February 2014

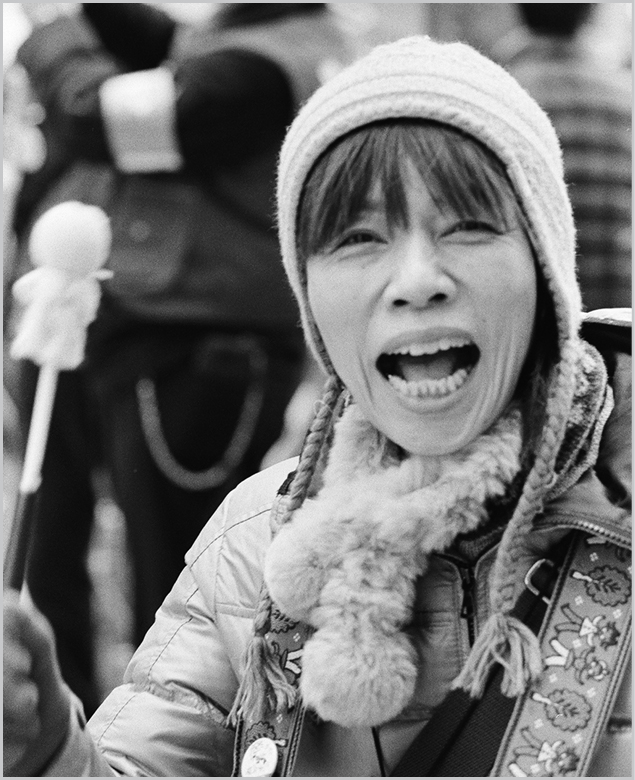

HARMFUL RUMORS

1: Safe Behind a Wall of Ice

For the past three years my dosimeter had sat silently on a narrow shelf just inside the door of a house in Tokyo, upticking its final digit every 24 hours by one or two, its increase never failing—for radiation is an attribute of time. Wherever we are, radiation finds and damages us, imperceptibly at best, ever varying within the bounds of natural fluctuation, measuring error and other such expressions of inconsequentiality. Sometimes people age suddenly, oh, yes; and every now and then come nuclear disasters. You might not call those imperceptible, but before the end of 2011, my American neighbors, who tended toward surprise at the notion that this or that forgotten crisis might not have been solved, lost sight of the accident in Fukushima. A tsunami had killed hundreds or thousands; yes, they remembered that; several also recollected the accompanying earthquake, but as for the containment breach* at Nuclear Plant No. 1, that must have been fixed, they were pretty sure—because its effluents no longer shone forth from our national news. In 2013, two out of the nine evacuated towns had formally reopened (when I saw them in 2014, they still looked abandoned). Meanwhile my dosimeter accrued its figure, one or two digits per day, more or less as it would have done in San Francisco—actually, a trifle more. And in Tokyo as in San Francisco, people went about their business, except on Friday nights, when the stretch between Kasumigaseki and Kokkai-Gijido-mae subway stations—half a dozen blocks of sidewalk, commencing at the anti-nuclear tent which had already remained on this spot for more than 900 days, and ending at the Prime Minister’s lair—became a dim and feeble carnival of pamphleteers, Fukushima refugees peddling handicrafts, etcetera, their half of sidewalk demarcated by police barrier railings, and in the street a line of officers wearing reflective white belts and double white reflective stripes resembling suspenders on the backs of their dark uniforms as they slouched at ease, some with yellow battery-powered bullhorns hanging from their necks; and at the very end, where the National Diet glowed white and strange behind other buildings, a policeman began setting up a microphone on a monopod, then deploying a small video camera in the direction of the muscular young people in their Drums Against Fascists jackets who now at six-thirty sharp began drumming and chanting: “We don’t need nuclear energy! Stop nuclear power plants! Stop them, stop them, stop them! No restart! No restart!,” at which the police assumed a stiffer stance, with their hands on their hips or at their sides, the drumming and chanting almost uncomfortably loud, commuters hurrying past us along that open half of sidewalk between police and protesters while a plainclothesman with a white armband departed the videographer’s presence, then strolled moodily behind the other officers in order to convey some private matter to the police captain; and another file of people, evidently all disgorged from a single train or subway car, walked past, staring straight ahead, one man covering his ears. Finally a fellow in a shabby sweater appeared, and murmured along with the chants as he too passed round the corner. He was the only one who appeared to sympathize; hardly any others reacted at all. The drummers were banging away as if for their very lives, swaying like dancers, staring forward like competitive athletes on the home stretch, raising clenched fists, looking blissed out and endlessly determined. Their musical, exuberant defiance slightly uplifted me. After awhile, I retraced my steps, walking the open stretch of sidewalk toward my subway station, and was astounded to see how that listless scattering of the half-seen had become a close-packed disciplined crowd. There must have been 300 and more. They chanted and raised their hand-lettered placards. It was the last night of February 2014. Perhaps in another three years’ worth of Fridays they would still be congregating here to express their dissent,* which after what had happened at Plant No. 1 must be considered pure sanity itself; all the same, they were hurried past, overlooked, and left to chant in darkness while the dosimeter accrued another digit. Another uptick, another grey hair—so what? With radiation as with time, moment by moment there may indeed be nothing to worry about.

I was happy to see that dosimeter again. By the time I returned to Japan, the interpreter had recalibrated it from millirems to millisieverts,* the latter being her country’s more customary unit of poisonousness, so that the number of interest was now preceded (so long as the radiation remained subacute) by a decimal point and zeroes. Why not? The thing was hers now; I had given it to her, because she had to live here and I didn’t. It was the best I could do for her. I still deplored its inability to detect beta waves, given that by July 2013, and very likely sooner, Tepco had found high levels of strontium and other radioactive substances that are emitting beta rays in groundwater from a well at the port of Plant No. 1.* (The concentration of these poisons was a hundred times greater than the legal maximum. And by the way, the well was only six meters away from the ocean, but why be a pessimist? The ocean can swallow anything.) Fortunately, the dosimeter could stay occupied in measuring such gamma ray emitters as cesium-134 and cesium-137, the accident’s commonest soil pollutants, which in that same happy month were both about 90 times the levels found Friday.

For the rest of that year the news kept getting better and better. JDC Corp. discharged 340 tons of radioactive water into the Iizaki River . . . during government sponsored decontamination work. Well, we all make mistakes. You see, the company had not been aware that water from the river would be used for agricultural purposes, the sources added. Ten days later, Tepco now admits radioactive water entering the sea at Fukushima No. 1 . . . fueling fears that marine life is being poisoned. Come to think of it, the dangerous hydrogen isotope called tritium* had already been detected in the ocean back in June, at twice the permitted levels and climbing. Tepco would fix that, too, no doubt.

In August, the Nuclear Regulation Authority, which thus far had treated the leaking as a Level One, in other words an “anomaly,” now prepared to recategorize it as a Level Three, “a serious accident.” Soon The Japan Times was calling the situation “alarming” and speaking of trillions of becquerels of radioactive matter, which is to say about 100 times more than what Tepco has been allowing to enter the sea each year before the crisis. Tepco now estimated that 20 to 40 trillion becquerels of tritium may have flowed into the Pacific Ocean since May 2011. Fortunately, the size of the release is roughly in line with the allowed range of 22 trillion becquerels a year, so why worry?

To prevent No. 1 from exploding again, and maybe melting down, Tepco thought only to cool it with water and more water, which then went into holding tanks, which, like all human aspirations, eventually leaked. As one anti-nuclear killjoy remarked, Of course, a reactor running out of control will not be put back in order just by dumping sea water over it . . . What [this] achieved was to destroy all the reactors, and to flush . . . the radioactive substances which were inside the reactors out . . . This is the worst case.—No doubt Tepco meant well, and I for one believe that the worst case could have been even worse.

By September, South Korea had banned the importation of fish from eight Japanese prefectures. And in February 2014, when I set out for Japan, the cesium concentration in one sampling well was more than twice as high as it had been the previous July. A day after this report was issued, the cesium figure had to be more than doubled yet again. As for strontium levels, Tepco confessed that it had somehow underreported those; they were five and a half times worse than previously stated.

Three hundred tons of radioactive water now entered the ocean every day. Cesium concentrations on the surface appeared to be greatest (41.5 becquerels per kilogram) from latitudes 36 to 39 inclusive, where the Kuroshio and the Oyashio currents kissed, while the most cesium-tainted planktons were found at latitude 25. There was a scientific explanation, which the newspaper headlined as follows: Cesium levels in water, plankton baffle scientists.

In short, the marine environment was being poisoned to an unknown and almost certainly underreported extent. As for the land, it may suffice to tally the number of nuclear refugees: 150,000.

(Did you ever wonder why they couldn’t just shut down their problem? I quote a Ph.D.: The products of the fission reaction continue to generate thermal energy as a result of radioactive decay. There is no way to stop this process.—By the way, he assured us: The safety of [pressurized water reactors] is comparable to that of [boiling water reactors]. Both have excellent safety records. As for a loss-of-coolant accident, which is what had happened at Plant No. 1, the prospect that several independent systems would simultaneously fail is highly unlikely.)

