LUCKILY FOR us, there is a seemingly endless variety of yarns on today’s market. However, with this diversity comes the matter of choice — which yarn is best for which types of projects? Understanding the characteristics of various yarns will help you determine the answer.

Q What is yarn made of?

A Animal, plant, and synthetic fibers are all used to make yarn. The animal fibers include silk produced by worms, wool from sheep, alpaca from alpacas, quiviut from the musk ox, angora from rabbits, and mohair from angora goats (go figure!). Plant fibers include cotton from cotton bolls, linen from the flax plant, and ramie from an Asian shrub. There are also yarns made from soy, bamboo, pine, and other plants. Acrylic, nylon, polyester and other synthetic fibers are man-made, in some cases from recycled materials. Lyocell (Tencel) and rayon are man-made fibers produced from cellulose, which is a natural material. “Metallic” yarns are usually a synthetic, metallic-looking fiber spun with another fiber.

Q What are some of the common terms used to describe yarn characteristics?

A All of the following terms will help you understand and describe the yarns you work with: Absorbency. The ability of the fiber to take in water Breathability. The ability of the fiber to allow air to pass through it

Dyeability. The ability of the fiber to accept and hold dye

Hand/handle. The way a fiber feels, a tactile description that may include words like: soft, fine, harsh, stiff, resilient. The hand of a fiber influences the hand of the fabric that it is made into; the fabric might additionally be described by its “drape.”

SEE ALSO: Pages 164–65, fordrapeability.

Loft. The amount of air between the fibers; lofty yarn is usually lighter in weight than its thickness implies. “Fuzzy” yarn is lofty.

Resiliency (elasticity). The ability of a fiber to return to its original shape after being stretched or pulled.

Thickness. The diameter of the fiber, measured in tiny units called microns.

Q Why does fiber content matter?

A A yarn’s characteristics, such as its resiliency, hand, loft, absorbency, and dyeability, are largely determined by the fibers that make up that yarn. Knowing the fiber content of a yarn is also important when it comes time to launder your finished project.

Being familiar with the features of different fibers helps you make appropriate selections when you choose yarn for a project. You might decide, for instance, that while a luxurious alpaca throw is an excellent choice for your mother, a washable acrylic-blend yarn is a more suitable choice for your four-year-old son’s afghan.

Q What are fiber blends?

A Often fibers are blended to take advantage of the best properties of each one. For example, acrylic might be blended with wool to make the yarn machine washable, while maintaining the breathability of the wool fiber. A 50% alpaca/50% wool blend maintains the luxurious feel of the alpaca but is more affordable and more resilient than a 100% alpaca yarn.

The fiber with the higher percentage of content in the yarn dominates the yarn’s characteristics. A 80% cotton/20% wool blend looks like a cotton yarn, but is lighter weight than a similar, all-cotton yarn would be.

A The initial processing depends on the fiber. Wool, mohair, and alpaca are shorn from the animals, resulting in a fleece made up of staples (short strands similar to locks of hair). Angora rabbits are combed or clipped to remove their hair. Cotton bolls that look somewhat like the cotton balls in your bathroom cabinet are harvested from cotton plants and processed through a gin to remove the seeds. Silk comes off the cocoon of a silkworm in a continuous filament; these filaments may be cut into manageable lengths before they are processed. To make rayon, cellulose from wood or cotton is processed into a solution called viscose and then extruded through tiny nozzles to form the rayon fiber. Tencel is a cellulose product made from tree pulp, processed in an environmentally friendly manner. Other man-made fibers are produced in a single, long filament, but are often cut into staple-like lengths before spinning to more closely resemble the properties of natural fibers.

Before the fibers are spun into yarn, they are combed or carded in order to align the fibers. At this point, they may be blended with other fibers. The fibers are then spun together into an S twist or a Z twist, depending on which way they are turned. The twisted strand, or ply, is spun with one or more other plies in the opposite direction to make a multi-plied yarn. Plying fibers adds strength and balance to the yarn. Some-times the plying step is omitted, however, resulting in a yarn made of one twisted strand, known as singles.

