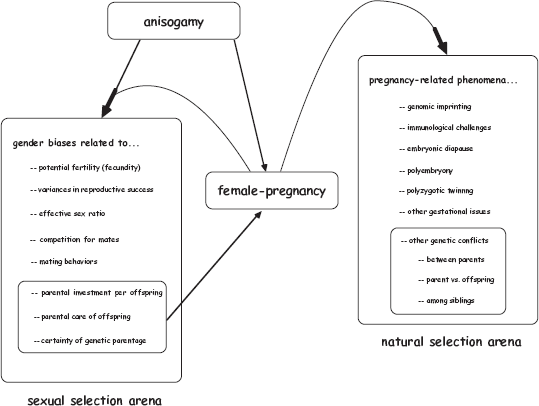

We learned in chapters 1 and 7 that anisogamy (the larger size and lower motility of female gametes) initiated an evolutionary cascade of gender biases with respect to potential fertilities, variances in reproductive success, intensities of mate competition, the nature and direction of sexual selection, the elaboration of secondary sexual traits, magnitudes of parental investment in progeny, proclivities for pregnancy and brooding, and assurances of biological parentage for particular offspring. We also learned that female pregnancy in viviparous taxa then often amplifies these sexual biases by further curbing female fecundity and making each female even more limiting as a reproductive resource. Female pregnancy then feeds back into the entire procreative processes by synergistically boosting the sexual biases underlying sexual selection and mating strategies. Female pregnancy also affects the way in which natural selection and kin selection jointly influence the evolutionary trajectories of phenomena such as genomic imprinting, immunological reactions, and genetic conflicts between parents, among siblings, and between offspring and parents (chapter 6). Figure 8.1 gives a diagrammatic overview of this complex nexus of evolutionary causation.

Having addressed many of the selective forces at work during mammalian (chapter 6) and piscine (chapter 7) pregnancies, we can now compare gestational phenomena across these and other brooding taxa from a broader evolutionary vantage point. This final chapter examines the impact of alternative gestational modes (such as male pregnancy/female pregnancy and internal/external brooding) on sexual selection and natural selection.

FIGURE 8.1 The central places of anisogamy and pregnancy in the broader evolutionary framework of sexual selection and natural selection related to embryonic gestation. Arrows show just some of many causal connections and feedback loops (see text).

As Bateman (1948) famously emphasized (chapter 7; see also Wade and Shuster 2010), a male can in principle increase his reproductive output dramatically by mating with several or many females, whereas a female normally stands to gain much less from taking multiple mates. Consequently, males in many outcrossing species (viviparous or otherwise) typically experience stronger intra- and intersexual selection than do females and thereby tend to evolve and display greater elaborations of secondary sexual traits.

Further support for Bateman’s insights into causal relationships among mate numbers, reproductive fitness, and sexual selection has come from appraisals of genetic mating systems in pipefishes and seahorses (Syngnathidae), which display the peculiar phenomenon of internal male pregnancy. As detailed in chapter 7, some pipefish species show sex-role reversal in the sense that Bateman gradients are steeper for females than for males, polyandry is common, sexual selection operates more intensely on females, and females tend to evolve secondary sexual characteristics. Additional contrasts of this sort are made possible by the many fish species in which bourgeois males tend embryos in nests. With respect to parental investment in offspring, such species in effect display external male pregnancy (chapter 7). Similarly, in a few invertebrate taxa, including Pycnogonida (sea spiders) and Belostomatidae (giant water bugs), males alone brood the young, in this case on their outer body surfaces (chapter 4). Such observations raise this question: How do alternative forms of pregnancy affect the evolution of mating behaviors by the parental sex that conducts the brooding (as well as by the opposite gender)?

As applied to viviparous and other species with extended parental care of progeny, Bateman’s (1948) reasoning implies that any member of the non-pregnant sex can normally enhance its reproductive output by mating with multiple partners, whereas much more problematic is the degree to which a member of the pregnant sex might profit from multiple mating. Thus, at issue in female-pregnant species is not why males routinely seek multiple mates, but how often and why females might also do so.

In theory, multiple mating by females might confer any of several fitness benefits on a polyandrous dam in female-pregnant taxa. Hypotheses to account for polyandry generally fall into two broad categories (table 8.1) depending on whether the purported benefits to a female are direct (material) or indirect (genetic). Examples of direct benefits include the receipt of courtship gifts, better access to male-held territories, a reduced risk of sexual harassment from males, and improved chances of finding a behaviorally compatible mate. Examples of indirect benefits to a polyandrous female include a better opportunity to receive “good” paternal genes for her offspring, higher genetic diversity within her brood, fertilization insurance against the possibility that some males are sterile, hereditary “bet hedging” in unpredictable environments, and/or several other potential bonuses that might elevate a polyandrous female’s fitness above the fecundity plateaus otherwise imposed by anisogamy and pregnancy. Yet another possibility is that polyandry is merely a correlated evolutionary response in females to positive selection for the same genes that underlie polygyny in conspecific males (Forstmeier et al. 2011).

