reserved for colonizers received 78 percent of total expenditure on education in 1925 and 82 percent in 1955, even though the war for independence had already begun. The colonial system operated in such an inegalitarian manner that it appears to have been largely resistant to reform.

Of course, one should take into account the fact that all educational systems at the time were extremely elitist, including in the metropole. As we will see later, educational expenditure is still to this day quite unequally distributed in terms of both a child’s social origin and that child’s early educational success (the two criteria are correlated, but not completely). Lack of both transparency and reformist ambition in this area is one of the many challenges that must be faced by anyone who hopes to reduce inequality in the future, and no country is really in a position to give lessons on this subject. In any case, the degree of educational inequality in colonial societies seems to have been exceptionally high, much more so than elsewhere. Take the case of Algeria in the early 1950s: we estimate that the 10 percent of primary, secondary, and tertiary students who benefited the most from social expenditure on education in each age cohort (meaning, in practice, children of colonizers) received more than 80 percent of all monies spent on education (Fig. 7.8). If we carry out the same calculation for France in 1910, which was extremely stratified in terms of education in the sense that the lower classes rarely progressed beyond the primary level, we find that the top 10 percent in terms of educational expenditure received only 38 percent of the total monies spent, compared with 26 percent for the least educated 50 percent of each age cohort. This is still a significant level of educational inequality, given that the second group is by construction five times as large as the first. In other words, eight times as much money was spent on each child in the top 10 percent compared with each child in the bottom 50 percent. Inequality of educational expenditure decreased significantly in France between 1910 and 2018, although today’s system continues to invest nearly three times as much per child in the top 10 percent compared with the bottom 50 percent, which is rather astonishing for a system that is supposed to reduce social reproduction (we will come back to this when we study the criteria of a fair educational system). At this stage, note simply that educational inequality in colonial societies such as French Algeria were incomparably higher: the ratio of money spent per child of the colonizers to money spent per child of the colonized was forty to one.

FIG. 7.8. Colonies for the colonizers: Inequality of educational investment in historical perspective

Interpretation: In Algeria in 1950, the most favored 10 percent (the colonizers) received 82 percent of total educational expenditure. The comparable figure for France was 38 percent in 1910 and 20 percent in 2018. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

During the final phase of colonization (1945–1960), the French state sought for the first time to invest significant amounts in the colonies. In decline, imperial France tried to promote a developmental perspective in the hope of persuading the colonies to remain part of an empire redefined as a social and democratic “French Union.” But as we have seen, the apportionment of state expenditure in the colonies reproduced existing inegalitarian structures. Beyond that, one should not overstate the magnitude of the metropole’s sudden generosity. In the 1950s, transfers from France to colonial budgets never exceeded 0.5 percent of the metropole’s annual national income. Such sums, while not totally negligible, quickly aroused opposition from many sides in France.18 These transfers were roughly of the same order (as a percentage of national income) as the net contribution of the wealthiest member states of the European Union (EU) (including France and Germany) to the EU budget in the decade 2010–2020; we will have more to say about what such amounts signify concretely when we look at the problems and prospects of European political integration.19 As for the French colonial empire, it is not really correct to speak of “transfers to the colonies,” given that these sums were mainly intended to pay expatriate French civil servants, who were handsomely remunerated and worked for the benefit of the colonizers. In any case, it is worth comparing the 0.5 percent of national income transferred from the metropole to civilian budgets in the colonies in the 1950s with the much larger sums (more than 2 percent of metropolitan national income) devoted to the military for the purpose of maintaining order in the colonies in the late 1950s. Apart from this final phase, moreover, it is worth noting that the sums allocated by Paris to the military to keep order and expand the colonial empire never exceeded 0.5 percent of annual metropolitan national income between 1830 and 1910. In some respects, this cost is remarkably low, given that the population of the empire at its peak was nearly 2.5 times that of the metropole (90 million compared with 40 million).20 From this it should be clear that differences in levels of development and state and military capacity created a temptation to embark on ambitious colonial adventures at very low cost.

