Chapter 3

Cellular Components of Nervous Tissue

Several types of cellular elements are integrated to constitute normally functioning brain tissue. The neuron is the communicating cell, and many neuronal subtypes are connected to one another via complex circuitries, usually involving multiple synaptic connections. Neuronal physiology is supported and maintained by neuroglial cells, which have highly diverse and incompletely understood functions. These include myelination, secretion of trophic factors, maintenance of the extracellular milieu, and scavenging of molecular and cellular debris from it. Neuroglial cells also participate in the formation and maintenance of the blood–brain barrier, a multicomponent structure that is interposed between the circulatory system and the brain substance and that serves as the molecular gateway to brain tissue.

Neurons

The neuron is a highly specialized cell type and is the essential cellular element in the CNS. All neurological processes are dependent on complex cell–cell interactions among single neurons as well as groups of related neurons. Neurons can be categorized according to their size, shape, neurochemical characteristics, location, and connectivity, which are important determinants of that particular functional role of the neuron in the brain. More importantly, neurons form circuits, and these circuits constitute the structural basis for brain function. Macrocircuits involve a population of neurons projecting from one brain region to another region, and microcircuits reflect the local cell–cell interactions within a brain region. Detailed analysis of these macro- and microcircuits is essential for understanding neuronal function and dysfunction in the healthy and the diseased brain.

Broadly speaking, therefore, there are five general categories of neurons: inhibitory neurons that make local contacts (e.g., GABAergic interneurons in the cerebral and cerebellar cortex), inhibitory neurons that make distant contacts (e.g., medium spiny neurons of the basal ganglia or Purkinje cells of the cerebellar cortex), excitatory neurons that make local contacts (e.g., spiny stellate cells of the cerebral cortex), excitatory neurons that make distant contacts (e.g., pyramidal neurons in the cerebral cortex), and neuromodulatory neurons that influence neurotransmission, often at large distances. Within these general classes, the structural variation of neurons is systematic, and careful analyses of the anatomic features of neurons have led to various categorizations and to the development of the concept of cell type. The grouping of neurons into descriptive cell types (such as chandelier, double bouquet, or bipolar cells) allows the analysis of populations of neurons and the linking of specified cellular characteristics with certain functional roles.

General Features of Neuronal Morphology

Neurons are highly polarized cells, meaning that they develop distinct subcellular domains that subserve different functions. Morphologically, in a typical neuron, three major regions can be defined: (1) the cell body (soma or perikaryon), which contains the nucleus and the major cytoplasmic organelles; (2) a variable number of dendrites, which emanate from the perikaryon and ramify over a certain volume of gray matter and that differ in size and shape, depending on the neuronal type; and (3) a single axon, which extends, in most cases, much farther from the cell body than the dendritic arbor (Fig. 3.1). Dendrites may be spiny (as in pyramidal cells) or nonspiny (as in most interneurons), whereas the axon is generally smooth and emits a variable number of branches (collaterals). In vertebrates, many axons are surrounded by an insulating myelin sheath, which facilitates rapid impulse conduction. The axon terminal region, where contacts with other cells are made, displays a wide range of morphological specializations, depending on its target area in the central or peripheral nervous system.

Figure 3.1 Typical morphology of projection neurons. (Left) A Purkinje cell of the cerebellar cortex and (right) a pyramidal neuron of the neocortex. These neurons are highly polarized. Each has an extensively branched, spiny apical dendrite, shorter basal dendrites, and a single axon emerging from the basal pole of the cell. The scale bar represents approximately 200 µm.

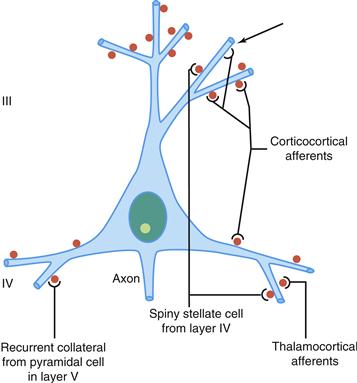

The cell body and dendrites are the two major domains of the cell that receive inputs, and dendrites play a critically important role in providing a massive receptive area on the neuronal surface. In addition, there is a characteristic shape for each dendritic arbor, which can be used to classify neurons into morphological types. Both the structure of the dendritic arbor and the distribution of axonal terminal ramifications confer a high level of subcellular specificity in the localization of particular synaptic contacts on a given neuron. The three-dimensional distribution of dendritic arborization is also important with respect to the type of information transferred to the neuron. A neuron with a dendritic tree restricted to a particular cortical layer may receive a very limited pool of afferents, whereas the widely expanded dendritic arborizations of a large pyramidal neuron will receive highly diversified inputs within the different cortical layers in which segments of the dendritic tree are present (Fig. 3.2) (Mountcastle, 1978). The structure of the dendritic tree is maintained by surface interactions between adhesion molecules and, intracellularly, by an array of cytoskeletal components (microtubules, neurofilaments, and associated proteins), which also take part in the movement of organelles within the dendritic cytoplasm.

Figure 3.2 Schematic representation of four major excitatory inputs to pyramidal neurons. A pyramidal neuron in layer III is shown as an example. Note the preferential distribution of synaptic contacts on spines. Spines are labeled in red. Arrow shows a contact directly on the dendritic shaft.

An important specialization of the dendritic arbor of certain neurons is the presence of large numbers of dendritic spines, which are membranous protrusions. They are abundant in large pyramidal neurons and are much sparser on the dendrites of interneurons (see later).

The perikaryon contains the nucleus and a variety of cytoplasmic organelles. Stacks of rough endoplasmic reticulum are conspicuous in large neurons and, when interposed with arrays of free polyribosomes, are referred to as Nissl substance. Another feature of the perikaryal cytoplasm is the presence of a rich cytoskeleton composed primarily of neurofilaments and microtubules, discussed in detail in Chapter 4. These cytoskeletal elements are dispersed in bundles that extend from the soma into the axon and dendrites.

Whereas dendrites and the cell body can be characterized as domains of the neuron that receive afferents, the axon, at the other pole of the neuron, is responsible for transmitting neural information. This information may be primary, in the case of a sensory receptor, or processed information that has already been modified through a series of integrative steps. The morphology of the axon and its course through the nervous system are correlated with the type of information processed by the particular neuron and by its connectivity patterns with other neurons. The axon leaves the cell body from a small swelling called the axon hillock. This structure is particularly apparent in large pyramidal neurons; in other cell types, the axon sometimes emerges from one of the main dendrites. At the axon hillock, microtubules are packed into bundles that enter the axon as parallel fascicles. The axon hillock is the part of the neuron where the action potential is generated. The axon is generally unmyelinated in local circuit neurons (such as inhibitory interneurons), but it is myelinated in neurons that furnish connections between different parts of the nervous system. Axons usually have higher numbers of neurofilaments than dendrites, although this distinction can be difficult to make in small elements that contain fewer neurofilaments. In addition, the axon may show extensive, spatially constrained ramifications, as in certain local circuit neurons; it may give out a large number of recurrent collaterals, as in neurons connecting different cortical regions, or it may be relatively straight in the case of projections to subcortical centers, as in cortical motor neurons that send their very long axons to the ventral horn of the spinal cord. At the interface of axon terminals with target cells are the synapses, which represent specialized zones of contact consisting of a presynaptic (axonal) element, a narrow synaptic cleft, and a postsynaptic element on a dendrite or perikaryon.

Synapses and Spines

Synapses

The exchange of information between neurons mainly takes place through two types of highly specialized structures: chemical synapses (the majority) and electrical synapses. In the latter case, although the plasma membranes of adjacent neurons are separated by a gap of about 2 nm, they contain small channels (gap junctions) that connect the cytoplasm of the adjoining neurons, permitting the diffusion of small molecules and the flow of electric current (Bennett & Zukin, 2004). Each chemical synapse (referred to as “synapse” in the remainder of this chapter) is a complex of several components: (1) a presynaptic element, (2) a cleft, and (3) a postsynaptic element. The presynaptic element is a specialized part of the presynaptic neuron’s axon, the postsynaptic element is a specialized part of the postsynaptic somatodendritic membrane, and the space between these two closely apposed elements is the cleft. The portion of the axon that participates in the synapse is the bouton, and it is identified by the presence of synaptic vesicles and a presynaptic thickening at the active zone (Fig. 3.3). The postsynaptic element is marked by a postsynaptic thickening opposite the presynaptic thickening. When both sides are equally thick, the synapse is referred to as symmetric. When the postsynaptic thickening is greater, the synapse is asymmetric. Edward George Gray noticed this difference and divided synapses into two types: Gray’s type 1 synapses are asymmetric and have variably shaped, or pleomorphic, vesicles; Gray’s type 2 synapses are symmetric and have clear, round vesicles. The significance of this distinction is that research has shown that in general, Gray’s type 1 synapses tend to be excitatory, whereas Gray’s type 2 synapses tend to be inhibitory. This correlation greatly enhanced the usefulness of electron microscopy in neuroscience.

