CHAPTER 12

A Continuation of Capital Structure Theory

This is the second-to-last chapter in this section, which spans Chapters 5 through 13 and focuses on how firms finance themselves as well as what financial policies they should choose. This chapter includes a review of the last seven chapters and is similar to Chapter 6, which introduced M&M and capital structure theory. While Chapter 6 took us through comparative statics, this chapter will extend our discussion to dynamics.

So sit back and enjoy the review. We will indicate the sections during which you should pay more attention. The chapter starts with some fairly simple examples but gets more complex as we develop these examples. It also gets more into the second-order effects of what we have previously discussed. Remember, this is a review; you already know most of the concepts.

We are going to emphasize two approaches here: first, we are going to outline the theory. Second, we will discuss what the empirical research (empirics) shows. For some of this chapter, finance has the theory “down” pretty well (that is, finance is pretty confident of the theory), and the empirics support it (that is, the empirical research is consistent with the theory). For other parts of this chapter, there is a theoretical structure but it is not very realistic or consistent, or the empirical work contradicts itself or has not been done.

A polite way to say all this is that finance changes. Hopefully, if you read our tenth edition of this book in 20 years, it will not be the same book merely updated to kill off the used book market. We would like science to advance. So this chapter will emphasize what we feel confident will last and also discuss the parts of finance theory that we expect to change.

Modern corporate finance started with capital structure theory—specifically, modern corporate finance started with Modigliani and Miller (M&M) in 1958. Bottom line, in the simplest M&M world, capital structure policy is irrelevant. It does not matter. Why doesn't capital structure matter in the simplest M&M world? The simplest M&M world contains perfect markets, an investment policy that is held constant, and no taxes, and under these conditions all financial policies are irrelevant. The proof for this is pretty simple. Under the assumptions in M&M (1958), all financial transactions have NPVs of zero. If every financial transaction is a zero NPV, then financial transactions do not matter, and therefore neither does capital structure. (See Chapter 6 for a detailed explanation.)

By extension, in a simple M&M world, all of the following are irrelevant:

- Capital structure

- Long-term versus short-term debt

- Dividend policy

- Risk management

Now this simple M&M world is what was taught in corporate finance when your authors first took finance courses in the late 1970s. In those courses, the instructor spent two weeks on corporate finance, and that was it. The rest of the courses were about investments (efficient markets, CAPM, option pricing theory, etc.). Since then, the world's, or at least finance academics', view of corporate finance has changed.

In Chapter 6, we listed five major assumptions of M&M theory that we felt were not true. Two assumptions—that there are no taxes (both corporate and personal) and that there are no costs of financial distress—were relaxed in that chapter. Relaxing those two assumptions resulted in the “trade-off” approach to capital structure covered in that chapter.

In this chapter, we will relax these last three assumptions: that transaction costs are zero, that asymmetric information does not exist, and that there are no agency costs. Allowing positive but small transaction costs for issuing debt and equity is relatively minor and does not change the theory much. The last two assumptions—allowing for the existence of asymmetric information about the firm's cash flows and for agency costs (i.e., how capital structure influences the firm's investment decisions)—are much more significant.

Let's start our review with a discussion of Chapter 6. This will cover the static trade-off theory or, as it is sometimes called, the textbook model. The simplest textbook view of optimal capital structure trades off the costs and benefits of debt. The major benefit is the tax shield of debt, which means that firms should want more debt. The major costs are the costs of financial distress, which leads firms to want less debt. The theory does not give you a precise target debt level but rather a range. This trade-off is what Gary Wilson was saying when he talked about how Marriott viewed its capital structure decisions. It is also consistent with the idea that if a firm minimizes its weighted average cost of capital (WACC), it maximizes its stock price.

THE TAX SHIELD OF DEBT

The tax shield of debt depends on both corporate and personal taxes. First, the use of debt reduces the corporate tax bill. This is because the interest payments firms make are tax deductible to the firm. Equity payments made by the firm are not tax deductible to the firm. Personal taxes, however, tend to reduce and partially offset this effect.

How do personal taxes impact a firm's capital structure? The personal tax rate matters because when an investor provides capital to a firm, the proper way to measure the return to the investor is post-tax. Returns to investors can come from equity cash flows (dividends or sales of stock) or interest payments on debt. However, equity cash flows have lower personal tax rates for individual investors than interest payments. This means that, all else equal, an investor will prefer to receive equity cash flows from the firm rather than interest payments. As a consequence, investors require a higher return on debt to compensate for the higher taxes that such investments entail.1 Thus, a firm obtains a tax shield from issuing debt, but it also has to pay a higher interest rate to investors due to the higher personal tax rates the investors are incurring. As a consequence, the effects of corporate and personal taxes on firm value counteract—the corporate tax shield does not depend merely on the corporate tax rate.

How much of the corporate tax shield from debt is offset by personal taxes depends on the various tax rates: the corporate tax rate, the personal tax rate on interest, the personal tax rate on dividends, and the personal tax rate on capital gains. We went through an example of this in Chapter 6. Historically, dividends have sometimes been taxed at the same rate as interest payments and sometimes less. Thus, from a corporate tax point of view, the more debt, the higher the value of the firm. From a personal tax point of view, the higher the proportion of payments from debt, the lower the after-tax payments to the individual investor. This is why there is a trade-off between the corporate and personal taxes.

To summarize: Firms get an advantage from using debt (i.e., firm value goes up). The advantage comes from using the corporate tax shield but is mitigated because of personal taxes.

THE COSTS OF FINANCIAL DISTRESS

Now let us examine the cost side of leverage and discuss the impact of financial distress. The expected cost of financial distress is the probability of distress times the costs a firm will incur if it actually becomes distressed. This is summarized in the following box.

While the probability of distress depends on many things, it depends primarily on cash flow volatility. How do we assess a firm's risk of financial distress? We start with pro forma analyses–by projecting best-case and worst-case scenarios. When doing the pro formas, we want to consider questions such as: Are industry cash flows volatile, is the firm's product market strategy risky, are there uncertainties due to competition, is there risk of technological change, and so on?

These questions require a knowledge of the firm's product market situation. In particular, it requires an anticipation of changes in a firm's product market environment (particularly the introduction of new technology) that can cause a “safe” firm with stable cash flows to become a “risky” firm with volatile or diminished cash flows. These changes in the product market environment are the factors most easily missed in the pro forma analysis.

Let's give a simple example: Kodak film and Kodak photo processing dominated the photography market in the United States for many years. Kodak had some competition from Polaroid but was still the overwhelming market leader. Then Kodak faced competition from Fuji, in particular Fuji film. However, the real blow to Kodak's cash flows was neither Polaroid nor Fuji but rather digital photography—a new technology. This is usually the thing most frequently missed when people consider risk. You know what the current risks are, you worry about your current competitors and the possibility of new ones emerging, but new technology is hard to predict and can completely alter the product market. (We do not have any obvious way to predict this, but you always have to worry about what happens if a new technology takes away the market.)