Slave and Colonial Extraction in Historical Perspective

On the question of “transfers” between the metropole and its colonies, it is also important to point out that it would be a significant error to limit ourselves to examining the government budget balance. The taxes paid in the colonies equaled government expenditure throughout the period 1830–1950, but this obviously does not mean that there was no “colonial extraction”—that is, no profit to the colonizing power. The first to profit from colonization were the governors and civil servants of the colonies, whose remuneration came from taxes paid by the colonized populations. More generally, the colonizers, whether employed as civil servants or in the private sector (for example, in the agricultural sector in Algeria or on rubber plantations in Indochina), often enjoyed much higher status than they would have had in the metropole. To be sure, life was not always simple; some colonizers were far from wealthy, and disillusionment was common. Think, for example, of the difficulties faced by the mother of writer Marguerite Duras, whose fields on the Pacific coast were constantly flooded; or of the misfortunes of the petits blancs (poor whites), who had to contend with the colonial haute bourgeoisie, both capitalists and officials, who harassed and extracted bribes from small farmers. Still, even the poor whites had chosen their own lot to a greater extent than the natives, and they enjoyed greater rights and opportunities simply by virtue of their race.

One also has to consider the private profit extracted from the colonies. In the first colonial era, the era of the Atlantic slave trade, the profit extraction was crude and unambiguous, and the profits took the form of cold hard cash. The sums at stake have been well documented, and they were considerable. In the case of Saint-Domingue, the profits extracted from the island by way of sugar and cotton exports surpassed 150 million livres tournois annually in the late 1780s. If one includes all colonies in the same period, available estimates suggest profits of roughly 350 million livres in 1790, at a time when French national income was less than 5 billion livres. Thus, more than 7 percent in additional national income (3 percent from Haiti alone) flowed into France from the colonies; this was a huge amount, especially in view of the fact that these sums benefited a very small minority. In addition, it was pure extraction after allowing for the costs of production (especially the cost of the imports needed to produce the goods), to buy and maintain the slaves (leaving aside the profits of the slave traders), and local consumption and investment by the planters. For the United Kingdom, profits from the slave islands in the 1780s were on the order of 4–5 percent of national income.21

During the second colonial era (1850–1960), the age of the great transcontinental empires, private financial profits took more complex but ultimately just as substantial forms, provided that we look at global investment overall and not just investment in a few slave islands. Earlier, we saw the importance of international investments in Parisian fortunes during the Belle Époque. In 1912, shortly before World War I, foreign assets accounted for more than 20 percent of total Parisian wealth, and those assets were highly diversified: they included both shares and direct investments in foreign firms, private bonds issued by firms to finance their international investments, and government bonds and other forms of state borrowing, which alone accounted for nearly half of the total.22

Let us turn now to the two major colonial powers of this era, the United Kingdom and France, and note the immense (and to this day unequaled) scope of the foreign investments held by residents of these two countries (Fig. 7.9).23 In 1914, on the eve of World War I, the UK’s net foreign assets (that is, the difference between the value of investments in the rest of the world and held by British citizens and the value of investments in Britain and held by citizens of the rest of the world) amounted to 190 percent (or nearly two years’ worth) of the country’s national income. French investors were not far behind, with net foreign assets worth more than 120 percent of French national income in 1914. These gigantic asset holdings in the rest of the world were much larger than those of other European powers, and in particular Germany, which plateaued at a little more than 40 percent of national income despite the country’s remarkable industrial and demographic surge. This was partly because Germany lacked a significant colonial empire but more generally because it occupied a less important and more recent position in global commercial and financial networks. These colonial rivalries played a central role in exacerbating tensions between the powers, as in the Agadir Crisis of 1911. Wilhelm II ultimately accepted the Franco-British treaty of 1904 on Morocco and Egypt, but he obtained significant territorial compensation in Cameroon, which delayed the onset of war by a few years.