‘S’ twist & ‘Z’ twist

2-ply yarn

3-ply yarn

Most commercial yarns are spun by machine, but you may also be able to find some lovely handspun yarns. Dyeing may take place at any part of the process—before the yarn is processed (referred to as dyed in the fleece), as carded/combed fibers, or as finished yarn.

Q What are the characteristics of wool that make it so very popular?

A Wool is warm, insulating, resilient, breathable, water-repellent, dirt-resistant, and naturally flame retardant, and it takes dye well. Different breeds of sheep yield wool with different characteristics. It is weaker wet than dry, but it can absorb up to 30% of its weight in moisture without feeling wet. It may felt if subjected to heat, moisture, and friction. Some manufacturers make wool machine washable by treating it to the “superwash” process.

Q What are the best-known characteristics of cotton?

A Cotton is inelastic, heavy, absorbent, non-insulating, and takes dye well. It has a tendency to stretch, although it may also shrink when washed. It is usually machine washable and is stronger wet than dry.

Q What makes mohair so appealing?

A Mohair is durable, resilient, strong, and soil-resistant. It accepts dye well and is very warm for its weight. The staples are long and lustrous.

Q What are the characteristics that make synthetics so useful?

A The range of synthetic fibers is so vast that it is necessary to generalize. Manufacturers continually attempt to make synthetic yarns that mimic the best properties of the natural fibers. Synthetics are usually durable, water-resistant, strong, non-breathable, non-wicking, and non-insulating. Many synthetics are machine washable. Most are very sensitive to heat, and melt or burn at fairly low temperatures. Synthetics are well-suited for the many currently popular novelty yarns.

Q What is the difference between yarn and thread?

A Crocheters use both terms, sometimes interchangeably. Thread is generally thinner, and made from cotton, silk, or linen. It is often used for bedspreads, doilies, and lace. Yarn is everything else! In this book, I use the word “yarn” for both, unless otherwise stated.

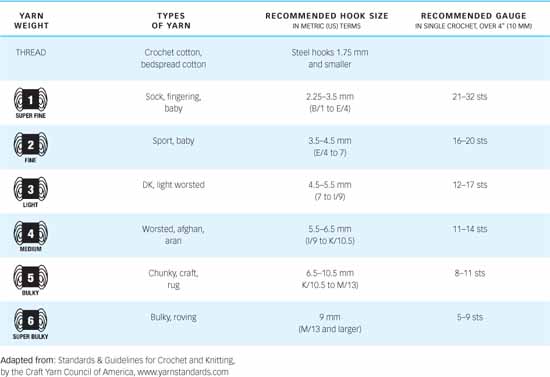

Q How is yarn size described?

A For years, publishers and yarn manufacturers have attempted to come up with meaningful classifications for the size of yarns, and knitters and crocheters have attempted to pigeonhole yarns into these classifications.

Most recently, weight has been the determining factor, but we must be careful with the term weight, because it is used in this case to mean thickness, or the yarn’s diameter. (Yarn diameter is also called grist.) In reality, how much a yarn actually weighs is less meaningful than its diameter and loft. The diameter of the yarn is one of the most important words we can use in effectively describing yarns, yet we still call it weight. Some yarns like brushed mohair, however, have a relatively small diameter compared to its loft — the amount of air between the fibers, or the amount of space the yarn occupies. In other words, the fuzzy bits of the mohair make it a heavier “weight” yarn than it would be without fuzziness.

The table on the following pages gives the generally accepted yarn types in the United States. In the United Kingdom and other countries, the same names may refer to different sized yarns, or you may run into different terms altogether.

Q How is thread size described?

A Thread is generally described in numbers ranging from a superfine, truly threadlike size 100 to a more yarn-like size 3. The higher the number, the smaller the diameter of the thread. Thread may also be categorized by the number of plies. Some threads are more tightly spun than others. Many cotton yarns are mercerized or subjected to a chemical treatment that adds strength and luster.

