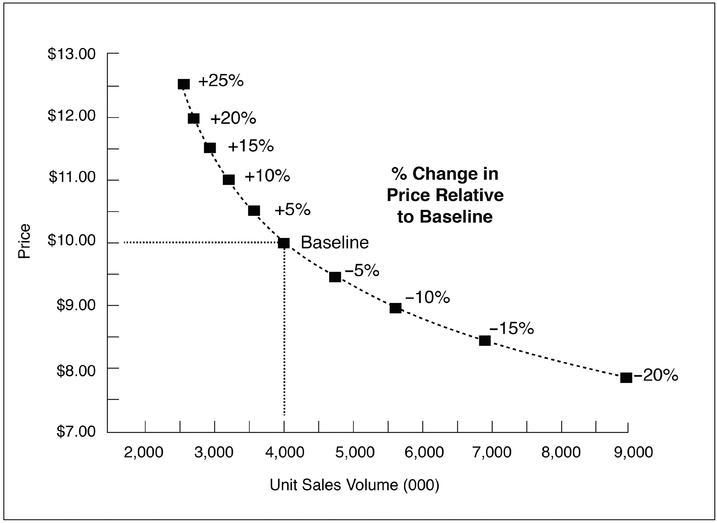

EXHIBIT 1-1 Breakeven Sales Curve Associated with Different Price Changes

Coordinating the Drivers of Profitability

If you have to have a prayer session before raising the price by 10 percent, then you’ve got a terrible business.

Warren Buffet1

Marketing consists of four key elements: The product, its promotion, its placement or distribution, and its price. The first three elements—product, promotion, and placement—comprise a firm’s effort to create value in the marketplace. The last element—pricing—differs essentially from the other three: It represents the firm’s attempt to capture some of the value in the profit it earns. If effective product development, promotion, and placement sow the seeds of business success, effective pricing is the harvest. Although effective pricing can never compensate for poor execution of the first three elements, ineffective pricing can surely prevent those efforts from resulting in financial success. Regrettably, this is a common occurrence.

Complicating matters, the ability to harvest potential profits is in a continuous state of flux as technology, regulation, market information, consumer preferences, or relative costs change. Consequently, companies that expect to grow profitably in changing markets often need to break old rules, including those that govern how they will set prices to earn revenues. Our interest in strategic pricing dates back to when the telecommunications industry was deregulated in most developed countries and new suppliers recognized that they could gain both market share and profitability by replacing the then prevailing price-per-minute revenue models with more innovative models—first including a price per month for a bundle of “peak” minutes plus “free” off-peak time. Later, they introduced “family plans” involving the sharing of minutes across numbers. Similarly, Apple quickly went from nothing to market leadership in music sales, in large part because, after the internet slashed the cost of distribution, it was the first to recognize that it was better to price music by the song than by the album. And at the time of writing this edition, the predominant revenue model for music is shifting yet again, with subscription-based streaming services such as Spotify and Apple Music® overtaking digital music store sales.2 Producers of new online media created a new metric for pricing ads—cost per click—that aligned the cost of an ad more closely to its value than was possible in traditional print media. Even governments have begun to use prices, often called “user fees,” instead of taxes to raise revenues and better allocate scarce resources. Congested cities, such as London and Singapore, charge to drive a car into congested areas during peak times and highways in major U.S. cities such as Atlanta and Minneapolis increasingly have express lanes that are kept moving even during rush hours by adjusting a wirelessly collected price to access them.3

Unfortunately, few managers, even those in marketing, have been trained in how to develop innovative pricing strategies such as these. Most companies still make pricing decisions in reaction to change rather than in anticipation of it. This is unfortunate, given that the need for rapid and thoughtful adaptations to changing markets has never been greater. The information revolution has made prices everywhere more transparent and customers more price aware.4 The globalization of markets, even for services, has increased the number of competitors and often lowered their cost of sales. The high rate of technological change in many industries has created new sources of value for customers, but not necessarily led to increases in profit for the producers.

Improvements in technology have driven an explosion of data that some suppliers are using to target customers they can serve more profitably: Either because those customers are more willing to pay for the differentiation the company can offer or because the company can meet their needs more cost-effectively than competitors. This is especially true of consumer goods, where manufacturers used to operate with only minimal and long-delayed data on where and how well their products were selling in retail stores, and pricing involved negotiating “trade promotions” with channel intermediaries that may or may not have passed the savings on to end consumers. Now, with the ability to buy almost “real time” data on how individual package sizes are selling in types of outlets and in specific geographies, manufacturers are able to develop more sophisticated pricing strategies to target specific types of customers and competitors. At the extreme, many retailers charge online shoppers different prices or offer them different product assortments based on the type of device they are using to access the site, with the theory that the type of device can signal a systematic difference in willingness-to-pay.5

Learning to make sales more profitably is the key to achieving sustainable growth in revenue, market share, and company value over the long haul. When the first edition of this book was published more than three decades ago, the idea that profit margins should be prioritized over growth was seen as short-sighted. A 1975 study conducted at the Harvard Business School using the PIMS (which originally stood for Profit Impact of Market Share) database of historical market performance of leading global companies reported a strong, consistently positive, correlation between a company’s market share and its relative profitability within an industry.6 In the Harvard Business Review article discussing this study, the authors proposed multiple plausible reasons why a larger market share could enable a company to operate more profitably. That led to an explosion of literature by marketing theorists and leading consultancies advocating aggressively low pricing as an “investment” in growth that would eventually create “cash cows”—exceptionally profitable revenue streams requiring little investment to maintain them.

Unfortunately, companies that adopted this approach to pricing, more often than not, found the theory and the eventual profitability it promised lacking. As the PIMS database grew to cover multiple years, more nuanced relationships were revealed. Although a cross-sectional correlation between market share and profitability proved durable, how a company invested to grow was shown to be a better predictor of financial success. Consequently, the PIMS organization cleverly redefined their acronym to stand for Profit Impact of Marketing Strategy.

More recent research by Deloitte Consulting LLP has brought further clarity to the relationship between growth and profitability. Deloitte compiled a time-series dataset of 394 companies, covering the period from 1970 to 2013 with exceptional, mediocre and poor performers matched by industry. The researchers defined “exceptional performance” as a company achieving superior profitability (return on assets), stock value, and revenue growth for more than a decade and sought to understand how a small minority of firms manage to achieve it. Their conclusion:

a [near term] focus on profitability, rather than revenue growth or [stock] value creation, offers a surer path to enduring exceptional performance.7

So how do marketing and financial managers at exceptional companies achieve sustainable exceptional profitability? It is not the result of slashing overheads more ruthlessly than their competitors. In fact, Deloitte’s data indicates that exceptional performers tend to spend a bit more than competitors (as a percent of sales) on R&D and SG&A. Their exceptional profitability and, eventually, exceptional stock valuations are built on higher margins per sale that fund initiatives to grow revenues without compromising those margins.8

Unfortunately, many companies fail to understand that making sales profitably should be the first priority—not an afterthought—of a strategy for driving growth. Creating and communicating superior value propositions or finding a way to deliver superior value at lower cost is a precondition to sustainable revenue growth. Many years of experience have taught us that applying the principles explained in these pages is necessary to make sales more profitable and at least equal with the best in the industry.