FIG. 7.9. Foreign assets in historical perspective: The Franco-British colonial apex

Interpretation: Net foreign assets (that is, foreign asset holdings by residents of each country, including its government) less assets in each country held by the rest of the world, came to 191 percent of national income in the United Kingdom in 1914 and 125 percent in France. In 2018, net financial assets amounted to 80 percent of national income in Japan, 58 percent in Germany, and 20 percent in China. Sources and series: piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.

British and French foreign asset holdings increased at an accelerated pace during the Belle Époque, and it is natural to ask how long this rising trajectory might have continued had there been no war (a question to which I will return when we study the fall of ownership society). In any event, Franco-British holdings fell precipitously after World War I and definitively in the wake of World War II, due in part to expropriation (think of the famous Russian bonds, whose repudiation after the Russian Revolution of 1917 was particularly painful for French investors) but mostly to the fact that French and British investors were obliged to sell growing fractions of their foreign holdings and lend to their own governments to finance the wars.24

To gain a better understanding of the scope of foreign investment that the United Kingdom and France accumulated in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, note that no country since then has ever held such large volumes of foreign assets in the rest of the world. For example, Japan accumulated significant foreign assets as a result of large commercial surpluses in the 1980s and beyond, as did Germany in the wake of unusually high trade surpluses since the mid-2000s, but in neither case did foreign holdings in 2018 exceed 60–80 percent of national income. That is a high level of foreign investment, quite different from the very low levels (close to zero) seen in the period 1950–1980 and significantly higher than China’s current holdings (barely 20 percent of national income in 2018)—but still much lower than the Franco-British peak on the eve of World War I (Fig. 7.9).25

One can also compare Franco-British foreign assets in 1914 (one to two years of national income) to the total assets (financial, real estate, equipment, net of debt, foreign plus domestic) held by French and British citizens at the time, which amounted to six or seven years of national income of both countries combined. In other words, one-fifth to one-quarter of what people owned at the time was held abroad. The ownership societies that prospered in France and the United Kingdom in the Belle Époque thus rested in large part on foreign assets. The key point is that these assets earned considerable income: the average yield was close to 4 percent a year, so that income on foreign capital added about 5 percent to French national income and more than 8 percent to British national income. The interest, dividends, profits, rents, and royalties earned in the rest of the world thus substantially boosted the standard of living in the two colonial powers or, more precisely, in certain segments of their population. To gauge the enormous size of the sums at stake, note that the 5 percent additional national income that France earned from its foreign possessions in the period 1900–1914 was approximately equal to the total industrial output of northern and eastern France, the most industrialized regions of the country. Hence this was a very substantial financial boost.26

From the Brutality of Colonial Appropriation to the Illusion of “Gentle Commerce”

It is striking to note that the financial profits that France and Britain reaped from their colonies were of roughly the same order in the periods 1760–1790 and 1890–1914: 4–7 percent of national income in the earlier period and 5–8 percent in the later. There are obviously important differences between the two periods, however. In the first colonial era, appropriation was brutal and intensive and concentrated in small territories: slaves were transported to the islands and put to work producing sugar and cotton, and enormous profits (of up to 70 percent of output in Saint-Domingue, including income earned by colonizers) were extracted from the wealth that was produced. The extractive efficiency was maximal, but the risk of revolt was serious, and it would have been difficult to generalize the system to global scale. In the second colonial era, the modes of appropriation and exploitation were more subtle and sophisticated: investors held stocks and bonds in many countries, from which they extracted a portion of the output for each region. To be sure, this portion was smaller than could be extracted under the slave regime, but it was far from negligible (often 5–10 percent of a country’s production, sometimes even more), and more importantly, it could be applied in many more parts of the world or even to the entire globe. Ultimately, the scale of the second system dwarfed the first, and it might have grown even larger had its development not been interrupted by the eminently political shocks of the period 1914–1945. The first colonial era was ended by rebellions, and the second by wars and revolutions, themselves caused by frenetic competition among colonial powers and by violent social tensions born of the internal and external inequalities engendered by globalized ownership societies (at least in part; I will come back to this).