For several reasons the topic of multiple mating by members of the pregnant sex has attracted scientific interest in recent years. First, viviparity is a high-investment tactic that seems likely to promote strong selective pressures on mating proclivities by adult brooders. Second, molecular markers have been deployed to illuminate the genetic mating systems of many viviparous and brooding species in nature (see the appendix). Third, these genetic parentage analyses are ideally suited for estimating successful mate numbers for pregnant individuals because each litter comes conveniently “prepackaged” with one of its parents. Thus, by comparing the genotype of each brooded offspring to that of its pregnant dam or sire, alleles contributed by that parent’s successful mate(s) usually become evident by subtraction. Finally, in theory different gestational modes should have major consequences for how sexual selection operates on brooder versus nonbrooder individuals.

TABLE 8.1 Fitness benefits often hypothesized to attend polyandrous matings

| Nature of the Fitness Benefit |

|

Representative Example or Review |

Direct material benefits |

|

Møller & Jennions 2001 |

courtship feeding (nutritional support) |

|

Gwynne 1984; Griffith et al. 2002 |

better territories (more resources) |

|

Andersson & Simmons 2006 |

reduced risk of sexual harassment |

|

Birkhead & Pizarri 2002; Lee & Hays 2004 |

more parental care |

|

Préault et al. 2005; Östlund & Ahnesjö 1998 |

better immediate mate compatibility |

|

Ryan & Altmann 2001 |

Indirect genetic benefits |

|

Jennions & Petrie 2000 |

fertilization insurance |

|

Baker 1955 |

better genes via gamete competition |

|

Parker 1990; Birkhead & Møller 1998 |

better genes via cryptic gamete choice |

|

Birkhead & Pizarri 2002 |

enhanced offspring viability |

|

Simmons 2005 |

progeny with more competitive gametes |

|

Curtsinger 1991; Keller & Reeve 1995 |

reduced risk of incompatible gametes |

|

Zeh & Zeh 1997; Tregenza & Wedell 2000 |

higher genetic diversity within a brood |

|

Yasui 1998; Stockley 2003 |

bet hedging in unpredictable settings |

|

Yasui 2001 |

acquisition of compatible genes for self or progeny |

|

Pryke et al. 2010 |

These hypotheses are not mutually exclusive and often overlap to varying degrees (Jones and Ratterman 2009; Uller and Olsson 2008; Jennions and Petrie 2000).

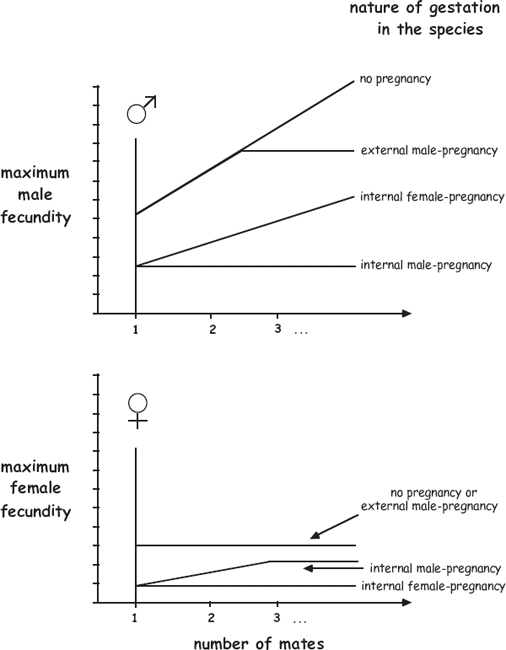

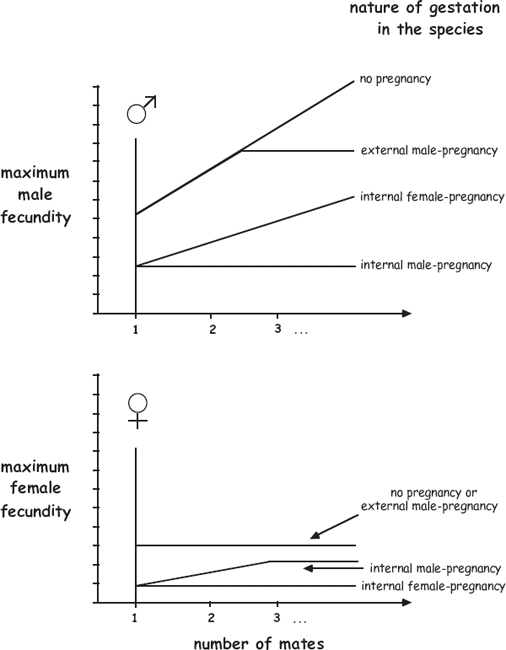

One such theoretical framework is encapsulated in figure 8.2, which shows how four alternative forms of embryonic development (no pregnancy, internal gestation by dams, and internal versus external gestation by sires) truncate individual fecundity in ways that should influence selective forces on the mating decisions by males and females. For species with female pregnancy (panel C in fig. 8.2), one effect of such fecundity truncation is to lower each dam’s fertility below the already low ceiling (compared to that for a male; see panel A) attributable to anisogamy alone. By contrast, for species with male pregnancy (panels B and D), a sire’s maximum fecundity falls dramatically below what it otherwise might be in the absence of the male pregnancy phenomenon (panel A). This fundamental asymmetry between the sexes in the fitness-cropping effects of internal gestation is presumably yet another reason that the phenomenon of internal male pregnancy rarely evolves. Nevertheless, brooding’s truncation of a male’s fecundity is probably much less severe in species with external male pregnancy (panel B) than it is in species with internal male pregnancy (panel D) due to the likelihood that more brood space for embryos is available within a fish’s nest than within a sire’s interior womb.