Another hilarious little anecdote: Nearly 2,000 of the poor souls who toiled for Tepco in the hideous environs of No. 1 had somehow taken a dose of more than 100 millisieverts. (Bear in mind that a maximum of one millisievert per year for ordinary citizens is the general standard determined by the International Commission on Radiological Protection. A hundred millis per year increases one’s fatal cancer risk by 0.5%. A hundred millis in a week was the emergency exposure limit for nuclear workers in Japan.)* But the tale had a happy ending: The workers will be allowed to undergo annual ultrasonic thyroid examinations free of charge.

The total cost of the disaster now approached 100 billion yen.

As the Japanese government used to often advise us, there was “no immediate danger.”* And important plans were being drawn up to save the world. Tepco plans to isolate the area by injecting liquid glass into the soil and building waterproof walls . . . by early October. I never heard more about that. The next step would be to build an electric-powered wall of ice around Plant No. 1, so that no more groundwater could flow in and get contaminated; this magic defense would only cost 30 or 40 billion yen, and hopefully no other earthquake or tsunami would strike that place until the radioactivity had subsided.

How long might that be?

As you are probably aware, the half-life of a radioactive element is the time required for half of its atoms to decay into something else. An area polluted by radiation will thus remain dangerous for not one but several half-lives, until the poison has mellowed into something approximating the unpoisoned state. One Japanese official* proposed to me that when radioactivity has fallen to a thousandth of its initial strength, it may be considered a safe equivalent to normal background radiation.

Dr. Edwin Lyman of the Union of Concerned Scientists sounded less than thrilled with any such standard, saying: “Is this adequate for purpose of rehabitation? One of the issues is, if you’re talking about returning land to unrestricted use, do you clean it all the way to background level or not? If not, you’re increasing people’s risk. So it’s a value judgment. I would say offhand that it’s not reasonable to have a different standard.” In short, reduction to one one-thousandth remained unacceptable to him. But since I liked the Japanese official, who gave me many multicolored printouts, let’s call a thousandth good enough.

Very well then. Take 1,000 and divide it in half. Now you are at 500. Divide this in half again, and repeat the procedure until you arrive near 1. You will find that 10 such halvings are required to reach a quotient of about 1.17. So 10 half-lives must pass to reduce a thousand radioactive atoms to one.

The half-life of tritium is 12 and a half years. Therefore, 10 half-lives will take 125 years. If the reactor sites somehow stopped polluting the ocean on the day I wrote this, it would be well over a century before any tritium absorbed in, say, a clamshell had become harmless.

Tritium is, unfortunately, one of the shorter-lived poisons in question.*

In point of fact the radiation at Plant No. 1 had only to decay to a level at which robots and protective-suited humans could handle the fuel rods, which would be conveyed to some storage dump. One former Tepco worker* opined that the ice wall might need to operate for merely 10 or 20 years. Mr. Yamasaki Hisataka, a roundfaced, delicate, slightly corpulent man with bangs, was one of the original members of an NGO called No Nukes Plaza, which dated from 1987, the year after Chernobyl. On my arrival in Tokyo I asked him: “At this point is the Fukushima situation the same, better or worse?”

“The same. I wouldn’t say it’s worse.”

I said nothing. Looking at me, he then said, “The radiation travelled through the Pacific. As a result, it has reached the American west coast. There’s no direct danger yet, but in the future who knows what might happen?”

“What do you think should be done?”

“Not to allow them to discharge anymore. Unless we stop it now, it’s going to get worse and worse.”

“Do you think this ice wall is practical?”

He laughed. “No. Concrete or some other permanent barrier would be better.”

Did I mention that Japan’s reactor-studded islands were entering one of their cyclical periods of earthquake-proneness? One doomsayer wrote: There is simply no doubt that the Great Tokai Earthquake will come in the near future, and the nuclear disaster which that might cause at the Hamaoka Nuclear Plant could ensure that the very center of Japanese society would be annihilated.

This is why Tepco’s wall of ice resembled the fairytale of Sleeping Beauty, in which it was possible to wall off time with something permeable only to the brave.

THE CONVENIENCES OF IWAKI

A Tokyo coffee shop girl told me that she had worried about fallout just after Plant No. 1 exploded, but she did not worry anymore. She must have been safe, because she thought she was.—Would she think likewise if she lived 40 kilometers from Plant No. 1?

The latter distance haunted my mind because in 2011, when the authorities had drawn that pair of rings centered at No. 1, the 40-kilometer circle demarcated the voluntary evacuation zone. The 20-kilometer circle marked the restricted or “forbidden” zone. Only one-third of the original area remained restricted; could it be that my pronouncements about 10 half-lives were too pessimistic? As the work of decontamination progressed, and wind patterns grew better known, the two circles were abolished, and replaced by specific areas of irregular shape.—Once I decided to base my explorations near the 40-kilometer mark, the most convenient place appeared to Iwaki.

According to the encyclopaedia, this was a city in southeastern Fukushima Prefecture . . . created in 1966 with the merger of . . . five cities, including the original Iwaki. The complex of cities prospered with the opening of the Joban Coalfield in 1883. Mining ceased in 1976 . . . The Onahama Port district is Iwaki’s industrial center . . . Pop: 355,812. Well, that encyclopaedia was 20 years old. Ten years ago, so I was told, Iwaki had been by area the largest urban entity in Japan. Now it was still the third largest, so there ought to be plenty of hotels.

On the map of Tohoku, Iwaki looked to be isolated (an injustice to its sprawl), and almost but not quite on the coast, hence perhaps moderately safer from tsunamis than the localities I had seen in 2011—although the tidal wave had killed more than 300 Iwakians. The cartographers rendered it in larger type than the row of villages to the north: Tomioka, where I would soon experience several radioactive idylls; Okuma, where that fall I would actually look upon Nuclear Plant No. 1; not to mention Miyaoji and Namie.

Being closer to the 50- than to the 40-kilometer circle centered at No. 1, Iwaki never got annexed into the exclusion zone, although the mayor had issued a voluntary evacuation notice for the districts of Shidamyo and Ogi in Shimo Okeuri, Kawamae. Now all that could be repressed behind a wall of ice.

Embarking on the Super Limited Hitachi Express, which was also known as the Super Hitachi 23 Limited Express, I traveled northward from the icy snow-patches on the walkways of whitish-skyed Tokyo, where many householders had their flowerpots out, and the blooms seemed none the worse. Brown ponds reflected the ricefields. There came a few patches of snow in shady alleys, then Ishioka’s recapitulation of the Japanese architectural monoculture—no sign yet of anything strange or broken as had been the case last time, but of course even in those days I had not noticed anything sinister until Koriyama. We stopped in Mita, with the dosimeter steady at 0.271 accrued millisieverts. I saw a wall of bamboo just before Katsuta, a farmer leaning on his staff just before Tokai, a man bent over a long irrigation pipe in a brown ricefield, and then the complex agro-industrial metal skeletons of Hitachi. After our next stop I got my first glimpse of the sea, which was ultramarine across a straw-colored rectangle of grass; the pines stood outspreading; no tsunami had uprooted them, and the radioactivity must be negligible. White cranes were wading in a grey-green river over which our express rushed, and a raptor wheeled low over the water, almost hovering.

Here came Nakoso, still 70 kilometers south of No. 1. Well before Izumi we drew away again from the sea. We paused at Yumoto with its eponymous spa, set within low wooded hills. And presently I arrived at Iwaki Station, three years after what is now called the Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011, and six months after the newspaper proclaimed: Openings of Iwaki beaches offer semblance of normalcy.

2: Harmful Rumors Defined and Combatted

At 3:36 in the afternoon of March 12, 2011, when its exposed fuel rods reacted with the air’s hydrogen, Reactor No. 1 had exploded. In Iwaki the radiation achieved its maximum at 4:00 in the morning of the fifteenth: 23.72 microsieverts per hour, or about 380 times Tokyo’s average background exposure. The municipal authorities of Iwaki distributed iodine tablets to residents under 40 years old or pregnant. For the others, after all, there was “no immediate danger.” Radiation levels rapidly dropped to a mild 0.2 microsieverts per hour. During my stay in Iwaki, the dosimeter almost invariably accrued its single daily microsievert, which is to say a mean 0.042 micros each hour.

Disembarking from the Super Hitachi Limited Express on that chilly afternoon, I asked the girl at the tourist information office which local restaurants she would recommend, and she replied that Iwakians had always been proud of their seafood, but due to the nuclear accident, unfortunately, fish now had to be imported.

From one of the maps she gave me, I saw that the international port was a few kilometers south along the winding Route 6. Several beaches lay east, and then Route 6 followed the shoreline north toward the reactors. I could not tell where the current exclusion zone began.