The difference between successful and unsuccessful pricers lies in how they approach the process. To achieve superior, sustainable profitability, pricing must become an integral part of strategy. Strategic pricers do not ask, “What prices do we need to cover our costs and earn a profit?” Rather, they ask, “What costs can we afford to incur, given the prices achievable in the market, and still earn a profit?” Strategic pricers do not ask, “What price is this customer willing to pay?” but “What is our product worth to this customer and how can we better communicate that value, thus justifying the price?” When value doesn’t justify price to some customers, strategic pricers do not surreptitiously discount. Instead, they consider how they can segment the market with different products or distribution channels to serve these customers without undermining the perceived value to other customers. And strategic pricers never ask, “What prices do we need to meet our sales or market share objectives?” Instead they ask, “What level of sales or market share can we most profitably achieve?”

Strategic pricing often requires more than just a change in attitude; it requires a change in when, how, and who makes pricing decisions. For example, strategic pricing requires anticipating price levels before beginning product development. It requires determining the economic value of a product or service, which depends on the alternatives customers have available to satisfy the same need. We go into much more depth on the concept of Economic Value Estimation (EVE®) in Chapter 2. The only way to ensure profitable pricing is to reject early those ideas for which adequate value cannot be captured to justify the cost.

Strategic pricing also requires that management take responsibility for establishing a coherent set of pricing policies and procedures, consistent with the company’s strategic goals. Abdicating responsibility for pricing to the sales force or to the distribution channel is abdicating responsibility for the strategic direction of the business.

Perhaps most important, strategic pricing requires a new relationship between marketing and finance because pricing involves finding a balance between the customer’s desire to obtain good value and the firm’s need to cover costs and earn profits. Unfortunately, pricing at most companies is characterized more by conflict than by balance between these objectives. If pricing is to reflect the value to the customer, specific prices must be set by those best able to anticipate that value—presumably marketing and sales managers. The problem is that their efforts will not generate substantial profits unless constrained by appropriate financial objectives. Rather than attempting to “cover costs,” finance must learn how costs change with shifts in sales volume and use that knowledge to develop appropriate incentives for marketing and sales to achieve their objectives.

With their respective roles appropriately defined, marketing and finance can work together toward a common goal—to achieve profitability through strategic pricing.

Before marketing and sales can attain this goal, however, managers in all functional areas must discard the flawed thinking about pricing that frequently leads them into conflict and that drives them to make unprofitable decisions. Let’s look at these flawed paradigms so that you can recognize them and understand why you need to let them go.

Cost-plus pricing is, historically, the most common pricing procedure because it carries an aura of financial prudence. Financial prudence, according to this view, is achieved by pricing every product or service to yield a fair return over all costs, fully and fairly allocated. In theory, it is a simple guide to profitability; in practice, it is a blueprint for mediocre financial performance.

The problem with cost-driven pricing is fundamental: In most industries, it is impossible to determine a product’s unit cost before determining its price. Why? Because unit costs change with volume. This cost change occurs because a significant portion of costs are “fixed” and must somehow be “allocated” to determine the full unit cost. Unfortunately, because these allocations depend on volume, and volume changes as prices change, unit cost is a moving target.

To solve the problem of determining unit cost before determining price, cost-based pricers are forced to assume a level of sales volume and then to make the absurd assumption that they can set price without affecting that volume. The failure to account for the effects of price on volume, and of volume on costs, leads managers directly into pricing decisions that undermine profits. A price increase to cover higher fixed costs can start a death spiral in which higher prices reduce sales and raise average unit costs further, indicating (according to cost-plus theory) that prices should be raised even higher. On the other hand, if sales are higher than expected, fixed costs are spread over more units, allowing average unit costs to decline a lot. According to cost-plus theory, that would call for lower prices. Cost-plus pricing leads to overpricing in weak markets and underpricing in strong ones—exactly the opposite direction of a prudent strategy.

How, then, should managers deal with the problem of pricing to cover fixed costs? They shouldn’t. The question itself reflects an erroneous perception of the role of pricing, a perception based on the belief that one can first determine sales levels, then calculate unit cost and profit objectives, and then set a price. Once managers realize that sales volume (the beginning assumption) depends on price (the end of the process), the flawed circularity of cost-based pricing is obvious. The only way to ensure profitable pricing is to let anticipated pricing determine the costs incurred rather that the other way around. Value-based pricing must begin before investments are made using a process that we will describe later in this chapter.

Many companies now recognize the fallacy of cost-based pricing and its adverse effect on profit. They realize the need for pricing to reflect market conditions. As a result, some firms have taken pricing authority away from financial managers and given it to sales or product managers. In theory, this trend is consistent with value-based pricing, since marketing and sales are that part of the organization best positioned to understand value to the customer. In practice, however, their misuse of pricing to achieve short-term sales objectives often undermines perceived value and depresses future profitability.

The purpose of strategic pricing is not simply to create satisfied customers. Customer satisfaction can usually be bought by a combination of overdelivering on value and underpricing products. But marketers delude themselves if they believe that the resulting increases in sales represent marketing successes. The purpose of strategic pricing is to price more profitably by capturing more value, not necessarily by making more sales. When marketers confuse the first objective with the second, they fall into the trap of pricing at whatever buyers are willing to pay, rather than at what the product is really worth. Although that decision may enable marketing and sales managers to meet their sales objectives, it invariably undermines long-term profitability.

Two problems arise when prices reflect the amount buyers seem willing to pay. First, sophisticated buyers are rarely honest about how much they are actually willing to pay for a product. Professional purchasing agents are adept at concealing the true value of a product to their organizations. Once buyers learn that sellers’ prices are reactively flexible, they have a financial incentive to conceal information from, and even mislead, sellers. Obviously, this undermines the salesperson’s ability to establish close relationships with customers and to understand their needs.

Second, there is an even more fundamental problem with pricing to reflect customers’ willingness-to-pay. The job of sales and marketing is not simply to process orders at whatever price customers are currently willing to pay, but rather to raise customers’ willingness-to-pay to a level that better reflects the product’s true value. Many companies underprice truly innovative products because they ask potential customers, who lack prior experience from which to judge the product’s value, what they would be willing to pay for it. But we know from studies of innovations that the price has little impact on whether customers are willing to try them.9 For example, most customers initially perceived that photocopiers, mainframe computers, home air conditioners, and MP3 players lacked adequate value to justify purchase at viable prices. Only after trial by a small subset of “innovator” customers, followed by extensive marketing to communicate and guarantee value to a broader market, did these products achieve market acceptance. Forget what customers who have never used your product are initially willing to pay. Instead, understand what the value of the product could be for satisfied customers, communicate that value to the currently uninformed, and set prices accordingly. Low pricing is always a poor substitute for an inadequate marketing and sales effort.

Finally, consider the policy of letting pricing be dictated by competitive conditions. In this view, pricing is a tool to achieve gains in market share. In the minds of some managers, this method is “pricing strategically.” Actually, it is more analogous to “letting the tail wag the dog.” Occasionally, networking effects make a product or service more valuable when other people are patronizing the same brand, as was the case for example with eBay, the online marketplace. In most cases, however, there is no reason why an organization should seek to achieve market share as an end in itself.

