Chapter 8

Creating Text Boxes

IN THIS CHAPTER

Creating text boxes

Creating text boxes

Working with the shape and appearance of a text box

Working with the shape and appearance of a text box

Linking and unlinking text boxes

Linking and unlinking text boxes

Importing and exporting text

Importing and exporting text

Working with word processing applications

Working with word processing applications

QuarkXPress began its life almost 30 years ago with just three kinds of page items: text boxes, picture boxes, and rules (lines). Aside from some additional features to keep up with design trends and new media, it’s still all about text, pictures, and rules. If you master these items, you’ll have a lot more fun designing layouts.

Among the three, you’ll spend the vast majority of your time building text boxes and formatting text. This chapter takes you through building text boxes, linking text boxes, and importing text (and offers a little guidance with exporting text as well). When you’re ready to learn all about formatting text, turn to Chapters 9 and 10.

Understanding Why You Need Text Boxes

QuarkXPress is not a word processor. It has many of the features of a word processor, but it is so much more. A word processor creates documents that are essentially one long column of text, perhaps with some pictures inserted into it. Any document as complex as a magazine consists of multiple stories, in multiple locations on the page, with multiple areas of color and pictures. Pick up any magazine and ask yourself, “How would I create this in Microsoft Word?” The answer, of course, is you wouldn’t. You need a tool like QuarkXPress to arrange those items into a layout.

If you like, you can think of each story in a QuarkXPress layout as a separate word processing document. (In fact, each story often begins its life as a word processing document that is imported into a text box.) Logically, you need a separate text box — or chain of linked text boxes — for each story.

Deciding Which Is Best: Manual or Automatic?

The most common way to create a text box is to use the Text Content tool to drag out an area on a page to contain your text. You can then optionally link several text boxes together so that if your text is too long to fit into the first one, it will flow into the others. If you're creating a short document, such as an ad, a brochure, or even an article in a magazine, creating and linking text boxes can be a fun and satisfying way to work. (Text that doesn't fit into a text box is called overset text.)

However, if you're building a long document, such as an entire book or a chapter in a book, you can tell QuarkXPress to automatically add new pages and text boxes as the length of text grows. QuarkXPress links these new text boxes to your current text box, and the new text boxes magically appear whenever you type more text than fits into your current text box (or import text from a text file).

To learn all about automatic text boxes and the master pages that control them, jump back to Chapters 4 and 5. To understand how to manually create text boxes and link them to other text boxes, read on.

Creating a Text Box Manually

Creating a text box is as easy as can be — which is handy because you'll do it 100 million times, or at least as many times as you create new layouts. Just follow these steps:

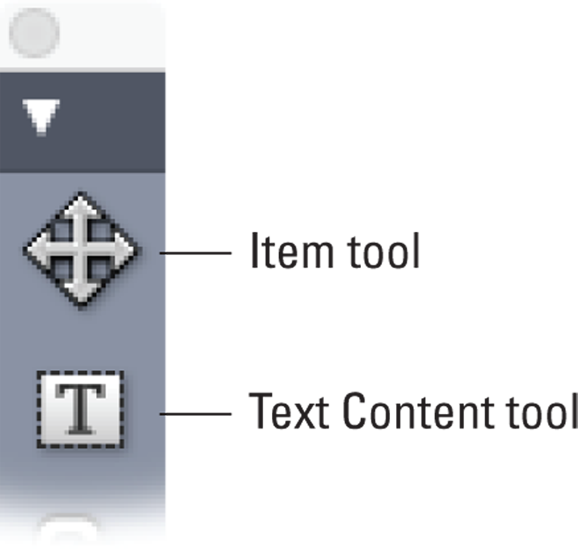

- Select the Text Content tool from the Tools palette, as shown in Figure 8-1.

The Text Content tool is a rectangle with a capital T in its center.

When you move the mouse pointer into the layout page, the mouse pointer changes to look like a crosshair.

- Hold down the mouse button and drag the mouse across your page until you’ve drawn a text box the size you want.