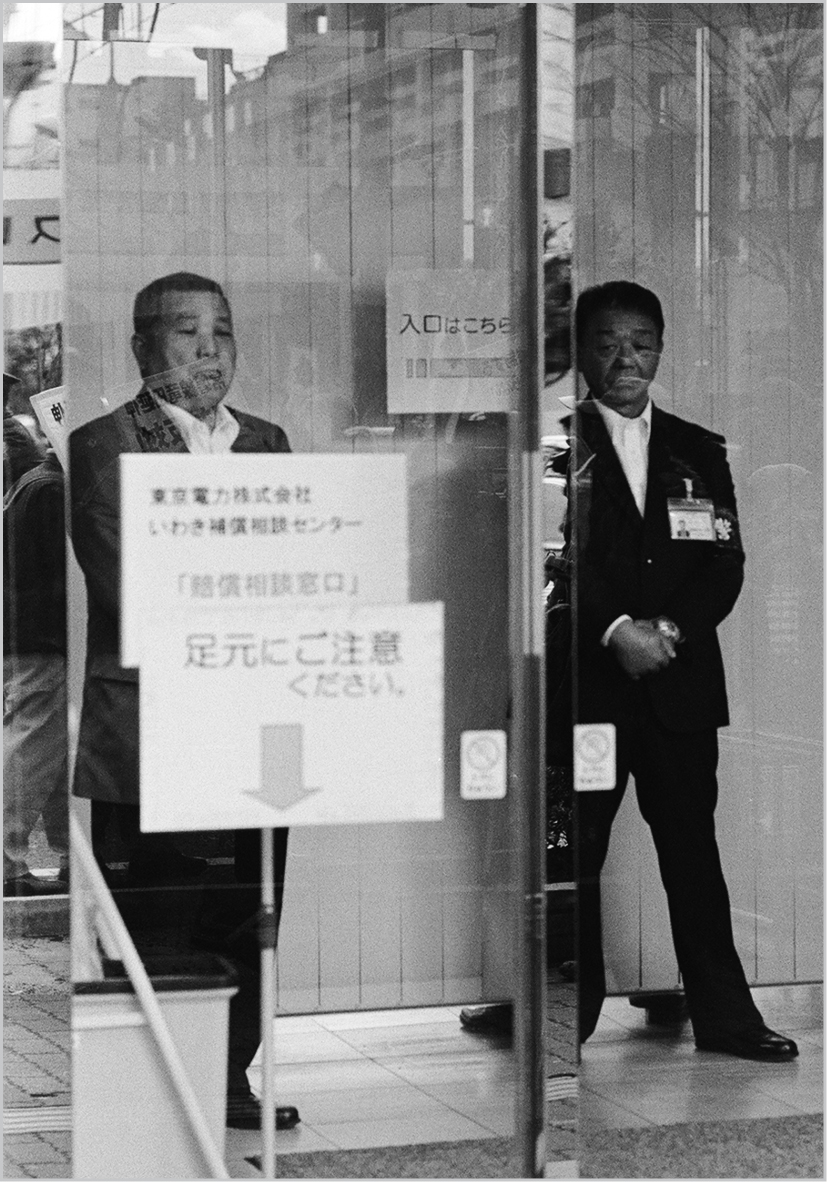

As it turned out, the hotels were nearly always full; one of them smelled of cigarette smoke and was only for decontamination workers; I asked the receptionist at another why she was so busy and she laughed, “Tepco!”

In spite of those reminders of No. 1’s nearness, Iwaki strove to present itself as safe, and maybe it was. Contrary claims were considered to be “harmful rumors.” Even after one week from the earthquake, harmful rumours on the nuclear problem kept blocking the distribution of goods to Iwaki . . . In other words, for that week certain fuel and grocery trucks refrained from making deliveries here, for fear of contamination. Moreover, harmful rumours due to the accidents at nuclear power stations degraded the status of Iwaki local products tremendously. To regain its reputation, Iwaki City has participated in more than 50 events held in Tokyo metropolitan area . . .

Thanks to such efforts, Iwaki had nearly defeated those harmful rumors. Most people’s fears, if they had not yet shed them, seemed to have been buried behind a wall of ice.

THE BLACK BAGS

Consider my first taxi driver, who was roundfaced, ingenuous and patient, smiling often, wrinkling up his cheeks. Although his hair was still black, he had entered middle age.

“How has life been here since the accident?”

“No change!” he laughed. “I’m not a person who’s very sensitive. I’m kind of dull. I just think this area is safe. Please forgive me for that.”

“What was your experience when the tsunami struck Iwaki?”

“There was no tsunami exactly here. Of course it was terrible on the seashore, but I had to be at a different place for my work, so I really couldn’t imagine.”

“And what did you think when you heard the radiation warning?”

“Even in Iwaki most people tried to flee, but I didn’t mind.* And I have an elderly person at home, so I couldn’t leave anyhow!” he laughed.

I thought he would be a perfect conductor to the exclusion zone.

“How far north can one go nowadays?”

“A little more than an hour. Then you’ll see police officers stationed in the road.”

“In your opinion, is anyone to blame for what happened, or was it just bad luck?”

“Just bad luck.”

“How do you feel about nuclear power now?”

“Ah! That’s difficult! Since we use electricity . . .”

First I asked him to drive south, to the international port of Onahama, so we rolled through the sprawl infested by France Bed, Slumberland, Lawson, Daiyu 8, Big Boy, Rabbit and ABC Mart. On the way he indicated some barrackslike temporary housing for nuclear evacuees. In general, he explained, he felt cheerful and hopeful, “because the taxi business is now thriving due to the nuclear power situation. Those who work for Tepco use taxis. If I were a fisherman I would be suffering a lot, but that’s not the case for me.”

“How do you define radiation?”

Smiling, he replied: “My image is that it causes thyroid cancer,” and he helpfully indicated his neck.

“What’s your favorite thing about Iwaki?”

“Commodity prices are low, since pay is low.

“Here the tsunami was terrible,” he now remarked. “Some ships came onto the land.” But when we arrived at Onahama, he said, “Maybe just two big ships were on the land. The vessels are all repaired. There was some souvenir shop that has not yet been repaired. And this is under construction now,” he said, pointing leftward at a fence. “It used to be . . . I can’t remember.”

“Do people here still eat local fish?”

He chopped the air with his hand. “No, because they’re not catching them anymore.”

In the international port, which I had half expected to find deserted, hordes of immaculate metal-towered ships still rode in the harbor, with a line of seabirds like buoys before them. It felt pleasant to stroll among many gulls on the great dock, with the white-laddered ships humming, diesel-perfumed. I checked the dosimeter, and a gull picked at a dead fish; all was right with the world. Far and high above us on one great ship, a dozen sailors in blue coveralls and white hard hats were unwinding a fishing net from a great spool. They were bound two hours southward, where the fishing was still considered safe. But all the smaller boats rocked empty on the water.

A patrol boat captain told me that fishing for personal consumption was not restricted, and that once a week there was “test fishing.”

“Is it the same as before? No mutant fish?”

“The same. At the market they test the fish, and if it’s all right they sell it, at a low price.”

“How are they surviving?”

“Guaranteed money from Tepco.”

He declined to let me take his photograph, and during my time in Iwaki, more people than not did the same. This fact contrasted weirdly with the vulnerable openness of all those Tohoku people back in 2011, with muck and brokenness undeniable in the tsunami zone, and the radiation danger still so new that harmful rumors were just getting hatched.

I asked him whether any unemployed fishermen might be amenable to an ocean cruise in the direction of No. 1, but this was not Mexico, where wildcatters will do any unauthorized deed for money, so he directed me up the concrete stairs to the darkened offices of the Fishermen’s Union, where a man in the hallway said: “You cannot. The Coast Guard is very strict here. It’s prohibited.”

Returning to the taxi, I asked my driver: “What do you imagine that the exclusion zone looks like?”

He thought a long time. “Just no people. You can’t enter without permission, so . . .”

“Do you suppose there are any animals there?”

“The rumor goes that pigs and wild boars have interbred.”

“How far can we drive?”

“Until Tomioka.”

“Let’s go.”

So we motored up the coast, taking Highway 15. On this lovely morning the pastel sea was very still. Now we were crossing the flats whose tsunami-destroyed homes had been deconstructed into foundations, concrete squares upgrown with grass. What I remembered from 2011 was the raw black stinking filthiness of everything that the tidal wave had reached, and surely Iwaki’s affected coastline must have been similarly death-slimed, but these pits looked merely mellow and “historic,” like archaeological sites, at least until we came to a boarded-up black house which had been wrecked by the tsunami. The driver said that the city would build a dike on the landward side of it and prohibit construction on this side.

“Do you believe in global warming?” I inquired.

“I think it’s true. Coal, electricity and all this are being used; people’s activities are continuing 24 hours a day.”

Leaving the lighthouse behind us, we reached a gleaming skeleton of half-built apartments for people who had lost their houses, and the driver now remarked: “Beside the incinerator they put some irradiated ash. There’s no other place to put it.”

“Where did the ash come from?”

“When they did decontamination in Iwaki, there were lots of radioactive debris.”

As we began to wind up into the forest, then reentered Highway 15, he asked whether I would like to see this waste, and I assented. Ahead we could see snow on Mizu Ishi Mountain, which resembled a peak less than a blue-grey ridge.

So we arrived at the Northern Iwaki Rubbish Disposal Center, whose monument is its own big smokestack. And that is how I first saw the disgusting bags of Fukushima.

“This is debris they burned in Iwaki, not fallout.” He laughed. “They don’t know where to put it.”

I got out of the taxi. Down a 45-degree slope, behind an aluminum or stainless steel wall, stood a neat close-packed crowd of dark-wrapped bags containing what he kept saying was ash from the decontamination of Iwaki. In this he was mistaken; the city did not burn radioactive matter. But in saying that they did not know where to put it he uttered a truth, or, if you like, a harmful rumor. On the metal wall was a radiation symbol. Not knowing how dangerous these bags might be, I strode slowly toward the edge of the grass where the slope began. This was close enough, I thought. The dosimeter remained at 0.272 accrued millisieverts, where it had been all day. I liked that.

Black bags at the Northern Iwaki Rubbish Disposal Center

Within a day or two, I hardly noticed those evil bags unless they happened to be many together. The closer to No. 1 one drew, the more one saw. By early 2016 there would be nine million of them.