Although cutting price is probably the quickest, most effective way to achieve sales objectives, it is usually a poor decision financially. Because a price cut can be so easily matched, it offers only a short-term market advantage at the expense of permanently lower margins. Consequently, unless a company has good reason to believe that its competitors cannot match a price cut, the long-term cost of using price as a competitive weapon usually exceeds any short-term benefit. Although product differentiation, advertising, and improved distribution do not increase sales as quickly as price cuts, their benefit is more sustainable and thus is usually more cost-effective in the long run.

The goal of pricing should be to find the combination of margin and market share that maximizes profitability over the long term. Sometimes, the most profitable price is one that substantially restricts market share relative to the competition. Godiva chocolates, Apple iPhones®, Peterbilt trucks, and Snap-on tools would no doubt all gain substantial market share if priced closer to the competition. It is doubtful, however, that the added share would be worth forgoing their profitable and successful positioning as high-priced brands.

Strategic pricing requires making informed trade-offs between price and volume in order to maximize profits. These trade-offs come in two forms. The first trade-off involves the willingness to lower price to exploit a market opportunity to drive volume. Cost-plus pricers are often reluctant to exploit these opportunities because they reduce the average contribution margin across the product line, giving the appearance that it is underperforming relative to other products. But if the opportunity for incremental volume is large and well targeted, a lower contribution margin can actually drive a higher total profit. The second trade-off involves the willingness to give up volume by raising prices. Competitor- and customer-oriented pricers find it very difficult to hold the line on price increases in the face of a lost deal or reduced volume. Yet the economics of a price increase can be compelling. For example, a product with a 30 percent contribution margin could lose up to 25 percent of its volume following a 10 percent price increase before that move results in lower profitability.

Effective managers of pricing regularly evaluate the balance between profitability and market share and are willing to make hard decisions when the balance tips too far in one direction. (We will show you how to make such calculations later in this book). Key to making those managers effective, however, is performance measures and incentives that reward them for improving profitability, not just revenue.

Economic theorists propose pricing based upon estimating the demand curve for a product and then “optimizing” the price level, given the incremental cost of production. In theory, this is totally consistent with the approach we propose in this book, but in practice it is almost always impractical. The reason lies in the assumption that a demand curve is something stable that one can measure with sufficient speed and accuracy to continually optimize it. Contrary to the assumptions that economists make when studying markets, the demand for individual products or brands within markets is rarely stable or easily measured. The reason: Sensitivity to price depends as much on ever-changing purchase contexts and perceptions as on underlying needs or preferences. For example, contradicting the assumption of a demand curve, the amount of a product that customers will buy at a particular price point is strongly affected by the prices they paid recently. When gasoline prices are rising, the demand for premium grades of gasoline will fall quickly by a much greater percentage than demand for regular grades. But when prices decline back to where they started, demand for premium grades will not recover quickly. That is, demand when prices are going up is generally much more “price elastic” than when prices are coming down.

More importantly, behavioral economics research over the past few decades has proven conclusively that differences in how prices are presented and the surrounding context can lead buyers to respond in ways that are inconsistent with the idea of a stable demand curve that reflects fixed preferences.10 For example, if one adds a higher priced product to the choices available in a store—say a “best” version to go along with a “good” and a “better” version—economic theory would predict that the higher-priced “best” version would primarily draw sales from the mid-priced “better” version, which turns out to be true. What it does not predict is that the mid-priced version will at the same time gain sales at the expense of the cheapest version even though the prices of those two versions remain unchanged.11 To add to the instability, we know that the demand for the mid-price product will be greater if the offers are presented beginning from the top down rather than from the bottom up.12

These examples illustrate just a few of the effects that appear to shift demand curves in ways that are contextual. Still, one cannot deny the fact that the profitability of a price increase will depend upon whether the loss in sales is not too great, while the profitability of a price decrease depends upon whether the gain in sales is great enough. Economists refer to the actual percentage change in sales divided by the percentage change in price as the price elasticity of demand. Actual elasticity depends in part upon how effectively marketers manage customer perceptions and the purchase context, as you will come to see in the following chapters. Moreover, many factors that influence price elasticity are not under the marketer’s control, making precise estimates of actual price elasticity very difficult and only rarely cost effective. Consequently, we have found that instead of asking “What is price elasticity for this product?” it is often more practical and useful to ask “What is the minimum elasticity that would be necessary to justify a particular price change?” that has been proposed to achieve some business objective. To put the question in less technical jargon, we ask “What percent change in sales would be necessary (which is the same as asking what price elasticity would be necessary) for a proposed price change to maintain the same total profit contribution after a price change?” We refer to the answer as the breakeven sales change associated with a proposed price change.

If we create a graph of breakeven sales changes associated with different potential price changes, we can create a breakeven sales curve that looks much like a demand curve, as shown in Exhibit 1-1, which shows the example of a product that earns a 45 percent gross margin at a baseline price of $10. It is a representation of how much demand is needed to maintain current profitability as prices change. If actual demand proves to be less elastic (steeper) than the breakeven sales curve, then higher prices will be more profitable. If the actual demand proves to be less steep (more elastic) than the breakeven sales curve, then lower prices will be more profitable. Technical details about how to calculate a correct breakeven sales change for any particular product and pricing decision are described in Chapter 9.

None of this implies that research to understand demand price elasticity is not valuable. We are simply observing that, given the usual instability of demand estimates over the time period required to make them, attempting to improve profitability by exactly “optimizing” price levels is usually not practical. What is valuable is research to understand how differences in identifiable purchase contexts (e.g., online versus in-store purchases, standard versus rush orders) or how marketing strategies to influence perceptions of value can influence demand elasticity. Research is also useful when developing offers to understand the relative impact of different features and services that one might offer on perceived value.

Finally, we should acknowledge that it is possible in a small number of markets to measure demand price elasticity accurately in real time, enabling mangers to track the effect of changes ranging from the weather to the daily news, to the time of day can have on them. Consumer packaged goods companies can purchase huge quantities of scanner-recorded sales data from retail stores, far more than would ever be practical to generate from market research. They can then build “big data” statistical models that use such data to measure price elasticity as precisely as possible by measuring and controlling for many contextual factors (such as alternatives available in the store and their prices, the time of day and day of week, the size of the customers total purchase, the store location) that can influence it. In these cases, the effort to make small price adjustments to optimize profitability have proven worthwhile.

EXHIBIT 1-1 Breakeven Sales Curve Associated with Different Price Changes

As you probably remember from basic economics, the optimal price one can charge is limited by the demand curve: A summary of what customers are willing to pay to buy various quantities of volume. Pricing, given the assumptions of economics, is simply about optimizing the price level given that demand. In reality, however, demand for most products and services is not given. It is created, sometimes thoughtfully and sometimes haphazardly, by decisions that sellers make about what to offer their customers, how to communicate their offers, how to price differently across customers or applications and how to manage customer price expectations and incentives. Making these decisions thoughtfully and implementing them effectively to maximize profitability is what we call “strategic pricing.”

The word “strategic” is used in various contexts to imply different things. Here, we use it to mean the coordination of otherwise independent activities to achieve a common objective. For strategic pricing, the objective is sustainable profitability. Achieving exceptional profitability requires making thoughtful decisions about much more than just price levels. It requires ensuring that products and services include just those features that customers are willing to pay for, without those that unnecessarily drive up cost by more than they add to value. It requires translating the differentiated benefits your company offers into customer perceptions of a fair price premium for those benefits. It requires creativity in how you collect revenues so that customers who get more value from your differentiation pay more for it. It requires varying price to use fixed costs optimally and to discourage customer behaviors that drive excessive service costs. It sometimes requires building capabilities to mitigate the behavior of aggressive competitors.