The theoretical expectations in figure 8.2 can also be summarized in another format: as hypothetical Bateman gradients in species with alternative modes of offspring care (fig. 8.3). For each line in these graphs, the left-hand intercept shows a monogamous adult’s maximum fecundity as dictated by brood space in various gestational modes, and each slope shows how a focal individual’s reproductive success potentially increases as the individual acquires more mates. Thus, a comparison of the topmost lines in the two graphs indicates that steeper Bateman gradients are expected for males than for females in many nonpregnant species, and the intercepts and slopes of the other lines predict how brood-space restrictions imposed by different forms of pregnancy lower the reproductive potentials of focal adults who are respectively monogamous or polygamous.

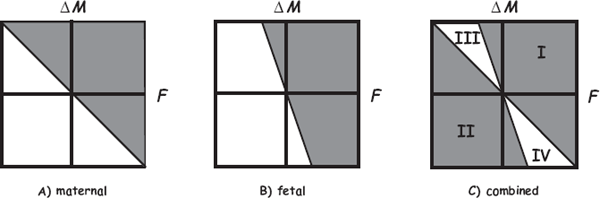

FIGURE 8.2 Expectations about maximum fecundity (the potential reproductive rate) of monogamous and polygamous males and females in four gestational modes displayed by various fish species (from Avise and Liu 2010). See the text for explanation.

With regard to pregnancy’s role in shaping mating behaviors, these models make several predictions: (a) members of the nonpregnant sex almost always experience strong selection for multiple mating because each such individual’s reproductive output otherwise is truncated by the finite brooding capacity of its one-and-only pregnant mate; (b) external brooders may experience stronger selection for multiple mating than do internal brooders because brood-space constraints in the former are less severe; and (c) given the fact (due to anisogamy) that gravid females in female-pregnant species can accept many more sperm cells than males in male-pregnant species can accept eggs, opportunities to acquire multiple mates may be greater for pregnant females than for pregnant males, all else being equal.

Another expectation with regard to multiple mating in pregnant and brooding species relates to possible correlations between clutch size and number of successful mates. There are at least three reasons to expect that individuals who gestate large broods might have higher incidences of polygamy (more mates and/or higher frequencies of multiple mating) than parents that host small broods. First, large broods should provide more “statistical room” (as well as more physical space) for multiple paternity or maternity, all else being equal. Second, many direct or indirect benefits that an incubating parent might gain from polygamous matings could be amplified by the additional full-sib cohorts that larger broods in principle might accommodate. Third, due to greater potential fitness, members of the nongestating sex should also have much greater incentives to mate preferentially with brooders that are more fecund (i.e., carry larger broods). For all of these reasons, it would not be too surprising if molecular-parentage analyses registered more full-sib cohorts per litter in large-clutch specimens and species than in their smaller-clutch counterparts.

The following sections describe how these expectations have recently been tested using comparative data on genetic parentage in numerous animal species with alternative modes of pregnancy or brooding.

FIGURE 8.3 Theoretical sexual-selection gradients for males (above) and females (below) in species with alternative modes of embryonic support (from Avise and Liu 2010). The females’ lower effective fecundities mostly reflect the effects of anisogamy. The “no pregnancy” lines in the two graphs reflect the standard situation, in which Bateman gradients are steeper for males than for females, whereas the intercepts and slopes of other lines in the graphs depart from these “no pregnancy” baselines due to limited brood space for embryos in various forms of pregnancy (see text and fig. 8.2). The initial positive slope of the Bateman gradient for females in species with internal male pregnancy further assumes (as is true in many syngnathid fishes) that a female can produce more eggs than a male can incubate.