Black bags near Naraha

MY FIRST TOMIOKA IDYLL

Flashing through Mizushina Village, which demarcated itself first by a line of snow at the border of forest and fields, and then by small fields of cabbages, we passed a white crane in a concrete-lined stream, patches of snow in the road, a lovely brown-green pond in the forest below.

We were now, I was informed, around 30 minutes south of Tomioka.

“Is Tomioka in the voluntary or mandatory evacuation zone?”

“We are not directly involved with that, so it is not my business.”

Leaving greater Iwaki at last, coming into Hirono, which had only recently been declared safe, we passed a square reservoir for the ricefields, and the snow thickened a trifle. Who would have known there was poison in this land with its many bright green pines, its wall of bright bamboo, and now its ricefields rectangularly outlined in snow?

Some workers in blue uniforms and masks were digging up someone’s yard.—“Decontamination,” explained the driver.

Other laborers were decontaminating a ditch.

Turning left onto the Sendai road, glimpsing the ocean not far away, we presently entered Naraha, just south of the Sports Park where more great neat blocks of waste from decontamination lay wrapped in greenish-black tarps down in two sunken fields.

The driver said: “Continue down this mountain and you will see Plant No. 2.”*

“Is it dangerous?”

“There is no problem from that. It’s No. 1 that exploded. I think they are trying to decide if they should abandon No. 2.”

“What do you think they should do?”

“I don’t need it!” he laughed. “Even though we do use electricity, we are not the ones who need this nuclear plant. The big cities use it.”

Down we went, and he said: “You can see No. 2 to your right,” and at first I couldn’t, on account of a certain snowy grassy hill, but then I saw the stack alone, cradled with scaffolding. That meant we were 12 kilometers south of No. 1.

“Before three-one-one,* I entered it,” he said, almost bemused. “I was surprised how strict the security was. They were concerned about terrorism.”

Pretty soon after that we came into Tomioka.

On that first occasion the place did not look so bad; I noticed only a smashed house.—For me Tomioka, whose pre-accident population must have been between ten and sixteen thousand (nobody lived there anymore),* resembled the contested Iraqi city of Kirkuk in that each time I returned I felt less safe, because I came to know more and see more. Even this time, I am proud to say, I understood enough not to follow the sign that directed me to the Tomioka Town Office.

I wrote in my notebook, a partially abandoned feeling.

It seemed quiet enough, to be sure, but an American could easily set this aside because in many of our small towns the pedestrian had become a rare sight. And there was plentiful vehicle traffic just ahead—Tepco workers, I supposed, queuing up at the police checkpoint where the exclusion zone began. Not wishing to be noticed and possibly asked to leave, I had the taxi pull over on the first side street. Leaving the driver for awhile, the interpreter and I got out. Snow lay against the Night Pub Sepia.

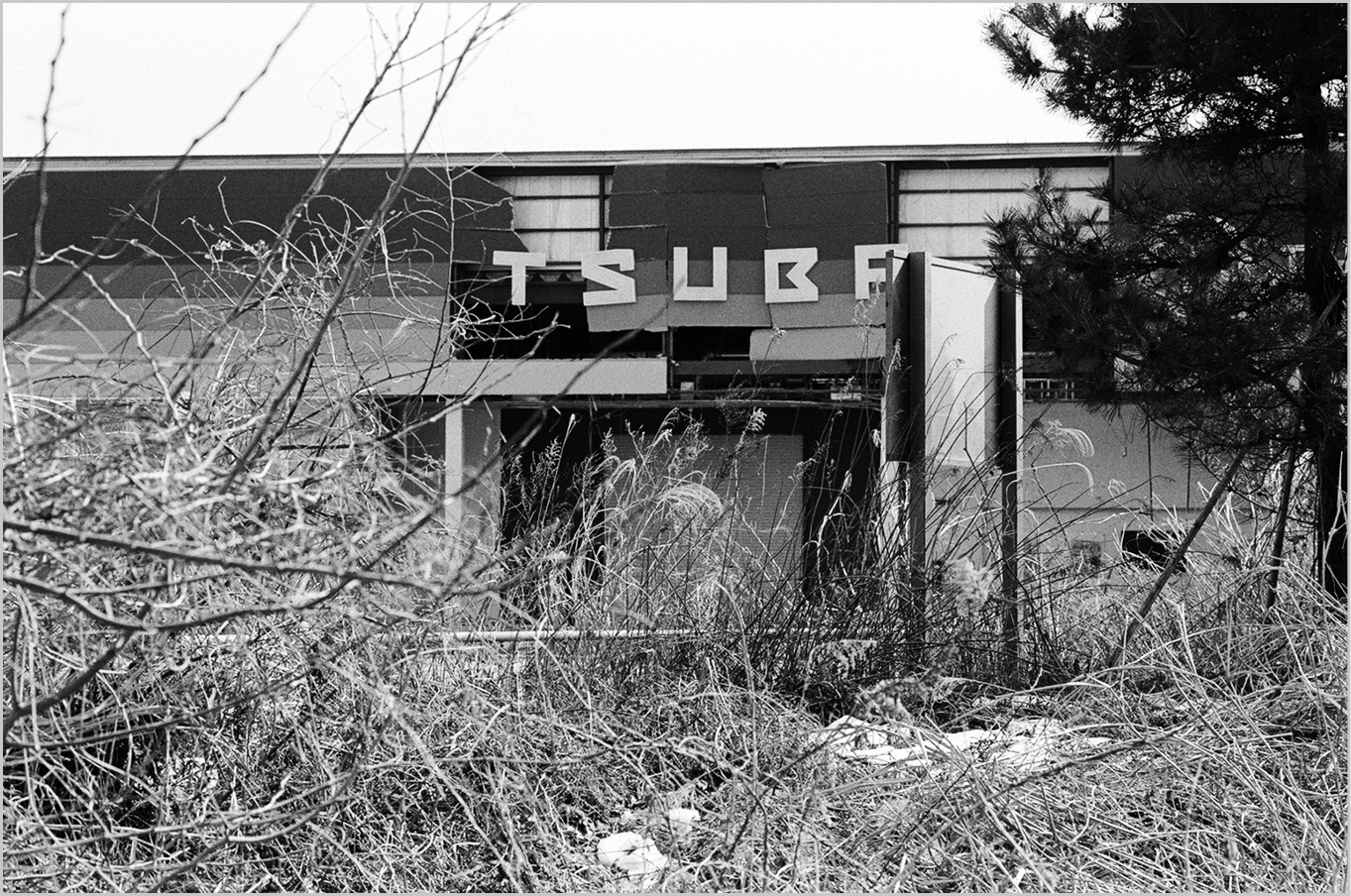

Just off this road lay a building whose reliefed facade spelled TSUBA, and between the T and the S the epidermal layer had been torn open. This place had once been a pachinko parlor. It would be my landmark on other visits.

Ruined pachinko parlor, Tomioka

There was a dead weed, tall and half-frozen, outspreading its lace-tipped finger-stalks, projecting its complex and lovely shadow upon the white wall of a silent house whose windows were all curtained. I remembered how Kawauchi had been three years earlier, with the residents freshly fled from their homes. Tomioka was not like that. Tall grasses rose up before the side of another home, the tallest one reaching halfway up the window, whose outer pane was so canted that only two corners now kept it in place. There were reflections and shadows of other weeds in the glass, behind which the blinds were drawn. In a third house, a dead weed elegantly leaned before a sliding glass door that had been papered over. In a fourth, golden weeds reached and bent before crumpled blinds.

I gazed up a power pole, and found its wires wrapped with creepers.

Grass was growing up toward the snow-patched roof tiles of another silent home whose curtains had been neatly drawn sometime between a day ago and three years ago—most likely not the former, since the front door was utterly overgrown.

For the first time I now suddenly heard that amplified recorded voice, evidently a young woman’s, but distorted and metallic, so that the interpreter and I came to refer to her as the robot girl. This time she was reminding the workers not to spread radioactivity; they should dispose of their protective gear at the screening place on their way home. It must have been lunchtime, or the end of a shift. But where were they? We walked past closed garages, a shuttered sliding door, curtained windows, then down the street to a house where an all-male crew in blue uniforms and light paper masks were decontaminating: digging with shovels, pausing, then dragging picks and rakes across gravel. I asked one of them if the radiation concerned him and he replied that he felt no worry. He refused to let me photograph him.

Now I caught first sight of the forbidden zone’s present boundary. Partly occluding a side street was a tall narrow signboard, which said, as rendered in my interpreter’s beautiful English:

TRANSPORTATION IS NOW BEING

RESTRICTED.

AHEAD OF HERE IS

A “DIFFICULT TO RETURN ZONE.”

SO ROAD CLOSED.

—NUCLEAR DISASTER FIELD MEASURE HQ.*

Tomioka was warmish and still, the patches of grubby snow beginning to sweat, and a crow cawed far away; then for a moment the only sound was the scraping of those decontamination workers’ shovels.

It was strange to look south up the rise of highway we had descended in the taxi; somehow it seemed that up there it was safe, and here the wrongness began, when really it must have been just as dangerous all the way up the hill. The weeds were motionless, and now the robot girl fell silent. As the interpreter and I walked among those forsaken houses we saw more windows covered with paper, and sometimes uncurtained windows through which we could look into furnished rooms. Every now and then, but not too often in this district, a window was broken. Behind a fence, metal was banging on metal. Perhaps it was torn siding. Was a breeze blowing over there? The banging went on and on like a telegraph.

