CHAPTER 9

Financial Policy Decisions (AT&T: Before and After the 1984 Divestiture)

In this chapter, we are going to discuss financial policies again. This chapter should be read after the chapters on Marriott, where we introduced how financial policies are used to implement financial strategy. Financial policies are an area of corporate finance not typically emphasized in entry-level finance textbooks. We will discuss concepts that investment banks use in doing advisory work. Firms call up their investment bank and ask for advice about setting dividend policy or about achieving a particular bond rating. These are questions a firm asks on an ad hoc basis, although probably not often enough. The questions involve decisions that are made at the CFO level of the firm.

This chapter is not conceptually difficult, but it is complicated because of the number of moving parts. The focus of most finance jobs, in either a firm's corporate finance department or in an investment bank, involves valuations and is transaction oriented. Thus, most of a finance professional's time is spent using models to value potential investments, either in new plants or in corporate acquisitions.

In this chapter, we are going to review and provide some more practical examples of financial policies. We will explore the financial policies of the “old” AT&T (before the breakup on January 1, 1984) to determine how well the firm's financial policies met its financing needs. Then we will briefly examine the “new” AT&T (post–January 1, 1984, after the breakup) and discuss how the firm's financial policies changed with the change in its financing needs as well as whether the changes were correct.

This chapter is paired with the following one on MCI and is meant to be a compare-and-contrast example. We look at two very different firms in the same industry at the same point in time to talk about the financial policies that are appropriate for each firm.

We begin by focusing on capital structure and everything it entails. By “capital structure” we don't mean just debt and equity but also maturity structure, fixed versus floating interest rates, and so on. We are also going to look at dividend policy and what it implies for financing, because when a firm pays out dividends, the cash paid out must be generated elsewhere. Lastly, we are going to introduce security issuance and design. We will first cover all of these topics in a static framework, as we have done in previous chapters.

Your authors believe that if you can understand the impact that AT&T's change in operations had on the firm's financial ratios and thus on its sustainable growth rate, and if, by extension, you can understand the impact that the operational change had on AT&T's financing needs, then you have come a long way toward understanding corporate finance.

BACKGROUND ON AT&T

The American Telephone and Telegraph Company (AT&T) was incorporated on March 3, 1885, as a wholly owned subsidiary of American Bell. (It was founded in 1877 by Alexander Graham Bell, who invented the telephone in 1876, and his partners Gardiner Hubbard and Thomas Sanders.) AT&T built America's long-distance telephone network, the Bell System. For much of its history, AT&T functioned as a legally sanctioned, regulated monopoly. The percentage of American households with telephone service reached 50% in 1945, 70% in 1955, and 90% in 1969.

Changes in the telecommunications industry eventually led to an antitrust suit by the U.S. government against AT&T. The suit began in 1974 and was settled in January 1982 (the settlement was approved by the court hearing the case on August 24, 1982), when AT&T agreed to divest itself of the local portions of its 22 wholly owned Bell operating companies that provided local exchange service. These 22 operating companies represented about three-fourths of AT&T's assets at the time. The government wanted to separate those parts of AT&T where the natural monopoly argument was still seen as valid (the local exchanges) from those parts where competition was beneficial (long-distance, manufacturing, and research and development). Divestiture took place on January 1, 1984, resulting in a new AT&T and seven regional Bell operating companies known as the “Baby Bells.”1

Prior to the divestiture, AT&T was the world's largest firm, with sales peaking at almost $68 billion, total assets of over $148 billion, and more than one million employees. After the divestiture, AT&T had revenues of $33 billion, assets of $34 billion, and employed 373,000 people.

AT&T's operations changed dramatically from December 31, 1983, to January 1, 1984. This chapter details the impact of that change on the firm's financial policies in order to highlight how a firm's financial policies are tied to operations and how they are used to implement change. Our AT&T example is set at the end of 1982, just after the divestiture settlement with the government but before the actual divestiture was undertaken.

M&M AND THE PRACTICE OF CORPORATE FINANCE

Let's start with a review of corporate finance and how it has changed over time.

Modern corporate finance theory began with Modigliani and Miller (1958). As we discussed in Chapter 6, Modigliani and Miller (M&M) showed that capital structure did not matter under certain conditions. That is, the value of the firm in a M&M (1958) world did not change with changes in the firm's capital structure. This idea was controversial when first introduced and was rejected by finance practitioners and many finance academics.

However, M&M (1958) assumed zero taxes. In Modigliani and Miller (1963), M&M relaxed their prior assumption of zero taxes, and this changed their 1958 conclusion. In M&M (1963), the value of the firm is shown to change with the firm's capital structure because of the tax shield from interest on debt. In an M&M (1963) “world,” the higher the leverage, the more valuable the firm.

In M&M (1958) and M&M (1963) (and in many textbooks), a firm's capital structure is only discussed in terms of the percentage debt and the percentage equity. Issues such as the maturity ladder of the firm's liabilities (i.e., whether the firm financed itself with long- or short-term debt), in which markets the debt was issued (i.e., U.S. dollar versus euro), and whether the interest rate was fixed or floating are never considered. We will raise these issues in this chapter.

M&M also established the initial theory on corporate dividend policy. Miller and Modigliani (1961)2 showed that firm value is not affected by whether a firm pays dividends or by the level of dividends. This M&M paper was again controversial among finance professionals and academics because the great preponderance of large firms at the time paid regular and stable dividends. Because of this paper, prior to about 1985, textbooks taught that managers need not worry about whether or how much dividends firms paid. Moreover, textbooks did not discuss the financing implications of dividend policy.

Finally, before 1985 the nature and type of securities issued (e.g., straight preferred, convertible preferred, adjustable rate preferred) were also not discussed by academics.

Today we teach that the market views dividends and equity issues as signals and that a firm's stock price is affected by the firm's financial policies. This shift away from a “pure” M&M world was the result of research showing that financial policies affect firm value. Financial policies were discussed extensively in the Marriott chapters. In addition, as we saw in the Massey Ferguson case, the true cost of bankruptcy is composed not merely of cost of the process itself (i.e., the legal and professional costs) but also includes the loss of competitive advantage.3 The major cost of financial distress is the harm inflicted by competitors to a firm's product market strategy. Additionally, as a firm's stock price drops, the firm becomes a target for acquisition.

In other words, what we have learned since M&M is that financial policies affect firm value. This has many implications for what a CFO should do. Let's consider an example that is not uncommon. Assume a firm has no real investment opportunities because it is in a slow-growth, stagnant industry. As such, the firm's stock price is relatively low. Also assume the firm has excess cash or other liquid assets from its profitable past. This makes the firm a potential takeover target. To avoid being taken over, the firm's management must raise the firm's stock price. Before 1985, finance professors would have had no recommendations for how to avoid a takeover because financial policies were thought not to matter. Today, most professors and any investment bank or financial consulting firm would advise a share buyback or an increase in the dividend payout. Both of these should increase the firm's stock price. This is standard operating procedure today but wasn't before 1985.4

Our discussion of financial policies below is not just based on theory. There are also numerous empirical studies supporting it. Our goal for this discussion is to derive a firm's static equilibrium as well as the dynamic process of how the firm gets there. In addition, we will attempt to tie together a firm's static goals, its financial policies, and the concepts of signaling, sustainable growth, financial needs, and so forth.

Profitable firms have high, stable cash flows. This means they can sustain higher levels of debt (there is less risk to borrowing when future cash flows are more likely) and thereby obtain the benefits of tax shields from interest payments. By contrast, unprofitable firms have low or unstable cash flows and thus a greater level of risk. These firms should lower their risk elsewhere by lowering their debt levels. Yet studies often show firms do the exact opposite: unprofitable firms tend to have more debt, and profitable firms tend to have less debt. This occurs because profitable firms often take their excess cash and pay down their debt, while unprofitable firms fund their cash flow deficits with additional debt.

Let's now turn to the real-life example of AT&T before and after it was forced to divest its local operating companies.