The costs of financial distress are many. The legal costs are usually small. As we saw in Massey Ferguson, the lawyers and hotel bills may have amounted to millions of dollars, but they were small relative to the total cost of the bankruptcy. By contrast, the legal costs are dwarfed by the potential costs of risk-taking behavior by management (e.g., management gambling by undertaking high-risk projects or postponing necessary capital spending), the loss of management focus (as management becomes involved with the bankruptcy rather than day-to-day operations), or the loss of customers (if a firm faces long-term uncertainty, customers may be reluctant to purchase its products) and suppliers (who are worried about dealing with a bankrupt entity).

Additionally, financially distressed firms sometimes experience a debt overhang, which is when the book value (the principal amount) of the firm's debt is greater than the total value of the firm's assets.2 In that case, the debt holders will receive less than the debt's book value. Firms with a debt overhang have less ability to raise new funds both to undertake required investments and to maintain operations. In addition, these firms may also be forced to forgo new opportunities with positive net present values.

Why would a financially distressed or bankrupt firm be forced to give up new opportunities that are predicted to be profitable? Because investors are reluctant to inject new capital into a debt-overhang situation where they are effectively transferring value to the old debt-holders. Any positive NPV from the new project will first go to the current bondholders because of the overhang and only then to the new investors whose cash financed the project. Thus, with a debt overhang, new financing is difficult to obtain, and firms may be forced to forgo projects with positive NPVs.

Finally, competitors tend to attack firms in bankruptcy. Remember our example of how Massey Ferguson was attacked and lost market share to John Deere domestically and to Korean and Japanese manufacturers internationally.

In a nutshell, a firm's capital structure decision lies with understanding the traits of the industry and company as well as whether the firm is expected to have low or high costs of financial distress.

Looking now at the theoretical and empirical research regarding the benefits of debt tax shields and the costs of financial distress (as discussed in Chapter 6):

- The theory and empirics on both the benefits of tax shields and the costs of financial distress are very strong.

- The theory and empirics on the costs of financial distress being correlated with volatile cash flows are very strong.

- There are clear industry effects when setting firm capital structure. Industries with stable cash flows (e.g., utilities, real estate) have high debt ratios. In contrast, firms in industries with volatile cash flows or where there is a lot of technological change and R&D (e.g., high tech, pharmaceuticals) have very low debt ratios.

- Thus, the theory and empirics are very strong regarding the large differences in capital structures that exist across industries.

In our first theory chapter (Chapter 6), we stated that firms set capital structure by considering three perspectives: internal (what the firm can afford), external (how the market views the firm's capital structure, that is, what the analysts say, what the firm's lenders say, what happens to the firm's debt ratings, etc.), and cross-sectional (what the firm's competitors are doing). This remains a sensible way for a firm to determine its capital structure policy.

TRANSACTION COSTS, ASYMMETRIC INFORMATION, AND AGENCY COSTS

In this chapter, we extend our discussion of capital structure by first relaxing the three remaining key assumptions of an M&M world, which are: transaction costs are zero, there is no asymmetric information, and there are no agency costs.

Transaction costs are not zero in the real world but are very small (relative to total firm value) for all financial transactions that affect capital structure. That includes issuing securities, conducting arbitrage transactions, and direct bankruptcy costs. As such, there is very little theoretical work done on these issues, and the empirical measurements confirm their small size.3

Asymmetric Information

Asymmetric information occurs when managers have more information about the firm than outside investors do. In a pure M&M world this is assumed not to occur. Current finance theory assumes asymmetric information does exist, and the empirical evidence supports this belief. This topic was introduced in Chapter 8 (which dealt with Marriott) and discussed further in Chapters 9 and 10 (which dealt with AT&T and MCI).

In those chapters, we explained that asymmetric information leads to signaling theory where outside investors and analysts depend on “signals” given by firms. Of particular importance are equity cash flows.

Equity cash flows consist of equity issues, stock repurchases, dividend increases, and dividend cuts. Equity cash flows “in” are a negative signal, and the market interpretation is that the firm requires external equity cash flows (internal cash flows are not high enough). Equity cash flows “out” are a positive signal, which the market interprets as the firm having enough excess cash that it can afford to pay some out.

An example is when management decides to have the firm issue stock, sometimes while simultaneously selling some of their holdings.4 This is a strong signal that the stock is overvalued, and the firm's stock price in the market usually declines in response. A contrasting example is when management decides to have the firm repurchase its own stock while not selling any of their own holdings. This is a strong signal that the stock is undervalued, and the market usually increases the firm's stock price. The changes in stock price that typically follow these two examples are due to the fact that the market recognizes and responds to signals.

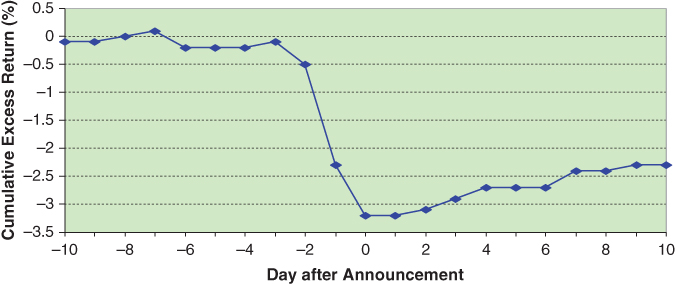

Let's look at the empirics more closely. Figure 12.1, from a paper one of the authors wrote in 1986,5 graphs the average cumulative excess returns for the ten days before until the ten days after equity issue announcements. Excess returns are those above or below what is expected, given the change in the overall market. Basically, you compare the firm's actual return with the firm's expected return calculated using the firm's beta and a simple market model.6 For the 20-day period surrounding the announcement, the average excess return for the stocks of firms that announced equity issues is approximately –3%. That is, the portfolio of stocks that announced equity issues underperformed their market-adjusted equity returns by almost 3%.

FIGURE 12.1 Stock Price Reaction to Equity Issue Announcements

Average cumulative excess returns from 10 days before to 10 days after announcement for 531 common stock offerings (Asquith and Mullins, 1986).

An essential and important point: the decline in stock price when issuing equity does not necessarily mean it is wrong to issue equity. John Deere issued equity, and its stock price fell, but it was still the right thing to do. AT&T issued equity, and its stock price fell, but it was also the right thing to do. While issuing equity is a signaling event that may reduce the stock price, not issuing equity can also be expensive because the funds are needed to support the firm's product market investments. Recall that in Chapter 9, we showed AT&T issued $1 billion of equity, and its market capitalization fell by $2.1 billion. By issuing equity, AT&T signaled that it did not feel its future cash flows and prospects or stock price were as rosy as the market did. AT&T clearly felt that after divestiture, its new competitive world was going to be a lot more difficult.

If AT&T hadn't issued equity, do you still think the stock price would have fallen? It still would have happened. Sooner or later, the market would have figured out what management already knew (that the market had overestimated AT&T's short-term prospects), and the stock price would have eventually gone down. The price just went down faster because AT&T issued equity, which caused the market to realize it sooner. It doesn't mean that without the equity issuance the stock price would have remained high. It also does not mean it is wrong to issue equity.