There was an asphalt path, perhaps for cyclists, and after it crossed a deserted road, weeds began to grow out of it. I came into this vegetation, and it began to touch me.

Still I thought that Tomioka appeared only a little shabby, not really, as the interpreter opined, abandoned—weeds could have done much more in three years. A flutter of wings, and geese rose screaming from the tall grass. Startled, I watched them go, then checked the dosimeter, which had already registered another digit, so that my chest tightened. As another high stalk wrapped around my ankle on that overgrown sidewalk, I wondered what particles might adhere to it.

A silent house of broken roof tiles hunched beside another whose window was shattered. Red shards lay bright on the empty street.

To the left and the right were those vertical rectangular free-standing signs, flanked by traffic cones, with knee-high metal railings as if for bridges deployed behind them, so that scofflaws such as I must step over them to come into the forbidden zone. That is what I did, I confess, but only for a moment or two. Of course the dosimeter refrained from another immediate increase, and then we turned north, passing the taxi and walking along the highway toward the checkpoint, which might have been the most dangerous action of that day since many construction and decontamination vehicles were passing in and out, emitting dust. We had brought no masks, because three years ago I had found that drivers tended not to wear them and the interpreter experienced difficulty in speaking with a mask on; as for me, I declined to use protection when the people in my employ wouldn’t or couldn’t. So I read the dosimeter, and choked in more truck-dust, facing away from the road whenever I could. That was my way of standing up to harmful rumors. Then we arrived at the central government’s checkpoint.

Nuclear checkpoint on Highway 6

I asked the nearest police officer why some houses looked worse than others, and he said he didn’t know, because he was from Tochigi Prefecture. No doubt it was better for him not to be from there. When I began to inquire about the radiation levels here he said: “Sorry; I’m busy with my duties.”

Across the road stood two other officers, badge numbers TI 562 and 558. I asked if anyone still lived here in Tomioka and they said that almost all the people were gone. As to why some houses looked better kept than others, one policeman replied: “I have heard that some workers,” evidently meaning decontamination laborers, “are weeding.”—They each had white dosimeters in their breast pockets. I asked how much radiation they expected to accrue, and they replied that it was their first day here. Whether the government rotated them briefly in and out to keep them safe or to keep them ignorant was a question I might have spent all my money to solve, so I left it, and again that loudspeaker voice, feminine yet brassy, echoed through the hills.

As we entered the taxi and began to drive away, I pulled the dosimeter from my shirt pocket and felt a kind of pleasure, which presently became uneasiness, to see that it had already upticked by another digit. Within that single hour it had registered three times as much radiation as it had in the 24 hours from Tokyo to Iwaki. In other words, the dosage in Tomioka was potentially 72 times greater than in Tokyo.*

On the way I kept the dosimeter near my ankles, where the weeds had touched, and since it stayed at 0.275 millisieverts for the rest of the day, I (being rather ignorant in my way) decided that my bluejeans and shoes must not be overly contaminated, at least not with gamma emitters, and I had not yet been capable of measuring alpha or beta anyway. The driver drove cheerfully back toward Iwaki, past the sand-striped beaches where as he explained one could not swim due to those leaks of radioactive water. The pastel ocean-line looked lovely, and Iwaki was innocuous. It felt relaxing to be once again on the safe side of that imaginary wall of ice.

“I EAT WHAT IS IN FRONT OF ME”

If you walked east of the train station for 15 minutes and then ascended a steep little hill, you would reach the campus of Higashi Nippon International University, where I met the fresh-minted graduate Mr. Takamitsu Endo, who was smiling, lightly moustached and pale. He had majored in information technology. The interpreter characterized him as “gentle and timid.” He wished to become a social worker here in his home prefecture, “to be with my parents.”

He had been an exchange student in Ohio when the earthquake struck.

“How were you feeling when you heard about the disaster?”

“I was anxious about my parents.”

“And how are you feeling about it now?”

He hesitated, hissed between his teeth, covered his mouth with his hand and finally said: “It’s hard to tell. I think about my parents, my friends.”

“How long do you expect this area to be poisoned?”

“For a solution, well, I believe it takes time,” he replied, smiling and opening his hands. “The government is more focused on the Tokyo Olympics than on this.”

“How dangerous is it here in Iwaki?”

“I don’t know. In the beginning, people were talking about it. Nowadays there’s nothing said. It seems that no one is worried.”

“In the long run, will the situation here be better, worse or the same?”

“If another earthquake comes, it will be dangerous. But currently the prospect of another Kanto Earthquake is greater.”

“Do you worry about eating local food?”

“I don’t think twice about it.”

“And local seafood?”

“I feel a little resistance to eating seafood.”

“When you go to a sushi restaurant, do you wonder where the fish came from?”

“I eat what is in front of me.”

“Would you go swimming here?”

“Well, I haven’t swum in 10 years.”

So he had it all figured out.

In the vocational office next door, an embarrassed young clerk who because this interview had not been previously cleared with his superiors preferred to be called “a company employee” assured me in contradistinction to the first taxi driver that no one in Iwaki had run away when No. 1 exploded; he himself did not feel especially concerned, although perhaps he might now begin to consider food safety now that he had a six-month-old child—but with the child still unready for solid food, this issue could be postponed. No one was really concerned about radiation, he repeated, for after all there had been no effect. I mentioned the suffering of farmers and fishermen, and he remarked that none of them were his friends; anyhow, the restaurants of Iwaki no longer carried local produce or seafood, so everything was safe.

Come to think of it, Iwaki was safe—or at least almost as safe as Tokyo. No doctor or hospital employee in the city would agree to meet me, even though I had promised to ask only one question: Have you seen any health effects of radiation in Iwaki?—Perhaps I gave up too easily, or was losing my touch. Maybe the whole city’s bill of health was glowingly perfect, although it did disconcert me to read in the newspaper that the Fukushima Prefecture Dental Association would now with family consent examine extracted teeth of children aged five to 15, first checking for cesium or other isotopes and then, if those were present, for strontium, which, by the way, had long since set a proud culinary benchmark: When two of the Manhattan Project’s leading scientists considered poisoning the German food supply with a radioisotope, strontium appeared to offer the highest promise. Perhaps they were hoping to cause bone cancers:

RELATIVE STRONTIUM-90 CONCENTRATIONS IN PERCH LAKE* (CANADA), 1963

(absolute values not given; lake water = 1)

|

Perch flesh |

5 |

|

Bottom sediment |

200 |

|

Clam tissue |

750 |

|

Mink bone |

1,000 |

|

Perch bone |

3,000 |

|

Muskrat bone |

3,900 |

For Sr-90 concentrations at the Hanford Nuclear Reserve, see table here

Source: Odum, 1971, from Ophel, 1963.

Well, but a test is not a result. Maybe there was no cesium in any child’s teeth. As early as 2012, the Ministry of Health had announced that most sorts of vegetables that had been prone to absorb perilous levels of cesium in 2011 now registered non-detect for that element. In 2013 the news got even better: Doses of up to 15 millisieverts of cesium-134 and -137 were found in adult residents, much lower than the 100-millisievert threshold considered to increase the risk of solid tumors.—And who could blame the doctors who refused me? They were busy, I was a nobody, and so long as they declined my companionship I could hardly use their names in the process of spreading harmful rumors.

Thanks to a taxi driver who worked out with him at the local gym, I now met the farmer Mr. Hamamatsu Koichi, not to mention his industrious wife who kept carefully trimming and cleaning green onions during the interview, smiling and sometimes even sweetly laughing at my corny radiation jokes; he spoke for both of them and did not give her name. They might have been around 60. Mr. Hamamatsu wore an apron over a light down vest, and elastic wrist gaiters over the sleeves of his striped shirt. He had a round face and cropped grey hair. His eyebrows rose and curved like caterpillars. His wife wore trousers and a plaid overshirt whose feminine touch, which perhaps she had fashioned herself, was a scooped collar of the same fabric. Her lush bun of hair remained mostly black. On their urban farm, whose area was 600 tsubo,* they raised cucumbers, eggplants, broccoli, cabbages, lettuce, hakusai* for kimchi, and of course those green onions, whose fresh smell and enticing jade color excelled any counterpart I had seen in an American supermarket. I could not help but perceive their establishment as good and healthy. Perhaps it truly was, and after all there was “no immediate danger.”

“When the accident occurred,” said Mr. Hamamatsu, “the earthquake damaged the roof of this greenhouse, and we placed the plastic sheet here. On account of that damage, we could not evacuate.”

“What were you feeling when you learned about the radiation?”

“The explosion was shown on the television. I heard that the American embassy reported radiation danger all the way to 60 and 80 kilometers from Plant No. 1. Iwaki is less than 40 kilometers from there, but we didn’t have fuel for our vehicle, so the idea of escaping didn’t enter our heads.”

“And how do you feel about radiation now?”

“Because it’s invisible . . . ,” he said hesitantly, “and something happened in Russia;* there I heard people evacuated, but people here, well, it must be okay. The TV news said it went even to Shizuoka* and damaged their tea, so for sure this place must be contaminated, but we have no place to go.

Mr. Hamamatsu Koichi

“In the beginning we were not allowed to sell. We had to take our produce to the Agricultural Union and measure the radiation per kilo. Because it was too radioactive, we could not sell it, and in the second year, even when the radiation was low, we had to sell at a very low price because customers were afraid. Now the radioactivity is low enough that all the vegetables are fine. When we introduce it to the market, we must attach the certificate . . .”