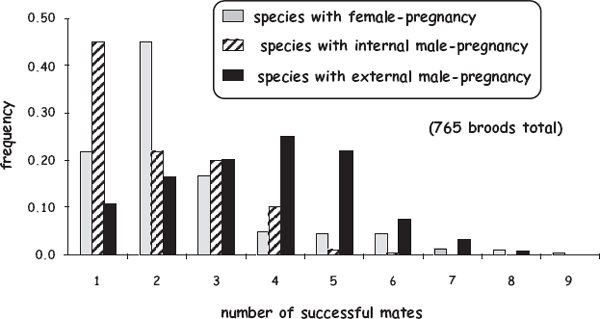

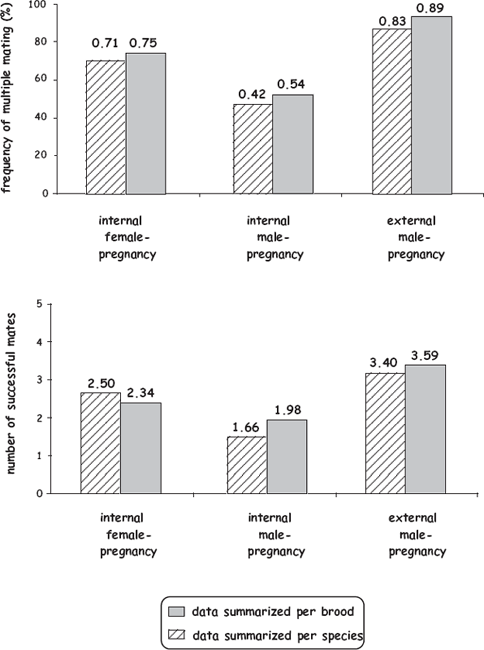

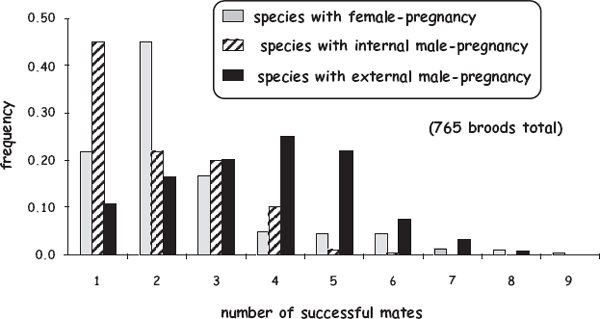

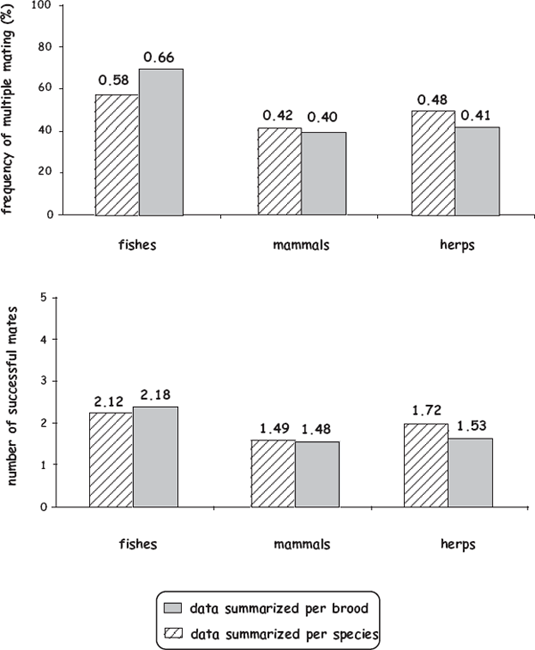

Empirical findings from extensive genetic-parentage analyses of piscine broods generally support many of the predictions listed earlier, albeit sometimes only weakly. In a survey of the scientific literature on genetic mating systems in fish species with female pregnancy, internal male pregnancy, or external male pregnancy (Avise and Liu 2010), successful polygamy by members of the brooding sex proved to be common (fig. 8.4), as more than 50% of all broods comprised two or more (and as many as nine) full-sib cohorts. This is perhaps unsurprising, given the many potential fitness payoffs of polygamous matings (especially to members of the nonpregnant sex). Furthermore, rates of multiple mating and mean mate counts were significantly higher in species with external pregnancy than they were for species with internal pregnancy, and they were also higher for dams in internal female-pregnant species than they were for sires in internal male-pregnant species (fig. 8.5). These empirical outcomes are all consistent with the notion that different gestational modes have rather predictable consequences for each parent’s effective fecundity and thereby for its exposure to selection for polygamy. On the other hand, all of these trends were statistically mild at best. Indeed, perhaps the more telling revelation of this empirical overview of piscine genetic mating systems was the surprisingly small mean number (typically only 1–4) of full-sib cohorts per brood across a wide diversity of fish species with very different pregnancy modes.

FIGURE 8.4 Genetically deduced numbers of successful mates that contributed to each of 765 broods of 29 pregnant fish species (after Avise and Liu 2010).

FIGURE 8.5 Genetically deduced frequencies of multiple mating (above) and mean numbers of successful mates per brood (below) for parents that were incubating a total of 765 broods in 29 fish species, representing three alternative types of pregnancy (after Avise and Liu 2010). Shown are mean values as calculated both on a per-species (regardless of brood number) and per-brood basis.

