Stable Happiness Dies in Middle-Age

A Guide to Future Research

Ed Diener, University of Illinois, Champaign-Urbana, IL, USA, The Gallup Organization

The chapters of this volume show conclusively that adaptation is often only partial and that people can and do change in their levels of subjective well-being. Although the idea of a set point and homeostatic mechanisms to return a person to baseline have some validity, this book clearly indicates that baselines can and do change, and occasionally by a substantial amount. However, there are several key questions for future research. First, although several psychological processes are grouped together under the broad term adaptation, in fact we need to separately understand them—behavioral changes, inattentional blindness to long-term circumstances, emotional resilience, desensitization, and so forth. Sometimes adaptation is said to occur when, in fact, what has occurred is that the new circumstance changes in quality over time after an event. Second, we need more multimethod studies, for example, using experience-sampling and informant reports, to disentangle adaptation from changes in scale use. Third, we need process studies on various types of subjective well-being, such as the intensity versus duration of moods and emotions after events, as well as shifting aspiration levels that may influence life satisfaction. Fourth, we need to understand the psychological mechanisms that dampen affect and prevent it from remaining intense over time. Finally, we need more studies on how people can prolong responses to good events and foreshorten adaptation to bad events.

Keywords

adaptation; affect; homeostatic mechanism; set point; set point range; stable happiness; subjective well-being

This volume is a must-read for anyone involved in research on well-being. A stunning array of data is presented that demonstrates that subjective well-being can and does change. From nation changes over time to panel studies that follow individuals to experimental interventions, all the data converge on the fact that people are not locked to a concrete set point or baseline level. Furthermore, deviations from the set point need not be temporary, but can last for years or more. Even a set point range is thrown into question by the data presented in this volume. Although people inherit some propensity to certain moods and emotions, the range over which their subjective well-being can vary is quite large. Nonetheless, there are a set of processes that do tend to stabilize subjective well-being and reduce the likelihood that it will permanently take on an extremely positive or negative level.

In terms of data on change, Veenhoven (Chapter 9) shows that nations can change in average levels of well-being, and in the past decades, the majority of societies have been improving. Easterlin and Switek (Chapter 10) review evidence indicating that circumstances and public policies can influence average subjective well-being in societies. For example, they show that the safety net provided by active labor policies (e.g., job training programs) can increase citizens’ subjective well-being. Powdthavee and Stutzer (Chapter 11) review evidence showing that unemployment hurts subject well-being beyond the effects of lost income, in that it produces psychic costs due to insecurity. The fact that all these societal factors can move levels of subjective well-being indicates that there is not an absolute set point for subjective well-being. Hill, Mroczek, and Young (Chapter 12) show how affect can change across the adult life span. Ruini and Fava (Chapter 8) show that interventions can raise the subjective well-being from those suffering from low levels of it.

Frank Fujita and I (2005) showed that life satisfaction changed substantially for some individuals over a period of years. Importantly, even the average life satisfaction averaged over 5-year periods changed significantly for some respondents, suggesting that the instability was not simply due to event-related short-term spikes. For two 5-year periods separated by 7 years, life satisfaction correlated .51, indicating substantial instability. Headey, Muffels, and Wagner (Chapter 6) follow our lead in showing that people in the GSOEP can change in life satisfaction over the years. They then extend our work in pinpointing several of the factors that lead to change. Thus, multiple types of data all point to the fact that subjective well-being can change, and is not always firmly rooted at a homeostatic set point.

Armenta, Bao, Lyubomirsky, and Sheldon (Chapter 4) take the important next step of specifying several of the factors that can move people up or down in subjective well-being. Like Cummins, they specify a set point—not an absolute fixed point for each person but a range in which that person can take on various levels. For people to move upward within their set point range, Armenta et al.’s HAP (Happiness Adaptation Prevention) model points toward certain factors that help people resist adaptation to good events—surprise and variety, appreciation, and not allowing one’s aspirations to continually rise. They also make the important observation that we do not adapt to every circumstance; occasionally, we become more sensitized to them over time.