One might also be tempted to think that another difference between the two situations was that the slave trade and exploitation of slaves on the islands in the first colonial era were “illegal” (or at any rate “immoral”), while the French and British accumulation of foreign financial assets in the second colonial era was perfectly “legal” (and certainly more “moral”), having been accomplished in accordance with the virtuous and mutually profitable logic of “gentle commerce.” The second colonial era did indeed justify itself in terms of a potentially universalistic (though in practice highly asymmetric) proprietarian ideology and a model of development and trade similar in certain respects to the current neo-proprietarian model, in which extensive cross-border financial holdings can in theory be beneficial to all. According to this virtuous, harmonious scenario, some countries can run large trade deficits (if, for example, they have good products to sell to the rest of the world or because they deem it necessary to build reserves for the future, as a hedge, for instance, against demographic aging or potential disaster), that leads them to accumulate assets in other countries—assets which of course then earn a fair remuneration. Otherwise, who would make the effort to accumulate wealth, and who would agree to abstain patiently from consumption? The problem is that this stark contrast between two eras of colonialism—one brutal and violently extractive, the other virtuous and mutually profitable—while admissible in theory fails to capture the subtler shades of reality.

In practice, a significant portion of French and British foreign holdings in the period 1880–1914 came directly from the compensation that Haiti was forced to pay in exchange for its freedom or that taxpayers in both countries were forced to pay to slaveowners deprived of their human property (which, as Victor Schoelcher liked to say, had been acquired “in a legal framework” and therefore could not be purely and simply expropriated without just indemnification). More broadly, a significant fraction of foreign assets consisted of public and private debt extracted by force—in many cases akin to military tribute. This was the case, for example, with the public debt imposed on China in the wake of the Opium Wars of 1839–1842 and 1856–1860. Britain and France held China responsible for the military confrontations (shouldn’t the Chinese government simply have agreed to import opium?) and therefore compelled the Chinese to repay a heavy debt to compensate the aggressors for military costs they would have preferred to avoid and to encourage China to behave more docilely in the future.27

Through this device of “unequal treaties” the colonial powers were able to seize control of many countries and foreign assets. On the basis of a more or less convincing pretext (such as a country’s refusal to open its borders widely enough, or a riot in which European citizens were attacked, or a need to maintain order), a military operation would be mounted; this was followed by the colonial power demanding jurisdictional privileges or a financial tribute of some kind, payment of which would require seizure of administrative control over, say, customs, and then over the entire fiscal system so as to improve the yield to colonial creditors (in conjunction with steeply regressive taxes, which generated strong social tensions and in some cases authentic tax revolts against the occupier), leading ultimately to seizure of the entire country.

The case of Morocco is exemplary in this regard. Public opinion in Morocco in favor of assisting the country’s Muslim neighbors in Algeria (conquered by France in 1830) compelled the sultan to offer refuge to Algerian rebel leader Abdelkader. This provided France with the ideal pretext to shell Tangiers and impose a first treaty on Morocco in 1845. Then Spain seized on a Berber revolt as a pretext to capture Tétouan and impose a heavy war indemnity in 1860; the resulting debt was subsequently refinanced through bankers in London and Paris, and repayment of these loans soon absorbed more than half of Morocco’s customs revenues annually. One thing led to another, and France ultimately made Morocco a protectorate in 1911–1912 after invading much of the country in 1907–1909, officially to protect its financial interests and its citizens following rioting in Marrakech and Casablanca.28 It is interesting to note that the conquest of Algeria in 1830 was justified by the alleged need to eradicate the Barbary pirates who threatened Mediterranean shipping at the time—pirates whom the dey of Algiers was accused of tolerating in his port, thus providing a pretext for the French mission civilisatrice. Another, no less serious motive was that, to supply grain to the expeditionary force dispatched to Egypt in 1798–1799, France had incurred a debt guaranteed by the dey, which first Napoleon and then Louis XVIII refused to repay, and this became a recurrent source of tension during the Restoration. Here is yet another illustration of the limits of proprietarian ideology when it comes to regulating both social relations and interstate relations: in a dispute, each side can use this ideology in its own way to justify its desire for wealth and power, which quickly leads to logical contradictions when it comes to defining norms of justice acceptable to all; conflicts then have to be resolved by the application of naked power and armed force.