OLD (PRE-1984) AT&T

We begin by asking: What were the financial policies of the old AT&T? To answer this question properly, we first need to look at AT&T's financial information. This information, presented in Tables 9.1–9.2, helps answer the following questions: What is AT&T's apparent debt policy? What is AT&T's dividend policy? What bond rating is AT&T trying to maintain?

| Year ($ millions) | 1979 | 1980 | 1981 | 1982 | 1983 |

| Total revenue | 45,408 | 50,864 | 58,214 | 65,093 | 69,403 |

| Operating expenses | 33,807 | 38,234 | 43,776 | 49,905 | 56,423 |

| Operating profit | 11,601 | 12,630 | 14,438 | 15,188 | 12,980 |

| Interest expense | 3,084 | 3,768 | 4,363 | 3,930 | 4,307 |

| Other | 776 | 892 | 1,015 | 951 | (5,053) |

| Profit before income tax | 9,293 | 9,754 | 11,090 | 12,209 | 3,620 |

| Income tax | 3,619 | 3,696 | 4,202 | 4,930 | 3,371 |

| Net income | 5,674 | 6,058 | 6,888 | 7,279 | 249 |

| Earnings per share | $ 8.04 | $ 8.17 | $ 8.58 | $ 8.40 | $ 0.13 |

| Dividends per common share | $ 5.00 | $ 5.00 | $ 5.40 | $ 5.40 | $ 5.85 |

| Tax rate (income tax/PBT) | 39% | 38% | 38% | 40% | 93% |

| Dividend payout ratio | 62% | 61% | 63% | 64% | 4,500% |

| Year ($ millions) | 1979 | 1980 | 1981 | 1982 | 1983 |

| Cash and equivalents | 863 | 1,007 | 1,263 | 2,454 | 4,775 |

| Receivables | 5,832 | 6,783 | 7,831 | 8,580 | 9,731 |

| Supplies and prepaid expenses | 1,085 | 1,224 | 1,398 | 1,425 | 2,111 |

| Current assets | 7,780 | 9,014 | 10,492 | 12,459 | 16,617 |

| Plant and equipment | 99,858 | 110,028 | 119,984 | 128,063 | 123,754 |

| Investments and other | 6,131 | 6,511 | 7,274 | 7,664 | 9,159 |

| Total assets | 113,769 | 125,553 | 137,750 | 148,186 | 149,530 |

| Short-term debt | 4,106 | 4,342 | 4,019 | 3,045 | 2,308 |

| Accounts payable | 3,256 | 4,735 | 3,792 | 4,964 | 8,396 |

| Other | 5,235 | 5,064 | 7,260 | 5,951 | 5,165 |

| Current liabilities | 12,597 | 14,141 | 15,071 | 13,960 | 15,869 |

| Long-term debt | 37,495 | 41,255 | 43,877 | 44,105 | 44,810 |

| Deferred credits | 15,605 | 17,929 | 20,900 | 25,821 | 26,055 |

| Total liabilities | 65,697 | 73,325 | 79,848 | 83,886 | 86,734 |

| Minority interest | 1,563 | 947 | 969 | 536 | 511 |

| Contributed capital | 24,652 | 27,244 | 30,412 | 34,875 | 38,778 |

| Reinvested earnings | 21,857 | 24,037 | 26,521 | 28,889 | 23,507 |

| Owners' equity | 46,509 | 51,281 | 56,933 | 63,764 | 62,285 |

| Total liabilities and owners' equity | 113,769 | 125,553 | 137,750 | 148,186 | 149,530 |

| Debt ratio (debt/debt + equity) | 47% | 47% | 46% | 43% | 43% |

| Interest coverage (EBIT/interest) | 3.76 | 3.35 | 3.31 | 3.86 | 3.01 |

| Bond rating | AAA | AAA | AAA | AAA | AAA |

The last few lines of Table 9.2 show that the old AT&T answered these questions consistently over time. The firm maintained a debt ratio of roughly 46% for the period 1979–1983, with an interest coverage of around 3.5 times. Table 9.1 shows its dividend payout averaged 62% (for all but 1983), which means that on average AT&T paid out 62% of earnings as dividends.7 AT&T's financial situation allowed the firm to maintain an AAA bond rating for that entire period as well. (All the ratios shown below are also fairly consistent over the prior history of AT&T.)

Now, these ratios are related to each other, as are the firm's financial policies. Interest coverage is a function of the percentage of debt the firm has, and the bond rating is a function of both the percentage of debt the firm has and its interest coverage. The lower a firm's percentage of debt, the higher the interest coverage (because there is less interest to cover) and generally the higher the rating a firm will receive. In addition, dividend policy impacts the firm's retained earnings and thus its total equity.

Calculating the Debt Ratio

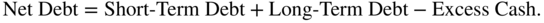

AT&T's debt ratios in Table 9.2 are calculated using the book values of debt and equity. They are not adjusted for excess cash. They should be.

What is excess cash? To a finance person, excess cash is cash that is not necessary for the operations of the business. It is equivalent to negative debt because it is not necessary for the firm to have and could be used to pay off debt. For example, if a firm issues $2 billion in debt but has no need for the funds, the firm still carries the funds on its Balance Sheet as cash and cash equivalents. The $2 billion in cash is not necessary for the operations of the business and is thus excess cash. Despite having debt of $2 billion, the firm also has excess cash of $2 billion and thus is not actually leveraged (because it could take the $2 billion of excess cash and pay off the $2 billion of debt at any time). Note that it is not necessary that the excess cash be the result of a debt issue: any firm with $2 billion in debt and $2 billion in excess cash has very different leverage from a firm with $2 billion in debt and no excess cash.

This is why, as a finance professional, you should consider excess cash as negative debt (unfortunately, not all do). Note that this sounds simple and might not be particularly memorable. However, excess cash is an important concept that significantly impacts a firm's capital structure and ultimately how we measure a firm's risk (i.e., its beta).

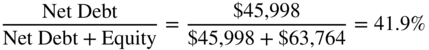

A certain amount of cash is necessary for any business to run its operations. As a simple example, a supermarket would need cash on hand for store registers. From Table 9.2, AT&T ends 1982 with almost $2.5 billion in cash and cash equivalents. The question is: How much of the cash and cash equivalents is necessary for operations, and how much is excess cash? If we calculate AT&T's percentage of cash to sales over time, we find it varies from a low of 1.9% in 1979 and 1980 to a high of 3.7% in 1982. Assuming that necessary cash is 2.0% of sales means that of AT&T's $2,454 million in cash and cash equivalents in 1982, only $1,302 million (2.0% * sales of $65,093 million) is required for operations, and the balance of $1,152 million (cash of $2,454 million less the required amount of $1,302 million) is excess cash.

So let us now calculate AT&T's debt ratio for 1982 with and without excess cash.

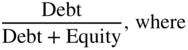

One way to calculate the debt ratio is as follows:

For AT&T in 1982:

Thus:

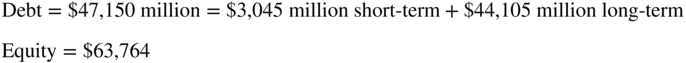

However, the correct calculation is actually:

For AT&T in 1982:

| Debt (as above) = | $47,150 |

| Total cash and equivalents = | $2,454 |

| Required cash (2.0% sales) = | $ 1,302 |

| Excess cash | $ 1,152 |

| Net debt = debt – excess cash = | $45,998 |

| Equity (as above) = | $63,764 |

In this example, the difference in the debt ratio when excess cash is taken into account and when it is not is relatively small. This is because excess cash is only 2.4% of total debt  . However, in cases where excess cash is a larger percentage of total debt, the difference can be important. All debt ratio calculations in this chapter use net debt (and assume the required cash level is 2.0% of sales).

. However, in cases where excess cash is a larger percentage of total debt, the difference can be important. All debt ratio calculations in this chapter use net debt (and assume the required cash level is 2.0% of sales).

To summarize briefly, excess cash is an important concept in finance and can make the “true” leverage ratio and risk level very different from that measured without removing excess cash.

Debt Policy of the Old AT&T

Why did AT&T choose these debt policies? Let's begin our discussion by talking about some of the aspects of debt policy. Perhaps the most important aspect of debt policy is deciding what percentage of the capital structure will be debt and what percentage will be equity. The percentage of debt will impact interest coverage, which in turn affects a firm's debt rating. Once the firm decides on the target percentage of debt, then it must decide on the type of debt. The choices include long-term versus short-term debt, fixed-rate versus floating-rate debt, secured versus unsecured, and public versus private debt. The firm must also decide where to issue the debt and in what currency.

The first issue in debt policy—the percentage of debt versus equity—as addressed by M&M was discussed above and in Chapters 5, 6, and 7, so we will not repeat it here. We should note, however, that AT&T had high, stable cash flows throughout its history. This means its risk when issuing debt was lower, and it should have had a high debt ratio to take advantage of the tax shields. That is, AT&T operations combined with a high debt percentage are consistent with the implications of M&M (1963).

The secondary issues—of long-term versus short-term, fixed-rate versus floating- rate, secured versus unsecured, public versus private, market of issue and currency of issue—are not actively addressed in the finance literature. What follows is a discussion of these secondary issues from a practitioner point of view, informed by academic finance.

As noted in Chapter 7 on Marriott, what a firm should do is match the maturity of the product market and financing strategies. In that case, Gary Wilson wanted to issue long-term, fixed-rate debt because of his belief that inflation and interest rates would rise. If a CFO has the same expectations as the market, it makes little difference if the firm goes short term or long term. The yield curve prices in the market's expectations of the future. If the CFO believes interest rates will rise (fall) in the future, while the market believes they will fall (rise), this means he will want to borrow long term (short term) at fixed (floating) rates.

In the case of AT&T, there is no evidence that the firm takes a position different from the market on future interest rates. However, its long-term product strategy, as discussed above, is stable and long-term financing matches it well. AT&T, given its huge financing needs, does not need the additional risk of borrowing short term and thereby coming to the market even more frequently and in greater size.