DeHaan and Ryan (Chapter 3) add an important new element to subjective well-being research, in suggesting that the fulfillment of psychological needs leads to positive feelings. Therefore, their theory suggests the kinds of events, leading to need fulfillment versus deprivation, that are mostly likely to alter people’s levels of subjective well-being. If people change significantly in fulfilling their universal psychological needs, their levels of subjective well-being should follow. Thus, DeHaan and Ryan offer a strong theory on what might produce long-term changes in subjective well-being.

Other valuable contributions to this volume are the chapters on methodology and statistics. Røysamb, Nes, and Vittersø (Chapter 2) thoroughly present what heritability and genetics have to do with happiness and dispel many of the misunderstandings that have arisen. Anyone who plans to discuss genetics in a paper on subjective well-being should read this chapter first. For one thing, the chapter explains why the genetic effects do not mean that subjective well-being is fixed. Eid and Kutscher (Chapter 13) explain the sophisticated statistics of analyzing change over time. Their thorough chapter will help readers decide among various analytic approaches to change data. Yap, Anusic, and Lucas (Chapter 7) describe the methodological and analytic issues in collecting and analyzing panel data. They also review the recent findings from longitudinal studies using sophisticated analytic techniques. In terms of analyses and methods, these chapters, which describe the most advanced approaches to assessing change, are a must-read for researchers. Nobody should do longitudinal studies in this field without reading these two chapters.

The book contains a number of approaches to what may cause change in long-term subjective well-being:

1. Armenta and colleagues’ (Chapter 4) description of factors such as novelty and surprise that influence adaptation.

2. Ruini and Fava’s (Chapter 8) intervention, which is based in part on cognitive approaches but also on Self-Determination Theory principles.

3. DeHaan and Ryan’s (Chapter 3) description of how self-determination explains happiness, and the psychological needs on which it is based. If fulfillment of basic psychological needs changes, then changes in levels of subjective well-being should follow.

4. Easterlin and Switek’s (Chapter 10) suggestion that public policies can influence citizens’ well-being, as well as the economic and noneconomic factors reviewed by Powdthavee and Stutzer (Chapter 11).

5. Headey and colleagues’ (Chapter 6) suggestion that life choices such as exercising and volunteering can increase subjective well-being. Importantly, Headey et al. review evidence that the values parents transmit to their children can influence the offsprings’ subjective well-being even in adulthood. Furthermore, the personality of one’s marital partner can raise or lower a person’s well-being over time.

What these approaches together reveal is that there are many and diverse factors that appear to change the levels of people’s subjective well-being. How these various factors relate to one another is a topic for future scholarship.