Note, moreover, that such rough justice between states, and recurrent blurring of the lines between military tribute in the past and public debt in the present, can also be found within Europe itself. At the end of the long and complex process of German unification, from the German Confederation of 1815 to the North German Confederation of 1866, the new imperial German state availed itself of its victory in the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871) to impose on France a heavy indemnity of 7.5 billion gold francs, equal to 30 percent of French national income at the time.29 This was a significant amount, well beyond the military costs of the war, but France paid in full without a notable impact on its accumulated financial wealth—a sign of just how prosperous French property owners and savers were at the end of the nineteenth century.

The difference was this: while the European colonial powers sometimes imposed tributes on one another, when it came to imposing a highly lucrative domination on the rest of the world, they were usually allies—at least until their ultimate self-destruction by armed forces in the period 1914–1945. Although the justifications and forms of pressure have evolved, it would be wrong to imagine that such rough treatment of some states by others has totally disappeared or that naked power no longer plays a role in determining the financial fortunes of states. Consider, for example, the unrivaled ability of the United States to impose staggering sanctions on foreign firms as well as dissuasive commercial and financial embargoes on governments deemed to be insufficiently cooperative—an ability not unrelated to US global military dominance.

On the Difficulty of Being Owned by Other Countries

Some of France and Britain’s foreign assets in the period 1880–1914 also came from the trade surpluses the two industrial powers had been able to run since the beginning of the nineteenth century. Several points call for clarification, however. First, it is not easy to say what trade flows would have looked like in the absence of armed domination and violence. This is obvious in the case of the opium exports forced on China in the wake of the Opium Wars, which contributed to the official trade surpluses of the first two-thirds of the nineteenth century. But it is also true for other exports, including textiles. Trade patterns were shaped by the international balance of power and by extremely violent interstate relations. The textile industry itself depended on supplies of cotton produced by slave labor, and exports benefited from punitive tariffs imposed on Indian and Chinese output, about which I will say more later.

To view nineteenth-century trade flows as straightforward consequences of “market forces” and “the invisible hand” is hardly serious and cannot explain the manifestly political transformations of the interstate system and global trade that actually occurred. In any event, if one takes the trade flows as given, the fact remains that the trade surpluses we can measure on the basis of available sources for the period 1800–1880 can explain only a small part (between a quarter and a half) of the enormous mass of foreign financial assets that Britain and France had accumulated by 1880. Most of those assets were therefore accumulated in other ways, whether by the quasi-military forms of tribute discussed earlier, uncompensated appropriations of one sort or another, or unusually high returns on certain investments.

Finally but perhaps most significantly, it is important to understand that accumulations of wealth such as France and Britain amassed in the period 1880–1914 and such as other countries may amass in the future, whether legally or illegally, morally or immorally, begin to follow an accumulative logic of their own once they attain a certain size.

At this point it is important to call attention to a fact that may not be sufficiently well known, although it is well attested by trade statistics from the era and was well known to contemporaries. In the period 1880–1914, the United Kingdom and France earned so much from their investments in the rest of the world (roughly 5 percent additional national income for France and more than 8 percent for the United Kingdom) that they could allow themselves to run persistent structural trade deficits (an average of 1–2 percent of national income for both countries) while continuing to accumulate claims on the rest of the world at an accelerated pace. In other words, the rest of the world labored to increase the consumption and standard of living of the colonial powers, even as it became increasingly indebted to those powers. This situation is like that of the worker who must devote a large portion of his salary to pay rent to his landlord, which the landlord then uses to buy the rest of the building while leading a life of luxury compared to the family of the worker, which has only his wages to live on. This comparison may shock some readers (which I think would be healthy), but one must realize that the purpose of property is to increase the owner’s ability to consume and accumulate in the future. Similarly, the purpose of accumulating foreign assets, whether from trade surpluses or colonial appropriations, is to be able to run subsequent trade deficits. This is the principle of all wealth accumulation, whether domestic or international. If one wants to get beyond this logic of endless accumulation, one needs to equip oneself with the intellectual and institutional means to transcend the idea of private property—for example, the concept of temporary ownership and permanent redistribution of property.