The decision of whether to issue secured or unsecured debt revolves around flexibility versus cost. Typically, again as discussed in Chapter 7 on Marriott, secured debt will be cheaper than unsecured debt because the market will accept the lower rate with better collateral. However, with secured debt the assets that secured the debt cannot be sold unless the debt is retired simultaneously. AT&T, as a monopoly, has no plans to sell the assets and therefore should issue secured debt to obtain a lower rate.

Corporate debt can either be public or private. Public debt involves the purchase of the debt by institutions and individuals. Private debt can either refer to bank debt or private placement debt. Bank debt is simply money borrowed from banks. Private placement involves selling the debt directly to an institutional investor, such as an insurance company, instead of offering the debt to the public.

There are institutional differences between the markets for public, bank, and other private placement debt. Public placement of debt and debt from institutional investors is more likely to be fixed rate with a longer term (often up to 30 years). As mentioned in Chapter 7, bank debt is almost exclusively floating rate and usually short or medium term (up to five years). The major distinctions between public and private placement of debt with institutional investors are that the public debt, in addition to being more widely held, may have more favorable terms to the corporation (coupon rates, call provisions, etc.) than private debt. In situations of financial distress, however, it is easier to negotiate with a single debt-holder (as is the case with private debt) than it is to negotiate with many debt holders (as it is with public debt).

Again, as noted in Chapter 7 on Marriott, the two major public debt markets in the world are the U.S. dollar and the euro markets.8 While there are others, particularly for government debt, almost all corporate debt is issued in one of these two markets. The reason for choosing one rather than the other is which market has the lowest cost given the other criteria that the firm has chosen (i.e., long versus short, fixed versus floating, secured versus unsecured, and public versus private).

AT&T's answers to the type of debt and the market to issue in was to issue long-term, fixed-rate debt9 in the U.S. public debt market. At the time, this was probably the lowest-cost source of debt financing for AT&T.

Equity Policy

With equity, a firm has similar choices as with debt. The first choice is about the amount—and as a consequence the percentage—of equity used to finance resources. This, of course, is the inverse decision to the percentage of debt. The firm also has a choice regarding the type of equity it can issue. For example, a firm can issue straight equity, otherwise known as common stock. A firm can also issue preferred stock with required dividends. There are other features of preferred stock as well, including whether the preferred stockholders have voting rights and whether missed dividends accumulate over time. Finally, a firm can issue convertibles, which is a hybrid of debt and equity. We will discuss convertibles in the next chapter. 10

Equity financing is often associated with certain “Wall Street tenets.” These include such sayings as “Don't issue equity if it will dilute EPS,” “Don't issue equity if a firm has an overhanging convertible” (which we will discuss in the next chapter on MCI), “Don't issue equity below the last issue price,” and “Don't issue equity below book value.” We will discuss these rules later.

The old AT&T answered the questions of which type of equity to issue by choosing to issue primarily common stock.11 (Why AT&T chose to do this will become more apparent after the next chapter, on MCI.)

Dividend Policy

Our next question is: What is AT&T's dividend policy? As shown in Table 9.1, AT&T pays out an average of 62% of earnings in the form of cash dividends. In doing this, AT&T keeps its cash payment level over time—that is, earnings fluctuate, but the actual dividend amount is stable and averages 62% of earnings over time.12 In addition to such regular cash dividends, some firms pay special dividends that are declared from time to time, but AT&T is not one of these firms.13

AT&T also has a dividend reinvestment plan, known on the street as a DRP (pronounced “drip”). What is a DRP? A DRP allows a stockholder to elect to receive their dividend in the form of stock instead of cash. DRPs sometimes allow shareholders to receive the stock at a discount and without paying a broker's commission. AT&T's DRP gave shareholders the stock at a 5% discount to market price. Why would a firm sell its stock at a discount to the market price? What is the firm trying to accomplish? Firms that have DRP programs are trying to get stockholders to reinvest their dividend payments back into the firm.14 DRPs are equivalent to a new issuance of shares but at a lower cost to the firm than a public offering. Despite the discounts given in DRP programs, the shares being sold are less costly to the firm because it does not incur the costs associated with public offerings, such as underwriting fees, which usually equal 5–6% of the amount issued. DRPs are a very common way for firms to issue equity: over 1,000 firms offer DRPs.15

AT&T also had employee stock purchase programs, which allowed employees to buy shares at a discount. These plans usually set a fixed time and amount of shares an employee can buy using a set price based on the preceding 30–60 days.

AT&T, as will be seen later, normally had about one-third of its cash dividends reinvested in its DRP program and employee stock purchase programs.

This discussion by no means covers all the possible financial policies a firm can have. Other policies cover choices like prefunding (i.e., obtaining financing significantly prior to a firm's investment needs, as in the case of MCI) and liquidity management.

To review, prior to 1984 the old AT&T made the following choices regarding its debt:

|

Fixed rate |

|

Long term |

|

Public issue |

|

U.S. market |

Overall, AT&T's capital structure contained 45% debt (55% equity), and its debt was rated AAA. AT&T made the following choices regarding its equity:

|

Public equity |

|

Common stock |

|

Straight |

AT&T's decision regarding its dividend policy was to provide a stable dividend with an average 60% plus payout over time. Also, AT&T had never cut its dividend. Many people considered AT&T the ultimate dividend-paying stock. Investors referred to AT&T's stock as stock for “widows and orphans” (i.e., stock for individuals who require a stable dividend).

|

Cash dividend |

|

60% plus |

|

Yes |

This brings us to our central question: Do AT&T's policies make sense?

Financial Policy Objectives

Let's backtrack. What is the main reason for a firm's financial policies? The number one reason is to protect the firm's product market strategy. Finance has many roles in a firm, but the main role of corporate finance is to protect the firm's product market strategy. This is one of the primary functions of the CFO. It is important to ensure the firm can make the necessary investments it needs. (We just said the same thing several times because it is that important.)

The second reason for a firm to have financial policies is to add value to the firm. The firm wants to maximize its tax shields, lower its cost of capital, and maximize its stock price at an acceptable risk level while at the same time maintaining the ability to achieve objective number one.

AT&T's Financial Objectives

So now let us look at AT&T in particular. In order to determine whether AT&T's financial policies before 1984 were appropriate, we first need to answer: What kind of company is AT&T? It is a regulated utility. This means the firm has virtually no choice in whether it makes infrastructure investments or not. How much AT&T's product market strategy requires it to invest is not subject to management discretion.

Prior to 1984, AT&T was a government-protected monopoly. In exchange for its monopoly status, AT&T was required to provide phone service as requested by any customer. If a new residential subdivision was built outside of town, AT&T could not say, “We are not planning to build our network there for another three years, so residents will have to do without phone service until then.” (Remember, this is before consumer cell phones existed.) AT&T did not have the option to refuse service. In addition, AT&T could not say, “You are farther out of town, so we are going to charge more for your phone lines.” AT&T was required to charge everyone the same rates for local service.

In other words, AT&T could not choose to invest only in projects with positive NPVs. The firm was forced to build. The government gave AT&T monopoly rights, and in return, AT&T accepted a government-set rate structure and agreed to put in phone service wherever people requested it. This means that AT&T was constantly making new investments and thus needed constant financing. So what's critical for AT&T regarding the capital market? AT&T had to have access to capital. Thus, on the product market side, AT&T had no choice in its investment strategy: the firm had to constantly build networks, put up lines, and build substations. AT&T was therefore constantly raising money in the capital markets. Since AT&T had to make sure it could obtain funds in good times and bad, access to the capital markets was extremely important.

As with any corporation, AT&T's gross investment in any year is funded from the firm's earnings from operations minus dividend payments plus any new debt and equity issues in that year. This means that AT&T must not only forecast its investment needs but also its earnings from operations. The firm must also maintain access to the capital markets, which means managing its financial and basic business risk. It does this while trying to minimize the cost of funding.

Having established predivestiture AT&T's product market strategy, let's now discuss which financial policies it should adopt.

Let's start with the proper capital structure (i.e., debt-to-equity ratio). We recommend that a firm determining its capital structure first answer the following three questions (which we organize as internal, external, and cross-sectional):

- Internal: Can the firm service its current debt and obtain new funding that may be required, even in bad times? This question is answered using pro forma statements and best-case/worst-case scenarios. The pro formas first determine how much new funding a firm needs. They also test how far a firm's sales and profits can fall while still allowing the firm to meet its current financing payments and to obtain additional financing for any new investments that are required. This internal review essentially provides a measure of the firm's basic business risk (BBR). To repeat, CFOs should use pro forma forecasts to perform one of their basic tasks, “Don't Run Out of Cash” (which the reader may remember is task #3 in Chapter 1).

- External: Will the market fund the firm's external financing needs? This question is all about access to the capital market. This is, in turn, partially dependent on the answers to the following questions: Will the rating agencies change the firm's debt ratings? How will the firm's bankers respond? What will the firm's analysts say? If the rating agencies downgrade the firm and/or the analysts forecast trouble, this may make it difficult or impossible for the firm to raise funds at an acceptable cost.