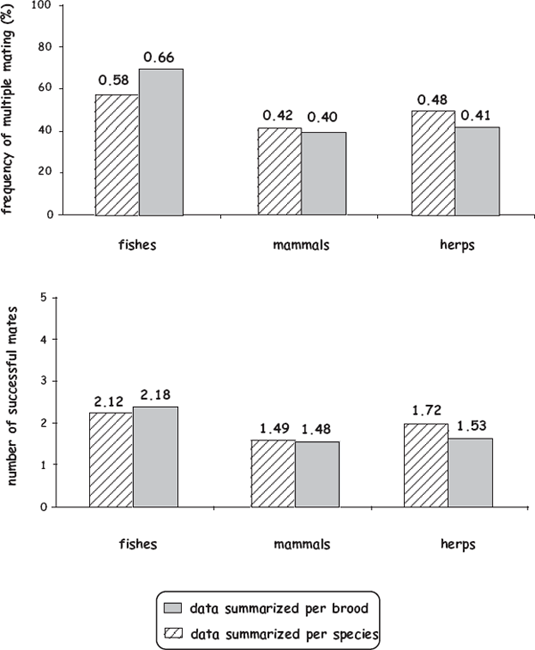

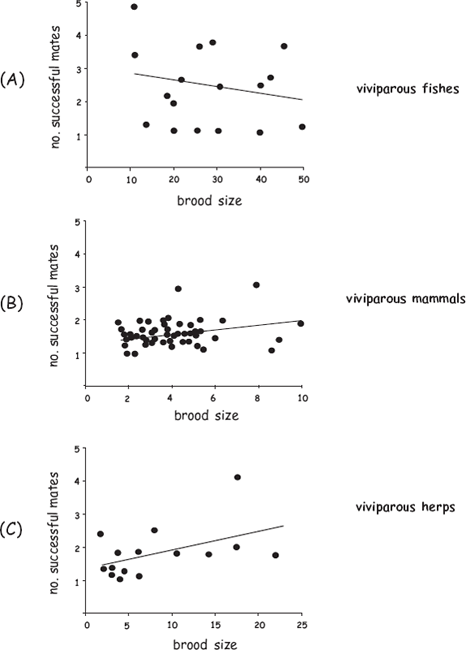

To further address the evolutionary ramifications of finite brood size and truncated fecundity for mating behaviors in the pregnant sex, Avise and Liu (2011) expanded this review of the genetic-parentage literature to include viviparous amniotes (mammals and reptiles) and live-bearing amphibians. As was also true for the pregnant fishes, multiple mating by the pregnant sex proved to be common in most other live-bearing vertebrates (fig. 8.6). Furthermore, as might have been predicted given their 10-fold smaller clutch sizes, these other vertebrate groups tended to show lower rates of multiple mating and averaged fewer mates per brood than did their pregnant piscine counterparts. However, these trends again were modest and gave little evidence that clutch size per se is a key selective factor underlying mating decisions by individuals of the pregnant sex. Instead, the deduced numbers of full-sib cohorts per brood typically evidenced only about 1–4 genetically successful mates per brood, regardless of brood size. Furthermore, only weak correlations were detected between brood size and mate numbers within (and among) these three vertebrate groups (fig. 8.7).

FIGURE 8.6 Genetically deduced frequencies of multiple mating (above) and mean numbers of mates per brood (below) for parents that were incubating a surveyed total of 533 broods of viviparous fishes; 1,930 mammal broods; and 362 broods of viviparous herps (after Avise and Liu 2011).

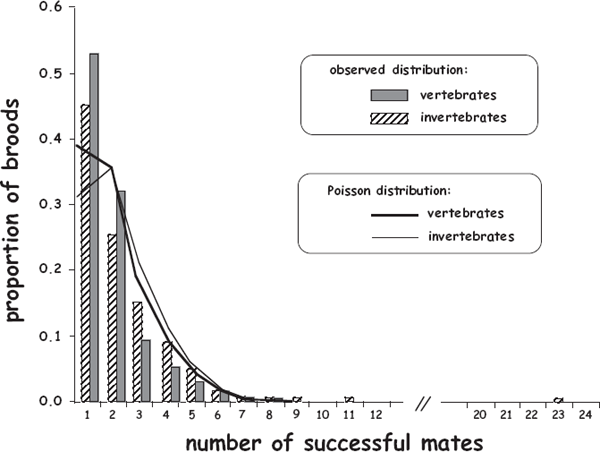

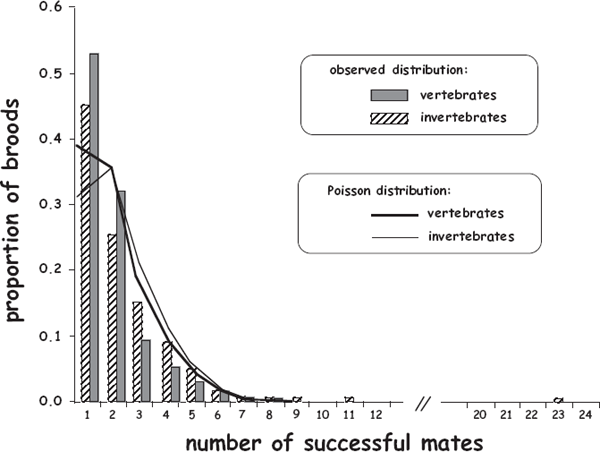

To extend such analyses further, Avise et al. (2011) then expanded their review of the genetic-parentage literature (see appendix) to include invertebrate animals that brood their young. As was also true for pregnant vertebrates, multiple mating proved to be common in the surveyed invertebrate brooders (fig. 8.8). Indeed, brooding invertebrates showed higher frequencies of polygamy and averaged more mates per brood than did their pregnant vertebrate counterparts, as might have been predicted given their much larger clutch sizes (often numbering in the hundreds to thousands of brooded embryos). Nevertheless, these tendencies again were modest and gave little evidence that clutch size per se has been a key selective factor governing mating decisions by members of the brooding sex. Instead, genetically documented numbers of mates per brood typically ranged upward to only about half a dozen individuals even in invertebrate taxa with extraordinarily large broods. This latter finding is intriguing because such huge broods could in principle house dozens or even hundreds of different full-sibships and also because molecular markers employed in the genetic surveys typically were polymorphic enough to have documented many more parents, had they in fact contributed to a given brood.

These findings from genetic-parentage analyses indicate that factors other than brood-space constraints must truncate multiple mating in nature far below levels that could otherwise be accommodated in most brooding invertebrates. Thus, these findings generally parallel the conclusions reached earlier for the pregnant vertebrates.