Figure 3.3 Ultrastructure of dendritic spines and synapses in the human brain. A and B: Narrow spine necks (asterisks) emanate from the main dendritic shaft (D). The spine heads (S) contain filamentous material (A, B). Some large spines contain cisterns of a spine apparatus (sa, B). Asymmetric excitatory synapses are characterized by thickened postsynaptic densities (arrows A, B). A perforated synapse has an electron-lucent region amidst the postsynaptic density (small arrow, B). The presynaptic axonal boutons (B) of excitatory synapses usually contain round synaptic vesicles. Symmetric inhibitory synapses (arrow, C) typically occur on the dendritic shaft (D) and their presynaptic boutons contain smaller round or ovoid vesicles. Dendrites and axons contain numerous mitochondria (m). Scale bar = 1 µm (A, B) and 0.6 µm (C).

Electron micrographs courtesy of Drs. S. A. Kirov and M. Witcher (Medical College of Georgia), and K. M. Harris (University of Texas–Austin).

In cross section on electron micrographs, a synapse looks like two parallel lines separated by a very narrow space (Fig. 3.3). Viewed from the inside of the axon or dendrite, it looks like a patch of variable shape. Some synapses are a simple patch, or macule. Macular synapses can grow fairly large, reaching diameters over 1 mm. The largest synapses have discontinuities or holes within the macule and are called perforated synapses (Fig. 3.3). In cross section, a perforated synapse may resemble a simple macular synapse or several closely spaced smaller macules.

The portion of the presynaptic element that is apposed to the postsynaptic element is the active zone. This is the region where the synaptic vesicles are concentrated and where at any time a small number of vesicles are docked, and presumably ready for fusion. The active zone is also enriched with voltage gated calcium channels, which are necessary to permit activity-dependent fusion and neurotransmitter release.

The synaptic cleft is truly a space, but its properties are essential. The width of the cleft (~20 nm) is critical because it defines the volume in which each vesicle releases its contents and, therefore, the peak concentration of neurotransmitter upon release. On the flanks of the synapse, the cleft is spanned by adhesion molecules, which are believed to stabilize the cleft.

The postsynaptic element may be a portion of a soma or a dendrite or, rarely, part of an axon. In the cerebral cortex, most Gray’s type 1 synapses are located on dendritic spines, which are specialized protrusions of the dendrite, and most Gray’s type 2 synapses are located on somata or dendritic shafts. A similar segregation is seen in cerebellar cortex. In nonspiny neurons, symmetric and asymmetric synapses are often less well separated. Irrespective of location, a postsynaptic thickening marks the postsynaptic element. In Gray’s type 1 synapses, the postsynaptic thickening (or postsynaptic density, PSD) is greatly enhanced. Among the molecules that are associated with the PSD are neurotransmitter receptors (e.g., NMDA receptors) and molecules with less obvious function, such as PSD-95.

Spines

Spines are protrusions on the dendritic shafts of some types of neurons and are the sites of synaptic contacts, usually excitatory. Use of the silver impregnation techniques of Golgi or of the methylene blue introduced by Ehrlich in the late nineteenth century led Santiago Ramón y Cajal to the discovery of spiny appendages on dendrites of a variety of neurons. The best known are those on pyramidal neurons and Purkinje cells, although spines occur on neuron types at all levels of the central nervous system. As early as 1890, Santiago Ramón y Cajal suggested that spines could collect the electrical charge resulting from neuronal activity (Cajal, 1909–1911). He also proposed that spines substantially increase the receptive surface of the dendritic arbor, which may represent an important factor in receiving the contacts made by the axonal terminals of other neurons. It has been calculated that the approximately 20,000 spines of a pyramidal neuron account for more than 40% of its total surface area (Peters, Palay, & Webster, 1991).

More recent analyses of spine electrical properties have demonstrated that spines are dynamic structures that can regulate many neurochemical events related to synaptic transmission and modulate synaptic efficacy. Spines are also known to undergo pathologic alterations and have a reduced density in a number of experimental manipulations (such as deprivation of a sensory input) and in many developmental, neurologic, and psychiatric conditions (such as dementing illnesses, chronic alcoholism, schizophrenia, and trisomy 21). Morphologically, spines are characterized by a narrower portion emanating from the dendritic shaft, the neck, and an ovoid bulb or head, although spine morphology may vary from large mushroom-shaped bulbs to small bulges barely discernable on the surface of the dendrite. Spines have an average length of ~2 µm, but there is considerable variability in their dimensions. At the ultrastructural level (Fig. 3.3), spines are characterized by the presence of asymmetric synapses and contain fine and quite indistinct filaments. These filaments most likely consist of actin and α- and β-tubulins. Microtubules and neurofilaments present in dendritic shafts do not enter spines. Mitochondria and free ribosomes are infrequent, although many spines contain polyribosomes in their neck. Interestingly, most polyribosomes in dendrites are located at the bases of spines, where they are associated with endoplasmic reticulum, indicating that spines possess the machinery necessary for the local synthesis of proteins. Another feature of the spine is the presence of confluent tubular cisterns in the spine head that represent an extension of the dendritic smooth endoplasmic reticulum. Those cisterns are referred to as the spine apparatus. The function of the spine apparatus is not fully understood but may be related to the storage of calcium ions during synaptic transmission.

Specific Examples of Different Neuronal Types

Inhibitory Local Circuit Neurons

Inhibitory Interneurons of the Cerebral Cortex

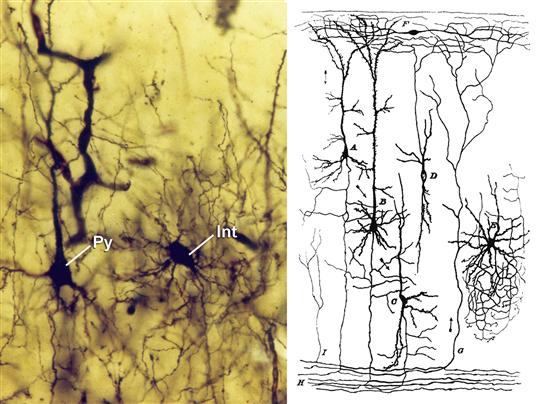

The study of cortical interneurons dates back to the original work of Camillo Golgi when he applied the new technique he had discovered, the reazione nera (black reaction: Golgi, 1873). This method allowed all the components of a neuron to be visualized in histological sections (soma, dendrites, and axon). Golgi proposed that neurons could generally be considered to be of two different morphological and physiological types: motor (type I) and sensory (type II) neurons. These motor neurons had long axons that sprout collaterals, and they could project beyond the gray matter, whereas by contrast, sensory neurons had short axons that arborized near the parent cell and did not leave the gray matter. This hypothesis was challenged when Cajal entered the scene following his masterful studies of brain structure based on the Golgi method. Cajal argued that it was not physiologically possible to maintain such a distinction, and he designated Golgi’s two types as cells with a long axon (projection neurons) and cells with a short axon (intrinsic neurons), avoiding any consideration of their possible physiological roles (Fig. 3.4). Since then, the term short-axon cell has commonly been used as synonymous with interneurons (DeFelipe, 2002).

Figure 3.4 Left, photomicrograph from one of the Cajal’s preparations of the “occipital pole” of an eighteen-day-old cat, showing the soma of a pyramidal cell (Py) and a neurogliaform cell (interneuron; Int) stained with the Golgi method. Right, the principal cellular types based on the works of Cajal on the cerebral cortex of small mammals (rabbit, guinea pig, rat, and mouse). A, pyramidal cell of medium size; B, giant pyramidal cell; C, polymorphic cell; D, cell whose axon is ascending; E, cell of Golgi; F, special cell of the molecular layer.

Copyright © Herederos de Santiago Ramón y Cajal.