Although different strategies can achieve profitable results even within the same industry, nearly all successful pricing strategies embody three principles. They are value-based, proactive, and profit-driven:

These three principles will resurface throughout this book as we discuss how to define and make good choices. Strategic pricing is not a discipline separate from the rest of marketing strategy; it is rather a set of principles for creating marketing strategies that drive growth profitably.

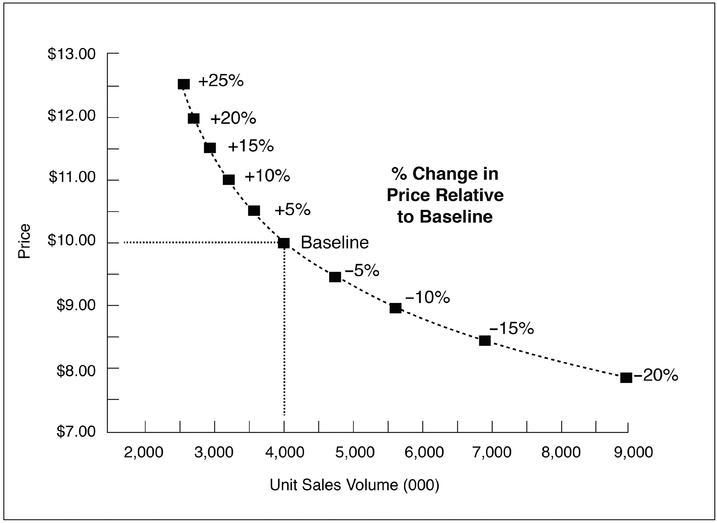

A good pricing strategy involves six distinct but very different choices that build upon one another. The choices are represented graphically as six points in what we call the Value Cascade (Exhibit 1-2). The core function of a successful firm is to create value; first and foremost for customers, but also for the internal constituencies that rely on the firm for employment and returns on investment. Strategic pricing is about managing value, from its creation through its capture in price setting, in a coordinated way that enables the organization to achieve a high, sustainable return from its efforts.

EXHIBIT 1-2 The Value Cascade: Strategic Pricing Requires Effective Management of Both Value and Price

The first thing that strikes most people new to the subject of strategic pricing is that setting a price level is just one step in a multistep process that impacts the full range of marketing decisions. If the goal of pricing profitably is considered only when price levels are set, then multiple marketing choices are likely to be made in ways that will dissipate profit potential (the “gaps” in our diagram) well before any product or service is offered for sale.

Although this book contains a chapter devoted to addressing each of these topics individually, it is useful to have an overall vision—a map if you will—of how and why they fit together in this particular order. Both managers and pricing consultants are often called upon to fix strategies that are generating poor financial returns despite driving revenues. Consequently, they may start anywhere on this choice cascade based upon their initial assessment of the potential for improvement. For our overview, we will follow the order of the numbers in the exhibit, which reflect the order in which you would typically need to address these issues if building the marketing strategy for a new product or service from scratch.

It is often asserted as a truism that the value of something is whatever someone will pay for it. We disagree. People sometimes pay for things that soon disappoint them in use (for example, time-share condominiums). They fail to get “value for money,” do not repeat the purchase, and discourage others from making the same mistake. At the other extreme, people are often reluctant to pay any price for radical new innovations simply because they lack the experience, either their own or that of someone else whose judgment they trust, from which to judge the value that the innovation could bring to their lives. For companies trying to gain share in established markets by creating differentiated product and service offerings, the challenge is simply to get customers already in the market to pay a premium price that exceeds the added cost to deliver that differentiation.

Of course, it is sometimes possible to deceive people into making onetime purchases at prices ultimately proven to be unjustified, but that is not a viable strategy for an ongoing enterprise, nor is it our agenda in this book. Our intention is to show marketers how to create value cost-effectively and convince people to pay prices commensurate with that value. We expect that, as a result, those of you who apply these ideas will contribute to an economic system in which firms that are more adept at creating value for customers are most rewarded with higher margins and market value.

Some companies that have exceptional technologies and capabilities with the potential to create great value fail to convert them into offers that generate exceptional, or even adequate, profitability. They make the mistake of believing that more, from a technological perspective, is necessarily better for the customer. One of us worked for a company making high-quality office furniture that was disappointed by its low share in fast-growing, entrepreneurial markets. The company wanted a strategy to convince those buyers what more established companies recognized already: That highly durable office furniture that would hold its appearance and function for 20 or more years was a good investment. But it took only a few interviews with buyers in the target market to recognize the problem. Companies in this market expected either to be bought out in five years or be gone. The problem was not that customers did not recognize the differentiating benefits of the company’s products. It was that the target market saw little value associated with those benefits.

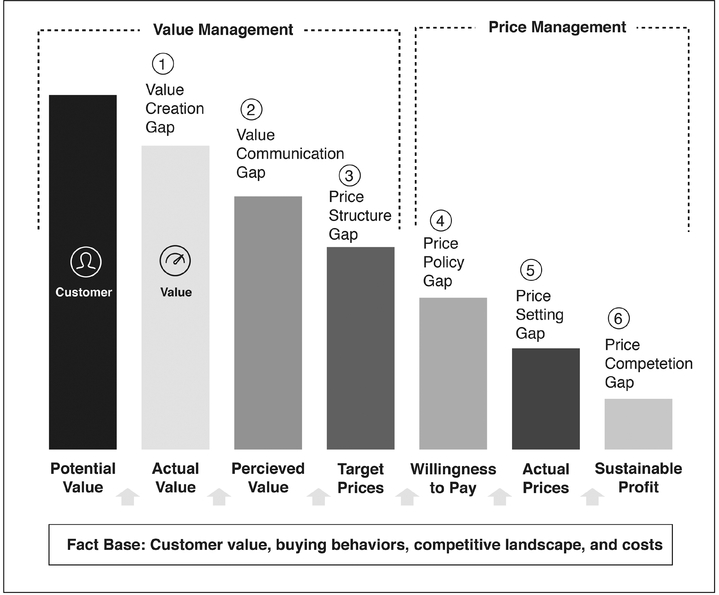

Exhibit 1-3 illustrates the flawed progression of cost-plus pricing and the necessary progression for value-based pricing. Cost-based pricing is product driven. Engineering and manufacturing departments design and make what they consider a “good” product. In the process, they make investments that incur costs to add features and related services. Finance then totals these costs to determine a “target” price. Only at this stage does marketing enter the process, charged with the task of demonstrating enough value in the product to justify pricing to customers.

EXHIBIT 1-3 Value-Based Pricing Involves Offering Customers “Good Value”

If the cost-based price proves unjustifiable, managers may try to fix the disappointing sales by allowing “flexibility” in the price. Although this tactic may help meet the sales goal, it is not fundamentally a solution to the problem of pricing profitably. That problem will arise again as the features and costs of the new products continue to mismatch the needs and values of customers.

Solving the problem of product development and costing disconnected from value to the customer requires more than a simple fix. It requires a complete reversal of the process. For value-based pricing, the target price is based on an estimate of value, not costs. The target price then drives decisions about what costs to incur, rather than the other way around.