Height and Width dimensions appear at the bottom right of the text box as you size it. They also appear in the Measurements palette.

Conveniently, alignment guides and dimension arrows appear on the edges of your text box whenever they align with the edges or centers of other items on the page. These guides and arrows also appear when your text box’s text columns or gutters align with those in another text box.

- Release the mouse button.

You don't need to worry about the exact size and position as you're creating the new text box. Later, you can drag the text box's side handles or corner handles to adjust its size and position, or use the Item tool to drag the text box around on the page — or even to another page. You can also enter precise measurements into the Measurements palette for the box’s location (labeled X: and Y: for horizontal and vertical position, respectively) and size (labeled W: and H: for width and height).

You don't need to worry about the exact size and position as you're creating the new text box. Later, you can drag the text box's side handles or corner handles to adjust its size and position, or use the Item tool to drag the text box around on the page — or even to another page. You can also enter precise measurements into the Measurements palette for the box’s location (labeled X: and Y: for horizontal and vertical position, respectively) and size (labeled W: and H: for width and height).

Smart designers use a grid to determine where to place page items. Using a grid not only ensures that your page items line up with each other and appear to be part of a cohesive whole but also frees your brain to focus on more creative stuff. I tell you how to create and use grids in Chapter 2.

Smart designers use a grid to determine where to place page items. Using a grid not only ensures that your page items line up with each other and appear to be part of a cohesive whole but also frees your brain to focus on more creative stuff. I tell you how to create and use grids in Chapter 2.

Changing the Shape and Appearance of a Text Box

When a text box is active (click it with the Text Content tool or the Item tool to activate it), you can use the controls in the Text Box tab of the Measurements palette to adjust all kinds of its attributes, as described in the following sections.

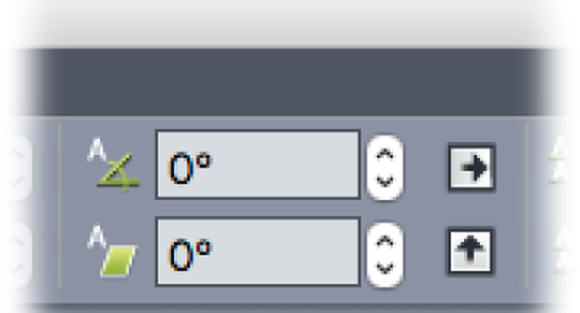

Changing the box angle and skew

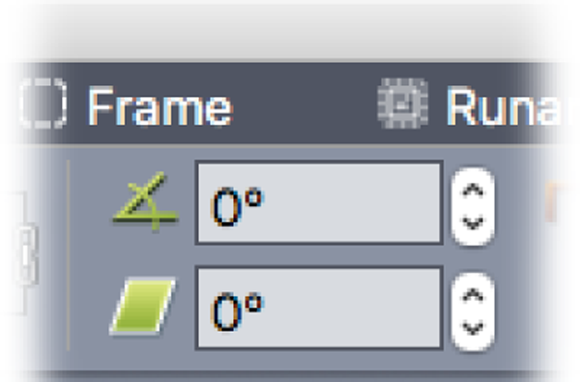

To rotate a box to a precise angle, enter that angle (in degrees) into the Box Angle field. You can also rotate the box by clicking the up and down arrows next to the Box Angle field. Figure 8-2 shows the Box Angle field.

To rotate a text box visually, get the Item tool or the Text Content tool and mouse over to just outside a corner of the box. The pointer changes to a curved arrow, and if you click and drag around the outside of the text box, it rotates. Release your mouse button when you’re satisfied with the position. (The Box Angle field in the Measurements palette updates to indicate the new angle.)

You can also skew the text box as if you’d pushed its top corner to the left or right; the text inside skews along with the shape of the box. This is usually not an attractive effect (yuck!), but should you need to do it, either enter an angle amount into the Box Skew field in the Measurements palette or click the up and down buttons next to it. Figure 8-2 shows the Box Skew field.