In general, cortical interneurons have been subdivided into two large groups: spiny non-pyramidal cells and aspiny or sparsely spiny non-pyramidal cells. Spiny non-pyramidal cells represent the typical neurons (including spiny stellate cells) of the middle cortical layers (especially layer IV). These spiny non-pyramidal cells are morphologically heterogeneous, with ovoid, fusiform, and triangular somata, and most of them are excitatory (probably glutamatergic). Their axons are found within layer IV or in the layers adjacent to that in which their soma is located, either above or below. Aspiny or sparsely spiny non-pyramidal cells have axons that remain close to the parental cell body, although prominent collaterals may run out from some of these in the horizontal (parallel to the cortical surface) or vertical dimension (ascending and/or descending to other cortical layers). These interneurons constitute approximately 15 to 30% of the total population of cortical neurons, and they appear to be mostly GABAergic, representing the main components of inhibitory cortical circuits (Jones, 1993) (Fig. 3.4). Indeed, they can be found in all cortical layers, and they characteristically display a tremendous variety of morphological, biochemical, and physiological features (Markram et al., 2004; Kubota et al., 2011). However, a general consensus to name and classify cortical neurons has yet to emerge. This is in part due to the fact that, with some exceptions, there are no rules to establish the essential characteristics that define whether an individual neuron belongs to a given cell type. Indeed, this characterization is also hindered by the fact that most studies of these neurons are generally based on either morphological, physiological, or molecular approaches, rather than any combination of these features.

In a more recent attempt to classify these neurons, the Petilla Interneuron Nomenclature Group (Ascoli et al., 2008) proposed a set of terms to organize and describe the anatomical, molecular, and physiological features of GABAergic interneurons of the cerebral cortex based on existing data. The anatomical, molecular, and physiological classifications divided GABAergic cortical interneurons into several main types of interneurons, which in turn were further subdivided depending on distinct properties. Briefly, the anatomical classification identified three major neuronal types: cells that target pyramidal cells; cells that do not show target specificity; and cells that specifically target other interneurons. The molecular classification includes five main groups based on the expression of specific biochemical markers: parvalbumin, somatostatin, neuropeptide Y in the absence of somatostatin, vasointestinal peptide, and cholecystokinin in the absence of somatostatin and vasointestinal peptide. Finally, the physiological classification identified six main types of interneurons: fast spiking neurons, nonadapting/nonfast spiking neurons, adapting neurons, accelerating cells, irregular spiking neurons, and intrinsic bursting neurons. Each of these attempts to classify these neurons has its limitations, and the scientific community still lacks a general catalogue of accepted neuron types and names. Nevertheless, standardizing the nomenclature based on the properties of GABAergic interneurons proposed by the Petilla Interneuron Nomenclature Group represents a step in the right direction towards a more comprehensive classification of cortical GABAergic interneurons.

In general, GABAergic interneurons control the timing and flow of information in the cerebral cortex (Fig. 3.5), although there does seem to be some division of labor between the different types of interneurons (Klausberger & Somogyi, 2008). One such example is the class of basket and chandelier cells that are considered as fast-spiking GABAergic interneurons and that express the calcium binding protein parvalbumin. These cells appear to play important roles in controlling the timing of pyramidal cell firing, shaping the network output and the rhythms generated in different states of consciousness (Klausberger et al., 2003; Howard, Tamas, & Soltesz, 2005; Yizhar, Fenno, Davidson, Mogri, & Deisseroth, 2011). By contrast, other interneurons containing nitric oxide synthase and various neuropeptides are implicated in the neurovascular coupling (Rossier, 2009). In addition, some types of interneurons have been directly implicated in disease, which is particularly evident when we consider that certain alterations to chandelier and basket cells seem to be critical in establishing some forms of human epilepsy (DeFelipe, 1999; Magloczky & Freund, 2005). Finally, the proportion of GABAergic neurons in the cerebral cortex of rodents is lower than in primates, and there are interneurons in primates that are not found in rodents (Jones, 1975, 1993; DeFelipe, 2002; Markram et al., 2004; Ascoli et al., 2008). These observations, together with the existence of differences in the developmental origins of GABAergic interneurons in rodents and primates, including humans, seem to indicate that more GABA interneurons and newer forms of GABA interneurons appeared in the primate cortex during the course of evolution (Rakic, 2009; Raghanti, Spocter, Butti, Hof, & Sherwood, 2010; DeFelipe, 2011). These features of GABAergic interneurons make their study one of the most exciting and active research fields in relation to the cerebral cortex.

Figure 3.5 A schematic circuit based upon the known cortical cells upon which thalamic afferent fibers terminate in cats and monkeys. The GABAergic interneurons (blue) are identified by the names that they have received in these species. Arc, neuron with arciform axon; Ch, chandelier cell; DB, double bouquet cell; LB, large basket cell; Ng, neurogliaform cell; Pep, peptidergic neuron; SB, small basket cell. Excitatory neurons (black) include pyramidal cells of layers II–VI and the spiny stellate cells (SS) of layer IV.

Courtesy of Dr. E. G. Jones.

Inhibitory Projection Neurons

Medium-sized Spiny Cells

These neurons are unique to the striatum, a part of the basal ganglia that comprises the caudate nucleus and putamen (see Chapter 31). Medium-sized spiny cells are scattered throughout the caudate nucleus, the putamen, and the nucleus accumbens, and are recognized by their relatively large size, compared with other cellular elements of the basal ganglia. They differ from all other neurons in the striatum in that they have a highly ramified dendritic arborization radiating in all directions, which is densely covered with spines. They furnish a major output from the striatum and receive a highly diverse input from, among other sources, the cerebral cortex, thalamus, and certain dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra. These neurons are neurochemically quite heterogeneous, contain GABA, and may contain several neuropeptides and the calcium-binding protein calbindin. In Huntington disease, a neurodegenerative disorder of the striatum characterized by involuntary movements and progressive dementia, an early and dramatic loss of medium-sized spiny cells occurs.

Purkinje Cells

Purkinje cells are the most morphologically striking cellular elements of the cerebellar cortex. They are arranged in a single row throughout the entire cerebellar cortex between the molecular (outer) layer and the granular (inner) layer. Purkinje cells are among the largest neurons in the brain and have a round perikaryon, classically described as shaped “like a chianti bottle,” with a highly branched dendritic tree resembling a candelabrum and extending into the molecular layer where they are contacted by incoming systems of afferent fibers from granule neurons and the brainstem (see Chapter 32). Their apical dendrites have an enormous number of spines (more than 80,000 per cell). A particular feature of the dendritic tree of the Purkinje cell is that it is distributed in one plane, perpendicular to the longitudinal axes of the cerebellar folds, and each dendritic arbor determines a separate domain of cerebellar cortex (Fig. 3.1). The axons of Purkinje neurons course through the cerebellar white matter and contact cerebellar nuclei or vestibular nuclei. These neurons contain the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA and the calcium-binding protein calbindin. Spinocerebellar ataxia, a severe disorder combining ataxic gait and impairment of fine hand movements, accompanied by dysarthria and tremor, has been documented in some families and is related directly to Purkinje cell degeneration.

Excitatory Local Circuit Neurons

Spiny Stellate Cells

Spiny stellate cells are small multipolar neurons with local dendritic and axonal arborizations. These neurons resemble pyramidal cells in that they are the only other cortical neurons with large numbers of dendritic spines, but they differ from pyramidal neurons in that they lack an elaborate apical dendrite. The relatively restricted dendritic arbor of these neurons is presumably a manifestation of the fact that they are high-resolution neurons that gather afferents to a very restricted region of the cortex. Dendrites rarely leave the layer in which the cell body resides. The spiny stellate cell also resembles the pyramidal cell in that it provides asymmetric synapses that are presumed to be excitatory, and is thought to use glutamate as its neurotransmitter (Peters & Jones, 1984).

The axons of spiny stellate neurons have primarily intracortical targets and a radial orientation, and appear to play an important role in forming links among layer IV, the major thalamorecipient layer, and layers III, V, and VI, the major projection layers. The spiny stellate neuron appears to function as a high-fidelity relay of thalamic inputs, maintaining strict topographic organization and setting up initial vertical links of information transfer within a given cortical area (Peters & Jones, 1984).

Excitatory Projection Neurons

Pyramidal Cells

All cortical output is carried by pyramidal neurons, and the intrinsic activity of the neocortex can be viewed simply as a means of finely tuning and coordinating their output. A pyramidal cell is a highly polarized neuron, with a major orientation axis perpendicular (or orthogonal) to the pial surface of the cerebral cortex. In cross section, the cell body is roughly triangular (Fig. 3.1), although a large variety of morphologic types exist with elongate, horizontal, or vertical fusiform, or inverted perikaryal shapes. Pyramidal cells are the major excitatory type of neurons and use glutamate as their neurotransmitter. A pyramidal neuron typically has a large number of dendrites that emanate from the apex and form the base of the cell body. The span of the dendritic tree depends on the laminar localization of the cell body, but it may, as in giant pyramidal neurons, spread over several millimeters. The cell body and dendritic arborization may be restricted to a few layers or, in some cases, may span the entire cortical thickness (Jones, 1984).