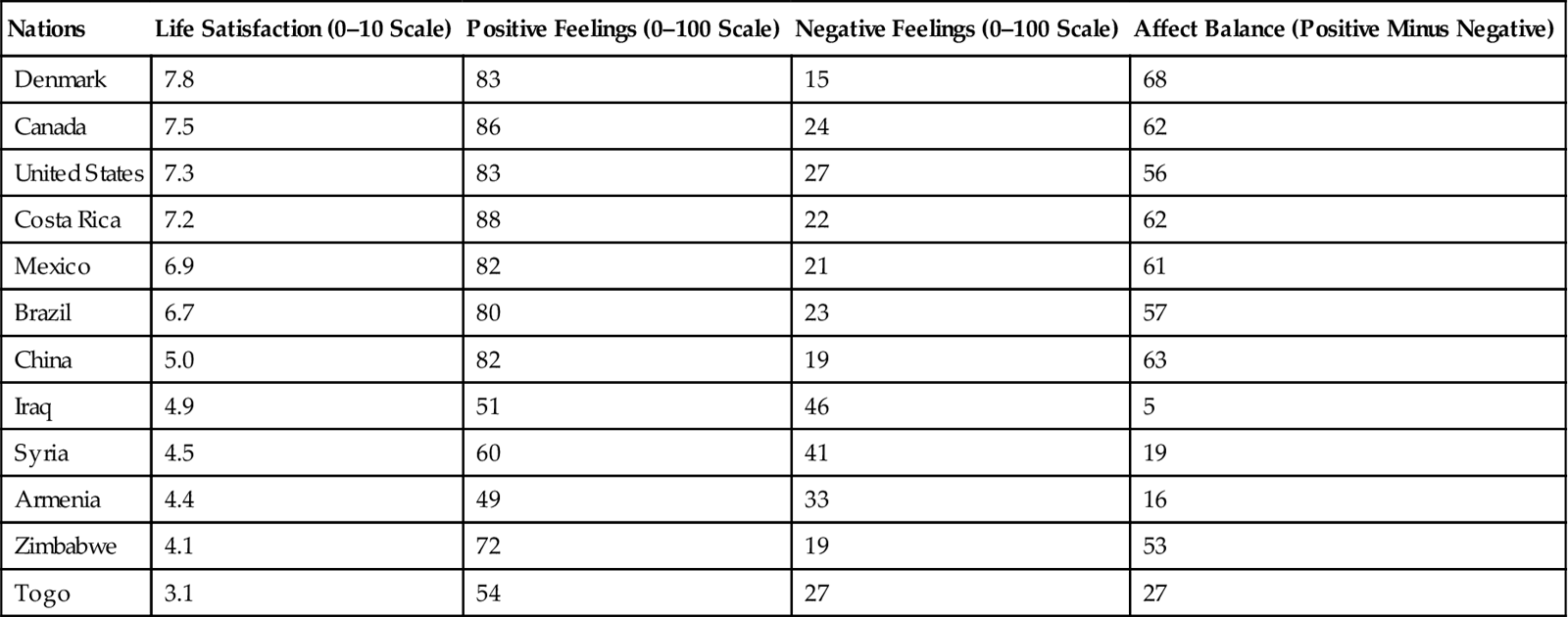

Another fact that stands out to me in suggesting that subjective well-being can be quite different depending on circumstances is the enormous differences in well-being between nations. Table 14.1 shows life satisfaction, positive affect, and negative affect levels for a number of nations. As can be seen, the differences are extremely large. Because of the very large numbers of respondents in the Gallup World Poll on which Table 14.1 is based, most of the country differences are statistically significant. But most surpass this statistical threshold and represent very large absolute differences in subjective well-being. Life satisfaction scores are based on Cantril’s self-anchoring ladder scale. Positive affect in the table is the percent in a nation who report two positive emotions: (a) enjoying most of yesterday and (b) smiling and laughing yesterday. Negative affect is the percent in the nation who report several negative emotions: anger, fear, depression, and sadness. The percentages are the number of people on average who reported each of the emotions in that category.

Table 14.1

Subjective Well-Being in Nations

| Nations | Life Satisfaction (0–10 Scale) | Positive Feelings (0–100 Scale) | Negative Feelings (0–100 Scale) | Affect Balance (Positive Minus Negative) |

| Denmark | 7.8 | 83 | 15 | 68 |

| Canada | 7.5 | 86 | 24 | 62 |

| United States | 7.3 | 83 | 27 | 56 |

| Costa Rica | 7.2 | 88 | 22 | 62 |

| Mexico | 6.9 | 82 | 21 | 61 |

| Brazil | 6.7 | 80 | 23 | 57 |

| China | 5.0 | 82 | 19 | 63 |

| Iraq | 4.9 | 51 | 46 | 5 |

| Syria | 4.5 | 60 | 41 | 19 |

| Armenia | 4.4 | 49 | 33 | 16 |

| Zimbabwe | 4.1 | 72 | 19 | 53 |

| Togo | 3.1 | 54 | 27 | 27 |

The differences we see in Table 14.1 map onto what we know about circumstances in these nations. Toward the top are economically prosperous nations that are high in social capital, have a respect for human rights, and are not mired in conflict. Toward the bottom are poor nations with tumultuous politics, where day-to-day life is insecure. In some nations, almost as many people feel negative emotions as frequently as the number who experience positive emotions, with conflict being a prime suspect of producing the low scores. The distribution of life satisfaction scores for Togo and Denmark overlap almost not at all, indicating that extreme conditions can make most everyone in a society satisfied or dissatisfied. If people were returning to a set point, the societal differences should not be so large. If there is a set point range, it too must be large.