Changing the box corner shape

To change the shape of the box's corners, hold your mouse button down on the Box Corner Shape control (it looks like an orange box corner) and choose one of the following options: Rectangle, Rounded, Concave, and Beveled. To control how far the corner intrudes on the text box, use the Box Corner Radius control to the right of the Box Corner Shape control. You can either type in a number or click the up and down arrows to increase or decrease the radius of the corner, respectively. Figure 8-3 shows the Box Corner Shape field.

Changing the box color and opacity

Every box in QuarkXPress has a background color (even if it’s None), and that color can have any level of opacity (or transparency). It can also blend from one color to another in various ways. You can read all about color control in Chapter 11; then you can apply your knowledge to the controls shown in Figure 8-4.

Adding frames and drop shadows

A text box is just like any other box, so you can add various kinds of striped, dashed, and dotted frames to it (see Chapter 3 for more about frames) as well as an impressive drop shadow on either the text itself, the box, or both (see Chapter 13 for more about drop shadows).

Creating other text box shapes

In QuarkXPress, any box can be a text box, even if it began its life as something else. For example, you can put text in any of the following:

- A picture box

- A rectangular (no content) box

- An oval (no content) box

- A starburst

- A shape created by ShapeMaker

- A freeform shape

Chapter 3 explains how to create all these kinds of boxes. The secret to converting one of them into a text box is this: With the item active, choose Item ⇒ Content ⇒ Text. This converts the item to a text box, and you can then type or import text into it.

Controlling the Position of Text in Its Box

The text in each text box has a relationship to its box in much the same way that page items have a relationship with the page. You can control the number of columns of text in the box, the text’s nearness to the edge of the box, whether the text aligns to the top or the bottom of the box, and more. Read on to discover the various ways your text and its box can relate to each other.

Setting the columns and margins of a text box

The text in each text box can have its own number of columns, margin between the columns, and inset from the edge of the box. (These settings are separate from the margins and columns of your layout page and apply only to the active text box.) Use the Columns control to choose how many columns of text you want in your text box, and the Gutter Width control to adjust the space between the columns, as shown in Figure 8-5.

Vertically aligning the text

Your text doesn’t have to be glued to the top of the box; it can be attached to the bottom (leaving room at the top), float in the center of the box, or stretch out to fill its height. Figure 8-6 shows the text alignment options. If you choose Justify, QuarkXPress adds space between paragraphs to fill the box, and you can specify the maximum amount of space you want in the Inter Paragraph Maximum field.

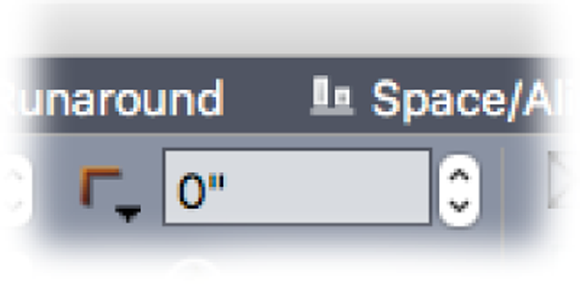

Setting the inset of a text box

In QuarkXPress, the text inside a text box never bumps into the edge of the box — it’s always inset a tiny amount. Sometimes, such as when a text box is filled with a color or has a frame around it, you may want to increase the amount of inset so that the text isn’t cramped by the frame or appear to be pushing its way off the background. To increase the amount of inset, use the Inset controls, shown in Figure 8-7.

For a uniform amount of inset on all sides, enter an amount in the first text inset field. To apply a different inset to various sides, click the Multiple Insets check box and then enter amounts for each side.

Where should the text start?