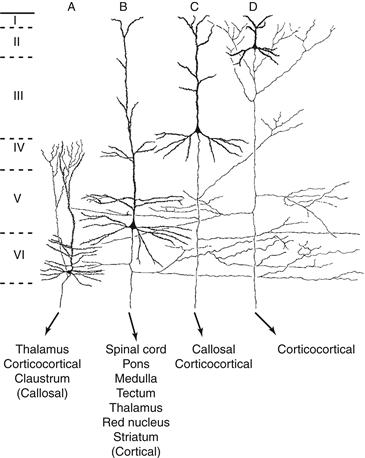

In most cases, the axon of a large pyramidal cell extends from the base of the perikaryon and courses toward the subcortical white matter, giving off several collateral branches that are directed to cortical domains generally located within the vicinity of the cell of origin (as explained later). Typically, a pyramidal cell has a large nucleus, and a cytoplasmic rim that contains, particularly in large pyramidal cells, a collection of granular material chiefly composed of lipofuscin. Although all pyramidal cells possess these general features, they can also be subdivided into numerous classes based on their morphology, laminar location, and connectivity with cortical and subcortical regions (Fig. 3.6) (Jones, 1975).

Figure 3.6 Morphology and distribution of neocortical pyramidal neurons. Note the variability in cell size and dendritic arborization, as well as the presence of axon collaterals, depending on the laminar localization (I–VI) of the neuron. Also, different types of pyramidal neurons with a precise laminar distribution project to different regions of the brain (less important projections zones are indicated by parentheses).

Adapted from Jones (1984).

Spinal Motor Neurons

Motor cells of the ventral horns of the spinal cord, also called motoneurons, have their cell bodies within the spinal cord and send their axons outside the central nervous system to innervate the muscles. Different types of motor neurons are distinguished by their targets. The α motoneurons innervate skeletal muscles, but smaller motor neurons (the γ motoneurons, forming about 30% of the motor neurons) innervate the spindle organs of the muscles (see Chapter 28). Alpha motor neurons are some of the largest neurons in the entire central nervous system and are characterized by a multipolar perikaryon and a very rich cytoplasm that renders them very conspicuous in histological preparations. They have a large number of spiny dendrites that arborize locally within the ventral horn. The α motoneuron axon leaves the central nervous system through the ventral root of the peripheral nerves. Their distribution in the ventral horn is not random and corresponds to a somatotopic representation of the muscle groups of the limbs and axial musculature (Brodal, 1981). Spinal motor neurons use acetylcholine as their neurotransmitter. Large motor neurons are severely affected in lower motor neuron disease, a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by progressive muscular weakness that affects, at first, one or two limbs but involves more and more of the body musculature, which shows signs of wasting as a result of denervation.

Neuromodulatory Neurons

Dopaminergic Neurons of the Substantia Nigra

Dopaminergic neurons are large neurons that reside mostly within the pars compacta of the substantia nigra and in the ventral tegmental area (van Domburg & ten Donkelaar, 1991). A distinctive feature of these cells is the presence of a pigment, neuromelanin, in compact granules in the cytoplasm. These neurons are medium-sized to large, fusiform, and frequently elongated. They have several large radiating dendrites. The axon emerges from the cell body or from one of the dendrites and projects to large expanses of cerebral cortex and to the basal ganglia. These neurons contain the catecholamine-synthesizing enzyme tyrosine hydroxylase, as well as the monoamine dopamine as their neurotransmitter. Some of them contain both calbindin and calretinin. These neurons are affected severely and selectively in Parkinson disease—a movement disorder different from Huntington disease and characterized by resting tremor and rigidity—and their specific loss is the neuropathologic hallmark of this disorder.

Neuroglia

The term neuroglia, or “nerve glue,” was coined in 1859 by Rudolph Virchow, who conceived of the neuroglia as an inactive “connective tissue” holding neurons together in the central nervous system. The metallic staining techniques developed by Cajal and del Rio-Hortega allowed these two great pioneers to distinguish, in addition to the ependyma lining the ventricles and central canal, three types of supporting cells in the CNS: oligodendrocytes, astrocytes, and microglia. In the peripheral nervous system (PNS), the Schwann cell is the major neuroglial component. These cells are much smaller than the neurons—usually glial cells are 4–10 µm across—yet their size depends on their state of maturation and their possible involvement in a pathological process.

Oligodendrocytes and Schwann Cells Synthesize Myelin

Most brain functions depend on rapid communication between circuits of neurons. As shown in depth later, there is a practical limit to how fast an individual bare axon can conduct an action potential. Organisms developed two solutions for enhancing rapid communication between neurons and their effector organs. In invertebrates, the diameters of axons are enlarged. In vertebrates, the myelin sheath (Fig. 3.7) evolved to permit rapid nerve conduction.

Figure 3.7 An electron micrograph of a transverse section through part of a myelinated axon from the sciatic nerve of a rat. The tightly compacted multilayer myelin sheath (My) surrounds and insulates the axon (Ax). Mit, mitochondria. Scale bar = 200 nm.

Axon enlargement accelerates action potential propagation in proportion to the square root of axonal diameter. Thus larger axons conduct faster than small ones, but substantial increases in conduction velocity require huge axons. The largest axon in the invertebrate kingdom is the squid giant axon, which is about the thickness of a mechanical pencil lead. This axon conducts the action potential at speeds of 10 to 20 m/s. As the axon mediates an escape reflex, firing must be rapid if the animal is to survive. Bare axons and continuous conduction obviously provide sufficient rates of signal propagation for even very large invertebrates, and many human axons also remain bare. However, in the human brain with 10 billion neurons, axons cannot be as thick as pencil lead, or heads would weigh one hundred pounds or more.

Thus, along the invertebrate evolutionary line, the use of bare axons imposes a natural, insurmountable limit—a constraint of axonal size—to increasing the processing capacity of the nervous system. Vertebrates, however, get around this problem through evolution of the myelin sheath, which allows 10- to 100-fold increases in conduction of the nerve impulse along axons with fairly minute diameters.

In the central nervous system, myelin sheaths (Fig. 3.8) are elaborated by oligodendrocytes. During brain development, these glial cells send out a few cytoplasmic processes that engage adjacent axons and form myelin around them (Bunge, 1968). Myelin consists of a long sheet of oligodendrocyte plasma membrane, which is spirally wrapped around an axonal segment. At the end of each myelin segment, there is a bare portion of the axon, the node of Ranvier. Myelin segments are thus called internodes. Physiologically, myelin has insulating properties such that the action potential can “leap” from node to node and therefore does not have to be regenerated continually along the axonal segment that is covered by the myelin membrane sheath. This leaping of the action potential from node to node allows axons with fairly small diameters to conduct extremely rapidly (Ritchie, 1984), and is called saltatory conduction.

Figure 3.8 An oligodendrocyte (OL) in the central nervous system is depicted myelinating several axon segments. A cutaway view of the myelin sheath is shown (M). Note that the internode of myelin terminates in paranodal loops that flank the node of Ranvier (N). (Inset) An enlargement of compact myelin with alternating dark and light electron-dense lines that represent intracellular (major dense lines) and extracellular (intraperiod line) plasma membrane appositions, respectively.

Because the brain and spinal cord are encased in the bony skull and vertebrae, evolution has promoted compactness among the supporting cells of the CNS. Each oligodendrocyte cell body is responsible for the construction and maintenance of several myelin sheaths (Fig. 3.8), thus reducing the number of glial cells required. In both PNS and CNS myelin, cytoplasm is removed between each turn of the myelin, leaving only the thinnest layer of plasma membrane. Due to protein composition differences, CNS lamellae are approximately 30% thinner than in PNS myelin. In addition, there is little or no extracellular space or extracellular matrix between the myelinated axons passing through CNS white matter. Brain volume is thus reserved for further expansion of neuronal populations.

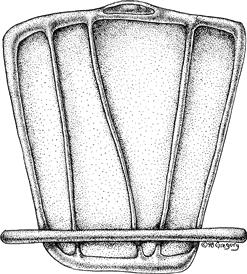

Peripheral nerves pass between moving muscles and around major joints and are routinely exposed to physical trauma. A hard tackle, slipping on an icy sidewalk, or even just occupying the same uncomfortable seating posture for too long can painfully compress peripheral nerves and potentially damage them. Thus, evolutionary pressures shaping the PNS favor robustness and regeneration rather than conservation of space. Myelin in the PNS is generated by Schwann cells (Fig. 3.9), which are different to oligodendrocytes in several ways. Individual myelinating Schwann cells form a single internode. The biochemical composition of PNS and CNS myelin differs, as discussed later. Unlike oligodendrocytes, Schwann cells secrete copious extracellular matrix components and produce a basal lamina “sleeve” that runs the entire length of myelinated axons. Schwann cell and fibroblast-derived collagens prevent normal wear-and-tear compression damage. Schwann cells also respond vigorously to injury, in common with astrocytes but unlike oligodendrocytes. Schwann cell growth factor secretion, debris removal by Schwann cells after injury, and the axonal guidance function of the basal lamina are responsible for the exceptional regenerative capacity of the PNS compared with the CNS.