In other words, that “company employee” at Higashi Nippon International University must have been misinformed: Local produce was still allowed, provided that it tested well at the Agricultural Union. And if the tests were accurate, why not? At the train station I bought a kilogram of Iwaki tomatoes and sent them off to No Nukes Plaza in Tokyo for analysis. They tested absolutely non-detect for cesium.

“Which crop shows the greatest radioactivity?” I asked Mr. Hamamatsu.

“Rape flower, they say.”

“And what do you think about the fish?”

He smiled. “Ah, I don’t think we can eat it, because the leak is going to the sea, and surely some information is being hidden. It’s not at all fine yet.”

“In 10 years will you be able to go right up to Plant No. 1 if you wish?”

Folding his hands across his apron, he smiled at this new joke, and his wife also laughed, returning to her onions. “There may be some spot where you can never return.”

A MOTIVATIONAL PASSAGE

That last was a blunt statement. Ordinarily I had trouble in getting Iwaki people to converse with me about Tomioka and other such places.

I kept asking them how safe they felt; mostly their replies came out calm and bland.

The Japanese-born Korean mother and daughter who ran a restaurant three or four blocks west of the railroad station were more openly worried, but had no idea what anyone ought to do. (I felt the same way.) The tsunami had destroyed their previous establishment, but with that customary Tohoku stoicism they assured me that it had been an old building anyhow. In their opinion, the people within the 30-kilometer zone had been compensated more than enough for the nuclear accident, while Iwaki here in the 40-kilometer zone received nothing. When I met them again in 2017, their position on the evacuees had fossilized. That pair worked hard; one night the mother was feverish, but she kept right on cooking, serving, taking orders, while the daughter rushed around trying to help her. Because only their toil preserved them, they could not but disapprove of able-bodied people who lived at public expense. Perhaps they believed that sturdy perseverance could negate the loss of home, community and possessions. And for all I know, reader, whenever you stash a few roots and tubers in your larder, you will feel comparable resentment for the less fortunate denizens of your hot dark future. We would all prefer to subscribe to Mr. Hamamatsu’s assertion: “People here, well, it must be okay.” And if we are managing, then those who cannot manage must be deficient. There are no inescapable horrors—only harmful rumors.

3: “Something Will Come In”

The next day’s driver was a very active bald old man who wore a paper mask over his mouth, as do so many Japanese when they have colds or wish to protect themselves from germs. I requested his description of the disaster and he very practically replied: “In the beginning we were busy. Now that the bus services have recovered, it’s quieter for taxis.”

“How do you feel about radiation?”

“Since it’s not close to here, it has no reality. If someone around here got cancer, I might feel something, but it’s invisible, so I don’t feel anything.”

I felt proud of him. He too had stood up against harmful rumors.

On occasion he had entered the prohibited area with the Red Cross. There had been three or four checkpoints. “Now we regularly take nurses from the Toyoko Inn,” a chain hotel, “to the No. 2 power plant. We leave at seven in the morning. They serve those who temporarily return to their houses.”

Temporary housing near Hisanohama

He drove me half an hour north of central Iwaki, back to Hisanohama* by the other ruined Fishermen’s Union, then turned westward off the highway, not very far. Asphalt and gravel channels ran straight and far between the long barrackslike units where some of Fukushima’s 150,000 nuclear refugees were housed, with patches of snow enduring between many of those silent buildings, which were besieged by clouds and wind and adorned by rectangular shadows. A tiny black cat watched from between a windowpane and a white curtain. Everything was still and raw—a different kind of still from Tomioka. Walking up and down the place, I listened in vain for the sound of a radio or television. At last I finally met one person, a former Hirono resident whom I will here call “Michiko,” because a few hours after happily flirting with me she telephoned the interpreter in a panic to ask that her name be changed; her relatives had admonished her to have nothing to do with this project. She spoke some English, and whenever she had trouble the interpreter helped her. Here then is a combination of their words: “We left after midnight of the tsunami day, March eleventh. I put the dog in the car and went to higher places. It must have been 2:30 in the morning. There were 40 or 50 of us. We arrived at about 3:00 a.m. We couldn’t sleep. The dog had to stay in the car. Everyone watched the TV. It showed a horrible picture. And soon it was morning. I took a walk with the dog and there was another explosion, and we were told to evacuate and we were so surprised: What explosion? We took Highway 36 to Iwaki. Normally this takes 30 minutes, but there were so many cars because Highway 6 was closed. We were told not to open the window, because if you open, something will come in. We were thirsty and didn’t know what was going on. I arrived at Iwaki at 10:30 in the evening, left the car and took another car to Niigata. We arrived at 4:30 in the morning without any sleep. All the roads were humped and cracked. We stayed in Niigata for awhile, then went to Tokyo, left our dog at a kennel because he wasn’t allowed at the soccer stadium where we were sleeping, and the dog was crying, so miserable! I told him, we’ll come get you soon. We stayed at the stadium for some time. Then we applied for this housing and we got it. My house is still all right, but if there’s another explosion it might not be safe. So I’m afraid to go back there.”

Such was the tale, or harmful rumor as some might say (“since it’s not close to here, it has no reality”), of this displaced woman in the plaid red vest, which is to say this high-cheekboned older woman of the pretty white teeth and wavy shoulder-length black hair and the rising laughlines at the corners of her eyes, with her hands folded across her grey skirt as she looked up at me, cocking her head as she sat on the narrow porch of her temporary home, which for a fact was better than any of the cardboard-partitioned spaces and mattress on the floor which I had seen three years ago in the hallway of Big Palette in Koriyama, where a skinny man was lying on his side, and on the next mattress a scared woman with a white mask over her mouth sat on her heels, cradling a little boy whose dark eyes stared up at the ceiling; just as the tsunami-slimed rubble of 2011 had given way to grassy hollows in the ground, so her exile had faded into something routine; there was no immediate danger. Leaving her alone behind her wall of ice, we drove back to Iwaki.

“BECAUSE IT WAS MY HOME TOWN!”

Southeast of the city center lay a smaller older hillier section of tightpacked little houses, after which the taxi ascended to the edge of the forest, then onto a plateau of fields walled on both sides by low forest ridges. In 20 minutes we had reached the district called Takaku, where another 90 households of Tomioka people lived in a barrackslike complex like Michiko’s.* They paid for electricity and utilities, not for rent. Some of them worked for Tepco.

They were shy and hasty and busy, but finally one girl, just to be rid of us, urged us to talk to a certain Mrs. Yoshida, “who knows everything” and whom we caught, poor soul, in front of her flower boxes. She was an old lady with red hair, wearing tabi socks, and as we talked with her she kept folding bluejeans in the chilly wind, having evidently taken in the rest of her laundry.

Her former home lay in the restricted area of Tomioka.* She said: “There is no decontamination and the grass is growing. The whole radiation level is high. Some civil engineers will remove large debris. It looks terrible. Even this area here is better,” gesturing around her.

Born in Kawauchi, she had lived in Tomioka for 53 years. Her son died in the earthquake. Her grandchildren moved far away.

“How was your house?”

“It was nice. Only two years before, we remodeled it. The scenery was pretty.”

“And the neighbors?”

“They’re all here.”

“Will you be able to move back someday?”

“No. We must demolish the house. The government will pay, since it’s more than half collapsed.”

Although she had been gazing sorrowfully downward, when I asked her what she had most loved about Tomioka, she began to smile, and said: “Because it was my home town!”

This made me very sad.

“IF IT IS NATURAL, IT MUST BE ALL RIGHT”

Ms. Kuwahara Akiyo, a slightly weary-looking woman with blue eyeshadow and tiny sparkly earrings, was a part time contract employee of the Tomioka Life Recovery Support Center and Iwaki Taira Interchange Salon. When I asked her to describe her home, she said: “There is a fire station. Behind the fire station there is a checkpoint. A little past the checkpoint is my house. I can return only once a month. I used to work for a day nursing service in Tomioka. I’ve been living there for 12 or 13 years.

Ms. Kuwahara Akiyo

“In Tomioka there’s not much improvement. In fact it’s even worse! There are animals: mice and rats; also those pigs interbred with wild boar. The authorities are trying to kill them, because they damage the houses, and poop inside, and bite the pillars. They don’t know humans, so they are fearless. Sometimes you can see them on the street. And there are so many rats! Whenever we go to Tomioka, we first apply to the national call center, and then there is a station where your radiation is measured. Wherever we go there, they give us some chemicals to kill the rats. Other than the rats, there is no damage to my house.

“I know somebody whose lock was broken. Then they took the car key and stole the car.

“Yesterday I went there. I did cleaning, aired out the house and picked up some stuff.”

“Do you ever feel anxiety about radiation?”

“A little bit anxious, but we have a dosimeter, and we check it. I don’t stay there so long. Yesterday I got one microsievert in two or three hours. In Okuma and Futaba they get five or six, or even 20 or 30 microsieverts in one or two hours.* A friend of mine in Futaba said the atmosphere there was like that.”

“So when you think about radiation, what do you think?”

“Invisible,” she said smiling, “and that is the cause of the anxiety. You don’t feel any pain or itching; it just comes into your body. But it is not as strong as a medical X-ray. If you want to stay, it’s of course impossible. But for an hour or two, it’s okay. In Okuma and Futaba, you’d better not stay all night, but some people, the nuclear power workers who are trying to close the plant, they do stay, and to them we feel so grateful.”