When John Deere issued $172 million in equity on January 5, 1981, (which we called financial reloading) its market capitalization fell by $241 million that day. (Note: It is unusual for a firm's market capitalization to fall by more than the issue size, though it does happen about 6% of the time.) This does not mean the signal to the market is what destroys value. If management is signaling to the market what the market would shortly realize on its own, then all the signal does is speed up the market's adjustment to the underlying economics. Thus, the signaling effect does not mean it is wrong for management to issue equity.

Firm and Investor Behavior Regarding External Financing

Let us now consider the consequences of asymmetric information between a firm's management and its investors. That is, what would we expect the behavior of the managers and the stock market to be if asymmetric information is the normal state of the world?

With asymmetric information, managers will prefer to issue equity when it is overvalued and will avoid issuing equity when it is undervalued. The theory and empirics of asymmetric information strongly support this conclusion. Furthermore, investors view equity issues as signals. Again the theory and empirics are also very strong.

In addition, as discussed in prior chapters, firms seem to finance investments in the following sequence: first, firms use internally generated funds. Second, firms use debt, either by borrowing from a bank or from capital markets. Lastly, firms obtain funds by issuing equity. This sequence has been referred to as a pecking order.7 The theory behind it is consistent with the concepts of asymmetric information and signaling. The empirics also seem strong.

Recently, however, the argument that firms use internal funds first, then debt, then equity has been challenged by Fama and French (2005), who claim that equity issues are “commonplace.” Well over half their sample firms issued equity during the sample period (1973–2002), but it was usually not issued directly to the market or issued with underwritten offers. Instead it was issued in ways that reduced asymmetric information effects (e.g., issues to employees, rights issues, and direct purchase plans). The results by Fama and French indicate that equity issues (when all types are considered) are a much more important source of funding than previously thought and suggest the pecking order theory may need to be revised.8

Does a firm's willingness to issue equity fluctuate over time? It is not clear. There are theories that argue it does, but none (to our knowledge) have any empirical support. At the same time, we do know from empirical research that equity issues tend to cluster. There are “hot” and “cool” markets. However, we have no good theory to explain it or to provide us with the ability to predict when a market will heat up or cool down.

A related consequence of the pecking order theory (which itself is a consequence of asymmetric information) is that firms may sometimes forgo projects with positive NPVs because of managers' reluctance to raise additional equity financing. Your authors think this part of the theory is not as strong, and the empirical support only exists anecdotally.

To summarize, the static view of a firm's choice between debt and equity as a trade-off between tax shields and the costs of financial distress is not complete because it does not consider asymmetric information (among other things). Adding asymmetric information means the market reacts to a firm's form of financing.

ASYMMETRIC INFORMATION AND FIRM FINANCING

Let us now provide some examples of how asymmetric information works. We will set up financing situations with and without asymmetric information to examine a firm's likely behavior under the alternative scenarios.

Assume Logic Corporation (Logic) has assets currently in place that are subject to the following idiosyncratic risk (specifically, the firm will end up in one of two possible equally likely outcomes):

| Asset Value | Probability | Expected Value |

| $150 million | 50% | $75 million |

| $ 50 million | 50% | $25 million |

This gives an expected firm value of $100 million ($75 million + $25 million).

Also assume Logic is considering a new investment project with the following parameters:

- Investment outlay: $12 million

- A guaranteed return next year: $22 million

- Discount rate: 10%9

- Present value (PV) = $22 million/1.1 = $20 million

- Net present value (NPV) = –$12 million + $20 million = $8 million

Note: To make all of our examples easier, we assume the project itself never has information asymmetry.

We will have two cases: Case 1, with no information asymmetry, and Case 2, with information asymmetry. We will also have two financing scenarios: the first (a) is with internal funds; that is, Logic has enough cash to fund it without raising outside financing. The second (b) is with external funds; that is, Logic does not have enough cash to fund the project internally and must borrow or issue equity. So there are four possibilities in all.

Case 1: There is no information asymmetry (everyone has the same information).

- Scenario a: Logic has enough cash available on hand.

- Scenario b: Logic needs to raise the funds externally.

Case 2: There is information asymmetry (management knows more than investors).

- Scenario a: Logic has enough cash available on hand.

- Scenario b: Logic needs to raise the funds externally.

In all four possibilities let's hold taxes and the costs of financial distress constant. Furthermore, assume the NPV from the new project is achieved with certainty (i.e., investing in this project contains no risk, and the $22 million next year is certain to occur). Thus, the project is like arbitrage—it is a project with a guaranteed NPV of $8 million.

Should Logic do the project? Clearly Logic should: it is a positive-NPV project with no uncertainty. Will Logic do the project? That depends—information asymmetry and the form of financing may affect the firm's decision. Restating the question: Under which possibilities will Logic Corporation undertake the project?

That's the setup. Let's now analyze the possibilities.

Case 1a: There is no information asymmetry, and the firm has enough internal funds. That is, outside investors know as much as managers do, and Logic has $12 million in internal funds available, which it invests in the project. Logic receives the guaranteed present value of $20 million, resulting in a positive NPV of $8 million. Since Logic internally funds the project, its existing shareholders receive the entire $8 million. The project will be done.

Case 1b: There is no information asymmetry, but Logic does not have the necessary internal funds. To raise the funds, Logic issues equity. Now, once the project has been announced, everyone (with no information asymmetry) knows the project is worth $20 million in present value terms. The firm's value will now be $120 million (the current expected value of $100 million plus the additional $20 million from the new project). To raise the required $12 million, Logic issues $12 million of stock. This will represent 10% of the total equity in the firm ($120 million * 10% = $12 million).

In this case, the existing shareholders retain 90% of the stock, which means their equity is now worth $108 million (90% * $120 million). They used to own 100% of the firm when it was worth $100 million. By issuing stock, the existing stockholders may have decreased their percentage ownership, but their equity value has increased from $100 million to $108 million. The project will be done.

Thus, with no information asymmetry the project is done regardless. Managers are indifferent between funding the project internally or funding it externally. Current stockholders (including the managers, if they own any shares) get the same return.

Now, let's make our example more complicated (and probably more realistic).

| Shareholders/Market Believe | Managers Know | ||

| Asset Value | Probability | Asset Value | Probability |

| $150 million | 50% | $150 million | 100% |

| $ 50 million | 50% | $ 50 million | 0% |

Case 2a: There is information asymmetry where managers know more than outside investors. Logic is still the same firm and has internal funds for the project. The additional two columns (under “Managers Know”) indicate that managers have more knowledge than investors, which means there is asymmetric information.

The shareholders and the market still believe the firm will have a value of $150 million with a probability of 50% or a value of $50 million with a probability of 50%. This results in the same expected market value of $100 million. However, in this case, management know that the firm is really worth $150 million (with probability 100%). Thus, the managers know that the firm is currently undervalued.

Logic has the $12 million of internal funds and undertakes the project using them; the outcome looks the same as Case 1a above. Logic does the project, obtains a positive NPV of $8 million, and the current stockholders get the entire $8 million increase.