Q How is yarn packaged?

A Yarn is sold in put-ups of skeins, balls, or loose hanks (also called skeins). A hank (or skein) of yarn is loosely wound, usually from a reel or swift, then tied in several places. You must wind it into a ball before working with it. Balls and commercially wound skeins are neatly wound packages that you can use immediately. The weight of the put-up varies, but is commonly 1.75 oz (50 g) or 3.5 oz (100 g). You may find synthetic yarns put up in larger quantities.

Q What information can I find on the yarn band?

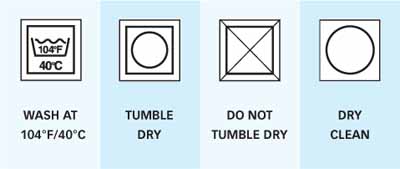

A Whether packaged in skeins, balls, or hanks, most yarn or thread is labeled with information on the fiber content; suggested gauge; weight and/or yardage of the skein, ball, or hank; laundering instructions; dye lot; color number; and possibly a color name. Suggested crochet hook and knitting needle sizes and gauge are also often included.

Q What do all those symbols on the yarn band mean?

A These are international symbols that provide the information described in the previous answer, even if you can’t read the language on the band. The symbols are especially helpful if you purchased an imported yarn. Information on the suggested gauge and hook/needle sizes may also be shown in graphic form.

SEE ALSO: Page 300, for more on yarn care symbols.

A Yarns are dyed together in large batches or dye lots of the same color. Each dye lot is numbered, so you can tell if two skeins of yarn were dyed at the same time in the same batch. There can be subtle or not-so-subtle differences between dye lots.

Q Does dye lot really matter?

A Many times it matters a great deal. Even if the dye lot differences are not apparent in the packaged ball or skein, they often show up in the finished project. Whether it matters on your project depends on how close together you use same-color yarns of different dye lots in the garment. If they are adjacent, you probably shouldn’t mix them, as even subtle dye lot differences show. However, if the yarns are separated by another color, it is probably safe to mix dye lots in the same item.

When purchasing yarn for a project, your best bet is to be sure that all of the same-color yarn comes from the same dye lot.

Q How do I know if the yarn colors I’ve chosen will look good together?

A In the store, hold them together and squint. Try to do this in daylight, not under fluorescent lighting. At home, wrap each of the colors around a white index card side by side, in the same proportions that you will use them in the finished project. Look at the card critically. Are the colors pleasing together or is one of them jarring? Can you put them next to each other in any order? Is there one that shouldn’t be adjacent to another? If you are satisfied with the results on the index card, try all the colors together in a swatch.

SEE ALSO: Pages 124–25, for swatching.

Q I found the perfect color, but my yarn store doesn’t have enough skeins from the same dye lot to complete my project. Do I ever dare use different dye lots in the same project?

A Try some of these ideas for minimizing problems when using different dye lots:

Separate the different dye lots with a stripe of a different color.

Switch stitch patterns where the dye lots change. Often a difference in texture can hide a slight color change.

Make the odd dye lot a separate element, such as a pocket, collar, or border.

Work a chain stitch or other surface embellishment over the spot where the dye lots meet.

Q Why are some yarns labeled “No Dye Lot”?

A These are synthetic (man-made) yarns. The chemical process allows producers to get exactly the same color results every time they produce a fiber in a particular color.

Q Can I use a different yarn than the pattern calls for?

A Yes, but you’ll need to use a yarn similar to the one the pattern calls for to get similar results.

Q How do I find a substitute yarn?

A Start by noting what you know about the original yarn. What weight is it? What gauge does the pattern call for? What is the suggested hook size?

Next, look at the yarn you’d like to substitute and make sure it is the same weight as the original yarn. (Remember, I’m not referring to how much it weighs, but rather the weight classification.) The yarn band gives you the suggested gauge and hook size for the new yarn.