The Story of the Mustang

Product development driven by value-based pricing is still the exception, but not among the most successful product launches. One early example of a successful new product built to be a “good value” was a spectacularly successful car developed at Ford Motor Company. Five decades ago, Ford regained its footing by building the first sports car to sell at a price point that middle-class people could afford. From an engineering perspective, it was not the most technically advanced. From the customers’ perspective, it represented a better value than anything else in the market. From a sales and profit perspective, it was one of the most successful car launches in history and continues to sell today in its sixth generation.

In the early 1960s, America was young, confident, and in love with sports cars. Many popular songs of the era were odes to those cars. Unfortunately for Ford, the cars arousing the greatest passion were made by other auto manufacturers. Hoping to remedy this situation, Ford set out to build a sports car that would tempt buyers to its showrooms.

Had Ford followed the traditional approach for developing a new car, management would have begun the process by sending a memo to the design department, instructing it to develop a sports car that would top the competition. Each designer would then have drawn on individual preconceptions of what makes a good sports car in order to design bodies, suspensions, and engines that would be better. In a few weeks, management would have reviewed the designs and picked out the best prospects. Next, management would have turned those designs over to the marketing research department. Researchers would have asked potential customers which they preferred and whether they liked Ford’s designs better than the competition’s, given prices that would cover their costs and yield the desired rate of return. The best choice would ultimately have been built and would have evoked the adoration of many, but it would have been purchased by only the few who could have afforded it.

Fortunately, Ford had a better idea. Unlike at other companies, the leading manager in charge of the project was not an expert in finance, accounting, or production. He was a marketer. So Ford did not begin looking for a new car in the design department. The company began by researching what customers wanted. Ford found that a large and growing share of the auto market longed for a sports car, but that most people could not afford one. Ford also learned that most buyers did not really need much of what makes a “good” sports car to satisfy their desires. What they craved was not sports-car performance—requiring a costly engine, drive train, and suspension—but sports-car excitement—styling, bucket seats, vinyl trim, and fancy wheel covers. Nobody at the time was selling excitement at a price that most customers could afford: Less than $2,500.

The challenge for Ford was to design a car that looked sufficiently sporty to satisfy most buyers, but without the costly mechanical elements of a sports car that drove its price out of reach. To meet that challenge, Ford built its sports car with the mechanical workings of an existing economy car, the Falcon. Many hard-core sports-car enthusiasts, including some at Ford, were appalled. The car did not match the technical performance of some of its competitors, but it was what many people wanted, at a price they could afford.

In April 1964, Ford introduced its Mustang sports car at a base price of $2,368. More Mustangs were sold in the first year than any other car Ford ever built. In just the first two years, net profits from the Mustang were $1.1 billion in 1964 dollars.* That was far more than any of Ford’s competitors made selling their “good” sports cars, priced to cover costs and achieve a target rate of return.

Ford began with the customers, asking what they wanted and what they were willing to pay for it. Their response determined the price at which a car would have to sell. Only then did Ford attempt to develop a product that could satisfy potential customers at a price they were willing to pay, while still permitting a substantial profit.

Costs played an essential role in Ford’s strategy, which determined in part what Ford’s product would look like. Cost considerations determined what attributes of a sports car the Mustang could include and what it could not, while still leaving Ford with a profit. For what they would pay, customers could not afford everything they might have liked. At $2,368, however, what they got in the Mustang was a better value.

* Lee Iacocca (with William Novak), Iacocca: An Autobiography (Toronto: Bantam Books, 1984), p. 74.

In the last two decades, designing product and service offers that can drive sales growth at profitable prices has gone in the past two decades from being unusual to being the goal at most successful companies.15 From Marriott to Boeing, from medical technology to automobiles, profit-leading companies now think about what market segment they want a new product to serve, determine the benefits those potential customers seek, and establish target prices those customers can be convinced to pay. Value-based companies challenge their engineers to develop products and services that can be produced at a cost low enough to make serving that market segment profitable at the target prices. The first companies to successfully implement such a strategy in an industry gain a huge market advantage. The laggards eventually must learn how to manage value just to survive.

The key to creating good value is first to estimate how much value different combinations of benefits could represent to customers, which is normally the responsibility of marketing or market research. In Chapter 2, we define more clearly what we mean by “value” and describe ways to estimate it.

Understanding the value your products create for customers can still result in poor sales unless customers recognize the value they are obtaining. A successful pricing strategy must justify the prices charged in terms of the value of the benefits provided. Developing price and value communications is one of the most challenging tasks for marketers because of the wide variety of product types and communication vehicles.

While much of this book focuses on how to create and measure tangible economic benefits, customers are rarely the rational economic actors portrayed in traditional economic theory. An exploding field called behavioral economics has documented a host of anomalies in consumer decision-making that run counter to the traditional economic principle of utility maximization. For example, community-held norms around fairness can limit the price a pharmaceutical firm can charge, even if the drug is a life-saver with no viable alternatives. Buyers also use mental shortcuts when making decisions, often by looking for analogous products to evaluate relative value. For this reason, many consumers view a $30 bottle of wine at a restaurant as a bargain if the other wines on the menu are priced higher, yet the same $30 bottle will feel expensive if surrounded by $20 alternatives.

As a result of these anomalies, we must realize that customer responses to price are based on more than a rational calculation of value. Rather, customers evaluate the price in terms of the entire purchase situation. Thus, one aspect of pricing strategy is the presentation of prices in ways that will influence perceptions to the seller’s benefit. Moreover, when buyers do perceive prices and purchase situations accurately, they often do not evaluate them perfectly rationally. That is not to say that buyers commonly process prices irrationally, but rather that they conserve their time and mental capacity by using imperfect, but convenient decision rules. A marketer who understands these decision rules can often present products in ways that lead buyers to evaluate them more favorably.

In some instances, marketers might employ traditional advertising media to convey their differential value, as was the case with the now famous “I am a Mac” ads created by Apple which ran from 2006 to 2009. The ads, featuring the actors Justin Long posing as a Mac® and John Hodgman as a PC (Robert Webb in the US, and David Mitchell in the UK), highlighted common problems for PC owners not faced by Mac owners. They are credited with helping grow Mac sales by an average 14.5 percent CAGR from 2005 through 2015, significantly above industry average.16 In other instances, value messages are communicated directly during the sales process with the aid of illustrations of value experienced by customers within a market segment or with the aid of a spreadsheet model to quantify the value of an offering to a particular customer.

The content of value messages will vary depending on the type of product and the context of the purchase. The messaging approach for frequently purchased search goods such as laundry detergent or personal care items will often focus on very specific points of differentiation to help customers make comparisons between alternatives. In contrast, messaging for more complex experience goods, such as services or vacations, will deemphasize specific points of differentiation in favor of creating assurances that the offering will deliver on its value proposition if purchased. For example, when Noosa International, an operator of resorts in Queensland, Australia, experienced a decline in tourism after unseasonably rainy weather, they devised a “Rainy Weather Rebate” that offered a 20 percent discount on hotel accommodations should it rain during a customer’s vacation.17 Similarly, the content of value messages must account for whether the benefits are psychological or monetary in nature. As we explain in Chapter 3, marketers should be explicit about the quantified worth of the benefits for monetary value and implicit about the quantified worth of psychological benefits.