Thus, when there are internal funds (Cases 1a and 2a) the project gets funded regardless of whether there is information asymmetry or not.

Case 2b: Again, there is information asymmetry, but in this case Logic does not have sufficient internal funds to undertake the project. To raise the funds, Logic will issue equity. The market values the firm at $100 million and the project at $20 million. This means the expected value of the firm will go from $100 million to $120 million. Therefore, to raise $12 million in new equity, Logic has to issue 10% more shares. The existing stockholders will own 90% of the firm after the new equity issue.

Now, in this case the managers know the firm will in fact be worth $170 million (the current $150 million plus $20 million). Thus, if the firm issues 10% new equity, the existing stockholders' shares will be worth $153 million (90% of the $170 million), and the new shareholders' shares will be worth $17 million (10% of the $170 million). If the firm does not issue new equity, the existing shareholders retain 100% of the firm, which is worth $150 million. So, from the perspective of the existing shareholders, how much value does the new project add? $3 million ($153 million – $150 million).

Therefore, of the $8 million NPV from the project, the old shareholders only get $3 million, while the new shareholders get $5 million. This happens because new shares were sold when the market undervalued the firm. This allows the new shareholders to capture some of the upside. In this case, the project also gets done.

However, there could be a situation, which we will describe later, in which more than the entire NPV of the project goes to the new stockholders, and the old stockholders actually lose value. In a world of no information asymmetry, this cannot happen. In a world with information asymmetry and an undervalued stock price, management may not, in some cases, issue additional stock if they think it will go up substantially in price.10

A key point in this analysis: A new equity issue by an undervalued firm entails less value for its current stockholders than internal financing. If a firm is properly valued, or if there is no information asymmetry, it doesn't matter whether the firm uses internal or external financing. However, if the firm is undervalued and there is information asymmetry, then managers will prefer internal financing to issuing equity to outside investors. This is true because by financing internally the current stockholders get all of the upside instead of sharing it.

So we can now say the following: When equity is undervalued, managers prefer internal financing to issuing equity to outside investors.

The next question we will address is: When is new debt preferred to new equity?

Imagine we are in Case 2b above, where there is information asymmetry and insufficient internal funds. Logic needs external financing, and let's assume this time it issues new debt instead of equity. Assume the interest rate Logic must pay on this debt is equal to our discount rate of 10% (which again is the riskless debt rate because the project return is guaranteed). Thus, Logic issues $12 million of new debt and must repay $13.2 million ($12 million + 10% interest). The NPV of the project remains $8 million, which is the future value of the project ($22 million) less the future repayment of the debt ($13.2 million) discounted at the 10% cost of capital (i.e., ($22 – $13.2)/1.1 = $8.8/1.1 = $8.0).

In this case, where the firm issues debt to finance the project, how much would the existing shareholders get? $158 million. Why? The shareholders get the entire current firm value of $150 million plus the $8 million NPV of the project. So, by issuing debt instead of selling stock for $12 million, the old shareholders are able to keep the entire gain of $8 million from the project. This means that firms with undervalued stock and not enough internal funding will prefer to issue debt rather than equity for positive positive-NPV projects.

So we can now state the following: When equity is undervalued, managers prefer debt financing to issuing equity to outside investors.

Note that if managers believe their stock is undervalued, even if it is not, their behavior is the same. They will prefer internal funds and/or debt financing over equity financing.

Now, let's add a subtler point here, one that you have to read textbooks carefully to find. The debt that we are issuing in our earlier examples is “safe” debt. That is, the return to the debt holders is guaranteed. The firm is actually indifferent between using internal funds or safe debt to finance the project. However, if the debt is risky in some way (i.e., not guaranteed and thus lower rated), our examples do not work the same way. With safe debt, the value of the debt is independent of the value of the firm, and asymmetric information does not matter. Managers and the market give this “safe” debt the same price—it is not ever underpriced. If the debt is risky, and the firm is undervalued, the debt holders will obtain some of the upside when the true value of the firm becomes known (though usually less than new shareholders would).

Let's explain the issue of safe versus risky debt using our Case 2b example. Assume Logic has an expected value of $100 million but management knows it is really worth $150 million (i.e., there is information asymmetry, and the firm is undervalued by the market). Also assume the firm intends to borrow the $12 million to finance the new project. Now, if the market knew the firm was really worth $150 million, the debt would be higher rated than if the market thinks the firm is only worth $100 million. Because of this uncertainty over firm value, the interest rate on the debt is above the risk-free rate of 10%. Let us assume the firm has to pay an interest rate of 12%. This means the firm must pay 12% (or $1.44 million) in interest to bondholders, even though its true risk is only 10%. Thus, the bondholders get an extra 2% or $240,000 because of the asymmetric information.

What does the introduction of risky debt mean for our financing decision? With risky debt, the market charges a higher rate of interest. Thus, a firm's first source of funding is internal cash on hand, because it has the lowest cost. Alternatively, a firm would fund with safe debt. Next comes risky debt. Then, at some point, risky debt becomes too expensive (or in reality simply unavailable), and a firm turns to equity. We should therefore update our pecking order to: internal funds = safe debt > risky debt > equity.

The examples above all show that asymmetric information can affect the financing that a firm chooses with a positive-NPV project. Extending our example further, there are cases where asymmetric information may cause firm Logic to reject a positive-NPV investment.

Let's reconsider Case 2b with a higher investment cost for the new project. Assume the cost of the new investment rises to $18 million (instead of the $12 million above). Also assume the present value of the project remains certain at $20 million ($22 million in one year discounted back at 10%). The project still has a positive NPV, but it is reduced from $8 million to $2 million.

If Logic has sufficient internal funds, it invests $18 million and gets $20 million with certainty, and the current shareholders pocket the $2 million increase in value. However, if the firm has to raise the $18 million by issuing new equity, it will have to issue $18 million, or 15% of the firm's total equity ($18 million divided by the firm's expected value of $120 million). This leaves the old stockholders with only 85% of the firm.

Now, the managers know the true value of the firm with the project is $170 million ($150 million + $20 million). If the new project is not undertaken and new equity is not issued, managers know the old shareholders will own 100% of $150 million, compared to owning 85% of $170 million, which is only worth $144.5 million. Thus, in this example, asymmetric information results in the old shareholders being better off by not undertaking a positive-NPV investment.

The theory in this section on how asymmetric information affects investment is very solid and makes intuitive sense. Choosing internal funds, rather than debt or equity, occurs with asymmetric information and positive-NPV projects. Foregoing a project is theoretically possible when the undervaluation is significant and the amount of positive NPV is small. However, we have no idea how often this occurs in practice. This is because we have no idea how often firms actually forgo positive-NPV projects because of asymmetric information—it is difficult to study events that don't happen.