- Cross-sectional: How are the firm's competitors financing themselves? This is another way to think about the firm's risk. As we learned in Chapter 5 when discussing Massey Ferguson, if a firm takes on more financial risk than its competitors, it can put its product market operations at risk. In this case, there were no competitors to AT&T before 1984 because AT&T was a monopoly at that time and thus cross-sectional risk was not relevant.

So, what did AT&T do to maintain constant access to the capital market?16 Importantly, AT&T ensured access by keeping a credit rating of AAA. This financial policy may have been a little stringent, but with a rating of AAA, the firm knew it would almost certainly be able to obtain financing. There has never been a time since the Great Depression (and maybe even before then) when a firm with a AAA bond rating did not have access to the capital market.

Table 9.3 presents a simplified cash flow statement17 for the old AT&T during the period 1979–1983.18 This includes, of course, its financing needs. For example, in 1979 AT&T's new plant and equipment required capital expenditures of $16.4 billion while its dividend payments were $3.6 billion for a total funding requirement of $20.0 billion ($16.4 + $3.6). The firm's operations provided $14.8 billion of this total. This meant AT&T had external financing needs in 1978 of $5.2 billion ($20.0 – $14.8). To repeat, AT&T's operations generated $14.8 billion, but the firm had to finance new investment in plant and equipment of $16.4 billion plus its $3.6 billion dividend payment, which meant the firm had to finance the $5.2 billion difference.

TABLE 9.3 AT&T Cash Flow Statements, 1979–1983

| Year ($ millions) | 1979 | 1980 | 1981 | 1982 | 1983 |

| Net income | 5,674 | 6,058 | 6,888 | 7,279 | 249 |

| Depreciation | 6,130 | 7,040 | 7,900 | 8,734 | 9,854 |

| Change in working capital and cash | 3,034 | 2,398 | 2,746 | 2,817 | (1,278) |

| Cash from operations (A) | 14,838 | 15,496 | 17,534 | 18,830 | 8,825 |

| Capital expenditures | 16,448 | 17,590 | 18,619 | 17,204 | 7,040 |

| Dividends | 3,589 | 3,878 | 4,404 | 4,911 | 5,631 |

| Funding required (B) | 20,037 | 21,468 | 23,023 | 22,115 | 12,671 |

| Required financing (A - B) | (5,199) | (5,972) | (5,489) | (3,285) | (3,846) |

| DRP and employee stock plans | 1,704 | 2,592 | 2,168 | 3,464 | 3,503 |

| Short-term debt | 334 | 236 | (323) | (974) | (737) |

| Long-term debt | 3,161 | 3,144 | 2,644 | (205) | 680 |

| New equity issue | — | — | 1,000 | 1,000 | 400 |

| Total outside financing | 5,199 | 5,972 | 5,489 | 3,285 | 3,846 |

| DRP and employee stock plans/NI | 30% | 43% | 31% | 48% | 35% |

In 1980 AT&T required a total of $6.0 billion in new financing; in 1981 the financing required was $5.5 billion; in 1982 it was $3.3 billion; and in 1983 it was $3.8 billion. Each year from 1979 to 1983, AT&T therefore had to obtain additional financing. The average was approximately $4.8 billion a year.

Where did AT&T get this money? Table 9.3 shows that AT&T's dividend reinvestment program (its DRP) and employee stock issue programs provided the firm with $1.7 billion, $2.6 billion, $2.2 billion, $3.5 billion, and $3.5 billion in the years from 1979 to 1983 respectively. The firm issued long-term debt of $3.2 billion, $3.1 billion, and $2.6 billion in 1979–1981, repaid long-term debt of $205 million in 1982, and then issued an additional $680 of long-term debt in 1983. AT&T also issued new equity of $1 billion in 1981 and $1 billion in 1982. In total, AT&T financed an average of approximately $4.8 billion each year with debt and equity (including DRPs) over the 1979–1983 period.

Fitting Financial Policies to Corporate Financial Needs

The financial information in Tables 9.1–9.3 allows us to answer the bigger question: Did AT&T's financial policies fit the firm's needs? Or, in other words, how close did AT&T come to meeting its financing needs each year?

From Table 9.2 we can infer AT&T's financial policy targets and see how close the firm came to its targets each year. What were AT&T's debt ratios? AT&T's debt ratios (debt/(debt + equity)) were 47%, 47%, 46%, 43%, and 43% for the years 1979–1983. From this, we infer that its target debt ratio was about 45%. How good was AT&T at meeting its 45% target? Very good. What were AT&T's interest coverage ratios (EBIT/interest expense)? 3.8, 3.4, 3.3, 3.9, and 3.0. Reasonably stable and centered in the mid-3s. What was AT&T's target dividend payout ratio? It appears to be about 62%, with actual payout rates of 62%, 61%, 63%, and 64% from 1979 to 1982 (1983 is an outlier as mentioned above).

Did AT&T's policies fit its needs? Evidently, yes! If a firm hits its targets every year, it means the firm must be in balance and is probably doing things right. This demonstrates the survival principle, which states that any policy that persists for long periods of time and/or across many different firms/units is usually correct.19

To review, the old AT&T was undertaking a huge amount of financing and had an AAA rating. Why did AT&T maintain an AAA rating? Because it needed access to capital markets at all times. AT&T raised more money in the U.S. capital market than any other entity besides the U.S. government. Imagine that the old AT&T hired you as the assistant treasurer in charge of financing: your job is to raise $4.8 billion a year (or $18.4 million a day, five days a week, 52 weeks a year). You have to raise $9.2 million before lunch and $9.2 million after lunch. If you choose to go on a two-week vacation, you have to raise $184 million before traveling. Every day you walk into the office, you have to raise $18.4 million before walking out. That is a large amount of money, and you have to do that every day, all year long. That's why AT&T kept an AAA rating: to have access to the capital market.

Internally Generated Funds

Now let's discuss sustainable growth, which we covered in Chapter 5 as well. (The authors believe repetition is an important way to learn, particularly when the repetition is in different contexts. If you read this book thoroughly, you will see important concepts repeated throughout. The concept of sustainable growth is one of them.)

A key lesson in corporate finance is that financial goals have to be consistent with one another and with the product and capital markets. This is why financial policies must be consistent with a firm's sustainable growth rate.

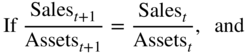

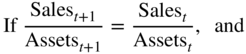

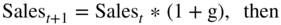

Let's explain sustainable growth. Suppose a firm has sales growing at a certain rate g (sales are going up).

If the firm's sales-to-assets ratio (sales/total assets) remains constant, then the growth in assets must equal the growth in sales (i.e., assets must grow at the same rate as sales).

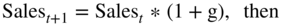

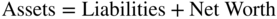

Now, since our basic Balance Sheet identity is:

This means any increase in assets has to be matched with a corresponding increase in total liabilities and net worth. In other words, liabilities plus net worth increase at the same rate as assets. Since we established that a constant sales-to-assets ratio means assets are growing at the same rate as sales, g, then liabilities plus net worth together must also grow at the same rate, g.

Stated another way: if sales grow at g and if sales/assets are constant over time, then assets grow at g. If assets grow at g and since assets = (liabilities + net worth), then (liabilities + net worth) must also grow at g.

Finally, if the ratio between liabilities and net worth remains constant (this is equivalent to the debt/equity ratio remaining constant), then both liabilities and net worth must grow at the same rate as assets (which are growing at the same rate as sales). The logic is:

Both liabilities and net worth are growing at the rate g.

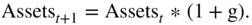

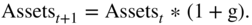

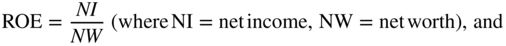

Now, net worth grows by the return on equity (ROE) minus the Dividend Payout ratio (DPR). Where:

Thus, net worth grows by:

This calculation for the growth in net worth (or equity) is sometimes called the sustainable growth rate. It provides the rate at which a firm can sustain its growth without the need for outside financing—given that the sales/assets ratio and the liabilities/net worth ratio both remain constant.

Now let's do all this backward (i.e., let's reverse the logic stream). We'll begin with the firm's sustainable growth rate, which we just defined as:

As noted above, if the debt/equity ratio stays constant over time (which means the liabilities/net worth ratio stays constant), then liabilities must grow at the same rate, g, as net worth.

Since a Balance Sheet requires that assets = (liabilities + net worth), then the rate at which assets grow must equal the growth of liabilities, which is the same as the growth in net worth.

Finally, if the sales/asset ratio stays constant, then sales will also grow at the same rate g, where g is the sustainable growth rate and g = ROE * (1 – dividend payout).