Figure 3.9 An “unrolled” Schwann cell in the PNS is illustrated in relation to the single axon segment that it myelinates. The broad stippled region is compact myelin surrounded by cytoplasmic channels that remain open even after compact myelin has formed, allowing an exchange of materials among the myelin sheath, the Schwann cell cytoplasm, and perhaps the axon as well.

The major integral membrane protein of peripheral nerve myelin is protein zero (P0), a member of a very large family of proteins termed the immunoglobulin gene superfamily. This protein makes up about 80% of the protein complement of PNS myelin. Interactions between the extracellular domains of P0 molecules expressed on one layer of the myelin sheath with those of the apposing layer yield a characteristic regular periodicity that can be seen by thin section electron microscopy (Fig. 3.7). This zone, called the intraperiod line, represents the extracellular apposition of the myelin bilayer as it wraps around itself. On the other side of the bilayer, the cytoplasmic side, the highly charged P0 cytoplasmic domain probably functions to neutralize the negative charges on the polar head groups of the phospholipids that make up the plasma membrane itself, allowing the membranes of the myelin sheath to come into close apposition with one another. In electron microscopy, this cytoplasmic apposition appears darker than the intraperiod line and is termed the major dense line. In peripheral nerves, although other molecules are present in small quantities in compact myelin and may have important functions, compaction (i.e., the close apposition of membrane surfaces without intervening cytoplasm) is accomplished solely by P0–P0 interactions at both extracellular and intracellular (cytoplasmic) surfaces.

Curiously, P0 is present in the CNS of lower vertebrates such as sharks and bony fish, but in terrestrial vertebrates (reptiles, birds, and mammals), P0 is limited to the PNS. CNS myelin compaction in these higher organisms is subserved by proteolipid protein (PLP) and its alternate splice form, DM-20. These two proteins are generated from the same gene, both span the plasma membrane four times, and differ only in that PLP has a small, positively charged segment exposed on the cytoplasmic surface. Why did PLP/DM-20 replace P0 in CNS myelin? Manipulation of PLP and P0 in CNS myelin established an axonotrophic function for PLP in CNS myelin. Removal of PLP from rodent CNS myelin altered the periodicity of compact myelin and produced a late onset axonal degeneration (Griffiths et al., 1998). Replacing PLP with P0 in rodent CNS myelin stabilized compact myelin but enhanced the axonal degeneration (Yin et al., 2006). These observations indicate that myelination provides trophic support that is essential for axon survival. Studies of primary demyelinating diseases, such as multiple sclerosis, and genetic dysmyelinating diseases (e.g., Charcot-Marie-Tooth diseases) indicate that axonal degeneration is the major cause of permanent disability (Nave & Trapp, 2008).

Myelin membranes also contain a number of other proteins such as the myelin basic protein, which is a major CNS myelin component, and PMP-22, a protein that is involved in a form of peripheral nerve disease. A large number of naturally occurring gene mutations can affect the proteins specific to the myelin sheath and cause neurological disease. In animals, these mutations have been named according to the phenotype that is produced: the shiverer mouse, the shaking pup, the rumpshaker mouse, the jumpy mouse, the myelin-deficient rat, the quaking mouse, and so forth. Many of these mutations are well characterized and have provided valuable insights into the role of individual proteins in myelin formation and axonal survival.

Astrocytes Play Important Roles in CNS Homeostasis

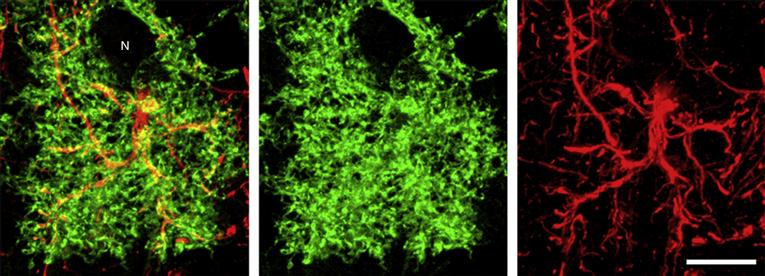

As the name suggests, astrocytes were first described as star-shaped, process-bearing cells distributed throughout the central nervous system. They constitute from 20 to 50% of the volume of most brain areas. Astrocytes appear stellate when stained using reagents that highlight their intermediate filaments but have complex morphologies when their entire cytoplasm is visualized (Fig. 3.10). The two main forms, protoplasmic and fibrous astrocytes, predominate in gray and white matter, respectively (Fig. 3.11). Embryonically, astrocytes develop from radial glial cells, which transversely compartmentalize the neural tube. Radial glial cells serve as scaffolding for the migration of neurons and play a critical role in defining the cytoarchitecture of the CNS (Fig. 3.12). As the CNS matures, radial glia retract their processes and serve as progenitors of astrocytes. However, some specialized astrocytes of a radial nature are still found in the adult cerebellum and the retina and are known as Bergmann glial cells and Müller cells, respectively.

Figure 3.10 Astrocytes appear stellate when their intermediate filaments are stained (red, GFAP), but membrane labeling (green, membrane-associated EGFP) highlights the profusion of fine cellular processes that intercalate among other neuropil elements such as synapses and neurons (N). Scale bar = 10 µm.

Image courtesy of Dr. M. C. Smith.

Figure 3.11 The arrangement of astrocytes in human cerebellar cortex. Bergmann glial cells are in red, protoplasmic astrocytes are in green, and fibrous astrocytes are in blue.

Figure 3.12 Radial glia perform support and guidance functions for migrating neurons. In early development, radial glia span the thickness of the expanding brain parenchyma. (Inset) Defined layers of the neural tube from the ventricular to the outer surface: VZ, ventricular zone; IZ, intermediate zone; CP, cortical plate; MZ, marginal zone. The radial process of the glial cell is indicated in blue, and a single attached migrating neuron is depicted at the right.

Astrocytes “fence in” neurons and oligodendrocytes. Astrocytes achieve this isolation of the brain parenchyma by extending long processes projecting to the pia mater and the ependyma to form the glia limitans by covering the surface of capillaries and by making a cuff around the nodes of Ranvier. They also ensheath synapses and dendrites and project processes to cell somas (Fig. 3.13). Astrocytes are connected to each other, and to oligodendrocytes, by gap junctions, forming a syncytium that allows ions and small molecules to diffuse across the brain parenchyma. Astrocytes have in common unique cytological and immunological properties that make them easy to identify, including their star shape, the glial end feet on capillaries, and a unique population of large bundles of intermediate filaments. These filaments are composed of an astroglial-specific protein commonly referred to as glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP). S-100, a calcium-binding protein, and glutamine synthetase are also astrocyte markers. Ultrastructurally, gap junctions (connexins), desmosomes, glycogen granules, and membrane orthogonal arrays are distinct features used by morphologists to identify astrocytic cellular processes in the complex cytoarchitecture of the nervous system.

Figure 3.13 Astrocytes (in orange) are depicted in situ in schematic relationship with other cell types with which they are known to interact. Astrocytes send processes that surround neurons and synapses, blood vessels, and the region of the node of Ranvier and extend to the ependyma, as well as to the pia mater, where they form the glial limitans.

For a long time, astrocytes were thought to physically form the blood–brain barrier (considered later in this chapter), which prevents the entry of cells and diffusion of molecules into the CNS. In fact, astrocytes are indeed the blood–brain barrier in lower species. However, in higher species, astrocytes are responsible for inducing and maintaining the tight junctions in endothelial cells that effectively form the barrier. Astrocytes also take part in angiogenesis, which may be important in the development and repair of the CNS. Their role in this important process is still poorly understood.

Astrocytes Have a Wide Range of Functions

There is strong evidence for the role of radial glia and astrocytes in the migration and guidance of neurons in early development. Astrocytes are a major source of extracellular matrix proteins and adhesion molecules in the CNS; examples are nerve cell–nerve cell adhesion molecule (N-CAM), laminin, fibronectin, cytotactin, and the J-1 family members janusin and tenascin. These molecules participate not only in the migration of neurons, but also in the formation of neuronal aggregates, so-called nuclei, as well as networks.