Asymmetric Information and the Timing of Equity Issues

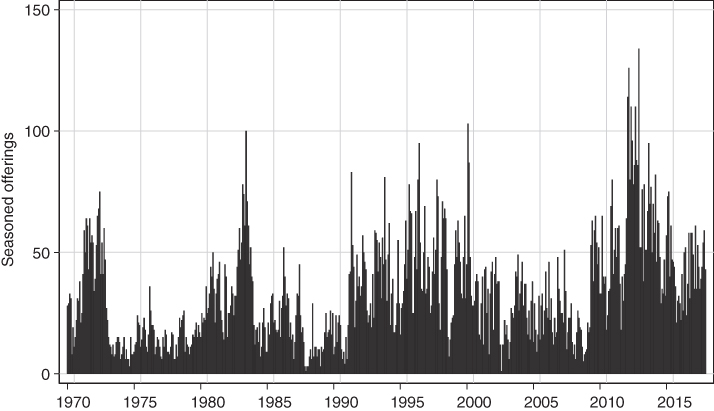

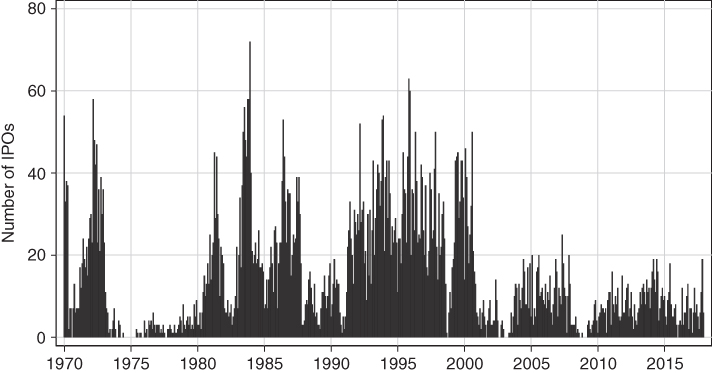

Equity issues do not occur evenly through time. When we plot the occurrence of seasoned equity issues (SEOs) in Figure 12.2 and initial public offerings (IPOs) in Figure 12.3, they appear to cluster. In fact, Wall Street often talks about “hot” and “cool” issue markets. However, while there is no good theory for why SEOs or IPOs might cluster, there are several purported explanations for it. One is that firms tend to issue more equity in market booms (and less in busts) because the NPVs of their investment opportunities are higher, making them more willing to incur the equity issue costs. This might make some sense, but the theory is not well defined, and the clusters don't always coincide with favorable economic conditions.

FIGURE 12.2 Seasoned Equity Offerings (SEOs), 1970–2017

Source: SDC Platinum

FIGURE 12.3 Initial Public Offerings (IPOs), 1985–2017

Source: SDC Platinum

Another explanation is that firms issue equity when the costs of doing so are lower. In other words, there may be “good” and “bad” times to issue stock. One explanation given for why this occurs is the degree of information asymmetry. When information asymmetry is low (high), issuing costs are lower (higher) since the amount by which the market discounts a firm's stock price is less (more). This explanation requires varying levels of information asymmetry for which there is no empirical evidence. This idea is more of a hypothesis than a theory.

Another explanation for the clustering of equity issues is that they are the result of stock market bubbles. For example, during the dot-com bubble of 1997–2000, stocks were valued at unrealistically high multiples, which strongly encouraged firms to issue equity. This explanation would mean the stock market is sometimes inefficient.

So, while we have some explanations, we don't have any good theories. We know by examination that equity issues cluster. Unfortunately, we can't currently explain it based on macro issues, stock market issues, or regulation issues. (Mergers also cluster in the stock market and are referred to as waves, but there is again no theory that explains why.)

In summary, the theories on the tax shields and costs of financial distress are solid and well supported empirically. The theory on information asymmetry makes intuitive sense and works for dividends, stock issuances, and stock repurchases. The pecking order theory also makes sense based on information asymmetry and fits with the empirical data. Regarding the timing of equity issues, however, the explanations are not as convincing, and there is no empirical support.

AGENCY COSTS: MANAGER BEHAVIOR AND CAPITAL STRUCTURE

M&M (1958) assumes that the investment policy of a firm does not change as a function of capital structure. This is because M&M (1958) assumes there are no agency costs for financing. If we relax this assumption, however, the incentives of the firm's managers and hence their behavior may change with the capital structure of the firm.

An agency situation arises when a principal (shareholder) has an agent (manager) working on their behalf. A problem occurs when the managers do not act on behalf of the shareholders but rather act for their own benefit to the detriment of the shareholders. Managers thus maximize their welfare rather than maximizing the stock price. Examples of this may include shirking (managers not working hard enough), empire building (expanding unprofitable divisions), perks (e.g., private jets, art collections, fancy corporate buildings), and unnecessary risk avoidance (not investing in positive-NPV projects that are risky), and so forth.11

How do we minimize agency costs? The typical way firms have attempted to minimize agency problems is to try and align the wealth of the managers with the wealth of the firm. This is seen in compensation policies that do not pay top management a straight salary but rather have part of management's compensation performance linked.

One way to link management's compensation to the firm's performance is by giving managers stock or stock options. If the firm does better, then the managers do better, and their incentives are in line with those of the stockholders.

A second approach is to monitor management's actions. This is done with independent directors (not just internal managers) on the Board of Directors. A firm may also have large block-holders, pension funds, mutual funds, and so on, which may take a more active role on the board than small shareholders can. There is also a market for corporate control, that is, takeovers, which we will discuss later in the book. (Part of the market for corporate control includes takeovers by private equity funds. In these situations, the funds own all of the stock and take a more active role in holding management accountable.)

A third approach, arguably, is the effect of leverage on management's actions. By increasing the leverage of the firm, managers are forced to pay out more cash flows to the debt holders. Since interest payments to debt holders are required, under the threat of bankruptcy, managers have fewer funds to waste.12

A classic, well-studied example of agency costs happened in the 1980s to oil companies. Gulf Oil was spending about $2 billion a year on exploration for new oil. Even though the firm was finding new oil—about $2 billion worth of new oil a year—the problem was that it took an average of seven years to bring the new oil to market. Now, spending $2 billion today to get $2 billion in seven years is a negative-NPV investment, yet Gulf Oil did this over and over and over again. T. Boone Pickens, a well-known corporate raider at the time, noticed this and attempted to take over a number of oil companies with the intent of stopping their negative-NPV exploration. As a result, the management of many oil companies stopped making these negative-NPV investments. (We will go into more detail on this concept of the takeover market limiting managerial discretion later in the book, when we discuss mergers and acquisitions.)

So, if a firm has free cash flows, does increasing leverage reduce agency costs? Debt payments reduce managers' ability to squander funds on pet projects and empire building. Thus, debt can sharpen managers' focus by forcing them to pay debt holders rather than squander the cash flows elsewhere. Paying dividends also uses up free cash flows. However, the promise to pay dividends is not enforceable.

This is the argument for using debt (increasing leverage) to reduce the principal-agent problem between managers and stockholders. It is a good theory; it makes sense. Is the idea of using debt to mitigate the principal-agent problem in publicly traded firms empirically proven? Not quite. We know it works some of the time (we have anecdotal evidence of cases where it works), but we're not sure if it works all of the time.