You may also want to consider other characteristics of the original yarn. What is the fiber content? Is it a plain yarn? Fuzzy? Smooth? Fluffy? Stiff? Tightly or loosely spun? A loosely spun yarn or a singles yarn will look different from a yarn with a tighter twist, even if they are the same weight. If you are not able to determine these characteristics from the description in the pattern, you may have to infer the information from a picture. These are just some characteristics to consider, however. You may not mind if the substitute yarn is not exactly the same as the original.

Because of their unique properties, novelty yarns may be tricky to substitute in a pattern. If you are unsure, check with a knowledgeable sales clerk where you buy your yarn.

Q My pattern calls for 3-ply wool. Will any 3-ply wool be sufficient?

A Not necessarily. In the past, yarns were often categorized according to the number of plies. This worked because there were a limited number of commercially available yarns, and everyone understood a 3-ply yarn to be of a certain diameter. These days, it is not sufficient to describe yarns by ply alone, as some multi-ply yarns are very fine and some singles are ultra bulky. You’ll need to determine the weight classification of the original yarn and choose an appropriate substitute.

SEE ALSO: Page 34 for yarn weight classifications.

Q Can I buy yarn by weight?

A If you’re referring to its weight classification, then the answer is, “yes.” If you mean you want to figure the amount of yarn you need to buy based on how much each skein weighs, then the answer is, “bad idea.” Buying by skein weight is another holdover from the past, when most yarns were wool and of a fairly uniform size. Length (yardage) is what matters, not how much the yarn weighs. Cotton yarn weighs more per yard than wool; some wools weigh more per yard than others. If yardage is not listed on the ball band, see if you can determine it from other sources so that you buy yarn for your project.

Q Can I use two lighter weight yarns together to make a heavier yarn?

A Yes, but you’ll have to work a gauge swatch to see if you can get the correct gauge. To get off on the right foot, try using this rule of thumb: Add the suggested gauge of each of the two yarns and divide by 3 for the suggested gauge of the two yarns held together.

For example: Using two strands of sport-weight yarn with a suggested gauge of 4 sc = 1″ (2.5 cm), double the gauge of the yarn and divide by 3:

(4 × 2) ÷ 3 = 2.67 sc = 1″

If the gauge you are expecting to use is in the ballpark of 2.5 sc = 1″, then you might be able to use those two strands of sport-weight yarn together. Don’t forget that you’ll need a larger hook than you would for a single strand of sport-weight yarn. You’ll probably start with the hook size listed in the pattern instructions. Swatch with your proposed yarn and hook to see how close you are. If you are using a yarn doubled, remember that you’ll also have to double the amount of yardage called for in the pattern!

SEE ALSO: Pages 124–25, for swatching.

Q If I’m substituting yarn, how much do I buy?

A Figure out how much yardage you need by multiplying the number of skeins the pattern calls for by the number of yards per skein of the original yarn. You should be able to find this information in the pattern instructions. Once you know the total yardage you need for your project, divide that number by the number of yards per skein in the yarn you want to use. You’ll probably get a fraction. Be sure to round up since you cannot buy a fraction of a ball of yarn.

For example: My pattern calls for 8 skeins of Pretty Yarn (100% acrylic, 200 yds/100 g). I want to use Beautiful Yarn (100% wool, 150 yds/100 g) instead. Here’s the math:

8 skeins × 200 yards = 1600 yards

1600 yards ÷ 150 yards = about 11 balls

You may want to buy one additional ball for safety’s sake. Remember, you’ll be using up yarn making a good-sized swatch.

Be sure you are using consistent units of measure (yards or meters). If one yarn is labeled in meters and one in yards, you’ll need to convert the yards to meters or vice versa before calculating how much yarn you need.

Q Do you have any advice on how to calculate yarn amounts when I’m designing my own garments?

A That’s the 6 million dollar question, isn’t it? The amount of yarn you need depends on the size of the yarn, the stitch pattern, your gauge, and the size of the item you are making. When you follow a published pattern, the instructions are your guide. Many people buy an extra ball of yarn, just to be certain to have enough. You can always use leftover yarn for another project, and many stores accept returns of extra balls for credit. If you don’t have a pattern to go by, find a published pattern for an item similar to your design, using a yarn of similar weight, and estimate your needs.