Price and value messages must also be adapted for the customer’s purchase context. When Samsung, a global leader in cellular phone sets, develops its messaging for its Galaxy S phones, it must adapt the message depending on whether the customer is a new cell phone user or is a technophile who enjoys keeping up with the latest technology. Samsung must also adapt its messages depending on where the customer is in their buying process. When customers are at the information search stage of the process, the value communication goal is to make the most differentiated (and value-creating) features salient for the customer, so that he or she weighs these features heavily in the purchase decision. For Samsung, this means focusing on its phones’ big screens and high data-transfer speeds. As the customer moves through the purchase process to the fulfillment stage, the nature of messaging shifts from value to price as marketers try to frame their prices in the most favorable way possible. It is not an accident when a cellular provider describes its price in terms of pennies a day rather than one flat fee. Research has shown that reframing prices in smaller units that are more easily compared with the flow of benefits can significantly reduce customer price sensitivity.18

As these examples illustrate, there are many factors to consider when creating price and value communications. Ultimately, the marketer’s goal is to get the right message, to the right person, at the right point in the buying process.

Once you understand how value is created and can be communicated for different customer segments, the next choice required for a pricing strategy is to select a way to monetize that value into revenue. We call the output of this process a price structure and we cover the topic in depth in Chapter 4. The most natural price structure is price per unit (for example, dollars per ton or euros per liter). This is perfectly adequate for commodity products and services. The purpose of more complicated price structures is to reflect differences in value created, or ability to pay for it, from different customer or application segments.

An airline seat, for example, is much more valuable for a business traveler who needs to meet a client at a particular place and time than it is for a pleasure traveler for whom different destinations, different days of travel, or even non-travel related forms of recreation are viable alternatives. Airline pricers have long employed complex price structures that enable them to maximize the revenue they can earn from these different types of customers, who may be sitting next to each other on the same flight. On Monday morning or Friday afternoon, they can fill their planes mostly with business passengers paying full coach prices, but they are likely to be left with many empty seats at those prices on Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday. While they could just cut their price per seat to fill seats at those “off-peak” times, they then would end up giving business passengers unnecessary discounts as well. To attract more price-sensitive pleasure travelers without discounting to business travelers, they create segmented price structures so that most passengers pay a price aligned with the value they place on having a seat.

On the Tuesday morning when this was written, you could fly from Boston to Los Angeles and return two days later for as little as $324—but with a non-refundable ticket, a $100 charge for changes, a $15 checked baggage charge each way, and low priority for rebooking if flights are disrupted by weather or mechanical problems. For $514 you could get the very same seats on the very same flights, but with a refundable, changeable ticket and high priority rebooking in case of disruption—all things likely to be highly valued by a business traveler but barely missed by a pleasure traveler. Similarly, you could pay $934 for first-class roundtrip travel with a non-cancellable ticket and $150 change fee. Totally flexible and cancellable first-class travel would cost you $1,901. With these different options, the airlines maximize the revenue from each flight by limiting the seats available at the discounted, non-cancellable prices to a number that they project could not be sold in the higher fare classes.19

More recently, more airline price structures have been designed to discourage behaviors that make some customers more costly to serve than others. The European carrier Ryanair has taken the lead in discounting ticket prices to levels previously unseen and then charging for everything else. If you don’t print out your boarding pass before arriving at the airport, be prepared to pay Ryanair an extra €5 to check in. Want to check a bag? Add €10. Want to take a baby on your lap? €20. Want to take the baby’s car seat and stroller along? €20 each. To board the plane near the front of the line will cost you €3. Of course, you will pay for any food or drinks, but if you are short on cash you might be well advised to avoid them. The CEO recently reiterated his plan to charge for using the on-board lavatories on short flights, arguing that “if we can get rid of two of the three toilets on a 737, we can add an extra six seats.”20 Do you think this is pushing price structure complexity so far that it will drive away customers? We thought so. But consider that in less than a decade Ryanair rose to first place among European airlines and as of this writing continues to lead in passengers carried, in revenue growth, and in market capitalization.21

Ultimately, the success of a pricing strategy depends upon customers being willing to pay the price you charge. The rationale for value-based pricing is that a customer’s relative willingness-to-pay for one product versus another should track closely with differences in the relative value of those products. When customers become increasingly resistant to whatever price a firm asks, most managers would draw one of three conclusions: That the product is not offering as much value as expected, that customers do not understand the value, or that the price is too high relative to the value. But there is another possible and very common cause of price resistance. Customers sometimes decline to pay prices that represent good value simply because they have learned that they can obtain even better prices by exploiting the sellers’ reactive pricing process.

Many cable TV companies are now suffering from this problem. In order to attract new customers, or to get current customers to consolidate their phone, internet, and cable TV with the supplier, they offer heavily-discounted contracts for the first year (typically $99 per month). After one year, they raise the rate by 20 percent or more to their regular prices. But these offers have now become so widely advertised by multiple suppliers that many savvy subscribers have learned that they can beat the system. At the end of one year, many simply threaten to switch after one year to a new supplier offering the same deal. To avoid the substantial cost to manage these conversions, these same companies empower their telephone sales reps to agree to waive, or at least to reduce substantially, the increase for customers who object and threaten to change suppliers. The result: Even larger numbers of customers now threaten to change suppliers when their prices increase. Thus, a program that was designed to induce people to become loyal customers has annually eroded the value of the customer base.

Pricing policy refers to rules or habits, either explicit or cultural, that determine how a company varies its prices when faced with factors other than value and cost to serve that threaten its ability to achieve its objectives. Good policies enable a company to achieve its short-term objectives without causing customers, sales reps, and competitors to adapt their behavior in ways that undermine the volume or profitability of future sales. Poor pricing policies create incentives for end customers, sales reps, or channel partners to behave in ways that will undermine future sales or customers’ willingness-to-pay. In the terminology of economics, good policies enable prices to change along the demand curve without changing expectations in ways that cause the demand elasticity to “shift” adversely for future purchases. Chapter 5 describes good pricing policies and will alert you to the hidden risks of poor but commonly practiced policies.

According to economic theory, setting prices is a straightforward exercise in which the marketer simply sets the price at the point on the demand curve where marginal revenues are equal to the marginal costs. As any experienced pricer knows, however, setting prices in the real world is seldom so simple. On the one hand, it is impossible to predict how revenues will change following a price change because of the uncertainty about how customers and competitors will respond. On the other hand, the accounting systems in most companies are not equipped to identify the relevant costs for pricing strategy decisions, often causing marketers to make unprofitable pricing decisions.

This uncertainty about marginal costs and revenues creates a dilemma for marketers trying to set profit-maximizing prices. How should they analyze pricing moves in the face of such uncertainty? There are many pricing tools and techniques in common use today such as conjoint analysis and optimization models that take uncertain inputs and provide seemingly certain price recommendations. While these tools are valuable aids to marketers (we show how to use them to maximum advantage in Chapter 6), they run the risk of creating a sense of false precision about the right price. There is no substitution for managerial experience and judgment when setting prices.

Price setting should be an iterative and cross-functional process that includes several key actions. The first action is to set appropriate pricing objectives, whether that means to use price to drive volume or to maximize margins. In 2008, as America was falling into a recession, McDonald’s used penetration pricing to take significant market share from premium coffee shops during a time when customers were increasingly price sensitive. Once consumers tried McDonald’s new premium coffees, they found that the taste was excellent, and many opted not to switch back.