“Is it completely safe here in Iwaki?”

“Even natural radiation exists, and if it is natural, it must be all right. I think it’s safe to live in Iwaki. There are nuclear plants all over the world. You can’t flee anywhere.”

“What is your feeling about nuclear power?”

“My husband’s work is related to nuclear plants. Until the accident we were told that it was totally safe. Nuclear plants we cannot live without.” Then she said: “This was a manmade thing, but we made something so evil, so fearful, so dangerous.”

“When will Tomioka be safe again?”

“It could be a hundred years. And whether the hospitals or shopping will ever come back, I don’t know.”

What an optimist she was! She imagined that her town would be re-inhabited in only a hundred years!—And what a pessimist I was! Three years later, I revisited Tomioka and found economic demand newly allured by opportunity, in the form of a solitary convenience store.* Moreover, certain decontaminated districts would soon be cleared for resettlement. Meanwhile, back in 2014, I did my best to resist harmful rumors. In short, I inquired at City Hall.

GOALS AND MEASUREMENTS

Mr. Kida Shoichi was a decontamination specialist in the Nuclear Hazard Countermeasure Division.* He was a patient man, not young, with kind eyes. I remember him with gratitude, for although I had interrupted his day without notice, he took a half-hour to answer all my questions, showing knowledge and honesty in the process. He considered his city to be not at all badly off, because as he explained, “from Daiichi, the northwest direction* is high in radiation, so Iwaki is low.”

Activating the laptop on his desk, he showed me the 475 monitoring posts in Iwaki. Then he zoomed in.—“Here is the city office where we are right now. And here is the monitoring post. It’s 11:05 a.m., and we’re receiving 0.121 microsieverts per hour.”* Had the winds stayed consistent for 24 hours, the dosimeter should have accrued 2.9 microsieverts—three times as much as it did in Tokyo—but on that day as on almost all the others I spent in that city, only a single microsievert damaged my body. Of course I passed much of that time indoors—although, come to think of it, the dosimeter mostly lay within the interpreter’s house, in a basket just past her front door. Wishing to cross-check that device, I told Mr. Kida that by my measurement Tomioka had registered as 72 times more radioactive than Iwaki. Clicking on Tomioka, he corrected me: “No, the highest is about three microsieverts per hour, so that’s only 26.8 times more than here.—No, here’s a place that measures four. And here’s a five, so that’s 45 times higher . . .”*

Since he now looked a little sad, I refrained from asking him to continue scrolling through the remaining Tomioka readings. Besides, my would-be comparison was once again apples and oranges, since the dosimeter could not measure local radiation moment by moment.

Mr. Kida next zoomed in on a monitoring site at Futaba Town: 13.61 microsieverts per hour at present.*—The year previous to the accident, Futaba’s air dose had averaged 0.043 micros an hour. An anti-nuclear ideologue might accordingly denounce that place as 317 times more radioactive than before. But one station at one moment, compared to a townwide average, should not have caused any stir. Besides, had I opened my mouth about the matter, some harmful rumor might have come out! So why not simply reflect that if those 13.61 micros kept up until tomorrow, all over Futaba, then Futaba might be maybe 327 or possibly only 113 times more dangerous than Iwaki?* Better yet, why not assume that in due course everything would get wonderful? Thus Tepco planned for tsunamis and American politicians prepared for climate change. We humans were much the same.

“Okuma and Futaba are still prohibited,” Mr. Kida remarked, which seemed sensible enough.

“When will Plant No. 1 be safe?”

“You have to wait until natural reduction occurs.”

“Five hundred years?”

“I believe so.”

The next day he telephoned me with a correction: In only 300 years, barring further accidents, the radiation would have decayed to one-thousandth of its original strength. If I peeked out of my grave in three centuries, I might well find him a perfect prophet, given my 10 half-lives calculation in Table 1* for the two most slowly decaying isotopes, strontium-90 and cesium-137.

But I received a more pessimistic answer when I asked Ed Lyman, the Union of Concerned Scientists physicist: “If there’s no further emission from the plant, is 300 years long enough?”

“Well, there’s radioactive decay plus transfer to soil; it will go deeper and deeper and get into the water and so forth. Then there’s a weathering coefficient.

“To reduce by a factor of a thousand, it would take hundreds of years. I’d hesitate to give a blanket answer.”*

One study of cesium from decades before the Fukushima catastrophe determined that losses from soil to river sediments were 50 percent greater in the year after fallout than in subsequent years—a heartening finding, perhaps, to those whose land does not abut downstream bends of that river . . . but absent accurately local quantifications of the losses one could scarcely guess how much cesium might leach away over any given time, and therefore when the area might be safe. In the Columbia River Basin of the United States,* only 0.263% of the plutonium contamination from the Hanford reactors had eroded in 20 years.

Well, anyway I had my blanket answer from Mr. Kida: 300 years.

The basic strategy for decontamination, he had explained, was to make an area give off less than one millisievert per year. Thirty percent of the cesium reduction around Iwaki had already happened naturally, and he gave me some multicolored information sheets to prove it. In November 2011, almost every part of the area had been shaded yellow, meaning “decontamination required.” By December 2012, the yellow had melted into a crescent along north and east, with a few strange patches to the south.

When I passed on this good news to Ed Lyman, he remarked: “My impression is that the cesium-134 is decaying away but the cesium-137 levels are not being reduced that much.” (The latter isotope, as you will see here, will take nearly a century longer than the former to reach one one-thousandth strength.)

Weren’t these fine tidings just the same? Iwaki was becoming safe much more rapidly than a simple half-life model would have predicted. But my thoughts rose like those weeds at Tomioka which kept growing up through parking lots, filling in for eyelashes in the dark broken window-sockets of damaged buildings. Ed Lyman had contaminated my equanimity. I could not stop wondering what was happening to the cesium. Did it sink deeper and deeper into the earth—or stop at clay—or leach into storm drains and rivers . . . ? I had read that it sometimes got concentrated in roots. No doubt the radioactivity of the ground must vary just as the ground itself did. Presumably every square meter of Iwaki required measurement. The city’s report (the one that blasted harmful rumors) explained that topsoil in schoolyards was being removed if it measured more than 0.3 microsieverts per hour—which multiplies out to 2.63 millisieverts a year, more than twice the ICRP standard; but on the other hand, one Bangladeshi brickyard, and the window-ledge of a certain bookstore in West Virginia, showed comparable values*—and if Iwaki’s children were affected only when they played outside at recess—which might or might not be a reasonable assumption to make about a gamma emitter present in low concentrations—then they would accrue a mere 60 microsieverts per year.* Oh, those radiation arithmetic games! The removal of topsoil was completed in 101 out of 131 facilities by the end of December [2012], which resulted in the maximum of 80% of reduction in radiation levels, and 50–70% in most facilities.

A 50 to 70% improvement could not be adequate—although what if it simply had to be? On this subject, Ed Lyman told me that 50%, not 70%, was the general outcome so far as he knew, in which case the time to bring down the radiation to one one-thousandth of original strength would be shortened by only one out of 10 half-lives—for cesium-137, to 270 from 300 years. But again, why spread harmful rumors?

By Mr. Kida’s estimation, the average annual natural radioactivity in the world was already 2.4 millisieverts,* and so I suppose that a pro-nuclear ideologue could label that schoolyard topsoil unremarkable. But Japanese areas unaffected by the accident received about 1.4 millis a year. The goal for Iwaki was to wait out a few half-lives and decontaminate where necessary until the radiation reached 0.23 micros per hour, or slightly above 2 millisieverts per year.—Mr. Kida now remarked that he would be satisfied with a target of even 0.5 micros an hour. I was surprised; that would be 4.4 millis a year, which exceeded the old ICRP standard.*

“Are any decontamination measures possible for water?”

“It’s difficult. We do measure. No part of Iwaki shows a high level of radioactivity. Ten kinds of fish are prohibited; those on the sea bottom* are most radioactive. If you eat a little, it doesn’t matter. If you eat one kilo every day, it’s dangerous.”

The maximum safe value for fish was 100 becquerels per kilo; some catches measured 200 or 300. But he assured me that there had been many “no detects” in 2012 and after.

Indeed, as I write this, I have before me the very long printout he gave me that appears to list many or all of the fish testing results from March 2011 until February 2014. Iodine-131, whose half-life is short, had mostly dropped to “no detect” by June 2011. In November that contaminant reappeared, at very low levels, then vanished again by March 2012, after which its placeholder stayed reassuringly blank. (For that matter, by 2013 the iodine in Fukushima’s land environment was below the critical 50-millisievert level . . . However, . . . [the U.N. Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation] also noted cases of children who had been exposed to as much as 66 millisieverts.)*

As for the two cesium radioisotopes of concern, these had intermittently announced themselves in marine tests from the time of the accident until now, but although their initial concentrations occasionally (as in samples number 11 and 13) reached such measurements as 12,500 or 14,400 becquerels per kilo, even in that bad time right after the three reactors exploded they mostly ranged from the low hundreds to around 2,000. With the exception of sample number 43 (9,900 becquerels per kilo), they quickly stopped exceeding the low hundreds at all, and early in 2012 they reached the middle double digits—where they now remained.

I said: “We have heard of many new releases of radioactive water, so would you expect that these numbers will now increase?”