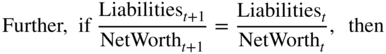

| Balance Sheet | |

| Assetst * (1 + g) | Liabilitiest * (1 + g) |

| Net Worth * (1 + g) | |

In order to grow faster than the sustainable growth rate, a firm must do one of the following:

- Increase its ROE

- Reduce the dividend payout

- Increase the debt/equity ratio (sell additional debt)

- Increase the sales/assets ratio

- Issue outside equity

Importantly, you cannot set financial goals at random. Assume a firm has an ROE of 20% and a payout ratio of 50%. How fast can sales grow if the debt/equity and sales/assets ratios are constant? Sales can only grow at 10%. If ROE is 20% and the payout ratio is 50%, then the firm's net worth (i.e., equity) is growing at 10% (20% * (1 – 50%)). If the firm's debt ratio (debt/equity) remains constant, this means the firm's debt is growing at 10%. This also means the firm's assets are growing at 10%. If a firm's assets are growing at 10% and the firm maintains its sales/asset ratio constant, then sales can only grow at 10%.

Let's give a real example from the authors' experience. Every year, the CEO of a major financial institution (we will not identify him to protect the guilty) would speak before the Society of Security Analysts and lay out his firm's target debt ratio, bond ratings, sales growth, return on assets, and so on for the coming year. Every year, the goals presented were inconsistent with one another. And every year the firm failed to meet the goals. This was not surprising since no firm can meet its goals if the goals are not consistent. A firm can't predict an ROE of 20%, a payout of 50%, a constant debt/equity ratio, a constant sales/assets ratio, and sales growth of 15%. It simply doesn't work. To be fair to the CEO, he rose in the firm on the operations side and simply never had finance as an expertise. The lesson here is that while finance is not accounting, it still all has to add up.

To summarize, if we keep these three ratios constant—debt/equity, sales/assets, and profit/sales—sustainable growth is going to dictate a firm's sales growth. ROE times one minus the dividend payout ratio is the firm's sustainable growth.20

AT&T's Sustainable Growth

Now, let's look at the sustainable growth rate for AT&T. Over the period 1979–1982, AT&T's average ROE was 13.1% (see Table 9.4). AT&T's payout ratio over the same period was 62% (see Table 9.1; note that we are using 1979–1982 and ignoring 1983). Therefore, the firm's sustainable growth rate (ROE times one minus the dividend payout ratio) was 4.98% (13.1% * (1 – 0.62)). However, AT&T's equity grew from $46.5 billion at the end of 1979 to $63.8 billion at the end of 1982, which is a compound annual rate of 11.1%. How did AT&T do this?

TABLE 9.4 AT&T Additional Selected Ratios,1979–1983

| 1979 | 1980 | 1981 | 1982 | 1983 | |

| Sales growth | n/a | 12.0% | 14.5% | 11.8% | 6.6% |

| Net income/sales | 12.5% | 11.9% | 11.8% | 11.2% | 0.4% |

| ROA (NI/TAbeginning-year) | 5.5% | 5.3% | 5.5% | 5.3% | 0.2% |

| ROE (NI/Ebeginning-year) | 13.3% | 13.0% | 13.4% | 12.8% | 0.4% |

| Sales/TAend-year | 39.9% | 40.5% | 42.3% | 43.9% | 46.4% |

Well, we know AT&T's sales/assets were fairly constant (as shown in Table 9.4, they rose from 39.9% in 1979 to 43.9% in 1982 and then to 46.4% in 1983). The debt/equity ratios were also largely constant (as shown in Table 9.2, they were 47%, 47%, 46%, 43%, and 43% from 1979 to 1983, respectively). Looking at AT&T's net worth more closely, if we start with its value of $46.5 billion at the end of 1979 and grow it by the sustainable growth rate of 4.98% for four years, we end up with a value of $53.8 billion ($46.51 * 1.04983) in 1982. This means AT&T required additional outside equity of $10.0 billion in order to reach its actual end-of-period equity of $63.8 billion. (We calculate the $10.0 billion by taking the actual net worth of $63.8 billion and subtracting $53.8 billion, which was computed by compounding at 4.98% for three years.)

So how did AT&T obtain the additional outside equity of $10.0 billion? DRPs and employee stock plans accounted for $8.2 billion of funding during the period (Table 9.3, 1980–1982), which leaves a balance of $1.8 billion ($10.0 – $8.2). AT&T raised $2.0 billion with two new equity issues of $1 billion each in 1981 and 1982 (the difference is a rounding error). Someone new to this concept might be saying at this point, “It actually works.” Well, it has to work: the only way for a firm to grow faster than its sustainable growth rate while keeping its debt ratio, dividend payout, and sales/assets ratio the same is by issuing additional equity. When we look at AT&T, we see a firm that kept its leverage and profitability ratios constant. It also kept its dividend payouts roughly the same. Therefore, AT&T could only grow faster than its sustainable growth rate (ROE times 1 minus the dividend payout) if AT&T issues outside equity, which it did. That's the way sustainable growth works.

| ($ millions) | |

| AT&T actual net worth in 1979 | 46,509 |

| Increase from sustainable growth | *1.04983 |

| AT&T net worth in 1982 with only sustainable growth | 53,809 |

| Equity issued from DRP and employee stock plans | 8,220 |

| New equity issued | 2,000 |

| AT&T calculated net worth in 1982 | 64,029 |

| AT&T actual net worth in 1982 | 63,764 |

| Rounding error | 265 |

To summarize, the old AT&T's financial policies were to maintain a AAA bond rating21 in order to have constant access to the capital market; to issue long-term, fixed-rate debt in the U.S. market; to maintain a dividend payout ratio of roughly 60% plus; and to maintain a 45% debt/equity ratio. This was done to satisfy the firm's financing needs of $4.8 billion a year (or $18.4 million a day). These four financial policies fit together and were sustainable.

NEW (POST-1984) AT&T

Let's now discuss the “new” AT&T: the firm after its major divestitures on January 1, 1984. (Note that we are starting in 1984 because the divestment officially occurred on January 1, 1984, and because 1983 was a transition year. Even though this is being written after the fact, we will consider the period after 1984 the future.) We now ask the same questions we asked about the “old” AT&T. The first is: What are the financing needs of the new AT&T? Note, if we are asking these questions at the beginning of 1984, it means we must prepare a pro forma set of financial statements. However, since this chapter is about the consistency between operating and financial policies, rather than about pro formas, we relegate the details of how the pro formas are done to Appendix 9A.

Tables 9.5, 9.6, and 9.7 present AT&T's pro forma (divested) Income Statements, Balance Sheets, and Statement of Cash Flows, respectively, for 1984–1988.

TABLE 9.5 AT&T Pro Forma Income Statements, 1984–1988 (Postdivestiture)

| Year ($ millions) | 1984 | 1985 | 1986 | 1987 | 1988 |

| Revenue (+4%) | 35,910 | 37,347 | 38,840 | 40,393 | 42,010 |

| Operating costs (81.3% sales) | 29,195 | 30,363 | 31,577 | 32,840 | 34,154 |

| Operating profit (18.7% sales) | 6,715 | 6,984 | 7,263 | 7,553 | 7,856 |

| Interest expense (debt * 12%) | 1,180 | 1,063 | 943 | 812 | 669 |

| Profit before tax | 5,535 | 5,921 | 6,320 | 6,741 | 7,187 |

| Federal income tax (40%) | 2,214 | 2,368 | 2,528 | 2,696 | 2,875 |

| Net income (2%) | 3,321 | 3,553 | 3,792 | 4,045 | 4,312 |

| Dividend (NI * 60%) | 1,993 | 2,131 | 2,275 | 2,427 | 2,587 |

| DRP (dividend * 33%) | 664 | 711 | 759 | 809 | 862 |

Note: The assumed growth rates and ratios are given in parentheses in column one. For example, revenue is assumed to grow at 4% per year. Other ratios are similar to those calculated in Table 9.1. Importantly, we assume at this point that AT&T's dividends and DRPs do not change.