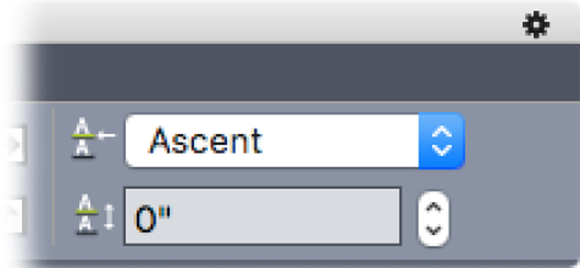

You can also control the vertical position of your first line of text in the box. Sometimes a font is so tall that it sticks its neck out of the top of the box, interfering with what’s above it. Or maybe you used a big font in one box and a smaller font in a box next to it, but you need their first lines of text to line up in both boxes. That’s where the controls in Figure 8-8 can save you.

The top control (named First Baseline Minimum) has three options: Cap Height, Cap + Accent, and Ascent. Because not all font designers follow the same rules, you may need to try each of them to achieve the result you want.

The lower control (named First Baseline Offset) simply nudges all the text up and down in the box. Depending on the font and font size, you may need to enter a large number before you see a change.

Setting the text angle and skew

You can achieve some creative text effects by changing the angle of the text within the box (for example, to make it look as though it’s marching uphill), or by skewing the text (so that it’s leaning over). Figure 8-9 shows the text angle and skew controls.

Linking and Unlinking Text Boxes

When you have more text than will fit into one text box and you want it to continue in another, it’s time to link the boxes together into one long story. For example, newsletter and magazine stories often begin on one page and continue on another (and another). You use the Linking tools to flow a story from one text box to others.

Linking text boxes

To link two text boxes together use the Text Linking Tool, follow these steps:

-

Create two or more empty text boxes.

You can’t link text boxes that already contain text. To do that, you use the Linkster utility (see the “Using Linkster” section, later in this chapter).

You can’t link text boxes that already contain text. To do that, you use the Linkster utility (see the “Using Linkster” section, later in this chapter).

-

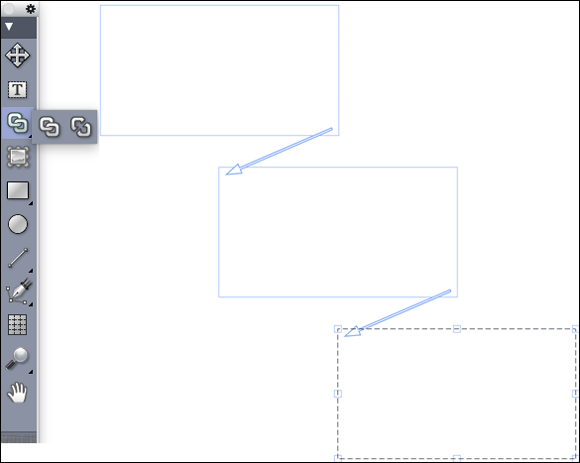

Get the Text Linking Tool shown in Figure 8-10.

As you move your mouse over any text box, your pointer changes to a chain link. (You may have to wiggle your mouse to see it.)

-

Click the first text box.

The outline of the text box changes to marching ants.

-

Click the next text box you want to add to the chain.

A hollow arrow appears, attached to the bottom-right corner of the first box and pointing to the top-left corner of the second box, as shown in Figure 8-10.

-

Click the next text box you want to add to the chain.

Repeat to link to additional boxes.

- To end the linking process (after you click the last text box you want to add to the chain), do one of the following:

- Click anywhere in your document where there isn’t a text box.

- Click on another tool in the Tools palette.

- Press the Esc key on your keyboard.

When working with text in linked boxes, you can force the text after your text insertion point to start in the next text box by using the Next Box character. To type a Next Box character, hold down the Shift key and press the Enter key on your keyboard’s numeric keypad. (On a Mac that doesn’t have an extended keyboard, hold down the fn key and press Shift-Return.) Similarly, you can force text to start in the next column in a multicolumn text box by pressing the Enter key on your numeric keypad (or fn-Return on a Mac keyboard that doesn’t have a numeric keypad). You can find more keyboard tricks like this in the Cheat Sheet f0r this book (go to

When working with text in linked boxes, you can force the text after your text insertion point to start in the next text box by using the Next Box character. To type a Next Box character, hold down the Shift key and press the Enter key on your keyboard’s numeric keypad. (On a Mac that doesn’t have an extended keyboard, hold down the fn key and press Shift-Return.) Similarly, you can force text to start in the next column in a multicolumn text box by pressing the Enter key on your numeric keypad (or fn-Return on a Mac keyboard that doesn’t have a numeric keypad). You can find more keyboard tricks like this in the Cheat Sheet f0r this book (go to www.dummies.com and search for QuarkXPress For Dummies Cheat Sheet).