Overall, these comparative genetic appraisals of mating proclivities by individuals that become pregnant or otherwise brood their young have highlighted an interesting research irony. Whereas a stated goal in many theoretical and empirical studies of animal mating systems (see reviews in Arnqvist and Nilsson 2000; Simmons 2005) has been to understand why a gestating parent (typically the female) has so many mates and such a high proclivity for polygamy (see table 8.1), an oft-overlooked but equally compelling question is exactly the converse: Why do brooders and pregnant parents typically have so few successful mates?

FIGURE 8.7 Surprisingly weak correlations between clutch size and genetically deduced mean mate numbers per viviparous brood for: (A) 17 fish species (r = 0.31; P = 0.23); (B) 49 mammal species (r = 0.27; P = 0.05); and (C) 15 species of reptiles and amphibians (r = 0.52; P = 0.04) (after Avise and Liu 2011).

FIGURE 8.8 Genetically deduced frequencies of multiple mating (above) and mean numbers of successful mates per brood (below) for a total of 3,057 broods in 93 pregnant vertebrate species versus 583 broods representing 29 invertebrate species (after Avise et al. 2011).

Part of the answer probably has to do with costs to females of “too much” mating. For example, in their discussion of mating behaviors in promiscuous marine snails, Johannesson et al. (2010) noted that whereas “male fitness is expected to increase with repeated matings in an open-ended fashion, female fitness should level out at some optimal number of copulations.” However, apart from the diminishing returns and costs of multiple mating, much of the explanation for the observation that members of the pregnant sex generally have so few sexual partners probably has to do simply with the myriad logistical constraints on mating. In nearly every species, ecological and behavioral hindrances to successful mating abound (Hubbell and Johnson 1987; Gowaty and Hubbell 2009; Avise and Liu 2011). Depending on the population, restraints on mate acquisition might include any of numerous factors such as low population densities, short mating seasons, low mate-encounter rates, lengthy courtships, and perhaps even the postcopulatory phenomena of sperm competition and cryptic female choice (Jones and Ratterman 2009; Eberhard 2009; Birkhead 2010).

FIGURE 8.9 Empirical frequency distributions of broods in which the gestating invertebrate or vertebrate parent had various numbers of successful mates as deduced from genetic-parentage analyses. Also shown for comparison are the respective Poisson distributions of expected mate counts given the same mean numbers of mates as were documented genetically.

The net effect of such natural-history factors (mating costs and logistical constraints) is to circumscribe successful mate numbers dramatically, even in species with very large broods. Thus, before invoking a selective explanation of genetic polygamy in any focal species, an important question is whether the mean number of successful mates per brood statistically exceeds the rate of mate encounters given the particular biology and ecology of each species. This general kind of sentiment has been expressed previously. For example, after reviewing the literature on multiple paternity in reptiles, Uller and Olsson (2008, 2566) concluded that “The most parsimonious explanation for patterns of multiple paternity is that it represents the combined effect of mate-encounter frequency and conflict over mating rates between males and females driven by large male benefits and relatively small female costs, with only weak selection via indirect benefits.”

Thus, for nearly all pregnant and brooding animals (and indeed for essentially all sexual species), an unorthodox but potentially useful null model might envision successful mating opportunities as being in effect relatively “rare and random” events during an individual’s lifetime (Avise et al. 2011). Some support for this alternative null perspective on animal mating systems comes from a rather close agreement between empirical histograms of mate numbers per brood and theoretical histograms of mate numbers under statistical Poisson distributions with the same means (fig. 8.9).

Chapter 6 described several forms of natural selection that are motivated or amplified by the pregnancy phenomenon in mammals. Some of these expressions of natural selection are likely to be universal for viviparous and brooding species, whereas others may be much more restricted in their taxonomic distributions.

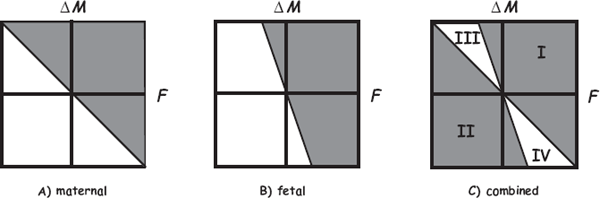

One suite of selective pressures that should apply to all taxa with extended parental care centers on the evolutionary emergence of parent-offspring conflict (Trivers 1974). Whenever a parent invests heavily in pre- or postpartum progeny, selective pressures on the protagonists’ genes inevitably swing into motion that in effect can pit parent against child (as well as parent against parent). Haig (2010b) presented a general graphical model (fig. 8.10) of how both conflict and cooperation might be expected between maternal and fetal genes in species with high parental investment (PI). Haig (2010b) followed Trivers (1974) in defining PI as any investment by the parent in an individual offspring that increases the offspring’s chances of surviving (and hence reproductive success) at the cost of the parent’s ability to invest in other offspring. Because PI provides a benefit (B) to the offspring at a cost (C) to the parent’s extended fitness, PI implies an evolutionary conflict or trade-off such that, from a parent’s perspective, additional PI is favored whenever B > C; whereas from a progeny’s perspective, further PI is favored whenever B > rC, where r is the probability that another of the parent’s children carries a copy of a randomly chosen gene in the focal offspring. Because r ≤ 0.5 in all cases, genes in a fetus are generally under selection to demand more PI than genes in the parent are selected to supply (Trivers 1974).