You can also estimate your yarn needs when you make your swatch. Before you begin the swatch, pull out a length of yarn (say, 5 or 10 yards), jot down the measurement, and tie a loose overhand knot. If you reach the knot before completing your swatch, untie the knot, reel out more yarn, jot down the new measurement, and tie another loose knot. When the swatch is complete, measure how much yarn is left before you get to the knot. Subtract this amount from the total of the yardage that you pulled out of the ball. This is the total yardage you used for the swatch, including yarn tails. Now, measure the area of your swatch in square inches.

For example: Number of yards used for swatch ÷ square inches in swatch = Number of yards used per square inch

Now, estimate the total area of your project in square inches. It’s easy if your project is a square or rectangle: Just multiply the width times the height. But if you’re making a sweater, the calculation is a bit more complicated. Here’s the formula:

(Total finished chest measurement × length of sweater) + (width of top of sleeve + width of sleeve cuff) × length of sleeve = Area of sweater

Total area of sweater × Number of yards used per square inch = Total number of inches needed for project

Remember — this is just an estimate!

When you finish a project, make a note of how much yarn you used so you can refer to it in the future.

Q How do I convert from yards to meters?

A One meter equals 1.09 yards, so you need to divide the number of yards by 1.09 to get the conversion to meters. Another way to think of it is that a meter is about 10% longer than a yard.

For example: To convert 15 yards to meters:

15 ÷ 1.09 = 13.76 meters

Q How do I convert from meters to yards?

A Reverse the process and multiply the number of meters by 1.09.

For example: To convert 25 meters to yards:

25 × 1.09 = 27.25 yards

Q My pattern calls for a yarn that has been discontinued. Is there any way to find out about the characteristics of discontinued yarns to help me choose an appropriate substitute?

A There are resources available to help you find out more about yarns, even those that are discontinued. Local yarn shop owners often have information on discontinued yarns, and really experienced ones may even be able to play “Name That Yarn” with just a glance.

You can also search the Internet. Sellers on eBay often offer older yarn, complete with fiber and yardage information. Try Google (or other search engines) for the yarn name and manufacturer. As of the time of this writing, www.wise-needle.com and other sites have complete information and reviews on yarns, both current and discontinued. You might also try contacting the yarn company itself; again, you can find address information on the Internet or in crochet and knitting magazines.

Q What is the best way to pull yarn from the ball?

A Usually pulling from the center is best. If you are using a commercially packaged skein or ball, first look to see if the outside strand of the yarn is tucked into the center of the ball. If it is, pull it out but don’t use it. Stick your fingers into the center of the ball and fish around to see if you can find the inner end. You may need to pull out a little wad of yarn in order to find the tail. This is the end to use.

commercially wound ball

Note: If you are working with the yarn doubled, you may use both the end from the center and the one from the outside of the ball.

Q How do I handle an unwound hank of yarn?

A Don’t try to work directly from the hank or you’ll be sorry! You need to wind it into a ball before you start stitching. You can use a yarn swift, lampshade, chair, or someone willing to hold the yarn for you. Untwist the hank and hang it carefully on your holder — animate or inanimate. If the yarn is tied in several places, cut the shorter pieces of yarn and throw them away. Sometimes there is a single knot where the beginning and end meet, wrapped in such a way as to keep the yarn from tangling. Be especially watchful in the beginning, because you may have to unwrap the yarn from around the skein for the first few feet. Cut the knot and take a single end in your hand, winding carefully for the first round or two until you are certain that the yarn is unwinding without tangling.

SEE ALSO: Pages 23–24, for more on ball winders and swifts.

Q Can I create my own center-pull ball?