Unlinking text boxes

You can easily click the wrong box when using the Text Linking Tool. To fix your mistake and break the link between two text boxes, use (surprise!) the Text Unlinking Tool and follow these steps:

-

Get the Text Unlinking Tool.

Press and hold on the Text Linking Tool to show the Text Unlinking Tool and then slide over onto it to make it your active tool.

-

Click any text box in the chain.

Arrows appear that connect the boxes.

-

Click the head or tail of an arrow to break the chain at that location.

If you click the pointy head of the arrow, the box it was pointing into remains selected. If you click the tail of the arrow, the box it came from remains selected.

If those boxes had text in them, the story stops flowing where you unlinked them and remains in the box(es) in the chain ahead of where you unlinked it.

If you’re having trouble clicking exactly on the arrow head or tail, try zooming into your layout for a closer look.

If you’re having trouble clicking exactly on the arrow head or tail, try zooming into your layout for a closer look.

Copying linked text boxes

Copying linked text boxes is fraught with peril, unless you remember this simple rule: All the text downstream from the box(es) that you copy comes along for the ride. For example, if you have three boxes and you copy box number two, the copy will include box two and all the text inside boxes two, three, four, and so on. If you copy boxes two and three, the copy will include those two boxes and all the text inside boxes four, five and so on.

Deleting linked text boxes

If you delete a linked text box from the middle of a chain, QuarkXPress reflows the story as if the box was never there. For example, if you delete box number two, the story flows from box one to box three.

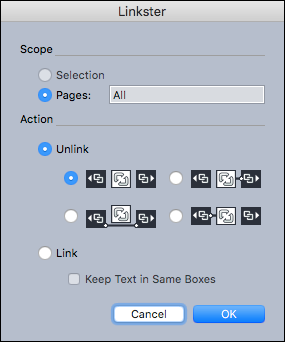

Using Linkster

If all this linked-box logic makes your head swim, or you need to creatively link and unlink text boxes in ways that QuarkXPress normally doesn’t allow, try using the Linkster utility, available in the Utilities menu and shown in Figure 8-11.

You can use Linkster to

- Link text boxes that already have text in them

- Unlink text boxes while maintaining the text already in them

- Unlink text boxes across multiple pages

To use Linkster, first select one or more linked text boxes and then choose Utilities ⇒ Linkster. In the Linkster dialog box, choose a scope — either your selected text boxes or all the text boxes on your choice of pages. Then choose an action — either Unlink or Link.

Linkster has no Undo command, so before using Linkster, always save your document so that if the results aren’t what you expect, you can choose File ⇒ Revert to Saved. You can then return to your document as it was before you used Linkster.

Linkster has no Undo command, so before using Linkster, always save your document so that if the results aren’t what you expect, you can choose File ⇒ Revert to Saved. You can then return to your document as it was before you used Linkster.

Using Linkster for Unlinking

The Unlinking action has four choices:

- Top left creates three or more stories: If you select all the linked text boxes before opening Linkster, this option unlinks all the boxes while maintaining the existing text within each one. If you select fewer than all the linked text boxes, it creates three stories: one for the boxes before the selected boxes; one for the selected boxes; and one for the boxes after the selected boxes.

- Bottom left creates two stories: One for the boxes before and after the selected boxes, and one for the selected boxes.

- Top right creates two stories: One for the boxes before the selected box and the selected box, and one for the boxes after the selected box.

- Bottom right creates two stories: One for the boxes before the selected box, and one for the selected box and the boxes after the selected box.