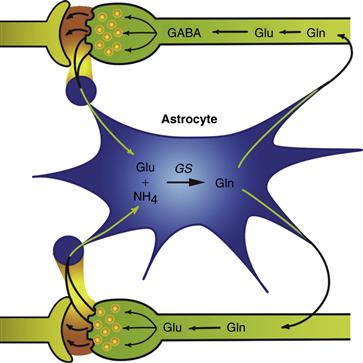

Astrocytes produce, in vivo and in vitro, a very large number of growth factors. These factors act singly or in combination to selectively regulate the morphology, proliferation, differentiation, or survival, or all four, of distinct neuronal subpopulations. Most of the growth factors also act in a specific manner on the development and functions of astrocytes and oligodendrocytes. The production of growth factors and cytokines by astrocytes and their responsiveness to these factors is a major mechanism underlying the developmental function and regenerative capacity of the CNS. During neurotransmission, neurotransmitters and ions are released at high concentration in the synaptic cleft. The rapid removal of these substances is important so that they do not interfere with future synaptic activity. The presence of astrocyte processes around synapses positions them well to regulate neurotransmitter uptake and inactivation (Kettenman & Ransom, 1995). These possibilities are consistent with the presence in astrocytes of transport systems for many neurotransmitters. For instance, glutamate reuptake is performed mostly by astrocytes, which convert glutamate into glutamine and then release it into the extracellular space. Glutamine is taken up by neurons, which use it to generate glutamate and GABA, potent excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters, respectively (Fig. 3.14). Astrocytes contain ion channels for K+, Na+, Cl-, HCO3-, and Ca2+, as well as displaying a wide range of neurotransmitter receptors. K ions released from neurons during neurotransmission are soaked up by astrocytes and moved away from the area through astrocyte gap junctions. This is known as spatial buffering. Astrocytes play a major role in detoxification of the CNS by sequestering metals and a variety of neuroactive substances of endogenous and xenobiotic origin.

Figure 3.14 The glutamate–glutamine cycle is an example of a complex mechanism that involves an active coupling of neurotransmitter metabolism between neurons and astrocytes. The systems of exchange of glutamine, glutamate, GABA, and ammonia between neurons and astrocytes are highly integrated. The postulated detoxification of ammonia and the inactivation of glutamate and GABA by astrocytes are consistent with the exclusive localization of glutamine synthetase in the astroglial compartment.

In response to stimuli, intracellular calcium waves are generated in astrocytes. Propagation of the Ca2+ wave can be visually observed as it moves across the cell soma and from astrocyte to astrocyte. The generation of Ca2+ waves from cell to cell is thought to be mediated by second messengers, diffusing through gap junctions (see Chapter 10). In the adult brain, gap junctions are present in all astrocytes. Some gap junctions also have been detected between astrocytes and neurons. Thus, they may participate, along with astroglial neurotransmitter receptors, in the coupling of astrocyte and neuron physiology.

In a variety of CNS disorders—neurotoxicity, viral infections, neurodegenerative disorders, HIV, AIDS, dementia, multiple sclerosis, inflammation, and trauma—astrocytes react by becoming hypertrophic and, in a few cases, hyperplastic. A rapid and huge upregulation of GFAP expression and filament formation is associated with astrogliosis. The formation of reactive astrocytes can spread very far from the site of origin. For instance, a localized trauma can recruit astrocytes from as far as the contralateral side, suggesting the existence of soluble factors in the mediation process. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and ciliary neurotrophic factors (CNTF) have been identified as key factors in astrogliosis.

Microglia Are Mediators of Immune Responses in Nervous Tissue

The brain traditionally has been considered an “immunologically privileged site,” mainly because the blood–brain barrier normally restricts the access of immune cells from the blood. However, it is now known that immunological reactions do take place in the central nervous system, particularly during cerebral inflammation. Microglial cells have been termed the tissue macrophages of the CNS, and they function as the resident representatives of the immune system in the brain. A rapidly expanding literature describes microglia as major players in CNS development and in the pathogenesis of CNS disease.

The first description of microglial cells can be traced to Franz Nissl (1899), who used the term “rod cell” to describe a population of glial cells that reacted to brain pathology. He postulated that rod-cell function was similar to that of leukocytes in other organs. Cajal described microglia as part of his “third element” of the CNS—cells that he considered to be of mesodermal origin and distinct from neurons and astrocytes (Cajal, 1913).

Del Rio-Hortega (1932) distinguished this third element into microglia and oligodendrocytes. He used silver impregnation methods to visualize the ramified appearance of microglia in the adult brain, and he concluded that ramified microglia could transform into cells that were migratory, ameboid, and phagocytic. Indeed, a hallmark of microglial cells is their ability to become reactive and to respond to pathological challenges in a variety of ways. A fundamental question raised by del Rio-Hortega’s studies was the origin of microglial cells. Some questions about this remain even today.

Microglia Have Diverse Functions in Developing and Mature Nervous Tissue

On the basis of current knowledge, it appears that most ramified microglial cells are derived from bone marrow–derived monocytes, which enter the brain parenchyma during early stages of brain development. These cells help phagocytosis degenerating cells that undergo programmed cell death as part of normal development. They retain the ability to divide and have the immunophenotypic properties of monocytes and macrophages. In addition to their role in remodeling the CNS during early development, microglia secrete cytokines and growth factors that are important in fiber tract development, gliogenesis, and angiogenesis. They are also the major CNS cells involved in presenting antigens to T lymphocytes. After the early stages of development, ameboid microglia transform into the ramified microglia that persist throughout adulthood (Altman, 1994).

Little is known about microglial function in the healthy adult vertebrate CNS. Microglia constitute a formidable percentage (5–20%) of the total cells in the mouse brain. Microglia are found in all regions of the brain, and there are more in gray than in white matter. The neocortex and hippocampus have more microglia than the brainstem or cerebellum. Species variations also have been noted, as human white matter has three times more microglia than rodent white matter.

Microglia usually have small rod-shaped somas from which numerous processes extend in a rather symmetrical fashion. Processes from different microglia rarely overlap or touch, and specialized contacts between microglia and other cells have not been described in the normal brain. Although each microglial cell occupies its own territory, microglia collectively form a network that covers much of the CNS parenchyma. Because of the numerous processes, microglia present extensive surface membrane to the CNS environment. Regional variation in the number and shape of microglia in the adult brain suggests that local environmental cues can affect microglial distribution and morphology. On the basis of these morphological observations, it is likely that microglia play a role in tissue homeostasis. The nature of this homeostasis remains to be elucidated. It is clear, however, that microglia can respond quickly and dramatically to alterations in the CNS microenvironment.

Microglia Become Activated in Pathological States

“Reactive” microglia can be distinguished from resting microglia by two criteria: (1) change in morphology and (2) upregulation of monocyte–macrophage molecules (Fig. 3.15). Although the two phenomena generally occur together, reactive responses of microglia can be diverse and restricted to subpopulations of cells within a microenvironment. Microglia not only respond to pathological conditions involving immune activation, but also become activated in neurodegenerative conditions that are not considered immunity-mediated (Graeber, 2010; Naert & Rivest, 2011). This latter response is indicative of the phagocytic role of microglia. Microglia change their morphology and antigen expression in response to almost any form of CNS injury.

Figure 3.15 Activation of microglial cells in a tissue section from human brain. Resting microglia in normal brain (A). Activated microglia in diseased cerebral cortex (B) have thicker processes and larger cell bodies. In regions of frank pathology (C) microglia transform into phagocytic macrophages, which can also develop from circulating monocytes that enter the brain. Arrow in B indicates rod cell. Sections stained with antibody to ferritin. Scale bar = 40 µm.

Cerebral Vasculature

The cerebral vasculature supports the development and function of the brain. It is composed of a dense network of arterioles, veinules, and capillaries. Figure 3.16 provides an example of the microvascular density across neocortical layers in a mouse brain. During embryogenesis, the brain vasculature develops via the process of angiogenesis from a preformed perineural vascular plexus. The formation of closed neurovascular networks requires the ordered and coordinated action of neural and endothelial signaling factors, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which is produced in the neuroepithelium and attracts vessel growth into the brain. Other factors, including insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), basic fibroblast growth factors (bFGFs), interleukin-8 (IL-8), erythropoietin, and angiopoietin-1, promote the recruitment, proliferation, and survival of endothelial cells while simultaneously promoting the proliferation of neural progenitors, neurogenesis, synaptogenesis, and axonal growth. Many neurogenic factors, including nerve growth factor (NGF), brain derived growth factor (BDNF), neuropilin, glial derived growth factor (GDNF), and artemin, as well as components of the extracellular matrix (ECM), affect both neurons and endothelial cells. The vasculature also contributes to neurogenesis by providing a vascular niche for the resident neural progenitor population that exists in neurogenic regions of the adult brain (Ihrie & Alvarez-Buylla, 2011).