FIGURE 8.10 Haig’s (2010b) graphical model of cooperation and conflict between maternal and fetal genes affecting parental investment (PI). F is a fetus’s fitness, and ΔM is the change in a mother’s residual fitness (her expected number of progeny, not including the focal fetus) that might result from modifications in the expression of a gene underlying PI. Panel A, genes expressed in the mother; panel B, genes expressed in the fetus; panel C, a combination of panels A and B, showing expected zones of maternal-fetal cooperation (regions I and II) and conflict (regions III and IV). These graphs portray outcomes under the assumption that the two focal offspring (a current and a future fetus) are full-sibs (r = 0.5), but if r < 0.5 (as would be true under polyandry), the zones of potential maternal-fetal conflict would be even larger. See the text for further explanation.

In Haig’s model (fig. 8.10), the two axes represent changes that a new genetic variant confers on a focal fetus’s fitness (F) and on a dam’s residual fitness (M, her future reproduction), respectively. The zero point where the two axes cross represents the evolutionary status quo (i.e., before any new genetic variant arises). Maternal fitness is increased if F + ΔM > 0 (shaded area in panel A), whereas fetal inclusive fitness is increased if F + rΔM > 0 (shaded area in panel B). In panel C (which combines panels A and B), the shaded regions I and II are zones where a genetic change is favored and disfavored, respectively, regardless of whether it is expressed in the dam or the fetus. By contrast, the unshaded regions III and IV are zones of potential maternal-fetal conflict. In region III, a genetic change is favored if it is caused by a gene expressed in the mother but not by a gene expressed in the fetus (and vice versa for region IV). Overall, regions I and II in panel C thus represent expected zones of maternal-fetal amicability, whereas quadrants III and IV are zones of potential maternal-fetal antagonism.

Although Haig’s (2010a) model was offered in the context of imprinted genes and the “placental bed” in mammals (chapter 6), its predictions should apply to many other expressions of parent-offspring conflict (and cooperation) in any species with high parental-investment tactics such as pregnancy or brooding. Four broader sentiments that Haig (2010a) emphasizes are as follows: (1) the evolution of maternal-fetal relations is complex because a dam and her offspring share only some of their genes; (2) the selfish fitness interests of maternal and fetal genes overlap broadly but incompletely; (3) the evolution of any complex maternal-fetal interaction (such as at the placental boundary) is likely to be underlain by genetic changes with some combination of both cooperative and antagonistic etiologies; and (4) parent-offspring relations during and after a pregnancy provide a dynamic evolutionary arena for natural selection because ineluctable fitness trade-offs and compromises exist between the oft-competing genetic interests of the participants.

Although parent-offspring conflicts over finite parental resources are likely to be universal in pregnant and brooding species, exactly how these disputes mechanistically play out must depend in large part on the mode of gestation displayed by a given species or taxonomic group. In external brooders, for example, a parent and an embryo may have little or no direct physical contact, and this clearly limits opportunities for circulating hormones or other effector molecules to mediate metabolic disputes by the physiological or biochemical mechanisms that often characterize species with internal pregnancy (Crespi and Semeniuk 2004; Schrader and Travis 2008). Even among species that are strictly viviparous, the presence or absence of placenta-like structures and the magnitude of material interchange at the parental-fetal interface are likely to affect not only how intergenerational conflicts transpire during each pregnancy but also how they evolve in a given lineage (Reznick et al. 2002; O’Neill et al. 2007; Schrader and Travis 2009; Panhuis et al. 2011). More generally, exactly where a species falls along the matrotrophy-lecithotrophy continuum of parental care can make big differences for the operation of evolutionary forces associated with pregnancy.

Some of the other mechanistic operations that are likely to vary according to gestational mode include immunological interactions between parents and embryos and the syndrome of genetic imprinting for genes involved in fetal growth. Obviously, immunological issues during a pregnancy apply mostly to internal brooders with refined immune systems, whereas genomic imprinting could in principle find at least some form of expression in any species with pregnancy or brooding. Indeed, imprinted genes might be expected to exert their effects on parent-offspring interactions long after a pregnancy itself. For example, the evolution of lactation, age of weaning, and maternal-infant interactions in primates might in principle be influenced by imprinted genes in much the same way as are maternal-fetal interactions in utero. Indeed, from an analysis of human disorders related to imprinted genes, Haig (2010b, 1731) found evidence that “genes of paternal origin, expressed in infants, have been selected to favor more intense suckling than genes of maternal origin.”

On the other hand, imprinting effects on genes that influence embryonic growth are not to be expected in taxa such as broadcast spawners, which entirely lack postzygotic parental care. However, most organisms show at least some degree of postzygotic maternal investment in their offspring. Thus, one perplexing question currently demanding further research is why genomic imprinting seems to be confined mostly to mammals and plants. Is there something peculiar about the biology of these organisms that uniquely predisposes them to imprinting, or is genetic imprinting perhaps much more taxonomically widespread than has been adequately documented to date? Moreover, if imprinting does prove to be more taxonomically widespread, what types of genes are involved, and how do their mechanistic operations relate to alternative gestational modes?