A Second Principal-Agent Problem: Lazy Managers and the “Quiet Life”

Another principal-agent problem is how to keep managers from becoming complacent. Firms with excess cash flow may see efficiency decline, wages and salaries rise above market levels, loss-making divisions being subsidized by profitable ones, and so on. Increasing leverage puts some pressure on management. For example, Owens Corning Fiberglass, which invented fiberglass, has a nice market niche. While not a monopoly, the firm has a huge market share and a stable, positive cash flow. At one time, the firm had multiple company newsletters (all with a paid editor, photographer, staff, etc.). Find a corporation with multiple newsletters, and you have probably found a corporation in which there is more than a little waste going on. By adding debt and forcing management to make set debt payments every year, the hope is that managers will be forced to be more efficient. The debt holders may provide some monitoring themselves as well. Let's examine this idea in more detail.

There is a large academic literature on leveraged buyouts (LBOs) that examines agency problems and leverage. What we know from this literature is that the LBO structure of high debt tends to solve many agency problems and appears to be valuable in making firms more efficient. For example, in a study of 76 LBOs and management buyouts, Steve Kaplan found that debt went from 19% to 88% (a huge increase). At the same time, operating income to total assets increased, operating income to sales increased, and net cash flows increased.13 In other words, firms became more efficient operationally after they increased debt. Why did firms get more efficient after increasing their leverage? Because they had to (in order to keep up with the large debt repayments); otherwise the firm would be forced into bankruptcy. Kaplan found that LBOs appear to increase efficiency because of increased managerial incentives and because they have better monitoring by creditors.

Private equity firms can have a similar effect to LBOs. There is more debt, but there is also only one stockholder (the private equity firm), better monitoring of management, and better efficiency.

To summarize, LBOs appear to increase efficiency, most likely because of improved managerial incentives and better monitoring by creditors. The theory behind this idea is pretty good. Is the theory that LBOs increase efficiency a proven one? Yes.

LEVERAGE AND AGENCY CONFLICTS BETWEEN EQUITY AND DEBT HOLDERS

While debt may reduce the agency conflict between shareholders and managers, there remains the conflict between shareholders/managers and debt holders. Why? Just as management may have an incentive to transfer wealth from shareholders to themselves, the shareholders/managers may have an incentive to transfer wealth from the debt holders to themselves.

This behavior can take several forms, including increasing the risk of the firm after it has borrowed funds, delaying liquidation in cases of bankruptcy, or looting the company prior to bankruptcy. For example, the investment bank Drexel Burnham Lambert paid out $350 million in bonuses to employees in the three weeks before its bankruptcy filing (on February 13, 1990). Similarly, Merrill Lynch paid out millions in bonuses in the last few months before Bank of America took over (in January 2009).

This behavior does not go unchecked, however. Creditors anticipate these problems and demand covenants and/or higher interest rates for protection. Risky debt requires higher interest rates. Covenants also reduce these conflicts by preventing certain wealth-transferring behavior, although certain covenants seem to work better than others. The theory on all of this is clear, and the empirical evidence is supportive.

Let us now summarize this chapter and draw out its implications by providing you with a set of takeaways.

Takeaway 1: There Is a Trade-Off Between the Tax Advantages and the Additional Financial Risk of Debt

M&M (1963) provides the theoretical underpinnings for the corporate tax advantages of debt. Subsequent theory on the costs of financial distress provides an argument for why leverage should be limited. Together, the theory of capital structure strongly supports a trade-off between increased debt for tax reasons and reduced debt due to the costs of financial distress.

The implication of this trade-off is that there should be industry effects. Firms that are in industries with stable cash flows should have higher leverage ratios than firms in industries with volatile cash flows. This prediction is strongly supported by the evidence.

Takeaway 2: Financial Policies Have Information Content for the Market

Cash flows, in or out of a firm, convey information about the firm. The market believes that “good” firms will first use internal cash and that they will issue debt if they don't have enough internal cash. “Bad firms”—those without internal cash—will issue equity. This explains why the market acts negatively to equity issues. More generally, a firm's financial policies convey information, and stock prices react to changes in those financial policies. Therefore, if a firm changes its dividend policy, equity-issue policy, or stock-repurchase policy, it is not done randomly. It makes sense that managers will be reluctant to undertake policies that lower their firm's stock price. Not only is the theory clear and intuitive, the empirical evidence supports it.

In a study examining 360 firms over a 10-year period (1972–1982), there were only 80 stock issues (which translates to roughly 2% of firms issuing stock in any given year).14 Thus, firms don't issue public equity very often. Which suggests what? First, firms look to internal funding. Second, their preference is to borrow. Lastly, they issue equity if they can't fully fund with the first two options. These three preferences are essentially the pecking order hypothesis.

The empirical evidence is consistent with this pecking order theory. When risky securities are offered, it signals to investors that the firm's managers believe the firm's equity is overvalued. The empirical result is that when firms issue equity, there is an average 3% drop in the firm's stock price, which is about 30% of the issue's proceeds. If a firm issues convertible debt, the drop averages 2% and is about 9% of the issue's proceeds.15 When firms issue debt there is no change in the firm's stock price, on average. When a firm initiates a stock repurchase, the market reaction averages a positive 4% return.

In sum, the empirical work supports the pecking order theory. The initial research on this—in the Asquith Mullins (1986) paper cited earlier—was done 30 years ago using data from 1962 to 1983. Moreover, one of your authors did a recent unpublished update that examined the period from 1962 to 2010 and finds the result still holds. When a firm issues equity, its stock price goes down. When a firm repurchases its shares, its stock price goes up. When a firm increases its dividends, its stock price goes up, and when a firm cut its dividends, its stock price goes down. After 30 years, all the results still hold.

Takeaway 3: The Value of a Project May Depend on Its Financing

Our third takeaway is that the value of a project may depend on its financing. With asymmetric information, the same project is worth more with internal funds than external funds if a firm's stock is currently undervalued. This occurs because the old stockholders share some of the upside with the new stockholders if a firm's stock is undervalued.

The implication of this is that firms will forgo some positive-NPV projects if they can't be internally financed or financed with relatively safe debt (i.e., if they would have to be financed with risky debt or equity). We have no data on how often this occurs in practice, but it can be clearly shown to apply to certain states of the world. This is why firms with less cash and more debt may be prone to underinvest, and we now have a rationale for why some firms hoard cash—or keep “financial slack.”

Now at this point, you may be saying, “Wait a minute. This argues that I am better off issuing debt than equity. But what about the costs of financial distress, don't those mean debt is problematic?” Good question. With the costs of financial distress, firm value decreases with debt issuance. Thus, we have two effects that counteract each other.

Takeaway 4: The Pecking Order Theory of Capital Structure

Our fourth takeaway is that financial choices may be driven by the desire to minimize losses in value due to asymmetric information, resulting in a pecking order. In funding projects, firms will first use retained earnings, then borrow, and only issue equity as a last choice. Additionally, firms with greater information asymmetry have a greater aversion to issuing equity and will try to preserve their borrowing capacity.