Figure 3.16 Microvasculature of the adult mouse somatosensory barrel field (S1BF) cortex. Microvessels were stained with antibodies against collagen type IV, a protein component of the extracellular matrix, and lightly counter-stained with cresyl violet (Nissl). Cortical layers (I–VI) and the corpus callosum (CC) are indicated. An area of increased vascular density in layer IV, where contralateral somatosensory inputs from the thalamus terminate, is indicated by an arrow. Scale bar = 50 µm.

During angiogenesis, endothelial cells proliferate and migrate to form capillary networks, initially aligning into multicellular, precapillary cord-like structures that form an integrated polygonal network. As the vascular cords mature, lumens form and allow blood flow, and endothelial cells become sequestered from the interstitial matrix by a continuous lamina of ECM that forms a basement membrane or basal lamina. The vascular ECM is a hyaline rich and amorphous substance containing laminins, which are thought to be the primary glycoprotein determinants of basement membrane assembly, along with collagen type IV, perlecan (heparan sulfate proteoglycan-2), nidogens, collagen type XVIII, and fibronectin. Structurally, the ECM supports vascular organization as well as playing a mechanosensing role.

Endothelial cells adhere to the ECM through both integrin and nonintegrin receptors. These interactions result in activation of a complex set of signaling pathways that include Rho GTPases (including Cdc42 and Rac1), focal adhesion kinase (FAK), protein kinase Cε (PKCε), and Src. MAPK signaling is particularly important in the regulation of endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and survival. Although these pathways have diverse targets, one common theme is that most affect directly or indirectly the endothelial cytoskeleton. Regulation of ECM structure and function is primarily achieved through the action of matrix metalloproteases (MMPs), which degrade ECM components and release ECM-bound factors such as cytokines that affect vascular cell behavior (Davis, Stratman, Sacharidou, & Koh, 2011).

Transport of Molecules into the Brain

As an extension of the systemic circulation, the cerebral vasculature delivers oxygen and nutrients into the brain and removes carbon dioxide and other metabolic wastes. Endothelial cells interact with neurons, astrocytes, and microglia, as well as other perivascular cells, including smooth muscle cells and pericytes, to form a neurovascular unit (Lecrux & Hamel, 2011) (Fig. 3.17). This structural organization maintains cerebral homeostasis and also forms a blood–brain barrier (BBB) that restricts exchange of solutes between the systemic circulation and brain. Unlike the fenestrated capillaries most often found in the periphery, the spaces between endothelial cells in brain capillaries are occluded by tight junctions (also known as zonula occludens) that form the physical basis for the BBB by restricting the paracellular movement of molecules into the brain. The tight junctions between endothelial cells are localized at cholesterol-rich regions along the plasma membrane containing caveolin-1 (Cav-1) and are composed of tetraspan transmembrane proteins (claudins and occludin) and single-span cytoplasmic proteins (junction adhesion molecules or JAM proteins). Adaptor proteins, such as ZO-1, link both classes of proteins to the actin cytoskeleton as well as to other signaling molecules. These junctions seal the paracellular space, although they remain capable of rapid modulation and regulation. Consequently, the only solutes that can passively enter the brain are lipid soluble and able to freely diffuse across endothelial cell membranes.

Figure 3.17 Ultrastructural analysis of the cerebral microvasculature of a 10-month-old wild-type mouse. A transversely sectioned capillary is shown from the prefrontal cortex. An endothelial cell (E) surrounding the lumen, a pericyte (P), and an astrocytic end-foot process (A) are indicated. Scale bar = 1 µm.

The presence of a functional BBB means that most substances entering the brain must do so by carrier- or receptor-mediated mechanisms. Some molecules cross the BBB by clathrin-mediated endocytosis. However, in addition to clathrin-mediated transport, the plasma membranes of brain endothelia are enriched in membrane lipid rafts, called caveolae, that participate in potocytosis, a type of endocytosis by which small molecules are transported across the plasma membrane by caveolae rather than clathrin-coated vesicles. Select plasma proteins are, for example, taken up and transported across endothelial cell membranes by both receptor-mediated and receptor-independent transcytosis (transport across the interior of the cell from blood to interstitial fluid or vice versa) involving caveolae. Caveolar membranes, in addition to containing structural proteins including the caveolins (Cav-1 and 2 in endothelial cells and Cav-3 in astrocytes) and cavin (abundant at the cytoplasmic face of caveolae), also contain a variety of signaling molecules (G-protein-coupled receptors, G-proteins, non-receptor tyrosine kinases, nonreceptor Ser/Thr kinases, GTPases, and adaptor proteins). Caveolae are also enriched in β-D-galactosyl and β-N-acetylglucosaminyl residues, cholesterol, sphingolipids (sphingomyelin and glycosphingolipids), as well as palmitoleic and stearic acids. Following the BBB breakdown that occurs with acute injuries to the brain, caveolae can fuse to form transendothelial channels that extend from the luminal to the abluminal plasma membrane, which allows passage of macromolecules from the blood to the brain and vice versa, a phenomenon that has not been observed in normal brain endothelium (Nag, Kapadia, & Stewart, 2011; Redzic, 2011).

The high metabolic rate within the brain is dependent on a continuous supply of glucose from the circulation; under normal conditions, glucose is the main source of metabolic energy. Because glucose does not readily cross the BBB, mechanisms have evolved for the transcellular transport of glucose from the blood to the brain interstitial fluid. In the brain, the main glucose transporters are glucose transporter 1 (GLUT-1) in microvascular endothelial cells and glia, and GLUT-3 in neurons. These insulin-insensitive glucose transporters are constitutively expressed on the cell surface. In endothelial cells, the concentration of GLUT-1 is higher on the abluminal surface. Capillary densities in different brain regions are directly related to local blood flow, and close correlations exist between local cerebral glucose utilization, local densities of GLUT-1 and GLUT-3, and local capillary density. Moreover, the pericytes, which are contractile cells, regulate the distribution of the capillary blood flow to match the local cerebral metabolic need (Dalkara, Gursoy-Ozdemir, & Yemisci, 2011).

The BBB also limits the diffusion of other circulating solutes, and independent carrier systems exist for neutral, basic, and acidic amino acids, as well as purines, nucleosides, and monocarboxylic acids, including lactate and pyruvate. Aromatic amino acids serve as precursors for the synthesis of the neurotransmitters serotonin, dopamine, and histamine, and the synthesis of these neurotransmitters is substrate limited. Cerebral endothelial cells express specific solute carrier proteins (SLCs) that mediate the entry and efflux of amino acids across the luminal and abluminal surfaces of the BBB. Both Na+-dependent and -independent systems have been identified. Na+-independent amino acid transport systems that have been identified in brain capillary endothelium are system L (or a high-affinity isoform L1) for large neutral amino acids (including L-leucine, L-phenylalanine, L-isoleucine, L-methionine, L-valine); system y+ for the transport of cationic amino acids (L-arginine, L-lysine, L-ornithine), and system xc- for anionic amino acids (cystine/glutamate exchange transporter system). Na+-dependent transport systems present in brain endothelial cells include systems A and ASC, which show preference for small neutral amino acids (L-alanine, L-serine, L-cysteine), system Bo,+ for both neutral and basic amino acids, system XAG- for L-glutamate and L-aspartate, and system β (also Cl--dependent) for β-amino acids β-alanine and taurine. The anionic amino acid transport systems are important in the inactivation of glutamatergic neurotransmission in the brain and for the synthesis of glutathione. The high-affinity Na+-dependent transporters are located principally in the abluminal membrane of the cerebral endothelium (Broer & Palacin, 2011; Mann, Yudilevich, & Sobrevia, 2003).

The Cerebral Vasculature in Disease States

Many disease states affect the cerebral vasculature. Occlusive cerebral vascular disease can affect both large and small cerebral vessels, causing ischemia of cerebral tissue and resulting acutely in stroke. By contrast, more chronic cerebral ischemia can result in slow, progressive cognitive impairment and vascular dementia. The integrity of the BBB is also affected in a variety of conditions (Nag et al., 2011). For example, brain tumors often disrupt the BBB, causing fluid to leak into brain tissue. The vasogenic edema that results is often associated with neurological impairment beyond the effects of the tumor itself. A variety of inflammatory and infectious conditions also disrupt the BBB. In multiple sclerosis, inflammatory T lymphocytes cross the BBB and initiate an autoimmune attack on central nervous system (CNS) myelin. Treatment modalities often target the effects of an altered BBB, such as the use of corticosteroids in patients with brain tumors or CNS disorders associated with autoimmunity.