Today, in the early twenty-first century, some people think that trade surpluses are an end in themselves and can continue indefinitely. This perception reflects a political and ideological transformation that is itself extremely interesting. It corresponds to a world in which a country wishes to create jobs for its people in export sectors while accumulating financial claims on the rest of the world. Yet today as in the past, those financial claims are not only intended to create jobs and bring prestige and power to the surplus country (even if those goals cannot be neglected); they are also meant to procure future financial income. This, of course, makes it possible to acquire not only additional assets but also goods and services produced by other countries without the need to export anything at all.

Consider the petroleum exporting countries, which are the most obvious contemporary example of countries amassing large amounts of foreign assets. It is obvious that these countries’ oil and gas exports and attendant trade surpluses will not last forever. Their goal is precisely to accumulate enough financial claims on the rest of the world to be able to live in the future on the income from those investments and to import all sorts of goods and services from the rest of the world well after their stocks of hydrocarbons are completely exhausted. In the case of Japan—which currently holds the most impressive portfolio of foreign assets in the world (Fig. 7.9) thanks to the trade surpluses racked up by Japanese industry in past decades—it is possible that the country is on the brink of a phase of structural trade deficit (or at least the end of its accumulative phase). Germany and China will probably also face such turning points, once saving reaches a certain level and the aging of their populations has proceeded further than it has today. There is obviously nothing particularly “natural” about such evolutions. They depend on political and ideological transformations in the countries involved and on the way in which various state and economic actors perceive and interpret what is at stake.

I will come back to these questions and say more later about possible sources of future conflict. The important point for now is simply that international property relations are never simple, especially when they attain such huge proportions. In fact, property relations in general are always more complex than the fairy tales one reads in economics textbooks, where they are often presented as spontaneously harmonious and mutually advantageous. It is never simple for a worker to sacrifice a substantial portion of her wage to an owner’s profit or a landlord’s rent or for the children of renters to pay rents to the children of landlords. That is why property relations are always conflictual and always give rise to institutions whose purpose is to regulate their scope and transmissibility. Regulation can be achieved through union struggles or power-sharing mechanisms within firms, through laws governing wage setting and rent control or limiting the power of landlords to evict tenants, by setting the term of a lease or conditions of an eventual buyout, or by establishing estate taxes or other fiscal and legal devices to facilitate the acquisition of property by new social groups and limit the reproduction of wealth inequalities across generations.

When one country is required to pay another country profits, rents, and/or dividends over a long period of time, however, property relations can become even more complex and explosive. Constructing norms of justice acceptable to a majority through democratic deliberation and social struggle is already a complex enough process within a single political community; it becomes practically impossible when the owners of property are external to the community. In the most common and likely case, such external property relations will be regulated by violence and military force. In the Belle Époque, the colonial powers made ample use of gunboat diplomacy to ensure that interest and dividends would be paid on time and that no one would think of expropriating creditors. The military and coercive dimension of international financial relations and investment strategies also plays an essential role today, even though the interstate system has become much more complex. In particular, two of today’s leading international creditors, Japan and Germany, are states without armies, whereas the two principal military powers, the United States and to a lesser degree China, are focused more on investing domestically than on accumulating external financial claims. This may be due to the continental dimensions of both of these states as well as to their demographic dynamism (which may be about to change in China and may someday change in the United States).

In any case, the Franco-British experience with foreign asset accumulation in the Belle Époque is rich in instruction for the future and for our overall understanding of the proprietarian inequality regime, especially in its international and colonial dimension. In this respect, it should be noted that the mechanisms of financial and military coercion developed by the colonial powers to extend the accumulation process over time applied not just to explicitly colonized territories but also to countries that were not (or have not yet been) colonized, such as China, Turkey (the Ottoman Empire), Iran, and Morocco. Indeed, when one studies the available sources of information regarding the international investment portfolios of the period, one finds that they extended far beyond the colonies in the strict sense.