TABLE 9.6 AT&T Pro Forma Balance Sheets, 1984–1988 (Postdivestiture)

| Year ($ millions) | 1984 | 1985 | 1986 | 1987 | 1988 |

| Cash and equivalents (2% sales) | 718 | 747 | 777 | 808 | 840 |

| Other current assets (31.5% sales) | 11,312 | 11,764 | 12,235 | 12,724 | 13,233 |

| Current assets | 12,030 | 12,511 | 13,012 | 13,532 | 14,073 |

| Plant and equipment (+ 4%/year) | 20,711 | 21,539 | 22,401 | 23,297 | 24,228 |

| Investments and other (constant) | 1,250 | 1,250 | 1,250 | 1,250 | 1,250 |

| Total assets | 33,991 | 35,300 | 36,663 | 38,079 | 39,551 |

| Short-term debt (constant) | 366 | 366 | 366 | 366 | 366 |

| Accounts payable and other (12% sales) | 4,309 | 4,482 | 4,661 | 4,847 | 5,041 |

| Current liabilities | 4,675 | 4,848 | 5,027 | 5,213 | 5,407 |

| Long-term debt (plug) | 8,488 | 7,493 | 6,401 | 5,204 | 3,895 |

| Other long-term liabilities (constant) | 4,098 | 4,098 | 4,098 | 4,098 | 4,098 |

| Total liabilities | 17,262 | 16,439 | 15,526 | 14,515 | 13,400 |

| Contributed capital (+ DRP) | 12,812 | 13,523 | 14,282 | 15,091 | 15,953 |

| Reinvested earnings (+ NI – divd.) | 3,916 | 5,338 | 6,855 | 8,473 | 10,198 |

| Owners' equity | 16,729 | 18,861 | 21,137 | 23,564 | 26,151 |

| Total liabilities and owners' equity | 33,991 | 35,300 | 36,663 | 38,078 | 39,551 |

| Sales/TA | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.06 |

| Debt ratio (debt/(debt + equity)) | 34.6% | 29.4% | 24.3% | 19.1% | 14.0% |

| Interest coverage (EBIT/interest) | 5.69 | 6.57 | 7.70 | 9.30 | 11.75 |

| Expected bond rating | AA | AA | AA | AA+/AAA | AA+/AAA |

TABLE 9.7 AT&T Pro Forma Cash Flow Statements, 1984–1988 (Postdivestiture)

| Year ($ millions) | 1984 | 1985 | 1986 | 1987 | 1988 |

| Net income | 3,321 | 3,553 | 3,792 | 4,045 | 4,312 |

| Depreciation (PP&Eopen/20) | 996 | 1,035 | 1,077 | 1,120 | 1,165 |

| Change in working capital and cash | (215) | (309) | (321) | (334) | (347) |

| Cash from operations (A) | 4,102 | 4,279 | 4,548 | 4,831 | 5,130 |

| Capital expenditures (∆ in PP&E) | 1,792 | 1,864 | 1,939 | 2,016 | 2,097 |

| Dividends (60% NI) | 1,993 | 2,132 | 2,275 | 2,427 | 2,587 |

| Funding required (B) | 3,785 | 3,996 | 4,214 | 4,443 | 4,684 |

| Required financing (A - B) | 317 | 283 | 334 | 388 | 446 |

| DRP and employee stock plans | 664 | 711 | 758 | 809 | 862 |

| Long-term debt (plug) | (981) | (994) | (1,092) | (1,197) | (1,308) |

| Total outside financing | (317) | (283) | (334) | (388) | (446) |

Again, Appendix 9A provides the details of the assumptions that are embedded in the pro forma statements.

As above, this is a simplified accounting Cash Flow Statement. (Note: The accounting Cash Flow Statement could be reconstructed into a Sources and Uses Statement.)

Projected Sources of Financing

So what are AT&T's projected requirements for new funds going forward? As projected in Table 9.7, AT&T's funding needs from 1984 through 1988 are roughly $4.2 billion a year. If Table 9.7 (the pro forma Cash Flow Statement) is correct, cash from operations, at an average of $4.6 billion a year, is more than sufficient to fund the estimated new plant and equipment and dividends (remember this assumed a growth in PP&E equal to the 4% sales growth).

What does this all mean? The old AT&T needed $4.8 billion a year in new funds. The new AT&T is generating enough cash to fund increases in plant and equipment and its dividends. (We are going to assume the dividends continue as a constant percentage of net income. In fact, AT&T kept them as a level amount and did not change them with changes in net income—dividend policy is explained in more detail in Chapter 11.)

Why did AT&T require so much outside financing before 1983 but not after 1983? Several things changed. First, AT&T's sales/asset ratio went from 46.4% in 1983 (sales were $69.4 billion and assets were $149.5 billion) to an estimated 105.6% (sales of $35.9 billion and assets of $34.0 billion in 1984) after the divestiture of the Baby Bells in 1983. This means that assets decreased by a greater percentage than sales. The decrease occurred because AT&T spun off the Baby Bells, which controlled home phones, an industry that was highly regulated and losing money at the time. The firm kept its most profitable business: the long-distance phone lines. Thus, assets decreased significantly because home-related networks were spun off, but sales did not decrease by as much because those networks were not very profitable to begin with.22

Best-Case, Worst-Case Scenarios

Next, we run some simulations. Normally we would do at least best-case, worst-case, and expected-case scenarios. Here, however, we will only do an expected-case and a worst-case scenario. Our expected case is the one given earlier (Tables 9.5– 9.7). There is no need to do a best-case scenario because the expected case is already so favorable.

For the worst-case scenario, let us assume AT&T has virtually no profit going forward. (We set net income close to zero by assuming operating costs of 96.5% of sales and a gross margin of 3.5%. We also grow sales at only 1% instead of 4% in our expected-case scenario. Interest costs remain at 12% of debt—which still grows with sales but now at the lower 1% rate.)23 So in our expected case, AT&T earns just over $3 billion in 1984, while in our worst case AT&T earns $24 million. Note that even if AT&T actually had negative earnings, it could still effectively avoid showing a loss because of its tax loss carryforwards.24 Again, in the expected case AT&T makes money, while in the worst-case scenario just described, AT&T makes very little.25

Note that in our worst-case scenario we assume AT&T cuts dividends to zero. However, in the real world, AT&T would probably not cut dividends. As stated above, we will discuss dividend policy in Chapter 11 (until then, you will have to trust us).

Tables 9.8, 9.9, and 9.10 present the pro forma Income Statements, Balance Sheets, and Statement of Cash Flows for AT&T from 1984 to 1988 in our worst-case scenario.

TABLE 9.8 AT&T Pro Forma Income Statements, 1984–1988 (Worst-Case Scenario)

| Year ($ millions) | 1984 | 1985 | 1986 | 1987 | 1988 |

| Total revenue | 34,874 | 35,222 | 35,574 | 35,929 | 36,290 |

| Operating expenses (96.5% sales) | 33,654 | 33,989 | 34,329 | 34,672 | 35,019 |

| Operating profit (3.5% sales) | 1,220 | 1,233 | 1,245 | 1,257 | 1,271 |

| Interest expense (12% debt) | 1,180 | 1,063 | 943 | 812 | 669 |

| Profit before income tax | 40 | 170 | 302 | 445 | 602 |

| Federal income tax (40% PBT) | 16 | 68 | 121 | 178 | 241 |

| Net income—close to 0 by assumption | 24 | 102 | 181 | 267 | 361 |

| Dividends (by assumption) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| DRP (by assumption) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

TABLE 9.9 AT&T Pro Forma Balance Sheets, 1984–1988 (Worst-Case Scenario)

| Year ($ millions) | 1984 | 1985 | 1986 | 1987 | 1988 |

| Cash and equivalents (2% sales) | 698 | 705 | 712 | 719 | 726 |

| Other current assets (31.5% sales) | 10,985 | 11,095 | 11,206 | 11,318 | 11,431 |

| Current assets | 11,683 | 11,800 | 11,918 | 12,037 | 12,157 |

| Plant and equipment | 20,113 | 20,314 | 20,517 | 20,723 | 20,930 |

| Investments and other | 1,250 | 1,250 | 1,250 | 1,250 | 1,250 |

| Total assets | 33,046 | 33,364 | 33,685 | 34,010 | 34,337 |

| Short-term debt | 366 | 366 | 366 | 366 | 366 |

| Accounts payable and other | 4,185 | 4,227 | 4,269 | 4,312 | 4,355 |

| Current liabilities | 4,551 | 4,593 | 4,635 | 4,678 | 4,721 |

| Long-term debt | 9,637 | 9,811 | 9,908 | 9,923 | 9,846 |

| Other long-term liabilities | 4,098 | 4,098 | 4,099 | 4,098 | 4,098 |

| Total liabilities | 18,286 | 18,502 | 18,642 | 18,699 | 18,665 |

| Contributed capital | 12,148 | 12,148 | 12,148 | 12,148 | 12,148 |

| Reinvested earnings | 2,612 | 2,714 | 2,895 | 3,163 | 3,524 |

| Owners' equity | 14,760 | 14,862 | 15,043 | 15,311 | 15,672 |

| Total liabilities and owners' equity | 33,046 | 33,364 | 33,685 | 34,010 | 34,337 |

| Sales/TA | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.06 |

| Debt ratio (debt/(debt + equity)) | 40.4% | 40.6% | 40.6% | 40.2% | 39.5% |

| Interest coverage (EBIT/interest) | 1.03 | 1.16 | 1.32 | 1.55 | 1.90 |

| Expected bond rating | BB | BB | BB | BB | BB |

TABLE 9.10 AT&T Pro Forma Cash Flow Statements, 1984–1988 (Worst-Case Scenario)

| Year ($ millions) | 1984 | 1985 | 1986 | 1987 | 1988 |

| Net income | 24 | 102 | 181 | 267 | 361 |

| Depreciation | 996 | 1,006 | 1,016 | 1,026 | 1,036 |

| Change in working capital | 7 | (75) | (76) | (76) | (77) |

| Cash from operations (A) | 1,027 | 1,033 | 1,121 | 1,217 | 1,320 |

| Capital expenditures | 1,195 | 1,207 | 1,219 | 1,231 | 1,243 |

| Dividends | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Funding required (B) | 1,195 | 1,207 | 1,219 | 1,231 | 1,243 |

| Required financing (A − B) | (168) | (174) | (98) | (14) | 76 |

| Long-term debt financing | 168 | 174 | 98 | 14 | (76) |

What does our worst-case scenario mean for AT&T's financing needs? With a worst-case scenario, AT&T's financing needs (the difference between cash from operations and capital expenditures) is only $377 million over the entire five-year period. This means that if AT&T has virtually no income and pays out no dividends, the annual funding requirements are a mere $75 million a year, compared to $4.8 billion a year before 1984. Thus, in the worst-case scenario, AT&T will require less funding over five years than it required prior to 1984 in a single year. Why? Because AT&T no longer requires as many assets and consequently has much lower capital expenditures—it is now operating in a different world.