That is, the pecking order theory also implies that profitable firms lower their leverage ratios to create “financial slack.” The idea is to avoid future equity issues in case unexpected funding needs arise. Firms with high or low cash flows differ in their ability to do this:

| High-cash-flow firms | ==> No need to raise debt |

| ==> In fact, can repay some debt | |

| ==> Leverage ratio decreases | |

| Low-cash-flow firms | ==> Need to raise debt |

| ==> Reluctance to raise equity | |

| ==> Leverage ratio increases |

A firm with high, stable cash flows has no financing reason to raise debt since it can fund projects internally. In fact, these firms may have enough excess cash to repay their debt and reduce their leverage ratio. In contrast, a firm with low (and perhaps unstable) cash flows will have to raise debt (since, per the pecking order, it is reluctant to issue equity) to fund its projects and increase its leverage ratio. Furthermore, empirically, there are differences not only across industries (pharmaceutical firms have less debt, on average, than utilities) but also within an industry (the most profitable firms in the industry should have lower debt ratios than the least profitable firms).

This appears to violate the trade-off theory (covered in Chapter 6 and takeaway number 1). The trade-off theory says that firms with stable cash flows should have high levels of debt and take advantage of interest tax shields. Firms with risky cash flows should have very little debt because of the costs of financial distress.

Additional empirical research shows that, within a given industry, firms with stable cash flows and lots of cash don't have a lot of debt—they instead have less debt than firms in the same industry that have volatile cash flows and debt. In other words, within a given industry, firms with the most stable cash flows have less debt than those with the least stable cash flows.16

Takeaway 5: Equity Issues Do Not Take Place Evenly over Time

Our fifth takeaway is that equity issues do not take place evenly over time—there are “hot” and “cold” markets for IPOs (initial public offerings) and SEOs (secondary equity offerings). Why? It may be due to differences in the asymmetric information environment and/or differences in market efficiency. We have empirical evidence that equity issues happen in waves, but the theories explaining why this happens are poor. In the language of Wall Street, we can easily tell “stories” of why this happens. Unfortunately, these are just stories. We know equity issues cluster, but have not seen a good, well-tested explanation as to why.

From 1997 to 2000, IPOs of Internet stocks were common, and the multiples on Internet stock were very high (some might say too high). We do not know why, but you could find lots of people at that time who would tell you why (or at least what they thought was the why). However, we have read their arguments and don't believe them. They may be right, but they have no proof; they are simply spinning stories.

Takeaway 6: Hybrid Instruments May Help Firms Mitigate Signaling Effects

Our next takeaway is that hybrid instruments may be attractive as a means of mitigating the signaling effect associated with information asymmetry. For example, convertible bonds can be thought of as “backdoor” equity. What is the idea behind “backdoor” equity? Suppose the firm believes it has good investment opportunities and that the stock price will rise, but the market is not convinced of this. Also assume the firm does not have the internal funds for its investments and its debt is currently costly (risky, low rated). The firm could issue stock but wants to avoid the negative reaction that the market typically has when stock is issued. In addition, the firm does not want to issue new stock too cheaply because it believes better times are ahead. If the firm lacks internal funds, cannot take on debt, and does not want to issue equity, what can it do? Issue a convertible bond, and then force conversion when the stock price goes up—in essence, issuing equity through the back door.

How will the market react to a convertible issue? Presumably less negatively than it would to an external equity issue. Why? If management issues convertibles and future cash flows are not forthcoming, the debt remains and managers have to pay it off or risk bankruptcy (making this costly). Thus, convertibles are more binding on management than external equity, and this is why the market does not view convertibles as strong a negative signal as equity. This is very good theory explaining how convertibles mitigate the signaling effect. There is also empirical evidence to support it: the market's negative reaction to convertible issues is less than the market's negative reaction to external equity issues.

Other examples of hybrid instruments include preference equity redemption cumulative stock (PERCS), which were first issued by Morgan Stanley and consist of convertibles with a mandatory conversion after a fixed number of years, usually three; debt exchangeable to common stock (DECS), which is similar to PERCS but with more conversion options; and short-term equity participation units (STEPS), which are synthetic PERCS that use a portfolio or index rather than a single stock.

Takeaway 7: Agency Problems and Capital Structure

Our final takeaway is as follows: M&M assumes that the firm's real investment policy is unchanged by capital structure. However, we know that capital structure affects managers' incentives and behavior. While some leverage can reduce agency problems, excessive leverage can exacerbate them. It goes back and forth. In an M&M world, investment policy is fixed. In a non-M&M world, investment policy is not fixed, and capital structure can affect the investments a firm chooses to undertake.

Bringing It All Together

Let us review. So far, our checklist for determining capital structure is as follows:

- Taxes. The greater the debt, the larger the tax shield. Debt should be increased to capture a larger tax shield.

- Financial distress. The lower the debt, the lower the expected costs of distress. Debt should be decreased to lower a firm's expected costs of distress.

This is the static optimum theory (discussed in Chapter 6), which depends on a trade-off between the tax shield and the expected costs of financial distress. In this chapter we added:

- Asymmetric information. Debt is preferable to equity because equity is perceived as a negative signal. Asymmetric information creates a preference for debt.

- Agency problems. Uncertain. In some cases, debt may reduce agency problems, but in others it may increase them.

START WITH THE AMOUNT OF FINANCING REQUIRED

Not to be forgotten, when determining capital structure, we must first ask the question: Given a firm's operations and sales forecast, how much funding will be required, and when?

When determining funding, it is important to remember that:

- The concept of sustainable growth does not tell you whether or not growing is good. Just because a business can grow at 10% does not mean it should.

- Sustainable growth is binding only if you cannot or will not raise equity, or let the debt/equity ratio increase.

- Financial and business strategies cannot be set independently.

To answer the question of how much funding and when, we start with pro formas and project both short-term and medium-term future cash flows. In addition, we compute the sustainable growth rate, which is the amount the firm can grow without outside funding.

The cash flow projections in pro formas and the sustainable growth rate together provide a firm with its estimated external funding requirements.

After the funding needs are determined, we now have two major theories for determining what a firm's optimal capital structure should be: the static trade-off theory, which focuses on tax shields and distress costs, and the pecking order theory, which is concerned with asymmetric information. The theories don't have to be incompatible. However, we would suggest that it is best to begin with the static trade-off theory to determine the optimal leverage ratio. Then, as the firm approaches this optimal level, is the time to consider the impact of signaling.

Let's do a sample checklist for two of the firms we have covered so far: Massey Ferguson and Marriott.