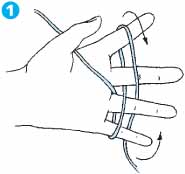

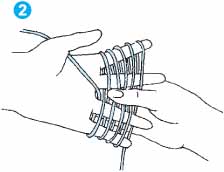

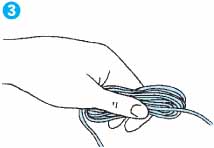

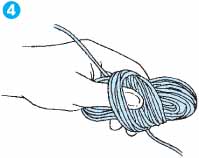

A Yes. The easiest way is with a ball winder, which winds the skein into a nice center-pull form. If you don’t have a ball winder, however, you can do it manually:

1. Hold the starting end between your thumb and forefinger and spread your other fingers. Keeping the tail secure with your thumb, wind the yarn in a figure eight around your fingers about a dozen times. Don’t let the strands overlap each other.

2. Pinching the yarn where it crosses itself, slide the yarn off your fingers.

3. Fold the bundle of yarn in half.

4. Keeping 10-12 inches (25-30 cm) of the tail end dangling, start winding the yarn loosely around this little wad of yarn, turning it this way and that to form a ball. Wrap the yarn over your fingers to ensure that you are wrapping loosely enough. When you have finished winding, you should be able to pull on the tail coming out of the middle of the ball.

Q How do I know if my ball is wound too tightly?

A Your ball should not be hard — it should have a bit of spring to it. Yarn wound too tightly is stretched and tense, which is apt to cause trouble once it’s made into a fabric. The yarn may become permanently stretched, decreasing its elasticity. Even if it isn’t permanently ruined, if you stitch the yarn up in its stretched state and then wash it, it will return to its natural, un-stretched state, with possible undesirable consequences to the size of the piece! If you wind a center-pull ball, the ball collapses in on itself as it is used, releasing any extra tension.

Q How can I keep my yarn from splitting?

A If your yarn splits, it may be that the yarn is not of high quality or that it is loosely spun. Some hooks with pointy tips may split the yarn. In that case, you may need to stitch extra carefully to avoid splitting the yarn, or use a different hook. A hook with a rough spot also sometimes splits the yarn. Try sanding the rough spot with very fine sandpaper. If that doesn’t work, discard the hook.

If your yarn is coming untwisted as you work, examine how you are pulling it from the ball. If you are using a center-pull ball, you may be removing twist because of the direction you are pulling. Try pulling from the opposite side of the ball or using the end from the outside of the ball.

Q What should I do when I reach a knot in the yarn?

A Even high-quality yarns may have a knot or a weak spot every now and then. Don’t work over it. Instead, cut the yarn several inches before the knot, leaving a tail to be woven in later. Cut out the bad spot, then begin again, just as you would when adding a new ball.

SEE ALSO: Page 54, for starting a new yarn.

When you begin a new row, pull out enough yarn to work the entire row, so that you can see any imperfection before you reach it. You can then cut the yarn and rejoin it at the beginning of the row and thus avoid starting a new yarn in the middle of the fabric.

Q What is a novelty yarn?

A Just as its name implies, this isn’t your run-of-the-mill yarn. You’ll know it when you see it. The fun of a novelty yarn comes from its unique characteristics — it can be made from almost anything and spun in almost any way. It may have a great deal of texture, or it may be spun with non-fiber additives like beads or feathers. It may have little bits of stuff hanging from a main core. It may be a thin “crochet along” (or “knit along”) thread meant to be held together with another strand of yarn as you stitch, or it may be as bulky as your thumb.

Novelty yarns are often described by their characteristics: eyelash, slub, metallic, ribbon, or bouclé (meaning curly in French). When substituting one novelty yarn for another, choose a similar yarn type in order to achieve a similar look.

bouclé

slub

eyelash

ribbon

Q I’ve tried working with novelty yarns, but found them frustrating. Do you have any suggestions?

A Novelty yarns and fuzzy yarns are beautiful, but they can present a challenge for crocheters. Here are some tips that may make it easier if you are using a novelty yarn:

Use your fingers as well as your eyes to determine where to put the hook.