To summarize the chapter up to this point, old AT&T had to finance $4.8 billion a year every year. New AT&T, under the expected-case scenario, is going to generate enough excess cash to fund the required capital expenditures internally. In Table 9.7 (our expected-case scenario), the total cash from operations is estimated at $22.9 billion over the 1984–1988 period, while the required capital expenditures are $9.7 billion plus $11.4 billion for dividends for a total of $21.1 billion. This means AT&T can pay down $1.8 billion of debt over the five-year period in the expected-case scenario.

In contrast, under the worst-case scenario, capital expenditures are $377 million more than cash from operations over the five-year period. With no income and dividends set to zero (remember, we used assumptions to set both net income and dividends at zero in the worst-case scenario), AT&T's average annual funding requirements are a mere $75 million.

As we noted at the start, your authors believe that if you can understand the impact that AT&T's change in operations had on the firm's financial ratios and thus on its sustainable growth rate, and if by extension you understand the impact that the operational change had on AT&T's financing needs, then you have come a long way towards understanding corporate finance.

Financial (Ratio) Impact of Product Market Changes

Next, let's examine the change from the old AT&T to the new AT&T by seeing how it affects the firm's ratio analysis. If you recall, we mentioned in Chapter 2 that ratio analysis is used as a diagnostic by the firm and by external analysts and banks to determine the firm's financial health.

The impact on ratios and ratings is the kind of thing an investment banker would have in their AT&T presentation book.26 To be complete, the book should include what the ratios are going to look like in expected-case, worst-case, and best-case scenarios.

As we drill into the numbers to do a ratio analysis, we will simultaneously determine a potential debt rating for the new AT&T. Remember that the old AT&T's debt was consistently AAA rated. By looking at the firm's debt ratio (i.e., D/(D+E)) and interest coverage (i.e., EBIT/I, where I is the required interest payments), we can estimate AT&T's new post-1984 debt rating. These ratios are shown in Table 9.12 for both the expected-case and worst-case scenarios for 1984 and 1988.

TABLE 9.11 AT&T Pro Forma Cash Flow Statements, 1984–1988, Expected and Worst-Case

| Year ($ millions) | Expected Case | Worst Case |

| Cash from operations | 22,890 | 5,718 |

| Capital expenditures | 9,708 | 6,095 |

| Dividends | 11,414 | 0 |

| Funding required | 21,122 | 6,095 |

| Reduction in debt over the five-year period | 1,768 | |

| Required financing over the five-year period | (377) |

TABLE 9.12 AT&T's Selected Pro Forma Ratios, Expected and Worst Cases

| Expected Case | Worst Case | |||

| 1984 | 1988 | 1984 | 1988 | |

| Debt ratio | 34.6% | 14.0% | 40.4% | 39.5% |

| Coverage ratio | 5.69 | 11.75 | 1.03 | 1.90 |

| Bond ratio | AA | AA+/AAA | BB | BB |

Let's spend some time explaining the numbers in Table 9.12. As noted previously, we would typically also include a best-case scenario, but our expected-case scenario is so favorable we excluded the best case. AT&T's expected-case scenarios for 1984 and 1988 are given in the first two columns. The debt ratio in 1984 is 34.6% and in 1988 is 14.0%. The 1984 ratio is generated as follows: debt is $8,854 million ($366 million short term plus $8,488 million long term) while equity is $16,729 million.

AT&T's interest coverage in our expected case in 1984 is 5.69 times, and in 1988 it is 11.75 times. The 1984 number is computed by dividing the $6,715 million of EBIT by estimated interest of $1,180 million. (We estimate interest by taking the prior year's total debt and multiplying it by an assumed interest rate of 12%.27 Note that if you are calculating these numbers for your own firm, you would not need estimates because you would know the actual interest payments or borrowing rates.)

Now, in 1984, in the expected case with a debt ratio of 34.6% and interest coverage of 5.69 times, AT&T's expected bond rating is probably an AA. This is primarily because the new AT&T is no longer a utility. A utility is able to have higher debt levels with the same rating. This is because utilities, if regulated, generally have stable cash flows and therefore are less risky. Since AT&T is no longer a utility, it must now be compared to nonutilities of similar size and risk profiles.

Let's now jump forward to AT&T's expected case for 1988. The expected-case pro forma shows that AT&T's expected debt ratio drops from 34.6% to 14.0% from 1984 to 1988, and the interest coverage rises to 11.75 times.

And what would AT&T's debt rating be in 1988? It would probably be AA+ or AAA in 1984, due to the improved ratios. So in our expected case, AT&T's world looks favorable.

What happens if AT&T experiences a worst-case scenario (e.g., zero profits) instead? Under the worst-case scenario, in 1984 AT&T's net debt of $10,003 million is slightly higher than in the expected case. The debt ratio is 40.4%, and the interest coverage drops to 1.03 times. (EBIT is essentially equal to the interest charge when net profit is close to zero.)

AT&T's expected bond rating, based on how the rating agencies translate coverage ratio and firm size to ratings, would probably be BB. If the rating agencies in our worst-case scenario believed the zero profits were a one-time event, then the rating for the firm might even be BBB.28

Going forward to 1988, AT&T's debt ratio would decrease slightly to 39.5%, while the interest coverage increases to 1.90.

This means that if AT&T makes almost no money for five years and continues to invest in capital expenditures at the same level as sales growth (which we set at 1% in the worst-case scenario compared to 4% in the expected-case scenario), the firm's debt level and interest coverage remain basically unchanged. AT&T would still be a giant firm with a lot of assets; a smaller firm with the same ratios might get a lower rating.

Thus, in the expected-case scenario, AT&T's rating goes from an AAA before the divestiture to an AA afterward and back up to an AA+ or AAA by 1988. In the worst-case scenario, AT&T goes from an AAA now to a BB over the same period.

If you recall, we stated earlier that a firm sets its debt ratio according to internal, external, and cross-sectional criteria. How would you categorize the above ratio analysis? It is the internal analysis. We have used the firm's pro formas, showing its expected-case and worst-case scenarios, to estimate future ratios and, by inference, future ratings. That is all we've done. It is not analytically complicated, but it is detailed.

Now, after looking at the old AT&T's performance, ratios, and financial policies as well as the new AT&T's pro formas, let's consider a new question: What should the new AT&T's financial policies be?

There are two big changes for the new AT&T. First, the firm is no longer a regulated utility. Second, the firm will invest much less in new infrastructure and will therefore have a large decrease in required funding. This decrease in investment causes the firm's sales/assets ratio to go from 0.46 to 1.06. This means AT&T's capital intensity has soared. Moreover, AT&T is no longer a monopoly. It is one firm in a competitive industry, albeit a large firm. So AT&T's BBR, its basic business risk, also just went way up.

Prior to MCI and other competitors entering the long-distance market, AT&T had 95% of the long-distance market and a monopoly on most local phone service. As of 1984, AT&T's long-distance market share was down and the local operating companies were now separate entities. In addition, prior to 1984 if you wanted a phone, it was an AT&T subsidiary that provided it. Now, consumers could purchase their phones from a number of manufacturers.

All of this also meant that AT&T had to begin marketing for the first time. AT&T rarely ran ads before the divestiture. There was no reason to run ads when the firm was a monopoly. After 1984, AT&T, in multiple ways, was in a whole different world.

The “New” AT&T's Financial Policies

So let us now discuss AT&T's new financial policies. Our first set of questions about financial policies for the new AT&T is: What debt rating should AT&T seek? Since AT&T is no longer a utility, should AT&T try to maintain its AAA rating? If AT&T decides it wants to maintain an AAA debt rating, it will have to lower debt and/or increase interest coverage because it is now an industrial firm and not a utility. As noted above, utilities can have higher debt levels because, as most of them are monopolies, they are considered more stable than industrial firms. The AAA rating used to be important for AT&T because it guaranteed access to the capital markets at all times. With lower financing needs, this may not be as important for the new AT&T. So what is the right rating for the new AT&T? We will answer this shortly.

Our second set of questions concerns AT&T's dividend policy. Should AT&T maintain its dividend payout at 60%? Or should the firm change its dividend policy? Also, if it makes changes, what should they be? If the firm lowers dividends, should it do so rapidly or gradually? If AT&T cuts its dividends, the firm sends a signal to its shareholders, who expect a dividend.