A story is one or more text boxes that contain text.

A story is one or more text boxes that contain text.

Using Linkster for Linking

The Link action links text boxes, even if they already contain text. If Pages is enabled in the Scope section at the top of the dialog box, only those boxes that have been unlinked by Linkster will be relinked. If Selection is enabled, Linkster tries to link the selected boxes in the order you selected them.

Click Keep Text in Same Boxes to keep the existing text in their original boxes after linking. Otherwise, the text from all the boxes is combined into one story that flows from the first box through all the other linked boxes — usually not landing where they originally were.

Importing Text

Although typing text into QuarkXPress is easy (it behaves very much like Microsoft Word), you can also import text from word processing documents and other applications in several ways, including the following:

- Choose File ⇒ Import and select a text document.

- Drag a text file from the file system onto a text box.

- Copy and paste text from another application onto a text box.

- Drag text from another application onto a text box.

The following sections explain how to get text into a text box using each of these techniques.

Importing text from a word processing document

The most common way by far to import text is from a document created in Microsoft Word or another word processing application. To do so, follow these steps:

- Select the Text Content tool.

- Place the text insertion point where you want text to be inserted in the text box.

- Choose File ⇒ Import and navigate to the word processing document.

-

Click the Open button.

The text from the word processing document is imported into the text box.

This File ⇒ Import technique is popular for one reason: QuarkXPress can clean up and apply style sheets to the text as it’s imported. In the Import dialog box, click the Options button to see the following options, as shown in Figure 8-12:

- Convert Quotes: Select this option to convert double hyphens to em dashes and convert foot or inch marks to a typesetter's apostrophes and quotation marks. This makes your text look much more professional.

- Include Style Sheets: Select this option to import style sheets from the Microsoft Word document. (See Chapter 10 for more on using style sheets.) All style sheets used in the Word document are added to the QuarkXPress document, and you’re presented with options for handling duplicate names. This option also converts XPress Tags to formatted text. See the “Using XPress Tags” sidebar, later in this chapter, for more about XPress Tags.

Windows users: If you find yourself importing a lot of text files or picture files from the same folder or directory on your computer, you can tell QuarkXPress to always start from that folder or directory when opening the Import dialog box. To do that, open the QuarkXPress Preferences by choosing Edit ⇒ Preferences. In the Default Path pane, choose the folder you want to use.

Windows users: If you find yourself importing a lot of text files or picture files from the same folder or directory on your computer, you can tell QuarkXPress to always start from that folder or directory when opening the Import dialog box. To do that, open the QuarkXPress Preferences by choosing Edit ⇒ Preferences. In the Default Path pane, choose the folder you want to use.

The Mac OS X version of QuarkXPress 2015 and higher no longer supports the Microsoft Word file format with the .doc filename extension. To import a Word document, it must be saved in the .docx format that has been standard since Microsoft Word 2007. The Windows version is still able to import a .doc file.

The Mac OS X version of QuarkXPress 2015 and higher no longer supports the Microsoft Word file format with the .doc filename extension. To import a Word document, it must be saved in the .docx format that has been standard since Microsoft Word 2007. The Windows version is still able to import a .doc file.

To avoid problems importing Word documents, click the Office button, open the Word Options dialog box, click the Save tab, and deselect Allow Fast Saves in Microsoft Word or use the Save As command to create a copy of the Word file to be imported. (Your instructions might differ, depending on your version of Microsoft Word.)

To avoid problems importing Word documents, click the Office button, open the Word Options dialog box, click the Save tab, and deselect Allow Fast Saves in Microsoft Word or use the Save As command to create a copy of the Word file to be imported. (Your instructions might differ, depending on your version of Microsoft Word.)

Dragging a text file from the file system

On Mac OS X or Windows, rather than following the File ⇒ Import approach described in the preceding section, you can drag the text file from your computer’s desktop into an empty text box. The hardest part is arranging your windows so that you can see the text box at the same time that you see the text file!