One might argue that the national differences do not contradict set points. However, because the conditions in many of these nations have persisted over decades or more, there has been time for adaptation to baseline, if it were to occur. The other alternative explanation of the huge differences among nations in subjective well-being is in terms of heredity and genetics. This seems implausible for several reasons. First, the differences are sometimes very large, and it seems unlikely that two groups of humans could differ genetically that much. Furthermore, migration patterns suggest that the changes are largely due to differences in the circumstances in nations, not differences in genes. The ancestors of African Americans came largely from West Africa, where the slave trade was intense. Yet African Americans show much higher levels of life satisfaction than do people in nations of West Africa such as Togo. Furthermore, it is unlikely that happier people were those taken as slaves to the new world. Thus, neither genetics nor selective immigration seems able to explain the differences among nations in subjective well-being. One last piece of evidence supporting the explanation that the differences are due to long-term differences in circumstances is that the variations are predictable from measures of circumstances, such as income, longevity, lack of corruption, and level of strife. It seems almost a certainty that the differences are due to the felicitous versus unfortunate circumstances existing in different societies.

One chapter stands out in contrast to the rest. Robert Cummins (Chapter 5) argues for a set point, or at least set point range, for positive affect. Armenta et al. (Chapter 4) propose a related idea—a set point range, but with fairly stable values often occurring over time within that range. I would like to note several things in defense of Cummins. First, most of the chapters in this volume examine life satisfaction, whereas Cummins is focused on a set point for positive affect. Life satisfaction might be more subject to changeable aspiration levels, whereas affect might be more subject to homeostatic forces because people’s nervous systems have control mechanisms for the intensity of emotions and moods. The distinction that Kahneman, Krueger, Schkade, Schwarz, and Stone (2004) draw between experienced and judged well-being is important here.

Another fact to be noted in support of Cummins is that there certainly must be some homeostatic mechanisms in the affect system. People rarely stay elated for long after some wonderful event, and in fact, they usually do not stay permanently depressed after some bad event. People’s emotions do drop quickly in intensity after the initial response to the event. Furthermore, even in terms of life satisfaction people’s aspirations sometimes rise so that new and better circumstances do not lead to a permanent increase in subjective well-being. Thus, Cummins must be correct in pointing to some adaptation and homeostatic processes that influence subjective well-being. What the other chapters show is that these mechanisms are not absolute, and a new average baseline can sometimes be achieved. The data I present in Table 14.1 suggest that homeostasis does not completely bring emotions or life satisfaction back to some predetermined set point. Nonetheless, we need an integrated model that explains when levels of subjective well-being will move to a new level and what the limits to this are due to homeostatic forces.