Apart from the parent-offspring, parent-parent, and inter-offspring conflicts routinely promoted by pregnancy (chapters 6 and 7), other types of evolutionary disputes may become amplified in viviparous and brooding species. Consider, for example, the frequent opposition of natural selection and sexual selection. Many phenotypic traits associated with pregnancy register evolutionary compromises between these opposing selective forces. An obvious example involving swordtail fish was mentioned in chapter 7. Recall that pregnancy in these viviparous fishes makes females an especially valuable resource for which males actively compete for reproductive access. The choosy females prefer to mate with males possessing longer tails, which thus are promoted by epigamic sexual selection even while being opposed by natural selection because they make swimming more difficult. Fitness trade-offs from such contrarian selection between survival (natural selection) and mating success (sexual selection) must be both common and expressed at many phenotypic levels in species with pregnancy or brooding. Indeed, pregnancy is fundamentally an evolutionary compromise that promotes the survival of the current offspring at the cost of diminishing a parent’s future reproductive prospects.

Another evolutionary expectation is that the potential for pregnancy-related conflict should be modulated by the nature of both the mating system and the gestational system. For example, parent-offspring prenatal conflict is generally expected to be most intense in highly polygamous placental species because viviparity offers longer and more intimate contact between embryos and the pregnant parent and because polyandry (or polygyny in male-pregnant species) promotes genomic conflict due to reduced genetic relatedness among littermates. Thus, any conflict that may have originated early in an evolutionary transition from oviparity to viviparity can later become accentuated, especially in lineages that evolve polygamy and placentation.

In nearly all comparative research on pregnancy, it becomes necessary at some point to disentangle phenotypic outcomes due to natural selection from phylogenetic legacies that might be fitness neutral or perhaps even maladaptive for their current bearers. Researchers employ at least two general research approaches: (a) functional analyses of extant phenotypes; and (b) phylogenetic character mapping (PCM) to deduce the evolutionary histories of alternative phenotypes (chapter 1). Examples of the former approach are legion and include modern-day attempts to identify the genes, physiological mechanisms, and functional consequences of a wide variety of gestation-related phenomena such as genomic imprinting, placentation, maternal-fetal interactions, and indeed viviparity itself (e.g., Constancia et al. 2002; Haig 2008; Lynch et al. 2008). Examples of the PCM approach likewise are legion and have included attempts to trace the evolutionary histories of pregnancy-germane phenomena such as the degree of placental development in female-pregnant fishes (Reznick et al. 2002), mating systems and sexual selection in male-pregnant fishes (Wilson et al. 2003), and alternative modes of parental care in various taxa (Goodwin et al. 1998; Mank et al. 2005). In the final analysis, a deeper understanding of pregnancy-related selection will require a thorough integration of adaptive evolutionary reasoning in conjunction with both phylogenetic and ontogenetic dissections of particular phenotypes associated with the gestation of embryos.

1. Pregnancy in effect amplifies what anisogamy initiated by further truncating female fecundity in viviparous species and thereby making females an even more valuable or limiting reproductive resource for which males often compete intensely for sexual access. This sexual asymmetry has many consequences for mating decisions and sexual selection on males versus females, and in particular it raises the question of why females (in addition to males) sometimes seek multiple mates. In principle, females might receive either direct (material) or indirect (genetic) benefits from polyandrous matings. Depending on the species, direct benefits might include nuptial gifts, access to better territories, reduced sexual harassment, and more or better assistance in rearing offspring. Possible indirect benefits to female fitness include fertilization insurance, higher genetic diversity within each resulting brood as a bethedging tactic in variable environments, better paternal genes for progeny, or any of several other such bonuses from multiple mating.

2. Molecular markers and genetic parentage analyses are ideally suited for appraisals of mating behaviors by members of the pregnant sex. In recent years such analyses have unveiled successful mate numbers per brood in numerous vertebrate species that display internal female pregnancy, internal male pregnancy, or external male pregnancy. Empirical summaries of this literature reveal high incidences of successful polygamy in most pregnant species, but they also show that gender-specific restrictions on brood size imposed by these three alternative modes of pregnancy only weakly predict polygamy rates by individuals that brood the offspring.

3. For invertebrate animals that brood their young, a review of the genetic-parentage literature likewise reveals typically high incidences of multiple mating by the gestating parent. Again, however, the data provide little support for the hypothesis that clutch size per se has been a primary selective factor underlying the evolution of mating behaviors by the brooders. Instead, the most striking finding in the comparisons of invertebrates and vertebrates was the generally low (and similar) number of successful mates per brood almost irrespective of brood size. Thus, an alternative null perspective on animal mating systems might well emphasize polygamy’s many logistical constraints as a useful counterbalance to the field’s standard focus on possible fitness advantages from multiple mating.

4. Alternative pregnancy modes also affect the operation of natural selection. However, an overarching evolutionary theme is that all forms of gestation entail at least moderate parental investment (PI) in offspring. For any species with PI, conflict and cooperation between parents and their offspring are inevitable hallmarks of the procreative process. An extensive body of evolutionary theory and empirical evidence addresses the topics of antagonism, fitness trade-offs, and contrarian selection pressures on male and female parents and on both their current and future offspring. Such conflicts sometimes play out in unanticipated ways, as illustrated by the peculiar phenomena of genomic imprinting.

5. In nearly all discussions of gestation in a comparative context, it is important to disentangle the roles of selection and phylogenetic constraint (historical legacy) in generating present-day outcomes. Whereas many pregnancy-linked phenotypes have been shaped at least in part by natural and/or sexual selection, others are distributed across extant taxa in ways that also register phylogenetic legacies.