If the box you select is a picture box or a no-content box instead of a text box, you can convert it to a text box and import text into it by pressing Command (Mac) or Ctrl (Windows) while dragging the text file from the file system onto it.

If the box you select is a picture box or a no-content box instead of a text box, you can convert it to a text box and import text into it by pressing Command (Mac) or Ctrl (Windows) while dragging the text file from the file system onto it.

Dragging text from another application

If your text is already open in another application, you can drag text from the other application into a text box in QuarkXPress. Of course, you need to be able to arrange your windows so that you can see your QuarkXPress document and your other document, which may not be easy!

If the box you select is a picture box or a no-content box instead of a text box, you can convert it to a text box and import text into it by pressing Command (Mac) or Ctrl (Windows) while dragging the text from the other application into it.

If the box you select is a picture box or a no-content box instead of a text box, you can convert it to a text box and import text into it by pressing Command (Mac) or Ctrl (Windows) while dragging the text from the other application into it.

If you drag content into a box that already contains text or a picture, QuarkXPress creates a new box for the dragged content. To replace the content of the box instead, press Command (Mac) or Ctrl (Windows) while dragging the content to the box. To always create a new box for dragged-in content, press Option (Mac) or Alt (Windows) while dragging.

If you drag content into a box that already contains text or a picture, QuarkXPress creates a new box for the dragged content. To replace the content of the box instead, press Command (Mac) or Ctrl (Windows) while dragging the content to the box. To always create a new box for dragged-in content, press Option (Mac) or Alt (Windows) while dragging.

Exporting Text

So your client doesn’t have QuarkXPress and wants the text from the project you’ve created. You could copy and paste it into a word processor, or you could save a step and export it directly from QuarkXPress. (Who wants to muck around in a word processor, anyway?) Here’s how export text directly from QuarkXPress:

- Select a text box or some text in a text box.

- Choose File ⇒ Save Text and navigate to a location to save the file.

- From the Format menu, choose either Plain Text, XPress Tags, Rich Text Format, Word Document, or HTML.

-

Name your file and click Save.

A new file appears in the location you selected, with its text formatted just as it was in QuarkXPress!

QuarkXPress doesn’t export RTF (Rich Text Format) files as well as it could. Always test your exported RTF file by attempting to open it in a word processor. If it fails, export the text again, this time choosing Word Document as the format, open that document in Microsoft Word (or another application that can open a .docx file), and save it again in RTF format. Sad but true.

QuarkXPress doesn’t export RTF (Rich Text Format) files as well as it could. Always test your exported RTF file by attempting to open it in a word processor. If it fails, export the text again, this time choosing Word Document as the format, open that document in Microsoft Word (or another application that can open a .docx file), and save it again in RTF format. Sad but true.

Creating text boxes

Creating text boxes Working with the shape and appearance of a text box

Working with the shape and appearance of a text box Linking and unlinking text boxes

Linking and unlinking text boxes Importing and exporting text

Importing and exporting text Working with word processing applications

Working with word processing applications

You don't need to worry about the exact size and position as you're creating the new text box. Later, you can drag the text box's side handles or corner handles to adjust its size and position, or use the Item tool to drag the text box around on the page — or even to another page. You can also enter precise measurements into the Measurements palette for the box’s location (labeled X: and Y: for horizontal and vertical position, respectively) and size (labeled W: and H: for width and height).

You don't need to worry about the exact size and position as you're creating the new text box. Later, you can drag the text box's side handles or corner handles to adjust its size and position, or use the Item tool to drag the text box around on the page — or even to another page. You can also enter precise measurements into the Measurements palette for the box’s location (labeled X: and Y: for horizontal and vertical position, respectively) and size (labeled W: and H: for width and height).

You can’t link text boxes that already contain text. To do that, you use the Linkster utility (see the “

You can’t link text boxes that already contain text. To do that, you use the Linkster utility (see the “

A story is one or more text boxes that contain text.

A story is one or more text boxes that contain text.