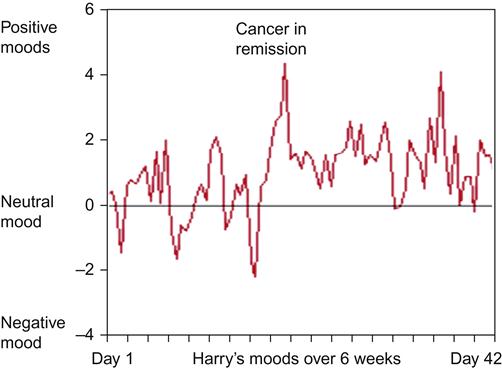

Figure 14.1 shows the moods of one of our research participants, “Harry,” who was undergoing chemotherapy for cancer. Harry completed two moods forms at random times each day for 6 weeks. As can be seen, when his physician told Harry that his cancer was in remission and effectively cured, his positive mood spiked. However, adaptation occurred and his moods returned toward their former level. Nevertheless, it can be seen that his moods returned to a somewhat higher average level than before learning of remission (a statistically significant increase). We cannot be certain that this higher average mood will persist, but it seems plausible that the cancer and the required treatments for it had lowered his average moods prior to learning of remission. Thus, this graph nicely summarizes that adaptation does occur, and people do not for long stay in an elated state even when wonderful positive news occurs. Nonetheless, average moods can rise or fall to some degree. Theories of subjective well-being need to recognize both that adaptation occurs and that it is not necessarily complete for all circumstances.

Harry’s moods and our other data suggest that happiness can change dramatically from moment to moment, situation to situation, and day to day. For example, we find that there are substantial mean differences in people’s moods between social versus alone situations (Diener, Larsen, & Emmons, 1984). When people recreate with others, their affect balance is several times higher than when they are working. Kahneman, Krueger, Schkade, Schwarz, and Stone (2004) found that when people are commuting to work they are much less happy than when they are socializing with friends. If people show such dramatic differences in short periods of time, then why would they not also experience long-term mean-level differences in subjective well-being, depending on differing frequencies of enjoyable versus unpleasant circumstances? The idea of adaptation seems to not fully explain this because people have experienced the situations over many years—for example, commuting or recreating with friends—and yet they are not fully adapted to it. Again, these situational differences suggest that adaptation does not eliminate differences and changes in subjective well-being.

Future Directions

The advances in scientific understanding are made very clear in the excellent chapters of this volume. We now know much more than we did at the time of the famous Brickman, Coates, and Janoff-Bulman (1978) paper. However, there are many important issues yet to resolve, and they provide exciting opportunities for investigators. Luhmann, Hofman, Eid, and Lucas (2012) examined a number of aspects of adaptation in a meta-analysis of the literature. Luhmann and her colleagues analyzed types of subjective well-being and found that often life satisfaction, which she labeled cognitive well-being, was more reactive to life events than was affective well-being (moods and emotions). Luhmann also found that personality moderated reactions to events; for example, neurotics responded more negatively to bad events. However, personality did not seem to influence the rate of adaptation. Finally, Luhmann studied sensitization and found that repeated exposure to unemployment causes increasingly lower life satisfaction, whereas repeated exposure to divorce seems to cause desensitization to the event. The topic of sensitization versus desensitization deserves much more research. Thus, Luhmann’s study is a model of examining adaptation in finer detail in order to understand the component processes involved. In the following, I outline several of the important questions that scientists in this area need to examine:

1. One issue we need to address more systematically is how people adapt in terms of life satisfaction versus positive and negative affect. Luhmann et al. (2012) made a start at examining this issue, but much more is needed. We need to know when and why adaptation for each type of subjective well-being occurs. Subjective well-being is not a unitary phenomenon, and our research must recognize that. In addition to studying experienced versus judged happiness, we can also examine adaptation in regard to the duration versus intensity of moods. It might be, for example, that people show a lot of stability over time in the intensity of their moods, with strong homeostatic forces quickly dampening intense moods, but experience less stability in changing circumstances in how often they feel certain emotions.

2. Another interesting issue that is not addressed in this book is the cross-situational consistency of subjective well-being; in this volume we cover primarily temporal stability. However, if one examines the issues, there is much overlap for consistency and stability. For one thing, both involve the person responding to differing circumstances. In an early study, Randy Larsen and I (1984) examined the consistency of moods, and found that although it was substantial, it was far from 1.0. Since that time there has been comparison of people’s moods at work versus home, in terms of a discussion spillover versus compensation, and so forth. Nonetheless, much more research is needed. Are people happier in the situations that match their personality? Do people make comparisons of situations in their lives to one another?