A possible third set of questions is: Should AT&T continue to issue long-term, fixed-rate debt in the U.S. market, or should AT&T now finance differently?

As we see from these three sets of questions, AT&T must now decide on whether to keep its old financial policies or adopt a new set. AT&T's new product market policies, as a firm in a competitive industry, will dictate what AT&T should do financially.

Let's review again where AT&T is at the end of 1983. AT&T has $4.8 billion in cash. The firm has a 43% debt ratio, and interest coverage is 3.01 times. The firm's debt is rated at AAA. AT&T's dividend payout is effectively 40% (it is 60%, but 20% of it comes back to the firm through DRPs and employee stock plans). Finally, AT&T's stock price is at a 17-year high of $68.50. However, the firm has a lot of uncertainty. It has just divested the Baby Bells, it is no longer a regulated monopoly, and it now has to compete in the market with MCI and anybody else that wants to enter.

So what should AT&T do? Nothing? Cut dividends? Sell stock? Buy back stock? Issue debt? If this were a classroom, your instructor would now pause and ask the class the question, elicit various answers, and debate the alternatives. So do that in your mind, and we will next tell you what actually happened and why.

What Happened and Why

On February 28, 1983, AT&T announced an equity issue for $1 billion. Are you surprised by that? The market was. On the day of the announcement, the market lowered AT&T's stock price by 3.5%, from $68 3/8 to $66. This may not seem like much, but AT&T had 896.4 million shares outstanding. This means the firm's market value fell by $2.1 billion (from $61.3 billion to $59.2 billion) that day. Essentially, AT&T announced an equity issue of $1 billion, and the market responded, “Really? You are now worth $2 billion less, a 200% dilution.”

Why such a decrease in the market capitalization (market cap)? AT&T was a company that looked like it was in pretty good shape but had an uncertain outlook. The firm had a pile of cash, a very low debt ratio, good bond ratings, and a stock price at an all-time high. Then it announced they are going to issue equity. How did the market interpret this? The firm's action seemed to signal that AT&T's management did not expect the stock price to increase in the future. Further, the equity issue may have signaled to outsiders that the firm believed it might not have enough internal cash flow in the future to meet its financial needs. This is what signaling is all about, and it is driven by asymmetric information. At a time of great uncertainty with no apparent need for money, management decided to issue equity. The market was understandably confused and concerned! As a consequence, the stock price went down.

Is this typical for other firms? Actually, it is. When firms issue equity, 31% of the amount they issue is lost, on average, in lower share prices.29 This means that if a firm announces that it will issue $100 million in new equity, its market cap (share price times the number of shares outstanding) on average goes down $31 million. However, the management has $100 million of newly injected funds from the issued equity to use.

Issuing new equity is not the only financing event that affects a firm's stock price. If a firm buys back shares in a self-tender offer or repurchase program, the stock price goes up on average. If a firm increases its dividends, the stock price goes up on average. If a firm decreases its dividends, the stock price goes down on average.30

These different events—equity issues, stock repurchases, increases in dividends, and decreases in dividends—can be thought of in a framework of equity cash flows in and equity cash flows out. If a firm decides it needs additional equity cash flows, it sells stock and/or cut its dividends. The market interprets this as a negative signal and lowers the stock price. If the firm has enough equity cash flows to buy back stock and/or raise its dividends, the market interprets this as a positive signal, and the firm's stock price usually goes up.

Let's consider this in the context of a typical firm's sources and uses of funds. For all firms on average, internally generated funds provide approximately 60% of the funds a firm needs for investment opportunities. In other words, an average of 60% of investment funding comes from sustainable growth. Debt issues constitute an average of 24% of investment funding for corporations. Working capital provides 12% of financing on average. This leaves equity issues at 4% of financing requirements.

It therefore appears that firms are reluctant to issue equity. Equity issues constitute the smallest part of investment funding. As a further example, in a study of 360 firms over a 10-year period, only 80 of the 360 firms issued equity one or more times during the 10-year period.31 This translates to about 2% of the firms per year.

Why would firms be reluctant to issue equity? The reluctance may be driven by the fact that the market usually views equity issues as negative signals because of asymmetric information. As noted, if a firm issues equity, it loses an average of 31% of the value of the equity issue.

A firm's reluctance to issue equity has several implications for the practice of corporate finance. It means:

- Sustainable growth has power. Funds not generated internally from a firm's own sustainable growth must come from debt or equity financing.

- Internal capital markets and transferring funds within the firm are important. Internal capital markets serve as an alternative to external ones.

- Financial slack32 is important because it gives the firm the ability to come to the external capital market and issue debt when new funds are required. Without financial slack, the firm may not have that alternative and might have to issue equity instead.

- The firm's debt ratio takes on additional importance (outside of its impact on financial risk) due to its impact on bond ratings and therefore on access to the debt markets, which firms need in order to avoid equity issues. Firms first raise financing internally and then, if needed, through external debt. As a consequence, firms need access to the debt market.

- Dividends tend to be sticky. Since dividends are signals, firms are reluctant to change dividends unless they can be maintained at the new higher level. We will discuss dividends in greater details in Chapter 11. For now, we will simply state that dividends don't often change.

- There are costs to false signals. We will discuss the definition of false signals and their impact in the next chapter.

- Lastly, the reluctance to issue equity also gives credence to the many Wall Street adages about equity issues, such as “Don't issue equity if you dilute your EPS,” and “Don't issue equity if you have overhanging convertibles.”33 We will also discuss these in the next chapter.

Thus, a firm's capital structure decisions are affected by financial signaling combined with asymmetric information. Together, this imposes a dynamic element to our static M&M models (discussed in Chapter 6). Suppose a firm is not at the static model's equilibrium and needs new funds. What should the firm choose as a funding source? If the firm sticks to the static model equilibrium, it should choose between debt or equity by identifying what will get the firm back to equilibrium. However, there are incentives due to signaling and asymmetric information that could encourage managers to fund investments by relying on internal earnings first. This is particularly true in the case where managers don't want to change dividends. After internal earnings, asymmetric information and signaling lead firms to choose debt as a second-place option. The third-place option is equity.

The idea that firms choose funding by prioritizing internal cash flow, debt, and then equity is described as a “pecking order.” Pecking order theory says that firms use internal funds first, go to debt funds second, and turn to equity last for the reasons listed above. Simply put, if a firm sells equity, the market believes the firm is selling equity because the stock price is currently too high.

Importantly, this dynamic of choosing funding because of the pecking order can sometimes move the firm away from its static M&M equilibrium. We will return to this issue, the M&M model in a dynamic world, in Chapter 12.

How Good Were Our Projections?

As can be seen from Tables 9.13 and 9.14, which are AT&T's actual performance, AT&T came in substantially below our expected-case but well above our worst case. In Table 9.5, we forecast AT&T's pro forma revenue in 1984 at $35.9 billion rising 4% a year to $42.0 billion in 1988. As can be seen below, AT&T's actual revenue in 1984 was $33.2 billion (7.5% below our forecast) and only rose to $35.2 at the end of 1988 (an annual increase of 1.5%). Operating expenses were much higher than our expected case forecast of 81.3% and averaged (at 96.4%) very close to our 96.5% worst-case forecast over the five-year period. Our expected case forecast $3.3 billion of net income in 1984 with a total of $19.0 billion over the 1984–1988 period. AT&T's actual net income was $1.4 billion in 1984, but due to a restructuring loss in 1988, only $3.6 billion over the 1984–1988 period. AT&T's debt levels, which average 29%, were fairly close to our projected average of 24%. Finally, the dividend payout far exceeded the 60% forecast since AT&T did not cut its cash dividend (as noted, dividend policy will be discussed in Chapter 11).

TABLE 9.13 AT&T Income Statements, 1984–1988 (Postdivestiture)

| Year ($ millions) | 1984 | 1985 | 1986 | 1987 | 1988 |

| Total revenue | 33,188 | 34,910 | 34,087 | 33,598 | 35,210 |

| Operating expenses | 30,893 | 31,923 | 33,755 | 30,122 | 38,277 |

| Operating profit | 2,295 | 2,987 | 332 | 3,476 | (3,067) |

| Interest expense | 867 | 692 | 613 | 634 | 584 |

| Other income (expense) | 524 | 252 | 402 | 334 | 269 |

| Profit before income tax | 1,952 | 2,547 | 121 | 3,176 | (3,382) |

| Income tax | 582 | 990 | (193) | 1,132 | (1,713) |

| Net income | 1,370 | 1,557 | 314 | 2,044 | (1,669) |

| Earnings per share | 1.25 | 1.37 | 0.05 | 1.88 | (1.55) |

| Dividends per shares | 1.20 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 1.20 |

| Payout | 96% | 88% | 2,400% | 64% | −77% |

TABLE 9.14 AT&T Balance Sheets, 1984–1988 (Postdivestiture)