Work between stitches rather than into actual stitches. (If you are following written instructions, be aware that the gauge and look of the fabric will be different from fabric stitched in the standard way.)

Work with a larger hook than you normally would use for the weight of your yarn. Again, pay attention to your gauge if you are following a printed pattern.

Try a mesh stitch rather than a solid stitch pattern. It’s easier to work into chain spaces than into stitches.

Work two strands together — a smooth yarn along with the novelty yarn — to help distinguish the stitches.

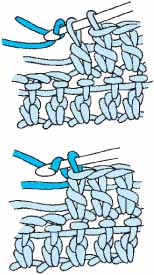

Working between stitches

SEE ALSO: Pages 87–90, for where to place the hook.

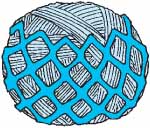

Q Do you have tips for working with slippery yarn?

A Rayon ribbons and other yarns are beautiful to look at, but they too present a challenge. Even if you wind them carefully, the balls have a tendency to melt into a puddle at the first opportunity. Try corralling them into a sandwich bag or wrap them with a Yarn Bra, old stocking, or other stretchy material for better control.

Yarn Bra

SEE ALSO: Pages 55–56, for weaving in slippery ends.

Q Is there anything I can do to keep variegated yarns from appearing splotchy?

A When you get noticeable odd-shaped areas of a single color in the middle of a piece of crochet, it’s known as “pooling.” Try alternating two balls of yarn or use the inside and outside ends of a single ball of yarn each row or round to avoid pooling. Or, use a stitch pattern that breaks up large expanses of the variegated yarn: spike stitches, contrasting color stripes, or texture stitches.

As the distance across the piece changes, the frequency with which certain colors show up changes. For instance, when you shape the armholes and neck edge, the distance the yarn travels is shorter, so the color repeats create a different pattern on these shorter rows than in the longer rows below. Therefore, you may need to use these anti-pooling techniques on some parts of a garment and not on others. (Voice of Experience: You can’t tell from a small swatch if your colors are going to pool.)

Q Is there any kind of yarn I can’t crochet with?

A Not that I’ve found, although some yarns may be more challenging than others.

Q How do I add a new yarn?

A It’s best to start a new ball of yarn at the edge if you can. The technique is the same no matter which stitch you are working: Work until there are two loops left on the hook, yarn over with the new yarn and pull through both loops on hook.

If you don’t already have a stitch on the hook, just insert the hook into the proper spot, yarn over and pull up a loop. Treat this loop as you would a slip knot; you may need to chain for the height of your first stitch. Leave a tail at least 6″ (15 cm) long on both the old and new yarns so that you can weave in the ends later.

adding a new yarn mid-row

SEE ALSO: Page 73, for stitch heights.

Q I hate weaving in ends. Is there any way to take care of tails left when starting a new color or ball so that I don’t have to worry about them later?

A Many crocheters like to work over the tail of the old yarn as they work the first few stitches in a new yarn. As you begin a new yarn, hold the tails of yarn to the left along the top of the stitches on the previous row or round. When you insert the hook into the next stitch and pull up a loop, make sure that you are working around the tails, catching and securing them into the fabric as you work each of the next couple of inches of stitches. If you find that this method is too bulky, just catch one of the ends, or leave the ends to be woven in later.

Q I’m using a very slippery yarn and finding it particularly difficult to hide the ends, which tend to pop out of the finished fabric. Do you have suggestions?

A The usual method of weaving in ends as you work is less successful with slippery yarns, and it also may not hide contrasting yarns satisfactorily. Some silk and rayon ribbons take any opportunity to slide free. Whenever you’re working with these yarns, leave longer ends (8″/20 cm), so that when the fabric is finished, you can work them diagonally through the back of several stitches one way, and then diagonally in the opposite direction. You could also try tacking down the ends with sewing thread in a matching color. You may find it helpful to put a dot of soft fabric glue on the ends. (Try it first on your swatch to make sure you are happy with the way it feels against your skin.)

SEE ALSO: Pages 235–37, for more on weaving in ends.