References

1. Altman J. Microglia emerge from the fog. Trends in Neurosciences. 1994;17:47–49.

2. Ascoli GA, Alonso-Nanclares L, Anderson SA, et al. Petilla Terminology: Nomenclature of features of GABAergic interneurons of the cerebral cortex. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2008;9:557–568.

3. Bennett MV, Zukin RS. Electrical coupling and neuronal synchronization in the Mammalian brain. Neuron. 2004;41:495–511.

4. Brodal A. Neurological anatomy in relation to clinical medicine 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 1981.

5. Broer S, Palacin M. The role of amino acid transporters in inherited and acquired diseases. The Biochemical Journal. 2011;436:193–211.

6. Bunge RP. Glial cells and the central myelin sheath. Physiological Reviews. 1968;48:197–251.

7. Cajal SR. Histologie du Système Nerveux de l’Homme et des Vertébrés Paris, France: Maloine; 1909–1911.

8. Cajal SR. Contribucion al conocimiento de la neuroglia del cerebro humano. Trabajos del Laboratorio de Investigaciones Biologicas. 1913;11:255–315.

9. Dalkara T, Gursoy-Ozdemir Y, Yemisci M. Brain microvascular pericytes in health and disease. Acta Neuropathologica. 2011;122:1–9.

10. Davis GE, Stratman AN, Sacharidou A, Koh W. Molecular basis for endothelial lumen formation and tubulogenesis during vasculogenesis and angiogenic sprouting. International Review of Cell and Molecular Biology. 2011;288:101–165.

11. Del Rio-Hortega P. Microglia. In: Penfield W, ed. New York: Harper (Hoeber); 1932;481–534. Cytology and cellular pathology of the nervous system. Vol. 2.

12. DeFelipe J. Chandelier cells and epilepsy. Brain. 1999;122:1807–1822.

13. DeFelipe J. Cortical interneurons: from Cajal to 2001. In: Azmitia E, DeFelipe J, Jones EG, Rakic P, Ribak C, eds. Elsevier 2002;215–238. Progress in Brain Research: Changing Views of Cajal’s Neuron. Vol. 136.

14. DeFelipe J. The evolution of the brain, the human nature of cortical circuits, and intellectual creativity. Frontiers in Neuroanatomy. 2011;5:29 http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fnana.2011.00029.

15. Golgi C. Sulla struttura della sostanza grigia del cervello (Comunicazione preventiva). Gazzetta Medica Italiana Lombardia. 1873;33:244–246.

16. Graeber MB. Changing face of microglia. Science. 2010;330:783–788.

17. Griffiths I, Klugmann M, Anderson T, et al. Axonal swellings and degeneration in mice lacking the major proteolipid of myelin. Science. 1998;280:1610–1613.

18. Howard A, Tamas G, Soltesz I. Lighting the chandelier: new vistas for axo-axonic cells. Trends in Neurosciences. 2005;28:310–316.

19. Ihrie RA, Alvarez-Buylla A. Lake-front property: a unique germinal niche by the lateral ventricles of the adult brain. Neuron. 2011;70:674–686.

20. Jones EG. Varieties and distribution of non-pyramidal cells in the somatic sensory cortex of the squirrel monkey. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1975;160:205–267.

21. Jones EG. Laminar distribution of cortical efferent cells. In: Peters A, Jones EG, eds. New York: Plenum Press; 1984;521–553. Cellular components of the cerebral cortex. Vol. 1.

22. Jones EG. GABAergic neurons and their role in cortical plasticity in primates. Cerebral Cortex. 1993;3:361–372.

23. Kettenman H, Ransom BR, eds. Neuroglia. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1995.

24. Klausberger T, Somogyi P. Neuronal diversity and temporal dynamics: the unity of hippocampal circuit operations. Science. 2008;321:53–57.

25. Klausberger T, Magill PJ, Marton LF, et al. Brain-state- and cell-type-specific firing of hippocampal interneurons in vivo. Nature. 2003;421:844–848.

26. Kubota Y, Shigematsu N, Karube F, et al. Selective coexpression of multiple chemical markers defines discrete populations of neocortical GABAergic neurons. Cerebral Cortex. 2011;21:1803–1817.

27. Lecrux C, Hamel E. The neurovascular unit in brain function and disease. Acta Physiologica 2011.

28. Magloczky Z, Freund TF. Impaired and repaired inhibitory circuits in the epileptic human hippocampus. Trends in Neurosciences. 2005;28:334–340.

29. Mann GE, Yudilevich DL, Sobrevia L. Regulation of amino acid and glucose transporters in endothelial and smooth muscle cells. Physiological Reviews. 2003;83:183–252.

30. Markram H, Toledo-Rodriguez M, Wang Y, Gupta A, Silberberg G, Wu C. Interneurons of the neocortical inhibitory system. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2004;5:793–807.

31. Mountcastle VB. An organizing principle for cerebral function: The unit module and the distributed system. In: Mountcastle VB, Eddman G, eds. The mindful brain: cortical organization and the group-selective theory of higher brain function. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1978;7–50.

32. Naert G, Rivest S. The role of microglial cell subsets in Alzheimer’s disease. Current Alzheimer Research. 2011;8:151–155.

33. Nag S, Kapadia A, Stewart DJ. Review: molecular pathogenesis of blood-brain barrier breakdown in acute brain injury. Neuropathology and Applied Neurobiology. 2011;37:3–23.

34. Nave KA, Trapp BD. Axon-glial signaling and the glial support of axon function. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2008;31:535–561.

35. Nissl F. Über einige Beziehungen zwischen Nervenzellenerkränkungen und gliösen Erscheinungen bei verschiedenen Psychosen. Archiv für Psychologie. 1899;32:1–21.

36. Cellular components of the cerebral cortex. Vol. 1. Peters A, Jones EG, eds. New York: Plenum; 1984.

37. Peters A, Palay SL, Webster HdeF. The fine structure of the nervous system: neurons and their supporting cells 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 1991.

38. Raghanti MA, Spocter MA, Butti C, Hof PR, Sherwood CC. A comparative perspective on minicolumns and inhibitory GABAergic interneurons in the neocortex. Frontiers in Neuroanatomy. 2010;4:3 http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/neuro.05.003.2010.

39. Rakic P. Evolution of the neocortex: a perspective from developmental biology. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2009;10:724–735.

40. Redzic Z. Molecular biology of the blood–brain and the blood–cerebrospinal fluid barriers: similarities and differences. Fluids and Barriers of the CNS. 2011;8:3.

41. Ritchie JM. Physiological basis of conduction in myelinated nerve fibers. In: Morell P, ed. Myelin. New York: Plenum; 1984;117–146.

42. Rossier J. Wiring and plumbing in the brain. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2009;3:2 http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/neuro.09.002.2009.

43. van Domburg PHMF, ten Donkelaar HJ. The human substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area. Advances in Anatomy, Embryology, and Cell Biology. 1991;121:1–132.

44. Yin X, Baek RC, Kirschner DA, et al. Evolution of a neuroprotective function of central nervous system myelin. Journal of Cell Biology. 2006;172:469–478.

45. Yizhar O, Fenno LE, Davidson TJ, Mogri M, Deisseroth K. Optogenetics in neural systems. Neuron. 2011;71:9–34.

Suggested Readings

1. Allaman I, Bélanger M, Magistretti PJ. Astrocyte-neuron metabolic relationships: for better and for worse. Trends in Neurosciences. 2011;34:76–87.

2. Brightman MW, Reese TS. Junctions between intimately apposed cell membranes in the vertebrate brain. Journal of Cell Biology. 1969;40:648–677.

3. Broadwell RD, Salcman M. Expanding the definition of the BBB to protein. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1981;78:7820–7824.

4. Cardoso FL, Brites D, Brito MA. Looking at the blood–brain barrier: molecular anatomy and possible investigation approaches. Brain Research Reviews. 2010;64:328–363.

5. Gehrmann J, Matsumoto Y, Kreutzberg GW. Microglia: Intrinsic immune effector cell of the brain. Brain Research Reviews. 1995;20:269–287.

6. Kimbelberg H, Norenberg MD. Astrocytes. Scientific American. 1989;26:66–76.

7. Lum H, Malik AB. Regulation of vascular endothelial barrier function. The American Journal of Physiology. 1994;267:L223–L241.

8. Nave KA. Myelination and the trophic support of long axons. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2010;11:275–283.

9. Rosenbluth J. A brief history of myelinated nerve fibers: one hundred and fifty years of controversy. Journal of Neurocytology. 1999;28:251–262.