The second action is to calculate price–volume trade-offs. In the case of a 10 percent price cut for a product with a 20 percent contribution margin would have to result in a 100 percent increase in sales volume to be profitable. The same price cut for a product with a 70 percent contribution margin would only require a 17 percent increase in sales to be profitable. We are frequently surprised by how many managers make unfortunate pricing decisions because they do not understand how to make and use basic breakeven sales change calculations to evaluate pricing decisions.

Once the price–volume trade-offs are made explicit for a particular pricing move, the next activity is to estimate the likely customer response by assessing the drivers of price sensitivity that are unrelated to value. Two coffee lovers might value a cup of premium coffee equally. Despite placing equal value on the coffee, the retiree on a fixed income will be much more price sensitive than the working professional with substantial disposable income. Conversely, either of those individuals may be willing to pay the price at a premium coffee shop rather than purchase a much cheaper but equally good cup of coffee at an unbranded café nearby because the lower price at the unbranded café leads them to infer that its coffee is more likely to be of inferior quality.

The marketer’s job is to estimate how price sensitivity varies across segments in order to better estimate the profit impact of a potential pricing move. There are different ways to accomplish this task across different types of markets. For example, we describe these tools and how to use them in Chapter 8.

The final set of strategic pricing choices that managers must make to maximize growth profitably involve dealing with price competition. We are dealing with it last because making decisions that affect competitive pricing is an ongoing part of price management. Generally, these decisions occur after one has figured out how to create differentiating features and services and to capture a share of their value in revenues. But in most markets, the largest portion of price is determined, not by value-in-use to the customer, but by competition.

The potential market value of a product or service is composed of two parts: Value that is the same as that offered by the competitive alternatives (Reference Value) and value that differentiates it from competitive alternatives (Differentiating Value). For example, when a new restaurant opens in a busy area, the competitive reference value is the prices already being charged for lunch by other restaurants nearby. However, some customers may not be deterred by a premium price if they value a unique style of food or particular location.

Managing price competition involves influencing the reference value. In some markets, the reference value can be taken as given, determined by market supply and demand, and so requires no management attention except to adjust prices whenever the reference value changes. Even a large oil refinery selling wholesale gasoline and heating oil will command such a small share of the market that it can take the market prices of undifferentiated alternatives as given when setting its own prices. Price competition becomes much more challenging, however, when a seller commands a large share of a market. This is because competitors are likely to react to whatever pricing decisions it makes. Even the owner of a single retail gas station or pharmacy in a local market with only one or two alternatives must generally expect that competitors will notice and react to changes in its prices, thus affecting the revenue impact of pricing decisions. Anytime that a firm has a large share of even a small market, the ability to anticipate and manage the dynamics of competition will become as important to its financial success as decisions about how to set prices that reflect its differential value.

Many successful companies have suffered huge dents in what was an otherwise smooth trajectory of profitable growth when they failed to anticipate and manage how competitors might react adversely to a pricing decision. In the early 1990s, Alamo Rent A Car (now owned by Enterprise Holdings) was the most profitable (as a percentage of sales) rental car company in America, despite being only the fifth-largest. Its low-cost operating model enabled it to dominate an entire market segment: Leisure rentals for tour packages to places like Disney World in Florida and Disneyland in California. Within those markets, Alamo could essentially set its prices assuming that the prices of larger rental car competitors would remain unchanged. But Alamo’s management was impatient for growth and had the cash to pursue it. Within the United States, a much larger and lucrative rental car segment was business travel originating at airports. Moreover, demand for cars at Alamo locations peaked during holiday periods when the demand from business travelers at airports peaked during non-holiday periods. Thus Alamo’s management figured that if it could win even a small share of the business market by undercutting the rates of the market leaders, Hertz and Avis, Alamo could generate a lot of profitable growth.

That was not to be, for reasons that in retrospect were entirely predictable. As planned, Alamo began moving to on-airport locations beyond its core leisure markets and setting prices that undercut the market leaders. But, Alamo underestimated its own vulnerability. Hertz and Avis had previously shown little interest in serving tour groups which, since they arrive in waves, could create backlogs unacceptable to their valuable business clientele. But once Alamo began attacking their prime markets, it was bound to get their attention. Within two years, Hertz opened the largest car rental facility in the world in Alamo’s most lucrative market—Orlando, Florida. While the long lines at Alamo created a profitable opportunity to earn commissions from selling people tickets to attractions, Hertz’s 66 counters and luggage-transfer stations made the transfer from plane to rental car easier and faster for tourists with lots of stuff in tow. To fill this facility, Hertz began undercutting Alamo’s deals with European tour operators, who proved much more willing to switch suppliers to save a few dollars per car than were Hertz’s business customers that Alamo was trying to woo. That year, Alamo’s profits fell into the red and its operations were sold the following year to another rental car company.22

The lesson here is not that a profitable company should not attempt to grow share. It is that companies must anticipate competitive reactions and avoid competing where they lack the capabilities necessary to profit despite those reactions. This is not to argue that underpricing the competition is never a successful strategy in the long run, but the conditions necessary to make it successful depend critically upon how competitors react to it. The goal of Chapter 7 is to provide guidelines for anticipating and influencing those reactions and integrating them into one’s plan for strategic pricing.

Over the past decade, pricing has risen in importance on the corporate agenda. Most top executives recognize the importance of price and value management for achieving profitable growth. Yet given this strategic importance, it is surprising to us how many firms continue to organize their activities so that pricing decisions are made by lower-level managers who lack the skills, data, and authority to implement new pricing strategies that align with changes occurring across markets. This tactical orientation has financial consequences.

Our research has found that companies that adopted a value-based pricing strategy and built the organizational capabilities to implement it earned 24 percent higher profits than industry peers.23 Yet in that same research, we found that a full 23 percent of marketing and sales managers did not understand their company’s pricing strategy—or did not believe their company had a pricing strategy. This lack of awareness demonstrates the challenges involved when developing a capability for pricing strategy which requires input and coordination across functional areas including marketing, sales, capacity management, and finance.

A successful pricing strategy requires the support of three pillars: An effective organization, timely and accurate information, and appropriately motivated management. In many instances, it is neither desirable nor necessary for a company to have a large, centralized organization to set prices. What is required, however, is that everyone involved in pricing decisions understands their role in the process. So while a product manager might set a price, a centralized pricing organization might have the right to define a process for evaluating the impact of that price or to set a policy for when it can be offered, sales management and operations management might have the right to provide input on particular elements of the process, and senior management might have the right to veto the decision. Too often decision rights are not clearly specified, changing the pricing decision from a well-defined, value-driven process to an exercise in political power, as various functional areas vie to influence the offered price without necessarily considering overall profitability or strategy.

Pricing decision-makers require quality information. Once managers understand their role in the price-setting process, the first thing they generally ask for is more data and better tools. When one considers the data requirements for making organization-wide pricing decisions, this response is not surprising. To make informed pricing decisions, marketing managers need data on customer value and competitive pricing. Sales managers need data to support their value claims and defend price premiums. And financial managers need accurate cost data and volume data. Collecting these large volumes of data and distributing them throughout the organization is a daunting task that has led many companies to adopt price management systems that are integrated with their data warehouses and ensure that managers get only the information they need. While not every firm needs a dedicated system to manage pricing data, everyone must address the question of how to get the right information into the right manager’s hands in a timely fashion if they hope to keep their pricing strategies aligned with changes occurring in their markets.