3. One important methodological advance we need is to use more methods to assess subjective well-being. Although self-reports of well-being might be the best single measure, other types of measures such as reports by informants, biological measures, and experience-sampling measures can be used to complement scores from the self-report surveys. Experience sampling in particular is a method that might be used more frequently in adaptation research, as it is less likely to be affected by memory biases than are global measures, and the method could potentially shed light on the details of how adaptation occurs. To the extent that the different methods yield the same adaptation curves, we gain confidence in our conclusions. To the extent that the methods yield different conclusions about adaptation, an opportunity arises for deeper understanding of the underlying psychological processes.

4. Adaptation is a generic name that points to a variety of different stabilizing processes that are quite distinct from each other. An important development in research on adaptation and change will be to measure the processes over time. One factor that can lead to adaptation is new behaviors. For example, one might adapt to the loss of a spouse by going out with friends more or visiting family more. One might adapt to a spinal cord injury by learning how to operate an electric wheelchair and other behaviors that make life easier. The person is not necessarily habituating to the new circumstances but is changing the quality of those circumstances. Another factor that leads to adaptation is attention, or lack of attention in this case. As pointed out in this volume, novelty draws attention, but over time novelty decreases and so new circumstances become commonplace and are noticed less. A third factor that might lead to adaptation is that one comes to develop a reasonable understanding or explanation of an event or new circumstance (Wilson & Gilbert, 2008), and it thereafter comes to evoke less of an emotional response. Finally, adaptation may come about because one develops a new set of goals and comparison standards. The paraplegic may change goals from becoming a fast runner to becoming a wheelchair athlete. A person who cannot walk might develop the goal of being adept at manipulating her or his wheelchair. These and other explanations have been discussed in the literature, but we need more measures over time of them, and in finer temporal detail. Each explanation might be most relevant to adaptation to circumstances with specific types of characteristics.

5. We need much more research on intervention studies designed at reducing the long-term impact of negative events and increasing the long-term response to positive events. Certainly, these questions have been addressed in past research, but we need studies of more types of interventions, increasingly long timespans covered, and increasingly stronger methodologies. For instance, multimethod measurement of well-being will help eliminate the possibility of response biases in the measures after the interventions, and more control groups with alternate treatments will help better eliminate potential explanations in terms of placebo effects. The chapters in this book focus on the influence on subjective well-being of changes of external events and circumstances. However, we need more intensive studies of a variety of interventions designed to change cognitive factors that could influence well-being, such as presented in Chapter 8 by Ruini and Fava. Meditation, mindfulness, positive thinking, exercise, and other interventions have received some scientific attention, but more and better studies are needed. Just because happiness can change, often in response to lifelong choices people make or to substantial alterations in their circumstances, does not mean that it is easy to purposefully change levels of subjective well-being with interventions. Changing it is challenging.

Conclusions

The field has come a long way since Brickman et al. (1978) claimed that we are on a hedonic treadmill and adapt to all circumstances. We now know that we do adapt to some circumstances, not to others, and partially adapt to yet others. We know that affective and cognitive measures of well-being may show different patterns of adaptation, and we have clues about what causes adaptation. We know that adaptation is an umbrella name that covers a whole set of somewhat independent psychological processes. The next wave of research will be to use strong methodologies to study how and why people do or do not adapt to events, in which researchers separately track different types of adaptations.

The homeostatic processes that prevent intense emotions from being long term must be identified and tracked. However, what we see as a stable set point might often be due to the fact that many circumstances in people’s lives remain fairly stable, as do their relationships and personality, even after some significant event that alters their lives in certain ways. Furthermore, the habitual cognitive habits people have developed over many years of appraising life and situations are ingrained and likely to remain relatively stable. Thus, resistance to changes in subjective well-being must be analyzed in terms of specific factors that inhibit change rather than attributing them to an unseen “set point.” By examining stabilizing variables, researchers will be more likely to determine the factors that promote as well as interfere with change. We must parse “adaptation” into the factors influencing subjective well-being that, in fact, remain stable over time and therefore create what appears to be a set point from the psychological processes that tend to bring people back to an original state after a true change occurs. We have come a long way, but there is exciting territory yet to explore.