“In Iwaki, what they are catching right now is at some distance from the plant, so . . . I don’t know.”

Who could blame him for not knowing? His department was Iwaki, not Futaba or Okuma. And, after all, what might be the true purpose of this testing? Perhaps it had never been intended to inform the public how dangerous it might be to consume the fish that swam just offshore from Tomioka—only to fight harmful rumors about the seafood now for legal sale in Fukushima. But this is merely my cynical conjecture. I could have optimistically hypothesized that the tritium from Nuclear Plant No. 1 would dilute to an indetectable level as soon as it entered the ocean.

Continuing on this subject, how could anyone even decide how much radiation was safe in food? According to that Tokyo anti-nuclear activist Mr. Yamasaki, cesium fallout due to nuclear testing had once (I did not ask when or for how long)* gifted Japanese rice to the tune of 10 becquerels per kilo. In Fukushima Prefecture the current reading was twice as high. “If you measure the soil,” he said, “you can tell. If you measure the rice contamination, you can see the soil contamination.”

“What is the risk from food to the average Japanese who is uninformed and does not live in this area of contamination?”

“That is a very difficult question. The rice currently in circulation is 10 or 20 becquerels per kilo maximum. If you eat this every day and the cesium accumulates internally, 4,000 becquerels will be in the whole body after one year.”

“And in your opinion, what is the maximum safe limit in the body?”

Mr. Yamasaki laughed. “There is no safe limit. When we lived in Toyoma Prefecture as children, thanks to nuclear tests we constantly had about 400 becquerels in our bodies.”

Meanwhile, when I asked Mr. Kida whether one could live out one’s entire life in safety as a citizen of Iwaki, he nodded. “Up to Naraha the radiation level is low,” he said.*

As for Tomioka, if those two nuclear evacuees, “Michiko” and Ms. Kuwahara, were here before me right now, what “blanket answer” would I present to them? The time to one-thousandth of the 2011 contamination value, which you have just heard Ed Lyman calling inadequate, would still be three centuries. Assuming that my projected annual level for Tomioka of 26.28 millisieverts was a useful approximation,* and that decontamination was ineffective, then between four and five* half-lives (151 to 181.2 years for cesium-137) must achieve the tolerable target of one milli. If decontamination succeeded, then subtract 30 years. That was my first approximation of an answer.

“BECAUSE IT’S ENDLESS”

Remembering a mention of gamma cameras being used in Kawauchi, I asked Mr. Kida whether I could see or use one. He had nothing quite like that available in the office, but promised me an excursion with a scintillation meter; so on the following day his deputy came to collect me. He was a pleasant roundish young man named Mr. Kanari Takahiro.

“In Iwaki,” he said, “we have never felt the imminent desperate situation. In fact my parents returned home in only two weeks. I myself couldn’t flee since I am a civil servant.”

“Around here, do people tell any jokes about radiation?”

“The radiation level is not high enough to create any joke.”

All the same, he too might have been a little cynical, for he referred to nuclear countermeasures as “casual countermeasures.”

“Are you sad not to eat the local fish?”

“I don’t care. Whatever fish, anywhere it comes from . . .”

The decontamination procedure he described was this: Measure, then scrape up surface soil and cut tree branches as needed; place in a bag.

The scintillation counter (which is to say an Aloka TCS 172B gamma survey meter) cost about 100,000 yen.* He called the operation of it “not difficult.” As the technical name implied, it measured only gamma waves, like my dosimeter.

We met a “superior” and a construction boss. One was tall and the other short. They wore hard hats, work jackets with white belts and suspenders, and baggy pants tucked into calf-length rubber boots. The short one wore a mask over his mouth and the tall one didn’t. I told them they were heroes. Reducing radioactivity by a factor of two was better than nothing, assuming that they didn’t smear around the contamination too much. Anyhow they were endangering themselves.

The work was all paid for by the central government. I inquired into whether it was unionized.—No, they curtly said.

They said that by and large the decontamination workers received about 4.5 micros a day, which works out to 1.63 millis a year. (Frankly, I suspect that those numbers were underestimations.) They also said that the poor souls who were trying to ice away No. 1 were getting 40 millis a year.

Hereabouts, they told me, they took in less than 0.23 micros an hour—which is to say, 5.52 micros a day—2.02 millis a year if they never took time off. Again, I am skeptical. Their supposed quarter-of-an-hour micro was only twice the 0.121 micros that Mr. Kida had said was Iwaki’s air dose. How could they be digging, bagging and breathing radiocontaminants all day without much higher exposures? Both of the cesium isotopes were beta emitters; as for the strontium-90, scientists called that one of the best long-lived high-energy beta emitters known.* On occasion these men must surely inhale beta particles—and from a dosimetric point of view, beta was invisible.—To answer my question they first considered, then estimated their doses; they never checked their dosimeters. “The radiation level is so low here that we are not worried.”

But as a rule, I pursued, what maximum did they set themselves? It was very hard to say, they replied; perhaps there was no rule. They hardly seemed to know or care. “Maybe two years ago or even last year you might have trouble, but now in normal work you never have to worry.”

Decontamination “superior” and construction boss at a radioactive waste site near Iwaki

So maybe the Iwaki people were perfectly right to eat whatever was set before them. I myself have always loved happy news.

Rolling up Highway 245, then turning east, we arrived back in Hisanohama* near where the wrecked old Fishermen’s Union used to be. A traditional Japanese-style house was being decontaminated. It looked as if a gardening crew were on the premises, except that all the gardeners were masked. Other than that, they eschewed special defenses. They wore heavy work clothes, gloves and hats; that was all.

I had Mr. Kanari begin to test things.

In the yard, the bag of waste that the nearest worker was filling emitted 0.3 microsieverts per hour. Another bag was 0.26. The target for decontamination was 0.22.

The “superior” said: “Dead leaves are an especial concern; the plants are up to the homeowner.”

“What happens to these bags?”

“We remove them and put them in temporary storage for three years.”

Temporary storage turned out to mean, for instance, those fields in Tomioka where so many black bags sat.

“Then what?”

He smiled, laughed, shrugged.

But Mr. Kanari told me: “First we remove the soil, then put it in a bag, then it has to stay on the homeowner’s property until a formal decontamination begins.”

The “superior” explained: “Unlike the United States where there are rules, here we make up the rules.”*

I had Mr. Kanari test a potted houseplant: 0.14 micros; the construction boss’s boot, 0.11; a dirt berm behind the house, 0.33; a rain channel in the sloping concrete driveway, a surprisingly low 0.16; then the drainpipe: 0.49. That last reading was not so good. It worked out to 4.29 millis per year.

Pointing to the pipe, I asked him: “How can you decontaminate it?”

“Structurally speaking, unless you break it, it’s rather difficult. We must see what the property owner says.”

Here were two black bags side by side, at 0.35 and 0.38 micros; and there was the next door neighbor’s drainpipe at 0.17.

The two decontamination men agreed that radiation generally went about five centimeters into the ground.*

Across the highway lay a field of vegetables. I asked Mr. Kanari to read the crops for me, but he said: “The scintillation meter measures only the air, not the thing.” All the same, he did as I asked: 0.13 away from the dirt, 0.18 close to the dirt, where a napa cabbage was.

We drove to another place on a hill; it was called Ohisa. There were some heavy blackish-green tarps, and then a blue tarp “as an afterthought,” they said. There was a DO NOT ENTER sign. The air read 0.17 about 2 meters from the sign. Mr. Kanari entered the site and placed his meter almost on a bag, which read 0.19.

“What do you think of these readings?” I later asked Ed Lyman.

“Not very impressive. One to five times background. In my apartment” in Washington, D.C., “I register 0.2 microsieverts per hour.”—I did the math: 4.8 microsieverts a day, or 1.74 millis a year. My studio’s kitchen gave off just over a milli in the same period. How glad I was to live on the west coast!

Mr. Kanari was very reluctant to measure the forest, since the municipality’s only concern was to decontaminate where people actually lived, but I finally coaxed him into entering a snowy bamboo grove at the mountain’s edge behind the field of Chinese cabbage: 0.43 micros per hour, or nearly four times Mr. Kida’s stated goal of a single annual milli. Mr. Kida, of course, had said that 0.5 microsieverts per hour was acceptable, so he might have felt quite contented here. Maybe even Ed Lyman would have been at peace.

Once upon a time in Kyoto I used to sit in a temple garden called the Shoren-In, whose bamboo grove at the end of the winding path afforded a quiet view of a carp pond the rock border of which achieved asymmetrical grace. Camphor trees shaded my dreams at the Shoren-In, but what I most loved was the bamboo grove itself, whose jade towers decorated the sky. Now I remembered that place while Mr. Kanari stood beside me, holding his scintillation meter as we all listened to the sounds of those lovely bamboos, which resembled birdsongs or windy hollow gurglings, and I almost felt happy.

“How dangerous is it?” I asked the decontamination workers.

They replied that no one should stay here more than half a month.

“What should the authorities do about this?”

“Because it’s endless.” Mr. Kanari sadly smiled. “And this is not the place where people often go.”*

He was probably right, and anyhow I’m not the sort of cad who would want to spread harmful rumors. The silver lining in that radioactive cloud was that if everything continued perfectly from here on out, a mere two half-lives (60 years for cesium-137) would bring the levels below a milli. With respect to Japan, arithmetic had become one of my favorite distractions.