Successfully implementing a pricing strategy also requires a firm to motivate managers to engage in new behaviors that support the strategy. All too often, people are given incentives to act in ways that actually undermine the pricing strategy and reduce profitability. It is common for companies to send sales reps to training programs designed to help them sell on value, despite paying them solely to maximize volume. When sales reps or field sales managers are offered only revenue-based incentives, it is hard to imagine them fighting to defend a price premium if they think that doing so will increase their chances of losing the deal. However, incentives can be developed that encourage more profitable behaviors.

A senior salesperson we know was recently promoted to regional sales manager for an area in which discounting was rampant. He began his first meeting by sharing a ranking of sales reps by their price realization during the prior quarter. He invited the top two reps to describe how they did those deals so profitably and the bottom two reps to describe what went wrong. He then facilitated an open discussion among the 30 reps on how challenges like those faced by the bottom two reps could be managed better in the future. At the end of the meeting, he told them that this exercise would be repeated every quarter. One month into the subsequent quarter, sales reps were asking to see where they stood in the rankings, suggesting that they were highly motivated to engage in productive behaviors to avoid a low ranking before the next meeting.

Chapter 11 describes in more detail the structural elements that need to be built into an organization to enable it to adopt and implement strategic pricing effectively.

Pricing strategically has become essential to the success of business, reflecting the rise of global competition, the increase in information available to customers, and the accelerating pace of change in the products and services available in most markets. The simple, traditional models of cost-driven, customer-driven, or share-driven pricing can no longer sustain a profitable business in today’s dynamic and open markets.

This chapter introduced the strategic pricing value cascade containing the six key elements of strategic pricing. Experience has taught us that achieving sustainable improvements to pricing performance requires ongoing evaluation of and adjustments to multiple elements of the value cascade. Companies operating with a narrow view of what constitutes a pricing strategy miss this crucial point, leading to incomplete solutions and lower profits. Building a strategic pricing capability requires more than a common understanding of the elements of an effective strategy. It requires careful development of organizational structure, systems, individual skills, and ultimately, culture. These things represent the foundation upon which the strategic pricing value cascade rests and must be developed in concert with the pricing strategy. The first step toward strategic pricing is to understand each level of the cascade and how it supports those above it.

1. Warren Buffett, interview with the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, May 26, 2010.

2. Lucas Shaw, “Apples iTunes Overtaken by Streaming Music Services in Sales,” Bloomberg, March 22, 2016. Accessed at www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-03-22/apple-s-itunes-overtaken-by-streaming-music-services-in-sales.

3. For an overview, in July 2014 the U.S. Department of Transportation published a primer on congestion-based pricing: http://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/congestionpricing/sec2.htm.

4. 82 percent of holiday shoppers will go online for shopping research prior to going to an actual store, Deloitte 2015 Annual Holiday Survey: Embracing Retail Disruption, Deloitte Press, October 2015.

5. Christo Wilson, “If You Use a Mac or Android, e-Commerce Sites May Be Charging You More,” Washington Post, November 3, 2014. Accessed at www.washingtonpost.com/posteverything/wp/2014/11/03/if-you-use-a-mac-or-an-android-ecommerce-sites-may-be-chargingyou-more/?utm_term=.5cdd7d3a2efb.

6. Robert D. Buzzell, Bradley T. Gale, and Ralph G.M. Sultan, “Market Share—A Key to Profitability,” Harvard Business Review (January 1975).

7. Michael E. Raynor, Derek Pankratz, and Selvarajan Kandasamy, “Exceptional Performance: A Nonrenewable Resource” Deloitte Review, 18 (2016), pp. 37–55.

8. Michael E. Raynor and Mumtaz Ahmed, The Three Rules: How Exceptional Companies Think (New York: Penguin, 2013), pp. 111–156.

9. Marco Bertini and Luc Wathieu, “How to Stop Customers from Fixating on Price,” Harvard Business Review (May 2010). Also see Andreas Hinterhuber and Stephan Liozu, “Is It Time to Rethink Your Pricing Strategy?” MIT Sloan Management Review, June 19, 2012.

10. For summaries of a broad range of these anomalies, see Richard H. Thayler, Quasi-Rational Economics (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1994); Daniel Ariely, Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces That Shape Our Decisions, revised and expanded edition (New York: HarperCollins, 2010).

11 . Itamar Simonson and Amos Tversky, “Choice in Context: Tradeoff Contrast and Extremeness Aversion”, Journal of Marketing Research, 29 (August 1992), pp. 281–295.

12. Albert J. Della Bitta and Kent B. Monroe, “The Influence of Adaptation Levels on Subjective Price Perceptions,” in S. Ward and P. Wright (eds.), Advances in Consumer Research, Vol. 1 (Boston, MA: Association for Consumer Research, 1974), pp. 359–369; Robert Slonim and Ellen Garbarino, “The Effect of Price History on Demand as Mediated by Perceived Price Expensiveness,” Journal of Business Research 45 (May 1999), pp. 1–14. Market researchers can suppress this effect when estimating demand by randomizing the order of presentation, but the actual demand will depend upon the actual order of presentation in real markets.

13. Katie Hafner and Brad Stone, “IPhone Owners Crying Foul Over Price Cut,” The New York Times, September 7, 2007.

14. “Gartner Says Five of Top 10 Worldwide Mobile Phone Vendors Increased Sales in Second Quarter of 2016,” Gartner Inc. press release, August 19, 2016. Accessed at www.gartner.com/newsroom/id/3415117.

15. Peter F. Drucker, “The Information Executives Truly Need,” Harvard Business Review (January–February 1995), p. 58.

16. “Global Apple Mac Unit Sales from 1st Quarter 2006 to 3rd Quarter 2016,” Statista. Accessed at www.statista.com/statistics/263444/sales-of-apple-mac-computers-since-first-quarter-2006.

17. Cali Mackrill, “Queensland Resort Offers Discount if it Rains,” The Telegraph, March 28, 2013. Accessed at www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/news/Queensland-resort-offers-discount-if-it-rains.

18. J. T. Gourville, “Pennies-a-Day: The Effect of Temporal Reframing on Transaction Evaluation,” Journal of Consumer Research 24(4) (March 1998), pp. 395–408.

19. The projection process for airline pricing is called “yield management” and is described in Chapter 4.

20. Alistair Osborne, “Ryanair Ready for Price War as Aer Lingus Costs Leap,” The Telegraph, June 2, 2009. Accessed at www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/newsbysector/transport/5431131/Ryanair-ready-for-price-war-as-Aer-Lingus-costs-leap.html.

21. Ryanair Full Year Results Analysts Briefing, June 2, 2009, and “Domestic Bliss: The World’s Largest Airlines,” The Economist, June 24, 2015. Accessed at www.economist.com/blogs/gulliver/2015/06/worlds-largest-airlines.

22. “Rocky Road—Alamo Maps a Turnaround,” Wall Street Journal, August 14, 1995, p. B1; and “Chip Burgess Plots Holiday Coup to Make Hertz No. 1 in Florida,” The Wall Street Journal, December 22, 1995, p. B1.

23. John Hogan, “Building a Leading Pricing Capability: Where Does Your Company Stack Up?,” published by Monitor Deloitte, 2014.