Setting a Target Capital Structure: A Checklist

| Massey | Marriott | |

| The corporate tax shield: | ||

| Possible debt tax shield | Yes | Yes |

| Costs of financial distress: | ||

| Cash flow volatility | High | Moderate |

| Need to invest in the product market | High | Low |

| Need for external funds | High | Now Low |

| Competitive threat if pinched for cash | High | Low |

| Customers care about distress | High | Low |

| Structure of debt contracts/ease of renegotiation | A Mess | Simple |

| Assets are easily sold | No | Yes |

| Signaling: | ||

| Asymmetric information high | Yes | Yes |

| Hot issue market | No | No |

| Agency costs: | ||

| Lacks a clear checklist | ? | ? |

Thus, a static assessment would indicate that Massey should have a lower percentage of debt than it did. Both Massey and Marriott benefit from a tax shield, which is an argument to increase debt. However, the two firms have different costs of financial distress. Massey has more volatile cash flows, a greater need to invest, and thus a greater need for external funds. Massey also faces much more competition from other firms if it runs out of cash. This would result in Massey potentially losing more of its market share in the long term if it runs into financial distress. Massey's customers also care about the financial health of the firm since they are dependent on Massey for replacement parts and repairs.

Marriott's cash flows are not as volatile, and its required investment is much lower than Massey's. Furthermore, since switching from hotel ownership to leasing, Marriott's needs for external funding are substantially less. In addition, Marriott's customers are not as concerned about Marriott's long-term health. Marriott customers may stay a night or two as long as the hotel is standing and the room is clean when they arrive; they are not concerned about who the owner of the hotel will be in the future. Thus, the static assessment is that Massey should have a lower percentage of debt.

But let's look beyond the trade-off between the tax shields and the costs of financial distress. Consider that the signaling and the agency costs are similar for Massey and Marriott. First, the two firms are not in difficult industries to understand, nor are the firms themselves overly complex. Thus, the firms' level of information asymmetry is lower than in other industries.

By contrast, consider a pharmaceutical firm. Outside investors are less likely to understand the probability of success for the firm's next generation of products. This creates information asymmetry, which should make pharmaceutical firms much more averse to issuing equity than Massey or Marriott.

Another point of emphasis is that Massey structured its debt using numerous banks in numerous countries, whereas Marriott had one main lender. This would make any negotiations to resolve distress more difficult for Massey.

We would be remiss without mentioning that capital structure theory is not yet finished. Today, five M&M assumptions (taxes, the costs of financial distress, transaction or issuing costs, asymmetric information, and the impact of capital structure on investments and vice versa) have been relaxed and modeled. However, there are other characteristics that are still not properly modeled: the payoff structure, meaning whether debt is fixed or variable; the financing priority structure, meaning why debt is paid before equity and when it should be paid; and the maturity of debt, meaning long-term versus short-term debt.

There are also other characteristics not in the M&M model at all. For example, covenants are not explicitly in the model but we know their value because we can price them. We can also price voting rights, control rights, options, the value of a convertible security, call provisions,17 and so on. We know all these things matter, but finance theory has not yet built a complete model for them. We will not attempt to do so here, since the focus of this chapter is on asymmetric information and agency costs.

SUMMARY

Your authors believe that capital structure should be determined first by using the trade-off theory (taxes vs. costs of financial distress) to establish a long-run, “target” capital structure. (Remember that a careful analysis of firm and industry strategy/structure is needed here.) It is then necessary to consider the signaling costs in the stock price arising from equity issues or dividend cuts.

If the firm has enough internal cash flow, it will worry about the market's reaction to financing decisions only on the margin. If the firm requires outside financing, there may be valid justification for straying from the long-run target leverage. However, a firm should be systematic and precise about any justification. Are the benefits from straying from the target debt level plausibly large relative to costs? The capital structure decision should also avoid unconditional rules of thumb like: “Never issue equity in a down market” or “Don't issue equity if there are convertibles under water.”18 These rules, which are often heard on Wall Street, may make sense in some circumstances, but certainly not in all. The analysis should always be on a case-by-case basis.

Consider four objectives in corporate finance and their trade-offs:

| Corporate Objectives | Trade-Offs |

| 1. Accept all positive-NPV projects | Cut dividends or issue debt to make investments |

| 2. Have an “optimal” debt/equity ratio | Cut investment or issue equity |

| 3. Pay high dividends | Cut investment or raise outside funds to pay dividends |

| 4. Don't issue new equity | Cut investment, cut dividends, or increase debt |

If the firm has lots of positive-NPV investments and insufficient internal funds, the firm has to decide whether to forgo certain investments, cut dividends, or change the debt/equity structure by issuing debt or equity. Objectives 1 and 2 represent the firm's static optimum. Objectives 3 and 4 are a response to signaling. If there is no signaling, then points 3 and 4 are irrelevant (i.e., if there is no market impact from cutting dividends or issuing equity).19 Thus, our two current theories of capital structure are covered in the four objectives above. However, just as the two theories are not completely consistent, neither are the objectives.

We have two important remaining lessons to share:

First, firm value is primarily created in the product market. Firms don't create much value from the finance side of the firm! (The reader should note that this sentence is written by your co-authors, who are both finance professors.) While good financial decisions may increase firm value, the true role of financial decisions is to support and enhance the firm's product market decisions. (We should also note that bad financial decisions can destroy a firm's product market strategy and value.) In addition, a firm cannot make sound financial decisions without knowing the implications for the product market strategy.

Second, we have stated that the product market side of the firm is more important than the financial side; however, this does not mean that finance is not important or that anyone can do it. For many years, MIT operated without a formal CFO. All financial staff at MIT reported to the Provost, making that position the de facto CFO. However, the Provost is an academic position at MIT and is usually filled by a professor from the School of Science or Engineering. Past provosts, while experts in their fields, rarely understood finance. In a meeting some years ago, one of your co-authors stated the following during a discussion about MIT's finance policies: “You wouldn't drive on a bridge that an accountant built, so why the hell would you let an engineer do your finances?” We want to make a similar point at the end of this chapter. Finance is way too important to leave to nonfinancial people. It doesn't make the firm succeed by itself, but it can cause it to fail.

To illustrate these last two points, allow us to tell the following corporate finance joke. (There are not many good corporate finance jokes, but this is one of them.)

We all know that business schools make admission mistakes. In any given class, all the students, except perhaps for the admission mistakes themselves, will know who the mistakes are. They are the people who nobody wants in their study group, the people who no one listens to when they talk in class, and so on.

Now, imagine that 20 years after graduation, you are walking down the street and see one of the admission mistakes from your graduating class walking toward you. You cross to the other side, hoping to avoid him, but he sees you and also crosses the street to meet up with you. After a brief conversation, he insists that you get together at his place Friday night for dinner. You protest but then notice the address and are surprised to see it is an expensive building in the best part of town. You arrive on Friday night and discover that your classmate occupies the two-story penthouse. You walk in and the place is unbelievable. Original artwork on the wall, expensive furniture, clearly money everywhere. You're shocked!

Finally, you can't stand it anymore and ask what he does for a living. He says, “Well, I have a little manufacturing firm. We make kitchen gadgets that wear out in a couple of years and people have to replace them. It costs us a buck to make, and we sell them for eight dollars each! You would really be surprised how fast that eight percent adds up.”

Our point being: If a firm can make something for a buck and sell it for $8 (think of Apple or Intel), then financing doesn't matter all that much. Firms make money on their product side: that's where value is created. Finance is primarily meant to support the product market strategy of the firm.

Coming Attractions

The next chapter looks at how firms restructure their capital structure when cash flows are insufficient to meet debt payments.